Abstract

Spodoptera frugiperda SF9 cells infected with mutants of the Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) which lack a functional p35 gene undergo apoptosis, aborting the viral infection. The Spodoptera littoralis nucleopolyhedrovirus (SlNPV) was able to suppress apoptosis triggered by vΔP35K/pol+, an AcMNPV p35 null mutant. To identify the putative apoptotic suppressor gene of SlNPV, overlapping cosmid clones representing the entire SlNPV genome were individually cotransfected along with genomic DNA of vΔP35K/pol+. Using this complementation assay, we isolated a SlNPV DNA fragment that was able to rescue the vΔP35K/pol+ infection in SF9 cells. By further subcloning and rescue, we identified a novel SlNPV gene, Slp49. The Slp49 sequence predicted a 49-kDa polypeptide with about 48.8% identity to the AcMNPV apoptotic suppressor P35. SLP49 displays a potential recognition site, TVTDG, for cleavage by death caspases. Recombinant AcMNPVs deficient in p35 bearing the Slp49 gene did not induce apoptosis and showed successful productive infections in SF9 cells, indicating that Slp49 is a functional homologue of p35. A 1.5-kbp Slp49-specific transcript was identified in SF9 cells infected with SlNPV or with vAc496, a vΔP35K/pol+-recombinant bearing Slp49. The discovery of Slp49 contributes to the identification of important functional motifs conserved in p35-like apoptotic suppressors and to the future isolation of p35-like genes from other baculoviruses.

Apoptosis is a normal physiological cell suicide program that is highly conserved among vertebrates and invertebrates (19, 30, 38). This cell death program plays a critical role during normal development and tissue homeostasis, eliminating unwanted cells, including damaged and virus-infected cells, from the organism. Thus, animal viruses have evolved ways to evade, delay, or suppress this important cell defense strategy (reviewed in reference 32).

Baculoviruses possess two type of genes with antiapoptotic activity, iap and p35, which can suppress apoptosis induced by virus infection or by diverse stimuli in vertebrates or invertebrates (reviewed in reference 25). The iap genes from the baculoviruses Cydia pomonella granulovirus and Orgia pseudotsugata nucleopolyhedrovirus, were isolated by their ability to block apoptosis of Spodoptera frugiperda SF21 cells induced by a p35 mutant of the Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) (4, 10). Cellular homologues of iap genes were identified in the genomes of insects and vertebrates (12, 15, 23, 37).

The product of the p35 gene of AcMNPV inhibits a broad range of death proteases (caspases) (1, 3, 5, 39) activated during programmed cell death (reviewed in reference 35). p35 is unique in gene databases (25), and the only homologue reported so far is p35 of Bombyx mori NPV (BmNPV), a virus that has over 90% nucleotide sequence identity with AcMNPV (20).

We have previously observed that AcMNPV induces apoptosis in Spodoptera littoralis SL2 cells, in contrast to S. littoralis NPV (SlNPV) (7), suggesting that the latter virus may contain an antiapoptotic gene. To test this hypothesis, we first confirmed that SlNPV was able to block apoptosis of S. frugiperda SF9 cells induced by either an AcMNPV p35 null mutant (16) or actinomycin D. This result provided the basis to search for the presence of an apoptotic suppressor gene in the SlNPV genome. We report here the identification of Slp49, a functional antiapoptotic gene of SlNPV, isolated from an SlNPV cosmid library by complementing the replication of an AcMNPV p35 null mutant in SF9 cells. The predicted amino acid sequence of SLP49 showed 48.8% identity to AcMNPV p35 and is the first gene isolated from a baculovirus distant from AcMNPV reported to be homologous to the p35 gene. Recombinant AcMNPVs defective in p35, bearing and expressing Slp49, did not induce apoptosis in SF9, in contrast to their p35-deficient ancestor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and viruses.

S. frugiperda SF9 and Trichoplusia ni TN368 (18) cells were maintained and propagated in TNM-FH medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (31). Wild-type AcMNPV E-2 strain, SlNPV E-15 strain, and vΔ35K/LacZ were described previously (17, 29, 32) vΔP35K/pol+ was constructed by transfection of TN368 cells with vΔ35K/LacZ and pI1 (8) DNAs by using Lipofectin (GIBCO-BRL). The polyhedron-positive recombinant virus was isolated and purified by a standard plaque assay (31).

Construction of a cosmid library of SlNPV, DNA cloning, and sequencing.

SlNPV DNA was partially digested with Sau3AI and ligated into the vector Supercos 1 (Stratagene). Cosmid packaging and bacterial transformation were performed as specified by the manufacturer instructions. Cosmids, which encompassed the entire genome of SlNPV, were selected from the library of clones after their analysis by digestion with restriction endonucleases and Southern blot hybridization to SlNPV DNA. The cosmid DNA was purified on Qiagen columns. Cosmid NotI-C was constructed by cloning the 30-kbp NotI fragment included in cosmid C50 into Supercos.

Subclones of cosmid NotI-C were constructed in pBluescript SK-(Stratagene) by standard methods (24). pES2term was generated by NdeI digestion of pES2 (bearing the EcoRI-SalI fragment of SlNPV; map units 37.2 and 38.7, respectively) followed by end repair with Klenow polymerase and blunt-end ligation. This generated a frameshift of the Slp49 open reading frame (ORF) at nucleotide 1157, leading to premature termination at nucleotide 1196; this was confirmed by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing (27).

Plasmid clones were sequenced with specific synthetic primers. Sequence data were compiled and analyzed with Genetics Computer Group sequence analysis programs (11).

Marker rescue assay and isolation of recombinant viruses.

Marker rescue assays were performed as described previously (4, 10, 33). Routinely, 1 μg of vΔP35K/pol+ DNA and 1 μg of test DNA (cosmid or plasmid DNA) were cotransfected into 4 × 105 SF9 cells by lipofection. At 3 to 4 days after transfection, the cells were examined by light microscopy for the presence of polyhedra. Polyhedron-positive recombinant viruses were selected from independent cotransfections and subjected to three rounds of plaque purification in SF9 cells.

Extraction of fragmented DNA.

DNA oligonucleosomes were extracted for 2 h at 37°C from virus-infected SF9 cells with a 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer containing 70 μg of proteinase K per ml, and NaCl (final concentration, 1 M) was added. The extracts were treated with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended DNA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis as described previously (7).

Southern blot analysis.

Viral DNA was digested with various restriction endonucleases as specified by the manufacturer and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8% agarose) for 16 h at 30 V. After photography, the gel was quick-blotted to a nitrocellulose membrane. Hybridization was performed as described previously (24), with the 32P-labeled EcoRI-SalI fragment from pES2 bearing most of the Slp49 coding sequence.

Western blot analysis.

Wild-type AcMNPV-, vΔP35K/pol+-, or vAc496-infected cells were harvested and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis with either anti-P35 or anti-polyhedrin antiserum (7, 16).

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from virus-infected SF9 cells at various times after infection by using TRI-reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc.) as specified by the manufacturer. RNA (20 μg) was loaded onto a 1% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Hybridization was performed in a 50% formamide solution at 42°C with the same probe that was used for Southern blot analysis.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence presented in this report has been submitted to the EMBL Nucleotide Database and was assigned accession no. AJ006751.

RESULTS

SlNPV infection inhibits apoptosis of SF9 cells.

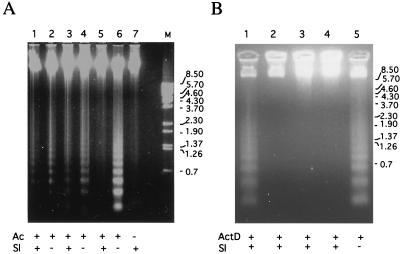

To search for potential SlNPV antiapoptotic genes, we first examined the ability of the virus to suppress apoptosis of SF9 cells. Apoptosis was induced by infection of the cells with vΔP35K/pol+, an AcMNPV mutant lacking a functional p35 gene (16). At 24 h, almost all the infected cells showed blebbing characteristic of apoptosis (data not shown) and DNA-fragmented oligonucleosome ladders were observed upon electrophoresis of extracted DNA (Fig. 1A, lanes 2, 4, and 6). Infection of the cells with SlNPV at 24 h prior to the addition of vΔP35K/pol+ inhibited apoptosis (lane 5). However, this result could be interpreted as interference of SlNPV with vΔP35K/pol+ infection, since addition of SlNPV to the cells 1 and 12 h prior to vΔP35K/pol+ infection did not block apoptosis completely (lanes 1 and 3, respectively). To confirm the ability of SlNPV infection to block apoptosis, we induced apoptosis of SF9 cells by adding actinomycin D (9). Oligonucleosomes were detected in DNA extracted from the cells at 24 h after incubation with 250 ng of actinomycin D per ml (Fig. 1B, lane 5). SlNPV infection at 5, 24, and 48 h, prior to actinomycin D addition, blocked blebbing (data not shown) and oligonucleosome formation (lanes 2, 3, and 4, respectively). These results suggested that the SlNPV genome contained an antiapoptotic gene.

FIG. 1.

SlNPV infection of SF9 cells prevents induction of apoptosis by an AcMNPV p35 null mutant or by actinomycin D. DNA was extracted from 3 × 105 SF9 cells infected with SlNPV at a multiplicity of infection of 5 (Sl + lanes indicated at the bottom of the figure). (A) vΔ35K/pol+ at a multiplicity of infection of 5 was added to the cells (Ac + lanes indicated at the bottom of the figure) at 0, 12, and 24 h after SlNPV infection (lanes 1 and 2, 3 and 4, and 5 and 6, respectively). At 24 h later, a sample for each pair of time points was extracted and analyzed by agarose electrophoresis. (B) Actinomycin D (250 ng/ml) was added at 1, 5, 24, and 48 h after SlNPV infection (lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively) or at 48 h for mock-infected cells (lane 5). The cells were harvested at 24 h after actinomycin D addition. Size markers in kilobase pairs are indicated on the right.

SlNPV contains an antiapoptotic gene.

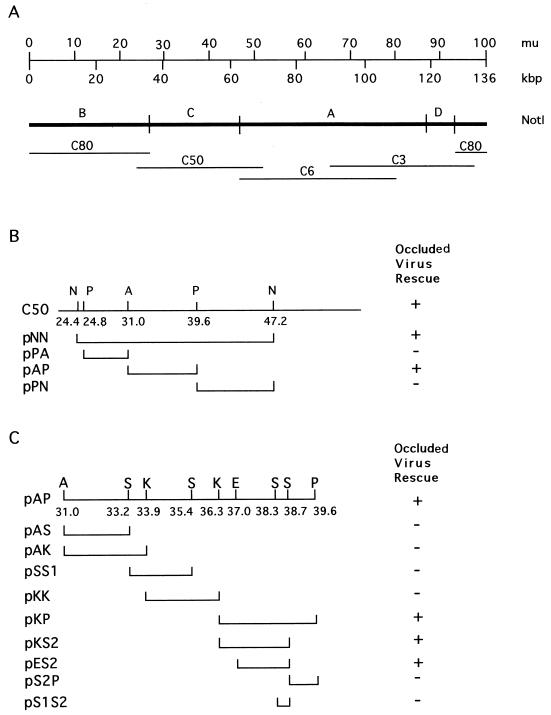

To identify the putative SlNPV antiapoptotic gene, we constructed a library of overlapping cosmid clones representing the entire SlNPV genome and assayed them for their ability to complement the replication of vΔP35K/pol+. Cotransfection of the whole library and vΔP35K/pol+ DNA allowed replication of vΔP35K/pol+, resulting in formation of viral occluded bodies (polyhedra), detected by direct microscopic observation of the nuclei of the cells. vΔP35K/pol+ DNA transfected alone did not form polyhedra (data not shown). When the cosmids were individually cotransfected along with genomic DNA of vΔP35K/pol+, only one of them, C50, which corresponded to SlNPV map units 25 to 54 (Fig. 2A), was positive. The fact that cosmids C80 and C6 (adjacent to C50) were negative for occluded virus rescue suggested that the complementing activity was present in the NotI-C fragment of SlNPV (Fig. 2A). Further subcloning of smaller DNA fragments of C50 in Bluescript and their assay in cotransfections as described above (Fig. 2B and C), allowed us to assign the complementing activity to a 2.4-kbp fragment, which corresponded to SlNPV map units 37.2 to 38.7 (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Rescue of occluded AcMNPV by cosmids and plasmids bearing SlNPV DNA fragments. (A) NotI linear restriction map of SlNPV. The scales above indicate SlNPV map units (mu) and kilobase pairs. The bars below (C80, C50, C3, and C50) represent the various overlapping cosmids of the genomic SlNPV cosmid library. (B) Restriction map of the cosmid C50 and individual plasmid subclones indicating their ability to rescue or not (+ and −, respectively) the replication of vΔ35K/pol+, as detected by the presence of polyhedra in the nuclei of SF9 cells cotransfected with vΔ35K/pol+ and plasmid DNA. N, NotI; P, PstI; A, ApaI. (C) Restriction map of the ApaI-PstI region corresponding to SlNPV 31.0 to 39.6 map units. S, SalI; K, KpnI; E, EcoRI. Also, subclones able to rescue vΔ35K/pol+ polyhedron formation, as in panel B, are indicated.

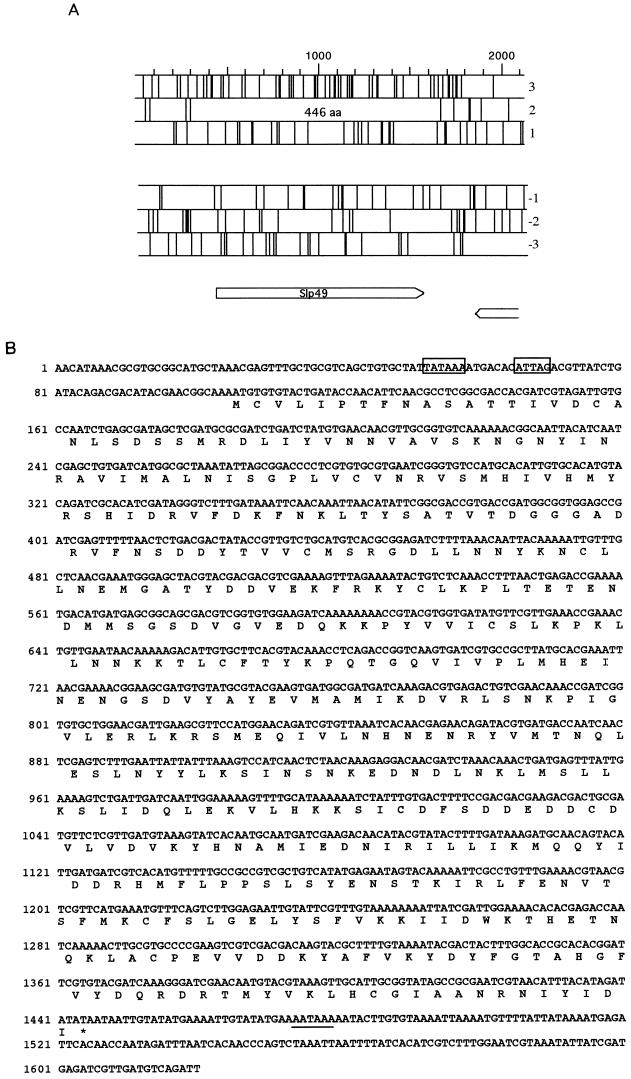

Sequencing of this fragment revealed the existence of only one complete ORF, capable of encoding a polypeptide of 446 amino acids and a molecular mass of about 49 kDa (Fig. 3). This ORF is preceded by a putative TATA box element and by the late motif initiator sequence ATTAG (2) at positions −53 and −40 upstream of the ORF start, respectively (Fig. 3B, boxes). Also, a putative polyadenylation signal was found 28 bp 3′ of the termination codon (Fig. 3B, underlined). We designated this putative SlNPV gene Slp49.

FIG. 3.

ORF analysis of the SlNPV genome, at map units 37.0 to 38.7, and sequence of the Slp49 gene. (A) Diagram of ORFs in six reading frames. Vertical bars indicate stop codons. The location of the 446-amino-acid (aa) product corresponding to SLP49 is labeled. ORFs encoding products longer than 100 amino acids are indicated by open arrows. (B) Nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence of SLP49. The early TATA box and a late transcriptional start site are indicated (open squares). A polyadenylation signal is underlined.

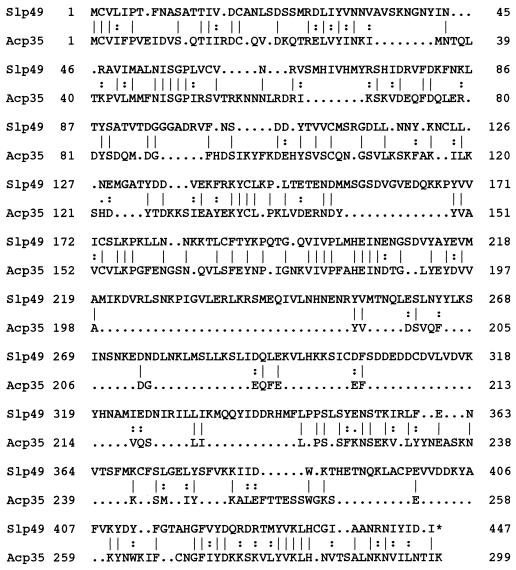

The polypeptide encoded by Slp49 has 48.8% amino acid identity and 66.8% similarity to the product of p35, the apoptotic suppressor gene of AcMNPV. Alignment of SLP49 and P35 revealed two main homology blocks at the N termini (amino acids 1 to 219 and 1 to 198, respectively) and at the C termini (amino acids 346 to 446 and 219 to 299, respectively) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of Slp49 and p35 predicted amino acid sequences. The alignment was performed with the GAP program (11). The P35 sequence was reported previously (13). Horizontal dots indicate gaps made to optimize the alignment. Vertical bars, identical amino acids; vertical dots, similar amino acids.

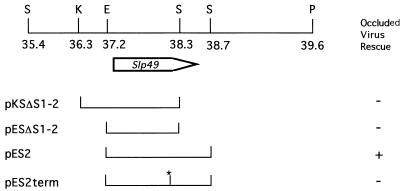

P35 of AcMNPV and BmNPV are polypeptides of 299 amino acids, in contrast to Slp49, which is 446 amino acids. To investigate if the intact 3′ end of Slp49, including the putative SLP49 C terminus, was required to rescue the infectivity of vΔP35K/pol+, we prepared two different deletion mutants (pKSΔS1-2 and pESΔS1-2) and one premature termination mutant (pES2term) with mutations in the Slp49 ORF (Fig. 5). None of the mutants displayed occluded-virus rescue activity (Fig. 5), suggesting that the 3′-end of the gene was required for Slp49 function.

FIG. 5.

Contribution of the Slp49 3′ end and SLP49 C terminus to the rescue of the replication of vΔ35K/pol+. The plasmids, pES2 bearing the complete Slp49 ORF, pESΔS1-2 and pKSΔS1-2, with the Slp49 3′ end deleted, and pESterm, displaying a frameshift causing a mutation in SLP49 amino acid 352 resulting in termination of the peptide at amino acid 364, were cotransfected separately with vΔP35K/pol+ DNA. Success (+) or failure (−) to rescue vΔ35K/pol+ replication was monitored as indicated in Fig. 2. S, SalI; K, KpnI; E, EcoRI; P, PstI.

Recombinant AcMNPVs expressing Slp49.

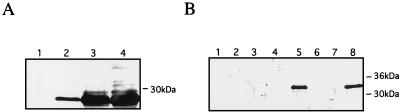

Recombinant AcMNPVs exhibiting the occlusion-positive phenotype were isolated from the extracellular medium derived from cotransfections performed with vΔP35K/pol+ DNA and either cosmid C50 or plasmids pKP and pKS2 (Fig. 2C). The recombinant viruses were designated vAcp491 and vAcp492, vAcp493 and vAcp494, and vAcp495 and vAcp496 (two recombinants per transfection). Infection of SF9 cells with these viruses resulted in polyhedrin synthesis at steady-state levels comparable to infection with wild-type AcMNPV, as detected by immunoblot analysis of extracts from infected cells (shown for the recombinant vAcp496 in Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 4). vΔP35K/pol+-infected cells showed much lower levels of polyhedrin, detected after prolonged incubation of the blot with the chromogenic substrate (lane 2). Also, as expected, no synthesis of P35 was detected in vΔP35K/pol+- or vAcp496-infected cells (Fig. 6B, lanes 3, 4, 6, and 7) or in mock-infected cells (lanes 1 and 2), in contrast to wild-type-AcMNPV-infected cells (lanes 5 and 8).

FIG. 6.

Infection of SF9 cells with a recombinant virus bearing the Slp49 gene. (A) Extracts from SF9 cells (4 × 105) were mock infected (lane 1) or infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 with vΔ35K/pol+, vAcp496, or AcMNPV (lanes 2, 3, and 4, respectively), harvested at 48 h after infection, and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis with anti-polyhedrin antiserum (7). (B) Extracts from SF9 cells were mock infected (lanes 1 and 2) or infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 with vΔP35K/pol+ (lanes 3 and 6) or vAcp496 (lanes 4 and 7) or AcMNPV (lanes 5 and 8). The cells were harvested 12 and 24 h later (lanes 1 and 3 to 5 and lanes 2 and 6 to 8, respectively) and analyzed as in panel A with anti-P35 antiserum. Molecular mass markers are indicated on the right.

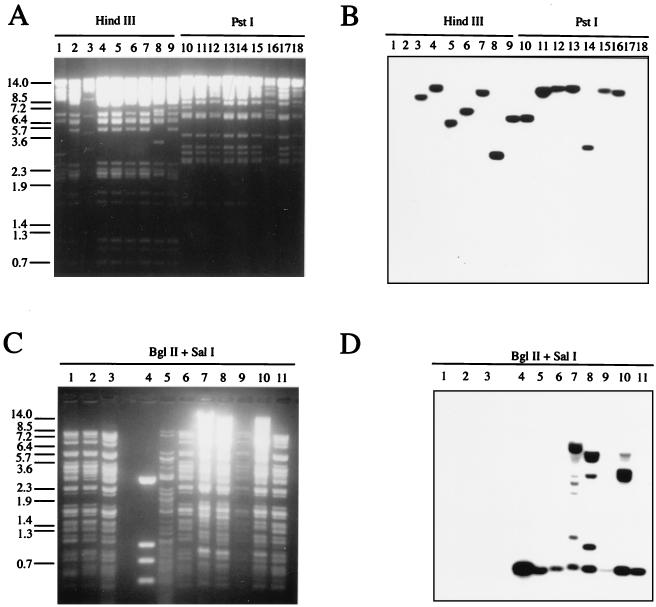

Genomic DNAs from the recombinants vAcp491 to vAcp496 were subjected to restriction enzyme digestion with HindIII and PstI followed by Southern blot hybridization (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 4 to 9 and 10 to 15, respectively). All of them (vAcp491 to vAcp496) bore DNA fragments that hybridized to a 32P-labeled Slp49 DNA probe (Fig. 7B, lanes 4 to 9 and 10 to 15). AcMNPV or vΔP35K/pol+-restricted DNAs did not react with that probe (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 1 and 18 and lanes 2 and 17, respectively). SlNPV genomic DNA was positive in the hybridization (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 3 and 16). Moreover, BglII-SalI digestion of genomic DNA of the above recombinants released an 856-bp fragment (Fig. 7C and D, lanes 6 to 11) characteristic of Slp49 (lanes 4 and 5). That fragment was absent in the genomes of wild-type AcMNPV, vΔP35K/LacZ, and vΔP35K/pol+ (lanes 1, 2 and 3, respectively).

FIG. 7.

vAc-Slp49 recombinants bear the Slp49 gene. Restriction enzyme digestion (A and C) and Southern blot analysis (B and D). (A and B) HindIII or PstI-digested DNA (indicated at the top of the figure) from AcMNPV (lanes 1 and 18), vΔ35K/pol+ (lanes 2 and 17), SlNPV (lanes 3 and 16), or polyhedron-positive-phenotype recombinants vAcp491 to vAcp496 (lanes 4 to 9 and lanes 10 to 15). (C and D) BglII-SalI-digested DNA from AcMNPV (lane 1), vΔ35K/LacZ (lane 2), vΔ35K/pol+ (lane 3), pES (lane 4), SlNPV (lane 5), or polyhedron-positive-phenotype recombinants vAcp491 to vAcp496 (lanes 6 to 11). A BglII-SalI 856-bp 32P-labeled Slp49 fragment (Fig. 3A) was used for hybridization.

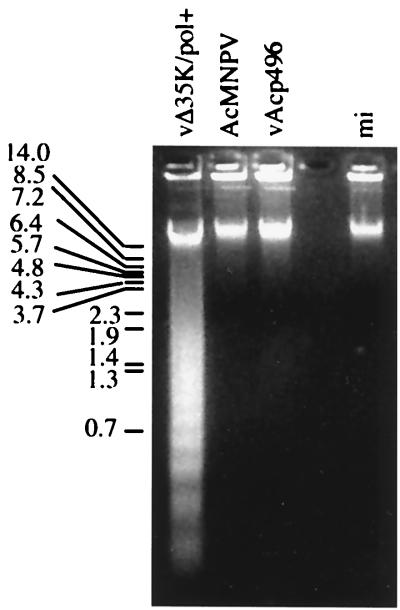

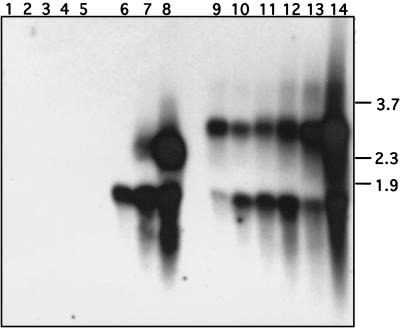

Infection of SF9 cells with vΔP35K/pol+ induced apoptosis displaying an oligonucleosome ladder characteristic of fragmented DNA (Fig. 8, lane 1), in contrast to infection with recombinant vAcp496 bearing the Slp49 gene (lane 3) or wild-type AcMNPV (lane 2). Control mock-infected cells did not show the oligonucleosomal ladder (lane 5). Concomitantly, a transcript of 1.5 kbp that hybridized to a Slp49-specific DNA-labeled probe was detected by Northern analysis of RNA extracted from SF9 cells infected with vAcp496 (Fig. 9, lanes 9 to 14). A similar transcript was present in SlNPV-infected cells (lanes 6 to 8). Control RNA from AcMNPV- or vΔP35K/pol+-infected cells (lanes 2 and 3 and lanes 4 and 5, respectively) or from mock-infected cells (lane 1), did not react with the Slp49 probe. Also, a larger transcript (about 2.9 kbp) reacted with the Slp49 probe in vAcp496-infected cells (Fig. 9) and SlNPV-infected cells showed a second Slp49 probe-positive transcript (about 2.6 kbp). Slp49 transcripts were detected first at 3 h after vAcp496 infection of SF9 cells (Fig. 9, lane 9) and 6 h after infection with SlNPV (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

vAcp496 suppresses apoptosis in SF9 cells. DNA extracted from the cells infected with vΔ35K/pol+, AcMNPV, or vAcp496 (indicated at the top of each lane) was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. mi, mock-infected cells. Size markers are indicated on the left.

FIG. 9.

Temporal analysis of Slp49 transcription in SlNPV- and vAcp496-infected SF9 cells. A Northern blot of total RNA extracted from mock-infected cells (lane 1) or cells infected with AcMNPV (lanes 2 and 3), vΔ35K/pol+ (lanes 4 and 5), SlNPV (lanes 6 to 8), or vAcp496 (lanes 9 to 14) is shown. RNA was extracted at 3 h (lane 9), 6 h (lane 10), 9 h (lane 11), 12 h (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 12), 18 h (lanes 7 and 13), and 24 h (lanes 3, 5, 8, and 14) after infection. The 32P-labeled Slp49 fragment used for hybridization was the same as in Fig. 7. Size markers (in kilobase pairs) are indicated on the right.

DISCUSSION

We identified a gene of SlNPV, Slp49, which blocks apoptosis induced by infection of SF9 cells with vΔP35K/pol+, a p35-deficient mutant of AcMNPV. Slp49-bearing plasmids were able to rescue the replication of vΔP35K/pol+ (Fig. 2) and donate the Slp49 gene to vΔP35K/pol+ recombinants, blocking apoptosis of SF9 cells (Fig. 7 and 9).

Slp49 encodes a predicted 49-kDa polypeptide, SLP49. The SLP49 amino acid sequence has 48.8% identity and 66.8% similarity with P35, the apoptotic suppressor of AcMNPV. The homology between SLP49 and P35 is concentrated in two major blocks located at the N termini (amino acids 1 to 219 and 1 to 198, respectively) and at the C termini (amino acids 346 to 446 and 219 to 299, respectively) of the polypeptides (Fig. 4). Interestingly the N-terminal half of P35, between amino acids 1 and 130, was very sensitive to insertional mutagenesis, resulting in loss of the ability to rescue a p35-deficient mutant of AcMNPV (3).

SLP49 is larger than P35 from AcMNPV (13) or BmNPV (20). A shorter SLP49, obtained by frame shift mutation of SLP49 at amino acid 352, failed to complement the replication of vΔP35K/pol+ (Fig. 5), indicating that the predicted C terminus of the protein is important for its function. The amino acid sequence between SLP49 amino acids 268 and 345 is not present in P35, and its contribution to SLP49 function remains to be elucidated. It may confer specificity to the protein in its interaction with other viral or host proteins.

SLP49 displays the motif TVTDX (X = G; N-terminal sequence underlined) at amino acids 90 to 94, similar to the P4 to P1 sequence N′-terminal to the D-X peptide cleavage site recognized by death caspases (26, 39). Similar sequence motifs are present in caspase inhibitors like P35 (DQMDG in A. californica P35; DKIDG in B. mori P35) (3, 5, 28, 34, 39) or short peptides (YVADG in interleukin-1β) (34) in S. frugiperda caspase-1-processing sites (TETDG) (1) and in caspase targets (6, 22). Although other putative caspase recognition sites (reviewed in reference 26) such as SRGDX (X = L) at amino acids 112 to 115 are present in SLP49, the SLP49-P35 alignment (Fig. 4) suggests that TVTDG may be the preferred caspase-cleavable site, given that it is in a conserved position with respect to the P35 recognition site. Experiments designed to assess that assumption are in progress (see below).

Taken together, the above data suggest that SLP49 may block apoptosis by inhibiting death caspases. An intriguing question is if SLP49 will show wide apoptosis suppression ability by being an inhibitor of a broad spectrum of caspases like P35. We will address this question by (i) overexpressing Slp49 and studying its ability to compete with various caspase-specific substrates (3, 5, 39) and (ii) studying caspase-mediated cleavage of SLP49.

An Slp49 1.5-kbp transcript was present in SlNPV- and vAc496-infected SF9 cells (Fig. 9). This transcript was prominent 12 h after SlNPV infection, suggesting that the inhibitory function of Slp49 may coincide with caspase activation, detectable at the onset of viral DNA replication. It was shown that higher steady-state levels of P35 and caspase inhibition by P35 cleavage coincide with the initiation of AcMNPV DNA synthesis (14, 21). Also, a 2.6-kbp transcript and a 2.9-kbp transcript were detected by the Slp49 probe, in SlNPV- and vAc496-infected SF9 cells, respectively. Since a double-stranded DNA-labeled probe was used for hybridization, it is conceivable that larger transcripts corresponding to adjacent genes (like the cathepsin gene for SlNPV, located 5′ upstream of Slp49 [11a]) were reacting with it.

Is Slp49 essential for SlNPV replication? To answer this question, we will attempt to isolate Slp49-deficient viable mutants.

Finally, the discovery of Slp49 suggests that more p35-like genes may exist in baculoviruses and probably in the animal kingdom. The sequence similarities found between p35 and Slp49 may provide clues that will enable the design of degenerate primers to attempt the identification of those p35-like genes, e.g., by PCR-mediated approaches.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gennadii Polubessov, Plant Genetics Department, The Weizmann Institute of Science, for assistance with computer analysis.

We acknowledge support for this research by the Israel Science Foundation under grant 398/96-1 to N.C.

Footnotes

Contribution 525/98 from the Agricultural Research Organization, The Volcani Center, Bet Dagan, Israel.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad M, Srinivasula S M, Wang L, Litwack G, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Almemri E S. Spodoptera frugiperda caspase-1, a novel insect death protease that cleaves the nuclear immunophilin FKBP46, is the target of the baculovirus antiapoptotic protein p35. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1421–1424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayres M D, Howard S C, Kuzio J, Lopez-Ferber M, Possee R D. The complete DNA sequence of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1994;202:586–605. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertin J, Mendrysa S M, Lacount D J, Gaur S, Krebs J F, Armstrong R C, Tomaselli K J, Friesen P D. Apoptotic suppression by baculovirus p35 involves cleavage by and inhibition of a virus-induced ced-3/ice-like protease. J Virol. 1996;70:6251–6259. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6251-6259.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaum M J, Clem R J, Miller L K. An apoptosis-inhibiting gene from a nuclear polyhedrosis virus encoding a polypeptide with Cys/His sequence motif. J Virol. 1994;68:2521–2528. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2521-2528.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bump N J, Hackett M, Hugunin M, Seshagiri S, Brady K, Chen P, Ferenz C, Franklin S, Ghayur T, Li P, Licari P, Mankovich J, Shi L F, Greenberg A H, Miller L K, Wong W W. Inhibition of ice family proteases by baculovirus antiapoptotic protein p35. Science. 1995;269:1885–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.7569933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casciola-Rosen L, Nicholson D W, Chong T, Rowan K R, Thornberry N A, Miller D K, Rosen A. Apopain/CPP32 cleaves proteins that are essential for cellular repair: a fundamental principle of apoptotic death. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1957–1964. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chejanovsky N, Gershburg E. The wild-type Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus induces apoptosis of Spodoptera littoralis cells. Virology. 1995;209:519–525. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chejanovsky N, Zilberberg N, Rivkin H, Zlotkin E, Gurevitz M. Functional expression of an alpha anti-insect scorpion neurotoxin in insect cells and lepidopterous larvae. FEBS Lett. 1995;376:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clem R J, Miller L K. Control of programmed cell death by the baculovirus genes p35 and iap. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5212–5222. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crook N E, Clem R J, Miller L K. An apoptosis-inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger-like motif. J Virol. 1993;67:2168–2174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2168-2174.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux J D, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Du, Q., and N. Chejanovsky. Unpublished data.

- 12.Duckett C S, Nava V E, Gedrich R W, Clem R J, Vandongen J L, Gilfillan M C, Shiels H, Hardwick J M, Thompson C B. A conserved family of cellular genes related to the baculovirus iap gene and encoding apoptosis inhibitors. EMBO J. 1996;15:2685–2694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friesen P D, Miller L K. Divergent transcription of early 35- and 94-kilodalton protein genes encoded by the HindIII K genome fragment of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Virol. 1987;61:2264–2272. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.7.2264-2272.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gershburg E, Rivkin H, Chejanovsky N. Expression of the Autographa californica M nuclear polyhedrosis virus apoptotic suppressor gene p35 in nonpermissive Spodoptera littoralis cells. J Virol. 1997;71:7593–7599. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7593-7599.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hay B A, Wassarman D A, Rubin G M. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell. 1995;83:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hershberger P A, Dickson J A, Friesen P D. Site-specific mutagenesis of the 35-kilodalton protein gene encoded by Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: cell line-specific effects on virus replication. J Virol. 1992;66:5525–5533. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5525-5533.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hershberger P A, LaCount D J, Friesen P D. The apoptotic suppressor P35 is required early during baculovirus replication and is targeted to the cytosol of infected cells. J Virol. 1994;68:3467–3477. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3467-3477.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hink W F. Established insect cell line from cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni. Nature (London) 1970;225:466–467. doi: 10.1038/226466b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobson M D, Weill M, Raff M C. Programmed cell death in animal development. Cell. 1997;88:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamita S G, Majima K, Maeda S. Identification and characterization of the p35 gene of Bombyx mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus that prevents virus-induced apoptosis. J Virol. 1993;64:455–463. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.455-463.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaCount D J, Friesen P D. Role of early and late replication events in induction of apoptosis by baculoviruses. J Virol. 1997;71:1530–1537. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1530-1537.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazebnik Y A, Kaufmann S H, Desnoyers S, Poirier G G, Earnshaw W C. Cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature (London) 1994;371:346–347. doi: 10.1038/371346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LIston P, Roy N, Tamai K, Lefebvre C, Baird S, Chertonhorvat G, Farahani R, Mclean M, Ikeda J E, Mackenzie A, Korneluk R G. Suppression of apoptosis in mammalian cells by NAIP and a related family of iap genes. Nature (London) 1996;379:349–353. doi: 10.1038/379349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller L K. Baculovirus interaction with host apoptotic pathways. J Cell Physiol. 1997;173:178–182. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199711)173:2<178::AID-JCP17>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholson D W, Thornberry N A. Caspases: killer proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seshagiri S, Miller L K. Baculovirus inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) block activation of Sf-caspase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13606–13611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith G E, Summers M D. Analysis of baculovirus genomes with restriction endonucleases. Virology. 1978;98:517–527. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steller H. Mechanisms and genes of cellular suicide. Science. 1995;267:1445–1449. doi: 10.1126/science.7878463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Summers M D, Smith G E. A manual of methods for baculovirus vectors and insect cell culture procedures. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station bulletin 1555. College Station, Tex: Texas Agricultural Experiment Station; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teodoro J G, Branton P. Regulation of apoptosis by viral gene products. J Virol. 1997;71:1739–1746. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1739-1746.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thiem S M, Du X L, Quentin M E, Berner M M. Identification of a baculovirus gene that promotes Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus replication in a nonpermissive insect cell line. J Virol. 1996;70:2221–2229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2221-2229.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thornberry N A, Molineaux S M. Interleukin-1β converting enzyme: a novel cystein protease required for IL-1β production and implicated in programmed cell death. Protein Sci. 1995;4:3–12. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thornberry N A, Rosen A, Nicholson D W. Control of apoptosis by proteases. Adv Pharmacol. 1997;41:155–177. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toister-Achituv M, Faktor O. Transcriptional analysis and promoter activity of the Spodoptera littoralis multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus ecdysteroid UDP-glucosyltransferase gene. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:487–491. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-2-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uren A G, Pakusch M, Hawkins C J, Puls K L, Vaux D L. Cloning and expression of apoptosis inhibitory protein homologs that function to inhibit apoptosis and/or bind tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4974–4978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaux D L, Strasser A. The molecular biology of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2239–2244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xue D, Horvitz H R. Inhibition of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell-death protease CED-3 by a CED-3 cleavage site in baculovirus p35 protein. Nature (London) 1995;377:248–251. doi: 10.1038/377248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]