Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to understand how capacity building programmes (CBPs) of district health managers (DHMs) have been designed, delivered and evaluated in sub-Saharan Africa. We focused on identifying the underlying assumptions behind leadership and management CBPs at the district level.

Design

Scoping review.

Data sources

We searched five electronic databases (MEDLINE, Health Systems Evidence, Wiley Online Library, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar) on 6 April 2021 and 13 October 2022. We also searched for grey literature and used citation tracking.

Eligibility criteria

We included all primary studies (1) reporting leadership or management capacity building of DHMs, (2) in sub-Saharan Africa, (3) written in English or French and (4) published between 1 January 1987 and 13 October 2022.

Data extraction and synthesis

Three independent reviewers extracted data from included articles. We used the best fit framework synthesis approach to identify an a priori framework that guided data coding, analysis and synthesis. We also conducted an inductive analysis of data that could not be coded against the a priori framework.

Results

We identified 2523 papers and ultimately included 44 papers after screening and assessment for eligibility. Key findings included (1) a scarcity of explicit theories underlying CBPs, (2) a diversity of learning approaches with increasing use of the action learning approach, (3) a diversity of content with a focus on management rather than leadership functions and (4) a diversity of evaluation methods with limited use of theory-driven designs to evaluate leadership and management capacity building interventions.

Conclusion

This review highlights the need for explicit and well-articulated programme theories for leadership and management development interventions and the need for strengthening their evaluation using theory-driven designs that fit the complexity of health systems.

Keywords: health services administration & management, public health, health equity, health services accessibility

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

We have used a systematic approach to search for a best-fit framework against which to code the data and a comprehensive strategy to search for primary studies.

Three reviewers performed the screening and data extraction.

We did not appraise the quality of the included papers, as scoping reviews do not require a quality appraisal.

We may have missed other relevant literature not available publicly or published in languages other than English or French.

We have made some trade-offs between comprehensiveness and feasibility, as is often the case in scoping reviews.

Introduction

Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa failed to achieve the health-related millennium development goals.1 The continent accounts for almost half of all deaths of children under-5 years worldwide and the highest maternal mortality ratio. It bears the highest burden of HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis in the world.1 2 This is partly due to health system weaknesses, which may be attributable to multiple causes,3 including weak leadership and management, especially at the district level.3–6

The role of leadership and management in improving the performance of health systems is widely recognised in the literature.7–11 Effective leadership and management at the district level are crucial since this is the operational level where national policies and resources are translated into effective services and where responsiveness to local needs can be ensured.12–15 Building leadership and management capacity of district health managers (DHMs) is likely to improve the stewardship of the district health system and is required to ensure the achievement of better health outcomes,7 11 16 17 particularly the health-related sustainable development goals.18

Capacity building programmes (CBPs) in the health sector are complex.11 19 They seek to produce change at the individual, organisational and systemic level.4 14 20–22 They involve the interactions between several actors, including policymakers, managers, providers, funders, patients, communities, etc. These actors belong to various institutions or social subsystems, and have different values, norms, decision spaces, and possibly conflicting agendas and expectations.23–26

Health districts are complex adaptive systems.4 13 19 They consist of interacting elements or subunits (ie, actors at first-line health facilities, hospitals, district health management teams, community, etc). Health districts are open systems which are embedded in a broader (social, political and economic) environment with which they interact continuously. Consequently, health districts adapt to changes in the environment and co-evolve with other systems. From these interactions may arise behaviours that may be unpredictable and non-linear. History also shapes these emergent patterns.27–31 This complexity has consequences for capacity building: programmes that work in one setting will not necessarily work in another or may not function in the same location later.32

Capacity building emerged in the development aid field in the 1970s.33 It is considered an elusive and broad concept and has been described as an umbrella or multidimensional term that is associated with a range of (sometimes opposite) meanings among academics and practitioners.2 21 23 34–39 Often, the terms capacity building and capacity development are used interchangeably.21 40 Some authors prefer to use capacity development to stress the importance of ownership by partner organisations and to emphasise the importance of existing and potential capacities.33 41 Some authors simplistically refer to training as capacity building.17 42 43 Such reductionist view tends to restrict capacity building to its tangible or measurable elements (eg, knowledge and skills, organisational structure, procedures and resources).42 44–47 In contrast, other scholars37 39 48 consider that capacity building should be a systemic approach that also considers less tangible aspects, such as leadership, motivation and organisational culture.38 49

The conceptual heterogeneity of capacity building, its various interpretations, and the tensions between holistic and reductionist perspectives may explain the diversity of CBP designs, approaches, models and tools.2 11 21 23 39 This also contributes to the methodological challenges related to CBP process evaluation38 and to their effectiveness on organisational performance.20 21 37 50 A good deal of the literature of CBP evaluation is based on pretest and post-test only and many programmes are not evaluated at all.20 51 Little attention has been paid to the underlying theories, models or frameworks underpinning CBP. In the field of health, few studies set out to assess what works, how and why. Exceptions include papers by Kwamie et al,4 Prashanth et al24 and Orgill et al.49

The objectives of this review were to understand how CBPs of DHMs have been designed, delivered and evaluated in sub-Saharan Africa. We focused on identifying the underlying assumptions and evidence behind CBPs at the district level. We assessed how far these assumptions and contextual conditions are discussed and, if so, what could be learnt from these studies.

Methods

We adopted the scoping review methodology, which is appropriate for a topic that is complex and for which there is a high degree of conceptual heterogeneity.52 53 We followed the five steps proposed by Arksey and O’Malley53 for a scoping review and subsequent recommendations.54 55 These steps are (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. A protocol review (online supplemental text 1) was developed and approved by the research team.

bmjopen-2022-071344supp003.pdf (332.5KB, pdf)

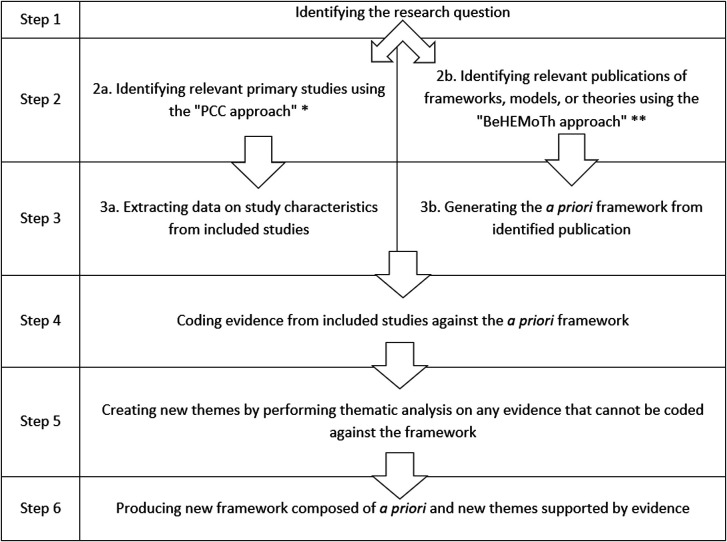

We combined the scoping review approach with the ‘best fit’ framework synthesis, which provides a practical and rapid method for qualitative evidence synthesis.56 57 It allows for both a deductive analysis using an a priori framework and an inductive analysis based on new themes from selected studies that are not part of the a priori framework.56 57

The process of the scoping review and best-fit framework synthesis is shown in figure 1. Based on the research questions (step 1), we searched for and selected primary studies (step 2a). Concurrently, we searched for and selected frameworks, models or theories (step 2b). Next, we summarised the characteristics of primary studies included (step 3a) and generated an a priori coding framework from the selected frameworks, models or theories (step 3b). We then coded data from primary studies against the a priori coding framework (step 4). We performed a thematic analysis for data that could not be coded against the a priori framework (step 5). This resulted in a new framework comprising a priori and new themes supported by the data (step 6).

Figure 1.

Process of best fit framework synthesis.56 121 BeHEMoTh, behaviour of change, heath content, exclusion models of theories; PCC, population concept and context.

Step 1: identifying the research questions

Our review aimed at answering the following research questions: (1) how has capacity building of DHMs in sub-Saharan Africa been designed in terms of theory, mode, level, approach and contents?; (2) how have such CBPs been delivered? and (3) how have such CBPs been evaluated and what were the outcomes? The answers to these questions allowed us to map the designs, approaches, underlying theories, approaches content, outcomes, methodological issues and research gaps.

Step 2: identifying relevant studies

Identifying primary studies

We used four databases (Medline/PubMed, Health Systems Evidence, Wiley Online Library, Cochrane Library) and Google Scholar. We also searched for grey literature from international organisations that support CBPs in health systems in sub-Saharan Africa (incl. WHO, European Union, USAID, Management Sciences for Health, Belgian Development Agency, etc). In addition, we used the citation tracking to identify papers.

Our search strategy was based on the Joanna Briggs Institute’s ‘Population Concept Context approach’58:

Population: DHMs are health officers who work in local health systems and spend some of their time in management and/or administrative roles. They can have various professional profiles (physicians, nurses, pharmacists, administrators, etc) and play different roles, possibly combining them, within the district health system (district medical officers, hospital directors, clinicians, nursing officers, nurse supervisors, etc).59

Concept: the main concept is ‘capacity building’, that is, any programme or intervention whose aim is to enable an individual or organisation to achieve its stated objectives.37 CBP comprises both hard or measurable (eg, knowledge and skills, organisational structure, procedures and resources, etc) and soft or intangible (eg, leadership, motivation and organisational culture) components. Search terms included “capacity building” or ‘capacity development’ or ‘capacity strengthening’ and ‘health district management’ or ‘leadership development’.

Context: sub-Sahara African countries according to the World Bank classification.60

Table 1 outlines the search strategies used in PubMed and other electronic databases on 6 April 2021. On 13 October 2022, we performed additional searches in all electronic databases to update the included studies.

Table 1.

Search strategies for primary studies

| Databases | Search strategies |

| MEDLINE/PUBMED | (((((((((((((“Health Personnel”(Mesh)) OR (“District health management teams”)) OR (“Institutional Management Teams” (Mesh))) OR (“Public Health Administration” (Mesh))) OR (District Health manage*)) OR (“District medical officers”)) OR (“Nursing officers”)) OR (“Nursing directors”)) OR (“Nurse supervisors”)) OR (“Nurse Administrators” (Mesh))) OR (“District health administrators”))) AND (((((((“Capacity Building”(Mesh)) OR (“Capacity Development”)) OR (Capacity Strengthening)) OR (District Health Management Development)) OR (District Health Leadership Development)) OR (District Health System Strengthening)))) AND ((((“Sub Saharan Africa”) OR (“Africa South of the Sahara”(Mesh))) OR (Angola OR Benin OR Botswana OR “Burkina Faso” OR Burundi OR Cameroon OR “Cape Verde” OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Comoros OR “Democratic Republic of Congo” OR Zaire OR “Republic of Congo” OR “Ivory Coast” OR Djibouti OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Gabon OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR “Guinea-Bissau” OR Kenya OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Libya OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Rwanda OR “Sao Tomé and Principe” OR Senegal OR Seychelles OR “Sierra Leone” OR Somali OR “South Africa” OR Sudan OR South Sudan OR Swaziland OR Tanzania OR Togo OR Uganda OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe))) Filters: Humans, English, French, from 1987/1/1–2021/04/06 and from 2021/04/07–2022/10/13 |

| Wiley Online Library | Health District Systems) AND (Management OR Leadership) AND (Capacity Building OR Capacity Development OR Capacity Strengthening) AND (Sub Saharan Africa) Filters: MEDICAL SCIENCE, Journals, 1987–2021 and 2021–2022 |

| Cochrane Library | District Health Systems in Title Abstract Keyword AND management in Title Abstract Keyword OR leadership in Title Abstract Keyword AND capacity building in Title Abstract Keyword AND “sub-Saharan Africa” in Title Abstract Keyword |

| Health Systems Evidence | Health District AND (Manage* OR Leader*) AND Capacity Building |

| Google Scholar | (Health District Systems) AND (Management OR Leadership) AND (Capacity Building OR Capacity Development OR Capacity Strengthening) AND (Sub-Saharan Africa) |

Identifying relevant frameworks, models and theories

We used PubMed and Google Scholar to search for suitable published theories or models to generate the a priori framework for synthesising data from primary studies to be selected. We based our search strategy on the BeHEMoTh approach56 58:

Behaviour of interest (Be): management and leadership capacity of health workers.

Health context (H): CBPs, health systems or public health.

Exclusions (E): non-theoretical/technical models, that is, terms often used in biomedical research such as ‘epidemiological model’, ‘disease model’, ‘care model’ or ‘statistical model’ that do not fit the theoretical focus of the best fit framework strategy.

Models of theories (MoTh): theory, model, concept, and framework.

Table 2 provides the search strategy in PubMed—(Be AND H AND MoTh) NOT E.

Table 2.

MEDLINE/PUBMED search strategy for models, theories or frameworks

| Terms | Search strategy | |

| Behaviour of interest (Be) | Management and leadership capacity of health workers | (“health”) AND (“manage*” OR “leader*” OR “work*") |

| Health context (H) | Capacity building programmes, health systems or public health | (“capacity building” OR “capacity-building” OR “capacity development” OR “capacity strengthening”) AND (“health systems” OR “public health”) |

| Exclusion (E) | Non-theoretical/technical models | “epidemiological model” or “disease model” or “care model” or “statistical model” |

| Models of theories (MoTh) | Theory, model, concept, framework | model* OR theor* OR concept* OR framework* |

| ((((“health”) AND (“manage*” OR “leader*” OR “work*“)) AND ((“capacity building” OR “capacity-building” OR “capacity development” OR “capacity strengthening”) AND (“health systems” OR “public health”))) NOT (“epidemiological model” or “disease model” or “care model” or “statistical model”)) AND (model* OR theor* OR concept* OR framework*) Filters: English, French, Humans | ||

Step 3: study selection

Selection of primary studies

We selected papers based on their titles and abstracts.61 In the next step, three reviewers (SB, JE and CK) examined the full texts of the articles independently to decide on their final selection on the basis of the inclusion criteria (table 3). We selected all studies that met the inclusion criteria regardless of their quality, as we aimed to map key concepts, types of evidence and research gaps.52 53 Disagreements among reviewers were solved by consensus.54 We used the Rayyan software to manage the review process.

Table 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Type of paper | Papers reporting primary research published in peer-reviewed journals, working papers, intervention reports, research reports | Literature reviews, editorials, opinions, commentaries, workshop reports, conference abstracts, conference proceedings, research protocols |

| Content of paper (population, concept, context) | Studies related to DHM leadership and management CBPs in SSA countries | Studies related to other health workers, the management of specific diseases or waste management; and non-SSA countries |

| Language | Paper published in English or French | Paper published in another language than English and French |

| Time | Paper published from 1987* to 2022 | Paper published before 1987 |

*We chose this year in reference to the Harare declaration on strengthening district health systems.

CBPs, capacity building programmes; DHM, district health manager; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa.

Identification of frameworks, models and theories

Also here, we selected papers based on their titles and abstracts.61 Papers that met the following criteria were included (1) papers presenting a model, theory or framework that fit the research purpose, that is, allow the full description of design, implementation and evaluation of CBPs; (2) papers presenting a description, evaluation or test of a capacity building model, theory or framework with a focus on leadership or on overall management; and (3) papers published in English or French. Box 1 outlined the definitions of theories, models and frameworks used.62 63

Box 1. Definition of theories, models and frameworks from Bergeron et al62 63.

‘Theories include constructs or variables and predict the relationship between variables’.

‘Models are descriptive, simplification of a phenomenon and could include steps or phases’.

‘Frameworks include concepts, constructs or categories and identify the relationship between variables, but do not predict this relationship’.

Step 4: charting data

Generating the a priori framework

Based on the two selected models,64 65 we generated a list of a priori themes and codes related to the rationale, process (strategies, implementation and evaluation) and outcomes of CBPs (table 4). According to Labin et al,64 the need for conducting a CBP affects its process (design, implementation and evaluation), which, in turn, affects outcomes.

Table 4.

The coding framework

| Themes from original models | Codes | Definitions |

| Rationale for conducting capacity building programmes | Motivation | Trigger or motivating reasons for conducting a capacity building programme |

| Assumptions | Suppositions or hypotheses (explicit or implicit) that underlie the actors’ desire to engage in a capacity building programme | |

| Expectations | Intended outcomes or results expected from a capacity building programme | |

| Context | Key features of the environment in which the health organisation targeted by a capacity building programme is embedded | |

| Strategies of capacity building programmes | Theory | Any (explicit or implicit) theory that can inform the design, implementation and evaluation of a capacity building programme |

| Mode | How capacity building programme is provided: in-presence, online, written materials, etc | |

| Level | Capacity building programme entry point: individual, organisational and system levels. | |

| Approach | Teaching and learning methods: training, workshop, coaching, mentoring, supervision, technical assistance, community of practice, etc | |

| Content | Substance of capacity building programme activities | |

| Implementation of capacity building programmes | Actors | Providers or facilitators’ professional profile, participants’ professional profile |

| Duration | Time during which capacity building programme took place | |

| Barriers | Bottlenecks that hindered the achievement of expected outcomes | |

| Evaluation of capacity building programmes | Design and methods | Cross-sectional, case study, (quasi)experimental, pre-post, quantitative, qualitative, mix-methods, theory-driven, etc |

| Timeframe | Period within which evaluation is conducted: time after capacity building programme implementation or completion | |

| Evaluator position | Evaluator may be internal to (involved in) the programme or external (independent) to programme | |

| Outcomes of capacity building programmes | Individual outcomes | Knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours of health managers |

| Organisational outcomes | Leadership and management practices, organisational culture | |

| Population health outcomes | Access, quality and equity of healthcare and services | |

| Sustainability | Maintenance of capacity building programme activities and outcomes over time | |

| Unexpected outcomes | Unintended results: may be positive or negative | |

| Lessons learnt | Knowledge or understanding gained from capacity building programme process |

Data extraction

Using an Excel form, three reviewers (SB, JE and CK) extracted separately three groups of data from the selected studies: (1) study characteristics (author, year, country, type, objectives, design and methods); (2) data related to CBPs that were coded against the a priori framework and (3) new relevant data that did not fit the a priori codes. We compared results and merged when necessary.

Step 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

We described the main characteristics of the included studies using descriptive statistics. We carried out a deductive thematic analysis to summarise the main review findings from the a priori framework52 55 58 and an inductive thematic analysis to generate new themes from data that did not fit the a priori framework. We report the results according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines (online supplemental table 1).66

bmjopen-2022-071344supp001.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in this research.

Results

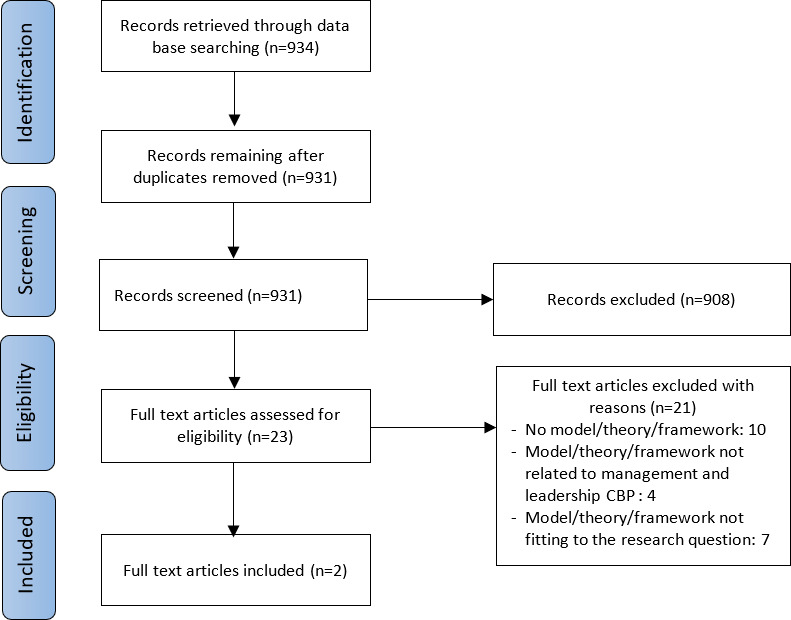

Selection of frameworks, models and theories

The search yielded 934 articles. After removing duplicates and screening records based on titles and abstracts, 23 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Two full-text articles met the inclusion criteria (figure 2). The two included papers reported on the models of evaluation capacity building: the multidisciplinary model of evaluation capacity building65 and the integrated model of evaluation capacity building.64 The two models have similarities as the second model development was largely inspired by the first model.

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart of the search for models, theories and frameworks. CBP, capacity building programme.

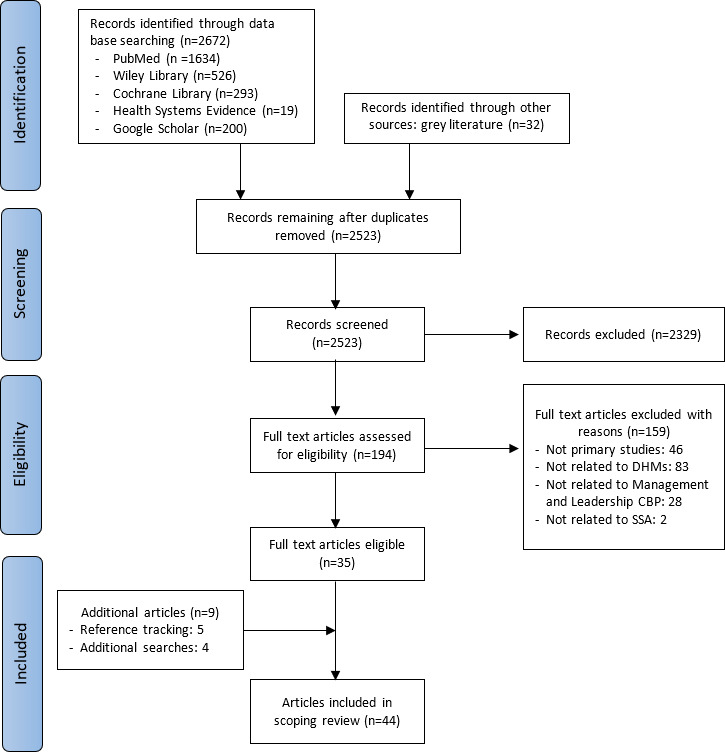

Selection of primary studies

We identified 2704 articles. After removing duplicates and screening records based on titles and abstracts, we assessed 194 full-text articles for eligibility. Thirty-five full-text articles met the inclusion criteria. Nine additional full-text articles were included after reference tracking (n=5) and additional searches (n=4). In total, 44 papers were included in this review (figure 3). Online supplemental table 2 provides the description of included papers.

Figure 3.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart for primary studies. CBP, capacity building programme; DHMs, district health managers; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa.

bmjopen-2022-071344supp002.pdf (253.6KB, pdf)

Characteristics of primary studies included

The characteristics of primary studies included in this review are summarised in table 5.

Table 5.

Characteristics of included papers

| Characteristics of included studies | Number | Percentage | References | |

| Years | 1991–2000 | 5 | 11 | 67–70 95 |

| 2001–2010 | 9 | 20 | 71–74 96 98 99 102 122 | |

| 2011–2020 | 24 | 55 | 4 9 17 19 75–86 91–94 97 101 103 105 | |

| 2021–2022 | 6 | 14 | 47 49 87 89 90 100 | |

| Languages | English | 41 | 93 | 4 9 17 19 47 49 67–87 89–99 101 102 122 |

| French | 3 | 7 | 100 103 105 | |

| Countries | Uganda | 8 | 18 | 19 67 75 76 78 86 87 97 |

| South Africa | 6 | 14 | 6 9 49 85 102 122 | |

| Ethiopia | 5 | 11 | 73 80 83 96 98 | |

| Ghana | 4 | 9 | 4 68 74 93 | |

| Kenya | 4 | 9 | 47 77 84 99 | |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 4 | 9 | 69 100 103 105 | |

| Tanzania | 3 | 7 | 72 91 95 | |

| Botswana | 2 | 5 | 94 101 | |

| Mozambique | 2 | 5 | 81 92 | |

| Liberia | 1 | 2 | 71 | |

| Zambia | 1 | 2 | 17 | |

| Gambia | 1 | 2 | 70 | |

| Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda | 1 | 2 | 79 | |

| Ghana, Malawi and Uganda | 2 | 5 | 89 90 | |

Rationale for conducting a CPB

Motivation, assumptions and expectations (goals)

A good deal of the literature included in this review have reported weak leadership and/or management capacities of DHMs as the most frequent reason for conducting CBPs. Weak leadership and/or management were considered the major causes of poor health outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries.4 6 19 49 67–88 Frequently mentioned causes of weak leadership and/or management capacity were (1) inadequate professional profiles of health managers (often being clinicians without formal training on leadership and management)17 73 75 81 89 90 and (2) inadequate efficacy of leadership and management courses (usually classroom-based and knowledge-focused instead of practice-based and providing know-how to deal with real-life situations).47 68 69 73 74

Twenty-three papers presented the assumptions underlying the CBPs. Most programmes assumed that strengthening the leadership and/or management knowledge, skills and practices of health managers would improve their leadership and/or management capacities. These improvements would, in turn, lead to improved health system performance and then better health outcomes.4 17 47 68 70 75–78 81–84 86 87 90–93 The CBPs were supposed to trigger health team members’ self-confidence to undertake good leadership and/or management practices which would, in turn, activate their job satisfaction, motivation and sense of ownership.68 91 93 The good management practices reported included: effective and efficient use of resources,70 83 86 92 priority setting and better planning,17 70 78 86 87 92 use of data for decision making,17 87 92 supervision of health workers,17 70 86 91 93 ensuring monitoring and evaluation,81 86 94 teamwork and regular meetings.17 49 70 89 The good leadership practices reported included creating a positive work climate,4 17 83 84 and relationship building among stakeholders.9 82

Thirty-seven articles outlined the objectives or expected outcomes of the programme. Analysis shows that they all refer to the improvement of either the management knowledge, skills and practices of DHMs4 17 49 68–73 75–77 81 82 84–87 89 95–97 or the leadership and management knowledge, skills and practices4 17 47 77 82–84 as the main outputs. The outcomes expected from these main outputs were the increase of health service access and coverage,77 78 93 97 the improvement of the (quality and equity of) health service delivery,47 67 75 80 83 84 89 93 96 98 99 the improvement of maternal and child health outcomes.72 75 76 78 87 97

Context of CPBs

The included studies identified various features of the context within which the programme took place. The most cited was the decentralisation from national (or regional) to the district (or subdistrict) level.9 19 47 49 67 70–72 75 76 78 79 81 84 87 90 92 96–98 100 However, seven studies reported narrow decision space of DHMs regarding financial and human resources.4 49 70 78 87 90 97 Three papers noted the persistence of a hierarchical organisational culture within the decentralisation setting.9 68 95 Other context features included resource constraints and issues (human, financial, equipment, infrastructures, drugs and other supplies),4 72 73 75 81 92 94 96 98 101 102 poor accessibility and availability of health services,72 93 conflicts and crisis.100 103

Capacity building strategies

Underlying theories, frameworks and models

None of the included papers explicitly refers to a theory underlying the reported CBP. Sixteen articles explicitly mentioned seven frameworks or models on which the reported programmes were based (table 6).

Table 6.

Capacity building frameworks or models

| Frameworks/Models | Description | Papers (n) | References |

| Participatory action research cycle | The cycle comprises four or five phases related to the problem-solving: problem diagnosis and action planning (plan), action (act), evaluation (observe) and specifying learning achieved (reflect) | 5 | 75 76 79 89 90 |

| Leadership and management competency framework | The framework focuses on core management or leadership skills of health managers, such as problem-solving, planning, resource management, monitoring and evaluation, strategic thinking | 3 | 47 71 79 |

| Leading and managing framework | The framework includes a set of practices organised into four leadership domains (scanning, focusing, aligning/mobilising and motivating) and four management domains (planning, organising, implementing, monitoring and evaluation) | 3 | 4 77 84 |

| Potter and Brough’s capacity pyramid framework | Systemic capacity-building consists of four levels of a pyramid of needs that contribute to improved performance: tools, skills, staff and infrastructure, structures and systems, and roles | 2 | 72 86 |

| Thinking environment principles | The thinking environment includes 10 elements related to behaviours, attitudes, values and beliefs that shape the culture and the relationships necessary for good team collaboration. These elements are attention, equality, ease, appreciation, encouragement, feelings, information, diversity, incisive questions and place | 1 | 9 |

| Attitudes, knowledge, skills and behaviours framework | The framework posits that relevant attitudes, knowledge and skills allow students to develop a personal framework of practice to act in and on the health system through various positive behaviours | 1 | 82 |

| Combination of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model and Mc Le Roy socio-ecological model of behaviour | The Kirkpatrick model consists of four levels which are reaction (participants’ reaction to training content and methods), learning (what participants learnt), behaviour (how well participants apply their training) and results (effects of training on the organisation’s outcomes). The Mc Le Roy’s socio-ecological behaviour model posits that personal, institutional and community factors shape behaviour | 1 | 17 |

An analysis of approaches used in other CBPs showed that most authors referred implicitly to the management competency framework and/or the participatory action research cycle.

Levels, modes and approaches

We found that CBPs reported in the included papers of this review had two entry points: the individual and organisational levels. Nine CBPs focused on strengthening individual health managers’ knowledge and skills.17 69 71 73 82 85 86 94 102 The remaining CBPs took an organisational entry point to strengthen the capacity of the health management teams to perform their managerial functions and achieve health outcomes.

All CBPs reported were delivered face-to-face, either in a specific room, at the workplace or alternating between the two. No online CBP was reported in the included papers of this review.

A diversity of methods was used (alone or in combination) to build health managers’ capacity. We summarised these approaches using the classification of Kerrigan and Luke88 in table 7: formal training, on-the-job training, action learning and non-formal training.

Table 7.

Approaches of capacity building programmes

| Approach | Description | Papers (n) | References |

| Action learning approach | This approach focuses primarily on the problem-solving cycle (plan, do, study and act) and emphasises action as the vehicle for learning.88 The process includes an alternating mix of workshops or classroom training, actual project implementation, on-the-ground coaching, mentoring or supervision, and review meetings to monitor progress and share experience and learning | 18 | 4 9 47 67 68 70 71 75 76 79 83–85 92 95 96 98 99 |

| On-the-job training | This approach aims at supporting health managers in carrying out their tasks through various approaches such as classroom training, on-site mentoring, coaching or supervision visits and technical assistance. | 9 | 69 72 81 86 93 94 101–103 |

| Mixed approaches | Combination of formal training (usually provided by academic institutions) with on-the-job training | 3 | 17 73 80 |

| Combination of formal training with action learning | 1 | 82 | |

| Combination action learning with on-the-job training | 1 | 91 |

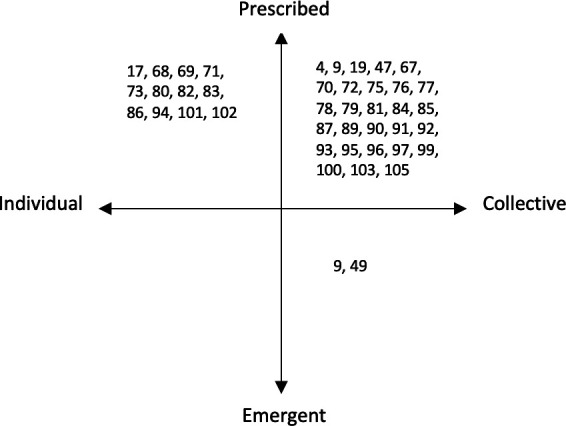

We analysed the CBP approach using Roger et al’s framework cited by Hartley and Hinksman104 to see to what extent the CBP approaches were individual or collective on the one hand and prescribed or emergent on the other. The prescribed approach refers to a blueprint approach or a normative process in which inputs (eg, competencies) and outputs (eg, standards, performance) required for leadership or management capacity development are specified. The emergent approach entails a dynamic, flexible or adaptable process that emerges from stakeholders’ interactions. We found that most CBP approaches were prescribed and collective,4 9 19 47 67 70 72 75–79 81 84 85 87 89–93 95–100 103 105 and prescribed and individual.17 68 69 71 73 80 82 83 86 94 101 102 The emergent and collective approach was marginal9 49 (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Capacity building programme approaches using Roger et al (2003) framework.

Learning content

Twenty-two papers specified the learning contents, which varied in terms of terminology and could be categorised under the headings outlined in table 8. This table indicated that the most prevalent learning contents were the problem-solving cycle, human resource management, financial management and leadership development.

Table 8.

Learning content

| References | Problem-solving cycle | HR management | Financial management | Leadership development | Strategic thinking and management | Hospital and health service delivery management | Monitoring, evaluation and HIMS | Supply chain and fleet management |

| Kanlisi68 | X | |||||||

| Conn 70 | X | |||||||

| De Brouwere and Van Balen69 | X | |||||||

| Omaswa et al67 | X | |||||||

| Uys et al102 | ||||||||

| Byleveld et al122 | ||||||||

| Bradley et al96 | X | X | X | |||||

| Gill et Bailey99 | X | X | ||||||

| Kebede et al73 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Rowe et al71 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Blanchard et al85 | X | |||||||

| Kebede et al80 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ledikwe et al94 | X | |||||||

| Kwamie et al4 | X | X | X | |||||

| Edwards et al81 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Balinda et al86 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Katahoire et al97 | X | |||||||

| Mutale et al17 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Doherty et al82 | X | X | ||||||

| Martineau et al79 | X | X | ||||||

| Desta et al83 | X | X | ||||||

| Total | 12 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

Other contents include governance in health,83 86 project management,17 122 supervision of HW,102 epidemiology and health research,73 80 health policy, ethics and law,73 80 complexity and system thinking82 and nursing management.80

HIMS, health information management system; HR, human resource; HW, health workers.

Implementation of CPBs

Actors: participants and providers

Participants in CBPs were mainly district health and hospital management team members. The composition of these teams varied from one country to another and was often not specified. Other participants included subdistrict management team members,9 75 93 facility managers and staff9 17 72 85 91 99 and district administrative and political leaders.67 76 The programmes were provided by facilitators from the Ministry of Health at the national, regional or district level,4 49 67 68 81 86 93 99 100 103 105 academic and research institutions,9 71 73 75 79 82 85 89 90 95 international non-governmental organisations72 94 or a mix of these institutions.17 78 84 87 92 96 97

Duration

The duration of the programme was highly variable, from 10 days to 8 years. We found 1 programme of less than 1 month,86 13 programmes of 1–12 months,4 17 68 69 71 77 81 82 84 85 95 96 102 8 programmes of 13–24 months49 67 70 73 79 83 94 97 and 8 programmes of more than 24 months.9 72 75 81 91–93 103

Barriers

Barriers to the successful implementation of CBPs mentioned by authors included human resource issues, such as staff shortage, staff turnover or staff mobility within or across districts,4 47 70 77 79 89 91 92 96 inadequate support from the national or provincial level,67 95 insufficient mentorship after course completion,17 82 insecurity,77 92 drop out of facilitators due to busy schedules,86 lack of funding,79 poor working conditions,47 the overlapping activities of vertical programmes that negatively affect the availability of supervisors and the regularity of supervisions visits100 and the negative influence of donors, such as imposing a standardised intervention with top-down decision making.70

Evaluation of CPBs

Approach, design and methods

Almost half of the included papers did not specify an explicit evaluation design. The study designs and data collection methods reported in the included study are summarised in table 9. Three studies were theory-based evaluations.4 49 92

Table 9.

Evaluation designs and data collection methods

| Papers (n) | References | ||

| Evaluation design | Case study | 9 | 4 49 72 86 92 95 98 103 105 |

| Prestudy and poststudy | 4 | 17 71 80 96 | |

| (Quasi-)experimental design | 5 | 47 77 84 87 91 | |

| Cross-sectional study | 4 | 83 85 93 100 | |

| Action learning design | 1 | 9 | |

| Data collection methods | Quantitative methods (checklists, questionnaires, pretraining and post-training test, data from health information management systems) | 13 | 47 71 78 80 81 83 84 87 91 93 96 100 102 |

| Qualitative methods (interviews, focus group discussions, observations and document reviews) | 14 | 4 9 19 49 72 75 76 86 88 89 92 97 101 103 | |

| Mixed-methods | 9 | 17 74 77 79 82 85 94 98 105 |

Seven studies used frameworks for evaluation purposes (table 10).

Table 10.

Frameworks/models used to assess capacity building programmes

| References | Frameworks/models used | Purposes |

| Kokku72 | Potter and Brough’s capacity building framework | To assess the Simanjiro Mother and Child Health Capacity Building project in Tanzania |

| Tetui et al75 | Competing values framework of Quinn | To assess the DHMs’ capacity strengthening within the MANIFEST (Maternal and Neonatal Implementation for Equitable Systems) project in Uganda |

| Martineau et al79 | Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model | To assess the effects of management development intervention within the PERFORM project in Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda |

| Adjei et al74 | Five core capabilities framework | To assess the capacity development at the district level of the health sector in Ghana |

| Byleveld et al88 | A leadership and management framework developed from the document review | To assess the DHMT members’ perceptions of the importance of 14 leadership and management competencies in South Africa |

| Chuy et al105 | A conceptual framework developed from the literature | To assess the coherence and relevance of provincial-level support to develop the capacity of DHMTs in the Democratic Republic of Congo |

| Bulthuis et al89 | CORRECT criteria to from WHO/ExpandNet | To assess the scalability of the PERFORM2Scale project in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda |

DHM, district health manager.

Evaluation timeframe

The evaluation of the reported CBPs adopted various timeframes. Some CBPs were evaluated during their implementation: five programmes after 0–12 months,68 75 78 88 89 six programmes after 13–24 months49 67 70 79 83 97 and six programmes after more than 24 months.75 82 87 91 92 101 Other CBPs were evaluated after their completion: four programmes after 0–12 months,4 17 71 93 three programmes after 13–24 months47 72 84 and one programme after more than 24 months.69 Two programmes were evaluated at different time points during their implementation and after completion.77 94

Position of the evaluators

Since we found that the position of the evaluators regarding the programme was often not made explicit, we analysed the authors’ affiliations. We found that most CBP evaluations were reported by people involved in the design, implementation or funding.9 17 47 49 67–69 71–73 75–77 79–81 83–85 87 89 90 93–96 98 101 103 Some programmes were evaluated by people not involved in the design, implementation or funding.4 49 82 92 97 105

Outcomes of CPBs

The outcomes of CBPs reported in the included primary studies are summarised in table 11.

Table 11.

Reported outcomes

| Levels | Reported outcomes | Papers (n) | References |

| Individual level | Increased management or leadership knowledge | 3 | 17 86 94 |

| Increased management or leadership skills | 10 | 69 71 72 79 82 85 86 89 94 96 | |

| Work commitment | 1 | 89 | |

| Openness to being mentored and willingness to implement recommended changes | 1 | 98 | |

| Increased self-confidence to undertake management tasks | 1 | 17 | |

| Changes in the behaviour of supervisors who became more supportive | 1 | 91 | |

| Organisational level | Improvement in overall leadership and management practices, such as systems thinking, change management or performance management | 1 | 86 |

| Use of management tools to systematically set priorities, develop evidence-based work plans and allocate resources | 3 | 87 94 101 | |

| Improved district performance | 2 | 83 100 | |

| Improved financial management | 8 | 47 68 70 81 95 96 98 99 | |

| Improved human resource management, | 4 | 47 73 81 96 | |

| Improved health information management | 4 | 47 82 94 101 | |

| Improved supply chain and transportation management | 4 | 47 68 70 82 | |

| Improved supportive supervision | 2 | 72 82 | |

| Improved hospital management | 4 | 73 80 96 98 | |

| More regular and effective team meetings | 8 | 4 17 49 68 70 72 85 95 | |

| Improved team confidence to undertake management tasks | 4 | 4 68 79 95 | |

| Increased team and staff morale, motivation or commitment | 7 | 49 67 68 70 89 90 99 | |

| Improved work climate or environment | 2 | 17 99 | |

| Improved community engagement | 2 | 68 72 | |

| Improved collaboration between district health teams and local administrators | 1 | 67 | |

| Health outcomes | Reduction in maternal mortality among pregnant women referred to a district hospital | 1 | 67 |

| Markedly reduced incidence of measles cases in a district | 67 | ||

| Increased health service usage | 5 | 67 77 84 99 103 | |

| Increased immunisation coverage | 4 | 72 73 89 103 | |

| Increased antenatal care, skilled birth attendance | 4 | 72 73 89 103 | |

| Increased yaws and Buruli ulcer detection rate | 1 | 89 | |

| Increased health service coverage | 1 | 77 | |

| Improved (quality of) service delivery | 5 | 47 73 74 96 105 | |

| Improved malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea treatment for children | 1 | 87 | |

| Increased tuberculosis cure rate | 1 | 89 |

Four papers reported limited effects of CBPs. A comparison of the effects of two models of supervision (the matrix modified model and the centre for health and social studies model) showed no differences in the quality of care and the job satisfaction of nurses in South Africa.102 An assessment of facilitative supervision visits by the regional health team to nine district health management teams in northern Ghana showed that the performance of six out of nine districts (67%) was adjudged only fair.93 The realist evaluation of a leadership development programme in Ghana4 pointed out the lack of institutionalisation of leading and managing practices and systems thinking. The study by Chuy et al105 highlighted poor coherence and relevance of provincial-level support, which impeded developing leadership and governance capacity of district health management teams.

Sustainability

Four papers discussed the sustainability of the outcomes and processes of CBPs. Using the sustainability definition of Moore et al,106 we found that all four papers referred to one construct: the continued delivery of the programme. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, De Brouwere and Van Balen69 reported that doctors trained in the Kasongo project were still applying the skills they had learnt 7 years after the last training without saying more about the factors that explain this sustained effect. While acknowledging that it was early to make a final judgement on sustainability, Cleary et al92 reported promising signs in the Population Health Implementation and Training partnerships in Mozambique. They attributed this to the project’s flexibility, allowing for adaptations according to local realities and creating a sense of ownership among health system actors. In South Africa, Orgill et al49 were optimistic about the sustainability of the management CBP on the basis of the outputs observed over 18 months of implementation. The emergent nature of the intervention, which ensures ownership and commitment of team members, was cited as the main driver of this sustainability. In Kenya, Seims et al77 reported that two-thirds of the district-level and facility-level teams who received leadership development training achieved sustainability of results at least 6 months after completion of the programme. Underlying factors included ‘an improved work climate due to renovated staff quarters, training, or supervision’.

In 11 papers, the authors mentioned conditions for sustainability. These include collaboration, support, commitment and ownership by the Ministry of Health,67 71 81 98 101 collaboration, transfer of skills and institutionalisation of training to a local academic institution,17 71 73 alignment with and strengthening of existing local stakeholders and structures,75 76 97 alignments of management strengthening interventions with the district planning cycles and budget without providing additional resources.89

In three papers, the authors raised concerns about sustainability. Kokku72 reported that health trainers placed in district health management teams moved from a facilitator role to an implementor role in the Simanjiro Mother-child health capacity building project in Tanzania. Balinda et al86 reported the absence of a rollout plan for the governance, leadership and management training to other districts not supported by the Institutional Capacity Building project in Uganda. In Ghana, Kwamie et al4 reported the lack of institutionalisation of the leadership development programme, which they attributed to changes in leadership at regional, district and subdistrict levels.

Lessons learnt

Lessons learnt from CBPs reported in the included papers of this review are (1) the need for sufficient time for skill acquisition,98 continuous learning,79 89 and institutionalisation of leadership and management practices4; (2) the alternation of short workshops and on-the-ground follow-up visits, and the use of action learning approach which links training to real-world practice are essential to enable both theoretical knowledge and practical skills71 73 84 88 97; (3) a more reflective and context-sensitive approach in order to address complexity of health systems,4 enable flexibility73 and promote emergence and self-organisation49; (4) the collaboration with stakeholders such as local politicians and government leaders,67 provincial health authorities,79 other health partners,97 and northern and southern academic institutions71 is central for CBPs as it allows for support, scaling up and accountability; and (5) the importance of mitigating health workforce issues such as turn over by ensuring job satisfaction, job security career, appropriate trajectory and by developing strategies for efficient recruitment and training.101 94

Other themes

Our analysis identified other themes to consider in designing, implementing and evaluating CBPs. These are (1) the certification or accreditation (in the case of training) and (2) the success factors and underlying mechanisms.

Certification or accreditation

Four CBPs delivered either a university postgraduate or master diploma73 82 or a government certificate in health leadership and management.17 86 Certification or accreditation valued the CPBs and made them attractive to health managers as the resulting diploma offers opportunities for career development.17

Success factors and underlying mechanisms

Papers reported various success factors or mechanisms. These include (1) CBP methods, which empower DHMs and activate a can-do attitude (self-efficacy). These methods are team-based training,9 17 84 85 learning-by-doing approach,17 69 70 73 79 84 alternation of short workshops and on-the-ground follow-up visits,17 79 shift from administrative and control to a supporting model of supervision,100 placing trainers within the management teams for day-to-day support,72 96 reflective discussions for continuous learning,9 47 and combination of learning methods72; (2) supportive interactions between facilitators and DHMs,100 which enable mutual trust and enhance motivation and commitment of DHMs to actively participate in the CBP process and to engage with changes.70 89 99 Such interactions require facilitators to have good relational skills, which are central in the adult learning process107; (3) safe work environment, which enables teamwork and promotes distributed leadership9 78 79 89 96; (4) adaptability and flexibility of CBP processes make them more responsive as they consider the needs of DHMs and their context, which contribute to increased perceived relevance and sense of ownership by DHMs72 75 92; (5) support from and collaboration with the government authorities81 96; and (6) the role of the head of health district, who can act as a local champion by using sensemaking and sense giving micro-practices to trigger motivation and buy-in of CBP by the DHMs.49

From the lessons learnt and success factors of CBPs reported in the included papers of this review, we summarise the key features of an effective leadership and management CBP in box 2.

Box 2. Features of effective capacity building programmes.

A learning-by-doing approach.

An alternation of short workshops and on-the-ground follow-up visits.

A team-based approach.

The flexibility and adaptability of CBP processes.

Supportive interactions among facilitators and participants.

Collaboration with and involvement of different stakeholders.

A long-term perspective.

CBP, capacity building programme.

Discussion

This review highlights the growing interest in leadership and management in health systems, especially in the era of millennium development goals and sustainable development goals. Most papers point to weak leadership and management as a leading cause of poor health outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa and assume that better health outcomes cannot be achieved without proper leadership and management. This widespread assumption explains the increasing number of management and leadership CBPs in the last decade, as shown in this review and others.20 108 The decentralisation movement in sub-Saharan countries has been a solid argument for strengthening DHMs’ capacity to steer their health districts.

While most authors agree on the need to strengthen DHMs’ leadership and management capacities, there needs to be more consensus on how to do and evaluate this. Strikingly, we did not find one paper explicitly referencing a theory underlying the CBP reported on. Since programmes are ‘theories incarnate’,109 the lack of an explicit theory may jeopardise the understanding of how these programmes are supposed to work as well as their evaluation. Therefore, while designing a CBP, it is good to make explicit the theoretical assumptions and evidence explaining the pathway to the expected outcomes.62 Making the programme theory explicit allows for a better understanding of the programme functioning by different stakeholders and will facilitate its evaluation.

Despite the diversity of learning methods used in capacity building, there is a general tendency to combine methods to foster the acquisition of both theoretical knowledge and practical skills. Action learning is becoming the most widely used method. This result mirrors those of Geerts et al110 and Lyons et al111 who stressed the increase use of experiential approaches to leadership development. Action learning is based on Kolb’s experiential learning theory, which states that learning occurs through experience112 113 and emphasises real-life actions as the vehicle for learning.88 Action learning features advantages that can help strengthen DHMs’ leadership and management capacities. First, it goes beyond knowledge acquisition and enables skills development. It also enables participants to benefit from faculty or supervisor support after having attempted to apply their learning. It may be an interesting alternative to inadequate efficacy of leadership and management courses decried in some included papers of this review. Second, action learning stimulates a reflective attitude necessary for individual and collective learning.114 115 Third, action learning promotes teamwork and distributed leadership within district health management teams.115 It can thus help to minimise the effects of the hierarchical culture and gradually develop learning management teams that favour innovation, creativity and flexibility.114

The bulk of CBPs was delivered following a prescribed or normative approach, and the scarcity of the emergent approach was striking. This situation reflects the hierarchical culture still predominant in most sub-Saharan health systems8 and the dominance of international agencies funding or implementing ‘standardised’ CBPs. However, the normative approach has some weaknesses which may limit its effectiveness. First, it reinforces the ‘command-and-control’ system and can hinder learning, innovation and creativity.4 116 Second, it often assumes linear cause-and-effect relationships and tends to ignore the influence of context and the complex and adaptive nature of district health systems.49 116 117 Finally, it is often externally led and funded, and likely to be less sustainable as the risk of disruption at the end of the programme or funding is high.49 116 117 Since district health systems are complex and adaptative, some authors4 49 116 117 argue that CBPs need to be emergent. Moreover, Geerts et al110 warned that the prescriptive approach for all is not optimal, as if to say ‘one size does not fit all’. Unlike the prescribed approach, the emergent approach considers capacity as a result of interactions between system actors and elements. It is often internally led, bottom-up et likely more sustainable as it is ‘anchored in the daily routines’.4 116 The systematic review from Lyons et al111 suggest that leadership development programmes tailored to meet local needs may result in greater organisational impact than pre-packaged approaches to leadership development. A balance between the two approaches would benefit the DHMs who are at the ‘interface between strategic policy direction and operational service implementation’,118 that is, the best place of convergence between top-down and bottom-up processes in health systems.

This review highlighted the diversity of learning contents. This result is consistent with that of Lyons et al.111 Our analysis shows that most CBPs emphasised management rather than leadership. The same observation has been made by Johnson et al,108 who noted that some CBP labelled as leadership development focused virtually on management training. This seems to confirm Kotter’s statement, quoted by Kwamie,116 that ‘most organisations are over-managed and under-led’. It is also possible that the focus on management is because most DHMs are clinicians who need more basic management knowledge and skills since they have had little training in the area before. In any case, the content of CBPs for DHMs must consider the balance between management and leadership in complex and adaptive health systems, as advocated by Kwamie.116

This review found various evaluation designs and methods, reflecting the lack of ‘agreed approaches’ to CBP evaluation.20 108 110 111 Most evaluation designs from this review fell under three types of Øvretveit’s evaluation design classification: the descriptive, before and after, and comparative design.119 While these designs help to understand the process and measure the effectiveness of CBPs, such ‘black box’ designs provide limited insights into the conditions of success.120 We concur with DeCorby-Watson et al51 and Johnson et al,108 who call for strengthening CBP evaluations by basing them on explicit theories and evidence that describe how a CBP is supposed to lead to expected outcomes. Therefore, evaluators should go beyond the positivist paradigm and adopt a complex systems perspective that values context, interactions and emergence.

Most papers in this review pointed out a short timeframe as a limit for achieving changes in leadership or management behaviour, practices and health outcomes. Indeed, management and leadership CBPs are not one-off processes. They take time to bring about desired changes. Thus, it is crucial to consider a long-term perspective when designing and funding such programmes92 108 as time allows for progressive adoption and ownership by stakeholders, adaptation based on the context and learning.

The implications for practice and research suggested by this review are summarised in box 3.

Box 3. Implications for practice and research.

While designing a CBP, it is good to make explicit the (evidence-informed) theoretical assumptions that explain how different programme components, underlying assumptions, and contextual elements are supposed to lead to the expected outcomes. Such a theory is fundamental for programme implementation and evaluation success.

Inadequate training approaches have been identified as a cause of health managers’ weak leadership and management capacity. This review highlights the importance of a mix of didactic and practical approaches to acquiring knowledge and skills, self-efficacy and learning through real-life action.

This review suggests balancing prescribed and emergent approaches to CBPs. When relying on standards, guidelines or competency frameworks implemented through a hierarchical structure, it is crucial to leave room for innovation, adaptation and emerging local initiatives. Such ‘homegrown’ initiatives are more likely to boost health managers’ ownership, motivation and commitment, and ultimately the sustainability of the intervention.

Although conceptually different, leadership and management are closely linked in practice. Indeed, while health organisations need strong managers to plan, organise and coordinate activities, these managers need also to be good leaders who can anticipate, inspire, motivate and bring about changes. Therefore, the content of CBPs for DHMs must consider the balance between management and leadership.

There is still a need for strengthening the evaluation of management and leadership CBP evaluations in sub-Saharan Africa. Evaluators or researchers should go beyond the positivist paradigm and adopt a complex systems perspective that values context, interactions and emergence. From such a perspective, theory-driven evaluations are a good fit.

Management and leadership CBPs are not one-off processes. They take time to bring about desired changes. Time is necessary for successful implementation as it allows for progressive adoption and ownership by stakeholders, an adaptation based on the context and learning. It is thus crucial to consider a long-term perspective when designing and funding CBPs.

CBPs, capacity building programmes; DHMs, district health managers.

Limitations

This review has some limitations. First, we did not appraise the quality of the included papers as scoping reviews do not require a quality appraisal.52 Yet, we noted that most of the included articles that presented an evaluation had some methodological issues that call for caution when interpreting results. Second, we may have missed other relevant literature not available publicly or published in languages other than English or French. Third, the fact that we have not included any papers related to online CBPs is a limitation of this review, particularly in the digital and COVID-19 era. Finally, we have made some trade-offs between comprehensiveness and feasibility, as it is often the case in scoping reviews.31

Conclusion

In the era of sustainable development goals, leadership and management capacities are crucial at the health district level. This review showed a paucity of theory-driven CBPs, a diversity of learning approaches, methods and content, and no agreed methods to CBP evaluation of DHMs in sub-Saharan Africa. These results call for more consistent theories to guide the design, implementation and evaluation of CBPs for DHMs in sub-Saharan Africa. CBPs need a balance between prescribed and emergent approaches, an optimal mix of didactic and practical learning methods, a balance between management and leadership content, and robust evaluations. Considering the complex and adaptative nature of health districts and adopting a long-term perspective will likely enable conditions and mechanisms to sustain management and leadership CBPs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the reviewers for their insightful comments and feedback during the peer-review process.

Footnotes

Twitter: @BosongoS, @drbelrhiti

Contributors: SB, ZB, BM, FC and BC conceptualised the study. SB conducted the database searching. SB, JE and CK screened abstracts and full texts, extracted data and synthesised data. SB drafted the initial manuscript. SB, ZB, BM, FC and BC contributed to manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. SB is the responsible or guarantor of overall content of this manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Directorate-General Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid, Belgium in collaboration with the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp as a part of the doctoral programme of SB, grant number 911063/70/130. The funder had no role in the whole process of the review from the design to the publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Évaluation des progrès réalisés en afrique pour atteindre LES objectifs du millénaire pour le développement. In: Rapport OMD 2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridge LJ, Klar RT, Stimpfel AW, et al. “The meaning of "capacity building" for the nurse workforce in sub-Saharan Africa: an integrative review”. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;86:151–61. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alliance for Health P, Systems R . Strengthening health systems: the role and promise of policy and systems research. Geneva, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwamie A, van Dijk H, Agyepong IA. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: realist evaluation of the leadership development programme for district manager decision-making in Ghana. Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:29. 10.1186/1478-4505-12-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egger D, Ollier E. Managing the health millennium development goals - The challenge of health management strengthening: lessons from three countries. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doherty T, Tran N, Sanders D, et al. Role of district health management teams in child health strategies. BMJ 2018;362:k2823. 10.1136/bmj.k2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO . Building resilient sub-national health systems – strengthening leadership and management capacity of district health management teams. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilson L, Agyepong IA. Strengthening health system leadership for better governance: what does it take? Health Policy Plan 2018;33:ii1–4. 10.1093/heapol/czy052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleary S, Toit A du, Scott V, et al. Enabling relational leadership in primary Healthcare settings: lessons from the DIALHS collaboration. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:ii65–74. 10.1093/heapol/czx135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonenberger M, Aikins M, Akweongo P, et al. Factors influencing the work efficiency of district health managers in low-resource settings: a qualitative study in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:12. 10.1186/s12913-016-1271-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aroni A. Health management capacity building. An integral component of health systems’ improvement. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider H, George A, Mukinda F, et al. District governance and improved maternal, neonatal and child health in South Africa: pathways of change. Health Syst Reform 2020;6:e1669943. 10.1080/23288604.2019.1669943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prashanth NS, Marchal B, Devadasan N, et al. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: a realist evaluation of a capacity building programme for district managers in Tumkur, India. Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:42. 10.1186/1478-4505-12-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heerdegen ACS, Aikins M, Amon S, et al. Managerial capacity among district health managers and its association with district performance: a comparative descriptive study of six districts in the eastern region of Ghana. PLoS One 2020;15. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daire J, Gilson L, Cleary S. Developing leadership and management competencies in low and middle-income country health systems: a review of the literature working paper 4. Res Respon Health Sys 2014:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Organisation mondiale de la s . Renforcement des systèmes de santé: amélioration de la prestation de services de santé au niveau du district, et de l'appropriation et de la participation communautaires. Rapport Du Directeur Régional 2010:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mutale W, Vardoy-Mutale A-T, Kachemba A, et al. Leadership and management training as a catalyst to health system strengthening in low-income settings: evidence from implementation of the Zambia management and leadership course for district health managers in Zambia. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174536. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United Nations General A . Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tetui M, Hurtig A-K, Ekirpa-Kiracho E, et al. Building a competent health manager at district level: a grounded theory study from Eastern Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:665. 10.1186/s12913-016-1918-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finn M, Gilmore B, Sheaf G, et al. What do we mean by individual capacity strengthening for primary health care in Low- and middle-income countries? A systematic Scoping review to improve conceptual clarity. Hum Resour Health 2021;19:5. 10.1186/s12960-020-00547-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchal B, Kegels G. Which role for Medicus mundi Internationalis in human resources development? Current critical issues in human resources for health. 2003.

- 22.Morgan P. The design and use of capacity development indicators. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whittle S, Colgan A, Rafferty M. Capacity building: what the literature tells us. report no: 978-0-9926269-0-7. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prashanth NS, Marchal B, Kegels G, et al. Evaluation of capacity-building program of district health managers in India: a contextualized theoretical framework. Front Public Health 2014;2:89. 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petticrew M. “When are complex interventions 'complex'? When are simple interventions ’simple” Eur J Public Health 2011;21:397–8. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Health Foundation . Evidence scan: complex adaptive systems. The Health Foundation, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sturmberg JP, O’Halloran DM, Martin CM. Understanding health system reform - a complex adaptive systems perspective. J Eval Clin Pract 2012;18:202–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glouberman S, Zimmerman B. Complicated and complex systems: what would successful reform of Medicare look like? Comission on the future of health care in Canada. 2002.

- 30.De D, Adam T. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belrhiti Z, Nebot Giralt A, Marchal B. Complex leadership in Healthcare: a scoping review. Int J Health Policy Manag 2018;7:1073–84. 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prashanth NS, Marchal B, Hoeree T, et al. How does capacity building of health managers work? A realist evaluation study protocol. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000882. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lusthaus C, M-h A, Perstinger M. Capacity development: definitions, issues and implications for planning, monitoring and evaluation. Universalia Occasional Paper 1999:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crisp BR. Four approaches to capacity building in health: consequences for measurement and accountability. Health Promot Int 2000;15:99–107. 10.1093/heapro/15.2.99 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg J, Bryant M. Country ownership and capacity building: the next buzzwords in health systems strengthening or a truly new approach to development. BMC Public Health 2012;12:531. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawe P, Noort M, King L, et al. Multiplying health gains: the critical role of capacity-building within health promotion programs. Health Policy 1997;39:29–42. 10.1016/s0168-8510(96)00847-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaFond AK, Brown L, Macintyre K. Mapping capacity in the health sector: a conceptual framework. Int J Health Plann Manage 2002;17:3–22. 10.1002/hpm.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Land T. Implementing institutional and capacity development: conceptual and operational issues. 2000.

- 39.Potter C, Brough R. Systemic capacity building: a hierarchy of needs. Health Policy Plan 2004;19:336–45. 10.1093/heapol/czh038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milèn A. An overview of existing knowledge and good practice? an overview of existing knowledge and good practice. 2001.

- 41.Matachi A. Capacity building framework. UNESCO-international institute for capacity building in Africa. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gholipour K, Tabrizi JS, Farahbakhsh M, et al. Evaluation of the district health management fellowship training programme: a case study in Iran. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020603. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tabrizi JS, Gholipour K, Farahbakhsh M, et al. Developing management capacity building package to district health manager in northwest of Iran: a sequential mixed method study. J Pak Med Assoc 2016;66:1385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Omar M, Gerein N, Tarin E, et al. Training evaluation: a case study of training Iranian health managers. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:1–14. 10.1186/1478-4491-7-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El-Sayed H, Martines J, Rakha M, et al. The effectiveness of the WHO training course on complementary feeding counseling in a primary care setting, Ismailia, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc 2014;89:1–8. 10.1097/01.EPX.0000443990.46047.a6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.El Nouman A, El Derwi D, Abdel HR, et al. Female youth health promotion model in primary health care: a community-based study in rural upper Egypt. Eastern Mediterranean health Journal = la revue de sante de la MEDITERRANEE orientale = al-majallah al-sihhiyah li-sharq al-mutawassit. 2009;15:1513–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chelagat T, Rice J, Onyango J, et al. An assessment of impact of leadership training on health system performance in selected counties in Kenya. Front Public Health 2020;8:550796. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.550796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heerdegen ACS, Gerold J, Amon S, et al. How does district health management emerge within a complex health system? Insights for capacity strengthening in Ghana. Front Public Health 2020;8:270. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orgill M, Marchal B, Shung-King M, et al. Bottom-up innovation for health management capacity development: a qualitative case study in a South African health district. BMC Public Health 2021;21:587. 10.1186/s12889-021-10546-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown L, Lafond A, Macintyre K. Measuring capacity building. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeCorby-Watson K, Mensah G, Bergeron K, et al. Effectiveness of capacity building interventions relevant to public health practice: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018;18:684. 10.1186/s12889-018-5591-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods and reporting scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition how to cite Tspace items. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:3–13. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with arksey and o'malley's framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:48. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, et al. Best fit” framework synthesis: refining the method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:37. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K. “A worked example of "best fit" framework synthesis: A systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents”. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:29. 10.1186/1471-2288-11-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic Scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belrhiti Z, Booth A, Marchal B, et al. To what extent do site-based training, mentoring, and operational research improve district health system management and leadership in Low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2016;5:70. 10.1186/s13643-016-0239-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.The World Bank . World Bank country and lending groups. n.d. Available: https://datahelpdeskworldbankorg/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups2021

- 61.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile App for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]