Abstract

Cadmium (Cd) is an important environmental pollutant that causes liver damage and induces nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD is a fat accumulation disease and has significant effects on the body. Melatonin (Mel) is an endogenous protective molecule with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiobesity, and antiaging effects. However, whether Mel can alleviate Cd-induced NAFLD and its mechanism remains unclear. First, in vivo, we found that Mel maintained mitochondrial structure and function, inhibited oxidative stress, and reduced Cd-induced liver injury. In addition, Mel alleviated lipid accumulation in the liver induced by Cd. In this process, Mel inhibits fatty acid production and promotes fatty acid oxidation. Interestingly, Mel regulated PPAR-α expression and alleviated Cd-induced autophagy blockade. In vitro model, the oil Red O staining, and WB results showed that Mel alleviated Cd-induced lipid accumulation. In addition, RAPA was used to activate autophagy to alleviate Cd-induced lipid accumulation, and TG was used to block autophagy flux to aggravate Cd-induced autophagy accumulation. After knocking down PPAR-α, the autophagosome fusion with lysosomes, and autophagic flux was inhibited and increased Cd-induced lipid accumulation. Mel alleviates mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress, and attenuates Cd-induced NAFLD by restoring the expression of PPAR-α and restoring autophagy flux.

Key words: melatonin, cadmium, PPAR-α, autophagic flow, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Cadmium (Cd) is a nonessential element in the human body. In nature, Cd frequently coexists with zinc and lead and has good metal properties. Cd has been widely used in the chemical, electronics, and nuclear industries. A considerable amount of Cd is discharged into the environment through wastewater and waste residue, resulting in pollution. After Cd enters aquatic systems, it can spread with water sources and cause persistent pollution. Wood ducks (Aix sponsa) reside in river systems with high Cd and Pb contents in sediments and have increased exposure to these metals (Blus et al., 1991). At present, a major issue on a worldwide scale is Cd pollution. The epidemiological investigation results showed that serum Cd concentration was positively correlated with the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (Spaur et al., 2022). NAFLD is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in more than 25% of the world's population. NAFLD is a progressive disease that eventually leads to o nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, and cirrhosis. In the development of hepatic steatosis, the oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage contribute to the development of the disease (Videla and Valenzuela, 2022). Cd exposure can lead to hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction and fatty acid oxidation defects, which are linked to the development of NAFLD (Gyamfi et al., 2012).

Autophagy is the process of engulfing one's own cytoplasmic protein or organelle and enveloping it into a follicle and fusing with lysosomes to form an autophagy-lysosome, degrading its encapsulated contents (Mizushima, 2007; Lian et al., 2023a). It is mainly divided into macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (Xu et al., 2021). Lipid droplets as a cell content can also be degraded by autophagy. Singh et al. reported that autophagy is involved in liver lipid metabolism, and after inhibiting autophagy, increases lipid accumulation within liver cells (Singh et al., 2009). Therefore, autophagy can be used as an important target to alleviate the development of NAFLD. Previous studies have shown, the continuous exposure to Cd, that the autophagic flux is disrupted (the fusion or degradation phase is blocked), resulting in autophagosome accumulation that cannot be degraded and recycled (Zou et al., 2020b; Gong et al., 2022). Glycyrrhetinic acid can alleviate NAFLD by modulating macrophage autophagy flux (Fan et al., 2022). These studies have initially explored the role of targeting autophagy in alleviation of NAFLD.

An indole melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is mainly produced by the pineal gland, has a key role in maintaining the stability of the intracellular environment and regulating circadian rhythms (Rios et al., 2010), and effective in metabolic syndrome (Robeva et al., 2008). Recently, Mel reversed the deleterious effects of dietary fructose in animal models regulating metabolic pathways, such as lipogenesis and lipolysis, fatty acid oxidation (Stacchiotti et al., 2019). Mel is lipophilic and can freely pass through all biofilms, mainly accumulate in mitochondria, and maintain the REDOX balance of cells by maintaining the stability of the mitochondrial internal environment (Manchester et al., 2015). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) is highly expressed in the liver. PPAR-α controls the transcription of several genes encoding enzymes involved in fatty acid uptake, binding and activation, mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, and plasma triglyceride (TG) hydrolysis, and its promoter region contains PPRE (Schoonjans et al., 1996; Lian et al., 2023b). Loss of PPAR-α and mitochondrial damage is the main mechanisms of oxidative stress induced by multiple metals (Barrera et al., 2018). When PPAR-α was deleted during high feed (HF) diet feeding, TG accumulation was more pronounced in the liver of male mice, suggesting that PPAR-α prevents lipid overload (Patsouris et al., 2006). In addition, HF diet and hepatic PPAR-α deficiency have been reported to independently increase TG levels. PPAR-α has also been shown to regulate autophagy against fungal infections and promote ciliogenesis. Activity of PPAR-α reverses the normal inhibition of autophagy in the fed state, induces autophagic lipid degradation, and mediates innate host defense (Regnier et al., 2020). However, the detailed molecular mechanisms are poorly understood. Therefore, in this study, in vivo and in vitro models were established using duck and AML12 cells to further explore the mechanism of Mel-targeted lipid production and autophagy alleviating Cd-induced NAFLD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Treatment

Every procedure and protocol involving animals were permitted by the Yangzhou University Comparative Medical Center (Jiangsu Province, China). Feed for 1 wk after domestication, 32 healthy male Shaoxing duck 14-day-old Shaoxing ducks (Aix sponsa) were randomly divided into 4 groups and fed a diet (kg): Control group (0 mg/L Cd + 0 mg/L Mel), Cd group (50 mg/L Cd), Mel group (20 mg/kg Mel), and Mel + Cd group (20 mg/kg Mel + 50 mg/L Cd). The selection of Cd concentration in this article is consistent with that reported previously, and Cd can accumulate in the liver (Zou et al., 2020a). All ducks were raised separately in cages in the same environment, and food and water were available. The trial period was 12 wk. At the end of 12th wk, all ducks were given a 12 h fast before being slaughter in accordance with their body weight using an intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital solution (50 mg/kg). After that, the liver tissue was removed, weighed, and then immersed in 10% neutral formalin or 2.5% glutaraldehyde for subsequent experiments. The study was based on the Guide to Moral Control and Supervision in Animal Conservation and Use.

Reagents

The following antibodies and chemicals were used: Cadmium chloride (CdCl2), antimicrotubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 betas (LC3B), and SQSTM1/P62 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Melatonin (Shanghai, China). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-COX IV, anti-ACC, anti-FAS, anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Anti-CPT1 and anti-PPAR-α (Proteintech, Wuhan, China). Dihydroethidium (DHE), Oil Red O Staining Kit, and Hoechst 33258 (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Micromitochondrial respiratory chain complex I–V activity assay kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay kit, glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX) assay kit, superoxide dismutase (SOD), triglyceride assay kit, and total cholesterol assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing. China), and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) specific for PPAR-α (RiboBio Corporation, Guangzhou, China).

Cell Culture and Processing

The alpha mouse liver 12 (AML12) cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CRL-2254, VA). The cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 1.0% ITS-A, 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in the presence of 95% air and 5% CO2. Next, cadmium chloride was dissolved in ultrapure water. When processing the cells, the cadmium chloride was dissolved in a serum-free medium to prepare the corresponding treatment concentrations.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The cells and the liver tissue were washed twice with PBS, fixed in fresh 2.5% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 2 h, and finally transferred to 4°C for 12 h. The samples were fixed in osmic acid, dehydrated, entrapped, subjected to ultrathin sectioning, negatively stained, and observed under a transmission electron microscope.

Superoxide Anion Detection

For the liver, the removed tissue was pretreated, embedded with optimum cutting material (OTC) embedding agent, and made into frozen sections. The slices were treated with DHE dye for 20 min and rinsed with running water. The tissue section slides were covered with a coverslip and observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Detection of Oxidative Stress-Related Indexes

The cellular activity of MDA, SOD, and GSH-Px was measured using specific commercial kits from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China) by manufacturer's instructions.

Detection of Micromitochondrial Respiratory Chain Complex I–V Activity

Appropriate amounts of tissue were taken to measure the enzymatic activity of Micro Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Complex I–V Activity using specific commercial kits (Solarbio, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Oil Red O and BODIPY Staining

Oil Red O (ORO) is a fat-soluble azo dye that is a strong fat-soluble reagent and fat stain that can specifically stain neutral lipids such as triglycerides in cells or tissues. After the cells were fixed, stained, and washed, they were observed and photographed under an inverted fluorescence microscope. BODIPY is a lipophilic fluorescent probe that targets polar lipids and can be used to label cellular neutral lipid content, specifically targeting lipid droplets in living and fixed cells. After that the cells were treated with Cd, they were washed twice with PBS and subsequently incubated with BODIPY dye at 37°C for 20 min. The samples were washed 3 times with PBS before they were observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Western Blotting Analysis

For liver tissue samples: weigh a certain amount of liver tissue and add lysate according to the ratio of 1:9 to prepare tissue homogenate, followed by ultrasound, centrifugation of 12,000 × g for 15 min, and take the supernatant for use. For cell samples: cells grown on dishes were collected using a cell scraper, centrifuged, lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer at 4°C for 30 min, and treated with ultrasound twice for 5 s each time. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was retained. The protein concentration was measured by Bradford protein assay (PC0010, Solarbio). The proteins were separated with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, MA). After incubating with primary (ACC, FAS, CPT1, PPAR-α, etc.) and secondary antibodies, the band densities were measured with Image Laboratory software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Statistical Analysis

The data from at least 3 independent experiments were statistically analyzed and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used to analyze the data with a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Scheffe's SF test). P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate significant differences.

RESULTS

Melatonin Alleviates Cadmium-Induced Liver Injury in Ducks

Light microscopy showed that the liver tissue was intact, the structure of the liver sinusoid was clear, and the chromatin in the nucleus was uniform in the control group. However, in the Cd treatment group, the liver tissue was disordered, the liver sinusoid was narrow, and the hepatocytes were significantly vacuolated (Figure 1A). The Cd + Mel group alleviated the pathological changes in liver. Liver weight and liver-specific gravity were significantly increased by Cd, compared to those by Mel + Cd treatment (Figure 1B and C).AST, ALT, and ALP are important indicators of liver function injury. The contents of ALT and ALP in serum were significantly increased in the Cd group compared to control group, but they were significantly decreased in the Mel + Cd groups compared to Cd group (Figure 1D–F). AST changes were not obvious.

Figure 1.

Melatonin alleviates cadmium-induced liver injury in ducks. After treatment with Mel (20 mg/kg) and/or Cd (50 mg/L) for 12 wk. The liver histopathology observed using HE staining (A). Scale bar = 100 μm. Liver weights (B) and liver coefficient (C) in duck treated with Mel (20 mg/kg) and/or Cd (50 mg/L). Liver function was assessed by serum levels of ALT (D), AST (E), and ALP (F). Results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Compared with the control group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Compared with the Cd group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01.

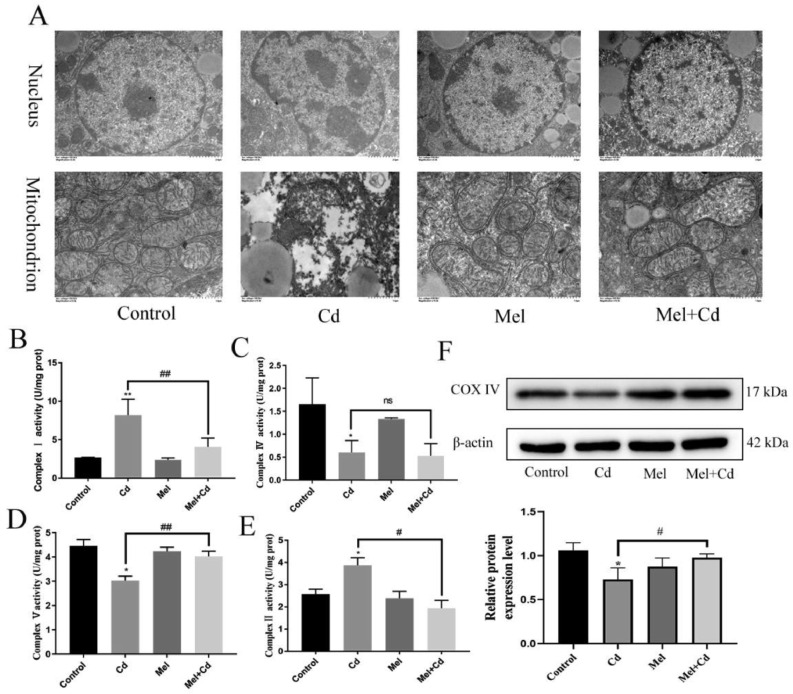

Melatonin Alleviates Mitochondrial Damage in Duck Liver Caused

The effect of Cd on the ultrastructure of duck liver and the protective effect of Mel were observed by transmission electron microscopy. The ultrastructure of liver in the control group showed that, the nuclear morphology of hepatocytes was normal, the uniformed nuclear chromatin, and the mitochondrial structure was clear. In the Cd group, hepatocytes showed nuclei shrank, chromatin concentrated, and mitochondria blurred. Compared with the Cd group, the Mel + Cd group mitigated changes in the ultrastructure of the liver (Figure 2A). WB results also showed that Cd significantly decreased the expression of COX IV, the Cd + Mel group increased the expression of COX IV (Figure 2F). In this study, the enzyme activities of the mitochondrial respiratory chain were further examined. The results showed that Cd increased the enzyme activities of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes I and II, and decreased the enzyme activities of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes IV and V, while Mel alleviated these changes (Figure 2B–E). However, Cd and Mel did not have a significant effect on mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes III (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Melatonin alleviates mitochondrial damage in duck liver. After treatment with Mel (20 mg/kg) and/or Cd (50 mg/L) for 12 wk, the changes in cell ultrastructure was analyzed under a transmission electron microscope and representative images are shown. (A). Scale bar in nuclei = 2 μm; scale bar in mitochondria = 1 μm. The enzyme activities of the mitochondrial respiratory chain I (B ), II (E), IV (C), and V (D) were examined. The levels of COX IV were measured using Western blotting (F). Results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Compared with the control group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Compared with the Cd group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01.

Melatonin Alleviates Oxidative Stress Induced by Cadmium in Duck Liver

DHE staining was used to detect superoxide anion in the liver. The results showed that Cd significantly increased the amount of superoxide anion in the liver, However, Mel + Cd significantly decreased the amount of superoxide anion in the liver (Figure 3A). In this study, MDA, GSH-PX, and SOD were further detected, and the results showed that compared with the control group, Cd significantly increased MDA content and reduced the enzyme activity of GSH-PX and SOD. Mel alleviates these changes (Figure 3B–D). Furthermore, the antioxidant enzymes activity of Fe2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+ were detected. Compared with the control group, the contents of Fe2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+ were significantly reduced in Cd group. However, the contents of Fe2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+ were increased in Mel + Cd groups (Figure 3E–G).

Figure 3.

Melatonin alleviates oxidative stress induced by cadmium in duck liver. Ducks were treated with Mel (20 mg/kg) and/or Cd (50 mg/L) for 12 wk, the production of superoxide anions in the liver was measured by DHE staining and representative images are shown. (A). Scale bar =100 μm. The contents of MDA (B), SOD (D) and GSH-PX (C) were detected. The contents of Fe2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+ related to the activity of antioxidant enzymes were detected (E–G). Results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Compared with the control group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Compared with the Cd group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01.

Melatonin Alleviates Lipid Accumulation

Transmission electron microscopy was used to observe the intracellular lipid droplets, and the results were shown in Figure 4A. Compared with the control group, the number of intracellular lipid droplets was significantly increased in the Cd group, while the number of intracellular lipid droplets was significantly decreased in the Mel + Cd groups. We further detected the contents of TG and T-CHO in the liver, the Cd group increased the contents of TG and T-CHO in tissue, while the Mel + Cd decreased the contents of TG and T-CHO (Figure 4B and C). Compared with the control group, the Cd group increased the expression of ACC and FAS, and decreased the expression of CPTI and PPAR-α, while the Mel + Cd groups alleviated this trend (Figure 4D). ORO is a fat-soluble stain that can specifically color neutral fats such as TG in tissues. Results showed, Cd significantly increased the content of TG and other neutral fats in AML12 cells. However, Mel + Cd group decreased the content of TG in AML12 cells (Figure 4E). In comparison to the control group, the Cd group increased ACC and FAS expression, and decreased the expression of CPTI and PPAR-α. However, this trend was reversed by the Mel + Cd groups (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Melatonin alleviates lipid accumulation in liver. Ducks were treated with Mel (20 mg/kg) and/or Cd (50 mg/L) for 12 wk. Transmission electron microscopy was used to observe intracellular lipid droplets (A). Scale bar =5 μm. The contents of TG (B) and T-CHO (C) in the liver. The levels of PPAR-α, ACC, CPT1, and FAS were measured using Western blotting (F–G). Results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Compared with the control group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Compared with the Cd group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01. Cells were treated with 5 µM Cd and 20 µM Mel, alone or in combination, for 12 h. Oil red O (E) was used to observe intracellular lipid droplets. The levels of PPAR-α, ACC, CPT1, and FAS were measured using Western blotting (F). Results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Compared with the control group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Compared with the Cd group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01.

Melatonin Ameliorates Blockade of Autophagic Flux

Transmission electron microscopy and WB were performed to detect the effect of Mel on Cd-induced liver autophagy. In tissue samples, Cd significantly increased the number of autophagosomes and the expression of LC3 and P62 (Figure 5A and B), and similar findings were observed in AML12 cells. Compared with the Cd group, the number of autophagosomes and the expression of LC3 and P62 were significantly decreased in the Mel + Cd groups (Figure 5C and D).

Figure 5.

Melatonin ameliorates blockade of autophagic flux in the liver. The changes in autophagosomes in the tissue samples (A) and AML12 cells (C) were viewed and photographed under a transmission electron microscope. Scale bar = 2.0 μm. In the tissue samples (B) and AML12 cells (D), the levels of LC3 and P62 were measured using Western blotting. Results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Compared with the control group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Compared with the Cd group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01.

PPAR-α Alleviates Cadmium-Induced NAFLD by Alleviating Autophagic Flow Block

To further examine the role of autophagy in lipid accumulation, RAPA and Cd were cotreated to alleviate the accumulation of lipids in AML12 cells. Thapsigargin (TG) plays a role in inhibiting autophagy by blocking the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes. In this study, TG and Cd were cotreated, and the results showed that TG aggravated Cd-induced accumulation of AML12 lipid (Figure 6A). To verify the role of PPAR-α in Cd-induced lipid accumulation, as shown in Figure 6B and C, compared with the Cd group, the siRNA PPAR-α+ Cd group significantly increased the expression of LC3 and P62, also significantly increased the number of lipid droplets in AML12 cells.

Figure 6.

PPAR-α alleviates cadmium-induced NAFLD by alleviating autophagic flow block. Oil red O (A) and was used to observe intracellular lipid droplets. Scale bar = 200 μm. Based on treatment with PPAR-α siRNA or NC siRNA for 24 h, AML12 cells were treated with or without Cd for 12 h. Levels of LC3 and P62 were measured using Western blotting (B). BODIPY(C) was used to observe intracellular lipid droplets. Results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Compared with the control group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Compared with the Cd group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Cd burden in the environment has continuously increased because to the rapid development of industrialization (Pinot et al., 2000). Recent studies have shown that high concentrations of Cd have been detected in poultry living in mining areas (Rafati Rahimzadeh et al., 2017), as well as in wood ducks and humans living in polluted areas for a long time. Is associated with the development of chronic diseases (Orisakwe et al., 2017). The liver is the target organ of Cd toxicity. Cd exposure induces inflammation and apoptosis in animal models of acute liver injury (Hyder et al., 2013). Furthermore, environmental Cd exposure is associated with necrotizing inflammation, NAFLD, and NASH of the liver (Sen et al., 2022).

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is an endogenous chemical hormone that is mainly synthesized in the pineal gland and has a circadian rhythm. Mel acts in a variety of ways and has a wide range of physiological and pathophysiological functions, such as regulating circadian rhythms (Stein et al., 2020), immune regulation (Xia et al., 2019), antioxidants (Xia et al., 2020), and preventing tumor metastasis (Liu et al., 2021). Typically, Mel acts by binding to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) Mel receptors 1 and 2 (MEL1 and MEL2), which are expressed in almost all nucleated cells (Posa et al., 2020). GPCR plays an important pathophysiological role in the occurrence and progression of diseases through interactions with downstream signal transduction molecules. Mel has been reported to prevent cardiovascular disease-mediated myocardial injury, including ischemia/reperfusion (Zhang et al., 2019), atherosclerosis (Zhao et al., 2021), hypertension (MacLean, 2020), thoracic aortic aneurysms, and dissection (Xia et al., 2020). Nevertheless, Mel in Cd duck liver injury and its role in the development of NAFLD is not yet clear, in this study, we found the Mel could alleviate the liver damage caused by Cd. Due to Mel can enter mitochondria and interact with mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes to protect mitochondria from damage caused by external stimuli (Atayik and Cakatay, 2022). We infer that Mel relieves Cd-induced liver damage closely with its mitochondrial protective function, and our results further confirm this, finding that Mel relieves Cd-induced mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress.

NAFLD is an emerging disease that is becoming more common throughout the world, which is associated with obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, dyslipidemia, etc. (Younossi et al., 2018; Stefan et al., 2019). Mel protects rats from NASH induced by methionine and choline deficiency diet, and attenuates NAFLD in leptin-deficient mice and hypercholesterolemic ApoE mice by enhancing SIRT1 in hepatocytes (Tahan et al., 2009). In vivo and vitro studies, we found that cotreatment with Cd and Mel restores autophagic flux and reduced lipid accumulation in the liver. We speculate that the recovery of autophagy flux may be an important pathway for Mel to alleviate Cd-induced lipid accumulation. Autophagy is a conserved self-eating process, which is very important for the cellular homeostasis of lipid metabolism under stress conditions (Li et al., 2019). It is known that autophagy can induce the hydrolysis of TG to fatty acids and attenuate the progression of NAFLD (Stacchiotti et al., 2019). When excess TG accumulate in cells, the autophagy process begins and TG become encapsulated and subsequently fuse with lysosomes (Singh and Cuervo, 2012). Lipids are broken down into fatty acids within lysosomes and then transported to mitochondria for β-oxidation and production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Loomba et al., 2021). Furthermore, we found that activating autophagy showed similar results to Mel, reducing lipid accumulation in the liver, while disrupting autophagy flow exacerbated cadmium-induced lipid accumulation in the liver. More interestingly, we found that Cd significantly decreased the expression of PPAR-α, while Mel alleviated the loss of PPAR-α. PPAR-α is a PPAR isoform that regulates the expression of genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism and inflammatory processes by binding to PPAR response elements in gene precursor regions (Keller et al., 1993; Kersten, 2014). Thus, PPAR-α is a key regulator of energy metabolism, and mitochondrial and peroxide isoenzyme function (Vamecq and Latruffe, 1999). Activation of PPAR-α can attenuate or inhibit angiogenesis, lipotoxicity, and oxidative stress, a feature that is achieved by (i)endogenous ligands (palmitic acid (C16:0, PA), stearic acid (C18:0,SA), oleic acid (C18:1 n-9, OA), LA, arachidonic acid (C20:4, AA), and eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5, EPA) (Echeverria et al., 2016). In this manuscript, whether cadmium's inhibition of PPAR-α is related to fatty acids is not clear, which will also be the direction of our further exploration.TG accumulation was more pronounced in the liver of male mice with PPAR-α deletion after HF diet feeding, indicating that PPAR-α can prevent lipid overload. In addition, it has also been reported that HF diet and hepatic PPAR-α deficiency independently increase hepatic TG levels (Lee et al., 2014). PPAR-α can also regulate the autophagy development, and it has been shown that PPAR-α regulate the expression of genes involved in the biogenesis and function of autophagosomes and lysosomes (van Raalte et al., 2004). In addition, PPAR-α activation leads to the upregulation of TFEB and nuclear translocation against mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Whether PPAR-α can regulate autophagy flux to mitigate NAFLD is unclear. siRNA PPAR-α was used to further reduce PPAR-α expression, and we found that reducing PPAR-α expression increased P62 expression and blocked autophagy flow. It also further increases lipid accumulation. These results suggest that PPAR-α can restore autophagic flux and inhibit lipid accumulation, but the mechanism of how PPAR-α restores autophagic flux needs to be further studied.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we revealed the detailed mechanism by which Mel targets autophagy to relieve Cd-induced NAFLD, providing a new avenue for the study of targeting autophagy strategies to protect against heavy metal poisoning. Our results proved that Mel has multiple targets in the process of alleviating Cd-induced NAFLD by targeting autophagy, involving the activation of autophagy and the alleviation of autophagy blockade. In addition, Mel restored the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes by restoring PPAR-α expression levels, thereby alleviating Cd-induced autophagy blockade in hepatocytes. Consequently, we believe that PPAR-α is an important target through which Mel regulates autophagy to alleviate the hepatocyte lipid accumulation of Cd.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 31702305, 31872533, 31802260, and 31772808].

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Every procedure and protocol involving animals were permitted by the Yangzhou University Comparative Medical Center (Jiangsu Province, China). The study was based on the Guide to moral Control and Supervision in Animal Conservation and use.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions: Jian Sun, Yusheng Bian, and Hui Zou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software. Tao Wang: Data curation, Writing - Original draft preparation. Yonggang Ma, Waseem Ali, Yan Yuan, Jianhong Gu: Visualization, Investigation. Jianchun Bian and Zongping Liu: Writing - Reviewing and Editing.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2023.102835.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- Atayik M.C., Cakatay U. Melatonin-related signaling pathways and their regulatory effects in aging organisms. Biogerontology. 2022;23:529–539. doi: 10.1007/s10522-022-09981-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera C., Valenzuela R., Rincon M.A., Espinosa A., Echeverria F., Romero N., Gonzalez-Manan D., Videla L.A. Molecular mechanisms related to the hepatoprotective effects of antioxidant-rich extra virgin olive oil supplementation in rats subjected to short-term iron administration. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018;126:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blus L.J., Henny C.J., Hoffman D.J., Grove R.A. Lead toxicosis in tundra swans near a mining and smelting complex in northern Idaho. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1991;21:549–555. doi: 10.1007/BF01183877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria F., Ortiz M., Valenzuela R., Videla L.A. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids regulation of PPARs, signaling: relationship to tissue development and aging. Prostagland. Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2016;114:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Dong W., Wang Y., Zhu S., Chai R., Xu Z., Zhang X., Yan Y., Yang L., Bian Y. Glycyrrhetinic acid regulates impaired macrophage autophagic flux in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.959495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z.G., Zhao Y., Wang Z.Y., Fan R.F., Liu Z.P., Wang L. Epigenetic regulator BRD4 is involved in cadmium-induced acute kidney injury via contributing to lysosomal dysfunction, autophagy blockade and oxidative stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022;423 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyamfi D., Everitt H.E., Tewfik I., Clemens D.L., Patel V.B. Hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction induced by fatty acids and ethanol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;53:2131–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyder O., Chung M., Cosgrove D., Herman J.M., Li Z., Firoozmand A., Gurakar A., Koteish A., Pawlik T.M. Cadmium exposure and liver disease among US adults. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2013;17:1265–1273. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2210-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller H., Dreyer C., Medin J., Mahfoudi A., Ozato K., Wahli W. Fatty acids and retinoids control lipid metabolism through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-retinoid X receptor heterodimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:2160–2164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten S. Integrated physiology and systems biology of PPARalpha. Mol. Metab. 2014;3:354–371. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.M., Wagner M., Xiao R., Kim K.H., Feng D., Lazar M.A., Moore D.D. Nutrient-sensing nuclear receptors coordinate autophagy. Nature. 2014;516:112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Ren L., Song G., Zhang P., Yang L., Chen X., Yu X., Chen S. Silibinin ameliorates fructose-induced lipid accumulation and activates autophagy in HepG2 cells. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets. 2019;19:632–642. doi: 10.2174/1871530319666190207163325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian C.Y., Chu B.X., Xia W.H., Wang Z.Y., Fan R.F., Wang L. Persistent activation of Nrf2 in a p62-dependent non-canonical manner aggravates lead-induced kidney injury by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting autophagy. J. Adv. Res. 2023;46:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2022.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian C.Y., Wei S., Li Z.F., Zhang S.H., Wang Z.Y., Wang L. Glyphosate-induced autophagy inhibition results in hepatic steatosis via mediating epigenetic reprogramming of PPARalpha in roosters. Environ. Pollut. 2023;324 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.I., Chang A.C., Lai J.L., Lin T.H., Tsai C.H., Chen P.C., Jiang Y.J., Lin L.W., Huang W.C., Yang S.F., Tang C.H. Melatonin interrupts osteoclast functioning and suppresses tumor-secreted RANKL expression: implications for bone metastases. Oncogene. 2021;40:1503–1515. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomba R., Friedman S.L., Shulman G.I. Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell. 2021;184:2537–2564. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean M.R. Melatonin: shining some light on pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020;116:2036–2037. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchester L.C., Coto-Montes A., Boga J.A., Andersen L.P., Zhou Z., Galano A., Vriend J., Tan D.X., Reiter R.J. Melatonin: an ancient molecule that makes oxygen metabolically tolerable. J. Pineal. Res. 2015;59:403–419. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orisakwe O.E., Oladipo O.O., Ajaezi G.C., Udowelle N.A. Horizontal and vertical distribution of heavy metals in farm produce and livestock around lead-contaminated goldmine in Dareta and Abare, Zamfara state, northern Nigeria. J. Environ. Public Health. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/3506949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsouris D., Reddy J.K., Muller M., Kersten S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha mediates the effects of high-fat diet on hepatic gene expression. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1508–1516. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinot F., Kreps S.E., Bachelet M., Hainaut P., Bakonyi M., Polla B.S. Cadmium in the environment: sources, mechanisms of biotoxicity, and biomarkers. Rev. Environ. Health. 2000;15:299–323. doi: 10.1515/reveh.2000.15.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posa L., Lopez-Canul M., Rullo L., De Gregorio D., Dominguez-Lopez S., Kaba Aboud M., Caputi F.F., Candeletti S., Romualdi P., Gobbi G. Nociceptive responses in melatonin MT2 receptor knockout mice compared to MT1 and double MT1/MT2 receptor knockout mice. J. Pineal Res. 2020;69:e12671. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafati Rahimzadeh M., Rafati Rahimzadeh M., Kazemi S., Moghadamnia A.A. Cadmium toxicity and treatment: an update. Caspian J. Intern. Med. 2017;8:135–145. doi: 10.22088/cjim.8.3.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnier M., Polizzi A., Smati S., Lukowicz C., Fougerat A., Lippi Y., Fouche E., Lasserre F., Naylies C., Betoulieres C., Barquissau V., Mouisel E., Bertrand-Michel J., Batut A., Saati T.A., Canlet C., Tremblay-Franco M., Ellero-Simatos S., Langin D., Postic C., Wahli W., Loiseau N., Guillou H., Montagner A. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of Pparalpha promotes NAFLD in the context of obesity. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:6489. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63579-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios E.R., Venancio E.T., Rocha N.F., Woods D.J., Vasconcelos S., Macedo D., Sousa F.C., Fonteles M.M. Melatonin: pharmacological aspects and clinical trends. Int. J. Neurosci. 2010;120:583–590. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2010.492921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robeva R., Kirilov G., Tomova A., Kumanov P. Melatonin-insulin interactions in patients with metabolic syndrome. J. Pineal Res. 2008;44:52–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonjans K., Staels B., Auwerx J. The peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARS) and their effects on lipid metabolism and adipocyte differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1302:93–109. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(96)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen P., Qadri S., Luukkonen P.K., Ragnarsdottir O., McGlinchey A., Jantti S., Juuti A., Arola J., Schlezinger J.J., Webster T.F., Oresic M., Yki-Jarvinen H., Hyotylainen T. Exposure to environmental contaminants is associated with altered hepatic lipid metabolism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2022;76:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Cuervo A.M. Lipophagy: connecting autophagy and lipid metabolism. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/282041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Kaushik S., Wang Y., Xiang Y., Novak I., Komatsu M., Tanaka K., Cuervo A.M., Czaja M.J. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaur M., Nigra A.E., Sanchez T.R., Navas-Acien A., Lazo M., Wu H.C. Association of blood manganese, selenium with steatosis, fibrosis in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2017-18. Environ. Res. 2022;213 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacchiotti A., Grossi I., Garcia-Gomez R., Patel G.A., Salvi A., Lavazza A., De Petro G., Monsalve M., Rezzani R. Melatonin effects on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease are related to MicroRNA-34a-5p/Sirt1 axis and autophagy. Cells. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/cells8091053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan N., Haring H.U., Cusi K. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: causes, diagnosis, cardiometabolic consequences, and treatment strategies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:313–324. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein R.M., Kang H.J., McCorvy J.D., Glatfelter G.C., Jones A.J., Che T., Slocum S., Huang X.P., Savych O., Moroz Y.S., Stauch B., Johansson L.C., Cherezov V., Kenakin T., Irwin J.J., Shoichet B.K., Roth B.L., Dubocovich M.L. Virtual discovery of melatonin receptor ligands to modulate circadian rhythms. Nature. 2020;579:609–614. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2027-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahan V., Atug O., Akin H., Eren F., Tahan G., Tarcin O., Uzun H., Ozdogan O., Tarcin O., Imeryuz N., Ozguner F., Celikel C., Avsar E., Tozun N. Melatonin ameliorates methionine- and choline-deficient diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. J. Pineal Res. 2009;46:401–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vamecq J., Latruffe N. Medical significance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Lancet. 1999;354:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Raalte D.H., Li M., Pritchard P.H., Wasan K.M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-alpha: a pharmacological target with a promising future. Pharm. Res. 2004;21:1531–1538. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000041444.06122.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videla L.A., Valenzuela R. Perspectives in liver redox imbalance: toxicological and pharmacological aspects underlying iron overloading, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and thyroid hormone action. Biofactors. 2022;48:400–415. doi: 10.1002/biof.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Chen S., Zeng S., Zhao Y., Zhu C., Deng B., Zhu G., Yin Y., Wang W., Hardeland R., Ren W. Melatonin in macrophage biology: current understanding and future perspectives. J. Pineal Res. 2019;66:e12547. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia L., Sun C., Zhu H., Zhai M., Zhang L., Jiang L., Hou P., Li J., Li K., Liu Z., Li B., Wang X., Yi W., Liang H., Jin Z., Yang J., Yi D., Liu J., Yu S., Duan W. Melatonin protects against thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection through SIRT1-dependent regulation of oxidative stress and vascular smooth muscle cell loss. J. Pineal Res. 2020;69:e12661. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Ocak U., Gao L., Tu S., Lenahan C.J., Zhang J., Shao A. Selective autophagy as a therapeutic target for neurological diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021;78:1369–1392. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03667-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi Z., Anstee Q.M., Marietti M., Hardy T., Henry L., Eslam M., George J., Bugianesi E. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;15:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang Y., Xu J., Tian F., Hu S., Chen Y., Fu Z. Melatonin attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via improving mitochondrial fusion/mitophagy and activating the AMPK-OPA1 signaling pathways. J. Pineal Res. 2019;66:e12542. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z., Wang X., Zhang R., Ma B., Niu S., Di X., Ni L., Liu C. Melatonin attenuates smoking-induced atherosclerosis by activating the Nrf2 pathway via NLRP3 inflammasomes in endothelial cells. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13:11363–11380. doi: 10.18632/aging.202829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H., Sun J., Wu B., Yuan Y., Gu J., Bian J., Liu X., Liu Z. Effects of cadmium and/or lead on autophagy and liver injury in rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020;198:206–215. doi: 10.1007/s12011-020-02045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H., Wang T., Yuan J., Sun J., Yuan Y., Gu J., Liu X., Bian J., Liu Z. Cadmium-induced cytotoxicity in mouse liver cells is associated with the disruption of autophagic flux via inhibiting the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes. Toxicol. Lett. 2020;321:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2019.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.