Abstract

This study evaluates the adoption of clinician billing for patient portal messages as e-visits, prompted by significant increases in patient messaging after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services expanded billing options for telemedicine including “e-visits,” defined as asynchronous patient portal messages that require medical decision-making and at least 5 minutes of clinician time over a 7-day period. During the pandemic, patient messaging increased by more than 50%, requiring a substantial amount of uncompensated clinician time.1,2 With the option to bill for a subset of messages, health care organizations began implementing workflows to bill qualifying patient messages as e-visits.3 However, level of clinician adoption and association with patient messaging behavior is unknown. We analyzed the implementation of clinician-initiated e-visit billing at a large academic medical center.

Methods

At UCSF Health, initially patients self-selected into an e-visit on sending a message. After minimal uptake, this process was retired in favor of clinicians determining when patient-initiated message threads qualify for billing as an e-visit. Patients are informed via the portal before sending a message that it may result in a bill, with information about cost sharing.4 Simultaneously, on November 14, 2021, an upgrade changed the patient portal user interface to encourage within-thread replies.

To capture clinician adoption of e-visit billing, we measured total patient medical advice message threads (each representing a back-and-forth exchange) and the subset billed as e-visits each week, and calculated the percentage of threads billed.2,5 Our sample covered November 1, 2020, through October 22, 2022, with November 1, 2020, as the start of patient-initiated e-visits and November 14, 2021, as the switchover to clinician-initiated e-visit billing. Next, we conducted interrupted time-series analyses with Newey-West standard errors6 for 5 week-level measures: (1) billed e-visits to assess clinician adoption, (2) patient message threads to assess patient response in terms of initiating new threads, (3) patient messages (both initial messages and responses) to assess patient response in terms of overall messaging volume, and (4-5) scheduled ambulatory visits and unscheduled telephone calls to assess a substitution effect. Analyses were conducted using Stata v17, with statistical significance set at 2-sided α of .05. Our study was deemed exempt from needing patient consent by the UCSF institutional review board.

Results

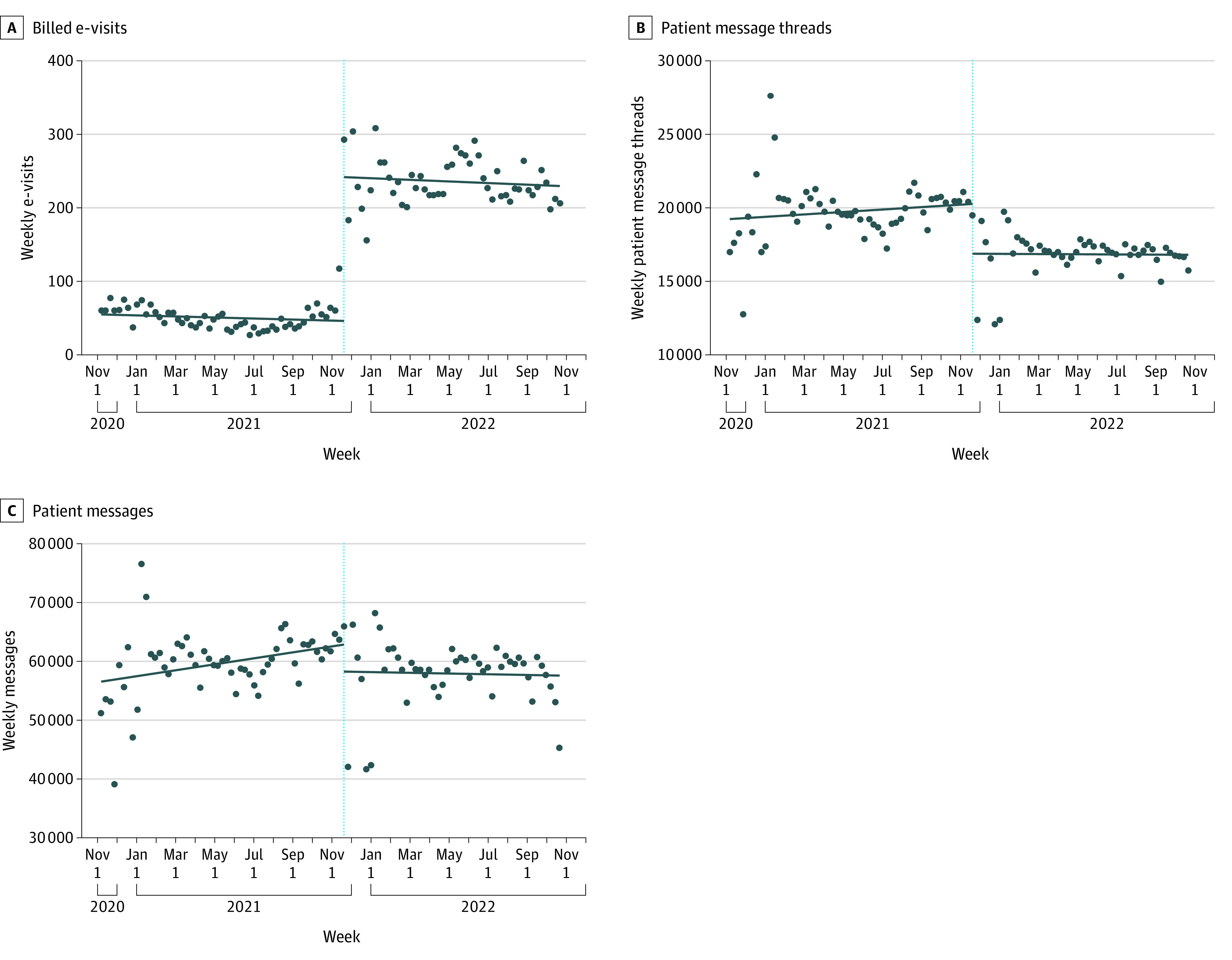

Prior to implementation of clinician-initiated e-visit billing, UCSF Health billed a mean of 50.6 (SD, 15.8) e-visits per week (0.26% of patient message threads) and received a mean of 19 739 (SD, 2003.5) patient threads and 59 648 (SD, 5486.9) patient messages per week. Following implementation, mean weekly e-visits increased to 235.7 (SD, 31.3) (1.40% of patient message threads), while mean patient message threads decreased to 16 838 (SD, 1491.6) and patient messages decreased to 57 925 (SD, 5580.4) per week (Figure). In interrupted time-series models, we found an immediate level change increase in weekly e-visits (β = 195.7 additional e-visits per week [95% CI, 171.7 to 219.6]; P < .001) and decreases in weekly patient message threads (β = −3388.2 message threads per week [95% CI, −4781.7 to −1994.7]; P < .001) and patient messages (β = −4594.2 messages per week [95% CI, −9025.3 to −163.1]; P = .04) (Table). No trend changes were observed. We found no significant level or trend changes in scheduled visits or unscheduled telephone calls.

Figure. Weekly Volume of e-Visits, Patient Message Threads, and Patient Messages.

Messages refer to patient medical advice request messages; threads are defined as a distinct conversation inclusive of all back-and-forth responses. All regression lines are a result of single-arm interrupted time-series models with Newey-West standard errors. The blue dotted line in each panel indicates November 14, 2021, which was the switchover to clinician-initiated e-visit billing.

Table. Association of Clinician-Initiated e-Visit Billing on e-Visits, Messages, Phone Calls, and Scheduled Visitsa.

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| e-Visits billed per week | ||

| Week trend | −0.02 (−0.10 to 0.05) | .53 |

| Immediate change following e-visit implementation | 195.68 (171.71 to 219.64) | <.001 |

| Postimplementation trend | −0.01 (−0.13 to 0.11) | .84 |

| Constant (preimplementation weekly level) | 54.93 (43.21 to 66.65) | <.001 |

| Patient message threads per week | ||

| Week trend | 2.72 (−4.68 to 10.12) | .47 |

| Immediate change following e-visit implementation | −3388.19 (−4781.72 to −1994.66) | <.001 |

| Postimplementation trend | −2.94 (−11.42 to 5.54) | .49 |

| Constant (preimplementation weekly level) | 19 233.56 (17 267.44 to 21 199.68) | <.001 |

| Patient messages per week | ||

| Weekly trend | 16.67 (−1.30 to 34.63) | .07 |

| Immediate change following e-visit implementation | −4594.16 (−9025.26 to −163.07) | .04 |

| Postimplementation trend | −18.67 (−44.62 to 7.28) | .16 |

| Constant (preimplementation weekly level) | 56 556.77 (51 774.63 to 61 338.91) | <.001 |

| Telephone calls per week | ||

| Week trend | −3.06 (−6.99 to 0.86) | .13 |

| Immediate change following e-visit implementation | −976.87 (−2194.91 to 241.18) | .12 |

| Postimplementation trend | 5.18 (−0.97 to 11.34) | .10 |

| Constant (preimplementation weekly level) | 19 313.49 (18 266.36 to 20 360.63) | <.001 |

| Scheduled visits per week | ||

| Week trend | 17.79 (4.57 to 31.01) | .01 |

| Immediate change following e-visit implementation | −4143.27 (−8900.03 to 613.49) | .09 |

| Postimplementation trend | −12.02 (−34.30 to 10.25) | .29 |

| Constant (preimplementation weekly level) | 45 427.62 (41 783.94 to 49 071.30) | <.001 |

All results are from interrupted time-series analysis regression models with Newey-West standard errors.

Discussion

This study found an association between implementation of clinician-initiated billing and an increase in e-visits, but adoption was low. Multiple factors likely contributed, including lack of awareness of e-visit workflow, perception that additional steps to complete e-visits were not worth the reimbursement, and concerns about negative patient perceptions of charging for messages.

Nonetheless, an association with a reduction in patient portal messaging (both threads and individual messages) was observed that may be attributable to awareness of the possibility of being billed. The reduction in threads may be partially due to the simultaneous change in the portal interface, but this should not have affected patient message volume. Study limitations include lack of assessment of e-visit profitability; inability to assess what proportion of patient-initiated message threads required medical decision-making and at least 5 minutes of time to meet e-visit billing criteria; clinician satisfaction with e-visit billing; and whether any reduction in messaging resulted in worse patient outcomes. Future research should investigate overall costs under different payment models and the effect of billing for messaging on outcomes, health equity, and patient and clinician satisfaction.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editor.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Tang M, Sharp C, Longhurst C, Huckman RS. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(3):453-460. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocab268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nath B, Williams B, Jeffery MM, et al. Trends in electronic health record inbox messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic in an ambulatory practice network in New England. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2131490. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.31490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinsky CA, Shanafelt TD, Ripp JA. The electronic health record inbox: recommendations for relief. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(15):4002-4003. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07766-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medical advice through MyChart messages: how it works and what it costs. ucsfhealth.org. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://www.ucsfhealth.org/mychart/Medical-Advice-Messages

- 5.Baxter SL, Saseendrakumar BR, Cheung M, et al. Association of electronic health record inbasket message characteristics with physician burnout. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2244363. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.44363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linden A. Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. Stata J. 2015;15(2):480-500. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1501500208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement