Abstract

It is unclear whether the literature on adolescent gender dysphoria (GD) provides evidence to inform clinical decision making adequately. In the final of a series of three papers, we sought to review published evidence systematically regarding the types of treatment being implemented among adolescents with GD, the age when different treatment types are instigated, and any outcomes measured within adolescence. Having searched PROSPERO and the Cochrane library for existing systematic reviews (and finding none at that time), we searched Ovid Medline 1946 –October week 4 2020, Embase 1947–present (updated daily), CINAHL 1983–2020, and PsycInfo 1914–2020. The final search was carried out on 2nd November 2020 using a core strategy including search terms for ‘adolescence’ and ‘gender dysphoria’ which was adapted according to the structure of each database. Papers were excluded if they did not clearly report on clinically-likely gender dysphoria, if they were focused on adult populations, if they did not include original data (epidemiological, clinical, or survey) on adolescents (aged at least 12 and under 18 years), or if they were not peer-reviewed journal publications. From 6202 potentially relevant articles (post deduplication), 19 papers from 6 countries representing between 835 and 1354 participants were included in our final sample. All studies were observational cohort studies, usually using retrospective record review (14); all were published in the previous 11 years (median 2018). There was significant overlap of study samples (accounted for in our quantitative synthesis). All papers were rated by two reviewers using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool v1·4 (CCAT). The CCAT quality ratings ranged from 71% to 95%, with a mean of 82%. Puberty suppression (PS) was generally induced with Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone analogues (GnRHa), and at a pooled mean age of 14.5 (±1.0) years. Cross Sex Hormone (CSH) therapy was initiated at a pooled mean of 16.2 (±1.0) years. Twenty-five participants from 2 samples were reported to have received surgical intervention (24 mastectomy, one vaginoplasty). Most changes to health parameters were inconclusive, except an observed decrease in bone density z-scores with puberty suppression, which then increased with hormone treatment. There may also be a risk for increased obesity. Some improvements were observed in global functioning and depressive symptoms once treatment was started. The most common side effects observed were acne, fatigue, changes in appetite, headaches, and mood swings. Adolescents presenting for GD intervention were usually offered puberty suppression or cross-sex hormones, but rarely surgical intervention. Reporting centres broadly followed established international guidance regarding age of treatment and treatments used. The evidence base for the outcomes of gender dysphoria treatment in adolescents is lacking. It is impossible from the included data to draw definitive conclusions regarding the safety of treatment. There remain areas of concern, particularly changes to bone density caused by puberty suppression, which may not be fully resolved with hormone treatment.

Introduction

This is the final of a series of three papers examining the literature on adolescent Gender Dysphoria (GD) [1, 2]. Some sections of the introductory and methodological text, and reference to methodological limitations, are necessarily repeated across all three papers. The definitions and terminology used in papers 1 and 2 were also used in the present paper [1, 2].

Gender Dysphoria (GD) is a categorical diagnosis in the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [3]. It is also used as a general descriptive term referring to a person’s discontent with assigned gender. In recent years, GD diagnoses have been increasingly made in child and adolescent services [4–6]. There has been a parallel increase in demand for gender transition interventions, particularly among natal females (NF) [4–6]. Current clinical guidance for gender transition in adolescence follows the so-called ‘Dutch model’, formalised in WPATH standards of care [7], where intervention is staged in accordance with a young person’s age and stage of pubertal development [8, 9]. The age at which a stage of intervention will be deemed appropriate is based partly on how reversible it is. The first stage, puberty suppression (PS; prevention of the development of secondary sexual characteristics), is reversible (although not without risks to health and wellbeing) [10], the second stage, cross-sex hormone (CSH) treatment (the administration of testosterone or oestradiol to promote development of secondary sex characteristics of identified gender), is reversible to some extent (although there is a lack of evidence regarding its longer term impact) [10], and the third stage, surgical intervention, is irreversible.

Whilst it is acknowledged that any intervention during puberty has to consider the potential negative impact on young people’s development, there is a surprising lack of evidence of outcomes. Research has raised safety concerns around cardiovascular health, insulin resistance, and changes to lipid profile. There have been observed cases of hypertension in NF without GD taking gonadotropin releasing hormone analogues (GnRHa) for precocious puberty [11, 12], and in three adolescent NF taking GnRHa for GD [13]. Cross-sex hormone (CSH) treatment also carries risk, with instances of an increase in thromboembolic events in adult transitioning natal males (NM) taking oral oestrogens, and worsening lipid profiles and increased insulin levels in adult transitioning NF [14]. This research has largely been conducted in adult populations, or very small samples of children / adolescents.

Given the potential risks, it is important to establish that a young person is deemed competent to make treatment decisions. This can be difficult as a key criterion is that an individual must be sufficiently mentally distressed to warrant intervention in the first place. Our previous paper demonstrated considerable mental health comorbidity among adolescents with GD [2]. The extent to which this affects treatment decision making is not clear from the existing evidence. There is evidence that most prepubertal children with GD desist once they reach puberty [15], whereas adults are more likely to persist [16]. There is some indication in the literature that adolescents are unlikely to desist [17, 18] and recent data from Butler et al. (2022) showed in a UK sample that desistance was more likely in those aged 15 years or under than those 16 or over (9.2% vs 4.4%) [19]. But there is a lack of relevant recent follow-up studies. There is an explicit lack of evidence on adolescent-onset GD, so the interplay between GD and other mental health (MH) factors in this phenomenon is not well understood [20].

Intense international debate regarding a number of issues relating to GD intervention in adolescence is ongoing, especially within Europe and North America where the main research active treatment centres are based [20]. One recent high profile legal case (Bell vs Tavistock [21]) attracted considerable attention from people and organisations with a range of strongly-held views both in favour of and against the ruling, illustrating the acknowledged lack of good quality evidence regarding treatment comorbidities and outcomes to inform service design [22, 23]. Concern in the UK led to the commissioning of the Cass review, which in March 2022 recommended the Tavistock Gender and Identity Development Service (GIDS) be closed down in favour of developing regional specialist centres [24] and highlighted the need not only for much better evidence but also for clinicians to be better informed and willing to work toward positive change [25]. Services are sometimes left having to make unilateral decisions against national guidance, e.g., the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden, changing their policy to limit puberty suppression to the context of clinical studies [26], and recently a new version of World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) standards of care have removed the lower age limit for certain treatments, leaving this decision to clinician judgement [27, 28].

Scope of the review

This review is the third in a three-part series addressing the current state of evidence on gender dysphoria experienced in adolescence. Our over-arching aim was to establish what the literature tells us about gender dysphoria in adolescence. We broke this down into seven specific questions (see below). Paper 1 [1] addressed questions 1-3c (italicised), Paper 2 [2] addressed question 4 (plain text), and Paper 3, the current paper, addresses questions 3d and 5–7 (bold text). Our overall research aim was addressed by seven specific questions:

What is the prevalence of GD in adolescence?

What are the proportions of natal males / females with GD in adolescence (a) and has this changed over time (b)?

What is the pattern of age at (a) onset (b) referral (c) assessment (d) treatment?

What is the pattern of mental health problems in this population?

What treatments have been used to address GD in adolescence?

What outcomes are associated with treatment/s for GD in adolescence?

What are the long-term outcomes for all (treated or otherwise) in this population?

The present paper focuses on questions 3d, 5–7. We have addressed questions 1, 2, 3a, 3b, and 3c in our first paper [1], and question 4 in paper 2 [2]. The methodology below includes the searches conducted for the whole review.

We set out to include any paper offering primary data in response to any of these questions.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The systematic review protocol was submitted to PROSPERO on the 28th November 2019, and registered on 17 March 2020 (registration number CRD42020162047). An update was uploaded on 2nd February 2021 to include specific detail on age criteria and clinical verification of condition. The review has been prepared according to PRISMA 2020 [29] guidelines (see Table 1 for checklist).

Table 1. PRISMA 2020 checklist.

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | 2 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | 4 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | 5 |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | 6–7 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | 6 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | 6, Table 2 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 7–8 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 8 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g. for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | 8 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g. participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | 8 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 8 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g. risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | 8 |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g. tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | 8 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | 9 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | 8–9 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | 8–9 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g. subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | N/A | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | N/A | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | N/A |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | N/A |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | 7, Fig 1 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | Table 4 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | Table 3 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | Table 9; Fig 2 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | Tables 5–8 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | 9–10 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | N/A | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | N/A | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | N/A | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | N/A |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | N/A |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | 16 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | 17–18 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | 17–18 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | 18 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | 6 |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | 6 | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | N/A | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Submission system |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | 19 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | Template: 8 Data: Tables 5–8 |

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Eligibility criteria

The volume of non-peer-reviewed literature in initial searches proved so great that we took the decision to only include peer-reviewed journal papers featuring original research data. This decision was made subsequent to initial PROSPERO registration, but prior to full text screening. Complete inclusion criteria were:

Focused on gender dysphoria or transgenderism;

Includes data on adolescents (aged 12–17 years inclusive);

Includes original data (not review paper or opinion piece);

Peer-reviewed publication (not theses or conference proceedings);

In English language.

Information sources

We searched PROSPERO and the Cochrane library for existing systematic reviews. We searched Ovid Medline 1946 –October week 4 2020, Embase 1947–present (updated daily), CINAHL 1983–2020, and PsycInfo 1914–2020. After selecting the final sample of articles, the first author used their reference lists as a secondary data source.

Search

The final search was carried out on 2nd November 2020 using a core strategy which was adapted according to the structure of each database. The core strategy included search terms for ‘adolescence’ and ‘gender dysphoria’. This was kept deliberately broad in order to ensure any studies on the subject could be screened for eligibility. The specific search strategy employed in EMBASE is given below, and represents the format followed with the others. The specific search strategies employed in each database are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Search terms.

| EMBASE | Ovid Medline | CINAHL | PsycInfo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescence | 1. Exp adolescence/ 2. (adolesc* or teen* or puberty*).tw. |

1. Exp adolescence/ 2. (adolesc* or teen* or puberty*).tw. |

1. (MH “Adolescence+”) 2. TI adolesc* OR TI teen* OR TI pubert* OR AB adolesc* OR AB teen* OR AB pubert* |

1. TI adolescence OR AB adolescence 2. TI adolesc* OR TI teen* OR TI pubert* 3. AB adolesc* OR AB teen* OR AB pubert* |

| Gender Dysphoria | 3. exp gender dysphoria/ 4. exp transgender/ 5. sex reassignment/ 6. (gender dysphoria or gender identity or transsex* or trans sex or transgender or trans gender or sex reassignment).tw. |

2. exp gender dysphoria/ 3. exp transgender/ 4. Exp Sex Reassignment Procedures/ 5. (gender dysphoria or gender identity or transsex* or trans sex or transgender or trans gender or sex reassignment).tw. |

3. (MH “Gender Dysphoria”) 4. (MH “Transgender Persons”) OR (MH “Transsexuals”) 5. (MH “Sex Reassignment Procedures+”) 6. TI gender dysphoria OR AB gender dysphoria OR TI gender identity disorder OR AB gender identity disorder OR TI transsex* OR AB transsex* OR TI trans sex* OR AB trans sex* OR TI transgender OR AB transgender OR TI trans gender OR AB trans gender 7. TI sex reassignment OR AB sex reassignment OR TI gender reassignment OR AB gender reassignment |

4. DE “Gender Dysphoria” OR DE “Gender Nonconforming” OR DE “Gender Reassignment” OR DE “Gender Identity” OR DE “Transsexualism” OR DE “Transgender” 5. TI gender dysphoria OR TI gender identity disorder OR TI transsex* OR TI trans sex* OR TI transgender OR TI trans gender OR TI sex reassignment OR TI gender reassignment 6. AB gender dysphoria OR AB gender identity disorder OR AB transsex* OR AB trans sex* OR AB transgender OR AB trans gender OR AB sex reassignment OR AB gender reassignment |

| Combination terms | 7. 1 OR 2 8. 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 9. 7 AND 8 |

7. 1 OR 2 8. 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 9. 7 AND 8 |

8. 1 OR 2 9. 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 10. 8 AND 9 |

7. 1 OR 2 OR 3 8. 4 OR 5 OR 6 9. 7 AND 8 |

EMBASE search

Exp adolescence/

(adolesc* or teen* or puberty*).tw.

1 or 2

exp gender dysphoria/

exp transgender/

sex reassignment/

(gender dysphoria or gender identity or transsex* or trans sex or transgender or trans gender or sex reassignment).tw.

4 or 5 or 6 or 7

3 and 8

Study selection

The study selection process is illustrated in Fig 1. We used Endnote v. X7.8 to manage all references, and followed the de-duplication and management strategies set out in Bramer et al. (2016) [30] and Peters (2017) [31] respectively.

Fig 1. PRISMA diagram.

In the first stage of screening, papers were excluded based on their title or abstract if they did not clearly report on gender dysphoria or transgenderism and if they were focused on adult populations. In the second stage of screening, papers were excluded on the basis of title and abstract if they did not include original data (epidemiological, clinical, or survey) on adolescents (aged at least 12 and under 18 years). At both stages papers were retained if there was insufficient information to exclude them.

Full-text files were obtained for the remaining records.

Papers were rejected at this stage if they:

Contained no original data (including literature and clinical reviews, journalistic / editorial pieces, letters and commentaries);

Included only case studies or selected case series;

Pertained to conditions other than GD (e.g., Disorders of sexual development or HIV);

Did not include clinically-identified GD (e.g., survey where participants self-identify, with no clinical contact);

Pertained to populations other than those with GD (e.g., LGBTQ more broadly);

Pertained to populations including or restricted to those aged 18 years or older. This included papers where adolescents and adults were included in the same sample, but adolescents were not separately reported (in many cases age range was not reported and so a ‘balance of probabilities’ assessment had to be made based on the reported mean age);

Pertained to populations restricted to those aged under 12 years of age. This included papers where adolescents and children were included in the same sample, but the majority of participants were clearly under 12 (based on mean or median age);

Where participants were practitioners, not patients;

Referred only to conference proceedings;

Were written in a non-European language (e.g., Turkish);

Could not be obtained (including due to being published in non-English language journals, or in theses).

Following initial full text screening, all remaining papers were assessed by a second reviewer to reduce the risk of inclusion bias. Where reviewers reached a different conclusion, discussion took place to reach consensus. If agreement could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted, and discussion used to reach consensus amongst all three reviewers.

Data extracted from eligible papers were tabulated and used in the qualitative synthesis. Given the limited number of specialist treatment centres globally, we assessed how many of the included papers featured the same or overlapping samples.

Papers included in the sub-sample for the present analysis contained some data on either age at treatment commencement, type of treatment administered, or treatment outcomes.

Quality assessment

All papers were rated by two reviewers using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool v1·4 (CCAT [32]). CCAT is suitable for a range of methodological approaches, assessing papers in terms of eight categories: Preliminaries (overall clarity and quality); Introduction; Design; Sampling; Data collection; Ethical matters; Results; Discussion. Each category is rated out of 5 and all eight categories summed to give a total out of 40 (converted to a percentage). In the present review, each paper was then assigned to one of five categories, based on the average rating of the reviewers, where a rating of 0–20% was coded 1 (poorest quality), and 81–100% coded 5 (highest quality). Inter-rater reliability was shown to be very good (k = 0·93, SE = 0·07).

Data collection process

Data were extracted from the papers using the CCAT form (https://conchra.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/CCAT-form-v1.4.pdf) by two reviewers per paper and compiled by the first author (LT). Once compiled, instances of overlap between papers (i.e., if the same sample was described in two papers) were identified and tabulated, and the final sample for each question defined.

Results

Number of studies included, retained and excluded

The PRISMA diagram in Fig 1 provides details of the screening and exclusion process. The searches returned 8655 results, reduced to 6202 following de-duplication. Titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer (LT) and 4659 records excluded after initial screening and a further 699 excluded on second stage title / abstract screening. This left 553 eligible for full text screening. An initial screening (LT) of full texts reduced the number of records to 155. Forty-seven papers were included in the final dataset, of which 19 included data for the present paper. Full characteristics of included studies are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Study characteristics.

| ID | Country | Reference | Design | Setting | N | Age (years) | Male natal sex (%) | Date range | GD status | Treatment stage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||

| 1 | Belgium | Tack, et al. (2016). Consecutive lynestrenol and cross-sex hormone treatment in biological female adolescents with gender dysphoria: A retrospective analysis. Hormone Research in Paediatrics, 86 (Supplement 1), 268–269. | obs, retro, longit, interv | Division of Pediatric Endocrinology, Ghent University*, Belgium | 43 | mean age start of progestins 15.8 mean age start of CSH 17.4 |

0 | 2010–2015 | 2 | |||

| 2 | Tack, et al. (2017). Consecutive Cyproterone Acetate and Estradiol Treatment in Late-Pubertal Transgender Female Adolescents. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(5), 747–757. | obs, retro, longit, interv | Division of Pediatric Endocrinology, Ghent University*, Belgium | 27 | Mean age at start of CA 16y6m, CA+oestradiol 17y7m | 100.0 | 2008–2016 | 1 | ||||

| 3 | Tack, et al. (2018). Proandrogenic and Antiandrogenic Progestins in Transgender Youth: Differential Effects on Body Composition and Bone Metabolism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 103(6), 2147–2156. | obs, retro, longit, interv | Division of Pediatric Endocrinology, Ghent University* | 65$ | Mean NF: 16·2±1·05 Mean NM:16·3±1·21 | 32·3 | 2011–2017 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Germany | Becker-Hebly, et al. (2020). Psychosocial health in adolescents and young adults with gender dysphoria before and after gender-affirming medical interventions: a descriptive study from the Hamburg Gender Identity Service. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. | obs, prosp, longit, interv | Gender Identity Service, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany | 54 | 11.21–17.34 | 14.8 | Sept 2013 –Jun 2017 | 1 | |||

| 5 | Israel | Perl, et al. (2020). Blood Pressure Dynamics After Pubertal Suppression with Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Analogs Followed by Testosterone Treatment in Transgender Male Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Lgbt Health, 7(6), 340–344. | obs, retro, longit | Gender Dysphoria Clinic at Dana-Dwek Children’s Hospital, Gender Clinic, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Israel | 15 | GnRHa group (n15): 14.4±1.0 GAH group (n9): 15.1±0.9 |

100 | 2013–2018 | 2 | |||

| 6 | Nether-lands | de Vries, et al. (2011). Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: A prospective follow-up study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(8), 2276–2283. | obs & comp, prosp, longit | VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam (forerunner to CEGD) | 70 | 11·1–17·0 | 47·1 | 2000–2008 | 1 | |||

| 7 | Nether-lands | Klaver, et al. (2018). Early Hormonal Treatment Affects Body Composition and Body Shape in Young Transgender Adolescents. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(2), 251–260. | obs, retro, longit, interv | VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam (forerunner to CEGD) | 192 | Mean at start puberty blocker NM 14.5±1.8 NF 15.3±2.0 | 37 | 1998–2014 | 1 | |||

| 8 | Nether-lands | Klaver, et al. (2020). Hormonal Treatment and Cardiovascular Risk Profile in Transgender Adolescents. Pediatrics, 145(3), 03. | obs, retro, longit, interv | VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam (forerunner to CEGD) | 192 | Mean at start of puberty blocker NM 14.6±1.8 NF 15.2±2.0 | 37 | 1998–2015 | 1 | |||

| 9 | Nether-lands | Schagen, et al. (2020). Bone Development in Transgender Adolescents Treated With GnRH Analogues and Subsequent Gender-Affirming Hormones. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 105(12), 01. | obs, prosp, longit, interv | VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam (forerunner to CEGD)*, Netherlands | 121 | NM 14.1±1.7 NF 14.5±2.0 |

42 | Eligible for treatment 1998–2009 | 1 | |||

| 10 | Nether-lands | Stoffers, I. E., de Vries, M. C., & Hannema, S. E. (2019). Physical changes, laboratory parameters, and bone mineral density during testosterone treatment in adolescents with gender dysphoria. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(9), 1459–1468. | obs, retro, x-sect, interv | not stated, but assume Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria (CEGD), Amsterdam | 62 NF | 11.8–18.0 | N/A | Nov 2010-Aug 2018 | 1 | |||

| 11 | UK | Costa, et al. (2015). Psychological Support, Puberty Suppression, and Psychosocial Functioning in Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(11), 2206–2214. | obs & comp, retro, longit, interv | Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock & Portman, London | 201 (Control: 169 CAMHS Stockholm cases) | 12–17 | 37·8 | 2010–2014 | 1 | |||

| 12 | UK | Joseph, et al. (2019). The effect of GnRH analogue treatment on bone mineral density in young adolescents with gender dysphoria: findings from a large national cohort. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism: JPEM., 31. | obs, retro, longit, interv | Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock & UCLH Early Intervention programme @ national endocrine clinic, London | 70 | 12–14 | 44·3 | 2011–2016 | 2 | |||

| 13 | UK | Russell, et al. (2020). A Longitudinal Study of Features Associated with Autism Spectrum in Clinic Referred, Gender Diverse Adolescents Accessing Puberty Suppression Treatment. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. | obs, retro, x-sect | Gender Identity Service, Tavistock & Portman, London | 95 | 9·9–15·9 (mean 13·6±0·11) | 40 | Not given | 2 | |||

| 14 | USA | Chen, et al. (2016). Characteristics of Referrals for Gender Dysphoria over a 13-Year Period. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(3), 369–371. | obs, retro, x-sect | paediatric endocrinology clinic, Indiana | 38 | Mean age 14·4±3·2 | 42·1 | 1/1/02–1/4/15 | 3 | |||

| 15 | USA | Jensen, et al. (2019). Effect of Concurrent Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Treatment on Dose and Side Effects of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy in Adolescent Transgender Patients. Transgender Health, 4(1), 300–303. | obs, retro, x-sect | ’a pediatric gender clinic at a tertiary medical center’, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago* | 17 | 11.4–15.6 | 35.3 | Treatment before Mar 2016, data extracted to end Jan 2018 | 2 | |||

| 16 | USA | Kuper, et al. (2020). Body Dissatisfaction and Mental Health Outcomes of Youth on Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy. Pediatrics, 145(4), 04 | obs, prosp, longit, interv | ’a multidisciplinary program in Dallas, Texas’ | 148 | 9–18 | 37 | Initially assessed 2014–2018 | 1 | |||

| 17 | USA | Lee, et al. (2020). Low Bone Mineral Density in Early Pubertal Transgender/Gender Diverse Youth: Findings From the Trans Youth Care Study. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 4(9), 1–12. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvaa065 | obs, prosp, x-sect | Trans Youth Care Study: Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Lurie Children’s Hospital, Boston Children’s Hospital, and University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital | 63 | Mean at start of puberty blocker NM 12.1±1.3 NF 11.0±1.4 | 52.4 | Not given | 1* | |||

| 18 | USA | Lopez, et al. (2018). Trends in the use of puberty blockers among transgender children in the United States. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, 31(6), 665–670. | obs, retro, x-sect | US Pediatric Health and Information System (PHIS) database | 40a | 8·8–17·8a | 46·3 | 2010-2015a | 3 | |||

| 19 | USA | Nahata, et al. (2017). Mental Health Concerns and Insurance Denials Among Transgender Adolescents. LGBT Health, 4(3), 188–193. | obs, retro, x-sect | ’gender program’ at an ’urban, Mid-western, pediatric academic center’, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio* | 79 | 9–18 | 35·4 | 2014–2016 | 3 | |||

Key

* = author’s affiliation. No specific setting given obs = observational comp = comparative

$ = authors report sample overlap prosp = prospective retro = retrospective

a = Max age of whole sample 18.8. Only data on those under 18 years used in this review. longit = longitudinal x-sect = cross-sectional

interv = intervention study

GD status codes: 1) clinical diagnosis using DSM-III / IV / IV-TR / 5; 2) active patients within clinic; 3) data mined using ICD 9 / 10 codes and/or relevant keywords; 4) Under assessment at clinic–beyond referral stage.

Treatment stage: 1 = puberty suppression; 2 = cross sex hormones; 3 = surgical intervention

Study characteristics

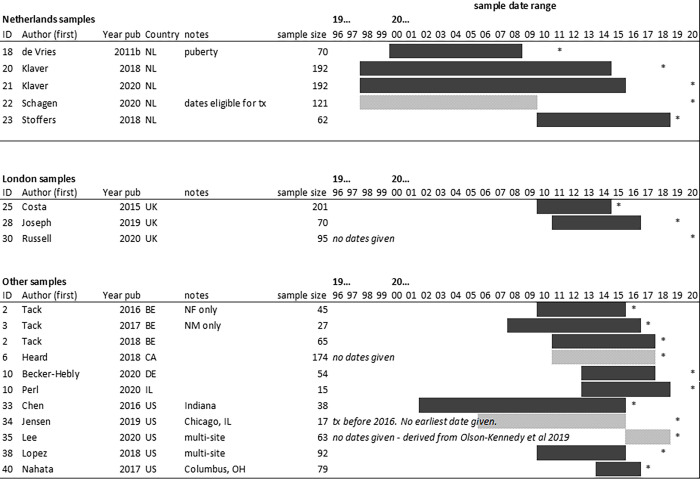

All of the included studies originated from a small number of centres in wealthy nations: USA (n = 6), Netherlands (n = 5), UK (n = 3), Belgium (n = 3), Germany (n = 1), and Israel (n = 1). The Belgian studies came from the same centre, an adolescent gender clinic in Ghent. The Dutch studies were from the same centre in Amsterdam. The UK studies consisted of samples assessed at the Gender Identity Development Service in London. As such there may be overlap in the samples studied but this was not always clearly reported. Both Klaver et al. papers [33, 34] examine the same cohort but investigate different parameters. There is partial overlap reported in Tack. et al. (2018) [35] with the previous two Tack et al. (2016 and 2017) papers [36, 37], however the degree of overlap is not fully described. Overlap was therefore estimated using dates of record search or dates of inclusion. Fig 2 provides a graphic representation of likely sample overlap.

Fig 2. Overlap between included samples.

Key: tx: treatment. *: year of publication. NL: Netherlands; UK: United Kingdom; BE: Belgium; CA: Canada; DE: Germany; IL: Israel; US: United States.

All papers included were published within the last eleven years, with the earliest having been published in 2011 (de Vries et al. [38]). Reported dates of treatment ranged from 1998 to 2018 inclusive. The majority (n = 13) of studies were retrospective in nature, and predominantly took their data from review of medical records. None of the studies included in this paper were randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Most papers (n = 14) contained both NF and NM participants. Three (Perl et al. [39], Stoffers et al. [40], Tack et al., 2016 [36]) contained data pertaining to NF only, and one (Tack et al., 2017 [37]) contained data pertaining to NM only. In total, approximately 1300 adolescents who had been treated for GD were included in this analysis. Of this, around 1102 were treated with puberty suppression (PS), and 727 were treated with CSH, either in addition to PS (n = 506) or as monotherapy (n = 221).

All nineteen papers included data on the treatments offered for adolescent GD. All nineteen included data on PS, of which six [35, 41–45] focused on this exclusively. Of those focusing exclusively on PS, four [42–45] analysed GnRHa use, one (Tack et al. 2018) [35] analysed the effects of progestins exclusively, and one (Lee et al.) only contained treatment used and age of treatment data [41]. Thirteen papers looked at the effects of both PS and CSH. Of these, nine looked at the effects of GnRHa and CSH, two looked at the effects of progestins and CSH [36, 37] and one (Chen et al.) [46] looked at the effects of GnRHa, progestins, androgen-receptor blockers and CSH. Eight analysed both oestrogen and testosterone therapies, and two [39, 40] analysed testosterone solely.

Patients in most papers (n = 15) had a GD diagnosis according to either the DSM-IV or V definition of Gender Dysphoria. Two papers [42, 47] used ICD-9/10 definitions. Perl et al. [39] did not describe how patients were diagnosed with GD, but did state the participants had sought out and had been treated for GD at a Paediatric Gender Dysphoria Clinic. Likewise Jensen et al. [48] used data from adolescent participants who had received or were receiving CSH therapy at a paediatric gender clinic for GD.

A substantial group of papers narrowly missed inclusion criteria, mostly on the age criterion and some on the clinically likely GD criterion, and were not included in the final sample of reviewed papers. We documented characteristics of all studies excluded at the final full text screen in Table 4.

Table 4. Papers excluded at second full text screen (i.e., closely missed meeting inclusion criteria).

| ID | Reference | Date | Location & setting | Reason for exclusion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Achille, C., Taggart, T., Eaton, N. R., Osipoff, J., Tafuri, K., Lane, A., & Wilson, T. A. (2020). Longitudinal impact of gender-affirming endocrine intervention on the mental health and well-being of transgender youths: preliminary results. International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology, 2020, 8. | 2020 | USA New York, Stoney Brook Children’s Hospital |

1 Mean age 16.2±2.2 |

66% NF MH improved with endocrine intervention Small sample (n = 50) |

| 2 | Aitken, et al. (2015). Evidence for an altered sex ratio in clinic-referred adolescents with gender dysphoria. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(3), 756–763. | 2015 | 1) CANADA Gender Identity Service, Child, Youth and Family Services (CYFS), Toronto 2) NETHERLANDS Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria (CEGD) |

1, 2 1) unclear if GD clinically verified 2) Eldest participant 19 years |

Useful information in change of gender in those presenting to services over time. |

| 3 | Akgul, G. Y., Ayaz, A. B., Yildirim, B., & Fis, N. P. (2018). Autistic Traits and Executive Functions in Children and Adolescents With Gender Dysphoria. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 44(7), 619–626. | 2018 | TURKEY Marmara University Pendik Education and Training Hospital’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 4 | Alastanos, J. N., & Mullen, S. (2017). Psychiatric admission in adolescent transgender patients: A case series. The Mental Health Clinician, 7(4), 172–175. | 2017 | USA ‘an inpatient psychiatry unit’ |

3 Selected case series |

All 5 participants were psychiatric inpatients within a 5 week period |

| 5 | Alberse, et al. (2019). Self-perception of transgender clinic referred gender diverse children and adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 388–401. | 2019 | NETHERLANDS Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria (CEGD), Amsterdam |

1 Max age 18.03 |

Poor self-perception common. NF perceive themselves more positively in general. |

| 6 | Alexander, G. M., & Peterson, B. S. (2004). Testing the prenatal hormone hypothesis of tic-related disorders: gender identity and gender role behavior. Development & Psychopathology, 16(2), 407–420. | 2004 | USA Child Study Center of Yale University in New Haven, CT |

6 |

Participants receiving treatment for Tourette Syndrome, not presenting for GD |

| 7 | Amir, H., Oren, A., Klochendler Frishman, E., Sapir, O., Shufaro, Y., Segev Becker, A.,… Ben-Haroush, A. (2020). Oocyte retrieval outcomes among adolescent transgender males. Journal of Assisted Reproduction & Genetics, 37(7), 1737–1744. | 2020 | ISRAEL IVF Unit, Fertility Institute in Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center and IVF and the Infertility Unit, Helen Schneider Hospital for Women, Rabin Medical Center |

3 |

Sample was 11 NF presenting specifically for fertility preservation |

| 8 | Amir, H., Yaish, I., Oren, A., Groutz, A., Greenman, Y., & Azem, F. (2020). Fertility preservation rates among transgender women compared with transgender men receiving comprehensive fertility counselling. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 41(3), 546–554. | 2020 | ISRAEL Gender Dysphoria Clinic at Dana-Dwek Children’s Hospital, Gender Clinic, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center |

0 | Included in Paper 1 (epidemiology) |

| 9 | Anzani, A., Panfilis, C., Scandurra, C., & Prunas, A. (2020). Personality Disorders and Personality Profiles in a Sample of Transgender Individuals Requesting Gender-Affirming Treatments. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 17(5), 27. | 2020 | ITALY gender clinic at Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital, Milan |

3 | Very small sub-sample (n = 4) in adolescent age range |

| 10 | Arnoldussen, et al. (2019). Re-evaluation of the Dutch approach: are recently referred transgender youth different compared to earlier referrals? European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. | 2019 | NETHERLANDS Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria (CEGD), Amsterdam |

1 Max age 18.08 |

From 2000–2016, sharp increase in cases from 2012 to 2016; sharp uptick in NF relative to NM since 2013 |

| 11 | Avila, J. T., Golden, N. H., & Aye, T. (2019). Eating Disorder Screening in Transgender Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(6), 815–817. | 2019 | USA ‘an academic multidisciplinary gender clinic’ Stanford University School of Medicine* |

1, 2 No distinct data on adolescents in sample. |

Most (63%) disclosed weight manipulation for gender-affirming purposes, including 11% of NF for menstrual suppression. |

| 12 | Barnard, E. P., Dhar, C. P., Rothenberg, S. S., Menke, M. N., Witchel, S. F., Montano, G. T.,… Valli-Pulaski, H. (2019). Fertility Preservation Outcomes in Adolescent and Young Adult Feminizing Transgender Patients. Pediatrics, 144(3). | 2019 | USA Magee-Womens Research Institute, Pittsburgh* |

1, 3 |

Very small subsample (n = 11); only 4 in adolescence at time of assessment (consultation). |

| 13 | Becerra-Culqui, T. A., Liu, Y., Nash, R., Cromwell, L., Flanders, W. D., Getahun, D.,… Goodman, M. (2018). Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics, 141 (5) (no pagination)(e20173845). | 2018 | USA California and Georgia, US, Kaiser-Permanente records |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 14 | Becerra-Fernández, A., Rodríguez-Molina, J., Ly-Pen, D., Asenjo-Araque, N., Lucio-Pérez, M., Cuchí-Alfaro, M.,… Aguilar-Vilas, M. V. (2017). Prevalence, Incidence, and Sex Ratio of Transsexualism in the Autonomous Region of Madrid (Spain) According to Healthcare Demand. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(5), 1307–1312. doi:10.1007/s10508-017-0955-z | 2017 | SPAIN Gender Identity Unit, Madrid |

1 No separate data on adolescents (includes ≥18 yrs) |

Higher prevalence rate than other countries: attributed to easily accessible services and positive social and legal climate in Spain. |

| 15 | Bechard, M., VanderLaan, D. P., Wood, H., Wasserman, L., & Zucker, K. J. (2017). Psychosocial and Psychological Vulnerability in Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria: A "Proof of Principle" Study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(7), 678–688. | 2017 | CANADA Gender Identity Service, CYFS, Toronto |

1 No separate data on adolescents (includes ≥18 yrs) |

Mean of 5.56/13 ‘psychological vulnerability factors’ amongst sample. |

| 16 | Becker, I., Auer, M., Barkmann, C., Fuss, J., Moller, B., Nieder, T. O.,… Richter-Appelt, H. (2018). A Cross-Sectional Multicenter Study of Multidimensional Body Image in Adolescents and Adults with Gender Dysphoria Before and After Transition-Related Medical Interventions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(8), 2335–2347. | 2018 | GERMANY Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Psycho-Somatics, University Medical Centre, Hamburg |

1 No separate data on adolescents (includes ≥18 yrs) |

Body image generally poor; some (but not all) aspects of poor body image improved with intervention. |

| 17 | Biggs, M. (2020). Gender Dysphoria and Psychological Functioning in Adolescents Treated with GnRHa: Comparing Dutch and English Prospective Studies. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(7), 2231–2236. | 2020 | Secondary data: NETHERLANDS and UK | 5 No original data |

Useful critique of existing data: compares Dutch and English samples |

| 18 | Bonifacio, J. H., Maser, C., Stadelman, K., & Palmert, M. (2019). Management of gender dysphoria in adolescents in primary care. Cmaj, 191(3), E69-E75. | 2019 | N/A–review paper (Authors based in Toronto, CANADA) |

5 |

Increase in cases will mean primary care services have to be prepared |

| 19 | Bradley, S. J. (1978). Gender identity problems of children and adolescents: The establishment of a special clinic. The Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal / La Revue de l’Association des psychiatres du Canada, 23(3), 175–183. | 1978 | CANADA Toronto, southwestern Ontario |

3 Small N. |

No objective data–clinical impressions only. Interesting early paper on GD and Toronto clinical service. |

| 20 | Brocksmith, V. M., Alradadi, R. S., Chen, M., & Eugster, E. A. (2018). Baseline characteristics of gender dysphoric youth. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, 31(12), 1367–1369. | 2018 | USA pediatric endocrine clinic, Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis |

1 No separate data on adolescents (includes ≥18 yrs) |

High proportion of NF to NM 50% overweight / obese Anxiety higher in NF Some indication of adolescent-onset being more common in recent (post-2014) participants |

| 21 | Bui, H. N., Schagen, S. E. E., Klink, D. T., Delemarre-Van De Waal, H. A., Blankenstein, M. A., & Heijboer, A. C. (2013). Salivary testosterone in female-To-male transgender adolescents during treatment with intra-muscular injectable testosterone esters. Steroids, 78(1), 91–95. | 2013 | NETHERLANDS VU Medical Center, Amsterdam |

1, 3 | Technical paper focused on novel method of measuring salivary testosterone levels. |

| 22 | Burke, S. M., Kreukels, B. P. C., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Veltman, D. J., Klink, D. T., & Bakker, J. (2016). Male-typical visuospatial functioning in gynephilic girls with gender dysphoria—Organizational and activational effects of testosterone. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 41(6), 395–404. | 2016 | NETHERLANDS Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria (CEGD), Amsterdam |

3 | Small selected sample, unlikely to be representative. Psychiatric disorder an exclusion criterion. |

| 23 | Butler, G., De Graaf, N., Wren, B., & Carmichael, P. (2018). Assessment and support of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 103(7), 631–636. | 2018 | UK Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock, London |

5 Commissioned review |

Some data on age and gender |

| 24 | Calzo, J. P., & Blashill, A. J. (2018). Child Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1090–1092. | 2018 | USA San Diego (Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study) |

2, 4 | Self-identification of sexuality and gender status, with very small N identifying as transgender. Sample aged 9–10 yrs. |

| 25 | Chen, D., Simons, L., Johnson, E. K., Lockart, B. A., & Finlayson, C. (2017). Fertility Preservation for Transgender Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(1), 120–123. | 2017 | USA Gender & Sex Development Program (GSDP), Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago |

3 | Very small sample. 11/13 were adolescents. Sample was 11 adolescents presenting specifically for fertility preservation. |

| 26 | Chiniara, L. N., Bonifacio, H. J., & Palmert, M. R. (2018). Characteristics of adolescents referred to a gender clinic: Are youth seen now different from those in initial reports? Hormone Research in Paediatrics, 89(6), 434–441. | 2018 | CANADA Transgender Youth Clinic (TYC), The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 27 | Chodzen, G., Hidalgo, M. A., Chen, D., & Garofalo, R. (2019). Minority Stress Factors Associated With Depression and Anxiety Among Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 467–471. | 2019 | USA Division of Adolescent Medicine, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago* |

2 Sample self-identified as transgender and gender-nonconforming (TGNC) |

High levels of anxiety and depression. |

| 28 | Clark, T. C., Lucassen, M. F. G., Bullen, P., Denny, S. J., Fleming, T. M., Robinson, E. M., & Rossen, F. V. (2014). The health and well-being of transgender high school students: Results from the New Zealand adolescent health survey (youth’12). Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(1), 93–99. | 2014 | NEW ZEALAND National population-based survey |

2 Survey data. Participants self-identify as transgender. |

Adolescents identifying as transgender have considerable health and wellbeing needs relative to their peers. |

| 29 | Cohen, L., De Ruiter, C., Ringelberg, H., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (1997). Psychological functioning of adolescent transsexuals: Personality and psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 187–196. | 1997 | NETHERLANDS VU Medical Center, Amsterdam |

1 | Mean age 17.2±1.81 Rorschach methodology–not useful for our review |

| 30 | Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Van Goozen, S. H. M. (1997). Sex reassignment of adolescent transsexuals: A follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(2), 263–271. | 1997 | NETHERLANDS University Medical Centre, Utrecht (moved to VUMC / CEGD in 2002). |

1, 3 |

GD resolved at post-surgery follow-up. No expression of regret. |

| 31 | Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Van Goozen, S. H. M. (2002). Adolescents who are eligible for sex reassignment surgery: Parental reports of emotional and behavioural problems. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(3), 412–422. | 2002 | NETHERLANDS University Medical Centre, Utrecht (moved to VUmc / CEGD in 2002) |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 32 | Coolidge, F. L., Thede, L. L., & Young, S. E. (2002). The heritability of gender identity disorder in a child and adolescent twin sample. Behavior Genetics, 32(4), 251–257. | 2002 | USA Colorado Springs, Colorado |

2 | Twin methdology to investigate heritability. |

| 33 | Day, J. K., Fish, J. N., Perez-Brumer, A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Russell, S. T. (2017). Transgender Youth Substance Use Disparities: Results From a Population-Based Sample. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(6), 729–735. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.06.024 | 2017 | USA 2013–2015 Biennial Statewide California Student Survey |

2 Survey data. Participants self-identify as transgender. |

Transgender youth at increased risk for substance misuse. Some psychosocial factors may mediate this. |

| 34 | de Graaf, et al. (2018). Sex ratio in children and adolescents referred to the Gender Identity Development Service in the UK (2009–2016). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(5), 1301–1304. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1204-9 | 2018 | UK Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock, London |

2 Referrals only–no GD clinical verification |

Significant increases year-on-year, from only 39 adolescent referrals in 2009 to almost 1500 in 2016; average increase rate of referrals higher in NF. |

| 35 | de Graaf, N. M., Carmichael, P., Steensma, T. D., & Zucker, K. J. (2018). Evidence for a Change in the Sex Ratio of Children Referred for Gender Dysphoria: Data From the Gender Identity Development Service in London (2000–2017). Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(10), 1381–1383. | 2018 | UK Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock, London |

4 | NM referred at younger age than NF. Recent increases have higher proportion NF (as observed in adolescent samples). |

| 36 | de Graaf, N. M., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Carmichael, P., de Vries, A. L. C., Dhondt, K., Laridaen, J.,… Steensma, T. D. (2018). Psychological functioning in adolescents referred to specialist gender identity clinics across Europe: A clinical comparison study between four clinics. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(7), 909–919. doi:10.1007/s00787-017-1098-4 | 2018 | MULTI (a) Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria (CEGD), Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS; (b) Pediatric Gender Clinic, Ghent University Hospital, BELGIUM; (c) Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich, SWITZERLAND; (d) Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 37 | de Graaf, N. M., Manjra, II, Hames, A., & Zitz, C. (2019). Thinking about ethnicity and gender diversity in children and young people. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 24(2), 291–303. | 2019 | UK Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock, London |

2 Referrals only–no GD clinical verification |

Black and minority ethnic groups were underrepresented. |

| 38 | De Pedro, K. T., Gilreath, T. D., Jackson, C., & Esqueda, M. C. (2017). Substance Use Among Transgender Students in California Public Middle and High Schools. The Journal of school health, 87(5), 303–309. | 2017 | US 2013–2015 California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS) |

2 Survey. Self-identified as transgender. |

Transgender youth at increased risk for substance misuse. |

| 39 | De Vries, A. L. C., Noens, I. L. J., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. A., & Doreleijers, T. A. (2010). Autism spectrum disorders in gender dysphoric children and adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(8), 930–936. | 2010 | NETHERLANDS VU Medical Center, Amsterdam |

2 Not all participants diagnosed |

Indication of association between GID and ASD |

| 40 | de Vries, A. L., Doreleijers, T. A., Steensma, T. D., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2011). Psychiatric comorbidity in gender dysphoric adolescents. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 52(11), 1195–1202. | 2011 | NETHERLANDS VU Medical Center, Amsterdam |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 41 | De Vries, A. L. C., McGuire, J. K., Steensma, T. D., Wagenaar, E. C. F., Doreleijers, T. A. H., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2014). Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics, 134(4), 696–704. | 2014 | NETHERLANDS VU Medical Center, Amsterdam |

0 | Included in paper 1 (epidemiology) |

| 42 | de Vries, A. L. C., Steensma, T. D., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., VanderLaan, D. P., & Zucker, K. J. (2016). Poor peer relations predict parent- and self-reported behavioral and emotional problems of adolescents with gender dysphoria: a cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(6), 579–588. | 2016 | NETHERLANDS VU Medical Center, Amsterdam |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 43 | Delahunt, J. W., Denison, H. J., Sim, D. A., Bullock, J. J., & Krebs, J. D. (2018). Increasing rates of people identifying as transgender presenting to Endocrine Services in the Wellington region. New Zealand Medical Journal, 131(1468), 33–42. | 2018 | NEW ZEALAND Wellington Endocrine Service for Capital & Coast District Health Board |

1 No separate data on adolescents (includes ≥18 yrs) |

Observed increase in referrals for people under 30, also increase in requests for female to male transition. |

| 44 | Drummond, K. D., Bradley, S. J., Peterson-Badali, M., VanderLaan, D. P., & Zucker, K. J. (2018). Behavior Problems and Psychiatric Diagnoses in Girls with Gender Identity Disorder: A Follow-Up Study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(2), 172–187. | 2018 | CANADA Gender Identity Service, Center for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto |

1, 6 Included some DSD; No separate data on adolescents |

12% (n = 3) of those referred in childhood showed persistent GID in adolescence / adulthood. Some indication of psychiatric vulnerability at follow-up, but a lot of variability. |

| 45 | Drummond, K. D., Bradley, S. J., Peterson-Badali, M., & Zucker, K. J. (2008). A follow-up study of girls with gender identity disorder. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 34–45. | 2008 | CANADA Gender Identity Service, Center for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto |

1 Follow-up took place from age 17; small n under 18 (and no distinct data reported) |

As above |

| 46 | Durwood, L., McLaughlin, K. A., & Olson, K. R. (2017). Mental health and self-worth in socially transitioned transgender youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(2), 116–123. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2016.10.016 | 2017 | NORTH AMERICA Multisite survey–TransYouth Project |

2 Survey data. Participants self-identify as transgender. |

Socially transitioned young people had MH no worse than others their age |

| 47 | Edwards-Leeper, L., Feldman, H. A., Lash, B. R., Shumer, D. E., & Tishelman, A. C. (2017). Psychological profile of the first sample of transgender youth presenting for medical intervention in a US pediatric gender center. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(3), 374–382. doi:10.1037/sgd0000239 | 2017 | USA The Gender Management Service (GeMS) program at Boston Children’s Hospital |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 48 | Feder, S., Isserlin, L., Seale, E., Hammond, N., & Norris, M. L. (2017). Exploring the association between eating disorders and gender dysphoria in youth. Eating Disorders, 25(4), 310–317. | 2017 | CANADA Gender Diversity Clinic at a Canadian tertiary pediatric care hospital in Ottawa, Ontario |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 49 | Fisher, A. D., Ristori, J., Castellini, G., Sensi, C., Cassioli, E., Prunas, A.,… Maggi, M. (2017). Psychological characteristics of Italian gender dysphoric adolescents: a case-control study. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 40(9), 953–965. | 2017 | ITALY The Sexual Medicine and Andrology Unit of the University of Florence and the Gender Clinics of Rome, Milan, and Naples University Hospitals |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 50 | Getahun, D., Nash, R., Flanders, W. D., Baird, T. C., Becerra-Culqui, T. A., Cromwell, L.,… Goodman, M. (2018). Cross-sex Hormones and Acute Cardiovascular Events in Transgender Persons: A Cohort Study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(4), 205–213. doi:10.7326/M17-2785 | 2018 | USA Kaiser Permanente sites in Georgia, northern California, southern California |

1 Adults only |

Indication of increased risk of cardiovascular events in transfeminine participants. |

| 51 | Handler, T., Hojilla, J. C., Varghese, R., Wellenstein, W., Satre, D. D., & Zaritsky, E. (2019). Trends in Referrals to a Pediatric Transgender Clinic. Pediatrics, 144(5), 11. | 2019 | USA Kaiser Permanente Northern California health system |

2 No clinical verification of GD / GID. |

Observed increase in referrals in recent years. Large proportion identify as transmasculine. Treatment needs varied by age group. |

| 52 | Hannema, S. E., Schagen, S. E. E., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Delemarre-Van De Waal, H. A. (2017). Efficacy and safety of pubertal induction using 17beta-estradiol in transgirls. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 102(7), 2356–2363. | 2017 | NETHERLANDS Centre of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria (CEGD), Amsterdam |

1 No separate data on adolescents (includes ≥18 yrs) |

Estradiol effective for pubertal induction in NM. |

| 53 | Heard, J., Morris, A., Kirouac, N., Ducharme, J., Trepel, S., & Wicklow, B. (2018). Gender dysphoria assessment and action for youth: Review of health care services and experiences of trans youth in Manitoba. Paediatrics & Child Health (1205–7088), 23(3), 179–184. doi:10.1093/pch/pxx156 | 2018 | CANADA Manitoba Gender Dysphoria Assessment and Action for Youth (GDAAY) program |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 54 | Holt, V., Skagerberg, E., & Dunsford, M. (2016). Young people with features of gender dysphoria: Demographics and associated difficulties. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 21(1), 108–118. | 2016 | UK Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock & Portman, London |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 55 | Hughes, S. K., VanderLaan, D. P., Blanchard, R., Wood, H., Wasserman, L., & Zucker, K. J. (2017). The Prevalence of Only-Child Status Among Children and Adolescents Referred to a Gender Identity Service Versus a Clinical Comparison Group. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(6), 586–593. | 2017 | CANADA Gender Identity Service, CYFS, Toronto |

2, 4 Mean age of all groups <12 yrs. No apparent clinical verification of GD / GID. |

Prevalence of only-child status not elevated in gender-referred children (compared to other clinical populations). |

| 56 | Janssen, A., Huang, H., & Duncan, C. (2016). Gender Variance among Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Retrospective Chart Review. Transgender Health, 1(1), 63–68. | 2016 | USA New York University Child Study Center |

2 Derived from clinical ASD sample. No clinical verification of GD / GID. |

Participants with ASD diagnosis more likely to report gender variance on CBCL then CBCL normative sample. |

| 57 | Jarin, J., Pine-Twaddell, E., Trotman, G., Stevens, J., Conard, L. A., Tefera, E., & Gomez-Lobo, V. (2017). Cross-sex hormones and metabolic parameters in adolescents with gender dysphoria. Pediatrics, 139 (5) (no pagination)(e20163173). | 2017 | USA Multi-site. MedStar Washington Hospital Center and Children’s National Medical Center (both, Washington, DC). University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Ohio. |

1 No separate data on adolescents (includes ≥18 yrs) |

Testosterone use associated with increased hemoglobin and hematocrit, increased BMI, and lowered high-density lipoprotein levels. No significant change in those taking estrogen. |

| 58 | Kaltiala, R., Bergman, H., Carmichael, P., de Graaf, N. M., Egebjerg Rischel, K., Frisen, L.,… Waehre, A. (2020). Time trends in referrals to child and adolescent gender identity services: a study in four Nordic countries and in the UK. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 74(1), 40–44. | 2020 | DENMARK, FINLAND, NORWAY, SWEDEN, & the UK | 2 No clinical verification of GD / GID. |

Comprehensive overview of referrals in 5 countries. Same pattern of increase, especially in NF, as in included papers. |

| 59 | Kaltiala, R., Heino, E., Tyolajarvi, M., & Suomalainen, L. (2020). Adolescent development and psychosocial functioning after starting cross-sex hormones for gender dysphoria. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 74(3), 213–219. | 2020 | FINLAND Tampere University Hospital, Department of Adolescent Psychiatry |

1 Mean age at assessment 18.1 |

MH problems persisted during treatment–concluded that GD treatment not enough to address MH problems. |

| 60 | Kaltiala-Heino, R., Sumia, M., Tyolajarvi, M., & Lindberg, N. (2015). Two years of gender identity service for minors: Overrepresentation of natal girls with severe problems in adolescent development. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9 (1) (no pagination)(9). | 2015 | FINLAND Tampere University Hospital, Department of Adolescent Psychiatry |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 61 | Kaltiala-Heino, R., Tyolajarvi, M., & Lindberg, N. (2019). Sexual experiences of clinically referred adolescents with features of gender dysphoria. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 365–378. | 2019 | FINLAND Tampere University Hospital, Department of Adolescent Psychiatry |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 62 | Kaltiala-Heino, R., Tyolajarvi, M., & Lindberg, N. (2019). Gender dysphoria in adolescent population: A 5-year replication study. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 379–387. | 2019 | FINLAND School survey in Tampere |

2 Survey data. No clinical verification of GD / GID. |

Apparent increase in likely clinically-significant GD in adolescent population (2013–2017). |

| 63 | Katz-Wise, S. L., Ehrensaft, D., Vetters, R., Forcier, M., & Austin, S. B. (2018). Family Functioning and Mental Health of Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Youth in the Trans Teen and Family Narratives Project. Journal of sex research, 55(4–5), 582–590. | 2018 | USA New England region–survey from range of services / organisations |

2 Survey data. No clinical verification of GD / GID. |

MH concerns reported. Better family functioning (from young person’s persepective) associated with better MH outcomes. |

| 64 | Khatchadourian, K., Amed, S., & Metzger, D. L. (2014). Clinical management of youth with gender dysphoria in Vancouver. Journal of Pediatrics, 164(4), 906–911. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.068 | 2014 | CANADA British Columbia Children’s Hospital Transgender Program, Vancouver |

1 No separate data on adolescents (includes ≥18 yrs) |

Median age at initiation of testosterone NF 17.3 years (range 13.7–19.8 years); median age at initiation of estrogen in NM 17.9 years (range 13.3–22.3 years). Intervnention appopriate in selected individuals with relevant clinical support. |

| 65 | Klein, D. A., Roberts, T. A., Adirim, T. A., Landis, C. A., Susi, A., Schvey, N. A., & Hisle-Gorman, E. (2019). Transgender Children and Adolescents Receiving Care in the US Military Health Care System. JAMA Pediatrics. | 2019 | USA Military Health System Data Repository |

1 No separate data on adolescents (includes ≥18 yrs) |

Increase in service use 2010–2017. Prescriptions increased with higher parental rank. |

| 66 | Kolbuck, V. D., Muldoon, A. L., Rychlik, K., Hidalgo, M. A., & Chen, D. (2019). Psychological functioning, parenting stress, and parental support among clinic-referred prepubertal gender-expansive children. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 7(3), 254–266. doi:10.1037/cpp0000293 | 2019 | USA Division of Adolescent Medicine, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago* |

4 Sample <12 yrs. |

Association between GD symptoms in ADHD (hyperactive-impulsive) and CD where parenting stress high. |

| 67 | Kuper, L. E., Lindley, L., & Lopez, X. (2019). Exploring the gender development histories of children and adolescents presenting for gender affirming medical care. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 7(3), 217–228. | 2019 | USA Gender Education and Care Interdisciplinary Support program, Texas |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 68 | Kuper, L. E., Mathews, S., & Lau, M. (2019). Baseline Mental Health and Psychosocial Functioning of Transgender Adolescents Seeking Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP., 03. | 2019 | USA Gender Education and Care Interdisciplinary Support program, Texas |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 69 | Lawlis, S. M., Donkin, H. R., Bates, J. R., Britto, M. T., & Conard, L. A. E. (2017). Health Concerns of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youth and Their Parents Upon Presentation to a Transgender Clinic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(5), 642–648. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.025 | 2017 | USA ‘a transgender clinic at a large tertiary pediatric hospital in the Midwest.’ Oklahoma University Children’s Hospital* |

2 |

66.1% attending for first appointment NF |

| 70 | Levitan, N., Barkmann, C., Richter-Appelt, H., Schulte-Markwort, M., & Becker-Hebly, I. (2019). Risk factors for psychological functioning in German adolescents with gender dysphoria: poor peer relations and general family functioning. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. | 2019 | GERMANY Hamburg Gender Identity Service for Children and Adolescents |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 71 | Lobato, M. I., Koff, W. J., Schestatsky, S. S., Chaves, C. P. V., Petry, A., Crestana, T.,… Henriques, A. A. (2007). Clinical characteristics, psychiatric comorbidities and sociodemographic profile of transsexual patients from an outpatient clinic in Brazil. International Journal of Transgenderism, 10(2), 69–77. doi:10.1080/15532730802175148 | 2007 | BRAZIL Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre |

1 | 42.7% had at least one psychiatric comorbidity |

| 72 | Lothstein, L. M. (1980). The adolescent gender dysphoric patient: An approach to treatment and management. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 5(1), 93–109. | 1980 | USA Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) Gender Identity Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio |

1, 3 | Case series from over 40 years ago |

| 73 | Lynch, M. M., Khandheria, M. M., & Meyer, W. J., III. (2015). Retrospective study of the management of childhood and adolescent gender identity disorder using medroxyprogesterone acetate. International Journal of Transgenderism, 16(4), 201–208. doi:10.1080/15532739.2015.1080649 | 2015 | USA Gender Identity Clinic, University of Texas Medical Branch |

3 Case series |

Medroxyprogesterone Acetate found to be effective and low-cost oral alternative to injectable or implant GnRH analogues. Response to treatment and compliance were favourable. |

| 74 | Mahfouda, S., Panos, C., Whitehouse, A. J. O., Thomas, C. S., Maybery, M., Strauss, P.,… Lin, A. (2019). Mental Health Correlates of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Gender Diverse Young People: Evidence from a Specialised Child and Adolescent Gender Clinic in Australia. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(10), 20. | 2019 | AUSTRALIA Gender Diversity Service (GDS), Perth Children’s Hospital. GENTLE cohort study |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 75 | Manners, P. J. (2009). Gender identity disorder in adolescence: A review of the literature. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 14(2), 62–68. | 2009 | UK (review) Salomons Clinical Psychology Training Program, Canterbury Christ Church University |

5 Review |

Review now out of date |

| 76 | Matthews, T., Holt, V., Sahin, S., Taylor, A., & Griksaitis, D. (2019). Gender Dysphoria in looked-after and adopted young people in a gender identity development service. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 24(1), 112–128. doi:10.1177/1359104518791657 | 2019 | UK Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock & Portman, London |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 77 | May, T., Pang, K., & Williams, K. J. (2017). Gender variance in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder from the National Database for Autism Research. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(1), 7–15. doi:10.1080/15532739.2016.1241976 | 2017 | USA National Database for Autism Research |

2 Derived from clinical ASD sample. No clinical verification of GD / GID. |

Higher prevalence of gender variance in ASD sample compared to non-referred samples (but similar to other clinical samples). |

| 78 | Millington, K., Liu, E., & Chan, Y. M. (2019). The utility of potassium monitoring in gender-diverse adolescents taking spironolactone. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 3(5), 1031–1038. | 2019 | USA Gender Management Service Program, Boston Children’s Hospital |

1 Sample likely to include those ≥18 yrs |

Hyperkalemia in patients taking spironolactone for gender transition rare. Routine electrolyte monitoring may be unnecessary. |

| 79 | Millington, K., Schulmeister, C., Finlayson, C., Grabert, R., Olson-Kennedy, J., Garofalo, R.,… Chan, Y. M. (2020). Physiological and Metabolic Characteristics of a Cohort of Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 376–383. | 2020 | USA Children’s Hospital Los Angeles/University of Southern California, Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago/Northwestern University, and the Benioff Children’s Hospital/University of California San Francisco |

4 Sample 1 aged 8–14 (so mostly under 12s); sample 2 aged 12–20 (so included over 18s). |

Description of baseline metabolic characteristics–will be useful to see cohorts followed up. |

| 80 | Moyer, D. N., Connelly, K. J., & Holley, A. L. (2019). Using the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 to screen for acute distress in transgender youth: findings from a pediatric endocrinology clinic. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism, 32(1), 71–74. | 2019 | USA ’a pediatric endocrinology clinic’, Portland, Oregon |

0 | Included in papers 1 (epidemiology) & 2 (mental health) |

| 81 | Munck, E. T. (2000). A retrospective study of adolescents visiting a Danish clinic for sexual disorders. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 12(2–3), 215–222. doi:10.1515/IJAMH.2000.12.2–3.215 | 2000 | DENMARK Sexological Clinic, Copenhagen University Hospital |

1 Mean age over 20 years |

Description of cohort 1686–1995. Up to age 16, majority were NM. From age 17, majority were NF. |

| 82 | Nahata, L., Tishelman, A. C., Caltabellotta, N. M., & Quinn, G. P. (2017). Low Fertility Preservation Utilization Among Transgender Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(1), 40–44. | 2017 | USA Division of Endocrinology, Department of Pediatrics, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio* |

5 Same sample already described (Nahata et al., 2017) |

See epidemiological data in main review (Nahata et al., 2017). |

| 83 | Neyman, A., Fuqua, J. S., & Eugster, E. A. (2019). Bicalutamide as an Androgen Blocker With Secondary Effect of Promoting Feminization in Male-to-Female Transgender Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 544–546. | 2019 | USA Pediatric Endocrine Clinic, Riley Hospital for Children, Indiana |

1, 3 Where adolescent data separated, includes very small sample (case series) |

Evidence that bicalutamide may be viable alternative to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues in NM ready to transition |

| 84 | O’Bryan, J., Scribani, M., Leon, K., Tallman, N., Wolf-Gould, C., Wolf-Gould, C., & Gadomski, A. (2020). Health-related quality of life among transgender and gender expansive youth at a rural gender wellness clinic. Quality of Life Research, 29(6), 1597–1607. | 2020 | USA The Gender Wellness Center (GWC) of the Bassett Health- care Network, New York |

1 Upper age limit 25 yrs. No meaningful separate data on those under 18 yrs. |

Poor MH reported (relative to general population). Long term follow-up needed. |

| 85 | Olson, J., Schrager, S. M., Belzer, M., Simons, L. K., & Clark, L. F. (2015). Baseline Physiologic and Psychosocial Characteristics of Transgender Youth Seeking Care for Gender Dysphoria. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(4), 374–380. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.027 | 2015 | USA Center for Transyouth Health and Development, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, California |

1 | Awareness of gender incongruity from young age (mean 8.3 yrs). Physiological characteristics within normal ranges. 35% experiencing depression; 51% contemplated suicide; 30% attempted suicide. |

| 86 | Olson-Kennedy, J., Okonta, V., Clark, L. F., & Belzer, M. (2018). Physiologic Response to Gender-Affirming Hormones Among Transgender Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(4), 397–401. | 2018 | USA Center for Transyouth Health and Development, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, California |

1 | Use of gender affirming hormones not associated with clinically significant changes in metabolic parameters. May not need to frequently monitor transgender adolescents. |

| 87 | Olson-Kennedy, J., Warus, J., Okonta, V., Belzer, M., & Clark, L. F. (2018). Chest Reconstruction and Chest Dysphoria in Transmasculine Minors and Young Adults: Comparisons of Nonsurgical and Postsurgical Cohorts. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(5), 431–436. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5440 | 2018 | USA Center for Transyouth Health and Development, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, California |

1 | Mean age at chest surgery 17.5 (2.4) years. 49% younger than 18 years. All postsurgical participants (n = 68) felt surgery had been a good decision. Loss of nipple sensation most common side-effect. |