Significance

To survive during heat shock, cells have a mechanism to induce the synthesis of Hsps and to restore normal levels when the stress subsides. The molecular mechanisms of the heat shock response in Escherichia coli have been extensively studied over the years. The master heat shock transcriptional regulator, σ32, which is normally at low levels due to chaperone-mediated degradation, is increased upon heat shock. Our study has identified a chaperone, IbpA, that regulates the level of σ32 by suppressing its expression at a translational level, thereby contributing to the heat shock response regulation.

Keywords: small heat shock protein, sHsp, IbpA, rpoH, heat shock response

Abstract

Small heat shock proteins (sHsps) act as ATP-independent chaperones that prevent irreversible aggregate formation by sequestering denatured proteins. IbpA, an Escherichia coli sHsp, functions not only as a chaperone but also as a suppressor of its own expression through posttranscriptional regulation, contributing to negative feedback regulation. IbpA also regulates the expression of its paralog, IbpB, in a similar manner, but the extent to which IbpA regulates other protein expressions is unclear. We have identified that IbpA down-regulates the expression of many Hsps by repressing the translation of the heat shock transcription factor σ32. The IbpA regulation not only controls the σ32 level but also contributes to the shutoff of the heat shock response. These results revealed an unexplored role of IbpA to regulate heat shock response at a translational level, which adds an alternative layer for tightly controlled and rapid expression of σ32 on demand.

Heat stress responses are vital to prevent heat stress–induced protein homeostasis (proteostasis) failure. Coping with stress-induced protein denaturation, Hsps, including chaperones and proteases, act through multiple quality control mechanisms (1, 2). Refolding and degradation of denatured proteins caused by stresses are two primary strategies to prevent the accumulation of protein aggregates. Sequestration of denatured proteins is a third strategy, to keep misfolded proteins in a state that is easy to restore or degrade after stresses (1, 3). Hsps are expressed in response to heat stress and are typically regulated at the transcriptional level in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (1).

Heat stress responses are primarily regulated by changes in the levels or activity of transcriptional regulators (4, 5). In Escherichia coli, the heat shock transcription factor σ32 regulates the expression of approximately 100 genes (6). Its abundance is immediately increased under heat stress, reaching a maximum at 5 min, and gradually decreases thereafter (4, 7, 8). The cells then enter a shutoff phase where σ32 is suppressed in both abundance and activity (4, 7, 8). Previous studies on σ32 have revealed that its regulation occurs at multiple levels, including transcription, translation, stability, and activity. In particular, posttranscriptional regulations play a significant role in the σ32 stress response (4, 7–11).

Chaperone binding to σ32 regulates its stability and activity (4, 12, 13). Two major cytoplasmic chaperone systems, DnaK-DnaJ and GroEL-GroES, play various roles, including assisting in the folding of nascent polypeptide chains and maintenance of folded and denatured proteins. Chaperone binding to σ32 inhibits its activity and assists in its degradation by the inner membrane protease FtsH (2, 4, 7, 13–15). The membrane localization of σ32 via signal-recognition particle (SRP) and its receptor is also essential for the σ32 degradation by chaperones and FtsH (16, 17). The σ32 recruitment by the SRP receptor is followed by the chaperone-dependent degradation. The σ32 I54N mutant, a hyperactive mutant, which disrupts the interaction between σ32 and SRP, is not inactivated by chaperones and is resistant to the degradation by FtsH (13, 16–18). The abundance of σ32 is usually suppressed to less than 50 molecules in the cell, due to a rapid degradation mediated by chaperones and proteases (8). However, during heat stress, stress-induced chaperone recruitment to denatured proteins allows for a transient increase in the abundance of σ32 (8). The subsequent transition to the shutoff phase is thought to depend on the accelerated degradation of σ32 mediated by the excess chaperones (19, 20). However, it has been reported that the transition to the shutoff phase is also normal in E. coli mutant strains including an ftsH-deleted strain (21, 22). Additionally, even E. coli with the hyperactive σ32 I54N mutant exhibits a reduction in the level of heat shock response within 15 min of the onset of heat shock (18). These observations suggest that the degradation of σ32 alone does not fully explain the shutoff mechanism.

The translation of rpoH, which encodes σ32, is regulated by thermoresponsive mRNA secondary structures called RNA thermometers (RNATs) (4, 23, 24). At normal or low temperatures, the RNATs adopt complex structures, including a region encompassing the Shine–Dalgarno (SD) sequence in the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR), close to the translational initiation sites. However, heat fluctuations cause the melting of the structures that mask the SD sequence, enabling the translation of σ32 (24). The RNAT of rpoH consists of the 5′ UTR and part of the open reading frame (ORF), and it is known that the RNA secondary structure masking the start codon opens in a temperature-dependent manner (4, 23–25). RNATs have been extensively studied in rpoH and small heat shock proteins (sHsps) (13, 24). The RNATs in sHsps exhibit conserved shapes in α- and γ-proteobacteria (24, 26, 27). Recently, the RNAT shape of IbpA, an E. coli sHsp, has been demonstrated to be a crucial factor in the negative-feedback regulation of IbpA at the translational level (28).

sHsps are a group of low subunit molecular weight (12 to 43 kD) ATP-independent chaperones that serve as the first line of defense against protein aggregation stress in organisms of all kingdoms (3, 29, 30). sHsps have two chaperone functions: preventing the irreversible aggregation of denatured client proteins by binding to them, and aiding in their folding through other chaperones such as DnaK/DnaJ (3, 29, 30). Under normal conditions, sHsps form dynamic oligomers with no fixed number of subunits. The oligomeric states are thought to restrict the client-binding region inside the oligomers and to maintain the sHsps in a storage state. The IX(I/V) motif in the C-terminal region of sHsps is responsible for the formation of oligomers (3, 29, 30).

IbpA and IbpB, sHsps of E. coli, exhibit a high degree of homology and form heterooligomers (31, 32). They function as sHsps by sequestering denatured proteins and facilitating their refolding with the aid of other chaperones. While IbpA has a specialized role in substrate binding to prevent irreversible protein aggregation, its substrate release efficiency for transfer to other chaperones is lower than that of IbpB (31–33).

Recently, we found that IbpA serves not only as a chaperone but also as a regulator of gene expression. Specifically, IbpA represses its own translation, as well as that of IbpB, by binding to the corresponding mRNAs (28). Under conditions of increased intracellular protein aggregation, IbpA is recruited for sequestration, which releases the repression of translation. Although IbpA and IbpB are highly homologous, IbpB lacks the self-regulation activity (28). This IbpA-mediated mechanism represents a negative feedback response that is partly assisted by RNA degradation by RNase (28). An oligomer-forming motif [IX(I/V)] of IbpA is critical for this regulation and for mRNA binding. The RNA secondary structure of the 5′ UTR is also essential for regulation, as mutation of the stem-loop structure in the 5′ UTR of the ibpA mRNA abolishes the IbpA-mediated expression regulation (28). Furthermore, IbpA also regulates the expression of IbpB through the RNAT structure of the 5′ UTR of the ibpB mRNA, which is not identical to that of the ibpA mRNA (26, 27), suggests the possibility that IbpA may recognize other mRNAs to regulate gene expression.

Here, we searched for regulatory targets of IbpA with similar molecular mechanisms. A proteome analysis of E. coli cells overexpressing IbpA revealed that the abundance of many Hsps was reduced at the transcriptional level, not the translational level. We, therefore, focused on σ32, the master transcriptional regulator of Hsps in E. coli. The analysis showed that σ32 is a target for the translational regulation of IbpA. We found that the IbpA-mediated inhibition of the rpoH translation affected changes in the σ32 level during the shutoff phase, although it had no effect on the transient increase in the σ32 level upon heat shock. The expression level of IbpA slightly influenced the growth of cells after the recovery from heat stress. Our findings suggest a model in which the σ32-mediated shutoff is regulated by IbpA at a translational level. Our study focusing on IbpA has illuminated the involvement of this previously unrecognized factor in the established molecular mechanism of the heat shock response in E. coli.

Results

Overexpression of IbpA Leads to Downregulation of Multiple Heat Shock Proteins.

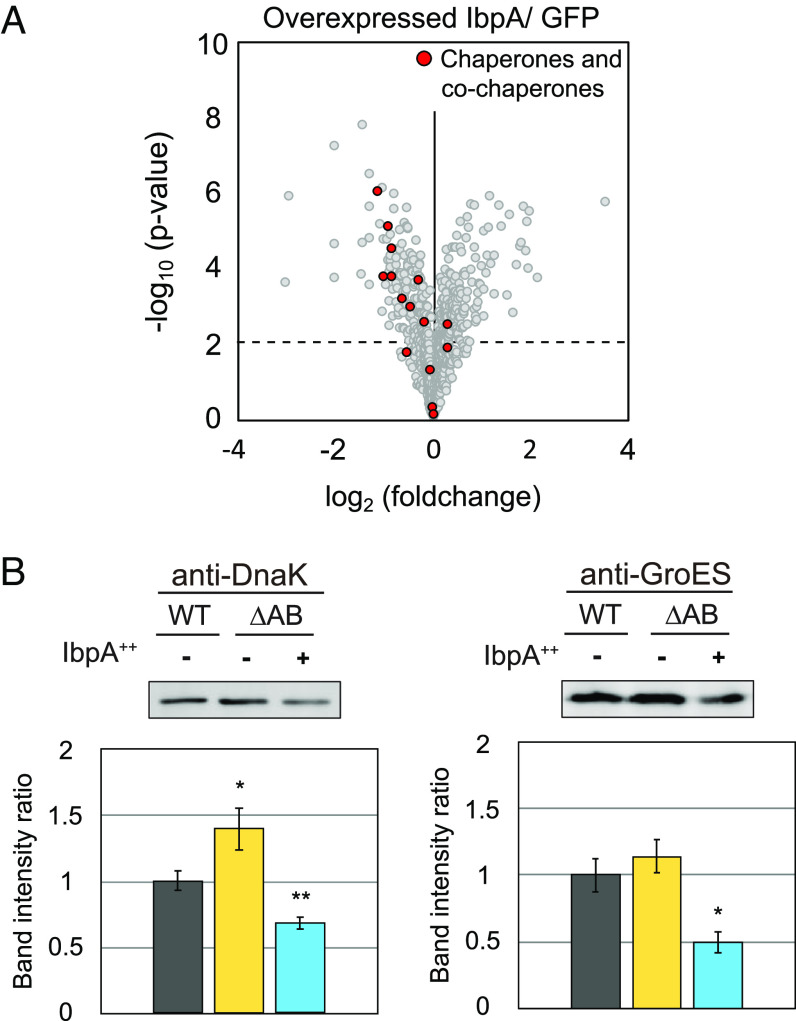

IbpA regulates the expression of itself and its paralog, ibpB, at the posttranscriptional level (28). The stem loops present in the 5′ UTR of the mRNA of ibpA or ibpB constitute a key regulatory element. While secondary structures with multiple stem-loops are common in the 5′ UTRs of ibpA and ibpB, their sequences and structures are not identical (26, 27). Therefore, we hypothesized that, apart from self-regulation, IbpA may also influence the expression of other proteins in E. coli. To identify potential targets of IbpA-mediated regulation, we conducted a mass spectrometry (MS)–based quantitative proteomics analysis to identify proteins, whose expression is altered in E. coli upon IbpA overexpression. We compared the proteomes of cells overexpressing IbpA and those overexpressing GFP as a control and found that 41 and 40 proteins were specifically increased (>1.67-fold) and decreased (<0.6-fold), respectively, upon IbpA overexpression (Fig. 1A and Dataset S1). Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that the most significantly altered and statistically significant category in IbpA-overexpressed cells was the group of proteins associated with chaperones. (red circles in Fig. 1A, SI Appendix, Fig. S1A, and Dataset S2). The proteome of cells overexpressing a nonfunctional IbpA mutant, IbpAAEA, which is defective in both oligomer formation and self-suppression activity, did not show the enrichment of chaperone-related proteins among the decreased proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C and Dataset S2), further suggesting that the reduction of chaperones was specific to functional IbpA.

Fig. 1.

IbpA overexpression down-regulates a multitude of heat shock proteins. (A) A volcano plot depicting the degree of protein expression ratio between IbpA and GFP overexpression in E. coli wild-type strain. Each dot in the plot represents the fold change and P-value of an individual protein, identified by comparative proteomics analysis. The dashed line represents a P-value threshold of 0.01. Red dots indicate proteins belong to the “chaperone binding” and “unfolded protein binding” categories in GO term enrichment analysis. (B) Western blotting of endogenous DnaK and GroES in E. coli wild-type strain (WT) or the ibpAB operon–deleted strain (ΔAB). IbpA++E. coli ΔAB cells overexpressing IbpA. Relative band intensities of three biological replicates are shown below. The value in the E. coli wild type was set to 1. Error bars represent the SD; The statistical significance of differences was assessed using Student's t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

To validate the decrease in chaperones observed in the MS data, we examined the expression levels of representative chaperones, DnaK and GroES by western blotting. In this experiment, we overexpressed IbpA in an ibpA-ibpB deletion strain (ΔibpAB) to better highlight the effect of IbpA abundance; We postulated that depletion of IbpA could lead to an increase in chaperones. After the confirmation of ~ninefold overexpression of IbpA (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), we found that the expression level of DnaK and GroES increased in the ΔibpAB strain and decreased in cells overexpressing IbpA (Fig. 1B), supporting our postulation.

IbpA Represses the Expression of Hsps at the Transcriptional Level.

Next, to investigate whether IbpA mediates the reduction of chaperones by translation suppression via the 5′ UTRs, we constructed gfp reporters harboring 5′ UTRs of dnaK and groES and examined their expression levels in response to IbpA. We used an arabinose-inducible promoter (PBAD) in the plasmids to keep the mRNA levels almost identical. The abundance of IbpA did not significantly affect the expression of both reporters (dnaK: Fig. 2A, groES: SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). To directly assess the IbpA effect on the dnaK and groES translation, we used an E. coli reconstituted cell-free translation system, PURE system, that only includes factors essential for translation (34). We compared the dnaK and groES mRNA translation with or without purified IbpA and found that IbpA had no effect on the translation of the dnaK and groES mRNAs (dnaK: Fig. 2B, groES: SI Appendix, Fig. S3B).

Fig. 2.

IbpA suppresses the expression of DnaK at a transcriptional level. (A) Western blotting of GFP expressed from a gfp gene harboring the dnaK 5′ UTR in E. coli wild-type (WT) or the ibpAB operon–deleted strain (ΔAB). IbpA++E. coli ΔAB cells overexpressing IbpA. Relative band intensities of three biological replicates are shown below. The value in the E. coli wild type was set to 1. (B) Cell-free translation of the gfp reporter in the absence (−) or the presence (+) of purified IbpA using a reconstituted protein synthesis system (PURE system). The value without IbpA was set to 1. (C) Quantification of endogenous dnaK mRNA levels by qRT-PCR in wild-type cells (Left), ΔAB cells (Middle), and ΔAB cells overexpressing IbpA (Right). The value in the E. coli wild type was set to 1. (D) Western blotting of GFP expressed under the control of the endogenous dnaK promoter in E. coli cells. Relative band intensities of three biological replicates are shown below. The value in the E. coli wild type was set to 1. (E) Western blotting (Left) and the relative band intensities (Right) of GFP expressed by the endogenous dnaK promoter in E. coli cells with (red) or without (gray) heat shock (HS). The values without heat shock were set to 1. Statistical analysis: Error bars represent SD; n = 3 biological replicates. The statistical significance of differences was assessed using Student's t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

We then hypothesized that IbpA may regulate the transcription of dnaK and groES, and quantified their endogenous mRNA levels in E. coli using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The results showed that IbpA overexpression led to a decrease in dnaK and groES mRNA levels, while the deletion of ibpAB increased the levels of these mRNAs (dnaK: Fig. 2C, groES: SI Appendix, Fig. S3C). Furthermore, overexpression of IbpA effectively suppressed the reporter expression in plasmids harboring endogenous dnaK or groES promoters (dnaK: Fig. 2D, groES: SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). These results suggest that excessive amounts of IbpA repress the expression of DnaK and GroES at the transcriptional level.

The data obtained from the proteome and reporter assay prompted us to hypothesize that IbpA may influence the expression levels of σ32, which is the primary transcriptional regulator of Hsps. To investigate this, we examined whether heat stress could impact the expression levels of dnaK and groES in E. coli with varying amounts of IbpA. We observed a substantial increase in the expression of the GFP reporter with the endogenous dnaK or groES promoter at 42 °C in the ΔibpAB cells, similar to the wild type. In contrast, such heat stress induction was completely lost in the IbpA-overexpressing cells (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Fig. S3E).

Our findings thus far provide evidence that overexpression of IbpA suppresses the transcription of Hsps by σ32. In fact, proteome data revealed that proteins regulated by σ32 were overall decreased in cells overexpressing wild-type IbpA, but not in cells overexpressing IbpAAEA (Dataset S2), indicating that functional IbpA down-regulates σ32 at a translational level.

Expression of σ32 Is Repressed by IbpA at a Translational Level.

To determine whether the abundance of IbpA can impact the expression level of σ32 at a translational level, we examined the endogenous σ32 expression in ΔibpAB and IbpA-overexpressing cells. We observed an increase in the expression of endogenous σ32 in ΔibpAB cells and a decrease in IbpA-overexpressing cells (Fig. 3A). The drastic reduction in the σ32 level was partially due to the decreased rpoH mRNA levels in IbpA-overexpressing cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), though the degradation rates of the rpoH mRNA were consistent in all strains tested (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B), indicating that the rpoH mRNA level is also influenced by IbpA overexpression. While the rpoH mRNA level was not affected in ΔibpAB cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), the σ32 level was significantly up-regulated in these cells (Fig. 3A). We concluded that the abundance of IbpA affects the σ32 level at a translational level. To confirm this, we investigated whether the σ32 levels were dependent on the presence of the 5′ UTR of the rpoH mRNA using an arabinose promoter to keep the mRNA levels almost identical (Fig. 3 B, Left). The trend of the change in the σ32 level expressed from the reporter plasmid was the same as that of endogenous σ32 levels (Fig. 3 B, Right), while such change in the σ32 level was not observed in the translation of the reporter harboring 5′ UTR of the vector (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). The results further support the idea that the IbpA suppresses the expression of σ32 at a translational level. Finally, in the PURE system, purified IbpA suppressed the translation of the rpoH mRNA by approximately 50% in an rpoH 5′ UTR-dependent manner (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that IbpA directly suppresses the translation of the rpoH mRNA.

Fig. 3.

IbpA-mediated suppression of rpoH translation. (A) Detection of endogenous σ32 levels in wild type and ibpAB-deleted (ΔAB) cells using western blotting. IbpA++E. coli ΔAB cells overexpressing IbpA. Anti-σ32 antibody was used for the detection. Relative band intensities of three biological replicates are shown below. The value in the E. coli wild type was set to 1. (B) Quantification of the levels of rpoH mRNA (Left) and the σ32 protein fused with His-tag (Right) expressed from plasmids harboring 5′ UTRs of rpoH under the control of an arabinose promoter (PBAD) by western blotting. Anti-His tag antibody was used for the detection to distinguish plasmid-expressed σ32 from endogenous σ32. The value in the E. coli wild type was set to 1. (C) Cell-free translation of σ32 from the rpoH mRNA harboring 5′ UTRs of rpoH in the absence (−) or the presence (+) of purified IbpA using the PURE system. Cy5-labeled methionines in the translation products were detected with a fluorescence imager. The value without IbpA was set to 1. Statistical analysis: Error bars represent SD; n = 3 biological replicates. The statistical significance of differences was assessed using Student's t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

The Control of the σ32 Levels by IbpA Is Independent of the Degradation Pathway through DnaK.

Chaperone-mediated degradation of σ32 is one mechanism for regulating its abundance (4, 13) (Fig. 4A). To examine whether IbpA affects σ32 degradation, we investigated whether IbpA’s effect on σ32 is abolished in cells with deleted DnaK or the σ32 I54N mutation, which are known to inhibit the degradation pathway (2, 4, 7, 13–15, 21, 35). We evaluated the endogenous σ32 expression in an E. coli strain that deleted the dnaK-dnaJ operon (ΔdnaKJ), with or without the IbpA overexpression. Our data showed that even in the ΔdnaKJ cells, IbpA overexpression significantly suppressed σ32 expression (Fig. 4B), suggesting that IbpA-mediated σ32 suppression occurs independently of the DnaK-mediated degradation pathway. In addition, we found that DnaK/DnaJ supplementation in the IbpA-overexpressing ΔdnaKJ strain further decreased the σ32 level, indicating that the effects of IbpA and DnaK are additive. We next used the σ32 I54N mutant, which is defective in chaperone-mediated degradation and inactivation (13, 16–18). The σ32 I54N mutant expression was up-regulated by the ibpA-ibpB deletion and decreased by IbpA overexpression (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that IbpA affects the σ32 level at the translational level but not at the degradation step.

Fig. 4.

IbpA-mediated control of the σ32 level is independent of degradation via the DnaK pathway. (A) Model illustrating regulation of σ32 degradation. (B) Western blotting used to evaluate endogenous σ32 levels in the dnaK-dnaJ operon–deleted strain (ΔdnaKJ) with or without IbpA and DnaK/DnaJ expression. Normal, E. coli wild type (i.e., endogenous level of IbpA). IbpA++ E. coli wild type overexpressing IbpA from a plasmid. Δ, ΔdnaKJ strain. +, ΔdnaKJ strain complemented with DnaK/DnaJ by expression from a plasmid. Anti-σ32 antibody was used for detection. Relative band intensities of three biological replicates are shown below. The value in the ΔdnaKJ strain was set to 1. (C) Western blotting evaluating the effect of the σ32 I54N mutation using the reporter system shown in Fig. 3B. Anti-His tag antibody was used for detection. Relative band intensities of three biological replicates are shown below. The value in the E. coli wild type was set to 1. Statistical analysis: Error bars represent SD. The statistical significance of differences was assessed using Student's t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

IbpA Contributes to the Shutoff of σ32 during the Heat Shock Response.

It is widely acknowledged that σ32 levels experience a temporary increase during heat shock followed by a decrease, a phase referred to as “shutoff”, which is critical for the recovery to normal conditions (4, 7, 8). We tested whether the IbpA-mediated regulation of σ32 affects the shutoff phase. In order to determine the level shift of σ32 accompanied by heat shock, we assessed the abundance of endogenous σ32, which was normalized by that of FtsZ, a protein expressed constitutively. In wild-type E. coli cells, the σ32 level was at its maximum 5 min after the onset of heat stress and subsequently decreased to a normal level 10 min later (Fig. 5A), consistent with previous studies (4, 8). Upon exposure to heat stress in the ΔibpAB strain, the σ32 level increased similarly to the wild-type strain. However, in contrast to the wild type, the increased level of σ32 continued even at 10 min and was only shutoff to the normal level after 30 min (Fig. 5A). Unlike the wild-type and the ΔibpAB strains, overexpression of IbpA significantly suppressed σ32 expression and heat stress–response of σ32 (Fig. 5A), which was also the case even when IbpB was overexpressed together with IbpA in ΔibpAB cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A).

Fig. 5.

IbpA contributes to the shutoff of σ32 during heat shock response. (A) Evaluation of the σ32 during heat shock response. (Top) Western blotting of endogenous σ32 and FtsZ in wild-type (WT), ibpAB-deleted (ΔAB), and ΔAB cells overexpressing IbpA (IbpA++) cells. Anti-σ32 and anti-FtsZ antibodies were used to detect σ32 and FtsZ, respectively. FtsZ, a constitutively expressed protein, was used to normalize the band intensity of σ32. HS (min): the minutes from the start of heat shock. (Bottom) Quantification of σ32 levels normalized by FtsZ levels. Error bars represent SD; n = 3 biological replicates. (B) The growth curve of E. coli after recovery from heat shock. The cells were grown at 30 or 42 °C for 2 h and then diluted to allow growth at 37 °C. WT: wild-type cells; ΔABibpAB-deleted strain; IbpA++: ΔAB cells overexpressing IbpA. Error bars represent SD; n = 3 biological replicates.

Along with the change in the amount of σ32 in E. coli with varying IbpA levels, the amount of Hsps was also affected. For example, the amounts of GroES increased or decreased in the E. coli with the depletion or the overexpression of IbpA, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). These findings demonstrate that the overexpression or loss of IbpA perturbs the normal heat shock response.

Given that the shutoff phase is associated with the recovery from heat stress, we next examined the effect of IbpA on cell growth after exposure to heat shock at 42 °C for 2 h. The cell growth rate during recovery after stress was slightly, but statistically significantly, impaired in the ΔibpAB strain compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 5B). In the IbpA-overexpression strain, which exhibited slower growth than the wild-type strain even at 37 °C as previously shown (28), the recovery after stress was extremely poor (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

IbpA, sHsp in E. coli, has been identified as a chaperone that sequesters aggregation proteins by coaggregation during stress. Recently, it has also been shown to act as a mediator for self-regulation at the posttranscriptional level (28). This study provides compelling evidence that IbpA represses the translation of rpoH mRNA, which is a target for IbpA-mediated regulation in trans, since previously known targets were limited to ibpA and ibpB mRNAs. The ability of IbpA to regulate other ORF mRNAs suggests that its effect on σ32 could influence the heat shock response, in addition to the FtsH-mediated degradation assisted by chaperones like DnaK and GroEL, which are already well established.

We have found that the abundance of oligomeric IbpA influences the level of σ32 in a manner that is dependent on the rpoH 5′ UTR. Additionally, we reconstituted the suppression of translation by IbpA in the PURE system. These findings strongly suggest that the fundamental mechanism of translation suppression by IbpA on rpoH is comparable to that on ibpA or ibpB. Since the translation of ibpA and rpoH mRNAs is governed by thermoresponsive mRNA secondary structures (RNATs), IbpA oligomers could attach to the 5′ UTR of rpoH mRNA to repress translation under normal conditions. We previously proposed a titration model for the self-regulation of IbpA during heat stress. In this model, IbpA-mediated self-repression of translation via mRNA binding is abolished by the recruitment of IbpA to protein aggregates (28). The role of IbpA as a regulator of its own expression via sensing of protein aggregation may be relevant to the control of σ32. This mechanism is reasonable given the function of sHsps as the first line of defense against aggregation stress.

Then, we propose a model for the regulatory role of IbpA in the σ32 response (Fig. 6). In nonstress conditions, IbpA suppresses rpoH translation, while under heat stress conditions, IbpA acts as a “sequestrase” chaperone to recruit aggregation-prone proteins. This titrates the free IbpA away to alleviate the translation suppression. Concurrently, the high temperature–induced disruption of RNAT in the rpoH 5′ UTR enhances σ32 expression. The titration mechanism occurs at the endogenous level of IbpA, as artificial overexpression of IbpA fully inhibits σ32 translation, thereby compromising the heat shock response (cf. Figs. 2E and 5A).

Fig. 6.

Model of the IbpA's contribution in regulating the heat shock response. (Top) Under normal conditions, σ32 is inactivated by DnaK/J and GroEL/ES, and then degraded by FtsH at posttranslational level. In addition, rpoH translation is suppressed by a thermoresponsive mRNA secondary structure (RNAT) and IbpA. (Bottom) Under stress conditions, chaperones are recruited into heat-denatured proteins, leading to the release of σ32 repression due to inactivation/degradation and translational repression. This results in an increased functional σ32 level, eventually up-regulating Hsps.

A significant question regarding the function of IbpA concerns the mechanism by which IbpA interacts with various types of mRNAs to inhibit translation, given the lack of putative RNA-binding motif in IbpA. Our previous findings indicated that oligomeric IbpA state and secondary structures in RNAT are critical to translation suppression (28). Thus, the complex interplay between IbpA and mRNAs might be essential to its suppression ability. Moreover, understanding the difference between IbpA and IbpB, which lacks suppression activity, could provide valuable insight into this issue.

IbpA and IbpB, which lacks the translation suppression activity, are known to form hetero-oligomers (31, 32, 36). The present results show that even with IbpB coexistence, the regulatory function of IbpA on σ32 is not lost (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Although IbpA is known to be present in cells at significantly higher levels (3 to 10-fold) than IbpB (35, 37), the composition ratio of IbpA in heterooligomers is not well understood. Thus, the question of what oligomeric states of IbpA exhibit the regulation function in the cellular context will not be addressed without an understanding of the composition and dynamics of oligomeric species in vivo.

IbpA-mediated regulation of σ32 using a titration mechanism is conceptually analogous to the well-known σ32 regulatory mechanism involving DnaK/J, GroEL/ES, and FtsH (2, 4, 7, 13–15). Interestingly, the IbpA-dependent regulation is independent of the DnaK-mediated pathway, as the IbpA level affects the amount of σ32 even in the DnaK-deleted strain. How does this IbpA-mediated regulation relate to the regulation involving DnaK and other factors? The primary difference lies in the level of control, whether at the posttranslational or translational level. The DnaK/J and GroEL/ES chaperone systems suppress σ32 activity under normal conditions and facilitate FtsH-dependent degradation of σ32 (4, 12, 13). This inactivation–degradation mechanism relies on preexisting σ32 proteins after translation. In contrast, the IbpA-mediated mechanism operates at the translational level and can rapidly induce σ32 expression upon heat stress. Therefore, combining the two-layered mechanism at both translational and post-translational levels would be complementary, resulting in a more robust and flexible induction of σ32 during stress. Additionally, previous reports have indicated that excess Hsp and σ32 adversely affect growth (12, 16), further highlighting the importance of the two-layered mechanism.

In the pathway mediated by DnaK-GroEL, regulation of σ32 occurs not only in degradation but also in activity, with DnaK/J and GroEL binding to the inactive state of σ32 (4, 13). While our study focuses solely on IbpA's regulation of rpoH translation, it is plausible that IbpA, acting as a chaperone, may also contribute to regulating σ32 activity.

In a previous study, we proposed that the IbpA-mediated self-repression is a “safety catch” mechanism that tightly regulates IbpA expression, which can be harmful under normal conditions. The RNAT structure of ibpA is vital for its regulation, and its RNAT can partially open even under normal conditions, such as 37 °C (26, 28). This study also indicates that the rpoH 5′ UTR, responsible for the structure of RNAT, is required for translational regulation. The RNAT of rpoH opens between 30 and 40 °C, permitting partial translation of rpoH (23). IbpA may act as a safety catch for the rpoH RNAT to prevent the unnecessary expression of σ32 under conditions without stress. Indeed, since excess Hsp and σ32 have a detrimental effect on growth (12, 16), IbpA-mediated tight repression of σ32 under normal conditions is reasonable. The previously known role of IbpA is to sequester aggregation upon stress (35, 38–40), in contrast to the essential housekeeping roles of DnaK/J and GroEL/ES, even under normal conditions. Therefore, IbpA, without an apparent housekeeping role, may be suitable to function as a safety catch to prevent the production of unnecessary amounts of Hsps under normal conditions.

Our results regarding IbpA have implications for the σ32 shutoff phase during heat stress. Although the shutoff mechanism depends on the accelerated degradation mediated by the excessive amount of chaperones produced during heat shock (4, 7, 8), the level of σ32 is shutoff even when the degradation pathway is inhibited (19, 20) or with the hyperactive σ32 I54N mutant (18), suggesting an alternative shutoff mechanism. Since IbpA regulates the level of σ32 at a translational level, a different level from the canonical chaperone-mediated degradation regulation, IbpA may be responsible for regulating σ32 synthesis during the shutoff phase. Indeed, in the ΔibpAB strain, the σ32 shutoff, which occurs 10 min after the initiation of heat shock in the wild-type strain, does not occur but shuts off after 30 min (Fig. 5A). The σ32 shutoff observed at 30 min in the ΔibpAB cells would be induced by the canonical degradation pathway. The delayed shutoff in the ΔibpAB cells would be interpreted that IbpA affects the initial phase of the shutoff, followed by FtsH-mediated degradation assisted by induced chaperones such as DnaK (Fig. 6).

We observed that the ΔibpAB strain exhibited a slight delay in the recovery of growth after exposure to a heat shock at 42 °C. This observation supports a previous finding that the ΔibpAB cells display a delayed resolubilization of protein aggregates after heat shock (41), which may result from a slightly delayed recovery from stress in the ΔibpAB cells (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, it is known that the deletion of the ibpA-ibpB operon increases susceptibility to chaperone depletion (41). However, while IbpA can compensate for this depletion, its paralog IbpB cannot (33). We speculate that this difference arises from the subtle but significant difference between IbpA and IbpB. Besides their differences in chaperone function (33), the exclusive role of IbpA in suppressing the translation of σ32 might correlate with the phenotypes observed in the ΔibpAB strain.

What is the physiological significance of IbpA-mediated suppression of rpoH translation? One possibility is that the regulation of expression at the translation level is generally rapid and thus well-suited for immediate induction upon heat shock. Another advantage of tight suppression of the σ32 levels by IbpA under normal conditions is the suppression of Hsp expression, which is unnecessary in the absence of stress. In addition, the cost of ribosome occupancy for the translation of Hsps (6) would be reduced.

Last, are there other targets for IbpA-mediated translation suppression? Our findings suggest that IbpA overexpression decreases the level of endogenous rpoH mRNA without affecting its degradation rate (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). This result suggests that certain factors affect rpoH transcription in cells with IbpA-overexpression. Indeed, proteomics analysis has shown that expression of genes controlled by CRP, the dual transcriptional regulator of rpoH, is decreased in cells with IbpA overexpression (Dataset S2) (42). Further analysis is necessary to elucidate the complete regulatory picture mediated by IbpA.

Materials and Methods

E. coli Strains.

SI Appendix, Table S1 provides a comprehensive list of E. coli strains employed in this study. DH5α strain was used for cloning. The BW25113 strain was used for each assay. The chromosomal ibpA-ibpB or dnaK-dnaJ operons were deleted via previously described procedures (43). The DNA fragment amplified from JW3664 (ΔibpA::FRT-Km-FRT) (44), using the primers PT0456 and PM0195, and that from JW3663 (ΔibpB::FRT-Km-FRT) (44), using the primers PT0457 and PM0196, were annealed and amplified together using PT0456 and PT0457. The purified DNA was electroporated into the E. coli strain BW25113 harboring pKD46, and the transformant that was kanamycin-resistant at 40 µg/mL was stored as BW25113ΔibpAB. A list of primers utilized in the study is available in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Plasmids.

Plasmids were constructed using standard cloning procedures and Gibson assembly. Plasmids designed for overexpression purposes, including pCA24N-ibpA, pCA24N-ibpA-AEA, pCA24N-gfp, and pCA24N-ibpAB were constructed using DNA fragments that were amplified from pCA24N (45), superfolder GFP (46, 47), or E. coli genomic DNA. Plasmids were also constructed for the evaluation of expression, including pBAD30-dnaKpromoter-gfp, pBAD30-groESpromoter-gfp, pBAD30-dnaK 5′ UTR-gfp, pBAD30-groES 5′ UTR-gfp, pBAD30-rpoH 5′ UTR-rpoH, pBAD30-rpoH, pBAD30-rpoH 5′ UTR-rpoH-I54N, and pBAD30-ibpABoperon. These plasmids were constructed using DNA fragments amplified from pBAD30 (48), superfolder GFP (47), derived from a previously constructed plasmid (46), and E. coli genomic DNA. pKJE7 (Takara) was used to supply DnaKJ to the dnaK-dnaJ-deleted cells. The plasmids used in this study are listed in SI Appendix, Table S3.

MS Method.

E. coli BW25113 cells harboring a plasmid carrying the IbpA or GFP genes were grown at 37 °C in LB medium. The plasmids were induced with 50 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at an OD660 of 0.5. Cells were collected during the exponential phase (∼1.0 Abs660) by centrifugation at 20,000 × g. Sample preparation for liquid chromatography (LC)-MS/MS was conducted in accordance with a previous study with some modifications (49, 50). The quantitative LC-MS/MS analysis was conducted by using SWATH (sequential windowed acquisition of all theoretical mass spectra)-MS acquisition (51). All LC-MS/MS measurements were performed with Eksigent nanoLC 415 and TripleTOF 6600 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, USA). The trap column used for nanoLC was a 5.0-mm × 0.3-mm ODS column (L-column2, CERI, Japan), and the separation column was a 12.5-cm × 75-μm capillary column packed with 3-μm C18-silica particles (Nikkyo Technos, Japan). The libraries for SWATH acquisition were constructed on the basis of in-house IDA (information-dependent acquisition) measurements.

The SWATH acquisition and data analysis procedures were performed according to the previous study (49). Only proteins detected in all three measurements for both samples were used for calculating fold changes. The resulting protein intensities were averaged using an in-house R script. The P-value was determined using Welch's t test and corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg method for multiple comparisons, employing the "p.adjust" function in R (for Windows, version 4.1.2). GO enrichment analysis for increased/decreased proteins was performed with DAVID (52), using all detected protein data as background for enrichment analysis.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting.

E. coli BW25113 cells harboring a plasmid for evaluation were precultured at 30 °C for 16 h in LB medium. The cells were then grown to an OD660 of 0.4 ~ 0.6 in LB medium at 30 °C. For the pBAD30 plasmid, 2 × 10−4 % arabinose was used for induction of the reporter, while 0.1 mM IPTG was added 3 h after the start of the culture for pCA24N. In the coexpression assay, E. coli BW25113 cells harboring plasmids for evaluation and pCA24N plasmids were used. The induction of protein coexpression was performed with 0.1 mM IPTG, added 2 h after starting the culture. Cell cultures were harvested and mixed with an equal volume of 10% trichloroacetic acid, to terminate the biological reactions and precipitate macromolecules. After standing on ice for at least 15 min, the samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 3 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was removed by aspiration. Precipitates were washed with 1 mL acetone by vigorous mixing, centrifuged again, and dissolved in 1× SDS sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 5% sucrose, 0.005% bromophenol blue) by vortexing for 15 min at 37 °C. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and blocked using 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.002% Tween-20. Mouse anti-sera against GFP (mFx75, Wako), mouse anti-sera against His-tag (9C11, Wako), rabbit anti-sera against DnaK (abcam), rabbit anti-sera against GroES (a gift from Dr. Ayumi Koike–Takeshita at Kanagawa Institute of Technology), rabbit anti-sera against σ32 (Biolegend), and rabbit anti-sera against FtsZ (a gift from Dr. Shinya Sugimoto at Jikei Medical University) were used as primary antibodies at a 1:10,000 dilution. Secondary antibodies, Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) and Cy5-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam) were also used. Blotted membranes were detected with a fluorescence imager (Amersham Typhoon RGB, Cytiva), and band intensities were quantified with analysis software (Image quant, Cytiva).

qRT-PCR.

To quantify mRNA relative amounts, E. coli BW25113 cells harboring a plasmid harboring the reporter gene were precultured at 30 °C for 16 h in LB medium. The cells were then grown in 5 mL of LB medium at 37 °C to an OD660 of 0.4 ~ 0.6. The reporter gene carried in pBAD30 plasmid was induced with 2 × 10−4 % arabinose, and protein coexpression was induced by adding 0.1 mM IPTG 2 h after initiating the culture. The cultures were pelleted at 10,000 × g for 3 min at 4 °C.

For quantifying mRNA degradation, E. coli BW25113 cells harboring a plasmid carrying the reporter gene were precultured at 30 °C for 16 h in LB medium. The cells were then grown in 20 mL of LB medium at 30 °C to an OD660 of 0.4 ~ 0.6. The reporter gene in the pBAD30 plasmid was induced with 2 × 10−4 % arabinose. After 2.5 h from culture initiation, cells were aliquoted into 5 mL portions and treated with 250 µM Rifampicin. Cultures were sampled at 2, 5, and 10 min after Rifampicin treatment, and the cells were pelleted at 10,000 × g for 3 min at 4 °C.

Total mRNA was extracted using Tripure Isolation Reagent (Merck) and treated with recombinant DNase I (Takara). The treated RNA was subsequently purified using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). The samples were prepared using a Luna Universal One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (New England Biolabs). qRT-PCR was performed with an Mx3000P qPCR system (Agilent) and analyzed using the MxPro QPCR software (Agilent). The ΔΔCt method (53) was used to normalize the amount of target mRNA with the ftsZ mRNA. The primers used for PCR are listed in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Cell-Free Translation.

RNA templates produced by CUGA®7 in vitro transcription kit (Nippon Gene). The PURE system (PUREfrex, Gene-Frontier) reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 2 h in the presence or absence of 1 µM IbpA, which included Cy5 labeled tRNAfMet. After protein synthesis, SDS-sample buffer (0.125 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, 4% (w/v) SDS, 10% (w/v) sucrose, 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue) was added and incubated at 95 °C for 5 min. The samples were then separated by SDS-PAGE and detected using a fluorescence imager (Amersham Typhoon RGB, Cytiva) at the 633-nm wavelength. The band intensity was quantified with image analysis software (Image quant, Cytiva).

Statistical Analysis.

Student's t test was used for calculating statistical significance, with a two-tailed distribution with unequal variance. All experiments were conducted at least three times independently, and the mean values ± SD were represented in the figures.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Tatsuya Niwa for technical support on the LC-MS/MS analysis; Yajie Cheng for critical reading and valuable comments; the Bio-support Center at Tokyo Tech for DNA sequencing; the Cell Biology Center Research Core Facility at Tokyo Tech for the Q-Exactive and TripleTOF 6600 MS measurements; Ayumi Koike-Takeshita for the anti-GroES antibody; and Shinya Sugimoto for the anti-FtsZ antibody. This work was supported by MEXT Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant Numbers JP26116002, JP18H03984, and JP20H05925 to H.T., JP21K20631, and JP22K14860 to T.M.).

Author contributions

T.M. and H.T. designed research; T.M. performed research; T.M. and H.T. analyzed data; and T.M. and H.T. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting information. Raw data files are available in the Mendeley Data repository (DOI: 10.17632/x347y36n49.1) (54).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Hipp M. S., Kasturi P., Hartl F. U., The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 421–435 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mogk A., Bukau B., Kampinga H. H., Cellular handling of protein aggregates by disaggregation machines. Mol. Cell 69, 214–226 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mogk A., Ruger-Herreros C., Bukau B., Cellular functions and mechanisms of action of small heat shock proteins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 73, 89–110 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guisbert E., Yura T., Rhodius V. A., Gross C. A., Convergence of molecular, modeling, and systems approaches for an understanding of the Escherichia coli heat shock response. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72, 545–554 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arsène F., Tomoyasu T., Bukau B., The heat shock response of Escherichia coli. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 55, 3–9 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nonaka G., Blankschien M., Herman C., Gross C. A., Rhodius V. A., Regulon and promoter analysis of the E. coli heat-shock factor, σ32, reveals a multifaceted cellular response to heat stress. Genes Dev. 20, 1776–1789 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer A. S., Baker T. A., Proteolysis in the Escherichia coli heat shock response: A player at many levels. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 194–199 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straus D. B., Walter W. A., Gross C. A., The heat shock response of E. coli is regulated by changes in the concentration of σ32. Nature 329, 348–351 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita N., Ishihama A., Heat-shock induction of RNA polymerase sigma-32 synthesis in Escherichia coli: Transcriptional control and a multiple promoter system. Mol. Gen. Genet. 210, 10–15 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erickson J. W., Vaughn V., Walter W. A., Neidhardt F. C., Gross C. A., Regulation of the promoters and transcripts of rpoH, the Escherichia coli heat shock regulatory gene. Genes Dev. 1, 419–432 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tilly K., Erickson J., Sharma S., Georgopoulos C., Heat shock regulatory gene rpoH mRNA level increases after heat shock in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 168, 1155–1158 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guisbert E., Herman C., Lu C. Z., Gross C. A., A chaperone network controls the heat shock response in E. coli. Genes Dev. 18, 2812–2821 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo M. S., Gross C. A., Stress-induced remodeling of the bacterial proteome. Curr. Biol. 24, R424–R434 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mogk A., Huber D., Bukau B., Integrating protein homeostasis strategies in prokaryotes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, 1–19 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bittner L. M., Arends J., Narberhaus F., When, how and why? Regulated proteolysis by the essential FtsH protease in Escherichia coli. Biol. Chem. 398, 625–635 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim B., et al. , Heat shock transcription factor σ32 co-opts the signal recognition particle to regulate protein homeostasis in E. coli. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001735 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyazaki R., et al. , A novel SRP recognition sequence in the homeostatic control region of heat shock transcription factor σ32. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–11 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yura T., et al. , Analysis of σ32 mutants defective in chaperone-mediated feedback control reveals unexpected complexity of the heat shock response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 17638–17643 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanemori M., Mori H., Yura T., Induction of heat shock proteins by abnormal proteins results from stabilization and not increased synthesis of σ32 in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176, 5648–5653 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morita M. T., Kanemori M., Yanagi H., Yura T., Dynamic interplay between antagonistic pathways controlling the σ32 level in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5860–5865 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Straus D. B., Walter W., Gross C. A., DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE heat shock proteins negatively regulate heat shock gene expression by controlling the synthesis and stability of σ32. Genes Dev. 4, 2202–2209 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tatsuta T., et al. , Heat shock regulation in the ftsH null mutant of Escherichia coli: Dissection of stability and activity control mechanisms of σ32 in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 30, 583–593 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morita M. T., et al. , Translational induction of heat shock transcription factor σ32. Genes Dev. 13, 655–665 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kortmann J., Narberhaus F., Bacterial RNA thermometers: Molecular zippers and switches. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 255–265 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita M., Kanemori M., Yanagi H., Yura T., Heat-induced synthesis of σ32 in Escherichia coli: Structural and functional dissection of rpoH mRNA secondary structure. J. Bacteriol. 181, 401–410 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldminghaus T., Gaubig L. C., Klinkert B., Narberhaus F., The Escherichia coli ibpA thermometer is comprised of stable and unstable structural elements. RNA Biol. 6, 455–463 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaubig L. C., Waldminghaus T., Narberhaus F., Multiple layers of control govern expression of the Escherichia coli ibpAB heat-shock operon. Microbiology 157, 66–76 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miwa T., Chadani Y., Taguchi H., Escherichia coli small heat shock protein IbpA is an aggregation-sensor that self-regulates its own expression at posttranscriptional levels. Mol. Microbiol. 115, 142–156 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haslbeck M., Vierling E., A first line of stress defense: Small heat shock proteins and their function in protein homeostasis. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 1537–1548 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haslbeck M., Weinkauf S., Buchner J., Small heat shock proteins: Simplicity meets complexity. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 2121–2132 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matuszewska M., Kuczyńska-Wiśnik D., Laskowska E., Liberek K., The small heat shock protein IbpA of Escherichia coli cooperates with IbpB in stabilization of thermally aggregated proteins in a disaggregation competent state. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12292–12298 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matuszewska E., Kwiatkowska J., Ratajczak E., Kuczyńska-Wiśnik D., Laskowska E., Role of Escherichia coli heat shock proteins IbpA and IbpB in protection of alcohol dehydrogenase AdhE against heat inactivation in the presence of oxygen. Acta Biochim. Pol. 56, 55–61 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Obuchowski I., Piróg A., Stolarska M., Tomiczek B., Liberek K., Duplicate divergence of two bacterial small heat shock proteins reduces the demand for Hsp70 in refolding of substrates. PLoS Genet. 15, 1–25 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimizu Y., et al. , Supplemental material for “cell-free translation reconstituted with purified components”. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 751–5 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calloni G., et al. , DnaK functions as a central hub in the E. coli chaperone network. Cell Rep. 1, 251–264 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bissonnette S. A., Rivera-Rivera I., Sauer R. T., Baker T. A., The IbpA and IbpB small heat-shock proteins are substrates of the AAA+ Lon protease. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 1539–1549 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao L., et al. , The Hsp70 chaperone system stabilizes a thermo-sensitive subproteome in E. coli. Cell Rep. 28, 1335–1345.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dahiya V., Buchner J., Functional principles and regulation of molecular chaperones. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 114, 1–60 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenzweig R., Nillegoda N. B., Mayer M. P., Bukau B., The Hsp70 chaperone network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 665–680 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M., Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: From nascent chain to folded protein. Science. 295, 1852–1858 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mogk A., Deuerling E., Vorderwülbecke S., Vierling E., Bukau B., Small heat shock proteins, ClpB and the DnaK system form a functional triade in reversing protein aggregation. Mol. Microbiol. 50, 585–595 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kallipolitis B. H., Valentin-Hansen P., Transcription of rpoH, encoding the Escherichia coli heat-shock regulator σ32, is negatively controlled by the cAMP-CRP/CytR nucleoprotein complex. Mol. Microbiol. 29, 1091–1099 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L., One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baba T., et al. , Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: The Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006.0008 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.M. Kitagawa et al. , Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (A complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): Unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 12, 291–299 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishimoto T., Fujiwara K., Niwa T., Taguchi H., Conversion of a chaperonin GroEL-independent protein into an obligate substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 32073–32080 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pédelacq J. D., Cabantous S., Tran T., Terwilliger T. C., Waldo G. S., Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 79–88 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guzman L. M., Belin D., Carson M. J., Beckwith J., Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose P(BAD) promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177, 4121–4130 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onodera H., Niwa T., Taguchi H., Chadani Y., Prophage excision switches the primary ribosome rescue pathway and rescue-associated gene regulations in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 119, 44–58 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masuda T., Saito N., Tomita M., Ishihama Y., Unbiased quantitation of Escherichia coli membrane proteome using phase transfer surfactants. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 2770–2777 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gillet L. C., et al. , Targeted data extraction of the MS/MS spectra generated by data-independent acquisition: A new concept for consistent and accurate proteome analysis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 1–17 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang D. W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A., Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D., Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miwa T., Taguchi H., Escherichia coli small heat shock protein IbpA plays a role in regulating the heat shock response by controlling the translation of σ32. Mendeley Data. https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/x347y36n49/1. Accessed 13 June 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting information. Raw data files are available in the Mendeley Data repository (DOI: 10.17632/x347y36n49.1) (54).