Key Points

Question

Does intravenous magnesium sulfate for pregnant individuals at risk of delivery between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation reduce the risk of death or cerebral palsy in their children?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial including 1433 pregnant individuals at risk of preterm delivery and their 1679 infants found no significant difference in death or cerebral palsy at 2 years’ corrected age among children exposed to magnesium sulfate compared with placebo.

Meaning

Magnesium sulfate prior to preterm birth between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation did not increase the chance of child survival without cerebral palsy, although this study had limited power to detect an effect.

Abstract

Importance

Intravenous magnesium sulfate administered to pregnant individuals before birth at less than 30 weeks’ gestation reduces the risk of death and cerebral palsy in their children. The effects at later gestational ages are unclear.

Objective

To determine whether administration of magnesium sulfate at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation reduces death or cerebral palsy at 2 years.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial enrolled pregnant individuals expected to deliver at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation and was conducted at 24 Australian and New Zealand hospitals between January 2012 and April 2018.

Intervention

Intravenous magnesium sulfate (4 g) was compared with placebo.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was death (stillbirth, death of a live-born infant before hospital discharge, or death after hospital discharge before 2 years’ corrected age) or cerebral palsy (loss of motor function and abnormalities of muscle tone and power assessed by a pediatrician) at 2 years’ corrected age. There were 36 secondary outcomes that assessed the health of the pregnant individual, infant, and child.

Results

Of the 1433 pregnant individuals enrolled (mean age, 30.6 [SD, 6.6] years; 46 [3.2%] self-identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, 237 [16.5%] as Asian, 82 [5.7%] as Māori, 61 [4.3%] as Pacific, and 966 [67.4%] as White) and their 1679 infants, 1365 (81%) offspring (691 in the magnesium group and 674 in the placebo group) were included in the primary outcome analysis. Death or cerebral palsy at 2 years’ corrected age was not significantly different between the magnesium and placebo groups (3.3% [23 of 691 children] vs 2.7% [18 of 674 children], respectively; risk difference, 0.61% [95% CI, −1.27% to 2.50%]; adjusted relative risk [RR], 1.19 [95% CI, 0.65 to 2.18]). Components of the primary outcome did not differ between groups. Neonates in the magnesium group were less likely to have respiratory distress syndrome vs the placebo group (34% [294 of 858] vs 41% [334 of 821], respectively; adjusted RR, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.76 to 0.95]) and chronic lung disease (5.6% [48 of 858] vs 8.2% [67 of 821]; adjusted RR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.48 to 0.99]) during the birth hospitalization. No serious adverse events occurred; however, adverse events were more likely in pregnant individuals who received magnesium vs placebo (77% [531 of 690] vs 20% [136 of 667], respectively; adjusted RR, 3.76 [95% CI, 3.22 to 4.39]). Fewer pregnant individuals in the magnesium group had a cesarean delivery vs the placebo group (56% [406 of 729] vs 61% [427 of 704], respectively; adjusted RR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.84 to 0.99]), although more in the magnesium group had a major postpartum hemorrhage (3.4% [25 of 729] vs 1.7% [12 of 704] in the placebo group; adjusted RR, 1.98 [95% CI, 1.01 to 3.91]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Administration of intravenous magnesium sulfate prior to preterm birth at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation did not improve child survival free of cerebral palsy at 2 years, although the study had limited power to detect small between-group differences.

Trial Registration

anzctr.org.au Identifier: ACTRN12611000491965

This randomized clinical trial compares the effect of magnesium sulfate administered intravenously vs placebo on the outcome of death or cerebral palsy at 2 years in pregnant individuals expected to deliver at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation.

Introduction

Preterm birth remains the leading cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity worldwide. Compared with full-term infants, preterm infants who survive have a higher risk of cerebral palsy,1,2 which is a disorder of movement, posture, or both that comprises the most common childhood motor disability.3 Cerebral palsy causes substantial health issues for affected children and costs for their families and society.4,5 Because there is no cure for cerebral palsy, primary prevention is paramount.3

The prenatal use of magnesium sulfate to help protect the developing fetal brain from injury has been assessed in randomized clinical trials.6,7,8,9,10 The prenatal use of magnesium sulfate among pregnant individuals at risk of early preterm delivery improves the chance of their infant surviving without cerebral palsy.11,12 Clinical practice guidelines worldwide now recommend the use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection.13,14,15,16,17,18 However, there are limited data,19 and therefore a lack of consensus globally, regarding the optimal gestational age for prenatal use of magnesium sulfate. Some organizations recommend prenatal use of magnesium sulfate only before 30 weeks’ gestation,13,14,15 and others before 32 weeks’ gestation,16,17 or before 34 weeks’ gestation,18 and 2 suggest considering use between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation.14,15

The MAGENTA (Magnesium Sulphate at 30 to 34 Weeks’ Gestational Age) trial assessed the effects of magnesium sulfate compared with placebo administered to pregnant individuals at risk of imminent preterm birth (planned or definitely expected within the next 24 hours) between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation on the health of the infant, child, and pregnant individual. The primary hypothesis was that magnesium sulfate compared with placebo would reduce the risk of death or cerebral palsy in their children at 2 years’ corrected age.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This multicenter, randomized clinical trial was conducted at 24 Australian and New Zealand maternity hospitals. The trial protocol appears in Supplement 1, was approved by the human research ethics committee of the Children, Youth and Women’s Health Service, and has been published.19 The study was overseen by a data and safety monitoring committee. No interim analyses were undertaken.

Pregnant individuals were included if they were at risk of preterm birth between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation, experiencing a singleton or twin pregnancy, gave written consent, the birth was planned or definitely expected within 24 hours, and there were no contraindications (eg, respiratory depression, hypotension, absent patellar reflexes, kidney failure, or myasthenia gravis) to the use of prenatal magnesium sulfate.19 Pregnant individuals were ineligible if magnesium sulfate therapy was considered essential for the treatment of preeclampsia.

Randomization

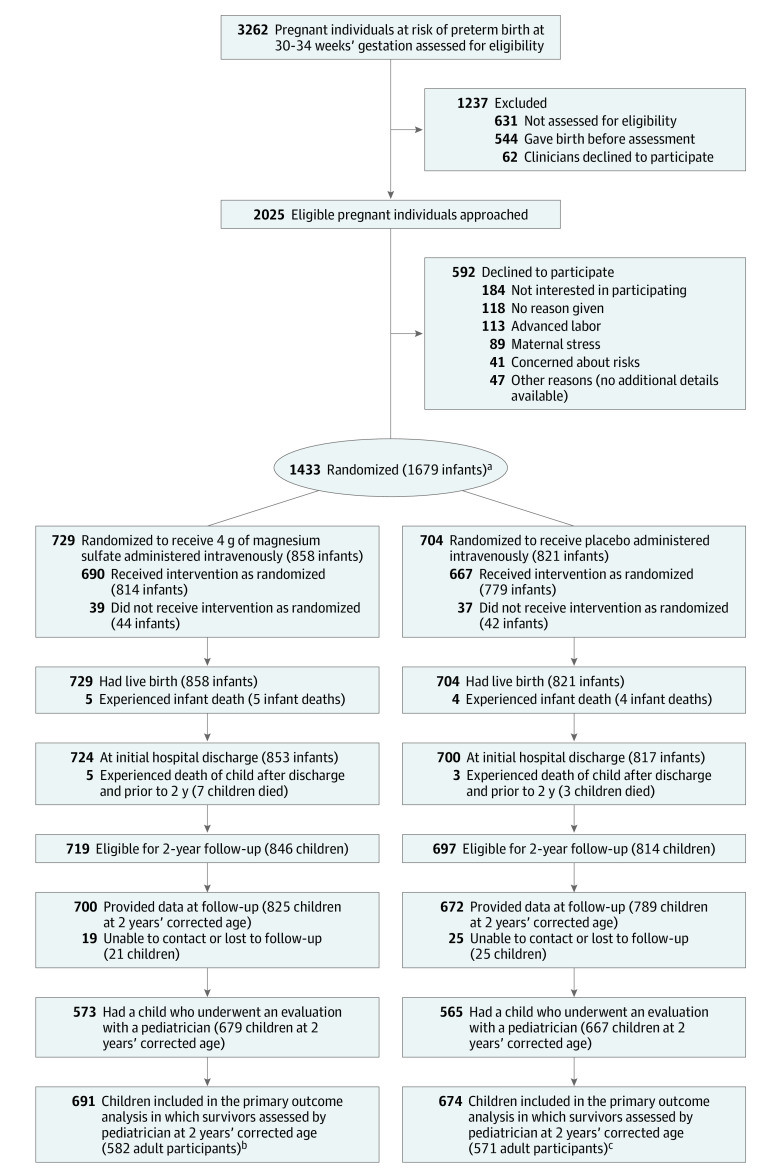

Eligible pregnant individuals were randomly assigned to the magnesium group or the placebo group using a central telephone randomization service (additional details appear in the trial protocol in Supplement 1 and in the Figure). The randomization schedule used balanced, variable block sizes and was performed by an investigator not involved in clinical care. There was stratification by hospital site, gestational age (30-31 weeks’ gestation and 32-33 weeks’ gestation), and the number of fetuses (1 or 2). A study number was allocated at randomization that corresponded to a treatment pack containing either magnesium sulfate or placebo (an isotonic sodium chloride solution). Participants, staff, investigators, and assessors of the children were blinded to the treatment allocation.

Figure. Recruitment, Randomization, and Assessment in a Trial of Prenatal Intravenous Magnesium for Imminent Preterm Birth.

aThere was stratification by hospital site, gestational age (30-31 weeks’ gestation and 32-33 weeks’ gestation), and the number of fetuses (1 or 2).

bFor the secondary outcomes, 858 infants (729 pregnant individuals) were included for the assessments prior to hospital discharge and 837 children (710 pregnant individuals) were included for the assessments at 2 years’ corrected age. Surviving children were assessed as close as possible to 2 years’ corrected age by a pediatrician and an assessor trained to administer the third edition of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-III). For the sensitivity analysis, which incorporated data from all sources (pediatrician, psychometrist, caregiver questionnaires, and caregiver), there were 823 children (697 pregnant individuals). For the adverse events and other secondary outcomes, 729 pregnant individuals were included.

cFor the secondary outcomes, 821 infants (704 pregnant individuals) were included for the assessments prior to hospital discharge and 796 children (679 pregnant individuals) were included for the assessments at 2 years’ corrected age. Surviving children were assessed as close as possible to 2 years’ corrected age by a pediatrician and an assessor trained to administer the BSID-III. For the sensitivity analysis, there were 785 children (670 participants). For the adverse events and other secondary outcomes, 704 pregnant individuals were included.

Procedures

Magnesium sulfate (4 g) or placebo was administered intravenously for 30 minutes. Participants and their infants were cared for according to standard practices at each hospital. Race and ethnicity data were collected by self-report as required by the human research ethics committee. The research staff obtained the study data from medical records. Surviving children were assessed by a pediatrician and an assessor trained to administer the third edition of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-III) as close as possible to 2 years’ corrected age.

The pediatric assessment included a neurological examination to diagnose cerebral palsy and other disability outcomes,20 assessment of vision and hearing, and measurement of height, weight, head circumference, and blood pressure. A diagnosis of cerebral palsy required loss of motor function and abnormalities of muscle tone and power,20 with gross motor dysfunction classified using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS).21

The psychological assessment included the cognitive, motor, and language scales of the BSID-III (standardized mean, 100 [SD, 15]22). Children with severe developmental delay who were unable to complete the assessment were assigned a standardized score of 40 (SD, −4).

Caregivers completed questionnaires about the child’s health, use of health services since birth, and behavior.23 Some caregivers were unable to attend the pediatric or psychological assessments or complete the questionnaires and instead provided information to researchers that met the minimum data requirement. Children not assessed by a pediatrician were considered to have cerebral palsy if the caregiver reported they did, or if they were unable to walk or sit without assistance, or control their head without support.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was death (defined as stillbirth, death of a live-born infant before hospital discharge, or death after hospital discharge before 2 years’ corrected age) or cerebral palsy (defined as loss of motor function and abnormalities of muscle tone and power assessed by a pediatrician).

Secondary Outcomes

There were 36 secondary outcomes that assessed the health of the pregnant individual, the infant, and the child. The secondary outcomes for the infant during the birth hospitalization included a composite serious health outcome that was counted as present if any of the following occurred: stillbirth, death of a live-born infant before hospital discharge, severe respiratory distress syndrome, severe intraventricular hemorrhage (grade 3 and 4), chronic lung disease (dependent on oxygen at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age or 28 days after birth if born after 32 weeks’ gestation), proven necrotizing enterocolitis (≥1 of the following: diagnosis at surgery or post mortem; radiological diagnosis with a clinical history plus pneumatosis intestinalis, portal vein gas, or a persistent dilated loop on serial x-rays; or a clinical history plus abdominal wall cellulitis and palpable abdominal mass), severe retinopathy of prematurity, or cystic periventricular leukomalacia.

Other secondary outcomes during the birth hospitalization were components of the composite outcome, intraventricular hemorrhage, neonatal encephalopathy, neonatal convulsions, patent ductus arteriosus requiring treatment, respiratory distress syndrome (defined as increasing respiratory distress, required increasing concentrations of oxygen, or needed ventilatory support from the first 6 hours of life with a chest radiograph showing generalized reticular granular pattern with or without an air bronchogram), severity of any respiratory disease, use of respiratory support, air leak requiring drainage, infection confirmed by culture within the first 48 hours and after 48 hours, and body size (weight, length, and head circumference) at birth and at discharge home.

The secondary outcomes for the children at 2 years’ corrected age were individual components of the primary outcome of death (stillbirth, death of live-born infant) and cerebral palsy (with severity classified as mild, moderate, or severe)20; death or any neurosensory disability (cerebral palsy [GMFCS levels 1-5], blindness [visual acuity in both eyes worse than 6/60], deafness [hearing loss sufficient to require hearing aids or cochlear implant], or cognitive or language score on BSID-III of >1 SD below the mean); death or major neurosensory disability (legal blindness, deafness, moderate or severe cerebral palsy [GMFCS levels 2-5], or cognitive or language score of >2 SD below the mean); motor delay (BSID-III motor score >1 SD below the mean; moderate or severe, >2 SD below the mean); cognitive, language, and motor scores; behavior assessed by the Child Behavior Checklist (a higher score indicates more behavioral problems)23; body size (height, weight, and head circumference along with z scores)24; and general health including health service use since birth, childhood respiratory morbidity, blood pressure (z scores for age, height, and sex),25 and hypertension (systolic or diastolic blood pressure above the 95th percentile).25

The secondary outcomes for the pregnant participants were serious adverse cardiovascular or respiratory outcomes from the infusion (death of the pregnant individual, cardiac arrest, or respiratory arrest), adverse events because of the infusion (including nausea, vomiting, flushing, infusion arm discomfort, dry mouth, sweating, dizziness, blurred vision, respiratory rate decreased >4 breaths per minute below baseline or <12 breaths per minute, blood pressure decreased >15 mm Hg below baseline, discontinuation of the infusion because of adverse events), postpartum hemorrhage with blood loss of 500 mL or greater,19 major postpartum hemorrhage with blood loss of 1500 mL or greater,19 and mode of birth.

Statistical Analysis

The trial’s target sample size was calculated based on an estimated incidence of 9.6% for the primary outcome of death or cerebral palsy at 2 years’ corrected age in this population born between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation.26 A trial of 1676 children (838 per group), allowing for a design effect of 1.2 for clustering of children within participants and 5% for those lost to follow-up, would have 80% power to detect a clinically important absolute risk difference of 4.2% (from 9.6% to 5.4%)6,27,28 for the primary outcome at a 2-tailed α level of .05.

The complete case analysis was considered the primary analysis because the assessment of missing data, which was blinded to the treatment allocations, revealed no concerning patterns of missingness. The unadjusted and adjusted analyses for hospital site, gestational age at entry, and number of fetuses were conducted following a prespecified statistical analysis plan with an intention-to-treat approach (additional information appears in the statistical analysis plan in Supplement 2).

Two-year outcomes were additionally adjusted for sex of the child, the socioeconomic status of the pregnant individual (categorized using Australian and New Zealand deprivation indices derived from residential postcodes),29,30 and language spoken at home because this can influence psychological test scores. For infant and childhood outcomes, generalized estimating equations were used with exchangeable correlations to account for clustering due to twins.

The binary outcomes were analyzed using log-binomial regression and the treatment effects are expressed as relative risks (RRs) and 95% CIs. The Fisher exact test was used to compare rare outcomes. Generalized linear regression with a binary distribution and the identity function was used to estimate the risk differences and 95% CIs.

Linear regression was used to analyze continuous variables and the treatment effects are expressed as mean differences and 95% CIs. Ordinal outcomes were analyzed with proportional odds models with the treatment effects expressed as odds ratios of higher severity, or with separate log-binominal regression for binary outcomes defined by different cut points with treatment effects expressed as RRs when the proportional odds assumption was not met. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons; thus, findings for the secondary outcomes should be interpreted as exploratory.

A prespecified sensitivity analysis examined the primary outcome using information from all data sources (pediatrician, psychometrist, caregiver questionnaires, and caregiver). A 2-sided P<.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Between January 2012 and February 2018, 1433 pregnant individuals were randomized and enrolled (1679 infants alive at entry). There were 729 pregnant individuals (51%) (858 infants) randomized to magnesium sulfate and 704 pregnant individuals (49%) (821 infants) randomized to placebo (Figure). The mean age of participants was 30.6 years (SD, 6.6 years); 46 (3.2%) self-identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, 237 (16.5%) as Asian, 82 (5.7%) as Māori, 61 (4.3%) as Pacific, and 966 (67.4%) as White. The 2 groups were similar at trial entry (Table 1). Almost 95% of participants in each group received the allocated treatment (Figure).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics for Pregnant Individuals.

| Magnesium sulfate (n = 729)a | Placebo (n = 704)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Participant age, mean (SD), y | 30.5 (6.2) | 30.6 (6.9) |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 359 (49.2) | 379 (53.8) |

| ≥1 | 370 (50.8) | 325 (46.2) |

| Race and ethnicityb | ||

| Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander | 22 (3.0) | 24 (3.4) |

| Asian | 127 (17.4) | 110 (15.6) |

| Māori | 43 (5.9) | 39 (5.5) |

| Pacific | 30 (4.1) | 31 (4.4) |

| White | 486 (66.7) | 480 (68.2) |

| Otherc | 21 (2.9) | 20 (2.8) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR)d | 25.0 (22.1-30.1) | 25.3 (22.2-29.8) |

| Gestational age at entry, mean (SD), wk | 32.1 (1.1) | 32.1 (1.1) |

| 30-<32 | 323 (44.3) | 308 (43.8) |

| 32-<34 | 406 (55.7) | 396 (56.3) |

| Socioeconomic statuse | ||

| Most disadvantaged | 192 (26.3) | 185 (26.3) |

| Disadvantaged | 108 (14.8) | 116 (16.5) |

| Middle | 171 (23.5) | 137 (19.5) |

| Advantaged | 140 (19.2) | 123 (17.5) |

| Most advantaged | 118 (16.2) | 143 (20.3) |

| Infant sex, No./total (%)f | ||

| Female | 385/858 (44.9) | 349/821 (42.5) |

| Male | 473/858 (55.1) | 472/821 (57.5) |

| Twin pregnancy | 130 (17.8) | 120 (17.0) |

| Prior event | ||

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation) | 149 (20.4) | 128 (18.2) |

| Perinatal death (≥20 weeks’ gestation) | 31 (4.3) | 30 (4.3) |

| Prenatal use of corticosteroids | 709 (97.3) | 682 (96.9) |

| Reason at risk for preterm birth | ||

| Preterm labor | 207 (28.4) | 182 (25.9) |

| Preterm and prelabor rupture of membranes | 206 (28.3) | 183 (26.0) |

| Fetal compromise | 129 (17.7) | 129 (18.3) |

| Preeclampsia | 65 (8.9) | 81 (11.5) |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 72 (9.9) | 67 (9.5) |

| Unspecified | 50 (6.9) | 62 (8.8) |

Data are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported by the pregnant individual at study entry.

Included African, Middle Eastern, and South American.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Derived from the Australian Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas29 and the New Zealand Socioeconomic Deprivation Profile.30

The denominators (858 + 821) equal the 1679 infants who were included in the randomization of the pregnant individuals.

Of the 1679 infants at randomization, 673 (40%) were born at 30 weeks’ gestation to less than 32 weeks’ gestation, 921 (55%) were born at 32 weeks’ gestation to less than 34 weeks’ gestation, and 85 (5%) were born at 34 weeks’ gestation or later. There were 1660 children eligible for the 2-year follow-up. Data at 2-year follow-up were provided for 825 of 846 children (97.5%) in the magnesium group and 789 of 814 children (96.9%) in the placebo group. The baseline characteristics were similar at trial entry among participants assessed at follow-up and the total study population (eTable 1 in Supplement 3).

Of the infants alive at trial entry, 691 of 858 (80.5%) in the magnesium group and 674 of 821 (82.1%) in the placebo group were included for the primary outcome of death or cerebral palsy (determined by pediatric assessment) at 2 years. The sensitivity analysis, which incorporated data from all sources (pediatrician, psychometrist, caregiver questionnaires, and caregiver), included 823 children (95.9%) in the magnesium group and 785 children (95.6%) in the placebo group.

Primary Outcome

Death or cerebral palsy (assessed by a pediatrician) at 2 years occurred in 3.3% (23 of 691) of children in the magnesium group and 2.7% (18 of 674) of children in the placebo group (risk difference, 0.61% [95% CI, −1.27% to 2.50%]; adjusted RR, 1.19 [95% CI, 0.65 to 2.18]; P = .57) (Table 2). In the sensitivity analysis, using data from all sources (pediatrician, psychometrist, caregiver questionnaires, and caregiver), which resulted in the inclusion of 1 additional case of cerebral palsy reported by the parents, the rate of death or cerebral palsy remained similar in both groups (2.8% [23 of 823] in the magnesium group vs 2.4% [19 of 785] in the placebo group; risk difference, 0.36% [95% CI, −1.25% to 1.97%]; adjusted RR, 1.15 [95% CI, 0.63 to 2.09], P = .65; Table 2). There were 12 deaths (1.4% [n = 837]) by 2 years’ corrected age in the magnesium group vs 7 deaths (0.9% [n = 796]) in the placebo group (risk difference, 0.48% [95% CI, −0.62% to 1.58%]; adjusted RR, 1.50 [95% CI, 0.58 to 3.86], P = .40; Table 2). There were no between-group differences in the proportion of children who had cerebral palsy (1.6% [11 of 679] in the magnesium group vs 1.7% [11 of 667] in the placebo group; risk difference, −0.03% [95% CI, −1.39% to 1.33%]; adjusted RR, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.43 to 2.23], P = .96).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes in Children at 2 Years’ Corrected Agea.

| No./total (%) | Risk difference (95% CI), % | Relative risk (95% CI) | P valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium sulfate | Placebo | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Death or cerebral palsy (loss of motor function and abnormalities of muscle tone and power) at 2 yc | 23/691 (3.3) | 18/674 (2.7) | 0.61 (−1.27 to 2.50) | 1.22 (0.66 to 2.27) | 1.19 (0.65 to 2.18) | .57 |

| Components of the primary outcome | ||||||

| Any deathd | 12/837 (1.4) | 7/796 (0.9) | 0.48 (−0.62 to 1.58) | 1.51 (0.58 to 3.90) | 1.50 (0.58 to 3.86) | .40 |

| Death of live-born infant before hospital discharge | 5/837 (0.6) | 4/796 (0.5) | 0.09 (−0.62 to 0.81) | NE | NE | >.99e |

| Death after discharge and <2 y | 7/837 (0.8) | 3/796 (0.4) | 0.38 (−0.42 to 1.18) | NE | NE | .34e |

| Cerebral palsyf | 11/679 (1.6) | 11/667 (1.7) | −0.03 (−1.39 to 1.33) | 0.98 (0.43 to 2.25) | 0.98 (0.43 to 2.23) | .96 |

| Sensitivity analysis for primary outcome | ||||||

| Death or cerebral palsyc,g | 23/823 (2.8) | 19/785 (2.4) | 0.36 (−1.25 to 1.97) | 1.15 (0.62 to 2.11) | 1.15 (0.63 to 2.09) | .65 |

| Secondary childhood outcomes | ||||||

| Death or any neurosensory disabilityh | 146/631 (23) | 165/630 (26) | −3.37 (−8.45 to 1.71) | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.07) | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.06) | .17 |

| Death or major neurosensory disabilityi,j | 57/629 (9.1) | 52/624 (8.3) | 0.44 (−2.89 to 3.76) | 1.05 (0.72 to 1.53) | 1.00 (0.69 to 1.45) | .99 |

| Severity of cerebral palsyk,l | ||||||

| None | 668/679 (98) | 656/667 (98) | ||||

| Mildf | 5/679 (0.7) | 7/667 (1.1) | −0.03 (−1.39 to 1.33) | 0.98 (0.43 to 2.25) | 0.98 (0.43 to 2.23) | .96 |

| Moderate | 5/679 (0.7) | 3/667 (0.5) | 0.28 (−0.63 to 1.20) | NE | NE | .75e |

| Severe | 1/679 (0.2) | 1/667 (0.2) | 0 (−0.41 to 0.41) | NE | NE | >.99e |

| Blindnessm | 1/679 (0.2) | 0/667 | −0.16 (−8.61 to 8.30) | NE | NE | >.99e |

| Deafnessn | 3/679 (0.4) | 5/667 (0.8) | −0.05 (−0.87 to 0.76) | NE | NE | .50e |

| Cognitive or language developmental delayo | 116/625 (19) | 128/624 (21) | −2.34 (−7.02 to 2.34) | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.13) | 0.88 (0.70 to 1.11) | .27 |

| Severity of cognitive or language developmental delayl,p | ||||||

| None | 509/625 (81) | 496/624 (80) | ||||

| Mild | 77/625 (12) | 92/624 (15) | −2.34 (−7.02 to 2.34) | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.13) | 0.88 (0.70 to 1.11) | .27 |

| Moderateq | 29/625 (4.6) | 32/624 (5.1) | 0.14 (−2.64 to 2.93) | 1.02 (0.64 to 1.63) | 1.00 (0.63 to 1.58) | .98 |

| Severe | 10/625 (1.6) | 4/624 (0.6) | 0.90 (−0.35 to 2.16) | NE | NE | .18e |

| Motor developmental delayj,r | 52/643 (8.1) | 67/635 (10.6) | −2.29 (−5.68 to 1.11) | 0.79 (0.55 to 1.12) | 0.78 (0.55 to 1.11) | .17 |

| Severity of motor developmental delayl,p | ||||||

| None | 591/643 (92) | 568/635 (89) | ||||

| Mildj | 34/643 (5.3) | 54/635 (8.5) | −2.29 (−5.68 to 1.11) | 0.79 (0.55 to 1.12) | 0.78 (0.55 to 1.11) | .17 |

| Moderateq | 11/643 (1.7) | 10/635 (1.6) | 0.86 (−0.90 to 2.63) | 1.42 (0.69 to 2.95) | 1.44 (0.70 to 2.95) | .33 |

| Severe | 7/643 (1.1) | 3/635 (0.5) | 0.62 (−0.35 to 1.58) | NE | NE | .34e |

| Developmental delays | ||||||

| Any | 132/624 (21) | 149/622 (24) | −2.96 (−7.90 to 1.98) | 0.88 (0.70 to 1.09) | 0.87 (0.70 to 1.08) | .20 |

| Severe | 12/623 (1.9) | 7/621 (1.1) | 0.78 (−0.67 to 2.22) | 1.66 (0.64 to 4.29) | 1.64 (0.63 to 4.23) | .31 |

| Required health services after hospital discharge | ||||||

| Hospital readmission | 261/702 (37) | 272/663 (41) | −3.27 (−8.65 to 2.12) | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.06) | 0.94 (0.82 to 1.07) | .34 |

| Any service | 241/691 (35) | 242/661 (37) | −1.36 (−6.79 to 4.07) | 0.96 (0.83 to 1.12) | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.14) | .84 |

| Childhood respiratory morbidityt | 226/702 (32) | 230/663 (35) | 2.20 (7.50 to 3.09) | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.12) | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.14) | .74 |

| Asthma or wheezing | 159/702 (23) | 158/663 (24) | −0.91 (−5.68 to 3.48) | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.18) | 1.02 (0.84 to 1.24) | .84 |

Abbreviation: NE, not estimable.

The analyses accounted for a within-participant clustering effect. The secondary outcomes of Child Behavior Check List scores (eTable 2), body size (eTable 3), and blood pressure (eTable 4) appear in Supplement 3.

Adjusted for hospital site, gestational age at entry, plurality, sex of the infant, language spoken at home, and socioeconomic status.

Defined as stillbirth, death of live-born infant before hospital discharge, or death after hospital discharge before 2 years’ corrected age or diagnosis of cerebral palsy. Adjusted for hospital site, gestational age at entry, plurality, sex of the infant, and language spoken at home.

Adjusted for hospital site, gestational age at entry, plurality, and sex of the infant.

Calculated using the Fisher exact test.

Adjusted for hospital site, gestational age at entry, and plurality.

Data were reported from all sources (pediatrician, psychometrist, caregiver questionnaires, and caregiver).

Death defined as stillbirth, death of live-born infant before hospital discharge, or death after hospital discharge before 2 years’ corrected age. Any neurosensory disabilities were defined as those that include the neurosensory impairments of cerebral palsy (Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS] levels 1-5), blindness (corrected visual acuity worse than <6/60 in the better eye), deafness (hearing loss requiring hearing aids or a cochlear implant), or any developmental delay (standardized score >1 SD below the mean).

Any death before 2 years’ corrected age or severe and moderate disability, including blindness (corrected visual acuity worse than <6/60 in the better eye), deafness requiring hearing aids, moderate or severe cerebral palsy (GMFCS levels 2-5), or developmental delay or intellectual impairment (standardized score >2 SD below the mean).

Adjusted for hospital site, gestational age at entry, plurality, sex of the infant, and language spoken at home.

Categorized as mild (GMFCS level 1), moderate (GMFCS level 2 or 3), or severe (GMFCS level 4 or 5).

Data are from separate log-binomial models (ie, mild vs none; moderate vs none or mild; and severe vs none, mild, or moderate) because a proportional odds assumption was not met.

Defined as visual acuity in both eyes worse than 6/60.

Defined as requiring hearing aids or a cochlear implant.

Defined by a standardized score greater than 1 SD below the mean (ie, <−1 SD).

Categorized as mild (standardized score of −2 SD to <−1 SD), moderate (standardized score of −3 SD to <−2 SD), or severe (standardized score <−3 SD).

Adjusted for gestational age at entry, plurality, sex of the infant, and language spoken at home.

Defined by a standardized score greater than 1 SD below the mean (<−1 SD).

Cognitive delay, language delay, or motor developmental delay.

Based on parental report of asthma, wheezing, or respiratory tract infection.

Secondary Outcomes

For the other childhood outcomes at 2 years’ corrected age, there were no significant between-group differences for death or any neurological disability, death or any major neurological disability, any of the individual neurosensory impairments, or the distribution of the severity of neurosensory disability (Table 2). For children born at 30 to 32 weeks’ gestation, the rate of death or cerebral palsy at 2 years was 3.3% (10 of 304) in the magnesium group vs 5.2% (15 of 291) in the placebo group and was 3.4% (13 of 387) and 0.8% (3 of 383), respectively, among those born at 32 to 34 weeks’ gestation. Children exposed to magnesium were more likely to have overall behavioral scores within the clinical problem range (10% [40 of 389]) compared with children in the placebo group (6% [24 of 379]) (adjusted RR, 1.66 [95% CI, 1.03 to 2.68], P = .04; eTable 2 in Supplement 3). At 2 years, there were no significant between-group differences for body size (eTable 3 in Supplement 3), blood pressure (eTable 4 in Supplement 3), use of health services (including readmission to the hospital), or respiratory morbidity (Table 2).

For the secondary outcomes occurring during the birth hospitalization, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome was less likely in the magnesium group (34% [294 of 858]) compared with the placebo group (41% [334 of 821]) (adjusted RR, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.76 to 0.95], P = .01; adjusted number needed to treat [NNT], 21 [95% CI, 11 to 333]) as was chronic lung disease (5.6% [48 of 858] vs 8.2% [67 of 821], respectively) (adjusted RR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.48 to 0.99], P = .04; adjusted NNT, 37 [95% CI, 20 to 204]; Table 3). There were no significant between-group differences for any of the other secondary outcomes (Table 3 and eTable 5 in Supplement 3).

Table 3. Secondary Outcomes for Live-Born Infants During the Birth Hospitalizationa.

| No./total (%) | Risk difference (95% CI), % | Relative risk (95% CI) | P valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium sulfate | Placebo | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |||

| Gestational age at birth, mean (SD), wk | 32.4 (1.5) [n = 858] | 32.3 (1.4) [n = 821] | 0.07 (−0.08 to 0.22)c | NE | 0.09 (−0.02 to 0.20)c | .12 |

| Composite serious health outcomed | 81/384 (21) | 99/420 (24) | −1.98 (−7.87 to 3.91) | 0.91 (0.70 to 1.19) | 0.95 (0.72 to 1.23) | .68 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | ||||||

| Anye | 56/854 (6.6) | 55/818 (6.7) | −0.02 (−2.47 to 2.42) | 1.00 (0.69 to 1.44) | 0.97 (0.68 to 1.39) | .88 |

| Severe (grade 3 or 4) | 3/854 (0.4) | 3/818 (0.4) | −0.02 (−0.59 to 0.56) | NE | NE | >.99f |

| Cystic periventricular leukomalacia | 2/854 (0.2) | 6/818 (0.7) | −0.50 (−1.17 to 0.17) | NE | NE | .17f |

| Neonatal encephalopathy | 1/858 (0.1) | 1/821 (0.1) | −0.01 (−0.34 to 0.33) | NE | NE | >.99f |

| Neonatal convulsions | 7/858 (0.8) | 3/821 (0.4) | 0.45 (−0.28 to 1.18) | NE | NE | .34f |

| Proven necrotizing enterocolitisg | 2/858 (0.2) | 1/821 (0.1) | 0.11 (−0.29 to 0.51) | NE | NE | >.99f |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | ||||||

| Any requiring treatment | 23/265 (8.7) | 30/282 (11) | −1.57 (−6.74 to 3.61) | 0.85 (0.50 to 1.44) | 0.89 (0.54 to 1.48) | .66 |

| Severe (stage 3 or worse in better eye) | 3/266 (1.1) | 2/284 (0.7) | 0.42 (−1.18 to 2.03) | NE | NE | .68f |

| Patent ductus arteriosus requiring treatment | 8/858 (0.93) | 15/821 (1.83) | −0.85 (−2.00 to 0.31) | 0.52 (0.21 to 1.26) | 0.46 (0.19 to 1.13) | .09 |

| Neonatal respiratory distress syndromeh | 294/858 (34) | 334/821 (41) | −5.92 (−10.75 to −1.11) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.97) | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.95) | .01 |

| Severity of respiratory diseasei | ||||||

| None | 564/858 (66) | 487/821 (59) | ||||

| Mild | 124/858 (14) | 136/821 (17) | −5.92 (−10.75 to −1.11) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.97) | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.95) | .01 |

| Moderate | 141/858 (16) | 166/821 (20) | −4.13 (−8.26 to 0) | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.00) | 0.81 (0.68 to 0.97) | .02 |

| Severe | 29/858 (3) | 32/821 (4) | −0.31 (−2.19 to 1.56) | 0.92 (0.55 to 1.53) | 0.89 (0.54 to 1.47) | .64 |

| Use of oxygen therapy | 332/858 (39) | 375/821 (46) | −6.63 (−11.55 to −1.71) | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.96) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.96) | .01 |

| Chronic lung diseasej | 48/858 (5.6) | 67/821 (8.2) | −2.39 (−4.88 to 0.11) | 0.70 (0.49 to 1.01) | 0.69 (0.48 to 0.99) | .04 |

| Required oxygen when discharged homek | 8/853 (0.9) | 18/817 (2.2) | −1.26 (−2.46 to −0.07) | 0.43 (0.19 to 0.97) | 0.43 (0.19 to 0.98) | .04 |

| Use of respiratory support | 533/858 (62) | 535/821 (65) | −3.32 (−8.15 to 1.51) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.02) | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) | .19 |

| Air leak syndromek | 9/858 (1.0) | 14/821 (1.7) | −0.65 (−1.77 to 0.46) | 0.62 (0.27 to 1.42) | 0.62 (0.27 to 1.41) | .25 |

| Proven infectionl | ||||||

| Within first 48 h | 4/858 (0.5) | 3/821 (0.4) | 0.10 (−0.51 to 0.72) | NE | NE | >.99f |

| After first 48 h | 14/858 (1.6) | 13/821 (1.6) | 0.05 (−1.16 to 1.25) | 1.03 (0.49 to 2.18) | 1.04 (0.50 to 2.18) | .92 |

Abbreviation: NE, not estimable.

The analyses accounted for a within-participant clustering effect. The secondary outcomes of weight, length, and head circumference appear in eTable 5 in Supplement 3.

Adjusted for hospital site, gestational age at entry, and plurality.

Expressed as mean difference (95% CI).

Stillbirth, death of live-born infant before hospital discharge, severe respiratory disease, severe intraventricular hemorrhage, chronic lung disease, proven necrotizing enterocolitis, severe retinopathy of prematurity, or cystic periventricular leukomalacia.

Identified from cranial ultrasound within the first 7 days.

Calculated using the Fisher exact test.

Defined as at least 1 of the following: diagnosis at surgery or post mortem; radiological diagnosis with a clinical history plus pneumatosis intestinalis, or portal vein gas, or a persistent dilated loop on serial x-rays; or a clinical history plus abdominal wall cellulitis and palpable abdominal mass.

Defined as increasing respiratory distress or oxygen requirements or need for ventilatory support from the first 6 hours of life with a chest x-ray showing generalized reticular granular pattern.

Data are from separate log-binomial models (ie, mild, moderate, or severe vs none, moderate, or severe vs none or mild; and severe vs none, mild, or moderate) because a proportional odds assumption was not met.

Oxygen dependent at 36 weeks’ gestation or 28 days of life if born after 32 weeks’ gestation.

Adjusted for gestational age at entry and plurality.

Infection confirmed by culture.

There were no serious cardiovascular or respiratory adverse outcomes from the study infusion (Table 4). Adverse events because of the infusion (eg, nausea, vomiting, flushing, infusion arm discomfort, dry mouth, dizziness, and blurred vision) were more likely in the magnesium group (77% [531 of 690 pregnant individuals]) compared with the placebo group (20% [136 of 667 pregnant individuals]) (adjusted RR, 3.76 [95% CI, 3.22 to 4.39], P < .001). The infusion was more likely to be discontinued because of adverse events in the magnesium group (2.9% [20 of 690] vs 0.2% [1 of 667] in the placebo group, P < .001).

Table 4. Outcomes for Pregnant Individuals During the Birth Hospitalizationa.

| No./total (%) | Risk difference (95% CI), % | Relative risk (95% CI) | P valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium sulfate | Placebo | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |||

| Adverse events because of the infusion | ||||||

| Any | 531/690 (77) | 136/667 (20) | 56.57 (52.18 to 60.95) | 3.77 (3.23 to 4.41) | 3.76 (3.22 to 4.39) | <.001 |

| Nausea | 108/690 (16) | 36/667 (5.4) | 10.25 (7.05 to 13.46) | 2.90 (2.02 to 4.16) | 2.90 (2.02 to 4.16) | <.001 |

| Vomiting | 36/690 (5.2) | 15/667 (2.3) | 2.97 (0.96 to 4.97) | 2.32 (1.28 to 4.20) | 2.31 (1.28 to 4.15) | .01 |

| Flushing | 400/690 (58) | 55/667 (8.3) | 49.73 (45.49 to 53.96) | 7.03 (5.42 to 9.13) | 6.96 (5.36 to 9.03) | <.001 |

| Arm discomfort | 275/690 (40) | 24/667 (3.6) | 36.26 (32.34 to 40.17) | 11.1 (7.4 to 16.6) | 11.1 (7.4 to 16.6) | <.001 |

| Dry mouth | 125/690 (18) | 23/667 (3.5) | 14.67 (11.48 to 17.86) | 5.25 (3.41 to 8.09) | 5.18 (3.37 to 7.97) | <.001 |

| Sweating | 87/690 (13) | 15/667 (2.3) | 9.48 (6.77 to 12.19) | 5.61 (3.28 to 9.60) | 5.42 (3.17 to 9.26) | <.001 |

| Dizziness | 83/690 (12) | 17/667 (2.6) | 3.90 (2.29 to 5.50) | 4.72 (2.83 to 7.87) | 4.71 (2.83 to 7.84) | <.001 |

| Blurred vision | 30/690 (4.4) | 3/667 (0.5) | 10.36 (7.64 to 13.08) | NE | NE | <.001c |

| Respiratory rated | 5/690 (0.7) | 3/667 (0.5) | 0.27 (−0.54 to 1.09) | NE | NE | .73c |

| Blood pressuree | 42/690 (6.1) | 18/667 (2.7) | 3.39 (1.22 to 5.56) | 2.26 (1.31 to 3.88) | 2.20 (1.28 to 3.77) | .004 |

| Discontinued infusion because of adverse events | 20/690 (2.9) | 1/667 (0.2) | 2.75 (1.46 to 4.03) | NE | NE | <.001c |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | ||||||

| Any (≥500 mL) | 170/729 (23) | 167/704 (24) | −0.40 (−4.79 to 3.99) | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.18) | 0.98 (0.81 to 1.17) | .80 |

| Major (≥1000 mL) | 25/729 (3.4) | 12/704 (1.7) | 1.72 (0.09 to 3.36) | 2.01 (1.02 to 3.97) | 1.98 (1.01 to 3.91) | .05 |

| Blood transfusion given | 24/729 (3.3) | 16/704 (2.3) | 1.02 (−0.68 to 2.72) | 1.45 (0.78 to 2.70) | 1.46 (0.78 to 2.72) | .23 |

| Cesarean delivery | 406/729 (56) | 427/704 (61) | −4.96 (−10.06 to 0.14) | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.00) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.99) | .03 |

| Elective | 140/729 (19) | 135/704 (19) | 0.03 (−4.05 to 4.11) | 1.00 (0.81 to 1.24) | 1.00 (0.81 to 1.22) | .96 |

| Emergency | 256/729 (35) | 284/704 (40) | −5.22 (−10.24 to −0.21) | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.99) | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.98) | .03 |

| Reason for cesarean delivery | ||||||

| Abnormal lie | 97/729 (13) | 105/704 (15) | ||||

| Fetal compromise | 91/729 (13) | 100/704 (14) | ||||

| Hemorrhage | 76/729 (10) | 62/704 (8.8) | ||||

| Twin pregnancy | 58/729 (8.0) | 68/704 (9.7) | ||||

| Previous cesarean delivery | 53/729 (7.3) | 54/704 (7.7) | ||||

Abbreviation: NE, not estimable.

There were no cases of serious cardiovascular or respiratory adverse events (eg, death of pregnant individual, cardiac arrest, or respiratory arrest).

Adjusted for hospital site, gestational age at entry, and plurality.

Calculated using the Fisher exact test.

Decreased to greater than 4 breaths/min below baseline or decreased to less than 12 breaths/min.

Decreased to greater than 15 mm Hg below baseline level.

Fewer individuals in the magnesium group had a cesarean delivery (56% [406 of 729]) compared with the placebo group (61% [427 of 704]) (adjusted RR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.84 to 0.99], P = .03; adjusted NNT, 19 [95% CI, 10 to 400]; Table 4). In the post hoc analyses, no between-group differences were seen in the indications for the cesarean delivery. There were no between-group differences in the risk of postpartum hemorrhage or need for a blood transfusion; however, more participants in the magnesium group (3.4% [25 of 729]) had a major postpartum hemorrhage compared with the placebo group (1.7% [12 of 704]) (adjusted RR, 1.98 [95% CI, 1.01 to 3.91], P = .05).

Discussion

In this multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial comparing magnesium sulfate given to pregnant individuals at risk of preterm birth between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation vs placebo, no significant difference was found for the primary outcome of death or cerebral palsy in their children at 2 years’ corrected age.

This trial’s findings contrast with trials that identified a benefit of intravenous magnesium for children born at earlier gestational ages. The reason for the lack of effect in the age range of 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation is unclear. The treatment dose used in this trial, 4 g of magnesium without a maintenance infusion, was shown from analyses of individual participant data in a meta-analysis12 to reduce the incidence of both cerebral palsy and death and cerebral palsy alone. The risk differences for the combined outcome of death or cerebral palsy, and its components of death and cerebral palsy in the current trial, are consistent with the treatment effect and CIs reported in the meta-analysis12 among the age subgroups of 30 to 31 weeks’ gestation and 32 weeks’ gestation or longer. It is possible that the mechanism of brain injury by which extremely preterm birth leads to cerebral palsy may be different from mechanisms relevant at later gestational ages.

Although intraventricular hemorrhage is less common at later gestational ages, data from the analyses of individual participant data in a meta-analysis12 show the mechanism of action of magnesium does not appear to be related to intraventricular hemorrhage. Beyond 30 weeks’ gestation, there is continued advancement in neuronal migration and oligodendrocyte maturation, both of which can be disrupted by preterm birth at these gestational ages and may be related to subsequent development of cerebral palsy.31

Because death and cerebral palsy are competing outcomes, the combined outcome of death or cerebral palsy is often considered the most clinically relevant outcome for assessing interventions for neuroprotection during the perinatal period.32 However, it is also important to assess possible neonatal effects.32 Even though the analyses of secondary outcomes need to be considered as exploratory because no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons, several potentially clinically important between-group differences were found. Significantly fewer infants exposed to magnesium had neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, and significantly fewer had chronic lung disease. Although differences in treatment approaches between hospitals may have influenced the proportion of infants meeting the definitions of respiratory distress syndrome and chronic lung disease, randomization was stratified by hospital site and therefore such differences are unlikely to have influenced the current findings.

An earlier trial reported lower chronic lung disease incidence with magnesium,10 and magnesium has been used to treat children with moderate to severe asthma33 and infants with persistent pulmonary hypertension.34 Chronic lung disease is a recognized risk factor for later neurosensory impairment and the findings from the current study suggest that any future trials should be designed to achieve adequate statistical power to assess this outcome. In contrast, children exposed to magnesium had more behavioral problems, but, to our knowledge, there is no known biological basis for the difference observed. Behavioral problems during early childhood have not been well reported in previous trials.6,7,8,9,10,12 Two trials with follow-up of school-aged children found no difference in behavior between the children exposed to magnesium and those who were not.35,36 Thus, further follow-up is needed to assess the balance of these possible benefits and harms later in childhood.

No serious cardiovascular or respiratory adverse events were reported for participants receiving the study medication. However, all adverse events assessed were more common for participants receiving magnesium, as reported in previous trials,6,7,8,9 and, for some of the participants in the current trial, this resulted in cessation of the medication. This suggests that efforts to identify ways to improve administration of magnesium to reduce adverse events should continue.37

Fewer participants had a cesarean delivery in the magnesium group, but no between-group difference in the reasons for cesarean delivery was found in the post hoc analysis. Mode of birth was not different in the analyses of the individual participant data in a meta-analysis12; thus, this finding remains unexplained. Major postpartum hemorrhage was more likely in the magnesium group, but postpartum hemorrhage was not. Concern has been raised that magnesium mediates vascular relaxation and could cause uterine atony and postpartum hemorrhage. However, systematic review of randomized trials has not shown this,12,38 possibly because effects on placental vessels are different from the effects on nonplacental vessels.39

Neonates exposed to magnesium in utero had reduced risk of respiratory distress syndrome and chronic lung disease, but were more likely to have child behavior scores within the clinical problem range at 2 years. More participants who received magnesium reported adverse events and the risk of major postpartum hemorrhage was higher, but fewer gave birth by cesarean delivery. These results can be used to aid decisions on use of prenatal magnesium for pregnant individuals at risk of preterm birth at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation.

Limitations

This trial has limitations. First, because the event rates for death and cerebral palsy were lower than predicted,19 the sample size lacked power to detect small but potentially important differences in the risk of death or cerebral palsy.

Second, the primary outcome, which required assessment by a pediatrician at 2 years’ corrected age for the children, was only available for 1365 of the 1679 infants (81%) randomized. However, the findings were unchanged when inclusion of additional information from parents allowed analysis for 1608 of the 1679 infants (96%) randomized.

Third, although the major strength of this trial was its randomized, multicenter design including 24 hospitals in Australia and New Zealand, these are 2 high-income countries with publicly funded, well-coordinated health care systems. The results are likely most generalizable to similar health care settings. Further assessment on the efficacy and safety of magnesium for neuroprotection in lower-resource settings is warranted.

Conclusion

Administration of intravenous magnesium sulfate prior to preterm birth at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation did not improve child survival free of cerebral palsy at 2 years, although the study had limited power to detect small between-group differences.

Educational Objective: To identify the key insights or developments described in this article.

-

This study evaluated prevention of cerebral palsy with the use of magnesium sulfate prior to preterm birth. Who was included in the study?

All pregnant individuals presenting before 30 weeks’ gestation regardless of risk for preterm delivery.

Pregnant individuals at risk of preterm birth between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation with a singleton or twin pregnancy.

Pregnant individuals receiving magnesium therapy for treatment of preeclampsia.

-

The primary outcome for this study was death or cerebral palsy at 2 years’ corrected age. What did the authors find?

The results could not be meaningfully assessed because more than 25% of the placebo group received the active treatment prior to delivery.

The combined outcome demonstrated statistically significant improvement with magnesium, primarily because incidence of any death before 2 years was higher in the placebo group.

There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of death or cerebral palsy at 2 years.

-

The authors note that the results of this trial differed from earlier trials that identified a benefit of intravenous magnesium for children born before 30 weeks’ gestation. What do they suggest might explain this difference?

Increased adverse events with magnesium sulfate led to increased rates of cesarean delivery in the intervention group.

Intraventricular hemorrhage is more common at later gestational ages making the combined outcome that includes death before 2 years less reliable.

The mechanism by which brain injury leads to cerebral palsy may differ between earlier and later gestational ages.

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eTable 1. Baseline participant and pregnancy characteristics: the analysis cohort versus the whole eligible cohort

eTable 2. Child Behaviour Check List scores at two years corrected age (secondary childhood outcome)

eTable 3. Body size at two years corrected age (secondary childhood outcome)

eTable 4. Blood Pressure at two years corrected age (secondary childhood outcome)

eTable 5. Infant weight, length and head circumference at birth and at discharge after birth

eReferences

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Cao G, Liu J, Liu M. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality of neonatal preterm birth, 1990-2019. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(8):787-796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):261-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntyre S, Novak I, Cusick A. Consensus research priorities for cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(3):270-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonmukayakul U, Shih STF, Bourke-Taylor H, et al. Systematic review of the economic impact of cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2018;80:93-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangham LJ, Petrou S, Doyle LW, et al. The cost of preterm birth throughout childhood in England and Wales. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e312-e327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Doyle LW, et al. Effect of magnesium sulfate given for neuroprotection before preterm birth. JAMA. 2003;290(20):2669-2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marret S, Marpeau L, Zupan-Simunek V, et al. Magnesium sulphate given before very-preterm birth to protect infant brain. BJOG. 2007;114(3):310-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittendorf R, Dambrosia J, Pryde PG, et al. Association between the use of antenatal magnesium sulfate in preterm labor and adverse health outcomes in infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1111-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rouse DJ, Hirtz DG, Thom E, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(9):895-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf HT, Brok J, Henriksen TB, et al. Antenatal magnesium sulphate for the prevention of cerebral palsy in infants born preterm. BJOG. 2020;127(10):1217-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyle LW, Crowther CA, Middleton P, et al. Magnesium sulphate for women at risk of preterm birth for neuroprotection of the fetus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD004661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowther CA, Middleton PF, Voysey M, et al. Assessing the neuroprotective benefits for babies of antenatal magnesium sulphate. PLoS Med. 2017;14(10):e1002398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antenatal Magnesium Sulphate for Neuroprotection Guideline Development Panel . Antenatal magnesium sulphate prior to preterm birth for neuroprotection of the fetus, infant and child. Accessed May 24, 2023. http://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/liggins/our-research/research-themes/healthy-mothers-healthy-babies/research-synthesis.html

- 14.Shennan A, Suff N, Jacobsson B, et al. FIGO good practice recommendations on magnesium sulphate administration for preterm fetal neuroprotection. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;155(1):31-33. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.1385634669972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . NICE guideline [NG25]: preterm labour and birth. Accessed July 19, 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25 [PubMed]

- 16.World Health Organization . WHO recommendations on interventions to improve preterm birth outcomes. Accessed July 19, 2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/183037/9789241508988_eng.pdf [PubMed]

- 17.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics . Practice bulletin No. 171. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e155-e164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magee LA, De Silva DA, Sawchuck D, et al. No. 376-magnesium sulphate for fetal neuroprotection. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(4):505-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crowther CA, Middleton PF, Wilkinson D, et al. Magnesium sulphate at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestational age. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doyle LW; Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group . Changing availability of neonatal intensive care for extremely low birthweight infants in Victoria over two decades. Med J Aust. 2004;181(3):136-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, et al. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39(4):214-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (Third Edition). Harcourt Assessment (PsychCorp); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behaviour Checklist 2/3 and 1992 Profile. University of Vermont; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman JV, Cole TJ, Chinn S, et al. Cross sectional stature and weight reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73(1):17-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosner B, Prineas RJ, Loggie JM, Daniels SR. Blood pressure nomograms for children and adolescents, by height, sex, and age, in the United States. J Pediatr. 1993;123(6):871-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australia’s mothers and babies 2008. Accessed July 19, 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies-2008/summary

- 27.Marret S, Marpeau L, Bénichou J. Benefit of magnesium sulfate given before very preterm birth to protect infant brain. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):225-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowther CA, Doyle LW, Haslam RR, et al. Outcomes at 2 years of age after repeat doses of antenatal corticosteroids. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1179-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2033.0.55.001—Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. Accessed July 19, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2033.0.55.001#

- 30.Atkinson J, Salmond C, Crampton P. NZDep2018 Index of Deprivation, Interim Research Report, December 2019. University of Otago; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw JC, Crombie GK, Palliser HK, Hirst JJ. Impaired oligodendrocyte development following preterm birth. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:618052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marlow N. Is survival and neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years of age the gold standard outcome for neonatal studies? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100(1):F82-F84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffiths B, Kew KM; Cochrane Airways Group . Intravenous magnesium sulfate for treating children with acute asthma in the emergency department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4(4):CD011050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho JJ, Rasa G. Magnesium sulfate for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007(3):CD005588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doyle LW, Anderson PJ, Haslam R, et al. School-age outcomes of very preterm infants after antenatal treatment with magnesium sulfate vs placebo. JAMA. 2014;312(11):1105-1113. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chollat C, Enser M, Houivet E, et al. School-age outcomes following a randomized controlled trial of magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection of preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2014;165(2):398-400.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bain ES, Middleton PF, Yelland LN, et al. Maternal adverse effects with different loading infusion rates of antenatal magnesium sulphate for preterm fetal neuroprotection. BJOG. 2014;121(5):595-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pergialiotis V, Bellos I, Constantinou T, et al. Magnesium sulfate and risk of postpartum uterine atony and hemorrhage. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;256:158-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang J, He A, Li N, et al. Magnesium sulfate–mediated vascular relaxation and calcium channel activity in placental vessels different from nonplacental vessels. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(14):e009896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eTable 1. Baseline participant and pregnancy characteristics: the analysis cohort versus the whole eligible cohort

eTable 2. Child Behaviour Check List scores at two years corrected age (secondary childhood outcome)

eTable 3. Body size at two years corrected age (secondary childhood outcome)

eTable 4. Blood Pressure at two years corrected age (secondary childhood outcome)

eTable 5. Infant weight, length and head circumference at birth and at discharge after birth

eReferences

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement