Abstract

A panel of CD4+ T-cell clones were generated from peripheral blood lymphocytes from a patient with a nonprogressing infection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) by using herpesvirus saimiri as described recently. By and large, all of the clones expressed an activated T-cell phenotype (Th class 1) and grew without any further stimulation in interleukin-2-containing medium. None of these clones produced HIV-1, and all clones were negative for HIV-1 DNA. When these clones were infected with primary and laboratory (IIIB) strains of HIV-1 with syncytium-inducing (SI) phenotypes, dramatic variation of virus production was observed. While two clones were highly susceptible, other clones were relatively or completely resistant to infection with SI viruses. The HIV-resistant clones expressed CXCR4 coreceptors and were able to fuse efficiently with SI virus env-expressing cells, indicating that no block to virus entry was present in the resistant clones. Additionally, HIV-1 DNA was detectable after infection of the resistant clones, further suggesting that HIV resistance occurred in these clones after virus entry and probably after integration. We further demonstrate that the resistant clones secrete a factor(s) that can inhibit SI virus production from other infected cells and from a chronically infected producer cell line. Finally, we show that the resistant clones do not express an increased amount of ligands (stromal-derived factor SDF-1) of CXCR4 or other known HIV-inhibitory cytokines. Until now, the ligands of HIV coreceptors were the only natural substances that had been shown to play antiviral roles of any real significance in vivo. Our data from this study show that differential expression of another anti-HIV factor(s) by selected CD4+ T cells may be responsible for the protection of these cells against SI viruses. Our results also suggest a novel mechanism of inhibition of SI viruses that acts at a stage after virus entry.

A great deal of interest in the study of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pathogenesis has been generated in recent years by the discoveries of chemokines and HIV type 1 (HIV-1) coreceptors (reviewed in reference 1). Identification of CCR5, the coreceptor for macrophage-tropic or non-syncytium-inducing (NSI) strains of HIV-1 came from the initial studies of two HIV-1-exposed but uninfected (EU) subjects whose CD4+ lymphocytes remained resistant to NSI isolates of HIV-1 (21). Further studies with these cells have shown that high levels of RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), and MIP-1β, the ligands for CCR5, and a mutant CCR5 gene expression were together responsible for resistance against NSI viruses (7, 15). Fusin, or CXCR4, the coreceptor for T-cell-tropic or syncytium-inducing (SI) strains of HIV-1, was identified soon after the discovery of CCR5 (8). Stromal-derived factor SDF-1 was reported as the ligand for CXCR4 and was shown to be able to block infections with SI viruses in vitro (2). Studies on large cohorts have demonstrated that a homozygous deletion of the CCR5 gene is protective against HIV-1 disease progression primarily through resistance to NSI viruses (31). Conflicting reports showing protection (35) or enhancement (19) of HIV-1 disease progression as a result of SDF-1 mutation have also been published. Although other chemokines/lymphokines such as macrophage-derived chemokine have also been shown to inhibit HIV-1 to some extent, the ligands for CCR5 and CXCR4 are the only factors known to have any real significance in preventing HIV-1 disease progression in vivo (36). However, several studies have indicated evidence of other, as-yet-unknown, cellular factors that may play important roles in suppressing HIV infections (16, 18).

There are conflicting reports as to whether CD4+ T cells can be differentially affected in HIV infection. Although some studies have suggested that selective depletion of T cells expressing specific T-cell receptor (TCR)-Vβ sequences occurs in vivo (9, 11), other studies have found no such selective depletion (22, 23). Even though some evidence suggests that the course of HIV-1 infection can depend on genetic loci linked to major histocompatibility complex (HLA in humans) genes (13), no study thus far has shown whether different CD4+ cells from an individual patient can respond differently to HIV infection. Cytokines can also play very complex roles in the regulation of HIV replication. We and others have shown that endogenous production of β-chemokines by CD4+ T cells from asymptomatic HIV-infected subjects can suppress HIV replication (14, 25). However, β-chemokines act only at the virus entry level by blocking the binding of viruses to CCR5 and cannot inhibit virus replication once the virus enters the cell. Furthermore, β-chemokines are not effective against SI viruses (1).

A major barrier to studies of the functions of human T cells in HIV-infected patients has been the limited growth capacity of these cells in vitro. In recent years, herpesvirus saimiri (HVS) has been used as a powerful tool to immortalize and study human T cells (reviewed in reference 17). We have shown that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from HIV-1-positive patients whose infection is nonprogressive and AIDS patients can also be immortalized by HVS for long-term study (27, 28). We report here studies of multiple CD4+ T-cell clones developed from a single HIV-1-positive patient whose infection is nonprogressive. Although phenotypically similar, the response of these CD4+ clones is drastically different when both are infected in vitro with SI viruses. While some clones were highly susceptible to SI viruses, other clones were resistant to infection. We also provide evidence that the resistance to SI viruses in the selected CD4+ clones occurred at a stage after virus entry. Finally, we show that the resistance against SI viruses is mediated, at least partially, by soluble factors produced by the resistant cells that may not include the ligand SDF-1 or other known cytokines.

Generation of CD4+ T-cell clones from a patient whose HIV-1 infection is nonprogressive.

Descriptions of HIV-infected patients and the development of T-cell clones have been previously reported (27, 28). The CD4+ clones studied here were developed from a single patient with nonprogressing HIV-1 infection (NP1) who has remained HIV-1 positive since 1983, displaying no symptoms and maintaining a stable CD4+ T-cell count of greater than 1,000 per μl, without any antiretroviral therapy (28). At the time these clones were generated, NP1’s viral load was not detectable. Development of these clones has been described previously (27, 28). Briefly, peripheral blood lymphocytes were isolated from heparinized blood by using a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.). Lymphocytes were separated with a plastic adherent for 2 h and were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (all from Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.), and human interleukin-2 (IL-2) (20 units/ml) (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). RO 31-8959, a HIV-1 protease inhibitor (a generous gift of I. Duncan), was also added to the medium (final concentration, 10−5 mM) to inhibit HIV-1 spread during immortalization (24). Cells were immediately infected with HVS group C strain 488-77 (a gift from R. C. Desrosiers, Harvard Medical School) at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1. At 3 to 5 days after infection, HVS-infected cells were cloned by seeding at 0.5 to 1 cell/well containing 105 X-irradiated allogeneic peripheral blood lymphocytes from normal donors in 96-well plates containing 200 μl of the above medium. The protease inhibitor was maintained in the medium for the initial 3 weeks of the cloning process. The growing clones were expanded without any further stimulation with antigen/mitogen. MHCD4, an HVS-immortalized CD4+ clone from an HIV-negative donor (26, 30), and the CD4+ clones derived from an AIDS patient (27) examined in this report have also been previously described.

Immunophenotyping of the T-cell clones was performed on single-cell suspensions on a FACScan cytofluorograph (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.), as previously described (30). The monoclonal antibodies used in this study for phenotyping the T-cell clones were also previously described (30). These include fluorescein isothiocyanate- or phosphatidylethanolamine-labeled OKT4 (anti-CD4), OKT3 (anti-CD3), anti-CD2, anti-CD14, anti-CD20, Tac (anti-CD25) (all from Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.), BMA-031 (anti-TCR-αβ), and anti-CD69 (both from Becton Dickinson). Supernatants from different CD4+ clones were tested for production of different cytokines, including IL-4, -6, -10, -12, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interferon alpha (IFN-α), and IFN-γ, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) by using commercial kits as previously described (30). Supernatants were collected from uninfected or infected clones 4 to 7 days postinfection (p.i.) and assayed for cytokines.

By and large, all HVS-immortalized CD4+ T-cell clones that were developed from NP1 maintained activated T-cell phenotypes that were very similar to HVS-immortalized CD4+ clones from uninfected donors that we (30) and others (reviewed in reference 17) have described. As summarized in Table 1, all CD4+ clones developed from NP1 had surface phenotypes consistent with activated CD4+ T cells. Also, all of these clones expressed TCRs of the αβ-phenotype. PCR amplification with pairs of primers complementary to the 26 known TCR-Vβ sequences has revealed exclusive usage of specific Vβ in some of these and other CD4+ clones developed from HIV-infected subjects, indicating the monoclonality of these T-cell clones (reference 28 and unpublished observation). We have not observed preference for any specific TCR-Vβ expansion in the T-cell clones from either uninfected donors (30) or HIV-1 infected subjects (28), suggesting that HVS does not act as a superantigen to immortalize T cells. Also, like CD4+ clones from uninfected donors (17, 30), all HVS-immortalized CD4+ clones from NP1 expressed the Th1 phenotype, i.e., producing IFN-γ but not IL-4 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypes of different CD4+ clones from NP1a

| Molecule | Expression |

|---|---|

| CD2 | + |

| CD3 | + |

| CD4 | + |

| CD8 | − |

| CD14 | − |

| CD20 | − |

| CD25 | + |

| CD69 | + |

| HLA-DR | + |

| TCRα/β | + |

| IFN-γ | + |

| IL-4 | − |

| p24 (HIV-1) | − |

| HIV-1 DNA | − |

These data are from FACS analyses, ELISAs (for IFN-γ, IL-4, and HIV-1 p24), and PCRs (for HIV-1 DNA) of five NP1 clones as described in the text, with appropriate positive and negative controls.

As the CD4+ clones used in this study were developed from an HIV-infected patient, we tested these clones for the presence of HIV-1. None of the five CD4+ clones from NP1 studied here produced any HIV-1 particles as determined by the measurement of p24 core antigen or by coculture with HIV-permissive HeLa-CD4 or SupT1 cells (reference 28 and data not shown). Also, none of these clones was positive for HIV-1 DNA as tested by PCR (Table 1). However, we have occasionally seen immortalized CD4+ clones from HIV-1-positive patients carrying HIV-1 DNA without producing any virus (unpublished observation). We also compared CD4 expression in various clones since, being the primary receptor for HIV-1, the level of CD4 expression may play a critical role in HIV-1 infection. As shown in Fig. 1, all five clones from NP1 expressed high and equivalent levels of CD4 which were comparable to the level of CD4 expressed by HVS-immortalized clones from the uninfected donor (Fig. 1, panel 6). Thus, all five CD4+ clones from NP1 were phenotypically similar, and they resembled CD4+ clones developed from uninfected donors (30).

FIG. 1.

Expression of CD4 in clones from NP1 or MHCD4 cells. Cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-CD4 antibodies or isotype control antibodies (data not shown). 1, NP1-2; 2, NP1-3; 3, NP1-4; 4, NP1-5; 5, NP1-6; 6, MHCD4.

Variable resistance against SI viruses.

We next tested the SI virus infectibility of the CD4+ clones from NP1. Both laboratory and primary isolates of SI viruses were used in this study for infection of CD4+ clones. The laboratory SI strain human T-cell leukemia virus IIIB (IIIB) (donated by R. C. Gallo, University of Maryland) was propagated in H9 cells. Another laboratory SI strain, NL4/3, has been described previously (4). P13, an SI clinical isolate used in this study, has been described previously (33). CD4+ clones were infected with SI viruses at 0.5 pg/cell for 2 h at 37°C, washed two times, and resuspended at 3 × 105 cells/ml in 12-well plates. An HVS-immortalized CD4+ clone (MHCD4) from an uninfected donor which is susceptible to IIIB virus infection was also used as a control (26). Viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion, and supernatants were collected every 3 to 4 days and stored at −80°C. HIV-1 production was measured by p24 ELISA by using a commercial HIV antigen kit (Coulter, Hialeah, Fla.).

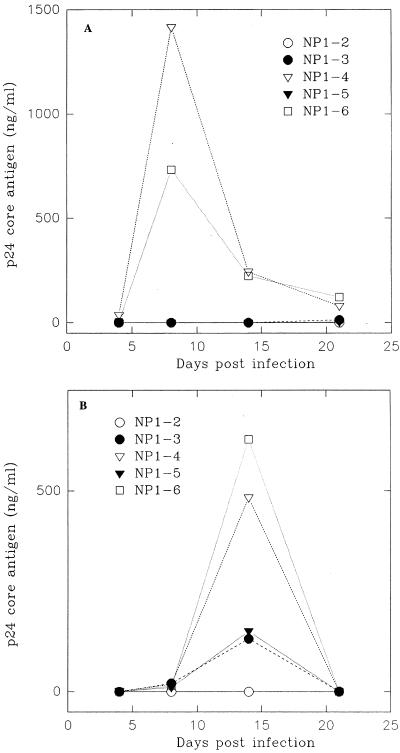

As all of these clones were developed from a single patient expressing equivalent levels of CD4 (Fig. 1), we expected that these clones would be equally infectible by SI viruses. To our surprise, when clinical SI isolate P13 was used for infection, a wide range of susceptibilities was observed among various NP1 clones. As shown in Fig. 2A, while clones NP1-4 and NP1-6 were highly susceptible, producing peak p24 levels of over 1,000 ng/ml, clones NP1-2, NP1-3, and NP1-5 were strongly resistant to infection with P13 viruses. Similar results were obtained when laboratory SI isolate IIIB viruses were used for infection. Clones NP1-4 and NP1-6 again produced high levels of virus, while clones NP1-3 and NP1-5 produced much lower levels of virus, and almost no virus production was detected from clone NP1-2 (Fig. 2B). Increased HIV production was accompanied by cell death in NP1-4 and NP1-6 clones (data not shown). Overall, these data demonstrate that clones NP1-4 and NP1-6 were highly infectible with SI viruses, while clones NP1-2, NP1-3, and NP1-5 were relatively or completely resistant to infection with SI viruses.

FIG. 2.

Infection of NP1 clones by SI viruses. Samples of cells (3 × 105/ml) were infected with P13 or IIIB strains of HIV-1 as described in the text. Culture supernatants were collected at regular intervals and assayed for p24 production. (A) Infection with P13 viruses; (B) infection with IIIB viruses.

HIV-resistance is not at virus entry level.

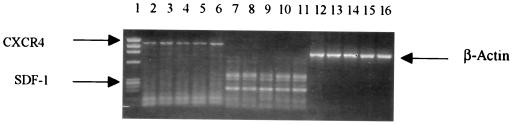

Resistance against NSI viruses in CD4+ cells from EU subjects was found to be at the virus entry level due to mutant CCR5 coreceptor expression (15). We wondered whether a similar mechanism may be involved in the resistance to SI viruses in the NP1 clones, although it must be emphasized that a global defect in the coreceptor is very unlikely in this case, since some of the clones from the same donor were susceptible to infection. We compared the expression of CXCR4 mRNA in resistant as well as susceptible clones from NP1. Expression of CXCR4 and SDF-1 were tested by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) as well as with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) using antibodies 12G5 obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. Cellular mRNA was prepared from an equal number (5 × 106) of cells from each clone by using biotin-labeled oligodeoxyribosylthymine-coated magnetic beads from an mRNA isolation kit (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and was treated with 10 U of RNase-free DNase (Boehringer Mannheim). Random, hexamer-primed cDNA was prepared from 50 μg of mRNA from each sample with an RT-PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.), and cDNA was amplified by 37 cycles of PCR at 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min followed by an additional cycle at 72°C for 10 min for completion of polymerization in a 50-μl volume of primers specific for CXCR4, SDF-1β, and β-actin (as internal control). The primers for SDF-1β were generated from the human SDF-1 sequence (accession no. U16752), and primers for CXCR4 have been previously described (15). The upstream and downstream primers (synthesized by Life Technologies) were as follows: CXCR4, 5′-GGCTAAAGCTTGGCCTGAGTGCTCCAGTAGCC and 5′-CGTCCTCGAGCATCTGTGTTAGCTGGAGTG, which yield a 1,112-bp fragment, and SDF-1β, 5′-CGCCAAGGTCGTGGTCGTGC and 5′-GCCCTTCAGATTGTAGCCCGGC, which yield a 182-bp fragment. The β-actin primers have been described previously and yield a 838-bp fragment (28). All samples were run with and without RT to rule out the possibility of any DNA contamination. MHCD4 and SupT1 cells were also used as controls. Amplified products were separated on a 1.2% agarose gel in the presence of 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml and were photographed. In some experiments, mRNA was collected 2 to 3 days after infection with HIV to test whether SDF-1 may be induced after infection. No significant difference in the levels of CXCR4 mRNA expression was observed among susceptible (e.g., NP1-6) or resistant (e.g., NP1-3) clones from NP1 (Fig. 3). HVS-immortalized and SI-susceptible CD4+ clones from the uninfected donor (MHCD4) or from the AIDS patient (AD1-13 and AD1-22) (27) also expressed comparable levels of CXCR4 mRNA (Fig. 3). Indeed, using anti-CXCR4 antibody, we did not find any difference in the expression of CXCR4 in several resistant or susceptible CD4+ clones by FACS analysis, and all of these clones expressed high and comparable levels of CXCR4 (unpublished observation). These results demonstrate that coreceptor CXCR4 may not contribute to the difference in infection observed in various NP1 clones. We further tested whether the resistant and susceptible clones from NP1 produced different levels of SDF-1. As shown in Fig. 3, both resistant (NP1-6) and susceptible (NP1-3) clones expressed equivalent levels of SDF-1 mRNA, as did the MHCD4 clone from the uninfected donor and SI-virus-susceptible clones AD1-13 and AD1-22 from the AIDS patient. Indeed, no significant change in SDF-1 production was observed in these or other clones from NP1, even after infection with SI viruses (data not shown). Thus, the resistance to SI viruses in the clones from NP1 may not be mediated at the virus entry level through either the inadequate expression of the coreceptor CXCR4 or by the overproduction of SDF-1.

FIG. 3.

Expression of CXCR4 and SDF-1 in CD4+ clones from a patient with a nonprogressive HIV infection, an AIDS patient, and an uninfected donor. RT-PCR was performed as described in the text with primers specific for CXCR4 (lanes 2 to 6), SDF-1 (lanes 7 to 11), and β-actin (lanes 12 to 16). Lanes contain the following: clones NP1-6 (lanes 2, 7, and 12) and NP1-3 (lanes 3, 8, and 13) from the patient with the nonprogressive infection; clones AD1-13 (lanes 4, 9, and 14) and AD1-22 (lanes 5, 10, and 15) from the AIDS patient; and clone MHCD4 (lanes 6, 11, and 16) from the uninfected donor. No DNA contamination was observed when each sample was run without reverse transcriptase (data not shown).

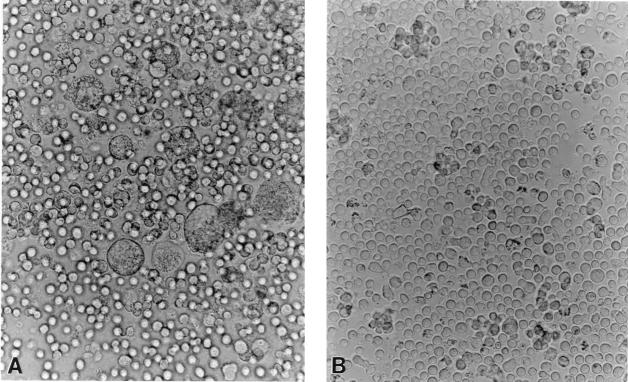

Further evidence that inhibition of the entry of SI viruses in the resistant clones from NP1 may not involve surface receptors comes from the fusion assays. To test whether the CD4+ clones are functional and can efficiently fuse with HIV-1 envelope protein (encoded by the env gene), fusion assays were performed as previously described (12). In this assay system, TF228.1.16, a human B-lymphoid cell line which stably expresses functional HIV env from IIIB virus, is cocultured with CD4-expressing cells for 6 to 12 h. The formation of syncytia in these cocultures indicates env-mediated membrane fusion and suggests that the CD4+ cells have functional receptors and coreceptors for SI viruses. The parental B-lymphoid cell line, BJAB, which does not express env, is used as a negative control in this assay. As shown in Fig. 4 in a representative experiment with one of the resistant NP1-2 clones, efficient fusion took place when these cells were cocultured with TF228.1.16 cells, as is evident by the formation of prominent syncytia (Fig. 4A), whereas no syncytia were formed when the same clone was cocultured with BJAB control cells (Fig. 4B). All other NP1 clones, whether resistant or susceptible to SI viruses (Fig. 2), and clones from uninfected donors were also able to fuse efficiently when cocultured with TF228.1.16 cells, indicating that the resistant clones were competent for the entry of the viruses (not shown).

FIG. 4.

HIV-1 env-mediated membrane fusion of resistant NP1-2 clones. NP1-2 cells were cocultured with TF228.1.16 cells expressing env from IIIB viruses (A) or with BJAB cells as a control (B). Fusion was indicated by the presence of syncytia in panel A.

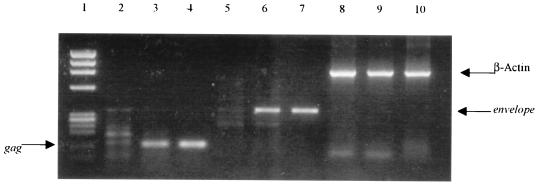

Finally, we also examined the resistant clones for the presence of HIV-1 DNA after nonproductive infection with SI viruses. The capacity of SI viruses to enter the resistant CD4+ clones was further confirmed by the detection of HIV-specific sequences by PCR, as previously described (4). The CD4+ clones which were resistant to SI viruses were infected with DNase-treated IIIB viruses and collected 12 h p.i. The clones were then washed and lysed for 1 h at 60°C in equal volumes of solution A (10 mM Tris [pH 8.3], 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2) and solution B (10 mM Tris [pH 8.3], 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1% Tween 20, 1% Nonidet P-40, 60 μg of proteinase K per ml), followed by incubation at 95°C for 15 min. PCR was performed under standard conditions as described above with primer pairs SK38 and SK39, which amplify the HIV gag region, and BRUV3 and BRUV5 for amplification of the env region (4). The amplified products were run in a 1.2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) and then photographed. For these experiments, IIIB-producing H9 cells and uninfected CD4+ clones were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. In some experiments, resistant clones were tested for the presence of HIV-1 DNA by PCR up to 5 weeks p.i. We demonstrate that although the resistant clones (e.g., NP1-2) did not produce any virus (Fig. 2), these cells became positive for gag (Fig. 5, lane 3) and env (Fig. 5, lane 6) after infection with IIIB viruses, indicating that these viruses could enter the cells, reverse transcribe, and integrate. Indeed, the resistant clones were found to be positive for HIV-1 DNA as long as 5 weeks p.i. with SI viruses (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that the resistance to SI viruses observed in NP1-2, NP1-3, or NP1-5 clones involves a mechanism that acts after virus entry, reverse transcription, and integration.

FIG. 5.

Presence of HIV-1 DNA in NP1-2 clone after infection with IIIB viruses. NP1-2 cells were infected with NL4/3 viruses or kept uninfected as a control. Cellular DNA was isolated after 12 h for PCR amplification with HIV-specific primers for gag (lanes 2 to 4), env (lanes 5 to 7), and β-actin as a control (lanes 8 to 10). Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lanes 2, 5, and 7, uninfected NP1-2; lanes 3, 6, and 9, NP1-2 infected with NL4/3 viruses; lanes 4, 7, and 10, positive controls from chronically infected H9-IIIB cells. HVS-immortalized and HIV-1 CD4+ T cells were used as negative controls for these experiments (data not shown).

HIV-suppression factors.

CD4+ T cells from asymptomatic HIV-infected subjects can protect themselves against NSI viruses by the overproduction of β-chemokines (14, 25). As discussed above, we did not find overexpression of SDF-1, the ligand for CXCR4, in any of the resistant clones (Fig. 3). To test whether the HIV-resistant CD4+ clones were producing any diffusible anti-HIV factors, we made use of a transwell system as previously described (30). In these experiments, cocultures were performed in two-chambered wells separated by a 0.45-μm-pore-size insert (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), so that cells in the upper and lower chambers could not come into direct contact but any soluble factor(s) produced by cells on one side could diffuse and act upon cells on the other side. To rule out HVS-induced factors, HVS-transformed MHCD4 cells, which are highly susceptible to infection with IIIB and NL4/3 viruses and produce high levels of HIV-1, were used as the target (26). MHCD4 cells were infected with NL4/3 viruses, washed, and put in the bottom chamber (105 cells/well), while an equal number of cells from different CD4+ clones from NP1 were put in the upper chamber. Control chambers contained only medium. Supernatants were collected at various time points from the bottom chamber and assayed for p24 production as described above. As summarized in Table 2, HIV production by MHCD4 cells in the bottom chamber was strongly inhibited when either of the resistant clones, NP1-2 or NP1-3, was placed in the upper chamber. Virus production was also inhibited, albeit at a lower level, when the other resistant clone, NP1-5, was put in the upper chamber. In contrast, when either of the two susceptible clones, NP1-4 or NP1-6, was put in the upper chamber, no inhibition of virus production was observed. Indeed, the level of HIV-1 production was enhanced when clone NP1-4 or NP1-6 was put in the upper chamber, probably as a result of the reinfection of these clones. Taken together, these results suggest that soluble factors produced by resistant NP1 clones potently suppress SI viruses at a stage after virus integration. However, whether these antiviral factors are produced constitutively or only after stimulation with HIV-1 remains unclear, as when we directly added supernatants from the resistant clones to NL4/3-infected cells, no significant inhibition of virus production was observed (data not shown), indicating that the production of these suppression factors may be triggered by HIV antigens. However, it is also possible that the HIV suppression factors that are produced constitutively by the resistant clones have short half-lives and that clones need a continuous supply for effective HIV inhibition.

TABLE 2.

Inhibition of HIV production by soluble factors from NP1 clonesa

| Contents of:

|

Resulting level of p24 (ng/ml) | |

|---|---|---|

| Upper chamber | Lower chamber | |

| Medium | MHCD4-NL4/3 | 114.7 |

| NP1-2 | MHCD4-NL4/3 | 9.4 |

| NP1-3 | MHCD4-NL4/3 | 11.9 |

| NP1-4 | MHCD4-NL4/3 | 519 |

| NP1-5 | MHCD4-NL4/3 | 79.4 |

| NP1-6 | MHCD4-NL4/3 | 944 |

MHCD4 cells were infected with NL4/3 virus and put in each of the bottom chambers (105 cells/chamber) in a two-chambered-well experiment as described in the text. Different clones from NP1 were put in the upper chamber (105 cells/chamber) as indicated. Culture supernatants from the bottom chamber were collected 7 days p.i. and assayed for p24 core antigen by ELISA.

Cytokines such as IFN-α have been shown to inhibit HIV replication (32). We tested a panel of known cytokines that may influence the replication of SI viruses. As shown in Table 3, no significant differences in the levels of cytokine expression among the resistant (NP1-2, -3, and -5) or susceptible (NP1-4 and -6) clones were observed before or after infection with SI viruses. All of the clones, whether resistant or susceptible, expressed no IL-4 or IFN-α and little or no IL-10. NP1-3 expressed high levels of IL-6 that further increased after infection. However, NP1-2 and NP1-5 produced levels of IL-6 that were comparable to that of susceptible clones NP1-4 and NP1-6, suggesting that IL-6 may not contribute to resistance in these clones. All of the clones constitutively expressed moderate to high levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ that did not change significantly after infection. However, no definite relationship was observed between the production of these cytokines and resistance or susceptibility to SI viruses. Thus, it appears that none of these cytokines have a role in the SI virus resistance of the selected CD4+ clone.

TABLE 3.

Cytokine production by different CD4+ T-cell clones before and after infection with primary SI virus P13

| Clonea | Level of production ofb:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | IL-6 | IL-10 | IL-12 | TNF-α | IFN-α | IFN-γ | |

| NP1-2 (R) | 0 (0) | 358 (145) | 0 (0) | 0 (66) | 982 (316) | 0 (0) | 4,283 (1,759) |

| NP1-3 (R) | 0 (0) | 3,326 (5,911) | 0 (0) | 107 (85) | 535 (1,850) | 0 (0) | 2,089 (4,593) |

| NP1-4 (S) | 0 (0) | 547 (625) | 0 (28) | 60 (47) | 2,394 (1,787) | 0 (0) | 11,881 (11,609) |

| NP1-5 (R) | 0 (0) | 839 (1,048) | 73 (51) | 0 (0) | 683 (756) | 0 (0) | 8,667 (12,005) |

| NP1-6 (S) | 0 (0) | 485 (438) | 53 (56) | 0 (140) | 1,503 (805) | 0 (0) | 7,650 (3,596) |

Individual clones were either susceptible (S) or resistant (R) to infection with SI viruses as tested in Fig. 2.

Cytokine levels (given in picograms per milliliter) were measured by ELISA, as described in the text. The numbers in parentheses indicate cytokine levels after infection with P13 viruses.

CD4+ lymphocytes can protect themselves against NSI viruses by increased β-chemokine production (7, 14) or expression of mutant CCR5 coreceptor (15, 31). No such resistance to SI viruses in CD4+ cells has been reported to date. By studying different CD4+ clones from an HIV-1-positive patient whose infection was nonprogressive, we demonstrate here that selected CD4+ cells can be resistant to SI viruses. We have found that the resistance to SI viruses of these CD4+ cells is not due to defective coreceptor (CXCR4) expression or the overproduction of SDF-1. Finally, we also provide evidence of a novel mechanism of resistance to SI viruses in these clones that acts at a stage after virus entry and is mediated, at least partially, by soluble factors.

We found that CD4+ clones from NP1 can be selectively resistant or susceptible to infection with SI viruses. While clones NP1-4 and NP1-6 were highly susceptible, clones NP1-2, NP1-3, and NP1-5 were relatively or completely resistant to SI viruses (Fig. 2). Although previous studies have reported that HIV can selectively deplete CD4+ T cells expressing specific TCR-Vβ sequences, this was not due to enhanced HIV replicative ability but rather to possible superantigen-like activity of HIV antigens causing the apoptosis of selected CD4+ cells (11). Establishment of HIV-resistant and -susceptible CD4+ clones from a single patient with a nonprogressive infection indicates that CD4+ cells can react differently to HIV infection in vivo. For several reasons it is not likely that an aberrant molecule induced by HVS-immortalization of NP1 clones was responsible for such resistance to HIV. First, HVS has been a powerful tool for the study of T-cell functions over the past several years (reviewed in reference 17) and HVS-immortalized T cells behave much like primary T lymphocytes (10, 30). By and large, HVS-immortalized T cells remain phenotypically unchanged and maintain their normal functions (17, 28, 30). Thus, there is little evidence of aberrant gene expression in T cells immortalized by HVS. Second, only two viral proteins, with little or no homologies with any known HIV-suppression factors, have thus far been detected in HVS-immortalized T cells (17). Third, we and others have shown that, even in some strains with restricted host ranges, HVS-immortalized T cells are fully permissive for the replication of HIV (20, 26), indicating that there may be no inherent incompatibility between HVS-immortalization and HIV infection. Finally, as clones immortalized by HVS from the same donor were found to be either resistant or susceptible to SI viruses (Fig. 2), factors induced by HVS are unlikely to have played any role in the observed resistance.

In large cohort studies, a mutant CCR5 allele was found to be responsible for the resistance of CD4+ cells to NSI viruses (31). Although no such mutation of the CXCR4 gene has been described so far, we tested and found that all NP1 clones, whether resistant or susceptible to SI viruses, expressed comparable levels of CXCR4 mRNA (Fig. 3) as well as surface antigens (data not shown). All NP1 clones also expressed normal CCR5 genes (25). Other studies have suggested that CXCR4, CCR5 and related CCR3, and CCR2B (3, 6) are probably not the only coreceptors for HIV, and other, as-yet-unidentified, cofactors may also be involved in the pathogenesis of HIV (15, 16, 18). It is unlikely that a global defect (mutation) in coreceptor expression is involved in the resistance of the NP1 clones, as both the resistant and the susceptible clones were developed from a single individual. Further evidence that the resistance to SI viruses was not due to a block at the level of virus entry comes from the fusion assays. Both the resistant and susceptible clones were able to form syncytia efficiently with cells expressing env from IIIB viruses (Fig. 4), indicating that the resistant clones did not have any defect in mediating virus-cell fusion. Additionally, detection of HIV-1 DNA in the resistant clones after nonproductive infection (Fig. 5) suggests that these viruses could enter the cells efficiently and that the block in virus production probably occurred after virus entry and integration. Interestingly, the levels of CD4 expression remained high in these resistant clones even after they became HIV DNA positive (data not shown). Finally, resistant clones like NP1-3 and NP1-5 produced low but detectable levels of virus after infection with some isolates of the SI viruses (Fig. 2B), indicating that these clones were relatively resistant to these viruses and that this incomplete resistance may not be caused by a defect in the virus entry. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that, unlike the previously described CCR5 mutant clones from EU subjects (15), the resistance in clones derived from NP1 involves a mechanism that acts at the postentry level.

Kinter et al. have shown that bulk CD4+ cells from HIV-infected asymptomatic subjects were able to inhibit HIV replication by producing increased levels of β-chemokines (14). Indeed, we have recently reported that all NP1 clones, whether resistant or susceptible to SI viruses, also produced high levels of β-chemokines and were largely resistant to infection with NSI viruses (25). However, β-chemokines can act only against NSI viruses. Also, as discussed above, the mechanism of resistance to SI viruses in NP1 clones probably acts at a stage after virus entry and, thus, may not involve increased ligand (SDF-1) production. However, one can argue that the overproduction of SDF-1 could still inhibit reinfection and thereby eventually suppress virus production. We found no difference in the levels of CXCR4 or SDF-1 expression in the resistant or susceptible clones before (Fig. 4) or after (data not shown) infection with SI viruses. Indeed, CXCR4 and SDF-1 expression in other HVS-transformed and susceptible clones was comparable to that of the NP1 clones (Fig. 4), indicating that resistance in NP1 clones may not involve the decreased expression of CXCR4 coreceptor or the increased production of SDF-1. Furthermore, as demonstrated by our transwell experiments (Table 2), the resistant, and not the susceptible, clones produced soluble factors that could inhibit the production of SI viruses from chronically infected cells, indicating that the antiviral effects of the factors produced by the resistant clones act at a stage after virus integration. Cytokines such as IFN-α have been shown to down regulate HIV replication after de novo infection at a stage prior to integration (32). IL-10 can also inhibit HIV replication in macrophages by inhibiting autocrine production of TNF-α and IL-6 but has no antiviral effects on T cells (34). However, none of these cytokines is known to inhibit HIV replication as strongly as the factors from resistant NP1 clones (e.g., NP1-2 and NP1-3). Additionally, ELISA did not reveal any differences in cytokine (IL-2, -4, -6, -10, and -12, TNF-α, IFN-α and -γ) expression among resistant and susceptible clones before or after infection with SI viruses (Table 3). Thus, the nature of the factor(s) produced by resistant NP1 clones that inhibits SI viruses remains unknown. Several groups have shown that CD8+ cells from HIV-infected subjects produce factors that can inhibit virus replication (14, 16, 18). By using HVS-immortalized cells from an HIV-infected asymptomatic individual, it has recently been shown that soluble factors other than β-chemokines produced by CD8+ cells can suppress HIV (18). We show here for the first time that soluble factors other than known cytokines/chemokines produced by CD4+ T cells from HIV-positive patients with nonprogressive infections can inhibit SI viruses at a stage after virus entry.

In conclusion, this report demonstrates that CD4+ T cells in the same individual can display vastly different responses to infection with SI viruses. We also show that the resistance to SI viruses in selected CD4+ clones is mediated, at least partially, by soluble factors that may not include SDF-1 or other known cytokines. Whether these as-yet-unknown anti-HIV factors produced by some of the CD4+ cells in this patient with a nonprogressive infection were primarily responsible for protection against the advance of HIV-1 disease remains unclear. We have not, as yet, observed similar resistant CD4+ clones from other HIV-positive patients with nonprogressive infections. Further studies with a larger cohort are necessary to conclude whether similar protective roles induced by CD4+ cells also exist in other patients with nonprogressing HIV infections. Nonetheless, our study suggests a novel mechanism of resistance to SI viruses by CD4+ cells in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Bentsman for expert technical assistance and P. Gupta for providing patient samples and valuable suggestions. We thank Christopher Walker for his suggestions and for critically reviewing the manuscript and Scott Cairns, NIAID, NIH, for his encouragement and support with ELISA. We also thank Amy Ott for assisting with the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI 42715 and AI 44974 to K.S. and by the Aaron Diamond Foundation for AIDS Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger E A. HIV entry and tropism: the chemokine receptor connection. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl. A):S3–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleul C C, Farzan M, Choe H, Parolin C, Clark-Lewis I, Sodroski J, Springer T A. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTR/fusin and blocks HIV-1 entry. Nature. 1996;382:829–832. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, et al. The β-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chowdhury I H, Chao W, Potash M J, Sova P, Gendelman H E, Volsky D J. vif-negative human immunodeficiency virus type 1 persistently replicates in primary macrophages, producing attenuated progeny virus. J Virol. 1996;70:5336–5345. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5336-5345.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dittmar M T, McKnight A, Simmons G, Clapham P R, Weiss R A, Simmonds P. HIV-1 tropism and co-receptor use. Nature. 1997;385:495–496. doi: 10.1038/385495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doranz B J, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Samson M, Peiper S C, Parmentier M, Collman R G, Doms R W. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the β-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by chemokine receptor CC-CKR5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng Y, Border C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodara V L, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Grunewald J, Andersson R, Scarlatti G, Esin S, Holmberg V, Libonatti O, Wigzell H. HIV infection leads to differential expression of T-cell receptor Vβ genes in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. AIDS. 1993;7:633–638. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huppes W, Fickenscher H, ’tHart B A, Fleckenstein B. Cytokine dependence of human to mouse graft-versus-host disease. Scand J Immunol. 1994;40:26–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imberti L, Sottini A, Bettinardi A, Puoti M, Primi D. Selective depletion in HIV infection of T cells that bear specific T cell receptor Vβ sequences. Science. 1991;254:860–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1948066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonak Z L, Clark R K, Matour D, Trulli S, Craig R, Henri E, Lee E V, Greig R, Debouck C. A human lymphoid recombinant cell line with functional human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:23–32. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaslow R A, Carrington M, Apple R, Park L, Munoz A, et al. Influence of combinations of human major histocompatibility complex genes on the course of HIV-1 infection. Nat Med. 1996;2:405–411. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinter A L, Ostrowski M, Goletti D, Oliva A, Weissman D, Gantt K, Hardy E, Jackson R, Ehler L, Fauci A S. HIV replication in CD4+ T cells of HIV-infected individuals is regulated by a balance between the viral suppressive effects of endogenous β-chemokines and the viral inductive effects of other endogenous cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14076–14081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu R, Paxton W A, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin S R, Horuk R, MacDonald M E, Stuhlmann H, Koup R A, Landau N R. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackewicz C E, Barker E, Levy J A. Role of β-chemokines in suppressing HIV replication. Science. 1996;274:1393–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meinl E, Hohlfeld R, Wekerle H, Fleckenstein B. Immortalization of human T cells by herpesvirus saimiri. Immunol Today. 1995;16:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moriuchi H, Moriuchi M, Combadiere C, Murphy P M, Fauci A S. CD8+ T-cell-derived soluble factor(s), but not β-chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β, suppress HIV-1 replication in monocyte/macrophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15341–15345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mummidi S, Ahuaja S, Gonzalez E, et al. Genealogy of the CCR5 locus and chemokine system gene variants associated with altered rates of HIV-1 disease progression. Nat Med. 1998;7:786–793. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nick S, Fickenscher H, Biesinger B, Born G, Jahn G, Fleckenstein B. Herpesvirus saimiri transformed human T cell lines—a permissive system for human immunodeficiency viruses. Virology. 1993;194:875–877. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paxton W A, Martin S R, Tse D, O’Brien T R, Skurnick J, Vandevanter N L, Padian N, Braun J F, Kotler D P, Wolinsky S M, Koup R A. Relative resistance to HIV-1 infection of CD4 lymphocytes from persons who remain uninfected despite multiple high-risk sexual exposures. Nat Med. 1996;2:412–417. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Posnett D N, Kabak S, Hodtsev A S, Goldberg E A, Asch A. T-cell antigen receptor Vβ subsets are not preferentially deleted in AIDS. AIDS. 1993;7:625–631. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahadoran P, Rieux-Laucat F, Deist F L, Blanche S, Fischer A, Villartay J P D. Lack of selective Vβ deletion in peripheral CD4+ T cells of human immunodeficiency virus-infected infants. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2041–2044. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts N, Martin J A, Kinchington D, Broadhurst A V, et al. Rational design of peptide-based HIV proteinase inhibitors. Science. 1990;248:358–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2183354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saha K, Bentsman G, Chess L, Volsky D J. Endogenous production of β-chemokines by CD4+, but not CD8+, T-cell clones correlates with the clinical state of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals and may be responsible for blocking infection with non-syncytium-inducing HIV-1 in vitro. J Virol. 1998;72:876–881. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.876-881.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saha K, Caruso M, Volsky D J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection of herpesvirus saimiri (HVS)-immortalized human CD4-positive T lymphoblastoid cells: evidence of enhanced HIV-1 replication and cytopathic effects caused by endogenous IFN-γ. Virology. 1997;1:1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saha K, McKinley G, Volsky D J. Improvement of herpesvirus saimiri T cell immortalization procedure to generate multiple CD4+ T-cell clones from peripheral blood lymphocytes of AIDS patients. J Immunol Methods. 1997;206:21–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saha K, Sova P, Chao W, Chess L, Volsky D J. Generation of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell clones from PBLs of HIV-1 infected subjects using herpesvirus saimiri. Nat Med. 1996;2:1272–1275. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saha K, Volsky D. Are β-chemokines innocent bystanders in HIV type 1 disease progression? AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:1–2. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saha K, Ware R, Yellin M J, Chess L, Lowy I. Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed human CD4+ T cells can provide polyclonal B cell help via the CD40 as well as the TNF-α pathway and through release of lymphokines. J Immunol. 1996;157:3876–3885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Liesnard C, et al. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in Caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996;382:722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shirazi Y, Pitha P M. Alpha interferon inhibits early stages of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication cycle. J Virol. 1992;66:1321–1328. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1321-1328.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sova P, Ranst M V, Gupta P, Balachandran R, Chao W, Itescu S, McKinley G, Volsky D J. Conservation of an intact human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vif gene in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 1995;69:2557–2564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2557-2564.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weissman D, Poli G, Fauci A S. Interleukin 10 blocks HIV replication in macrophages by inhibiting the autocrine loop of tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin 6 induction of virus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:1199–1206. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winkler C, Modi W, Smith M W, et al. Genetic restriction of AIDS pathogenesis by an SDF-1 chemokine gene variant. Science. 1998;279:389–393. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L, He T, Huang Y, Cheng Z, Guo Y, Wu S, Kuntsman K, Clark Brown R, Phair J, Neumann A, Ho D, Wolinsky S. Chemokine coreceptor usage by diverse primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:9307–9312. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9307-9312.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu T, Mo H, Wang N, Nam D S, Cao Y, Koup R A, Ho D D. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 in patients with primary infection. Science. 1993;261:1179–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.8356453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]