Abstract

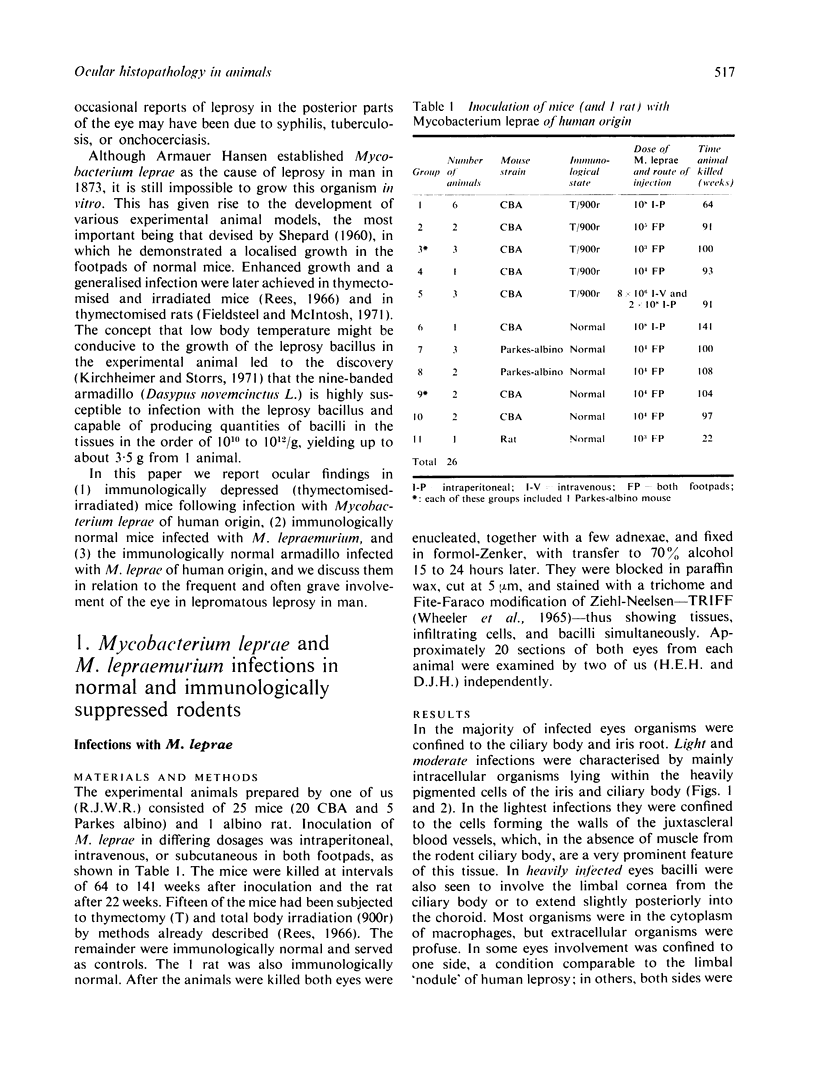

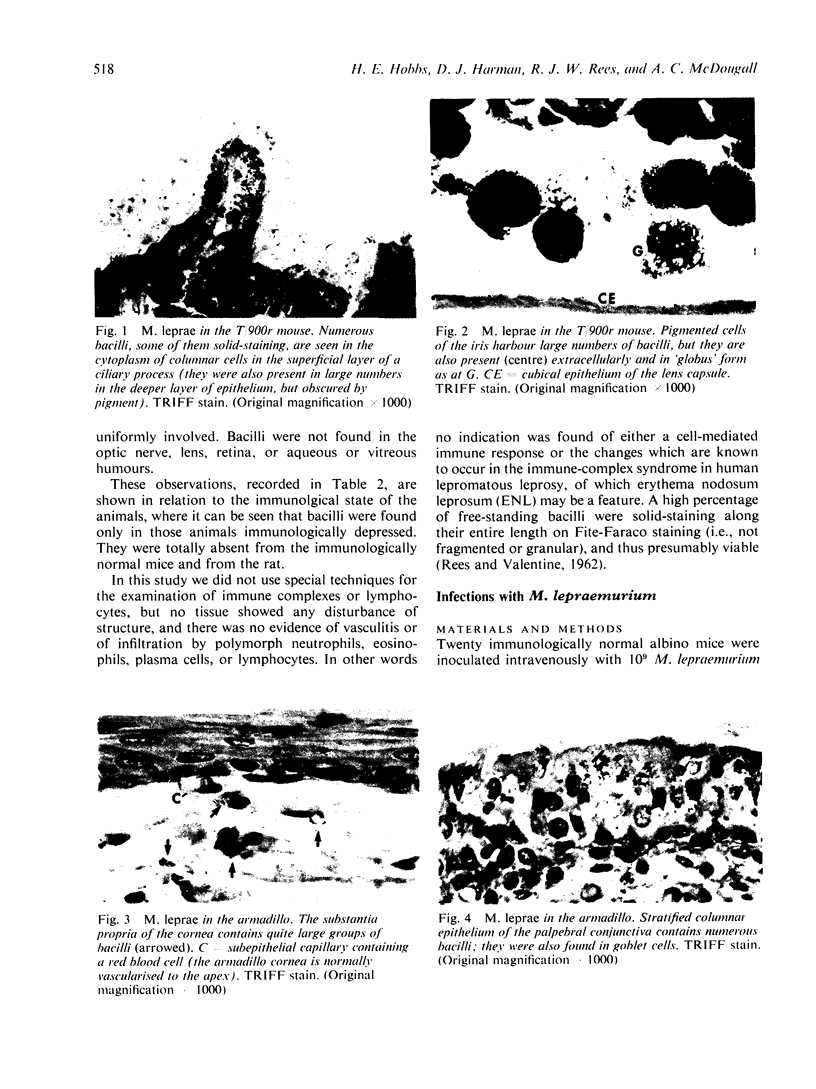

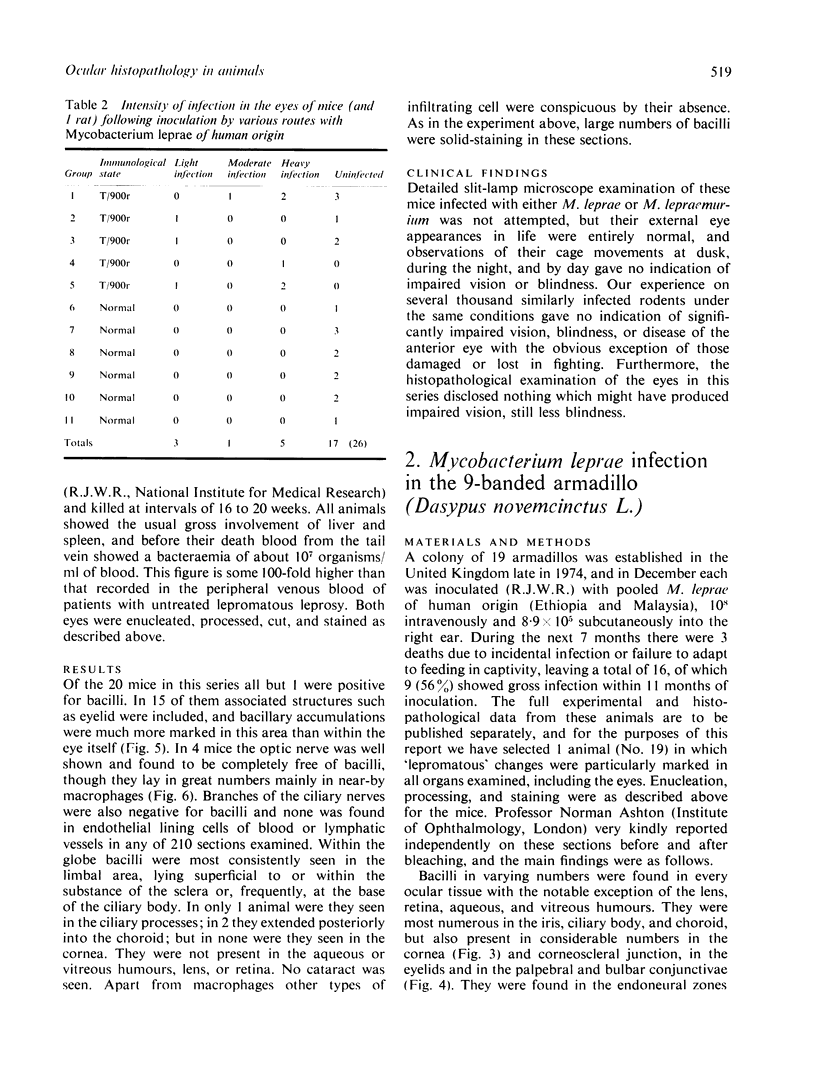

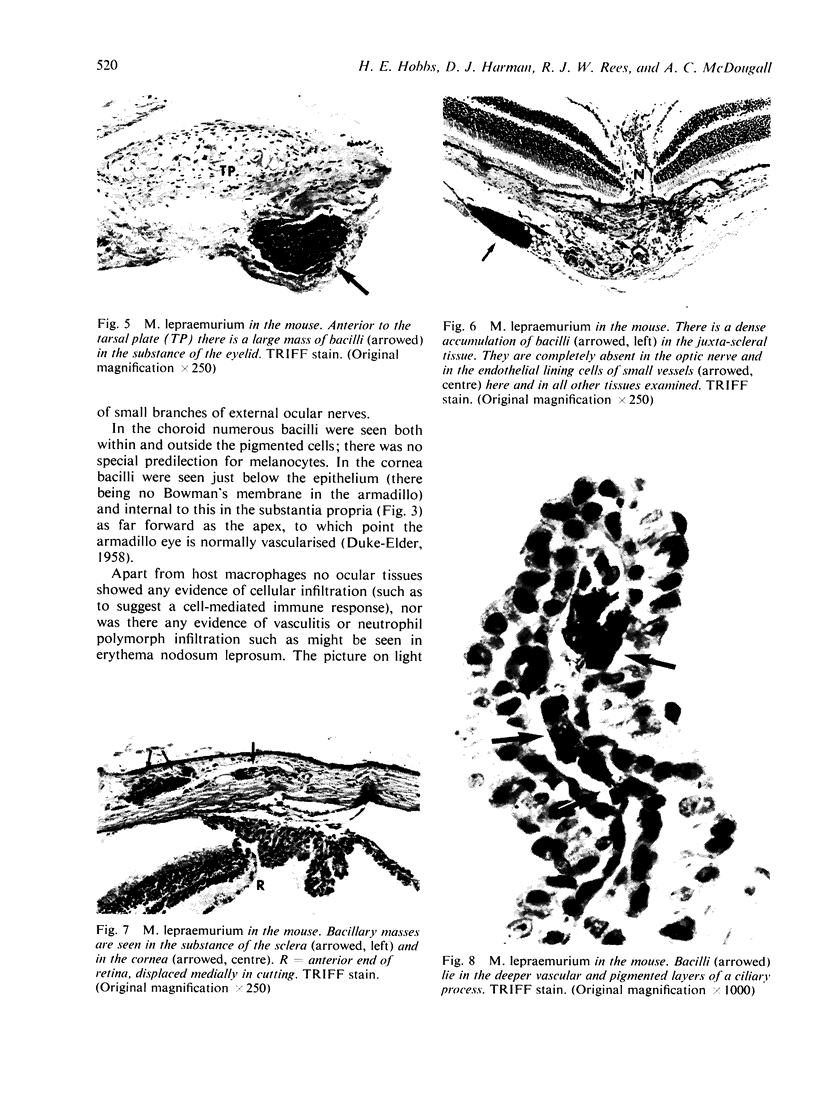

At varying periods of time following the successful establishment of systemic infections with Mycobacterium leprae or M. lepraemurium in the mouse and the nine-banded armadillo eyes were examined by light microscopy. Inoculation of bacilli was by the intravenous or intraperitoneal route or directly into the hind footpads; eyes were not directly inoculated in this study. During periods of up to 3 years under laboratory conditions no animal showed evidence of impaired vision or blindness, and the external appearance of both eyes was normal. The ocular histopathology and the sites of accumulation of bacilli are described. In immunologically normal mice infected with M. lepraemurium bacilli were much commoner in extraorbital tissues, but they were, nevertheless, found in various tissues within the orbit, including the ciliary body and sclera. In immunologically normal mice (and one rat) injected with M. leprae of human origin no bacilli were found in the eye, but in mice immunologically depressed by thymectomy and total body irradiation considerable numbers of bacilli were present in the iris and ciliary body and also in the limbal cornea. In the armadillo bacilli were found in large numbers in virtually all tissues except the lens, retina, optic nerve, and aqueous and vitreous humours, but the uveal tract was heavily involved. Findings are discussed in relation to the great frequency of ocular involvement and the importance of immune-complex disease in patients with lepromatous leprosy, and to factors wihch may favour the localisation and multiplication of Mycobacterium leprae in the eye.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ALLEN J. H., BYERS J. L. The pathology of ocular leprosy. I. Cornea. Arch Ophthalmol. 1960 Aug;64:216–220. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1960.01840010218007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. H. The pathology of ocular leprosy. II. Miliary lepromas of the iris. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966 May;61(5 Pt 2):987–992. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(66)90212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOYCE D. P. Ocular leprosy, with reference to certain cases shown. Proc R Soc Med. 1955 Feb;48(2):108–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Closs O., Haugen O. A. Experimental murine leprosy. 2. Further evidence for varying susceptibility of outbred mice and evaluation of the response of 5 inbred mouse strains to infection with Mycobacterium lepraemurium. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1974 Jul;82(4):459–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drutz D. J., Chen T. S., Lu W. H. The continuous bacteremia of lepromatous leprosy. N Engl J Med. 1972 Jul 27;287(4):159–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197207272870402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieldsteel A. H., McIntosh A. H. Effect of neonatal thymectomy and antithymocytic serum on susceptibility of rats to mycobacterium leprae infection. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1971 Nov;138(2):408–413. doi: 10.3181/00379727-138-35908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANKS J. H., BACKERMAN T. The tissue sites most favorable for the development of murine leprosy in rats and mice. Int J Lepr. 1950 Apr-Jun;18(2):185–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASHIZUME H., SHIONUMA E. ELECTRON MICROSCOPIC STUDY OF LEPROMATOUS CHANGES IN THE IRIS. Int J Lepr. 1965 Jan-Mar;33:61–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOBBS H. E. THE DIAGNOSIS OF UVEITIS IN LEPROSY. Lepr Rev. 1963 Oct;34:226–230. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19630034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs H. E., Choyce D. P. The binding lesions of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1971 Jun;42(2):131–137. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19710017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs H. E. Leprotic iritis and blindness. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1972 Oct-Dec;40(4):366–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRWAN E. W. Ocular leprosy. Proc R Soc Med. 1955 Feb;48(2):112–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchheimer W. F., Storrs E. E. Attempts to establish the armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus Linn.) as a model for the study of leprosy. I. Report of lepromatoid leprosy in an experimentally infected armadillo. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1971 Jul-Sep;39(3):693–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWE J. Leprous affection of the eyes. Proc R Soc Med. 1955 Feb;48(2):107–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manja K. S., Bedi B. M., Kasturi G., Kirchheimer W. F., Balasubrahmanyan M. Demonstration of Mycobacterium leprae and its viability in the peripheral blood of leprosy patients. Lepr Rev. 1972 Dec;43(4):181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran K., Kirchheimer W. F. Use of 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylalanine Oxidation in the Identification of Mycobacterium leprae. J Bacteriol. 1966 Oct;92(4):1267–1268. doi: 10.1128/jb.92.4.1267-1268.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purtilo D. T., Walsh G. P., Storrs E. E., Banks I. S. Impact of cool temperatures on transformation of human and armadilio lymphocytes (Dasypus novemcinctus, Linn.) as related to leprosy. Nature. 1974 Mar 29;248(447):450–452. doi: 10.1038/248450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REES R. J., VALENTINE R. C. The appearance of dead leprosy bacilli by light and electron microscopy. Int J Lepr. 1962 Jan-Mar;30:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea T. H., Levan N. E. Erythema nodosum leprosum in a general hospital. Arch Dermatol. 1975 Dec;111(12):1575–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees R. J. Enhanced susceptibility of thymectomized and irradiated mice to infection with Mycobacterium leprae. Nature. 1966 Aug 6;211(5049):657–658. doi: 10.1038/211657a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARTZ B. ENVIRONMENTAL TEMPERATURE AND THE OCULAR TEMPERATURE GRADIENT. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965 Aug;74:237–243. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1965.00970040239022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard C. C. Temperature optimum of Mycobacterium leprae in mice. J Bacteriol. 1965 Nov;90(5):1271–1275. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.5.1271-1275.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHEELER E. A., HAMILTON E. G., HARMAN D. J. AN IMPROVED TECHNIQUE FOR THE HISTOPATHOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS AND CLASSIFICATION OF LEPROSY. Lepr Rev. 1965 Jan;36:37–39. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19650010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]