Abstract

Background

The aging process alters the resting metabolic rate (RMR), but it still accounts for 50%–70% of the total energy needs. The rising proportion of older adults, especially those over 80 y of age, underpins the need for a simple, rapid method to estimate the energy needs of older adults.

Objectives

This research aimed to generate and validate new RMR equations specifically for older adults and to report their performance and accuracy.

Methods

Data were sourced to form an international dataset of adults aged ≥65 y (n = 1686, 38.5% male) where RMR was measured using the reference method of indirect calorimetry. Multiple regression was used to predict RMR from age (y), sex, weight (kg), and height (cm). Double cross-validation in a randomized, sex-stratified, age-matched 50:50 split and leave one out cross-validation were performed. The newly generated prediction equations were compared with the existing commonly used equations.

Results

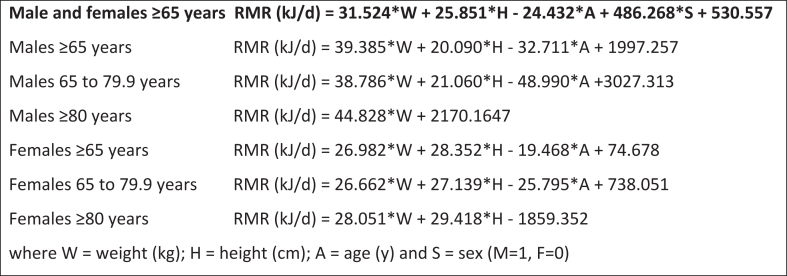

The new prediction equation for males and females aged ≥65 y had an overall improved performance, albeit marginally, when compared with the existing equations. It is described as follows: RMR (kJ/d) = 31.524 × W (kg) + 25.851 × H (cm) − 24.432 × Age (y) + 486.268 × Sex (M = 1, F = 0) + 530.557. Equations stratified by age (65–79.9 y and >80 y) and sex are also provided. The newly created equation estimates RMR within a population mean prediction bias of ∼50 kJ/d (∼1%) for those aged ≥65 y. Accuracy was reduced in adults aged ≥80 y (∼100 kJ/d, ∼2%) but was still within the clinically acceptable range for both males and females. Limits of agreement indicated a poorer performance at an individual level with 1.96-SD limits of approximately ±25%.

Conclusions

The new equations, using simple measures of weight, height, and age, improved the accuracy in the prediction of RMR in populations in clinical practice. However, no equation performs optimally at the individual level.

Keywords: resting metabolic rate, RMR, prediction, anthropometric measures, older adults

Introduction

The United Nations continues to forecast an increasing size of the aged global population, predicting that adults aged ≥65 y will increase to 1.5 billion persons by 2050 [1]. Projections suggest that by 2050, females will comprise 54% of the population of adults aged ≥65 y, and there will be a higher old-age dependency ratio [1]. This poses a multitude of social and health challenges, and responding to the nutritional needs of this population is a priority. Fundamental to nutritional needs is meeting energy requirements, and where they are not fulfilled or matched, malnutrition (both under- and overnutrition) occurs. As such, the accurate prediction of the energy needs of people at population and individual levels is integral to the development of national nutrition policies and for accuracy in clinical practice. Contemporary analyses are needed to inform national energy recommendations, such as the current review of Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy (the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine) [2] undertaken in the US.

A recent systematic review examined REE predictive equations for adults aged ≥65 y and concluded that although widely used, heterogeneity was large and the agreement between the existing 201 different equations was low, with ICC = 0.75 (95% CI = 0.69, 0.81) [3]. A potential reason for some of this known variation is that data from a limited number of older adults contributed to the development of these existing equations, mainly extrapolated from younger adults. For example, there were only 15 males and 18 males aged 65–79 y who contributed to the development of the Mifflin equation [4]; no participants were aged ≥80 y. There was no age stratification reported in the datasets used to develop the equations of Livingston [5] (n = 655; males = 299, females = 356; mean age ± SD: males = 36 ± 15 y, females = 39 ± 13 y) or Ikeda [6] (n = 68; males: n = 39; females: n = 29; mean age ± SD: males = 58.3 ± 10.3 y; females = 61.8 ± 12.2 y). Another recently published review reported similar results where the Mifflin equation showed the smallest mean bias in estimating group-level energy requirements. In comparison, the Harris–Benedict equations had the best precision in estimating the requirements of individuals [7].

In adulthood, the metabolic rate at rest accounts for 50%–70% of the total energy needs and the major determinant of variation is individual body size and a proportional relationship to fat mass and FFM [8]. The largest variation in TEE on a daily basis is attributable to voluntary physical activity, which falls with advancing years, clearly shown by Pontzer et al. who explored life course changes in daily energy expenditure [9]. As the body ages, there is a decline in both the metabolic rate and TEE, which may be related to reduced physical abilities combined with age-related declines in organ metabolism and possibly the brain [10,11]. However, the assumption that the metabolic rate increases in a stable and predictable manner over time is challenged by the deviations in the power-law relationship elucidated by Pontzer et al., whose analysis of energy expenditure through the life course points clearly to the need of further understanding of energy needs in the growing population of older adults [9].

As larger proportions of populations not only live longer but stay healthy and active for longer, consideration needs to be given to the differing REE across the aging continuum [12]. A recent analysis conducted utilizing RMR data of 988 participants identified that the Mifflin [4], Livingston [5], and Ikeda [6] equations are most closely in agreement with measured RMR in all adults aged ≥65 y, and also in subgroup analyses undertaken in the 65–79-y and ≥80-y age groups [13]. Although all 3 equations showed proportional bias, the Mifflin equation had the lowest mean difference across the ≥65-y age cohort, while the Livingston equation showed the least proportional bias in the 65–79-y age group [13]. The analysis of larger data sets may yield equations that provide more accurate estimates of RMR than those currently in use.

The primary aim of this research was to generate and validate new RMR equations for both males and females for older adults and to predict both the performance and accuracy of the new equations.

Methods

This research was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (27291). The analysis was undertaken from the dataset compiled from a systematic search conducted in 2016 [12,13], and updated in 2020 using the same systematic methods. The dataset was developed through identification of papers describing the original measured TEE data using DLW in adults aged ≥65 y. The health status of individuals may influence the metabolic rate, and therefore, studies involving participants with diseases likely to affect energy expenditure (chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and those in intensive care) were ineligible. The authors of these studies were contacted by our research team and were requested to share these data. Variables requested from each published study (where available) were as follows: age (y), sex, weight (kg), height (m), country of data collection, race/ethnicity, TEE (kJ/d), duration of study (d), total body water (TBW, kg), fat mass (kg), FFM (kg), and RMR (kJ/d) including the method used (e.g., indirect calorimetry).

Quality assessments of studies added since the initial database was established (2016 to December 2020) and data from 1 study undertaken during 2018–2019 by our research team [[14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]] were completed in duplicate using the Quality Criteria Checklist for Primary Research (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; review-flow diagram and quality assessments included in Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Using the same process previously used [13], these studies were assessed against statements that consider the quality of the RMR and DLW methods used by researchers (findings included in Supplemental Table 1). The TEE data were not utilized in this analysis, and therefore, the database was cleaned to remove studies where RMR was not directly measured and to remove other ineligible studies.

The integrated dataset included 2127 participants from 39 studies [[14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]] of TEE data from adults aged ≥65 y. Data were checked for quality assurance with particular attention on typographical or transposition errors, missing data (RMR not directly measured, n = 420), noncompliance with age criteria (n = 15), and data that were considered physiologically implausible (n = 2, abnormally high TEE or RMR). An additional small study (n = 4) was excluded as the data were from a population (Hadza hunter gatherers) with known increased metabolic requirements [53]. Potential outliers were assessed using the generalized extreme Studentized deviate (ESD) procedure with an alpha set at 0.05 [54]; none was found. The final dataset consisted of 1686 individuals.

Anthropometric predictions of the RMR

Multiple regression was used to predict RMR from anthropometric measurements. The dependent variable was RMR and independent (predictor) variables were age (y), weight, (kg), height (cm), and sex (coded female = 0, male = 1). Assumptions of normality and constant variance made in multiple regression were checked and met. Multicollinearity between independent variables was assessed by determining the variance inflation factor (VIF); a value of <10 was deemed acceptable. The standard error of the estimate error, calculated as the RMSE, coefficient of determination (R2) values, predictive (adjusted) R2, Akaike information criterion (AIC), Mallow’s C(p), and the PRESS statistic were used to determine the goodness of fit of the regression model. The effect size of regression was assessed using Cohen’s f2 and Cohen’s d for paired correlated samples [55].

A double cross-validation was performed in which a randomized, sex-stratified, age-matched 50:50 split (2% tolerance) of the total sample was carried out (n = 1686; group A = 840, group B = 846) using the allocation module of XL Toolbox (version 7.3.4, available at https://www.xltoolbox.net/) [56]. Equations developed in each group were cross-validated in the opposite group. Covariance analysis and comparison of the slopes and intercepts were used to compare the regression models between the 2 groups, and if not significant, a single equation from the whole sample was also generated with predicted performance assessed using the leave one out cross-validation (LOOCV) procedure (Solverstat 2019 R0; software available at https://solverstat.wordpress.com/) [57] The performance of the new prediction equation was compared with those of published prediction equations for similar populations (Supplemental Table 3).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc v19.8 for Windows (MedCalc Software). Results are expressed as mean and SD except where otherwise indicated. Differences in subject characteristics between sexes were examined by an independent sample t-test for continuous variables and z-test for proportional variables. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Data were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and no data transformations were deemed necessary. Outliers were handled using generalized ESD and Grubbs procedures at an alpha level of 0.05.

Predictive performance of the equations was assessed using Pearson’s correlation, paired sample t-test, Lin’s concordance correlation, residual SD for random differences (Passing–Bablok regression), and Bland–Altman limits of agreement (LOA) analysis. The relative ranking of prediction equations was based on the median absolute percentage error (MAPE) [58] and 2 1-sided t-test (TOST) equivalence analysis for paired data [59]. The TOST procedure measures the minimum percentage difference at which the mean values are considered equivalent and were calculated using the Excel spreadsheet provided by Lakens (available at ==https://files.osf.io/v1/resources/q253c/providers/osfstorage/58455f749ad5a100475fe734?action=download&direct&version=7). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 describes the population from which the new predictive equations were generated. This included a total population of 1686 participants (38.5% were male, n = 650). Males were significantly taller and heavier than females but were not significantly different in either age or BMI. The general characteristics of subjects for the split samples for prediction of RMR are described in Table 2. There were no significant differences in characteristics between the 2 groups for either males or females. Of the papers recently added to the database, all recorded a positive rating during the quality assessment process, except for those by Fassini et al. [38] and Batista et al. [39], which recorded a neutral rating. This was due to reporting of participant selection, which was considered unclear in both studies (Supplemental Table 1). The absence of detail relating to the methods used to determine RMR and in the reporting of the DLW technique was also noted for some of the included studies (Supplemental Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Physical and anthropometric characteristics of participants

| Variable | Males (n = 650) | Females (n = 1036) | P value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 74.0 ± 7.9 (65–101) | 73.9 ± 7.8 (65–99) | 0.11 |

| 72.0 (68–78) | 72 (68–78) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 79.7 ± 15.9 (38.0–144.0) | 66.9 ± 15.7 | <0.01 |

| 78.8 (68.7–90.0) | (56.5–76.0) | ||

| Height (cm) | 172.6 ± 7.7 (145.8–196.0) | 158.8 ± 7.7 (129.0–195.9) | <0.01 |

| 172.9 (168.0–177.7) | 159.0 (153.8–164.0) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 ± 4.4 (14.6–42.5) | 26.4 ± 5.5 (13.6–47.8) | 0.28 |

| 26.3 (23.7–29.4) | 25.5 (22.5–29.8) | ||

| BMI classification Normal (%):overweight (%):obese (%) | 234 (36.0):276 (42.4):140 (21.6) | 481 (46.4):307 (29.6):248 (24.0) | 0.05 |

| RMR (kJ/d)b | 6182 ± 1050 (3380–9627) | 4939 ± 900 (2370–8527) | <0.01 |

| 6192 (5440–6884) | 4848 (4350–5502) |

Values are expressed as means ± SD, range in parenthesis and median, and interquartile range in parentheses.

Differences were analyzed with a 2-sample t-test

TABLE 2.

General characteristics of subjects for the split samples for prediction of RMR

| Variable | Group A (n = 840) |

Group B (n = 846) |

P value1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | ||

| Number (%) | 322 (38.3) | 518 (61.7) | 328 (38.8) | 518 (61.2) | 0.772 |

| Age (y) | 74.1 ± 7.9 | 73.9 ± 7.9 | 73.9 ± 7.8 | 73.9 ± 7.8 | 0.81 |

| 72.0 (68.0–78.0) | 72.0 (68.0–78) | 72.0 (68.0–78) | 72.0 (68.0–78) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 79.7 ± 15.4 | 67.5 ± 16.6 | 79.6 ± 16.5 | 66.3 ± 14.8 | 0.38 |

| 79.2 (69.8–88.7) | 64.7 (56.7–77.0) | 78.6 (68.1–90.6) | 64.0 (56.4–75.5) | ||

| Height (cm) | 172.9 ± 7.5 | 158.7 ± 7.7 | 172.3 ± 7.8 | 158.9 ± 7.8 | 0.87 |

| 172.9 (168.5–178.0) | 159.0 (154.0–164.0) | 172.5 (167.0–177.1) | 159.4 (153.5–164.1) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.5 ± 4.2 | 26.7 ± 5.8 | 26.7 ± 4.6 | 26.2 ± 5.1 | 0.30 |

| 26.2 (24.2–29.0) | 25.7 (22.5–30.2) | 26.5 (23.3–29.8) | 25.2 (22.5–29.1) | ||

| BMI classification Normal (%):overweight (%):obese (%) | 119 (37.0):141 (43.8):62 (19.2) | 228 (44.0):153 (29.5):137 (26.5) | 115 (35.0):135(41.2):78 (23.8) | 253 (48.8):154 (29.8):111 (21.4) | 0.40 |

| RMR (kJ/d) | 6184 ± 990 | 4917 ± 893 | 6181 ± 1106 | 4961 ± 908 | |

| (3439–9627) | (2706–8113) | (3380–9557) | (2370–8527) | ||

| 6204 (5460–6859) | 4812 (4351–5510) | 6141 (5430–6963) | 4876 (4349–5497) | ||

Values are expressed as mean ± SD, range in parenthesis and median, and interquartile range in parentheses.

Differences were analyzed with a 2-sample t-test, group A vs. group B.

z-test for proportions.

Predictive models for RMR for all participants within each split-sample subgroup according to sex are presented in Supplemental Table 4. Age, weight, and height were highly significant (P < 0.01) predictor variables in both males and females. Combining the sexes and incorporating sex as an independent predictor provided the best-performing prediction model (model 6, see Table 3). Model parameters were similar for each of the subgroups, and Mallow’s C(p) values indicated no overfitting as additional values were included in the models with VIF values all being <10, indicating no multicollinearity.

TABLE 3.

Anthropometric predictive models for RMR (kJ/d) in adults aged ≥65 y

| Model | Predictors | Regression coefficient | P value | R2 | Predictive R2 | RMSE (kJ/d) | Cohen’s f2 | Mallow’s C(p) | PRESS (×10−6) | Akaike information criterion (×10−3) | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (n = 1686; 1036 F, 650 M) | |||||||||||

| Model 6 | Weight + | 31.5239 | <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 |

0.679 | 0.678 | 643.7 | 2.1 | 5 | 701.1 | 21.8 | 1.62 1.14 1.84 2.45 |

| Age + | −24.4321 | ||||||||||

| Sex + | 486.2679 | ||||||||||

| Height + | 25.8514 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 530.5571 | ||||||||||

| Participants aged 65–79.9 y (n = 1331; 813 F, 518 M) | |||||||||||

| Model 6 | Weight + | 31.1874 | <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 |

0.675 | 0.672 | 619.6 | 2.1 | 5 | 513.2 | 17.1 | 1.46 1.05 1.82 2.29 |

| Age + | −34.9291 | ||||||||||

| Sex + | 541.8490 | ||||||||||

| Height + | 26.2607 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 1208.8620 | ||||||||||

| Participants aged ≥80 y (n = 355; 223 F, 132 M) | |||||||||||

| Model 6 | Weight + | 33.7169 | <0.01 0.45 <0.01 <0.01 |

0.564 | 0.551 | 701.1 | 1.3 | 5 | 177.5 | 4.66 | 1.82 1.04 1.93 2.69 |

| Age + | 5.5264 | ||||||||||

| Sex + | 278.3871 | ||||||||||

| Height + | 22.7031 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −1630.6503 | ||||||||||

| Model 6a | Weight + | 33.3145 | <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 |

0.564 | 0.553 | 700.7 | 1.3 | 4 | 176.6 | 4.65 | 1.77 1.91 2.69 |

| Sex + | 286.3431 | ||||||||||

| Height + | 22.7297 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −1133.3431 | ||||||||||

Weight (kg); sex (M = 1, F = 0); height (cm), age (y); R2, coefficient of determination; VIF, variance inflation factor.

Results for model 6, which incorporates all predictor variables (weight, height, age, and sex) for all participants are presented in Table 3. This model provided good predictive performance [60] as judged by the strong coefficient of determination and adjusted (predictive) R2 (0.679) and the RMSE (643.7 kJ/d).

Since RMR varied curvilinearly with age but could be well represented by separate linear regressions for those aged 65–79.9 y and those above 80 y of age (Supplemental Figure 2), model 6 regressions were applied separately to these participant groups. The coefficient of determinations decreased slightly, particularly in those aged ≥80 y, but remained moderate to good (Table 3). Age was no longer a significant predictor in this age cohort, and the results for the alternative model not including age (Model 6a) are also presented.

Outcomes of crossvalidation of prediction model 6 are presented in Table 4 and Supplemental Figures 2A–C, with comparison to published prediction equations in Supplemental Figures 3A–D. The predicted RMR was strongly correlated with the measured RMR (rp > 0.7); concordance correlation coefficients were similar to Pearson’s linear regression coefficients, indicating no systematic bias and good agreement between the predicted and measured values. This is supported by small population mean prediction biases: ∼50 kJ/d (∼1%) in those aged under 80 and approximately doubling to 100 kJ/d (∼2%) in the older age group. However, 95% (1.96 SD) limits of agreement were large approximately ±25% for all groups, suggesting that predictive performance was relatively poor in an individual.

TABLE 4.

Validation of prediction equations for RMR (kJ/d) in adults aged ≥65 y

| Prediction group | Validation group | Mean ± SD (kJ/d) | Bias1 (kJ/d ± SD) | Limits of agreement (kJ/d) | Cohen’s d effect size | rp | rc | RSD (kJ/d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (n = 1686; 1036 F, 650 M) | ||||||||

| Reference RMR (kJ/d) | Group B | 5433 ± 1154 | ||||||

| Prediction model 6 Group A (n = 840) |

Group B (n = 846) | 5384 ± 9222 | 50 ± 50 | −1252 (25.4%) to 1352 (24.2%) |

0.079 | 0.818 | 0.797 | 439 |

| Reference RMR (kJ/d) | Group A | 5402 ± 1117 | ||||||

| Prediction model 6 Group B (n = 846) |

Group A (n = 840) | 5457 ± 9543 | −55 ± 54 | −1289 (26.6%) to 1180 (21.9%) |

0.090 | 0.826 | 0.815 | 427 |

| Participants aged 65–79.9 y (n = 1331; 813 F, 518 M) | ||||||||

| Reference RMR (kJ/d) | Group B | 5603 ± 1110 | ||||||

| Prediction model 6 Group A (n = 657) |

Group B (n = 674) | 5567 ± 889 | 36 ± 48 | −1207 (22.7%) to 1277 (22.8%) |

0.060 | 0.821 | 0.801 | 508 |

| Reference RMR (kJ/d) | Group A | 5600 ± 1059 | ||||||

| Prediction model 6 Group B (n = 674) |

Group A (n = 657) | 5642 ± 898 | −42 ± 47 | −1248 (25.5%) to 1164 (21.6%) |

0.071 | 0.815 | 0.803 | 521 |

| Participants aged ≥80 y (n = 355; 223 F, 132 M) – model 6 | ||||||||

| Reference RMR (kJ/d) | Group B | 4772 ± 1086 | ||||||

| Prediction model 6 Group A (n = 183) |

Group B (n = 172) | 4669 ± 773 | 103 ± 114 | −1389 (27.9.0%) to 1595 (28.1%) |

0.144 | 0.713 | 0.670 | 543 |

| Reference RMR (kJ/d) | Group A | 4693 ± 1029 | ||||||

| Prediction model 6 Group B (n = 172) |

Group A (n = 183) | 4789 ± 8292 | −96 ± 93 | −1351 (29.0%) to 1159 (21.5%) |

0.156 | 0.783 | 0.761 | 517 |

| Participants aged ≥80 y (n = 355; 223 F, 132 M) – model 6a | ||||||||

| Reference RMR (kJ/d) | Group B | 4772 ± 1086 | ||||||

| Prediction model 6a Group A (n = 183) |

Group B (n = 172) | 4669 ± 764 | 103 ± 114 | −1381 (27.8.0%) to 1588 (27.9%) |

0.146 | 0.717 | 0.670 | 534 |

| Reference RMR (kJ/d) | Group A | 4693 ± 1029 | ||||||

| Prediction model 6a Group B (n = 172) |

Group A (n = 183) | 4789 ± 8282 | −96 ± 93 | −1351 (28.9%) to 1158 (21.5%) |

0.156 | 0.783 | 0.761 | 516 |

2P < 0.05.

3P < 0.01 (paired t-test).

Reference-predicted; rp, Pearson correlation coefficient; rc, concordance correlation coefficient; RSD, residual standard error; significance of difference with reference value.

The final prediction equations for males and females aged ≥65 y are shown in Figure 1. The first equation is for use across mixed age and sex populations, but the age- and sex-specific equations are likely more accurate for specific groups and individual-level use.

FIGURE 1.

RMR prediction equations for males and females aged ≥65 y.

Prediction equations stratified by age strata and sex are available in Supplemental Tables 5 and 6. Predictive performance was generally poorer for males than females. This may reflect the much smaller numbers of males than females, especially in the ≥80-y age group.

Table 5 presents a comparison of the newly generated prediction equation with the previously published prediction equations, including those known to be the most accurate for this age group [11]. Population mean bias varied from −238 kJ/d to 69.3 kJ/d for published predictors compared with ∼50 kJ/d observed for the new prediction equation (Table 3). Limits of agreement were generally slightly smaller than those observed for the existing equations. The overall performance of the new predictor was improved, albeit marginally, compared to other prediction equations having the smallest relative SD (RSD; 430 kJ/d) and smallest median percentage error of all equations. The commonly used Harris–Benedict equation [61] was the worst-performing predictor exhibiting the largest LOA and the largest median percentage error.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of prediction equations for RMR (kJ/d) in adults aged ≥65 y

| Prediction model | Validation group | Mean ± SD (kJ/d) | Bias1 (kJ/d ± SD) | Limits of agreement (kJ/d) | Cohen’s d effect size | rp | rc | RSD (kJ/d) | MAPE (%) | TOST (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (n = 1686; 1036 F, 650 M) | ||||||||||

| RMR (kJ/d) | All | 5418 ± 1135 | ||||||||

| Prediction model 6, Table 3 (LOOCV) | All | 5418 ± 935 | 0.0 ± 643 | −1260 (22.8%) to 1260 (22.9%) |

0.000 | 0.824 | 0.809 | 430 | 6.7 | 0.5 |

| Harris and Benedict [61] | All | 5656 ± 10612 | −238 ± 676 | −1562 (32.0%) to 1086 (20.4%) |

0.354 | 0.813 | 0.792 | 475 | 8.0 | 4.9 |

| Ikeda et al. [6] | All | 5416 ± 867 | 1.7 ± 682 | −1335 (27.9%) to 1338 (24.4%) |

0.003 | 0.800 | 0.772 | 435 | 7.2 | 0.6 |

| Livingston et al. [5] | All | 5409 ± 1024 | 9.5 ± 668 | −1300 (26.2%) to 1319 (24.2% |

0.014 | 0.813 | 0.809 | 454 | 6.8 | 0.7 |

| Mifflin et al. [4] | All | 5349 ± 11502 | 69.3 ± 682 | −1268 (25.0%) to 1407 (26.2%) |

0.101 | 0.822 | 0.820 | 483 | 7.4 | 1.8 |

| Participants aged 65–79.9 y (n = 1331; 813 F, 518 M) | ||||||||||

| RMR (kJ/d) | All | 5601 ± 1085 | ||||||||

| Prediction model 6, Table 3 (LOOCV) | All | 5601 ± 891 | 0.0 ± 618 | −1212(22.3%) to 1212 (22.4%) |

0.000 | 0.821 | 0.806 | 414 | 6.3 | 0.5 |

| Harris and Benedict [61] | All | 5847 ± 10212 | −246 ± 656 | −1592 (26.2.0%) to −1040 (18.4%) |

0.376 | 0.807 | 0.784 | 462 | 7.5 | 5.0 |

| Ikeda et al. [6] | All | 5551 ± 8313 | 49 ± 664 | −1252 (22.9%) to 1351 (24.6%) |

0.080 | 0.791 | 0.763 | 426 | 6.7 | 1.5 |

| Livingston et al. [5] | All | 5585 ± 964 | 17 ± 647 | −1223 (23.0%) to 1344 (24.3% |

0.025 | 0.807 | 0.801 | 449 | 6.3 | 0.9 |

| Mifflin et al. [4] | All | 5541 ± 10854 | 61 ± 655 | −1283 (22.7%) to 1407 (26.5%) |

0.092 | 0.818 | 0.816 | 464 | 6.5 | 1.6 |

| Participants aged ≥ 80 y (n = 355; 223 F, 132 M) | ||||||||||

| RMR (kJ/d) | All | 4731 ± 1056 | ||||||||

| Prediction model 6, Table 3 (LOOCV) | All | 4731 ± 794 | 0.0 ± 697 | −1366 (28.0%) to 1366 (28.0%) |

0.000 | 0.751 | 0.722 | 399 | 8.1 | 1.3 |

| Prediction model 6a, Table 3 (LOOCV) | All | 4731 ± 793 | 0.1 ± 698 | −1368 (28.0%) to 1367 (28.0%) |

0.000 | 0.751 | 0.721 | 394 | 7.9 | 1.3 |

| Harris and Benedict [61] | All | 4941 ± 8892 | −210 ± 744 | −1669 (32.8%) to −1249 (24.7%) |

0.288 | 0.720 | 0.693 | 512 | 10.9 | 5.9 |

| Ikeda et al. [6] | All | 4908 ± 8112 | −177 ± 720 | −1588 (32.0%) to 1233 (24.8%) |

0.257 | 0.733 | 0.696 | 480 | 10.1 | 5.1 |

| Livingston et al. [5] | All | 4749 ± 975 | −18 ± 742 | −1473 (30.1%) to 1437(31.0% |

0.024 | 0.736 | 0.733 | 532 | 8.9 | 1.7 |

| Mifflin et al. [4] | All | 4630 ± 11055 | 101 ± 778 | −1423 (29.6%) to 1625 (37.7%) |

0.130 | 0.742 | 0.738 | 556 | 10.7 | 3.6 |

1Reference-predicted; rp, Pearson correlation coefficient; rc, concordance correlation coefficient; RSD, residual SD; MAPE, median absolute percentage error; TOST, 2 1-sided t-test; significance of difference with reference value.

2P<0.0001 (paired t-test).

3P<0.01.

4P<0.001.

5P<0.05.

Discussion

This analysis adds to our understanding of how to predict RMR more accurately for groups of contemporary older adults, with the newly created equation estimating RMR within a population mean prediction bias of ∼50 kJ/d for those aged ≥65 y. Accuracy was decreased in the ≥80-y-old group (100 kJ/d) but was still within the acceptable range for both males and females; in this age group, sex was no longer a significant predictor variable in the model and a simpler equation is also provided not including sex for this age group. Notably, in males aged ≥80 y, RMR could be predicted well by weight alone. This probably reflects the smaller sample size (n = 132) and relatively narrow range in height (169.6 ± 6.9 cm) compared to females (n = 223; 154.3 ± 8.2 cm, respectively).

The new equations adhere to the principle of parsimony that states that the predictive model with the smallest number of variables will perform better than models with a greater number of variables [62]. Furthermore, equations with fewer parameters and simple participant-level variables that are readily available—sex, age, weight, and height [3]—make them easily applicable in practice settings. The ease of use is important as it enables rapid estimation of energy requirements in both clinical and research settings. In addition, these measures support the estimation of energy requirements at a group level for the purposes of modeling nutritional requirements at an international (e.g., reference [63]), national (e.g., reference [64]), or local level (e.g., evaluation of menus in residential care facilities).

The improvements in the prediction of RMR by the new equations over those of alternative previously published equations were modest. Nevertheless, even small improvements in predictive accuracy may be clinically important. For example, where equations underestimate RMR, the subsequent delivery of insufficient energy from food may contribute to the development of malnutrition [65]. Overestimating energy requirements is also undesirable, as the prevalence of being above a healthy weight is increasing in older people [66]. Older people with obesity are at an increased risk of cardiometabolic disease, reduced quality of life, joint pain, and sexual dysfunction [67] in addition to venous leg ulcers [68,69]. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted older adults more than any other age group [70], with excess weight gain further exacerbating the risk of infection and death [71]. Particularly at an individual level, the predictive accuracy of the newly derived equations may be associated with weight loss or gain.

Ensuring that the energy requirements of older adults are accurately calculated is of relevance for those living in situations where they are dependent on an institutional food supply, such as residential aged care facilities. In 2015, 1.3 million people lived in nursing homes in the US [72]. Given the nursing home residents’ dependence on meal provision, with menus predicated by their nutritional needs, accurate guidance that reflects accurately their basal energy needs is essential to ensure that food supply is adequate.

It is worth noting that the limits of agreement for prediction are wide, approximately ±25% irrespective of the predictive model, albeit slightly smaller than those for the previously published equations. This observation indicates that there will be limitations to the accuracy of any current predictive equation at the individual level. The reasons for this are unclear, but it has been suggested that variables such as age, sex, weight, and height alone are inadequate to provide accurate prediction of RMR in an individual. However, there remains opportunity to extend the present study to determine whether the inclusion of other variables improves the predictive ability of equations at an individual or population level. Across all age groups, variables including measures of body composition (e.g., FFM) or characteristics of body habitus, such as ethnicity, are known to impact energy requirements while not being generally considered in predictive equations [3]. The increasing availability of simple field or bedside measurements of FFM, such as bioelectrical impedance analysis using a smartphone [73], render their inclusion feasible in clinical settings. In older adults, functional and biological measures of aging may support future adjustments of predictive equations via corrections in chronological age [74]. However, the hallmarks of biological aging (genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient-sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication) first described by López-Otín et al. [75] and Liu et al. [76] involve expensive laboratory techniques and are therefore not readily accessible in community medical settings. Other body composition measures (including sarcopenia and frailty measures) provide an additional level of complexity in the estimation of energy needs in older adults. Dissecting the relationship between each of these variables and their relative contribution to energy requirements provides opportunities for future research.

As with any study involving population-derived measurement, there are both strengths and limitations that need to be acknowledged. A strength of the present study is that a sufficiently large sample size (n = 1686) was available to support internal validation of the new RMR equation. The fact that this data set was assembled from international data obtained via reference methods further strengthens the broad applicability of the generated equations. Correspondingly, however, using pre-existing data from many different studies precluded coordinated quality control of data collection. In particular, RMR was measured by different methods, albeit all considered clinically acceptable, in the various centers. The removal of approximately 20% of individual datapoints mostly due to the absence of RMR measures is noted as a potential source of bias in the dataset. Additionally, physical activity and fitness levels will be a potential source of variation in the dataset.

It has been recognized that measurement errors for RMR typically exhibit coefficients of variation of 5%–10% [77] with a intraday variation of up to 6% [78]. A potential limitation is the determination of absolute predictive accuracy. Ideally, the generated prediction equations would be tested in a completely independent data set. Such a data set is not available, and hence, the predictive power was assessed using the split-sample approach that with approximately 840 participants per group provides a reliable estimate of predictive accuracy. This is in contrast to the K-means or LOOCV (operationally equivalent to k = 1) approaches, which, albeit providing a good estimate of the error associated with the estimation of the mean, cannot estimate accuracy (the bias) since it uses the same dataset as that used for generating the predicted values. Nonetheless, it provides a basis for the comparison of overall model performance with that of alternative predictive equations (Table 5).

In summary, this research presents new equations for older adults to estimate RMR. By using only simple measures—weight, height, and sex, they can be easily used in practice settings and are improved in accuracy than the currently utilized equations.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of Hannah Thompson who ran the database searches to update the systematic review. We also thank all the authors that were contacted in the completion of this review for their responses, and in many cases, for their contribution of participant-level data for further analysis, the authors appreciate their time and effort spent.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows – JP, KN, ZD, SG, LW, HT: designed the research; KN, ZD: completed quality assessments; LW: analyzed the database; JP, SG, LW, HT: wrote the manuscript; and all authors: contributed to data interpretation, and read and approved the final manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.04.010.

Funding

The WHI program was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, through contracts (HHSN268201600018C, HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201600002C, HHSN268201600003C, HHSN268201600004C, and R01 CA119171).This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors thank the National Cancer Institute for access to NCI's data collected by the Interactive Diet and Activity Tracking in AARP (IDATA) Study. The statements contained herein are solely those of the authors and do not represent or imply concurrence or endorsement by NCI.

Data availability

The data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will not be made available because of the confidentiality clauses contained in the agreements to obtain datasets used in this analysis.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights . Vol. 450. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2020. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd-2020_world_population_ageing_highlights.pdf (Living arrangements of older persons [Internet]). Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy 2022 [Internet] The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine; 2022. http://nap.nationalacademies.org/26818 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ocagli H., Lanera C., Azzolina D., Piras G., Soltanmohammadi R., Gallipoli S., et al. Resting energy expenditure in the elderly: systematic review and comparison of equations in an experimental population. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):458. doi: 10.3390/nu13020458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mifflin M.D., St Jeor S.T., Hill L.A., Scott B.J., Daugherty S.A., Koh Y.O. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990;51(2):241–247. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livingston E.H., Kohlstadt I. Simplified resting metabolic rate-predicting formulas for normal-sized and obese individuals. Obes. Res. 2005;13(7):1255–1262. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikeda K., Fujimoto S., Goto M., Yamada C., Hamasaki A., Ida M., et al. A new equation to estimate basal energy expenditure of patients with diabetes. Clin. Nutr. 2013;32(5):777–782. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cioffi I., Marra M., Pasanisi F., Scalfi L. Prediction of resting energy expenditure in healthy older adults: a systematic review. Clin. Nutr. 2021;40(5):3094–3103. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruen C. Variation of basal metabolic rate per unit surface area with age. J. Gen. Physiol. 1930;13(6):607–616. doi: 10.1085/jgp.13.6.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pontzer H., Yamada Y., Sagayama H., Ainslie P.N., Andersen L.F., Anderson L.J., et al. Daily energy expenditure through the human life course. Science. 2021;373(6556):808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.abe5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts M.E., Pocock R., Claudianos C. Brain energy and oxygen metabolism: emerging role in normal function and disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;11:216. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heymsfield S.B., Thomas D., Bosy-Westphal A., Shen W., Peterson C.M., Müller M.J. Evolving concepts on adjusting human resting energy expenditure measurements for body size. Obes. Rev. 2012;13(11):1001–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01019.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter J., Nguo K., Gibson S., Huggins C.E., Collins J., Kellow N.J., et al. Total energy expenditure in adults aged 65 years and over measured using doubly labelled water: international data availability and opportunities for data sharing. Nutr. J. 2018;17(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter J., Nguo K., Collins J., Kellow N., Huggins C.E., Gibson S., et al. Total energy expenditure measured using doubly labeled water compared with estimated energy requirements in older adults (≥65 y): analysis of primary data. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019;110(6):1353–1361. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prentice A., Leavesley K., Murgatroyd P., Coward W., Schorah C., Bladon P., et al. Is severe wasting in elderly mental patients caused by an excessive energy requirement? Age Ageing. 1989;18(3):158–167. doi: 10.1093/ageing/18.3.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prentice R.L., Mossavar-Rahmani Y., Huang Y., Van Horn L., Beresford S.A.A., Caan B., et al. Evaluation and comparison of food records, recalls, and frequencies for energy and protein assessment by using recovery biomarkers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011;174(5):591–603. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arvidsson D., Slinde F., Nordenson A., Larsson S., Hulthén L. Validity of the ActiReg system in assessing energy requirement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Clin. Nutr. 2006;25(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frisard M.I., Fabre J.M., Russell R.D., King C.M., DeLany J.P., Wood R.H., et al. Physical activity level and physical functionality in nonagenarians compared to individuals aged 60-74 years. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007;62(7):783–788. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tooze J.A., Schoeller D.A., Subar A.F., Kipnis V., Schatzkin A., Troiano R.P. Total daily energy expenditure among middle-aged men and women: the OPEN Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;86(2):382–387. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.2.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hertogh E.M., Monninkhof E.M., Schouten E.G., Peeters P.H., Schuit A.J. Validity of the modified Baecke questionnaire: comparison with energy expenditure according to the doubly labeled water method. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moshfegh A.J., Rhodes D.G., Baer D.J., Murayi T., Clemens J.C., Rumpler W.V., et al. The US Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;88(2):324–332. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choquette S., Chuin A., Lalancette D.A., Brochu M., Dionne I.J. Predicting energy expenditure in elders with the metabolic cost of activities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009;41(10):1915–1920. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a6164a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada Y., Yokoyama K., Noriyasu R., Osaki T., Adachi T., Itoi A., et al. Light-intensity activities are important for estimating physical activity energy expenditure using uniaxial and triaxial accelerometers. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009;105(1):141–152. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothney M.P., Brychta R.J., Meade N.N., Chen K.Y., Buchowski M.S. Validation of the ActiGraph two-regression model for predicting energy expenditure. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010;42(9):1785–1792. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181d5a984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichihara N., Namba K., Ishikawa-Takata K., Sekine K., Takase M., Kamada Y., et al. Energy requirement assessed by doubly labeled water method in patients with advanced amyotrophic lateral sclerosis managed by tracheotomy positive pressure ventilation, Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2012;13(6):544–549. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2012.699968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farooqi N., Slinde F., Håglin L., Sandström T. Validation of SenseWear Armband and ActiHeart monitors for assessments of daily energy expenditure in free-living women with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physiol. Rep. 2013;1(6) doi: 10.1002/phy2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goran M.I., Poehlman E.T. Total energy expenditure and energy requirements in healthy elderly persons. Metabolism. 1992;41(7):744–753. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calabro M.A., Kim Y., Franke W.D., Stewart J.M., Welk G.J. Objective and subjective measurement of energy expenditure in older adults: a doubly labeled water study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;69(7):850–855. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfrimer K., Vilela M., Resende C.M., Scagliusi F.B., Marchini J.S., Lima N.K.C., et al. Under-reporting of food intake and body fatness in independent older people: a doubly labelled water study. Age Ageing. 2015;44(1):103–108. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rollo M.E., Ash S., Lyons-Wall P., Russell A.W. Evaluation of a mobile phone image-based dietary assessment method in adults with type 2 diabetes. Nutrients. 2015;7(6):4897–4910. doi: 10.3390/nu7064897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sridharan S., Wong J., Vilar E., Farrington K. Comparison of energy estimates in chronic kidney disease using doubly labelled water. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016;29(1):59–66. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothenberg E.M. Resting, activity and total energy expenditure at age 91-96 compared to age 73. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2002;6(3):177–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanc S., Schoeller D.A., Bauer D., Danielson M.E., Tylavsky F., Simonsick E.M., et al. Energy requirements in the eighth decade of life. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;79(2):303–310. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neuhouser M.L., Tinker L., Shaw P.A., Schoeller D., Bingham S.A., Van Horn L.V., et al. Use of recovery biomarkers to calibrate nutrient consumption self-reports in the Women’s Health Initiative. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008;167(10):1247–1259. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reilly J.J., Lord A., Bunker V.W., Prentice A.M., Coward W.A., Thomas A.J., et al. Energy balance in healthy elderly women. Br. J. Nutr. 1993;69(1):21–27. doi: 10.1079/bjn19930005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colbert L.H., Matthews C.E., Havighurst T.C., Kim K., Schoeller D.A. Comparative validity of physical activity measures in older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011;43(5):867–876. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181fc7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ostendorf D.M., Caldwell A.E., Creasy S.A., Pan Z., Lyden K., Bergouignan A., et al. Physical activity energy expenditure and total daily energy expenditure in successful weight loss maintainers. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019;27(3):496–504. doi: 10.1002/oby.22373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pullicino E., Coward A., Elia M. Total energy expenditure in intravenously fed patients measured by the doubly labeled water technique. Metabolism. 1993;42(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(93)90172-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fassini P.G., Das S.K., Pfrimer K., Suen V.M.M., Sérgio Marchini J., Ferriolli E. Energy intake in short bowel syndrome: assessment by 24-h dietary recalls compared with the doubly labelled water method. Br. J. Nutr. 2018;119(2):196–201. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517003373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Batista L.D., De França N.A.G., Pfrimer K., Fontanelli M.M., Ferriolli E., Fisberg R.M. Estimating total daily energy requirements in community-dwelling older adults: validity of previous predictive equations and modeling of a new approach. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021;75(1):133–140. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-00717-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X., Bowyer K.P., Porter R.R., Breneman C.B., Custer S.S. Energy expenditure responses to exercise training in older women. Physiol. Rep. 2017;5(15) doi: 10.14814/phy2.13360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishida Y., Nakae S., Yamada Y., Kondo E., Yamaguchi M., Shirato H., et al. Validity of one-day physical activity recall for estimating total energy expenditure in elderly residents at long-term care facilities: CLinical EValuation of Energy Requirements study (CLEVER study) J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2019;65(2):148–156. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.65.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bastone A.C., Ferriolli E., Pfrimer K., Moreira B.S., Diz J.B.M., Dias J.M.D., et al. Energy expenditure in older adults who are frail: a doubly labeled water study. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2019;42(3):E135–E141. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0000000000000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Subar A.F., Potischman N., Dodd K.W., Thompson F.E., Baer D.J., Schoeller D.A., et al. Performance and feasibility of recalls completed using the automated self-administered 24-hour dietary assessment tool in relation to other self-report tools and biomarkers in the Interactive Diet and Activity Tracking in AARP (IDATA) study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020;120(11):1805–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopes de Pontes T., Pinheiro Amador Dos Santos Pessanha F., Freire Junior R.C., Pfrimer K., da Cruz Alves N.M., Fassini P.G., et al. Total energy expenditure and functional status in older adults: a doubly labelled water study. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2021;25(2):201–208. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morino K., Kondo K., Tanaka S., Nishida Y., Nakae S., Yamada Y., et al. Total energy expenditure is comparable between patients with and without diabetes mellitus: Clinical Evaluation of Energy Requirements in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus (CLEVER-DM) study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2019;7(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguo K., Truby H., Porter J. Total energy expenditure in healthy ambulatory older adults aged ≥80 years: a doubly labelled water study. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2023;79(2):95–105. doi: 10.1159/000528872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kashiwazaki H., Dejima Y., Orias-Rivera J., Coward W.A. Energy expenditure determined by the doubly labeled water method in Bolivian Aymara living in a high altitude agropastoral community. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995;62(5):901–910. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koea J.B., Wolfe R.R., Shaw J.H. Total energy expenditure during total parenteral nutrition: ambulatory patients at home versus patients with sepsis in surgical intensive care. Surgery. 1995;118(1):54–62. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pannemans D.L., Westerterp K.R. Energy expenditure, physical activity and basal metabolic rate of elderly subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 1995;73(4):571–581. doi: 10.1079/bjn19950059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothenberg E.M., Bosaeus I.G., Steen B.C. Energy expenditure at age 73 and 78-a five year follow-up. Acta Diabetol. 2003;40(Suppl 1):S134–S138. doi: 10.1007/s00592-003-0046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slinde F., Ellegård L., Grönberg A.M., Larsson S., Rossander-Hulthén L. Total energy expenditure in underweight patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease living at home. Clin. Nutr. 2003;22(2):159–165. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2002.0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hagfors L., Westerterp K., Sköldstam L., Johansson G. Validity of reported energy expenditure and reported intake of energy, protein, sodium and potassium in rheumatoid arthritis patients in a dietary intervention study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;59(2):238–245. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pontzer H., Raichlen D.A., Wood B.M., Mabulla A.Z.P., Racette S.B., Marlowe F.W. Hunter-gatherer energetics and human obesity. PLoS One. 2012;7(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosner B. Percentage points for a generalized ESD many-outlier procedure. Technometrics. 1983;25(2):165–172. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1983.10487848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013;4:863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kraus D. Consolidated data analysis and presentation using an open-source add-in for the Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet software. Medical Writ. 2014;23(1):25–28. doi: 10.1179/2047480613Z.000000000181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Comuzzi C., Polese P., Melchior A., Portanova R., Tolazzi M. SOLVERSTAT: a new utility for multipurpose analysis. An application to the investigation of dioxygenated Co(II) complex formation in dimethylsulfoxide solution. Talanta. 2003;59(1):67–80. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(02)00457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seoane F., Abtahi S., Abtahi F., Ellegård L., Johannsson G., Bosaeus I., et al. Mean expected error in prediction of total body water: a true accuracy comparison between bioimpedance spectroscopy and single frequency regression equations. BioMed. Res. Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/656323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lakens D. Equivalence tests: a practical primer for t tests, correlations, and meta-analyses. Soc. Psychol. Personal Sci. 2017;8(4):355–362. doi: 10.1177/1948550617697177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schober P., Boer C., Schwarte L.A. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018;126(5):1763–1768. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harris J.A., Benedict F., Washington D.C. Carnegie Institution of Washington; Washington: 1919. A biometric study of basal metabolism in man [Internet]https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/chla2905932 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vandekar S., Tao R., Blume J. A robust effect size index. Psychometrika. 2020;85(1):232–246. doi: 10.1007/s11336-020-09698-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Human energy requirements. Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation; Rome: 2001. https://www.fao.org/3/y5686e/y5686e.pdf [Internet] Available from: vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 9th ed. Department of Agriculture and United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 65.White J.V., Guenter P., Jensen G., Malone A., Schofield M., Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group, et al. Consensus statement of the academy of nutrition and dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012;112(5):730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Overweight and obesity in Australia: a birth cohort analysis. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2017. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/overweight-obesity/overweight-obesity-australia-birth-cohort-analysis/summary [Internet] Available from: PHE 215. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salihu H.M., Bonnema S.M., Alio A.P. Obesity: what is an elderly population growing into? Maturitas. 2009;63(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McDaniel J.C., Kemmner K.G., Rusnak S. Nutritional profile of older adults with chronic venous leg ulcers: a pilot study. Geriatr. Nurs. 2015;36(5):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gould L., Fulton A. Wound healing in older adults. R. I. Med. J. 2016;99(2):34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mahase F. Covid-19: death rate is 0.66% and increases with age, study estimates. BMJ. 2020;369:m1327. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siopis G. Secrets to longevity: the Methuselahs that survived COVID-19. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021;69(10):2788–2790. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harris-Kojetin L., Sengupta M., Lendon J.P., Rome V., Valverdo R., Caffrey C., et al. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States, 2015-2016. Vital Health Stat. 2019;3:43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi A., Kim J.Y., Jo S., Jee J.H., Heymsfield S.B., Bhagat Y.A., et al. Smartphone-based bioelectrical impedance analysis devices for daily obesity management. Sensors (Basel) 2015;15(9):22151–22166. doi: 10.3390/s150922151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Negasheva M.A., Zimina S.N., Lapshina N.E., Sineva I.M. Express estimation of the biological age by the parameters of body composition in men and women over 50 years. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017;163(3):405–408. doi: 10.1007/s10517-017-3814-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.López-Otín C., Kroemer G. Hallmarks of health. Cell. 2021;184(1):33–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu B., Wang J., Chan K.M., Tjia W.M., Deng W., Guan X., et al. Genomic instability in laminopathy-based premature aging. Nat. Med. 2005;11(7):780–785. doi: 10.1038/nm1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Compher C., Frankenfield D., Keim N., Roth-Yousey L. Evidence Analysis Working Group, Best practice methods to apply to measurement of resting metabolic rate in adults: a systematic review. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006;106(6):881–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haugen H.A., Melanson E.L., Tran Z.V., Kearney J.T., Hill J.O. Variability of measured resting metabolic rate. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;78(6):1141–1144. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will not be made available because of the confidentiality clauses contained in the agreements to obtain datasets used in this analysis.