Abstract

Background

Maternal prenatal smoking is known to alter offspring DNA methylation (DNAm). However, there are no effective interventions to mitigate smoking-induced DNAm alteration.

Objectives

This study investigated whether 1-carbon nutrients (folate, vitamins B6, and B12) can protect against prenatal smoking-induced offspring DNAm alterations in the aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor (AHRR) (cg05575921), GFI1 (cg09935388), and CYP1A1 (cg05549655) genes.

Methods

This study included mother-newborn dyads from a racially diverse US birth cohort. The cord blood DNAm at the above 3 sites were derived from a previous study using the Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip. Maternal smoking was assessed by self-report and plasma biomarkers (hydroxycotinine and cotinine). Maternal plasma folate, and vitamins B6 and B12 concentrations were obtained shortly after delivery. Linear regressions, Bayesian kernel machine regression, and quantile g-computation were applied to test the study hypothesis by adjusting for covariables and multiple testing.

Results

The study included 834 mother-newborn dyads (16.7% of newborns exposed to maternal smoking). DNAm at cg05575921 (AHRR) and at cg09935388 (GFI1) was inversely associated with maternal smoking biomarkers in a dose-response fashion (all P < 7.01 × 10−13). In contrast, cg05549655 (CYP1A1) was positively associated with maternal smoking biomarkers (P < 2.4 × 10−6). Folate concentrations only affected DNAm levels at cg05575921 (AHRR, P = 0.014). Regression analyses showed that compared with offspring with low hydroxycotinine exposure (<0.494) and adequate maternal folate concentrations (quartiles 2–4), an offspring with high hydroxycotinine exposure (≥0.494) and low folate concentrations (quartile 1) had a significant reduction in DNAm at cg05575921 (M-value, ß ± SE = −0.801 ± 0.117, P = 1.44 × 10−11), whereas adequate folate concentrations could cut smoking-induced hypomethylation by almost half. Exposure mixture models further supported the protective role of adequate folate concentrations against smoking-induced aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor (AHRR) hypomethylation.

Conclusions

This study found that adequate maternal folate can attenuate maternal smoking-induced offspring AHRR cg05575921 hypomethylation, which has been previously linked to a range of pediatric and adult diseases.

Keywords: maternal smoking, 1-carbon micronutrients, folate concentrations, DNA methylation, aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor gene

Introduction

The epigenome sits at the interface of genes and environment and influences gene expression without altering the DNA sequence [1]. Alterations in DNA methylation patterns have been associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including cancer, metabolic, neurological, and autoimmune disorders [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Looking across the life course, the fetal period stands out as a critical window for epigenome establishment that is highly sensitive to both environmental perturbations and nutritional factors [6]. Understanding epigenetic regulation in relation to environmental and nutritional exposures during this critical period has important clinical and public health implications. For example, maternal smoking adversely affects more than half a million pregnancies each year in the US, despite decades of campaigns on smoking cessation. At the population level, maternal smoking is known to reduce birthweight [7] and affect a broad range of short- and long-term health outcomes [8,9]. At the molecular level, studies across different populations and age groups from in utero, childhood, adolescence, to adulthood have shown highly replicable smoking-induced DNAm alterations [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. Consistent with existing literature, our own study showed that maternal smoking significantly altered offspring DNAm at several important functional genes[15], including hypomethylation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor gene (AHRR, cg05575921) and growth factor independent 1 transcriptional repressor gene (GFI1, cg09935388), and hypermethylation of the cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A member 1 gene (CYP1A1, cg05549655), which significantly mediated prenatal smoking exposure-low birthweight associations. Despite these well-observed smoking-induced adverse health effects at both population and molecular levels, there is a lack of effective intervention to mitigate or reverse smoking-associated adverse health effects, including DNAm alterations. To address this unmet need, this study sought to investigate whether 1-carbon micronutrients can buffer the effects of maternal smoking on offspring DNAm.

We focused on 1-carbon micronutrients for several reasons. First, in recent years, there has been increasing recognition that nutritional factors should be further considered in the study of perturbations of DNAm associated with environmental exposures [16]. Indeed, mounting evidence suggests that maternal nutritional status during pregnancy influences the fetal epigenome [17]. As a proof of concept, studies have shown maternal vitamin C intake may counteract prenatal smoking-induced fetal DNAm alterations [18,19]. Second, biologically, 1-carbon micronutrients (for example, folate, B6, and B12) are thought to be particularly important [20] in this setting. These B vitamins are key elements of 1-carbon metabolism, which is crucial for many biochemical processes generating the methyl donor groups used for the DNAm process. A prior review raised an intriguing hypothesis that 1-carbon micronutrients may oppose smoking-induced DNAm alterations, given their key roles in maintaining normal patterns of DNAm [21]. To our knowledge, only 1 study by us has explored this hypothesis [22] but was limited by its small sample size, self-reported smoking exposure data, single nutrient, and no consideration of exposure mixture.

The current study sought to further delineate the interplay between maternal smoking during pregnancy and 1-carbon micronutrients status on newborn DNAm at the 3 well-known CpG sites in the AHRR, GFI1, and CYP1A1 genes whereas overcoming previous limitations and addressing critical knowledge gaps. Specifically, we measured plasma biomarkers of smoking (hydroxycotinine and cotinine) for exposure assessment, which also provides an opportunity to assess dose-response relationships more precisely [23]. We simultaneously examined maternal biomarkers of 3 1-carbon micronutrients (folate, vitamins B6, and B12) and their interactions with smoking on fetal DNAm. We applied BKMR and quantile g-computation (QGComp) to further delineate if 1-carbon micronutrients can mitigate smoking-induced DNAm alterations in the context of exposure mixtures. Such an approach is more aligned with a real-world scenario and is underscored by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences strategic priority [24]. Finally, we conducted this study in a US population known to be at high risk of exposure to smoking and insufficient folate yet underrepresented in environmental epigenomics research.

Methods

Study design and population

As outlined in Supplemental Figure 1, our study sample is a subset of mother-newborn pairs in the BBC, who had DNAm and plasma biomarkers of 1-carbon micronutrients and prenatal smoking exposure data. The BBC was initiated in 1998 at the Boston Medical Center (BMC) in Boston, MA, as detailed elsewhere [25]. In brief, mothers who delivered singleton live births at BMC were invited to participate shortly after giving birth. The BBC is enriched by preterm (<37 weeks of gestation) and low birthweight (<2500 grams) births due to over-sampling at enrollment by design. Pregnancies that were a result of in vitro fertilization, multiple gestations (for example, twins or triplets), fetal chromosomal abnormalities or major birth defects, or preterm birth due to trauma were excluded. Shortly after delivery, mothers who gave written informed consent were enrolled and asked to complete a standard questionnaire interview that collected information about maternal socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle, and behaviors, including smoking and alcohol consumption, diet, and reproductive and medical history. Maternal and newborn clinical information, including birth outcomes, was obtained from their electronic medical records. A maternal blood sample (nonfasting) was obtained 1–3 d after delivery by the research staff. Newborn cord blood was obtained by the trained nursing staff of the labor and delivery service at the time of birth. The study protocol has received initial and annual continuation approval by the institutional review boards of the BMC and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. All the study mothers signed written informed consent.

Definition of key outcome variables

The current analyses focused on newborn cord blood DNAm at 3 loci that are known to be affected by maternal smoking and significantly mediated prenatal smoking exposure-low birthweight associations [15], including cg05575921(AHRR), cg09935388 (GFI1), and cg05549655(CYP1A1). Detailed information about DNAm profiling and quality control steps has been reported previously [15]. All the subsequent DNAm analyses were based on the inversely normal transformed M-values for each CpG site with a standard deviation of 1.0. We also performed complementary analyses using β values for each CpG site and presented them as Supplemental Tables and Figures.

Definition of key exposure variables

Maternal smoking: This was defined by self-report and empiric metabolite biomarkers. Self-reported maternal smoking during pregnancy was defined based on responses to the questionnaire interview within 1–3 d after delivery: 1) “In the 6 months before you found out you were pregnant, did you smoke/use tobacco?”; 2) “Did you smoke/use tobacco in the first 3 months of pregnancy?”; 3) “Did you smoke/use tobacco in the middle 3 months of pregnancy?”; and 4) “Did you smoke/use tobacco in the last 3 months of pregnancy?” We defined “maternal ever smoking during pregnancy” as those mothers who answered “yes” to any of the above questions and defined “nonsmoking” as those mothers who answered “no” to all the above questions. Ever smokers were further divided into “Intermittent—those who stopped smoking since the 1st or 2nd or 3rd trimester” compared with “Continuous smokers—those who continued to smoke during the entire pregnancy.” There was no missing data on maternal self-reported smoking in this study sample. Whenever possible, intermittent and continuous smokers were analyzed separately. However, in subgroup analyses, intermittent and continuous smokers were combined as “ever smokers” due to sample size constraints.

Smoking biomarkers: We also measured maternal plasma biomarkers of smoking (cotinine and hydroxycoti) using LC-MS techniques. Detailed sample processing, quality control steps, and assay protocols have been reported elsewhere [[26], [27], [28]]. These values were inversely normalized based on relative intensity for use in all downstream analyses. For 57 mothers without metabolomic data, values were imputed based on the median biomarker value for the corresponding self-reported smoking category (never, intermittent, or continuous), as shown in Supplemental Figure 2.

Maternal plasma 1-carbon micronutrients: Using the same plasma sample for measuring smoking biomarkers, we measured the plasma folate concentration via chemiluminescent immunoassay with diagnostic kits (Shenzhen New Industries Biomedical Engineering Co, Ltd). Plasma vitamin B12 concentration was measured using the Beckman-Coulter ACCESS Immunoassay System (Beckman-Coulter Canada) using a MAGLUMI 2000 Analyzer. The inter-assay coefficient of variation was <4% for both folate and vitamin B12. [29,30]. Vitamin B6 was measured as part of the metabolomic panel using LC-MS techniques as detailed above and was inverse-normalized based on relative intensity for downstream analyses.

Major covariables: Data on maternal age at delivery, parity, newborn sex, birthweight, and gestational age at birth were extracted from the electronic medical records. Data on maternal race and ethnicity, and educational level were obtained from the standardized Maternal Postpartum Questionnaire interview at enrollment, conducted 1–3 d after delivery. We defined low birthweight as birthweight <2500 g and preterm birth as gestational age at birth <37 wk.

Statistical methods

Population characteristics, including demographic and clinical data, are presented as either number (%) or mean ± SD for the subgroups defined by maternal smoking status (never, intermittent, or continuous) (Table 1). The effect of maternal smoking and 1-carbon micronutrients on cord DNAm at the 3 candidate loci was examined. For each locus, the mean DNAm by the different smoking and folate subgroups were compared using ANOVA (Supplemental Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study sample (n = 834) stratified by maternal self-reported smoking status, Boston Birth Cohort.

| Variables | Maternal smoking status1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Quitter | Continuous | |

| N | 695 | 60 | 79 |

| Maternal variables | |||

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 28.50 (6.64) | 26.23 (6.78) | 29.05 (5.49) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 508 (73.1) | 46 (76.7) | 54 (68.4) |

| Others | 187 (26.9) | 14 (23.3) | 25 (31.6) |

| Education, N (%) | |||

| ≤High school | 442 (63.6) | 47 (78.3) | 63 (79.7) |

| >High school | 253 (36.4) | 13 (21.7) | 16 (20.3) |

| Parity (>1 live births), N (%) | 390 (56.1) | 31 (51.7) | 47 (59.5) |

| Cotinine, mean (SD)2 | −0.16 (0.83) | 0.67 (0.75) | 1.59 (0.64) |

| Hydroxycotinine, mean (SD)2 | −0.11 (0.70) | 0.63 (0.78) | 1.54 (0.70) |

| Folate, mean (SD), nmol/L | 36.41 (24.21) | 32.58 (19.27) | 31.27 (18.01) |

| B6, mean (SD)2 | −0.02 (1.01) | −0.03 (0.81) | 0.02 (1.16) |

| B12, mean (SD), pmol/L | 284.93 (108.95) | 288.09 (133.09) | 269.82 (88.43) |

| Child variables | |||

| Sex, male, N (%) | 358 (51.5) | 36 (60.0) | 40 (50.6) |

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 3179.05 (658.92) | 3020.92 (716.45) | 2864.71 (676.95) |

| Gestational weeks at delivery, mean (SD) | 38.68 (2.43) | 38.73 (2.79) | 37.98 (2.54) |

| N = 445 | N = 40 | N = 62 | |

| Cord cotinine, mean (SD) 2 | −0.14 (0.76) | 0.70 (0.90) | 1.56 (0.53) |

| Cord hydroxycotinine, mean (SD) 2 | −0.15 (0.70) | 0.53 (0.95) | 1.55 (0.65) |

Maternal self-reported smoking status: quitter is defined as stopping smoking since the first, second, or third trimester; continuous smoker is defined as continuing to smoke during the entire pregnancy.

These values were derived from metabolomic data and normalized based on relative intensity, including 57 mothers whose values were imputed due to missing data (see methods for details).

Multiple linear regression was performed to assess associations between DNAm at each of the 3 CpG loci in AHRR, CYP1A1, and GFI1 gene and individual exposures: maternal self-reported prenatal smoking status, maternal plasma hydroxycotinine, and cotinine concentrations, as well as their interaction with folate concentrations (Table 2). The interaction between folate (Q1 compared with Q2–Q4) and self-reported smoking status (yes compared with no), maternal plasma hydroxycotinine (dichotomized at the 75th percentile for never smokers, <0.494 compared with ≥0.494), and maternal plasma cotinine (dichotomized at the 75th percentile for never smokers, <0.492 compared with ≥0.492) was tested by including a product term in the respective regression models.

TABLE 2.

Association of maternal self-reported smoking and smoking biomarkers (hydroxycotinine, cotinine) individually and in combination with folate status (low compared with high) with cord blood DNA methylation at 3 loci

| DNA methylation1 | Smoking (0, 1, or 2) | Hydroxycotinine | Cotinine |

|---|---|---|---|

| AHRR (cg05575921) | N, β2 Se, P | N, β 2, Se, P | N, β 2, Se, P |

| Smoking as continuous variable | 834, −0.529, 0.054, <2 × 10−163 | 834, −0.376, 0.039, <2 × 10−16 | 834, −0.260, 0.036, 7.01 × 10−133 |

| Smoking–folate composite variables4 | |||

| Group 1 | 530, Ref. | 439, Ref. | 430, Ref. |

| Group 2 | 165, −0.134, 0.086, 0.118 | 126, −0.060, 0.098, 0.543 | 127, −0.182, 0.099, 0.068 |

| Group 3 | 54, −1.009, 0.137, 4.70 × 10−133 | 186, −0.426, 0.086, 8.28 × 10-73 | 195, −0.428, 0.086, 7.15 × 10-83 |

| Group 4 | 85, −0.748, 0.111, 6.53 × 10−113 | 83, −0.801, 0.117, 1.44 × 10−113 | 82, −0.647, 0.120, 9.58 × 10−83 |

| Smoking–folate interaction4 | 0.315 | 8.58 × 10-3 | 0.267 |

| GFI1 (cg09935388) | |||

| Smoking as continuous variable | 834, −0.436, 0.054, 1.42 × 10−153 | 834, −0.340, 0.038, <2 × 10−163 | 834, −0.302, 0.035, <2 × 10−163 |

| Smoking–folate composite variables5 | |||

| Group 1 | 530, Ref. | 439, Ref. | 430, Ref. |

| Group 2 | 165, −0.036, 0.086, 0.671 | 126, 0.030, 0.097, 0.758 | 127, −0.025, 0.097, 0.793 |

| Group 3 | 54, −0.823, 0.137, 2.84 × 10−93 | 186, −0.407, 0.085, 1.77 × 10−63 | 195, −0.465, 0.084, 3.62 × 10−83 |

| Group 4 | 85, −0.559, 0.113, 8.98 × 10−73 | 83, −0.662, 0.115, 1.34 × 10−83 | 82, −0.656, 0.117, 2.99 × 10−83 |

| Smoking–folate interaction4 | 0.204 | 0.060 | 0.075 |

| CYP1A1 (cg05549655) | |||

| Smoking as continuous variable | 834, 0.315, 0.046, 1.17 × 10−113 | 834, 0.209, 0.033, 4.15 × 10−103 | 834, 0.143, 0.030, 2.39 × 10−63 |

| Smoking–folate composite variables5 | |||

| Group 1 | 530, Ref. | 439, Ref. | 430, Ref. |

| Group 2 | 165, −0.009, 0.073, 0.907 | 126, −0.028, 0.084, 0.737 | 127, −0.026, 0.083, 0.750 |

| Group 3 | 54, 0.659, 0.117, 2.40 × 10-83 | 186, 0.283, 0.073, 1.10 × 10-43 | 195, 0.321, 0.072, 9.09 × 10−63 |

| Group 4 | 85, 0.305, 0.096, 0.002 | 83, 0.248, 0.099, 0.013 | 82, 0.296, 0.101, 0.003 |

| Smoking–folate interaction4 | 0.968 | 0.718 | 0.843 |

Abbreviations: AHRR, aryl hydrocarbon receptors repressor; CYP1A1, cytochrome P450; GFI1, growth factor independent 1 transcriptional repressor; Ref., reference.

DNA methylation M-value was used for all regressions.

Multiple linear regression model for individual smoking variables: Y = DNA methylation, X = smoking /hydroxycotinine/cotinine, adjusted for maternal age (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black compared with others), education (≤ high school or beyond high school), and child sex (male or female).

Significant after Bonferroni correction (threshold P = 0.05/27 = 1.9 × 10-3

Smoking-folate interaction is tested by the following model: Y = DNA methylation, X = smoking or hydroxycotinine or cotinine, adjusted for maternal age (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black compared with others), education (≤ high school, beyond high school), child sex (male, female), maternal folate (Q1, Q2–Q4), product term of smoking, and folate.

Smoking 0 = never smoker, 1 = intermittent smoker, 2 = continuous smoker. Multiple linear regression model for composite variables: Y = DNA methylation, X = smoking–folate groups 2–4 (group 1 as ref.), adjusted for maternal age (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black compared with others), education (≤ high school or beyond high school), and child sex (male or female). The composite variable is defined as follows:

Group 1: never smoking + folate Q2–Q4; hydroxycotinine <0.494 + folate Q2–Q4; or cotinine <0.492 + folate Q2–Q4, respectively.

Group 2: never smoking + folate Q1; hydroxycotinine <0.494 + folate Q1; or cotinine <0.492 + folate Q1, respectively.

Group 3: smoking + folate Q2–Q4; hydroxycotinine ≥0.494 + folate Q2–Q4; or cotinine ≥0.492 + folate Q2–Q4, respectively.

Group 4: smoking + folate Q1; hydroxycotinine ≥0.494 + folate Q1; or cotinine ≥0.492 + folate Q1, respectively.

The cutoff for defining low compared with high hydroxycotinine (0.494) and low compared with high cotinine (0.492) was based on the third quartile of corresponding value among never-smokers before imputation.

To explore combined association of smoking and folate with DNAm (Table 2), multiple linear regression was performed on a composite variable (4 subgroups, with a common reference group and 3 dummy variables in the model) defined by maternal smoking (yes or no) or hydroxycotinine (<0.494, ≥0.494) or cotinine (<0.492, ≥0.492) and folate (Q1, Q2–Q4) in relation to DNAm at the 3 loci, with adjustment for maternal age (continuous), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black compared with Other), maternal education (≤ high school, beyond high school), and child sex (male or female). We further adjusted for multiple testing using a stringent Bonferroni P value threshold of 0.05/27 = 0.0019 to account for 27 tests, including 3 exposures (self-reported smoking, hydroxycotinine, cotinine), 3 genes (AHRR, GFI1, and CYP1A1) and 3 micronutrients (Folate and vitamin B6, and B12). This applies to conventional regression model tests for interactions, but not for mixture models.

To explore if the exposure–outcome associations are consistent across racial/ethnic groups, the above analysis was further repeated among non-Hispanic Black participants (Supplemental Table 2).

To estimate the independent and overall effects of prenatal smoking exposure and each of the 3 1-carbon micronutrients on cord DNAm, we adopted the BKMR model [31], which flexibly estimates the joint health effects of multiple exposures using a nonparametric kernel function. We performed systematic analyses, including univariate dose-response relationships of each biomarker while holding the others constant at the median, bivariate dose-response relationships of each biomarker, and fixing a second biomarker at various quantiles (10th–90th) and holding the remaining biomarkers at their median values. We further investigated the overall effect of the smoking and 1-carbon micronutrients mixture on cord DNAm, obtained based on the difference in response when all the exposures are fixed at a specific quantile (10th–90th), compared with when all the exposures are fixed at their median value. In addition, to explore the potential protective effect of folate concentrations on DNAm changes associated with prenatal smoking exposure, we studied the overall effects of hydroxycotinine or cotinine, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 mixture on cord DNAm, stratified by maternal folate concentrations. In all analyses using BKMR, we included maternal age, race and ethnicity, education, and child’s sex as covariates. We implemented a component-wise selection method with 10,000 iterations using a Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm considering the relatively low-moderate correlations between smoking and B vitamins. BKMR was fit in R using the “BKMR” package (Bobb et al. [31]) with the default prior specification in the package.

As an alternative mixture method, we used the quantile-based g-computation (QGComp) method to estimate the joint associations of biomarkers of maternal smoking, folate, vitamin B6, and B12 with cord blood DNAm. We estimated the directions, weights, scaled effect (that is, partial effect), and overall mixture effect (psi) to estimate the relative importance of individual components of the mixture [32]. This novel method estimates the cumulative impact on DNAm of increasing all exposures in a specified mixture by 1 quartile. Compared with weighted quantile sum regression, this method relaxes the directional homogeneity assumption and allows for individual components in the mixture to contribute either a positive or negative weight to the overall mixture effect. We estimated the overall mixture effect (psi) and overall model confidence bounds using 200 bootstrapped samples. We further tested the interaction between a single nutrient (for example, folate) and the remaining exposure mixture (for example, hydroxycotinine and vitamin B6 and B12) on AHRR DNAm. QGComp was fit in R using the “qgcomp” package (32).

All the statistical analyses were performed using R Version 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Study sample characteristics

Supplemental Figure 1 presents the flow chart of study participant enrollment. This study included 834 mother-newborn dyads from the BBC, a US-based, predominantly urban sample of Back, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) residing in low-income communities. Population characteristics of the enrolled 834 mother-newborn dyads were largely comparable with that of the total 8623 dyads in the BBC, except that the included dyads had a higher percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks (Supplemental Table 1). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study sample stratified by maternal self-reported prenatal smoking status (never, intermittent, continuous). Of the 834 mothers, 695 (83.3%) were never smokers, whereas 139 (16.7%) were ever smokers during pregnancy.

Smoking exposure biomarker assessment

Supplemental Figure 2 presents boxplots of maternal plasma hydroxycotinine and cotinine by self-reported maternal smoking status and scatterplots and the correlation of maternal plasma hydroxycotinine and cotinine with cord blood hydroxycotinine and cotinine concentrations. Supplemental Figure 2A, B indicates high concordance between maternal hydroxycotinine/cotinine and self-reported maternal smoking status. Supplemental Figure 2C, D indicates a moderate correlation between maternal plasma hydroxycotinine/cotinine with cord blood hydroxycotinine/cotinine, indicating transplacental passage of smoking biomarkers. Taken together, these data support the use of maternal hydroxycotinine/cotinine as biomarkers of smoking exposure for both the mother and fetus.

Single exposure–outcome association

Supplemental Table 3 compared the means and SD of cord DNAm at the 3 candidate CpG loci by maternal prenatal smoking and 1-carbon micronutrient exposures. AHRR and GFI1 were found to have lower DNAm among intermittent and continuous smokers (P < 0.001), whereas CYP1A1 had higher DNAm among intermittent and continuous smokers (P < 0.001) than never smokers. Notably, maternal low folate concentrations were found to be associated with hypomethylation of the AHRR gene at cg05575921 (P = 0.014).

Figure 1 further examined the dose-response relationship between cord blood AHRR DNAm and maternal plasma hydroxycotinine (A), maternal plasma cotinine (B), and maternal plasma folate concentrations (C). Both maternal plasma hydroxycotinine and cotinine were inversely associated with AHRR DNAm in a dose-response fashion. In contrast, the relationship between maternal folate and cord blood AHRR DNAm was nonlinear: at the low end, higher folate concentrations were associated with higher DNAm, whereas at the high end, further increase in maternal folate concentrations no longer led to an increase in DNAm, indicating a ceiling effect. Similar findings were noted when DNAm β-values were analyzed instead of DNAm M-values (Supplemental Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Panels A–C present smoothing plots (and 95% CI) for cord blood AHRR gene methylation at cg05575921 (M-value) by normalized maternal plasma hydroxycotinine values (A), normalized maternal plasma cotinine values (B), and maternal plasma folate concentrations (C). Panel D presents change in cord blood AHRR gene methylation by comparing the 4 subgroups defined by maternal smoking (never, ever) and folate low compared with high (Q1 compared with Q2–Q4). The reference group is never smoking and high folate. The mean differences are −0.4% (0.8), −3.6% (0.7), and −6.6% (0.9) for groups 2, 3, and 4 respectively. AHRR, aryl hydrocarbon receptors repressor.

Bivariate exposures–outcome association

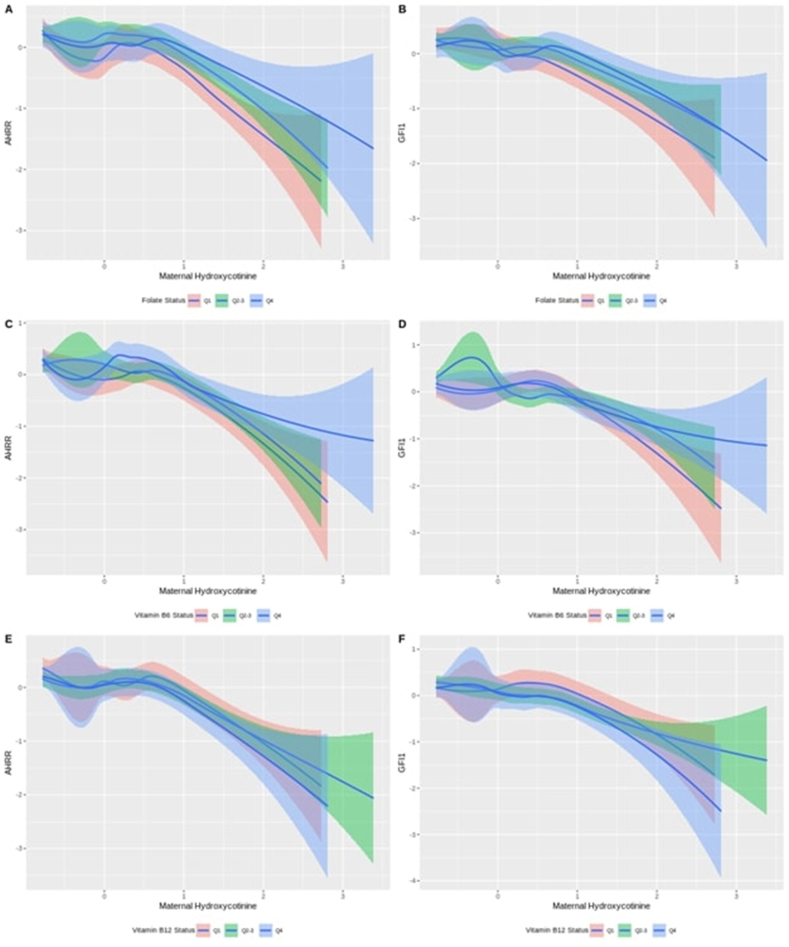

Figure 2 illustrates to what extent the association between AHRR gene methylation at cg05575921 and maternal plasma hydroxycotinine values varies by (A) maternal folate, (C) vitamin B6, and (E) vitamin B12 subgroups defined by quartiles (Q1, Q2–3, Q4). AHRR DNAm at cg05575921 was inversely associated with maternal hydroxycotinine in a dose-response fashion. For a given concentration of hydroxycotinine, we observed lower DNAm levels among participants with lower folate concentrations (Q1) than those with moderate (Q2–Q3) and high folate (Q4). Similar analyses were performed for GFI1 gene methylation at cg09935388 (Figure 2, right panels), but no clear pattern was observed.

FIGURE 2.

Left panels: smoothing plots for cord blood AHRR gene methylation by normalized maternal plasma hydroxycotinine values stratified by (A) maternal folate, (C) vitamin B6, (E) vitamin B12 subgroups defined by quartiles (Q1, Q2–Q3, Q4). Right panels: smoothing plots for cord blood GFI1 gene methylation by normalized maternal plasma hydroxycotinine stratified by (B) maternal folate, (D) vitamin B6, (F) vitamin B12 subgroups defined by quartiles (Q1, Q2–Q3, Q4). AHRR, aryl hydrocarbon receptors repressor; GFI1, growth factor independent 1 transcriptional repressor.

Table 2 presented the results of multivariable regression to quantify the joint association of maternal self-reported prenatal smoking or hydroxycotinine or cotinine biomarkers with plasma folate on cord blood DNAm in the 3 loci. Compared with the reference group with low hydroxycotinine and adequate folate (Q2–Q4), the greatest reduction of DNAm in the AHRR gene (cg05575921) was observed among the group with high hydroxycotinine and low folate (first quartile) (M-value, β = −0.801, SE = 0.117, P = 1.44 × 10−11). Notably, the smoking-induced DNA hypomethylation was cut by almost half if mothers had adequate folate. Such an effect modification by folate on smoking-induced hypomethylation at cg05575921 was illustrated by Figure 1D based on M-value, with a change from −0.801 with inadequate folate to −0.426 with adequate folate. Supplemental Figure 3 shows consistent results using ß values, a change from −6.6% to −3.6%. There was a suggestive interaction between hydroxycotinine and folate on AHRR DNAm (nominal P = 0.009). No other interactions were detected.

As a sensitivity analysis, Supplemental Table 2 presented results for the joint association of maternal smoking or smoking biomarkers (hydroxycotinine or cotinine) with folate on cord blood DNAm in the 3 loci among non-Hispanic Black participants. Consistent with the overall sample, smoking, and biomarkers of smoking were associated with decreased DNAm in the AHRR and GFI1 genes (P < 0.001) and increased DNAm in the CYP1A1 genes (P < 0.001). No interactions were detected.

Supplemental Table 4 presents results for the joint association of maternal smoking or smoking biomarkers (hydroxycotinine or cotinine) with vitamin B6 on cord blood DNA methylation in the 3 loci. No interactions were detected.

Supplemental Table 5 presents the results for the joint association of maternal smoking or smoking biomarkers (hydroxycotinine or cotinine) with vitamin B12 on cord blood DNA methylation in the 3 loci at AHRR, GFI1, and CYP1A1 genes. No interactions were detected.

Exposure mixture–outcome association

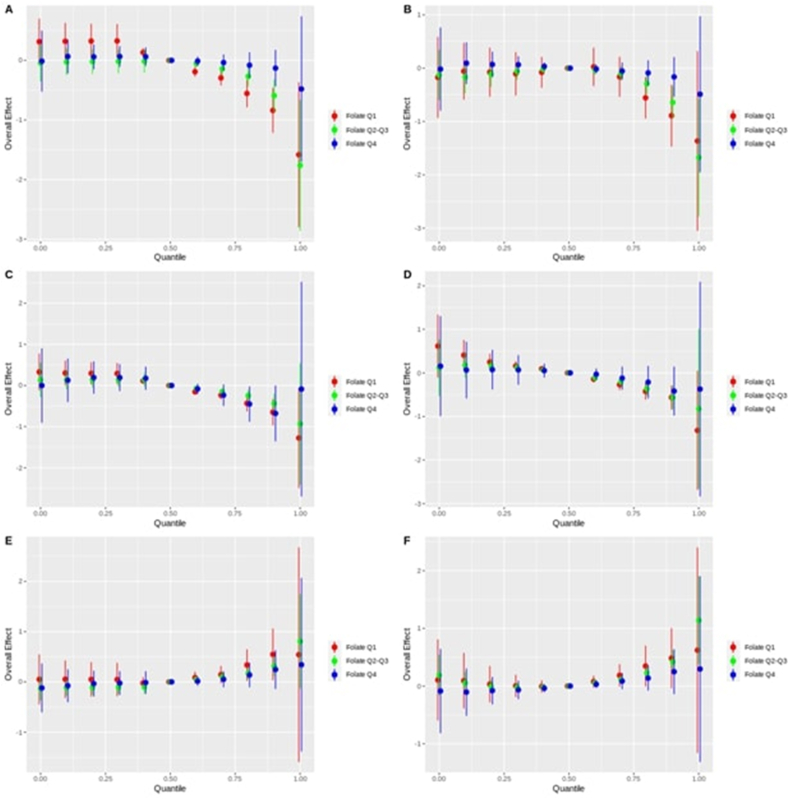

Figure 3 presents the BKMR plots for the overall effects of the B vitamins (B6 and B12) and hydroxycotinine (A, C, E) or cotinine (B, D, F) mixture on DNAm of AHRR, GFI1, and CYP1A1, stratified by folate concentrations. Low folate (Q1) is compared with moderate (Q2–Q3) and high folate (Q4). In the setting of low folate, AHRR DNAm at cg05575921 showed a rapid decline with increasing mixture quantiles. In contrast, high folate was able to protect against AHRR DNAm decline until about the 90th quantile, when the DNA begins to demethylate. Moderate folate maintains AHRR DNAm between that of high and low folate. Conversely, high folate maintains a lower CYP1A1 DNAm at cg05549655, whereas lower folate increases CYP1A1 DNAm with moderate folate situated in between. No clear difference can be seen for GFI1 DNAm at cg09935388. Similar results can be seen when repeated with cotinine instead of hydroxycotinine.

FIGURE 3.

Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) estimated overall effect of B vitamins (vitamins B6 and B12) and hydroxycotinine mixture quantile (0–1.0) on the DNA methylation of the genes: A) AHRR (cg05575921), C) GFI1(cg09935388), and E) CYP1A1 (cg05549655), stratified by folate subgroups; and overall effect of B vitamins (Vitamin B6, Vitamin B12) and cotinine mixture quantile (0–1.0) on the DNA methylation of the genes: B) AHRR, D) GFI1, and F) CYP1A1, stratified by folate subgroups. For all the figures, the Y-axis is the overall effect on the gene DNA methylation, X-axis is the exposure mixture quantile, and the reference group is the 50th quantile. Folate subgroups are defined by folate quartiles (Q1, Q2–Q3, Q4) and color coded. AHRR, aryl hydrocarbon receptors repressor; CYP1A1, cytochrome P450; GFI1, growth factor independent 1 transcriptional repressor.

Supplemental Figure 4 presents the BKMR plots of the overall effects of the vitamin B12, folate, and hydroxycotinine (A, C, E) or cotinine (B, D, F) mixture on DNAm of AHRR, GFI1, and CYP1A1, stratified by vitamin B6 concentrations. Low vitamin B6 (Q1) is compared with moderate (Q2–Q3) and high vitamin B6 (Q4). Low vitamin B6 shows a rapid decline in AHRR DNAm with increasing mixture quantiles, and moderate vitamin B6 shows a similar trend. In contrast, high vitamin B6 showed a slower decline in AHRR DNAm; and a similar effect was observed for GFI1 DNAm. Similar results can be seen when repeated with cotinine instead of hydroxycotinine.

Supplemental Figure 5 presents the BKMR plots for the overall effects of the vitamin B6, folate, and hydroxycotinine (A, C, E) or cotinine (B, D, F) mixture on DNAm of AHRR, GFI1, and CYP1A1, stratified by vitamin B12 concentrations. Low vitamin B12 (Q1) is compared with moderate (Q2–Q3) and high vitamin B12 (Q4). High vitamin B12 shows a rapid decline in AHRR DNAm with increasing mixture quantiles, and moderate vitamin B6 shows a similar trend. In contrast, low B12 showed a slower decline in AHRR DNAm; and a similar effect was observed for GFI1 DNAm. For CYP1A1 DNAm, both moderate and high vitamin B12 concentrations increased DNAm, whereas low vitamin B12 reduced DNAm the most. Similar results can be seen when repeated with cotinine instead of hydroxycotinine.

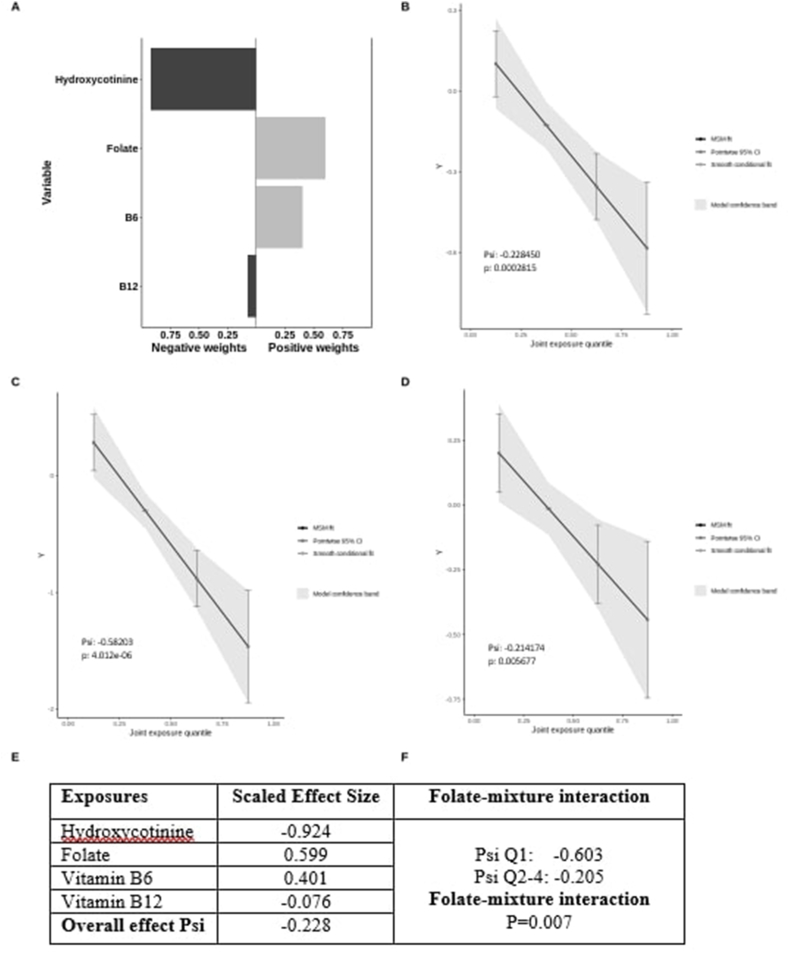

As a complementary mixture analysis, Figure 4 presents the effects of jointly increasing hydroxycotinine and 1-carbon micronutrients on AHRR DNAm modeled with QGComp. Panel A presents directions and weights of individual exposures, showing that hydroxycotinine had a large negative weight (−0.924) and vitamin B12 had a slight negative weight (−0.076), suggesting that hydroxycotinine was the main contributor to the negative mixture effect. Both folate and vitamin B6 had positive weights, 0.599 and 0.401, respectively. Panel B showed an inverse linear effect of jointly increasing hydroxycotinine, folate, vitamin B6, and B12 on AHRR DNAm (Psi = −0.228). Panels C and D showed stratified analysis by folate status: the high folate (Q2–Q4) group had a slightly attenuated slope (Psi = −0.214), whereas the low folate (Q1) group had a significantly steeper negative slope (Psi = −0.582). Panel F showed a suggestive interaction between folate and the remaining mixture on AHRR DNAm (nominal P = 0.007). These results again support that folate attenuates smoking-induced AHRR DNA hypomethylation at cg05575921.

FIGURE 4.

Quantile g-computation model estimated weights corresponding to the proportion of the positive or negative scaled effect on AHRR gene DNA methylation per maternal hydroxycotinine and 1-carbon micronutrients (folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12) mixtures (Panel A); Panels B, C, D present quantile g-computation model generated plots to assess linear association of the total exposure effect of maternal hydroxycotinine and 1-carbon micronutrients (folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12) on AHRR gene DNA methylation at cg05575921 in overall sample (B), in low folate (quartile 1) subgroup (C), and in high folate (quartiles 2–4) subgroup (D). E is a table to present scaled effect size for each component of the mixture and overall effect of the mixture (Psi); and F is a table to present the results of test for folate-mixture interaction. AHRR, aryl hydrocarbon receptors repressor; MSM, marginal structural model.

Discussion

This study tested the hypothesis that maternal circulating 1-carbon micronutrients (folate and vitamins B6 and B12) may provide protection against the effects of prenatal smoking exposure-induced offspring DNAm alterations in the AHRR (cg05575921), GFI1 (cg09935388), CYP1A1 (cg05549655) CpG sites, given these micronutrients’ key roles in maintaining DNAm processes. The strengths of this study include objective measurement of plasma biomarkers of smoking (hydroxycotinine and cotinine) for exposure assessment, which also provides an opportunity to assess dose-response relationships more precisely [23], and simultaneous examination of maternal biomarkers of 3 1-carbon micronutrients (folate, vitamins B6 and B12) and their interactions with smoking on fetal DNAm. The study was further strengthened by using advanced exposure mixture analyses (BKMR and QGComp) and testing the nutrient-smoking interactions in the context of the exposure mixture. A unique aspect of this study is that it was conducted in a large US birth cohort of a predominantly underrepresented minority population living in low-income communities, a population reported to have a high prevalence of prenatal smoking and suboptimal folate nutrition [33].

Our systematic analyses revealed an inverse dose-response relationship between prenatal smoking biomarkers and cord DNAm, and more importantly, adequate folate attenuated the prenatal hydroxycotinine-induced cord DNA hypomethylation at cg05575921 in the AHRR gene by almost half (from −6.6% to −3.6%). Below, we discuss our findings in the context of existing literature and highlight new insights gained from this study.

Dose-response relation of maternal plasma biomarkers of smoking with cord blood DNAm

Previous studies have shown that maternal smoking alters cord blood DNAm in multiple genes, including AHRR, GFI1, and CYP1A1[13]. However, most studies were based on self-reported smoking status. Our study was strengthened by the dual assessment of prenatal smoking exposure by maternal self-report (never, intermittent, or continuous) and quantitative measure of plasma biomarkers (hydroxycotinine/cotinine concentrations). We found a clear gradient of these biomarkers with self-reported smoking status, validating both exposure biomarker measures. The good correlation between maternal and cord blood hydroxycotinine and cotinine indicates the transplacental passage of these biomarkers and their utility as a proxy of fetal exposure to maternal smoking while developing in utero. Most notably, our finding on smoking-induced AHRR (cg05575921) and GFI1 (cg09935388) gene hypomethylation is consistent with previous literature across different populations and age groups [[34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. Furthermore, with measured smoking biomarkers, this study demonstrated a significant inverse dose-response relationship of hydroxycotinine and cotinine smoking with cord DNAm in both loci.

The interplay of 1-carbon micronutrients and smoking on cord blood DNAm alteration

This study has made interesting observations. First, of the 3 1-carbon micronutrients, folate appears to be the most important in association with DNA methylation. The relationship between maternal folate and cord blood AHRR DNAm at cg05575921 was nonlinear: at the low end (<25 nmol/L), there is a steep positive association between folate concentrations and AHRR DNAm levels; beyond that, further increase in maternal folate concentrations no longer led to any significant increase in AHRR DNAm, indicating the need to define a threshold for the optimal folate concentrations. This is consistent with what we know about the health benefits of most essential nutrients. Second, AHRR gene DNAm at cg05575921 is highly sensitive to both smoking exposure and folate concentrations. Our systematic analyses using different statistical approaches all provided consistent evidence that higher folate is associated with higher DNAm levels at AHRR and appears to attenuate prenatal smoking exposure-induced AHRR hypomethylation. We also demonstrated a suggestive interaction between maternal prenatal smoking and folate concentrations on cord blood AHRR DNAm at cg05575921.

Similar analyses were performed for vitamin B6 and suggested a protective but less robust effect than folate. Similar analyses were also performed on B12, but no significant effect was seen. One possible explanation is that, although folate, vitamin B6, and B12 are all an integral part of 1-carbon metabolism, folate is a required nutrient input that is consumed as a methyl donor for DNA synthesis and DNA methylation, whereas vitamin B6 and B12 serve as cofactors for the enzymes. Another reason is that maternal folate concentrations in this study sample were highly variable, ranging from low to high concentrations, allowing us to demonstrate a dose-response relationship. Our findings also imply that this population is very likely to benefit from the optimization of folate nutrition.

Clinical and public health implications

This study addressed an important unmet need, that is, maternal smoking during pregnancy is known to alter offspring DNAm and is detectable across the lifespan. However, there is little evidence for effective interventions to mitigate smoking-induced DNAm alteration. Our finding that folate can counteract smoking-induced AHRR gene hypomethylation at cg05575921 if further confirmed, could inform novel and actionable clinical and public health interventions against smoking-induced AHRR hypomethylation and related adverse health effects. AHRR gene hypomethylation has been linked with a range of pediatric and adult diseases, including male infertility, endometriosis, obesity, myocardial infarction, decreased lung and kidney function, various cancers, and mortality [[34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]].

Despite universal folic acid grain fortification implemented since 1998 in the US and clinical recommendation of prenatal multivitamins for pregnant women, data from the BBC and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey have indicated substantial variability in plasma folate concentrations among US reproductive-age women.[33,41]. Among them, Black and Hispanic women tended to have lower blood folate concentrations than did non-Hispanic White women[41,42]. During pregnancy, the physiological requirement for folate is greatly increased because of the enlargement of the uterus and the growth and development of the placenta and fetus; thus, folate insufficiency is more likely to occur[43]. Our findings, if further confirmed, underscore the importance of screening and ensuring adequate folate intake and blood folate concentrations among pregnant people, in particular, among those who smoke, to minimize maternal smoking-induced fetal DNAm alterations and, perhaps, associated long-term consequences.

Furthermore, folate nutritional status has been linked with a range of health outcomes in both children and adults. The causal role of folate deficiency in neural tube defects (NTDs) is well-established, and folic acid supplementation is effective in reducing NTDs[44]. Research has also linked maternal folate insufficiency with adverse pregnancy outcomes and adequate folate with reproductive, neurodevelopmental, and cardiovascular benefits[[44], [45], [46], [47]]. As such, adequate maternal folate nutrition has implications for a broad range of health and diseases.

Biological plausibility

Our findings are biologically plausible and may provide clues for intervention targets and useful biomarkers. Folate is a major methyl donor in 1-carbon metabolism, critical for nucleic acid synthesis and DNAm, which, in turn, are essential for cellular growth, differentiation, DNA integrity, and gene regulation [48]. One-carbon metabolism represents a critical biological pathway to elucidate molecular mechanisms underlying key interactions between genes, nutrients, and environmental toxins. Given its strong and robust association with both smoking and folate, AHRR CpG methylation status could serve as a biomarker for monitoring the biological effects of smoking and folate status.

Limitations and future directions

This study was conducted in an American predominantly urban, low-income, minority population, which is both a strength (understudied population) and a weakness (less generalizable). Our study sample (n = 834) is only a subset of the whole BBC (n = 8623). To address potential selection bias, we compared the subset with the whole BBC (Supplemental Table 1), and we found the subset had a higher percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks. Otherwise, the distributions of other covariables were comparable. As presented in Supplemental Table 3, the results from the analysis limited to non-Hispanic Blacks only were similar to that of the entire study sample (n = 834), suggesting that a higher percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks should not bias the results. In this study, exposure biomarkers, including prenatal maternal smoking and 1-carbon nutrients, were only measured at 1 time point (at birth). Measurements taken at additional time points (at preconception and each trimester) would contribute to a better understanding of the timing of exposures on DNAm. Additionally, many other environmental and nutritional exposures can also affect DNAm; thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that our findings could be confounded by other environmental, demographic, and nutritional coexposures. Another limitation is that due to taking nonfasting blood samples, plasma folate could have been highly influenced by recent intake, such as multivitamins. However, the blood samples were collected 1–3 d after delivery while the study mothers were still hospitalized in the post-delivery ward. During labor and post-delivery hospital stay, mothers were not given multivitamins. This implies that all the study mothers did not take multivitamins for ≥24 h. This study only examined DNAm at birth; a longitudinal analysis of DNAm at different developmental stages would help shed light on to what extent the DNAm pattern seen at birth persists into later life and to what extent postnatal environmental and nutritional influences might modify DNAm over time. Additionally, genetic variation may also influence response and metabolism of prenatal smoking and micronutrient exposure and DNA methylation. Future studies should integrate both genetic and epigenetic architectures to gain deep insight into gene-environment-nutrient interactions [[49], [50], [51]]. This study was also limited by examining smoking-gene-folate interaction on DNAm of cg05575921, which is a well-known CpG site affected by cigarette smoking of the AHRR gene that has been linked to various adverse health outcomes including low birthweight, chronic diseases including cancer, and mortality across the life course [[34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. Future studies should further link fetal DNAm alterations in cg05575921 with smoking-related morbidities and mortality later in life. We emphasize that our findings should only serve as a proof of concept that adequate maternal folate could potentially counteract smoking-induced AHRR gene hypomethylation and additional study is needed to replicate the findings and to deepen our understanding of the biology and clinical translational value (that is, association compared with causation). Our findings serve as an impetus for advancing precision nutrition [52] to inform a safe, effective, and scalable nutritional intervention to minimize smoking-induced adverse consequences across the life course and serve as a prototype to tackle other environmental chemicals and micronutrients.

In summary, this study examined the individual and mixture effects of maternal biomarkers of prenatal smoking and 1-carbon micronutrients (folate, vitamin B6, and B12) exposures on offspring cord blood DNAm in a sample of US mother-newborn dyads living in low-income communities and households. Using both conventional and exposure mixture analyses, this study revealed that maternal plasma biomarkers of smoking were associated with fetal AHRR CpG hypomethylation at cg05575921 in a dose-response fashion. More importantly, adequate plasma folate concentrations were found to attenuate prenatal smoking exposure-induced AHRR CpG hypomethylation by almost half. These findings and their implications emphasize the in utero period as a critical window for epigenetic programming and the importance of considering coexposures in assessing environmental and nutritional influences on the epigenome. This line of investigation may open new avenues to identify novel molecular targets and inform safe, effective, and scalable intervention strategies to mitigate environmentally induced epigenetic alterations and associated short- and long-term adverse health effects. The findings will be directly relevant to improve environmental equity and reduce health disparities in US BIPOC populations.

Funding

This work used data from the Boston Birth Cohort (the parent study), which was supported in part by the NIH grants (R21ES011666, R01HD041702, R21HD066471, R01HD086013, R01HD098232, R01ES031272, R21AI154233, R01ES031521, and U01 ES034983); and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services (UT7MC45949). XH and GW are partly supported by the Johns Hopkins Population Center Grant (P2CHD042854) from the NICHD. HJ is supported by grants from NIH/National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) (R01HG009518 and R01HG010889). This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by any funding agencies.

Author disclosures

CLA receives consulting fees from the University of Iowa for providing autism expertise outside the scope of this work. RX, XH, JPB, GC, GW, WG, XW, LL, and HJ, no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—RX, XH, LL, and HJ: conceived and designed the study; GW, XH, and XW: participated in biosample collection, storage, assays, and data management; RX: conducted all the statistical analyses, generated tables and figures, and drafted the manuscript. GC and JB: helped in QGComp analysis; CLA: provided helpful input on data analyses and presentation; RX, HJ, and XH: have full access to the data and verified the underlying analyses and results; and all authors: contributed to the critical review and revision of the manuscript and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data, data dictionary, and analytical programs for this manuscript are not currently available to the public. However, they can be made available upon reasonable request and after the review and approval of the institutional review board.

The R code supporting the findings of this study is available upon request from the lead author (Xu R).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all study participants in the Boston Birth Cohort (BBC). We also acknowledge the nursing staff at Labor and Delivery of the Boston Medical Center and the field team for their contributions to the BBC.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.05.002.

Contributor Information

Xiumei Hong, Email: xhong3@jhu.edu.

Hongkai Ji, Email: hji@jhu.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Feinberg A.P. The key role of epigenetics in human disease prevention and mitigation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378(14):1323–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulis M., Esteller M. DNA methylation and cancer. Adv. Genet. 2010;70:27–56. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380866-0.60002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samblas M., Milagro F.I., Martínez A. DNA methylation markers in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and weight loss. Epigenetics. 2019;14(5):421–444. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2019.1595297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrlich M. DNA hypermethylation in disease: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Epigenetics. 2019;14(12):1141–1163. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2019.1638701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zouali M. DNA methylation signatures of autoimmune diseases in human B lymphocytes. Clin. Immunol. 2021;222 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richmond R.C., Sharp G.C., Herbert G., Atkinson C., Taylor C., Bhattacharya S., et al. The long-term impact of folic acid in pregnancy on offspring DNA methylation: follow-up of the Aberdeen folic acid supplementation trial (AFAST) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):928–937. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X., Zuckerman B., Pearson C., Kaufman G., Chen C., Wang G., et al. Maternal cigarette smoking, metabolic gene polymorphism, and infant birth weight. JAMA. 2002;287(2):195–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham M., Alramadhan S., Iniguez C., Duijts L., Jaddoe V.W., Den Dekker H.T., et al. A systematic review of maternal smoking during pregnancy and fetal measurements with meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banderali G., Martelli A., Landi M., Moretti F., Betti F., Radaelli G., et al. Short and long term health effects of parental tobacco smoking during pregnancy and lactation: a descriptive review. J. Transl. Med. 2015;13:327. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Küpers L.K., Xu X., Jankipersadsing S.A., Vaez A., la Bastide-van Gemert S., Scholtens S., et al. DNA methylation mediates the effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on birthweight of the offspring. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015;44(4):1224–1237. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joubert B.R., Håberg S.E., Nilsen R.M., Wang X., Vollset S.E., Murphy S.K., et al. 450K epigenome-wide scan identifies differential DNA methylation in newborns related to maternal smoking during pregnancy. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120(10):1425–1431. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers J.M. Smoking and pregnancy: epigenetics and developmental origins of the metabolic syndrome. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111(17):1259–1269. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joubert B.R., Felix J.F., Yousefi P., Bakulski K.M., Just A.C., Breton C., et al. DNA methylation in newborns and maternal smoking in pregnancy: genome-wide consortium meta-analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;98(4):680–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardenas A., Ecker S., Fadadu R.P., Huen K., Orozco A., McEwen L.M., et al. Epigenome-wide association study and epigenetic age acceleration associated with cigarette smoking among Costa Rican adults. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1):4277. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08160-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu R., Hong X., Zhang B., Huang W., Hou W., Wang G., et al. DNA methylation mediates the effect of maternal smoking on offspring birthweight: a birth cohort study of multi-ethnic US mother-newborn pairs. Clin. Epigenetics. 2021;13(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s13148-021-01032-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin E.M., Fry R.C. Environmental influences on the epigenome: exposure- associated DNA methylation in human populations. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2018;39:309–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James P., Sajjadi S., Tomar A.S., Saffari A., Fall C.H.D., M Prentice A., et al. Candidate genes linking maternal nutrient exposure to offspring health via DNA methylation: a review of existing evidence in humans with specific focus on one-carbon metabolism. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018;47(6):1910–1937. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shorey-Kendrick L.E., McEvoy C.T., O’Sullivan S.M., Milner K., Vuylsteke B., Tepper R.S., et al. Impact of vitamin C supplementation on placental DNA methylation changes related to maternal smoking: association with gene expression and respiratory outcomes. Clin. Epigenetics. 2021;13(1):177. doi: 10.1186/s13148-021-01161-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shorey-Kendrick L.E., McEvoy C.T., Ferguson B., Burchard J., Park B.S., Gao L., et al. Vitamin C prevents offspring dna methylation changes associated with maternal smoking in pregnancy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2017;196(6):745–755. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2141OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson O.S., Sant K.E., Dolinoy D.C. Nutrition and epigenetics: an interplay of dietary methyl donors, one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012;23(8):853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richmond R.C., Joubert B.R. Contrasting the effects of intra-uterine smoking and one-carbon micronutrient exposures on offspring DNA methylation. Epigenomics. 2017;9(3):351–367. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang B., Hong X., Ji H., Tang W.Y., Kimmel M., Ji Y., et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and cord blood DNA methylation: new insight on sex differences and effect modification by maternal folate levels. Epigenetics. 2018;13(5):505–518. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2018.1475978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kheirkhah Rahimabad P., Anthony T.M., Jones A.D., Eslamimehr S., Mukherjee N., Ewart S., et al. Nicotine and its downstream metabolites in maternal and cord sera: biomarkers of prenatal smoking exposure associated with offspring DNA methylation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(24) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlin D.J., Rider C.V., Woychik R., Birnbaum L.S. Unraveling the health effects of environmental mixtures: an NIEHS priority. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013;121(1):A6–A8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearson C., Bartell T., Wang G., Hong X., Rusk S.A., Fu L., et al. Boston birth cohort profile: rationale and study design. Precis. Nutr. 2022;1(2) doi: 10.1097/PN9.0000000000000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Townsend M.K., Clish C.B., Kraft P., Wu C., Souza A.L., Deik A.A., et al. Reproducibility of metabolomic profiles among men and women in 2 large cohort studies. Clin. Chem. 2013;59(11):1657–1667. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.199133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts L.D., Souza A.L., Gerszten R.E., Clish C.B. Chapter 30, Targeted metabolomics. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2012:1–24. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb3002s98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong X., Liang L., Sun Q., Keet C.A., Tsai H.J., Ji Y., et al. Maternal triacylglycerol signature and risk of food allergy in offspring. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019;144(3):729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang G., Hu F.B., Mistry K.B., Zhang C., Ren F., Huo Y., et al. Association between maternal prepregnancy body mass index and plasma folate concentrations with child metabolic health. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(8) doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raghavan R., Riley A.W., Volk H., Caruso D., Hironaka L., Sices L., et al. Maternal multivitamin intake, plasma folate and vitamin B12 levels and autism spectrum disorder risk in offspring. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2018;32(1):100–111. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bobb J.F., Valeri L., Henn B.C., Christiani D.C., Wright R.O., Mazumdar M., et al. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics. 2015;16(3):493–508. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxu058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keil A.P., Buckley J.P., O’Brien K.M., Ferguson K.K., Zhao S., White A.J. A quantile-based g-computation approach to addressing the effects of exposure mixtures. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020;128(4) doi: 10.1289/EHP5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng T.L., Mistry K.B., Wang G., Zuckerman B., Wang X. Folate nutrition status in mothers of the Boston birth cohort, sample of a US urban low-income population. Am. J. Public Health. 2018;108(6):799–807. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakayama K., Saito S., Watanabe K., Miyashita H., Nishijima F., Kamo Y., et al. Influence of AHRR Pro189Ala polymorphism on kidney functions. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2017;81(6):1120–1124. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2017.1292838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang S.Y., Ahmed S., Satheesh S.V., Matthews J. Genome-wide mapping and analysis of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR)- and aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor (AHRR)-binding sites in human breast cancer cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2018;92(1):225–240. doi: 10.1007/s00204-017-2022-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kemp Jacobsen K., Johansen J.S., Mellemgaard A., Bojesen S.E. AHRR (cg05575921) methylation extent of leukocyte DNA and lung cancer survival. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Philibert R., Dogan M., Beach S.R.H., Mills J.A., Long J.D. AHRR methylation predicts smoking status and smoking intensity in both saliva and blood DNA. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2020;183(1):51–60. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shahin N.N., Abd-Elwahab G.T., Tawfiq A.A., Abdelgawad H.M. Potential role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling in childhood obesity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2020;1865(8) doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar P., Yadav M., Verma K., Dixit R., Singh J., Tiwary S.K., et al. Expression analysis of aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor (AHRR) gene in gallbladder cancer. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2021;27(1):54–59. doi: 10.4103/sjg.SJG_213_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langsted A., Bojesen S.E., Stroes E.S.G., Nordestgaard B.G. AHRR hypomethylation as an epigenetic marker of smoking history predicts risk of myocardial infarction in former smokers. Atherosclerosis. 2020;312:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marchetta C.M., Hamner H.C. Blood folate concentrations among women of childbearing age by race/ethnicity and acculturation, NHANES 2001–2010, Matern. Child Nutr. 2016;12(1):39–50. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tinker S.C., Hamner H.C., Qi Y.P., Crider K.S. U.S. women of childbearing age who are at possible increased risk of a neural tube defect-affected pregnancy due to suboptimal red blood cell folate concentrations. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007 to 2012, Birth Defects Research Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2015;103(6):517–526. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenberg J.A., Bell S.J., Guan Y., Yu Y.H. Folic acid supplementation and pregnancy: more than just neural tube defect prevention. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;4(2):52–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Wals P., Tairou F., Van Allen M.I., Uh S.H., Lowry R.B., Sibbald B., et al. Reduction in neural-tube defects after folic acid fortification in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357(2):135–142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ouyang F., Longnecker M.P., Venners S.A., Johnson S., Korrick S., Zhang J., et al. Preconception serum 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2,bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethane and B-vitamin status: independent and joint effects on women’s reproductive outcomes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;100(6):1470–1478. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.088377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Surén P., Roth C., Bresnahan M., Haugen M., Hornig M., Hirtz D., et al. Association between maternal use of folic acid supplements and risk of autism spectrum disorders in children. JAMA. 2013;309(6):570–577. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.155925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huo Y., Li J., Qin X., Huang Y., Wang X., Gottesman R.F., et al. Efficacy of folic acid therapy in primary prevention of stroke among adults with hypertension in China: the CSPPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(13):1325–1335. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crider K.S., Yang T.P., Berry R.J., Bailey L.B. Folate and DNA methylation: a review of molecular mechanisms and the evidence for folate’s role. Adv. Nutr. 2012;3(1):21–38. doi: 10.3945/an.111.000992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bell J.T., Pai A.A., Pickrell J.K., Gaffney D.J., Pique-Regi R., Degner J.F., et al. DNA methylation patterns associate with genetic and gene expression variation in HapMap cell lines. Genome Biol. 2011;12(1):R10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-1-r10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaunt T.R., Shihab H.A., Hemani G., Min J.L., Woodward G., Lyttleton O., et al. Systematic identification of genetic influences on methylation across the human life course. Genome Biol. 2016;17:61. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0926-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Y.A., Lemire M., Choufani S., T Butcher D., Grafodatskaya D., Zanke B.W., et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and.polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics. 2013;8(2):203–209. doi: 10.4161/epi.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu B.P., Shi H. Precision nutrition: concept, evolution, and future vision. Prec. Nutr. 2022;1(1) doi: 10.1097/PN9.0000000000000002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data, data dictionary, and analytical programs for this manuscript are not currently available to the public. However, they can be made available upon reasonable request and after the review and approval of the institutional review board.

The R code supporting the findings of this study is available upon request from the lead author (Xu R).