Abstract

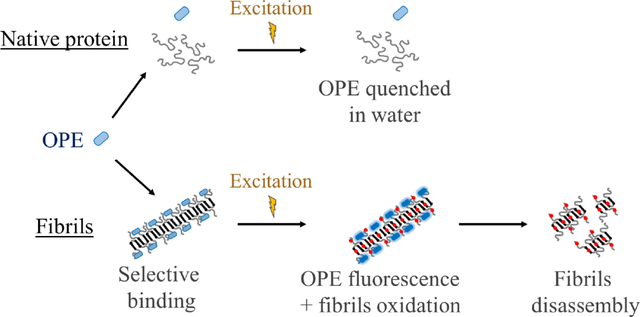

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been explored as a therapeutic strategy to clear toxic amyloid aggregates involved in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. A major limitation of PDT is off-target oxidation, which can be lethal for the surrounding cells. We have shown that a novel class of oligo-p-phenylene ethynylene-based compounds (OPEs) exhibit selective binding and fluorescence turn-on in the presence of pre-fibrillar and fibrillar aggregates of disease-relevant proteins such as amyloid-β (Aβ) and α-synuclein. Concomitant with fluorescence turn-on, OPE also photosensitizes singlet oxygen under illumination through the generation of a triplet state, pointing to the potential application of OPEs as photosensitizers in PDT. Herein, we investigated the photosensitizing activity of an anionic OPE for the photooxidation of Aβ fibrils and compared its efficacy to the well-known but non-selective photosensitizer methylene blue (MB). Our results show that while MB photo-oxidized both monomeric and fibrillar conformers of Aβ40, OPE oxidized only Aβ40 fibrils, targeting two histidine residues on the fibril surface and a methionine residue located in the fibril core. Oxidized fibrils were shorter and more dispersed, but retained the characteristic β-sheet rich fibrillar structure and the ability to seed further fibril growth. Importantly, the oxidized fibrils displayed low toxicity. We have thus discovered a class of novel theranostics for the simultaneous detection and oxidization of amyloid aggregates. Importantly, the selectivity of OPE’s photosensitizing activity overcomes the limitation of off-target oxidation of traditional photosensitizers, and represents an advancement of PDT as a viable strategy to treat neurodegenerative disorders.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid aggregates, oligo-p-phenylene ethylene, photooxidation, fibril disassembly

Graphical Abstarct

Introduction

Developing photosensitizers that are selective for their intended targets would significantly advance their application in photodynamic therapy (PDT) in the treatment of numerous human diseases as off-target oxidation is a major drawback of current PDT technology.1, 2 Herein, we evaluate the selective photosensitizing activity of a novel class of conjugated polyelectrolytes, oligo-p-phenylene ethynylenes (OPEs), recently developed for detecting pre-fibrillar and fibrillar aggregated conformations of a range of amyloid proteins. Demonstration of OPE’s selective photooxidation of amyloid protein aggregates will enable further development of these compounds in theranostic applications for the simultaneous detection and treatment of protein misfolding diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

A major pathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease is the deposition of amyloid plaques composed of the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide,3, 4 which results from the abnormal misfolding and aggregation of the peptides into small oligomers that subsequently grow into large fibrils.5–8 The oligomers, which are transient and heterogeneous in nature, are known to be more neurotoxic than the mature fibrils. The mechanism of their toxicity is still unclear but their interactions with cell membranes leading to membrane destabilization and pore formation have been proposed to cause cell apoptosis.9–11 Aβ fibrils also play a key role in neurodegeneration through impairment of axonal transport12, 13 or by inducing the aggregation of tau protein and seeding the formation of neurofibrillary tangles.14 Additionally, amyloid aggregates are also involved in the rapid and predictable spatiotemporal disease progression through cell-to-cell transmission.15–17 Because of the central roles amyloid aggregates play in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis, their selective degradation and clearance is an attractive therapeutic approach.

Therapeutic strategies targeting amyloid aggregates, specifically Aβ plaques, are currently being investigated and include the use of enzymes (neprilysin18, insulin-degrading enzyme19, 20 and endothelin-converting enzyme21, 22) and anti-Aβ immunotherapy.23 These approaches have encountered challenges including meningoencephalitis induced by anti-Aβ immunotherapy24 and limitations including the non-selective degradation of the native Aβ peptide which is believed to have important physiological functions.25, 26

PDT is a therapeutic strategy, which can be spatially and temporally controlled, currently used in oncology27, 28 and dermatology.29 In PDT, a photosensitizer is exposed to light, generating singlet oxygen 1O2 through energy transfer (photosensitization type II) and/or free radicals (photosensitization type I) through electron transfer from an excited triplet state.30 These species then oxidize biological molecules, including proteins, lipids and amino acids, ultimately leading to cell death (e.g., oncology).31 A number of photosensitizers have been investigated for the photooxidation of Aβ including riboflavin,32 rose bengal,33 porphyrin-based molecules,34, 35 flavin-based compounds,32, 36 polymer37 and carbon nanodots,38, 39 metal complexes40–42, fullerene-based materials43, 44 and methylene blue (MB).45 These are non-selective and induce photo-oxidation of both Ab monomers and aggregates, as well as other biomolecules in the vicinity to the photosensitizers. For example, MB, a major FDA-approved photosensitizer used in oncology46, 47, has been investigated for the photo-oxidation of Aβ plaques both in vitro and in vivo.45 Aside from oxidizing both Ab monomers and fibrils, MB also non-selectively binds to and oxidize negatively charged proteins, lipids and nucleic acids47, leading to cellular apoptosis. These studies show that photo-oxidation of Ab monomers inhibits fibrillation32–34, which could be beneficial but likely also cause the loss-of-function of the peptide. Encouragingly, photo-oxidation of fibrils has been found to disassemble the fibrils into shorter structures displaying lower cellular toxicity,36 pointing to the potential that PDT targeted at the aggregated, pathogenic conformation of amyloid proteins can be a beneficial therapeutic approach. Several fibril-specific photosensitizers have recently been developed by Kanai and coworkers, including those based on fibril-binding dyes thioflavin-T and curcumin.36, 48, 49 Importantly, these studies found that photooxidation caused Ab aggregate degradation, which attenuated aggregate toxicity and reduced aggregate levels in the brains of AD mouse models.

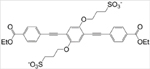

We recently showed that a class of novel oligo-p-phenylene ethynylene compounds (OPEs) selectively bind to and detect β-sheet rich amyloid fibrils.50–53 The small and negatively charged OPE12− (Table 1), characterized by one repeat unit with carboxyethyl ester end groups and sulfonate terminated side chains, detects fibrils made of two model amyloid proteins, insulin and lysozyme,50, 51 and two disease-relevant proteins, Aβ and α-synuclein.52 More importantly, OPE12− is also capable of selectively detecting the more toxic, pre-fibrillar aggregates of Aβ42 and α-synuclein.52 OPE’s superior sensor performance compared to that of the commonly used thioflavin T dye could be attributed to its high sensitivity to fluorescence quenching wherein the conjugated sensor is quenched in an aqueous solvent and binding to amyloid aggregates reverses quenching and leads to fluorescence recovery or turn-on.53–56 The ability of OPE12− to detect a wider set of protein aggregate conformations stems from the combination of different modes that leads to fluorescence turn-on of the OPEs, including hydrophobic unquenching, backbone planarization, and OPE complexation upon binding to amyloid aggregates.50, 51, 55

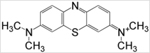

Table 1:

Structures of photosensitizers OPE12− and methylene blue (MB) used in this study

| Molecule name | Structure |

|---|---|

|

| |

| OPE12− |

|

| MB |

|

In addition to sensing, we recently showed that fluorescence turn-on of OPE12− from binding to the cationic detergent cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) is accompanied by the generation of a triplet state which subsequently photosensitizes 1O2.57 Importantly, as the unbound (quenched) state of OPE12− does not have photosensitizing activity, both fluorescence and photosensitizing properties of the OPE are selective, which makes this probe highly promising as a photosensitizer that is simultaneously controllable with light and selective for the pathogenic conformations of amyloid proteins. As photo-oxidation can potentially reduce the toxicity and promote the clearance of pathogenic amyloid aggregates, the simultaneous sensing and oxidation of the aggregates by OPEs represents a viable theranostic approach to simultaneously detect and treat protein misfolding diseases. Indeed, several studies have shown that photo-oxidation of Ab aggregates leads to their degradation in vivo.34, 45, 48, 58, 59

In this study, we evaluated the potential of OPE12− as a selective photo-oxidizer for Aβ fibrils over its monomeric counterpart and compared its activity to the well-known but non-specific photosensitizer MB. Oxidation of both Aβ monomers and fibrils with light exposure in the presence of OPE12− or MB was characterized. Oxidized amino acids on Aβ fibrils were identified and quantified, and the effect of fibril oxidation on fibril morphology, secondary structures, cell toxicity, and fibril seeding potency were evaluated.

Results

Spectroscopic features of OPE12− and MB in the presence of Aβ40 monomers and fibrils

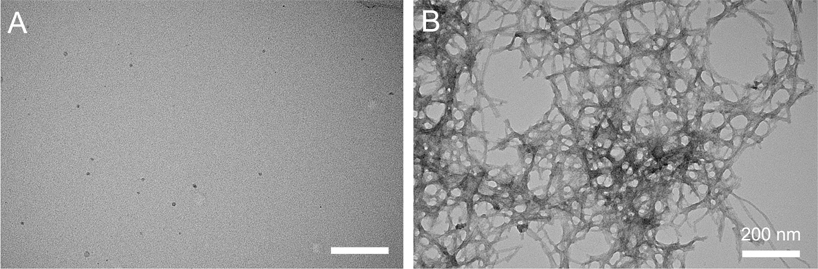

We have previously shown that the photosensitization activity of OPE12− is activated by complexation with oppositely charged detergent molecules.57 In this study, we first measured the absorbance and fluorescence spectra of both OPE12− and MB in the presence of monomeric or fibrillar Aβ40. Aβ40 fibrils were produced by incubating the monomeric peptide at 150 μM in pH 8.0 40 mM Tris buffer at 37 °C for 23 days. At this pH, the Aβ40 peptide has a net charge of −4.4.60 The unincubated Aβ does not show any features on TEM images (Figure 1A) indicating that the peptide is most likely monomeric, while incubated peptide showed large clusters of fibrils (Figure 1B). These fibrils were previously characterized to be rich in β-sheets while the monomeric peptides are mainly random coils.52

Figure 1:

TEM images of Aβ monomers (A) and fibrils (B). Freshly solubilized Aβ monomers do not show any features on the TEM image while after 23 days of incubation, Aβ formed large clusters of fibrils. Scale bar = 200 nm.

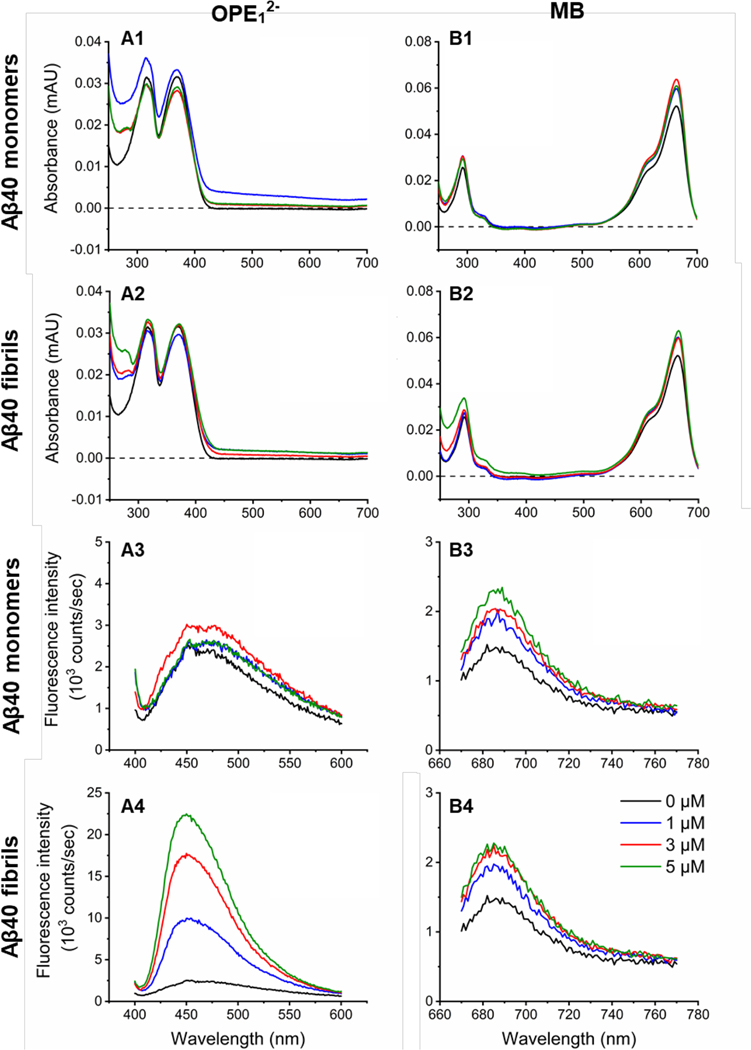

OPE12− and MB absorbance and emission spectra were measured in the presence of different concentrations of Aβ40 monomers and fibrils (Figure 2A1–2A2 and 2B1–2B2). OPE12− absorbance spectrum is characterized by two main peaks at 316 and 368 nm. In the presence of Aβ monomers or fibrils, OPE12− absorbance spectra did not exhibit significant changes in terms of peak positions and intensities, consistent with previous results.52 The absorption spectrum of MB, characterized by one main peak at 663 nm, increased by 14–22% in the presence of either Aβ monomers or fibrils, but the peak shape and position stayed unchanged.

Figure 2:

OPE12− displays a selective fluorescence turn-on in the presence of Aβ40 fibrils, while MB exhibits modest fluorescence increases in the presence of both monomeric and fibrillar Aβ40. Absorbance (1 and 2) and fluorescence emission spectra (3 and 4) of OPE12− (A) and MB (B) at 1 μM in the presence of varying concentrations of Aβ40 monomers or fibrils; 0, 1, 3 and 5 μM are shown in black, blue, red and green, respectively.

OPE12− and MB fluorescence were also characterized (Figure 2A3–2A4 and 2B3–2B4). At 1 μM, OPE12− is quenched in water and in the presence of 1 to 5 μM Aβ40 monomers, no significant change in emission intensity was observed (Figure 2A3). However, when added to 5 μM fibrillar Aβ40, OPE12− fluorescence emission blue shifted and drastically increased by more than 5-fold (Figure 2A4). These results indicate that OPE12− displays selective fluorescence turn-on upon binding to Aβ40 fibrils. MB is also a fluorescent molecule characterized by an emission peak centered at 685 nm. In the presence of both monomeric and fibrillar Aβ40, MB emission moderately increased by 30–50% (Figure 2B3–2B4), which could be due to its interaction to the negatively charged Aβ peptides causing MB to planarize, which prevents non-radiative relaxation decay of the photo-excited MB.45

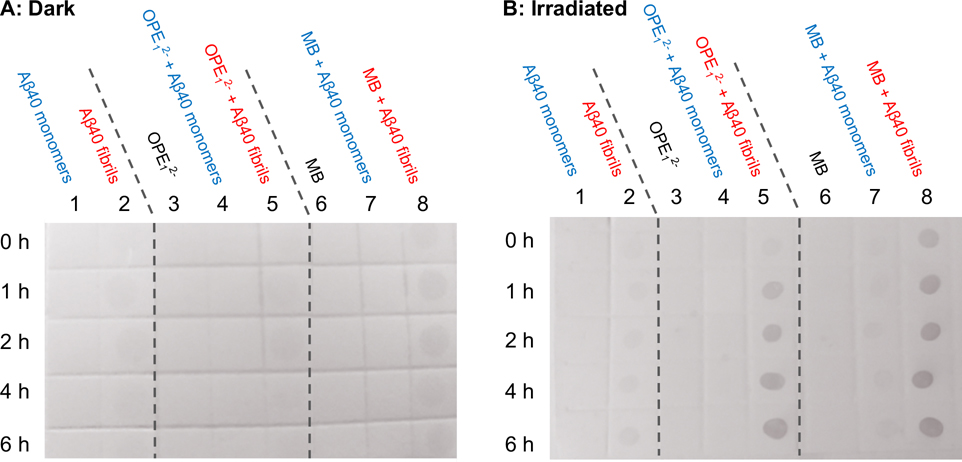

DNPH dot blot of Aβ40 oxidation

Having confirmed that OPE12− selectively binds Aβ fibrils over monomers, we then determined if OPE12− also only photo-oxidizes Aβ40 fibrils and not the monomers. The oxidation states of both Aβ40 conformers irradiated in the presence of OPE12− were characterized and compared to MB by monitoring the carbonyl content of the peptide using the DNPH (2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine) dot blot assay.61 The assay was carried out on 5 μM Aβ40 fibrils and monomers incubated for up to 6 hours either in the dark or with irradiation in the presence or absence of 1 μM photosensitizer (Figure 3). In the dark (Figure 3A), no photo-oxidation is detected in Aβ monomers incubated alone (column 1) or with a photosensitizer (columns 4 and 7) as no dots are visible. Aβ40 fibrils showed faint dots (Figure 3A, column 2) that did not become darker over time, indicating a low level of oxidation that might have occurred during the 23 days of incubation to produce fibrils. The low intensity dots could also be due to non-specific binding of DNPH to the dense fibrils. Light exposure alone also did not cause any oxidation of Aβ40 monomers or fibrils as no changes in their carbonyl contents were observed (Figure 3B, columns 1 and 2). However, in the presence of both photosensitizers and under light irradiation, Aβ40 fibrils quickly became oxidized, as evidenced by large increases in carbonyl content where the dots clearly became darker with irradiation time (Figure 3B, columns 5 and 8). Importantly, Aβ monomers irradiated in the presence of OPE did not become photo-oxidized as no dots were visible (Figure 3B, column 4). Monomers irradiated in the presence of MB showed small increases in carbonyl content as faint dots were visible (Figure 3B, column 7). Taken together, the dot blot assay shows that MB oxidized both monomers and fibrils, although to different extents, and OPE12− only oxidized Aβ fibrils under irradiation.

Figure 3:

Results from DNPH dot blot assay show that OPE12− selectively oxidized Aβ40 fibrils over monomers under light irradiation while MB non-selectively oxidized both oxidized Aβ40 fibrils and monomers. Aβ monomers (5 μM) and fibrils (5 μM) in the presence of OPE12− (1 μM) or MB (1 μM) at different incubation times in the dark (A) or under light irradiation (B). Dots indicate carbonyl groups of oxidized amino acids and the darker the dots, the higher the carbonyl content. Note that at 0 h, Aβ fibrils incubated with MB (column B8) showed a dot, which could be due to short light exposure during membrane preparation causing MB to photosensitize the oxidation of the fibrils.

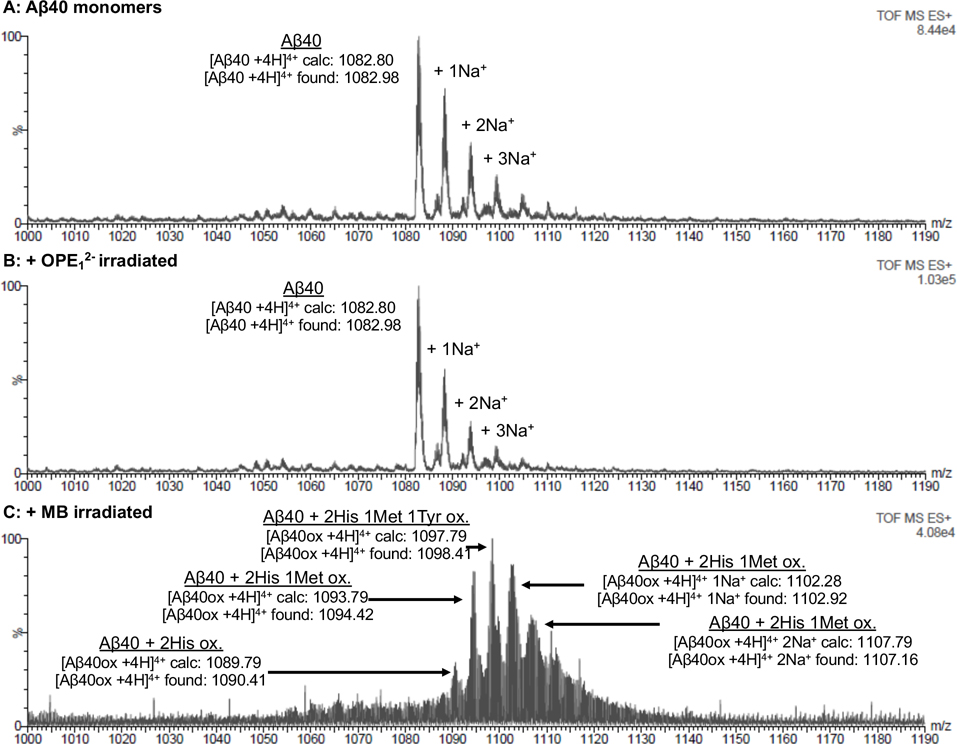

Mass spectrometry characterization of Aβ40 oxidation

The DNPH dot blot assay qualitatively showed that OPE12− selectively induced photo-oxidation of Aβ fibrils, but not monomers. To confirm this selectivity and quantitatively characterize the chemical changes, we turned to molecular techniques of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). Figure 4 shows ESI-MS spectra of Aβ40 monomer (25 μM) before and after irradiation in the presence of OPE12− or MB (1 μM). A quadruple charged ion (m/z of 1082) was observed for the Aβ40 monomers without irradiation (Figure 4A), which corresponds to the monomer’s expected and deconvolved mass of 4329. The ESI-MS analysis of Aβ40 monomer obtained after irradiation in the presence of OPE12− gave results similar to those obtained from the native Aβ40 monomer (Figure 4B), indicating that irradiation in the presence of OPE12− did not induce any mass changes in the peptide. In contrast, m/z peaks of Aβ monomers irradiated in the presence of MB (Figure 4C) showed a mixture of oxidized species. Oxidation of Aβ monomers was additionally confirmed by reverse phase HPLC (Figure S1) where the oxidized peptide eluted earlier in a broad peak revealing the presence of a mixture of more hydrophilic peptides. Our results are also consistent with previous reports on MB induced oxidation of monomeric Aβ.45

Figure 4:

Mass spectrometry confirms that while MB induces photo-oxidation of Ab monomers, OPE12− does not. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) chromatograms of 25 μM of Aβ40 monomers (A) and Aβ40 monomers irradiated for 4 hours in the presence of 1 μM of OPE12− (B) or MB (C). Non-irradiated Aβ40 monomer is characterized by a m/z peak at 1082.80 corresponding to [AB40 +4H]4+. A similar profile was found after irradiation in the presence of OPE12− indicating that OPE did not oxidize the monomeric peptide. After irradiation of Aβ40 in the presence of MB, a mixture of oxidized monomers with higher m/z values appeared.

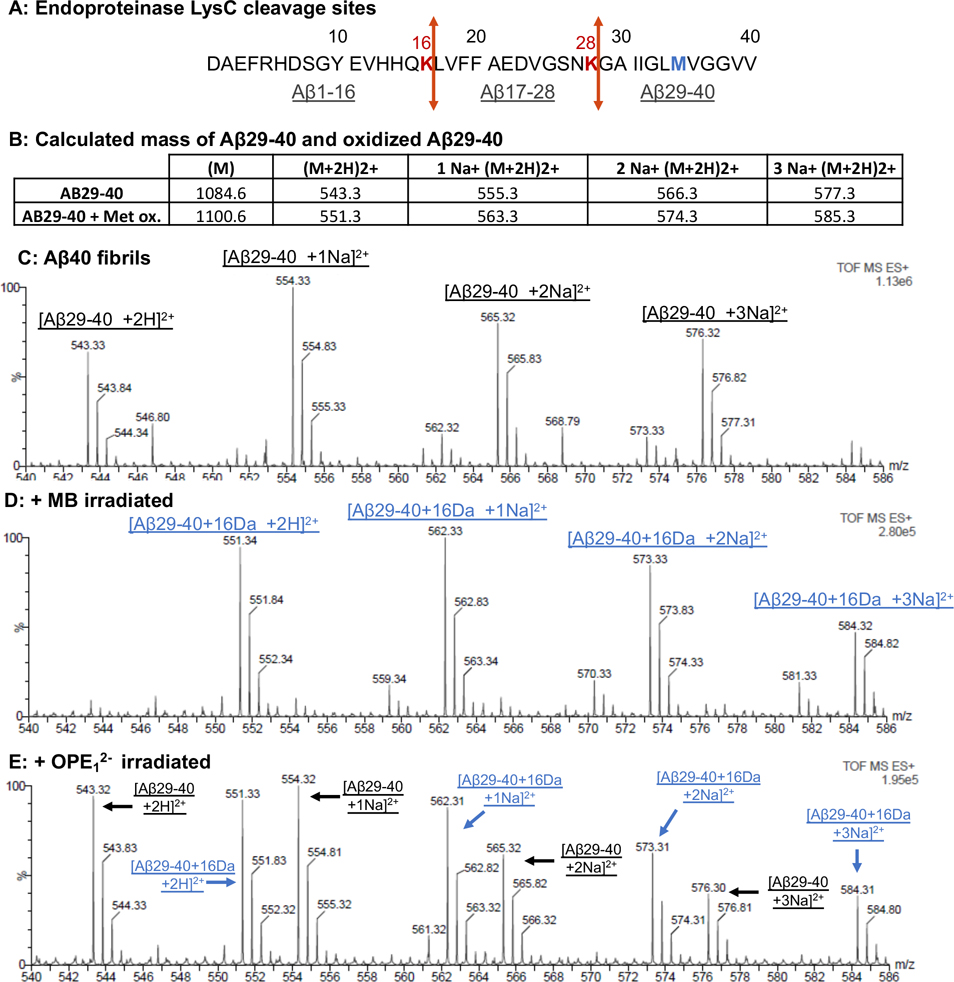

The oxidation of Aβ40 fibrils by both photosensitizers was also characterized by ESI-MS. Fibrils were first solubilized by enzymatic digestion with Endoproteinase LysC (Figure 5A) and the fragments were separated by reverse phase HPLC and analyzed with mass spectrometry; out of the three fragments, only the Aβ29–40 fragment which contains the oxidizable Met35 residue was well-resolved by mass spectrometry. The expected mass of the native and oxidized Aβ29–40 fragments are 1084.6 Da and 1100.6Da, respectively (Figure 5B). The size of these fragments in the presence of the Na adduct is shown in Figure 5B. After irradiating 25 μM Aβ40 fibrils in the presence of 1 μM MB, all Aβ29–40 peaks shifted by 16 Da (Figure 5D) indicating complete oxidation of the fragment. Met35 is likely oxidized as it is the only photo-oxidizable amino acid in this fragment36. After irradiating the fibrils with OPE12−, oxidized peaks were observed but the non-oxidized fragments were still present in the sample (Figure 5E). OPE12− thus only partially oxidized Met35 located in the core of Aβ fibrils while MB completely oxidized the residue.

Figure 5:

Mass spectrometry confirms that both OPE12− and MB induces photo-oxidation of Ab fibrils. A: Cleavage sites of Endoproteinase LysC in Aβ40 peptide as indicated in red. Cleavage product Aβ29–40 is the only well-resolved fragment from mass spectrometry. In blue is the suspected oxidized Met35 in the Aβ29–40 fragment. B: Calculated masses of the Aβ29–40 fragment with Met35 and oxidized Met35. C-E: ESI mass spectrometry chromatograms of the Aβ29–40 fragment generated from non-irradiated fibrils (C) and after 4 hours of irradiation in the presence of 1 μM MB (D) or OPE12− (E).

Amino acid analysis of oxidized Aβ40

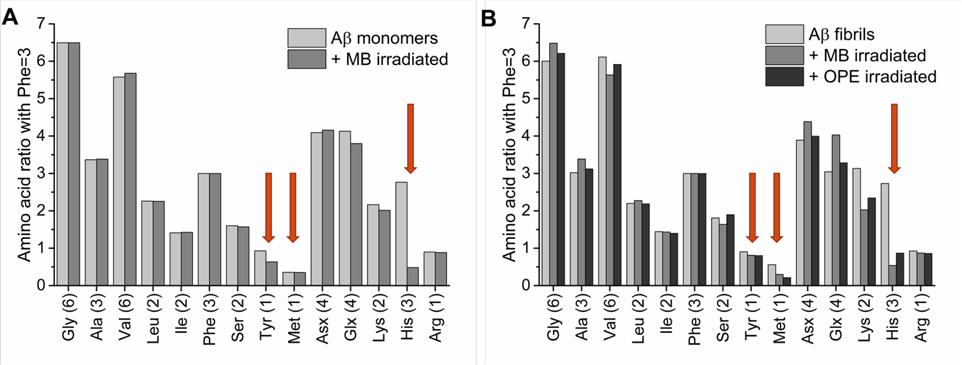

Amino acid analysis (AAA) was carried out to further confirm Aβ40 oxidation as well as to more completely identify oxidized amino acids (Figure 6). Aβ40 fibrils before and after light irradiation in the presence of either OPE12− or MB were analyzed. As we have confirmed that OPE12− does not oxidize Aβ monomers (Figures 3 and 4), only Aβ monomers irradiated in the presence of MB was analyzed (Figure 6A). In AAA, Aβ peptides were cleaved into individual amino acids by hydrolysis using 6 N HCl. Note that Met can become oxidized during acid hydrolysis62. For this reason, no conclusion was made regarding the effect of MB and OPE12− on methionine content from this analysis.

Figure 6:

His, Tyr, and Met residues are oxidized in Ab monomers by MB, while His and Met residues are oxidized in Ab fibrils by both MB and OPE12−. Amino acid analysis of 25 μM Aβ40 monomers (A) and fibrils (B) before and after 4-hour irradiation in the presence of 5 μM of MB or OPE12−. Amino acid content was determined by normalizing the raw data with known signal generated for phenylalanine. The x axis describes the type and number of amino acids expected in a single Aβ40 peptide. Glutamic acid and glutamine could not be differentiated by this analysis and they together appear as Glx. Similarly, aspartic acid and asparagine appear as Asx. Ile content is lower than expected (around 1.2 instead of 2), which might be explained by poor hydrolysis of the Ile-Ile bond. Red arrows indicate the three amino acids that can be photo-oxidized – Tyr, Met and His. Note that as Met can be partially oxidized during hydrolysis, the effect of MB and OPE12− on Met content cannot be conclusively made with this method.

AAA results show that the His content in Aβ40 monomers and fibrils irradiated in the presence of MB reduced from 3 to 1 (Figure 6A and 6B). Thus 2 out of the 3 His residues were oxidized by MB. Interestingly, Tyr content in Aβ40 monomers was only partially reduced, which is supported by the ESI-MS analysis (Figure 4), but stayed unchanged in Aβ40 fibrils after irradiation with MB. Aβ40 fibrils irradiated in the presence of OPE12− or MB (Figure 6B) showed reduced His content and no change in Tyr content. Combined with ESI-MS results, it can thus be concluded that two His, one Tyr, and one Met residues were oxidized in Aβ40 monomers but only two His and one Met residues were oxidized in Aβ40 fibrils. The oxidation pattern in Aβ40 monomers is consistent with those reported for Aβ42.32 The difference is that Tyr is oxidized only in Aβ40 monomers, but not in fibrils, which could be due to differences in the residue’s solvent exposure in the two different Aβ conformations. Tyr oxidation has been found to depend on solvent exposure63. For example, Tyr residues in insulin were found to be non-oxidized in the native hexameric conformation but oxidized in an 8 M urea denatured state64. Denaturation increases solvent accessibility and thereby the activity of a photosensitizer. In the disordered Aβ monomer, Tyr is more accessible to MB photosensitization whereas in the fibrillar state, Aβ fibril has a core that is inaccessible to the solvent, reducing photo-oxidation of Tyr residues by both MB and OPE.

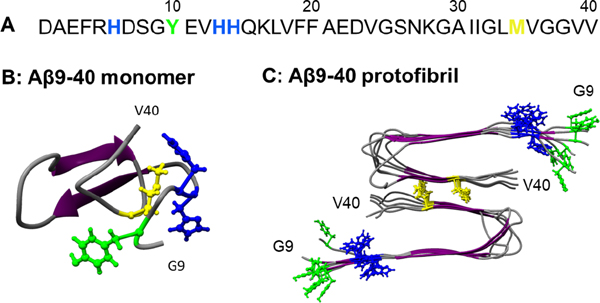

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of OPE12− binding sites on Aβ40 protofibrils

Having confirmed that OPE12− selectively oxidized 2 out of 3 His residues and partially oxidized the Met residue on Aβ fibrils, we then sought to understand the photo-oxidation pattern of this photosensitizer by analyzing binding sites of OPE on the fibril and their proximity to oxidizable residues. It is known that singlet oxygen species generated by a photosensitizer rapidly decays and diffusion distance on the order of 0.01 – 0.02 μm65 to over 1 μm66 has been reported. Singlet oxygen’s reactivity additionally depends on their environment such as solvent accessibility.67 We utilized all-atom MD simulations to identify OPE binding sites on an Aβ protofibril and analyzed the distances of the oxidizable residues to the bound OPEs.

Aβ40 contains 5 amino acids that can be photo-oxidized: His6, His13, His14, Tyr10 and Met35 (Figure 7A). A protofibril made of 24 Aβ9–40 peptides was obtained from the 2LMN68 Protein Data Bank (PDB) file (Figure 7C). The first 8 amino acids remained disordered in the fibril and were not represented in this structure. The structure of a disordered Aβ9–40 monomer was obtained by first removing a peptide from the protofibril PDB structure and then performing energy minimization and equilibration for 100 ns (Figure 7B). The locations of oxidizable amino acids within the monomer and protofibril are shown in Figure 7B and 7C, respectively. All 4 oxidizable amino acids of Aβ9–40 are freely exposed to the solvent when the peptide is monomeric. In the protofibril, Met35 is buried inside the β-sheet core while His13, His14 and Tyr10 are located on the surface of the protofibril. His6 is in the disordered N-terminal region and not represented on these structures of Aβ9–40.

Figure 7:

Oxidizable amino acids in the Aβ40 sequence (A) and their locations in an Ab9–40 monomer (B) and protofibril (C). Met, Tyr, and His residues are shown in yellow, green, and blue, respectively.

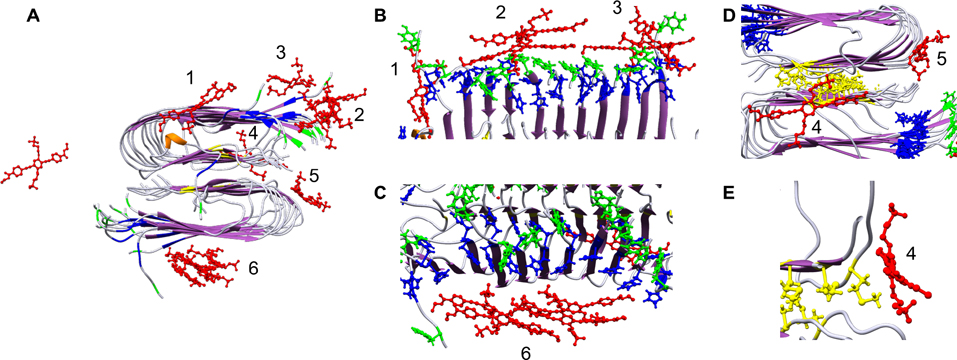

OPE12− binding sites on the Aβ40 protofibril were analyzed by MD with 12 OPE molecules placed around the protofibril. After 100 ns of simulation, 11 out of 12 OPE became bound to the protofibril at six different binding sites either as single OPE molecules (sites 1, 4 and 5) or as OPE complexes (sites 2, 3 and 6) (Figure 8A). This binding pattern is consistent with what we have previously reported in a MD simulation study,69 where hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions were the main driving forces for binding. Three of the binding sites were located on the β-sheet rich protofibril surface (sites 2, 3 and 6; Figure 8B and C), one was located on the β-turn (site 5; Figure 8D), and the last two were at the ends of the protofibril (sites 1 and 4; Figure 8B and E). Tyr and His residues were located within 4 Å of OPE12− in binding sites 2, 3, 5 and 6, which make them highly susceptible for oxidation by singlet oxygen. In contrast, Met was buried inside the core of the fibril which makes it further away from singlet oxygen generated by surface bound OPEs and possibly less prone to oxidation due to its reduced solvent accessibility.67 The closest bound OPE12− at site 4 on one end of the protofibril was 5.6 Å away from Met35. The other bound OPEs were further away from Met (between 19.8 – 41.6 Å), which might explain the partial oxidation of Met35 observed.

Figure 8:

Positions of 12 OPEs (red) placed around an Ab protofibril after 100 ns of all atom MD simulation (A) show 11 OPEs bound to the protofibril at 6 binding sites. B, C, D, E and F show different zoomed-in views of the 6 binding sites where OPEs bind both as single OPEs or complexes of OPE. Methionine (M), tyrosine (Y) and histidine (H) are shown in yellow, green and blue, respectively. The remainder of the protofibril is shown in ribbon representation with β-sheets colored purple and random coil in white.

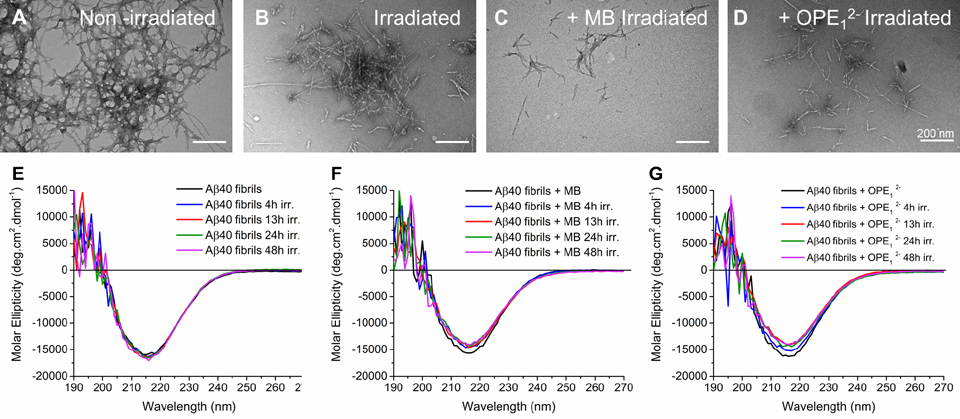

Effect of oxidation on Aβ40 fibril morphology and secondary structures

For PDT to be a viable treatment option, the structural and functional properties of the photooxidation products need to be characterized to ensure that they will not be harmful. The effect of oxidation on the fibril’s morphology and secondary structures were assessed by TEM imaging and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, respectively. As shown in Figure 9A, untreated Aβ40 fibrils were long and in large clusters. After irradiation in the absence of a photosensitizer, the fibril clusters appeared smaller, but were still present (Figure 9B). When the fibrils were irradiated with either MB or OPE12−, the clusters were largely gone and shorter fibrils were observed (Figure 9C and D).

Figure 9:

Photo-oxidation led to some breakdown of fibrils, but did not alter their secondary structures. TEM images and CD spectra of Aβ40 fibrils irradiated in the absence or presence of a photosensitizer. TEM images of 5 μM Aβ40 fibrils: non-irradiated (A), irradiated for 4 hours (B), irradiated in the presence of MB for 4 hours (C), and irradiated in the presence of OPE12− for 4 hours (D). CD spectra of 50 μM Aβ fibrils irradiated for various times: irradiated alone (E), irradiated with 10 μM MB (F), and incubated 10 μM OPE12− (G).

CD spectra of Aβ40 fibrils showed positive and negative peaks at 192 nm and 215 nm, respectively, indicating a β-sheet rich structure. Irradiation of the fibrils did not affect their secondary structures (Figure 9E). Irradiation in the presence of OPE12− or MB (Figure 9G and H) also did not result in significant changes to the fibril’s secondary structures; the shorter fibrils remained rich in β-sheets. Taken together, our results indicate that photo-oxidation induced some breakdown of fibrils, but did not alter their β-sheet rich secondary structures.

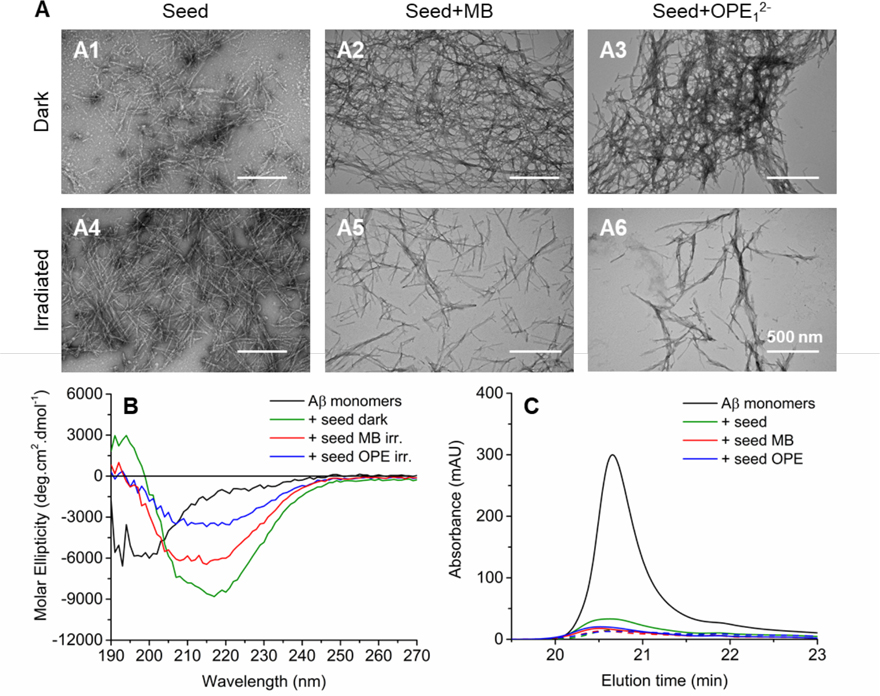

Effect of oxidation on Aβ40 fibril seeding potency

The ability to seed aggregation is a prominent property of amyloid fibrils as fibril elongation by the addition of monomers is likely the primary aggregation pathway for Aβ40.70–72 The effect of oxidation on the seeding potency of Aβ fibrils was evaluated by monitoring Aβ40 monomer (50 μM) aggregation in the presence of 2.6 μM of non-oxidized and photo-oxidized fibril seeds after 72 hours of incubation at 37°C (Figure 10). Fibril seeds were prepared by sonicating mature Aβ40 fibrils in a bath sonicator for 10 minutes (Figure S2).

Figure 10:

Oxidized fibrils largely retain the ability to seed Ab monomer aggregation. A: TEM images of 50 μM Aβ40 monomers incubated with 2.6 μM non-oxidized (dark) or oxidized (irradiated) fibril seeds for 72 hours at 37 °C. Seeds were prepared by sonicating fibrils treated with MB or OPE12− (5 to 1 Aβ to photosensitizer molar ratio) in the dark or under irradiation for 4 hours. B: CD spectra of Aβ40 monomers before incubation (black) and after 72 hours of incubation in the presence of non-oxidized fibril seeds (green) or oxidized fibril seeds generated by MB (red) or OPE12− (blue). C. SE-HPLC chromatograms of Aβ40 monomers before incubation (black) and after 72 hours of incubation in the presence of non-irradiated fibril seeds (green) or fibril seeds in the presence of MB (red) or OPE (blue). Fibril seeds were either kept in the dark (solid line) or irradiated for 4 hours (dashed line) before seeding Aβ40 monomers. For HPLC, samples were first centrifuged to remove any insoluble aggregates before injecting onto the size exclusion column.

As shown in the TEM images, Aβ40 monomers formed large clusters of fibrils after 72 hours of incubation in the presence of fibril seeds or fibrils seeds that were irradiated for 4 hours (Figure 10A1 and 10A4). When the seeds were exposed to MB or OPE12− in the dark, the seeding potency was not affected as similar mature fibrils were observed after 72 hours of incubation (Figure 10A2 and 10A3). Fibril formation still occurred after incubating the monomers with oxidized seeds, either by MB or OPE. However, the fibrils produced are shorter and no large fibrillar clusters were observed (Figure 10A5 and 10A6). These fibrils were further characterized by CD spectroscopy. As shown in Figure 10B, fibrils produced in the presence of non-oxidized seeds (green) were rich in β-sheet as evidenced by the presence of a negative and positive CD signals at around 195 nm and 218 nm, respectively. Fibrils seeded by oxidized fibrils (MB in red and OPE12− in blue) also contained β-sheets. However, the CD signal was weaker. The percentages of Aβ40 monomers remaining after seeded incubation were determined by SEC (Figure 10C). About 18% monomers remained in the samples seeded with non-irradiated and irradiated seeds (Figure 10A1 and A4). Samples incubated with photo-oxidized seeds (Figure 10C: MB: dashed red line and OPE12−: dashed blue line) contained about 10% monomers after 72 hours of incubation. As photo-oxidation led to the degradation of fibrils into smaller fibrils, it is not surprising that the smaller, but more numerous, oxidized fibril seeds led to more aggregation of the Aβ monomers compared to non-oxidized seeds. Taken together, photo-oxidized fibrils did not show reduced seeding potency, but produced fibrils that were shorter and contained less β-sheets.

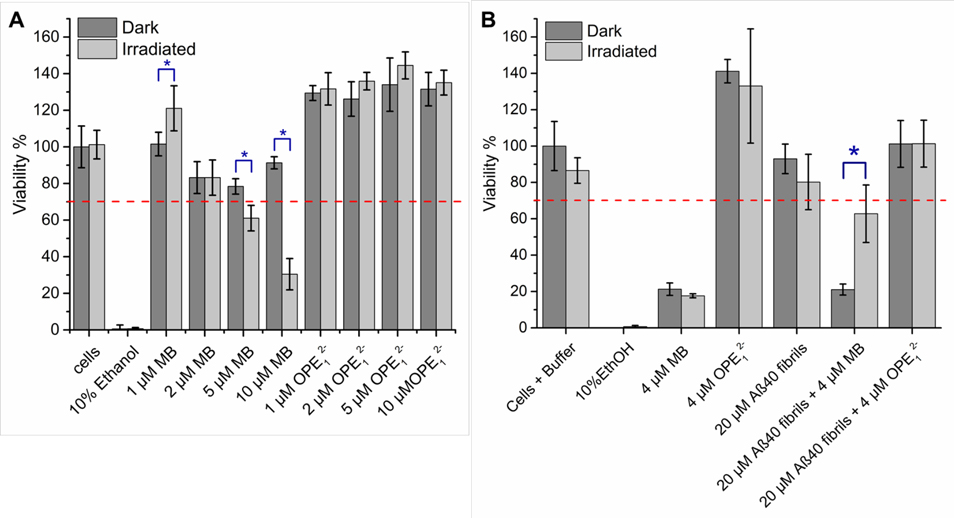

Cell toxicity of oxidized Aβ40 fibrils

We have shown that both photo-oxidation by OPE12− and MB produced shorter fibrils that are still rich in β-sheets and able to seed further aggregation. It is essential to additionally investigate the effect of oxidation on fibril neurotoxicity as smaller oligomers and protofibrils are widely believed to be more toxic than mature fibrils. Furthermore, whether the photosensitizers are toxic to cells also need to be evaluated.

Toxicity of OPE12− and MB on SHSY-5Y neuroblastoma cells was evaluated at different concentrations (1–10 μM) both in the dark and with a 5-min irradiation. After irradiation, cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 hours, after which cell viability was determined by the MTS assay. As shown in Figure 11A, viability of cells was not affected by irradiation alone. When cells were treated with various concentrations of either MB or OPE12− and kept in the dark, cell viability was close to 100% indicating that both compounds were not cytotoxic at concentrations up to 10 μM. After light irradiation in the presence of varying concentrations of MB, cell viability was lower than the 70% threshold generally considered for cytotoxicity73 at MB concentrations higher than 5 μM. Note that cell viability was significantly lower in the irradiated samples compared to those kept in the dark (p-value ≤ 0.01). These results indicate that MB is not toxic for up to 10 μM in the dark, but becomes cytotoxic when exposed to light at concentrations higher than 5 μM. This cytotoxicity is likely due to light induced singlet oxygen generation by MB, which induced non-specific oxidation and led to cell death. In contrast, OPE12− did not reduce cell viability after irradiation even at 10 μM. The lack of toxicity indicates that OPE did not exhibit photosensitizing activity in the presence of the neuroblastoma cells when irradiated. Given that OPE’s photosensitizing activity is turned-on by binding, this result also indicates a lack of non-specific binding of the OPE to the cells. Results from this assay point to the potential of the OPE as a selective, in addition to being controllable, photosensitizer with minimal off-target oxidation and toxicity.

Figure 11:

OPE12− and OPE-oxidized fibrils are not cytotoxic. (A) Viability of SHSY-5Y neuroblastoma cells incubated for 24 hrs in the presence of varying concentrations of OPE12− or MB in the dark or after 5 min irradiation. (B) Viability of SHSY-5Y neuroblastoma cells incubated for 48 hr in the presence of MB, OPE12− or oxidized Aβ40 fibrils. In the irradiated condition, samples were exposed to light for 4 hrs prior to adding to SHSY-5Y cells. Cell viability was normalized to the negative control of untreated cells. Error bars represent standard deviations of quintuplet experiments. Red dashed line represents 70% viability threshold commonly used to define cytotoxicity73. Blue asterisks indicate significant differences between the dark and irradiated incubations (t-test with a p-value ≤ 0.01).

The effect of photo-oxidation on Aβ40 fibril toxicity was also investigated (Figure 11B). Fibrils were incubated at 50 μM in the dark or under irradiation for 4 hours in the absence or presence of 10 μM OPE12− or MB. After the 4-hour incubation, fibrils were added to SHSY-5Y cells at 20 μM with 4 μM photosensitizer. The cells were then incubated in the dark for 48 hours at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and cell viability was determined by MTS assay. As additional controls, cells were treated with 4 μM MB or OPE12− and incubated for 4 hours in the dark or under irradiation, prior to 48-hour incubation in the dark. In the presence of 4 μM MB, cell viability decreased by 80% for both dark and light conditions, indicating that MB is cytotoxic with a longer irradiation time and incubation period. Toxicity of the non-irradiated MB treatment might be caused by singlet oxygen generation when the samples were exposed to light during preparation. In contrast, the presence of 4 μM OPE12− did not cause any reduction in cell viability in both dark and light conditions, which further confirms that the OPE is not cytotoxic even after 4 hours of irradiation and 48 hours of incubation. At 20 μM, Aβ40 fibrils and fibrils irradiated for 4 hours were also not cytotoxic. However, the standard deviation of cell viability in the presence of irradiated fibrils was larger (~15% vs. ~8%) which could be caused by the shorter fibrils produced with irradiation. Cells exposed to fibrils oxidized by OPE12− displayed similar viability compared to the non-irradiated fibrils indicating that the shorter OPE-oxidized fibrils were not cytotoxic.

Interestingly, cells treated with fibrils incubated with MB in the dark showed around 20% viability, comparable with cells treated with just MB. These results are consistent in that fibrils are not toxic and the toxicity in these samples are likely caused by short light exposure during sample preparation that activated MB photosensitizing activity. Surprisingly, cells treated with fibrils irradiated with MB showed a higher ~60% viability. Although the exact cause for this is not known, we hypothesize that the lower toxicity of the irradiated samples is due to MB photo-bleaching or photodegradation during the 4 hours of irradiation, as discoloration of the sample was observed after irradiation. Note that in both sets of SHSY-5Y viability experiments, greater than 100% viability was consistently observed when the cells were treated with OPE, although the cause of this increased viability is not yet clear.

Discussion

PDT is an attractive method to photo-oxidize amyloid aggregates, which could promote their disassembly and clearance to treat neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. The feasibility of such an approach hinges on the discovery of photosensitizers that are selective for the pathogenic, aggregated conformations of amyloid proteins to avoid off-target oxidation that can lead to the loss-of-function of the native amyloid proteins or the death of surrounding cells or tissue. Additionally, the photosensitizer needs to be non-toxic, as do their photo-oxidized products. In this study, we demonstrate that a novel phenylene ethynylene-based oligomer OPE12− selectively and controllably photo-oxidizes the fibrils, but not the monomers, of Aβ40. The oxidized fibrils retain its β-sheet rich structures and fibril-seeding ability, and are nontoxic.

OPE12− selectively and controllably photo-oxidizes Aβ40 fibrils over monomers

Three complementary techniques were used to evaluate the oxidation of Aβ40 monomers and fibrils exposed to light in the presence of OPE12− or the well-known, but nonselective MB. DNPH dot-blot (Figure 3), ESI-MS (Figures 4 and 5), and amino acid analysis (Figure 6) results revealed that OPE12− is a light-controllable photosensitizer that selectively oxidizes Aβ40 fibrils over its monomeric counterpart. The selective oxidation of the fibrillar conformation arises from the high binding affinity of OPE12− to the fibrils (Kd = 0.70 ± 0.1 μM)52 and its weak interaction with the monomers as shown by a lack of OPE fluorescence turn-on (Figure 2B). In contrast, MB oxidizes both Aβ40 monomers and fibrils under irradiation. This lack of selectivity of MB may be attributed to its non-specific interactions to the negatively charged Aβ in both conformations as MB has been previously reported to interaction with monomeric Aβ42 with a dissociation constant Kd of 48.7 ± 3.6 μM.45

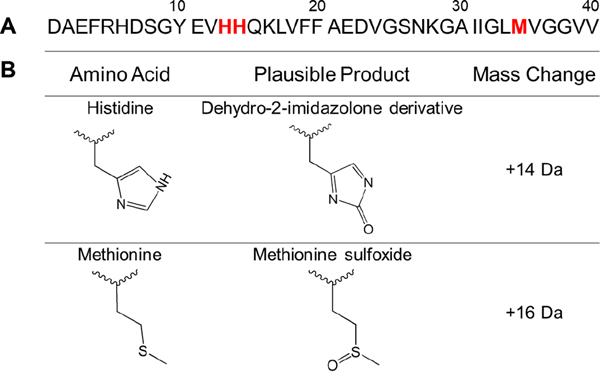

OPE12− photo-oxidizes His13, H14 and Met35 residues in Aβ40 fibrils

In Aβ40, five amino acids can be photo-oxidized: 3 histidines (His6, His13, His14), 1 tyrosine (Tyr10) and 1 methionine (Met35)61. Amino acid analysis (Figure 6) and mass spectrometry (Figure 5) showed that light treatment in the presence of OPE12− or MB led to the oxidation of 2 His and 1 Met in Aβ40 fibrils (Figure 12). Of the 3 histidine residues, His13 and H14 are likely the oxidized residues as previous studies have shown that these residues in Aβ42 become photo-oxidized in the presence of thioflavin-T74 and riboflavin32, but not His6. Interestingly, OPE12− only partially oxidized Met35 which might be due to a lower singlet oxygen quantum yield compared to that of MB, which is about 0.5.47 However, as Met35 is located in the core of the fibril (Figure 8), its accessibility to singlet oxygen and subsequent reaction oxygen species may be reduced compared to fibril-surface exposed histidine residues. To better understand the difference between the photosensitizing activities of OPE12− and MB, their singlet oxygen quantum yields could be characterized by luminescence or photochemical methods75. Interestingly, Tyr10 in fibrils is not oxidized by either photosensitizer despite its close proximity to His13 and His14 which were likely both oxidized. The low propensity of tyrosine to be photo-oxidized may be due to its lower rate constant (K) for 1O2 quenching compared to histidine and methionine (KHis = 4.6 × 10−7 > KMet = 1.3 × 10−7 > KTyr = 0.2–0.5 × 10−7 M−1s−167, 76.

Figure 12:

Plausible photo-oxidation sites on Aβ40 (A) and products of oxidation (B).

OPE12− photo-sensitization disassembles Aβ fibrils into β-sheet rich, non-toxic, and seeding-competent protofibrils

Aβ40 fibrils are highly thermodynamically stable77, which makes their degradation challenging. Photo-oxidation of Aβ40 fibrils modifies a few key residues, namely Met35, His13, and H14, those hydrophobic intermolecular interactions stabilize the fibrillar conformation. The addition of a hydrophilic oxygen from photo-oxidation is expected to disrupt these hydrophobic interactions and possibly lead to fibril destabilization.78 To better understand the effect of oxidation on fibril morphology and secondary structures, we analyzed oxidized fibrils by TEM imaging and CD spectroscopy (Figure 9), respectively. Results show that irradiation in the presence of MB or OPE12− broke clusters of long Aβ40 fibrils into shorter fibrils still rich in β-sheets. Fibril disassembly could be caused by the partial oxidation of Met35 located in the core of the fibril (Figure 7C), which stabilizes the long fibrils78. As protofibrils and oligomers are known to be more toxic than fibrils9–11, 79, we evaluated cell toxicity of the oxidized fibrils (Figure 11). We observed that OPE-oxidized fibrils do not display higher toxicity compared to non-oxidized fibrils indicating that using PDT to break down the fibrils will not generate more toxic species. Additionally, OPE12− is not cytotoxic to cells, even under irradiation, which further supports their use in PDT. The seeding potency of oxidized fibrils was also characterized (Figure 10C). Oxidized fibril seeds maintained their seeding capacity, however they produced shorter fibrils that were less rich in β-sheet compared to mature non-oxidized fibrils. Taken together, we have shown that OPE12− photosensitized the oxidation of Aβ fibrils, while minimally perturbing the β-sheet structure or functional properties (seeding capacity and cytotoxicity) of the fibrils. This is indeed desirable if oxidation can trigger the degradation and clearance of fibrils by endogenous protein degradation pathways.

Conclusions

Oligomeric conjugated polyelectrolytes such as OPE12− have been recently shown to selectively and sensitively bind to aggregated conformations of a number of amyloid proteins over their monomeric conformers.52 Concomitant with aggregate binding is the turn-on of OPE’s fluorescence and singlet oxygen generation,57 suggesting that OPEs are potentially superior photosensitizers for the PDT treatment of protein misfolding diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. In this study, we carry out a proof-of-concept investigation of the controlled and selective photooxidation of Aβ40 fibrils over monomers by OPE12− and compared its photosensitizing activity to MB. We showed that MB non-selectively oxidizes both Aβ monomers and fibrils, while OPE12− only oxidizes Aβ fibrils. Three amino acids on the fibril are oxidized by OPE photosensitization, His13, His14 and Met35, which proceeds through binding induced generation of 1O2. Photooxidation causes fibrils to disassemble into shorter, but non-toxic oxidized fibrils. The oxidized fibrils also retain their ability to seed further Aβ40 aggregation, albeit fibrils of a lower β-sheet content were produced. Overall, this study demonstrates the ability of OPE12− to controllably and selectively photo-sensitize the oxidation of Aβ fibrils. The selective nature of OPE’s photosensitizing activity overcomes the major drawback of off-target oxidation from using conventional photosensitizers such as MB in PDT. Combined with its selective fluorescence sensing capabilities, our results from this study support the further development of OPEs as potential theranostics for the simultaneous detection and clearance of amyloid aggregates in protein misfolding diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. While the OPE sensor and photosensitizer can be utilized for in vitro studies and in some in vivo neurodegeneration disease models, for example, C. elagans where the nematode is anatomically transparent,80 they are not yet suitable for most in vivo applications because of low tissue penetration at the OPE’s excitation wavelength between 300–400 nm. Future development of these compounds will need to shift the excitation to longer wavelengths, in the near infrared “optical window” of 650–1200 nm, and/or developing the use of light guides81, 82 such as fiber optics or implantable optoelectronic devices such as microLED83 to activate the OPEs.

Experimental Methods

Materials

Synthetic amyloid-β (1–40) (Aβ40) was purchased from Peptide 2.0 (Chantilly, VA). Tris was obtained from BioRad (Hercules, CA). Sodium chloride (NaCl), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), sodium azide, acetonitrile, methanol and hydrochloride acid (HCl) were acquired from EMD Millipore (Burlington, MA). SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) F12 media, fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and Tween® 20 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Penicillin-streptomycin (PS) at 10,000 U/mL, AP Rabbit anti-Goat IgG (H+L) secondary antibody and 1-Step NBT-BCIP substrate were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). The CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay was purchased form Promega (Madison, WI). Goat anti-DNP primary antibody was acquired from Bethyl (Montgomery, TX). OPE12− was synthesized and purified by previously published procedures55. MB was purchased from Avantor (Radnor, PA). 400 mesh copper grids covered by a Formvar/Carbon film (5–10 nm) were obtained from Ted Pella (Redding, CA) and 2% aqueous uranyl acetate was purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA).

Aβ40 monomers and fibrils preparation

Lyophilized Aβ40 peptide was solubilized in DMSO at 50 mg/mL. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant was removed and stored at −70 °C. Monomeric Aβ was prepared by diluting the stock solution to 150 μM with a pH 8.0 40 mM Tris buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.01% sodium azide. Fibrils were made by incubating Aβ monomers at 37 °C for 23 days52. Photo-oxidation of both Aβ40 monomers and fibrils by either OPE12− or MB was performed by incubating the peptides with a photosensitizer at a peptide to photosensitizer molar ratio of 5 to 1 or 25 to 1. The mixtures were either kept in the dark or exposed to light in a photochamber (Luzchem Research Inc.) using 10 LZC-VIS Sylvania Cool White bulbs which emitted light between 350 and 700 nm at 8 W and 5.5 mW/cm2 per lamp (Technical Release from LuzChem). Samples were then irradiated for 0–6 hours for the various experiments described below.

Seeding experiment preparation

Stock Aβ at 50 mg/mL in DMSO was diluted to 50 μM using 50 mM phosphate buffer (PB) with 100 mM NaCl at pH 7.4. This Aβ40 monomer solution was either incubated alone or in the presence of 2.6 μM Aβ40 seed protofibrils at 37 °C for 72 hours. Three different seed protofibrils were prepared from mature fibrils: (1) Aβ40 fibrils incubated for 4 hours in the dark or under irradiation, (2) Aβ40 fibrils incubated in the presence of OPE12− for 4 hours (5 to 1 molar ratio Aβ to photosensitizer) in the dark or under irradiation and (3) Aβ40 fibrils incubated in the presence of MB for 4 hours (5 to 1 molar ratio Aβ to photosensitizer) in the dark or under irradiation. Irradiation was carried out in a photo-chamber (Luzchem Research, Inc.) containing 10 bulbs (350–700 nm). Seed protofibrils were then prepared by sonicating the above incubated fibrils for 10 minutes using a 550T Ultrasonic Cleaner (VWR International, Radnor, PA). Note that the mature fibrils prepared by 23-day incubation were not processed, i.e., washed or undergone any separation, prior to the 4-hour incubation and sonication to produce seed protofibrils.

Absorbance and fluorescence measurements

OPE12− and MB absorbance and emission spectra were recorded at 1 μM in the presence of varying concentrations of Aβ40 (0, 1, 3 and 5 μM) in pH 7.4 10 mM PB after 30 minutes of incubation in the dark at room temperature. Absorbance spectra were obtained with a Lambda 35 UV/VIS spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) in a quartz cuvette (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Emission scans were obtained at excitation wavelengths of 390 nm and 660 nm for OPE12− and MB, respectively, and were recorded using a PTI QuantaMaster 40 steady state spectrofluorometer (HORIBA Scientific, Edison, NJ) in a quartz cuvette (Starna cells Inc., Atascadero, CA).

DNPH dot blot

0.2 μm PVDF membrane (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) was soaked in 100% methanol for 15 seconds, then in water for 5 minutes, and finally in pH 7.4 phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TPBS) for 15 min. After incubating Aβ40 monomers or fibrils with a photosensitizer (5 μM protein with 1 μM photosensitizer) in the dark or under illumination for up to 6 hours, samples were blotted onto the membrane four times at 1 μL each and let dry for 15 minutes. DNPH derivatization of protein carbonyl groups was carried out as previously described84. Briefly, the membrane was equilibrated in 2.5 N HCl for 5 minutes before transferring to a 20 mM DNPH solution in 2.5 N HCl for 5 minutes. Excess DNPH was then washed away with three 5 mL aliquots of 2.5 N HCl and then 5 mL of 100% methanol. The membrane was then immuno-stained. First the membrane was submerged in the blocking buffer (pH 7.4 phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20) for 24 hours at room temperature. The membrane was then washed six times with a washing buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) for 5 min per wash before applying the goat anti-DNP primary antibody diluted at 1:10,000 in blocking buffer for 2 hours under agitation in the dark. The membrane was then washed 6 times with the washing buffer before applying the rabbit anti-goat IgG secondary antibody, alkaline phosphatase (AP) conjugate diluted at 1:10,000 in blocking buffer, for 2 hours under agitation in the dark. The membrane was washed 3 time with the washing buffer and 3 time with PBS before revealing the dot blot with the 1-Step NBT-BCIP substrate. Once the dots appeared, the membrane was rinsed twice with distilled water for 2 minutes each under agitation and was dried overnight before imaging the membrane.

Amino acid analysis (AAA)

Samples containing 25 μM Aβ40 and 5 μM photosensitizer were kept in the dark or were irradiated for 4 hours. After light treatment, samples were sent to the Molecular Structural Facility at University of California Davis for amino acid analysis (AAA) using a sodium citrate buffer system. Briefly, this analysis consisted of drying 100 μL of 25 μM peptide samples and performing a liquid phase hydrolysis using 200 μL 6 N HCl containing 1% phenol for 24 hours at 110 °C. After hydrolysis, the protein was dried and added to norleucine, an internal standard, to reach a final volume of 200 μL. The samples were analyzed on a cation-exchange chromatography column using a L-8800 Hitachi analyzer and a post column ninhydrin reaction detection system.

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS)

Both monomeric and fibrillar proteins were desalted first using the Amicon Centrifugal Filter (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) before analyzed by ESI-MS. 250 μL of peptide at 150 μM was loaded onto the filter to which 4 mL of PB was added before centrifuging the filter at 3500 rpm for 20 min. After four washing steps using PB buffer, the retentate was collected and volume adjusted to 250 μL. The protein concentration was then determined using the Bradford protein concentration assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Desalted Aβ40 monomer and fibril samples were analyzed by ESI-MS after 4 hours of irradiation in the absence and presence of MB or OPE12− (25 μM protein with 1 μM photosensitizer). Before analysis, Aβ40 fibrils were digested using the Endoproteinase Lys C enzyme (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) at a 1/50 (w/w) enzyme to protein ratio. The digestion was performed by incubating the samples at 37 °C for 16 hours. Digested Aβ40 monomers and fibrils were diluted to 5 μg/mL using acetonitrile with 1% TFA and were analyzed under continuous ESI-MS spray on SYNAPT G2 Mass Spectrometer. This analysis was performed in a positive mode by using the following settings: Capillary = 3.5 kV, sampling cone = 251, extraction cone = 5, source temperature = 120 °C, desolvation temperature = 300 °C, and desolvation gas flow = 650 L/h. Data were analyzed with the software MassLynxV4.1 for generation of calculated and comparison to observed mass ion packet.

Size exclusion chromatograph (SEC)

The unincubated and incubated Aβ40 samples were analyzed by SEC to quantify the amounts of monomers present in the samples after 72 hours of incubation. Before injecting the sample on the HPLC column, 60 μL of 50 μM Aβ40 was centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 rpm to remove insoluble aggregates. Supernatant (50 μL) was injected onto a BioSec-SEC-s2000 (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) column that was already equilibrated with 10 mM phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 at 0.5 mL/min on an Agilent 1100 series HPLC (Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA). Absorbance at 215 nm was monitored. Background signal was subtracted using the Agilent ChemStation software and percentages of soluble monomers were calculated relative to the protein present in the unincubated samples.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

Desalted protein solutions were diluted to 50 μM in 10 mM PB in the absence or presence of 10 μM MB or OPE12−. After irradiation, the peptide solution was loaded into a quartz cuvette with a path length of 1 mm (Starna cells Inc, Atascadero, CA) and analyzed on an AVIV 410 CD Spectrometer (AVIV, Lakewood, NJ) between 190 and 270 nm using an averaging time of 15 seconds. Three scans were recorded per sample and averaged signal was converted to molar ellipticity85.

TEM imaging

Aβ40 samples were diluted to 5 μM using MilliQ water. After the grids were glow discharged (Harrick Plasma Cleaner, Carson City, NV) for 30 seconds, each sample was loaded onto a grid and let adsorbed for 5 min. After wicking away excess sample, the grid was stained one time for 3 minutes and three times for 1-minute each using 2% uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Excess stain was wicked away in between the steps. The grid was then air dried for 30 minutes and imaged using a HITACHI HT7700 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi High Technologies Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with a beam current of 8.0 μA and an accelerating voltage of 80 keV.

Cell toxicity assay

Neuroblastoma SHSY-5Y cells were cultivated in DMEM media containing 1% PS and 10% FBS at 37°C and 5% CO2. When the cells reached 80% confluency, they were used to set up 96 well plates with 20,000 cells/100 μL well. After 16 hours of incubation, media was changed with serum deprived DMEM media and cells were further incubated for 24 hours to ensure cell synchronization. Cells were then treated with a sample containing appropriate protein and sensitizer concentrations and were incubated for another 24 or 48 hours after which cell viability was monitored by MTS assay. The assay involved adding 20 μL MTS reagent to each well already containing 100 μL media and incubating the plate for 3 hours before measuring the absorbance at 490 nm with a Spectra Max M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The background absorbance of MTS in media alone was subtracted from the absorbance obtained in the presence of cells. Absorbance obtained for untreated cells were also obtained and used as 100% viability.

All atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

The initial configurations for the Aβ fibril - OPE12− simulations were built with UCSF Chimera86. The fibril structure, 2LMN68 was obtained from the Protein Data Bank. In this work, we prepared an Aβ9–40 protofibril made of 24 peptides to evaluate OPE12− binding sites. 12 OPEs were positioned around the protofibril at a distance of 10 Å away from the protofibril surface. The anionic OPE12− was built using the GaussView 5 package and geometry optimizations was carried out with Gaussian 09.87 Simulations were prepared using the AMBERTools suite88. Parameters for simulating the protofibril structures were obtained from the AMBER14 force field. OPEs were parameterized using the AMBER generalized force field (GAFF) and partial charges were generated using the R.E.D. server89, 90. Each system was solvated in explicit water molecules using the TIP3P model and a total of 48 counter Na+ ions were added to neutralize the system. MD was performed using the AMBER MD package as previously described91. Coordinates for the single Aβ9–40 monomer hairpin were extracted from the protofibril PDB structure following energy minimization and equilibration of the monomer peptide. Production MD simulations were carried out for 100 ns. OPE12− binding sites on the protofibril surface were analyzed using UCSF Chimera to determine the proximity of bound OPEs to oxidizable residues on the protofibrils. Residues within 4 Å of bound OPEs (either single or complexed) were selected and counted. Distances of the oxidizable methionine residues to bound OPEs, which were larger than the 4 Å cutoff, were determined as the center-of-mass distances between methionine residues and bound OPEs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was performed, in part, at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science. Los Alamos National Laboratory, an affirmative action equal opportunity employer, is managed by Triad National Security, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy’s NNSA, under contract 89233218CNA000001. We are also thankful to Dr. Yanli Tang and Dr. Eunkyung Ji who originally synthesized OPE12−. The Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant ACI-1053575, was used for performing simulations.

Funding Sources

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Awards 1605225 and 1207362, and National Institute of Health (NIH) Award 1R21NS111267-01 to E.Y.C. and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency Grant HDTRA1-08-1-0053 to D.G.W. G.B. and J.H. were funded by the NSF Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) in Nano Science & Micro System Award #1560058. D.O. was supported by NIH PREP postbaccalaureate #5R25GM075149. We would also like to acknowledge generous gifts from the Huning family and others from the State of New Mexico.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AAA

amino acid analysis

- Aβ

amyloid β

- CD

circular dichroism

- CTAB

cetyltrimethylammonium bromide

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DNPH

2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine

- ESI-MS

electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GAFF

generalized force field

- HCl

hydrochloride acid

- RP-HPLC

reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography

- MB

methylene blue

- MD

molecular dynamics

- NaCl

sodium chloride

- OPE

oligo-p-phenylene ethynylene

- PDB

protein databank

- PDT

photodynamic therapy

- PS

penicillin-streptomycin

- TPBS

pH 7.4 phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information: Reverse phase HPLC of Aβ40 monomers before and after irradiation in the presence of MB and OPE12−; TEM images of Aβ40 after incubation of 50 μM monomers either alone (A) or in the presence of 2.6 μM non-sonicated Aβ40 fibrils (B) or 2.6 μM sonicated Aβ40 fibrils (C).

REFERENCES

- (1).Dolmans DE; Fukumura D; Jain RK Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3 (5), 380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).dos Santos A. l. F.; de Almeida DRQ; Terra LF; Baptista M. c. S.; Labriola L Photodynamic Therapy in Cancer Treatment-an Update Review. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Murphy MP; LeVine H 3rd. Alzheimer’s Disease and the Amyloid-Beta Peptide. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 19 (1), 311–323. DOI: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sadigh-Eteghad S; Sabermarouf B; Majdi A; Talebi M; Farhoudi M; Mahmoudi J Amyloid-Beta: A Crucial Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease. Med. Princ. Pract. 2015, 24 (1), 1–10. DOI: 10.1159/000369101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Koo EH; Lansbury PT; Kelly JW Amyloid Diseases: Abnormal Protein Aggregation in Neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96 (18), 9989–9990. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.9989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Soto C Unfolding the Role of Protein Misfolding in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4 (1), 49–60, 10.1038/nrn1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Soto C; Estrada LD Protein Misfolding and Neurodegeneration. Arch. Neurol. 2008, 65 (2), 184–189. DOI: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ross CA; Poirier MA Protein Aggregation and Neurodegenerative Disease. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S10. DOI: 10.1038/nm1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Walsh P; Vanderlee G; Yau J; Campeau J; Sim VL; Yip CM; Sharpe S The Mechanism of Membrane Disruption by Cytotoxic Amyloid Oligomers Formed by Prion Protein(106–126) Is Dependent on Bilayer Composition. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289 (15), 10419–10430. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M113.515866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Meredith SC Protein Denaturation and Aggregation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1066 (1), 181–221. DOI: 10.1196/annals.1363.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Glabe CG Common Mechanisms of Amyloid Oligomer Pathogenesis in Degenerative Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27 (4), 570–575. DOI: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Stokin GB; Lillo C; Falzone TL; Brusch RG; Rockenstein E; Mount SL; Raman R; Davies P; Masliah E; Williams DS; et al. Axonopathy and Transport Deficits Early in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Science 2005, 307 (5713), 1282–1288. DOI: 10.1126/science.1105681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Meyer-Luehmann M; Spires-Jones TL; Prada C; Garcia-Alloza M; de Calignon A; Rozkalne A; Koenigsknecht-Talboo J; Holtzman DM; Bacskai BJ; Hyman BT Rapid Appearance and Local Toxicity of Amyloid-Β Plaques in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2008, 451, 720. DOI: 10.1038/nature06616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).He Z; Guo JL; McBride JD; Narasimhan S; Kim H; Changolkar L; Zhang B; Gathagan RJ; Yue C; Dengler C; et al. Amyloid-Β Plaques Enhance Alzheimer’s Brain TauSeeded Pathologies by Facilitating Neuritic Plaque Tau Aggregation. Nat. Med. 2018, 24 (1), 29–38. DOI: 10.1038/nm.4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Cushman M; Johnson BS; King OD; Gitler AD; Shorter J Prion-Like Disorders: Blurring the Divide between Transmissibility and Infectivity. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123 (Pt 8), 1191–1201. DOI: 10.1242/jcs.051672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Guo JL; Lee VMY Cell-to-Cell Transmission of Pathogenic Proteins in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat. Med. 2014, 20 (2), 130–138. DOI: 10.1038/nm.3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kfoury N; Holmes BB; Jiang H; Holtzman DM; Diamond MI Trans-Cellular Propagation of Tau Aggregation by Fibrillar Species. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287 (23), 19440–19451. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Marr RA; Rockenstein E; Mukherjee A; Kindy MS; Hersh LB; Gage FH; Verma IM; Masliah E Neprilysin Gene Transfer Reduces Human Amyloid Pathology in Transgenic Mice. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23 (6), 1992–1996. DOI: 10.1523/jneurosci.23-06-01992.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Chesneau V; Vekrellis K; Rosner MR; Selkoe DJ Purified Recombinant Insulin-Degrading Enzyme Degrades Amyloid Beta-Protein but Does Not Promote Its Oligomerization. Biochem. J. 2000, 351 Pt 2 (Pt 2), 509–516.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Qiu WQ; Folstein MF Insulin, Insulin-Degrading Enzyme and Amyloid-Β Peptide in Alzheimer’s Disease: Review and Hypothesis. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27 (2), 190–198. DOI: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Carty NC; Nash K; Lee D; Mercer M; Gottschall PE; Meyers C; Muzyczka N; Gordon MN; Morgan D Adeno-Associated Viral (Aav) Serotype 5 Vector Mediated Gene Delivery of Endothelin-Converting Enzyme Reduces Abeta Deposits in App + Ps1 Transgenic Mice. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16 (9), 1580–1586. DOI: 10.1038/mt.2008.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Miners JS; Baig S; Palmer J; Palmer LE; Kehoe PG; Love S Symposium: Clearance of Aβ from the Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease: Aβ-Degrading Enzymes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Pathol. 2008, 18 (2), 240–252. DOI: doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Mo J-J; Li J.-y.; Yang Z; Liu Z; Feng J-S Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Amyloid-Β Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2017, 4 (12), 931–942. DOI: doi: 10.1002/acn3.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Spencer B; Masliah E Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s Disease: Past, Present and Future. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Pearson HA; Peers C Physiological Roles for Amyloid Beta Peptides. J. Physiol. 2006, 575 (Pt 1), 5–10. DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Brothers HM; Gosztyla ML; Robinson SR The Physiological Roles of Amyloid-Β Peptide Hint at New Ways to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 118–118. DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Dougherty TJ Photochemistry in the Treatment of Cancer. Adv. Photochem. 1992, 17, 275–311. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Triesscheijn M; Baas P; Schellens JH; Stewart FA Photodynamic Therapy in Oncology. Oncologist 2006, 11 (9), 1034–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kalka K; Merk H; Mukhtar H Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 42 (3), 389–413. DOI: 10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Yoon I; Li JZ; Shim YK Advance in Photosensitizers and Light Delivery for Photodynamic Therapy. Clin. Endosc. 2013, 46 (1), 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).DeRosa MC; Crutchley RJ Photosensitized Singlet Oxygen and Its Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 233–234, 351–371. DOI: 10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00034-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Taniguchi A; Sasaki D; Shiohara A; Iwatsubo T; Tomita T; Sohma Y; Kanai M Attenuation of the Aggregation and Neurotoxicity of Amyloid-Beta Peptides by Catalytic Photooxygenation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53 (5), 1382–1385. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201308001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lee JS; Lee BI; Park CB Photo-Induced Inhibition of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Aggregation In vitro by Rose Bengal. Biomaterials 2015, 38, 43–49. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Lee BI; Lee S; Suh YS; Lee JS; Kim A.-k.; Kwon O-Y; Yu K; Park CB Photoexcited Porphyrins as a Strong Suppressor of Β-Amyloid Aggregation and Synaptic Toxicity. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127 (39), 11634–11638. DOI: doi: 10.1002/ange.201504310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Liu Z; Ma M; Yu D; Ren J; Qu X Target-Driven Supramolecular Self-Assembly for Selective Amyloid-Β Photooxygenation against Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (40), 11003–11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Taniguchi A; Shimizu Y; Oisaki K; Sohma Y; Kanai M Switchable Photooxygenation Catalysts That Sense Higher-Order Amyloid Structures. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 974, Article. DOI: 10.1038/nchem.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Xu Y; Xiao L Efficient Suppression of Amyloid-Β Peptide Aggregation and Cytotoxicity with Photosensitive Polymer Nanodots. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8 (26), 5776–5782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Chung YJ; Lee CH; Lim J; Jang J; Kang H; Park CB Photomodulating Carbon Dots for Spatiotemporal Suppression of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Aggregation. ACS nano 2020, 14 (12), 16973–16983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Chung YJ; Kim K; Lee BI; Park CB Carbon Nanodot-Sensitized Modulation of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Self-Assembly, Disassembly, and Toxicity. Small 2017, 13 (34), 1700983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Son G; Lee BI; Chung YJ; Park CB Light-Triggered Dissociation of Self-Assembled Β-Amyloid Aggregates into Small, Nontoxic Fragments by Ruthenium (Ii) Complex. Acta Biomater. 2018, 67, 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kang J; Nam JS; Lee HJ; Nam G; Rhee H-W; Kwon T-H; Lim MH Chemical Strategies to Modify Amyloidogenic Peptides Using Iridium (Iii) Complexes: Coordination and Photo-Induced Oxidation. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10 (28), 6855–6862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Kim K; Lee SH; Choi DS; Park CB Photoactive Bismuth Vanadate Structure for Light-Triggered Dissociation of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Aggregates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28 (41), 1802813. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hasunuma N; Kawakami M; Hiramatsu H; Nakabayashi T Preparation and Photo-Induced Activities of Water-Soluble Amyloid Β-C 60 Complexes. RSC Adv. 2018, 8 (32), 17847–17853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Du Z; Gao N; Wang X; Ren J; Qu X Near-Infrared Switchable Fullerene-Based Synergy Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Small 2018, 14 (33), 1801852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Lee BI; Suh YS; Chung YJ; Yu K; Park CB Shedding Light on Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloidosis: Photosensitized Methylene Blue Inhibits Self-Assembly of Β-Amyloid Peptides and Disintegrates Their Aggregates. Sci Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 7523. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-07581-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Floyd RA Phototherapy Using Methylene Blue. U.S. Patent No. 4,950,665. 21 Aug. 1990.: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Tardivo JP; Del Giglio A; de Oliveira CS; Gabrielli DS; Junqueira HC; Tada DB; Severino D; de Fátima Turchiello R; Baptista MS Methylene Blue in Photodynamic Therapy: From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2005, 2 (3), 175–191. DOI: 10.1016/S1572-1000(05)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Nagashima N; Ozawa S; Furuta M; Oi M; Hori Y; Tomita T; Sohma Y; Kanai M Catalytic Photooxygenation Degrades Brain Aβ in Vivo. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7 (13), eabc9750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Ni J; Taniguchi A; Ozawa S; Hori Y; Kuninobu Y; Saito T; Saido TC; Tomita T; Sohma Y; Kanai M Near-Infrared Photoactivatable Oxygenation Catalysts of Amyloid Peptide. Chem 2018, 4 (4), 807–820. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Donabedian PL; Pham TK; Whitten DG; Chi EY Oligo(P-Phenylene Ethynylene) Electrolytes: A Novel Molecular Scaffold for Optical Tracking of Amyloids. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6 (9), 1526–1535. DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Donabedian PL; Evanoff M; Monge FA; Whitten DG; Chi EY Substituent, Charge, and Size Effects on the Fluorogenic Performance of Amyloid Ligands: A Small-Library Screening Study. ACS Omega 2017, 2 (7), 3192–3200. DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Fanni AM; Monge FA; Lin C-Y; Thapa A; Bhaskar K; Whitten DG; Chi EY High Selectivity and Sensitivity of Oligomeric P-Phenylene Ethynylenes for Detecting Fibrillar and Pre-Fibrillar Amyloid Protein Aggregates. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10 (3), 1813–1825. DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Whitten DG; Tang Y; Zhou Z; Yang J; Wang Y; Hill EH; Pappas HC; Donabedian PL; Chi EY A Retrospective: 10 Years of Oligo (Phenylene-Ethynylene) Electrolytes: Demystifying Nanomaterials. Langmuir 2018, 35 (2), 307–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Liu Y; Ogawa K; Schanze KS Conjugated Polyelectrolye as Fluorescent Sensors. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C: Photochem. Rev. 2009, 10, 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Tang Y; Hill EH; Zhou Z; Evans DG; Schanze KS; Whitten DG Synthesis, Self-Assembly, and Photophysical Properties of Cationic Oligo(P-Phenyleneethynylene)S. Langmuir 2011, 27 (8), 4945–4955. DOI: 10.1021/la1050173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Hill EH; Evans DG; Whitten DG The Influence of Structured Interfacial Water on the Photoluminescence of Carboxyester-Terminated Oligo-P-Phenylene Ethynylenes. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2014, 27 (4), 252–257. DOI: 10.1002/poc.3258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Donabedian PL; Creyer MN; Monge FA; Schanze KS; Chi EY; Whitten DG Detergent-Induced Self-Assembly and Controllable Photosensitizer Activity of Diester Phenylene Ethynylenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114 (28), 7278–7282. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1702513114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Yu D; Guan Y; Bai F; Du Z; Gao N; Ren J; Qu X Metal–Organic Frameworks Harness Cu Chelating and Photooxidation against Amyloid Β Aggregation in Vivo. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25 (14), 3489–3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Zhang H; Hao C; Qu A; Sun M; Xu L; Xu C; Kuang H Light-Induced Chiral Iron Copper Selenide Nanoparticles Prevent Β-Amyloidopathy in Vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (18), 7131–7138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Turner JP; Lutz-Rechtin T; Moore KA; Rogers L; Bhave O; Moss MA; Servoss SL Rationally Designed Peptoids Modulate Aggregation of Amyloid-Beta 40. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5 (7), 552–558. DOI: 10.1021/cn400221u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Pattison DI; Rahmanto AS; Davies MJ Photo-Oxidation of Proteins. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 2012, 11 (1), 38–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Hunt S Degradation of Amino Acids Accompanying in Vitro Protein Hydrolysis. In Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Amino Acids, Barrett GC Ed.; Springer Netherlands, 1985; pp 376–398. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Silva E Sensitized Photo-Oxidation of Amino Acids in Proteins: Some Important Biological Implications. Biol. Res. 1996, 29, 57–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Weil L; Seibles TS; Herskovits TT Photooxidation of Bovine Insulin Sensitized by Methylene Blue. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1965, 111 (2), 308–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Moan J; Berg K The Photodegradation of Porphyrins in Cells Can Be Used to Estimate the Lifetime of Singlet Oxygen. Photochem. Photobiol. 1991, 53 (4), 549–553. DOI: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1991.tb03669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Skovsen E; Snyder JW; Lambert JD; Ogilby PR Lifetime and Diffusion of Singlet Oxygen in a Cell. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005, 109 (18), 8570–8573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Michaeli A; Feitelson J Reactivity of Singlet Oxygen toward Amino Acids and Peptides. Photochem. Photobiol. 1994, 59 (3), 284–289. DOI: doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Paravastu AK; Leapman RD; Yau W-M; Tycko R Molecular Structural Basis for Polymorphism in Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105 (47), 18349–18354. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0806270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Martin TD; Brinkley G; Whitten DG; Chi EY; Evans DG Computational Investigation of the Binding Dynamics of Oligo P-Phenylene Ethynylene Fluorescence Sensors and Aβ Oligomers. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11 (22), 3761–3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Cohen SIA; Linse S; Luheshi LM; Hellstrand E; White DA; Rajah L; Otzen DE; Vendruscolo M; Dobson CM; Knowles TPJ Proliferation of Amyloid-Β42 Aggregates Occurs through a Secondary Nucleation Mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110 (24), 9758–9763. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1218402110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Esler WP; Stimson ER; Jennings JM; Vinters HV; Ghilardi JR; Lee JP; Mantyh PW; Maggio JE Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid Propagation by a Template-Dependent Dock-Lock Mechanism. Biochemistry 2000, 39 (21), 6288–6295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Cannon MJ; Williams AD; Wetzel R; Myszka DG Kinetic Analysis of Beta-Amyloid Fibril Elongation. Anal. Biochem. 2004, 328 (1), 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Standardization, I. O. f. Iso 10993–5: Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices. Part 5: Tests for in Vitro Cytotoxicity. ISO Geneva, Switzerland: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Ahn M; Lee BI; Chia S; Habchi J; Kumita JR; Vendruscolo M; Dobson CM; Park CB Chemical and Mechanistic Analysis of Photodynamic Inhibition of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Aggregation. ChemComm 2019, 55 (8), 1152–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Spiller W; Kliesch H; Wöhrle D; Hackbarth S; Röder B; Schnurpfeil G Singlet Oxygen Quantum Yields of Different Photosensitizers in Polar Solvents and Micellar Solutions. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 1998, 2 (2), 145–158. DOI: doi:. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Matheson IBC; Lee J Chemical Reaction Rates of Amino Acids with Singlet Oxygen. Photochem. Photobiol. 1979, 29 (5), 879–881. DOI: doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1979.tb07786.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Smith JF; Knowles TPJ; Dobson CM; Macphee CE; Welland ME Characterization of the Nanoscale Properties of Individual Amyloid Fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103 (43), 15806–15811. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0604035103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Ozawa D; Yagi H; Ban T; Kameda A; Kawakami T; Naiki H; Goto Y Destruction of Amyloid Fibrils of a Β2-Microglobulin Fragment by Laser Beam Irradiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284 (2), 1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Lasagna-Reeves CA; Glabe CG; Kayed R Amyloid-Β Annular Protofibrils Evade Fibrillar Fate in Alzheimer Disease Brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286 (25), 22122–22130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]