Abstract

The spatiotemporal configuration of genes with distal regulatory elements, and the impact of chromatin mobility on transcription, remain unclear. Loop extrusion is an attractive model for bringing genetic elements together, but how this functionally interacts with transcription is also largely unknown. We combine live tracking of genomic loci and nascent transcripts with molecular dynamics simulations to assess the spatiotemporal arrangement of the Sox2 gene and its enhancer, in response to a battery of perturbations. We find a close link between chromatin mobility and transcriptional status: active elements display more constrained mobility, consistent with confinement within specialized nuclear sites, and alterations in enhancer mobility distinguish poised from transcribing alleles. Strikingly, we find that whereas loop extrusion and transcription factor-mediated clustering contribute to promoter-enhancer proximity, they have antagonistic effects on chromatin dynamics. This provides an experimental framework for the underappreciated role of chromatin dynamics in genome regulation.

Keywords: Chromatin dynamics, enhancer, transcription, anomalous diffusion, molecular dynamics, live imaging

INTRODUCTION

Metazoan gene expression is finely controlled by regulatory inputs from promoter sequences and distal regulatory elements, such as enhancers. How these dispersed elements are spatiotemporally coordinated to determine transcriptional output has been a topic of intense study, but key questions remain unresolved1,2. For example, most chromosome conformation capture-based experiments support a model where distal enhancers require close spatial proximity to target genes to confer activation3–5, often presumed via chromatin “looping”, and engineered promoter-enhancer contacts have been shown to stimulate expression6. However, recent imaging experiments at different loci have shown clear physical separation of enhancers and active genes (often in the order of ~ 200–300 nm), with conflicting results as to whether their separation decreases7,8, stays the same9 or may actually increase10 on transcriptional activation. The identification of nuclear clusters of lineage-specific transcription factors11,12, RNA polymerase II (PolII)13,14, and genes and regulatory elements themselves15–19 has led to the proposal that transcription is organized into specialized nuclear microenvironments or “hubs”20. In this model, high local concentrations of regulatory factors accumulate near genomic sequences that are loosely co-associated; the shared location of regulatory elements within this microenvironment is more important for transcriptional regulation than their direct physical juxtaposition. These hubs are potentially built up through specific protein-protein interactions and/or phase-separated condensate formation between intrinsically disordered domains found on many transcription factors12,21. How genes and distal regulatory elements locate or nucleate such hubs, and how the different regulatory inputs are coordinated into a transcriptional decision within, remain open questions.

An often-overlooked aspect determining how regulatory chromatin architectures are built or maintained is the underlying mobility (and freedom of movement) of the component factors. Whereas non-histone chromatin proteins, including transcription factors, are highly mobile in the nucleoplasm22, the large polymeric chromatin fiber has more constrained movement, due to a crowded environment and elastic interactions with neighboring segments of the polymer23. This is often characterized as sub-diffusive movement, whereby the mean squared displacement (MSD) of the genomic element follows the relationship with time, where is the diffusion coefficient (a proxy for diffusive speed) and , the anomalous exponent, is smaller than the value of 1 found in classical Brownian diffusion. Initial studies of randomly inserted tags suggested that heterochromatin was inherently less mobile than euchromatin in yeast24, but we recently reported significant locus-specific differences in chromatin diffusive properties at euchromatic regions in mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs), suggesting finer-scale modulation of chromatin dynamics, potentially linked to underlying function25. As methods for tracking specific genomic regions in vivo has recently become available, researchers have asked whether the transcriptional activity of genes affects their mobility. We previously showed that an estrogen-inducible transgene could only explore a much smaller nuclear volume on acute induction, and that this constraint was dependent on transcriptional initiation26, consistent with a model whereby the activated gene becomes confined within a transcriptional hub. This is supported by analogous studies showing slowed movement of the pluripotency gene Nanog when transcriptionally active27 and global enhanced chromatin mobility on treatment with transcriptional inhibitors28,29. However, mobility of the Oct4 gene was found to be insensitive to transcriptional status27, and a different study of transition between ESCs and epiblast-like cells reported acceleration of both promoters and enhancer-proximal sequences specific to the cell state where the elements are active30. A clear understanding of how transcriptional events modulate chromatin dynamics (or vice versa) is thus still lacking.

At a larger scale, promoter-enhancer communication takes place within the context of topologically associated domains (TADs), regions of enhanced intra-domain chromatin contacts identified in population-average Hi-C maps31,32, which have been proposed to prevent inappropriate promoter-enhancer communication across TAD borders, and/or to reduce the effective search space for enhancers to co-associate with target genes1,33–35. The major mechanism believed to organize TAD architecture is loop extrusion by SMC protein complexes, particularly cohesin (reviewed in ref. 36, and references therein). Cohesin loads on chromatin, extrudes loops of the chromatin fiber (mostly bidirectionally), and is dissociated by the factor WAPL to generate metastable chromatin loops in an equilibrium. Sites where loop extrusion are stalled, particularly the juxtaposition of convergently facing sites for the factor CTCF (CCCTC-binding factor), whose N-terminus specifically interacts with the cohesin complex37, form the bases of more stabilized loops at TAD borders. These are observed in Hi-C maps38, although recent live imaging experiments have revealed these to also be relatively rare and transient interactions in individual cells39,40. The so-called “architectural interactions” brought about by convergent CTCF sites have been proposed to facilitate juxtaposition of adjacent promoters and enhancers41, and loop extrusion has also been shown to be required for efficient activity of more distal, as opposed to proximal, enhancers42,43. Further, recent simulations and experimental results show that cohesin-mediated loop extrusion generally reduces chromatin mobility28,40, perhaps further “stabilizing” such genomic configurations. However, we and others have observed extensive persistence of promoter-enhancer interactions when CTCF and/or cohesin is ablated44–46. This latter finding is reminiscent of the apparent competition that exists between TADs and chromosome compartmentation (higher-order co-associations between domains of homotypic chromatin, such as active with active): cohesin ablation eliminates TADs, but appears to strengthen compartments47,48. The exact mechanisms promoting chromosome compartmentation genome-wide are unclear, but since co-association of active domains appears to depend on transcription itself49 and transcription co-factors like BRD250, it is reasonable to hypothesize that these could be the same biochemical principles involved in clustering transcription factors and active elements at proposed transcriptional hubs, raising the curious possibility that loop extrusion may sometimes antagonize such nuclear microenvironments.

To assess more closely the interplay of enhancer activity, transcription and cohesin-mediated loop extrusion on the spatiotemporal organization of gene regulation, we tagged the promoter and major enhancer (SCR; Sox2 control region) of the pluripotency gene Sox2 in mouse ESCs, in combination with detection of nascent transcription from the same allele, for their tracking at high temporal resolution. With a battery of genetic and other experimental perturbations, we confirmed the decoupling of transcription and promoter-enhancer proximity that was previously described at this locus9,44,46, and also found a hitherto unappreciated localized effect of transcription on chromatin dynamics. Promoter kinetics are disrupted on severe transcriptional inhibition, but when comparing transcriptionally bursting and “poised” Sox2 alleles, it is the enhancer which specifically becomes less mobile on gene firing. Most strikingly, we observed that deleting either CTCF or transcription factor binding sites induced opposing effects on localized chromatin mobility. In addition, molecular dynamics simulations were able to recapitulate these experimental findings only when competition between loop extrusion and transcription-linked enhancer-promoter communication was reinforced, suggesting they may be antagonistic processes on chromatin dynamics, even though from a population-average viewpoint they are assumed to mediate the same interaction. These findings unify some of the seemingly conflicting results from previous studies and highlight the pitfalls of relying solely on population-averaged experiments on fixed cells to draw conclusions about a dynamic process such as spatiotemporal gene regulation.

RESULTS

Enhancer-promoter proximity is frequently maintained at the Sox2 locus independent of transcription

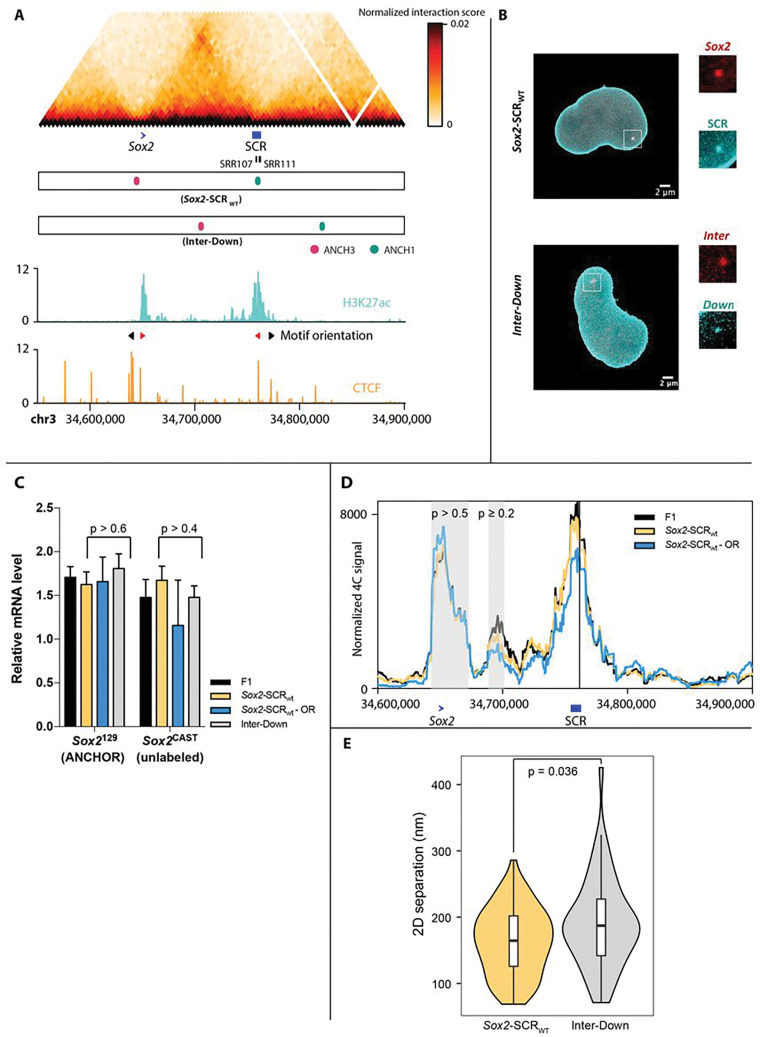

To follow promoter-enhancer communication in living cells, we tagged the Sox2 promoter and SCR with orthologous parS sites (ANCHOR1 and ANCHOR3; separated by ~ 115 kb) in the musculus allele of F1 (Mus musculus129 × Mus castaneus) hybrid ESCs (we term this line Sox2-SCRWT), enabling their visualization on transfection with plasmids encoding fluorescently labeled ParB proteins26,51. The small size (~ 1 kb) of the parS sequences allowed us to place the tags very close to the promoter (5.5 kb upstream of the TSS) and actually inside the SCR, in between the elements known to control Sox2 transcription44, facilitating direct imaging of the promoter and enhancer themselves. As a control, we also generated an ESC line (Inter-Down) with parS integration sites shifted by ~ 60 kb, allowing visualization of non-regulatory loci with equivalent genomic separation (Fig. 1a,b). Allele-specific qRT-PCR showed that neither integration of the parS sites, nor their binding by transfected ParB proteins, affected Sox2 expression in cis (Fig. 1c). Cell cycle progression and expression of other pluripotency markers was similarly unaffected by the parS/ParB system (Fig S1a,b). Further, allele-specific 4C-seq showed that Sox2-SCR interaction strength was also unaltered by parS integration and ParB binding (Fig. 1d), strongly suggesting that the imaging setup has negligible functional impact on the loci that are visualized in this study.

Figure 1. parS/ParB labeling of specific sites at the Sox2 locus.

a) Overview of the Sox2 locus used in this study, showing (top to bottom): Hi-C map in ESCs (data from ref 61), showing the TAD delimited by the Sox2 gene and SCR (positions shown in blue, and the locations of specific SCR regulatory elements SRR107 and SRR111 shown in black, below the map); scaled positions of ANCH1 and ANCH3 labels inserted in the Sox2-SCRWT and Inter-Down ESC lines; ESC ChIP-seq profiles for the active histone mark, acetylation of histone H3 lysine-27 (H3K27ac; cyan) and CTCF (orange) at the same locus (data from ref 89). Orientations of the motifs of the major CTCF sites are denoted by arrows above the CTCF ChIP-seq profile; the red arrows denote the positions of CTCF sites that are perturbed in this study. b) Representative images of Sox2-SCRWT (top) and Inter-Down (bottom) nuclei (after segmentation and removal of cytoplasmic signal), with the OR3-IRFP signal shown in red and the OR1-EGFP signal shown in cyan; scale bar 2 μm. Insets show zoomed regions around spots corresponding to bound parS sequences. c) Allele-specific qRT-PCR quantification, normalized to SDHA, of Sox2 expression in F1, Sox2-SCRWT before and after transfection with ParB vectors (OR), and Inter-Down ESCs (n >= 3). Error bars indicate standard deviations from the mean. For both alleles, expression is not significantly different to that measured in F1 cells (minimum p-values from two-tailed t-tests are given). d) Musculus-specific 4C-seq profiles (mean of two replicates) using the SCR as bait are shown for F1 and Sox2-SCRWT ESCs, before and after transfection with ParB vectors (OR). The two regions consistently called as interactions are denoted in gray, and the minimum p-values for compared interaction scores with F1 (two-tailed t-test) are denoted. e) Violin plot showing the distributions of median inter-probe distances for Sox2-SCRWT and Inter-Down ESCs. Sox2 and SCR are significantly closer on average than control sequences (p = 0.036; Wilcoxon rank sum test).

For these two ESC lines, we imaged the labeled loci at high temporal resolution (500 ms per frame) in 2D with spinning disk confocal microscopy, using a set of optimized affine transformations to correct for chromatic aberrations and control for camera misalignment25. Further enhancement of spot centroid localization was performed by fitting a Gaussian shape. In line with previous high-throughput DNA FISH studies52,53, median inter-probe distances demonstrated a large cell-to-cell heterogeneity, varying from 69–286 nm (median 164 nm; interquartile range 76 nm; ) for Sox2-SCR distances and from 71–426 nm (median 187 nm; interquartile range 85 nm; ) for the control regions (Fig. 1e; Table S1). Over the short periods over which images were acquired, separation distances were relatively stable (median absolute deviation 30–107 nm; inter-decile range 74–293 nm). As may be expected from ESC Hi-C maps, the median distance between Sox2 and the SCR is significantly smaller than the control regions of equivalent genomic separation (; Wilcoxon rank sum test). The Sox2-SCR separation distances we measured agree very well with the 2D distances measured in the wild-type Sox2 locus in recent multiplexed DNA FISH studies53 (median 160 nm; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig S2a). Although this implies that the parS/ParB system does not perturb endogenous chromosomal locus configurations within the nucleus, the ANCHOR1-tagged control region downstream of the SCR was not included in the multiplexed DNA FISH design. We therefore performed 3D DNA FISH in wild-type F1 and ANCHOR-labeled Sox2-SCRWT ESCs, using fosmid probes covering the locations of each of the parS integration sites, further confirming that average Sox2-SCR separation distances are smaller than the control regions (; Wilcoxon rank sum test), and that ANCHOR labeling has negligible effects on underlying chromatin organization (; Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig S2b,c). We note that a previous study using Tet- and Cu-repeat operators to label regions a little further upstream of the Sox2 promoter and downstream of the SCR measured significantly larger distances (median 221 nm; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test) than obtained with either ANCHOR or DNA FISH in untagged loci9 (Fig S2a). This suggests that, at least for this locus, the repetitive operator system may artificially inflate physical separation of tagged loci compared to untagged counterparts.

We previously identified by 4C-seq a near-complete loss of Sox2-SCR interaction in the early stages of ESC differentiation to neuronal precursors when Sox2 expression is shut down54. We recapitulated this finding when differentiating the labeled Sox2-SCRWT cells, observing a significant increase in average Sox2-SCR distance (median 200 nm; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test) by the third day, in agreement with the timing of loss of interaction observed by allele-specific 4C (Fig. 2a,b). This cannot be solely explained by general chromatin compaction changes accompanying loss of pluripotency, because the average distances between the control regions were not significantly increased (Fig. 2c; median 208 nm; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test). It has been proposed that promoter-enhancer “interactions” are somehow causal in transcriptional activation3,6, and the onset of increased promoter-enhancer separation corresponds to near-complete transcriptional shutdown of Sox2 (Fig S1c). However, recent studies, including those at the murine Sox2 locus, have brought this into question9,10,44. To directly test the effect of transcription on promoter-enhancer proximity, we also measured Sox2-SCR distances upon either global inhibition of transcription by treatment of the Sox2-SCRWT cells with the drug triptolide (which globally shuts down transcription by inhibiting TFIIH and inducing PolII degradation55), or specific inhibition of Sox2 expression in cis by the allele-specific deletion of two critical elements of the SCR (SRR107 and SRR111)44 to create the line Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111. In both cases, despite efficient loss of total or musculus-specific Sox2 expression, respectively, observed with qRT-PCR and single-molecule RNA FISH (Fig S1d-f), average Sox2-SCR (and control region) distances remained small and were non-significantly altered (median distances 142–172 nm; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test; Fig. 2d; Fig S2d). In none of the conditions tested did we find evidence for a multimodal distribution of inter-probe distances (; Hartigan’s dip test), which would occur if transcribing alleles were expected to have significantly different promoter-enhancer proximities than non-transcribing alleles.

Figure 2. Sox2-SCR distance is frequently uncoupled from transcriptional status.

a) Violin plot showing the distributions of median Sox2-SCR distances in Sox2-SCRWT ESCs after 0, 2 and 3 days of differentiation. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with p-values given. Below is shown a representative image of a Sox2-SCRWT nucleus after 3 days of differentiation, with the OR3-IRFP signal shown in red and the OR1-EGFP signal shown in cyan; scale bar 2 μm. Insets show zoomed regions around spots corresponding to bound parS sequences. b) Musculus-specific 4C-seq profile, using the SCR as bait, for Sox2-SCRWT ESCs at 0, 1, 2 and 3 days after differentiation. A dramatic loss of Sox2-SCR interaction (denoted by gray region) is observed on the third day. c) Violin plot showing the distributions of median inter-probe distances for Inter-Down ESCs after 0, 2 and 3 days of differentiation. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with p-values given. d) Violin plot showing the distributions of median inter-probe distances for Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111 ESCs, and Sox2-SCRWT cells after no treatment (−), or treatment with DMSO or triptolide. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with p-values given. To the right is shown a representative image of a Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111 nucleus, with the OR3-IRFP signal shown in red and the OR1-EGFP signal shown in cyan; scale bar 2 μm. Insets show zoomed regions around spots corresponding to bound parS sequences.

Overall, we thus find that the Sox2 promoter and SCR are frequently in relatively close proximity, and significantly closer than control regions of equivalent genomic separation, even when measured in 2D with diffraction-limited microscopy. However, whereas early stages of neuronal differentiation can increase average physical separation between promoter and enhancer, their distances remain relatively small. Moreover, the promoter and enhancer remain proximal on orthogonal perturbations disrupting Sox2 transcription to the same extent, such as deletion of key SCR elements or pharmacological inhibition of transcriptional initiation. Without super-resolution imaging, we cannot exclude small but functionally significant differences in enhancer-promoter proximity between different cell states, but the overall lack of large changes is consistent with initial conclusions from ours and others’ 4C studies that transcription and chromosome architecture are decoupled at the Sox2 locus44,46.

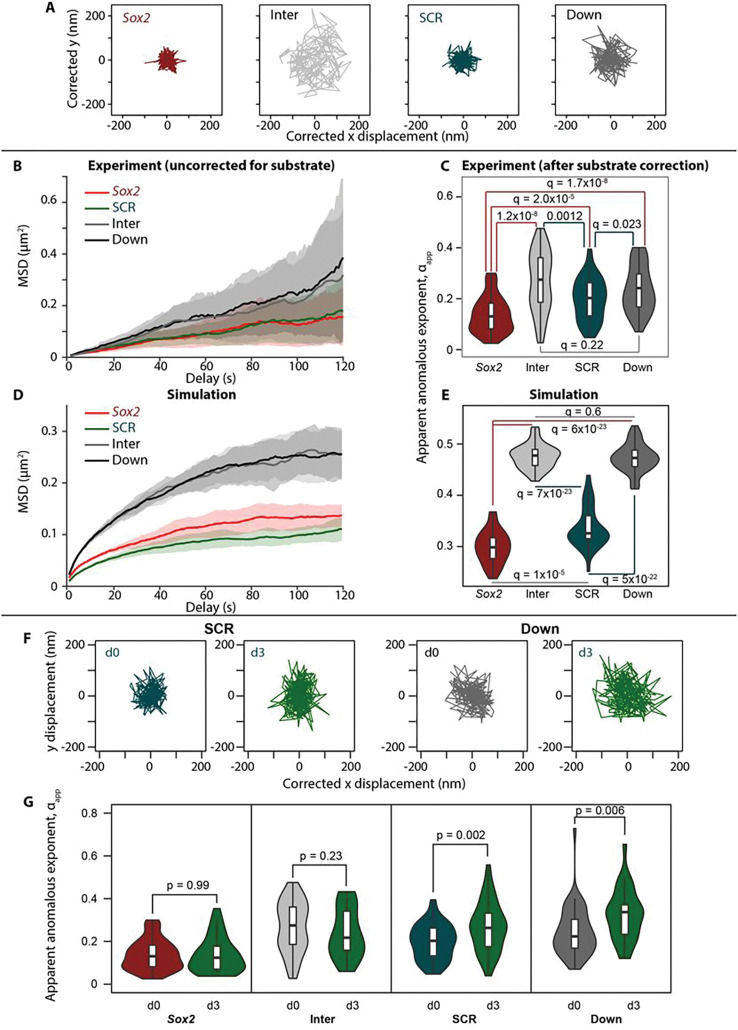

Promoters and enhancers have more constrained chromatin motion than control sequences

We previously reported that seemingly neutral elements within the HoxA locus exhibit different and locus-specific diffusive properties of labeled chromatin25. We therefore questioned whether chromatin mobilities are further different in promoters and enhancers, and whether these properties are linked to transcriptional output. Indeed, on examination of the tracks of labeled regions around the Sox2 locus, as well as their ensemble MSD curves, it was apparent that the promoter and enhancer were more limited to explore the nuclear volume than the control regions (Fig. 3a,b). Note that we have previously demonstrated that chromatin diffusive properties measured in 2D or 3D yield equivalent conclusions56. To assess the local chromatin mobilities more quantitatively, we applied our previously developed GPTool to fit the track trajectories to a fractional Brownian motion (FBM) model and extract their apparent diffusion coefficients, , and anomalous exponents, 25. As previously, we confirmed that the trajectories approximated to self-similar Gaussian-distributed displacements and an FBM velocity autocorrelation function over the time scale in which measurements are taken (Figs S3 and S4), affirming the suitability of the model used. The experimental MSD profiles were non-linear when plotted on double-logarithmic scales, suggesting that their properties cannot be explained by one regime, likely due in the main part to the confounding effects of nuclear and cellular movement and rotation. When analyzing cross-correlations of co-measured trajectories to estimate global movements of the cell/nuclear substrate25, the experimental MSD curves fit very well as the sum of the component locus and substrate FBM regimes (see Methods; Fig S5a). We stress that GPTool, apart from assuming proximity to a global FBM regime, is actually agnostic to any specific polymer model, and obtains estimates of diffusive parameters for individual trajectories which can vary quite a lot from the average (Fig. 3c). As such, the obtained values of the apparent anomalous exponent, , give a measure of constraint to the particle movement, which can be fairly compared across experiments. In line with our initial observations, the average substrate-corrected apparent anomalous exponent was significantly smaller for the active elements, the Sox2 promoter (median ) and the SCR (median ), than for the control regions (median and 0.224 for intervening and downstream regions, respectively), indicating a greater constraint to their local movements (Fig. 3c; full data given in Table S1). We note that these measured values correspond well with the α ~ 0.2 determined from fits to radial MSD curves for lac/TetO-tagged CTCF-mediated interacting sites with a similar genomic separation of ~ 150 kb40. Analogous radial MSD analysis for the Sox2-SCRWT and Inter-Down trajectories revealed similarly constrained motion, with the promoter and enhancer significantly more constrained than the neutral sequences (; ANCOVA test; Fig S5b). However, the nature of this analysis, by comparing the motion of one locus relative to the “fixed” second locus, does not allow any mobility differences between the two loci to be discerned. Using substrate-corrected GP-FBM, we further found that the promoter exhibited significantly more constrained motion than the enhancer (; Wilcoxon rank sum test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction), and all four labeled regions around the Sox2 locus exhibited more constrained motion than was observed around the generally inactive HoxA locus in ESCs25 (Fig S5c).

Figure 3. The Sox2 promoter and SCR are more constrained than control sequences.

a) Sample tracks of the 2D trajectories for labeled Sox2 (red), SCR (green), Inter (light gray) and Down (dark gray) sequences, plotted on the same scale. Displacements have been corrected for substrate displacement, and the plots have been centered on the median positions. b) Uncorrected ensemble MSD curves for the same four regions as in a, with lines showing median values and shading indicating the median absolute deviation. Inter and Down elements clearly move greater distances within the same timeframe as the Sox2 promoter and SCR. c) Violin plot showing the distributions of apparent anomalous exponents measured from the individual movies for each of the four regions as in a. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction, with q-values given. Apparent anomalous exponents are significantly lower for Sox2 and SCR than for the control regions, demonstrating their overall greater constraint. d) Ensemble MSD curves for the same four regions in a, derived from molecular dynamics simulations of the Sox2 locus, with lines showing median values and shading indicating the median absolute deviation. Sox2and SCR show apparent reduced mobility compared to control regions. e) Violin plot showing the distributions of apparent anomalous exponents derived from the same simulated trajectories as d. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction, with q-values given. f) Sample tracks of the 2D trajectories for labeled SCR and Down regions, at either 0 or 3 days of differentiation, plotted on the same scale. Displacements have been corrected for substrate displacement, and the plots have been centered on the median positions, showing an apparent increased freedom of movement for both regions on differentiation. g) Violin plots showing the distributions of apparent anomalous exponents measured from the individual movies for each of the four regions as in a, comparing 0 and 3 days of differentiation. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with p-values given; the apparent constraint of Sox2 and Inter is unchanged on differentiation.

These results are in line with our previous observations in a transgenic system that genes explore a more restricted nuclear volume when they are induced26. To explore these properties further, we modeled the 800 kb of ESC chromatin around the Sox2 locus as a self-avoiding polymer chain of 1 kb beads, classed as either “neutral”, binding PolII (Sox2 promoter and enhancers, determined by peaks of the active histone mark, acetylation of lysine-27 of histone H3 (H3K27ac)), transcribed genic regions (Sox2 gene body), or binding CTCF (determined by ChIP-seq peaks and with motif orientation information included). As we previously did for a theoretical locus to explain chromatin conformation changes on acute loss of PolII57, we performed molecular dynamics simulations using Langevin equations to model thermal motion of the chromatin and its binding factors, with the following additions to account for biological processes: PolII molecules have affinity for promoters and enhancers, and traverse the gene body to simulate transcription; PolII molecules also have affinity to each other to simulate potential for condensate or hub formation; cohesin complexes can bind anywhere on the polymer and extrude loops, but has preference to load at promoters and enhancers, and is unable to process past a CTCF-bound site when the motif is oriented towards the extruding loop (see Methods). The ensemble of chromatin conformations resulting from these simulations generated a contact map closely resembling that of the experimental Hi-C results, including the expected “interaction” between Sox2 and SCR (Fig S5d). Collecting the trajectories of the beads corresponding to the parS-tagged loci, we derived simulation MSD curves indicating a clear reduced mobility of Sox2 and SCR compared to control sequences (Fig. 3d). In accordance, application of GPTool to the simulated trajectories gave significantly smaller measurements at the promoter and enhancer than control regions (; Wilcoxon rank sum test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction) (Fig. 3e). This relatively simplified depiction of the locus thus supports the experimental results, suggesting that promoter-enhancer “affinity” brought about by transcriptional regulation and/or loop extrusion stalling processes is sufficient to explain their reduced chromatin dynamics.

Transcriptional perturbation specifically reduces Sox2 promoter mobility

We next measured the chromatin dynamics of the labeled loci on different means of transcriptional perturbation, reasoning that mobility constraints at the promoter and/or enhancer may be specifically relaxed. However, the distribution of apparent anomalous exponents of the Sox2 promoter did not change when the gene was silenced by either onset of differentiation or deletion of SRR107/SRR111 (Fig. 3f,g, 6b), and of both the enhancer and promoter was only weakly and non-significantly increased on treatment with triptolide (; Wilcoxon rank sum test; Fig S5e). On the other hand, the SCR became significantly less constrained at the onset of ESC differentiation (median ; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test), but so did the downstream control region (median ; ), raising questions as to whether this change is directly linked to transcriptional changes (Fig. 3f,g). Previous imaging studies, including our own, suggest that the dynamics of other gene loci are altered on their induction26,27,30, prompting us to look closer at the Sox2 locus trajectories. Indeed, inspection of the substrate movement-corrected ensemble MSD curves revealed that promoter mobility is generally reduced when transcription is blocked by either triptolide treatment or deletion of SRR107/SRR111 (Fig. 4a,b). The other parameter commonly used to quantify diffusive motion is the diffusion coefficient, , but since this is expressed in units of μm2/sα (i.e. scaling according to ), its measurement can only be fairly compared between sets of trajectories containing exactly the same anomalous exponent. To quantify Sox2 promoter dynamics while accounting for the clear variability in measured between individual trajectories within a population (Fig. 3c), we used the and values measured for each trajectory and computed r, the expected radius that the locus can explore in a given time interval, after accounting for substrate movement (see Methods). For all timescales appropriate for our imaging conditions (0.5–60 s), the Sox2 promoter explored significantly less area when transcription was perturbed than during control conditions (; Wilcoxon rank sum test with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction; Fig. 4c). It was previously proposed that “ongoing transcription may provide a source of nonthermal molecular agitation that can “stir” the chromatin within the local chromosomal domain”30. Our results partially support this hypothesis, although triptolide treatment had negligible effects on SCR dynamics (Fig. 4d), despite this enhancer producing transcripts in ESCs58. Further, general chromatin mobility, as measured in tagged histones, was found to actually be increased on pharmacological inhibition of transcription28. Taken together, our results suggest a clear but complex contribution of gene activity to chromatin dynamics. On the one hand, active elements are significantly more constrained than “neutral” genomic sequences, but transcriptional inhibition does not appear to “rescue” chromatin mobility at the former sequences. Conversely, we find evidence that a highly constrained promoter becomes even less mobile at extreme perturbation of target gene expression.

Figure 6. Loop extrusion and enhancer activity have opposing effects on chromatin dynamics.

a) Overview of the Sox2 locus, showing positions of the gene and SCR, and showing the regions deleted in the Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111, Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_Sox2 and Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_SCR (shown in cyan, red and blue, respectively). Below are shown ESC ChIP-seq profiles for H3K27ac (cyan) and CTCF (orange). b) Violin plot showing distributions of apparent anomalous exponents measured from the individual movies for the Sox2 promoter, comparing Sox2-SCRWT, Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111, Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_Sox2 and Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_SCR ESCs. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with p-values given. c) Sample tracks of the 2D trajectories for Sox2 in Sox2-SCRWT and Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_Sox2 cells, plotted on the same scale. Displacements have been corrected for substrate displacement, and the plots have been centered on the median positions. d) Violin plot showing distributions of apparent anomalous exponents measured from the individual movies for the SCR, comparing Sox2-SCRWT, Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111, Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_Sox2 and Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_SCR ESCs. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with p-values given. e) Sample tracks of the 2D trajectories for the SCR in Sox2-SCRWT, Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111 and SCRΔCTCF_SCR cells, plotted on the same scale. Displacements have been corrected for substrate displacement, and the plots have been centered on the median positions.

Figure 4. Severe transcriptional inhibition specifically reduces Sox2 promoter mobility.

a,b) Ensemble MSD curves, corrected for substrate movement and plotted on a double-log scale, comparing Sox2 promoter dynamics between a) Sox2-SCRWT and Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111 ESCs, and b) Sox2-SCRWT cells treated with either DMSO or triptolide. Lines indicate median values and shading the median absolute deviations. MSD reduction as shown by downwards vertical shift of profile on transcriptional inhibition demonstrates a reduced mobility of the labeled promoter. c,d) Violin plots showing distributions of apparent explored radii after 1 s (left) or 60 s (right), computed from individual movies for c) Sox2 and d) SCR, comparing Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111 ESCs, and Sox2-SCRWT cells after no treatment (−), or treatment with DMSO or triptolide. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction, with q-values given. Sox2, but not SCR, explored radii are consistently reduced on transcriptional inhibition.

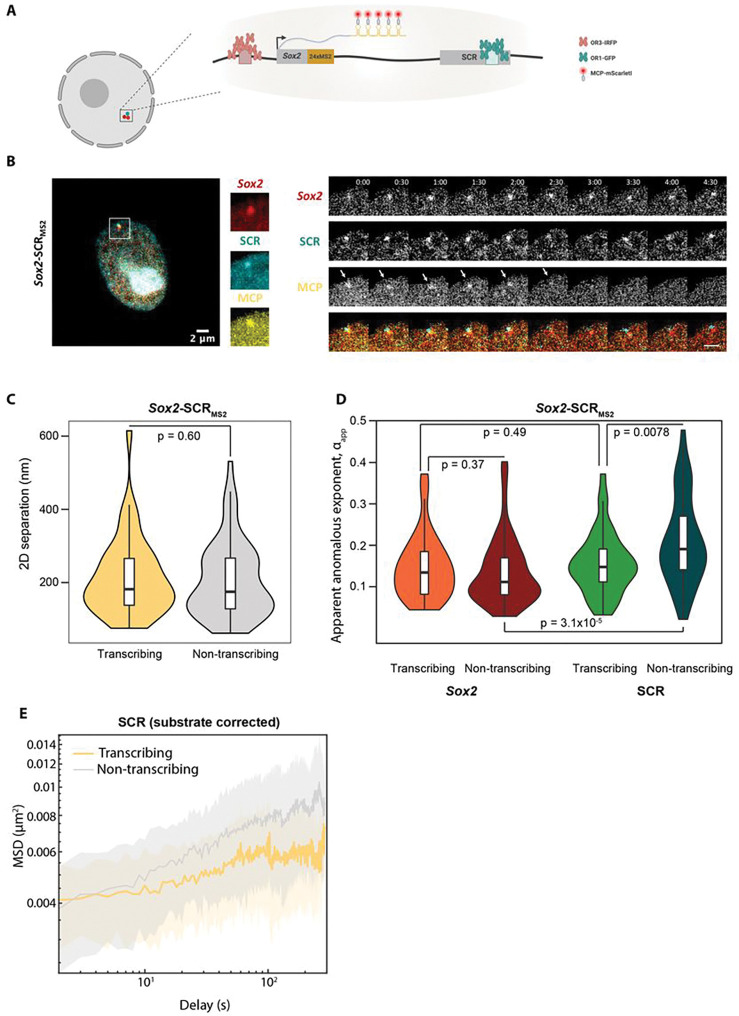

The SCR has reduced chromatin dynamics on transcriptional firing

The experiments performed so far have relied on perturbations, such as cell differentiation, cis-sequence deletions or treatment with drugs, to study effects of transcription, which are likely to have other indirect and confounding effects. To formally compare chromatin dynamics at transcribing versus non-transcribing Sox2 alleles, we generated triple-labeled ESCs (Sox2-SCRMS2), combining ANCHOR tags at the SCR and Sox2 promoter with musculus-specific incorporation of MS2 repeats into the 3’UTR of the intronless Sox2 gene59, and subsequent PiggyBac-mediated transposition of constructs for both fluorescently-labeled ParB proteins and MCP. This setup allows for simultaneous tracking of promoter, enhancer and nascent RNA (Fig. 5a,b). Previous labeling experiments at the Sox2 locus reported a significant reduction in transcription and SOX2 protein levels on incorporation of the MS2/MCP system9, presumably due to interference at the 3’UTR. We screened numerous clones to find one with the minimal perturbation of Sox2 expression, estimating from allele-specific qRT-PCR, single-molecule RNA FISH and western blotting to have a mild reduction (~ 25%) of total protein levels or estimated transcription rates in our assayed cell line, despite an apparent destabilization of the MS2-tagged mRNA when bound by MCP (Fig S6a-c). Imaging transcription bursts over two-hour windows, we measure an average bursting time of ~ 200 s and an average time between bursts of ~ 630 s. As a population, the observed cells spent ~ 36% of their time with a detected burst of transcription, nearly ten times more frequently than what was observed in the previous study using a cell line with more extensively perturbed Sox2 expression9. To measure chromatin dynamics at maximum temporal resolution, we then used this line for triple-label tracking over five-minute windows. Over this timeframe, the majority of movies were either always transcribing or always silent, but transition points were occasionally observed (Fig. 5b). When comparing transcribing and non-transcribing alleles, there were negligible differences in median promoter-enhancer separation (182 nm for transcribing, 175 nm for non-transcribing; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test; Fig. 5c) or apparent anomalous exponent of the Sox2 promoter (median 0.134 for transcribing, 0.111 for non-transcribing; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test; Fig. 5d; full data given in Table S2). Strikingly, however, we found that the enhancer is specifically more constrained on average when transcriptionally active (median for transcribing, 0.191 for non-transcribing; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test). Moreover, whereas the Sox2 promoter has a significantly smaller median apparent anomalous exponent than that of the SCR in non-transcribing loci (; Wilcoxon rank sum test), in line with what was measured in Sox2-SCRWT cells (Fig. 3c), there is no significant difference in between the two elements in transcriptionally bursting alleles (; Wilcoxon rank sum test). Finally, the corrected MSD curves for transcriptionally active loci specifically display a plateau at larger time lapses (Fig. 5e and Fig S6d). This is more pronounced for SCR dynamics, but the Sox2 promoter also shows similar behavior, suggesting that both elements are effectively confined within a defined volume during transcription. It is interesting to speculate that this locus restriction is a consequence of transcription taking place in very specified nuclear foci15 and/or condensates21, although chromatin dynamics will need to be traced over longer time periods, spanning several transcription bursts, to determine whether any volume restriction is exclusive to active states. Overall, this direct observation of chromatin dynamics relative to ongoing transcription shows an expectedly high cell-to-cell variability26, with the recurrent trend that in wild-type ESCs, the highly expressed Sox2 gene appears to have high constraints to local mobility that are not altered by transcriptional state. On the other hand, the SCR, while maintaining relative proximity (but not necessarily complete juxtaposition) to the target gene, has greater freedom of movement when the gene is transcriptionally poised yet inactive, but becomes constrained to levels comparable with the gene itself on transcriptional firing.

Figure 5. The SCR specifically becomes more constrained on transcriptional firing in wild-type loci.

a) Schematic of triple-label system of Sox2-SCRMS2 ESCs. The Sox2 promoter DNA is tagged with ANCH3 for visualization with the ParB protein OR3-EGFP, and the SCR is tagged with ANCH1 for visualization with the ParB protein OR1-IRFP. The 3’UTR of Sox2 contains 24 copies of the MS2 repeat for visualization of nascent RNA with MCP-ScarletI. b) Left: representative image of transcriptionally active Sox2-SCRMS2 nucleus, with the OR3-IRFP signal shown in red, the OR1-EGFP signal shown in cyan, and the mScarletI signal shown in yellow; scale bar 2 μm. Insets show zoomed regions around spots corresponding to bound parS sequences and transcription site. Right: Images of the same Sox2-SCRMS2 nucleus at 30 s intervals, showing each of the three channels individually in monochrome, and the overlaid image with the same color scheme as on the left. Arrows show the position of a transcription site (MCP+), which is inactivated by ~ 3 min. Scale bar 2 μm. c) Violin plot showing the distributions of median inter-probe distances for transcriptionally active (MCP+) and inactive (MCP−) Sox2-SCRMS2 ESCs, with no significant difference (p = 0.6; Wilcoxon rank sum test). d) Violin plot showing the distributions of apparent anomalous exponents measured from the individual movies for Sox2 and SCR in Sox2-SCRMS2 cells, comparing transcriptionally active and inactive alleles. Comparisons are made by Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with p-values given. e) Ensemble MSD curves, corrected for substrate movement and plotted on a double-log scale, comparing SCR dynamics between transcriptionally active and inactive alleles. Lines indicate median values and shading the median absolute deviation. Transcribing alleles show a more distinctive plateau on the MSD curve, suggesting that there is a stricter limit on the area that is explored.

Opposing effects of loop extrusion and promoter-enhancer communication on local chromatin mobility

Aside from transcription, chromatin topology itself may have an influence on local dynamics. For example, multiple distal interactions such as those defining TAD borders may be expected to “tether” different chromatin regions and thus impose greater constraints on their movement60. Furthermore, acute ablation of cohesin has already been shown to generally increase chromatin mobility28,40. Differentiation to neural precursors causes loss of the ESC-specific TAD border at the SCR, whereas the strong TAD border just upstream of the Sox2 promoter is maintained61 (Fig S7a). This loss of “anchoring” to distal regions could thus be responsible for the previously observed reduced mobility constraints at the SCR (and into the downstream TAD; Fig. 3f,g), potentially independent of transcriptional changes. We previously showed that in ESCs, the SCR TAD border is resilient to large genetic deletions, including SRR107, SRR111 and the predominant CTCF site at the enhancer, even though the latter site was able to mediate chromatin interactions in other contexts, presumably by stalling loop extrusion44 (CTCFSCR site in Fig. 6a). To assess the potential effect of altered loop extrusion processes on local chromatin dynamics, we generated derivative lines of Sox2-SCRWT cells, harboring homozygous deletions of 16–24 nt at the core CTCF binding motifs located either just upstream of the Sox2 promoter (Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_Sox2) or within the SCR (Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_SCR) (Figs. 6a and S7b). As expected, ChIP-qPCR confirmed that these deletions eliminated local CTCF binding (Fig S7c). Both lines maintained high expression of pluripotency marker genes (Fig S1b), and Sox2 expression was only mildly (and non-significantly) reduced in the Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_SCR line, in agreement with previous findings for homozygous deletions of this element62, although expression was reduced to ~ 60% of wild-type levels in the Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_Sox2 line (Fig S7d). In agreement with previous studies of the respective roles of these CTCF sites on Sox2-SCR interaction44,46,62, allele-specific 4C-seq and ANCHOR inter-probe distance measurements showed negligible topological changes when the SCR CTCF site is deleted and a mild reduced interaction on homozygous deletion of the Sox2 CTCF site (Fig S7e,f). Despite these somewhat limited phenotypic effects, both lines demonstrated a significantly reduced local constraint on chromatin mobility when CTCF binding was abrogated: the median apparent anomalous exponent was increased at the Sox2 promoter in Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_Sox2 cells (0.156; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test) and at the SCR in Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_SCR cells (0.235; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test), with negligible, insignificant changes to at the regulatory element which maintains CTCF binding (Fig. 6b–e). These findings mirror the observed increase in radial MSD on deletion of CTCF binding sites within a transgenic CTCF-mediated looping construct40, although the nature of this experimental setup could not distinguish whether dynamics are specifically altered locally at the CTCF anchor site, or whether they are also propagated to looping anchor partners. Our results support a more localized effect on chromatin dynamics. Previously published simulations suggest that, at short time scales consistent with our measurements, active loop extrusion increases mobility of the underlying chromatin fiber63, although cohesin loading itself generally imposes constraints on the underlying chromatin at larger scales28,40. We propose that removal of CTCF from one site, by removing the barrier to loop extrusion through it, permits a localized relaxation of movement constraints, explaining the focal increase in . The observed relaxation does not appear to efficiently propagate to their “looping partners”, presumably because actual CTCF-CTCF juxtapositions are rather rare events39. An alternative hypothesis is that the general binding of non-nucleosomal factors to DNA changes its biophysical properties to result in “stiffer”, more constrained chromatin motion. However, this is not supported in our experiments since the median apparent anomalous exponent at the SCR is actually significantly reduced (i.e. even greater mobility constraints are imposed) on deletion of multiple transcription factor binding sites at SRR107 and SRR111 (0.161; ; Wilcoxon rank sum test; Fig. 6d,e). Dispersed transcription factor binding sites at the Sox2 and other loci have been shown to cluster via protein-protein interactions in ESCs12, and such homotypic interactions are believed to be a basis for chromosome compartment formation64. Various studies suggest that loop extrusion and chromosome compartmentation are antagonistic processes organizing population-averaged chromatin architectures47,48,57,63,65. It is therefore possible that processes responsible for compartmentation are also generally antagonistic to cohesin-mediated loop extrusion.

To assess this possibility further, we ran molecular dynamics simulations of the above genetic perturbations within our framework, by either converting one or other of the CTCF-bound beads to a “neutral” one to mimic specific loss of the binding motif, or recapitulating the Sox2-SCRΔSRR107,111 line by deleting the corresponding beads, and abolishing PolII binding at the inactivated Sox2 promoter. The original model did not recapitulate the chromatin dynamics changes observed in the experiments (Fig S8). In particular, the model predicted that transcription factor site deletions at the SCR would increase mobility at the enhancer, instead of placing greater constraints as we had observed. Strikingly, better agreement to experimental observations was accomplished by increasing RNA polymerase stability at bound enhancers, effectively reinforcing the competition between transcription-linked compartmentation and loop extrusion (see Methods). In these simulations, removal of the local transcription factor binding sites placed greater constraints on the enhancer, and removal of CTCF had the inverse effect (Fig. 7a,b). Moreover, these simulations predicted greater cohesin occupancy at the SCR CTCF site on deletion of the flanking transcription factor binding sites. This may be predicted to allow more loop extrusion to pass through the locus, resulting in greater average local constraints as more alleles have stalled cohesin at the adjacent CTCF site. In support, we found by allele-specific ChIP-qPCR that binding of the cohesin subunit Rad21 is increased at the SCR CTCF site when adjacent transcription factor binding regions, SRR107 and SRR111, are deleted in cis (; two-tailed t-test; Fig. 7c), suggesting that these elements are indeed antagonistic to cohesin recruitment and/or loop extrusion. Overall, these results extend on recent studies into the effects of loop extrusion and its stalling by CTCF on chromatin dynamics, showing a surprising localized effect. Furthermore, two different mechanisms believed to contribute in building the same promoter-enhancer topology, CTCF-mediated architectures and enhancer-promoter “contacts”, presumably via specific transcription factors and potential compartmentation, may actually have opposing effects on local chromatin dynamics (Fig. 7d).

Figure 7. Competition between loop extrusion and transcriptional compartmentation can explain locus dynamics.

a) Ensemble MSD curves for the SCR, derived from molecular dynamics simulations of the Sox2 locus in wild-type or SCR mutant conditions, after factoring in reinforced competition between cohesin-mediated loop extrusion and RNA polymerase II clustering. Lines show median values and shading indicating the median absolute deviation. b) Violin plots showing distributions of apparent explored radii of the SCR after 10 s, derived from the same simulations as a. Reduction in mobility of Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111 cells, and increased mobility in SCRΔCTCF_SCR cells, compared to wild-type, is assessed by Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with p-values given. c) ChIP-qPCR quantification, expressed as fold enrichment over a negative control region, of amount of Rad21 binding at the musculus/129 (colored) or castaneus (white) alleles of the SCR CTCF site in Sox2-SCRWT and Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111 cells. Comparisons between allelic binding are made by two-tailed t-tests, with p-values given. More Rad21 is bound to the SCR CTCF site, specifically on the allele where SRR107 and SRR111 are deleted. d) Schematic of competing processes dictating dynamics at the SCR. At the top, extruding cohesin complexes (yellow) place temporary local constraints on mobility of the bound sequences. Such constraints are stabilized when the cohesin encounters bound CTCF (orange) in the appropriate orientation. At the bottom, bound RNA polymerase and transcription factors can also coordinate the Sox2 and SCR position, but are refractory to cohesin recruitment and/or extrusion, hence maintaining a relatively more mobile chromatin locus. The equilibrium of these two processes, shifted by deletion of the flanking transcription factor binding sites in Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111 cells, results in more constrained chromatin on average. e) Two-step model of Sox2 transcription, and its consequences for locus mobility. In the poised state (left), the Sox2 gene resides within a microenvironment of concentrated transcription factors, whereas the SCR is outside and exchanging with less concentrated factors within the nucleoplasm. Due to its dense environment, greater constraints are placed on local chromatin mobility. In the transcribing state (right), the enhancer is more constrained on entering the same hub or microenvironment, and this more efficient exchange with the gene allows transcriptional firing. The gene, while constantly constrained, has more local kinetic energy as a potential consequence of transcription itself. Note that the physical distance between SCR and Sox2 is less important in this model than whether or not the elements are residing in the same environment.

DISCUSSION

By combining live imaging of labeled endogenous loci with a battery of perturbation experiments and molecular dynamics simulations, we have teased apart some of the spatiotemporal complexities of enhancer-promoter communication. The ANCHOR system employs relatively small tags that can be placed extremely close to genomic loci of interest with negligible observable effects on transcription, nuclear organization and cell state, so is a valuable tool for such studies. The first question we addressed was whether promoters and enhancers need to directly juxtapose for transcriptional firing, since conventional C-method and light microscopy approaches have given rather different viewpoints20. We found that Sox2 and the SCR are frequently in close proximity, and significantly closer than control regions of identical genomic separation, in agreement with Hi-C predictions. However, transcriptionally active loci can be also be found with greater physical separation between the Sox2 and SCR than non-transcribing alleles (Fig. 5C), strongly arguing against any obligation for their direct juxtaposition for expression. Moreover, average promoter-enhancer distances were unchanged in all transcriptional perturbations in this study that did not affect the TAD border at the SCR, completely in line with recent C-method studies at this locus44,46. So if direct juxtaposition of the enhancer is not required for transcription, how close is close enough? Clusters of PolII and transcription factors have been observed to have diameters of ~ 100–200 nm in live nuclei12,13, providing a reasonable first estimate of the size of proposed transcriptional hubs, and thus the maximum separation of regulatory elements if they need to share the same microenvironment for transcriptional firing. What is unclear so far is whether the enhancer needs to be engaged near the gene body during the whole transcriptional cycle, or if it is free to disengage after initiation in a “hit and run” mechanism. Since the measurements made in this study are below the diffraction limit of our microscopy setup, we could not resolve these models in this study, nor exclude extremely small but potentially functionally important changes in enhancer-promoter proximity. However, since the SCR is less constrained than Sox2 in non-transcribing alleles, but has average dynamics indistinguishable from the promoter when the gene is transcribed, our results indirectly favor enhancer engagement in the gene’s microenvironment on at least the minute scale, in line with studies in a Drosophila transgene7. Studies in loci with more distal enhancers, particularly those which seem to depend on cohesin-mediated loop extrusion for gene activation (presumably as a mechanism to help the enhancer “find” its distal target)42,43, in combination with visualization of any transcriptional hubs themselves, will be required to formally address these questions.

Whereas average inter-probe distances only demonstrated subtle differences at best in this study, MSD plots revealed more dramatic locus- and condition-specific differences in chromatin dynamics, with the most obvious being the greater relative freedom of movement of control sequences compared to the constrained promoter and enhancer. Conventional fits to ensemble log-transformed MSD curves are not precise and only robustly identify very flagrant differences in dynamics; our previously developed GP-FBM framework demonstrably gives greater precision in diffusive property measurements of single trajectories, both on simulations25 and in complex and noisy experimental data (see fits in Fig S5a). A limitation of this approach, which is also shared by radial MSD analysis, is the requirement to use cross-correlations of co-measured trajectories to correct for global nuclear movements and rotations, which can be quite large in ESCs (trials of alternative means to measure substrate movement revealed them to be much less robust). There is the possibility that a perturbation could affect the coupling of the two labeled loci more than the individual particle dynamics in themselves, which could be missed by GPTool measurements, but this does not seem to be the case, since most perturbations were found to have localized effects on only SCR or Sox2, and not both together.

The major question we wished to address was how chromatin mobility is affected by transcription. For the Sox2 locus, we found clear links between chromatin dynamics and gene expression: the constrained promoter, but not the SCR, was sensitive to strong transcriptional inhibition by either enhancer element deletion or triptolide treatment, becoming even less mobile. Furthermore, when directly comparing transcribing and non-transcribing alleles within minimally perturbed cells, Sox2 promoter dynamics were relatively unaltered, whereas the SCR became more constrained upon transcriptional firing of its partner gene. A model that may explain these findings are that there are (at least) two distinct processes linking transcriptional control and local chromatin mobility: entry into a transcriptional hub/microenvironment, and transcription itself (Fig. 7e). In the first process, apparent confinement within a more limited volume, perhaps delimited by a hub, or perhaps just because of a generally more crowded nuclear environment containing transcriptional activators, underlying chromatin mobility of the locus is reduced. Second, as proposed previously30, the ATP hydrolysis and/or PolII tracking associated with transcription may be expected to add kinetic energy to the local chromatin and thus increase its mobility. In this manner, the results could be explained by the Sox2 gene, a key pluripotency gene with many constitutive and tissue-specific transcription factor binding sites at its promoter and proximal enhancers, as frequently nucleating its own transcriptionally competent microenvironment in ESCs, partly explaining its consistent low mobility. The SCR, in contrast, has dynamics behavior consistent with it specifically entering the same environment as Sox2 (and hence increasing its constraint) on transcriptional activation. Although the SCR is itself transcribed58, this is at much lower levels than Sox2, so may not feature significantly in the measurements. While explaining our results, and coherent with results from different prior studies, this hypothesis requires experiments beyond current technological capabilities to formally test, simultaneously tagging transcriptional “hub” components, nascent RNA and the promoter and enhancer over sufficiently long time periods to cover multiple transcription cycles while maintaining high temporal resolution. However, the results of our study alone are highly evocative in suggesting that some loci may be able to nucleate their own transcription-competent microenvironments, whereas others need to “find” them, raising questions about whether and how such a “hierarchy” is formed, and the mechanisms influencing the search time to access transcriptional environments.

As Sox2 and the SCR are strong TAD borders in ESCs, and cohesin-mediated loop extrusion has recently been shown to affect chromatin mobility40, much of their local constraints could perhaps be explained by mechanisms independent of transcription. Indeed, abrogation of CTCF binding caused localized increases in chromatin mobility, which was particularly noteworthy at the SCR, considering that deletion of this site had negligible changes on global chromatin conformation (as determined by population-average 4C-seq) or Sox2 expression. We also note that identifying the localized changes in chromatin dynamics is only possible by the analytical framework that we have developed, and not by conventional radial MSD. Even more striking was the finding that deletion of transcription factor binding sites had opposing effects on local dynamics to CTCF site deletion. Assuming that transcription factor clustering is one aspect of chromosome compartmentation50, this is reminiscent of the known antagonism between loop extrusion and compartments in defining chromosome conformations (Fig. 7d). Indeed, our molecular dynamics simulations required direct competition between the loop extrusion and transcription-linked interaction processes to recapitulate the experimental findings. This model and our experimental data imply a) that stalled cohesin is quantitatively more constraining than any transcription-linked microenvironments; b) that transcription factor clusters impede loop extrusion without causing stalled cohesin. This latter point is supported by the recent finding that transcription start sites form cohesin-independent TAD borders66, although the exact mechanisms are unclear, particularly as SMC complexes are able to bypass RNA polymerase and other large chromatin complexes in vitro67. Whatever the exact mechanisms, the implications for transcriptional regulation are very important: loop extrusion is believed necessary to allow the more distal enhancers to search effectively for their targets, but may actually be a barrier itself to forming the transcriptionally competent microenvironment. More detailed studies on the interplay of these two processes in living cells will be highly challenging but fascinating.

The Sox2 locus, containing an ESC-dedicated (super)enhancer ~ 150 kb from the promoter, comprising clusters of binding sites for tissue-specific transcription factors oriented around one major CTCF site facing the gene, and with no other confounding genes within the locus, was a convenient model for the studies presented here. Although many of the organizational principles uncovered here likely apply to many genes, more systematic studies will be required to formally test this. For example, the limited deletion studies performed so far have already shown large differences in robustness of TAD structures to loss of specific CTCF sites68, which could also play out in their dynamics. The ANCHOR system and its derivatives, coupled to orthogonal systems to track nuclear hubs and loop extrusion processes, will open new avenues to understanding the spatiotemporal regulation of transcription.

METHODS

Cell lines and culture

Mouse F1 ESCs (M. musculus129 × M. castaneus female cells obtained from Barbara Panning) were cultured on 0.1% gelatin-coated plates in ES medium (DMEM containing 15% FBS, 0.1 mM MEM nonessential amino-acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1000 U/mL LIF, 3 μM CHIR99021 [GSK3β inhibitor], and 1 μM PD0325901 [MEK inhibitor]), which maintains ESCs in a pluripotent state in the absence of a feeder layer69,70. The Sox2-SCRWT and Inter-Down lines were generated by allele-specific CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in of ANCH1 sequence51 into the SCR or downstream control region, and ANCH3 sequence26 into the Sox2 promoter-proximal region or intervening control region, respectively. Flanking homology arms were first introduced by PCR amplification and Gibson assembly into vectors containing the ANCH1 or ANCH3 sequence, and 1 μg of each vector were co-transfected with 3 μg of plasmid containing Cas9-GFP, a puromycin resistance marker and a scaffold to encode the two gRNAs specific to the two insertion sites (generated by the IGBMC molecular biology platform) in 1 million F1 ESCs with Lipofectamine-2000. SNPs remove the NGG PAM sequence at the castaneus allele, assuring allele-specific knock-in (sequences given in Table S3). Two days after transfection, the cells were cultured for 24 h with 3 μg/mL, then 48 h with 1 μg/mL puromycin to enrich for transfected cells, before sorting individual GFP-positive cells into 96-well plates and amplification of individual clones. Heterozygous clones with the correct sequences inserted in the musculus allele were screened by PCR and sequencing.

Sox2-SCRΔSRR107+111 cells were derived from the Sox2-SCRWT line, essentially as in ref 44. Briefly, musculus-specific deletion of SRR111 was first achieved by co-transfection with plasmids containing four allele-specific gRNAs and Cas9D10A-GFP using Lipofectamine-2000, then PCR screening as in ref 71. Heterozygous deletion clones were subsequently co-transfected with vectors containing two allele-specific gRNAs and Cas9-GFP to delete SRR107 (sequences given in Table S3).

Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_Sox2 and Sox2-SCRΔCTCF_SCR cells were derived from the Sox2-SCRWT line, essentially as in ref 62. 1 million cells were co-transfected with 2 μg plasmid containing Cas9-GFP, a puromycin resistance marker and a scaffold to encode a gRNA targeting the relevant CTCF site (generated by the IGBMC molecular biology platform; sequences given in Table S3) and 1 μg Alt-R homology-directed repair single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide (IDT; sequences given in Table S4) with Lipofectamine-2000. The repair oligonucleotides are designed to replace the CTCF motif with an EcoRI site to help screening knock-outs. Two days after transfection, the cells were cultured for 24 h with 3 μg/mL, then 48 h with 1 μg/mL puromycin to enrich for transfected cells, before sorting individual GFP-positive cells into 96-well plates and amplification of individual clones. Deletions were evaluated on agarose gel after PCR amplification of the region around the deletion and EcoRI digestion. Homozygous deletions were confirmed by sequencing.

Sox2-SCRMS2 cells were derived from the Sox2-SCRWT line by co-transfecting 1 million cells with 2 μg plasmid containing Cas9 and the scaffold encoding a gRNA at the Sox2 3’UTR, and 2 μg targeting vector containing the MS2 cassette, comprising 24 copies of the v6 MS2 repeat59, a hygromycin resistance cassette flanked by loxP sites, and primer binding sites to facilitate screening for inserted clones, following the strategy of ref 72 (Fig S9), with Lipofectamine-2000. Three days after transfection, cells with integrated vector were selected with nine days of treatment with 200 μg/mL hygromycin. Individual cells were sorted into 96-well plates for clonal amplification, which were screened for heterozygous (musculus-specific) incorporation of full length 24xMS2 repeats by PCR and sequencing. To remove the selection marker, which may perturb Sox2 mRNA function, 1 million cells were transfected with 4 μg Cre-GFP vector with Lipofectamine-2000, and after three days were subjected to selection with 6 μM ganciclovir for ten days. Marker excision and maintenance of full-length MS2 construct were verified by PCR and sequencing in surviving colonies. Finally, 1 million cells were co-transfected with 1 μg ePiggyBac transposase expression plasmid (System Biosciences) and 1 μg each epB-MCP-mScarletI, epB-OR1-EGFP and epB-OR3-IRFP vectors (the OR vectors are derived from those used in ref 25 by adding flanking inverted terminal repeats for recognition by ePiggyBac transposase; original vectors available from NeoVirTech) with Lipofectamine-2000. Nine days after transfection, fluorescent cells were sorted in bins (low, medium and high) based on expression of the different fluorescent proteins, and tested by microscopy. Cells with Scarlethigh/GFPlow/IRFPlow fluorescence were found to be optimal for imaging experiments, and this population was maintained for subsequent experiments.

Live imaging

Cells were transiently transfected with OR vectors (except for the stably expressing Sox2-SCRMS2 line) and imaged essentially as in ref 25. 150,000 cells were plated two days prior to imaging onto laminin-511-coated 35 mm glass bottom petri dishes and transfected with 2 μg each OR1-EFGP and OR3-IRFP plasmids with Lipofectamine-2000. Medium was changed just before imaging to remove dead cells. Imaging was performed on an inverted Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with a PFS (perfect focus system), a Yokogawa CSU-X1 confocal spinning disk unit, two sCMOS Photometrics Prime 95B cameras for simultaneous dual acquisition to provide 95% quantum efficiency at 11 μm × 11 μm pixels and a Leica Objective HC PL APO 100x/1.4 oil. A Tokai Hit Stage incubator allowed for maintenance at 37°C and 5% CO2 throughout the experiment. The system was controlled using Metamorph 7.10 software. For double-label experiments, EGFP and IRFP were excited by 491-nm and 635-nm lasers. Green and far-red fluorescence were detected with an emission filter using a 525/50 nm and 708/75 nm detection window, respectively. Time-lapse was performed in 2D, acquiring 241 time points at 0.5 s interval. For triple-label experiments, EGFP and IRFP were first imaged as for the double-label, then mScarletI was excited at an identical z-position with a 561-nm laser, and red fluorescence was detected with an emission filter using a 609/54 nm detection window. Time-lapse was performed in 2D, acquiring 301 time points at 1 s interval. For assessment of transcriptional bursting of Sox2-SCRMS2 cells, mScarletI was excited with a 561-nm laser, and red fluorescence was detected with an emission filter using a 609/54 nm detection window. Ten positions were taken per acquisition session, obtaining 20 z-stacks of 0.5 μm interval for each position every 2 min, for a total of 2 hr. All time lapse was performed with Perfect focus system (PFS) of the microscope to avoid any focus drift.

ESC differentiation

ESCs were passaged onto laminin-511-coated 35 mm glass bottom petri dishes, transfected with OR vectors as previously, and switched to DMEM (4.5 g/L glucose) supplemented with 2 mM GlutaMAX, 10% FBS, 0.1 mM MEM nonessential amino acids, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol without LIF or 2i inhibitors. After 24 h, the medium was changed daily and supplemented with 5 μM retinoic acid.

Triptolide treatment

Two days after transfection with OR vectors, as previously, cell medium was changed for fresh medium, supplemented with either 500 nM triptolide or 1:2000 dilution of DMSO and incubated for 4 h prior to image acquisition.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Nucleospin RNA extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel) and reverse-transcribed using random hexamer primers and SuperScript IV (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR was performed on 10 ng cDNA aliquots in technical triplicates per biological replicate (three minimum) using QuantitTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen). Amplification was normalized to SDHA (succinate dehydrogenase complex flavoprotein subunit A). SNPs allowed primer design to distinguish musculus and castaneus Sox2 expression44. Primer sequences are given in Table S5. Statistical comparisons were made by two-tailed t-tests.

Cell cycle analysis

1 million cells were fixed in 66% ethanol on ice for 2 h, washed with PBS, then resuspended in 750 μL 50 μg/mL propidium iodide and 2 μg/mL RNase A in PBS, before incubation at 37°C for 30 min. Analysis of propidium iodide staining with a FACS Fortesa (BD Biosciences) allowed cells to be gated to G1 (2n DNA content), S (2n < DNA content < 4n) and G2/M (4n DNA content) phases. Statistical comparisons were made by two-tailed t-tests.

Allele-specific 4C-seq

4C-seq was essentially carried out as in ref 44. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in 10% FBS in PBS for 10 min at 23°C. The fixation was quenched with cold glycine at a final concentration of 125 mM, then cells were washed with PBS and permeabilized on ice for 1 h with 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, and protease inhibitors. Nuclei were resuspended in DpnII restriction buffer at 10 million nuclei/mL concentration, and 5 million nuclei aliquots were further permeabilized by treatment for 1 h with 0.4% SDS at 37°C, then incubating for a further 1 h with 3.33% Triton X-100 at 37°C. Nuclei were digested overnight with 1500 U DpnII at 37°C, then washed twice by centrifuging and resuspending in T4 DNA ligase buffer. In situ ligation was performed in 400 μL T4 DNA ligase buffer with 20,000 U T4 DNA ligase overnight at 23°C. DNA was purified by reverse cross-linking with an overnight incubation at 65°C with proteinase K, followed by RNase A digestion, phenol/chloroform extraction, and isopropanol precipitation. The DNA was digested with 5 U/μg Csp6I at 37°C overnight, then re-purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation. The DNA was then circularized by ligation with 200 U/μg T4 DNA ligase under dilute conditions (3 ng/μL DNA), and purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation. For musculus-specific 4C profiles, samples of the DNA were digested with AvaII, cutting specifically at the region between the Csp6I site and the non-reading primer annealing site on the castaneus allele. 100 ng aliquots of treated DNA were then used as template for PCR with bait-specific primers containing Illumina adapter termini (primer sequences in Table S6). PCR reactions were pooled, primers removed by washing with 1.8× AMPure XP beads, then quantified on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent) before sequencing with a HiSeq 4000 (Illumina). Sequencing read fastq files were demultiplexed with sabre (https://github.com/najoshi/sabre) and aligned to the mm10 genome with Bowtie73, and intrachromosomal reads were assigned to DpnII fragments by utility tools coming with the 4See package54. 4See was also used to visualize the 4C profiles. Interactions were called for each replicate with peakC74 with window size set to 21 fragments, and were then filtered to only include the regions called as interacting across all wild-type replicates. For statistical comparison of specific interactions, the 4C read counts within 1 Mb of the bait for all replicates and conditions (from the same bait) were quantile normalized using the limma package75. The means of summed normalized 4C scores over tested interacting regions were taken as “interaction scores”, and were compared across conditions by two-tailed t-tests.

3D DNA FISH

FISH probes were generated by nick translation from fosmids centered on the ANCHOR insertion sites (WI1–2125O9 for Sox2, WI1–788C1 for Inter, WI1–111C20 for SCR, WI1–156F5 for Down), labeling the DNA with dUTP conjugated to biotin (SCR and Down probes) or digoxigenin (Sox2 and Inter probes). For each hybridization experiment, 300 ng each probe was combined with 3 μg mouse C0t DNA and 20 μg yeast tRNA and resuspended in 5 μL hybridization mix (10% (w/v) dextran sulphate, 50% formamide, 1% Tween-20 in 2x SSC). Probe was denatured at 95°C for 5 min just before application to cells. FISH was performed as in ref 76. Briefly, cells were plated on 0.1% gelatin-coated coverslips in ES medium and fixed after 5 h (before colony formation) for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, then permeabilized for 20 min in 0.5% (w/v) saponin, and incubated for 15 min with 0.1 N HCl, with washes in PBS between each incubation. Cells were then washed in 2x SSC and equilibrated in 50% formamide/2x SSC, before co-denaturing nuclei and probes at 85°C for 5 min, then hybridizing overnight at 37°C in a humidified chamber. Cells were washed three times with 50% formamide/2x SSC at 45°C for 5 min each, then three times with 1x SSC at 60°C for 5 min each, before cooling to room temperature in 0.05% Tween-20/4x SSC and blocking for 20 min in 3% BSA in 0.05% Tween-20/4x SSC.

Anti-digoxigenin-rhodamine and fluorescein-avidin DN were diluted 1:100 in the same blocking solution and incubated with the cells for 1 h. Cells were washed three times for 5 min in 0.05% Tween-20/4x SSC, then coverslips were mounted in DAPI-containing Vectashield mounting medium. Interphase nuclei were imaged on a LSM 880 AxioObserver (Olympus) microscope, using a x63/1.4 objective lens (C plan-Aprochromat 63x/1.4 Oil DIC UV-VIS-IT M27), under 2x zoom and line-averaging 4 settings. The interval between z-slices was 0.37 μm and the x- and y-pixel size was 132 nm. Nuclei were segmented and inter-probe 3D distances were measured by custom scripts in ImageJ77. Distance distribution differences were assessed by Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

Single-molecule RNA FISH

MS2v6 and Sox2 probes were designed with Stellaris Probe Designer and labeled with Cy3 and Cy5, respectively, on the 3’ ends. Glass coverslips were placed into a 12-well plate and coated overnight with Poly-d-lysine. 400,000 cells were seeded per well and allowed to attach for 3 h to 70–80% confluency at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were washed three times with pre-warmed HBSS buffer (Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution; no calcium, magnesium or phenol red; Thermo Fisher), before aspiration of buffer and cell fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at 23°C, then two washes in PBS for 10 min at 23°C. Cells were permeabilized overnight in 70% ethanol at 4°C, then washed for 5 min at 37°C with pre-warmed wash buffer (10% (v/v) formamide in 2x SSC). Coverslips were aspirated and dried for 5 min, before applying hybridization mix (50 nM each probe in 10% (w/v) dextran sulphate sodium salt, 10% (v/v) formamide, 2x SSC) and incubating overnight at 37°C in a humidified chamber. Coverslips were washed three times in wash buffer for 30 min at 37°C, then rinsed in 2x SSC and washed in PBS for 5 min at 23°C. Samples were mounted in Prolong Gold with DAPI (Invitrogen) on glass slides, and left to dry in the dark for 24 h before imaging on a Zeiss AxioObserver 7 inverted wide-field fluorescence microscope with LED illumination (SpectrX, Lumencor) and sCMOS ORCA Flash 4.0 V3 717 (Hamamatsu). A 40x oil objective lens (NA 1.4) with 1.6x Optovar was used. 27 z-stacks with 300 nm slices and 1×1 binning were taken with an exposure time of 500 ms for Cy3, 750 ms for Cy5 (100% LED power for both), and 25 ms for DAPI (10% LED power). Micromanager 1.4 software was used. A custom Python script was used to detect, localize and classify the spots (https://github.com/Lenstralab/smFISH). Cells and nuclei were segmented using Otsu thresholding and watershedding. Spots were localized by fitting a 3D Gaussian mask after local background subtraction78 and counted per cell.

Western blot

~ 3 million cells were collected by trypsinization, washed with PBS and lysed in 100 μL RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) NP-40, 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 1 mM EDTA) for 30 min at 4°C. Cell lysate was sonicated with a Covaris E220 Bioruptor in AFA microtubes to shear genomic DNA (peak incident power 175 W, duty factor 10%, 200 cycles per burst, 150 s), before addition of 100 U benzonase (Sigma) in 100 μL RIPA buffer and incubation for 30 min at 30°C. Lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 22,000 g for 20 min at 4°C and protein concentration was measured with a Bio-Rad protein assay. 30 μg protein extract was loaded onto a 15% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis then transfer to a PVDF membrane using a Mini Trans Blot Cell (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at 23°C in 4% milk/PBST (0.1% Tween-20 in PBS), then incubated with primary antibody (anti-SOX2, Santa Cruz #sc-365823; anti-histone H3, H31HH.3EI-IGBMC) at 1:1000 dilution in 4% milk/PBST overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed four times for 5 min each at 23°C in PBST, then incubated with 1:10,000 goat anti-mouse-alkaline phosphatase (IGBMC) in 4% milk/PBST for 1 h at 23°C, before washing four times for 5 min each at 23°C in PBST and developing with Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo Fisher). Image acquisition was performed on ImageQuant 800 (Amersham).

ChIP-qPCR