Abstract

Background and aims:

In this study ten mouse strains representing ~ 90% of genetic diversity in laboratory mice (B6C3F1/J, C57BL/6J, C3H/HeJ, A/J, NOD.B1oSnH2/J, NZO/HILtJ, 129S1/SvImJ, WSB/EiJ, PWK/PhJ, CAST/EiJ) were examined to identify the mouse strain with the lowest incidence of cancer. The unique single polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with this low cancer incidence are reported.

Methods:

Evaluations of cancer incidence in the 10 mouse strains were based on gross and microscopic diagnosis of the occurrence of tumors. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the coding regions of the genome were derived from the respective mouse strains located in the Sanger mouse sequencing database and the B6C3F1/N genome from the National Toxicology Program (NTP).

Results:

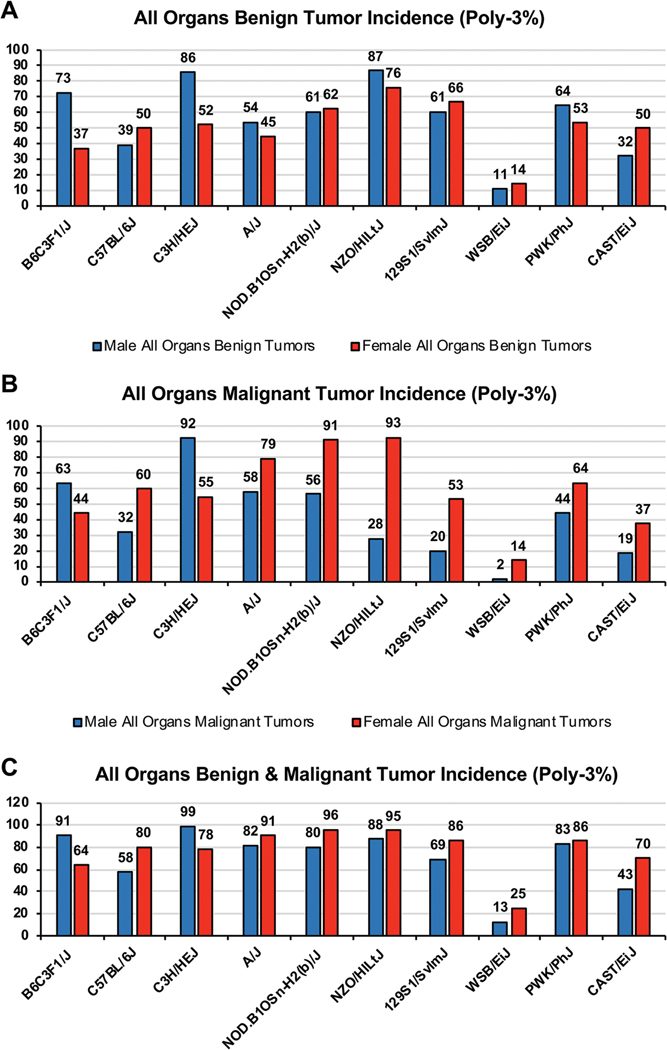

The WSB strain had an overall lower incidence of both benign and malignant tumors compared to the other mouse strains. At 2 years, the incidence of total malignant tumors (Poly-3 incidence rate) ranged from 2% (WSB) to 92% (C3H) in males, and 14% (WSB) to 93% (NZO) in females, and the total incidence of benign and malignant tumor incidence ranged from 13% (WSB) to 99% (C3H) in males and 25% (WSB) to 96% (NOD) in females. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) patterns were examined in the following strains: B6C3F1/N, C57BL/6J, C3H/HeJ, 129S1/SvImJ, A/J, NZO/HILtJ, CAST/EiJ, PWK/PhJ, and WSB/EiJ. SNPs in the coding regions of the genome were derived from the respective mouse strains located in the Sanger mouse sequencing database and the B6C3F1/N genome from the National Toxicology Program (NTP). We identified 7,519 SNPs (involving 5,751 Ensembl transcripts of 3,453 Ensembl Genes) that resulted in a unique amino acid change in the coding region of the WSB strain.

Conclusions:

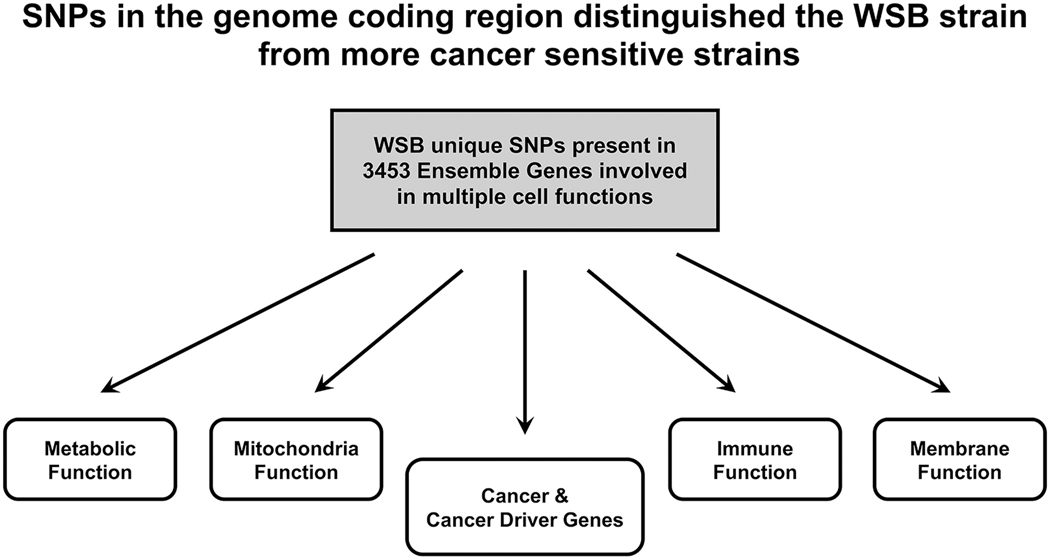

The inherited genetic patterns in the WSB cancer-resistant mouse strain occurred in genes involved in multiple cell functions including mitochondria, metabolic, immune, and membrane-related cell functions. The unique SNP patterns in a cancer resistant mouse strain provides insights for understanding and developing strategies for cancer prevention.

Keywords: Single nucleotide polymorphisms, mouse strains; cancer, mitochondria, immune, metabolic, membrane-related functions

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Previous studies have shown that inherited factors can impact the development of cancer (Lichtenstein et al., 2000). These inherited factors may be those that affect multiple cell functions including metabolic and immune function (Hanna et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2016). In this study we examined cancer development in 10 genetically diverse mouse strains to identify and characterize the mouse strain with the lowest cancer incidence. This involved an examination of unique single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) patterns in the coding region to differentiat a cancer resistant mouse strain found in this study from the other nine cancer sensitive mouse strains (Thomas and Kejariwal, 2004). Single polymorphisms help to describe the disease susceptibility of a specific mouse strain (Hunter et al., 2018).

The ten mouse strains in this study represent ~90% of mammalian genetic diversity (Roberts et al., 2007) and come from seven branches of the mouse family tree (Petkov et al., 2004). This included seven classical inbred (Bogue et al., 2016) mouse strains (B6C3F1/J, C57BL/6J, C3H/HeJ, 129S1/SvImJ, A/J, NOD.B10Sn-H2b/J, NZO/HILtJ) and three wild-derived strains (CAST/EiJ, PWK/PhJ, WSB/EiJ). This set of ten mouse strains included the eight founder mouse strains (or related strains) (A/J, C57BL/6J, 129S1/SvImJ, NOD/ShiLtJ, NZO/HILtJ, CAST/EiJ, PWK/PhJ, and WSB/EiJ) used in the development of the Collaborative Cross (CC) (Welsh et al., 2012) and the Diversity Outbred (DO/J) mice (Churchill et al., 2012). The B6C3F1/J and its other parental strain, C3H/HeJ, round out the set of ten strains studied. In these studies, the related NOD.B10Sn-H2b/J strain was substituted for the NODH2g/LtJ (diabetogenic MHC H2g haplotype) used as a collaborative cross because of limited availability of the original NOD strain.

The mouse mammalian genome has many genetic similarities to the human genome (Guénet, 2005). Using inbred mouse strains to identify disease-risk patterns enables discovery of genetic loci linked to the disease phenotype since each strain is homogenous. The ten mouse strains were used in this study to identify genomic characteristics that correlate with cancer development as animals age (Wojcik et al., 2019). For eight of the mouse strains, the strain specific mouse genomic sequence data was available from the Sanger mouse genome database (Wellcome Sanger Institute, 2020 (accessed)) and the genomic sequence for the B6C3F1/N mouse was obtained from the National Toxicology Program (Grimm et al., 2019). In this study, the environment was controlled in a managed animal facility to minimize its contribution to disease so that the study could focus on how single nucleotide polymorphisms may explain differences in cancer as animals age.

In this “genetic era” of disease, identifying genetic factors that predispose to a disease risk such as cancer is an important focus of study by many investigators. This project focused on identifying genetic factors that were related to cancer resistance. We hypothesized that differential SNP patterns in protein-coding genes would distinguish the WSB strain, the cancer resistant strain, from the other more cancer susceptible strains. This hypothesis was tested by examining SNP patterns in the coding region of the genome in more cancer susceptible mouse strains versus the cancer resistant mouse strain. We report SNP patterns in cancer and cancer driver genes, and the SNP patterns in other functional gene classes that can impact cancer development. It is expected that the incidence of cancer will continue to rise in the coming decades, and accumulating knowledge on genetic backgrounds for cancer resistance may contribute to developing strategies for combating cancer. The purpose of this paper is to report genetic characteristics of the WSB/EiJ mouse strain with an overall low incidence of benign and malignant tumors compared to nine other mouse strains.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

One hundred fifteen male and female mice each from ten genetically diverse mouse strains (129S1/SvImJ, NOD.B10Sn-H2b/J, C57BL/6J, A/J, NZO/HILtJ, CAST/EiJ, C3H/HeJ, PWK/PhJ, WSB/EiJ, and B6C3F1/J) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) at 4–5 weeks of age. After a 3-day quarantine, animals were maintained for 106–107 weeks or until survival declined to 20%, at which time all surviving animals in the group were euthanized and necropsied. The 20% survival rule was used for early termination of the NZO/HILtJ males and females, the NOD.B10Sn-H2b/J males, and the CAST/EiJ females. Mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation at scheduled necropsy at 2 years or earlier if they were in moribund condition.

2.2. Animal housing and care

The environmental conditions for the ten mouse strains were kept constant. Mice were housed in solid polycarbonate cages (Lab Products, Inc. Seaford, DE). For each strain, female mice were housed in groups of five per cage and male mice were housed individually. Due to aggressive behavior including fighting, CAST/EiJ female mice were individually housed starting study week 20. The mice were housed in rooms maintained at a humidity of 35 – 65 %, temperature at a range of 69–75 F°, and a 12-hour light-dark cycle. Tap water and irradiated NTP 2000 diet (Zeigler Brothers, Inc. Gardners, PA) were made available ad libitum. Racks were changed every 2 weeks. At the time of rack change-out, racks were rotated within the study room and cages were rotated within racks. Body weigths and survival were recorded throughout the study.

The care of animals was according to NIH procedures as described in the “The U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”, available from the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, RKLI, Suite 360, MSC 7982, 6705 Rockledge Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892–7982 or online at http://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/olaw.htm#pol.

The incidence of benign and malignant tumors in the ten mouse strains were diagnosed by gross and microscopic examination of the major organ systems in each strain. All tissue collections, necropsies, tissue processing and histopathology were performed according to NTP specifications http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/test_info/finalntp_toxcarspecsjan2011.pdf). NTP guidelines were used for all pathology nomenclature (http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/nnl/). Histological examination was performed by experienced board certified veterinary anatomic pathologists. Complete necropsies were performed on all animals when moribund, when found dead, or at the end of the two-year exposure period. At necropsy, all organs and tissues were examined for grossly visible lesions. Tissues were preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin (except eyes which were first fixed in Davidson’s solution, and testes and epididymis which were fixed in modified Davidson’s solution), embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The following tissues were examined microscopically from male and/or female animals: gross lesions and tissue masses, adrenal gland, bone with marrow, brain, cervix, clitoral gland, esophagus, eyes, gallbladder (mice only), Harderian gland, heart, large intestine (cecum, colon, rectum), small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum), kidney, liver, lungs, lymph nodes (mandibular and mesenteric), mammary gland, nose, ovary, pancreas, parathyroid gland, pituitary gland, preputial gland, prostate gland, salivary gland, skin, spleen, stomach (forestomach and glandular), testis with epididymis and seminal vesicle, thymus, thyroid gland, trachea, urinary bladder, uterus with cervix), and vagina. Following completion of the studies, histopathology diagnoses were confirmed by NTP pathology peer reviews (Boorman et al., 1985). The Poly-k test for survival adjusted analysis of tumor rates with a value of k=3 was used to assess neoplasm lesion prevalence (Bailer and Portier, 1988; Piegorsch and Bailor, 1997; Portier and Bailer, 1989).

2.3. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis

The SNP patterns that are observed only in the transcriptome of WSB mouse strain were characterized since this strain is found to be the most cancer resistant relative to other strains from this study.

Towards this goal we utilized genomic sequence data from Mouse Genome Database (dbSNP142) from Sanger Institute (Keane et al., 2011; Wellcome Sanger Institute, 2020 (accessed)). The variant call file was obtained from FTP download site (https://www.sanger.ac.uk/science/data/mouse_genomes_project) on September 6, 2017. This file consisted of SNP call results for 42 male mice strains including 8 out of 10 strains that were common to this aging study: 129S1/SvImJ, C57BL/6J, A/J, NZO/HILtJ, CAST/EiJ, C3H/HeJ, PWK/PhJ and WSB/EiJ.

Furthermore, we utilized DNA sequencing data from NIEHS Mouse Methylome study (Grimm et al., 2019) to derive SNP calls for B6C3F1/N male/females, because this strain is used in almost all NTP rodent cancer studies. Quality checks were performed on the DNA sequence data using the FastQC tool (FastQC, 2021 (accessed)) and then the adapters were trimmed using the Trimmomatic tool (Bolger et al., 2014). The trimmed reads were aligned to the mm10 genome using bwa mem (Li and Durbin, 2009). The B6C3F1 DNA sequence data was processed using the Broad Institute’s Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) workflow (McKenna et al., 2010). PCR duplicates were identified using Picard’s MarkDuplicates tool (Broad Institute, 2021 (accessed)). The base quality scores were recalibrated using GATK BaseRecalibrator and variants were obtained using GATK HaplotypeCaller (McKenna et al., 2010). Variants showing strand bias, mapping errors or low coverage were removed using GATK’s VariantFiltration utility. SNPs calls were assigned for the eight strains listed above.

SNP calls were mapped to Ensembl transcript and corresponding amino acid sequence changes were identified. First, we identified 108,269 SNPs (mapped to 34,262 Ensembl transcripts and 17,171 Ensembl genes) that resulted in amino acid change for at least one of 9 strains (This data is provided in supplemental file S1). For downstream characterization, this list was further narrowed to 7,519 SNPs (involving 5,751 Ensembl transcripts of 3,453 Ensembl Genes) that resulted in an amino acid change in the coding region of the WSB strain only.

3. Results

3.1. Body weight and survival

Body weights of the WSB/EiJ male and female mice were among the lowest of the ten mouse strains. The mean body weight at study initiation for WSB/EiJ males was 12.1 grams and for females, 9.7 grams. The mean body weight at study termination was for WSB/EiJ males 21.3 grams, and for females, 20.2 grams. Final survival for the WSB/EiJ males was 83.2 % and for females, 78.6%.

3.2. Cancer phenotype

The cancer phenotype of ten mouse strains was determined by conducting a complete histopathologic analysis of the ten strains in this study at the end of two years. The WSB mouse was found to have the lowest incidence of benign and malignant tumors compared to the other nine strains (Figure 1). The total malignant tumor Poly-3 adjusted incidence ranged from 2% (WSB) - 92% (C3H) in males, and 14% (WSB) - 93% (NZO) in females for the ten mouse strains examined. The total benign and malignant tumor Poly-3 adjusted incidence ranged from 13% (WSB) – 99% (C3H) in males, and from 25% (WSB) to 96% (NOD) in females. The difference in cancer incidence in the ten mouse strains kept under the same environmental conditions provides support for the hypothesis that genetic differences contribute to cancer susceptibilities as animals age. We followed up on this finding with the SNP analyses in the coding region of the genome for the WSB mouse and the other mouse strains to identify unique WSB SNP patterns.

Figure 1.

A. Overall Poly-3% percent of benign tumors; B. Overall Poly-3% percent of malignant tumors; C. Over Poly-3% percent of benign and malignant tumors

3.3. SNP patterns

The SNP pattern across the mouse strains showed that there were multiple SNPs in the exonic regions of the WSB mouse that differentiated this strain from the other more cancer susceptible mouse strains. There was a total of 7,519 unique SNPs in the WSB strain that differentiate this strain from the other strains in 3,453 Ensembl Genes (Supplement 1). Many of the genes had multiple SNPs in the coding region that resulted in amino acid changes. Among the WSB genes with non-synonymous SNP patterns (resulting in amino acid changes) that differed from those of the more cancer susceptible strains included genes associated with cancer, mitochondria, immune, metabolic, and membrane function (Table 1, Table 2, Supplements 1–5).

Table 1.

WSB Genes with Unique SNP patterns in Cancer (Tate et al. 2019) and/or Cancer Driver Genes (Bailey et al. 2018) (that differentiate from the other more cancer susceptible mouse strains)

| Cancer Genes with Unique WSB SNPs (Tate et al. 2019) | Cancer Driver Genes with Unique WSB SNPs (Bailey et al. 2018) | WSB Genes with Unique SNPs that are Cancer Genes and/or Cancer Driver Genes |

|---|---|---|

| AFF1 | APOB | CD79B |

| ARHGAP26 | CD79B | CDH1 |

| ARNT | CDH1 | CDK4 |

| ATIC | CDK4 | CDKN1B |

| BARD1 | CDKN1B | CIC |

| BCORL1 | CHD3 | EP300 |

| CAMTA1 | CIC | FAT1 |

| CBL | EEF1A1 | GNAS |

| CD274 | EP300 | HRAS |

| CD79B | FAT1 | IDH1 |

| CDH1 | GNAS | JAK3 |

| CDK4 | GRIN2D | KMT2A |

| CDKN1B | HRAS | KMT2C |

| CIC | IDH1 | KMT2D |

| CNBP | INPPL1 | MAP3K1 |

| CNTRL | JAK3 | MEN1 |

| CREB1 | KMT2A | MET |

| CUX1 | KMT2C | MLH1 |

| DAXX | KMT2D | NSD1 |

| DDX10 | KRT222 | POLQ |

| EIF4A2 | MACF1 | PTPRC |

| EP300 | MAP3K1 | RBM10 |

| ERC1 | MEN1 | SETD2 |

| ETV5 | MET | TET2 |

| FAT1 | MLH1 | TSC2 |

| FCGR2B | MSH3 | VHL |

| FGFR4 | MUC6 | |

| FUS | NSD1 | |

| GNAS | POLQ | |

| GOLGA5 | POLRMT | |

| HRAS | PTPRC | |

| IDH1 | RBM10 | |

| JAK3 | RFC1 | |

| KAT6B | SETD2 | |

| KMT2A | TET2 | |

| KMT2C | TLR4 | |

| KMT2D | TSC2 | |

| KNL1 | USP9X | |

| KTN1 | VHL | |

| LRP1B | ZFP36L2 | |

| MAP3K1 | ||

| MAP3K13 | ||

| MEN1 | ||

| MET | ||

| MLH1 | ||

| MYCL | ||

| MYOD1 | ||

| NCOR2 | ||

| NFKBIE | ||

| NIN | ||

| NSD1 | ||

| NSD2 | ||

| NSD3 | ||

| POLD1 | ||

| POLQ | ||

| PREX2 | ||

| PTPRC | ||

| RANBP2 | ||

| RBM10 | ||

| RNF213 | ||

| ROS1 | ||

| SALL4 | ||

| SDHA | ||

| SETD2 | ||

| SH3GL1 | ||

| TCF3 | ||

| TERT | ||

| TET1 | ||

| TET2 | ||

| TRIP11 | ||

| TSC2 | ||

| VHL | ||

| WIF1 | ||

| WRN |

Bailey MH, Tokheim C, Porta-Pardo E, et al. (2018) Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell 174(4):1034–1035 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.034

Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. (2019) COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 47(D1):D941-d947 doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1015

Table 2.

Selected WSB SNPs patterns in the coding regions of genes that differentiate the WSB mouse strain from other mouse strains

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.4. Cancer and cancer driver gene SNP Patterns

Unique WSB SNPs occurred in 74 cancer genes in the COSMIC Tier One cancer database (Tate et al., 2019) including oncogenes, protooncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, kinases, and methyl transferases (Table 1). There were 43 unique WSB SNP patterns in genes that overlapped Bailey’s (Bailey et al., 2018) list of cancer driver genes. There were 26 unique WSB SNPs in genes that are found on both the COSMIC Tier One cancer genes and Bailey’s cancer driver genes databases (Table 1). Categories found in the WSB mouse strain that overlapped those in the COSMIC database or in the cancer driver database (Bailey et al., 2018; Tate et al., 2019) included oncogenes/protooncogenes and genes whose protein product is involved with post-translational modification (e.g., kinases and transferases).

3.5. Mitochondria function gene SNP pattern

Mitochondria function genes with unique WSB SNPs included mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (Mrpl and Mrps proteins: Mrp10, Mrpl2, Mrpl2, Mrpl48, Mrps10, Mrps10, Mrps18b, Mrps28, Mrps28, Mrps5, Mrps5) (Huang et al., 2020). These mammalian mitochondrial ribosomal proteins are encoded by nuclear genes and function in protein synthesis processes within mitochondria (Huang et al., 2020).

Additional genes with unique WSB SNP patterns, were cytochrome c biogenesis proteins (Ccdc), which are hemoproteins covalently attached iron-protoporphyrin IX, and are electron carriers between enzymes involved in cellular energy transduction processes in mitochondria. The Coil domain family (Ccdc) facilitate mitochondrial respiration and many members of this family had unique WSB SNP patterns (Ccdc103, Ccdc106, Ccdc112, Ccdc114, Ccdc120, Ccdc124, Ccdc141, Ccdc144b Ccdc146, Ccdc155, Ccdc162, Ccdc170, Ccdc22, Ccdc3, Ccdc30, Ccdc33, Ccdc34, Ccdc40, Ccdc61, Ccdc71, Ccdc78, Ccdc80, Ccdc85a, Ccdc87, Ccdc88b) (Modjtahedi et al., 2016).

IBA57 a protein that localizes to the mitochondrion and is part of the iron-sulfur cluster assembly pathway also had a unique WSB SNP pattern as did Sdha - succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase, a complex of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, and Cox10 (cytochrome c oxidase) the terminal component of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, which catalyzes the electron transfer from reduced cytochrome c to oxygen (Rahman and Rahman, 2018).

3.6. Immune function gene SNP patterns

There were several categories of immune function genes with unique WSB SNP patterns that contribute to adaptive and/or innate immunity (Supplement 1 & 3). This included unique WSB SNPs in the immunoglobulin genes, Ighv, Igkv, and Igh, genes involved in adaptive immune function (Sun et al., 2020).

Other unique WSB SNP patterns were found in T cell receptor alpha variable factor genes (Trav) and T cell receptor beta locus (Trbv) genes involved in antigen processing (Guan et al., 2017)(Trav1, Trav6–7-dv9, Trav6d-7, Trav6n-6, Trav6n-7, Trav7–2, Trav7–3, Trav7–6, Trav7n-4, Trav7n-4,Trav7-n-6, Trav8d-1, Trav8n-2, Trav9–1, Trav9–2, Trav9d-4, Trav9n-1, Trav9n-4).

Unique WSB patterns were found in the C-type lectin domain family (Clec) (Clec12a, Clec12b, Clec16a, Clec18a, Clec2d, Clec2e, Clec2g, Clec2i, Clec3b, Clec4a1, Clec4a2, Cec4a3, Clec4a4, Clec4b1, Clec4d, Clec4e, Clec4n, Clec7a). Members of this family are receptors on immune cells can participate in regulating various cell functions including in cell adhesion, cell-cell signaling, glycoprotein turnover, and inflammation and immune response (Sattler et al., 2012).

Recent studies of Trim family genes (Trim) show that members of this tripartite motif-containing (TRIM) superfamily are expressed in response to interferons and are involved in a broad range of biological processes that are associated with innate immunity (Ozato et al., 2008). Some of these Trim family genes presented with distinct WSB SNP patterns (Trim12a, Trim12c, Trim14, Trim25, Trim30a, Trim30b, Trim30c, Trim30d,Trim34a, Trim34b, Trim35, Trim38, Trim5, Trim56).

Interleukins (Il10ra, Il11, Il12rb2, Il17re, Il20ra, Il23r, Il4ra, Ilkap), cytokines, and interferons (Irf7, Irf9) which help regulate immune system function (Akdis et al., 2011) had unique WSB SNP patters as did some of the Toll like – tousled-like kinase activity genes (Tlk1, Tln2, Tlr4, Tlr5). Leukotrienes – mediators of innate immunity (Lta4h, Ltbp1, Ltbp2, Ltbp3, Ltbr, Ltc4s, Ltn1), and Nlrc genes (Nlrc3, Nlrp1a, Nlrp1b, Nlrp4a, Nlrp4c, Nlrp4e, Nlrp5, Nlrp9b, Nlrp9c), immune system regulators, also had unique WSB SNP patterns. Another regulator of immune system function with unique WSB SNP patterns included PTPRC (protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type C).

Several immune specific cell surface protein markers (cluster of differentiation markers (CD) had unique WSB SNPs (Cd14,Cd151, Cd177, Cd1d2, Cd200r1, Cd200r2, Cd200r3, Cd200r4, Cd22, Cd244a, Cd248, Cd27, Cd274, Cd300a, Cd300c, Cd300e, Cd300lb, Cd300lf, Cd300lg, Cd320, Cd36, Cd4, Cd44, Cd55, Cd55b, Cd7, Cd72, Cd79b, Cd96, Cdc14b, Cdc42bpg, Cdc45 Cdc6, Cdca2, Cdca8, Cdh1). Expression of these proteins can enhance motility, invasion, and metastasis of cancer cells (Martin et al., 2020; Zola et al., 2007).

3.7. Metabolic and membrane function gene SNP patterns

WSB unique SNPs were found in metabolic and membrane function genes, and alterations in these functions are hallmarks of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). This included unique WSB SNP patterns in carboxylesterase (Ces) enzymes that hydrolyze esters, amides, thioesters, and carbamates and play an important part in lipid metabolism (Ces1a, Ces1b, Ces1e, Ces2a, Ces2b, Ces2e, Ces3b). Also prevalent among the unique WSB SNP patterns, were those in many of the genes for cytochrome P450 enzymes (Cyp1a2, Cyp1b1, Cyp2c50, Cyp2c68, Cyp2c70, Cyp2d10, Cyp2d11, Cyp2d9, Cyp2j11, Cyp2j13, Cyp3a41a, Cyp3a59, Cyp4a12a, Cyp4a12b, Cyp4a31, Cyp4a32, Cyp4b1, Cyp4f13, Cyp4f16, Cyp4f18, Cyp4f37, Cyp4×1, Cyp7b1).

Isoforms of sulfotransferases involved in sulfur conjugation of a wide variety of chemicals had unique mouse strain SNP patterns (Sult2a3, Sult2a4, Sult2a8, Sult2b1, Sult5a1) (Gamage et al., 2006). There was also evidence of unique WSB SNP patterns for aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzymes involved in detoxification by oxidizing aldehydes to carboxylic acids (Aldh18a1, Aldh3b2, Aldh4a1, Aldh8a1). 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase (MTRR) an enzyme important for folate metabolism and cellular methylation was characterize with WSB SNPS patterns.

The lipoxygenase (LOX) gene family (Tomita et al., 2019) whose members encode enzymes that catalyze the addition of molecular oxygen to polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to yield fatty acid hydroperoxides that can lead to oxidative stress and DNA damage had unique WSB SNP patterns (Alox8, Alox8, Alox8, Alox8, Alox8, Alox8, Aloxe3). In addition, another gene involved in lipid metabolism (Mttp - microsomal triglyceride transfer protein) had unique WSB SNP patterns.

Many members of the solute carrier family of genes (SLCs) that regulate flow of substances across membranes were among those with unique WSB patterns (Supplement one). In addition, there were unique WSB patterns in protocadherin’s (PCDH) genes which code for proteins that mediate calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion, and in Mrgprb genes that are G protein coupled receptors thought to be involved in membrane function particularly in the brain (Supplement one).

There were distinct WSB Tmem SNP patterns (Tmem267, Tmem33, Tmem37, Tmem40, Tmem40, Tmem52b, Tmem67, Tmem70, Tmem80, Tmem86a). The transmembrane (TMEM) protein family are reported to be involved in the mechanisms leading to cancer cell dissemination such as migration and extra-cellular matrix remodeling (Marx et al., 2020). The MFSD family (major facilitator superfamily domain) are transmembrane proteins and sodium-dependent lysophosphatidylcholine transporters (Perland et al., 2017). Again, WSB specific patterns were noted in members of this family (Mfsd13b, Mfsd14b, Mfsd2a, Mfsd4a, Mfsd4b3-ps, Mfsd4b4, Mfsd4b5, Mfsd6, Mfsd8).

Other categories of gene families with unique WSB SNPs included the ATPase genes whose protein products are involved with transporting ions across cell membranes (Atp10b, Atp11b, Atp13a4, Atp13a5, Atp1b1, Atp2a3, Atp5h. Atp8b3, Atpaf2) and ABC transporters (including Abca, Abcb, Abcc). There were fifteen members of the Adam gene family that code for surface proteins with adhesion and protease activity that had unique WSB SNP patterns. There were five members of the subfamily of adhesion G protein coupled receptors (ADGRE) with unique WSB patterns.

3.8. Other unique WSB SNP patterns

Unique WSB SNP patterns were noted in gene families that govern a variety of other cell functions. This included Serpin family SNPs, protease inhibitors that are considered regulators for multitude of pathways, and Zinc Finger family genes (Zfp) that could be involved in in governing cell functions including DNA recognition, RNA packaging, transcriptional activation, regulation of apoptosis, protein folding and assembly, and lipid binding (Laity et al., 2001). WSB SNPs in the FAM group of genes also distinguished this mouse strain (Supplement one), some of which have roles in viral replication (Fine et al., 2012).

Other findings included unique WSB SNP patterns in Apolipid proteins (Apoa1, Apoa2, Apoa4, Apoa5); Ccm2l CCM2 like scaffold protein (Ccna1, Ccnh, Ccni, Ccnt1, Ccpg1, Ccr7, Ccs, Ccser1, Ccser2, Cct4, Cct8, Cct8l1); and Sprr2a3 small proline-rich proteins (Sprr2a3, Sprr2d, Sprr3, Sprr4). Collagen type gene members play a role during the calcification of cartilage and the transition of cartilage to bone and these genes also presented with unique WSB SNP patterns (Col11a2, Col13a1, Col14a1, Col16a1, Col19a1, Col22a1, Col26a1,Col27a1,Col28a,Col4a3, Col4a4, Col6a4, Col6a5, Col6a6, Colgalt2). There were many olfactory genes; vomeronasal genes (VNO); and zinc family protein genes with unique WSB SNP patterns (Supplement 1).

4. Discussion

The WSB/EiJ mouse strain had the lowest incidence of both benign and malignant tumors as determined after histopathologic examination of major organ systems (Figure 1). Males and females in this mouse strain had low body weights compared to those of other mouse strains, with a large percent of the animals surviving until the end of the study. These WSB/EiJ mouse strain body weight and survival characteristics confirm the strain characteristics previously described in other studies (Reed et al., 2007; Yuan et al., 2020).

We used the Sanger genome database (Keane et al., 2011) to identify the unique SNPs in the coding regions of the WSB mouse genome and found unique SNPs in cancer and cancer driver genes, mitochondria, metabolic, membrane, and immune function genes not found in the other strains with the higher incidences of cancer (Figure 2). This supports the hypothesis that cancer phenotypes are based in part on the genetics of multiple cell function genes (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011; Smith et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

Summary of Study Findings

SNP cancer gene patterns unique to the WSB mouse included those for oncogenes/protooncogenes (e.g. ROS proto-oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase, Cbl proto-oncogene, MYCL proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor HRas protooncogene, GTPase, FAT1 FAT atypical cadherin 1, MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase); tumor suppressor genes (TSC2 TSC complex subunit 2 WIF - WNT inhibitory factor 1, FAT1 FAT atypical cadherin 1, MEN1 menin 1), and the kinases and transferases that take part in post-translation modifications (Fabbro et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2015) (e.g. CDK4 cyclin dependent kinase 4, JAK3 Janus kinase 3, MAP3K1 - mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1, KAT6B lysine acetyltransferase 6B).

Mitochondria energy fuels protein building, cancer development, and immune system function. As animals age the capacity for energy production diminishes, and in addition gene mutations that decrease mitochondria capacity may accumulate (McGuire, 2019; Mercken et al., 2017; Zong et al., 2016). Thus, WSB SNP specific patterns in mitochondria genes could be one set of factors that contribute to the observed differences in cancer incidence in the ten strains examined.

Unique WSB gene SNP patterns were found for immune function genes. This included unique WSB SNPs in Toll receptors which take part in activating the innate immune system (e.g. activation of macrophages), and in the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable regions, whose proteins are involved in adaptive immunity. Unique WSB SNP patterns also occurred in chemokines that regulate immune function and inflammation. These unique WSB SNP patterns support the hypothesis that the state of immune system is a critical factor in governing susceptibility or resistance to cancer (Fouad and Aanei, 2017; Smith et al., 2016). Other studies report that inherited genetic variants which can account for up to 87% of the variance of immune function (Orrù et al., 2013).

A robust immune system can contribute to resistance to the development of liver (Foerster et al., 2018; Sachdeva et al., 2015) and lung tumors (Hong et al., 2019), common tumors in both mice and humans, and the WSB strain in this study had a much lower incidence of both liver and lung cancer than the other mouse strains.

Metabolic and membrane function (Almasi and El Hiani, 2020) may be changed in cancer to create an environment favorable to cell growth and cancer, and in this study both metabolic and membrane function genes had unique SNP patterns in the coding regions in the WSB mouse genome.

Studies in twins show that inherited characteristics are important, but not the only factor in the development of cancer (Lichtenstein et al., 2000; Mucci et al., 2016). Environmental exposures can be the tipping point as to whether cancer will develop given a particular genetic background (Kerminen et al., 2019; Vermeulen et al., 2020). Current uncertainty factor paradigms used in chemical risk assessment in one rodent strain may not be sufficient for determining the broad spectrum of mammalian diversity in disease response. The very young and older mammals may both represent vulnerable populations for which age is a critical factor for development of disease. As we study effects of environmental exposures on disease onset or progression, a broader use of models representative of mammalian diversity may more closely mimic the spectrum of human disease susceptibility. Thus, follow-up studies to determine how the environment and genetic background work together to affect disease development in mouse models strains with different genetic background is warranted.

5. Conclusion

In this study we report that the WSB strain, the strain with a low incidence of all types of cancers, had unique SNP patterns in the coding regions of genes associated with multiple cell functions. This is consistent with the observation that inheritance patterns can affect the occurrence of specific diseases, and genome-wide association studies (GWA study, or GWAS) which demonstrate that disease in mammals is in part dependent on inherited genetic characteristics which has occurred over time as populations adapt to their environment. The unique SNP patterns in a cancer resistant mouse strain, may be used to further understand and develop strategies for cancer prevention.

Supplementary Material

Financial Support

The NIEHS intramural programs supported this work (ZIA ES103349–01)…. Bioinformatics support was from Sciome, LLC supported via Contract Number HHSN273201700001C. We thank Dr. J. Bucher and Dr. S. Ferguson, NIEHS, for their review of the manuscript. However, the statements, opinions or conclusions contained therein do not necessarily represent the statements, opinions, or conclusions of NIEHS, NIH or the United States government.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

Supplemental 1 (All-Ensembl-Transcript-Codons.xlsx): SNP descriptors along with

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akdis M, et al. , 2011. Interleukins, from 1 to 37, and interferon-γ: Receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 127, 701–721.e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasi S, El Hiani Y, 2020. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Membrane Transport Proteins: Focus on Cancer and Chemoresistance. Cancers (Basel). 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer AJ, Portier CJ, 1988. Effects of treatment-induced mortality and tumor-induced mortality on tests for carcinogenicity in small samples. Biometrics. 44, 417–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MH, et al. , 2018. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell. 174, 1034–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogue MA, et al. , 2016. Accessing Data Resources in the Mouse Phenome Database for Genetic Analysis of Murine Life Span and Health Span. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 71, 170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, et al. , 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 30, 2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boorman GA, et al. , Quality assurance in pathology for rodent carcinogenicity testing. In: Millman H, Weisburger E, Eds.), Handbook of Carcinogen Testing. Noyes Publishing, Park Ridge, NJ, 1985, pp. 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Broad Institute, 2021. (accessed). Picard. https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill GA, et al. , 2012. The Diversity Outbred mouse population. Mamm Genome. 23, 713–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbro D, et al. , 2015. Ten things you should know about protein kinases: IUPHAR Review 14. Br J Pharmacol. 172, 2675–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, et al. , 2015. Metabolic regulation of histone post-translational modifications. ACS Chem Biol. 10, 95–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FastQC, 2021. (accessed). https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. [Google Scholar]

- Fine DA, et al. , 2012. Identification of FAM111A as an SV40 host range restriction and adenovirus helper factor. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerster F, et al. , 2018. The immune contexture of hepatocellular carcinoma predicts clinical outcome. Sci Rep. 8, 5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouad YA, Aanei C, 2017. Revisiting the hallmarks of cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 7, 1016–1036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamage N, et al. , 2006. Human sulfotransferases and their role in chemical metabolism. Toxicol Sci. 90, 5–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm SA, et al. , 2019. DNA methylation in mice is influenced by genetics as well as sex and life experience. Nat Commun. 10, 305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J, et al. , 2017. Antigen Processing in the Endoplasmic Reticulum Is Monitored by SemiInvariant αβ TCRs Specific for a Conserved Peptide-Qa-1(b) MHC Class Ib Ligand. J Immunol. 198, 2017–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guénet JL, 2005. The mouse genome. Genome Res. 15, 1729–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 144, 646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna K, et al. , 2019. Colon cancer in the young: contributing factors and short-term surgical outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H, et al. , 2019. Aging, Cancer and Immunity. J Cancer. 10, 3021–3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, et al. , 2020. Abnormal Expression of Mitochondrial Ribosomal Proteins and Their Encoding Genes with Cell Apoptosis and Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter KW, et al. , 2018. Genetic insights into the morass of metastatic heterogeneity. Nat Rev Cancer. 18, 211–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, et al. , 2011. Mouse genomic variation and its effect on phenotypes and gene regulation. Nature. 477, 289–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerminen S, et al. , 2019. Geographic Variation and Bias in the Polygenic Scores of Complex Diseases and Traits in Finland. Am J Hum Genet. 104, 1169–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laity JH, et al. , 2001. Zinc finger proteins: new insights into structural and functional diversity. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 11, 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R, 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25, 1754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, et al. , 2000. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer-analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 343, 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TR, et al. , 2020. Targeting innate immunity by blocking CD14: Novel approach to control inflammation and organ dysfunction in COVID-19 illness. EBioMedicine. 57, 102836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx S, et al. , 2020. Transmembrane (TMEM) protein family members: Poorly characterized even if essential for the metastatic process. Semin Cancer Biol. 60, 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire PJ, 2019. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and the Aging Immune System. Biology (Basel). 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, et al. , 2010. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercken EM, et al. , 2017. Conserved and species-specific molecular denominators in mammalian skeletal muscle aging. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 3, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modjtahedi N, et al. , 2016. Mitochondrial Proteins Containing Coiled-Coil-Helix-Coiled-Coil-Helix (CHCH) Domains in Health and Disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 41, 245–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucci LA, et al. , 2016. Familial Risk and Heritability of Cancer Among Twins in Nordic Countries. Jama. 315, 68–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrù V, et al. , 2013. Genetic variants regulating immune cell levels in health and disease. Cell. 155, 242–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozato K, et al. , 2008. TRIM family proteins and their emerging roles in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 8, 849–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perland E, et al. , 2017. Structural prediction of two novel human atypical SLC transporters, MFSD4A and MFSD9, and their neuroanatomical distribution in mice. PLoS One. 12, e0186325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkov PM, et al. , 2004. An efficient SNP system for mouse genome scanning and elucidating strain relationships. Genome Res. 14, 1806–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piegorsch W, Bailor AJ, Statistics for environmental biology and toxicology. Chapman and Hall, London, U. K., 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Portier CJ, Bailer AJ, 1989. Testing for increased carcinogenicity using a survival-adjusted quantal response test. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 12, 731–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman J, Rahman S, 2018. Mitochondrial medicine in the omics era. Lancet. 391, 2560–2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed DR, et al. , 2007. Forty mouse strain survey of body composition. Physiol Behav. 91, 593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, et al. , 2007. The polymorphism architecture of mouse genetic resources elucidated using genome-wide resequencing data: implications for QTL discovery and systems genetics. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 18, 473–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva M, et al. , 2015. Immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 7, 2080–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler S, et al. , 2012. Evolution of the C-type lectin-like receptor genes of the DECTIN-1 cluster in the NK gene complex. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012, 931386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MT, et al. , 2016. Key Characteristics of Carcinogens as a Basis for Organizing Data on Mechanisms of Carcinogenesis. Environ Health Perspect. 124, 713–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, et al. , 2020. Innate-adaptive immunity interplay and redox regulation in immune response. Redox Biol. 37, 101759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate JG, et al. , 2019. COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D941–d947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PD, Kejariwal A, 2004. Coding single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with complex vs. Mendelian disease: evolutionary evidence for differences in molecular effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101, 15398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita K, et al. , 2019. Lipid peroxidation increases hydrogen peroxide permeability leading to cell death in cancer cell lines that lack mtDNA. Cancer Sci. 110, 2856–2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen R, et al. , 2020. The exposome and health: Where chemistry meets biology. Science. 367, 392–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellcome Sanger Institute, 2020. (accessed). Mouse Genomes Project - Query SNPs, indels or SVs. https://www.sanger.ac.uk/sanger/Mouse_SnpViewer/rel-1505. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh CE, et al. , 2012. Status and access to the Collaborative Cross population. Mamm Genome. 23, 706–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik GL, et al. , 2019. Genetic analyses of diverse populations improves discovery for complex traits. Nature. 570, 514–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, et al. , 2020. Comprehensive molecular characterization of mitochondrial genomes in human cancers. Nature Genetics. 52, 342–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zola H, et al. , 2007. CD molecules 2006--human cell differentiation molecules. J Immunol Methods. 319, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong WX, et al. , 2016. Mitochondria and Cancer. Mol Cell. 61, 667–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.