Abstract

Falls are the leading cause of injury and hospitalization for older adults in Canada and the second leading cause of unintentional injury deaths worldwide. For people living with dementia (PLWD), falls have an even greater impact, but the standard testing methods for fall risk screening and assessment are often not practical for this population. The purpose of this scoping review is to identify and summarize recent research, practice guidelines and gray literature which have considered fall risk screening and assessment for PLWD. Database search results revealed a dearth in the literature that can support researchers and healthcare providers when considering which option/s are the most suitable for PLWD. Further primary studies into the validity of using the various tests with PLWD are needed if researchers and healthcare providers are to be empowered via the literature and clinical practice guidelines to provide the best possible fall risk care for PLWD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, dementia, falls, screening, assessment, geriatrics

What this paper adds

• This review summarizes recent literature on fall risk screening and assessment for people living with dementia.

• This review highlights the limited research on fall risk screening and assessment for people living with dementia.

Applications of study findings

• Increased knowledge in this area will support researchers and healthcare providers when considering fall risk screening and assessment for people living with dementia.

• The findings of this review highlight the need for further primary research into appropriate methods of fall risk screening and assessment for people living with dementia.

Introduction

Falls in the older adult population are a major concern for older adults, their families, and the healthcare system. One in three older adults over the age of 65 years is likely to fall at least once per year (Pearson et al., 2014). Falls are the leading cause of injury and hospitalization for older adults in the United States and Canada (National Council on Aging, 2022; Parachute Canada, 2021), and the second leading cause of unintentional injury deaths worldwide (World Health Organization, 2016). Even if they are non-injurious, falls can result in a cascade of fear of falling, reduced mobility, and increased reliance on caregivers (Lindt et al., 2020). Falls also increase the likelihood of a transition away from independent living into long-term care (Gilbert et al., 2010; Okoye et al., 2023). There are also considerable economic costs involved in the management of older adults who have experienced falls. In 2021, this was calculated to be $5.6 billion CA dollars annually across the Canadian healthcare system (Parachute Canada, 2021) and in 2018 this figure was $50 billion US dollars in the United States (Florence et al., 2018).

For people living with dementia (PLWD), falls have an even greater impact, on the PLWD, their caregivers and the healthcare system. PLWD are at a much higher risk of falling than the general older adult population with an annual fall rate of 60–80% compared to approximately 30% in the general older adult community-dwelling population (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018). In Canada, 15% of emergency department (ED) visits by PLWD are fall-related, compared to 9% among older adults who do not have cognitive impairment (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014; Ryan et al., 2011). In the United States, LaMantia et al. (2016) found that PLWD visited the ED more often, were hospitalized more often, and had more chance of returning to the ED within 30 days than people who did not have a dementia diagnosis.

Dementia terminology does not refer to a distinct malady but can be defined as “a set of symptoms and signs associated with a progressive deterioration of cognitive functions that affects daily activities” (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017). Alzheimer's disease is the most common form encountered, being responsible for 60–80% of dementia cases (Alzheimer’s Association, 2022). Dementia primarily affects older adults over 65 years of age, but it is also present in the form of Young-Onset dementia (0.07% of cases) which affects adults younger than 65 years (Hendriks et al., 2021). There are currently over 500,000 PLWD in Canada and more than 76,000 people are being diagnosed each year. By 2031, the number of PLWD in Canada is projected to be at least 937,000 (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2016; Mesbah et al., 2017).

There are standard practices and guidelines for conducting fall risk screening and assessment for older adults (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013; Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2017). The process of conducting fall risk “screening” and “assessment” comprises two separate elements. Screening is a quick evaluation to establish risk based on primary fall risk factors such as previous falls, balance, and walking difficulties (Drootin, 2010). Assessment is the method by which a more comprehensive evaluation of several fall risk factors is conducted often by more than one healthcare provider (Williams-Roberts et al., 2020). To better understand the risks involved and to reduce the personal and monetary costs of falls, there has been extensive research on fall risk assessment and intervention measures for the general older adult population, with fall injury prevention being recognized as a global health priority (World Health Organisation, 2015).

Most of the clinical practice recommendations for identifying fall risk have been based on trials which, either systematically or unintentionally, excluded older adults with cognitive impairment (Dolatabadi et al., 2018; Lim et al., 2017; Montero-Odasso & Speechley, 2017). As a result, the standard testing methods for fall risk screening and assessment are often not practical for PLWD. They may have difficulty understanding the task, be unable to focus on the task or even be unwilling to cooperate, which may manifest in a spectrum of responses from passive resistance to aggressive behaviors (McGough et al., 2013). A deeper understanding of the current screening and assessment tools, and the recommendations from the literature, is therefore important. Increased knowledge in this area will enable the development of more personalized and therefore, more effective approaches to fall risk screening and assessment for PLWD.

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify and summarize recent (in the past 10 years) research, practice guidelines and gray literature which have considered fall risk screening and assessment for PLWD. It was not intended to quantify or systematically review the articles included in individual reviews, but to conduct a search which will allow the review of the most current guidelines and recommendations healthcare providers have access to in order to make clinical decisions. The scoping review will help to inform PLWD, caregivers and healthcare professionals to better understand evidence-based screening and assessment tools that may be appropriate for use with PLWD, and if other bespoke tools have been developed and evaluated, which may be available for use by healthcare workers across the continuum of care.

Methodology

Search Strategy

An extensive search strategy was developed and actualized by the lead author in consultation with the research team and a specialist health sciences librarian. Six electronic databases were searched, namely, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Embase (Excerpta Medica Database), Medline, Epistemonikos, PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database), and TRIP (Turning Research Into Practice). In addition, an extensive gray literature search was conducted to capture the wide range of materials produced by relevant global organizations, charities, and governmental departments. This was conducted by using key words in internet search engines and by utilizing the knowledge of the experienced research team. Gray literature publications for consideration were obtained from bodies such as the Alzheimer Society of Canada, Alzheimer’s Association, Lewy Body Dementia Canada, Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, Canadian Seniors Association, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Csomay Center for Gerontological Excellence, Public Health Agency of Canada, National Ageing Research Institute, Health Innovation Network, Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, American Geriatrics Society, Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre, and the American Psychiatric Association.

The search strategy followed the guidelines issued by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Aromataris & Riitano, 2014; Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015). Filters were put in place to only include material published in a 10-year period between 2012 and 2022. Key words pertaining to the research aims were used, combined with Boolean operators (EBSCO Connect, 2022), to search for suitable papers. The search strategy was developed to be as comprehensive as the individual database search engines allowed. A complete list of the search terms used can be found in the supplemental information. Results were then collated to produce a portfolio of relevant publications which could be brought forward into the primary selection stage.

Selection Strategy

The lead author utilized the selection criteria below in the initial screening of peer-reviewed paper titles and abstracts to determine eligibility. A gray literature search was also conducted at this stage, for documents such as clinical practice guidelines which contained information regarding fall risk assessment for PLWD.

Publications were excluded if they (1) pertained to non-accidental falls; (2) focused on the treatment of an injury following a fall; (3) focused on fall prevention, aftercare or interventions; (4) pertained to new technology development for measurements such as gait speed; (5) related to the use of fall risk as a tool to diagnose dementia; (6) were books, theses, dissertations, or conference proceedings; (7) were not accessible in full text format.

Publications were included if they (1) considered people of any age living with a recognized form of dementia; (2) considered the screening and/or assessment of fall risk; (3) considered any form of care setting, that is, Community, Acute and Long-Term Care; (4) were published between 2012 and 2022; (5) were published in the English language. Although not included specifically in the database search parameters, a selection of papers identified through further investigation of related literature (linked to the eligible list of publications), were included which related to Fear of Falling due to their inclusion in some fall risk screening tools.

Once the initial screening had taken place, any duplicates were removed using the Mendeley Reference Manager software (Mendeley Ltd., 2022) and the abstracts of the papers carried forward were reviewed by the lead author for the next stage of screening. These abstracts were then also jointly reviewed by both authors simultaneously, with discussion allowing consensus to be reached on which papers should be included for the next stage. This next stage involved the lead author obtaining and reviewing the full texts of the selected papers. Following thorough analysis of the full texts, any which were not considered wholly pertinent to the aim of the scoping review were removed.

Results

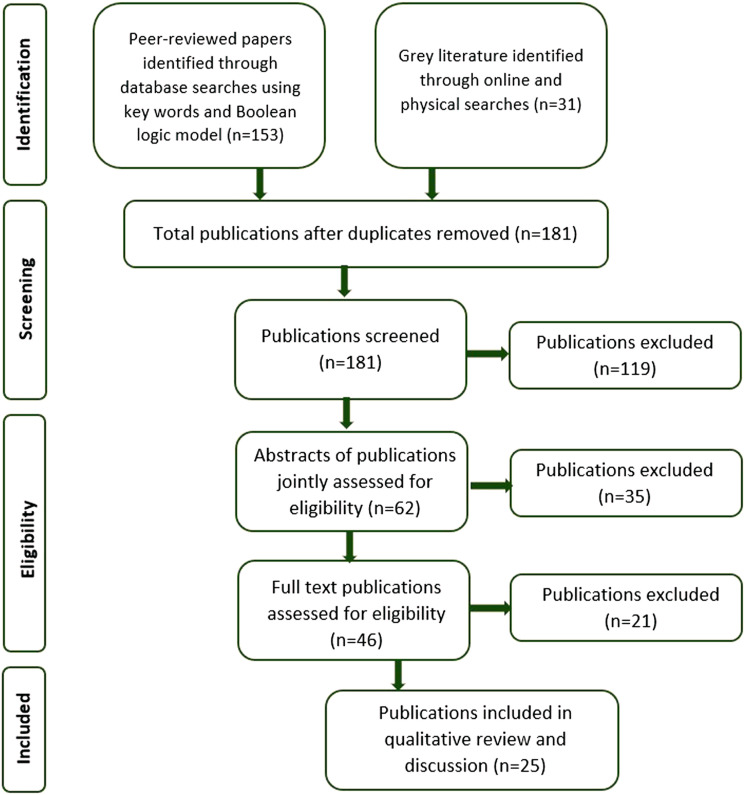

The initial search revealed 184 non-duplicated publications, which were composed of 153 peer-reviewed papers and 31 pieces of gray literature. Duplicates accounted for three of these and so were removed to leave 181 for the initial screen. Following this initial screen, 62 abstracts were subject to joint review by both authors, with 36 of the peer-reviewed papers being progressed to the next stage, along with 10 pieces of gray literature. Following review of the full texts of this material, 25 publications (20 peer-reviewed papers and five pieces of gray literature) were carried through to the final stage for discussion. A graphic of this process can be found in Figure 1 and the final selected publications can be found listed in the first column of Table 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the search and selection process for included publications.

Table 1.

Overview of Selected Publications and Included Tests.

| Country of Origin | Category of Research | Care Setting | Balance Test/s | Gait Test/s | Dual Task Test/s | Fear Test/s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ansai et al. (2019) | Brazil | PR | COM | ||||

| BC (2021) | Canada | CPG | COM | ||||

| Buttery et al. (2017) | UK | GL | COM | ||||

| Cox & Vassallo (2015) | UK | LR | PAN | ||||

| Delbaere et al. (2013) | Australia | PR | COM | ||||

| Dolatabadi et al. (2018) | Canada | SYR | PAN | ||||

| Fernando et al. (2017) | Canada | SYR | PAN | ||||

| Fischer et al. (2014) | USA | PR | COM | ||||

| Lach et al. (2017) | USA/Thailand | LR | PAN | ||||

| McGough et al. (2013) | USA | PR | COM | ||||

| Mesbah et al. (2017) | NZ/Australia | SYR | PAN | ||||

| Modarresi et al. (2019) | Canada | SYR | PAN | ||||

| Montero-Odasso et al. (2012) | Canada | PR | COM | ||||

| Montero-Odasso & Speechley (2017) | Canada | LR | PAN | ||||

| Muir et al. (2012) | Canada | PR | COM | ||||

| PHAC (2014) | Canada | GL | PAN | ||||

| Renfro et al. (2016) | USA | LR | PAN | ||||

| RNAO (2017) | Canada | CPG | PAN | ||||

| SFPC (2017) | Canada | CPG | COM | ||||

| Taylor et al. (2012) | Australia | LR | PAN | ||||

| Trautwein et al. (2019) | Germany | SYR | PAN | ||||

| Uemora et al. (2015) | Japan | PR | COM | ||||

| Van Ooteghem et al. (2019) | Canada | SR | PAN | ||||

| Whitney et al. (2012) | UK/Australia | PR | LTC | ||||

| Zhang et al. (2019) | Australia/Germany | LR | PAN |

KEY: BC = British Columbia Ministry of Health; PHAC = Public Health Agency of Canada; RNAO = Registered Nurses Association of Ontario; SFPC = Saskatoon Falls Prevention Consortium; PR = primary research; SR = scoping review; SYR = systematic review; CPG = clinical practice guideline; LR = literature review; GL = gray literature; COM = community; LTC = long-term care; AC = acute; PAN = panoptic.

Frequency analysis was first conducted on the 25 publications to understand the research landscape, which showed that 44% (n = 11) of the publications originated from Canada, with 8% (n = 2) from the United Kingdom and 12% (n = 3) from the United States. The other publications were from Australia, Germany, Brazil, Japan, New Zealand, Thailand, and multi-country partnerships. The modes of research were found to be varied comprising of 32% (n = 8) primary research, 24% (n = 6) literature reviews, 20% (n = 5) systematic reviews, 12% (n = 3) clinical practice guidelines, 8% (n = 2) gray literature, and 4% (n = 1) scoping reviews. The care settings of the publications were primarily panoptic in their approach with 56% (n = 14) reflecting a broad approach. A community setting accounted for 40% (n = 10) and long-term care 4% (n = 1). None of the publications focused solely on acute care settings.

The eligible publications were entered into the NVivo v.12 software (QSR International, 2018) in order to categorize the findings of screening and fall risk assessments, demographic information and other relevant data and comments. Within the selected publications, five tools were identified which included screening for fall risk, and a total of 23 individual tests relating to fall risk assessment. These 23 fall risk assessment tests were then categorized into five groups for review. The five groups and the tests allotted to each can be found in Table 2. The distribution of these groups across each of the final selected publications was then explored, and the results of this can be found by referring back to Table 1. A summary of the five screening and assessment tools, and the five groups of fall risk assessment tests identified in this review are described below.

Table 2.

Grouping of Fall Risk Assessment Tools.

| Balance/Functional Mobility Tools | Gait Tools | Dual Task Tools | Combination Tools | Fear Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berg Balance Scale | 10 meter walk | Dual tasking | POMA (Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment) | FES (Falls Efficacy Scale) |

| BESTest (Balance Evaluation System Test) | 6-minute walk | TUG (Timed Up & Go)-cognition | FES-I (Falls Efficacy Scale-International) | |

| Functional reach | DGI (Dynamic Gait Index) | TUG (Timed Up & Go)-manual | Icon-FES (Iconographical Falls Efficacy Scale) | |

| Mod-Berg (Modified Berg Balance Scale) | FGI (Functional Gait Index) | |||

| Postural sway | Gait speed | |||

| Sit-stand | GMWT (Groningen Meander Walking Test) | |||

| TUG (Timed Up & Go) | Stride length | |||

| SPPB (Short Physical Performance Battery) |

Multifactor Fall Risk Screening and/or Assessment Tools

Five tools which included both fall risk screening and assessment were reported and considered in the publications included in this review: STEADI (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries), FRAST (Fall Risk Assessment Screening Tool), FROP-Com (Falls Risk for Older People in the Community), the American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention of Falls in Older Persons and CaHFRiS (Care Home Falls Screen).

The STEADI tool (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017) is composed of three stages, a screen by way of a self-administered questionnaire, followed by a fall risk assessment (if necessary) and then interventions. The fall risk assessment stage does not make any recommendations for which tool to use but offers the Timed Up & Go (TUG), 30-Second Chair Stand and the 4-Stage Balance Test as “common ways” to proceed. The STEADI tool was considered in one publication (Renfro et al., 2016) who describe it as “the most widely disseminated fall risk screening tool” (Renfro et al., 2016, p. 3), although they note that it does not consider psychosocial issues, such as fear of falling, and therefore recommend that additional tools should be used in conjunction with STEADI. The STEADI tool makes no reference to adaptions or considerations when being used with PLWD.

The FRAST tool (Renfro & Fehrer, 2011) is referenced in one publication, Renfro et al. (2016). Like the STEADI tool, the FRAST tool comprises a three-part structure (screening, fall risk assessment and interventions), utilizing a self-administered questionnaire for the screening. It differs in that the questionnaire also incorporates the modified Falls Efficacy Scale (mFES) to measure fear of falling. The FRAST tool also specifies that the TUG test is to be used for the fall assessment stage. The inclusion of the psychosocial elements offers a more robust screening tool for older adult high fall risk populations (Renfro et al., 2016) but as it did not specifically consider PLWD in its initial design and validation (Renfro & Fehrer, 2011) further research is needed.

The FROP-com tool (National Aging Research Institute, 2022) is a two-stage screening and assessment tool, both parts of which are administered by a health professional. The FROP-com is one of two tools recommended by the Saskatoon Falls Prevention Consortium (2017) due to its capacity to score and classify “low to high” fall risk, enabling more individualized monitoring and intervention. The screening includes a measure of independence in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and the fall risk assessment includes both cognitive status and functional behavior in its scoring system.

The American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention of Falls in Older Persons (Drootin, 2010) is an alternative two-stage screening and assessment tool. The screening stage is short, simple, and applicable to all populations, with the advantage that it can be conducted by both trained healthcare providers and caregivers. The fall risk assessment stage must be conducted by a healthcare professional and includes both cognitive and functional considerations to guide interventions, but it does not offer a scoring system.

The CaHFRiS tool (Whitney et al., 2012) focuses solely on the screening stage of fall risk and has “excellent discrimination with respect to quantifying the probability with which a care home resident will fall over a 6-month period, with absolute risk of falling ranging from zero in those with no risk factors to 100% in those with six or more risk factors” (Whitney et al., 2012, p. 693). However, the authors acknowledge that additional validation is required. Although the screening tool was not designed specifically for PLWD, 89% of the residents who participated in the development study had a measurable degree of cognitive impairment.

Balance/Functional Mobility Tests

Of the 27 publications analyzed in this review, 22 considered balance or balance-related functional mobility tests for fall risk assessment, with the Timed Up & Go (TUG) test being the most frequent (n = 10). The TUG test is a timed test of standing up from a chair, walking three meters, turning, walking back to a chair and sitting. This test adds components of mobility, strength, walking and balance. (Podsiadlo & Richardson, 1991). Whilst arguably the most well-established of the functional mobility fall risk tests, having been developed over 30 years ago by Podsiadlo and Richardson (1991), authors varied in their findings of its potential use for PLWD. Buttery et al. (2017) recommend it for PLWD, Trautwein et al. (2019) recommend it as a motor assessment, and Uemora et al. (2015) used the test in their studies with no reported issues. Fischer et al. (2014) found that the TUG test was reasonably effective and Ansai et al. (2019) found a significant association between falls and the “turn-to-sit” phase, but not for the test as a whole. Dolatabadi et al. (2018) found a similar split of opinion, with two studies recommending the TUG test and two studies finding it ineffective. However, Modarresi et al. (2019) found that all the studies in their review stated they did not recommend the use of the TUG test to predict falls in PLWD.

The Postural Sway test was indicated as a successful predictor of falls for PLWD in Dolotabadi et al. (2018), Fischer et al. (2014) and Mesbah et al. (2017). However, it relies on technology and training which may not be available in all assessment facilities, thus potentially impacting its widespread clinical use. The Physiological Profile Assessment (PPA) is a combination fall risk assessment which includes Postural Sway as an element along with vision, sensation, muscle force and reaction time. Due to the complexities of the other aspects of the PPA test, it is not recommended for PLWD (Van Ooteghem et al., 2019).

The Berg Balance Scale and the Modified Berg Balance Scale (Mod-Berg) have both been reported to have potential for use with PLWD. The Berg Balance Scale, a 5-point rating scale functional balance assessment of 14 tasks, has been used extensively in clinical practice since its development and has been subject to a corresponding level of research, which has found it to be a reliable and recommended measure of balance across a wide range of populations (Renfro et al., 2016; Trautwein et al., 2019). It has been validated in individuals with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease but minimally in other dementias, particularly at moderate to severe levels and so further research is required in this area (McGough et al., 2013; Mesbah et al., 2017). The Mod-Berg is a modification of the Berg Balance Scale which was designed to predict the transfer of older adults to long-term nursing care facilities and was utilized in the work of McGough et al. (2013), who saw the possibility for it to be also used as a predictor of balance impairment in PLWD. It was found that individuals who were involved in a fall event over the 4 month study were those with lower Mod-Berg scores, supporting its use as a tool for fall risk assessment for PLWD (McGough et al., 2013). However, this study only considered PLWD in an assisted living facility and so further validation work is required within other care settings.

The Balance Evaluation System Test (BESTest) has been shown to demonstrate high reliability for fall risk in a wide range of populations, with the developers describing it as “the most comprehensive clinical balance tool available” (Horak et al., 2009, p. 484) due to the inclusion of assessment of all systems contributing to postural stability. The BESTest was reviewed positively by Renfro et al. (2016) with regards to its use in older adult high-risk populations, but further work should be carried out to validate its use specifically for PLWD.

The Functional Reach test and the Sit-Stand test are two of the simpler tests, both of which are recommended as functional balance mobility assessments by Trautwein et al. (2019) following their systematic review, with Mesbah et al. (2017) finding that the postural stability of a PLWD in the Functional Reach test was significantly reduced when compared to healthy older adults.

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) is a balance and walking test which also includes an element of lower leg strength. It has not been researched extensively for use with PLWD but is a simple and brief test and was used successfully with older adults living with moderate to severe dementia by McGough et al. (2013). The Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA) is commonly used in clinical settings and has been established as a reliable and valid tool in older adult populations with no co-morbidities (Renfro et al., 2016). The POMA consists of 16 tasks to assess musculoskeletal function, balance, gait, and postural stability which enhances its validity, but it is this comprehensiveness which creates challenges when used with PLWD, as the results are strongly related to how well the participant understands the instructions (Mezbah et al., 2017; Modarresi et al., 2019). Modarresi et al. (2019) found that none of their reviewed studies which used POMA recommended its use for PLWD and Van Ooteghem et al. (2019) concluded that it was “not feasible” in this population.

Gait Tests

Of the 27 publications analyzed in this review, 22 considered gait tests for fall risk assessment, with Gait Speed (n = 5) and Stride Length (n = 3) being the most frequently studied. Gait speed has been shown to be a valid and reliable predictor of fall risk in high-risk older adult populations, including PLWD (Dolatabadi et al., 2018; Lach et al., 2017; Muir et al., 2012; Renfro et al., 2016; Uemora et al., 2015). Stride length has also been shown to be an effective measure when determining fallers from non-fallers in PLWD, particularly the variability of the stride length which offers a more conclusive measure; being greater in fallers than non-fallers (Dolatabadi et al., 2018; McGough et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2012).

The Dynamic Gait Index (DGI) is one of the more complex gait assessments and has been evaluated in numerous populations with excellent reliability (Renfro et al., 2016) but it contains several elements with multiple levels of instruction, which a PLWD may not be able to understand or perform, such as walking around obstacles and performing complex motor tasks. A modification of the DGI, the Functional Gait Index (FGI) removes walking around obstacles but augments it with additional straight-line measures in the form of narrow-base, backwards and eyes-closed gait exercises. These changes were made to remove the “ceiling effect” of measures found in the DGI for healthy older adults (Renfro et al., 2016). As such, by increasing the difficulty level of the tasks, the FGI is likely to be even less appropriate than the DGI for PLWD.

Two walking tests were considered within the selected publications, the 10-meter Walk and the 6-minute Walk. The 10-meter Walk test was utilized by Ansai et al. (2019) who found significant association with falls in both the mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease sample groups. It has been successfully applied to a wide range of demographics giving reliable results, although there has been some variability in the research between relevant gait speeds and fall risk within the test. Because of this, Renfro et al. (2016) suggest that the 10-meter Walk test should be conducted twice using two different gait speeds to ensure validity. The 6-minute Walk is one of several tests recommended by Trautwein et al. (2019) as mobility assessments, who note that it can be used to assess endurance levels with high reliability. Whilst arguably not a fall risk assessment in the strictest sense, for those PLWD who are still able to concentrate on a motor task for 6 minutes, it could be a good indicator of their physical limits, which in turn can help to inform what degree of exercise they can tolerate.

The Groningen Meander Walking Test (GMWT) is a motor assessment tool developed as a walking test for use specifically with PLWD. Trautwein et al. (2019) recommend it as a mobility assessment tool and given that the GMWT was developed with PLWD in mind, further research to confirm its validity as a fall risk assessment tool would be very valuable.

Dual Task Tests

Of the 27 publications analyzed in this review, 15 considered Dual Task tests for fall risk assessment. For fall risk assessment purposes, Dual Tasking usually involves some form of motor measurement, such as gait speed or gait variability, along with a cognitive measurement such as counting out loud or naming animals. Ambulation has long been viewed as automatic, but it also relies on cognitive interaction and control (Monterro-Odasso et al., 2012). Given the effects of dementia on cognitive function and motor skills, the use of Dual Tasking for fall risk assessment appears to have potential for helping to identify fall risk in PLWD (Lach et al., 2017; Modarresi et al., 2019; Montero-Odasso et al., 2012; Monterro-Odasso & Speechley, 2017; Muir et al., 2012; Renfro et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2019). Dual Tasking also imitates Activities of Daily Living (ADL), when the PLWD is highly likely to employ both motor and cognitive skills at the same time, dividing their attention. Two publications note that common ADL aimed at preventing falls may contribute to the fall risk if the PLWD cannot safely divide their attention. For example, the use of a walking aid requires the PLWD to divide their attention between moving both the equipment and themselves (Fernando et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). Adverse changes in gait, particularly gait variability and gait velocity, were related to the difficulty level of the cognitive task (Montero-Odasso et al., 2012; Muir et al., 2012) as Dual Tasking constitutes a “brain stress test” (Montero-Odasso & Speechley, 2017, p. 369). This concept is supported by Muir et al. (2012) who encourage the use of less rhythmic cognitive tasks to further distinguish between the two tasks, and both Renfro et al. (2016) and Taylor et al. (2012) found that an additional cognitive task increased the validity of other tests.

Dual Task tests are also components of two modifications of the Timed Up & Go (TUG) test, the TUG-Cognition, and the TUG-Manual. The TUG-Cognition has shown potential to be particularly useful for PLWD (Fischer et al., 2014). The individual is required to perform the standard TUG test whilst performing a cognitive test, for example, count backwards from 50 at the same time. It has demonstrated strong correlations between measures and has also successfully distinguished between “never/single fallers” and “multiple fallers” (Fischer et al., 2014). The authors note however that the sample group were all male ex-veterans, so the results may not be representative of a larger population, meaning further research is required. In the TUG-Manual test, the participant is required to carry out the standard TUG whilst performing another motor action at the same time, for example, carry a non-breakable vessel containing water with no spillages. There has been cross-over in the literature between the TUG-Cognition and TUG-Manual as some, such as Renfro et al. (2016), have referred to a “Dual Task TUG” which encompasses cognitive and/or motor tasks with the TUG test. A significant association with falls was found by Ansai et al. (2019) when using the standard TUG test with the secondary task of dialing a telephone number, as the execution of this task involves both cognitive and motor skills.

Fear of Falls Tests

Of the 27 publications analyzed in this review, 10 considered Fear of Falling (FoF) in the context of fall risk assessment. Three tests relating to FoF were identified, the Falls Efficacy Scale (FES) and two variations of this test. The FES is a measurement of perceived fear of falling, based on a short, self-administered questionnaire which asks how confident the person is in doing a task. It is one of the most widely used of the FoF tools and has been studied with a wide range of populations (Renfro et al., 2016). However, it is founded on self-administration; thus its reliability may be uncertain when applied to PLWD, who may be unable to complete the questions themselves or may even have a significantly reduced concept of fear (Cox & Vassallo, 2015). The Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I) built on the FES to include 16 questions with more social-based elements and is therefore considered to be a more reliable tool (Renfro et al., 2016). However, as with the FES it shares the same challenges of relying on a self-administered questionnaire. The Iconographical Falls Efficacy Scale (Icon-FES) was developed to further enhance the fear of falling assessment by including pictures to provide participants with some context when they are considering their answers. For example, it is reasonable to suppose that a person’s response to whether they feel confident walking outside or not may differ depending on whether it is sunny and dry or overcast and raining. Dementia was a participant exclusion factor for the Icon-FES during its development, but in a later study the use of Icon-FES was shown to be a reliable method of assessing fear of falling in adults with moderate cognitive impairment and that it was also more effective at predicting fall risk than the FES-I (Delbaere et al., 2013).

Discussion

There is an abundance of research and information in the literature regarding fall risk screening and assessment tools available for older adults, supported by the substantial number of papers which were identified in the initial search strategy of this review. However, when the initial screening was conducted for relevance to PLWD, the number of results fell from thousands to tens. Not all fall risk screening and assessment tools may be suitable for use with PLWD, and there is a dearth in the literature of studies which can assist researchers and healthcare providers when considering which option/s are the most suitable for the individual or population being assessed. Additionally, we found that the literature often did not distinguish between screening and assessment, further complicating interpretation for healthcare providers as to which tools are best suited to identify degree of risk verses more comprehensively determining the factors to address in an intervention.

One of the challenges of working with PLWD is that the validity of any tool can be questioned if the cognitive ability of the individual means they have difficulty understanding the instructions or following the directions (McGough et al., 2013; Van Ooteghem et al., 2019). In addition, no two individuals will be affected by dementia in the same way, so the assessor must consider a multitude of factors including personal behaviors such as willingness to cooperate (Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2017). As Ansai et al. (2019) note, this variability in symptoms also creates a challenge in the analysis of research data as a population of “older adults with cognitive impairment” may consist of individuals with very different levels of impairment. Even targeted studies on “dementia” populations may contain individuals with Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body, Vascular, Frontotemporal or another form of dementia, all of which have their own set of symptoms and progression scales. Psychological effects seen among physically healthy older adults also affect PLWD and increase the risk of a fall, such as a fear of falling (Cox & Vassallo, 2015; Uemora et al., 2015).

In the general adult population, the most common screening method for fall risk is obtaining the recent fall history of the individual. However, it is possible that the PLWD may not even remember that they have fallen, which creates challenges in utilizing fall risk screening tools which focus on subjective reporting (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2021; Fischer et al., 2014). The causes of falls, particularly in PLWD, are multifactorial and complex so it is challenging to identify a singular, existing fall risk screening and assessment tool or test which comprehensively and reliably encompasses all the elements of dementia. This review supports the practice of annual screenings and identifies that the questions for this stage should be as simple and clear as possible. The potential use of iconography to improve the fall risk screening process for PLWD, as demonstrated in the Icon-FES FoF test, presents an interesting area for future study. Of the five screening and assessment tools identified in this review, the FROP-com (National Aging Research Institute, 2022) tool appears to be the most inclusive for PLWD, as it distinguishes between screening and assessment, includes Activities of Daily Living (ADL) in the screen, and considers both cognitive and functional aspects in the fall risk assessment. The American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention of Falls in Older Persons (Drootin, 2010) also has potential for use with PLWD, as does the CaHFRiS tool (Whitney et al., 2012) if further research can validate its use in a wider dementia population.

When considering the individual fall risk screening and assessments identified from the selected publications in this review, those which replicate ADL in situations where focus is divided may be the most meaningful assessments for PLWD, such as the Dual Task tests. For example, a testing strategy which utilized the standard TUG, TUG-Cognition and TUG-Manual tests would be able to obtain information on balance, gait, cognition, functional mobility, and dual tasking. This review suggests that the tests which involve detailed instructions or a long sequence of different tests (e.g., POMA; DGI; FGI; PPA) should be avoided due to potential difficulties with comprehension and the willingness of the PLWD to cooperate. However, due to the lack of extensive studies with large sample sizes in this field, it is currently necessary for healthcare workers to use their knowledge of the individual PLWD, the practice guidance available to them, and their clinical judgment when conducting fall risk screening and assessment for PLWD.

This review has not considered any mention in the selected publications of the subsequent processes of fall risk prevention and intervention strategies as they are beyond the scope of this review. However, if they are to be successful, these interventions must be built on a solid foundation of knowledge regarding the individual needs of the PLWD, which can only be achieved if appropriate fall risk screening and assessment methods are utilized.

Recommendations for Future Research

The publications identified in this study have shown that further primary studies with larger sample sizes investigating fall risk screening and assessment for PLWD are required. Research into the validity of using the various tests specifically with PLWD is notably needed if researchers and healthcare providers are to be empowered, via the literature and clinical practice guidelines, to provide the best possible fall risk care for PLWD. We also believe it would be valuable to investigate the extent of duplication and the influence of earlier sources in contemporary research.

Limitations

As detailed in the search strategy and selection strategy, database inclusion was based on immediate relevance in term names. As such, publications which were only in databases not included may have been missed. Likewise, whilst extensive internet searches were conducted for gray literature it is possible that some publications may have been missed. The search terms and exclusion criteria also eliminated any results which were not in English. When considering the review process of clinical practice guidelines and scoping/systematic reviews, there is a limitation regarding the duplication of sources, particularly seminal texts. In some studies, this can result in a size restricted pool of data and the continuation of potentially outdated thinking and approaches. However, for the purposes of this project, such duplication strengthened our understanding surrounding the dearth of research on fall risk screening and assessment for PLWD in the last 10 years. Distinguishing recommendations for screening verses assessment was challenging as the research is not clear on consensus of these definitions or identifying tools specific to one or the other task.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Fall Risk Screening and Assessment for People Living With Dementia: A Scoping Review by Michaela E. Lynds and Catherine M. Arnold in Journal of Applied Gerontology.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kristine Hunter and Catherine Boden for their assistance in conducting this scoping review.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (SHRF) [grant number 425222] and the Centre for Ageing & Brain Health Institute (CABHI) [grant number 425259]. The information, conclusions and opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and no endorsement by SHRF or CABHI is intended or should be inferred.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (2013). Preventing falls in hospitals: A toolkit for improving quality of care. Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality, https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications2/files/fallpxtoolkit-update.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association (2022). Dementia vs. Alzheimer’s disease: What is the difference? Chicago. Alzheimer’s Association, https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/difference-between-dementia-and-alzheimer-s [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Society of Canada (2016). Prevalence and monetary costs of dementia in Canada. Alzheimer Society of Canada, 10.24095/hpcdp.36.10.04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ansai J. H., Andrade L. P. D., Masse F. A. A., Goncalves J., Takahashi A. C. d. M., Vale F. A. C., Rebelatto J. R. (2019). Risk factors for falls in older adults with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer disease. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 42(3), 116–121. 10.1519/jpt.0000000000000135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris E., Riitano D. (2014). Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence: A guide to the literature search for systematic review. The American Journal of Nursing, 114(5), 49–56. 10.1097/01.naj.0000446779.99522.f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Ministry of Health (2021). Fall prevention: Risk assessment and management for community-dwelling older adults. British Columbia Ministry of Health. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/fall-prevention [Google Scholar]

- Buttery A. K., Hopper A., Martin F. C. (2017). Optimising falls risk assessment in memory services. https://healthinnovationnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Optimising-Falls-Risk-Assessment-in-Memory-Services.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (2018). Dementia in Canada. Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/dementia-in-canada. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). Stay independent brochure. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/STEADI-Brochure-StayIndependent-508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cox C., Vassallo M. (2015). Fear of falling assessments in older people with dementia. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 25(2), 98–106. 10.1017/S0959259815000106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delbaere K., Close J. C. T., Taylor M., Wesson J., Lord S. R. (2013). Validation of the iconographical falls efficacy scale in cognitively impaired older people. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 68(9), 1098–1102. 10.1093/gerona/glt007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolatabadi E., Van Ooteghem K., Taati B., Iaboni A. (2018). Quantitative mobility assessment for fall risk prediction in dementia: A systematic review. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 45(5–6), 353–367. 10.1159/000490850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drootin M. (2010). Summary of the updated American geriatrics society/British geriatrics society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 3234. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EBSCO Connect (2022). Searching with boolean operators. Ipswich. https://connect.ebsco.com/s/article/Searching-with-Boolean-Operators?language=en_US [Google Scholar]

- Fernando E., Fraser M., Hendriksen J., Kim C. H., Muir-Hunter S. W. (2017). Risk factors associated with falls in older adults with dementia: A systematic review. Physiotherapy Canada. Physiotherapie Canada, 69(2), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.3138%2Fptc.2016-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B. L., Hoyt W. T., Maucieri L., Kind A. J., Gunter-Hunt G., Swader T. C., Gangnon R. E., Gleason C. E. (2014). Performance based assessment of falls risk in older veterans with executive dysfunction. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 51(2), 263–274. 10.1682/jrrd.2013.03.0075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florence C. S., Bergen G., Atherly A., Burns E., Stevens J., Drake C. (2018). Medical costs of fatal and nonfatal falls in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(4), 693–698. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fjgs.15304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R., Todd C., May M., Yardley L., Ben-Shlomo Y. (2010). Socio-demographic factors predict the likelihood of not returning home after hospital admission following a fall. Journal of Public Health, 32(1), 117–124. 10.1093/pubmed/fdp077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks S., Peetoom K., Bakker C., van der Flier W. M., Papma J. M., Koopmans R., Verhey F. R. J., de Vugt M., Kohler S., Withall A., Parlevliet J. L., Uysal-Bozkir O., Gibson R. C., Neita S. M., Nielsen T. R., Salem L. C., Nyberg J., Lopes M. A., Ruano L. (2021). Global prevalence of young-onset dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurology, 78(9), 1080–1090. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak F. B., Wrisley D. M., Frank J. (2009). The balance evaluation systems test (BESTest) to differentiate balance deficits. Physical Therapy, 89(5), 484–498. 10.2522/ptj.20080071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanna Briggs Institute (2015). Reviewers manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Joanna Briggs Institute. https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/Scoping-.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lach H. W., Harrison B. E., Phongphanngam S. (2017). Falls and fall prevention in older adults with early-stage dementia: An integrative review. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 10(3), 139–148. 10.3928/19404921-20160908-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMantia M. A., Stump T. E., Messina F. C., Miller D. K., Callahan C. M. (2016). Emergency department use among older adults with dementia. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 30(1), 35–40. 10.1097/wad.0000000000000118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. C. (2017). Managing the elderly with dementia and frequent falls. General Medicine Open, 2(1), 1–4. 10.15761/GMO.1000120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindt N., van Berkel J., Mulder B. C. (2020). Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 304. 10.1186/s12877-020-01708-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGough E. L., Logsdon R. G., Kelly V. E., Teri L. (2013). Functional mobility limitations and falls in assisted living residents with dementia: Physical performance assessment and quantitative gait analysis. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 36(2), 78–86. 10.1519/jpt.0b013e318268de7f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendeley Ltd (2022). Mendeley reference manager. Mendeley Ltd. https://www.mendeley.com/reference-management/reference-manager. [Google Scholar]

- Mesbah N., Perry M., Hill K. D., Kaur M., Hale L. (2017). Postural stability in older adults with Alzheimer disease. Physical Therapy, 97(3), 290–309. 10.2522/ptj.20160115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modarresi S., Divine A., Grahn J. A., Overend T. J., Hunter S. W. (2019). Gait parameters and characteristics associated with increased risk of falls in people with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(9), 1287–1303. 10.1017/s1041610218001783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Odasso M., Muir S. W., Speechley M. (2012). Dual-task complexity affects gait in people with mild cognitive impairment: The interplay between gait variability, dual tasking and risk of falls. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(2), 293–299. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Odasso M., Speechley M. (2018). Falls in cognitively impaired older adults: Implications for risk assessment and prevention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(2), 367–375. 10.1111/jgs.15219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir S. W., Speechley M., Wells J., Borrie M., Gopaul K., Montero-Odasso M. (2012). Gait assessment in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: The effect of dual-task challenges across the cognitive spectrum. Gait & Posture, 35(1), 96–100. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Ageing Research Institute (2022). Falls risk for older people in the community (Frop-Com) screen. National Ageing Research Institute. https://www.nari.net.au/frop-com [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Aging (2022). Get the facts on fall prevention. National Council on Aging. https://ncoa.org/article/get-the-facts-on-falls-prevention [Google Scholar]

- Nurses’ Association of Ontario, Registered (2017). Preventing falls and reducing injury from falls. Nurses’ Association of Ontario Registered. https://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/prevention-falls-and-fall-injuries [Google Scholar]

- Okoye S. M., Fabius C. D., Reider L., Wolff J. L. (2023). Predictors of falls in older adults with and without dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 2023, 1–10. 10.1002/alz.12916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parachute Canada (2021). Potential lost, potential for change: The cost of injury in Canada 2021. Parachute Canada. https://parachute.ca/en/professional-resource/cost-of-injury-in-canada/ [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C., St-Arnaud J., Geran L. (2014). Understanding seniors’ risk of falling and their perception of risk. Statistique Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-624-x/2014001/article/14010-eng.pdf?st=vnBAz28I [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo D., Richardson S. (1991). The timed up & Go: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 39(2), 142–148. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2014). Seniors’ falls in Canada: Second report. Public Health Agency of Canada; https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/migration/phac-aspc/seniors-aines/publications/public/injury-blessure/seniors_falls-chutes_aines/assets/pdf/seniors_falls-chutes_aines-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2017). Dementia in Canada, including Alzheimer’s disease. Highlights from the Canadian chronic disease surveillance system. Public Health Agency of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/diseases-conditions/dementia-highlights-canadian-chronic-disease-surveillance/dementia-highlights-canadian-chronic-disease-surveillance.pdf [Google Scholar]

- QSR International (2018). NVivo v.12. QSR International. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/about/nvivo [Google Scholar]

- Renfro M., Maring J., Bainbridge D., Blair M. (2016). Fall risk among older adult high-risk populations: A review of current screening and assessment tools. Current Geriatrics Reports, 5(3), 160–171. 10.1007/s13670-016-0181-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renfro M. O., Fehrer S. (2011). Multifactorial screening for fall risk in community dwelling older adults in the primary care office: Development of the Fall Risk Assessment & Screening Tool. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 34(4), 174–183. 10.1519/jpt.0b013e31820e4855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J. J., McCloy C., Rundquist P., Srinivasan V., Laird R. (2011). Fall risk assessment among older adults with mild Alzheimer disease. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 34(1), 19–27. 10.1519/jpt.0b013e31820aa829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saskatoon Falls Prevention Consortium (2017). Screening and referral tools for community dwelling adults. Saskatoon Falls Prevention Consortium. https://www.saskatoonhealthregion.ca/locations_services/Services/Falls-Prevention/providers/Pages/Assessment-Tools.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. E., Delbaere K., Close J. C. T., Lord S. R. (2012). Managing falls in older patients with cognitive impairment. Aging Health, 8(6), 573–588. 10.2217/ahe.12.68 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein S., Maurus P., Barisch-Fritz B., Hadzic A., Woll A. (2019). Recommended motor assessments based on psychometric properties in individuals with dementia: A systematic review. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity: Official Journal of the European Group for Research Into Elderly and Physical Activity, 16(20), 20. 10.1186/s11556-019-0228-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura K., Shimada H., Makizako H., Doi T., Tsutsumimoto K., Lee S., Umegaki H., Kuzuya M., Suzuki T. (2015). Effects of mild cognitive impairment on the development of fear of falling in older adults: A prospective cohort study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(12), 1104 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ooteghem K., Musselman K., Gold D., Marcil M. N., Keren R., Tartaglia M. C., Flint A. J., Iaboni A. (2019). Evaluating mobility in advanced dementia: A scoping review and feasibility analysis. The Gerontologist, 59(6), 683–696. 10.1093/geront/gny068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney J., Close J. C. T., Lord S. R., Jackson S. H. D. (2012). Identification of high risk fallers among older people living in residential care facilities: A simple screen based on easily collectable measures. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55(3), 690–695. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Roberts H., Arnold C., Kemp D., Crizzle A., Johnson S. (2020). Scoping review of clinical practice guidelines for fall risk screening and assessment in older adults across the care continuum. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du Vieillissement, 40(2), 206–223. 10.1017/S0714980820000112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (2015). World report on ageing and health. World Health Organisation. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186463 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (2016). Falls factsheet. World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Low L. F., Schwenk M., Mills N., Gwynn J. D., Clemson L. (2019). Review of gait, cognition, and fall risks with implications for fall prevention in older adults with dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 48(1–2), 17–29. 10.1159/000504340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Fall Risk Screening and Assessment for People Living With Dementia: A Scoping Review by Michaela E. Lynds and Catherine M. Arnold in Journal of Applied Gerontology.