Abstract

The common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) is increasingly recognized as an ideal nonhuman primate (NHP) at high biocontainment due to its smaller size and relative ease of handling. Here, we evaluated the susceptibility and pathogenesis of Nipah virus Bangladesh strain (NiVB) infection in marmosets at biosafety level 4. Infection via the intranasal and intratracheal route resulted in fatal disease in all 4 infected marmosets. Three developed pulmonary edema and hemorrhage as well as multifocal hemorrhagic lymphadenopathy, while 1 recapitulated neurologic clinical manifestations and cardiomyopathy on gross pathology. Organ-specific innate and inflammatory responses were characterized by RNA sequencing in 6 different tissues from infected and control marmosets. Notably, a unique transcriptome was revealed in the brainstem of the marmoset exhibiting neurological signs. Our results provide a more comprehensive understanding of NiV pathogenesis in an accessible and novel NHP model, closely reflecting clinical disease as observed in NiV patients.

Keywords: Nipah virus Bangladesh, RNA-seq, cardiomyopathy, common marmoset, inflammatory response, neurological disease, nonhuman primate, pathogenesis, respiratory disease

Nipah virus (NiV), a zoonotic, bat-borne negative-sense paramyxovirus of the genus Henipavirus, has seen outbreaks in humans nearly every year since 1998. There have been over 600 cases of respiratory and/or neurological disease in patients, 59% percent of which resulted in death [1–3]. All but 2 major outbreaks have been caused by NiV-Bangladesh (NiVB), which has had a higher case fatality rate of 76% relative to the other NiV clade, NiV-Malaysia (NiVM), which has had a case fatality rate of 39% [2]. NiVB has a shorter average incubation period, higher rate of respiratory symptoms, and smaller proportion of patients exhibiting segmental myoclonus relative to NiVM [4–6]. Human-to-human transmission has also been seen more commonly in NiVB outbreaks but is extremely rare in NiVM outbreaks [7]. Given these significant differences animal models successfully recapitulating NiVB pathology in humans are especially critical.

Several nonhuman primate (NHP) models have been used to investigate NiV pathogenesis and vaccine research: African green monkeys (AGM; Chlorocebus aethiops;), cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis), squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus), and grivets (Chlorocebus aethiops) [8–22]. Among these, only AGMs faithfully recapitulate the high lethality of NiVB exposure as well as most clinical signs observed in patients. However, overt clinical signs of neurological disease are seen very rarely in AGMs despite neurological disease being commonly found via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and post mortem histopathology. Additionally, myocarditis has been consistently reported among patients infected with NiVB but reports of myocarditis in animal models are rare [23].

AGMs are still able to replicate much of the other hallmark clinical pathology and histopathology of NiV infection: systemic vasculitis, hypoalbuminemia, pneumonitis, coagulopathy, and congestion in the liver and spleen [9, 10, 13]. Transcriptional profiling in AGMs has also shown significant upregulation in innate immune signaling genes (MX2, OASL, OAS2), particularly among nonsurvivors of infection relative to survivors [13]. Others have shown that NHP models show an especially robust expression of interferon-stimulated genes in the lung, including ISG15 and OAS1 [24].

There has been notable success using AGMs as a model for NiVB infection, especially in the evaluation of vaccine candidates and therapeutics [11, 14]. However, the lack of clinical neurological manifestations and myocarditis, the logistical difficulties associated with AGMs’ larger size, and the shortage of animals due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) research, call for a diversification in the preclinical testing portfolio of NHP models. We show here that NiVB infection of the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) can faithfully recapitulate pathology seen in humans. Marmosets were chosen due to several distinct advantages. First, they are an ideal NHP model for studying high-biocontainment human respiratory pathogens given their small size and relative ease of handling. Second, they are the first among New World monkeys to have their whole genome sequenced and assembled allowing for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to elucidate transcriptomic changes in infected and uninfected tissues [25]. Lastly, transmission experiments may be easier given the requirement of cohousing, and their high reproductive efficiency and short gestation period and delivery interval allows for easier development of transgenic animals [26]. With these advantages in mind, results of this study identified marmosets as a highly susceptible novel New World NHP model of NiVB infection and pathogenesis.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) and performed following the guidelines of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC) by certified staff in an AAALAC-approved facility. Animals were cohoused allowing social interactions, under controlled conditions of humidity, temperature, and light. Animals were monitored pre- and postinfection and fed commercial monkey chow, treats, and fruit twice daily. Food and water were available ad libitum and environmental enrichment consisted of commercial toys. Procedures were conducted by biosafety level 4 (BSL4)-trained personnel under the oversight of an attending BSL4-trained veterinarian. All invasive procedures were performed on animals under isoflurane anesthesia. Animals that reached euthanasia criteria were euthanized using a pentobarbital-based solution.

Virus and Cells

NiVB (200401066 isolate) was kindly provided by Dr Thomas Ksiazek (UTMB). The virus was propagated on Vero E6 cells (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], CRL1586) and virus titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells (ATCC, CCL-81) as previously described [27]. All work with infectious virus was performed at BSL4 biocontainment at the Galveston National Laboratory at UTMB.

Animal Studies

Four healthy marmosets (2 females, 2 males; 348–453 grams, 2–7 years old, Worldwide Primates, Inc) were inoculated with 6.33E + 04 plaque forming units of NiVB (0.5 mL), dividing the dose equally between the intranasal (IN) and intratracheal (IT) routes for each animal. After infection, animals were closely monitored for signs of clinical illness, changes in body temperature (BMDS transponders) and body weight. A scoring system was utilized monitoring respiratory, food intake, responsiveness, and neurological parameters to determine study endpoint. Infected animals exhibiting weight loss >20% or clinical signs approaching multiple organ dysfunction syndrome were immediately euthanized. In addition, changes in blood chemistry and hematology were monitored. Blood was collected via the femoral vein and animals were anesthetized using isoflurane (1%–5%). The naive marmoset is a 4-year-old male with no mock inoculation.

Hematology and Serum Biochemistry

Blood was collected in tubes containing EDTA and complete blood counts (CBC) were evaluated with a VetScan HM5 (Abaxis). Hematological analysis included total white blood cell counts, white blood cell differentials, red blood cell counts, platelet counts, hematocrit, total hemoglobin concentrations, mean cell volumes, mean corpuscular volumes, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentrations. Clinical chemistry analysis was performed using a VetScan2 Chemistry Analyzer. Serum samples were tested for concentrations of albumin, amylase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, glucose, total protein, and plasma electrolytes (calcium, phosphorus, sodium, and potassium, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and globulin).

X-Ray Images

X-ray images were obtained using the MinXray model HF 100/30 portable x-ray unit (MinXray) operated at 78 kVp 12 3.20 mAs, 100 cm from the subject. A Fuji DR 35 × 43 cm panel served as the exposure plate and the images were processed in the SoundVet application (SoundVet).

Sample Collection and RNA Isolation

Whole blood was collected in EDTA Vacutainers (Beckman Dickinson) for hematology and serum biochemistry, while another part was mixed with TRIzol LS for RNA extraction. At euthanasia, full necropsies were performed and tissues were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Qiagen) using Qiagen TissueLyser and stainless-steel beads. The liquid phase was stored at −80°C. All samples were inactivated in TRIzol LS prior to removal from the BSL4 laboratory. Subsequently, RNA was isolated from blood using the QIAamp viral RNA kit (Qiagen) and from tissues using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RT-qPCR of Extracts From Tissue Samples

RNA was extracted using Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kits (Zymo Research). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was run using QuantiFast RT-PCR mix (Qiagen), probes targeting NiVM P gene (5′-ACATACAACTGGACCCARTGGTT-3′ and 5′-CACCCTCTCTCAGGGCTTGA-3′) Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), and fluorescent probe (5′-6FAM-ACAGACGTTGTATA + C + CAT + G-TMR (tetramethylrhodamine)) (TIB Molbiol). RT-qPCR was performed using the following cycle: 10 minutes at 50°C, 5 minutes at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 10 seconds at 95°C and 30 seconds at 60°C using a BioRad CFX96 real time system. Assays were run in parallel with uninfected hamster tissues and a NiVM stock standard curve.

Virus Titration

Virus titration was performed by plaque assay on Vero cells as previously described [27].

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were immersion-fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 21 days under BSL4 conditions with regular formalin changes following approved protocols. Specimens were then transferred to and processed under BSL2 conditions. Briefly, tissues were dehydrated through a series of graded ethanol baths, infiltrated by and embedded with paraffin wax, sectioned at 5 µm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemistry for NiV nucleoprotein detection was performed using a rabbit anti-NiV-nucleoprotein antibody incubated overnight (kindly provided by Dr Christopher Broder, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland) and a secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antirabbit antibody (Abcam) incubated for 2 hours (both 1:1000). 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) substrate (ThermoScientific) was then added for 2 minutes for chromogenic detection of horseradish peroxidase activity.

RNA Sequencing

Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 (Illumina) or TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform using a single-end 150-base pair format (PRJNA906605). Across all marmosets 5 tissue samples were sequenced (lung, inguinal lymph node, kidney, brainstem, and spinal cord) with gonads sequenced only in the infected marmosets. Tissues from the naive marmoset were sequenced in technical duplicate. Tissues from naive marmoset were kindly provided by Dr Ricardo Carrion Jr (Texas Biomedical Research Institute, San Antonio, Texas).

RNA-seq Data Processing

Trimming, alignment, and quantification were all performed in Partek Flow version 10.0 [28]. Ends were trimmed based on quality score then aligned to the C. jacchus genome (Ensemble release 91) [29] using Bowtie2 version 2.2.5. Counts were generated with C. jacchus annotation version 105 (Partek E/M). Normalization was performed by trimmed mean of M values. Six samples were removed from the final analysis based on either having fewer than 1E + 06 mapped reads or were both determined to be outliers based on principal component analysis (PCA) and failed multiple FastQC quality control metrics [30]. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using Partek's gene-specific analysis model.

Unaligned reads were then aligned to NiVB (GenBank: AY988601.1) using BWA-MEM (BWA version 0.7.17). Transcriptional gradient analyses were performed using IGVtools on samples with >100 aligned reads. P editing was measured using mPileup in Samtools version 1.8 [31], selecting reads with inserts of Gs only and samples with >100 reads at the P editing site.

Statistical Analysis, Gene Set Analysis, and Visualization

PCA and hierarchical clustering was performed using Partek Flow version 10.0. Functional enrichment analysis was performed using PantherDB's Biological Processes Gene Ontology (GO) annotation set [32] unless otherwise noted. Gene lists were acquired via Partek's gene-specific analysis model, filtering by false discovery rate (FDR) step-up < 0.05 and fold change > 2. Gene lists were analyzed via the PANTHER Overrepresentation Test, annotation version release data 18 August 2021. Due to a lack of gene ontology sets for C. jacchus, the Homo sapiens GO biological process complete annotation data set was utilized. Only GO terms where FDR < 0.01 were used. GO terms along with accompanying FDR were clustered and visualized using REVIGO [33].

RESULTS

NiVB Infection and Pathogenesis in Marmosets

In the studies described here, we evaluated the susceptibility and suitability of the common marmoset to infection with NiVB. Four marmosets were infected with NiVB by the IN/IT routes and, throughout the course of the study, survival, body weights, body temperature, blood chemistry, and CBC were determined (Supplementary Figures 1 and 3–6). All animals developed clinical signs of disease and reached euthanasia criteria between days 8 and 11 postinfection (Table 1). The first signs of infection were seen by day 8 when subjects No. 300 and No. 425 displayed anorexia and hyperventilation. Subject No. 425 then became lethargic and reached euthanasia criteria. Subject No. 300 deteriorated on day 9, when found with open-mouth breathing and reached euthanasia criteria. Subject No. 193 had a reduced food consumption by day 9, and by day 11 was hyperventilating and lethargic and reached euthanasia criteria. Subject No. 340 was normal through day 10 postinfection, then developed a hunched posture, and on day 11 postinfection was hyperventilating and reached euthanasia criteria. Furthermore, No. 340 presented left hindlimb tremors on the day of euthanasia, reflecting signs of neurological impairment.

Table 1.

Clinical Description and Diagnosis in Nipah Virus Bangladesh Strain Infected Marmosets

| Clinical Diagnosis | No. 193 (Male) | No. 300 (Female) | No. 340 (Female) | No. 425 (Male) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffuse pulmonary edema and hemorrhage | + | + | − | + |

| Diffuse hemorrhagic hepatitis | + | + | + | + |

| Multifocal hemorrhagic lymphadenopathy | + | + | − | + |

| Hemorrhagic tonsilitis | − | + | − | − |

| Splenic congestion | − | − | − | + |

| Left ventricular cardiomyopathy/right atrial dilation | − | − | + | − |

| Cerebral infarct and malacia in the occipital lobe | − | − | + | − |

| Cerebral edema | − | − | + | − |

| Left hindlimb tremors at euthanasia | − | − | + | − |

| Time of necropsy, days postinfection | 11 | 9 | 11 | 8 |

Clinical descriptions and diagnoses of all 4 marmosets infected with Nipah virus Bangladesh strain . Further detail is available in Supplementary Table 1.

To monitor development of respiratory disease, we used X-ray radiographic imaging (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 2). Prior to day 7, no radiographic changes were observed in the lungs. By euthanasia, virtually no normal lung was observed for animals No. 425, No. 300, and No. 193. Animal No. 340 exhibited some inflammation around the smaller bronchi. Gross pathology found <5%–10% normal lung tissues in the cranial portion of the lung (Figure 1B and Supplementary Table 1) while the rest was filled with hemorrhagic/serous fluid. The livers had multifocal to coalescing regions of pale circles and were very friable (Figure 1C). Lymph nodes had gross enlargement and hemorrhage and in animal No. 425, the spleen was friable and congested. Interestingly, animal No. 340 presented with neurological involvement as well as a less severe infection of the lungs. An infarct was found, as well as malacia near the transition zone between grey and white matter in the occipital lobe of the left cerebral hemisphere, and edema was present in the cerebrum. According to these observations, marmosets developed diffuse pulmonary edema and hemorrhage, diffuse hemorrhagic hepatitis, and multifocal hemorrhagic lymphadenopathy. Of note, 1 animal (No. 340) had both left ventricular cardiomyopathy and neurological complications.

Figure 1.

Progressive pathogenesis in marmosets after Nipah virus Bangladesh strain (NiVB) infection. A, Subject No. 300 was positioned in a ventral dorsal position and all images are in a R → L orientation. X-ray images of the chest were taken on days 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, and at euthanasia. Prior to day 7, lungs appeared normal. Progressive lung pathology was detected from day 7 onward, with a decrease in normal lung tissue over the experimental infection course. By day 7, some decreasing opacity was observed along with an appearance of an interstitial pattern. At the time of euthanasia (day 9 postinfection), virtually no normal lung was observed as the lungs develop a nodular alveolar pattern, suggesting the alveoli were filled with fluid. B, Lung of subject No. 425 at time of euthanasia at day 8 postinfection. Acute diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage, with hemorrhage involving all lobes and <10% of normal tissue remaining. C, Liver of subject No. 425. Diffuse massive necrosis of the liver, with necrosis involving all lobes and normal structure visible.

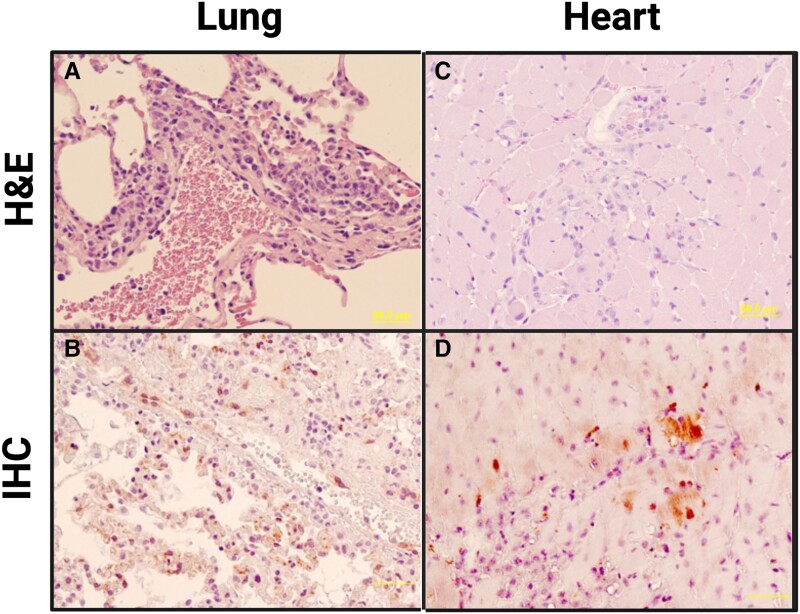

Histopathological and immunohistochemical examination of the lungs showed that all animals had mild to moderate infiltrate in pulmonary vessels (Figure 2A). Both syncytia formation and NiV antigen were evident in endothelial and smooth muscle cells in pulmonary vessels as well as capillary endothelial cells in the alveolar septum in all 4 animals (Figure 2B). Furthermore, histopathological lesions in subject No. 425 suggests myocarditis associated with the infiltration of mononuclear cells and neutrophils (Figure 2C). Viral antigen was found in the heart smooth muscle cells and capillary or arteriole endothelial cells (Figure 2D). Viral antigen was also detected in the heart smooth muscle cells and capillary endothelial cells of No. 300. No detectable lesions or viral antigen were found in the testes, bronchus, or central nervous system (CNS) of any subjects. Significant histopathological changes and viral antigen were found in the liver, spleen, and kidneys of all marmosets (Supplementary Figure 7).

Figure 2.

Histopathological changes in marmoset tissues after Nipah virus Bangladesh strain (NiVB) infection: (A and C) hematoxylin and eosin staining; (B and D) immunohistochemical staining for NiV nucleoprotein. A, Lung (subject No. 340): mild to moderate infiltration of mononuclear cells (macrophages, monocytes) and neutrophils in perivascular space. B, Lung (subject No. 425): NiV antigen present in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells of pulmonary vessels (arteriole, venule). C, Heart (subject No. 425): mild myocarditis with necrosis of myocytes and infiltration of mononuclear cells and neutrophils. D, Heart (subject No. 425): NiV antigen present in capillary and arteriole endothelial cells, as well as heart muscle cells. Scale bar for all images = 50 µm.

Blood chemistry and CBC were monitored at days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 postinfection (Supplementary Figures 3–6). Subject No. 193 showed an increased white blood cell 1 day before euthanasia, indicative for leukocytosis (Supplementary Figure 3). Neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytosis immediately before euthanasia was noted for subjects No. 193 and No. 300, and subjects No. 193, No. 300, and No. 425, respectively. Additionally, basophilia was noted for subjects No. 193 and No. 340 starting 1 day postinfection. Subject No. 425 showed marked increases in hematocrit and platelet counts 1 day prior to euthanasia, possibly indicating reactive thrombocytosis.

The elevations in alanine aminotransferase are suggestive of hepatocyte damage in No. 193 and No. 425 (Supplementary Figure 4) and are consistent with our histopathological results and reflective of laboratory abnormalities found in NIV-infected patients (Supplementary Figure 7).

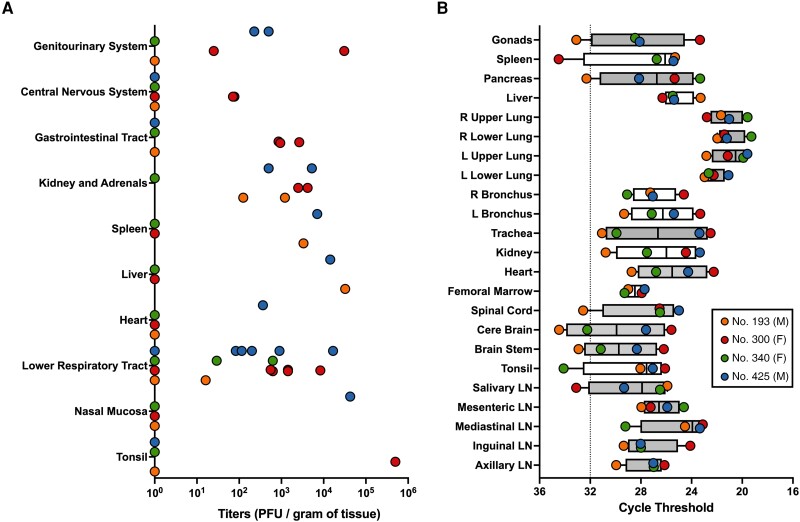

Viral Titers and RT-qPCR in Tissues

Twenty-three tissues were collected at euthanasia to determine viral titer (Figure 3A) and measure viral RNA (Figure 3B). Titerable virus was found in 19 of the tissues evaluated. No. 425 had detectable NiVB in 7 of the 10 tissue groups examined, No. 300 in 6, No. 193 in 4, and 1 in No. 340. Infectious virus was found in both the brainstem and the cerebellum of No. 300. Viral RNA was detected in at least 1 marmoset in each tissue evaluated. Viral RNA was found in the CNS for all marmosets except No. 193.

Figure 3.

Viral titers and viral quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) data across various tissues. A, At time of euthanasia, tissues were collected. Viral titers were determined by plaque assay in 23 tissues, combined into 10 tissues systems seen here. Values equal to zero were set to 100 for log-scale visualization. Tissue systems with more than 1 tissue type are lower respiratory tract (trachea, left upper lobe, left lower lobe, right upper lobe, and right lower lobe of the lung as well as each of the left and right bronchi), kidney and adrenals (kidney and adrenal gland), gastrointestinal tract (pancreas, jejunum, and colon transversum), central nervous system (brain-frontal, brain-cerebellum, brainstem, and cervical spinal cord), and genitourinary system (urinary bladder and gonads). B, RT-qPCR was performed to determine relative amounts of viral RNA across 23 tissues. Average cycle threshold for uninfected samples is shown (dotted line). Fill color for box and whisker plots denote similar tissue types (eg, all lymph node [LN] samples are adjacent and grey). Both right (R) and left (L) lower and upper lung samples are adjacent and also grey. Box and whisker plot shows median line, box from 25th to 75th percentiles, and whiskers extending to minimum and maximum values.

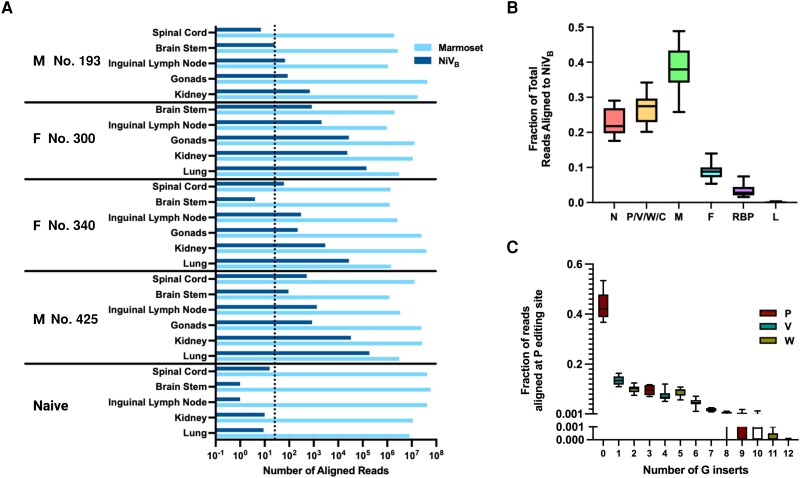

RNA-seq of NiVB and C. jacchus in Infected Tissues

RNA was extracted from spinal cord, brainstem, inguinal lymph node, gonads, kidney, and lung. The average sample contained 17.4 million reads aligned to C. jacchus and the most highly infected tissue contained >180 000 NiVB reads (Figure 4A). In the marmoset model, NiVB exhibits a transcriptional gradient that does not drop significantly until after N, P, and M (Figure 4B). Despite the steep transcriptional gradient after M, 3 samples achieved >95% coverage of L. We also measured RNA editing in P and found approximately 40% of all P-derived reads were V and W and the most Gs inserted into any read were 12 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

RNA sequencing of Nipah virus Bangladesh strain (NiVB) in infected marmoset tissues. A, Total number of reads aligned to Callithrix jacchus and NiVB are shown across all tissues and samples. The dotted line is placed 3 standard deviations above the median number of reads aligning to NiVB across all naive samples, the threshold for inclusion into (B). B, The fraction of total reads aligning to each NiVB gene across all samples exceeding 100 NiVB reads, normalized by transcript length. C, The fraction of reads with the indicated number of inserted guanines (Gs) at the RNA editing site in P for all samples with a depth of at least 100 reads at the RNA editing site. Box and whisker plots shows median line, box from 25th to 75th percentiles, and whiskers extending to minimum and maximum values.

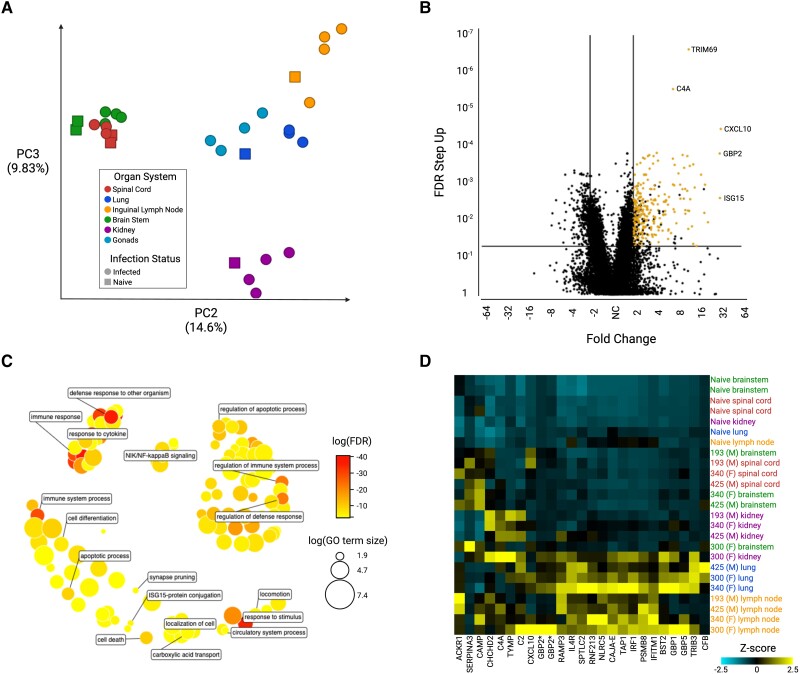

As expected, PCA shows that samples primarily cluster based on tissue-type (Figure 5A). Using differential expression analysis, 293 genes were found to be both consistently upregulated in each tissue and significantly upregulated when comparing all infected tissues against all uninfected tissues (Figure 5B). Enrichment analysis with these genes shows innate- and inflammatory-associated biological processes, in addition to processes involved in apoptosis and cell death (Figure 5C). Hierarchical clustering with the 25 most significant of these genes shows clustering based on both tissue type and infection status (Figure 5D). Genes involved in the compliment cascade, interferon signaling, and genes in the major histocompatibility complex locus are well represented.

Figure 5.

RNA sequencing samples aligned to Callithrix jacchus. A, Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on all samples showing that organ system is the primary driver of gene expression differences between samples. Samples from similar organ systems (eg, brainstem and spinal cord) also group together. PC1 is not shown as it is primarily driven by expression differences separating male and female gonad samples from the rest of the dataset. B, A volcano plot comparing all infected samples to all uninfected samples. Lines are placed at 2 (high expression in infected samples) and −2 (higher expression in uninfected samples) as well as false discovery rate (FDR) = 0.05. The 293 genes highlighted in yellow are upregulated in each individual tissue comparison of infected versus uninfected, and in the total sample set are at least 2-fold higher expressed in infected versus uninfected with an FDR step-up value of ≤0.05. C, The 293 yellow-highlighted differentially expressed genes from (B) were used to obtain enriched gene ontology (GO) gene sets, and similar terms were clustered in semantic space using REVIGO [33]. Log10(FDR) of the gene set is indicated by the color and log10 of the number of terms in the gene set is indicated by the size of the circle. D, Differential expression analysis across all samples was used to identify the top 25 genes most overexpressed in infected versus uninfected samples—ranked by FDR step-up value—and hierarchical clustering was performed to obtain a heatmap. *An orthologue or “like” protein via the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

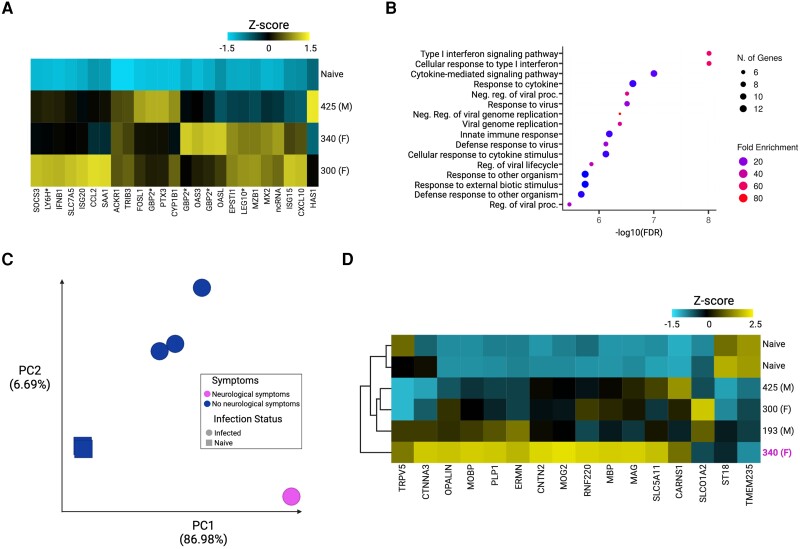

We also focused specifically on the lungs and the brainstem. In the lungs we see interferon-stimulated genes such as ISG15, OAS3, OASL, and IFNB1 upregulated in infected tissues (Figure 6A). Here, the high enrichment of innate and inflammatory pathways is particularly obvious (Figure 6B). We also found that in the brainstem of the only marmoset with neurological signs, No. 340, the transcriptome is distinct (Figure 6C). Using gene ontology, we found significant enrichment in terms dealing with myelination and oligodendrocyte function. We then identified OPALIN, a marker of oligodendrocytes in gene expression profiling, and OPALIN's 15 nearest neighbors based on single-cell RNA expression data according to the Human Protein Atlas [38]. Using this we show that only marmoset No. 340 had high expression across all the identified genes (Figure 6D, magenta). These results may be noteworthy given previous findings of significant myelin degradation and axonal NiV aggregation in hamsters infected with NiVM [39].

Figure 6.

Organ-specific responses seen in RNA sequencing samples aligned to Callithrix jacchus. A, Differential expression analysis across all lung tissue samples was used to identify the top 25 genes most overexpressed in infected versus uninfected lung samples—ranked by FDR step-up value—and hierarchical clustering was performed to obtain a heatmap. B, Enrichment analysis with these 25 genes was performed via ShinyGo 0.76 [34] to identify the top 20 most enriched gene sets. C, Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on all brainstem samples. The top 2 principal components and their relative contributions are shown. Tissues from infected animals (circles) and tissues from the uninfected animal (squares) are further broken down to highlight the brainstem tissue from the only marmoset showing neurological signs—marmoset No. 340 is an outlier by PCA. D, OPALIN, a marker of oligodendrocytes in gene expression profiling [35], and its 15 nearest neighbors based on single cell type RNA expression data [36, 37] were selected and hierarchical clustering was performed on all brainstem samples. The only marmoset with neurological signs (No. 340, magenta) is a clear outlier and the only marmoset showing high levels of expression of oligodendrocyte-related genes. *An orthologue or “like” protein via the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

DISCUSSION

In this study we identify marmosets as a highly susceptible, novel New World NHP model of NiVB infection. Four marmosets were infected with NiVB via the IN/IT routes and all 4 animals succumbed to infection by day 11 postinfection. The marmosets recapitulated many of the same clinical manifestations seen in patients and other NHP models infected with NiV, such as anorexia, lethargy, and hyperventilation. Of special note, 1 marmoset presented with left hindlimb tremors on day 11 postinfection, displaying overt neurological signs. In the setting of acute infection of NHPs with NiVB, neurological signs are rare [22] although neurological disease seen via MRI, histopathology, or gross pathology is relatively common [10, 12, 15, 19, 21]. Among NHPs neurological clinical manifestations are more common in NiVM than NiVB, especially among those surviving longer [9, 16, 17]. This may give some insight into the development of neurological clinical manifestations in the same marmoset (No. 340) that presented a less severe infection of the lungs. No. 340 was found to have a cerebral infarct, malacia, and cerebral edema. This animal, uniquely, also displayed left ventricular cardiomyopathy.

On histopathological examination, all marmosets were found to have significant multifocal coagulation in the liver, syncytia formation of endothelial cells in the kidney, and infiltration in the lung. NiV antigen was found in syncytial cells across multiple tissues, notably in the smooth muscle cells and capillary endothelial cells of the heart. All marmosets also showed consistent hypoalbuminemia and decreases in amylase, indicating pancreatic damage. These findings replicate the clinical and pathophysiological picture of NiV infection in NHPs.

Titerable virus was found in all tissue sets evaluated, including the CNS, but some variance was seen across subjects. Similarly, viral RNA was most prevalent in the lower respiratory tract, as expected, but was also found within the CNS for No. 300, No. 340, and No. 425.

RNA-seq provided a deeper insight into both the NiVB and marmoset transcriptional patterns across multiple tissues. NiVB displayed a transcriptional gradient that did not drop until after matrix, a pattern not typically seen among other viruses of the family Paramyxoviridae [40, 41] but previously noted in vitro with NiV [27]. We also showed that RNA editing of P results in 40% of the total reads being nearly equally split between W and V, in contrast to the often smaller fraction seen in other paramyxoviruses [42, 43]. However, our results replicate previous findings specific to NiVB [44]. Similarly, we replicated in vivo findings that the number of G additions is nearly flat from +1 to +5 in HEK293 cells [44].

As expected, across all tissues we observed a consistent upregulation of gene ontologies relating to regulation of viral processes and interferon-stimulated genes. We found results mirroring those found in AGMs with significant upregulation of genes such as MX2, OASL, CCL2, and ISG15 in the most highly infected tissue, the lung [15]. In brainstem samples specifically, the only marmoset with neurologic signs was shown to have a unique transcriptional pattern enriched in genes relating to myelination, axon ensheathment, and oligodendrocyte development. Previous findings of myelin degradation and axonal NiV antigen aggregation in hamsters may be related findings to what we observe here in marmosets [39].

Marmosets may provide a new NHP model to study severe disease caused by NiV. These findings are notable given many of the logistical advantages afforded by working with marmosets in the context of high-biocontainment human respiratory pathogens. Although there can be disadvantages to working with marmosets—a susceptibility to hepatic steatosis in captivity, sensitivity to anesthesia, limited blood volume, and fewer host-specific reagents—they offer distinct advantages relative to the current standard NHP model of NiV infection, AGMs, due to their small size and ease of handling, typically lower costs, and ease of cohousing. Given the unique transcriptional profile in the brainstem of the only marmoset that showed neurologic clinical manifestations, there is a need for additional follow-up with a larger cohort of both infected and uninfected marmosets to determine the incidence of neurological signs and whether the unique transcriptome in the brainstem is consistently seen. More detailed pathogenicity studies are required to monitor levels of viremia, as well as evaluate different routes of infection to potentially allow in-depth studying of neuroinvasion. Overall, marmosets were highly susceptible to infection via the IN/IT route resulting in a 100% mortality in nonprotected animals.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Christian S Stevens, Department of Microbiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, USA.

Jake Lowry, Animal Resource Center, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Terry Juelich, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Colm Atkins, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Kendra Johnson, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Jennifer K Smith, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Maryline Panis, Department of Microbiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, USA; Department of Microbiology, New York University, New York, New York, USA.

Tetsuro Ikegami, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Benjamin tenOever, Department of Microbiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, USA; Department of Microbiology, New York University, New York, New York, USA.

Alexander N Freiberg, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA.

Benhur Lee, Department of Microbiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, USA.

Notes

Acknowledgments . We thank the University of Texas Medical Branch Animal Resource Center for husbandry support of laboratory animals. Figures were created with BioRender.com.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers U19 AI171403 to B. L. and A. F, and T32 AI07647 Viral-Host Pathogenesis Training to C. S.).

References

- 1. Looi L-M, Chua K-B. Lessons from the Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia. Malays J Pathol 2007; 29:63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Howley PM, Knipe DM, Whelan SPJ, Fields BN, eds. Fields virology. Vol. 1, Emerging viruses. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee B, Broder CC, Wang L-F. Henipaviruses: Hendra and Nipah viruses. In: Howley PM, Knipe DM, Whelan SPJ, Fields BN eds. Fields virology. Vol. 1 Emerging viruses. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2021:559–95. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goh KJ, Tan CT, Chew NK, et al. Clinical features of Nipah virus encephalitis among pig farmers in Malaysia. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, Montgomery JM, et al. Clinical presentation of Nipah virus infection in Bangladesh. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:977–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, et al. Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12:235–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Homaira N, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, et al. Nipah virus outbreak with person-to-person transmission in a district of Bangladesh, 2007. Epidemiol Infect 2010; 138:1630–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Geisbert TW, Daddario-DiCaprio KM, Hickey AC, et al. Development of an acute and highly pathogenic nonhuman primate model of Nipah virus infection. PLoS One 2010; 5:e10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnston SC, Briese T, Bell TM, et al. Detailed analysis of the African green monkey model of Nipah virus disease. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0117817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prasad AN, Agans KN, Sivasubramani SK, et al. A lethal aerosol exposure model of Nipah virus strain Bangladesh in African green monkeys. J Infect Dis 2020; 221(Suppl 4):S431–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lo MK, Feldmann F, Gary JM, et al. Remdesivir (GS-5734) protects African green monkeys from Nipah virus challenge. Sci Transl Med 2019; 11:eaau9242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mire CE, Geisbert JB, Agans KN, et al. Use of single-injection recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vaccine to protect nonhuman primates against lethal Nipah virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis 2019; 25:1144–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prasad AN, Woolsey C, Geisbert JB, et al. Resistance of cynomolgus monkeys to Nipah and Hendra virus disease is associated with cell-mediated and humoral immunity. J Infect Dis 2020; 221(Suppl 4):S436–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geisbert TW, Mire CE, Geisbert JB, et al. Therapeutic treatment of Nipah virus infection in nonhuman primates with a neutralizing human monoclonal antibody. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6:242ra82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Geisbert JB, Borisevich V, Prasad AN, et al. An intranasal exposure model of lethal Nipah virus infection in African green monkeys. J Infect Dis 2020; 221(Suppl 4):S414–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu J, Coffin KM, Johnston SC, et al. Nipah virus persists in the brains of nonhuman primate survivors. JCI Insight 2019; 4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee JH, Hammoud DA, Cong Y, et al. The use of large-particle aerosol exposure to Nipah virus to mimic human neurological disease manifestations in the African green monkey. J Infect Dis 2020; 221(Suppl 4):S419–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lara A, Cong Y, Jahrling PB, et al. Peripheral immune response in the African green monkey model following Nipah-Malaysia virus exposure by intermediate-size particle aerosol. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019; 13:e0007454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cong Y, Lentz MR, Lara A, et al. Loss in lung volume and changes in the immune response demonstrate disease progression in African green monkeys infected by small-particle aerosol and intratracheal exposure to Nipah virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11:e0005532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marianneau P, Guillaume V, Wong KT, et al. Experimental infection of squirrel monkeys with Nipah virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2010; 16:507–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hammoud DA, Lentz MR, Lara A, et al. Aerosol exposure to intermediate size Nipah virus particles induces neurological disease in African green monkeys. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0006978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mire CE, Satterfield BA, Geisbert JB, et al. Pathogenic differences between Nipah virus Bangladesh and Malaysia strains in primates: implications for antibody therapy. Sci Rep 2016; 6:30916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gómez Román R, Wang L-F, Lee B, et al. Nipah@20: lessons learned from another virus with pandemic potential. mSphere. 2020; 5:e00602-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pelissier R, Iampietro M, Horvat B. Recent advances in the understanding of Nipah virus immunopathogenesis and anti-viral approaches. F1000Research 2019; 8:1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marmoset Genome Sequencing and Analysis Consortium . The common marmoset genome provides insight into primate biology and evolution. Nat Genet 2014; 46:850–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Okano H, Hikishima K, Iriki A, Sasaki E. The common marmoset as a novel animal model system for biomedical and neuroscience research applications. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2012; 17:336–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yun T, Park A, Hill TE, et al. Efficient reverse genetics reveals genetic determinants of budding and fusogenic differences between Nipah and Hendra viruses and enables real-time monitoring of viral spread in small animal models of henipavirus infection. J Virol 2021; 89:1242–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Partek Inc . Partek® Flow® (version 10.0).2020. https://www.partek.com/. Accessed 26 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Howe KL, Achuthan P, Allen J, et al. Ensembl 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 2021; 49:D884–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. QUBES . FastQC,2015.https://qubeshub.org/resources/fastqc. Accessed 1 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021; 10:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas PD, Kejariwal A, Guo N, et al. Applications for protein sequence-function evolution data: mRNA/protein expression analysis and coding SNP scoring tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2006; 34(Web Server):W645–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One 2011; 6:e21800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ge SX, Jung D, Yao R. ShinyGO: a graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 2020; 36:2628–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kippert A, Trajkovic K, Fitzner D, Opitz L, Simons M. Identification of Tmem10/opalin as a novel marker for oligodendrocytes using gene expression profiling. BMC Neurosci 2008; 9:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sjöstedt E, Zhong W, Fagerberg L, et al. An atlas of the protein-coding genes in the human, pig, and mouse brain. Science 2020; 367:eaay5947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uhlen M, Oksvold P, Fagerberg L, et al. Towards a knowledge-based human protein atlas. Nat Biotechnol 2010; 28:1248–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Karlsson M, Zhang C, Méar L, et al. A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci Adv 2021; 7:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Munster VJ, Prescott JB, Bushmaker T, et al. Rapid Nipah virus entry into the central nervous system of hamsters via the olfactory route. Sci Rep 2012; 2:736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wignall-Fleming EB, Hughes DJ, Vattipally S, et al. Analysis of paramyxovirus transcription and replication by high-throughput sequencing. J Virol 2019; 93:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cox RM, Krumm SA, Thakkar VD, Sohn M, Plemper RK. The structurally disordered paramyxovirus nucleocapsid protein tail domain is a regulator of the mRNA transcription gradient. Sci Adv 2017; 3:e1602350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cox R, Plemper RK. The paramyxovirus polymerase complex as a target for next-generation anti-paramyxovirus therapeutics. Front Microbiol 2015; 6:459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rao PL, Gandham RK, Subbiah M. Molecular evolution and genetic variations of V and W proteins derived by RNA editing in avian paramyxoviruses. Sci Rep 2020; 10:9532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lo MK, Harcourt BH, Mungall BA, et al. Determination of the henipavirus phosphoprotein gene mRNA editing frequencies and detection of the C, V and W proteins of Nipah virus in virus-infected cells. J Gen Virol 2009; 90:398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.