ABSTRACT

Mycobacterium kansasii (Mk) is an opportunistic pathogen that is frequently isolated from urban water systems, posing a health risk to susceptible individuals. Despite its ability to cause tuberculosis-like pulmonary disease, very few studies have probed the genetics of this opportunistic pathogen. Here, we report a comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mk genome. Deep sequencing of a high-density library of Mk Himar1 transposon mutants revealed that 86.8% of the chromosomal thymine–adenine (TA) dinucleotide target sites were permissive to insertion, leaving 13.2% TA sites unoccupied. Our analysis identified 394 of the 5,350 annotated open reading frames (ORFs) as essential. The majority of these essential ORFs (84.8%) share essential mutual orthologs with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). A comparative genomics analysis identified 139 Mk essential ORFs that share essential orthologs in four other species of mycobacteria. Thirteen Mk essential ORFs share orthologs in all four species that were identified as being not essential, while only two Mk essential ORFs are absent in all species compared. We used the essentiality data and a comparative genomics analysis reported here to highlight differences in essentiality between candidate Mtb drug targets and the corresponding Mk orthologs. Our findings suggest that the Mk genome encodes redundant or additional pathways that may confound validation of potential Mtb drugs and drug target candidates against the opportunistic pathogen. Additionally, we identified 57 intergenic regions containing four or more consecutive unoccupied TA sites. A disproportionally large number of these regions were located upstream of pe/ppe genes. Finally, we present an essentiality and orthology analysis of the Mk pRAW-like plasmid, pMK1248.

IMPORTANCE

Mk is one of the most common nontuberculous mycobacterial pathogens associated with tuberculosis-like pulmonary disease. Drug resistance emergence is a threat to the control of Mk infections, which already requires long-term, multidrug courses. A comprehensive understanding of Mk biology is critical to facilitate the development of new and more efficacious therapeutics against Mk. We combined transposon-based mutagenesis with analysis of insertion site identification data to uncover genes and other genomic regions required for Mk growth. We also compared the gene essentiality data set of Mk to those available for several other mycobacteria. This analysis highlighted key similarities and differences in the biology of Mk compared to these other species. Altogether, the genome-wide essentiality information generated and the results of the cross-species comparative genomics analysis represent valuable resources to assist the process of identifying and prioritizing potential Mk drug target candidates and to guide future studies on Mk biology.

KEYWORDS: Mycobacterium kansasii, gene essentiality, transposon mutagenesis, TnSeq, nontuberculous mycobacteria, mycobacterial orthology analysis, comparative mycobacterial gene essentiality, mycobacterial comparative genomics, pRAW-like plasmid, plasmid-encoded ESX system, tuberculosis, mycobacterial drug targets, antitubercular target candidate, mycobacterial ESX secretion system, type VII secretion system, nucleoid-associated protein

INTRODUCTION

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are a broad group of bacteria related to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB). Many species of NTM are clinically relevant as opportunistic pathogens and, unlike Mtb, these pathogens can persist in the environment (1, 2). Among the NTM most commonly isolated from patients is Mycobacterium kansasii (Mk), a slow-growing opportunistic pathogen that can cause tuberculosis-like pulmonary disease in individuals that are immunocompromised or have other conditions considered risk factors for opportunistic mycobacterial infections, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and malignancy (3 - 9).

Most Mk primary lung infections are likely acquired by exposure to aerosolized environmental bacteria. Mk is frequently isolated from tap water and other urban water systems (10 - 13), the hypothesized primary pathogen reservoirs generating aerosolized bacteria and presenting a constant health risk for those susceptible to infection. Person-to-person transmission has not been reported. However, some studies suggest that it might be possible, and the potential emergence of strains with epidemiologically meaningful person-to-person transmission capacity is a concern (14).

Paralleling the drug treatments against the lung disease caused by members of the Mtb complex, the standard treatments for Mk infection are multidrug regimens that are expensive, long-term, and often hampered by adverse side effects (15 - 19). These factors contribute to reduced treatment compliance, which along with the rise of Mk isolates resistant to the first-line antimycobacterial drug rifampin (20), lead to increased rates of treatment failure (16, 17). In all, there is a clear need for new and more effective antimicrobial drugs to combat Mk infection. This need is further underscored by the potential rise of multidrug-resistant Mk strains as a collateral outcome of the pervasive use of anti-TB drugs in high TB burden areas of the world.

Of note, although Mk is currently classified into seven subtypes (I–VII), several recent studies using sequencing- and transcriptome-based approaches have proposed reclassifying these subtypes as closely related species (21 - 23). Subtype I is by far the most prevalent in human isolates and retains the species name Mycobacterium kansasii in these reclassification proposals. Besides laying the foundation for updating the molecular taxonomy of Mk, these studies have highlighted the observation made previously that Mk shares many recognized virulence determinants with Mtb (24). Indeed, Mk is one of the NTM most closely related to the Mtb complex, and it has been suggested that Mtb evolved into an obligate pathogen from an Mk-like environmental opportunistic pathogen (25). These observations might lend support to the use of Mk as one of the model organisms to help expand our understanding of the evolution and biology of the Mtb complex.

Despite the clinical relevance of Mk as one of the most pathogenic NTM, its biology remains largely underexplored. In particular, there is a noticeable paucity of literature reporting direct genetic manipulation of Mk to study gene function (26 - 30). Encouragingly, the completion of the Mk genome sequence was reported in 2015 (24). Thus, some aspects of Mk gene function, including gene essentiality, may be inferred from bioinformatics and extrapolation of insights gained for Mtb (24, 25), the main reference for comparative genomics of mycobacterial pathogens. However, while highly useful surrogates in the absence of bona fide experimental data, in silico approaches do not provide a complete picture and can often lead to flawed conclusions. These are germane considerations given that the 6.55 Mb Mk genome (chromosome plus a pRAW-like plasmid, pMK12478) (24) is ~50% larger than that of Mtb (31).

Without a doubt, experimentation focused on Mk is clearly necessary. In particular, genome-wide studies aimed at dissecting Mk gene essentiality will significantly expand our understanding of Mk biology and bring to light new potential drug target candidates. With these considerations in mind, we recently investigated and validated the applicability of the ϕMycoMarT7 phage-based specialized transduction method for Himar1 transposon (Tn) mutagenesis in Mk and provided proof-of-principle for its use in combination with Tn insertion sequencing (TnSeq) (26, 32). This earlier work set the stage for the use of a saturation Tn mutagenesis–TnSeq approach to study gene essentiality in Mk, as done in several other species of mycobacteria (33 - 36). In this study, we performed a large-scale TnSeq analysis of a high-density library of Mk Tn mutants to predict genetic determinants required for in vitro growth. We also used comparative genomics and available gene essentiality data for Mtb (a slow-growing obligate pathogen) and the NTM Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis (MAH, a slow-growing opportunistic pathogen), Mycobacterium abscessus (Mab, a rapidly growing opportunistic pathogen), and Mycobacterium smegmatis (Msm, a nonpathogenic rapidly growing species) to illuminate similarities and differences between the biology of these mycobacteria. Our analysis reported herein provides insights into the biology of Mk, informs future directions to prioritize studies on potential drug target candidates and avenues to novel therapeutics against Mk infections, and highlights possible biological underpinnings of Mk drug susceptibility characteristics.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Insertion statistics and essentiality status of TA sites

We performed TnSeq analysis on 12 independent libraries of Mk Tn mutants grown on Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates. Each library contained an average of approximately 200,000 mutant colonies. These libraries, totaling over 2.5 million colonies, yielded an average of 11 million unique Tn–genome junctions (template counts) per library (Table S1). The Mk genome consists of a 6,432,277-bp chromosome with 97,702 TA sites and a 144,951-bp plasmid (pMK12478) containing 2,251 TA sites. Thus, the aggregated library analyzed corresponded to a 25-fold coverage relative to the number of TA sites in the genome. Insertions were evenly distributed throughout both the chromosome and the plasmid (Fig. 1 and 2). The TA site insertion saturation (defined as the ratio of the number of TA sites with at least one mapped insertion to the total number of TA sites) for individual libraries ranged from 44.8% to 67.0% (Fig. 3). Cumulatively, 87.0% of the 99,953 TA sites in the genome (chromosome + plasmid) contained at least one insertion in the aggregated data set. This equated to 86.8% and 96.6% cumulative TA site insertion saturation for the chromosome and the plasmid, respectively. For clarity, we note that, unless otherwise indicated, further analysis addressed in the ensuing text is focused on the chromosome, rather than on the plasmid, for which a dedicated section is presented below.

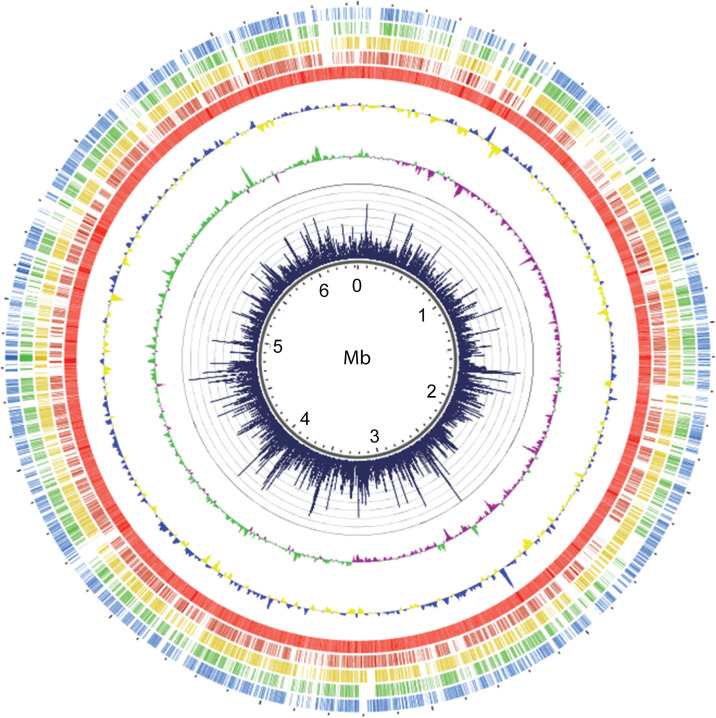

Fig 1.

Visualization of the M. kansasii chromosome showing insertion counts, orthology data, and various sequence features. Tracks from innermost: (1) chromosome backbone with ruler; (2) insertion count plot with the height of the black bars representing the number of raw insertion counts at each TA site (minimum = 0, maximum = 45,000); (3) GC skew (green represents richness of G over C, purple represents richness of C over G; (4) GC content (blue represents above average GC content, yellow represents below average GC content); (5) M. kansasii annotated genes (bright red); (6) M. tuberculosis orthologs of Mk open reading frames (ORFs) (dark red); (7) M. avium subsp. hominissuis orthologs (yellow) of Mk ORFs; (8) M. abscessus orthologs (green) of Mk ORFs; and (9) M. smegmatis orthologs (blue) of Mk ORFs.

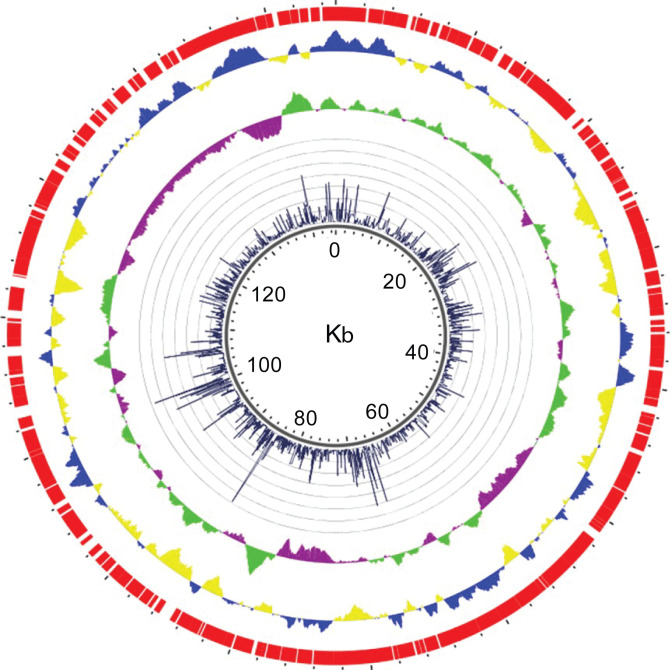

Fig 2.

Visualization of the M. kansasii plasmid pMK12478 showing insertion counts and various sequence features. Tracks are as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Insertion count plot minimum = 0, maximum = 37,000.

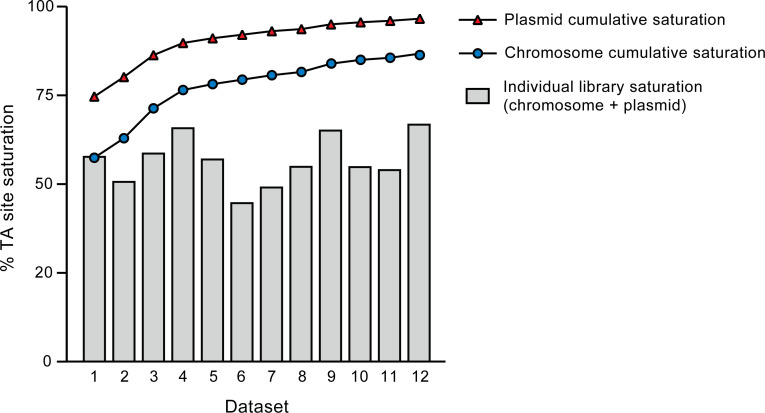

Fig 3.

TA site insertion saturation. Each data set represents TnSeq results from a single-plated library. Gray bars show the overall saturation levels (chromosome + plasmid) of individual data sets. The solid lines represent the cumulative densities of the chromosome (circles) and plasmid (triangles) obtained by adding one data set at a time. Each data set was generated by harvesting and processing plated libraries as described in Materials and Methods. Briefly, colonies from a single library were scraped from the surface of 7H10 agar, and genomic DNA was extracted from the mutant pool. Genomic DNA was fragmented, fragment ends were repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to T-tailed adapters containing random nucleotide barcodes. PCR enrichment of fragments containing Tn-chromosome junctions using a Tn-specific primer and an adapter-specific primer was followed by the selection of fragments between 400 and 600 bp via gel electrophoresis and then a second hemi-nested PCR amplification using tailed primers to introduce Illumina-specific sequences. The resulting fragment libraries were sequenced on the Illumina platform, obtaining at least 30 million 100-bp paired-end reads per sample. Reads were processed and mapped onto the Mk chromosome and the Mk plasmid pMK12478 using the TPP tool in TRANSIT.

The insertion data sets from 12 libraries were analyzed collectively in TRANSIT using the hidden Markov model (HMM) to assign the most probable essentiality state call to each TA site (37 - 40). This statistical model incorporates neighboring TA site read counts when assigning each TA site its essentiality state call, thus producing a locally consistent assignment of essentiality state calls across the genome. The TA essentiality state calls assigned by the HMM are essential (ES, being near zero read count), nonessential (NE, being near the mean read count), growth defect (GD, being near 1/10 of the mean), and growth advantage (GA, being near 5× the mean). In this way, the HMM is capable of identifying not only TA sites within essential regions of the genome but also those sites in regions resulting in an apparent reduction (GD) or improvement (GA) in fitness when disrupted. The use of TnSeq data to accurately predict changes in fitness associated with Tn insertions has been experimentally validated (41) and represents an advantage of the HMM component of TRANSIT over other available models for assessing the essentiality of intragenic and extragenic regions of bacterial genomes. It is worth noting that, like any other method of TnSeq analysis for predicting gene essentiality, TRANSIT has advantages and disadvantages (35, 37 - 40). Still, TRANSIT remains a well-accepted and powerful tool for gene essentiality studies with the Himar1 Tn in the mycobacterial field.

Of the 12,899 chromosomal TA sites (13.2%) to which no insertions were mapped in our aggregate data set, 4,561 were categorized as ES by the HMM. After excluding the TA sites with ES state assignments from analysis, the overall saturation for the chromosome increases to 90.8% from 86.8% (Table 1). Additionally, our analysis identified 8.7% (8,456 TA sites) of all TA sites as fitting the nonpermissive (NP) motif for Tn insertion as defined by Dejesus et al. (35). Such TA sites are less permissible for insertion compared to TA sites not fitting the NP motif. This percentage of NP TA sites is comparable to that observed in the essentiality analysis of the Mtb genome, in which 9% of the TA sites fit the NP motif (35). Taking these TA sites matching the NP motif into consideration, the overall saturation increases to 94.6% from 90.8% (Table 1), leaving only 4,500 TA sites (4.6%) that were not labeled ES, did not fit the NP motif, and did not contain at least one insertion in our aggregated data set. Given the high saturation of our library, it is improbable that these many sites are not occupied in the aggregated data set purely by chance. It is more likely that these sites reside in essential regions of the genome but were not labeled ES due to the features of the HMM component of TRANSIT (see below). Overall, when applied to our TnSeq data, HMM defined 7.0% of TA sites as ES, 78.6% as NE, 2.3% as GD, and 12.1% as GA (Data set S1). Notably, this distribution of TA site essentiality state calls is very similar to that observed in essentiality analysis of the rapidly growing NTM M. abscessus genome (33).

TABLE 1.

Insertion count statistics of M. kansasii chromosomal TA sites

| TA site category | No. of sites | % of sitesc | % of saturationd | NZ meane |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 97,702 | – | 86.8 | 144.5 |

| Predicted to not be essential by HMMa | 90,873 | 93.0 | 90.8 | 148.5 |

| Predicted to not be essential not matching NPb motif | 83,010 | 85.0 | 94.6 | 153.8 |

| All TA sites matching NP motif | 8,456 | 8.7 | 48.0 | 44.2 |

| All TA sites not matching NP motif | 89,246 | 91.3 | 90.5 | 149.6 |

Essentiality assessment using the hidden Markov model (HMM) and performed in TRANSIT (38) using TnSeq data.

Nonpermissive TA sites for Himar1 insertion as defined by Dejesus et al. (35).

Percentage of all TA sites represented by category.

Percentage of TA sites in category with at least one insertion.

Mean read count of nonzero (NZ) TA sites in the category.

Essentiality analysis of annotated genes

The essentiality state calls of TA sites were the basis for the essentiality analysis of the annotated genes in the Mk genome. Using TRANSIT, each gene was assigned the majority state call of the TA sites within its boundaries. The results of our essentiality analysis of annotated genes are presented in Table 2 and Data set S1. Genes lacking TA sites (n = 19) were not assessable and therefore were labeled N/A. A total of 76 genes featured a single TA site, 131 had two TA sites, and 232 contained three TA sites. While it can be challenging to assess the essentiality state of genes containing so few TA sites because of the possibility that TA sites lack insertions in the aggregate data set due to chance, only 14 genes belonging to these three groups totaling 439 genes were identified as ES by TRANSIT. Of the 5,350 annotated open reading frames (ORFs) in the Mk genome, 394 (7.4%) were identified as ES and 139 (2.6%) as GD (Table 2; Data set S1), representing a combined set of 533 (10.0%) ORFs that are required for optimal growth in vitro. As for the remaining ORFs, 649 (12.1%) were identified as GA and 4,153 (77.6%) as NE.

TABLE 2.

Summary of essentiality analysis of M. kansasii chromosome by TnSeq

| Genomic featurea | No. of genomic features by assigned essentiality statusb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ES | GD | GA | NE | N/A | |

| ORFs | 5,350 | 394 | 139 | 649 | 4,153 | 15 |

| tRNAs | 46 | 10 (40) c | 0 (1) | 5 (1) | 27 (0) | 4 |

| rRNAs | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ncRNA | 2 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 |

| miscRNAd | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

As per the National Center for Biotechnology Information annotation (GenBank: NC_022663.1).

ES, essential; GD, growth defect; GA, growth advantage; NE, nonessential; N/A, not assessable due to the lack of TA sites.

Numbers in parentheses are totals based on gene final essentiality state calls determined by manual scrutiny of TA site insertion data (see Data set S4 ).

miscRNA, miscellaneous RNA.

Comparative landscape of gene essentiality and orthology across M. kansasii and other mycobacteria

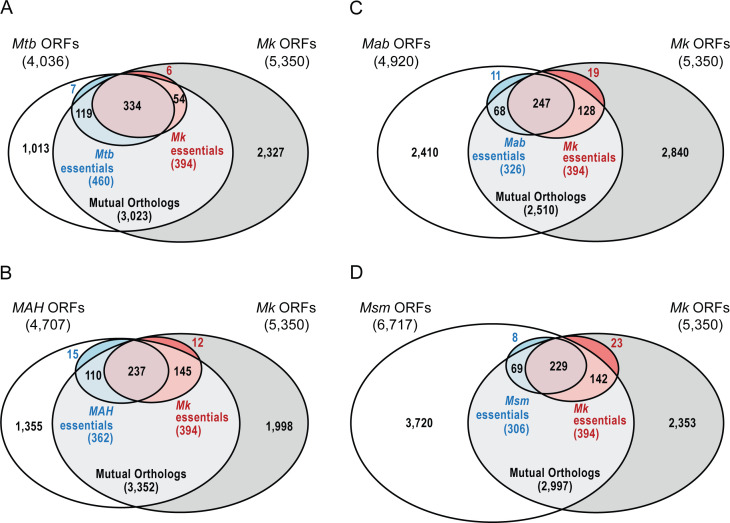

We carried out pair-wise comparative genomics analysis to identify Mk ORFs that share mutual orthologs with either Mtb, MAH, Mab, or Msm. We note that the GView BLAST search results returned ORFs that were not present in the published essentiality data sets used for Mtb (18 ORFs) (35) and MAH (54 ORFs) (34). Further details on these ORFs and the corresponding essentiality state calls used for the purpose of this study can be found in the Materials and Methods section. Our comparative genomics analysis found that a total of 1,910 (35.7%) Mk ORFs shared mutual orthologs with all species compared, whereas 1,187 (22.2%) Mk ORFs did not share mutual orthologs with any of the four species compared. The orthology data were cross-referenced with available essentiality data for each species (Fig. 4; Table 3; Data set S2 ). A total of 139 essential Mk ORFs shared mutual orthologs predicted to be essential in all four species compared (Data set S3). Many of these ORFs correspond to genes involved in processes critical for survival such as DNA replication, transcription, translation, cell wall maintenance, and amino acid biosynthesis. Among this group of 139 common essential ORFs are genes encoding targets of drugs currently used for treating mycobacterial infections such as embAB (ethambutol’s target), inhA (isoniazid’s target), rpoB (rifampicin’s target), as well as genes encoding the targets of antitubercular compounds in various stages of development, including dprE1 (macozinone’s target), murX (capuramycin’s target), kasA (indazole sulfonamide’s target), and leuS (oxaboroles’ target) (42).

Fig 4.

Venn diagrams illustrating in vitro essential ORFs of M. kansasii compared to other mycobacteria species. Mutual orthologs were identified using Gview server as described in Materials and Methods. (A) M. tuberculosis essential ORFs defined by Dejesus et al. (35). (B) M. avium subsp. hominissuis essential ORFs defined by Dragset et al. (34). (C) M. abscessus essential ORFs defined by Rifat et al. (33). (D) M. smegmatis essential ORFs defined by Dragset et al. (36). Venn diagrams were generated in R using the Eulerr package and edited in Adobe Illustrator.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of essentiality and M. kansasii orthology across species

Interestingly, 13 Mk ES ORFs shared mutual orthologs that are not essential (NE, GD, or GA) in all four species compared (Table 4). Among these ORFs uniquely essential in Mk, the ES status of secA2 is of particular interest. Mycobacterial genomes encode two paralogs of SecA, the ATPase component of the major bacterial protein secretory system. In bacteria containing both SecA1 and SecA2, the former provides an essential function by exporting the majority of the bacterial secretome, whereas the latter typically becomes essential only under in vivo conditions and exports a smaller set of the secretome, including proteins involved in virulence (43, 44). While the available essentiality data suggest this model is generally correct for mycobacteria, our unexpected finding that the genes encoding both SecA paralogs are essential in Mk indicates that SecA2 might play a more critical function in Mk biology. SecA2 and other products of genes that are uniquely essential in Mk represent potential targets for Mk-specific drugs.

TABLE 4.

M. kansasii essential ORFs sharing mutual orthologs,a identified as not essential in M. tuberculosis,b M. avium subsp. hominissuis,c M. abscessus,d and M. smegmatise

| Locus tag | Gene name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| MKAN_RS00320 | secA2 | Accessory Sec system translocase SecA2 |

| MKAN_RS14925 | – | Cation-translocating P-type ATPase |

| MKAN_RS16715 | – | Hypothetical protein |

| MKAN_RS17105 | thiD | Bifunctional hydroxymethylpyrimidine/phosphomethylpyrimidine kinase |

| MKAN_RS18455 | rpmG | 50S ribosomal protein L33 |

| MKAN_RS18980 | – | zf-HC2 domain-containing protein |

| MKAN_RS22360 | – | Cysteine desulfurase |

| MKAN_RS22365 | mnmA | tRNA 2-thiouridine(34) synthase MnmA |

| MKAN_RS22965 | – | DUF177 domain-containing protein |

| MKAN_RS23125 | rpsP | 30S ribosomal protein S16 |

| MKAN_RS23140 | trmD | tRNA (guanosine(37)-N1)-methyltransferase TrmD |

| MKAN_RS23630 | cobA | Uroporphyrinogen-III C-methyltransferase |

| MKAN_RS24245f | – | DUF3093 domain-containing protein |

Identified using Gview Server as described in Materials and Methods.

As defined by Dejesus et al. (35).

As defined by Dragset et al. (34).

As defined by Rifat et al. (33).

As defined by Dragset et al. (36).

Scrutiny of insertion and state call data (Data set S1) for MKAN_RS24245 revealed that three out of the six TA sites in the ORF fit the NP motif, a confounder with the potential to reduce the robustness of the ES prediction.

Seven Mk ORFs identified as being nonessential share mutual orthologs that are essential in all species compared (Table 5). Among these is nadD, encoding a nicotinate-nucleotide adenylyltransferase. The predicted essentiality of nadD for in vitro growth has been experimentally validated for Msm, where the nadD knockdown has been shown to have a bacteriostatic effect secondary to the depletion of the NAD(H) cofactor pool in the mutant (45). The unexpected prediction of Mk nadD as NE by our TRANSIT analysis might indicate that the Mk genome encodes nicotinate-nucleotide adenylyltransferase paralogs or metabolic pathway alternatives absent in the compared species that allow the bacterium to bypass the requirement of nadD for in vitro growth. It is worth noting, however, that our scrutiny of insertion and state call data (Dataset S1) for nadD revealed a low value for the mean normalized read count at nonzero sites (five TA sites with insertions out of seven) conceptually more consistent with a GD or ES classification of the ORF than the NE classification by TRANSIT. The NE call by TRANSIT might have been heavily influenced by the insertion pattern surrounding the ORF. Interestingly, the same observation can be made for whiA (MKAN_RS25620) (Table 5). We also note that no obvious paralogs of nadD or whiA are present in Mk. Experimental research will be required to ascertain the essentiality status of Mk nadD and whiA conclusively. Lastly, 1,187 Mk ORFs share no mutual orthologs with any species compared. Most of these (1,045) were identified as NE, while only two, encoded by MKAN_RS27135 and MKAN_RS30405, were identified as ES. Both genes are predicted to encode hypothetical proteins of unknown function.

TABLE 5.

M. kansasii ORFs identified as not essential sharing mutual orthologsa identified as essential in M. tuberculosis,b M. avium subsp. hominissuis,c M. abscessus,d and M. smegmatise

| Locus tag | State callf | Gene name | Gene product description |

|---|---|---|---|

| MKAN_RS04970g | NE | nadD | Nicotinate-nucleotide adenylyltransferase |

| MKAN_RS25620h | NE | whiA | DNA-binding protein WhiA |

| MKAN_RS14030 | GD | – | CCA tRNA nucleotidyltransferase |

| MKAN_RS16635 | GD | dnaK | Molecular chaperone DnaK |

| MKAN_RS17640 | GD | – | Glutamyl-tRNA reductase |

| MKAN_RS22580 | GD | – | D-alanine–D-alanine ligase |

| MKAN_RS24890 | GD | – | Glycosyltransferase family 4 protein |

Orthologs identified using Gview Server as in Materials and Methods.

As defined by Dejesus et al. (35).

As defined by Dragset et al. (34).

As defined by Rifat et al. (33).

As defined by Dragset et al. (36).

GD, growth defect; NE, nonessential.

Scrutiny of insertion and state call data (Data set S1) for MKAN_RS04970 revealed a low value for the mean normalized read count at nonzero sites (five TA sites with insertions out of seven) conceptually more consistent with a GD or ES classification of the ORF than the NE prediction by TRANSIT.

Inspection of insertion and state call data for MKAN_RS25620 showed five unoccupied TA sites (out of six in the ORF) and a low value for the mean normalized read count at nonzero sites conceptually consistent with an ES call rather than with the NE classification by TRANSIT.

Candidate M. tuberculosis essential drug targets that are not essential in M. kansasii

Our results indicate that Mk has roughly 15% fewer in vitro essential ORFs than Mtb. This finding, paired with the observation that the Mk genome is ~50% larger than that of Mtb, suggests that there are fundamental differences in physiology between the two pathogens, which, in turn, might translate into yet unrecognized differences in susceptibility to antitubercular drugs and drug candidates between the two species.

In support of this view, the gene thyX, which encodes one of the targets of the second-line antitubercular drug p-aminosalicylic acid (PAS), to which Mtb is susceptible but Mk is intrinsically resistant (17, 46, 47), was identified as NE by our analysis. PAS acts as a prodrug targeting the folate biosynthesis pathway by inhibiting the dihydrofolate reductase encoded by folA (dfrA) (48). A recent study has shown that PAS is a multitarget drug, also inhibiting the flavin-dependent thymidylate synthase encoded by thyX (49). While folA is labeled GD in both Mtb (Rv2763c) and Mk (MKAN_RS23945), thyX is labeled ES in Mtb (Rv2754c) (35) but NE in Mk (MKAN_RS23975). Thus, the intrinsic resistance of Mk to PAS is accompanied by a lack of requirement for the gene encoding one of the targets of the antitubercular agent. Future studies are warranted to probe the link between the NE status of Mk thyX and the resistance of the bacterium to PAS, a drug with a mechanism of action that remains incompletely understood.

One potential explanation for the reduced proportion of essential genes in Mk relative to Mtb is that the larger genome of the former encodes functionally redundant genes or pathways that are absent in the smaller genome of the latter. Functional redundancies have been observed in Mtb (50 - 53) and have occasionally confounded the validation of antitubercular agents (54). Therefore, it is possible that any additional layers of redundancy in the Mk genome could confound the prediction of drug targets in Mk made by the extrapolation of Mtb knowledge and hinder the activity of antitubercular agents validated in Mtb against Mk. To probe this possibility, we mined the results of our comparative genomics analysis and essentiality study to predict potential differences in drug target candidates between Mtb and Mk. In the ensuing text, we highlight candidate Mtb essential drug targets sharing mutual orthologs with Mk that we identified as nonessential. These findings indicate the presence of additional pathways or proteins that negate these drug target candidates in Mk and may have implications for the decision-making process shaping the drug candidate evaluation pipeline against this pathogen.

Among the noticeable discrepancies in gene essentiality between Mk and Mtb with possible implications for drug development are the essentiality assertions for genes encoding proteins of the proteasome machinery, a critical component of the Mtb proteostasis network (55, 56). Gene-silencing experiments indicate that while the Mtb proteasome is not essential under standard liquid-culturing conditions in vitro, it is required for optimal growth on agar plates and for growth and persistence in mice (57, 58). These findings have made the Mtb proteasome an attractive target for the development of anti-TB drugs (59 - 61). In Mtb, genes prcA (Rv2109c) and prcB (Rv2110c) encoding the proteasome subunits PrcA and PrcB, respectively, as well as Rv3780 encoding the bacterial proteasome activator/accessory factor PafE, were identified as ES (35). Our essentiality analysis, which was carried out using the same solid medium as that of the Mtb study, identified MKAN_RS02165 and MKAN_RS02170, encoding Mk PrcA and PrcB, respectively, as NE, while the MKAN_RS13390, encoding Mk PafE, was identified as GA. Notably, however, none of the three Mk genes appear to have identifiable paralogs in the genome. Thus, our findings might suggest that Mk possesses at least one alternative pathway or compensatory mechanism not present in Mtb that is sufficient to fulfill the essential protein degradation needs experienced by the cell during growth in solid medium in the absence of a conventional mycobacterial proteasome assembly. Whether or not this pathway(s)/mechanism(s) is sufficient to render these Mk proteasome genes dispensable during the conditions encountered in a mammalian host remains to be determined.

Another promising anti-TB drug target candidate is the serine/threonine protein kinase A (PknA), which phosphorylates proteins involved in many critical mycobacterial cell processes such as mycolic acid synthesis, peptidoglycan synthesis, and cell division (62). The Mtb gene pknA (Rv0015c) has been shown to be indispensable for survival in the host using a conditional knockout mutant in a mouse model (63) and identified as ES for in vitro growth by TnSeq-based essentiality analysis (35). Of note, a recent large-scale screen of Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs for Mtb PknA inhibitors identified existing vitamin B2-based drugs as candidates to feed the pipeline of preclinical studies on the PknA target (64). In contrast to the finding of the TnSeq-based essentiality analysis in Mtb, our data revealed that Mk pknA (MKAN_RS14245) disruption provides a growth advantage rather than a loss of viability (Data set S1). Although the Mtb and Mk genomes encode several serine/threonine protein kinases, Mk does not appear to have any additional PknA paralog that could explain the difference in essentiality between the two pathogens. Besides pknA, the only other serine/threonine protein kinase identified as essential in Mtb is pknB (35). Interestingly, we found that Mk pknB (MKAN_RS1440) was not essential for growth, but its disruption led to a growth defect (Data set S1). It is worth noting that in Mtb, PknA and PknB regulate the activity of the proteasome by phosphorylating the core subunits PrcA and PrcB (65), suggesting that the disagreements in the gene essentiality call for pknA, pknB, and proteasome subunit encoding genes prcA and prcB of Mtb and Mk might be linked to fundamental differences in the way the two pathogens manage their respective proteostasis networks.

Our analysis also suggests differences in potential target candidates for drugs disrupting energy metabolism. Type II NADH-dehydrogenase (NDH-2) plays a critical role in bacterial energy metabolism as it catalyzes the transfer of electrons from NADH to the respiratory chain (66, 67). The Mtb genome contains two NDH-2 genes, ndh (Rv1854c) and ndhA (Rv0392c), encoding NDH-2 and NDH-2A, respectively. Early gene knockout studies in Mtb found that ndh could not be inactivated without an additional copy of the gene present (68), while a more recent study showed that successful deletion of ndh results in a growth defect in vitro (69). In contrast, ndhA could be inactivated without compromising growth (68, 69). The absence of an NDH-2 ortholog in mammals has made it an attractive target for new antibiotics, and several chemical library screens have identified inhibitors of the mycobacterial NDH-2 (42, 70 - 73). Essentiality analysis in Mtb identified ndh as GD and ndhA as NE (35), supporting the findings from the gene knockout studies. Our analysis identified MKAN_RS00490 (encoding the Mk ortholog of NDH-2) and MKAN_RS16920 (encoding the Mk ortholog of NDH-2A) as NE and GA, respectively. This may represent a potential difference in energy metabolism between Mk and Mtb. Both species contain the nonessential proton-pumping type I NADH-dehydrogenase (NDH-1) encoded by nuoA-G. While data suggest that NDH-1 is unable to complement the loss of NDH-2 function in Mtb (70), it is possible that NDH-1 and/or NDH-2A can better compensate the loss of NDH-2 in Mk.

Nonessential MKAN_RS23135 encodes ribosome maturation factor RimM, which shares mutual orthologs identified as GD in all four species compared. Data obtained from analysis of RimM knockout mutants (74) and mutational analyses of ribosomal components in E. coli (75), along with kinetic experiments (76), indicate that RimM plays an important role in ribosome biosynthesis in bacteria. The observation that a rimM gene knockout significantly impacts bacterial growth (77) and that humans lack an ortholog of RimM has led to recent studies of the protein as a potential drug target in Mtb. These studies have provided the structural basis for Mtb RimM–ribosomal protein S19 interaction and predicted the druggability of the resulting complex (78). Again, we found no apparent paralogs of RimM in the Mk genome to explain the lack of requirement of its gene for wild-type growth in vitro. Thus, our analysis suggests that RimM may not be a viable drug target for combatting infections by the opportunistic pathogen.

Many species of bacteria, including Mtb, utilize the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway to synthesize isopentenyl pyrophosphate and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate, which are the precursors to isoprenoids (79). The roles of isoprenoids in a wide variety of critical mycobacterial cellular functions and a lack of the MEP pathway in humans have led to investigations into the druggability of the pathway in Mtb. The genes encoding the seven enzymes in the MEP pathway (Rv2682c/1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase [DXS], Rv2870c/IspC, Rv3582c/IspD, Rv1011/IspE, Rv3581c/IspF, Rv2868/IspG, Rv1110/IspH) were identified as ES in Mtb (35), and thus each represents a potential drug target. However, the biochemical properties of some of these enzymes have complicated the design of inhibitors, and as a result, DXS, IspC, and IspF have emerged as the most promising targets in the MEP pathway (80). In Mk, the mutual orthologs of DXS and IspC, MKAN_RS24340 and MKAN_RS23400, respectively, were identified as ES, while the mutual ortholog of IspF, MKAN_RS11675, was identified as GA. Therefore, among the inhibitors of potential drug targets in the Mtb MEP pathway, those designed to target IspF may not be active against Mk. It should be noted that in the case of ispF and the gene rimM (discussed above), most insertions mapped to TA sites toward the 3′-end of the ORFs. It remains possible that the insertions compromised only the C-terminus of the gene products and render functional proteins. Thus, the essentiality call by TRANSIT might be confounded and it is possible that these genes are indeed essential. Unambiguous experimental validation of the essentiality status of these genes is needed.

The Mtb essential gene desA1 (Rv0824c) encodes an acyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase that has been identified as a high-confidence drug target by an in silico target identification pipeline (81). Studies using the model organism M. smegmatis have elucidated the role of DesA1 in the desaturation step of mycolic acid biosynthesis and have highlighted its potential as a new antitubercular target (82, 83). Mtb DesA1 shares a mutual ortholog in Mk, encoded by MKAN_RS10190 (henceforth referred to as Mk DesA1), which was identified as GA. The presence of an apparent paralog of Mk DesA1 in the Mk genome encoded by the NE gene MKAN_RS04740 (sharing 77.8% identity with Mk DesA1) may explain this lack of requirement of DesA1 in Mk. This may have implications for the validation of drugs targeting DesA1 in Mk.

Essentiality of non-protein-coding genes

The Mk genome contains 46 tRNA genes, of which 10 were predicted as ES by TRANSIT (Table 2; Data set S4). Somewhat unexpectedly, these essential genes included only two of the eight singleton tRNA genes, tRNA-Asp (MKAN_RS10135) and tRNA-Phe (MKAN_RS10140). Additionally, there are several cases where only one of the multiple copies of the tRNA genes for a given amino acid was classified as ES (i.e., Ala, Glu, Gly, Ile, Lys, Met, Thr, and Val tRNAs). This pattern of essentiality for tRNA genes is similar to what was reported for Mab (33) but differs from what was observed in Mtb, in which 21 of the 35 tRNA genes with at least two TA sites were classified as ES (35). Notably, manual scrutiny of our TA site insertion and essentiality call data for the Mk tRNA genes along with the equivalent data in the Mtb study revealed a similar pattern in both data sets. There were many instances where the TA sites within the boundary of tRNA genes are devoid of insertions (or have marginal read counts), but these sites were labeled NE by HMM. Given that the gene essentiality state given by the software is called based on the labeling of the majority of TA sites within the gene, we would expect such tRNA genes to be labeled NE in both species. The fact that many of these Mtb tRNA genes were reported as being ES leads us to believe that the ES classification might have emerged from a sensible manual curation performed by the authors. This “miscalling” of TA sites by HMM stems from an occasionally disadvantageous feature of the software tool, where short stretches of TA sites are forced into a state call based on the information from surrounding TA sites. Since tRNA genes tend to be relatively short and have few TA sites, their essentiality state calls are particularly susceptible to the state call information from the surrounding TA sites. Taking this all into consideration, the essentiality landscape of Mk tRNA genes appears to be similar to that of Mtb in that the majority of these genes should be considered ES. This essential status would not be surprising given the role of tRNAs in translation and other critical cellular processes (84). It is worth considering that the miscalling of the essentiality status of TA sites might have confounded some of the tRNA gene essentiality classifications in published work using the TRANSIT tool. In fact, this appears to be the case in the classification of tRNA genes reported in the Mab essentiality study (33) as per our examination of the published TA site insertion and essentiality call data sets.

The three ribosomal RNA genes, MKAN_RS06025 (5S rRNA gene), MKAN_RS06030 (23S rRNA gene), and MKAN_RS06035 (16S rRNA gene), as well as MKAN_RS29940 (ssrA), predicted to encode the transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA) of the trans-translation system, and MKAN_RS29660 (ffs), predicted to encode the small-RNA component of the signal recognition particle ribonucleoprotein complex, were identified as ES. It should be noted that ffs contains only a single TA site, and thus there is a chance that the gene is not truly essential. Interestingly, unlike Mk ssrA, Mtb ssrA has been classified as NE by TnSeq-based analysis (35), a finding in conflict with the essential status assigned to the Mtb gene based on the observation that it could not be deleted without the presence of a second functional ssrA copy integrated elsewhere in the genome (85). Our closer analysis of the Mtb TA site essentiality data from which the NE status of Mtb ssrA was determined revealed that the analysis was performed with a now outdated annotation of ssrA that incorrectly made the gene 239 bp longer compared to the current annotation. The erroneous annotation placed five TA sites permissive to insertion within the boundaries of the gene. The currently annotated shorter Mtb ssrA, however, is the same length as its Mk ortholog, and all the TA sites within the gene boundaries are defined as ES as per the Mtb TA site essentiality data (35). Therefore, we conclude that Mtb ssrA should be listed as ES, a revision of status that clears up the discrepancy between the reported Mtb essentiality analysis and the observation of the Mtb ssrA deletion studies.

Essentiality of intergenic regions

18,673 TA sites (~19%) of those in the chromosome are in regions outside of annotated genes. We scanned these intergenic regions for segments containing runs of four or more consecutive unoccupied TA sites (referred hereafter to as CUTA segments); that is, no insertions are mapped to these sites in the aggregated data set. This criterion to define CUTA segments is comparable to the operational criterion to define essential regions in the Mtb essentiality analysis (35). CUTA segments were identified in 57 intergenic regions of the Mk chromosome, and only 13 of them included TA sites fitting the NP motif (Data set S5). Surprisingly, only six of the CUTA segments were adjacent to the 5′-end of essential genes, while the majority were adjacent to the 5′-end of nonessential genes. Further, 21 of the CUTA segments were between divergently oriented nonessential genes. While the presence of CUTA segments adjacent to the 5′-end of essential genes could be due to the Tn insertion-derived disruption of gene transcription, the CUTA segments adjacent to the 5′-end of nonessential genes require a different explanation. One possible mechanism leading to these CUTA segments could be the coating of the DNA by DNA-binding proteins that block transposition into the TA sites, a phenomenon decoupling the lack of insertions at those TA sites from site essentiality status. This speculation is supported by the finding that nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs, a.k.a. bacterial chromatin proteins or histone-like proteins) that preferentially coat AT-rich sequences have been shown to hinder Tn insertion at their binding sites (86, 87). On the other hand, a second mechanism could be envisioned in which insertion at these TA sites is unobstructed and leads to loss of cell viability due to the disruption of the binding of NAPs or other proteins needed for suppressing deleterious (over)expression or misexpression of the adjacent nonessential gene. In this mechanism, unlike the first one noted, the lack of insertion will remain linked to the TA site essentiality status of the intergenic region.

NAPs are known to influence the expression of hundreds of genes in bacterial genomes, often by impacting the architecture of the bacterial chromatin (88, 89). In particular, several NAPs have been identified in mycobacteria that share orthologs in Mk (EspR, Lsr2, HupB, mIHF, and NapA/M) as per our comparative genomics analysis. Some of these NAPs preferentially bind AT-rich sequences, such as those found in promoter regions, and repress gene expression through DNA coating and/or introduction of local structural changes in the DNA (90 - 92). For example, the mycobacterial NAP Lsr2 preferentially binds regions with an AT content of ~53% or more, a percentage well above the 33%–35% average for mycobacterial genomes. In fact, the intergenic regions containing CUTA segments have an average AT content of 43%, which is higher than that across the entire Mk chromosome (24). It has been observed that in bacterial genomes, intergenic regions generally contain higher AT content than intragenic regions, but this difference is less marked in mycobacteria (93, 94).

Interestingly, 14 of the CUTA segments identified were located adjacent to the 5′-end of genes encoding members of the PE/PPE protein families (Data set S5), a group of mycobacterial secreted proteins involved in a wide range of processes, including iron uptake, adaptation to stress, and virulence (95 - 97). The Mk chromosome is predicted to encode 72 PE and 141 PPE proteins (24). Interestingly, while these 213 genes account for only ~4% of the genes of the genome, they were found downstream of about 25% of the CUTA segments (Data set S5). The NAP Lsr2 has been shown to regulate the expression of a large number of pe/ppe genes in Mtb (90, 92, 98). Two of these genes are the cotranscribed Rv3622c and Rv3621c encoding PE32/PPE65, which have been shown to be involved in modulating the antimycobacterial host immune response (99). Mtb PE32/PPE65 share mutual orthologs in Mk encoded by MKAN_RS11920/MKAN_RS11915, which are adjacent to an identified CUTA segment. This finding provides conceptual support for the possibility that, as speculated above, Mk NAPs might bind to some of the CUTA segments identified by our analysis. Lastly, currently unrecognized non-coding RNA (ncRNA)/small RNA (sRNA) coding genes or regulatory elements such as riboswitches may also explain the presence of CUTA segments. Research to investigate the molecular underpinnings of these segments will expand our insight into the biology of Mk.

Essentiality analysis of the plasmid

Mk ATCC 12478 contains pMK12478 (GenBank: NC_022654.1), a pRAW-like plasmid similar to those present in other slow-growing mycobacteria (100). Our analysis mapped insertions to 96.6% of the 2,251 TA sites on the plasmid. Of these sites, HMM classified 0.7% (15) as ES, 86.0% (1,935) as NE, 2.5% (57) as GD, and 10.8% (244) as GA (Data set S6). When TA sites labeled ES (15) and those fitting the NP motif (143) are taken into consideration, the insertion saturation increases to 98.0%. This leaves only 41 TA sites (2.0%) that were not labeled ES, did not fit the NP motif, and did not contain at least one insertion in our aggregated data set.

Of the 145 annotated ORFs for pMK12478, one was identified as ES, two as GD, 121 as NE, and 21 as GA by TRANSIT (Data set S6). The single essential gene on the plasmid, MKAN_RS28235, contained all of the 15 TA sites that were defined as ES (Data set S6). The essential call for MKAN_RS28235 could signify that disruption of the gene compromised plasmid maintenance, cell growth, or both. However, the observation that some Mk (subtype I) clinical isolates do not contain the plasmid suggests that MKAN_RS28235 is not required for growth (24). Moreover, our BLAST analysis indicated that the gene might encode a protein with nucleotidyltransferase activity, a property that has been documented for several plasmid replication proteins (101, 102). Thus, the lack of the plasmid in several Mk strains and the results of the BLAST analysis suggest that MKAN_RS28235 is likely to be required for plasmid maintenance.

We performed a comparative analysis to identify mutual orthologs between pMK12478 and the pRAW-like plasmid pMD2 from MAH strain 11 (78 kb, 66 ORFs, GenBank: CM009839.1) (Data set S7), for which TnSeq and TRANSIT-derived essentiality data became available recently (34). Of the 49 mutual orthologs identified by our analysis, 47 were assigned the same essentiality state call in the two species (Data set S7). The orthology analysis did not identify an ortholog of the ES MKAN_RS28235 in pMD2. However, BLAST analysis revealed that proteins identical to that encoded by MKAN_RS28235 are present in several other mycobacterial plasmids, including pMAC109a of MAH strain 109 (GenBank: NZ_CP029333.1). A recent MAH 109 essentiality analysis using a rank-based filter procedure (103) identified the MKAN_RS28235 ortholog, DFS55_RS24595 (formerly DFS55_24600), as ES. As in the case of MKAN_RS28235, it is likely that DFS55_RS24595 is required for plasmid maintenance.

The two GD genes identified on pMK12478, MKAN_RS28290 and MKAN_RS29045, are both predicted to encode hypothetical proteins and share mutual orthologs on pMD2. The ortholog of MKAN_RS28290 on pMD2 is the GD gene B6K05_25320 (Data set S7). BLAST analysis shows that MKAN_RS28290 also has an ortholog on pMAC109a, DFS55_RS24640 (formerly DFS55_24645), that was identified as ES (103). The proteins encoded by MKAN_RS28290, B6K05_25320, and DFS55_RS24640 each share 53% amino acid sequence identity with the putative replication protein RepA encoded by the gene MAH_p01 found in the pRAW-like plasmid pMAH135 of MAH strain TH135 (GenBank: AP012556.1 [104]), for which no essentiality data are available. The identification of MKAN_RS28290 and its orthologs as GD or ES genes likely indicates that their disruption compromises plasmid maintenance.

The other GD gene, MKAN_RS29045, shares a NE mutual ortholog on pMD2, B6K05_25280. BLAST analysis revealed that MKAN_RS29045 shares 64% amino acid sequence identity with the protein L842_6123 of Mycobacterium intracellulare (strain MIN_052511_1280, GenBank: JAON01000021.1), which is annotated as encoding a type III secretion system outer membrane O domain protein. MKAN_RS29045 shares an identical ortholog on pMAC109a, encoded by DFS55_RS25835. There are no essentiality data available for this gene, which was not yet annotated in the record used for the corresponding essentiality analysis (103). However, our examination of the corresponding TA site essentiality data showed suppressed insertion counts at the gene locus, a finding suggesting the classification of DFS55_RS25835 as a GD gene.

Interestingly, a relatively large intergenic region (828 bp) between the divergent NE MKAN_RS29040 and MKAN_RS28325 genes showed a run of 18 consecutive TA sites defined as GD. MKAN_RS28325 is directly upstream of the GD MKAN_RS29045 gene, and it is predicted to encode a member of the ParA protein family, a group of proteins known to be required for proper plasmid segregation during cell division (105, 106). The MKAN_RS28325 ortholog on pMD2, B6K05_25285, was also identified as NE, whereas the ortholog on pMAC109a, DFS55_RS24675 (formerly DFS55_24680), was identified as ES. Our analysis of the essentiality data for the pMAC109a region corresponding to the GD intergenic region identified upstream of MKAN_RS28325 also showed suppressed TA site insertion counts (103). Interestingly, our RNA sequencing data from Mk total RNA (not shown) indicate that there is transcription at this intergenic region. Still, we were not able to identify a likely gene product by BLAST analysis of the region. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that the intergenic region is important for plasmid maintenance.

Nine of the 21 pMK12478 GA genes share mutual orthologs with pMD2 that were also identified as GA. Interestingly, these nine genes belong to two distinct loci. One locus has a cluster of five consecutive genes (MKAN_RS28130-MKAN_RS 28150) that are part of a putative mycobacterial type VII protein secretion (ESX) system. Such ESX loci present on pRAW-like plasmids have been shown to be required for plasmid conjugation (100). The other four GA genes are also arrayed consecutively (MKAN_RS28295-MKAN_RS 28310). One of these genes encodes a PPE domain-containing protein (MKAN_RS28300), a second encodes a putative ESX system secretion target (MKAN_RS28305), and the other two genes (MKAN_RS28295 and MKAN_RS28310) encode hypothetical proteins. It is worth noting that the genes clustered in the two GA loci of pMK12478 appear to be conserved in pRAW-like plasmids (100), and the ESX locus is also present on pMAC109a. It remains unclear whether the GA state call for pMK12478 genes signifies that the disruption of the genes leads to an increase in the number of plasmids per cell, a growth advantage, or both.

Conclusions

Despite the clinical relevance of Mk as one of the most pathogenic NTM and the need for new and more effective drugs to combat Mk infections, very few studies have probed the genetics of this slow-growing opportunistic pathogen. Here, we report the first comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mk genome via saturation Tn mutagenesis. Our analysis, using 2.5 million Mk Tn mutant colonies across 12 independent plated libraries, reached an effective saturation of 94.6% of the 97,702 TA sites in the Mk chromosome. This level of saturation allowed us to obtain high-confidence essentiality state calls of the TA sites and annotated genes of the Mk genome and enabled us to compare our data to essentiality data available for other species of mycobacteria generated using similar methods.

Our comparative genomic analysis identified 139 genes that are essential in Mk, Mtb, MAH, Mab, and Msm. These included genes encoding targets of validated antitubercular drugs as well as targets of candidate drugs in various stages of preclinical development. The analysis also predicted unique in vitro genetic requirements that distinguish Mk from the other species of mycobacteria. Noteworthy were genes uniquely essential to Mk, such as secA2, encoding an accessory secretory system translocase, as the products of these genes may represent potential Mk-specific drug targets.

Importantly, our analysis highlighted candidate Mtb essential drug targets that are not essential in Mk. The lack of genetic requirement of the genes encoding these targets may have implications for the validation of drug candidates in the antitubercular drug development pipeline against Mk and underscores physiological differences between Mk and Mtb. Additional physiological differences between Mk and Mtb are seen by comparing the genetic requirement of the genes of the ESX loci across species (Data set S8). The Mk genome contains all five ESX loci present in the Mtb genome. For the most part, the genetic requirement of the loci is the same in Mk and Mtb. The ESX-3 locus is involved in iron and zinc homeostasis (107) and is the only locus identified as ES for in vitro growth in both organisms. In contrast, the ESX-5 membrane component genes eccB5, eccC5, eccD5, and eccE5 were all identified as GD in Mtb but were classified as ES in Mk. The ESX-5 locus has been shown to modulate the macrophage response in slow-growing M. marinum (108) and appears to be the only cluster that is present in all slow-growing mycobacteria yet absent in all rapidly growing mycobacteria analyzed so far (109). An Mtb ESX-5 mutant in which eccD5 was inactivated has been generated and was shown to display a wide range of phenotypes, including impaired secretion of ESX-5 substrates, reduced cell wall integrity, increased sensitivity to hydrophilic antibiotics, and attenuated growth in two infection models (110). Our essentiality data suggest the phenotypic effects resulting from disruption of one of the ESX-5 membrane components are more severe in Mk than in Mtb under in vitro conditions.

Our extended examination of essentiality data for TA sites in intergenic regions revealed several chromosomal regions that could contain so-far unidentified essential features or be heavily coated by DNA-binding proteins blocking transposition at these sites. Finally, the presented analysis also provided robust gene essentiality data for the Mk plasmid pMK12478 and its comparison with essentiality data available for other mycobacterial plasmids. In particular, the analysis highlighted several genes and an intergenic region potentially involved in plasmid maintenance.

Although data sets of in vitro and in vivo gene essentiality are likely to overlap only partially and there are well-known challenges in translating in vitro gene essentiality data into drug development programs, in vitro essentiality remains a well-recognized starting point in the process of potential drug target candidate identification and prioritization. Altogether, the genome-wide essentiality analysis of Mk and the results of the cross-species essentiality analysis presented herein provide novel insights into Mk biology and represent valuable resources to guide future Mk studies and to assist the process of identifying and prioritizing potential Mk drug target candidates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culturing conditions and reagents

Unless otherwise specified, Mk (reference strain ATCC 12478; Hauduroy) and Msm (strain MC2155) were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid broth (Difco, Becton-Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) supplemented with 10% ADN (5% BSA, 2% dextrose, 0.85% NaCl), 0.05% Tween-80, and 0.2% glycerol (s7H9) and in Middlebrook 7H10 or 7H11 agar media (Difco, Becton-Dickinson and Co.) supplemented with 10% OADC (0.05% oleic acid, 5% BSA, 2% dextrose, 0.003% catalase, 0.85% NaCl) and 0.5% glycerol (s7H10 and s7H11 media). Kanamycin (Km) was added when required to a final concentration of 30 µg/mL. Unless otherwise stated, reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Branchburg, NJ, USA), New England Biolabs Inc. (Ipswich, MA, USA), VWR International LLC (Radnor, PA, USA), Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA), Thomas Scientific (Swedesboro, NJ, USA), or Qiagen LLC (Germantown, MD, USA).

Construction of M. kansasii transposon mutant plated libraries

High-density Mk Tn mutant pools were prepared as described by Budell et al. (26). Msm strain MC2155 was used as a host to propagate the φMycoMarT7 bacteriophage. s7H9 broth was used to culture host cells at 37°C with shaking for 24 hours. The resulting phage stocks were titrated on s7H11 agar plates incubated at 37°C for 48–72 hours. Titrated phage stocks were used to infect Mk cultures at desired PFU-to-CFU multiplicity of infection ratios. After 4 hours of incubation at 37°C without shaking, infections were pelleted, resuspended in s7H9 broth containing 25% glycerol, and aliquoted for storage at −80°C. For each infection, a single aliquot was thawed and used for titrating CFU on s7H11 agar ± Km to determine total and Km-resistant CFU. Plated libraries for the purpose of performing TnSeq were prepared using titrated Mk-phage infections. For each library, infections were plated to obtain ~200,000 Km-resistant CFU across 25–30 150-mm Petri dishes containing s7H10 agar with Km. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 14–18 days before colony harvesting.

Tn insertion sequencing and essentiality analysis

Each library consisting of ~200,000 Mk Tn mutant colonies was processed as described by Long et al. (40). Briefly, colonies from a single library were scraped from the surface of s7H10 agar into a 50-mL conical tube. A homogeneous slurry was prepared from the cell mass by resuspension up to 30 mL in TE (Tris-EDTA) buffer. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from this mutant pool according to a standard mycobacterial gDNA isolation protocol (111). For each library, 10 µg gDNA was fragmented via ultrasonication using the Covaris E220 (Weill Cornell Genomics Core). DNA fragment ends were repaired using the End-It DNA-Repair Kit (Lucigen, LGC Biosearch Technologies Inc., Dexter, MI, USA), A-tailed with Taq-DNA polymerase (Denville Scientific Inc., South Plainfield, NJ, USA), and then ligated with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs Inc.) to T-tailed adapters containing random nucleotide barcodes (Adapters 1.2 and 2.2 BarB). PCR enrichment of fragments containing Tn-chromosome junctions using a Tn-specific primer (T7) (40) and an adapter-specific primer (JEL_AP1) (40) was followed by the selection of fragments between 400 and 600 bp via gel electrophoresis and then a second hemi-nested PCR amplification using tailed primers (SOL_AP1_tagged) (40) to introduce Illumina-specific sequences. The resulting fragment libraries were sequenced on the Illumina platform (Weill Cornell Genomics Core), obtaining at least 30 million 150-bp paired-end reads per sample. Reads were processed and mapped onto the Mk chromosome (GenBank: NC_022663.1) and plasmid pMK12478 (GenBank: NC_022654.1) using the TPP software tool in TRANSIT (38). Insertion counts obtained from TPP were then analyzed in TRANSIT using the HMM to assign a most probable essential state call to each TA site and annotated gene.

Comparative genomics

To identify mutually orthologous genes shared by Mk and Mtb H37Rv (GenBank: NC_000962.3), MAH MAH11 (GenBank: CP035744.1, aviumMD30 assembly; ASM312274v1), Mab ATCC 19977 (GenBank: CU458896.1), or Msm str. MC2 155 (GenBank: CP000480.1), GView Server was used to perform reciprocal BLAST searches between Mk and each species, with expected cutoff value, alignment length cutoff, and percent identity cutoff as 1.0E-10, 30, and 30, respectively (112). While more recent records are available for the Msm and MAH genomes, these particular accession numbers were used to facilitate downstream comparisons of essentiality between species. The orthology data along with the insertion counts from the aggregated TnSeq data from this study were visualized in the context of the Mk chromosome using the Gview application. The orthology data were cross-referenced with existing essentiality data available for each species (33 - 36). As noted in the Results section, the GView BLAST searches yielded results containing Mtb and MAH ORFs which were not present in corresponding essentiality data sets (34, 35). Closer inspection of annotated features of the corresponding genomes showed 18 such ORFs for Mtb and 54 such ORFs for MAH that are not present in the essentiality data sets. In the case of Mtb, the available TA site essentiality data (35) were used to assign an essentiality state call for each ORF (Data set S9). In the case of MAH, the essentiality state call of the ORFs were labeled N/D (not determined). The addition of these ORFs in our analysis explains why the total number of ORFs for these species differs from previous analyses. Venn diagrams were generated in the RStudio using the “Eulerr” package and then edited in Adobe Illustrator (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA). For all Mk genes specifically discussed in the Results section, the TA site insertion and state call data (Data set S1) were scrutinized to identify local features (e.g., total number of TA sites, read counts, TA sites fitting the NP motif, CUTA segments) and ensure the reliability of the gene essentiality predictions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Professor Eric Rubin (Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA) for providing a φMycoMarT7 sample, Professor Thomas Ioerger (Texas A & M University, College of Engineering, College Station, TX, USA) for his help with initial TRANSIT implementation, and Professor Jenny Xiang (Director, Genomics Resources Core Facility at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, USA) for her help with next-generation sequencing services. We are grateful to Iqura Naheed and Saba Iqbal (L.E.N.Q. Laboratory) for their help with transposon mutant library quality control. We also wish to thank Professor Dean Crick (Mycobacteria Research Laboratories, Colorado State University, CO, USA) for insightful comments and helpful discussions.

This work was supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R03 AI135755) and the endowment support from Carol and Larry Zicklin to L.E.N.Q. K.L. and N.J. were supported in part by City University of New York Doctoral Student Research Grant Program Awards.

K.L. carried out experiments; data collection; investigation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing; and figure preparation. N.J. carried out experiments; data collection; and writing—review and editing. L.E.N.Q. carried out conceptualization, supervision, investigation, funding acquisition; project administration; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing; and figure preparation.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Luis E. N. Quadri, Email: LQuadri@brooklyn.cuny.edu.

Sabine Ehrt, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, New York, USA .

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00573-23.

Sequencing statistics for the 12 replicate M. kansasii TnSeq data sets.

List of essentiality calls based on the motif-dependent Hidden Markov Model of essentiality for all TA sites and annotated genes in the M. kansasii ATCC 12478 chromosome.

M. kansasii ORFs and mutual orthologs identified in M. tuberculosis, M. avium subsp. hominissuis, M. abscessus, and M. smegmatis along with corresponding essentiality calls.

M. kansasii, M. tuberculosis, M. avium subsp. hominissuis, M. abscessus, and M. smegmatis ORF orthologs predicted to be essential.

Essentiality of M. kansasii non-ORF annotated genes.

M. kansasii intergenic regions containing four or more consecutive unoccupied TA sites (CUTA segment).

Essentiality calls based on the motif-dependent Hidden Markov Model of essentiality for all TA sites and annotated genes in the M. kansasii ATCC 12478 plasmid pMK12478.

M. kansasii pMK12478 and M. avium subsp. hominissuis pMD2 mutual orthologs along with essentiality state calls.

Essentiality of the five ESX loci in M. kansasii and M. tuberculosis.

Essentiality of M. tuberculosis genes not represented in Dejesus et al., 2017 (35).

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Prevots DR, Marras TK. 2015. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria: a review. Clin Chest Med 36:13–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henkle E, Winthrop KL. 2015. Nontuberculous mycobacteria infections in immunosuppressed hosts. Clin Chest Med 36:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston JC, Chiang L, Elwood K. 2017. Mycobacterium kansasii. Microbiol Spectr 5. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0011-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maliwan N, Zvetina JR. 2005. Clinical features and follow up of 302 patients with Mycobacterium kansasii pulmonary infection: a 50 year experience. Postgrad Med J 81:530–533. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.026229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Evans AJ, Crisp AJ, Hubbard RB, Colville A, Evans SA, Johnston ID. 1996. Pulmonary Mycobacterium kansasii infection: comparison of radiological appearances with pulmonary tuberculosis. Thorax 51:1243–1247. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.12.1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matveychuk A, Fuks L, Priess R, Hahim I, Shitrit D. 2012. Clinical and radiological features of Mycobacterium kansasii and other NTM infections. Respir Med 106:1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ehsani L, Reddy SC, Mosunjac M, Kraft CS, Guarner J. 2015. Fatal aortic pseudoaneurysm from disseminated Mycobacterium kansasii infection: case report. Hum Pathol 46:467–470. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hirashima T, Nagai T, Shigeoka H, Tamura Y, Yoshida H, Kawahara K, Kondoh Y, Sakai K, Hashimoto S, Fujishima M, Shiroyama T, Tamiya M, Morishita N, Suzuki H, Okamoto N, Kawase I. 2014. Comparison of the clinical courses and chemotherapy outcomes in metastatic colorectal cancer patients with and without active Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium kansasii infection: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer 14:770. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Queipo JA, Broseta E, Santos M, Sánchez-Plumed J, Budía A, Jiménez-Cruz F. 2003. Mycobacterial infection in a series of 1261 renal transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Infect 9:518–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ashbolt NJ. 2015. Environmental (saprozoic) pathogens of engineered water systems: understanding their ecology for risk assessment and management. Pathogens 4:390–405. doi: 10.3390/pathogens4020390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomson RM, Carter R, Tolson C, Coulter C, Huygens F, Hargreaves M. 2013. Factors associated with the isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from a large municipal water system in Brisbane, Australia. BMC Microbiol 13:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ulmann V, Kracalikova A, Dziedzinska R. 2015. Mycobacteria in water used for personal hygiene in heavy industry and collieries: a potential risk for employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12:2870–2877. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120302870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vaerewijck MJM, Huys G, Palomino JC, Swings J, Portaels F. 2005. Mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems: ecology and significance for human health. FEMS Microbiol Rev 29:911–934. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2005.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ricketts WM, O’Shaughnessy TC, van Ingen J. 2014. Human-to-human transmission of Mycobacterium kansasii or victims of a shared source? Eur Respir J 44:1085–1087. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00066614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Basille D, Jounieaux V, Andréjak C. 2018. Treatment of other nontuberculous mycobacteria. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 39:377–382. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1660473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown-Elliott BA, Nash KA, Wallace RJ. 2012. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, drug resistance mechanisms, and therapy of infections with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:545–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05030-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburgh R, Huitt G, Iademarco MF, Iseman M, Olivier K, Ruoss S, von Reyn CF, Wallace RJ, Winthrop K, ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee, American Thoracic Society, Infectious Disease Society of America . 2007. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Ingen J, Boeree MJ, van Soolingen D, Iseman MD, Heifets LB, Daley CL. 2012. Are phylogenetic position, virulence, drug susceptibility and in vivo response to treatment in mycobacteria interrelated? Infect Genet Evol 12:832–837. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Ingen J, Boeree MJ, van Soolingen D, Mouton JW. 2012. Resistance mechanisms and drug susceptibility testing of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Drug Resist Updat 15:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wallace RJ, Dunbar D, Brown BA, Onyi G, Dunlap R, Ahn CH, Murphy DT. 1994. Rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium kansasii. Clin Infect Dis 18:736–743. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.5.736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tagini F, Aeby S, Bertelli C, Droz S, Casanova C, Prod’hom G, Jaton K, Greub G. 2019. Phylogenomics reveal that Mycobacterium kansasii subtypes are species-level lineages. description of Mycobacterium pseudokansasii sp. nov., Mycobacterium innocens sp. nov. and Mycobacterium attenuatum sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 69:1696–1704. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guan Q, Ummels R, Ben-Rached F, Alzahid Y, Amini MS, Adroub SA, van Ingen J, Bitter W, Abdallah AM, Pain A. 2020. Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses of Mycobacterium kansasii subtypes provide new insights into their pathogenicity and taxonomy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:122. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jagielski T, Borówka P, Bakuła Z, Lach J, Marciniak B, Brzostek A, Dziadek J, Dziurzyński M, Pennings L, van Ingen J, Žolnir-Dovč M, Strapagiel D. 2019. Genomic insights into the Mycobacterium kansasii complex: an update. Front Microbiol 10:2918. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang J, McIntosh F, Radomski N, Dewar K, Simeone R, Enninga J, Brosch R, Rocha EP, Veyrier FJ, Behr MA. 2015. Insights on the emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the analysis of Mycobacterium kansasii. Genome Biol Evol 7:856–870. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Veyrier F, Pletzer D, Turenne C, Behr MA. 2009. Phylogenetic detection of horizontal gene transfer during the step-wise genesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Evol Biol 9:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Budell WC, Germain GA, Janisch N, McKie-Krisberg Z, Jayaprakash AD, Resnick AE, Quadri LEN. 2020. Transposon mutagenesis in Mycobacterium kansasii links a small RNA gene to colony morphology and biofilm formation and identifies 9,885 intragenic insertions that do not compromise colony outgrowth. Microbiologyopen 9:e988. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klein JL, Brown TJ, French GL. 2001. Rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium kansasii is associated with rpoB mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:3056–3058. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.3056-3058.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Onwueme KC, Vos CJ, Zurita J, Soll CE, Quadri LEN. 2005. Identification of phthiodiolone ketoreductase, an enzyme required for production of mycobacterial diacyl phthiocerol virulence factors. J Bacteriol 187:4760–4766. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4760-4766.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun Z, Zhang Y. 1999. Reduced pyrazinamidase activity and the natural resistance of Mycobacterium kansasii to the antituberculosis drug pyrazinamide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:537–542. doi: 10.1128/AAC.43.3.537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nataraj V, Pang P, Haslam SM, Veerapen N, Minnikin DE, Dell A, Besra GS, Bhatt A. 2015. MKAN27435 is required for the biosynthesis of higher subclasses of lipooligosaccharides in Mycobacterium kansasii. PLoS One 10:e0122804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream M-A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Janisch N, Levendosky K, Budell WC, Quadri LEN. 2023. Genetic underpinnings of carotenogenesis and light-induced transcriptome remodeling in the opportunistic pathogen Mycobacterium kansasii. Pathogens 12:86. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12010086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rifat D, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Nuermberger EL. 2021. Genome-wide essentiality analysis of Mycobacterium abscessus by saturated transposon mutagenesis and deep sequencing. mBio 12:e0104921. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01049-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dragset MS, Ioerger TR, Loevenich M, Haug M, Sivakumar N, Marstad A, Cardona PJ, Klinkenberg G, Rubin EJ, Steigedal M, Flo TH. 2019. Global assessment of Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis genetic requirement for growth and virulence. mSystems 4:e00402-19. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00402-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. DeJesus MA, Gerrick ER, Xu W, Park SW, Long JE, Boutte CC, Rubin EJ, Schnappinger D, Ehrt S, Fortune SM, Sassetti CM, Ioerger TR. 2017. Comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome via saturating transposon mutagenesis. mBio 8:e02133-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02133-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dragset MS, Ioerger TR, Zhang YJ, Mærk M, Ginbot Z, Sacchettini JC, Flo TH, Rubin EJ, Steigedal M. 2019. Genome-wide phenotypic profiling identifies and categorizes genes required for mycobacterial low iron fitness. Sci Rep 9:11394. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47905-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dejesus MA, Ioerger TR. 2013. A hidden Markov model for identifying essential and growth-defect regions in bacterial genomes from transposon insertion sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 14: 303. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DeJesus MA, Ambadipudi C, Baker R, Sassetti C, Ioerger TR. 2015. TRANSIT - a software tool for Himar1 TnSeq analysis. PLoS Comput Biol 11:e1004401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ioerger TR. 2022. Analysis of gene essentiality from TnSeq data using Transit. Methods Mol Biol 2377:391–421. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1720-5_22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]