Abstract

From 2010 to 2014, CDC and the Office of Population Affairs at the USDHHS collaborated on the development of clinical recommendations for providing quality family planning services. A high priority was placed on the use of existing scientific evidence in developing the recommendations, in accordance with IOM guidelines for how to develop “trustworthy” clinical practice guidelines. Consequently, a series of systematic reviews were developed using a transparent and reproducible methodology aimed at ensuring that the clinical practice guidelines would be based on evidence collected in the most unbiased manner possible. This article describes the methodology used in conducting these systematic reviews, which occurred from mid-2011 through 2012.

Introduction

From 2010 to 2014, CDC and the Office of Population Affairs (OPA) at the USDHHS collaborated on the development of clinical recommendations for providing quality family planning services.1 A high priority was placed on the use of existing scientific evidence in developing the recommendations, in accordance with IOM standards for how to develop “trustworthy” clinical practice guidelines.2 One of the eight standards explicitly focuses on the use of systematic reviews (Standard 4); it notes that developers of guidelines should use rigorous methodologies for conducting the systematic reviews, and that the guideline development group and systematic review team should interact regarding the scope, approach, and output of the processes.2 The IOM noted that too often, clinical guidelines are based on incomplete reviews of the evidence, which can greatly influence the final recommendations.2–4

Consequently, a series of systematic reviews were developed using a transparent and reproducible methodology aimed at ensuring that the clinical practice guidelines would be based on evidence collected in the most unbiased manner possible. The purpose of this paper is to describe the methodology used in conducting these systematic reviews, which was composed of the following steps: defining the scope and approach of the review, developing analytic frameworks and key questions, establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria, developing the literature search strategy, retrieving the literature and abstracting data, assessing the internal and external validity of included studies, and producing the evidence report. Other aspects of developing the guidelines are published separately. In particular, an overview of the goals of the effort,5 as well as the results of each systematic review,6–14 are published in this journal supplement. The list of core recommendations and rationale for each are found in the recommendations document itself.1

Description

The methodology used to produce each of the systematic reviews that underpin the clinical recommendations for quality family planning services was modeled on that used by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).15 The review process consists of the following steps: defining the scope and approach of the review, developing analytic frameworks and key questions, establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria, developing the literature search strategy, retrieving the literature and abstracting the data, assessing the internal and external validity of included studies, and producing the evidence report.

Defining the Scope and Approach of the Review

At the beginning of the guideline development process, an Expert Work Group was created to advise OPA and CDC on the purpose and audience of the revised recommendations, and to provide input designed to ensure that the recommendations were feasible and relevant to the needs of family planning providers and their clients. The Expert Work Group consisted of family planning clinical providers, program administrators, representatives from relevant Federal agencies, and representatives from professional medical organizations. This group made an early recommendation to focus systematic reviews on four priority areas considered key components of family planning service delivery: counseling and education, serving adolescents, quality improvement, and community outreach. Other topics were considered (e.g., postpartum contraception, the reproductive health needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender [LGBT] individuals), but there was general agreement that given the available resources the other topics could be addressed in future iterations of the guidelines. OPA and CDC made final decisions, based on individual feedback received from the Expert Work Group. It was also decided that the results of each systematic review would be presented to subject matter experts who would assist in the interpretation of findings, and to provide input on the recommendations that could be developed from the evidence.

Developing Analytic Frameworks and Key Questions

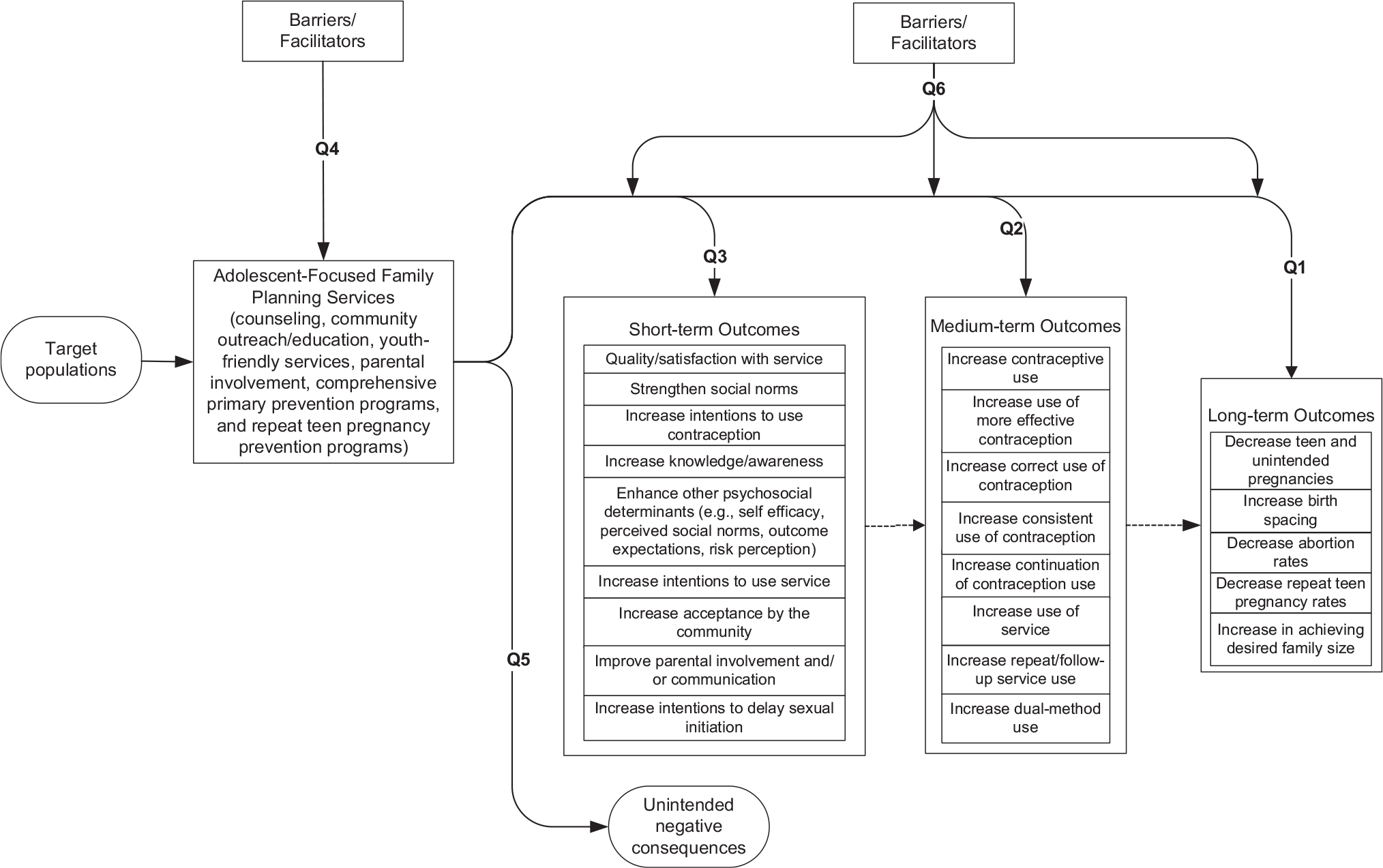

For each systematic review, an analytic framework was developed to show the logical relationships among the populations, interventions, and outcomes of interest. Short-term outcomes examined in each review included clients’ knowledge, attitudes, or other determinants of behavior. Medium-term outcomes of interest included client behaviors such as contraceptive use, use of contraceptive methods with lower failure rates, correct and consistent use of contraception, continuation of use, returning to the clinic for follow-up services, and dual-method contraceptive use. Long-term outcomes included decreased rates of pregnancy, abortion, and births among female adolescents.

Each systematic review addressed several key questions (Table 1). The first three key questions examined whether there was a relationship between programs designed to strengthen (the topic of the systematic review) and improved long- (Key Question 1); medium- (Key Question 2); and short- (Key Question 3) term outcomes. Key Questions 4–6 focused on implementation of the intervention of interest and examined issues such as barriers and facilitators to clinic implementation (Key Question 4); the unintended consequences of its implementation (Key Question 5); and barriers and facilitators to uptake/adoption by clients (Key Question 6).

Table 1.

Key Questions and Inclusion Criteria

| Key question no. | Question | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1 | Is there a relationship between programs designed to strengthen [topic of systematic review] and improved long-term outcomes (e.g., decreased teen and unintended pregnancies, increased birth spacing, decreased abortion rates, decreased repeat teen pregnancy rates, increase in achieving desired family size)? | • Article must describe a study that attempted to directly determine whether adolescent-focused family planning services (as defined by CDC) impacts at least one long-term or short-term outcome |

| 2 | Is there a relationship between programs designed to strengthen [topic of systematic review] and improved medium-term outcomes (e.g., increased contraceptive use, increased use of more effective contraception, increased correct use of contraception, increased consistent use of contraception, increased continuation of contraception use, increased use of service, increased repeat/follow-up service use, increased dual-method use)? | • Article must describe a study that includes a comparison that compared intervention of interest to no intervention or other intervention or, if the study does not include a comparison group, pre-exposure measures pertaining to the outcomes of interest or change scores must be available • Study must have enrolled individuals falling between the ages of 10 and 24 and results must be presented separately for this population • Article must describe a study that attempted to determine if adolescent-focused family planning services (as defined by CDC) impact at least one short-term outcomes • Article must describe a study that includes a comparison that compared intervention of interest to no intervention or other intervention or, if the study does not include a comparison group, pre-exposure measures pertaining to the outcomes of interest or change scores must be available • Study must have enrolled individuals falling between the ages of 10 and 24 and results must be presented separately for this population |

| 3 | Is there a relationship between programs designed to strengthen [topic of systematic review] and improved short-term outcomes (e.g., quality/satisfaction with service, strengthen social norms, intention to use contraception, knowledge, other psychosocial determinants, intentions to use service, awareness, acceptance by the community, increase parental involvement and/or communication)? | • Article must describe a study that examined the effect of adolescent-focused family planning services (as defined by CDC) • Article must describe barriers/facilitators to clinics to adopting and implementing adolescent-focused family planning services |

| 4 | What are the barriers and facilitators to clinics to adopting and implementing programs designed to strengthen [topic of systematic review]? | • Article must describe negative unintended outcomes/ consequences of adolescent-focused family planning services (as defined by CDC) • Study must have enrolled individuals falling between the ages of 10 and 24 years, and results must be presented separately for this population |

| 5 | Are there unintended negative consequences associated with providing programs designed to strengthen [topic of systematic review]? | • Article must describe a study that examined the effect of adolescent-focused family planning services (as defined by CDC) • Article must describe barriers/facilitators facing clients in using family planning services and implementing birth control plans • Study must have enrolled individuals falling between the ages of 10 and 24 years, and results must be presented separately for this population |

| 6 | What are the barriers and facilitators to adolescent clients to participating in programs designed to strengthen [topic of systematic review]? | • Article must describe a study that attempted to directly determine whether adolescent-focused family planning services (as defined by CDC) impacts at least one long-term or short-term outcome • Article must describe a study that includes a comparison that compared intervention of interest to no intervention or other intervention or, if the study does not include a comparison group, pre-exposure measures pertaining to the outcomes of interest or change scores must be available • Study must have enrolled individuals falling between the ages of 10 and 24 years, and results must be presented separately for this population |

Figure 1 is an example of an analytic framework that was developed for the systematic reviews focused on adolescent services.6,7,11 The solid lines in the analytic framework show the relationship between the intervention and the outcomes, and dashed lines show logical relationships between outcomes (i.e., a change in short-term outcomes can logically be assumed to lead to a change in medium-term outcomes, and a change in medium-term outcomes might logically be expected to lead to a change in long-term outcomes). The numbered lines in the analytic framework map onto the key questions addressed by the evidence reviews.

Figure 1.

Analytic framework for evidence reports: example from review of adolescent services.

Establishing Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Retrieval and inclusion criteria were developed a priori. Retrieval criteria were identical across systematic reviews and included the following: published between January 1, 1985, and February 28, 2011; published in the English language; article must describe a study that speaks to at least one of the key questions addressed by the evidence report; all articles must be full-length (abstracts and letters to the editor did not meet the inclusion criteria); and if the same study was reported in multiple publications, the most complete publication was considered the primary reference. The analyses of the data occurred from mid-2011 through 2012.

The inclusion criteria depended on the key question being addressed; however, the primary intent was to identify studies of interventions for which there was some form of comparison group, that utilized a quantitative approach to documenting intervention impact (Key Questions 1–3; Table 1 provides an example of inclusion criteria developed for the reviews on adolescent services).6,7,11 Qualitative and descriptive data were included for Key Questions 4–6, which addressed implementation challenges and unanticipated consequences. However, the inclusion criteria varied by specific topics. For example, adolescent review articles were not included if the intervention being tested was entirely sex education because the effect of these programs has already been well documented in several other systematic reviews.16–18 In addition, articles were not included if they focused solely on HIV/sexually transmitted disease prevention without a focus on pregnancy prevention. The articles describing the results of each review contain information about any other inclusion criteria specific to that review.

Developing the Literature Search Strategy

We examined the following electronic databases to identify articles that might contain information pertinent to the key questions addressed in the evidence report: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PubMed (pre-MEDLINE), PsycINFO, HealthSTAR, POPLINE, EMBASE, ERIC, The Campbell Library, The Cochrane Library, the database of abstracts of reviews of effects (DARE), United Kingdom (UK) National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database, U.S. National Guideline Clearinghouse, UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence, Evidence for Policy and Practice Information database of excellence, and TRIP. Search strategies were developed for each topic area, which included the identification of key terms that were specific to each topic and the database. When possible, controlled vocabulary terms were used (e.g., Medical Subject Headings). The specific search terms used for each topic are presented in the respective papers included in this journal supplement.6–14,19

Retrieving the Literature and Abstracting the Data

The searches were implemented, and the aforementioned retrieval criteria were used to review the resulting abstracts and determine whether a full-length version of an article should be ordered and reviewed. Each retrieved article was read in full by at least one analyst who determined whether that article met the inclusion criteria for the evidence report. The accuracy of the implementation of the inclusion criteria was audited by a separate analyst who examined 10% of the articles assigned to each analyst, and any discrepancies or uncertainties were discussed at team meetings which involved two to three individuals. Articles that met all inclusion and retrieval criteria comprised the body of evidence for the review of programs for each topic area. Once the body of evidence was identified, each study was abstracted, using a standard form (Table 2).

Table 2.

Abstraction Form

| Reference |

|---|

|

|

| Country study performed |

| Key question(s) addressed |

| General study characteristics |

| Study design |

| Type of study population |

| Aim of study |

| Follow-up time |

| Outcomes of interest |

| Intervention characteristics |

| Number of study groups |

| Control |

| Intervention(s) |

| Intensity of intervention(s) |

| Frequency of intervention(s) |

| Sample characteristics |

| Inclusion criteria |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Recruitment method |

| Setting |

| Number of individuals enrolled/randomized/dropped out |

| Proportion of enrollees who are female |

| Race/ethnicity |

| Age |

| Educational status |

| Family income |

| Insurance status |

| Residence (urban/rural) |

| Previous sexual and/or pregnancy experience |

| Additional attributes |

| Measurement characteristics |

| How were outcomes assessed? |

| Findings and conclusions |

| Major findings |

| Investigator conclusions |

Assessing the Internal and External Validity of Included Studies

The quality, or internal validity, of each individual study was assessed to consider the risk that the findings may be confounded by a systematic bias. We used the schema developed by the USPSTF15 for describing a study’s level of risk for bias (Table 3). A rating of risk for bias was determined through the presence or absence of several characteristics that are known to protect a study from the confounding influence of bias (Table 4). We developed criteria by which the risk for bias of individual studies could be evaluated, based on recommendations from several sources, including the USPSTF15; the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)20; and Community Guide for Preventive Services.21 The nomenclature for describing study design in the evidence reviews was based on a modified algorithm developed by Zaza et al.22

Table 3.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Levels of Evidence

| USPSTF level of evidence | Study type |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Level I | Properly designed randomized controlled trial |

| Level II-1 | Well-designed controlled trial without randomization |

| Level II-2 | Evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case–control analytic studies, preferably from more than one center or research group |

| Level II-3 | Evidence obtained from multiple time series with or without the intervention. Dramatic results in uncontrolled trials might also be regarded as this type of evidence |

| Level III | Opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees |

Table 4.

Criteria Used to Determine a Study’s Risk for Bias

| Study design | Minimal criteria | Risk for bias category |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Systematic review | • Comprehensiveness of sources considered/search strategy used • Standard appraisal of included studies • Validity of conclusions • Recency and relevance are especially important for systematic reviews |

Low risk: Recent, relevant review with comprehensive sources and search strategies; explicit and relevant selection criteria; standard appraisal of included studies; and valid conclusions Moderate risk: Recent, relevant review that is not clearly biased but lacks comprehensive sources and search strategies High risk: Biased review without systematic search for studies, explicit selection criteria, or standard appraisal of studies |

| RCTs and cohort studies | • Initial assembly of comparable groups: ○ For RCTs: adequate randomization, including first concealment and whether potential confounders were distributed equally among groups ○ For cohort studies: consideration of potential confounders with either restriction or measurement for adjustment in the analysis; consideration of inception cohorts • Maintenance of comparable groups (includes attrition, cross-overs, adherence and contamination) • Important differential loss to follow-up or overall high loss to follow-up • Measurements: equal, reliable, and valid (includes masking of outcome assessment) • Clear definition of interventions • All important outcomes considered • Analysis: adjustment for potential confounders for cohort studies, or intention-to-treat analysis for RCTs |

Low Risk: Meets all criteria: Comparable groups are assembled initially and maintained throughout the study (follow-up at least 80%); reliable and valid measurement instruments are used and applied equally to the groups; interventions are spelled out clearly; all important outcomes are considered; and appropriate attention to confounders in analysis. In addition, for RCTs, intention to treat analysis is used. Moderate Risk: Studies will be graded “fair” if any or all of the following problems occur, without the fatal flaws noted in the “poor” category below: Generally comparable groups are assembled initially but some question remains whether some (although not major) differences occurred with follow-up; measurement instruments are acceptable (although not the best) and generally applied equally; some but not all important outcomes are considered; and some but not all potential confounders are accounted for. Intention to treat analysis is done for RCTs. High Risk: Groups assembled initially are not close to being comparable or maintained throughout the study; unreliable or invalid measurement instruments are used or not applied at all equally among groups (including not masking outcome assessment); and key confounders are given little or no attention. For RCTs, intention to treat analysis is lacking. |

| Case-control studies | • Accurate ascertainment of cases. • Nonbiased selection of cases/controls with exclusion criteria applied equally to both. • Response rate. • Diagnostic testing procedures applied equally to each group. • Measurement of exposure accurate and applied equally to each group. • Appropriate attention to potential confounding variables. |

Low Risk: Appropriate ascertainment of cases and nonbiased selection of case and control participants; exclusion criteria applied equally to cases and controls; response rate equal to or greater than 80%; diagnostic procedures and measurements accurate and applied equally to cases and controls; and appropriate attention to confounding variables Moderate Risk: Recent, relevant, without major apparent selection or diagnostic work-up bias but with response rate less than 80% or attention to some but not all important confounding variables High Risk: Major selection or diagnostic work-up biases, response rates less than 50%, or inattention to confounding variables |

| Pre–post studies | • There is no evidence for a prevailing “temporal trend” (e.g., a general reduction in population smoking rates) that may confound study findings • Measures taken close in time to the intervention or exposure • Potential confounding factors have been controlled for • No significant sources of measurement bias (e.g., whether exposures and outcomes are assessed using reliable criteria) are known • Little or no indication of selection bias (e.g., have the most or least motivated individuals been selected for participation?) • Clear and consistent inclusion and exclusion criteria in subject selection • Causality between intervention and outcome is strengthened when observed changes are significant and occur soon after the intervention |

Low risk: Meets all or most of these criteria Moderate risk: Meets some but not all of these criteria High risk: Problems with most of the criteria or reporting does not permit an assessment of these criteria |

| Time-series | • Outcomes were assessed before and after an intervention was delivered • It is clear precisely when an intervention took place (i.e., in order to compare outcomes before and after intervention) • There is no evidence for a prevailing “temporal trend” (e.g., a general reduction in population smoking rates) that may confound study findings • Measures taken close in time to the intervention or exposure • Potential confounding factors have been controlled for • No significant sources of measurement bias (e.g., whether exposures and outcomes are assessed using reliable criteria) are known |

Low risk: Meets all or most of these criteria Moderate risk: Meets some but not all of these criteria High risk: Problems with most of the criteria or reporting does not permit an assessment of these criteria |

| Cross-sectional study | • Potential confounding factors have been controlled for • No significant sources of measurement bias (e.g., whether exposures and outcomes are assessed using reliable criteria) are known |

Low risk: Meets all or most of these criteria Moderate risk: Meets some but not all of these criteria High risk: Problems with most of the criteria or reporting does not permit an assessment of these criteria |

| Survey | • Non-response bias controlled • Random or probability sampling of potential respondents • Valid survey tool employed |

Low risk: Meets all or most of these criteria Moderate risk: Meets some but not all of these criteria High risk: Problems with most of the criteria or reporting does not permit an assessment of these criteria |

The external validity, or generalizability, of study findings was also assessed by examining characteristics of each study’s sample, including sex, age, race/ethnicity, educational status, family income, insurance status, and residence (urban/rural).

Producing the Evidence Report

Once the quality and generalizability of each study was assessed, data were presented in a series of summary “evidence” tables, and a synthesis of the evidence was prepared for each topic area. Each synthesis included information about the number of studies identified for each key question, a description of the study population, the intervention, and key results; it also included an assessment of each study’s risk for bias. The original four priority areas identified by the Expert Work Group were further refined through the review process described above, as discrete categories of interventions were identified by CDC and OPA staff and the individuals conducting the systematic review. The original topic area of “counseling and education” was subdivided into counseling, education, and reminder devices. The topic area of “adolescent services” was subdivided into youth-friendly services, confidential services, parent–child communication, and repeat teen pregnancy. “Community outreach” was subdivided into community education and community engagement. Quality improvement was not subdivided. Detailed summaries of the specific search strategies and evidence synthesis findings for nine of these ten areas are presented in separate papers6–14 in this journal supplement.

Discussion

As pointed out by the IOM, clinical guidelines are often based on incomplete reviews of the evidence.2–4 Such clinical guidelines may be criticized as being biased. As a consequence, CDC and OPA used a development process to ensure that the evidence used to inform its practice guidelines was collected in a manner that was transparent, reproducible, and minimized bias. To this end, CDC and OPA commissioned a series of systematic reviews on several priority topics (contraceptive counseling and education, adolescent services, quality improvement, community participation/outreach) related to the delivery of family planning services. This paper briefly describes the methodology used in conducting the systematic reviews.

The results of each systematic review were presented to four separate technical panels of subject matter experts held in Atlanta and Washington DC during the spring and summer of 2011. The role of these technical panels was to help CDC and OPA draw conclusions about the overall strength of the available evidence and then use that evidence to develop draft evidence-based guideline statements. Subsequently, the Expert Work Group was asked to review the evidence and draft recommendations, offer input for how to revise the recommendations based on the evidence, and assist in the development of explicit rationales for each recommendation that articulate the evidence underpinning each one.1 By so doing, we made every effort to adhere to the IOM standard related to using systematic reviews to inform the guideline development process, and to present those results in an open and transparent manner.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this article was supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of Population Affairs (OPA).

Funding was received from CDC under contract number 2009-N-11195. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC or the Office of Population Affairs.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.CDC. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of the CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(4):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IOM. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dachs R, Darby-Stewart A, Graber MA. How do clinical practice guidelines go awry? Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(6):514–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossman DC, Moyer VA, Melnyk BM, Chou R, DeWitt TG, Force USPST. The anatomy of a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation: lipid screening for children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(3):205–210. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavin LE, Moskosky SB, Barfield WD. Introduction to the supplement: development of federal recommendations for family planning services. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S1–S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brittain AW, Williams JR, Zapata LB, et al. Confidentiality in family planning services for young people: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S85–S92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brittain AW, Williams JR, Zapata LB, et al. Youth-friendly family planning services for young people: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S73–S84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter MW, Tregear ML, Lachance CR. Community engagement in family planning in the U.S.: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S116–S123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter MW, Tregear ML, Moskosky SB. Community education for family planning in the U.S.: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S107–S115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JR, Gavin LE, Carter MW, Glass E. Client and provider perspectives on quality of care: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S93–S106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavin LE, Williams JR, Rivera MI, Lachance CR. Programs to strengthen parent–adolescent communication about reproductive health: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S65–S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pazol K, Zapata LB, Tregear SJ, et al. Impact of contraceptive education on contraceptive knowledge and decision making: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S46–S56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zapata LB, Tregear SJ, Curtis KM, et al. Impact of contraceptive counseling in clinical settings: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S31–S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zapata LB, Tregear SJ, Tiller M, et al. Impact of reminder systems in clinical settings to improve family planning outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S57–S64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Procedure Manual. AHRQ Publication No. 08–05118-EF. July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirby D Comprehensive sex education: strong public support and persuasive evidence of impact, but little funding. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(11):1182–1184. 10.1001/archpedi.160.11.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirby DB, Laris BA, Rolleri LA. Sex and HIV education programs: their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(3):206–217. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oringanje C, Meremikwu MM, Eko H, Esu E, Meremikwu A, Ehiri JE. Interventions for preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD005215. 10.1002/14651858.CD005215.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivera M, Williams J, Lachance C, Gavin L. Programs designed to prevent repeat teen pregnancy in clinical settings: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- 20.GRADE Working Group. GRADE: going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1049–1051. 10.1136/bmj.39493.646875.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based Guide to Community Preventive Services—methods. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 suppl): 35–43. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaza S, Wright-De Agüero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 suppl):44–74. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]