Abstract

Mindfulness is a state of awareness characterized by open and non-judgmental recognition of thoughts and sensations and an ability to resist the usual wandering of an individual’s attention. Usually achieved by meditation, mindfulness is recognized as a treatment for chronic pain. Evidence, thus far, has been characterized by poor quality trials and mixed results, but a growing body of research is further investigating its effectiveness. Despite inconclusive evidence, the inherent difficulties of mindfulness research, and problems of accessibility in rural settings, mindfulness meditation is an emerging treatment strategy for many chronic pain patients. This report presents the case of a patient admitted to a rural hospital in New South Wales, whose quality of life was severely impacted by chronic pain.

Keywords: Aging, Behavioral neurology, Pain

INTRODUCTION

Chronic pain is highly prevalent in rural Australia with a lack of holistic pain management services.[1-3] Chronic pain is complex in its etiology and lasts longer than 3–6 months, or beyond the duration required for normal tissue healing after an acutely painful event.[4] Acute pain is mostly biological in nature, whereas chronic pain results from a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors and often requires a multifactorial approach to evaluation and management.[4,5] In Australia, one in every five people lives with persistent pain (i.e., 3.24 million Australians in total), and nearly 70% are of working age.[6] However, referrals to pain specialists occur in <15% of GP consultations, whereas medications are used in nearly 70%.[6] Access to holistic pain management services is especially poor in regional and rural Australia, with most multidisciplinary-care clinics located in major cities.1,2 Allied health professionals, who are expected to play a significant role in the non-pharmacological treatment of chronic pain, are underrepresented in rural areas.[7] Further, those who are able to access pain services often wait months to be seen, with a median wait time of 85 days in provincial (non-capital city) clinics.[2] Given these challenges, chronic pain patients are often difficult to treat in rural and remote settings.

Mindfulness is a state of awareness characterized by open and non-judgmental recognition of thoughts and sensations and an ability to resist the usual wandering of an individual’s attention.[8] Usually achieved by meditation, mindfulness is recognized as an effective treatment for chronic pain.[9] Evidence, thus far, has been characterized by poor quality trials and mixed results, but a growing body of research is further investigating its effectiveness.[9] Meditation uses a distinct brain pathway – change in the cortical thickness in the brain – to deal with chronic pain. Studies reported that mindfulness meditation promotes cognitive disengagement and also induces a person’s body opioid system to reduce the feeling of pain.[8,9] Despite inconclusive evidence, the inherent difficulties of mindfulness research, and problems of accessibility in rural settings, mindfulness meditation is an emerging treatment strategy for many chronic pain patients.

This report presents a patient case admitted to a rural hospital in New South Wales, whose quality of life was severely impacted by chronic pain. As an adjunct to medication, mindfulness meditation became an important part of his treatment plan. This report highlights the effectiveness of mindfulness meditation and ends with a discussion of the difficulty accessing these services in rural Australia, and the role technology can play in improving access.

CASE REPORT

| A Clinical Case in Rural Australia |

| Barry Davidson (pseudonym) was an inpatient at a rural hospital in New South Wales, Australia from July to September 2021. A 52-year-old T4 paraplegic, Barry had been admitted under the general surgeons for management of NPUAP stage 4[10] pressure injuries from prolonged immobilization. The cause of these pressure injuries was Barry’s chronic abdominal and back pain, worsening dramatically over the previous few months to the point where any movement was painful. Living alone in rural New South Wales, it had become very difficult for Barry to continue managing his own care. While admitted, the surgical team investigated his abdominal and back pain. Blood tests and abdominal imaging found no pathology and a spinal MRI found old compression fractures of T4-5, now partially fused, but no acute pathology. He was further investigated for medical causes of his pain. Gastroscopy and colonoscopy were unremarkable, as were his kidney and liver function tests and full blood count. Ultimately, no cause of the chronic pain was identified. The network-wide chronic pain service was consulted, but they were only able to see Barry 3 weeks later, despite him remaining an inpatient. Due to the unfeasible waiting time for non-pharmacological services for chronic pain, he was commenced on oral paracetamol and 5–10 mg oxycodone by the Acute Pain Service, which worsened constipation and made him nauseous. He was then swapped to clonidine and rectal indomethacin. To encourage weaning of his dependence on opioids, he was also commenced on gabapentin and tapentadol. This regimen, however, led to a number of side effects including sedation and fatigue, so these were ceased in favor of duloxetine. Ultimately, he remained on regular oxycodone CR and PRN oxycodone and oxazepam. Barry was not fit to return to living alone; however, rural rehabilitation hospitals nearby thought that he was too complex to manage. |

| Barry was transferred to a smaller, rural rehabilitation hospital after 8 weeks as an inpatient, once his pressure injuries had healed. Despite this, the management of his chronic pain was still suboptimal. He recovered some function gradually with the help of nursing and allied health staff, while remaining on duloxetine, clonidine, indomethacin, oxycodone and oxazepam. Yet, his ongoing dependence on care prevented him from returning to his own home, and thus he was discharged to a residential aged care facility. |

Management of Barry’s chronic pain

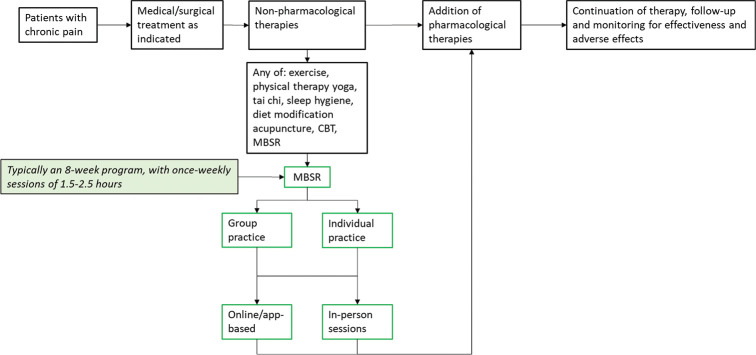

The management of Barry’s chronic pain within the inpatient setting and rural rehabilitation hospital was suboptimal. The chronic pain management in Australia is guided by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.[11] The first step is to treat any identifiable source of pain medically or surgically. Then, engage any of the nonpharmacological therapies: Exercise, physical therapy, sleep hygiene techniques, behavioural and psychological therapies, healthy lifestyle interventions, or acupuncture. If there is an ongoing pain that interferes with normal functioning, pharmacological treatments may be added. For nociceptive pain, first line is NSAIDs; for neuropathic pain, there are a few options including antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs. If there is still insufficient response, opioids may be used, but only after consideration of severity of pain, and weighing the benefits and risks. A Cochrane review of opioids for long-term treatment of non-cancer pain found that continuation of long-term opioids led to clinically significant pain relief.[12] However, the quality of the evidence in this review is weak; 25 out of 26 trials were case studies without controls, and the only randomized and controlled trial (RCT) compared two opioids. Evidence for other treatments, including physical activity[13] and psychological therapy,[14] is also weak, but these strategies are still advocated for.[11]

The management of chronic pain in Barry’s case followed the above step-wedge approach, but limited access to nonpharmacological services in the inpatient setting led to some divergence. The introduction of opioid analgesia came after excluding medical or surgical causes and high-dose oral paracetamol. Introducing the mindfulness meditation earlier may have reduced the need for opioid analgesia, but these strategies were difficult to implement in the busy inpatient environment and pharmacological options were preferred by Barry. While a resident in rural aged care facility, Barry began to engage in the meditation classes provided by a local meditation guide that visited the facility.

Effectiveness of mindfulness meditation in Barry’s case

Meditation became the most important part of his pain management in aged care facility. Barry attended weekly meditation sessions delivered to a group in an in-person setting. Over subsequent weeks, his participation steadily increased and his pain began to improve. Barry continued to attend the weekly meditation sessions over the following months and despite reporting that his pain was not completely resolved. In brief but noticeable moments of mindfulness, Barry has been able to focus on his pain, recognize it as an appearance in consciousness, and simply come to terms with it. On days that Barry meditates, he describes a lasting feeling that he is able to connect with feelings of pleasure and relief, even when at other times his pain is overwhelming. Barry was fortunate to have access to a meditation guide, as access to in-person meditation sessions is often rare in rural areas. Furthermore, Barry was unwilling to engage in online and app-based guided meditation, due to concerns of difficulty maintaining interest and enthusiasm. This may be a concern shared by many potential meditators and the regularity and commitment of an in-person program may improve engagement. However, a more flexible and individualized approach (such as through app-based courses) may still be preferable to many people.

DISCUSSION

The case that we have presented was initially an inpatient with chronic pain, who were referred to a rural residential aged care facility because of his ongoing dependency on care for pain. The strength of this case is the illustration of a step-wedge way of managing chronic pain in a monitored setting following the NICE guideline. However, the limitations were: (i) mindfulness meditation and low access to nonpharmacological services, like mindfulness meditation in the inpatient setting; (ii) lack of individualized approach in therapy; and (iii) unwillingness to engage in online and app-based guided meditation. An understanding of and engagement with mediation as well as adequate access to such therapy in rural health-care settings would enhance the chance of managing chronic pain in a successful way.

In Western cultures, meditation is typically associated with yogis, hippies, and “self-help gurus,” has struggled to break from its Buddhist roots, and become established in an increasingly secular society. Dan Harris, an American news anchor, wrote a book about meditation after stumbling on the practice whilst working as a “religion correspondent.”[15] This author asserts that the problem with meditation is that “its most prominent proponents talk as if they have a perpetual pan flute accompaniment,” but, “If you can get past the cultural baggage…you’ll find that meditation is simply an exercise for your brain.”[15] Commonly, meditation sessions involve focused awareness on an appearance in consciousness, such as the sensation of breathing or the feeling of one’s body while sitting in a chair. Humans are constantly distracted by thought and meditation is the practice of recognizing these thoughts merely as appearances in our consciousness, just like sensations, and then reorientating oneself to the practice. Each time one notices, they are lost in thought, the act of bringing attention back to the breath or sensations acts to train the mind. Mindfulness has been found to regulate the sensation of acute[16] and chronic[8] pain, improve cognition,[17] and treat anxiety[18] and depression.[19]

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is a therapy developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts.[20,21] It typically involves a standardized course of 8 weeks of mindfulness meditation sessions, performed once-weekly for 1.5–2.5 h [Figure 1].[8,22-25] There has been important research in the last decade investigating the role of MBSR in the treatment of chronic pain,[21,25-27] with inconsistent results. A number of studies show reduced pain intensity in groups treated with MBSR,[24-26,28] but these improvements may be short lived.[24] The mechanism by which pain is reduced in these patients has been postulated to be through the effects of medication on psychological factors. Indeed, a number of studies find that the benefits of meditation are most prominent in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety and improving psychological functioning.[23,27,29] One important trial, conducted on older patients in in whom pharmacological analgesia is often complicated by adverse effects, found that MBSR led to improvements in chronic pain.[24] The MBSR approach is fairly common in the literature and has the largest evidence base supporting it; however, there is considerable heterogeneity in the format used depending on billing structure, type of session (guided vs. silent), and other factors. The approach taken by Barry involved ongoing weekly sessions 30 min in length, as facilitated by the meditation guide.

Figure 1:

Approach to the treatment of chronic pain, highlighting the role of mindfulness-based stress reduction.

Mindfulness is often associated with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), as there are many similarities between the two practices. Both are psychological therapies that encourage the practitioner to examine their thoughts, emotions, sensations, and behaviors. The techniques used in these practices, including deep breathing and self-reflection, are also common to both therapies. CBT has been studied since the 1980s but recent reviews suggest only a small to moderate effect on pain,[14] with some patients receiving no benefit.[30,31] Further, a number of studies have compared MBSR and CBT. A systematic review in 2011 found that MBSR was no better than CBT in the treatment of chronic pain, but it may be a good alternative.[28] Despite the low quality evidence, the authors recommended therapies that combined both mindfulness and behavioral therapy. In a larger, randomized, and interviewer-blind trial, MBSR and CBT were both found to improve chronic low back pain compared to usual care, with no differences identified between MBSR and CBT.[25] In one RCT of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), CBT conferred the largest improvement in pain, but meditation was more beneficial in RA patients with psychological manifestations of their pain.[32] The poor quality of many of the studies, however, makes it difficult to conclude the effectiveness of MBSR in treating chronic pain, as noted by a systematic review in 2012.[22] A more recent RCT of 109 patients found no significant differences in pain measures between MBSR and a wait list control.[23] Access to psychological therapies such as CBT is often difficult in rural areas. Improvements in technology, such as telehealth conferencing, may improve access to CBT, but the individualized therapy prohibits the scalability offered by online and app-based guided meditation services. Although technology may allow those in rural areas to access CBT services provided in metropolitan areas more easily, the format of one-on-one therapy may limit engagement due to wait times for appointments and out-of-pocket costs.

There are inherent difficulties in performing high quality trials of mindfulness in medical research. Measuring mindfulness is difficult and there is little consensus as to the components of the mindfulness experience.[27] Much of the research involves self-reporting of results, which exposes trials to significant response bias.[20] Further, problems emerge when designing control interventions, as many trials involve wait-list controls, where the control group is given no intervention for the study period, then offered the intervention at a later date.[27] Another factor that compounds inconsistency of intervention is the modification of MBSR,[27] leading to variability in the intervention given and reduced generalizability. There are also significant difficulties in elucidating the dose-response relationship of mindfulness,[27] as measuring both the dose of meditation and the response to it is abstract and challenging. Some practitioners achieve benefit almost immediately and some require years of practice.

Further research should prioritize quality and comparison using quantitative measures, where possible. Structured measurements of mindfulness may be used, including scales such as the Mindfulness and Attention Awareness Scale[33] and the Frieburg Mindfulness Inventory.[34] A pain assessment in patients before and after the mindfulness session, using the appropriate scale such as Numerical Rating Pain Scale, Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale, FLACC Scale, CRIES Scale, COMFORT Scale, or McGill Pain Scale would be a better scientific approach to such case study. These measures may allow for quantitative analysis of the effects of meditation and allow for correlation with pain scores. Empirical evidence of the extent of mindfulness may also reveal the most effective meditation techniques, including in specific subpopulations such as those with chronic pain. In addition, the future studies should incorporate active control groups and standardized mindfulness interventions,[27] to promote comparison between different treatment modalities and to encourage adoption of mindfulness on a larger scale. High-quality RCTs using quantitative measurement of mindfulness and active control groups in chronic pain patients are needed.

There remains the problem of access to meditation services, especially in regional and rural areas. Access to guided meditation can be difficult and expensive. Classes and retreats are often fully booked with existing clients and those taking new clients are expensive. The Meditation Association of Australia suggests fees of up to $400/h for sessions delivered to community groups and $1000/h for businesses.[35]

Practical steps in mindfulness meditation prescribing in rural areas

Technology has improved access to many health-care services for patients in rural areas. These services include pain management and research has suggested that delivery of meditation sessions through teleconferencing may be effective.[36] Furthermore, access to mindfulness meditation services in rural areas has been transformed by the development of online and app-based resources. Many of these resources involve pre-recorded, guided meditation sessions, and delivered at a time of the practitioner’s convenience. In the era of COVID-19, when most group therapy sessions have been cancelled, these resources are especially relevant and may be preferable for many people. There are a variety of programs available online and to download. Some, such as Smiling Mind, Insight Timer, UCLA Mindful and Healthy Minds offer free access to meditation sessions. Some other apps, such as Headspace, Calm, Waking Up, and Stop Breathe Think, require a paid subscription, but often include extra content such as podcasts. Evidence for app-based delivery of mindfulness meditation in the treatment of chronic pain is lacking, but it represents a low cost, safe, and accessible option for patients in rural areas with less access to traditional services. Rural health practitioners may consider these emerging technologies when dealing with a multipronged approach to chronic pain.

The search for effective chronic pain treatments is ongoing, but there may be further benefit gained from existing strategies, such as mindfulness meditation and CBT. Our case clarifies the effectiveness of mindfulness, but lack of access to services was evident. It is a reasonable choice for clinicians to advocate for, due to its negligible harms, additional psychological benefits, and increasing accessibility through technology. Access to meditation services in rural and regional Australia may be challenging, but online and app-based programs may provide a new avenue for the treatment of chronic pain.

CONCLUSION

The search for effective chronic pain treatments is ongoing, but there may be further benefit gained from existing strategies, such as mindfulness meditation and CBT. Our case clarifies the effectiveness of mindfulness, but lack of access to services was evident. It is a reasonable choice for clinicians to advocate for, due to its negligible harms, additional psychological benefits, and increasing accessibility through technology. Access to meditation services in rural and regional Australia may be challenging, but online and app-based programs may provide a new avenue for the treatment of chronic pain.

Funding Statement

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Bishop ME, Hamiduzzaman M, Veltre AS. Mindfulness meditation use in chronic pain treatment in rural Australia: Pitfalls and potential – A case report. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2023;14:516-21.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Australia P. National Pain Services Directory. 2020. Available from: https://www.painaustralia.org.au/pain-services-directory/pain-directory [Last accessed on 2021 Nov 5]

- 2.Hogg MN, Kavanagh A, Farrell MJ, Burke AL. Waiting in pain II: An updated review of the provision of persistent pain services in australia. Pain Med. 2021;22:1367–75. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alliance NR. Deakin West (ACT): National Rural Health Alliance; 2013. Chronic Pain-a Major Issue in Rural Australia [Fact Sheet] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP classification of chronic pain for the international classification of diseases (ICD-11) Pain. 2019;160:19–27. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. 2021;397:2082–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00393-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Economics DA. Canberra: Deloitte Access Economics; 2019. The Cost of Pain in Australia: A Painful Reality. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Commissioner NRH. Canberra (ACT): Health Do; 2020. National Rural Health Commissioner Final Report. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51:199–213. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, et al. The revised international association for the study of pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161:1976–82. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edsberg LE, Black JM, Goldberg M, McNichol L, Moore L, Sieggreen M. Revised national pressure ulcer advisory panel pressure injury staging system: Revised pressure injury staging system. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016;43:585–97. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Evidence Review for Psychological Therapy for Chronic Primary Pain. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2021. Chronic Pain (Primary and Secondary) in Over 16s: Assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, Coates VH, Wiffen PJ, Akafomo C, et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010:CD006605. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006605.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: An overview of cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011279. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams AC, Fisher E, Hearn L, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8:CD007407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris D. New York, United States: Dey Street Books; 2014. 10% Happier: How I Tamed the Voice in My Head, Reduced Stress Without Losing My Edge, and Found Self-Help That Actually Works--a True Story. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeidan F, Martucci KT, Kraft RA, Gordon NS, McHaffie JG, Coghill RC. Brain mechanisms supporting the modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5540–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5791-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeidan F, Johnson SK, Diamond BJ, David Z, Goolkasian P. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Conscious Cogn. 2010;19:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim B, Lee SH, Kim YW, Choi TK, Yook K, Suh SY, et al. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based cognitive therapy program as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy in patients with panic disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:590–5. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godfrin KA, van Heeringen C. The effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on recurrence of depressive episodes, mental health and quality of life: A randomized controlled study. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:738–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J Behav Med. 1985;8:163–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00845519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin Psychol. 2003;10:144–56. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cramer H, Haller H, Lauche R, Dobos G. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for low back pain. A systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:162. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La Cour P, Petersen M. Effects of mindfulness meditation on chronic pain: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 2015;16:641–52. doi: 10.1111/pme.12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morone NE, Greco CM, Moore CG, Rollman BL, Lane B, Morrow LA, et al. A mind-body program for older adults with chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:329–37. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, Cook AJ, Anderson ML, Hawkes RJ, et al. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1240–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiner K, Tibi L, Lipsitz JD. Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce pain intensity? A critical review of the literature. Pain Med. 2013;14:230–42. doi: 10.1111/pme.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mars TS, Abbey H. Mindfulness meditation practise as a healthcare intervention: A systematic review. Int J Osteopath Med. 2010;13:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijosm.2009.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KM, Bohlmeijer ET. Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2011;152:533–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ball EF, Sharizan EN, Franklin G, Rogozińska E. Does mindfulness meditation improve chronic pain? A systematic review. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;29:359–66. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turk DC. The potential of treatment matching for subgroups of patients with chronic pain: Lumping versus splitting. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:44–55. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00006. discussion 69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vlaeyen JW, Morley S. Cognitive-behavioral treatments for chronic pain: What works for whom? Clin J Pain. 2005;21:1–8. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zautra AJ, Davis MC, Reich JW, Nicassario P, Tennen H, Finan P, et al. Comparison of cognitive behavioral and mindfulness meditation interventions on adaptation to rheumatoid arthritis for patients with and without history of recurrent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:408–21. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:822–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmüller V, Kleinknecht N, Schmidt S. Measuring mindfulness-the Freiburg mindfulness inventory (FMI) Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40:1543–55. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meditation Association of Australia . Australia: Meditation Association of Australia; 2021. Suggested Fees: How Much Should Meditation Teachers Charge for Their Services? Available from: https://meditationaustralia.org.au/membership/suggested-pricing/ [Last accessed on 2021 Oct 12] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gardner-Nix J, Backman S, Barbati J, Grummitt J. Evaluating distance education of a mindfulness-based meditation programme for chronic pain management. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14:88–92. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2007.070811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]