Abstract

The CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) binds tens of thousands of enhancers and promoters on mammalian chromosomes by means of its 11 tandem zinc finger (ZF) DNA-binding domain. In addition to the 12–15-bp CORE sequence, some of the CTCF binding sites contain 5′ upstream and/or 3′ downstream motifs. Here, we describe two structures for overlapping portions of human CTCF, respectively, including ZF1–ZF7 and ZF3–ZF11 in complex with DNA that incorporates the CORE sequence together with either 3′ downstream or 5′ upstream motifs. Like conventional tandem ZF array proteins, ZF1–ZF7 follow the right-handed twist of the DNA, with each finger occupying and recognizing one triplet of three base pairs in the DNA major groove. ZF8 plays a unique role, acting as a spacer across the DNA minor groove and positioning ZF9–ZF11 to make cross-strand contacts with DNA. We ascribe the difference between the two subgroups of ZF1–ZF7 and ZF8–ZF11 to residues at the two positions −6 and −5 within each finger, with small residues for ZF1–ZF7 and bulkier and polar/charged residues for ZF8–ZF11. ZF8 is also uniquely rich in basic amino acids, which allows salt bridges to DNA phosphates in the minor groove. Highly specific arginine–guanine and glutamine–adenine interactions, used to recognize G:C or A:T base pairs at conventional base-interacting positions of ZFs, also apply to the cross-strand interactions adopted by ZF9–ZF11. The differences between ZF1–ZF7 and ZF8–ZF11 can be rationalized structurally and may contribute to recognition of high-affinity CTCF binding sites.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

The CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) (1) is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein, which has been subject to several recent reviews (2–4). CTCF is essential in vivo and is required for normal preimplantation development and differentiation of somatic cells of multiple tissues (5–8). It also appears to play a role in resistance to or induction of DNA damage (9–11). The multidomain CTCF protein is conserved in most bilaterian phyla (12) and influences 3D genome architecture (13) via a network of interactions with DNA (14,15), RNA (16–18) and the cohesin protein complex (19). Pairs of CTCF sites in convergent orientation are able to stop cohesin extrusion (20). CTCF binds tens of thousands of enhancers and promoters on mammalian chromosomes by the use of its 11 tandem zinc finger (ZF) DNA-binding domain and establishes interactions between distant enhancers and promoters by means of DNA loop extrusion (21). It is possible that high-affinity sites play structural roles in chromatin, while the lower-affinity sites are responsible for regulating transcription (22). A major question is how CTCF-bound enhancer and promoter elements find each other, stabilizing interactions between the two distant DNA elements and yielding associations with a long residence time [on the order of 22 min (23)] that are detectable in heatmaps of Hi-C data.

Most, if not all, CTCF binding sites in the genome contain a broad motif of 12–15 bp, called the CORE consensus sequence, that was uncovered by various methods, including ChIP-seq (24) and ChIP-exo (25). The CORE sequence is recognized by ZF3–ZF7 of CTCF (14,15). Other studies revealed that a subset of genomic CTCF binding sites have an additional 5′ upstream motif and/or 3′ downstream motif outside of CORE sequence (Figure 1A) (26–28). These sites may represent high-affinity binding sites because of involvement of additional ZF units outside of ZF3–ZF7 in binding either or both 5′ and 3′ motifs.

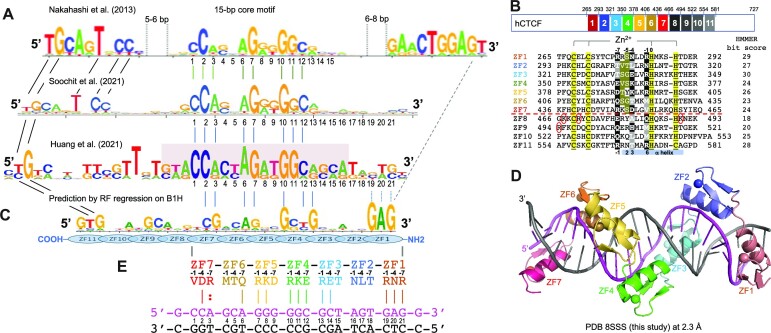

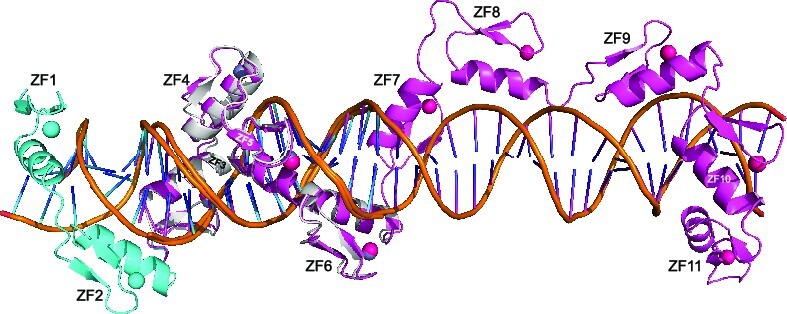

Figure 1.

CTCF has two subgroups of ZFs. (A) Three examples of CTCF-binding consensus CORE sequence (base pairs 1–15) with flanking 5′ upstream and 3′ downstream motifs. One notable difference is that the CORE sequence and the 3′ motif separated by a large spacing in (26) would not match to the binding by a single CTCF molecule. (B) Human CTCF contains a tandem ZF DNA binding array comprising 11 fingers (GenBank: AAB07788.1). Sequence alignment of the 11 C2H2 fingers with variations at DNA base-interacting positions −1, −4, −7 and –8. For comparison, the four ‘canonical’ positions of the helix are indicated at the bottom of the sequence. To the right, the HMMER algorithm has calculated the bit score for each finger and all of them have fairly high confidence scores, the lowest being 18 and the highest being 30 (http://zf.princeton.edu/index.php). Differences at positions −5 and −6 separate the two subgroups. The circled basic residues are unique to ZF8 or the linker between ZF8 and ZF9 of CTCF. (C) A predicted CTCF ZF1–ZF11 DNA-binding specificity is aligned with the consensus. A notable divergence from the consensus involves ZF1–ZF2 and ZF8–ZF11, whereas the predicted DNA-binding specificity of ZF3–ZF7 matches to the consensus CORE sequence. (D) A ribbon model of ZF1–ZF7 in complex with DNA. (E) Illustration of ZF1–ZF7 (oriented right to left from N to C termini) and the three base-interacting residues per finger at positions –1, –4 and –7. The double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides used for co-crystallization are shown with the top recognition strand (magenta) oriented left to right from 5′ to 3′. The vertical lines indicate base–amino acid specific interactions.

In a systematic analysis, Soochit et al. performed reconstitution experiments in CTCF−/− mouse embryonic stem cells by expressing GFP-tagged wild-type or mutant CTCF with in-frame deletions of individual ZFs (28). Whereas CTCF proteins containing individual deletions of ZF2–ZF7 failed to rescue the cell lethality caused by depletion of endogenous CTCF, the other single-finger deletions did restore viability. A mutant lacking ZF1 showed reduced binding to sites with a 3′ downstream motif, and mutants lacking ZF8–ZF11 exhibited decreased binding to sites with a 5′ upstream motif, suggesting that these fingers (ZF1 or ZF8–ZF11) are responsible, respectively, for binding the 3′ or 5′ motif. Interestingly, the ZF8 deletion mutant displayed the poorest binding to DNA and yielded diffuse CTCF nuclear distribution. We and others previously characterized structures of CTCF binding DNA using varied ZF fragments (14,15). Here, we characterized two CTCF fragments, ZF1–ZF7 in complex with the CORE and the 3′ motif, and ZF3–ZF11 in complex with the CORE and 5′ motif (Supplementary Table S1). These structures allowed inference of the entire DNA–(ZF1–ZF11) complex structure and revealed the unusual role of ZF8.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification

The DNA fragments coding for the CTCF ZF1–ZF7 (pXC1564) and ZF3–ZF11 (pXC1566) segments were ligated into the pGEX-6P-1 vector with a GST fusion tag. The point mutation Lys365-to-Thr (pXC2232) was introduced in the context of the ZF1–ZF7 construct (pXC1564) by one-step polymerase chain reaction-based mutagenesis and confirmed by sequencing (Supplementary Table S2). The plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21-Codon-plus (DE3)-RIL (Stratagene). Bacteria were grown in lysogeny broth in a shaker at 37°C until A600 nm was between 0.4 and 0.5, at which point the shaker temperature was lowered to 16°C and 25 μM ZnCl2 (final concentration) was added to the cell culture to ensure Zn incorporation. When the A600 nm reached ∼0.8, protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.4 mM (final concentration) of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, with subsequent incubation for 20 h at 16°C. The proteins were purified via a three-column chromatography protocol, as follows.

Cell pellets were collected by centrifugation and suspended in lysis buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 700 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) and 25 μM ZnCl2]. Cells were lysed by sonication. Polyethylenimine (Sigma, 408727) was added to the lysate drop by drop, to a final concentration of 0.3% (v/v) (29). Debris was removed by centrifugation for 30 min at 47 000 × g. The supernatant was loaded onto a 5 ml GSTrap column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 100 ml lysis buffer, and bound protein was eluted with elution buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mM TCEP and 20 mM reduced form glutathione). The eluted proteins were digested with PreScission protease (produced in-house) to remove the GST fusion tag. The cleaved protein was diluted to 300 mM NaCl and loaded onto 5 ml HiTrap-Q-SP columns (GE Healthcare) connected in tandem (29). After washing with the same buffer, the Q column was disconnected, and the target protein was eluted from the SP column with an NaCl gradient from 0.3 to 1 M in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol and 0.5 mM TCEP. The peak fractions were pooled, the salt concentration was estimated (and diluted to ∼300 mM NaCl again) and reloaded onto a second HiTrap-SP column, from which the protein was eluted with constant flow of 1 M NaCl buffer in a small volume at high concentration. The second SP column was simply used as a means of protein concentration. Concentrated protein was loaded onto a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex S200 column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 0.5 mM TCEP. The purified protein was frozen and stored at −80°C prior to use.

DNA binding assays

Fluorescence polarization assays were performed using a Synergy 4 microplate reader (BioTek) to measure DNA binding affinity. The 6-carboxyfluorescein-labeled double-stranded DNA probe (5 nM) (Supplementary Table S2) was incubated with an increasing amount of protein (2× serial dilution starting from 10 μM) for 15 min in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 5% (v/v) glycerol and 300 mM NaCl. GraphPad Prism software (version 7.0) was used to perform curve fitting. The dissociation constants (KD values) were calculated as [mP] = ΔmP × [C]/(KD + [C]) + [baseline mP], where mP is millipolarization, [C] is protein concentration and ΔmP = [maximum mP] − [baseline mP]. The reported mean ± SEM of the interpolated KD values were calculated from two independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

Crystallography

We crystallized ZF1–ZF7 and its mutant Lys365-to-Thr, and ZF3–ZF11 in complex with different oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table S2) by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method, at room temperature (∼19°C). We incubated purified protein and double-stranded oligonucleotide in a ratio up to 1.2:1 at 4°C for 30 min before crystallization. An Art Robbins Phoenix Crystallization Robot was used to set up screens. For the ZF3–ZF11 complex, we started with commercial screening kits, and followed with self-made optimization screens with variations of pH and concentrations of polyethylene glycol 3350. Crystals were cryoprotected by soaking in mother liquor supplemented with 20% (v/v) ethylene glycol before plunging into liquid nitrogen.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the SER-CAT beamline 22ID of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Resulting crystallographic datasets were processed with HKL2000 (30). Two scaled reflection files were output with one file combining Bijvoet pairs (used for structural refinement) and the other keeping the Bijvoet pair separate (used for generating anomalous electron densities). For each structure determination, 5% of reflections were randomly chosen for validation by Rfree values. The quality of all structures was analyzed during PHENIX refinements (31) and finally validated by the PDB validation server (32). Molecular graphics were generated by using PyMOL (Schrodinger, LLC).

The ZF1–ZF7 with the 23-bp DNA complex structure (PDB 8SSS) was initially solved by molecular replacement using the search model of PDB 5T0U (14). After several rounds of manual manipulation in COOT (33) and refinement using PHENIX (34), ZF1 and additional DNA residues were constructed. The mutant Lys365-to-Thr structure in the context of ZF1–ZF7 with the same 23-bp DNA (PDB 8SST) was determined by the difference Fourier method. The structure of ZF3–ZF11 with the 19-bp duplex DNA (PDB 8SSU) was solved by molecular replacement with the initial search model of PDB 5KKQ, and ZF11 was not observable in this structure.

The structure determination of ZF3–ZF11 complexed with the 35-bp DNA (oligo 35-4 in Supplementary Table S2) (PDB 8SSQ) began with a composite model made from PDB 5KKQ (ZF3–ZF7) and PDB 5UND (ZF4–ZF8) utilized for molecular replacement with the PHENIX PHASER module (35). After several rounds of manual manipulation in COOT (33) and refinement using PHENIX Refine (31), ZF9–ZF11 and additional DNA residues were slowly constructed between successive rounds of refinement utilizing difference density and knowledge of ZF and DNA structure. Placement of each ZF was first verified by using the PHENIX AutoSOL module (36) for MR-SAD and examination of Zn positions, and later by anomalous difference Fourier maps created after rounds of manual manipulation and subsequent refinement. Similar procedures were followed for ZF3–ZF11 in complex with oligo 35-20 structure (PDB 8SSR), using the ZF3–ZF11 (PDB 8SSQ) as the initial model by the difference Fourier method.

RESULTS

CTCF contains two subgroups of ZFs: ZF1–ZF7 and ZF8–ZF11

CTCF contains a DNA-binding domain that includes 11 tandem ZFs (Figure 1B). At least in humans, there are three isoforms of CTCF and, while we work here exclusively with derivatives of the longest one (isoform 1), it is interesting that isoform 2 is missing all or part of ZF1–ZF3 and, when expressed, competes with isoform 1 and triggers apoptosis (Supplementary Figure S1A) (37).

Like conventional C2H2 ZFs, named for the Zn atom being coordinated by two Cys and two His residues, each finger of CTCF comprises two β-strands and a helix [(14,15) and this study]. Characteristically, a pair of His residues in the helix acts together with two Cys residues of hairpin β-strands to coordinate a zinc ion, forming a tetrahedral Cys2–Zn–His2 structural unit that confers rigidity to the fingers. In ZF11 of CTCF, the last His is replaced by a Cys, forming an atypical CCHC (or C3H1) zinc coordination, as also seen in ZF4 of the transcription repressor ZBTB7A (38,39). This ZF11 His-to-Cys substitution is conserved across the vertebrates (Supplementary Figure S2) and may have structural and functional significance (40,41). In typical ZF proteins, there are 12 residues between the last Zn-coordinating Cys and the first Zn-coordinating His (Figure 1B). For simplicity, we use here the first zinc-coordinating His in each finger as reference position 0, with residues before this, at protein sequence positions −1 to −12 (see the next section). We noticed that the 11 fingers of CTCF can be divided into two subgroups according to the kind of residues present at positions −5 and −6. ZF1–ZF7 contain small residues (Gly, Val, Ser and Thr) at positions −5 or −6 or both, whereas ZF8–ZF11 contain bulkier and polar/charged residues (Arg, Lys, Glu, Asn, Gln or Tyr) at both positions (Figure 1B).

We used a prediction method for C2H2 ZFs (42) and the resulting bit score for each finger of CTCF ranged from 18 (ZF8) to 30 (ZF3) (Figure 1B; the higher scores are associated with higher confidence). A total of 33 base pairs of DNA were predicted for binding with the 11 ZFs of CTCF (Figure 1C), following the conventional rule of one finger for three base pairs (43). Both ZF1 and ZF11, with high confidence scores of 29 and 28, were predicted, respectively, to bind DNA sequences of 5′-GAG-3′ and 5′-GTG-3′ (Figure 1C). However, many studies uncovered a 12–15-bp CORE consensus sequence (e.g. see Supplementary Figure S1B), which matches the CTCF ZF3–7 binding specificity, but did not contain sequences outside of the 15-bp CORE region. Nakahashi et al. used ∼50 000 genomic sites in primary lymphocytes and found a 5′ upstream motif or a 3′ downstream motif separated from the CORE sequence by a short gap (Figure 1A) (26). More recently, CTCF binding sites in mouse embryonic stem cells were extended by including flanking sequences on both sides of the CORE (27,28). In both studies, the terminal 5′ and 3′ sequences partially match the predicted DNA-binding specificities of ZF1 and ZF11 (42,44,45).

ZF position numbering used in this study

When bound to DNA, the helix of a typical ZF lies in the DNA major groove, while the antiparallel hairpin β-strands and the C2–Zn–H2 unit lie on the outside (example shown in Figure 1D). The N-terminal portion of each helix and the preceding loop make major groove contacts with three or four adjacent DNA base pairs (46,47), which we term the ‘triplet element’. Amino acids at specific positions, namely −1, +2, +3 and +6 (bottom of Figure 1B), interact with the bases of the corresponding DNA element. This commonly used structure-based numbering scheme refers to the position immediately before the helix as −1, with positions 2, 3 and 6 within the helix. However, this numbering can lead to ambiguity [such as with the shorter helix in ZBTB7A (38)], so we use here the first zinc-coordinating His in each finger as reference position 0, with residues before this, at protein sequence positions −1, −4, −5 and −7, corresponding to the 6, 3, 2 and −1 of the structure-based numbering (compare top and bottom of the 11 ZF sequence alignment in Figure 1B).

The identities of three amino acids at positions −1, −4 and −7 of each finger are, respectively, the principal determinants of which DNA base is recognized for the 5′, central and 3′ positions of each triplet, primarily on one DNA strand (the ‘recognition strand’) (examples of ZF1–ZF7 are shown in Figure 1E). The bulky and charged/polar residues at base-interacting positions confer specificity for guanine (commonly by Arg, Lys or His), adenine (by Asn or Gln) or cytosine (by Asp or Glu). These base-specific interactions are established for many protein–DNA interactions, including C2H2 ZFs [reviewed in (48–51)]. Thymine and 5-methylcytosine both contain a methyl group at pyrimidine ring carbon-5 and are recognized via interactions with Glu or via methyl-specific van der Waals contacts, as illustrated by another 11-finger protein, Zfp568 (52). Where the base-interacting positions at −1, −4 and −7 are occupied by small (Thr in ZF2, ZF3 and ZF6) or hydrophobic residues (Leu, Met or Val in ZF2, ZF6 and ZF7), the corresponding DNA sequence usually is a variation of the consensus sequence. The variable bases also form (water-mediated) hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) and van der Waals contacts with these amino acids. These contacts are ‘versatile’, in the sense they can recognize more than one base at a given position, but also exclude one or more. This implies that the participating amino acids can suit the varied DNA substrates and, in this way, intimately fit the ZF array to a variety of different sequences. The adaptability to sequence differences is not unique to CTCF, as it also applies to other ZF arrays such as human PRDM9 at recombination hot spots (53). Next, we focus on our description of interactions engaging the two overlapping, structurally characterized CTCF fragments, ZF1–ZF7 and ZF3–ZF11.

Structure of ZF1–ZF7 of CTCF bound to DNA

We crystallized ZF1–ZF7 with a duplex containing 23 base pairs (labeled as 0–22 in Figure 2A). There is an additional base pair on either end of the double-stranded DNA, in addition to the seven DNA triplets corresponding to the seven ZFs, and including a GAG sequence at its 3′ end as predicted for ZF1 recognition. The structure includes two protein–DNA complexes in the crystallographic asymmetric unit (Supplementary Figure S3A and B), which was determined at a resolution of 2.3 Å (Supplementary Table S1). Each DNA/ZF1–ZF7 complex was very similar to the previously determined DNA/ZF2–ZF7 complex (PDB 5T0U), with a root-mean-squared deviation (rmsd) of just 0.6 Å over the common ZF2–ZF7 portion. Each finger interacts with two overlapping triplets (Figure 2A). We next summarize our observations, emphasizing the interactions that engage residues at positions −5 and −6 within each finger. These positions are in between two of the three key base specificity residues (−1, −4 and −7 in Figure 1B, as described above).

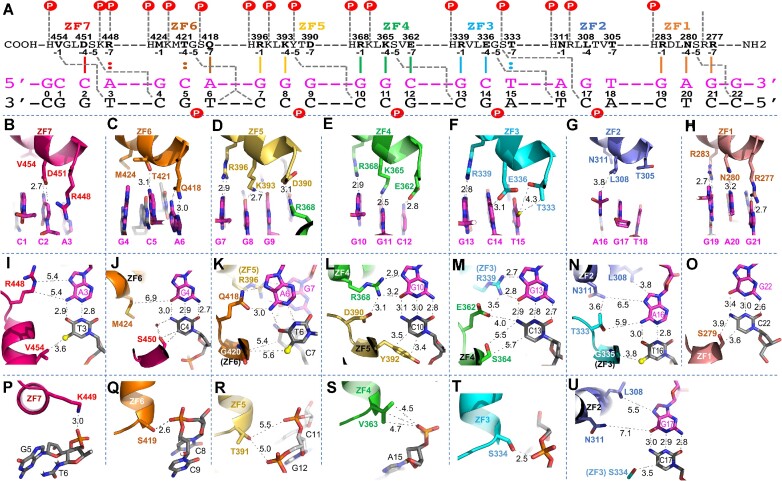

Figure 2.

Structure of ZF1–ZF7 in complex with DNA. (A) ZF1–ZF7 protein is arranged as N-to-C from right to left. Amino acids at positions −1, −4, −5 and −7 of each finger, relative to the first zinc-coordinating histidine, are shown below the protein sequence. The oligonucleotides used for crystallization are shown with the top strand (magenta) oriented left to right, from 5′ to 3′. The complementary strand is shown in black. The base pair positions are numbered from 0 to 22. The vertical lines between the protein and DNA recognition top strand indicate the base-specific interactions with each ZF. The dashed gray lines indicate cross-strand and cross-triplet interactions. The circled Ps indicate DNA backbone phosphate groups. (B–H) DNA base interactions of each triplet involve residues at positions −1, −4 and −7 of each ZF. (I–O) Cross-strand and cross-triplet interactions involve residues at position −5. (P–T) DNA backbone phosphate interactions involve residues at position −6 of each ZF. (U) Two alternative conformations of side chain of Ser334 engage in interactions with either the phosphate (panel T) or the base of C17.

First, amino acids at positions −1, −4 and −7 of each ZF interact with the three bases within a single triplet. Specifically, ZF7 interacts with the first, 5′-most triplet (CCA at DNA sequence positions 1–3), ZF6 interacts with the second triplet (GCA at DNA sequence positions 4–6) and so on, until ZF1’s interaction with GAG at DNA sequence positions 19–21 (Figure 2B–H).

Second, some amino acid–base interactions that might be expected are absent, particularly for hydrophobic or small side chains. Val454 of ZF7 and Met424 of ZF6, two hydrophobic residues located at the −1 positions of their respective fingers, are too far from the DNA to directly contact the corresponding bases C1 and G4 (Figure 2B and J). Similarly, Leu308 (at the −4 position) and Thr305 (at the −7 position) of ZF2 are distant from their corresponding bases G17 and T18 (Figure 2G). Among the seven ZFs, ZF2 is the only one that does not make any base-specific H-bonds at all, probably because all three potential base-interacting residues are out of H-bonding range of the DNA bases, including Asn311 at the −1 position (Figure 2N). It is interesting in this regard that ZF2 is one of the subset of CTCF fingers that, if deleted, cannot rescue the cell lethality caused by depletion of endogenous CTCF (28).

Third, in all ZFs that make base-specific contacts (so excepting ZF2), the amino acid at the −5 position makes a cross-triplet and cross-strand interaction with the first base pair of the following triplet (Figure 2A). Ser450 of ZF7 interacts with C4 of the second triplet via a van der Waals contact and a water-mediated H-bond (Figure 2J). Gly420 of ZF6 makes two water-mediated H-bonds, one each with T6 of the cognate triplet and C7 of the next triplet (Figure 2K). Tyr392 of ZF5 stacks its aromatic ring against C10 with a letter T-shaped stacking geometry (54) (Figure 2L). Ser364 of ZF4 makes weak van der Waals contacts with C13 (Figure 2M, and see below for its involvement in binding methylated C13). The Cα atom of Gly335 in ZF3 makes a van der Waals contact with the methyl group of T16 (Figure 2N). Finally, Ser279 of ZF1 makes a van der Waals contact with C22 (Figure 2O). Despite the amino acid variation at position −5 in each ZF, almost all the interactions are with the bottom strand, the nucleotide immediately after and/or the last base pair of the cognate triplet. The small side chains of Ser and Gly have the adaptability to act as an H-bond donor or acceptor, both at the same time, or as mediated by water molecules. This observation also suggests that the cross-strand contact mediated by the small amino acid at position −5 (corresponding to position 2 of the original structure-based numbering scheme; Figure 1, bottom) is generally not a determinant of DNA-binding specificity. One exception is Tyr392, at position −5 of ZF5, which we discuss next.

Among the seven ZF units of ZF1–ZF7, only ZF5 contains the bulky and aromatic Tyr392 at position −5, which is conserved among the vertebrates (Supplementary Figure S2). We previously studied another ZF protein, ZFTB7A, which contains a four-finger DNA-binding domain (38). Interestingly, ZF3 of ZBTB7A also possesses a Tyr at position −5 (Figure 3A), as well as Asn, Asp and His at base-interacting positions (−1, −4 and − 7). Each of these residues could potentially form base-specific interactions; however, ZF3 of ZBTB7A was not involved in base-specific interactions but served as a spacer to properly position the next finger, ZF4 (38). We superimposed the two Tyr-containing fingers, ZF3 of ZBTB7A and ZF5 of CTCF (Figure 3B). It is evident that the Tyr takes two alternative conformations in these two proteins. With Tyr392 pointing away from the DNA bases in CTCF, Arg at position −1 and Lys at −4 (the two longest side chains) can reach the guanine bases, while the shorter Asp at −7 allows a variable base. With Tyr pointing directly toward the DNA bases in ZBTB7A, the corresponding residues Asn at position −1 and Asp at −4 have side chains too short to reach to the nearest DNA base. In another example, HIC2—a transcription factor required for normal cardiac development (55,56), and which controls developmental hemoglobin switching (57)—contains five fingers at its carboxyl terminus, with ZF4 containing a Tyr at the corresponding −5 position (57). HIC2 is like ZBTB7A, in that the Tyr points toward the DNA (Figure 3D). ZF4 of HIC2 has the two residues, Tyr574 at −5 and Arg572 at −7, contacting the same G:C base pair, forming a four-way interaction (Figure 3E). Among the four examples compared here, there are three types of local stacking of protein side chains: (i) stacking between Arg at −1 and Lys at −4 of CTCF ZF5; (ii) stacking between Gln at −1 and Tyr at −5 of CTCF ZF8 (see below); and (iii) stacking between Tyr at −5 and His at −7 (or Arg at −7) of ZBTB7A ZF3 (or HIC2 ZF4).

Figure 3.

A Tyr at position −5 of ZF5 and ZF8 of CTCF. (A) Sequence alignment of four fingers containing a Tyr at position −5, ZF3 of ZBTB7A, ZF5 and ZF8 of CTCF, and ZF4 of HIC2. The circled basic residues are unique to ZF8 of CTCF. (B) Superimpositions of ZF5 of CTCF with ZF3 of ZBTB7A. The Tyr at position −5 adopted two alternative conformations. (C) Comparison of ZF5 and ZF8 of CTCF. (D) Comparison of ZF5 of CTCF and ZF4 of HIC2. (E) In HIC2, Y at −5 and R at −7 positions interact with the same G:C base pair.

The residue at the −6 position, the first residue of the helix, also makes a cross-strand and cross-triplet interaction, but instead of base recognition it contacts a DNA backbone phosphate group between the second and third base pairs of the next triplet (a circled P indicated in Figure 2A). Lys449 of ZF7 interacts with the DNA phosphate group between G5 and T6 of the second triplet (Figure 2P). Ser419 of ZF6 makes an H-bond with the DNA phosphate group between C8 and C9 (Figure 2Q). Thr391 of ZF5 and Val363 of ZF4 make weak van der Waals contacts with the phosphate groups between C11 and C12 or G14 and A15, respectively (Figure 2R and S). We observed two conformations of Ser334 of ZF3, where one conformation interacts with the phosphate group between C17 and A18 (Figure 2T) and the second conformation (via a rotamer rotation) forms O–H–C type of H-bond with a ring carbon-5 of cytosine at C17 (Figure 2U). Finally, the side chain of Arg278 of ZF1 is disordered because there is no next DNA triplet available in the current structure with which it can interact.

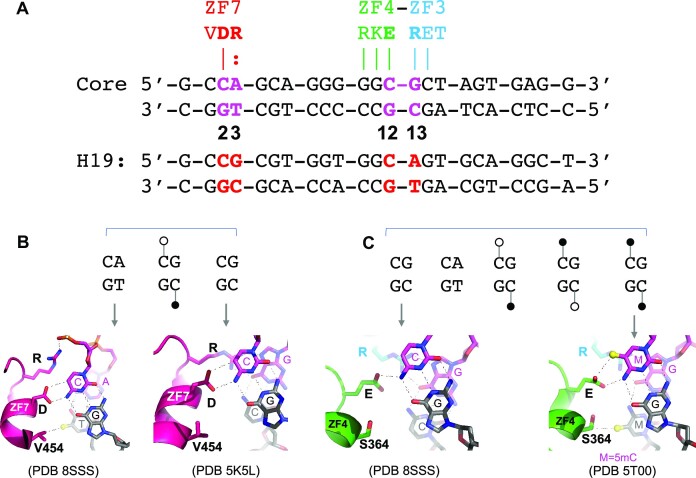

Val454 at position −1 of ZF7 provides a cross-strand interaction with CpA or hemi-methylated CpG

In addition to residues at position −4 making cross-strand interactions, Val454 of ZF7, which is unable to make a direct contact with the C1 of the cognate triplet (Figure 2B), instead makes a hydrophobic contact with the methyl group of T3 on the opposite strand (Figure 2I). This Val is conserved across the vertebrates (Supplementary Figure S2). The Val454–methyl interaction may contribute to CpG methylation-sensitive binding. In fact, others have recently found that Val454 is indeed critical for detecting cytosine methylation (58). A comparative study with bisulfite sequencing data of various human cell types indicated that ∼40% of variable CTCF binding is linked to differential DNA methylation, concentrated at two conserved Cyt positions within the recognition sequence (59), which correspond to the DNA positions 2 and 12 of the CORE sequence we used (Figure 4A). For both cytosine residues, the following 3′ nucleotide is a purine (Gua or Ade), forming a CpG or CpA dinucleotide (e.g. duplex H19 in Figure 4A), which are the canonical sites for cytosine methylation in mammalian DNA (60). The 5-methyl group on 5-methylcytosine is spatially equivalent to the 5-methyl group on T (5-methyluracil), and a number of proteins interact with either base at a given position (61–67).

Figure 4.

Aspartate for cytosine and glutamate for 5-methylcytosine. (A) Either a CpG or CpA site can occur at DNA positions 2 and 3 or 12 and 13. (B) Examples of ZF7 interaction with CpA (PDB 8SSS) or CpG (PDB 5K5L). The interaction of Val454–methyl of thymine of the bottom strand also applies to the hemi-methylated 5mCpG at the bottom strand. (C) Examples of ZF4–ZF3 interactions with unmethylated CpG (PDB 8SSS) or fully methylated 5mCpG (PDB 5T00). The Ser364–methyl interaction applies to bottom strand TpG, hemi- or fully methylated 5mCpG.

The two Cyt bases at positions 2 and 12 of top recognition strand are recognized primarily by Asp451 of ZF7 and Glu362 of ZF4, respectively (Figure 4B and C). However, the CpA or CpG dinucleotides at positions 2 and 3 are recognized by ZF7 alone, while the methylatable dinucleotides at positions 12 and 13 are recognized jointly by ZF4 and ZF3 (Figure 4A). Like other characterized C2H2 ZF proteins in binding methylated DNA [reviewed in (50)], CTCF follows the convention of aspartate for unmodified cytosine with glutamate preferring 5-methylcytosine. Thus, the use of Asp451 in ZF7 and Glu362 in ZF4 resulted in opposite effects on CTCF binding to the H19 imprinting control region sequence, where binding was inhibited by DNA being fully methylated at a single CpG site at positions 2 and 3 (68–70), whereas full methylation at positions 12 and 13 led to slightly enhanced affinity (14). Both Asp451 and Glu362 are fully conserved across the vertebrates (Supplementary Figure S2).

The two Cyt bases at positions 3 and 13 of the bottom pairing strand are contacted by Val454 of ZF7 and Ser364 of ZF4, respectively (Figure 4B and C). Considering that both 5-methylcytosine and thymine contain a methyl group at pyrimidine ring carbon-5, CpA/TpG is intrinsically methylated on one strand (T). ZF7 of CTCF can accommodate not only CpA/TpG, but also hemi-methylated CpG/5mCpG (via a van der Waals contact with Val454) as well as non-methylated CpG/CpG (Figure 4B). In the meantime, ZF4 and ZF3 can bind all five possibilities (unmodified CpG, fully methylated CpG, two hemi-methylated CpGs and CpA) via interactions with Glu362 for the top strand and Ser364 for the bottom strand (Figure 4C). Indeed, a recent study reported that DNA strand-asymmetric CpG methylation has opposing effects on CTCF binding, with both Val454 and Ser364 critical for detecting cytosine methylation of the bottom strand (58). While hemi-methylated CpG is generally considered to be a transient intermediate between the unmethylated and fully methylated states, particularly during DNA replication, stably hemi-methylated CpG sites have been observed in the differentiating mouse embryonic stem cells (71) and at short regions flanking CTCF binding sites in H9 human embryonic stem cells (72). Nevertheless, CTCF binding is methylation sensitive (at C2) and insensitive (at C12), but is promiscuous with respect to the opposite strand at positions 3 (via Val454) and 13 (via Ser364), accepting a thymine, 5-methylcytosine or cytosine. It is perhaps significant that both Ser364 and Val454 are fully conserved in vertebrates, and even in the more divergent human CTCFL (Supplementary Figure S2), which is made in specific tissues at limited times as a competitor to CTCF (73,74).

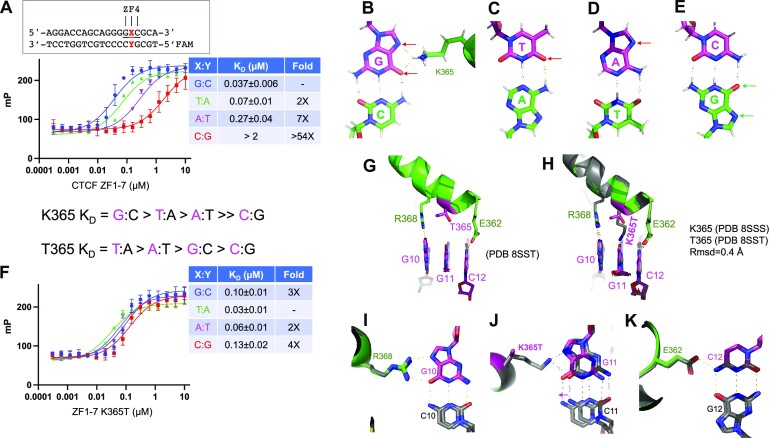

Mutant K365T binds a variable base pair

Increased application of population sequencing has uncovered CTCF mutations throughout the entire CTCF gene, frequently occurring within the DNA binding ZF array, and particularly centered on ZF1, ZF3, ZF4, ZF7 and adjacent residues (Supplementary Figure S1C). These CTCF mutations are associated, for example, with one quarter of endometrial carcinomas (75–77) and other clinical symptoms, including neurodevelopmental disorders, autistic traits and craniofacial abnormalities (78,79). One such mutation, c.1094A>C, results in a substitution of Lys365-to-Thr in ZF4, is a recurrent mutation in endometrial cancer and acts as a gain-of-function mutation enhancing cell survival (80). Lys365, fully conserved among vertebrates, occupies a base-interacting −4 position in ZF4 and recognizes a guanine at base pair position 11 (Figure 2E). We previously showed that the mutant has reduced DNA binding with a G:C base pair at position 11 (14).

Here, we substituted the G:C base pair with each of the other three possible pairs, and measured binding affinities of both wild-type (Lys365) and Thr365 versions of ZF1–ZF7 against the four possible duplex oligos. The wild type binds most strongly to a G:C pair, as expected, followed by T:A (with 2× reduced affinity), A:T (with 7× reduced affinity) and C:G (with >54× reduced affinity) (Figure 5A). This selectivity can be explained by the H-bonding pattern of Lys365, which donates a proton to either the N7 nitrogen atom or O6 oxygen atom of the guanine ring, both of which are proton acceptors (Figure 5B). In the cases of T:A or A:T, both harbor one proton acceptor at the O4 atom of thymine or N7 of adenine (indicated by red arrows in Figure 5C and D). However, for a C:G base pair, the potential proton acceptors shift from the recognition strand to the opposite strand (the green colored guanine in Figure 5E). Thus, Lys365 at the −4 position excludes the cytosine of a C:G base pair.

Figure 5.

Structure of K365T mutant in complex with DNA. (A) DNA binding of ZF1–ZF7 (wild type) was quantified by fluorescence polarization. (B) Lys365 provides a proton donor to either N7 nitrogen or O6 oxygen of the guanine ring (indicated by two red arrows). The hydrogen atoms (in gray) are depicted for illustration. (C–E) Base pairs of T:A, A:T and C:G with recognition base in magenta, and opposite pairing base in green. The proton acceptors located in the DNA major groove side are indicated by the arrows and hydrogen atoms are included for illustration. (F) DNA binding affinities of K365T were measured against four possible base pairs at cognate triplet. (G) Structure of K365T of ZF4 in complex with 5′-GCG-3′ triplet. (H) Superimposition of ZF4 wild type and K365T mutant. (I–K) Superimposition of ZF4 wild type and K365T mutant with the cognate triplet.

In contrast, the Thr365 mutant binds the T:A oligo about as well as the wild type binds G:C (KD = 0.03–0.04 μM under the experimental conditions used), and the binding affinities are in a narrow range (2–4×) in a decreased order of T:A > A:T > G:C > C:G (Figure 5F). Next, we determined a structure of the mutant in complex with the same DNA used in the wild-type protein (Figure 5G), to a resolution of 2.19 Å (Supplementary Table S1). The two structures are highly similar, with an rmsd of just 0.4 Å, except for the side chain of Thr365 itself (Figure 5H). The Thr365 side chain is too short to reach the base (Figure 5G), while the two neighboring base pairs are held tightly in place by Arg368 and Glu362 (Figure 5I and K). Lack of any specific interaction with the G:C at base pair position 11 allowed the base pair to move slightly toward the protein (Figure 5J). Like Thr421 of ZF6 and Thr333 of ZF3, Thr365 of ZF4 can accommodate all four possible base pairs, which might allow the mutant to bind additional sites in the genome and perhaps explain the gain of function, though in theory the possible greatly expanded number of binding sites might deplete the mutant CTCF, such that gain of function is due to loss of binding low-affinity sites.

ZF8 in the structure of ZF3–ZF11 of CTCF bound to DNA

Previously, we crystallized CTCF fragments ZF4–ZF10 and ZF4–ZF11 in complex with a 28-bp duplex (14). In both cases, the C-terminal fingers 10 and 11 were not observed in the electron density and ZF9 was flexible. ZF8 appeared to serve, at least in these shorter fragments as well as in a fragment of ZF6–ZF11 (15), as a spacer, spanning the minor groove. Here, we used a ZF3–ZF11 polypeptide, and designed a series of oligos starting from 19 bp (a minimal length for the six fingers ZF3–ZF8 to occupy) up to 36 bp, with increments of 1 bp (and often varying sequence) at a time, toward the 5′ end upstream of the CORE sequence (labeled as base pair positions −1 to −18 in Figure 6A). We kept the recognition sequence for ZF3–ZF7 (positions 1–15) the same as we used in ZF1–ZF7 studies. We screened ∼600 crystals for X-ray diffraction; most of them had low resolution, missing fingers or DNA base pairs in electron densities. We determined two structures of ZF3–ZF11 with one of the two 35-bp oligos (Supplementary Table S1), with only one variation of G:C or T:A at CORE base pair position 9, both of which are accepted in the consensus sequence and which did not affect crystal quality. The two structures of the 35-bp duplex complexed with ZF3–ZF11 were isomorphic at the resolution of 3.1 Å, and here we describe the 35-bp structure (with G:C at position 9—the same sequence used in ZF1–ZF7). Like ZF1–ZF7 complexed with DNA, the ZF3–ZF11 in complex with DNA was crystallized with two protein–DNA complexes in the crystallographic asymmetric unit (Supplementary Figure S3C and D).

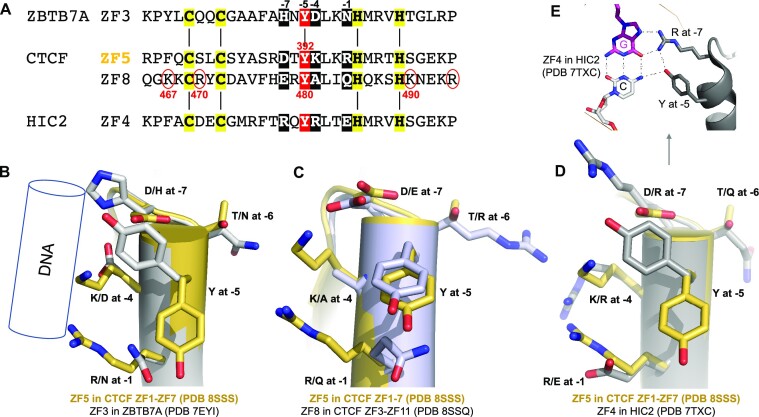

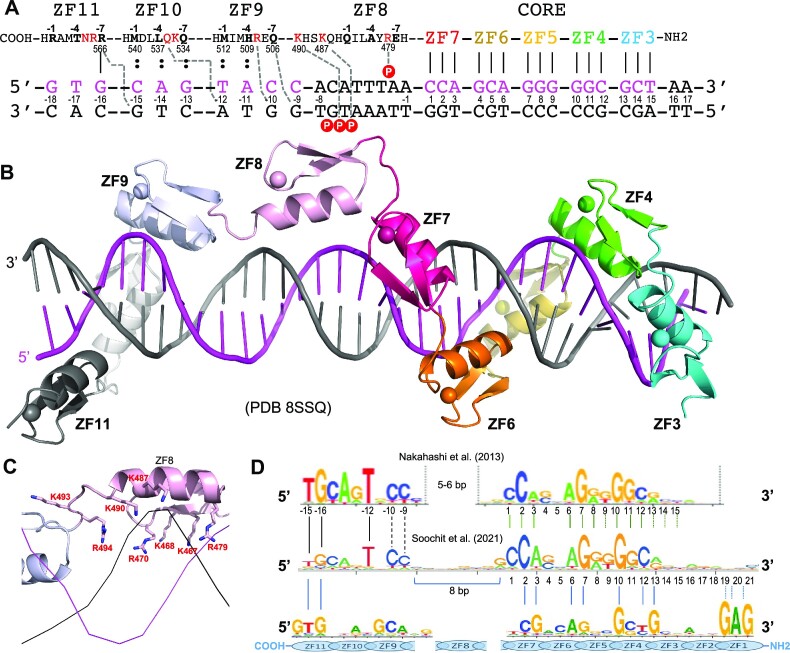

Figure 6.

Structure of CTCF ZF3–ZF11 in complex with DNA. (A) A 35-bp DNA oligo was used in the crystallization with ZF3–ZF11. The DNA base pairs are numbered from 1 to 17 (to the left) for recognition by ZF3–ZF7 and from −1 to −18 (to the right) for recognition by ZF8–ZF11. (B) Structure of CTCF ZF3–ZF11 in complex with DNA. ZF8 is in the center. (C) ZF8 has eight basic residues (including the linker) engaging in DNA phosphate backbone interactions. (D) Realignment between the predicted DNA-binding specificity of CTCF ZF1–ZF11 with the actual consensus sequence that has extended 5′ upstream sequence.

As expected, the first five fingers, ZF3–ZF7, follow the right-handed twist of the DNA, with the α helices occupying the major groove in a path of 3′ to 5′ of the recognition strand (magenta in Figure 6B). However, instead of continuing in the DNA major groove, ZF8 spans the minor groove for ∼7–8 bp and provides five basic/polar residues (Arg470, Tyr471, Arg479, Lys487 and Lys490) that interact with four DNA backbone phosphate groups across the two strands, with three of the four on the non-recognition strand (Figure 6C).

As mentioned above, like ZF5, ZF8 also contains a tyrosine at position −5 (Figures 1B and 3A). Superimposing the two fingers, ZF5 and ZF8, revealed Tyr at −5 taking similar conformations (Figure 3C), so apparently the Tyr at −5 alone was not the primary reason that ZF8 failed to bind within the major groove. We note that, excluding the base-interacting Arg/Lys residues at positions −1, −4 and −7, ZF8 has the largest number of basic residues (seven) [followed by six (ZF9), five (ZF2, ZF3 and ZF10), four (ZF4, ZF5 and ZF7), three (ZF6 and ZF11) and two (ZF1)] (Figure 1B). Importantly, seven basic residues plus Arg494 of the linker between ZF8 and ZF9 point toward and make phosphate interactions across minor groove DNA (Figure 6C). In addition, ZF8 is the only one immediately preceded by a glycine (Gly466) in the inter-finger linker (see the ‘Discussion’ section).

At least three basic residues at positions outside of −1, −4 and −7 are unique to ZF8: Lys467, Arg470 and Lys490 (Figure 1B). Among vertebrates, the latter two are fully conserved, while Lys467 is a basic Arg in zebrafish, but a Leu in CFCTL (Supplementary Figure S2). In the corresponding position to Lys467 of ZF8, all the other 10 fingers in CTCF have a Phe, Tyr or His as the first residue of the first β-strand. This side chain packs between the β-strand and the helix and provides stability for the finger (Supplementary Figure S4). In three fingers (ZF3, ZF4 and ZF6), when the finger gets deep into the DNA major groove, the corresponding His, Phe or Tyr provides an H-bond or van der Waals contact to the phosphate group of the non-recognition strand (Supplementary Figure S4). In the corresponding position of Arg470 in ZF8, between the two zinc-liganded Cys residues, all the other 10 fingers have variable amino acids, ranging from negatively charged Glu (ZF1) and Asp (ZF9), through polar residues His (ZF2) and Tyr (ZF6), to small amino acids Pro (ZF3) and Ser (ZF4, ZF5, ZF10 and ZF11) (Figure 1B). Unlike Arg470, all of them point away from the bound DNA and are exposed to solvent. In the corresponding position of Lys490 of ZF8, located immediately after the last zinc-liganded His (or Cys in ZF11), nine fingers have Thr/Ser/Ala and one finger (ZF10) has Asp (Figure 1B). Again, unlike Lys490, all of them point away from the bound DNA and are exposed to solvent. In contrast, Arg470 and Lys490 point toward the DNA, and allow ZF8 to interact with negatively charged DNA phosphate groups across both strands. By expanding ZF8 to cover ∼8 bp, we could recapture the predicted DNA-binding specificity of CTCF ZF1–ZF11 to partially match the actual consensus sequence that has extended 5′ upstream sequence (26–28) (Figure 6D).

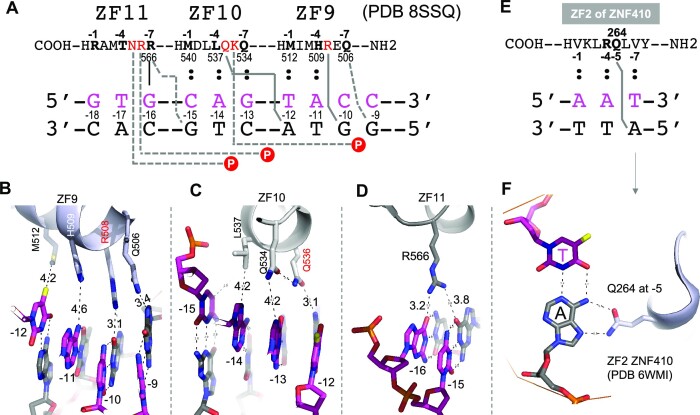

ZF9–ZF11 in the structure of ZF3–ZF11 of CTCF bound to DNA

After ZF8, ZF9–ZF11 are repositioned to enter the major groove (Figure 6B). ZF9 occupies four base pairs −9 to −12 (Figure 7A). Gln506 at −7 and Arg508 at −5 in ZF9 make cross-strand interactions with G(−9) and G(−10) (Figure 7B). The large side chain of conserved residue Arg508 pushes the helix of ZF9 away from the DNA base interface, and weakens the other interactions (increasing the spacing distances) between His509 at −4 and A(−11) and between Met512 at −1 and T(−12). Similarly, conserved residue Gln536 at −5 of ZF10 makes a cross-strand interaction with A(−12) (Figure 6C), weakening the interactions of Gln534 at −7, Leu537 at −4 and Met540 at −1 with an increased distance (4.2–5.0 Å) to their corresponding bases. Finally, Arg566 at −7 of ZF11 makes two weak H-bonds with G(−15) and G(−16) across two strands (Figure 7D), while Arg567 at −6 and Asn568 at −5 make two phosphate contacts of the non-recognition strand. Arg566 is fully conserved among vertebrates, even in human CFCTL (Supplementary Figure S2), and its mutation is associated with CTCF-related disorder (79). On the other hand, in the current structure, Thr569 at −4 and Arg572 at −1 of ZF11 are located >6 and >10 Å, respectively, away from their corresponding DNA bases. In sum, the larger side chains of residues at −5 of ZF9 and ZF10 (Arg508 of ZF9 and Gln536 of ZF10) make cross-strand base-specific interactions with guanine and adenine, respectively, and provide base specificity for the corresponding T:A at position −12 and C:G at −10. This observation agrees with experimentally derived consensus sequences (26,28). This situation is different from the ‘versatile’ contacts made by smaller side chains (e.g. Ser) at position −5, as discussed for ZF1–ZF7.

Figure 7.

ZF9–ZF11 have cross-strand interactions contributing to base recognition. (A) Schematic of interactions involving ZF9–ZF11 of CTCF. (B) ZF9 spans 4 bp, with Gln506 (−7) and Arg508 (−5) making cross-strand base interactions with adenine and guanine, respectively. (C) ZF10 spans 4 bp, with Gln536 (−5) making cross-strand adenine interaction. Met540 of ZF10 is further away from the viewer and invisible at this viewpoint. (D) Arg566 of ZF11 crisscrosses two guanines at two neighboring base pairs. (E, F) Gln264 at −5 of ZF2 in ZNF410 makes a cross-strand adenine-specific interaction.

The cross-strand specificity made by a residue at position −5 has been observed previously in transcription factor ZNF410, which controls CHD4 gene expression in erythroid cells (81,82). ZNF410 contains five tandem ZFs, and ZF2 has a Gln at the corresponding −5 position (Figure 7E). Gln264 at −5 of ZF2 in ZNF410 makes an across-strand interaction with an adenine (Figure 7F), similar to Gln536 at −5 of ZF10 in CTCF (Figure 7C). We note that the Gln–Ade cross-strand adenine-specific interaction occurs in the two examples of fingers having two hydrophobic residues occupying potential base-interacting positions (Met at −1 and Leu at −4 of ZF10 in CTCF, and Val at both −1 and −7 of ZF2 in ZNF410). It is possible that when the cognate positions at −1, −4 and −7 cannot provide base-specific contacts, the larger residues (Arg and Gln) at position −5 compensate for loss of the expected specific contacts.

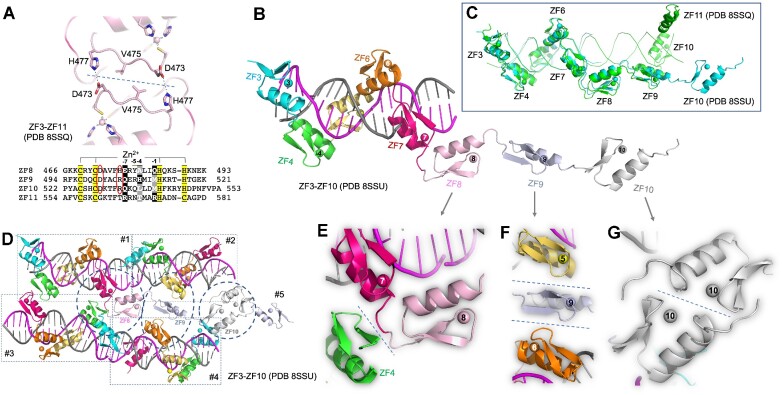

ZF-mediated protein–protein interactions in the crystals

As mentioned earlier, ZF1–ZF7 and ZF3–ZF11 were crystallized in complex with their respective DNA duplexes with two protein–DNA complexes per crystallographic asymmetric unit (Supplementary Figure S3). In the case of ZF1–ZF7, ZF4 mediated the protein–protein interactions, and in the case of ZF3–ZF11, ZF8 did (Supplementary Figure S3). Among the hundreds of ZF3–ZF11/DNA cocrystals we screened (including many of them we decided not to pursue further because of lower resolutions), the two reciprocal pairs of Asp473 and His477 of ZF8 are the most common protein–protein interactions we inspected (Figure 8A), including a previously characterized structure (PDB 5UND) involving ZF8 (14). This intermolecule interaction is possible only for two CTCF molecules running antiparallel to one another (Supplementary Figure S3C and D), and was not present in two CTCF molecules running in parallel [PDB 5YE1 (15)]. We note that this reciprocal Asp–His interaction in ZF8 could also occur in ZF9 and ZF10 via replacement with Asp501–Arg505 of ZF9 and Asp529–Arg533 of ZF10 (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

ZF-mediated protein–protein interactions in the crystals. (A) In the structure of ZF3–ZF11 (PDB 8SSQ), two reciprocal pairs of Asp473–His477 of ZF8 mediate interprotein interactions. (B) Structure of ZF3–ZF10 in complex with a 19-bp duplex DNA (PDB 8SSU). ZF11 was not observed in the electron density. (C) Superimposition of ZF3–ZF10 (complex with 19 bp; colored cyan, PDB 8SSU) and ZF3–ZF11 (complexed with 35-bp DNA; colored green, PDB 8SSQ). (D) Four protein–DNA complexes in the crystal of PDB (8SSU), each complex boxed in a dashed rectangle and numbered as #1, #2, #3 and #4. For simplicity, ZF8–ZF10 are removed from complexes #2–#4, whereas ZF8–ZF10 of complex #1 are labeled and the interactions with the neighboring molecules are circled. In addition, complex #5 appeared with only ZF9–ZF10. (E) The inter-finger linker between ZF7 and ZF8 of complex #1 interacts with ZF4 of complex #3. (F) ZF9 of complex #1 interacts with ZF5 of complex #2 and ZF6 of complex #4. (G) ZF10 of complex #1 interacts with ZF10 of complex #5.

In addition, we crystallized ZF3–ZF11 with a shorter 19-bp duplex DNA, which allowed ZF3–ZF7 to bind DNA, while ZF8–ZF10 form a linear array without any DNA contact (Figure 8B) and no electron density was observable for ZF11. Superimposition onto ZF3–ZF11 with the 35-bp duplex DNA revealed that DNA-bound ZF3–ZF7 is well aligned, ZF8 and even ZF9 stay at similar locations, while ZF10 points away in varied directions (Figure 8C). In the absence of bound DNA, ZF8–ZF10 were packed against neighboring complexes via protein–protein interactions (Figure 8D). Three types of interactions were observed. First, the inter-finger linker between ZF7 and ZF8 interacts with the first β-strand of ZF4 from the neighboring molecule (Figure 8E). Second, the hairpin β-strands of ZF9 interact with two neighboring molecules, with the corresponding hairpin β-strands of ZF5 and ZF6, respectively (Figure 8F). Third, the hairpin loop of ZF10 interacts with the C-terminal end of helix of ZF10 of the neighboring molecule (Figure 8G). Taken together, it is the hairpin β-strands of individual fingers that are involved in protein–protein interactions, at least in the context of crystals. This is understandable because the antiparallel hairpin β-strands lie away from the bound DNA and on the outer surface of the protein–DNA complex. Finally, the observed protein–protein interactions within the crystals do not appear to be affecting the protein–DNA interactions involving ZF3–ZF7.

DISCUSSION

Here, we described two structures of CTCF in complex with DNA, including the CORE sequence together with either 3′ downstream or 5′ upstream motifs. As anticipated by others (26–28), ZF1 binds to the 3′ GAG triplet, while ZF8–ZF11 bind to the 5′ motif. One difference is that ZF1–ZF7 bind a continuous DNA element from the CORE to the 3′ downstream motif without a spacer, unlike what was reported in (26) with respect to the distance between the CORE and the 3′ motif (see Figure 1A). If this were to happen with a spacer, the CORE and the 3′ motif would have to be bound by two separate CTCF molecules.

Unique positioning of ZF8

The positioning of ZF8 away from the DNA bases in the major groove, unlike all the other 10 ZFs, and spanning ∼8 bp in the minor groove, is consistent with the results of a study that examined the effects of deletion of individual ZFs of CTCF (28). Among the CTCF proteins with deletions that allow cell survival, the ΔZF8 mutant protein showed the most significant loss of CTCF binding, compared to deletions of ZF1, ZF9, ZF10 or ZF11, whereas CTCF proteins containing individual deletions of ZF2–ZF7 failed to rescue the cell lethality (28). This observation by deletion is in general agreement with at least two studies using point mutagenesis of CTCF on interactions with DNA (26,83). Specifically, while effects varied with the DNA tested, in general mutation of ZF4–ZF7 had lowest occupancy (26) or ZF3–ZF7 and ZF11 had the strongest negative effects on binding (83). Together, these studies suggest that the fingers (ZF3–ZF7) responsible for the CORE sequence recognition are essential.

Although ZF8 is not directly involved in DNA base interactions, the presence of ZF8 increases nonspecific DNA binding in vitro (14) and a ΔZF8 mutant CTCF exhibited decreased chromatin residence time, resulting in altered interactions at a subset of CTCF loops (28). It is interesting that a prediction method for C2H2 ZFs (42) gave the lowest score to ZF8 out of all 11 fingers (Figure 1B).

As noted above, ZF8 is uniquely rich in basic amino acids, which allows salt bridges to DNA phosphates in the minor groove. In addition, ZF8 is the only one immediately preceded by glycine (Gly466), the most flexible residue, in the position occupied by proline (the least flexible residue) in 6 of the remaining 10 ZFs (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S5). We note that there are no specific intra- or intermolecular interactions involving Gly466 of ZF8 or its corresponding prolines in the structures we have examined so far.

Another functional variation among the ZFs in which ZF8 stands out involves phosphorylation, which reduces CTCF DNA binding during mitosis (84). In 8 of the 11 ZFs in CTCF, the last Zn-coordinating His ligand is immediately followed by a Ser or Thr, and 7 of these 8 are subject to phosphorylation (84) (see Supplementary Figure S2). In the corresponding position of these Ser or Thr residues, ZF8 has a unique lysine (Lys490), which makes a DNA phosphate contact.

One might expect that ZF8, being more exposed to solvent in the DNA complex, would play other roles, such as in protein–RNA or protein–protein interactions, but ZF8 is dispensable for RNA binding (85). Regarding interaction with other proteins, when two CTCF binding sites are pulled by DNA loop extrusion, two CTCF-bound DNA complexes would collide either directly or through cohesin or other proteins. Here, we show in the crystal lattice that CTCF ZFs, particularly ZF8–ZF10, can engage in direct protein–protein interactions (Figure 8), which might be relevant to self-interactions of the CTCF DNA-binding domain (86). Moreover, ZF9–ZF11 facilitate CTCF multimerization (85). It remains to be determined whether these protein–protein interactions contribute to the organizational principles of 3D genome architecture.

While the features of ZF8 described just above are intriguing, it remains to be determined exactly which features would allow prediction of which ZFs could function as spacers, like ZF8. We have seen a similar spacer in Zfp568 (52), in which ZF2 spans the DNA minor groove at an AT-rich stretch [where the minor groove is narrower (52)], and in ZBTB24 (87), in which ZF4 spans the DNA major groove. ZBTB24 is one of four known genes that are mutated in immunodeficiency, centromeric instability and facial anomalies syndrome, a genetic disorder characterized by DNA hypomethylation and antibody deficiency (88–90). ZBTB24 contains eight tandem ZFs, and the last four of the eight fingers (ZF5–ZF8) are sufficient to bind the 12–13 bp consensus, whereas the three N-terminal fingers ZF2–ZF4 contain large and charged side chains (KH or KR) at the corresponding positions −6 and −5 (87), just like ZF8–ZF11 of CTCF (Figure 1B). In a structure of ZF4–ZF8 of ZBTB24 bound with DNA, ZF4 is a spacer with the two residues at the potential base-interacting positions instead making DNA phosphate contacts on the non-recognition strand (Supplementary Figure S1D). Unlike ZF8 of CTCF, which spans the minor groove, ZF4 of ZBTB24 spans the DNA major groove. However, there is no clear sequence similarity between the two spacer ZFs, except for the large and charged side chains at the corresponding positions −6 and −5.

The cross-strand base-specific interaction by residue at position −5 of ZF

Ever since the determination of the first structure reported for a three-finger ZF protein in complex with DNA >30 years ago (91), the DNA recognition process has been sufficiently understood to define a DNA recognition code for ZF proteins (46,47). This code led to designed ZF nucleases for genomic engineering (43). However, it is evident from our study that the prediction of DNA-binding specificity for ZF arrays containing large side chains at the positions −6 and −5 of ZF unit is not accurate. Our structure revealed that highly specific Arg–Gua and Gln–Ade interactions used for recognizing G:C or A:T base pairs at conventional base-interacting positions (−1, −4 and −7) also apply to position −5 but in a cross-strand fashion. We do note that the base-specific contacts by larger and charged/polar residues (Arg and Gln) at position −5 might compensate when the cognate positions at −1, −4 and −7 (small or hydrophobic residues) cannot provide specificity.

Summary

In sum, our detailed study of CTCF in complex with DNA provides a closer look of the individual ZF in binding DNA. Among the 11 fingers of CTCF, ZF1–ZF7 contain small residues (Gly, Val, Ser and Thr) at positions −5 or −6 or both, and follow the right-handed twist of the DNA, with each finger occupying and recognizing a 3-bp triplet. ZF8–ZF11 contain bulkier and polar/charged residues (Arg, Lys, Glu, Asn, Gln or Tyr) at both positions. ZF8 acts as a spacer to place ZF9–ZF11 properly for cross-strand contacts with DNA. The binding sites possessing both parts would be occupied with higher affinity by CTCF to counteract competitive processes. Future work with CTCF-related disorder carrying mutations in ZF9, ZF10 or ZF11 (78,79) will reveal the effect of these mutations in cell differentiation processes during development.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Yu Cao of MDACC for technical assistance. We thank the beamline scientists of Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory. The use of SER-CAT is supported by its member institutions and equipment grants (S10_RR25528, S10_RR028976 and S10_OD027000) from the National Institutes of Health. Use of the APS was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract W-31-109-Eng-38. X.C. is a CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research.

Authors’ contributions: J.Y. performed CTCF expression, purification, mutagenesis, DNA binding and crystallization. J.R.H. performed X-ray data collection and structure determination. B.L. performed motif analysis. R.M.B. performed bioinformatics and participated in discussion, writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. V.G.C. participated in discussion and provided his expertise and knowledge on CTCF. X.Z. provided supervision, conceptualization and project administration. X.C. organized and designed the scope of the study, and performed writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript, conceptualization and funding acquisition.

Contributor Information

Jie Yang, Department of Epigenetics and Molecular Carcinogenesis, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

John R Horton, Department of Epigenetics and Molecular Carcinogenesis, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Bin Liu, Department of Epigenetics and Molecular Carcinogenesis, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Victor G Corces, Department of Human Genetics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Robert M Blumenthal, Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, and Program in Bioinformatics, The University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 43614, USA.

Xing Zhang, Department of Epigenetics and Molecular Carcinogenesis, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Xiaodong Cheng, Department of Epigenetics and Molecular Carcinogenesis, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The experimental data that support the findings of this study are contained within the article. The authors have deposited the X-ray structure (coordinates) and the source data (structure factor file) of CTCF–DNA to the PDB, and these will be released upon article publication under accession numbers PDB 8SSS (ZF1–ZF7 and oligo 23 bp), PDB 8SST (K365T and oligo 23 bp), PDB 8SSQ (ZF3–ZF11 and oligo 35-4), PDB 8SSR (ZF3–ZF11 and oligo 35-20) and PDB 8SSU (ZF3–ZF10 and oligo 19 bp).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health [R35GM134744 to X.C.]; Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) [RR160029 to X.C.]. The open access publication charge for this paper has been waived by Oxford University Press – NAR Editorial Board members are entitled to one free paper per year in recognition of their work on behalf of the journal.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lobanenkov V.V., Nicolas R.H., Adler V.V., Paterson H., Klenova E.M., Polotskaja A.V., Goodwin G.H.. A novel sequence-specific DNA binding protein which interacts with three regularly spaced direct repeats of the CCCTC-motif in the 5′-flanking sequence of the chicken c-myc gene. Oncogene. 1990; 5:1743–1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dehingia B., Milewska M., Janowski M., Pekowska A.. CTCF shapes chromatin structure and gene expression in health and disease. EMBO Rep. 2022; 23:e55146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Ruiten M.S., Rowland B.D.. On the choreography of genome folding: a grand pas de deux of cohesin and CTCF. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2021; 70:84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Agrawal P., Rao S.. Super-enhancers and CTCF in early embryonic cell fate decisions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021; 9:653669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fedoriw A.M., Stein P., Svoboda P., Schultz R.M., Bartolomei M.S.. Transgenic RNAi reveals essential function for CTCF in H19 gene imprinting. Science. 2004; 303:238–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heath H., Ribeiro de Almeida C., Sleutels F., Dingjan G., van de Nobelen S., Jonkers I., Ling K.W., Gribnau J., Renkawitz R., Grosveld F.et al.. CTCF regulates cell cycle progression of αβ T cells in the thymus. EMBO J. 2008; 27:2839–2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nora E.P., Goloborodko A., Valton A.L., Gibcus J.H., Uebersohn A., Abdennur N., Dekker J., Mirny L.A., Bruneau B.G.. Targeted degradation of CTCF decouples local insulation of chromosome domains from genomic compartmentalization. Cell. 2017; 169:930–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arzate-Mejia R.G., Recillas-Targa F., Corces V.G.. Developing in 3D: the role of CTCF in cell differentiation. Development. 2018; 145:dev137729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mamberti S., Pabba M.K., Rapp A., Cardoso M.C., Scholz M.. The chromatin architectural protein CTCF is critical for cell survival upon irradiation-induced DNA damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022; 23:3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kang M.A., Lee J.S.. A newly assigned role of CTCF in cellular response to broken DNAs. Biomolecules. 2021; 11:363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sivapragasam S., Stark B., Albrecht A.V., Bohm K.A., Mao P., Emehiser R.G., Roberts S.A., Hrdlicka P.J., Poon G.M.K., Wyrick J.J.. CTCF binding modulates UV damage formation to promote mutation hot spots in melanoma. EMBO J. 2021; 40:e107795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heger P., Marin B., Bartkuhn M., Schierenberg E., Wiehe T.. The chromatin insulator CTCF and the emergence of metazoan diversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012; 109:17507–17512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rowley M.J., Corces V.G.. Organizational principles of 3D genome architecture. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018; 19:789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hashimoto H., Wang D., Horton J.R., Zhang X., Corces V.G., Cheng X.. Structural basis for the versatile and methylation-dependent binding of CTCF to DNA. Mol. Cell. 2017; 66:711–720.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yin M., Wang J., Wang M., Li X., Zhang M., Wu Q., Wang Y.. Molecular mechanism of directional CTCF recognition of a diverse range of genomic sites. Cell Res. 2017; 27:1365–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kung J.T., Kesner B., An J.Y., Ahn J.Y., Cifuentes-Rojas C., Colognori D., Jeon Y., Szanto A., del Rosario B.C., Pinter S.F.et al.. Locus-specific targeting to the X chromosome revealed by the RNA interactome of CTCF. Mol. Cell. 2015; 57:361–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hansen A.S., Hsieh T.S., Cattoglio C., Pustova I., Saldana-Meyer R., Reinberg D., Darzacq X., Tjian R.. Distinct classes of chromatin loops revealed by deletion of an RNA-binding region in CTCF. Mol. Cell. 2019; 76:395–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saldana-Meyer R., Rodriguez-Hernaez J., Escobar T., Nishana M., Jacome-Lopez K., Nora E.P., Bruneau B.G., Tsirigos A., Furlan-Magaril M., Skok J.et al.. RNA interactions are essential for CTCF-mediated genome organization. Mol. Cell. 2019; 76:412–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Y., Haarhuis J.H.I., Sedeno Cacciatore A., Oldenkamp R., van Ruiten M.S., Willems L., Teunissen H., Muir K.W., de Wit E., Rowland B.D.et al.. The structural basis for cohesin–CTCF-anchored loops. Nature. 2020; 578:472–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davidson I.F., Barth R., Zaczek M., van der Torre J., Tang W., Nagasaka K., Janissen R., Kerssemakers J., Wutz G., Dekker C.et al.. CTCF is a DNA-tension-dependent barrier to cohesin-mediated loop extrusion. Nature. 2023; 616:822–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fudenberg G., Abdennur N., Imakaev M., Goloborodko A., Mirny L.A.. Emerging evidence of chromosome folding by loop extrusion. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 2017; 82:45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marina-Zarate E., Rodriguez-Ronchel A., Gomez M.J., Sanchez-Cabo F., Ramiro A.R.. Low-affinity CTCF binding drives transcriptional regulation whereas high-affinity binding encompasses architectural functions. iScience. 2023; 26:106106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hansen A.S., Pustova I., Cattoglio C., Tjian R., Darzacq X.. CTCF and cohesin regulate chromatin loop stability with distinct dynamics. eLife. 2017; 6:e25776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jothi R., Cuddapah S., Barski A., Cui K., Zhao K.. Genome-wide identification of in vivo protein–DNA binding sites from ChIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008; 36:5221–5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rhee H.S., Pugh B.F.. Comprehensive genome-wide protein–DNA interactions detected at single-nucleotide resolution. Cell. 2011; 147:1408–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nakahashi H., Kwon K.R., Resch W., Vian L., Dose M., Stavreva D., Hakim O., Pruett N., Nelson S., Yamane A.et al.. A genome-wide map of CTCF multivalency redefines the CTCF code. Cell Rep. 2013; 3:1678–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang H., Zhu Q., Jussila A., Han Y., Bintu B., Kern C., Conte M., Zhang Y., Bianco S., Chiariello A.M.et al.. CTCF mediates dosage- and sequence-context-dependent transcriptional insulation by forming local chromatin domains. Nat. Genet. 2021; 53:1064–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soochit W., Sleutels F., Stik G., Bartkuhn M., Basu S., Hernandez S.C., Merzouk S., Vidal E., Boers R., Boers J.et al.. CTCF chromatin residence time controls three-dimensional genome organization, gene expression and DNA methylation in pluripotent cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021; 23:881–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patel A., Hashimoto H., Zhang X., Cheng X.. Characterization of how DNA modifications affect DNA binding by C2H2 zinc finger proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2016; 573:387–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Otwinowski Z., Borek D., Majewski W., Minor W.. Multiparametric scaling of diffraction intensities. Acta Crystallogr. A. 2003; 59:228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Afonine P.V., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Moriarty N.W., Mustyakimov M., Terwilliger T.C., Urzhumtsev A., Zwart P.H., Adams P.D.. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012; 68:352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Read R.J., Adams P.D., Arendall W.B. 3rd, Brunger A.T., Emsley P., Joosten R.P., Kleywegt G.J., Krissinel E.B., Lutteke T., Otwinowski Z.et al.. A new generation of crystallographic validation tools for the Protein Data Bank. Structure. 2011; 19:1395–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Emsley P., Cowtan K.. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004; 60:2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkoczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Hung L.W., Kapral G.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W.et al.. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010; 66:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCoy A.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Adams P.D., Winn M.D., Storoni L.C., Read R.J.. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007; 40:658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Terwilliger T.C., Adams P.D., Read R.J., McCoy A.J., Moriarty N.W., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Afonine P.V., Zwart P.H., Hung L.W.. Decision-making in structure solution using Bayesian estimates of map quality: the PHENIX AutoSol wizard. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2009; 65:582–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li J., Huang K., Hu G., Babarinde I.A., Li Y., Dong X., Chen Y.S., Shang L., Guo W., Wang J.et al.. An alternative CTCF isoform antagonizes canonical CTCF occupancy and changes chromatin architecture to promote apoptosis. Nat. Commun. 2019; 10:1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang Y., Ren R., Ly L.C., Horton J.R., Li F., Quinlan K.G.R., Crossley M., Shi Y., Cheng X.. Structural basis for human ZBTB7A action at the fetal globin promoter. Cell Rep. 2021; 36:109759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gupta S., Singh A.K., Prajapati K.S., Kushwaha P.P., Shuaib M., Kumar S.. Emerging role of ZBTB7A as an oncogenic driver and transcriptional repressor. Cancer Lett. 2020; 483:22–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Michalek J.L., Besold A.N., Michel S.L.. Cysteine and histidine shuffling: mixing and matching cysteine and histidine residues in zinc finger proteins to afford different folds and function. Dalton Trans. 2011; 40:12619–12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ok K., Filipovic M.R., Michel S.L.J.. Targeting zinc finger proteins with exogenous metals and molecules: lessons learned from tristetraprolin, a CCCH type zinc finger. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021; 2021:3795–3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Persikov A.V., Singh M.. De novo prediction of DNA-binding specificities for Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chandrasegaran S., Carroll D. Origins of programmable nucleases for genome engineering. J. Mol. Biol. 2016; 428:963–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Persikov A.V., Rowland E.F., Oakes B.L., Singh M., Noyes M.B.. Deep sequencing of large library selections allows computational discovery of diverse sets of zinc fingers that bind common targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:1497–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Persikov A.V., Wetzel J.L., Rowland E.F., Oakes B.L., Xu D.J., Singh M., Noyes M.B.. A systematic survey of the Cys2His2 zinc finger DNA-binding landscape. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:1965–1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Choo Y., Klug A.. Physical basis of a protein–DNA recognition code. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1997; 7:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wolfe S.A., Nekludova L., Pabo C.O.. DNA recognition by Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000; 29:183–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Luscombe N.M., Laskowski R.A., Thornton J.M.. Amino acid–base interactions: a three-dimensional analysis of protein–DNA interactions at an atomic level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29:2860–2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu Y., Zhang X., Blumenthal R.M., Cheng X.. A common mode of recognition for methylated CpG. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013; 38:177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ren R., Horton J.R., Zhang X., Blumenthal R.M., Cheng X.. Detecting and interpreting DNA methylation marks. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018; 53:88–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yang J., Zhang X., Blumenthal R.M., Cheng X.. Detection of DNA modifications by sequence-specific transcription factors. J. Mol. Biol. 2020; 432:1661–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Patel A., Yang P., Tinkham M., Pradhan M., Sun M.A., Wang Y., Hoang D., Wolf G., Horton J.R., Zhang X.et al.. DNA conformation induces adaptable binding by tandem zinc finger proteins. Cell. 2018; 173:221–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patel A., Horton J.R., Wilson G.G., Zhang X., Cheng X.. Structural basis for human PRDM9 action at recombination hot spots. Genes Dev. 2016; 30:257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dougherty D.A. The cation–pi interaction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013; 46:885–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dykes I.M., van Bueren K.L., Ashmore R.J., Floss T., Wurst W., Szumska D., Bhattacharya S., Scambler P.J.. HIC2 is a novel dosage-dependent regulator of cardiac development located within the distal 22q11 deletion syndrome region. Circ. Res. 2014; 115:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dykes I.M., van Bueren K.L., Scambler P.J.. HIC2 regulates isoform switching during maturation of the cardiovascular system. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018; 114:29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Huang P., Peslak S.A., Ren R., Khandros E., Qin K., Keller C.A., Giardine B., Bell H.W., Lan X., Sharma M.et al.. HIC2 controls developmental hemoglobin switching by repressing BCL11A transcription. Nat. Genet. 2022; 54:1417–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thomas S.L., Xu T.H., Carpenter B.L., Pierce S.E., Dickson B.M., Liu M., Liang G., Jones P.A.. DNA strand asymmetry generated by CpG hemimethylation has opposing effects on CTCF binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51:5997–6005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang H., Maurano M.T., Qu H., Varley K.E., Gertz J., Pauli F., Lee K., Canfield T., Weaver M., Sandstrom R.et al.. Widespread plasticity in CTCF occupancy linked to DNA methylation. Genome Res. 2012; 22:1680–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lister R., Pelizzola M., Dowen R.H., Hawkins R.D., Hon G., Tonti-Filippini J., Nery J.R., Lee L., Ye Z., Ngo Q.M.et al.. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009; 462:315–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chen L., Chen K., Lavery L.A., Baker S.A., Shaw C.A., Li W., Zoghbi H.Y.. MeCP2 binds to non-CG methylated DNA as neurons mature, influencing transcription and the timing of onset for Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:5509–5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kinde B., Gabel H.W., Gilbert C.S., Griffith E.C., Greenberg M.E.. Reading the unique DNA methylation landscape of the brain: non-CpG methylation, hydroxymethylation, and MeCP2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:6800–6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kinde B., Wu D.Y., Greenberg M.E., Gabel H.W.. DNA methylation in the gene body influences MeCP2-mediated gene repression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016; 113:15114–15119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hong S., Wang D., Horton J.R., Zhang X., Speck S.H., Blumenthal R.M., Cheng X.. Methyl-dependent and spatial-specific DNA recognition by the orthologous transcription factors human AP-1 and Epstein–Barr virus Zta. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:2503–2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sperlazza M.J., Bilinovich S.M., Sinanan L.M., Javier F.R., Williams D.C. Jr. Structural basis of MeCP2 distribution on non-CpG methylated and hydroxymethylated DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2017; 429:1581–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lagger S., Connelly J.C., Schweikert G., Webb S., Selfridge J., Ramsahoye B.H., Yu M., He C., Sanguinetti G., Sowers L.C.et al.. MeCP2 recognizes cytosine methylated tri-nucleotide and di-nucleotide sequences to tune transcription in the mammalian brain. PLoS Genet. 2017; 13:e1006793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yang J., Horton J.R., Wang D., Ren R., Li J., Sun D., Huang Y., Zhang X., Blumenthal R.M., Cheng X.. Structural basis for effects of CpA modifications on C/EBPβ binding of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:1774–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hark A.T., Schoenherr C.J., Katz D.J., Ingram R.S., Levorse J.M., Tilghman S.M.. CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature. 2000; 405:486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bell A.C., Felsenfeld G.. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature. 2000; 405:482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Renda M., Baglivo I., Burgess-Beusse B., Esposito S., Fattorusso R., Felsenfeld G., Pedone P.V.. Critical DNA binding interactions of the insulator protein CTCF: a small number of zinc fingers mediate strong binding, and a single finger–DNA interaction controls binding at imprinted loci. J. Biol. Chem. 2007; 282:33336–33345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhao L., Sun M.A., Li Z., Bai X., Yu M., Wang M., Liang L., Shao X., Arnovitz S., Wang Q.et al.. The dynamics of DNA methylation fidelity during mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genome Res. 2014; 24:1296–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Xu C., Corces V.G.. Nascent DNA methylome mapping reveals inheritance of hemimethylation at CTCF/cohesin sites. Science. 2018; 359:1166–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Debaugny R.E., Skok J.A.. CTCF and CTCFL in cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2020; 61:44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. de Necochea-Campion R., Ghochikyan A., Josephs S.F., Zacharias S., Woods E., Karimi-Busheri F., Alexandrescu D.T., Chen C.S., Agadjanyan M.G., Carrier E.. Expression of the epigenetic factor BORIS (CTCFL) in the human genome. J. Transl. Med. 2011; 9:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Kandoth C., Schultz N., Cherniack A.D., Akbani R., Liu Y., Shen H., Robertson A.G., Pashtan I., Shen R.et al.. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013; 497:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zighelboim I., Mutch D.G., Knapp A., Ding L., Xie M., Cohn D.E., Goodfellow P.J.. High frequency strand slippage mutations in CTCF in MSI-positive endometrial cancers. Hum. Mutat. 2014; 35:63–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Walker C.J., Miranda M.A., O’Hern M.J., McElroy J.P., Coombes K.R., Bundschuh R., Cohn D.E., Mutch D.G., Goodfellow P.J.. Patterns of CTCF and ZFHX3 mutation and associated outcomes in endometrial cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2015; 107:djv249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]