Abstract

Eliminating malaria by 2030 is stated as goal three in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, malaria still remains a significant public health problem. This study aims to identify the factors determining malaria transmission in artisanal or small-scale miner (ASM) communities in three villages: Tanjung Agung, Tanjung Lalang, and Penyandingan, located in the Tanjung Enim District, Muara Enim, South Sumatra, Indonesia. Researchers conducted a cross-sectional study involving 92 participants from the study area. They used a logistic regression model to investigate the risk factors related to malaria occurrence. The multivariable analysis revealed that age (Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (APR) = 7.989 with 95% CI 1.724–37.002) and mosquito breeding (APR = 7.685 with 95% CI 1.502–39.309) were risk factors for malaria. On the other hand, higher education (APR = 0.104 with 95% CI 0.027–0.403), the use of mosquito repellent (APR = 0.138 with 95% CI 0.035–0.549), and the condition of house walls (APR = 0.145 with 95% CI 0.0414–0.511) were identified as protective factors. The current study highlights age and mosquito breeding sites as risk factors for malaria. Additionally, higher education, insect repellent use, and the condition of house walls are protective factors against malaria. Therefore, reducing risk factors and increasing protective measures through effective communication, information, and education are highly recommended to eliminate malaria in mining areas.

Subject terms: Ecology, Health care, Health occupations

Introduction

Malaria infects around 200 million people and causes 400,000 deaths annually in 90 countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) has targeted eliminating malaria in 35 countries by 20301. Eliminating malaria by 2030 is stated in the third goal of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, malaria is a significant public health problem in Indonesia2–5.

The main requirements for WHO certification include an Annual Parasite Incidence (API) of < 1 per 1000 population, a Positivity Rate (PR) of < 5% (positive malaria/blood preparations examined), and zero incidences of indigenous cases (malaria transmitted by local Anopheles mosquitoes carrying plasmodium) for three consecutive years6. Malaria elimination certification necessitates interrupting local transmission for all human malaria parasites7.

From 2009 to 2022, Muara Enim Regency witnessed a decline in the API. The API figures API’s were 0.91 in 2009, 0.79 in 2010, 0.54 in 2011, 0.62 in 2012, 0.47 in 2013, 0.22 in 2016, 0.1 in 2017, and 0.1 in 2018. Subsequently, API figures for the three most recent years were 0.01, 0.003, and 0.005 in 2020, 2021, and 2022 respectively8.

Eliminating malaria in Muara Enim, South Sumatra, is challenging due to the presence of many mosquito species, particularly some of the main malaria vectors, in aquatic habitats created by human activity, such as puddles and ditches9. In South Sumatra, Indonesia, Anopheles barbirostris, An. tesselatus, An. subpictus, An. nigerrimus, An. kochi, An. umbrosus, An. barbumbrosus, and An. maculatus, have been found, with An. sinensis and An. vagus confirmed as vectors in Muara Enim Regency and An. nigerrimus, An. umbrosus, An. letifer, and An maculatus in OKU Selatan Regency10,11. Additionally, artisanal coal mining plays a significant role in the mobility of miners, particularly those from malaria-endemic regions. These miners may carry the plasmodium parasite from their original regions (imported cases) or experience malaria relapses due to inadequate medication, posing a risk of malaria transmission at the mining site and among the surrounding population.

Studying malaria transmission in artisanal or small-scale miner (ASM) communities is crucial as they represent a high-risk group12. Small-scale mining areas are particularly susceptible to malaria transmission13. For example, miners in Aceh, Indonesia, are at risk of contracting malaria14. Other studies have also indicated that mining areas are more vulnerable to malaria15, with consistent evidence of malaria vectors thriving in mining areas, as seen in the highlands of West Kenya16. Malaria risk factors in mining areas include socio-economic and behavioural factors17, while changes in land use can impact the spread of malaria18,19.

On the other hand, although the ASM population is unique in malaria elimination, little is known about malaria in miners in Guyana20. So, malaria transmission in miners is interesting to investigate. Over five years, the Annual Parasite Incidence (API) at Tanjung Agung Health Center, Muara Enim, decreased in 2018 to 0.7, followed by 0.49 in 2019 and 0.05 in 2020. However, malaria is still spreading in the Tanjung Agung Sub-District, where most ASM areas still need to be studied. The API was taken from the malaria surveillance information system (SISMAL). Therefore, this study aims to bridge knowledge gaps by exploring the factors contributing to a higher likelihood of malaria in this region.

Results

Participant characteristics and demographics

Each of the following research variables was examined using univariate analysis: age, sex, length of service, years of service, level of education, the habit of using mosquito nets, the existence of mosquito breeding and resting places, knowledge, attitude, behaviour, and home condition factors. Furthermore, we summarise the basic factors that describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants. This was carried out to examine the association between these variables and miners’ malaria, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bivariate analyses of baseline socio-demographic characteristics of participants (n = 92).

| Variable | Malaria | PR; 95% CI (lb-ub) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Age | ||||||

| < 35 years old | 3 | 8.57 | 32 | 91.43 | 1.33 (0.95–1.85) | 0.163 |

| ≥ 35 years old | 11 | 19.30 | 46 | 80.70 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Woman | 4 | 13.33 | 26 | 86.67 | 1.07 (0.74–1.54) | |

| Man | 10 | 16.13 | 52 | 83.87 | 0.724 | |

| Years of service | ||||||

| < Five years | 1 | 2.70 | 36 | 97.30 | 1.72 (1.34–2.21) | 0.006 |

| ≥ Five years | 13 | 23.64 | 42 | 76.36 | ||

| Length of working | ||||||

| < Eight hours | 2 | 5.00 | 38 | 95.00 | 1.67 (1.23–2.26) | 0.017 |

| ≥ Eight hours | 12 | 23.08 | 40 | 76.92 | ||

| Education | ||||||

| High (senior high school) | 8 | 25.00 | 24 | 75.00 | 0.61 (0.33–1.15) | 0.054 |

| Low (primary school and junior high school) | 6 | 10.00 | 54 | 90.00 | ||

| Mosquito net | ||||||

| Yes | 11 | 22.45 | 38 | 77.55 | 0.41 (0.14–1.16) | 0.033 |

| Not | 3 | 6.98 | 40 | 93.02 | ||

| Using mosquito repellent | ||||||

| Yes | 11 | 25.58 | 32 | 74.42 | 0.36 (0.13–1.00) | 0.005 |

| Not | 3 | 6.12 | 46 | 93.88 | ||

| Out of the house | ||||||

| Not | 3 | 8.57 | 32 | 91.43 | 1.33 (0.95–1.85) | 0.163 |

| Yes | 11 | 19.30 | 46 | 80.70 | ||

| Self-medication | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 17.65 | 56 | 82.35 | 0.50 (0.13–1.91) | 0.278 |

| Not | 2 | 8.33 | 22 | 91.67 | ||

| Knowledge | ||||||

| High | 12 | 22.64 | 41 | 77.36 | 0.30 (0.08–1.10) | 0.028 |

| Low | 2 | 5.13 | 37 | 94.87 | ||

| Attitude | ||||||

| Good | 10 | 24.39 | 31 | 75.61 | 0.47 (0.20–1.10) | 0.021 |

| Not good | 4 | 7.84 | 47 | 92.16 | ||

| Practice | ||||||

| Good | 7 | 17.95 | 32 | 82.05 | 0.84 (0.48–1.47) | 0.535 |

| Not good | 7 | 13.21 | 46 | 86.79 | ||

| Mosquito breeding | ||||||

| No risk | 2 | 5.56 | 34 | 94.44 | 1.51 (1.13–2.02) | 0.036 |

| At risk | 12 | 21.43 | 44 | 78.57 | ||

| Resting place | ||||||

| No risk | 1 | 3.13 | 31 | 96.88 | 1.54 (1.22–1.94) | 0.014 |

| At risk | 13 | 21.67 | 47 | 78.33 | ||

| House wall condition | ||||||

| Eligible | 9 | 25.71 | 26 | 74.29 | 0.53 (0.26–1.10) | 0.021 |

| Not eligible | 5 | 8.77 | 52 | 91.23 | ||

| The ceiling of the house | ||||||

| Eligible | 8 | 16.00 | 42 | 84 | 0.92 (0.48–1.77) | 0.816 |

| Not eligible | 6 | 14.29 | 36 | 85.71 | ||

| House floor condition | ||||||

| Eligible | 8 | 25.00 | 24 | 75.00 | 0.61 (0.33–1.15) | 0.054 |

| Not eligible | 6 | 10.00 | 54 | 90.00 | ||

The 95% CI of percentage in bivariate analysis.

lb Lower 95% confidence boundary of cell percentage, ub Upper 95% confidence boundary of cell percentage.

In our study population, 78 (84.78%) respondents had no malaria or tested negative for malaria, whereas 14 (15.22%) were malaria positive. Among these, 38.04% were under the age of 35, while 61.96% were over the age of 35. The study included 62 men and 30 women. Respondents with less than five years of service accounted for 40.22%, while 59.78% had more than five years of service. Out of the fifty-two respondents, 56.52% worked less than eight hours, while 43.48% worked eight hours or more. Regarding education, 60 respondents were primary and junior high school graduates (65.22%), while 34 were senior high school graduates (34.78%). 53.26% of the respondents used mosquito nets, while 46.74% did not.

Additionally, 46.74% used mosquito coils, while 53.26% did not. 38.04% did not leave their houses, while 61.96% did. Among 68 respondents, 73.91% self-medicated, whereas 26.09% did not. Fifty-three respondents (57.61%) were knowledgeable, while 42.39% had insufficient knowledge. Furthermore, 44.57% had a good attitude, while 55.43% did not. 57.61% of the 92 respondents had poor practices, whereas 42.39% had good practices. The presence of breeding sites indicated that most miners were at risk (60.87%). 65.22% of respondents lived near at-risk resting sites. 61.96% of the respondents had ineligible house walls, while 38.04% had qualified ones. Moreover, 55.40% of the respondents met the eligibility criteria for their dwelling condition, while 44.60% did not. Finally, 65.22% of the respondents had non-eligible house walls, while 34.78% had eligible ones.

Based on the bivariate analysis table, several variables showed statistical significance with the prevalence of malaria. There is a statistically significant relationship between years of service (p = 0.006) and the length of time working with malaria status (p = 0.017). Furthermore, the chi-square test demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between mosquito net usage (p = 0.033) and the use of mosquito repellent (p = 0.005) with malaria. Moreover, the chi-square test revealed a statistically significant relationship between knowledge (p = 0.028) and attitude (p = 0.021) towards malaria. Additionally, mosquito breeding (p = 0.036) and resting place (p = 0.014) were found to be related to malaria. Finally, this study indicated that house wall condition (p = 0.021) and malaria showed statistical significance.

We selected the backward stepwise method for multivariable regression models, starting with a saturated model and gradually reducing variables to find the most appropriate model that explains the data. Variables were excluded during the backward stepwise process when their p values became insignificant. In the bivariate selection, a p value < 0.25 was used, and during the modelling phase, the variable with the highest p value was excluded until a model with a p value < 0.05 was obtained. Since these variables may influence one another, the variable with the most significance is considered the dominant variable on the outcome. Thus, the prevalence ratio is multivariable and referred to as adjusted. Furthermore, a multivariable analysis was performed to identify the dominant risk factors for malaria, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors associated with malaria prevalence in the low endemic area (n = 92).

| Research variables | PR crude (95% CI)a | P value | PR adjusted (95% CI)b | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| < 35 years old | ||||

| ≥ 35 years old | 1.33 (0.95–1.85) | 0.163 | 7.98 (1.72–37.00) | 0.008 |

| Education | ||||

| High (senior high school) | ||||

| Low (primary school and junior high school) | 0.61 (0.33–1.15) | 0.054 | 0.10 (0.02–0.40) | 0.001 |

| Using mosquito repellent | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| Not | 0.36 (0.13–1.00) | 0.005 | 0.13 (0.03–0.54) | 0.005 |

| Mosquito breeding | ||||

| No risk | ||||

| At risk | 1.51 (1.13–2.02) | 0.036 | 7.68 (1.50–39.30) | 0.014 |

| House wall condition | ||||

| Eligible | ||||

| Not eligible | 0.53 (0.26–1.10) | 0.021 | 0.14 (0.04–0.51) | 0.003 |

Ref. The reference category is represented in the contrast matrix as a row of one.

aCrude prevalence ratio (PR).

bAdjusted prevalence ratio (APR).

A multivariable analysis was carried out to determine the most influential factors. Finally, multivariable analysis showed that age was the main risk determinant factor, with a p value of 0.008. Higher education, insect repellent, and the house’s walls were protective factors, with PR < 1.

Principal findings

It is crucial to study malaria transmission in smallholder mining areas, as these areas are at high risk for malaria transmission. While many risk factors increase the possibility of malaria transmission in traditional mining, there was relatively little evidence in this study regarding malaria in miners, who are one of the populations targeted for malaria elimination. The major finding of this current research revealed that smallholder mining areas were risky areas for malaria transmission. Out of the 14 patients infected, 12 had plasmodium falciparum, and the remaining two had a plasmodium mix. (P. falciparum + P. vivax). Based on a Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) and microscopy results, P. falciparum was the most frequent parasite in the study area.

The current study identified the age of small-scale mining respondents and mosquito breeding sites as risk factors for malaria. Moreover, higher education, insect repellent use, and the condition of the house’s walls were found to be protective factors against malaria in the study area. In the multivariate analysis, participants over 35 years of age were 7.98 times more likely to have malaria than those under 35 years of age (adjusted PR: 7.98; 95% CI 1.72–37.00; p value: 0.008) after adjusting for education, mosquito repellent use, mosquito breeding, and the condition of the house walls. Additionally, the use of insect repellent was closely related to a reduced risk of malaria (adjusted PR: 0.13; 95% CI 0.03–0.54; p value 0.005).

Community mining activities, or ASM, have provided benefits because they are considered one of the poverty alleviation strategies21. ASM has played an essential role in the community’s economy and improved people’s livelihoods in various studies22–25. However, malaria transmission has been observed in ASM areas, posing health risks and environmental burdens due to land degradation26. Malaria transmission in the ASM area can increase malaria prevalence27. The spike in P. falciparum malaria observed in Guyana was most likely driven mainly by increased ASM activity28. The abundance of mosquito species was higher in ASM areas, leading to increased malaria prevalence29. Environmental degradation caused by mining and climate change has also led to the re-emergence of malaria in transmission hotspots30. Studies have shown a link between age and malaria transmission, where malaria is more likely as people get older31–33.

Regarding the breeding site issue, mining activities have produced artificial breeding grounds for vector mosquitoes34. For instance, Brazilian gold miners on the Amazon border dug pits and ditches, which were then abandoned, resulting in stagnant water that provided ideal habitat for mosquito breeding and malaria transmission35. Reducing breeding sites can decrease mosquito larval habitats and adult production36,37.

In this study, respondents lived either in the vicinity of their workplace or nearby, with some residing at their workplace for extended periods by arranging basic accommodations within the work area. Notably, certain miners lived in the forest. An. sinensis and An. vagus were confirmed as vectors in Muara Enim Regency, with sporozoites identified in their samples. Both species were active between 9 p.m. and 4 a.m. and preferred different biting locations. Mosquito-borne infections are more likely to occur at the workplace, especially for miners working without personal protective equipment, such as long-sleeved clothing or mosquito-repellent lotion.

Water-stored Anopheles mosquito eggs hatch into larvae and adult mosquitoes. Female mosquitoes need blood to feed their eggs. They search for “food” from dusk to dawn and can spread the plasmodium parasite. Mosquito numbers peak during and after the rainy season. Densely inhabited places increase malaria outbreaks. Malaria is more widespread at work than home since some illegal employees in Muara Enim, a mining area, work at night without protection. Working hours are from morning to evening, but some employees work until late at night. Additionally, some miners live or stay in the forest.

Regarding the socio-demography issue, another study in south-eastern Nigeria showed that higher education increases malaria protection knowledge and practices38. Other research shows that the spread of malaria can be reduced or eliminated using spatial repellents (SR)39. In this study, the condition of the house walls was identified as a protective factor against malaria in the study area, which aligns with the results of another study that examined housing and malaria40. In Uganda, good housing construction reduced malaria risk by limiting mosquito vectors’ entry41.

Explanatory variables

The current study showed that the infected study participants, who work in smallholder mining, were aged between 18 and 65 years, an average of 43 years, and exposed to malaria, with the majority (61.96%) aged 35 years. So this group needs to be a priority for preventing malaria. Furthermore, the current study showed that mosquito breeding sites indicated that most mining workers were at risk (60.87%), and so did the availability of mosquito resting areas (65.22%) associated with breeding sites. ASM activities resulted in significant environmental changes, including the creation of mosquito breeding sites, which allow disease vectors to multiply—associated with malaria transmission42. In another study in Moneragala, mining pits can increase the proliferation of malaria vectors43.

Similarly, mosquito breeding sites near homes are common in sub-Saharan Africa and cause malaria infection44. Another study found that land cover change is a significant cause of rising highland temperatures in Africa and the colonisation of malaria vectors. It also increases the sporogony development rate, survival of adult vectors, and risk of malaria in the highlands45. Efforts to reduce standing water and eliminate mosquito breeding sites can drastically reduce the Anopheles mosquito population46. Thus, it was recommended to eliminate mosquito breeding places in the mining area47. This current research demonstrates knowledge related to malaria transmission in ASM. In this respect, it is in line with several studies which show that public health education is essential for malaria control48,49. Previous studies showed that public health education is crucial for malaria control. This study showed that respondents’ overall knowledge score, attitude, and practice level towards malaria were relatively good. Thus, health education to raise the community’s awareness about the disease must address the gaps identified by this study50. Recognising social and behavioural risk factors and knowledge gaps in malaria-endemic regions is crucial to formulating practical disease prevention guidelines. Health professionals in malaria-endemic areas should be taught to provide better counselling to address cultural behaviours such as nighttime outdoor time, inappropriate bed net use, and irregular pesticide use during sleep to overcome local malaria knowledge gaps51. Effective disease-fighting tactics depend on population knowledge and behaviour. However, public authorities should continue to raise awareness about malaria prevention and treatment because more than half of the population self-medicates, which could perpetuate the disease and drug resistance52. Workers risk becoming infected if they do not use personal protective equipment, such as long-sleeved clothing or mosquito-repellent lotion while working in the forest. It is crucial to enhance respondents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) to prevent malaria transmission; National Malaria Control Programs should promote access to education and assist communities in adopting better malaria prevention and control practices.

In Yunnan Province, China, low education and risky behaviour lead to a high malaria incidence53. This study on ASM showed that respondents have a low level of education, and there is a need to increase specific knowledge about preventing malaria transmission. Improving accurate public knowledge and prompt treatment-seeking behaviour for malaria elimination for early diagnosis and treatment are essential54. Lack of access to and adherence to artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is an obstacle to the development of successful malaria treatment, which is also influenced by patient knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs55.

In addition, several studies have shown that using malaria repellent prevents malaria transmission56,57. Other studies highlight the need to strengthen plasmodium infection prevention and control strategies using personal mosquito repellents58. Furthermore, mosquito coils are popular in malaria-endemic countries59.

The current study showed that most miners had a poor level of education (65.22%), did not use mosquito coils (53.26%), and had a habit of leaving the house at night (61.96%), all of which are risk factors for malaria. It is in line with another study which revealed that outdoor miners were susceptible to mosquito bites and that modifying the house reduces malaria effectively60.

Home screening can reduce mosquito density61. Malaria is disappearing from areas that have been endemic for centuries, such as England’s south coast, because of better housing62. In Baringo District, the malaria vector prefers open roofs. Homes with thatched roofs have more malaria vectors than metal roofs63. So, future research should evaluate the protective effect of adding certain home features64. The current study showed that the state of the house’s walls (61.96%) and the ceiling (55.40%) were related to malaria transmission. It is similar to another study that showed a 47% lower malaria infection rate in improved (modern) homes compared to traditional ones64. In contrast, poor building construction and individual behaviour in Ghana are reasons for the high prevalence of malaria65.

Method

Study design and setting

The cross-sectional survey was conducted using a structured questionnaire from May to July 2022. All methods followed relevant guidelines or regulations66, including compliance with ethical requirements and specifically sampling without biological specimens. The interviews were conducted by obtaining informed consent; the respondents signed the consent form after understanding the aims and objectives of the research and voluntarily providing data to the researcher without coercion, and the identity of the respondents was made anonymous by the researcher to maintain confidentiality.

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Sriwijaya, with ethical approval No: 313/UN9.FKM/TU.KKE/2022. Participation in this study was voluntary in the field. All analyses were performed using participant identification codes to ensure maximum confidentiality.

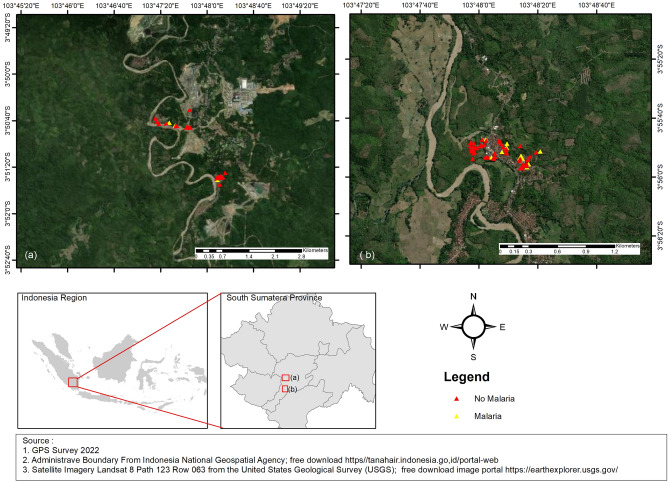

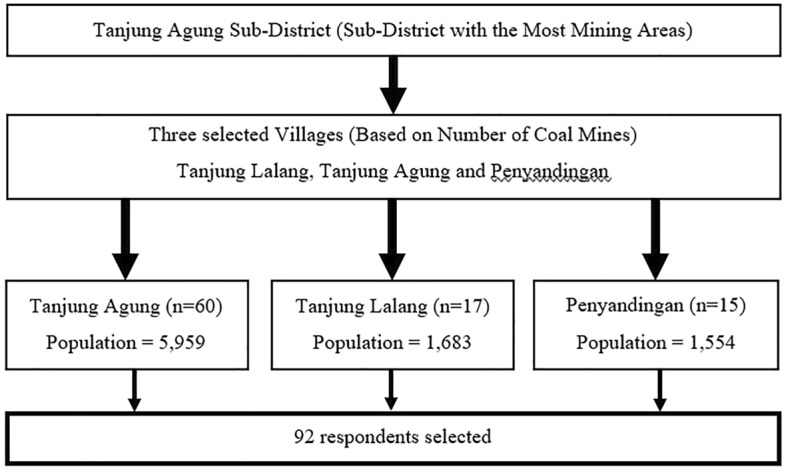

Using a purposive method, the investigator chose three villages, namely Tanjung Lalang, Tanjung Agung, and Penyandingan, in Tanjung Agung Sub-District, Muara Enim District. The study areas were selected based on information about the sites with the highest mining activities. The study areas are shown in Fig. 1

Figure 1.

Study area.

Sample size

This study uses a hypothesis test for two population proportions (two-sided test) with a level of significance of 95%, a type I error (α) of 5%, and a test power of 80%67.

It utilised P1 and P2 from previous studies for sample size determination and selected variables. Based on the literature review, the anticipated population proportion 1 (P1) for patients who do not use mosquito nets and have malaria is 0.79, while the anticipated population proportion 2 (P2) for patients who use mosquito nets and have malaria is 0.50. Therefore, the minimum sample size for each group in this study is 42 people. The results are multiplied by two because a two-proportion sample formula is used, resulting in an estimated total minimum sample size of 84 people. To account for potential dropouts and other factors, the sample size was increased by 10% to 92.4 and rounded to 92 respondents. Thus, the total sample calculation yielded 92 people. This recent study used a cross-sectional study design and revealed that 78 (84.78%) respondents had no malaria, whereas 14 (15.22%) had malaria.

Sampling technique

This study employed a purposive sampling technique to select clusters or villages. The village with the highest number of miners was chosen as the criteria for selection. The sampling method was done randomly in each village using the existing sampling frame in each chosen village. The number of samples taken in each village was determined proportionally, where the minimum sample obtained represents the population of artisanal small-scale mining (ASM) in these three villages. Due to social and environmental factors affecting malaria in small-scale mining areas, there were malaria-positive cases in this population, making the respondents at risk for malaria transmission. An illustration of the sampling technique is shown in Fig. 2

Figure 2.

Flowchart of a sampling frame of the study.

Using Muara Enim District’s Central Bureau of Statistics data, the investigator made a cluster fraction sample and grouped people in each village. Finally, the respondents were chosen using two-stage cluster sampling in the study area. The current study has improved Internal and external validity. The population’s livelihoods in the villages are heterogeneous; apart from labourers and employees, they also contribute to plantations, livestock, fisheries, farmers, and ASM. More mining locations exist in these three selected villages than in other areas.

Data collection

After random sampling, inclusion/exclusion criteria are based on the at-risk population. Thus, the eligibility criteria or inclusion criteria of this current study were that the respondent has lived in Muara Enim Regency for more than six months, is an illegal miner, can communicate properly and is ready to be a respondent. While the exclusion criteria are if the respondent does not finish the questionnaire and the sample respondents cannot speak effectively.

Epidemiological, socio-demographic characteristics, behavioural risk factors and observational environmental data were collected using a structured questionnaire. This questionnaire’s validity and reliability were tested on 30 respondents who live in Darmo village, which has mining activities. The respondents have the same characteristics as the sample study. After getting a valid and reliable questionnaire, the questionnaire was used for the respondents to collect information on risk factors of malaria occurrence in ASM in the study area. Eligible participants were informed about the general objectives. Oral consent was obtained before the interview, and information was recorded on paper case record forms. Investigators interviewed 92 miners who met the requirements to participate in the study. The interview, a structured questionnaire with open-ended and closed items, was conducted face-to-face.

Scope of variables

The data was processed using Stata software: on the dependent variable (malaria occurrence), respondents who did not experience malaria were coded 1, and respondents who had or were experiencing malaria were given code 2 in this study, conducted in 2022. Malaria infection (positive malaria) are patients with symptoms of malaria who have been declared positive based on rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) test and microscopy. In this study, the respondents who did not experience positive malaria were those who had negative malaria and were also healthy. In the questionnaire, for the dependent variable, the investigator asked respondents, “Had the respondents ever had blood drawn for malaria examination by a health worker?”. The answer was binary “Yes or Not”. If the answer was “Yes”, the next question was: had the respondents tested positive for malaria after examination by a health worker?

Likewise, the independent variable, code “small,” is given to describe the variable in the “bad/low” condition or the “at-risk” group. This category is grouped under code 1. At the same time, the code “large” is given to describe variables in “good/high” conditions or groups with the category “no risk” with code 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

All independent variables were coded as one risk category, with code 2 indicating no risk. The respondent’s age is recorded in years 35 (code 1) and 35 (code 2), then the years of service are divided using years five years and < 5 years and the division of working hours for respondents is calculated hourly 8 h and < 8 h in a day. The gender differences were divided into male and female and taken from the questionnaire. In this study, education is the highest level of education achieved by participants. Participants were considered highly educated after graduating high school and coded = 2. Participants who did not complete high school were classified as uneducated and assigned the code = 1.

Behavioural risk factors

From the questionnaire, the use of mosquito nets is categorised as follows: the respondent who does not use mosquito nets at night when sleeping is given a code of 1. If the respondent uses a mosquito net, it is coded as 2. The habit of using mosquito repellent is then divided; if not or only occasionally using mosquito repellent, code 1 was assigned, and code 2 was assigned to respondents who used mosquito repellent. The habit of going out at night and taking self-medication uses code 1 if yes, or sometimes code 2 if you never go out at night and take self-medication. The respondents’ knowledge is then divided into lack of knowledge and high knowledge and code 1 and code 2 for those with high knowledge. Meanwhile, attitude and practice are categorised with code 1 if they are not good and code 2 if they are good.

Environmental risk factors

Environmental factors are divided into two categories: outside and inside the home. In the outdoor environment, whether there is a breeding place for mosquitoes and a resting place for mosquitoes. The presence of a breeding and resting place is coded 1 if it is at risk or if the distance is 100 m from the respondent’s home location, and code 2 is not at risk if it is > 100 m. Regarding environmental elements, the condition of the house’s walls and the existence of the ceiling are significant. Additionally, the state of the house’s flooring Researchers assigned code 1 for a housing condition that does not match the requirements and is not an eligible house and code 2 for a housing condition that meets the requirements.

Factors associated with malaria occurrence using a structured questionnaire.

Information was primarily collected from respondents who were mining workers. The dependent data from a structured questionnaire included epidemiological data on malaria occurrence; At the same time, the independent variable included respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, including age, sex, years of service, length of work, and education level. In addition, behavioural risk factors included using a mosquito net, mosquito repellent, being out-of-the-house at night, self-medication, and KAP (knowledge, attitude and practice) also investigated. Furthermore, environmental risk factors included mosquito breeding, resting place, house wall condition, the existence of the house ceiling, and house floor condition. Another study found that bamboo/wood house walls, no insecticide, and a distance < 100 m from the mosquito breeding site were malaria risk factors68. The previous study showed environmental housing variables affect transmission. Mosquito breeding places near dwellings influence malaria transmission69. Household and neighbourhood-focused malaria interventions may assist high-burden nations. Targeted vector control methods like indoor residual pesticide spraying can help reduce malaria, address age-related differences in malaria outcomes, and ITN use70.

Anopheles larvae breed in former mining excavations, lagoons, swamps, buffalo puddles, ponds, ditches, rice and fields as breeding sites. A questionnaire and GPS measurements were used to determine whether each dwelling had a breeding site. Previously, Anopheles data were collected by the South Sumatra Provincial Health Office, Baturaja Litbangkes, and Muara Enim District Health Office.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics, chi-square and logistic regression analysis using STATA statistical software. Other data extracted were the availability of association between these variables and the occurrence of malaria in miners, provided in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Descriptive analysis

Individual characteristics of respondents include age, sex, years of service, length of work, and education level. Furthermore, behavioural risk factors include a mosquito net, mosquito repellent, out-of-the-house at night, and self-medication, then KAP (knowledge, attitude and practice) are the goals of descriptive analysis.

Bivariate analysis

The significance of the statistical relationship between each independent and dependent variable was analysed using the Chi-Square test by comparing the probability value (p value) with the alpha (α) = 0.05. If the p value is < 0.05, Ho (the null hypothesis) is rejected. It means there is a significant statistical relationship between the independent and dependent variables; if the p value > (0.05), Ho is accepted or failed to be rejected, meaning there is no significant statistical relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

Multivariable analysis

The malaria risk severity was evaluated using crude and adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR)†. If the prevalence ratio (PR) is more than one, the probability of developing malaria increases.

Limitations of research

In the study area, malaria transmission is influenced by various risk factors, although not all of them have been considered as research variables. This aspect presents an opportunity for further investigation. However, the current variables under study primarily pertain to social and environmental factors that impact malaria in small-scale mining areas. It is important to note that the study’s sample size is relatively small, which may introduce some bias in the results, particularly in assessing the proportion of malaria-positive cases. The sample size was determined using the sample formula for testing the two-proportion hypothesis, using data from previous studies regarding P1 and P2, as well as selected variables. This approach has improved the internal and external validity of the study, making it representative of artisanal mining in the three villages. In these villages, the residents’ livelihoods are diverse, involving activities such as smallholder plantations, livestock keeping, fisheries, farming, and mining. Interestingly, the study did not specify the respondents’ working hours, which could be associated with the risk of Anopheles mosquito bites. Despite this, it was found that respondents worked varying hours, with some working less than 8 h and others working 8 h or more. The majority of respondents (56.5%) opted for longer working hours to increase their daily income, as more hours of work resulted in higher wages. Hence, economic considerations drove many respondents to extend their working hours.The working hours typically span from morning until evening, although some individuals work until late evening. It is worth noting that An. sinensis tends to bite outdoors, while An. vagus prefers indoor biting. Both species are active from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m. These findings may have broader implications and can potentially be applied to other small-scale mining areas.

In summary, while additional risk factors may affect malaria transmission in the study area, the current research is primarily centered on the social and environmental factors impacting malaria in small-scale mining regions. Although small, the study’s sample size was carefully determined, enhancing the validity of the findings for artisanal mining in the three villages. Working hours play a role in malaria risk, with economic factors driving some respondents to work longer. Different mosquito species’ time preferences and biting behaviours shed light on the potential applicability of the study’s concept to other similar mining locations.

Informed consent

I undersign a certificate that I have the written consent of the identifiable person or their legal guardian to present the cases in this scientific paper.

Conclusions

Multivariable analysis revealed age and mosquito breeding as risk factors for malaria. A high level of education, the use of insect repellent, and the condition of the house’s walls are protective factors. Eliminating breeding sites in mining areas or avoiding direct contact between artisanal miners and vectors around the breeding sites can be facilitated by increasing knowledge, using insect repellent or protective clothing, and improving housing conditions as a protective factor. As an essential step towards eliminating malaria, generally, and at least in the research area, it is crucial to take preventive and promotional actions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tanjung Agung Sub-District management and clinic staff for their assistance in recruiting eligible subjects and providing data to ensure the success of this study. Professor Patricia Dale, a native English speaker, checked English. The Directorate General of Higher Education funded the research of this article, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, the Republic of Indonesia with the Fiscal Year 2022 following the Penelitian Dasar Kompetitif Nasional (PDKN) contract number: 142/E5/PG.02.00.PT/2022.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Artemisinin-based combination therapy

- An.

Anopheles

- API

Annual parasite incident

- APR

Adjusted prevalence ratio

- ASM

An artisanal miner or small-scale miner

- KAP

Knowledge, attitude, and practice

- SISMAL

Malaria surveillance information system

- p value

The probability value

- PR

Prevalence ratio

- RDT

Rapid diagnostic test

- SDG

Sustainable development goals

- SR

Spatial repellent

- WHO

World Health Organisation

Author contributions

H.H., R.F., I.A.L., and A.E. study validation and conceptualisation. W.C.R., R.A.F.L., H.M., F.E.M., collecting, investigation, and study validation. H.H., A.E., and S.H. wrote the main manuscript text. H.H. prepared figures. H.H., I.A.L., N., and A.E. edited and wrote the draft, and all authors contributed to interpreting the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lindblade KA, Li Xiao H, Tiffany A, Galappaththy G, Alonso P. Supporting countries to achieve their malaria elimination goals: The WHO E-2020 initiative. Malar. J. 2021;20:481. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03998-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasyim H, et al. Spatial modelling of malaria cases associated with environmental factors in South Sumatra, Indonesia. Malar. J. 2018;17:87. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2230-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasyim H, et al. Does livestock protect from malaria or facilitate malaria prevalence? A cross-sectional study in endemic rural areas of Indonesia. Malar. J. 2018;17:302. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2447-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasyim H, et al. Potential for a web-based management information system to improve malaria control: An exploratory study in the Lahat District, South Sumatra Province, Indonesia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0229838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasyim H, Dale P, Groneberg DA, Kuch U, Muller R. Social determinants of malaria in an endemic area of Indonesia. Malar. J. 2019;18:134. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2760-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemenkes RI. Petunjuk teknis penilaian eliminasi malaria Kabupaten/Kota Dan Provinsi. (Direktorat Pencegahan dan Pengendalian Penyakit Tular Vektor dan Zoonotik, Direktorat Jenderal Pencegahan Dan Pengendalian Penyakit, Kemenkes RI, Jakarta, 2023).

- 7.Nasir SM, Amarasekara S, Wickremasinghe R, Fernando D, Udagama P. Prevention of re-establishment of malaria: Historical perspective and future prospects. Malar. J. 2020;19:452. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03527-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Muara Enim. Profil kesehatan (2022).

- 9.Conde M, et al. Larval habitat characteristics of the main malaria vectors in the most endemic regions of Colombia: Potential implications for larval control. Malar. J. 2015;14:476. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-1002-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budiyanto A, Ambarita LP, Salim M. Konfirmasi Anopheles sinensis dan Anopheles vagus sebagai vektor malaria di Kabupaten Muara Enim Provinsi Sumatera Selatan. Aspirator J. Vector-Borne Dis. 2017;9:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yahya Y, Haryanto D, Pahlevi RI, Budiyanto A. keanekaragaman jenis nyamuk Anopheles di sembilan kabupaten (tahap pre-eliminasi malaria) di Provinsi Sumatera Selatan. Vektora J. Vektor dan Reserv Penyakit. 2020;12:41–52. doi: 10.22435/vk.v12i1.2621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dao F, et al. Burden of malaria in children under five and caregivers' health-seeking behaviour for malaria-related symptoms in artisanal mining communities in Ghana. Parasit. Vectors. 2021;14:418. doi: 10.1186/s13071-021-04919-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilson, G., Hilson, A. & Adu-Darko, E. Chinese participation in Ghana's informal gold mining economy: Drivers, implications and clarifications. J. Rural Studies34, 292–303. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.03.001 (2014).

- 14.Ekawati LL, et al. Defining malaria risks among forest workers in Aceh, Indonesia: A formative assessment. Malar. J. 2020;19:441. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03511-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Argaw MD, et al. Access to malaria prevention and control interventions among seasonal migrant workers: A multi-region formative assessment in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0246251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukabane K, et al. Bed net use and malaria treatment-seeking behavior in artisanal gold mining and sugarcane growing areas of Western Kenya highlands. Sci. African. 2022;16:e01140. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2022.e01140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soe HZ, Thi A, Aye NN. Socio-economic and behavioural determinants of malaria among the migrants in gold mining, rubber and oil palm plantation areas in Myanmar. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2017;6:142. doi: 10.1186/s40249-017-0355-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fornace KM, et al. Environmental risk factors and exposure to the zoonotic malaria parasite Plasmodium knowlesi across northern Sabah, Malaysia: A population-based cross-sectional survey. Lancet Planet. Health. 2019;3:e179–e186. doi: 10.1016/s2542-5196(19)30045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naik DG. Plasmodium knowlesi-mediated zoonotic malaria: A challenge for elimination. Trop. Parasitol. 2020;10:3–6. doi: 10.4103/tp.TP_17_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olapeju B, et al. Malaria prevention and care seeking among gold miners in Guyana. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0244454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith NM, Ali S, Bofinger C, Collins N. Human health and safety in artisanal and small-scale mining: An integrated approach to risk mitigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;129:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilson GM. The future of small-scale mining: Environmental and socio-economic perspectives. Futures. 2002;34:863–872. doi: 10.1016/S0016-3287(02)00044-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calderon A, Harris JD, Kirsch PA. Health interventions used by major resource companies operating in Colombia. Resour. Policy. 2016;47:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2015.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mencho BB. Assessing the effects of gold mining on environment: A case study of Shekiso district, Guji zone, Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2022;8:e11882. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bansah KJ, Dumakor-Dupey NK, Kansake BA, Assan E, Bekui P. Socio-economic and environmental assessment of informal artisanal and small-scale mining in Ghana. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;202:465–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yelpaala K, Ali SH. Multiple scales of diamond mining in Akwatia, Ghana: Addressing environmental and human development impact. Resour. Policy. 2005;30:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2005.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quarm JA, Anning AK, Fei-Baffoe B, Siaw VF, Amuah EEY. Perception of the environmental, socio-economic and health impacts of artisanal gold mining in the Amansie West District, Ghana. Environ. Chall. 2022;9:100653. doi: 10.1016/j.envc.2022.100653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Salazar PM, Cox H, Imhoff H, Alexandre JS, Buckee CO. The association between gold mining and malaria in Guyana: A statistical inference and time-series analysis. Lancet Planet. Health. 2021;5:e731–e738. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00203-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hierlmeier VR, Gurten S, Freier KP, Schlick-Steiner BC, Steiner FM. Persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic chemicals in insects: Current state of research and where to from here? Sci. Total Environ. 2022;825:153830. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fletcher IK, et al. Synergies between environmental degradation and climate variation on malaria re-emergence in southern Venezuela: a spatiotemporal modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health. 2022;6:e739–e748. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00192-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn CE, Le Mare A, Makungu C. Malaria risk behaviours, socio-cultural practices and rural livelihoods in southern Tanzania: Implications for bednet usage. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;72:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dondorp AM, et al. The relationship between age and the manifestations of and mortality associated with severe malaria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;47:151–157. doi: 10.1086/589287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohan I, et al. Socio-economic and household determinants of malaria in adults aged 45 and above: Analysis of longitudinal ageing survey in India, 2017–2018. Malar. J. 2021;20:306. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03840-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murta FL, et al. Perceptions about malaria among Brazilian gold miners in an Amazonian border area: Perspectives for malaria elimination strategies. Malar. J. 2021;20:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03820-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. Environmental and occupational health hazards associated with artisanal and small-scale gold mining. (World Health Organization, 2016).

- 36.Thomas S, et al. Socio-demographic and household attributes may not necessarily influence malaria: Evidence from a cross sectional study of households in an urban slum setting of Chennai, Inida. Malar. J. 2018;17:4. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2150-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fillinger U, et al. Identifying the most productive breeding sites for malaria mosquitoes in the Gambia. Malar. J. 2009;8:62. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dike N, et al. Influence of education and knowledge on perceptions and practices to control malaria in Southeast Nigeria. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006;63:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlwood JD, et al. Spatial repellents and malaria transmission in an endemic area of Cambodia with high mosquito net usage. Malariaworld J. 2017;8:11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sikalima J, et al. House structure is associated with malaria among febrile patients in a high-transmission region of Zambia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;104:2131–2138. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wanzirah H, et al. Mind the gap: house structure and the risk of malaria in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0117396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones RT, et al. The impact of industrial activities on vector-borne disease transmission. Acta Trop. 2018;188:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hewavitharane, M., Ranawaka, G., Saparamadu, M., Premaratne, R. & Jayasooriya, H. T. R. Proceeding of the 15th Open University Research Sessions. (2017). (The Open University of Sri Lanka).

- 44.Imbahale SS, Fillinger U, Githeko A, Mukabana WR, Takken W. An exploratory survey of malaria prevalence and people’s knowledge, attitudes and practices of mosquito larval source management for malaria control in western Kenya. Acta Trop. 2010;115:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kweka EJ, Kimaro EE, Munga S. Effect of deforestation and land use changes on mosquito productivity and development in Western Kenya Highlands: Implication for malaria risk. Front. Public Health. 2016;4:238. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mattah PAD, et al. Diversity in breeding sites and distribution of Anopheles mosquitoes in selected urban areas of Southern Ghana. Parasit. Vectors. 2017;10:1–25. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1941-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takarinda KP, et al. Factors associated with a malaria outbreak at Tongogara refugee camp in Chipinge district, Zimbabwe, 2021: A case–control study. Malar. J. 2022;21:94. doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04106-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang F, Wang XD, Jiang L, Qiu HY. Evaluation of the effectiveness of community health education for the prevention and control of retransmission of imported malaria in Zhangjiagang City. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2021;33:308–310. doi: 10.16250/j.32.1374.2020140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dlamini SV, et al. Knowledge of human social and behavioral factors essential for the success of community malaria control intervention programs: The case of Lomahasha in Swaziland. J. Microbiol., Immunol. Infect. = Wei mian yu gan ran za zhi. 2017;50:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flatie BT, Munshea A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards malaria among people attending mekaneeyesus primary hospital, south Gondar, northwestern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J. Parasitol. Res. 2021;2021:5580715. doi: 10.1155/2021/5580715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bashar K, et al. Socio-demographic factors influencing knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) regarding malaria in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1084. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Djoufounna J, et al. Population knowledge, attitudes and practices towards malaria prevention in the locality of Makenene, centre-cameroon. Malar. J. 2022;21:234. doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04253-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li C, et al. Identification and analysis of vulnerable populations for malaria based on K-prototypes clustering. Environ. Res. 2019;176:108568. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hasabo EA, et al. Treatment-seeking behaviour, awareness and preventive practice toward malaria in Abu Ushar, Gezira state, Sudan: a household survey experience from a rural area. Malar. J. 2022;21:182. doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04207-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banek K, et al. Factors associated with access and adherence to artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) for children under five: a secondary analysis of a national survey in Sierra Leone. Malar. J. 2021;20:56. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03590-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karunamoorthi K, Hailu T. Insect repellent plants traditional usage practices in the Ethiopian malaria epidemic-prone setting: an ethnobotanical survey. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mapossa AB, Focke WW, Tewo RK, Androsch R, Kruger T. Mosquito-repellent controlled-release formulations for fighting infectious diseases. Malar. J. 2021;20:165. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03681-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chin AZ, et al. Risk factor of plasmodium knowlesi infection in Sabah Borneo Malaysia, 2020: A population-based case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0257104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hogarh JN, Antwi-Agyei P, Obiri-Danso K. Application of mosquito repellent coils and associated self-reported health issues in Ghana. Malar. J. 2016;15:61. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1126-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Furnival-Adams J, Olanga EA, Napier M, Garner P. House modifications for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021;1:Cd013398. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013398.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fox T, Furnival-Adams J, Chaplin M, Napier M, Olanga EA. House modifications for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022;10:Cd013398. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013398.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jumbam DT, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices assessment of malaria interventions in rural Zambia. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:216. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8235-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ondiba IM, et al. Malaria vector abundance is associated with house structures in Baringo County, Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0198970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tusting LS, et al. The evidence for improving housing to reduce malaria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar. J. 2015;14:209. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0724-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bempah S, Curtis A, Awandare G, Ajayakumar J. Appreciating the complexity of localised malaria risk in Ghana: Spatial data challenges and solutions. Health Place. 2020;64:102382. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. International ethical guidelines for health-related research involving humans. (WHO Press, 2017).

- 67.Lwanga, S. K., Lemeshow, S. & World Health, O. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 1991).

- 68.Rejeki DSS, Solikhah S, Wijayanti SPM. Risk factors analysis of malaria transmission at cross-boundaries area in menoreh Hills, Java, Indonesia. Iran J. Public Health. 2021;50:1816–1824. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v50i9.7054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hasyim, H. et al. in Proceedings of the 3rd Sriwijaya International Conference on Environmental Issues, SRI COENV 2022 (ed France) Hermione Froehlicher (Bordeaux University, Nambooze Joweria (Kyambogo University, Uganda), Frederick Adzitey (University of Development Studies, Ghana), Siti Hanggita Rachmawati (Universitas Sriwijaya, Indonesia), Nasib Marbun (Media Digital Publikasi Indonesia, Indonesia) and Robbi Rahim (Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Manajemen Sukma, Indonesia) (EAI, Palembang, South Sumatera, Indonesia, 2022). https://eudl.eu/doi/10.4108/eai.5-10-2022.2328358.

- 70.Carrel M, et al. Individual, household and neighborhood risk factors for malaria in the democratic republic of the congo support new approaches to programmatic intervention. Health Place. 2021;70:102581. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.