Abstract

Introduction

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a worldwide occurring common bacterial agent for community-acquired pneumonia especially in children and young people with high contagiousness. Extrapulmonary complications such as cardiopulmonary, gastrointestinal, neurological and mucocutaneous manifestations including Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) may occur especially in adults. MIRM is an important differential diagnosis of Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS). Both clinically present similar as mucocutaneous erosive eruptions but have different etiologies.

Case presentation

We present an atypical case of a 36-year-old female with overlapping clinical features of MIRM and SJS. The patient presented to our allergy-outpatient clinic after recovering from mucocutaneous erosive eruptions and receiving an allergy-passport upon discharge for all drugs administered during the course of treatment including a subsequent ban of all beta-lactam antibiotics and NSAIDs for the future resulting in a desperate patient and treating physicians. A positive result of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the sputum culture upon discharge was unnoticed. An allergological work-up with skin testing and drug provocation testing with the culprit drugs and safe alternatives was performed which resulted negative. Therefore, a new allergy passport was issued with drug alternatives that the patient may use in the future. A diagnosis of MIRM was subsequently made.

Discussion

The present case report depicts the diagnostic algorithm in an atypical case with overlapping clinical features of a MIRM and SJS.

Conclusion

Patients with atypical mucocutaneous eruptions of possible allergological etiology should receive a careful allergological work-up in an experienced tertiary referral center to reduce the number of inadequate allergy passport distribution.

Keywords: Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Cutaneous adverse drug reaction (CADR), Beta-lactam antibiotics, NSAID, Extensive allergy passport, Allergological work-up

Introduction

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, affecting only human beings, is a common bacterial pathogen for pulmonary infections with possible extrapulmonary complications and long-lasting sequelae especially in adults [1]. Extrapulmonary complications include cardiopulmonary, gastrointestinal, neurological and mucocutaneous manifestations and have been associated with macrolide resistance [2]. Mucocutaneous manifestations such as Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) both clinically present similar, however, MIRM usually affects young adults and shows predominantly mucosal involvement with sparse cutaneous involvement [3]. Here, we present an atypical case of extensive MIRM in a middle-aged female with suspected drug-induced SJS as a differential diagnosis.

Case report

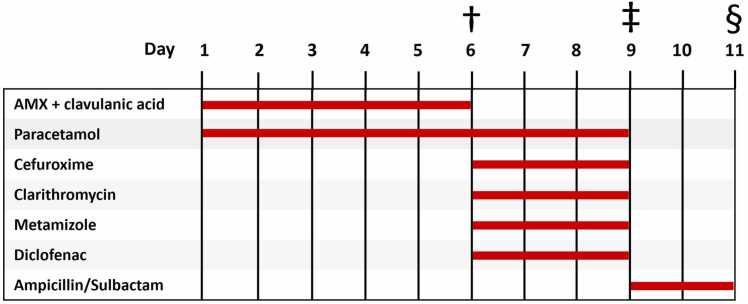

In September 2010 a 36-year-old woman presented to our allergy outpatient clinic after suffering from a suspected drug-induced SJS nine months ago. The patient was hospitalized due to suspected community-acquired pneumonia with conjunctivitis, pyrexia (39 °C), cough and other flu-like symptoms. A chest x-ray revealed inhomogeneous, small-spotted, partially confluent shadowing of the right lung lower lobe. The initial treatment prescribed by her general practitioner consisted of oral amoxicillin (AMX) with clavulanic acid, paracetamol and acetylcysteine. Due to a lack of improvement, the patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital where antibiotic treatment was changed to intravenous cefuroxime and oral clarithromycin. In addition, metamizole, diclofenac and paracetamol were administered as needed. On day 9, the patient’s overall condition deteriorated and consequently, antibiotic treatment was changed to Ampicillin/Sulbactam. Fig. 1 shows the administering period of each drug.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of possible culprit drugs administered. †Hospitalization with pneumonia and initial conjunctivitis. ‡Worsening of the general condition. §Transfer to the Department of Dermatology.

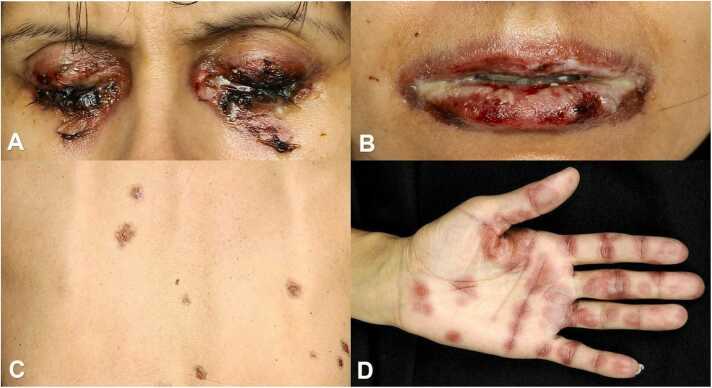

The patient developed painful stomatitis, cockade-like lesions on the palms and back with further exacerbation with a total body surface area involvement of about 15 % (Fig. 2 A–D).

Fig. 2.

A–D: Worsening of the initial condition on day 9 with concomitant a) eye involvement, b) stomatitis, c) lesions on the back and d) cockade-like lesions on the palms.

As the mucocutaneous manifestations and the general condition further worsened, an on-call dermatology consultant suspected a drug-induced SJS. All ongoing treatments were immediately stopped and high-dose intravenous corticosteroids and supportive treatment were initiated. Subsequent microbiological testing revealed Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MP) in the sputum culture 10 days later. No serological testing was performed. The patient was effectively treated with doxycycline in conjunction with topical oral and ocular supportive care. On day 22 the patient could be discharged with ongoing oral steroid treatment to be slowly tapered and received an allergy-passport for all drugs administered, all NSAIDs as well as all beta-lactam antibiotics due to possible cross-reactivity. As a result of this generous ban of commonly used antibiotics and analgesics the patient and her treating GP were very concerned about which medication to use if needed. Therefore, a thorough allergological work-up was initiated at our clinic to identify the possible culprit drug as well as safe alternatives (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of medications tested and used concentrations, drugs were dissolved when required as recommended by the manufacturer and used “as is” for PT and diluted with 0.9 % sodium chloride as shown in the Table for IDT. *PPL, MDM, AMX by Diater, S. A., Madrid, Spain.

| Drugs tested | Intradermal test | Patch test | Patch test in loco |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culprit drugs | |||

| PPL* | 0.04 mg/ml | 0.04 mg/ml | |

| MDM* | 0.5 mg/ml | 0.5 mg/ml | |

| Penicillin G | 1000 IU | 200.000 IU | |

| AMX* | 20 mg/ml | 20 mg/ml | |

| AMX + Clavulanic acid | 0.495/0.05 mg/ml | 49.5/5 mg/ml | 49.5/5 mg/ml |

| Cefuroxime | 1 mg/ml | 100 mg/ml | 100 mg/ml |

| Clarithromycin | 0.005 mg/ml | 50 mg/ml | |

| Paracetamol | 0.2 mg/ml | 0.2 mg/ml | 0.2 mg/ml |

| Metamizole | 0.1 mg/ml | 500 mg/ml | 500 mg/ml |

| Diclofenac | 0.25 mg/ml | 25 mg/ml | 25 mg/ml |

| Alternative drugs | |||

| Cefazoline | 1 mg/ml | 100 mg/ml | |

| Ceftriaxone | 1 mg/ml | 100 mg/ml | |

| Cefepime | 2 mg/ml | 200 mg/ml | |

| Lornoxicam | 0.4 mg/ml | 4 mg/ml | |

Abbreviations used: SJS = Steven-Johnson Syndrome, GP = general practitioner, AMX = amoxicillin, D = day, DTH = drug hypersensitivity, IDT = intradermal test, PT = patch test, PPL = Benzylpenicilloyl polylysine, MDM = Minor Determinant Mixture, MP = Mycoplasma pneumoniae, MIRM = Mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis, NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, DPT = drug provocation testing.

Intradermal tests (IDT) were performed with diluted intravenous preparations on the left inner forearm with readings at day 1. Patch tests (PT) were performed on the dorsal part of her upper left arm as well as on previously SJS involved skin only with culprit drugs in terms of local provocation tests (= in loco) followed by two readings at day 1 and day 2. For PT drug solutions were used “as is” soaked on filter paper placed in large Finn Chambers® on Scanpor tape (SmartPractice, Phoenix, Arizona) and were fixed with Fixomull® stretch (BSN medical GmbH; Hamburg; Germany).

Skin tests resulted negative for all tested substances. Therefore, cautious drug provocation testing (DPT) under strict supervision in an inpatient setting with incremental dosages of lornoxicam 2/4/8 mg as an alternative NSAID and penicillin V 500/1.0 Mio/1.5 Mio IU as a beta-lactam antibiotic representative was commenced and well tolerated. Hence, the previous ban of all beta-lactam antibiotics could be lifted and an alternative NSAID was found.

Discussion

The most common triggers of SJS are drugs such as allopurinol, sulfonamides, oxicam NSAIDs and anticonvulsants in genetically predisposed patients [4]. Treatment of SJS should always be patient-oriented and includes the use of glucocorticoids and immunoglobins, supportive care and immediate discontinuation of possible culprit drugs [5]. Avoidance of accidental exposure to the culprit drug in SJS for the future is essential [6]. However, upon discharge, patients should not be given such a generous allergy-passport banning all drugs involved without any suggestions for alternatives. Allergological work-up for drug-hypersensitivity to narrow down possible triggers of SJS, can be performed securely, even if PT sensitivity is less than 30 % highly depending on the drug class [7], [8], [9]. The role of IDT with late readings in SJS is still unclear, however may be considered in some patients after a careful risk-benefit analysis [10]. Given the extensive ban of commonly used analgesics and beta-lactam with negative IDT and PT results after re-evaluation in mutual agreement with our patient, cautious DPT was carried out as an inpatient setting with lornoxicam as an alternative orally and intravenously applicable analgesic as well as penicillin V as the primary beta-lactam antibiotic that resulted negative. As the patient denied further DPT we could not demonstrate the tolerability of AMX and directly rule it out as a causative drug. However, the fact that the patient was treated with Ampicillin from day 9 on without further deterioration of her skin condition and the well-known high cross-reactivity potential between AMX and Ampicillin make AMX also unlikely to be the reason for a putative SJS. Therefore, we first suggested Mycoplasma pneumoniae as another most common reason for SJS.

As this case happened in 2010 and the entity of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis was first distinguished from SJS in 2015 [3]. The treating dermatologist suspected in the patient a drug-induced SJS. MIRM and SJS may clinically present similar, however MIRM shows more sparse cutaneous involvement and usually affects younger (mean age of 12 ± 9 years), predominantly (up to 66 %) male patients [3]. Although, our patient was female and middle-aged at disease manifestation we, in retrospect, revised her diagnosis to MIRM as most drugs were ruled out as culprits for SJS.

In conclusion, i) the present case underlines the difficulties of the clinical differentiation between SJS and MIRM, ii) and highlights the importance of allergological work-up even in putative SJS with multiple culprit drug involvement not only for the differentiation between those two diagnoses but also for the treatment of the patient at least with lornoxicam as a pain reliever and beta-lactam antibiotics without concern in the future if needed, iii) in addition, when diagnosing pneumonia, sputum PCR, wherever available, should be performed as the first diagnostic method to promptly identify the causative agent for a fast and correct diagnosis.

Ethical approval

No ethics approval required according to the Case Reporting (CARE) Guideline.

Funding source

None.

Consent

Not applicable as photographs do not jeopardize the patients´ personal information.

ICMJE Statement

E.M. wrote the main manuscript, prepared figures and the table. T.K. made the concept, performed the allergological work-up, organized the pictures and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jiang Z., Li S., Zhu C., Zhou R., Leung P.H.M. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections: pathogenesis and vaccine development. Pathogens. 2021;10(2) doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narita M. Classification of extrapulmonary manifestations due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection on the basis of possible pathogenesis. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:23. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canavan T.N., Mathes E.F., Frieden I., Shinkai K. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(2):239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodiuk-Gad R.P., Chung W.H., Valeyrie-Allanore L., Shear N.H. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16(6):475–493. doi: 10.1007/s40257-015-0158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider J.A., Cohen P.R. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a concise review with a comprehensive summary of therapeutic interventions emphasizing supportive measures. Adv Ther. 2017;34(6):1235–1244. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0530-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creamer D., Walsh S.A., Dziewulski P., Exton L.S., Lee H.Y., Dart J.K.G., et al. U.K. guidelines for the management of Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults 2016. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(6):1194–1227. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbaud A., Collet E., Milpied B., Assier H., Staumont D., Avenel-Audran M., et al. A multicentre study to determine the value and safety of drug patch tests for the three main classes of severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(3):555–562. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolkenstein P., Chosidow O., Fléchet M.L., Robbiola O., Paul M., Dumé L., et al. Patch testing in severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Contact Dermat. 1996;35(4):234–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assier H., Valeyrie-Allanore L., Gener G., Verlinde Carvalh M., Chosidow O., Wolkenstein P. Patch testing in non-immediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions: value of extemporaneous patch tests. Contact Dermat. 2017;77(5):297–302. doi: 10.1111/cod.12842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brockow K., Romano A., Blanca M., Ring J., Pichler W., Demoly P. General considerations for skin test procedures in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2002;57(1):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]