Abstract

Evidence supporting the relief of suffering and improved end-of-life care provided by hospice is in contrast with recent media reports of cases of poor-quality care driven by profit-motivated hospices. This commentary presents a brief history of hospice and potential solutions to address the current challenges affecting access to high-quality hospice care.

Keywords: hospice, for-profit healthcare

The inaugural hospice was founded by Dame Cicely Saunders in 1967 in England, with the aim of alleviating the suffering of people dying from cancer or other life-limiting illnesses by addressing their pain and other symptoms, as well as their social, psychological, and spiritual needs. When done well, hospice benefits people with cancer and their families. Hospice care reduces pain for patients through expert symptom-directed care, thus improving their quality of life.1 It also has downstream benefits for family caregivers of patients enrolled, with lower risk of complicated grief and higher likelihood of reporting that that their loved ones received excellent end-of-life care.2,3 Accordingly, hospice care is considered a “gold standard” for end-of-life care for patients with cancer.

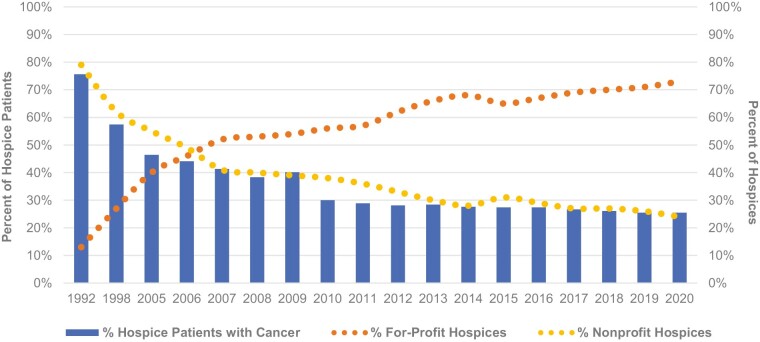

As the hospice movement expanded to the US, it was led by volunteers and largely supported by donations. The goal of these early hospice champions was to provide comfort care, primarily to those with cancer, and enable them to die at home with the support of hospice, rather than in the hospital. In 1982, the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act authorized Medicare to cover hospice care under the Medicare Hospice Benefit. This provided hospices with a fixed per diem reimbursement per patient enrolled in hospice. In 1989, the Omnibus Reconciliation Act increased this per diem reimbursement rate by 20%. Subsequently, the number of for-profit hospices surged from roughly 10% in the early 1990s to more than 70% by 2020. The transition of hospice from a grass roots movement to a for-profit industry has fueled debate regarding the impact of this transition on the quality of hospice care delivered to patients and families.

Evidence supporting the relief of suffering and improved end-of-life care provided by hospice is in contrast with recent media reports of cases of poor-quality care driven by profit-motivated hospices.4 Concerns have arisen regarding both access to hospice care for patients with cancer and the quality of that care. These concerns often involve profit-driven practices to place limits on supportive and palliative care options considered “gray areas” for hospice coverage.5,6 For example, expensive oral targeted agents that can be easily administered in the home setting and that may palliate symptoms are now available for many patients with cancer. Moreover, people with blood cancers may continue to benefit from blood transfusions to address symptoms of fatigue, dyspnea, and bleeding near the end of life.7 Yet, many for-profit hospice organizations do not provide these services for their patients who may desire them.8

The fact that for-profit hospices have come to dominate the hospice sector and that their practices and patient populations align with the financial incentives in our healthcare system is clear.9 There is a substantial evidence base identifying ownership differences in both quality and access to hospice. In comparison to nonprofit hospices, for-profit hospice agencies provide a narrower range of clinical services, have higher frequency of complaint allegations, have higher rates of hospital and intensive care unit admissions, and are more likely to discharge patients prior to death.10–15 Although differences in quality often garner the most attention, the more incremental changes in access to hospice are also concerning.

People with cancer are not the population targeted by for-profit hospices. This has been consistently documented.11,12 There are at least 3 key reasons for this. First, the range of treatment and palliative options within oncology (eg, oral agents, transfusions, palliative radiation) has expanded, thus increasing the cost of caring for those with cancer who are eligible for hospice. This range of available therapies serves to increase the cost to hospices of caring for those with cancer. Accordingly, for-profit hospices are more likely to adopt restrictive admission practices that discourage patients with cancer from enrolling to limit the costs associated with the additional care options for this population.8,16,17

Second, people with cancer have increasingly shorter hospice enrollment periods.18-20 Fewer days with hospice tends to be less profitable for hospices because the high-intensity, high-cost first and last days of hospice care are offset by fewer lower-cost days in between. For-profit hospices may thus recruit patients with dementia or other diagnoses that are more likely to guarantee longer lengths of hospice enrollment.11 Although the 2016 Medicare Hospice Benefit payment reforms to provide increased reimbursement rates for the first 60 days of hospice enrollment were intended to reduce the incentive for long hospice enrollment periods, they appear to have had little to no impact on hospice duration.21

Finally, people with cancer do not tend to live in nursing homes or assisted living facilities.22 Residential settings in which people live in close proximity to one another and in which there may be on-site supportive services decreases the costs of care for hospices. Therefore, for-profit hospices may be more likely to cultivate referral networks within nursing homes and assisted living facilities and less likely to build relationships with cancer centers.12 Growth of for-profit hospice penetration in these residential settings has been substantial.

Given that for-profit hospices continue to expand across the US through growth in size, chain ownership, and even private equity involvement should we be concerned regarding future access to hospice for persons with cancer? What do the data say?

Longitudinal data demonstrate a striking correlation between the increasing proportion of for-profit hospices in the US and the decreasing proportion of hospice patients with cancer (Authors' estimates based on data from the General Accounting Office, Medicare claims, and National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Facts and Figures report.). Although causality cannot be gleaned from these data and the number of persons with cancer accessing hospice has increased over time, it is reasonable based on the aforementioned “unprofitable” characteristics of the cancer population and the financially motivated practices of for-profit hospices to be concerned about hospice access for those with cancer.

So what can we do to ensure that persons with cancer can both access hospice and receive high-quality care when enrolled? Several strategies have been proposed.

One idea gaining traction is implementing policies that allow carve-out payments for palliative treatments that are more costly than routine hospice care. Such policies have the potential to reduce restrictive hospice admission practices for people with cancer. A recent innovative example of this is the S.2566 bill: “Improving Access to Transfusion Care for Hospice Patients Act of 2021,”23 which calls for testing a model of care for people with hematologic malignancies, in which blood transfusions during hospice enrollment are paid for separately from the hospice all-inclusive per diem payment. Only a minority of hospices enroll patients with blood cancers who want to receive palliative transfusions, with for-profit hospices less likely to enroll this population.12 Policies such as the S.2566 bill that allow separate payment for costly treatments that are palliative near the end of life may promote greater access to hospice care for people with cancer.

Another policy strategy is to reimburse hospices different amounts based on patient diagnosis instead of the current system that does not consider patient diagnosis in the per diem reimbursement rate. In a diagnosis-adjusted system, reimbursement rates for patients with cancer would be greater than the typical fixed-rate given their higher care needs.

Finally, increasing access to hospice for persons with cancer must be matched by a strong commitment to high-quality care. Although the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services launched a public website reporting quality measures for hospices in 2017, for-profit hospices, particularly those in competitive markets, have been significantly less likely to participate.24 Policies that promote mandatory and timely provision of hospice quality reporting, along with consequences for poor performance on quality measures, are needed. In addition, oncologists should make patients and families aware of this public data to help guide decision making when selecting hospice agencies.

It is essential that the quest for profit does not overpower the mission at the core of the hospice movement. Dame Cicely Saunders originally envisioned hospice as a model of comfort-focused care specifically for people dying from advanced cancer and to support their families. The field of hospice has since grown exponentially to care for people suffering from various types of life-limiting illnesses. Although some people dying of cancer may not be deemed “profitable,” we need hospices, regardless of ownership or tax status, to continue to provide access to compassionate physical, emotional, and spiritual care for people with cancer near the end of life.

Contributor Information

Oreofe O Odejide, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Melissa D Aldridge, Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA; James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Bronx, NY, USA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673. 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):4457-4464. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863. JCO.2009.26.3863 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kumar P, Wright AA, Hatfield LA, Temel JS, Keating NL.. Family perspectives on hospice care experiences of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(4):432-439. 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.9257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kofman A. How hospice became a for-profit hustle. The New Yorker. 2022. New York: Conde Nast. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright AA, Katz IT.. Letting go of the rope--aggressive treatment, hospice care, and open access. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):324-327. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp078074. 357/4/324 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Odejide OO. A policy prescription for hospice care. JAMA. 2016;315(3):257-258. 10.1001/jama.2015.18424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henckel C, Revette A, Huntington SF, et al. Perspectives regarding hospice services and transfusion access: focus groups with blood cancer patients and bereaved caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(6):1195-1203.e4. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.12.373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson KS, Payne R, Kuchibhatla MN, Tulsky JA.. Are hospice admission practices associated with hospice enrollment for older African Americans and Whites?. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(4):697-705. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Chapter 11: Hospice services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy . 2022:48. March, 2022. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://doi.org/https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Mar22_MedPAC_ReportToCongress_Ch11_SEC.pdf.

- 10. Carlson MD, Gallo WT, Bradley EH.. Ownership status and patterns of care in hospice: results from the National Home and Hospice Care Survey. Med Care. 2004;42(5):432-438. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000124246.86156.54. 00005650-200405000-00006 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, McCarthy EP.. Association of hospice agency profit status with patient diagnosis, location of care, and length of stay. JAMA. 2011;305(5):472-479. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.70. 305/5/472 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aldridge MD, Schlesinger M, Barry CL, et al. National hospice survey results: for-profit status, community engagement, and service. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):500-506. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3. 1832198 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cherlin EJ, Carlson MD, Herrin J, et al. Interdisciplinary staffing patterns: do for-profit and nonprofit hospices differ?. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(4):389-394. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aldridge MD, Epstein AJ, Brody AA, et al. The impact of reported hospice preferred practices on hospital utilization at the end of life. Med Care. 2016;54(7):657-663. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stevenson D, Sinclair N.. Complaints about hospice care in the United States, 2005-2015. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(11):1580-1587. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jarosek SL, Virnig BA, Feldman R.. Palliative radiotherapy in Medicare-certified freestanding hospices. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(5):780-787. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aldridge Carlson MD, Barry CL, Cherlin EJ, McCorkle R, Bradley EH.. Hospices’ enrollment policies may contribute to underuse of hospice care in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(12):2690-2698. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0286. 31/12/2690 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang R, Zeidan AM, Halene S, et al. Health care use by older adults with acute myeloid leukemia at the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3417-3424. 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.7149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, LaCasce AS, Abel GA.. Hospice use among patients with lymphoma: impact of disease aggressiveness and curability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(1):1-8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wright AA, Hatfield LA, Earle CC, Keating NL.. End-of-life care for older patients with ovarian cancer is intensive despite high rates of hospice use. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3534-3539. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5383. JCO.2014.55.5383 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gianattasio KZ, Power MC, Lupu D, Prather C, Moghtaderi A.. Medicare hospice policy changes and beneficiaries’ rate of live discharge and length-of-stay. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;65(3):162-172. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aldridge MD, Ornstein KA, McKendrick K, et al. Trends in residential setting and hospice use at the end of life for medicare decedents. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):1060-1064. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. S.2566-Improving Access to Transfusion Care for Hospice Patients Act of 2021, S.2566, Congress (2021). 07/29/2021. https://doi.org/https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2566/text

- 24. Hsu SH, Hung P, Wang SY.. Factors associated with hospices’ nonparticipation in medicare’s hospice compare public reporting program. Med Care. 2019;57(1):28-35. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]