Abstract

Research in youth psychopathy has focused heavily on the affective features (i.e., callous-unemotional [CU] traits) given robust links to severe and chronic forms of externalizing behaviors. Recently, there have been calls to expand the scope of work in this area to examine the importance of other interpersonal (i.e., antagonism) and behavioral (i.e., disinhibition) features of psychopathy. In the present study, we apply an under-utilized statistical approach (i.e., dominance analysis) to assess the relative importance of CU traits, antagonism, and disinhibition in the prediction of externalizing behaviors in youth, cross-sectionally and at 9-month follow-up. Using a multi-informant (youth- and parent-report), multi-method (questionnaire, ecological momentary assessment [EMA]) preregistered approach in a diverse sample of clinically referred youth (Mage = 12.60 years, SD = .95 years, 47% female; 61% racial/ethnic minority), we found youth- and parent-reported psychopathy features accounted for a significant proportion of variance in externalizing behavior cross-sectionally and longitudinally. However, results provided limited support for our preregistered hypotheses. While antagonism and disinhibition had larger general dominance weights relative to CU traits for both youth- and parent-report, most differences were non-significant. Thus, the interpersonal, affective, and behavioral psychopathy features could not be distinguished from one another in terms of their importance in the prediction of externalizing behavior, assessed cross-sectionally or longitudinally. Taken together, the results highlight promising avenues for future research on the relative importance of youth psychopathy features.

Keywords: Callous-unemotional traits, Antagonism, Disinhibition, Dominance analysis, EMA, Longitudinal

In an attempt to identify those youth most at-risk for severe and protracted trajectories of externalizing behavior, researchers have utilized downward extensions of adult psychopathy (Frick, 2009; Lynam et al., 2008). While psychopathy includes multiple interpersonal (e.g., antagonism, grandiosity), affective (e.g., callous-unemotional (CU) traits), and behavioral (e.g., disinhibition, impulsive behavior) features, this downward extension has focused primarily on CU traits (e.g., Cardinale & Marsh, 2020; Frick et al., 2014a). There have been a substantial number of studies showing the importance of CU traits in predicting maladaptive outcomes, mostly notably externalizing behaviors (Frick et al., 2014b; Kahn et al., 2013). Recently, however, researchers have called for a broadening in the scope of investigations to include interpersonal (i.e., antagonism) and behavioral (i.e., disinhibition) facets of psychopathy as these features may be as or more important than CU traits in explaining maladaptive behavior (Salekin et al., 2018). Using a multi-informant (youth- and parent-report), multi-method (questionnaire, ecological momentary assessment [EMA]) approach, the present study examines the relative importance of CU traits and other features of youth psychopathy (e.g., antagonism, disinhibition) as predictors of externalizing behaviors, assessed cross-sectionally, and at 9-month follow-up. We use dominance analysis, a useful and under-utilized method designed to answer questions about the relative importance of psychopathy features in predicting externalizing behavior in youth.

Downward Extension of Adult Psychopathy: Assessment and Utility of CU Traits in Youth

While there continues to be ongoing debate about which features are most central to conceptualizations of psychopathy (Miller & Lynam, 2015), there is a general consensus that psychopathy includes core interpersonal (e.g., antagonism, grandiosity), affective (e.g., callousness, lack of guilt/remorse) and behavioral (e.g., disinhibition, impulsive behavior) features (Hare & Neumann, 2008). Downward extensions of adult psychopathy to youth have focused primarily on the affective features (e.g., CU traits; Frick, 2009) as hallmark indicators of youth psychopathy, as these characteristics were historically not well-represented within the diagnostic criteria of externalizing disorders (Dadds et al., 2005). In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), CU traits are now assessed using the Limited Prosocial Emotion specifier, further underscoring their clinical utility and highlighting the continued need to understand their incremental clinical value (Colins et al., 2021).

Indeed, many studies demonstrate that youth with higher levels of CU traits are at greater risk for a variety of externalizing behaviors (see Frick et al., 2014b for a comprehensive review). Recent meta-analytic work by Cardinale and Marsh (2020), highlighted robust associations between externalizing behaviors and CU traits, specifically callousness and uncaring features, as measured by Inventory for Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICU; Kimonis et al., 2008), arguably the most widely used measure of CU traits.1 Overall, callousness (e.g., lack of concern for the feelings of others) and uncaring (e.g., lack of concern about relationships or performance) features demonstrated moderate positive relations with externalizing behavior (k range = 44–50; r range = 0.29-0.35). Moreover, effects for externalizing outcomes were found to vary by informant, with parent- and teacher-reported callousness and uncaring features showing the largest effect sizes (rs of 0.46 and 0.41, respectively; k = 13) compared to youth-report of the same features (rs of 0.32 and 0.25, respectively; k = 41). Though there is little debate that CU traits in youth are relevant to understanding the development and persistence of externalizing behaviors, the extent to which other interpersonal (i.e., antagonism) or behavioral (e.g., disinhibition) features of psychopathy may enhance our understanding of risk for externalizing behaviors in youth, and whether their utility may vary by informant, has received considerably less attention.

Antagonism and Disinhibition in Youth Psychopathy

In dimensional models of personality, maladaptive traits are conceptualized as extreme variants of general personality traits, with features of psychopathy primarily reflecting traits within the domains of antagonism and disinhibition (Lynam & Miller, 2015; Salekin, 2017). Antagonism (vs. agreeableness) describes interpersonal features that lead to increased conflict with others, including a willingness to exploit and deceive others while disregarding their needs and feelings. Disinhibition (vs. conscientiousness) captures a behavioral disposition towards immediate gratification, resulting in impulsive behaviors or decisions that fail to consider past experiences or future consequences (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Indeed, in the alternative model of personality disorders (AMPD) outlined in Section III of the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), the specific facets of antagonism (grandiosity, attention seeking, deceitfulness, manipulativeness, hostility, callousness) and disinhibition (e.g., impulsivity, irresponsibility, risk taking, and (lack of) perfectionism) largely coincide with the same features that comprise the interpersonal and behavioral features of psychopathy (Hawes et al., 2014; Lynam et al., 2005). The facets of antagonism and disinhibition also show notable similarities to psychopathic features as assessed by the recently developed Proposed Specifiers for Conduct Disorder scale (PSCD; Salekin & Hare, 2016) that have been termed callous-unemotional, grandiose-manipulative, and daring-impulsive (Salekin, 2017).2 Importantly, meta-analytic evidence has consistently shown that the features that comprise antagonism and disinhibition are robust correlates of externalizing behavior, with features of antagonism tending to show larger effect sizes than features of disinhibition (Hyatt et al., 2019; Vize et al., 2018, 2019a, b).

Despite evidence that antagonism and disinhibition are associated with increased risk for externalizing behaviors, researchers have only just begun to explore the relative importance of these features in distinguishing youth who are at high-risk for externalizing behaviors. In a series of empirical articles, CU traits were compared to other interpersonal (e.g., antagonism) and behavioral (i.e., disinhibition) features of psychopathy in predicting a range of externalizing behavior in youth (Andershed et al., 2018; Bergstrøm & Farrington, 2018; Colins et al., 2018; Fanti et al., 2018; Frogner et al., 2018). Results suggested that high levels of interpersonal, affective, and behavioral features of psychopathy in youth explained significant variance in externalizing behavior. For example, Andershed and colleagues (2018) focused on a community sample of middle-schoolers (mean age = 12.12 years) and found that youth with high levels of self-reported interpersonal, affective, and behavioral psychopathic were most likely to engage in externalizing behavior at 1–3 year follow-up relative to five other groups of youth with different combinations of externalizing and psychopathic features.3 Colins and colleagues (2018) applied the same subgrouping approach using parent-reported features of youth aged 7 to 12 years old, and replicated these findings. Together, this work underscores the potential benefits of broadening investigations to include an examination of interpersonal and behavioral psychopathic features alongside CU traits in the prediction of externalizing behavior in youth. However, important questions remain regarding the relative importance of these psychopathic features in youth (i.e., after controlling for their overlap, do interpersonal, affective, or behavioral features of psychopathy more strongly predict externalizing behaviors in youth).

Limitations of Current Statistical Approaches to Examining Relative Importance

Hypotheses regarding the relative importance of psychopathic features are typically tested by examining the incremental variance accounted for by CU traits relative to other interpersonal and behavioral features of psychopathy using subgroups, created by categorizing or dichotomizing continuous assessments of these features (Andershed et al., 2018). While these strategies have undoubtedly advanced our understanding of risk for externalizing behaviors in youth, there are notable limitations. First, research consistently shows that interpersonal, affective, and behavioral features of psychopathy are best understood dimensionally, and this is true in adult (Edens et al., 2006; Guay et al., 2007) and youth samples (Edens et al., 2011; Kliem et al., 2021; Murrie et al., 2007; Walters, 2014). Second, these subgrouping approaches may obscure heterogeneity among individuals in the same group, a well-known issue for many classification approaches for mental health problems (Feczko et al., 2019). Third, research shows that dichotomizing continuous variables is statistically ill-advised and leads to an attenuation of power, loss of information, and biased estimates (Cohen, 1983; Dawson & Weiss, 2012; MacCallum et al., 2002; Royston et al., 2006).4 Fortunately, there are alternative methods that avoid the conceptual and statistical issues of dichotomizing and artificially grouping continuous variables, while also addressing questions of relative importance surrounding features of psychopathy in youth.

Alternative Statistical Approaches to Characterizing Relative Importance

A widely used approach for questions of relative importance is dominance analysis (Azen & Budescu, 2003) which offers notable advantages beyond common incremental validity analyses in traditional regression models (e.g., examining ΔR2 in hierarchical regression models). It is specifically designed to answer questions of relative importance when working with continuous, correlated predictors (e.g., interpersonal, affective, and behavioral features of psychopathy) using regression models (see Grömping, 2015, for a review), while avoiding the shortcomings of other approaches (e.g., comparing standardized regression coefficients; Bring, 1994). In dominance analysis, one variable is considered more “important” than another if it accounts for a significantly larger amount of variance in an outcome across regression submodels (i.e., when the predictor is by itself in the regression model, and in all possible combinations with another predictors).5 Overall or “general dominance” is determined by taking the average amount of variance accounted for by a predictor across all regression submodels. If the average amount of variance accounted for by one predictor is greater than the average variance accounted for by another, the predictor is said to show “general dominance” over the other predictor(s). These methods have been utilized in the adult literature to compare the relative importance of CU traits, antagonism, and disinhibition as predictors of externalizing behaviors (e.g., LeBreton et al., 2013). However, despite the potential benefits of dominance analysis in better understanding the relative importance of CU traits versus other psychopathic features, we are aware of no studies that have used these methods to examine their relative importance in the prediction of externalizing behaviors in youth.

Current Study

The current study aims to extend past research by examining the relative importance psychopathy features in youth (i.e., CU traits, antagonism, and disinhibition) using dominance analysis, a statistical procedure well-suited for evaluating associations between these features and externalizing behaviors. We also expand on past research by taking a multi-informant, multi-method approach, allowing us to examine the relative importance of these features across informant (youth- and parent report), and type of assessment (questionnaire, EMA). Analyses were conducted cross-sectionally and longitudinally (i.e., 9-month follow-up) using a racially and socioeconomically diverse sample of clinically referred youth during the transition to adolescence. The study has two primary aims:

Aim 1

Examine the relative importance of youth- and parent-reported CU traits (uncaring, callousness), antagonism, and disinhibition as predictors of youth- and parent-reported externalizing behaviors assessed via questionnaire and in daily life.

Hypothesis1

We expect that CU traits, specifically callousness, and antagonism will be relatively more important than uncaring traits and disinhibition across informants and assessments, as reflected by significantly larger general dominance weights.

Aim 2

Examine the relative importance youth- and parent-reported CU traits (uncaring, callousness), antagonism, and disinhibition as predictors of youth- and parent-reported externalizing behaviors assessed via questionnaire and EMA at 9-month follow-up.

Hypothesis2

We expect a similar pattern of results in longitudinal analyses. Specifically, we hypothesize that CU traits, specifically callousness, and antagonism will be relatively more important than uncaring traits and disinhibition across informants and assessments, as reflected by significantly larger general dominance weights.

Method

This study was preregistered, and the preregistration can be found at the following link: https://osf.io/zguf2/.6 All deviations from the preregistration are noted in the manuscript. Data and code to reproduce all results detailed below can be found on the OSF page for the project: https://osf.io/2c3nm.

Sample

Participants for the current study were drawn from a larger sample of 162 youth ages 10–14 years (Mage = 12.03 years, SD = 0.92 years; 47% female; 60% racial/ethnic minority)7 and their caregivers (Mage = 39.84; SD = 7.25; 94% female; 48% racial/ethnic minority8; 88% biological mothers, hereafter referred to as “parent”). Participants were recruited from pediatric primary care clinics within a large, Mid-Atlantic, urban, academic hospital-based setting, and from ambulatory psychiatric treatment clinics in the same geographic region. All youth were receiving psychiatric treatment for any mood or behavior problem and were oversampled for emotional reactivity based on the Affective Instability subscale from the Personality Assessment Inventory-Adolescent version (M = 13.05, SD = 2.90; scores > 11 indicating clinical significance; Morey, 2007). This recruitment strategy was designed to capture a heterogenous sample of clinically referred youth, characterized by a range of psychopathology (see Table S1). Any youth with an IQ estimate < 70 (n = 5), not currently in treatment for a mood or behavior problem (n = 4), with an organic neurological medical condition (n = 1), diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder or in a current manic or psychotic episode were excluded. All parents had legal custody and shared/primary physical custody (≥ 50% of the time). Parents, on average, reported three children (M = 3.24, SD = 1.68) in their home and 49% reported living with their romantic partners. While 64% of households had at least one employed parent, 19% reported an annual household income between $20,000—$39,000, 31% reported annual income < $20,000, and 55% of the sample was receiving public assistance.

Procedure

Participants included in our primary analyses comprised a subset of the larger sample described above. Specifically, the sample for the current study included 140 youth (Mage = 12.60 years, SD = 0.95 years, 47% female; 61% racial/ethnic minority) and their caregivers (Mage = 39.84; SD = 7.25; 94% female; 48% racial/ethnic minority) who provided data on youth psychopathy features at baseline and reported on externalizing behaviors at baseline and 9-month follow-up.9 At each assessment, youth and their parent completed questionnaires. Following these assessments, youth and their parent completed a 4-day ecological momentary assessment (EMA) protocol, which consisted of 10 time-based prompts administered over the course of a long weekend on separate lab-provided smartphones. The current study focuses on questionnaire and EMA data collected at baseline and 9-month follow-up.

Measures

CU Traits

CU traits were assessed at baseline using the youth- and parent-report versions of the Inventory of Callous and Unemotional Traits (ICU; Kimonis et al., 2008). We focused on the 11-item callousness subscale (e.g., “I do not care who I hurt to get what I want) and 8-item uncaring subscale (e.g., “I easily admit to being wrong”, reverse-scored), given their well-documented associations with externalizing behaviors (Cardinale & Marsh, 2020). All items were rated on a 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“definitely true”) scale and summed to create total subscale scores. Each subscale demonstrated acceptable reliability across informants at baseline (youth-report: callousness: α = 0.73, uncaring: α = 0.83; parent-report: callousness: α = 0.83, uncaring: α = 0.84). These internal consistencies are consistent with previous estimates in similar samples (Cardinale & Marsh, 2020).

Antagonism and Disinhibition

Antagonism and disinhibition were examined as indictors of the interpersonal and behavioral features of psychopathy, respectively. These features were assessed at baseline using the youth- and parent-report versions of Brief Version of the Personality Inventory for the DSM-5 (PID-5-BF; Krueger et al., 2013). The current study focuses on the 5-item antagonism subscale (e.g., “I often have to deal with people who are less important than me;” “I use people to get what I want”) and the 5-item disinhibition subscale (e.g., “People would describe me as reckless;” “I feel like I act totally on impulse”). To ensure there was no overlap in item content with subscales assessing CU traits, one item (“It’s no big deal if I hurt other peoples’ feelings”) was removed from the antagonism subscale, in line with our preregistered plan. Also detailed in our preregistered plan, one additional item from the negative affectivity subscale indexing hostility (“I get irritated easily by all sorts of things”) was added to the antagonism subscale as hostility has been shown to be strongly related to antagonism (Watters et al., 2019), and is cross-listed within antagonism in the Alternative Model of Personality Disorders in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These changes to the PID-5-BF-antagonism scales allowed for key interpersonal features of psychopathy to be compared to CU traits as assessed by the ICU. While we refer to the scale using the antagonism label throughout the manuscript, it is important to note that callousness-related content, a central feature of antagonism (Sleep et al., 2021), has been excluded for the purposes of our study goals.

All items were rated on a 0 (“very false or often false”) to 3 (“very true or often true”) scale and summed to create a total score. Each subscale demonstrated acceptable reliability across informants (youth-report: antagonism: α = 0.71, disinhibition: α = 0.77; parent-report antagonism: α = 0.77, disinhibition: α = 0.86).10 These internal consistencies are consistent with previous estimates in similar samples (Anderson et al., 2018; Fossati et al., 2017).

Externalizing Behavior

Questionnaire

Externalizing behavior was assessed via youth- and parent-report at baseline and 9-month follow-up using Achenbach’s Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991) and the parent-reported Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1999). The YSR and CBCL are comprised of eight syndrome scales, grouped into two higher-order factors: internalizing and externalizing. We focused on the 33-item externalizing behavior scale, which includes rule-breaking behavior (e.g., “breaks rules”, “steals”) and aggressive behavior (e.g., “gets into fights”, “threatens others”). All items were rated on a 3-point scale from 0 (“not true”) to 2 (“very or often true”) and summed to create a total score for externalizing behavior, which demonstrated acceptable reliability across informants at baseline (youth-report: α = 0.92; parent-report: α = 0.91) and 9-month follow-up (youth-report: α = 0.91; parent-report: α = 0.92).

EMA

Externalizing behavior was also assessed via youth- and parent-report at baseline and 9-month follow-up during the EMA protocol.11 At each prompt, youth and parents were asked “Since you received the last prompt, did you (or “did your child”)… 1)“yell or argue with anyone,” or 2) “break or damage any property.” However, these items showed a low ratio of endorsement during the EMA protocol.12 Thus, we also examined EMA items that were administered only to youth and at the end of each day: “Think about the time you felt the worst or the most negative. When you were feeling the worst, did you let your feelings out by…” 1) yelling at someone, or 2) hitting, slamming, or punching someone or something.13 The latter analyses utilizing end-of-day EMA responses were not preregistered.

Analysis Plan

Preliminary analyses examined descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between all primary study variables using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Dominance analyses were conducted using the ‘yhat’ (Nimon & Oswald, 2013) and ‘partR2’ (Stoffel et al., 2021) packages in R (Version 4.1.1; R Core Team, 2021). These analyses focused on within-informant associations between youth- and parent-reported psychopathic features (i.e., CU traits [callousness, uncaring], antagonism, and disinhibition) and externalizing behavior assessed via questionnaire and EMA at baseline and 9-month follow-up. Externalizing behavior assessed via questionnaire was continuous and thus, examined using linear regression models. Externalizing behavior assessed via EMA was assessed with dichotomous items (0 = not present; 1 = present) over the course of the EMA protocol and thus, examined using multilevel logistic regression.

For each model,14 we present the overall R2 along with general dominance (GD) weights for each predictor (i.e., CU traits [callousness, uncaring], antagonism, and disinhibition) and their rescaled percentages. GD weights represent the averaged proportion of variance in the outcome (R2) attributable to that predictor. For example, in a simple case with two predictors (X1 and X2), the general dominance weight for X1 is given by taking the average of 1) the variance accounted for in the outcome when X1 is the only predictor in the model (i.e., the squared zero-order correlation: ), and 2) the variance accounted for by X1 when X2 is included in the regression model (i.e., the squared semi-partial correlation: ). GD weights can also be rescaled as percentages, which represent the percentage of variance accounted for in the outcome that is attributable to a given predictor (i.e., GD weight for a predictor/R2 of the model when all predictors are included).

Predictors with significantly larger GD weights or scaled percentages can be interpreted as accounting for more variance in the outcome compared to a predictor with a smaller general dominance weight and relatively more important. To directly compare differences between GD weights, bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals were estimated for outcomes assessed at baseline and at the 9-month follow-up. The ‘partR2’ package was used to examine patterns of general dominance for logistic multilevel models but does not have direct support for computing bootstrapped confidence intervals around general dominance weights nor differences in general dominance weights. However, odds ratios and respective 95% confidence intervals for all multilevel logistic models (used for dichotomous EMA outcomes) are available using the code associated with this study (https://osf.io/zguf2/).

Secondary Analyses

Consistent with our preregistered analytical plan, we conducted secondary analyses. First, we examined the influence of the hostility item included within antagonism. Specifically, all primary analyses were re-run excluding the hostility item from youth and parent-reported antagonism to examine whether excluding this item affected patterns of general dominance. Next, we examined the influence of affective instability15 given that this clinically referred sample was recruited based on the presence of these features. All primary analyses were re-run including affective instability to assess its impact it had on patterns of general dominance. Finally, we conducted additional analyses (not preregistered) to examine 1) the influence of demographic covariates (youth age, sex, minoritized status, and family receipt of public assistance) on results; 2) whether patterns of general dominance differed when predicting youth- and parent-reported aggression16; and 3) whether patterns of general dominance differed for cross-informant externalizing behavior (e.g., youth-reported psychopathy features predicting parent-reported externalizing behavior).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 provides descriptive information for all primary variables at baseline and 9-month follow-up, and Table S2 provides associations between demographic variables (youth age, sex, minoritized status, and family receipt of public assistance) and primary study variables. Parents reported higher levels of callousness (M = 8.31; SD = 5.78) compared to youth (M = 6.44; SD = 4.71), t(283.27) = 3.04, p < 0.01., and higher levels of uncaring (M = 12.89; SD = 5.26) relative to youth (M = 8.48; SD = 5.09), t(291.99) = 7.31, p < 0.01. Parents also reported higher antagonism (M = 5.88; SD = 4.19) compared to youth (M = 3.57; SD = 3.07), t(291.99) = 7.31, p < 0.01, but levels of disinhibition were similar when reported by parents (M = 4.85; SD = 3.57) or youth (M = 4.50; SD = 3.70). Lastly, parents reported more externalizing behavior at baseline (M = 15.16; SD = 10.30) compared to youth (M = 11.80; SD = 9.49), t(285.15) = 2.89, p < 0.01. While parents also reported slightly more externalizing behavior at follow-up (M = 13.01; SD = 10.00) compared to youth (M = 10.81; SD = 9.20), this difference was not significant, t(258.09) = 1.85, p = 0.07.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Primary Study Variables

| Mean (SD) | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Predictors (Baseline) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Youth-Report | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Callousness | 6.44 (4.71) | 0–27 | – | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Uncaring | 8.48 (5.09) | 0–23 | .22 * | – | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Antagonism | 3.57 (3.07) | 0–13 | .27 * | .28 * | – | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Disinhibition | 4.50 (3.70) | 0–15 | .21 * | .07 | .60 * | – | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent-Report | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Callousness | 8.31 (5.78) | 0–27 | .17 * | .09 | .23 * | .33 * | – | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Uncaring | 12.89 (5.26) | 0–24 | .22 * | .36 * | .14 | .16 | .57 * | – | ||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Antagonism | 5.88 (4.19) | 0–14 | .04 | .00 | .30 * | .31 * | .55 * | .42 * | – | |||||||||||||||||

| 8. Disinhibition | 4.85 (3.57) | 0–15 | .09 | .10 | .32 * | .45 * | .60 * | .49 * | .56 * | – | ||||||||||||||||

| Externalizing Behavior (Baseline) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Youth-Report | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Externalizing Behavior (Questionnaire) | 11.80 (9.49) | 0–53 | .35 * | .30 * | .59 * | .58 * | .29 * | .29 * | .27 * | .42 * | – | |||||||||||||||

| EMA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Since the last prompt… | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. Yell/Argue | 1.40 (1.77) | 0–8 | .01 | .01 | .22 * | .18 * | .06 | .01 | .10 | .15 | .16 | – | ||||||||||||||

| 11. Break/damage property | 0.16 (0.70) | 0–5 | .02 | .02 | .12 | .07 | .08 | .11 | .04 | .20 * | .10 | .34 * | – | |||||||||||||

| Feeling your worst or most upset… | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Scream/Yell | 0.72 (1.04) | 0–4 | .13 | −.02 | .33 * | .26 * | .13 | .10 | .16 | .18 * | .32 * | .48 * | .18 * | – | ||||||||||||

| 13. Hit/Slam/Punch | 0.28 (0.70) | 0–4 | .13 | −.13 | .24 * | .32 * | .21 * | .10 | .08 | .16 | .25 * | .40 * | .20 * | .54 * | – | |||||||||||

| Parent-Report | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14. Externalizing Behavior (Questionnaire) | 15.16 (10.30) | 0–42 | .15 | .06 | .42 * | .40 * | .59 * | .46 * | .61 * | .60 * | .57 * | .27 * | .13 | .33 * | .28 * | – | ||||||||||

| Since the last prompt… | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Yell/Argue (EMA) | 1.87 (2.12) | 0–9 | −.01 | .03 | .21 * | .31 * | .33 * | .18 * | .16 | .33 * | .30 * | .29 * | .12 | .16 * | .13 | .46 * | – | |||||||||

| 16. Break/damage property (EMA) | 0.04 (0.19) | 0–1 | .00 | .00 | .05 | .13 | .24 * | .00 | .01 | .00 | −.03 | .01 | .00 | −.10 | −.08 | .05 | .12 | – | ||||||||

| Externalizing Behavior (Follow-up) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Youth-Report | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Externalizing Behavior Questionnaire | 10.81 (9.20) | 0–52 | .26 * | .22 * | .37 * | .35 * | .26 * | .18 | .22 * | .32 * | .65 * | .17 | .06 | .24 * | .17 | .39 * | .07 | −.04 | – | |||||||

| Since the last prompt… | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Yell/Argue (EMA) | 0.97 (1.64) | 0–9 | .04 | .09 | .13 | .05 | .05 | .04 | .08 | .09 | .20 * | .38 * | .06 | .24 * | .16 * | .14 | .19 * | .10 | .31 * | – | ||||||

| 19. Break/damage property (EMA) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0–1 | .14 | .02 | −.02 | .03 | .16 | −.02 | .05 | .10 | .12 | .22 * | .11 | .14 | .32 * | .16 | .07 | .11 | .22 * | .27 * | – | |||||

| Feeling your worst or most upset… | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20. Scream/Yell (EMA) | 0.49 (0.87) | 0–4 | .08 | .10 | .31 * | .06 | −.02 | .09 | .09 | .16 | .27 * | .30 * | .23 * | .30 * | .16 * | .21 * | .06 | .00 | .27 * | .48 * | .17 * | – | ||||

| 21. Hit/Slam/Punch (EMA) | 0.20 (0.55) | 0–3 | .07 | .03 | .24 * | .16 | .08 | .11 | .02 | .15 | .33 * | .26 * | .22 * | .20 * | .33 * | .20 * | .02 | −.01 | .26 * | .28 * | .18 * | .48 * | – | |||

| Parent-Report | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22. Externalizing Behavior (Questionnaire) | 13.01 (10.00) | 0–43 | −.02 | −.07 | .33 * | .40 * | .43 * | .30 * | .45 * | .48 * | .42 * | .19 * | .14 | .22 * | .25 * | .72 * | .38 * | .15 | .41 * | .09 | .09 | .15 | .25 * | – | ||

| Since the last prompt… | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23. Yell/Argue (EMA) | 1.41 (1.86) | 0–8 | .12 | .05 | .24 * | .27 * | .22 * | .18 * | .16 | .27 * | .28 * | .24 * | −.02 | .14 | .13 | .37 * | .43 * | .10 | .18 * | .45 * | .09 | .21 * | .15 | .31 * | – | |

| 24. Break/damage property (EMA) | 0.02 (0.14) | 0–1 | −.12 | −.15 | .12 | .26 * | .13 | .08 | .11 | .22 * | .14 | .20 * | −.03 | .13 | .27 * | .23 * | .03 | −.03 | .15 | .06 | .18 * | −.02 | .03 | .22 * | .19 * | – |

Callousness = Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits: callousness subscale, Uncaring = Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits: uncaring subscale, Antagonism = PID-5-BF: antagonism subscale substituting hostility item for callousness item, Disinhibition = PID-5-BF: disinhibition subscale, Externalizing behavior (questionnaire) = Child Behavior Checklist: externalizing behavior subscale, EMA = Ecological momentary assessment, all EMA variables are count variables summarizing the number of events reported during the EMA protocol

p < .05; Significant associations are also bolded

Agreement across informants for youth psychopathy features was in the low to moderate range, with disinhibition showing the highest agreement (r = 0.45), followed by uncaring (r = 0.36), antagonism (r = 0.30), and callousness (r = 0.17). Agreement between youth- and parent-reported externalizing behavior assessed via questionnaire was in the moderate range at baseline (r = 0.57) and follow-up (r = 0.41).

Associations between Psychopathic Features and Externalizing Behavior: Youth-report

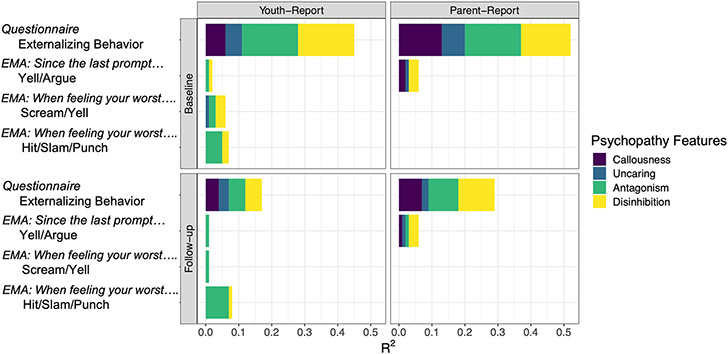

Figure 1 provides a summary of findings from general dominance analyses, and Table 2 includes more detailed results for associations between youth-reported psychopathic features and externalizing behavior, assessed via questionnaire and EMA at baseline and 9-month follow-up.

Fig. 1.

General Dominance Results for Parent- and Youth-Reported Psychopathy Features and Externalizing Behavior Note: Each segment of the bar chart represents the general dominance weight for youth- and parent-reported youth psychopathy features, and the general dominance weights sum to R2 for the regression model. Callousness = Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits: callousness subscale; Uncaring = Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits: uncaring subscale; Antagonism = PID-5-BF: antagonism subscale, substituting hostility item for callousness item; Disinhibition = PID-5-BF: disinhibition subscale; Externalizing behavior (questionnaire) = CBCL: externalizing behaviors scale; EMA = ecological momentary assessment; Baseline = externalizing behavior assessed at baseline; Follow-up = externalizing behavior assessed at 9-month follow-up

Table 2.

General Dominance Weights for Youth-Reported Psychopathy Features and Externalizing Outcomes

| Callousness |

Uncaring |

Antagonism |

Disinhibition |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GD Weight | 95% CI | GD Weight | 95% CI | GD Weight | 95% CI | GD Weight | 95% CI | Total R 2 | |

| Externalizing Behavior (Baseline) | |||||||||

| Questionnaire | |||||||||

| Externalizing Behavior | .06a (17%) | .02; .15 | .05a (11%) | .01; .12 | .17a (39%) | .09; .28 | .17a (39%) | .09; .25 | .44 |

| EMA | |||||||||

| Since the last prompt… | |||||||||

| Yell/Argue | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .01 (50%) | – | .01 (50%) | – | .02 |

| Break/damage property | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .00 |

| When you were feeling your worst or most upset… | |||||||||

| Scream/Yell | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .05 (63%) | – | .02 (25%) | – | .08 |

| Hit/Slam/Punch | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .01 (14%) | – | .02 (29%) | – | .03 (43%) | – | .07 |

| Externalizing Behavior (Follow-up) | |||||||||

| Questionnaire | |||||||||

| Externalizing Behavior | .04a (25%) | .00; .11 | .03a (19%) | .00; .09 | .05a (31%) | .01; .14 | .05a (31%) | .01; .14 | .16 |

| EMA | |||||||||

| Since the last prompt… | |||||||||

| Yell/Argue | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .01 (50%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .02 |

| Break/damage property | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| When you were feeling your worst or most upset… | |||||||||

| Scream/Yell | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .07 (78%) | – | .01 (11%) | – | .09 |

| Hit/Slam/Punch | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .01 (50%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .02 |

Percentages in parentheses represent the ratio of the general dominance weight to total R2. GD weights with mismatching superscripts indicate that the general dominance weights are significantly different from one another based on bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Matching superscripts indicate no significant differences between weights. The sum of general dominance weights does not always equal R2 due to rounding error. Results for EMA-Break/damage property are not reported at baseline due to singular fit of the multilevel model. Patterns of general dominance were not affected when including demographic covariates (age, sex, minority status, receipt of public assistance)

Callousness = Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits-Callousness, Uncaring = Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits-Uncaring, Antagonism = PID-5-BF-Antagonism substituting hostility item for callousness item, Disinhibition = PID-5-BF-Disinhibition, Externalizing Behavior (Questionnaire) = Child Behavior Checklist Externalizing Behaviors scale, EMA = Ecological momentary assessment; GD = General dominance

Questionnaire (Baseline)

At baseline, the combination of youth-reported callousness, uncaring, antagonism, and disinhibition accounted for a large amount of variance in externalizing behavior (R2 = 0.44). Antagonism (GD weight = 0.17) and disinhibition (GD weight = 0.17) showed the largest GD weights, with each accounting for 39% of the available R2 variance in externalizing behavior. Callousness (GD Weight = 0.06) and uncaring (GD Weight = 0.05) accounted for less variance in externalizing behavior (17% and 11%, respectively). However, the differences in the relative importance of youth-reported features were not statistically significantly based on bootstrapped comparisons of the GD weights.

Questionnaire (Follow-up)

At follow-up, the combination of youth-reported callousness, uncaring, antagonism, and disinhibition features accounted for a smaller, but significant, amount of variance in externalizing behavior (R2 = 0.16). Antagonism and disinhibition showed the largest general dominance weights (GD weight = 0.05), each accounting for 31% of the available R2 variance, followed by callousness (GD weight = 0.04, 25%), and uncaring (GD weight = 0.03, 19%). Bootstrapped comparisons of these GD weights showed no significant differences.

EMA (Baseline)

When examining externalizing behavior assessed via EMA at baseline, youth-reported callousness, uncaring, antagonism, and disinhibition accounted for a notably smaller amount of variance. For the EMA item assessing whether youth yelled or argued with anyone since the last prompt, these features accounted for limited variance in the outcome (R2 = 0.02). For the EMA item asking whether youth had broken or damaged any property since the last prompt, these features did not account for any significant variance (R2 < 0.001). Using alternative EMA items as to assess externalizing behavior, callousness, uncaring, antagonism, and disinhibition accounted for a larger amount of variance at baseline. For the EMA item asking youth if they yelled or screamed at someone when they were feeling their worst, the combination of callousness, uncaring, antagonism, and disinhibition accounted for an R2 = 0.08. Antagonism showed the greatest relative importance (GD weight = 0.05), accounting for 63% of the variance, followed by disinhibition (GD weight = 0.02; 25%). Callousness and uncaring accounted for almost no variance (i.e., less than 0.005) in the outcome. For the EMA item asking youth if they hit/slammed/punched someone or something when feeling their worst (R2 = 0.07), disinhibition showed the greatest relative importance, accounting for 43% of the available variance (GD weight = 0.03), followed by antagonism (GD weight = 0.02; 29%), and uncaring (GD weight = 0.01; 14%). Callousness accounted for almost no variance in the outcome.

EMA (Follow-up)

A similar pattern was observed during the EMA protocol at follow-up, with callousness, uncaring, antagonism, and disinhibition accounting for limited variance in the EMA item asking if youth had yelled or argued with anyone (R2 = 0.02). For the EMA item asking youth if they had broken or damaged property, the model resulted in singular fit, and thus, results are not presented. For the alternative EMA item asking youth if they yelled or screamed at someone when they were feeling their worst, these features accounted for an R2 = 0.09. Antagonism showed the greatest relative importance (GD weight = 0.07, 78%), followed by disinhibition (GD weight = 0.01, 11%). Callousness and uncaring accounted for almost no variance in the outcome. For the alternative EMA item asking youth if they hit/slammed/punched someone or something when feeling their worst, the R2 value was smaller (R2 = 0.02) and only antagonism had a notable GD weight (GD Weight = 0.01; 50%).

Associations between Psychopathic Features and Externalizing Behavior: Parent-report

Figure 1 provides a summary of findings from general dominance analyses, and Table 3 provides includes more detailed results for associations between parent-reported psychopathic features and externalizing behavior, assessed via questionnaire and EMA at baseline and 9-month follow-up.

Table 3.

General Dominance Weights for Parent-Reported Psychopathy Features and Externalizing Outcomes

| Callousness |

Uncaring |

Antagonism |

Disinhibition |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GD Weight | 95% CI | GD Weight | 95% CI | GD Weight | 95% CI | GD Weight | 95% CI | Total R 2 | |

| Externalizing Behavior (Baseline) | |||||||||

| Questionnaire | |||||||||

| Externalizing Behavior | .13ab (25%) | .08; .20 | .07b (13%) | .03; .13 | .17a (33%) | .11; .26 | .15ab (29%) | .09; .23 | .52 |

| EMA | |||||||||

| Since the last prompt… | |||||||||

| Yell/Argue | .02 (33%) | – | .01 (20%) | – | < .005 (~ 0%) | – | .03 (50%) | – | .06 |

| Break/damage property | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Externalizing Behavior (Follow-up) | |||||||||

| Questionnaire | |||||||||

| Externalizing Behavior | .07 (23%)ab | .03; .17 | .02 (17%)b | .01; .07 | .09 (30%)ab | .04; .18 | .11 (37%)a | .04; .21 | .30 |

| EMA | |||||||||

| Since the last prompt… | |||||||||

| Yell/Argue | .01 (20%) | – | .01 (20%) | – | .01 (20%) | – | .03 (60%) | – | .05 |

| Break/damage property | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Percentages in parentheses represent the ratio of the general dominance weight to total R2. GD weights with mismatching superscripts indicate that the general dominance weights are significantly different from one another based on bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Matching superscripts indicate no significant differences between weights. The sum of general dominance weights does not always equal R2 due to rounding error. Results for EMA-Break/damage property are not reported at baseline or follow-up due to singular fit of the multilevel models. Patterns of general dominance were not affected when including demographic covariates (age, sex, minority status, receipt of public assistance)

Callousness = Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits: callousness subscale, Uncaring = Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits: uncaring subscale, Antagonism = PID-5-BF: antagonism subscale substituting hostility item for callousness item, Disinhibition = PID-5-BF: disinhibition subscale Externalizing behavior (questionnaire) = CBCL: externalizing behaviors subscale, EMA = Ecological momentary assessment, GD = General dominance

Questionnaire (Baseline)

At baseline, parent-reported callousness, uncaring, antagonism, and disinhibition accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in externalizing behavior (R2 = 0.52). Antagonism (GD weight = 0.17, 33%) had the largest GD weight compared to other features, followed by disinhibition (GD weight = 0.15, 29%), callousness (GD weight = 0.13, 25%) and uncaring (GD weight = 0.07, 13%). Importantly, bootstrapped comparisons of GD weights indicated that differences between the GD weights were mostly non-significant, with one exception. Antagonism had a significantly larger GD weight than uncaring.

Questionnaire (Follow-up)

At follow up, parent-reported callousness, uncaring, antagonism, and disinhibition accounted a smaller proportion of the variance in externalizing behavior (R2 = 0.30), though a slightly different pattern of general dominance was observed. Disinhibition had the largest GD weight (GD weight = 0.11, 37%), followed by antagonism (GD weight = 0.09, 30%), callousness (GD Weight = 0.07, 23%) and uncaring (GD Weight = 0.02, 17%). Bootstrapped comparisons revealed that disinhibition had a significantly larger GD weight compared to uncaring; however, all other GD weights were not significantly different from each other.

EMA (Baseline)

At baseline, parent-reported callousness, uncaring, antagonism, and disinhibition accounted for a notably smaller amount of variance in externalizing behavior when assessed via EMA at baseline. EMA items assessing whether youth yelled or argued with anyone since the last prompt, accounted for a relatively small amount of variance (R2 = 0.06 at baseline). Disinhibition accounted for the most variance during the baseline EMA protocol (GD weight = 0.03, 50%), followed by callousness (GD weight = 0.02, 33%), and uncaring (GD weight = 0.01, 20%) while antagonism had a GD weight close to zero. For the EMA item asking whether youth had broken or damaged any property since the last prompt, the multilevel model resulted in a singular fit. Thus, findings are not reported.

EMA (Follow-up)

At follow-up, EMA items assessing whether youth yelled or argued with anyone since the last prompt, accounted for a similar amount of variance at follow-up (R2 = 0.05). Callousness, uncaring, and antagonism accounted for equal amounts of variance (GD weights = 0.01), while disinhibition had a GD weight of 0.03. The multilevel model resulted in a singular fit for the EMA broke/damaged property item outcome. Thus, findings for the model are not reported.

Secondary Analyses

Results for preregistered secondary analyses examining 1) the influence of the hostility item and 2) the influence of affective instability are presented in detail in the supplementary materials (Tables S3-S6). Overall, there was little change in R2 and the general dominance patterns across youth- and parent-reported psychopathy features and externalizing behavior were similar when excluding the hostility item and when including the affective instability in the models.

Additional secondary analyses focused on the inclusion of demographic covariates (youth age, race, sex, and family receipt of public assistance) in the general dominance analyses did not alter the results for any externalizing outcomes, at baseline or 9-month follow-up. These results are available using the publicly available code and data on the OSF page for the project. Secondary analyses focused on youth- and parent-reported aggression are presented in Tables S7-S8. Overall, there was little change in the R2, and the pattern of general dominance results for youth- and parent-reported psychopathy features in association with aggression remained similar with one exception. At baseline, youth-reported antagonism (GD weight = 0.17, 41%) showed a significantly larger GD weight compared to callousness (GD weight = 0.04, 10%) and uncaring (GD weight = 0.05, 12%), though no differences were observed for disinhibition (GD weight = 0.16, 38%). Lastly, cross-informant results were largely consistent with results from the primary analyses, though smaller R2 values were observed for the regression models (Tables S9 and S10). However, at baseline both youth- and parent-reported disinhibition showed a significantly larger general dominance weight compared to callousness and uncaring when examining associations with parent- and youth-reported externalizing behavior, respectively. Additionally, youth-reported antagonism showed a significantly larger general dominance weight compared to callousness and uncaring when assessing associations with parent-reported externalizing behavior at baseline. No significant differences were observed between general dominance weights at follow-up.

Discussion

The current study expanded on previous research by examining the relative importance of psychopathy features (i.e., antagonism, CU traits [callousness, uncaring], and disinhibition) as predictors of externalizing behavior in youth. Importantly, we implemented dominance analysis, an under-utilized statistical approach, to examine the relative importance of these features in a racially and socioeconomically diverse sample of clinically referred youth. We also extended past research by using a multi-informant, multi-method approach to examine the relative importance of psychopathy features across informant (youth- and parent-report) and type of assessment (questionnaire, EMA) as predictors of externalizing behavior, assessed cross-sectionally and at 9-month follow-up.

As expected, youth- and parent-reported psychopathy features accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in externalizing behavior cross-sectionally and longitudinally, and this was most robust for externalizing behavior assessed via questionnaire. However, findings from dominance analyses only partially supported our hypotheses. While antagonism and disinhibition had larger general dominance weights relative to CU traits for both youth- and parent-report, most differences were non-significant. This means that the interpersonal, affective, and behavioral psychopathy features could not be distinguished from each other in terms of their relative importance as predictors of externalizing behavior. Secondary analyses demonstrated that the results were robust to alternative modeling approaches, the inclusion of demographic covariates, and cross-informant analyses. These findings have broader implications for research on youth psychopathy and highlight promising directions for future research.

Understanding the Relative Importance of Youth Psychopathy Features

Our findings showed that youth- and parent-reported psychopathy features could not be distinguished from each other in terms of their relative importance in predicting externalizing behaviors (and aggression specifically), assessed cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Specifically, the youth- and parent-reported antagonism, CU traits, and disinhibition uniquely contributed to the prediction of externalizing behaviors. These findings are consistent with past research highlighting the utility of interpersonal and behavioral features of psychopathy alongside CU traits in the prediction of externalizing behaviors (e.g., Andershed et al., 2018; Colins et al., 2018). The findings also build on past work that has used measures explicitly designed to assess features of youth psychopathy (e.g., the Antisocial Process Screening Device; Frick & Hare, 2001), and emerging research (e.g., Colins et al., 2022) focused on the recently developed Proposed Specifiers for Conduct Disorder (Salekin & Hare, 2016). Specifically, the present results lend support to the notion that different personality features beyond CU traits may help differentiate youth with conduct problems (Salekin, 2017).

Importantly, the current study extends this work by leveraging the strengths of dominance analysis to empirically test the relative importance of youth psychopathy features as predictors of externalizing behavior. Results echo findings in adult samples using a similar analytic approaches (see ; Williams et al., 2007) and provide additional evidence for the argument that CU traits may be related to more severe and chronic externalizing problems due, at least in part, to the variance shared with other interpersonal and behavioral features of psychopathy. Taken together, this work underscores calls to expand assessment approaches to include other features of psychopathy given their incremental utility in the prediction of externalizing behavior (e.g., Salekin et al., 2018). Specifically, assessing a broader range of psychopathy features (i.e., antagonism, CU traits, disinhibition) may help to refine more tailored prevention and intervention efforts (e.g., Donohue et al., 2021).

There was one instance of significantly greater relative importance in our primary analyses. Specifically, parent-reported antagonism evidenced greater relative importance than uncaring. While research has consistently shown robust positive associations between both callousness and uncaring and externalizing behavior, only callousness shows positive associations with other forms of psychopathology (e.g., Byrd, Kahn, & Pardini, 2013; Frick et al., 1999). Given the nature of this clinical sample, it may be unsurprising that parent-reported uncaring evidenced less importance compared to other psychopathy features, and specifically antagonism, which has historically shown robust associations with externalizing behavior (e.g., Vize et al., 2020). Overall, the findings highlight the need for future research to assess if and how the unique variance of CU traits, relative to other psychopathy features, leads to more severe and chronic externalizing problems. This research may provide further insight into past work showing a lack of evidence for the incremental importance of CU traits when predicting conduct problems (e.g., Déry et al., 2019).

It is also important to note that all secondary analyses (e.g., alternative modeling approaches, the inclusion of demographic covariates) showed a very similar results, highlighting the potentially robust nature of these findings. Importantly, this pattern of findings generally persisted regardless of whether prediction was within- or cross-informant. While there was some evidence for greater importance of disinhibition and antagonism for externalizing behavior assessed at baseline, youth- and parent-reported psychopathy features were equally important in the prediction of youth- and parent-reported externalizing behavior at follow-up, and vice versa. This is particularly noteworthy given that the degree of interrater agreement for psychopathy features was low to moderate in this sample, a finding that is generally consistent with the previous work in this area (e.g., Decuyper et al., 2014; Matlasz et al., 2021). While the nature and cause of low interrater agreement for psychopathy remains a focus of ongoing research, these findings highlight the potential importance of incorporating and comparing multiple informants when examining the predictive utility of psychopathic features.

Differences in Questionnaire- and EMA-assessed Externalizing Behaviors

Findings were notably more robust for externalizing behavior assessed via questionnaire relative to EMA, with less variance accounted for in both youth- and parent-reported externalizing behaviors assessed via EMA. Given that psychopathy features were also assessed via questionnaire, this is likely related to shared method variance (Spector et al., 2019). It is also important to note that our assessment of externalizing behavior in daily life relied on aggregated counts of single items indexing low base rate behaviors (e.g., damaging property, aggression). Moreover, youth and their parents indicated whether these behaviors occurred over the course of a long weekend (i.e., 4 days). Thus, the endorsement of externalizing behavior in daily life was minimal, which impacted our ability to estimate associations between psychopathy features and externalizing behavior assessed via EMA. Ultimately, the current study should be understood as a preliminary investigation of associations between youth psychopathy features and externalizing behaviors in daily life.

Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that while both antagonism and disinhibition were associated with externalizing behavior assessed in daily life, youth-reported CU traits (callousness, uncaring) were not. While parent-reported CU traits did show positive, albeit smaller, associations with externalizing behavior assessed via EMA, future research may help further clarify these findings. Unfortunately, our EMA protocol was not designed to capture the unfolding of dynamic interpersonal and affective processes most relevant to youth psychopathy. Future EMA studies can build on the current results by exploring within-individual and dyadic dynamic processes relevant to externalizing behaviors (e.g., affective responses to interpersonal conflict) using measurements of maladaptive personality states (e.g., Zimmerman et al., 2019). Despite the promise of EMA methods to advance our understanding of interpersonal and affective dynamics central to conceptualizations of psychopathy (Wright & Zimmerman, 2019), studies utilizing EMA have been rare. Additionally, future work may aim to distinguish reactive versus proactive forms (Ritchie et al., 2022) and incorporate other validated EMA assessments of externalizing behavior (e.g., Murray et al., 2022) in process-oriented studies of youth psychopathy.

Limitations

Though we made use of a multi-informant, multi-method design, including both youth- and parent-reports and different types of assessment in a clinical sample of racially and socioeconomically diverse youth, the current findings should be considered within the context of several limitations. First, our sample size was relatively small, and this impacted our ability to detect significant differences between general dominance weights. Future research should aim to replicate this work in larger samples of clinically referred and community youth to enhance statistical power and precision of estimated effects, as well as the generalizability of findings. Second, while we used the ICU, one of the most commonly used measures of CU traits, we used a brief version of the PID-5 to assess antagonism and disinhibition. Future work would benefit from a more comprehensive assessment of these features, such as the 100-item short-form of the PID-5 (Maples et al., 2015). Additionally, the PID-5-BF was not developed as an informant-report measure, further underscoring the need to replicate the current results with other informant-based measures of youth psychopathy features. Third, the sample was comprised of youth in early adolescence. Future work should explore whether the patterns of dominance observed in the sample remain consistent across different development periods (e.g., late adolescence, emerging adulthood). Lastly, we focused exclusively on externalizing behavior as a primary outcome of interest, in line with previous work in this area (e.g., Andershed et al., 2018; Colins et al., 2018). Future research should examine differences in relative importance of psychopathy features as predictors of other forms of psychopathology and psychosocial competence as well as treatment response.

Conclusion

The current preregistered study found that the interpersonal, affective, and behavioral features of psychopathy could not be distinguished from each other in their ability to predict externalizing outcomes in a sample of clinically referred youth. Results underscore the utility of examining the relative importance of psychopathic features as predictors for externalizing behavior and suggests under-utilized techniques like general dominance analysis may enhance our ability to identify youth at risk for future externalizing problems. Importantly, these results were consistent across both youth- and parent-reported features and externalizing outcomes, alternative modeling approaches, the inclusion of demographic covariates, and cross-informant analyses, highlighting the robust nature of these findings. Future research will benefit examining these patterns in larger clinical and community samples and expanding outcomes to include specific types of externalizing behavior and other indices of psychopathology. Research in this area is also likely to benefit from incorporating preregistration and related approaches (e.g., registered reports; Chambers & Tzavella, 2022), as these tools provide many benefits to psychopathy-focused research, specifically (Verschuere et al., 2021). Ultimately, future work on the relative importance of youth psychopathy features make seek to examine the more nuanced unfolding of interpersonal, affective, and behavioral processes as predictors of externalizing behavior as well as explore the contexts where specific features of youth psychopathy may be more important than others.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the families who took part in this study, and to the MoodY study team, which includes interviewers and their supervisors, data managers, student workers, and volunteers.

Funding

This study was supported by grants awarded to Dr. Stephanie Stepp and Dr. Amy Byrd from the National Institute on Mental Health (R01 MH101088, F32 MH110077). Additional funding from the National Institute of Health also supported this work (T32 MH018269, K01 MH119216).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-022-10017-5.

Ethical Approval All study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (Protocol ID: STUDY19060128).

Conflict of Interest Colin E. Vize, Amy L. Byrd and Stephanie D. Stepp declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report.

Experiment Participants All study procedures were approved by the Human Research Protection Office (HRPO) and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) pediatric practice-based research network at the University of Pittsburgh. Youth and their parents provided written informed consent and were compensated for their time.

This measure includes three subscales (callousness, uncaring, unemotional), two of which have shown consistent reliability and moderate effect sizes in relation to externalizing behavior (Cardinale & Marsh, 2020).

Where the trait components of the PSCD fit within structural models of maladaptive personality remains an open question. For example, Sleep and colleagues (2020) examined the structure of antagonistic traits using 200 self-report items taken from various antagonism-related scales. At a relatively general level of specificity where three factors were examined, the factors (termed callousness, ruthless self-interest, and disconstraint) appear to significantly overlap with the callous-unemotional, grandiose-manipulative, and daring-impulsive traits of the PSCD. However, more structural research is needed to explicate how the PSCD fits within dimensional models of maladaptive personality.

The other five groups included youth with 1) externalizing behaviors only; 2) CU traits only; 3) other psychopathic features only (i.e., interpersonal, behavioral); 4) externalizing behaviors plus CU traits; and 5) a control group that had low scores externalizing behaviors, CU traits, and other psychopathic features.

Researchers often cite the seminal article by Farrington and Loeber (2000) when offering justifications for dichotomizing continuous variables. However, Iselin and colleagues (2013) highlight that many of the arguments in Farrington and Loeber (2000) do not stand up to empirical scrutiny. Iselin and colleagues (2013) ultimately conclude that it remains difficult to justify the dichotomization of continuous variables.

The total number of submodels examined in dominance analysis is equal to (2p − 1), where p is the number of predictor variables.

Though we do not discuss the goals and benefits of preregistration in detail, we refer interested readers to Lakens (2019) and Nosek et al. (2019) for insightful discussions of preregistration and its relevance to psychological science.

Ethnoracial composition for youth was 42% White, 40.7% Black, 3.7% Hispanic/Latino, 0.6% American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 16.7% multiracial.

Ethnoracial composition for caregivers was 53.7% White, 39.5% Black, 1.9% Hispanic/Latino, 0.6% Asian, and 6.2% multiracial.

Youth and parents completing both assessments were compared to those with missing data (i.e., those who only completed the first assessment) on all demographic covariates (age, sex, minority status, receipt of public assistance). Youth and parents with complete data did not differ from those who only completed the first assessment.

The alpha estimates for youth- and parent-reported antagonism are based on the inclusion of the hostility item. When the hostility item was excluded from the antagonism scale (i.e., antagonism was assessed with four items), the alpha values were .74 and .77 for youth- and parent-reported antagonism, respectively.

Compliance was high, with the average youth completing 91.1% of prompts at baseline and 9-month follow-up, and the average parent completing 90% of prompts at baseline, and 90.7% at 9-month follow-up.

The ratio of events to non-events for the “yell or argue” item was 226/1,238 at wave 1 (58% of youth self-reporting at least one event), and 157/1,135 at wave 2 (45% of youth reporting at least one event). The ratios for “break or damage property” item were 26/1,438 at wave 1 (only 8% of youth reporting at least one event), and 8/1,285 at wave 2 (only 6% of youth reporting at least one event).

These alternative EMA items, while still having a relatively low base rate, had less imbalanced ratios. At baseline, the ratio was 116/366 for yelling at someone (41% of youth reporting at least one event), and 46/436 for hitting/slamming/punching someone or something (19% of youth reporting at least one event). At 9-month follow-up, the respective ratios were 79/334 (34% of youth reporting at least one event) and 33/380 (17% of youth reporting at least one event).

Dominance analysis uses R2 as an index of model fit and partitions R2 based on the relative contributions of each predictor in the regression model. R2 is straightforward to compute in linear regression models because it is the ratio of variance in the outcome accounted for by the model relative to variance not accounted for (i.e., residual variance). However, in multilevel models there are multiple residual variance components (e.g., level 1 residual variance and level two residual variance) which complicates how R2 is used to index model fit. In the original preregistration for the study, we stated that would make use of the S&B R22 metric outlined in Luo & Azen (2013) which is based on the approach of Snijders and Bosker (1994) designed to estimate an R2 analogue for level-2 variables in multilevel models. However, this approach was not appropriate for dichotomous outcomes assessed via EMA. To correctly model the dichotomous EMA outcomes, we instead used an approach for obtaining R2 from generalized linear multilevel models as described by Nakagawa and Schielzeth (2013). Briefly, two variations of R2 can be examined in multilevel models—marginal R2 which is the variance explained by fixed effects, and conditional R2 which is the variance explained by the entire model (both fixed and random effects). Based on our primary research questions, we are most interested in the fixed effects of the model and thus, focus on marginal R2 when estimating general dominance weights for the EMA outcomes.

Emotional reactivity was assessed using the Affective Instability subscale from the PAI-A (Morey, 2007) administered at screening. This subscale is comprised of 6 items and assesses the tendency to experience intense, prolonged emotional responses and rapid and/or extreme changes in emotion. This subscale internal consistency was α = 0.62.

Aggression was assessed via youth- and parent-report at baseline and 9-month follow-up using the Aggressive Behavior subscale from the YSR (Achenbach, 1991) and CBCL (Achenbach, 1999). This subscale is comprised of 17 and 18 items, respectively, that assess engagement in a variety of aggression behaviors. This subscale showed good internal consistency at baseline (youth-report α = 0.89; parent-report α = 0.90) and follow-up (youth-report α = 0.87; parent-report α = 0.90).

Data Availability

All data and code to reproduce the analyses in the present paper are available at the OSF links detailed in the Method section.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF profiles: Department of Psychiatry. University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (1999). The Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments. In Maruish ME (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 429–466). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Satistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andershed H, Colins OF, Salekin RT, Lordos A, Kyranides MN, & Fanti KA (2018). Callous-Unemotional Traits Only Versus the Multidimensional Psychopathy Construct as Predictors of Various Antisocial Outcomes During Early Adolescence. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40, 16–25. 10.1007/s10862-018-9659-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JL, Sellbom M, & Salekin RT (2018). Utility of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 – Brief Form (PID-5-BF) in the Measurement of Maladaptive Personality and Psychopathology. 10.1177/1073191116676889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azen R, & Budescu DV (2003). The dominance analysis approach for comparing predictors in multiple regression. Psychological Methods, 8(2), 129–148. 10.1037/1082-989X.8.2.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrøm H, & Farrington DP (2018). Grandiose-manipulative, callous-unemotional, and daring-impulsive: the prediction of psychopathic traits in adolescence and their outcomes in adulthood. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 8, 333–344. 10.1108/JCP-07-2018-0029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bring J (1994). How to standardize regression coefficients. The American Statistician, 48, 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale EM, & Marsh AA (2020). The reliability and validity of the inventory of callous unemotional traits: a meta-analytic review. Assessment, 27, 57–71. 10.1177/1073191117747392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CD, & Tzavella L (2022). The past, present and future of Registered Reports. Nature Human Behaviour, 6, 29–42. 10.1038/s41562-021-01193-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1983). The cost of dichotomization. Applied Psychological Measurement, 7, 249–253. 10.1177/014662168300700301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colins OF, Andershed H, Salekin RT, & Fanti KA (2018). Comparing Different Approaches for Subtyping Children with Conduct Problems: Callous-Unemotional Traits Only Versus the Multidimensional Psychopathy Construct. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40, 6–15. 10.1007/s10862-018-9653-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colins OF, Bisback A, Reculé C, Batky BD, López-Romero L, Hare RD, & Salekin RT (2022). The Proposed Specifiers for Conduct Disorder (PSCD) Scale: Factor structure and validation of the self-report version in a forensic sample of Belgian youth. Assessment, Advance Online Publication. 10.1177/10731911221094256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colins OF, Fanti KA, & Andershed H (2021). The DSM-5 Limited Prosocial Emotions Specifier for Conduct Disorder: Comorbid Problems, Prognosis, and Antecedents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60, 1020–1029. 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Fraser J, Frost A, & Hawes DJ (2005). Disentangling the Underlying Dimensions of Psychopathy and Conduct Problems in Childhood: A Community Study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 400–410. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson NV, & Weiss R (2012). Dichotomizing continuous variables in statistical analysis: A practice to avoid. Medical Decision Making, 32, 225–226. 10.1177/0272989X12437605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decuyper M, De Caluwé E, De Clercq B, & De Fruyt F (2014). Callous-unemotional traits in youth from a DSM-5 trait perspective. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28, 334–357. 10.1521/pedi_2013_27_120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Déry M, Bégin V, Toupin J, & Temcheff C (2019). Clinical utility of the limited Prosocial emotions Specifier in the childhood-onset subtype of conduct disorder. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(12), 838–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue MR, Hoyniak CP, Tillman R, Barch DM, & Luby J (2021). Callous-unemotional traits as an intervention target and moderator of PCIT-ED treatment for preschool depression and conduct problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(11), 1394–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Marcus DK, Lilienfeld SO, & Poythress NG (2006). Psychopathic, not psychopath: Taxometric evidence for the dimensional structure of psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 131–144. 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Marcus DK, & Vaughn MG (2011). Exploring the taxometric status of psychopathy among youthful offenders: Is there a juvenile psychopath taxon? Law and Human Behavior, 35, 13–24. 10.1007/s10979-010-9230-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanti KA, Kyranides MN, Lordos A, Colins OF, & Andershed H (2018). Unique and interactive associations of callous-unemotional traits, impulsivity and grandiosity with child and adolescent conduct disorder symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40, 40–49. 10.1007/s10862-018-9655-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, & Loeber R (2000). Some benefits of dichotomization in psychiatric and criminological research. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 10, 100–122. 10.1002/cbm.349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feczko E, Miranda-Dominguez O, Marr M, Graham AM, Nigg JT, & Fair DA (2019). The Heterogeneity Problem: Approaches to Identify Psychiatric Subtypes. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23, 584–601. 10.1016/j.tics.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Somma A, Borroni S, Markon KE, & Krueger RF (2017). The personality inventory for DSM-5 brief form: evidence for reliability and construct validity in a sample of community-dwelling Italian adolescents. Assessment, 24, 615–631. 10.1177/1073191115621793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ (2009). Extending the construct of psychopathy to youth: Implications for understanding, diagnosing, and treating antisocial children and adolescents. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 803–812. 10.1177/070674370905401203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, & Hare RD (2001). Antisocial process screening device technical manual. Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Lilienfeld SO, Ellis M, Loney B, & Silverthorn P (1999). The association between anxiety and psychopathy dimensions in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(5), 383–392. 10.1023/A:1021928018403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, & Kahn RE (2014). Annual research review: A developmental psychopathology approach to understanding callous-unemotional traits in children and adolescents with serious conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 55(6), 532–548. 10.1111/jcpp.12152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, & Kahn RE (2014). Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1–57. 10.1037/a0033076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frogner L, Andershed AK, & Andershed H (2018). Psychopathic personality works better than CU traits for predicting fearlessness and ADHD symptoms among children with conduct problems. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40, 26–39. 10.1007/s10862-018-9651-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grömping U (2015). Variable importance in regression models. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 7, 137–152. 10.1002/wics.1346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guay JP, Ruscio J, Knight RA, & Hare RD (2007). A taxometric analysis of the latent structure of psychopathy: Evidence for dimensionality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 701–716. 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, & Neumann CS (2008). Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 217–246. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes SW, Mulvey EP, Schubert CA, & Pardini DA (2014). Structural coherence and temporal stability of psychopathic personality features during emerging adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 623–633. 10.1037/a0037078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt CS, Zeichner A, & Miller JD (2019). Laboratory aggression and personality traits: a meta- analytic review. Psychology of Violence, 9, 675–689. 10.1037/vio0000236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iselin AMR, Gallucci M, & DeCoster J (2013). Reconciling questions about dichotomizing variables in criminal justice research. Journal of Criminal Justice, 41, 386–394. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RE, Byrd AL, & Pardini DA (2013). Callous-Unemotional Traits Robustly Predict Future Criminal Offending in Young Men. Law and Human Behavior, 37, 87–97. 10.1037/b0000003.Callous-Unemotional [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]