Abstract

Objectives:

Hyperemesis gravidarum is a severe form of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy sufficiently enough to produce weight loss greater than 5%, dehydration, ketosis, alkalosis, and hypokalemia. Several studies have investigated risk factors for hyperemesis gravidarum in Ethiopia, but the studies have reported conflicting results attributed to study design, lack of proper sample size, and the selection of variables. This study aimed to assess the determinants of hyperemesis gravidarum among pregnant women in public hospitals of Guji, West Guji, and Borana zones, Southern Ethiopia, 2022.

Methods:

An institutional-based case–control study design was conducted from April 15 to June 15, 2022 with a ratio of 1:2 (103 cases and 206 controls). Cases were all pregnant women admitted with a diagnosis of hyperemesis gravidarum by a clinician while controls were pregnant women who were visiting antenatal care services at the same time. Cases were selected consecutively until the required sample size is attained, while controls were selected by a simple random sampling technique. Data were collected using structured questionnaires with face-to-face interviews. The collected data were cleaned, coded, and entered into EpiData version 3.1, and then exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Frequency distribution for categorical variables, median, and interquartile range for continuous variables was computed. Backward stepwise logistic regression analyses were done. A significant association was declared with a 95% confidence interval at a p value less than 0.05.

Results:

Those mothers who had antenatal follow-up (adjusted odds ratio = 0.082, 95% confidence interval: 0.037–0.180), pregnancy with multiple gestations (adjusted odds ratio = 3.557, 95% confidence interval: 1.387–9.126), previous history of hyperemesis gravidarum (adjusted odds ratio = 6.66, 95% confidence interval: 2.57–17.26), family history of hyperemesis gravidarum (adjusted odds ratio = 2.067, 95% confidence interval: 1.067–4.015), and those women had exercised before pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio = 0.352, 95% confidence interval: 0.194–0.639) were determinants of hyperemesis gravidarum.

Conclusion:

Antenatal follow-up, number of the fetus, previous and family history of hyperemesis gravidarum, and exercise before pregnancy were significantly associated with outcome. Lifestyle modification, early treatment, and early ultrasound scans for pregnant women are crucial to reducing the burden of hyperemesis gravidarum.

Keywords: Bule Hora, hyperemesis gravid arum, determinant, Guji, Borana, South Ethiopia

Introduction

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is a severe form of nausea and more than three episodes of vomiting per day which is sufficient enough to produce weight loss greater than 5%, dehydration, ketosis, alkalosis, hypokalemia, and nutritional disturbances, the presence of ketones in the urine and requires hospitalization. HG is less common but it is more severe.1,2

The main cause of HG is rapidly raising serum levels of hormones like human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) and estrogen. However, various other hormones such as progesterone, leptin, placental growth hormone, prolactin, thyroid, and adrenal cortical hormones have been implicated in the etiology of HG. This is a hormone created during pregnancy by the placenta. The body produces a large amount of this hormone at a rapid rate early in pregnancy. These levels can continue to rise throughout the pregnancy. 3

The exact cause of HG is unknown, but several recognized risk factors may increase the likelihood of developing this condition. Risk factors for the development of hyperemesis gravidrum include multiple pregnancies, primigravida, prior history of HG, molar pregnancy, unexpected pregnancy, and family history of HG. 4

Globally, the prevalence of HG ranges between 0.3% and 3%, but in our country, it is 4%–8%.1,5 HG has been linked to substantial maternal and fetal morbidity, including Wernicke’s encephalopathy, fetal growth restriction, and even death. Long-term, intense vomiting can cause esophageal mucosal injury/tear (Mallory-Weiss syndrome), esophageal or splenic rupture, choroid bleedings, transient hypothyroxinemia, pneumothorax, and neurological complications such as myelinolysis of the cerebellum or Wernicke encephalopathy due to a vitamin B1 deficiency. 6

HG is the most common reason for hospitalization in the first half of pregnancy in the United States, second only to preterm labor. HG affects 3% of all pregnancies and the percentage fluctuates depending on the diagnosis criteria, as well as ethnic diversity in the research populations. Despite substantial research, the disease’s mechanism remains not well known. Although deaths from HG are uncommon, it has been linked to both maternal and fetal morbidity. Currently, the mainstay of treatment is relying significantly on supportive measures till the situation improves symptoms as part of the natural course of HG, which develops as the pregnancy progresses. 7

Hyperemesis has a significant impact on one’s health and ability to function in daily life, functioning, as well as body pain, overall health perception, vitality, and mental health are all affected. 8 Furthermore, according to a recent Norwegian study, roughly 25% of women with HG consider terminating the pregnancy, and 75% prefer not to become pregnant again. Hyperemesis also has a significant financial impact on women and their families. 9

Hyperemesis has been shown to have a deleterious influence on maternal physical and psychological well-being, as well as fetal growth and health of offspring in South Africa. 10 In Ethiopia, HG also poses a grave consequence for both the mother and fetus. Some maternal burdens are social, psychological, and mental depression while fetal consequences are preterm labor, stillbirth, miscarriage, fetal, growth restriction, and in the same condition it may reach until termination of pregnancy. 11

The data regarding HG in Ethiopia are deficient and needs further enlightenment. According to research done in Arba Minch, the prevalence of HG is 8.2%, and also research done in Jimma indicates a prevalence of HG is 4.8% and the majority of them are admitted in their first-trimester pregnancy. Both these studies are done in a limited place and are also difficult for the conclusion of the problem. The research which is done in Jimma use a convenient sampling method which is difficult to generalization of the problem and the research which is done in Arba, Minch misses very crucial variable like unplanned pregnancy and first-trimester pregnancy which is significant in other places.4,5

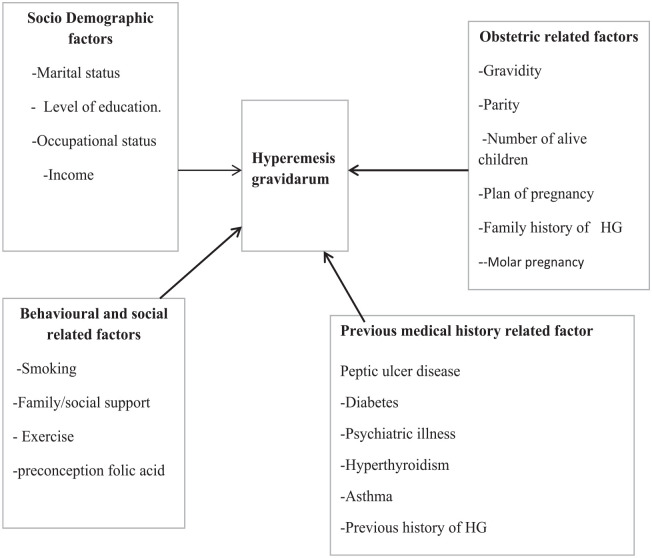

Despite many studies that have investigated risk factors for HG in Ethiopia, the studies have reported conflicting results in terms of study design, lack of proper sample size, and the selected variable. Some variables, like antenatal care (ANC) follow-up, preconception of folic acid, and smoking, were not addressed in the previous Ethiopian study, so this study is interested to see how those variables relate to HG. Therefore, the goal of this study is to find out what factors are linked to HG. The conceptual framework for this study was developed after reviewing different literature (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of factors associated with HG among pregnant women in public hospitals of Guji, West Guji and Borana Zone, southern Ethiopia, 2022.

Methods and materials

Study area and period

The study was conducted in West Guji Zone, Guji Zone, and Borana Zone public hospitals, Oromia region, southern Ethiopia. West Guji zone is one of the zones of the Oromia regional state. The capital city of the West Guji zone is Bule Hora which is located 467 km away from Addis Ababa. The total population of the West Guji zone is 1,428,109 of which 712,627 are males and 715,482 are females. 12 The total number of pregnant women in West Guji zone is 49,555. It is located at the 5°35′N latitude and 38°15′E and an altitude of 1716 m above sea level. The zone has 1 teaching hospital, 2 primary hospitals, 42 health centers, and 166 health posts.

Guji zone is found in the southwest of Ethiopia 590 km far away from the capital city of the country (Addis Ababa). The capital city of the Guji zone is Negelle. This zone has four public hospitals those are Negelle Hospital, Adola Woyu Hospital, Bore Hospital, and Uraga Hospital. Borana zone is found in the southern part of Ethiopia 568 km far away from the capital city of Addis Ababa. Borana zone has five public hospitals; those are Yabelo General Hospital, Mega primary hospital, Arero primary hospital, Taltalle primary hospital, and Moyale primary hospital. The study was conducted from April 15 to June 15, 2022 G.C.

Study design

An institutional-based unmatched case–control study design was employed.

Populations

Source population

All pregnant women who visited the maternity center of Guji, West Guji, and Borana zone public hospitals.

Study population

All pregnant women admitted with a diagnosis of HG during the study period were the study population for the case, whereas all pregnant women who visited the hospitals for ANC services during the study period were the study population for controls.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

All pregnant women admitted with a diagnosis of HG by a clinician were taken as cases and pregnant women who were visiting ANC services at the same time but did not have symptoms of HG were included as controls.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant women were excluded from being cases if they had concurrent illnesses (gastroenteritis, pancreatitis, peptic ulcer disease, pyelonephritis, urinary tract infection, and any other acute illness like malaria, or small bowel obstruction) that could cause nausea and vomiting which may confound the diagnosis of HG and a mother referred from selected hospital after interviewed there.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated with the assumption of a double population proportion formula for an unmatched case–control study using Epi Info software version 7.0. The following parameters were considered: 95% confidence interval, power was 80%; control to case ratio was 2:1 and different sample sizes were produced from previously identified determinants of HG, and the maximum sample size was obtained by taking unplanned pregnancy as a determinant factor from a previous study done in northern Ethiopia, where the proportion of exposure among cases to be 27.6% and among controls 12.9% with an odds ratio of 2.58. This yields a maximum sample size of 282 (94 cases and 188 controls). By adding a 10% nonresponse rate (Table 1), the final sample size required for the study was 103 cases and 206 controls. All cases that were clinically diagnosed as HG were selected with daily monitoring of all new admissions until the sample size was fulfilled. Controls were selected from the ANC unit. For each case, two controls were selected on the same day when a case was diagnosed with HG. 13

Table 1.

Sample size determination for factors associated with HG among pregnant women of Guji, West Guji, and Borana zone, southern Ethiopia, 2022.

| Sr. no. | Variables | Confident interval (CI) | Power | Percent among control | Percent among case | Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) | Nonresponse rate | Total sample size for case | Total sample size for control | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Being housewife | 95% | 80 | 25.2 | 45.7 | 2.43 | 10 | 81 | 162 | Tefera and Assefaw 13 |

| 2 | Unplanned pregnancy | 95% | 80 | 12.9 | 27.6 | 2.58 | 10 | 103 | 206 | Tefera and Assefaw 13 |

| 3 | Previous family history of hyperemesis gravidarum | 95% | 80 | 9 | 20 | 3.85 | 10 | 61 | 122 | Tefera and Assefaw 13 |

| 4 | First-trimester pregnancy | 95% | 80 | 22.9 | 32.4 | 6.01 | 10 | 22 | 44 | Tefera and Assefaw 13 |

Data collection procedure and instrument

Sampling procedure

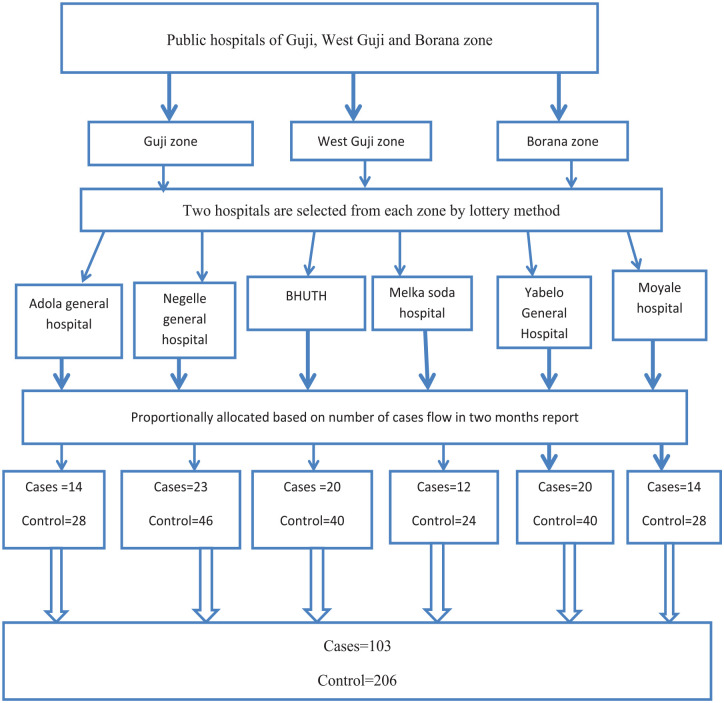

Two hospitals were selected from each zone by lottery method. Those hospitals were selected as study areas: Bule Hora University Teaching Hospital and Melka Soda Hospital from the West Guji zone, Adola General Hospital and Negelle General Hospital from the Guji zone, and Yabello General Hospital and Moyale Hospital from the Borana zone. The sample size was distributed proportionally to each hospital by taking into account the last year’s 2-month reports of the admitted cases. The case records from April through June of last year were used to compile the 2-month report. Their case updates after 2 months were 28, 20, 20, 32, 28, and 16 for Yabelo, Moyale, Adola, Negele, and Bule Hora University Teaching Hospital, respectively. The sample size for cases was proportionally distributed to each hospital based on their prior report. Therefore, the samples for Yabelo, Moyale, Adola, Negele, Bule Hora University Teaching Hospital, and Melka Soda were, respectively, 20, 14, 14, 23, 20, and 12 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of sampling procedure for determinants of HG among pregnant women in public hospitals of Guji, West Guji, and Borana zone, southern Ethiopia, 2022.

Data collection instrument

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire that was adapted after reviewing different literature.4,13 The questionnaire is prepared in English and translated to Afaan Oromo and back to the English language to maintain its consistency. The questionnaire has four parts covering areas on socio-demographic characteristics, obstetrics conditions, previous medical history related, and behavioral and social-related factors. Two BSc midwifery professionals were recruited at each hospital as data collectors and one public health officer from a nearby health center was assigned as supervisor.

Study variables

Dependent variables

Hyperemesis gravidarum.

Independent variables

Socio-demographic factors: Age, residence, ethnicity, occupational status, marital status, educational status, religion, income;

Obstetrics factors: Gravidity, parity, ANC visit, number of alive children, plan of pregnancy;

Behavioral and social related: Smoking, alcohol intake, exercise, social/family support, and molar pregnancy; and

Previous medical history related: Peptic ulcer disease, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, family history of hg, motion sickness, asthma, and psychiatric disorders.

Operational definitions

Case: defined as pregnant women admitted with a diagnosis of HG by a physician.

Control: Defined as pregnant women who visit ANC services but do not have symptoms of HG.

Nausea and vomiting: Refers to morning sickness that occurs at any time, day or night in pregnancy as per the woman’s report. 14

Exercise before pregnancy: Physical activity normally leaves the women exhausted, but not breathless (e.g., brisk walking, gardening). 15

Hyperemesis gravidarum: Defined as a severe form of nausea and repeated vomiting during pregnancy that leads to greater than 5% weight loss, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance and results in an admission. 16

Social/family support: Experience in obtaining support from husband, family, friends, or neighbors if required. 17

Unplanned pregnancy: A pregnancy that occurred when no children were desired or that occurred earlier than desired. 18

Unwanted pregnancy: A pregnancy that has occurred to a woman who not wants to become pregnant at the time of conception or in the future. 18

Motion sickness: Nausea and vomiting which start while traveling by car, airplane, and boat which is not related to pregnancy. 19

Data quality control

The training was provided for data collectors and supervisors at each site for 2 days by the principal investigator. The principal investigator and supervisors were supervising data collectors daily and making necessary corrections to the data collection process. The collected data were submitted daily to ensure its completeness and consistency. Any error, ambiguity, and incompleteness were discussed and solved immediately. Depending on the finding from the pretest, problem like skip pattern and translation were solved. Questionnaires were translated into the Afaan Oromo and again re-translated to English by a language expert. Before actual data collection, pretest was done on 5% of the total sample size at Kerca primary hospital to assess, the clarity, sequence, consistency, understandability, and total time taken to complete the questionnaire. The reliability of the data was checked using Cranach’s alpha and its value is 0.72 which shows the data are reliable.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were checked for completeness, coded, entered, and cleaned using EpiData 3.1, and then exported to SPSS 25 for analysis. Both descriptive statistics and regression analyses were computed. Descriptive statistical analysis was computed to summarize and describe the characteristics of study participants and the information was presented using frequencies, summary measures, tables, and figures.

In bivariable analysis, crude odds ratio (COR) with 95% CI was used to see the association between each independent variable and dependent variable by using binary logistic regression. The result was presented as COR to show the strength of the association between independent variables and dependent variables. Independent variables with a significance level of p value <0.25 in the bivariable analysis were selected as a candidate for multivariable analysis. Multicollinearity was checked to see the linear correlation among the associated independent variables using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF of the data was <10 and no sign of multicollinearity was detected.

In multivariable analysis, a backward stepwise logistic regression model was done to control the confounders. Hosmer and Lemeshow’s goodness-of-fit test was checked, and it was found to be insignificant (p = 0.881) which indicates the model was fitted. AOR with 95% CI was estimated to show the strength of association between the independent variables and the dependent variable after controlling the effects of confounders. Independent variables with p value <0.05 were declared as having statistically significant association with the dependent variable.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

In this study, a total of 103 cases and 206 controls were successfully interviewed with a response rate of 100%. The highest proportion of cases (56%) was in the age group 19–24 and (48%) of the control were in the age group of 25–34 years. The median age of the case and control was 22 (interquartile range (IQR) = 6) and 24 (IQR = 6) years, respectively. The majority of cases (64%) and controls (62.6%) were living in urban. The majority (49.5%) of cases and (62.6%) of controls were protestant. Ninety-two percent of cases and 93.7% of controls were married. About 52% of cases and 55.8% of controls were housewives. The majority of cases (40.7%) were no formal education and (33.9%) of control were grades 1–8. Around 87 cases and 78 controls were family sizes less than or equal to four. About 66% of cases and 62% of controls were found in rural areas (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women in Guji, West Guji, and Borana zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022.

| Characteristics | Category | Case (N = 103), N (%) | Control (N = 206), N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ⩽18 | 14 (13.6) | 24 (11.7) |

| 19–24 | 58 (56.3) | 82 (39.8) | |

| 25–34 | 31 (30.1) | 100 (48.5) | |

| Marital status | Married | 95 (92.2) | 193 (93.7) |

| Single | 6 (5.8) | 6 (2.9) | |

| Other* | 2 (2%) | 7 (3.4) | |

| Religion | Protestant | 51 (49.5) | 129 (62.6) |

| Muslim | 25 (24.3) | 32 (15.6) | |

| Orthodox | 24 (23.3) | 39 (18.9) | |

| Other** | 3 (2.9) | 6 (2.9) | |

| Ethnicity | Oromo | 63 (61.2) | 167 (81.1) |

| Amara | 17 (16.5) | 10 (4.9) | |

| Gurage | 18 (17.5) | 20 (9.7) | |

| Other*** | 5 (4.8) | 9 (4.3) | |

| Residence | Rural | 66 (64) | 129 (62.6) |

| Urban | 37 (36) | 77 (37.4) | |

| Educational level | No formal education | 42 (40.8) | 62 (30.1) |

| Grade 1–8 | 26 (25.2) | 70 (34) | |

| Grade 9–12 | 23 (22.3) | 48 (23.3) | |

| College and above | 12 (11.7) | 26 (12.6) | |

| Occupation | Housewife | 54 (52.4) | 115 (55.8) |

| Merchant | 21 (20.3) | 28 (13.6) | |

| Government employ | 11 (10.7) | 37 (18) | |

| Student | 12 (11.7) | 8 (3.9) | |

| Self-employ | 5 (4.9) | 18 (8.7) | |

| Family size | ⩽4 | 90 (87.3) | 161 (78.2) |

| 5–7 | 12 (11.7) | 34 (16.5) | |

| ⩾8 | 1 (1) | 11 (5.3) |

*Widowed and divorced.

Catholic and wakefata.

Burji, Wolaita, and Somali.

Obstetrics and gynecologic characteristics of respondents

The proportion of multigravida among cases and controls was 66% and 70.9%, respectively. In the majority of cases, 62% were admitted during the first trimester of pregnancy. About 36.9% of cases were pregnant for the first time while 58.7% of controls were inter-pregnancy intervals greater than 2 years. About 80% of cases and 90% of controls reported that the current pregnancy was planned. Most of the pregnancies (79.6%) among cases and 93.7% among controls were singletons. Around 86% of cases and 44% of control were no ANC follow-up at health institutions. A similar proportion of cases and control was history of molar pregnancy. Five percent of cases and around 6% of controls had a history of stillbirth (Table 3).

Table 3.

Obstetric characteristics of pregnant women in Guji, West Guji, and Borana zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022.

| Variable | Category | Case (N = 103), N (%) | Control (N = 206), N (%) | Total (N = 309), N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravida | Primigravida | 35 (34) | 60 (29.1) | 95 (30.7) |

| Multigravida | 68 (66) | 146 (70.9) | 214 (69.3) | |

| Pregnancy interval | <24 months | 32 (31.1) | 24 (11.7) | 56 (18.1) |

| ⩾24 months | 33 (32) | 121 (58.7) | 154 (49.8) | |

| The first time | 38 (36.9) | 61 (29.6) | 99 (32.1) | |

| Gestational age (month) | ⩽3 months | 64(62.14) | 10 (5) | 74 (23.9) |

| 4–6 months | 38 (36.89) | 97 (47) | 135 (43.7) | |

| ⩾6 months | 1(0.97) | 99 (48) | 100 (32.4) | |

| Type of pregnancy | Planned | 83 (80.6) | 187 (90.8) | 270 (87.4) |

| Unplanned | 20 (19.4) | 19 (9.2) | 39 (12.6) | |

| Received ANC | Yes | 14 (13.6) | 114 (55.3) | 128 (41.4) |

| No | 89 (86.4) | 92 (44.7) | 181 (58.6) | |

| Number of fetuses | Singleton | 82 (79.6) | 193 (93.7) | 275 (89) |

| Multiple | 21 (20.4) | 13 (6.3) | 34 (11) | |

| History of stillbirth | Yes | 5 (4.9) | 12 (5.8) | 17 (5.5) |

| No | 98 (95.1) | 194 (94.2) | 292 (94.5) | |

| History of molar pregnancy | Yes | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | 6 (2) |

| No | 101 (98) | 202 (98) | 303 (98) |

Behavioral and social-related factors

The highest proportions of cases were no social and family support while 67% of controls were social and family support during pregnancy. Around 72% of cases and 41.7% of controls were no exercise before this pregnancy. Only 3% of cases and 5% of controls took preconception folic acid. The proportion of mothers who smoked during pregnancy in case and control were 4% and 1.5%, respectively. Ninety-five percent of the case and 97% of control were not drunk alcohol during pregnancy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Social and behavioral related factors of respondents in Guji, West Guji, and Borana zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022.

| Variable | Category | Case (N = 103), N (%) | Control (N = 206), N (%) | Total (N = 309), N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and family support | yes | 36 (35) | 138 (67) | 174 (56.3) |

| No | 67 (65) | 68 (33) | 135 (43.7) | |

| Exercise before pregnancy | Yes | 29 (28.2) | 120 (58.3) | 149 (48.2) |

| No | 74 (71.8) | 86 (41.7) | 160 (51.8) | |

| Folate before pregnancy | yes | 3 (3) | 10 (5) | 13 (4.2) |

| No | 100 (97) | 196 (95) | 296 (95.8) | |

| Smoking during pregnancy | yes | 4 (4) | 3 (1.5) | 7 (2.3) |

| No | 99 (96) | 203 (98.5) | 302 (97.7) | |

| Drinking alcohol | Yes | 5 (5) | 6 (3) | 11 (3.6) |

| No | 98 (95) | 200 (97) | 298 (96.4) | |

| Chewing khat | yes | 12 (11.7) | 7 (3.4) | 19 (6.2) |

| No | 91 (88.3) | 199 (96.6) | 290 (93.8) |

Medical and psychological characteristics of respondents

Concerning medical characteristics, the proportion of history of peptic ulcer disease among cases was 32% and that of controls was 19%. Twenty-five percent of the cases and 5% of controls were reporting a previous history of HG. About 13% of cases and 3.9% of controls were a previous history of diabetes. Pre-pregnancy motion sickness was reported in 15.5% of cases and 13.1% of controls. Thirty-six percent of cases and 21% of controls were reporting a family history of HG in their mothers and sisters. Around 8% of cases and 3.4% of controls were reporting a previous history of hyperthyroidism (Table 5).

Table 5.

Previous medical and psychological related factor respondents in Guji, West Guji, and Borana zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022.

| Characteristics | Category | Case (N = 103), N (%) | Control (N = 206), N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous history of HG | Yes | 26 (25.2) | 10 (5) |

| No | 77 (74.8) | 196 (95) | |

| Family history of HG | Yes | 37 (36) | 43 (21) |

| No | 66 (64) | 163 (79) | |

| History of PUD | Yes | 33 (32) | 39 (19) |

| No | 70 (68) | 167 (81) | |

| History of DM | Yes | 13 (12.6) | 8 (3.9) |

| No | 90 (87.4) | 198 (96.1) | |

| History of hyperthyroidism | Yes | 8 (7.8) | 7 (3.4) |

| No | 95 (92.2) | 199 (96.6) | |

| History of psychiatric disorder | Yes | 2 (2) | 4 (2) |

| No | 101 (98) | 202 (98) | |

| History of motion sickness | Yes | 16 (15.5) | 27 (13.1) |

| No | 87 (84.5) | 179 (86.9) | |

| History of asthma | Yes | 5 (5) | 3 (1.5) |

| No | 98 (95) | 203 (98.5) |

DM: diabetes mellitus; HG: hyperemesis gravidarum; PUD: peptic ulcer disease.

Determinants of HG

Bivariable analyses were done between independent variables and HG. The bivariable analyses revealed that ANC follow-up, number of the fetus, a previous history of HG, exercise, history of DM, history of hyperthyroidism, unplanned pregnancy, a family history of HG, history of PUD, and social and family support were found to have an association with the development of HG. After controlling for potential confounds on multivariable logistic regression analysis, those who had ANC follow-up, multiple gestation, had a previous history of HG, family history of HG, and those who had exercised before pregnancy were identified as determinants of HG among pregnant women.

Accordingly, pregnant women who had ANC follow-ups were 92% less likely to develop HG as compared to pregnant women who had no ANC follow-ups (AOR = 0.082, 95% CI: 0.037–0.180). In the same manner, women who were exercising before pregnancy were 65% less likely to develop HG as compared to women who did not do exercise before pregnancy (AOR = 0.352, 95% CI: 0.194–0.639). Women with twin and above gestation were 3.56 times at increased risk of developing HG as compared to women with singleton gestation (AOR = 3.56; 95% CI: 1.38–9.120).

Pregnant women who had a family history of HG were 2.06 times more likely to develop HG as compared to those who had no family history of HG (AOR = 2.067; 95% CI: 1.064–4.02). Similarly, women who had a previous history of HG were 6.667 times more likely to develop HG compared to women who had no previous history of HG (AOR = 6.667, 95% CI: 2.57–17.27) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Determinants of HG of pregnant women in Guji, West Guji, and Borana zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022.

| Variable | Case (N = 103) | Control (N = 206) | COR 95% CI | AOR 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANC follow up | ||||

| Yes | 14 (13.6) | 114 (55.3) | 0.127 (0.068 0.238) | 0.082 (0.037–0.18) |

| No | 89 (86.4) | 92 (44.7) | 1 | 1 |

| Number of fetuses | ||||

| Twin and above | 21 (20.4) | 13 (6.3) | 3.8 (1.817–7.956) | 3.56 (1.38–9.12) |

| Singleton | 82 (79.6) | 193 (93.7) | 1 | 1 |

| Unplanned pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 83 (80.6) | 187 (90.8) | 0.42 (0.214–0.83) | 0.53 (0.23–1.22) |

| No | 20 (19.4) | 19 (9.2) | 1 | 1 |

| Family history of HG | ||||

| Yes | 37 (36) | 43 (21) | 2.125 (1.26–3.59) | 2.067 (1.06–4.02) |

| No | 66 (64) | 163 (79) | 1 | 1 |

| Previous history of HG | ||||

| Yes | 26 (25.2) | 10 (5) | 6.618 (3.05–14.37) | 6.66 (2.57–17.27) |

| No | 77 (74.8) | 196 (95) | 1 | 1 |

| Social and family support | ||||

| Yes | 36 (35) | 138 (67) | 0.265 (0.161–0.436) | 0.699 (0.36–1.34) |

| No | 67 (65) | 68 (33) | 1 | 1 |

| Exercise | ||||

| Yes | 29 (28.2) | 120 (58.3) | 0.28 (0.16–0.46) | 0.35 (0.194–0.639) |

| No | 74 (71.8) | 86 (41.7) | 1 | 1 |

| History of DM | ||||

| Yes | 13 (12.6) | 8 (3.9) | 3.57 (1.4–8.93) | 1.9 (0.5–7.3) |

| No | 90 (87.4) | 198 (96.1) | 1 | |

| History of PUD | ||||

| Yes | 33 (32) | 39 (19) | 2.019 (1.17–3.47) | 1.5 (0.78–3.06) |

| No | 70 (68) | 167 (81) | 1 | 1 |

| History of hyperthyroidism | ||||

| Yes | 8 (7.8) | 7 (3.4) | 2.39 (0.84–6.79) | 0.88 (0.23–3.36) |

| No | 95 (92.2) | 199 (96.6) | 1 | |

1: Reference; AOR: adjusted odd ratio and significantly associated variables were bolded; CI: confidence interval; COR: crude odd ratio; DM: diabetes mellitus; HG: hyperemesis gravidarum; PUD: peptic ulcer disease.

Discussion

This finding shows those who have ANC follow-up, twin and above gestation, had a previous history of HG, family history of HG, and those who had exercised before pregnancy were identified as determinants of HG among pregnant women in the study area.

The finding shows that those pregnant women who had ANC follow-up were a protective effect on the development of HG as compared to pregnant women who had no ANC follow-up. This variable is not studied yet in our country and the globe. The possible explanation for the observed association could be that pregnant women who had ANC follow-up may get advice and awareness on the minor disorder during pregnancy and how to get early treatment before the condition worsen. Also, those women who had ANC follow-up got health education concerning lifestyle modification and a healthy diet. This finding shows that twin and above gestation was significantly associated with the development of HG as compared to singleton gestation. This is supported by a study conducted in Gamo Gofa southern Ethiopia and a study done in Egypt.4,20 The possible explanation is that in the case of multiple pregnancies, there is a rapidly rising serum level of hormones such as HCG and estrogen and evidence of increasing placental mass in the case of multiple pregnancies. 3

This study also shows that a family history of HG was significantly associated with HG as compared to those who had no family history of HG. This finding was supported by a study conducted in northern Ethiopia, southern Ethiopia, and a study done in Nigeria.13,21 This is the fact that the genetic predisposition to the condition, evidence supports that daughter women who experienced the condition were at increased risk of developing HG. Family-based studies provide evidence that female relatives of patients with HG are more likely to be affected, with a 17-fold increased risk if a sister has HG. 22 This finding contradicts a study conducted in the Bale zone, South Ethiopia in which no association was seen between HG and a family history of HG. 4 The possible reason for the difference could be that the family history of HG was based on self-report, which may lead to misclassification. However, this finding is consistent with a study conducted in Norway which shows that women with hyperemesis were at significantly higher risk of developing hyperemesis in their pregnancy compared with daughters of women without hyperemesis. 23 This finding is also consistent with a study conducted in the United States which shows a significantly higher risk of hyperemesis in women whose sisters or mothers had the disorder. 24 The possible explanation for the observed association could be due to either shared environmental determinants among families or the inheritance of some factors that can contribute to the development of HG. 24

Similarly, the previous history of HG was found to have a significant association with HG. This finding was supported by the study conducted in Gamo Gofa, southern Ethiopia, and the study done in Nigeria.4,21 HG has been reported to recur in subsequent pregnancies following an affected one. Appreciating the risk of recurrence enables families to plan for a prolonged period of maternal illness and evidence suggests that preventive measures such as early treatment may reduce the overall severity of the condition and holistic, practical planning of family life around the illness may reduce the bio-psychosocial impacts. 25 However, this finding contradicts a study done in Bale zone, Ethiopia in which no association was seen between HG and previous history of HG. 4 The reason may be due to the difference in the study area and sample size.

Exercise before pregnancy was protective effects on the development of HG when compared to those pregnant women who had no exercise. The finding indicates that exercise before pregnancy can bring a variety of health benefits and women with more frequent exercise before pregnancy had a lower risk of having nausea and vomiting. This consistency comes when some researchers have found that exercise is associated with decreased depression and control of excessive weight gain. 26 So this was supported by a study done at Haramaya, eastern Ethiopia, 27 and that obesity and depression are predictors of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. A previous study also demonstrated that lack of leisure-time physical activity before pregnancy was associated with an increased odd of HG. 28

The strength of this study was that study included six hospitals in different areas, which increases the external validity of the study. The data are primary data that were collected directly from the participant’s strict supervision by the principal investigator and supervisors. Since the study used maternal reports or past exposure, there is a possibility of recall bias and a lack of adequate literature at the country level.

Conclusion

ANC follow-up, number of fetuses, previous and family history of HG, and exercise before pregnancy were significantly associated with HG. Lifestyle modification, early treatment, and early ultrasound scans for a pregnant woman are crucial to reducing the incidence of HG. The healthcare provider should take deep history while first contact with pregnant women on previous and family history of HG and cautiously follow those who had a history of the disease. Providing health education on ANC follow-up is needed to reduce the occurrence of HG. Also enhancing preconception counseling, especially on exercise before pregnancy which is important in weight reduction and improves depression is crucial in reducing the occurrence of HG.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121231196713 for Determinants of hyperemesis gravidarum among pregnant women in public hospitals of Guji, West Guji, and Borana zones, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022 by Demelash Solomon, Geroma Morka and Zelalem Jabessa Wayessa in SAGE Open Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bule Hora University for funding this research and the data collectors and supervisors for their continuous support.

Footnotes

Author contributions: DS, GM, and ZJW have made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published.

Availability of data and materials: The data sets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Consent to participate: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and in the case of women below 18 years of age written consent information was taken from husbands before the study. All respondents were reassured about the confidentiality of their responses. The respondents were told that they have the right to refuse to participate or withdraw at any time from participating in the study will not affect them. The data collectors were trained by the principal investigators on how to keep the confidentiality and anonymity of the responses of the respondents in all aspects.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Bule Hora University (reference no. BHU/PRD/803/13).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Bule Hora University funded this research starting from the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Informed consent: Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC) at Bule Hora University, Institute of Health. A formal letter for permission and support was obtained from Bule Hora University to Guji, West Guji, and Borana zone public hospitals to allow execution of the research then informed voluntary consent will be obtained to recruit the study participants. Finally, data were collected after assuring the confidentiality nature of responses and obtaining written consent from the study participant. All the study participants were encouraged to participate in the study, and at the same time, they were also told that they have the right not to participate.

ORCID iDs: Demelash Solomon  https://orcid.org/0009-0008-5544-0886

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-5544-0886

Zelalem Jabessa Wayessa  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3416-6810

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3416-6810

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. London V, Grube S, Sherer DM, et al. Hyperemesis gravidarum: a review of recent literature. Pharmacology 2017; 100(3–4): 161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castillo MJ, Phillippi JC. Hyperemesis gravidarum. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2015; 29(1): 12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eccles A. Obstetrics and gynaecology in Tudor and Stuart England. London: Routledge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mekonnen AG, Amogne FK, Kassahun CW. Risk factors of hyperemesis gravidarum among pregnant women in Bale zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia: unmatched case-control study. Clin Mother Child Health 2018; 15(300): 2. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Segni H, Ayana D, Jarso H. Prevalence of hyperemesis gravidarum and associated factors among pregnant women at Jimma University medical center, South West Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. EC Gynaecol 2016; 3(5): 376–387. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oudman E, Wijnia JW, Oey M, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy in hyperemesis gravidarum: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019; 236: 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Getahun D, Fassett MJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in children exposed in utero to hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Perinatol 2021; 38(03): 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Türkmen H. The effect of hyperemesis gravidarum on prenatal adaptation and quality of life: a prospective case–control study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2020; 41(4): 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dinberu MT, Mohammed MA, Tekelab T, et al. Burden, risk factors and outcomes of hyperemesis gravidarum in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs): systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2019; 9(4): e025841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maslin K, Dean C. Nutritional consequences and management of Hyperemesis Gravidarum: a narrative review. Nutr Res Rev 2022; 35(2): 308–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Health FMo. Management protocol on selected obstetrics topics. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Office WGH. First quarter performance report, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tefera Z, Assefaw M. Determinants of hyperemesis gravidarum among pregnant women in public hospitals of Mekelle City, North Ethiopia, 2019: unmatched Case-Control Study, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Choi HJ, Bae YJ, Choi JS, et al. Evaluation of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy using the Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis and Nausea scale in Korea. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2018; 61(1): 30–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Padmapriya N, Shen L, Soh S-E, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior patterns before and during pregnancy in a multi-ethnic sample of Asian women in Singapore. Matern Child health J 2015; 19(11): 2523–2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matthews A, Haas DM, O’Mathúna DP, et al. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 2015(9): Cd007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kocalevent R-D, Berg L, Beutel ME, et al. Social support in the general population: standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3). BMC Psychology 2018; 6(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beyene GA. Prevalence of unintended pregnancy and associated factors among pregnant mothers in Jimma town, southwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Contracept Reprod Med 2019; 4(1): 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Golding J. Motion sickness. Handbook of clinical neurology, 2016, vol. 137, pp. 371–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gabra A. Risk factors of hyperemesis gravidarum. Health Sci J 2018; 12(6): 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aminu MB, Alkali M, Audu BM, et al. Prevalence of hyperemesis gravidarum and associated risk factors among pregnant women in a tertiary health facility in Northeast, Nigeria. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2020; 9(9): 3557–3563. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fejzo MS, Myhre R, Colodro-Conde L, et al. Genetic analysis of hyperemesis gravidarum reveals association with intracellular calcium release channel (RYR2). Mol Cell Endocrinol 2017; 439: 308–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laitinen L, Nurmi M, Ellilä P, et al. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: associations with personal history of nausea and affected relatives. Arch Gynecol Obstetr 2020; 302(4): 947–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang Y, Cantor RM, MacGibbon K, et al. Familial aggregation of hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204(3): 230.e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dean CR, Bruin CM, O’Hara ME, et al. The chance of recurrence of hyperemesis gravidarum: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X 2020; 5: 100105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Downs DS, Hausenblas HA. Women’s exercise beliefs and behaviors during their pregnancy and postpartum. J Midwifery & Womens Health 2004; 49(2): 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Obsa M. Prevalence and associated factors of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy among pregnant women in Hararghe health and demographic urveillance system. Eastern Ethiopia: Haramaya University, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Owe KM, Støer N, Wold BH, et al. Leisure-time physical activity before pregnancy and risk of hyperemesis gravidarum: a population-based cohort study. Prev Med 2019; 125: 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121231196713 for Determinants of hyperemesis gravidarum among pregnant women in public hospitals of Guji, West Guji, and Borana zones, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022 by Demelash Solomon, Geroma Morka and Zelalem Jabessa Wayessa in SAGE Open Medicine