Abstract

There are 6 Official Pillars of Lifestyle Medicine, and now mounting evidence supports daily exposure to nature and fresh air as vital to optimizing overall physical and mental health. Time spent in nature has been shown to help lower blood pressure, reduce nervous system arousal, enhance immune system function, reduce anxiety and increase self-esteem. The positive effects of time spent in nature span different occupations, ethnic groups, financial status and individuals with a variety of chronic illnesses and disabilities. “Forest Bathing” is the term coined by Japanese researchers for walking in the woods. It is suspected that aerosols from trees, when inhaled during a forest walk, are one factor responsible for elevated immune system Natural Killer (NK) cells, which help fight off infections and tumor growth. In a culture of ever-increasing technology and screen time, now more than ever it is crucial to educate and empower individuals to incorporate nature into therapeutic treatment regimens. This article will demonstrate the potential benefits of nature, share evidence supporting nature as medicine and provide tools to help engage individuals to spend more time outdoors.

Keywords: nature, healing benefits of nature, forest bathing, Shinrin-Yoku, phytoncides, immune system, biophilia, attention restoration theory, stress recovery theory

“Gardening is a facet of horticulture therapy, and a great way to increase nature exposure while also increasing physical activity and mindfulness.”

Introduction

Nature has been a source of healing and inspiration for humans for thousands of years. From ancient times, people have recognized the restorative power of spending time in nature, whether it is through taking a walk in the woods, listening to the sound of waves crashing on a beach, or simply watching a beautiful sunset. In recent years, research has confirmed what many of us have intuitively known for a long time: that nature has a profound impact on our physical, mental, and emotional well-being. This has led to a growing interest in using nature as a form of medicine, both as a complementary therapy and as a preventative measure. In this context, nature is seen as not only a place of beauty and wonder, but as an essential part of our overall health and wellness. In this article, we will explore the various ways in which nature can be used as medicine, and how we can harness its power to improve our lives.

The concept of nature as medicine is not new, and decades ago Edward O. Wilson was instrumental in raising awareness of our need and desire as a species to connect with the outdoor environment. Wilson, along with Erich Fromm coined the term Biophilia to describe the innate human connection to nature and other living organisms. The word “biophilia” is derived from the Greek words “bios” meaning life, and “philia” meaning love or affinity.

Wilson proposed that human beings have an innate need to connect with nature and other living things, and that this connection is essential to our well-being. This connection can be seen in our appreciation of natural beauty, our love for animals, and our desire to be surrounded by plants and green spaces. The concepts of biophilia and evolutionary biology highlight the connection between humans and the natural world, and present the importance of preserving and nurturing this connection for the benefit of our physical and mental well-being.

In recent years, the concept of biophilia has gained increasing attention from researchers, architects, and urban planners who recognize the importance of incorporating nature into the built environment. This approach, known as biophilic design, seeks to create spaces that promote health, happiness, and productivity by incorporating natural elements such as plants, water features, and natural light into the built environment. Public health officials are also interested in capitalizing on creating natural spaces with the intention to promote health, particularly for vulnerable and disadvantaged populations.

This review will demonstrate that time spent in nature is an essential component of health, and offers practical advice for how clinicians can put this growing body of evidence into practice immediately. The intention of this review is not to provide an exhaustive literature review, but rather to highlight key study findings and conceptual frameworks that provide focused? evidence for the use of Nature As Medicine in clinical practice. excitingly, nature recommendations and nature prescriptions can be integrated into all pillars of Lifestyle Medicine.

Objectives of this review are as follows

• examine changes in lifestyle over the last 70-100 years that have led to sedentary behavior and corresponding epidemics of obesity and chronic disease

• Present how much time we spend indoors and the corresponding detriments of disconnection from the natural world

• Discover the health benefits of time spent in nature, including active ingredients or mechanisms of action, where known

• Identify prevailing theories about the restorative benefits of nature and potential mechanisms of action.

• Learn how to prescribe nature as medicine.

• Provide a clinician toolkit with rich resources to learn more about nature as medicine, as well as practical strategies and tools to help incorporate time spent in nature into your clinical practice, facilitating a clinician’s ability to use shared decision making to craft the perfect nature prescription.

Modern Life Speeds up, While the Human Body Slows Down

The pace of daily life has dramatically increased over the last century. While we’ve seen many positive changes, these rapid shifts have come at a cost. Western societies have become increasingly sedentary, and we spend most of our time indoors, contributing to the rise in obesity and rates of non-communicable diseases, as well as skyrocketing rates of mental health concerns. These phenomena have occurred over a relatively short period of time evolutionarily, particularly in the last 70-100 years. Prior to WWII, the life of the average American included a good deal of physical activity and energy expenditure. Most people were slim, and chronic disease rates were significantly lower than they are today. As the 1940s progressed to the 1950s, more families moved to urban and suburban areas, with modern day conveniences like refrigerators and washing machines. As suburban sprawl advanced, and vehicles became more affordable, people began to commute long distances for work. Additionally, barriers to women working outside the home broke down by the end of WWII and many married women entered the workforce by the 1950s. Computers appeared in homes in the 1980s and the Internet made its debut in the 1990s.

Fast forward to today when smartphones, social media platforms, and working from home is common (enhanced by the COVID-19 pandemic). This has led to increased sedentary behavior, less energy expenditure, and skyrocketing rates of obesity and chronic disease. Despite our modern lifestyle of social media “connection,” we are more disconnected than ever—from each other, from ourselves, and from nature. Our physical, mental, and emotional well-being have suffered greatly.

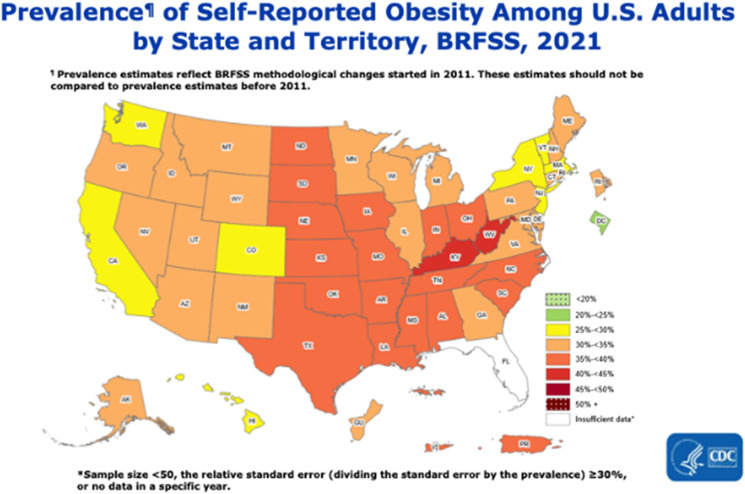

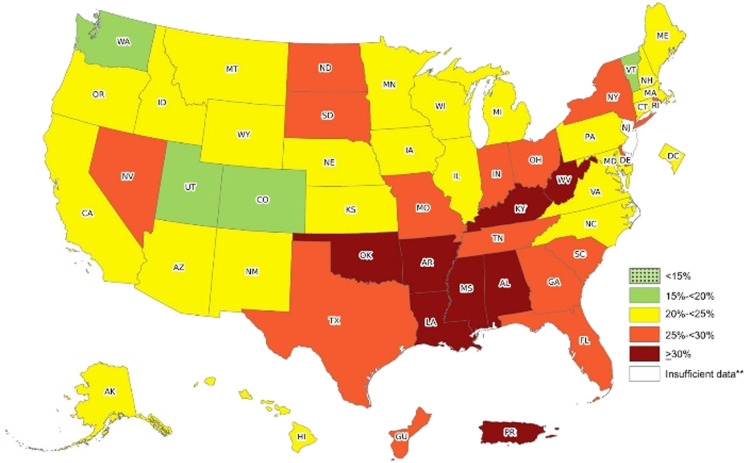

Time Spent Indoors

Americans spend most of their lives indoors, with potentially negative health consequences. According to the EPA, 1 Americans live 90% of their lives indoors. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS), 2 which evaluates exposure to pollutants, including indoor air pollution, determined that Americans live 87% of their lives in buildings and another 6% in vehicles, for a total of 93% of life lived, leaving only 7% of time to spend outdoors. This minute amount of time outdoors may not be intentional, but rather a byproduct of our busy lives. Interestingly, obesity rates and sedentary behavior overlap in the southeastern U.S. while the least obese and most active people live in the western U.S. where the beauty of nature and opportunities to explore it abound (CDC, 2022). Encouraging people to spend more time outdoors in nature has important health benefits, which are explored in more detail below Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of self-reported obesity among US adults by state and territory, BRFSS, 2021. 3

Figure 2.

Prevalence of self-reported physical inactivity* among US adults by state and territory, BRFSS, 2017-2020. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. *Respondents were classified as physically inactive if they responded “no” to the following question: “During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?” ** Sample size <50, the relative standard error (dividing the standard error by the prevalence) ≥30%, or no data in at least 1 year. 4

Theories

Two key theories have emerged that offer explanations for the therapeutic effects of forests and other green spaces 5 :

• Attention restoration theory (ART): Directed (voluntary) attention is depleted by mentally challenging tasks and in urban settings, while exposure to natural environments is restorative. 5

• Stress recovery theory (SRT): Natural settings influence mood, which then promotes recovery from life stressors. 5

Researchers are seeking answers to what it is about nature that promotes and restores human health. Numerous studies have presented evidence related to improvements in both objective health measurements as well as subjective experiences resulting from time spent in nature.

Time spent in nature may include activities with or without an intention of promoting health directly (or specifically). They may be rather passive or very physically active. Elucidating which activities produce the most salient benefits for human health is an emerging field, but we have good data from which we can refine our recommendations. Dr. Qing Li’s studies on shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, in Japan identified key mechanisms that reduce disease risk and promote health. The next section provides additional details on this particular modality of nature exposure and the mounting health benefits of spending time in nature.

Health Benefits of Spending Time in Nature

A burgeoning number of organizations are adopting the term “nature as medicine” in response to a growing body of work demonstrating the multi-faceted power of this modality to influence mood, immune function, cardiovascular health, and much more. Numerous studies demonstrate that immersion in natural environments is linked to multiple positive health effects. Studies including green spaces and forests are the most robust. In fact, all-cause mortality and life expectancy have been consistently linked to the greenness of a neighborhood. 6

A few studies have evaluated “blue spaces” as distinctly beneficial to human health, although data on blue spaces outside of a green space (setting) is still emerging. a green space is still emerging. One systematic review looking at well-being and blue spaces found mental health, particularly psycho-social well-being, can be enhanced by blue spaces. 7 Another systematic review and meta-analysis 8 sought to quantify the blue space mechanisms. There appear to be three key pathways including, 1) promotion of physical activity, 2) increased restoration, and 3) improved air quality. Positive impacts of blue space are harmonious with findings for green spaces, and represent public health resources for addressing risk factors linked to increased urbanization. There is a paucity of data for brown spaces like deserts and snow covered areas.

Benefits of spending time in nature are numerous, and health outcomes identified to date include the following 6 :

• Immune function - improved natural killer (NK) cell activity, increased cancer fighting protein production and less cancer, less acute urinary tract infection and upper respiratory infection, and improved healing ability

• Cardiovascular - lower blood pressure, lower heart rate, increased heart rate variability

• Endocrine - improved blood glucose control, lower cortisol levels

• Brain/Neurologic health - better cognitive performance, less migraine

• Nervous system - less sympathetic and more parasympathetic activity/less activity within the amygdala.

• Mental and emotional health - improved mood, less anxiety and depression, improved symptoms of ADHD, and improved overall well-being

• Intestinal health - more short chain fatty acid producing bacteria

• Musculoskeletal - less MSK complaints

• Positive impacts on birth weight

What might the mechanism(s) of action or active ingredients be to cause such profound, positive effects on human health? A mini-review 6 identified 21 potential pathways, with results pointing to enhanced immune function as a possible central pathway, although there may be others. The review concludes that “nature actually promotes health,” with a symphony of multiple contributing pathways creating a large aggregate effect, though any one pathway may exert a small-scale effect. 6

A review and meta-analysis of health outcomes linked to exposure to greenspace, 9 drevealed a significant body of work dating to the 1800s, and nearly 150 studies identifying broad health benefits from greenspace exposure. Statistically significant reductions in heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and salivary cortisol, diabetes, cardiovascular, heart rate variability, HDL cholesterol, self-reported health, and all-cause mortality, suggest that greenspace is linked to a significant range of health benefits. These findings advance greenspace as an intervention for bettering a breadth of health outcomes.

Does the type of greenspace matter? While most studies compare the effects of forested vs urban spaces, one study, 10 set forth with a randomized cross-over trial to determine if there is a difference between forest and field. The results showed each led to improvements in emotional well-being, however, vitality was stronger for forest vs field.

Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing)

Shinrin-yoku is a Japanese term meaning “forest bathing” or “taking in the forest atmosphere.” This practice involves spending time in a forest or other natural environment to improve one’s physical, mental, and emotional well-being. With roots in the early 1980s, Shinrin-Yoku was developed by the Japanese government’s forestry agency as part of a national public health campaign to promote better national health and well-being.

Shinrin-yoku gained popularity in Japan, and the government began promoting it as a form of preventive healthcare and therapy. Today, Shinrin-yoku is well-established in Japan and has gained popularity around the world as a way to improve overall health and well-being. The practice involves immersing oneself in a forest or other natural environment, taking in the sights, sounds, and smells, and engaging all the senses.

National and international forest therapy projects include, Forest Therapy Society of Japan, 11 European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) Action-E39 Project on Forests, Trees and Human Health and Well-being, 12 and International Society of Nature and Forest Medicine. 13 Studies suggest Shinrin-yoku has a range of health benefits, including reducing stress, boosting the immune system, and improving mood and cognitive function. These are addressed in more detail below. Benefits of shinrin-yoku are many:

1. Reduced stress and activity in the amygdala: Various studies, as well as data from meta-analyses, have presented findings that forest bathing reduces blood pressure and the stress hormone, cortisol. Other benefits include relaxation, decreased heart rate, improved positive feelings and lower negative feelings, and a re-balancing of the nervous system by decreasing sympathetic activity and increasing parasympathetic activity.14-17 The amygdala is the part of the brain involved in processing emotions, particularly fear and anxiety. A one-hour walk in nature decreased amygdala activation vs no change with a walk in an urban area. 18 In a 2019 systematic review, Norwood et al found that urban environments seem to induce an overactive amygdala vs natural environments inducing lower levels of activity.

2. Boosted immune system: A number of studies have demonstrated positive effects on immune function lasting from 7 to 30 days post-exposure for natural killer (NK) cells and others central to immune defense against cancer and viruses.14,17,19,20 The total effect of the sights, smells, fresh air, quiet of the forest, plus numerous organic tree compounds called phytoncides create these effects. 21

3. Non-communicable diseases: Multiple mechanisms help reduce risk of chronic diseases, with evidence for lowering heart rate and blood pressure, type 2 diabetes with lowering blood sugar, and stress reduction 17

4. Covid-19: By boosting immune function and lowering stress, Shinrin-yoku may reduce mortality and severity in COVID-19. 17

5. Mental health and addiction: Forest bathing has a powerful impact on mental health. Examples include, significantly elevated serotonin levels, increased measures of vigor, reduced fatigue, improved sleep. 17 With reductions in negativity, rumination, and anxiety, nature exposure is accomplishing “negative affect repair.” 22 A systematic review and meta-analysis, 23 determined Shinrin-yoku was a means for reducing anxiety, anger, depression, and stress. And because addictions are also linked to anxiety, depression, and stress, the authors suggest Shinrin-yoku may also be an effective treatment tool for addiction.

6. Healthcare worker burnout: Spending time in nature, with its ability to heal, is “just the prescription we need” for addressing burnout as a national priority per the Surgeon General. 24 The authors relate this to key effects noted above, along with the development of feelings of connectedness, helpfulness, and generosity, through nature’s power to invoke “transcendent wonder and amazement.”

7. Sub-Health: Interestingly, 25 this health category lies between the states of health and disease, and shows up in symptoms such as poor sleep, forgetfulness, chronic pain, and fatigue, and is affecting a growing number of individuals studied in Japan and Western Nations. The antidote of forest bathing heals through a “five senses experience” with even greater benefits from doing meditation or physical activity in the forest setting.

Phytoncides

The power of phytoncides was best elucidated from Dr. Qing Li’s research on forest bathing. This is one of many potential mechanisms of action when it comes to the health benefits of forest bathing. Phytoncides are natural volatile compounds emitted by trees and plants as a form of self-defense against insects and other harmful organisms. These substances are also responsible for the distinct smell of the forest or other natural environments. Phytoncides have been found to have a range of health benefits for humans, including reducing stress and boosting the immune system, and are thought to be one of the reasons for the benefits of shinrin-yoku and time in nature. In a study with Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica), volatile compounds such as D-limonene and alpha-pinene improved sleep, anxiety, and discomfort, 26 while inhaled limonene and pinene have been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects. 27

Prescribing Nature as Medicine

Understanding the benefits of time spent in nature is one thing, but prescribing it is another. Prescribing nature as medicine means to prescribe interventions that involve exposure to nature as a way to promote health and well-being. As scientific evidence of the healing benefits of time in nature emerged in the literature, there was a corresponding interest in what the correct “dose” might be. Medical providers are comfortable with the standard method of writing prescriptions that include the name of medication, dose, route, frequency, and length of time. It makes sense that to put nature as medicine into practice, we identify the elements of an evidence-based nature prescription.

The concept is rather nuanced, but a study from 2019 titled Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and well-being 28 found a minimum effective dose to be an accumulation of 120 minutes a week with an optimal dose of 200-300 minutes a week for best overall effects on mental health measures. Another 2019 study, Urban Nature Experiences Reduce Stress in the Context of Daily Life Based on Salivary Biomarkers, 29 found the largest decrease in salivary cortisol between 21-30 minutes in nature. Although other studies have hinted at the “correct” nature dose, these two studies support the recommendation for time spent in nature to be 20-30 minute minimum intervals with an accumulation of at least 120 minutes every week. When combined with exercise, the benefits are amplified.

Although this recommendation may be refined over time, it’s a wonderful evidence-based starting point. In order to provide individualized prescriptions based on a particular patient or client, several factors must be considered. For example, accessibility to safe natural spaces, transportation (if needed), patient or client buy-in, willingness to engage with this kind of prescription, and potential partners for accountability are all important in collaboratively crafting the best nature prescription for any given patient. It may be helpful to elicit any positive childhood experiences in nature that can inform the current prescription.

Nature Pyramid - A Global Model for Prescribing Nature Time

The Nature Pyramid, a project of The Nature of Cities, 30 is a tool designed to serve as a guide to the types and amounts of exposure to nature. Developed by Tim Beatley and Tanya Denckla-Cobb at the University of Virginia, The Nature Pyramid examines the types of nature important for a healthy life, envisioned as similar to a nutrition pyramid and creating a vision of servings of nature nutrients. It may be a helpful visual to help patients conceptualize various nature experiences. Additional research underway is The Biophilic Cities Project at the University of Virginia.

At the base of the Nature Pyramid are nature experiences which form the preponderance of daily nature experiences. These include being outdoors at least part of each day, walking, sitting, strolling, etc. Ascending toward the top of the pyramid is an escalation in frequency (daily, weekly, monthly, yearly) and corresponds with encouraging visits to larger and more remote natural areas and parks. At the top are profound nature experiences, places of immersion, intensity and length of the nature experience can be greater.

Potential Risks of Prescribing Nature as Medicine

Clinicians must weigh the risks and benefits of any intervention, including nature prescriptions. This article has explored many benefits, but are there any risks associated with using nature as medicine? Potential risks may include the following:

1. Safety: Exposure to certain natural environments can pose risks associated with exposure to weather, wildlife, or uneven landscapes that pose risk of physical injury.

2. Allergies: Some individuals may have allergies that limit their ability to spend time in certain natural environments or pose a risk of an anaphylaxis reaction, as in the case of bee stings (for those allergic to bee venom). Carrying an epi-pen may be a recommendation for this group of people.

3. Other health concerns: Individuals with significant phobias related to being in nature may need to utilize more passive nature interactions. See the toolkit below for some ideas.

4. Lack of efficacy: While there is strong evidence to support the health benefits of nature exposure, not all individuals may experience the same benefits.

Overall, prescriptions for nature as medicine have the potential to provide significant health benefits with relatively low risk. Even still, it’s important for healthcare providers to weigh the potential benefits against the potential risks before prescribing or participating in nature-based interventions.

Barriers to Prescribing Nature as Medicine

In the process of assessing for and prescribing nature as medicine, clinicians will likely encounter patients presenting with a wide range of challenges and barriers on the journey to change.

Examples include, a patient's lack of time or finances, fear of falling or getting injured, general safety concerns (i.e., unsafe neighborhoods), body image concerns, the weather is “bad,” lack of enjoyment, lack of access to a safe natural environment, lack of a companion, feeling too tired, and even a lack of motivation. It is imperative to understand these barriers for each individual in order to help them craft and customize a plan that works for them. SMART goal creation can be helpful here. Identifying ways to support their efforts and keep them accountable will increase their success and enable them to re-engage after having a setback. As noted below, ParkRx America enables the prescriber to sent patients automated reminders to spend time in nature, via text or email. to automatically send patients reminders via text or email.

Cost may also emerge as a barrier to using a nature prescription. Individuals may need to take time away from work or other obligations, there may be travel costs, or entrance fees. Canada’s PaRx is outlined in the toolkit, and nature prescriptions written through this platform may provide free park passes (Canada only).

Looking to the Future of Nature as Medicine

With the explosion of interest in the healing benefits of nature in the last few decades, we now have many studies to inform evidence-based clinical practice. Data related to the healing benefits of nature (and greenspaces in particular), what constitutes greenspaces, recommended exposure time in nature, and potential mechanisms of action are relatively well illunimated but continue to emerge. With a little creativity, enhanced by time spent in nature, a clinician can find ways to incorporate nature as medicine into all pillars of LM. Here are some suggestions:

• Whole Food Plant Based Nutrition - cultivate a garden and grow one’s own herbs, vegetables, and fruits.

• Exercise - walk, hike, bike, garden, play outside

• Stress Management - mindful time in nature improves mood and attention, and lowers anxiety and depression. Mindful activities can be passive, like journaling while outside or laying on the ground, or more active like a walking meditation or bike ride.

• Risky Substances - time spent in nature reduces stress and may even reduce risk of engaging in risky behaviors. 31

• Sleep - early morning exposure to natural light improves circadian rhythms and promotes earlier sleep onset. Early morning natural light exposure (outside) in combination with physical activity may further improve sleep quality and quantity.

• Social connection - reconnection with nature not only improves connection to self, but also connection to other living beings including plants, animals, and even planet Earth. Garden clubs, hiking with friends and family, taking your dog for a run, and more bring people together which we know has beneficial effects on health.

Although many benefits exist connecting time in nature to human health, many more questions remain unanswered and exciting areas of opportunity exist to reveal additional benefits. this seems redundant with the prior sentence and thought For instance, there is not yet a consistent definition of “nature” in research studies, measurement methods are lacking, mechanistic pathways are not fully understood, potential harms or contraindications have not been fully identified, the best biometrics or health outcomes to track that reflect nature exposure benefits is not fully known, a validated tool for clinical assessment does not exist currently, and there have only been hints at potential critical time periods for nature exposure across the lifespan (i.e., childhood). 32

Despite the gaps in scientific evidence, the landscape is rich with opportunities to illuminate the many facets of nature as medicine well into the future. For example, the most reliable and valid tool(s) to evaluate nature exposure at the point of care. The health benefits and mechanisms of action related to exposure to blue spaces, or beach areas more specifically, and even brown spaces like deserts. Use of virtual reality holds promise in a few studies, although the impact may not be as strong as actual nature exposure. 33

Other exciting ideas include community planning with priority given to nature exposure for human health, reaching vulnerable and historically marginalized populations, those in low income or unsafe neighborhoods, impact across the lifespan including young children and the elderly, and even ways confined people (those in windowless workspaces or solitary confinement in prisons) can take advantage of nature exposure.

Lastly, learning the best ways to leverage technology will be critical in the coming years which may include tracking time spent in nature and identifying the best biometrics to obtain, like heart rate, blood pressure, HRV, and blood markers. Artificial intelligence may even be able to help us identify what activities in nature produce the best health outcomes.

Nature As Medicine - A Clinician’s Toolkit

Many amazing resources exist for clinicians to incorporate nature as medicine into clinical practice. Those presented here are intended to help clinicians integrate nature into their own lives? on a daily basis as well as tools and strategies to help patients do the same. This is not an exhaustive list, but will help guide health professionals on personal and professional journeys of using nature as medicine. personal and professional journey of using nature as medicine. Combining movement with time in nature may have synergistic benefits. Keep in mind the current exercise and nature dose recommendations:

A. Exercise - 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity cardiovascular exercise plus strength training, two days a week, with 1-2 day rest periods for any given muscle group.

B. Nature - accumulation of 120 minutes per week of time in natural green spaces, ideally with a minimum of 20 minute intervals.

A 30 minute brisk morning walk in nature without sunglasses will provide cardiovascular exercise, exposure to the healing benefits of nature, and even improve sleep via exercise as well as setting the master circadian clock in the brain. Bonus points for adding a mindful minute such as noticing the beauty in a single leaf or petal, or the 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 grounding technique described below.

The following list invites clinicians to learn more about nature as medicine and provides practical tools and strategies to engage patients and clients.

1. Consider the physical space of the clinic as an opportunity to bring nature into one’s practice. Per the recommendations of Pediatrician Nooshin Ranza, MD of UCSF, display nature images on the walls of one’s clinic that reflect local spaces. Name each exam room after a local natural area or park, and hang maps of that area inside the corresponding room (credit to Dr. Razani via her 2017 TEDxNashville talk, “Prescribing Nature for Health” - https://youtu.be/0uk0QriYYws). Clinicians can also create a living wall or bring green plants into a workspace, while being mindful of potential allergens.

- 2. Screen for time in nature. Although a validated tool is currently lacking, here are a few ideas for screening patients for time spent in nature.

- a. Availability: Do you have safe access to nature/natural areas (green spaces in particular) where you enjoy spending time? are these easily accessible by foot, bike, car?

- b. Duration: How long did you spend there in the past week, or want to spend there every week?

- c. Frequency: How often did you go there (or a similar space) in the past year?

- d. Activity: What did you do or like to do while in that space? Were you exercising, physically active or resting and relaxing?

- e. Intensity/Quality: What is the size and quality of that area? (i.e., an overgrown empty lot in an inner city is very different then a large botanical garden)

3. The Nature Pyramid provides a framework for discussing time in nature, and suggests activities including time and frequency for those activities. For example, a daily 20 minute walk outside vs an annual camping trip. Additional commentary and related images can be found at: https://www.biophiliccities.org/the-nature-pyramid. The authors? particularly like the version from the Nature Kids Institute. Commentary and image can be found here: https://www.ecopsychology.org/gatherings/the-nature-kids-institute.

- 4. Encourage tracking time in nature with APPS such as NatureDose (https://www.naturequant.com/naturedose) or NatureTime (https://naturetimeapp.com). Other apps can help healthcare professionals motivate patients and increase their time spent in nature. Consider these:

- a. NaturePacer

- b. Forest

- c. Happy Hike

- d. Nature Passport

- e. Hiking Project

- f. All Trails

- g. iNaturalist

5. Encourage tracking physical activity with a wearable device that includes step count, heart rate, and even heart rate variability (HRV) data (higher variability reflects better nervous system and emotional regulation and is often a sign of improved mood and robust resilience) like the WHOOP band, Oura ring, Garmin Forerunner 255, Fitbit Series 3, and the Apple Watch Series 8. (https://www.mindbodygreen.com/articles/best-hrv-monitor; Heart Math Interventions Program training - www.heartmath.com)

- 6. Prescribe Nature with ParkRx America, ParkRx, or PaRx. Details and benefits are found in Table 1.

- a. ParkRx America (U.S.) is an Exercise is Medicine (EIM) partner. https://parkrxamerica.org.

- b. ParkRx (U.S.) includes 4 toolkits, 1 specifically for clinicians. https://www.parkrx.org & https://www.parkrx.org/parkrx/clinical

- c. PaRx (Canada) - https://www.parkprescriptions.ca

Table 1.

Comparison of Park Rx, Park Rx America and PaRx.

| Park Rx (U.S.) | Park Rx America (U.S.) | PaRx (Canada) |

|---|---|---|

| https://www.parkrx.org Born in San Francisco, CA, Managed by The Institute of the Golden Gate | https://parkrxamerica.org Born out of DC Park Rx in Washington, DC. Dr Robert Zarr | https://www.parkprescriptions.ca Born in British Columbia, Canada. Dr Melissa Lem, PaRx Director |

| ParkRx is a collaboration with the US National Parks. In 2013, “The Institute at the Golden Gate and the National Recreation and Parks Association, with support from the National Park Service, convened a group of practitioners to discuss the emerging trend of prescribing nature to improve mental and physical health. This group developed the National ParkRx Initiative with the goal of supporting the emerging community of Park Prescription practitioners. ParkRx.org began as the home for the National ParkRx Initiative and has grown into the leading information hub for Park Prescriptions, creating a space for knowledge sharing in the practitioner community.” | “We at PRA (Park Rx America) believe that nature-rich areas should be accessible to all, and incorporated into our daily routines. Spending time in and around nature is the single most important first-step to improving both human and planetary health. PRA is committed to educating healthcare professionals and the public, and to providing the tools to meet each individual’s unique needs. We know that there is a preponderance of evidence that incorporating more nature into our lives improves our physical and mental health and social well-being, AND that nature prescriptions increase our patient’s likelihood of spending more time in nature.” | PaRx is an initiative of the BC Parks Foundation, driven by healthcare professionals who want to improve their patients’ health by connecting them to nature. Featuring practical resources like quick tips and patient handouts, its goal is to make prescribing time in nature simple, fun and effective |

| Each prescriber who registerswith PaRx will receive a nature prescription file customized with a unique provider code, and instructions for how to prescribe and log nature prescriptions. Patients can also access special offers from our proud partners to reduce their barriers to nature access across Canada. | ||

| They provide a “Park Prescription Program Toolkit”—a step by step guide to starting a Park Prescription Program. The 4 toolkits are Clinician, Public Health, Community, and Parks. The Clinician toolkit has a “Healthy Parks, Healthy People” guide for healthcare providers, surveys, patient facing assets, and various how-to videos | Providers can sign up with their NPI number and create individualized nature prescriptions, with nice prompts to guide you in crafting the most appropriate prescription. Not only that, but patients can “check in” as a way to log their activity, which you can then see on their profile. This way you will know if and when they “filled” their Rx! | |

| BEST for creating a robust Nature Rx program and engaging local agencies, community partners, and more | BEST for providers to learn more and write individualized Nature prescriptions, prompted by all the right questions to ask at the time of writing. Great for patients to learn more as well | BEST for providers to learn more and provide a FREE Canadian park pass |

| This platform seems to be the most robust for engaging local communities and stakeholders | This platform seems to be the most robust for both providers and patients |

Here are additional ideas to bring nature as medicine to life.

- 1. Many nature-based therapies and techniques exist. Here are a few to explore:

- • 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 Grounding Technique combines time in nature with movement and mindfulness. It’s also good for coming into present moment awareness. Identify 5 things you see, 4 things you can touch, 3 things you hear, 2 things you smell, and 1 thing you can (safely) taste.

- • Encourage “sit-spots.” Find a comfortable, safe place outside to just sit and notice for 5-15 minutes. Focus on the senses (similar to the grounding exercise above). Other ideas for the sit-spot include closing the eyes and taking deep belly breaths, listening to sounds near and far, feeling the temperature of the air or the wind against your skin, gazing upon a single leaf, petal, or rock and noticing all the beauty in that 1 item.

- • Gardening is a facet of horticulture therapy, and a great way to increase nature exposure while also increasing physical activity and mindfulness.

- • Explore the idea of nature therapy walks and recommend regular walks in natural environments and even identify guides in your area. The Association of Nature and Forest Therapy provides training as well as a directory of certified guides (https://www.natureandforesttherapy.earth/guides).

- • If accessible, consider forest therapy, also known as Shinrin-yoku, which involves spending time in forests and other natural environments as a way to reduce stress and improve well-being.

- • Wilderness Therapy involves immersive outdoor experiences with the intention of promoting personal growth and well-being and may include activities such as camping or hiking.

- • Mindful practices, of which there are many, done outside in nature may provide exponential benefit. In ancient times, spiritual leaders faced with challenges would travel to meditate in nature, seeking wisdom and well-being. This history along with more recent scientific studies suggest a compounding relationship of combining these modalities. Olson, et al (2020) suggests 34 that while both forest bathing and mindfulness (individually) are scientifically shown to improve positive emotional and neurobiological reactions, larger effects may result when utilized together.

2. Encourage visits to national parks (U.S.) with the National Parks Pass. It is FREE for Gold Star Military personnel, fourth graders, those with medical disabilities, and offers low cost lifetime membership for those over 62 years of age.

3. Listen to science-based nature as medicine podcasts, like the Nature of WellnessTM Podcast.

4. Connect with your local park system to collaborate on ideas and to discuss the possibility of regular outings for purposes of health restoration. Park Rx (https://www.parkrx.org) provides support to build relationships with local parks and important stakeholders.

5. Start a Walk with a Doc group (https://walkwithadoc.org). This is one of two nationwide Park Rx programs and 1 of the only global programs bringing patients outside to move naturally. It was started in 2005 by Dr. David Sabgir—a cardiologist in Columbus, OH, and it’s a great way to bring Lifestyle Medicine to life. For a small fee, they help you set up the legal documents, guidance, and promotional materials to get started.

- 6. Engage the senses to connect with nature for health purposes.

- • SIGHT - If you or your patients cannot get out in nature, there is evidence that just viewing nature scenes is beneficial (Ulrich, 1984). This includes looking out a window onto a real nature area or even just viewing an image of nature (digital, mural, photograph, VR, etc.). When barriers exist in accessing nature, virtual reality (VR) forest bathing may be an option. In a study by 5 a virtual forest walk is able to improve well-being. Although there are more reasons to walk in the forest, VR nature walks offer a useful substitute if needed.

- • SOUND - Several scientific studies found listening to bird songs beneficial.34,35 identified superior outcomes in cognitively demanding tasks, in those exposed to nature, proposing that nature sounds reduce demands on the endogenous attention system, thereby helping to restore “directed attention.” Recommend (or create) a playlist of birds or other nature sounds on a listening platform like Spotify. Here are a couple albums to get you started: “Bird sounds in the nature” and “Birdsong” (https://open.spotify.com/album/4M2MhCigUU3C2lsZrgycTO?si=BaxS-1FHRK-31I7mb9IghA and https://open.spotify.com/album/6oBplVm5XkZ4NRKtMe6pmT?si=SzW6_B2OR52uqGeVV-THLQ).

- • SMELL - According to Dr. Qing Li, 35 forest bathing researcher in Japan, even smelling high quality essential oils of trees that contain phytoncides such as pine, cedar, spruce, and fir may be helpful. It’s plausible that other nature smells, like the Petrichor smell after a rain, may be soothing as well.

7. Many authors have written books about nature, our connection to (and disconnection from) nature, and the healing benefits of nature. Authors to explore include Richard Louv, Florence Williams, Dr. Qing Li, Bart Foster, Jeffrey Davis, EO Wilson, and Rachel Carson. See Table 2 for details.

Table 2.

Suggested books about nature and nature as medicine.

| AUTHOR | BOOK Title | About |

|---|---|---|

| Dr Qing Li (1962-) | Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health & Happiness (2018) | The ultimate guide to the Japanese practice of Shinrin-Yoku. Dr Li conducted research that enhances our understanding of nature as medicine |

| Richard Louv (1949-) | Last Child in the Woods - Saving our children from nature deficit disorder (2008) | This is Richard Louv’s landmark book bringing to light how disconnection from nature is impacting our children. It sparked a global movement, informed policy, and was a serious call to action. Some say it’s the most important book since Silent Spring |

| The Nature Principle - Reconnecting with Life in a Virtual Age (2012) | The Nature Principle is Mr. Louv’s call to action, this time for adults | |

| Vitamin N - The Essential Guide to a Nature-Rich Life (2016) | Vitamin N is an inspiring, comprehensive and practical guidebook to connect anyone with nature including individuals, families, communities and stakeholders. https://richardlouv.com | |

| Florence Williams (1967-) | The Nature Fix - Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative (2018) | Prize-winning journalist and author investigates nature’s restorative benefits. She travels the world to uncover nature’s health benefits. http://www.florencewilliams.com/the-nature-fix |

| Jeffrey Davis | Tracking Wonder - Reclaiming a Life of Meaning and Possibility in a World Obsessed with Productivity (2021) | This book will help you change how you see life and understand how to use the six facets of wonder to live a miraculous life. https://trackingwonder.com |

| Bart Foster | Business Outside: Discover Your Path Forward (2022) | Founder, trail guide, and facilitator. This book “reimagines corporate culture by bringing business outside comfort zones, antiquated corporate norms, and into nature, allowing for increased creativity, meaningful connections, and psychological restoration.” https://bart-foster.com |

| Edward O. Wilson (1929-2021) | Biophilia (1984) | E. O. Wilson was an American biologist, authority on ants, and known as the father of biodiversity. He was University Research Professor Emeritus at Harvard, with a long career in biodiversity and author of numerous books about nature, biodiversity, and planetary health. He won a Pulitzer Prize twice. https://eowilsonfoundation.org |

| Half-Earth - Our Planet’s Fight for Life (2017) | ||

| The Diversity of Life (2001) (. . . and many others) | ||

| Rachel Carson (1907-1964) | Silent Spring (1962) | A marine biologist and nature writer who sparked a global environmental movement, bringing the detriments of pesticides like DDT to the population’s awareness which ultimately led to a nationwide ban on the substance. A landmark nature and environment book, written during her own battle with cancer. https://www.rachelcarson.org |

| Donald A. Rakow and Gregory T. Eells | Nature Rx: Improving College-Student Mental Health (2019) | A book outlining the mental health crisis on US campuses, benefits of time in nature, developing a campus wide Nature Rx program, and presenting university level nature programs on 4 flagship campuses (Cornell, UC Davis, William and Mary, and University of Minnesota) |

Conclusion

Nature has been a source of healing and inspiration for humans for thousands of years. Since ancient times, human beings have sought out the restorative power of time in nature, and now fast forward to the 21st century, modern medicine and rigorous scientific studies are validating both the power and the need for human contact with natural settings. This should not be surprising, first and foremost because humans are part of nature. Our non-human relatives spend all of their time in nature and are part of the fabric of life and our experience of nature. In contrast, studies show Americans spend 90% or more of their time inside human fabricated constructs, primarily buildings and vehicles. So where do we go from here?

It will be helpful to create a framework for practicing nature as medicine which includes, exploring and expanding knowledge about using nature as a therapeutic modality, assessing nature exposure in clients and patients, prescribing evidence-based strategies for spending time in nature, and committing to building a toolkit from which you can personalize your own practice that capitalizes on the healing aspects of nature. Consider experimenting with fitness and nature trackers, nature prescriptions, or how time spent in nature enhances patients’ health and minimizes chronic conditions in your own clinic. Record interesting case studies and share your own experiences with family, friends, clients, and patients.

The authors’ hope is that the idea of nature as medicine has piqued your interest, sparked your curiosity, and provided enough evidence and tools for you and your patients alike to reconnect with nature for improved physical, mental, and emotional health, and overall well-being. The sky’s the limit!

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.EPA . Indoor air quality: What are the trends in indoor air quality and their effects on human health? EPA. 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/report-environment/indoor-air-quality. Accessed April 2, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klepeis N, Nelson WC, Ott W, et al. The national human activity pattern survey (NHAPS): A resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2001;11(3):231-252. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps. 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html. Accessed April 29, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Adult Physical Inactivity Prevalence Maps by Race/ethnicity. 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/inactivity-prevalence-maps/index.html. Accessed April 29, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reese G, Stahlberg J, Menzel C. Digital Shinrin-Yoku: Do nature experiences in virtual reality reduce stress and increase well-being as strongly as similar experiences in a physical forest? Virtual Real. 2022;26(3):1245-1255. doi: 10.1007/s10055-022-00631-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo M. How might contact with nature promote human health? promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1093, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Britton E, Kindermann G, Domegan C, Carlin C. Blue care: A systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promot Int. 2020;35(1):50-69. doi: 10.1093/heapro/day103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georgiou M, Morison G, Smith N, Tieges Z, Chastin S. Mechanisms of impact of blue spaces on human health: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18(5):2486. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Twohig-Bennett C, Jones A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ Res 2018;166:628-637. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oomen-Welke K, Schlachter E, Hilbich T, et al. Spending time in the forest or the field: Investigations on stress perception and psychological well-being—a randomized cross-over trial in highly sensitive persons. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;19(22):15322. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192215322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forest Therapy Society - Official Website. 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.fo-society.jp/en/. Accessed April 9, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 12.COST . Cost news. COST. 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.cost.eu/actions/E39/. Accessed April 9, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Society of Nature and Forest Medicine . INFOM. 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.infom.org/. Accessed April 9, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antonelli M, Barbieri G, Donelli D. Effects of forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku) on levels of cortisol as a stress biomarker: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Biometeorol. 2019;63(8):1117-1134. doi: 10.1007/s00484-019-01717-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park BJ, Tsunetsugu Y, Kasetani T, Kagawa T, Miyazaki Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 Forests across Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2010;15(1):18-26. doi: 10.1007/s12199-009-0086-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Park B-J, Tsunetsugu Y, Ohira T, Kagawa T, Miyazaki Y. Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Publ Health. 2011;125(2):93-100. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Ochiai H, Ochiai T, et al. Effects of forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku) on serotonin in serum, depressive symptoms and subjective sleep quality in middle-aged males. Environ Health Prev Med. 2022;27:44-44. doi: 10.1265/ehpm.22-00136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sudimac S, Sale V, Kühn S. How nature nurtures: Amygdala activity decreases as the result of a one-hour walk in nature. Molecular Psychiatry. 2022;27:4446-4452. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/tucy7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q, Morimoto K, Nakadai A, et al. Forest bathing enhances human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2007;20(2_suppl l):3-8. doi: 10.1177/03946320070200s202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q. Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environ Health Prev Med. 2010;15(1):9-17. doi: 10.1007/s12199-008-0068-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q, Kobayashi M, Wakayama Y. Effect of phytoncide from trees on human natural killer cell function. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. Int J Biometeorol. 2019;63(8):1117-1134. doi: 10.1177/039463200902200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bratman GN, Daily GC, Levy BJ, Gross JJ. The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landsc Urban Plann. 2015;138:41-50. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotera Y, Richardson M, Sheffield D. Effects of shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy on mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2020;20(1):337-361. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00363-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhing W, Tannenbaum L. Getting back to nature: Healing the mind, body, and spirit of healthcare workers. J Interprofessional Educ Pract. 2022;29:100583. doi: 10.1016/j.xjep.2022.100583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen Y, Yan Q, Pan Y, Gu X, Liu Y. Medical empirical research on forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku): A systematic review. Environ Health Prev Med. 2019;24(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12199-019-0822-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng W-W, Lin C-T, Chu F-H, Chang S-T, Wang S-Y. Neuropharmacological activities of phytoncide released from Cryptomeria japonica. J Wood Sci. 2009;55(1):27-31. doi: 10.1007/s10086-008-0984-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonelli M, Donelli D, Barbieri G, Valussi M, Maggini V, Firenzuoli F. Forest volatile organic compounds and their effects on human health: A state-of-the-art review. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(18):6506. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White MP, Alcock I, Grellier J, et al. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and Wellbeing. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7730. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44097-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter MR, Gillespie BW, Chen SY-P. Urban nature experiences reduce stress in the context of daily life based on salivary biomarkers. Front Psychol 2019;10:722, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knapp J, Says DK, Says H, et al. Exploring the nature pyramid the nature of Cities. 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2012/08/07/exploring-the-nature-pyramid/. Accessed April 7, 2023.

- 31.Townsend MM, Pryor C, Field A. Health and well-being naturally: “Contact with nature” in Health promotion for targeted individuals, communities, and populations. Research Gate. 2006. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6872228_Health_and_well-being_naturally_'Contact_with_nature'_in_health_promotion_for_targeted_individuals_communities_and_populations. Accessed April 6, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holland I, DeVille NV, Browning MH, et al. Measuring nature contact: A narrative review. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18(8):4092. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White MP, Yeo N, Vassiljev P, et al. A prescription for “nature” - the potential of using virtual nature in therapeutics. Neuropsychiatric Dis Treat. 2018;14:3001-3013. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s179038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olson ERT, Hansen MM, Vermeesch A. Mindfulness and Shinrin-Yoku: Potential for physiological and psychological interventions during uncertain times. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(24):9340. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Hedger SC, Nusbaum H, Clohisy L, Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Berman M. Of cricket chirps and car horns: The effect of nature sounds on cognitive performance. Psychon Bull Rev. 2018;26(2):522-530. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/f5hcz [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]