Abstract

We used broad-range bacterial PCR combined with DNA sequencing to examine prospectively cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from patients with suspected meningitis. Fifty-six CSF samples from 46 patients were studied during the year 1995. Genes coding for bacterial 16S and/or 23S rRNA genes could be amplified from the CSF samples from five patients with a clinical picture consistent with acute bacterial meningitis. For these patients, the sequenced PCR product shared 98.3 to 100% homology with the Neisseria meningitidis sequence. For one patient, the diagnosis was initially made by PCR alone. Of the remaining 51 CSF samples, for 50 (98.0%) samples the negative PCR findings were in accordance with the negative findings by bacterial culture and Gram staining, as well as with the eventual clinical diagnosis for the patient. However, the PCR test failed to detect the bacterial rRNA gene in one CSF sample, the culture of which yielded Listeria monocytogenes. These results invite new research efforts to be focused on the application of PCR with broad-range bacterial primers to improve the etiologic diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. In a clinical setting, Gram staining and bacterial culture still remain the cornerstones of diagnosis.

Bacterial meningitis is usually suspected on the basis of the clinical presentation of the patient and the finding of purulence in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The diagnosis is subsequently confirmed by microscopic detection and/or culture of the microbe from the CSF. After antimicrobial treatment is started, the rate of isolation of bacteria is, however, strikingly reduced (2). The cultures may also remain negative if the disease is caused by fastidious and slowly growing microorganisms. In these situations molecular diagnostic methods, including PCR, may be of help in providing the etiologic diagnosis.

In recent years, PCR techniques have increasingly been used to amplify and detect microbial DNA in clinical samples. A PCR assay has been applied for the identification of Neisseria meningitidis (3, 6, 10) and for the simultaneous detection of N. meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, and streptococci as etiologic agents of bacterial meningitis (14). We have previously described the use of PCR with broad-range bacterial primers, combined with DNA sequencing, for the detection of Bartonella in a patient with culture-negative endocarditis (5). Here we report the application of this method to the examination of CSF from patients with a clinical diagnosis or suspicion of central nervous system infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CSF samples.

During the year 1995, 56 CSF samples from 46 patients were sent to the Department of Medical Microbiology, Turku University, Turku, Finland, for broad-range bacterial PCR assay. All patients were treated in the Department of Medicine (Turku University Central Hospital) and had a clinical diagnosis or suspicion of central nervous system infection. The CSF samples from these patients were simultaneously sent to the clinical microbiology laboratory of the hospital for Gram staining and aerobic and anaerobic bacterial cultures. The CSF cultures were carried out as follows. Blood agar and chocolate agar plates were inoculated with CSF directly from the puncture needle. In most cases a tube containing about 5 ml of CSF was also sent to the microbiological laboratory. From this tube the laboratory additionally inoculated blood, chocolate, and fastidious anaerobic agar plates. The blood and chocolate agar plates were incubated for 2 days in CO2 incubators at 35°C, and the fastidious anaerobic agar plates were incubated anaerobically for 5 days. In the hospital laboratory, the samples were also analyzed for the leukocyte and erythrocyte counts, as well as for the lactate and protein concentrations.

For each patient, a broad-range bacterial PCR assay was requested by the attending physician on a clinical basis. The characteristics of the CSF samples studied regarding the leukocyte counts, lactate and protein concentrations, and the results of the Gram staining, as well as the data on the clinical suspicion of bacterial meningitis and administration of antibiotic therapy before CSF was drawn, are given in Table 1. Of the CSF samples, nine were from seven patients with a clinical presentation indicative of acute bacterial meningitis. In addition, 24 CSF samples from 17 patients with a lymphocytic CSF finding were studied. For four of them, the meningitis was recurrent; during the previous years, each of these patients had experienced from two to six similar episodes of acute lymphocytic meningitis. Furthermore, we studied 22 specimens from 21 patients with slightly increased or normal CSF leukocyte counts and increased or normal CSF lactate and protein concentrations. Of these 21 patients, 19 had cerebral symptoms in association with or following an acute infection. Finally, one CSF sample studied contained blood, with 16,000 × 106 erythrocytes per liter and 116 × 106 leukocytes, of which 72% were polymorphonuclear, per liter.

TABLE 1.

Results of analysis of CSF from patients with suspected meningitis regarding the leukocyte count and protein and lactate concentrations, results of Gram staining, bacterial culture, PCR, and DNA sequencing, and the final clinical diagnosis for the patient

| Patient no. | No. of isolates | Patient on antibiotic therapy | Suspicion of bacterial meningitisa | CSF leukocyte count (106/liter) | CSF protein concn (mg/liter) | CSF lactate concn (mmol/liter) | CSF Gram staining result | CSF culture result | PCR test result | PCR homology | Final diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Yes | +++ | 860 | 3,620 | 10.6 | − | − | + | N. meningitidis | Meningococcal meningitis |

| 2 | 1 | No | +++ | 2 | 345 | 4.8 | + | N. meningitidis | + | N. meningitidis | Meningococcal meningitis |

| 3 | 1 | Yes | +++ | 960 | 1,980 | 17.0 | − | N. meningitidis | + | N. meningitidis | Meningococcal meningitis |

| 4–5 | 2 | No | +++ | 6,410–19,000 | 6,548–7,700 | 13.0–17.7 | + | N. meningitidis | + | N. meningitidis | Meningococcal meningitis |

| 6 | 1 | No | +++ | 1,115 | 3,204 | 8.4 | − | L. monocytogenes | − | Listeria meningitis | |

| 7 | 3 | No | +++ | 1,440–2,480 | 755–1,443 | 2.3–6.9 | − | − | − | Systemic lupus erythematosus meningitis | |

| 8 | 1 | Yes | + | 215 | 678 | 4.7 | − | − | − | Neurolymphoma | |

| 9 | 1 | Yes | ++ | 103 | 626 | 2.7 | − | − | − | Cerebral abscess | |

| 10 | 1 | Yes | ++ | 490 | 497 | 2.3 | − | − | − | Enteroviral meningitis | |

| 11–15 | 7 | Yes | + | 47–355 | 299–997 | 1.9–3.8 | − | − | − | Probable viral meningitis or encephalitis | |

| 16–24 | 14 | No | + | 60–462 | 398–1,560 | 1.9–3.0 | − | − | − | Probable viral meningitis or encephalitis | |

| 25–28 | 4 | Yes | + | 0–1 | 298–430 | 1.4–2.0 | − | − | − | Sepsis | |

| 29–33 | 6 | Yes | ++ | 0–15 | 328–604 | 1.8–4.6 | − | − | − | Undefined infection | |

| 34–38 | 5 | Yes | + | 1–2 | 282–756 | 1.4–2.5 | − | − | − | Undefined infection | |

| 39–40 | 2 | No | ++ | 0–23 | 448–468 | 3.8–4.6 | − | − | − | Undefined infection | |

| 41–42 | 2 | No | − | 2–3 | 315–535 | Not done | − | − | − | Postinfectious fatigue | |

| 43–45 | 3 | No | − | 1–3 | 418–610 | 1.1–2.7 | − | − | − | Noninfectious disease | |

| 46 | 1 | Yes | + | 116 | Not done | 4.4 | − | − | − | Intracranial hemorrhage |

+++, the clinical suspicion of bacterial meningitis was strong; ++, the suspicion of bacterial meningitis was moderate; +, there was only a minor suspicion of bacterial meningitis at the time that the CSF sample was drawn and the PCR assay with universal bacterial primers was requested; −, there was absence of any meaningful suspicion of bacterial meningitis.

Molecular analysis.

All CSF samples were initially screened by amplification of the 23S rRNA genes with oligonucleotide primers MS37 and MS38. On the basis of sequence analysis of the 23S rRNA genes, these primers cover several bacterial subdivisions, which include gram-positive bacteria with low G+C contents, gram-positive bacteria with high G+C contents, the Cytophaga, Flexibacter, and Bacteroides group, spirochetes, and the purple bacteria (13). Under the PCR conditions described below, the 23S rRNA genes of several bacterial species representing the subdivisions described above and two other subdivisions, Fusobacteria and the Planctomyces and Chlamydia group, have been successfully amplified. These bacterial species include important pathogenic bacteria that cause meningitis: N. meningitidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus agalactiae, H. influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli.

In case of a positive 23S rRNA gene PCR amplification result, as visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis, the finding was phoned to the clinician. The PCR-positive CSF specimens were further analyzed by sequencing of the 23S and/or the 16S rRNA gene. Amplification of the 23S rRNA gene was used in the initial screening of the CSF samples because of its higher sensitivity compared with that of amplification of the 16S rRNA gene. The 16S rRNA gene PCR product was preferably used for sequencing because of the more abundant sequence data presently available.

The 16S rRNA gene PCR and the primers used for the PCR have been described earlier by Weisburg et al. (16) and Jalava et al. (5).

DNA purification.

CSF was boiled at 94°C for 10 min and was then incubated overnight at 56°C with 100 μg of proteinase K (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) per ml.

23S and 16S rRNA gene bacterial PCR.

For the 23S rRNA gene PCR, amplification was performed in a DNA Thermal Cycler 480 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Emeryville, Calif.) for 30 cycles by using the following parameters: denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 60°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. For the 16S rRNA gene PCR, the amplification was performed with a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) for 38 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min). The cycles were preceded by a denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min, followed by an extension step at 72°C for 7 min. The total reaction volume was 50 μl, containing 5 μl of purified template DNA, 2 U of Dynazyme DNA polymerase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland), 10 pmol of each primer (Table 2), 200 μmol of each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate (Promega, Madison, Wis.) per liter, 1.5 mmol of MgCl2 per liter, 10 mmol of Tris-HCl (pH 8.8) per liter, 50 mmol of KCl per liter, and 0.1% Triton X-100. The sensitivity of the PCR assay with serially diluted purified N. meningitidis (N. meningitidis group B; no. 10026; National Collection of Type Cultures, London, United Kingdom) DNA as a template was tested by using PCR with primers MS37 and MS38.

TABLE 2.

PCR and sequencing primers

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Location (E. coli)a | Use | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fD1 modb | AGAGTTTGATC(TC)TGG(TC)T(TC)AG | 8–27 | 16S PCR | 16 |

| rP2 | ACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT | 1512–1492 | 16S PCR | 16 |

| 533 | GTGCCAGCAGCCGCGGTAA | 515–533 | 16S sequencing | 8 |

| MS37 | AGGATGTTGGCTTAGAAGCAGCCA | 1054–1077 | 23S PCR | This work |

| MS38 | CCCGACAAGGAATTTCGCTACCTTA | 1950–1926 | 23S PCR | This work |

| JJ04b | GTACC(CG)(CT)AAACCGACACAGGT | 1601–1629 | 23S sequencing | This work |

For detection of PCR products, 10 μl of the amplified DNA was separated by electrophoresis with a 1.5% SeaKem agarose gel (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) and the DNA band was visualized as UV fluorescence after staining with ethidium bromide. A negative control consisting of all reaction reagents necessary for PCR but with water as a template was included in all runs. As a positive control, DNA isolated from S. aureus was used. The primers were synthesized with a PCR-mate 391 DNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), and the sequencing primers (Table 2) were purified with oligonucleotide purification cartridges (Applied Biosystems).

Special care was taken to avoid contamination of the samples with amplicons (7). Strict measures were taken to separate the pre-PCR facilities from the post-PCR areas. Gamma irradiation and UV light irradiation were used to destroy possible traces of environmental bacterial DNA in the reagents (11).

DNA sequencing.

For sequencing, the PCR product was reamplified. Agarose gel slices containing the initially amplified DNA were crushed into 90 μl of distilled water, and 5 μl of the supernatant was used as a template for the second PCR. This reamplification consisted of 25 thermal cycles and was performed as described above for both primer sets, respectively. The reamplified PCR product was purified by 1.5% SeaPlaque GTG agarose gel electrophoresis (FMC BioProducts) and was separated from the agarose with β-agarose (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing procedures were carried out with the Taq DyeDeoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) and primer 533 or JJ04 (Table 2). The sequencing products were resolved by electrophoresis with a 6% polyacrylamide gel and a 373A Stretch DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Sequence analysis.

Nucleotide sequences were combined and handled by using the SeqEd 675 DNA Sequence Editor (Applied Biosystems). Comparison of the sequence with those in a reference database was performed by using an identification program based on selection of the longest recursive matches for optimal alignment of the compared sequences (3a). The reference database consisted of 3,827 sequences retrieved and combined from GenBank (1), EMBL (15), and the ribosomal database project (9). The final sequence comparisons to the best matches were done manually.

RESULTS

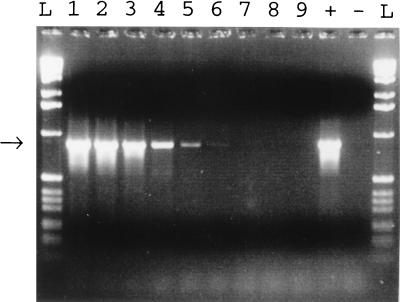

When purified N. meningitidis was used as the template in a serial dilution, the sensitivity of the PCR with primers MS37 and MS38 was 5 pg of DNA (roughly 500 genomes), as visualized after agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Sensitivity of the bacterial PCR. A dilution series of N. meningitidis DNA was analyzed by bacterial PCR and gel electrophoresis. The arrow indicates the band of the expected size. N. meningitidis DNA was used in the PCR in amounts of 500 ng (lane 1), 50 ng (lane 2), 5 ng (lane 3), 500 pg (lane 4), 50 pg (lane 5), 5 pg (lane 6), 500 fg (lane 7), 50 fg (lane 8), 5 fg (lane 9). Lane +, positive control; lane −, negative control; lane L, 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.).

The results of the bacterial cultures, PCR tests, and DNA sequencing of the CSF samples studied are presented in Table 1. The bacterial 23S rRNA gene was amplified from the CSF samples from five of the seven patients (patients 1 to 5) with a clinical presentation consistent with acute bacterial meningitis. After sequencing of the acquired 16S and/or 23S rRNA gene PCR products, a 98.3 to 100% homology with N. meningitidis was observed for all five patients. The 23S rRNA gene PCR product was sequenced for three specimens, the 16S rRNA gene PCR product was sequenced for one specimen, and both the 23S and the 16S rRNA gene products were sequenced for one specimen.

Among the five PCR-positive patients, patient 1 was a previously healthy, middle-aged female who presented in a regional hospital with a high fever and petechiae. After one blood sample for culture was taken, the patient was given 1 g of ceftriaxone and 80 mg of tobramycin intravenously and was referred to the Turku University Hospital. On admission to that hospital 12 h after the onset of clinical symptoms, she was in septic shock and had manifest intravascular coagulation. The CSF finding was suggestive of purulent meningitis, but Gram staining revealed no microbes and the bacterial cultures remained negative. The patient did not respond to therapy and died of multiorgan failure 2 weeks later. The autopsy findings were in accordance with fulminant meningococcal disease. In addition to the positive PCR finding, a meningococcal etiology was later confirmed by a significant rise in the levels of antibody to the N. meningitidis group B-specific polysaccharide and protein antigens in her serum. Within 6 days, the levels of antibody to the polysaccharide antigens increased from 332 to 6,280 and the levels of antibody to the protein antigens increased from 226 to >20,000. No changes in the levels of antibody to N. meningitidis group A, C, W, or Y were detected.

Patient 2, a young, previously healthy male, was admitted to the hospital after having a sore throat and a high fever throughout a night. Before admission he had received two doses of peroral penicillin. Six hours later a petechial rash appeared all over his body, and he developed septic shock and coagulopathy. The CSF finding was normal except for a moderately increased lactic acid concentration. Intravenous ceftriaxone was commenced and, simultaneously, two blood samples for culture were taken. The CSF grew N. meningitidis type B, but his blood cultures remained negative. He was treated in the intensive care unit for more than 1 month and was discharged 2 months later without any permanent disabilities. Patient 3, a young male with chondrodystrophy, presented after having a high fever and lethargy for 4 days. On admission the patient was stuporous and had stiffness of the neck. Due to his anatomic structure, a CSF sample could not be obtained through lumbar puncture. Therefore, ceftriaxone was started after two blood samples for culture were taken. Two days later, the patient developed acute hydrocephalus which was treated by ventriculostomy. The CSF sample acquired during the operation was purulent and grew N. meningitidis group B. Blood cultures yielded no growth. He received intravenous antimicrobial therapy for 2 weeks and recovered totally. Finally, patients 4 and 5 were admitted to the hospital on account of high fever, headache, nausea, and disorientation. Both had stiffness of the neck and lowered levels of consciousness. In addition, one of them had a petechial rash. The CSF findings for these patients were indicative of purulent meningitis, and the CSF samples grew N. meningitidis group B. Meningococci grew from the blood of the patient with petechiae. Both patients recovered rapidly and were discharged from the hospital in good clinical condition.

No bacterial 23S rRNA gene was amplified from the CSF samples from the two additional patients with purulent CSF findings. One of them was a young male whose acute myelocytic leukemia was in good hematologic remission after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. He was admitted on account of having a high fever for a few hours and soon developed headache and unconsciousness. Although the Gram staining was negative, his CSF and blood grew L. monocytogenes after an incubation of 2 days. Treatment with intravenous ampicillin led to his complete recovery from meningitis. The other was a patient with a 15-year history of systemic lupus erythematosus who had three similar episodes of sterile granulocytic meningitis during the study period. Subsequently, meningitis in this patient has been classified as a presentation of her systemic lupus erythematosus disease.

The final clinical diagnoses for the additional 39 patients studied are presented in Table 1. Among the 17 patients with lymphocytic CSF, 1 was later shown to have neurolymphoma and another had a cerebral abscess. One patient had enteroviral meningitis. For the remaining 14 patients, the final clinical diagnosis was determined to be probable viral meningitis or meningoencephalitis.

The PCR amplification assay was usually performed within 1 working day. However, the mean period from the time that the CSF sample was taken and the time that the sample arrived at the microbiological laboratory and the mean period from the time that the sample arrived at the laboratory to the time that the test result arrived at the hospital ward were 3.4 days (range, 1 to 14 days) and 1.9 days (range, 1 to 10 days), respectively. This variety was due to the fact that the PCR assays were not performed during the weekends. Sometimes there were also delays in the transportation of the specimens from the hospital to the PCR laboratory. Results from the sequence analysis were obtained from 2 to 5 days after the positive PCR results were obtained.

DISCUSSION

We describe here the application of the broad-range bacterial PCR and DNA sequencing for the etiologic diagnosis of meningitis. Based on the positive PCR findings for all five patients with meningococcal meningitis, combined with the 98.3 to 100% homology between the sequence of the PCR product and the N. meningitidis sequence, the sensitivity of this method for the detection of meningococcal meningitis was 100%. For these five patients, meningococci were cultured from the CSF of four patients, including one patient with a positive blood culture. For one patient, the diagnosis from CSF was confirmed by PCR alone. Later, meningococcal disease in this patient was also verified by a significant rise in the N. meningitidis group B-specific antibody titers in serum. Thus, the results for this patient illustrate that PCR amplification, combined with DNA sequencing, may provide a precise etiologic diagnosis even for patients with culture-negative meningitis.

Of the remaining 51 CSF samples studied, the negative PCR finding was in accordance with the negative findings for the bacterial cultures and Gram staining, as well as the eventual clinical diagnosis for 50 (98.0%) of the patients. However, the PCR test failed to detect the bacterial 23S rRNA gene in one CSF sample which later grew L. monocytogenes. Therefore, the overall sensitivity of the broad-range PCR assay in diagnosing bacterial meningitis was 83.3%. The specificity was 100%, since no false-positive results were obtained.

The reason why the Listeria meningitis was missed is unknown to us. This CSF specimen was tested for the presence of substances inhibitory to the PCR as described previously by Zhang et al. (17) and, in addition, by spiking the sample with a small amount of N. meningitidis DNA. These tests proved that no inhibitory substance was present in the CSF sample. We have postulated that since the isolation of DNA from gram-positive bacteria may be associated with some difficulties, the sensitivity of this PCR assay might be poorer for gram-positive organisms. Nevertheless, we have succeeded in detecting an abundance of gram-positive bacteria from various clinical samples. We have also demonstrated that this assay can detect Listeria; at least five different Listeria strains have been identified in our laboratory by this PCR method. Therefore, we regard it as possible that the amount of Listeria cells was small in that specific CSF sample, which was also negative by Gram staining. Efforts are being made in our laboratory to improve the methods of DNA isolation from gram-positive bacteria.

To our knowledge, the present paper is the first report of a prospective study in which PCR amplification with broad-range bacterial primers has been used to examine clinical CSF samples. All PCR assays were requested by the attending physicians for clinical purposes. One important indication was preceding antimicrobial therapy, jeopardizing the chances that the CSF and/or blood cultures would be positive. Of the five patients with meningococcal meningitis tested, three had been administered antimicrobial agents before the bacterial cultures; two of them had received intravenous antimicrobial treatment and one patient had received peroral antimicrobial treatment before the CSF was drawn. In addition, one patient was receiving his first dose of intravenous treatment while the blood cultures were drawn. Antimicrobial usage apparently suppressed bacterial growth. Although meningococci were grown from the CSF of two of these three patients, none had positive blood cultures, although the clinical picture suggested invasive meningococcal disease.

There are few previous reports on the application of molecular methods to the detection of the etiology of bacterial meningitis. Kristiansen et al. (6) have described the use of PCR for confirming the diagnosis of meningococcal meningitis in a culture-negative patient. The primers used were homologous to the N. meningitidis gene encoding dihydropteroate synthetase. In a retrospective blinded study, Ni et al. (10) used PCR to detect meningococcal DNA in 54 CSF samples from patients with meningococcal disease and from controls. Their PCR primers were specific for the meningococcal insertion sequence IS1106. The sensitivity and specificity of this PCR assay for the diagnosis of meningococcal meningitis were both 91%. Furthermore, Caugant et al. (3) have retrospectively used a nested PCR technique to detect meningococcal DNA from the CSF samples collected in the course of the Norwegian Meningococcal Serogroup Protection Trial; the sequencing of PCR products provided important information for epidemiologic purposes. In addition, Rådström et al. (14) have described a PCR approach for the simultaneous detection of N. meningitidis, H. influenzae, and streptococci in CSF in a retrospective study. Their PCR assay was divided into two DNA amplifications. The first step consisted of amplification with the universal primers. The second step resulted in a species-specific amplicon. The assay showed a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 96% with the clinical samples.

Admittedly, the results presented here do not indicate that our method would necessarily improve the ability to diagnose meningococcal meningitis compared to those of the methods described in previous publications (3, 6, 10) in which meningococcus-specific PCR techniques were used. The major advantage provided by the use of broad-range bacterial primers lies in the fact that, in addition to N. meningitidis, this method allows the detection of other important etiologic agents of meningitis, such as S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus, and E. coli. Due to the prospective nature of the present study, however, the patient material was unselected and none of the patients included had meningitis that was caused by these microorganisms. Moreover, our study differs from the studies described above on the application of molecular methods for the detection of bacterial meningitis in that they were used in a routine clinical setting and were requested by the attending physicians with the aim of improving the etiologic diagnosis.

It is of vital importance that all physicians applying the PCR assay be fully aware of the practical aspects involving the diagnosis of central nervous system infections. In a patient with suspected bacterial meningitis, antimicrobial therapy should be commenced rapidly. Therefore, decisions regarding the initial treatment in these patients must always be made before obtaining the results of the PCR assay. For the time being, Gram staining and bacterial culture remain the cornerstones of diagnosis in a clinical setting, and the PCR test is too slow. It is of further note that in its present form the PCR method with broad-range bacterial primers can be reliably performed only in laboratories specialized in PCR-based microbiological diagnostics.

In conclusion, our study differs from previous studies focusing on the use of PCR assays in the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis in that (i) it was prospective in nature, (ii) it was used in a routine clinical setting, and (iii) it applied a method which allows the detection of a wide range of bacterial species. Of the five patients with meningococcal meningitis, the diagnosis was confirmed by PCR alone for one patient. This patient had received intravenous antimicrobial treatment before the CSF sample for culture was taken. Our experience encourages the use of PCR with broad-range primers for the identification of bacterial DNA from CSF samples from patients with purulent meningitis, at least if the CSF is drawn after the administration of antimicrobial therapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benson D, Lipman D J, Ostell J. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2963–2965. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.13.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartwright K, Reilly S, White D, Stuart J. Early treatment with parenteral penicillin in meningococcal disease. Br Med J. 1992;305:143–147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caugant D A, Hoiby E A, Froholm L O, Brandtzaeg P. Polymerase chain reaction for case ascertainment of meningococcal meningitis: application to the cerebrospinal fluids collected in the course of the Norwegian Meningococcal Serogroup B Protection Trial. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:149–153. doi: 10.3109/00365549609049066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Eerola, E. Unpublished algorithm.

- 4.Gutell R R, Weiser B, Woese C R, Noller H F. Comparative anatomy of 16-S-like ribosomal RNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1985;32:155–216. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60348-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalava J, Kotilainen P, Nikkari S, Skurnik M, Vänttinen E, Lehtonen O-P, Eerola E, Toivanen P. Use of the polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing for detection of Bartonella quintana in the aortic valve of a patient with culture-negative infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:891–896. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kristiansen B-E, Ask E, Jenkins A, Fermer C, Rådström P, Sköld O. Rapid diagnosis of meningococcal meningitis by polymerase chain reaction. Lancet. 1991;337:1568–1569. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwok S, Higuchi R. Avoiding false positives with PCR. Nature. 1989;339:237–238. doi: 10.1038/339237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane D J, Pace B, Olsen G J, Stahl D A, Sogin M L, Pace N R. Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6955–6959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.6955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen N, Olsen G J, Maidak B L, McCaughey M J, Overbeek R, Macke T J, Marsh T L, Woese C R. The ribosomal database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3021–3023. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.13.3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ni H, Knight A I, Cartwright K, Palmer W H, McFadden J. Polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of meningococcal meningitis. Lancet. 1992;340:1432–1434. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92622-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikkari, S. 1994. Use of PCR in studies on microbial involvement in arthritis. Ann. Univ. Turk. Ser. D 152.

- 12.Noller H F. Structure of ribosomal RNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:119–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen G J, Woese C R, Overbeek R. The winds of (evolutionary) change: breathing new life into microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.1-6.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rådström P, Bäckman A, Qian N, Kragsbjerg P, Påhlson C, Olcen P. Detection of bacterial DNA in cerebrospinal fluid by an assay for simultaneous detection of Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, and streptococci using a seminested PCR strategy. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2738–2744. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2738-2744.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice C M, Fuchs R, Higgins D G, Stoehr P J, Cameron G N. The EMBL data library. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2967–2971. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.13.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Nikkari S, Skurnik M, Ziegler T, Luukkainen R, Möttönen T, Toivanen P. Detection of herpes viruses by polymerase chain reaction in lymphocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:1080–1086. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]