Abstract

Better integrating human developmental factors in genomic research is part of a set of next steps for testing gene-by-environment interaction hypotheses. This study adds to this work by extending prior research using time-varying effect modeling (TVEM) to evaluate the longitudinal associations between the PROSPER preventive intervention delivery system, a GABRA2 haplotype linked to alcohol use, and their interaction on adolescent delinquency. Logistic and Poisson analyses on eight waves of data spanning ages 11 to 19 (60% female, 90% Caucasian) showed the intervention reduced delinquency from ages 13 to 16. Moreover, interaction analysis revealed that the effect of the multicomponent intervention was significantly greater for T-allele carriers of the GABRA2 SNP rs279845, but only during the 13 to 16 age period. The results are discussed in terms of adolescent delinquency normativeness, implications for preventive intervention research, and the utility of incorporating development in GxE research.

Keywords: Delinquency, GABRA2, Intervention, GxE, Genetic

Introduction

Gene-environment interactions (GxE) are likely developmentally contingent such that some GxE are expected to manifest during specific developmental periods and not others (Rose and Dick 2010). Integrating development into molecular genetic research in psychology is one of several next-steps for a post-GWAS (genome-wide association study) research era that holds promise for identifying critical periods of GxE important for both behavioral and pharmaceutical interventions (Dick and EDGE Laboratory 2017). Given the importance of human developmental stages for GxE research, it is notable that there are few molecular genetic studies that incorporate development into GxE hypotheses. One explanation is that conventional methodological approaches may not be adequate for capturing the complexity of GxE across developmental stages (Trucco et al. 2018). Time-varying effect modeling (TVEM) is an innovative analytical approach that is ideal for pinpointing developmental periods when GxE manifest (and when they do not). This study extends research that demonstrates interrelations among GABRA2, adolescent externalizing problems, and alcohol misuse using TVEM to capture the developmental complexity of these interrelations. Prior to presenting specific hypotheses and characteristics of the data used to investigate them, pertinent literature is reviewed that explores how preventative interventions aimed at substance misuse impact delinquent behaviors during adolescence and current research and practices in GxE and gene-by-intervention (GxI) research.

Prevention and Intervention Research on Delinquency

Participation in non-violent delinquency during adolescence, such as truancy and theft, is considered normative, given that most adolescents will engage in some form of delinquent behavior during this developmental period (Moffitt 1993). Interventions that target multiple problematic outcomes, such as substance misuse and delinquency, and/or target their common risk and protective factors, such as negative peer influences, appear to reduce multiple co-occurring risk behaviors (Hale et al. 2014). For example, the Life Skills Training program is designed to reduce and/or prevent substance misuse by teaching problem solving and decision-making skills, how to manage stress and anxiety, and how to develop positive interpersonal relationships (Botvin and Griffin 2014). The program has demonstrated effectiveness for not only reducing substance misuse but also delinquency (Botvin et al. 2006). In a series of studies on the impact of preventative interventions delivered by the PROSPER project (which includes the Life Skills Training Program, see Methods section), intervention youth were lower in several indices of substance misuse relative to control adolescents at 1.5 years (Spoth et al. 2007), 4.5 years (Spoth et al. 2011) and 6.5 years (Spoth et al. 2013) past baseline. In a more recent study, interventions used in PROSPER were also linked to lower levels of conduct problem behavior during high school, including delinquent behaviors (Spoth et al. 2015). Broadly speaking, research on delinquency suggests that interventions targeting the shared etiology among substance misuse, delinquency, and other problem behaviors should be effective at reducing or preventing co-morbid risk behaviors.

Gene-by-Intervention Interactions

Intervention studies have several advantages for gene association research beyond correlational designs. Random assignment to treatement and control groups, a characteristic of rigorous prevention/intervention research, addresses a major challenge of GxE studies: gene-envionment correlation (rGE) or the self-selection of envionments based on genoytpe (Brody et al. 2013). Adding DNA to intervention studies also has provided opportunities to evaluate GxE using powerful experimental and quasi-experimental designs. In addition, the role that genetics plays in human development and complex behaviors, such as delinquency, has several important implications, such as how preventive interventions are designed, and, potentially, who receives what programming (Musci and Schlomer 2018). Importantly, these designs also have allowed researchers to consider genetics as a source of intervention heterogeneity (Belsky and van IJzendoorn 2015). In one of the earliest GxI studies, Brody and colleagues (2009) found the 5-HTTLPR short allele was associated with greater intervention efficacy on risk behavior initiation in a sample of African American adolescents. In a study of youth from the Fast Track prevention trial, adolescents who carried at least one copy of the glucocorticoid receptor gene A-allele (NR3C1, rs10482672) showed elevated conduct problems if they were in the control condition and lower than average conduct problems if they were in the intervention condition (Albert et al. 2015). In another study, Glenn et al. (2018) found a haplotype in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR, indexed by rs2268493) was associated with greater teacher-reported externalizing behavior problems; an intervention designed to reduce aggression was most effective for adolescents at genetic risk. PROSPER itself has also contributed to the GxI literature, including findings by Schlomer et al. (2015) who found PROSPER intervention assignment was linked to lower aggressive behavior problems among adolescents who were carriers of the Dopamine Receptor D4 (DRD4) 7-repeat allele and also reported they had hostile mothers (see also Janssens et al. 2017). In another PROSPER study, Schlomer and colleagues (2017) replicated findings from Brody et al. (2009) using a similar analytic approach and outcome measure. This latter finding demonstrates the potential reliability of GxI research (Belsky and van IJzendoorn 2015) as methods and approaches in this area of research advance (Musci and Schlomer 2018) and that at least some of the individual differences in intervention efficacy can be attributed to genetic variation.

Challenges of GxE Research

Although GxI research shows promise as a valid and reliable avenue of inquiry, progress in the more general and non-experimental candidate gene-by-environment interaction research (cGxE) field has been impeded by replication issues (for more on this topic and recent progress in cGxE research see Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn 2015; Brody et al. 2013; Musci and Schlomer 2018). Although issues with research replication are pervasive throughout psychology (Open Science Collaboration 2015), calls have been made to increase the quality of cGxE research specifically (Dick et al. 2015). As a result, guidelines for conducting and evaluating this research have been recently developed and several recommendations have been made for improving this area of research (e.g., Cleveland et al. 2016; Dick et al. 2015). One factor that has recently received increased attention is considering the role of human developmental stages in GxE and other molecular genetic studies (Dick and EDGE Laboratory 2017). The need to consider development in GxE is highlighted by research involving the GABRA2 gene and its association with externalizing problems and alcohol use. The GABA α-2 receptor subunit, encoded by GABRA2, is a critical part of a receptor that binds to the GABA neurotransmitter and inhibits neural activation. The α-2 subunit and other GABAA receptor subunits are action sites of several drugs (including ethanol) that upregulate GABA activity, which results in sedative and anxiolytic effects of alcohol consumption and may activate reward pathways that increase risk for alcohol misuse (Sieghart 2006). In a seminal study, Edenberg et al. (2004) showed a cluster of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in GABRA2 were linked to alcohol use disorder in adults. Stemming from this work, Dick et al. (2006) found that a GABRA2 haplotype identified in Edenberg et al. (2004) was related to conduct disorder during adolescence, a hypothesis that was based on the shared genetic etiology of alcohol dependence and conduct disorder shown in twin studies. In follow-up work, Dick et al. (2009) found GABRA2 SNPs within the haplotype were related to greater odds of elevated and persistent externalizing trajectories, especially among adolescents who reported low parental monitoring.

The observation that the relation between a specific GABRA2 haplotype and externalizing trajectories is moderated by parental monitoring also suggests that GABRA2 may be related to environmental sensitivity. Differential susceptibility theory (DST; Belsky and Pluess 2009; Boyce and Ellis 2005; Ellis et al. 2011) posits that the same intrapersonal characteristics related to increased risk for maladjustment when adolescents are exposed to harsh, unsupportive environments can lead to exceptional positive adjustment in more supportive circumstances. Individual factors that would otherwise be conceptualized as risk (diathesis stress) are conceptualized as plasticity or “differential susceptibility” factors that lead to better or worse outcomes depending on environmental exposures (Belsky et al. 2007). The idea that GABRA2 could confer such differential susceptibility is plausible, given recent fMRI research linking the GABRA2 haplotype described above to decreased neural activation to emotional stimuli (Trucco et al. 2018). Adolescents who have such low tonic activation may seek stimulation via behaviors that can result in adaptive or maladaptive outcomes, depending on prosocial or deviant outlets in the environment for these behaviors.

Empirical tests of the GABRA2 susceptibility hypothesis have provided support across several studies. For example, Simons et al. (2013) found evidence that the same GABRA2 haplotype was related to greater responsiveness to harsh parenting. Consistent with this work, Trucco and colleagues (2016) found the GABRA2 haplotype moderated the association between positive peer involvement and externalizing behavior problems. Importantly, adolescents with the GABRA2 putative risk genotype reported significantly fewer externalizing problems at higher exposure to prosocial peers and significantly more externalizing when prosocial peer exposure was low. A similar pattern of results, consistent with GABRA2 differential susceptibility, was found when examining trajectories of externalizing problems in conjunction with parental monitoring (Trucco et al. 2017). Intervention research that examined GABRA2 showed that the Strong African American Families (SAAF) substance misuse preventive intervention was most effective at reducing alcohol use among adolescents at GABRA2 genetic risk, suggesting greater sensitivity to the intervention for those with the “risk” haplotype (Brody et al. 2013). Similarly, Russell et al (2018) found the GABRA2 haplotype moderated the effect of the PROSPER preventative intervention delivery system on adolescent alcohol misuse; GABRA2 was related to stronger response to intervention programming, particularly during early adolescence.

Taken together, these studies indicate that (1) the role of GABRA2 may be developmentally contingent, whereby putative risk is most relevant for externalizing problems during adolescence and (2) the relation between GABRA2 and externalizing problems during adolescence likely manifests as environmental susceptibility rather than direct risk per se. Research is lacking, however, that examines GABRA2-by-intervention hypotheses for externalizing behavior problems, such as delinquency, which differs in etiology (Burt and Neiderhiser 2009), development (Bongers et al. 2004), and heritability (Burt 2012) compared to other aspects of externalizing behavior problems. In addition, a limitation of much of the research linking GABRA2 to externalizing phenotypes is that alcohol use is not controlled for (though see Trucco et al. 2014). Given the clear links between GABRA2 and alcohol use phenotypes, it is unclear if the results of externalizing studies are confounded by alcohol use patterns. Last, no studies have tested if these potential associations with delinquency vary across adolescent development.

The Current Study

The purpose of the current study was to build upon existing research on the associations between a well-studied GABRA2 haplotype and externalizing behavior problems. Delinquency is the focus of this study for two reasons. The first concerns consideration of differences in developmental patterns and potential genetic associations relative to other aspects of externalizing problems; the second is to help maximize distinguishability from comorbid behaviors such as alcohol use. Specifically, time-varying effect models (TVEM) were used to test developmental hypotheses about the relations between the PROSPER substance misuse preventative intervention delivery system, GABRA2, and GxI with delinquency across adolescence. Longitudinal and genetic data on a subsample of PROSPER youth (gPROSPER) were used to address two interrelated hypotheses. First, the association between PROSPER-delivered interventions and delinquency during early- to mid-adolescence was examined. It was hypothesized that intervention effects would be most pronounced during early adolescence when delinquency typically begins to increase. Second, the hypothesis was tested that the effect of the intervention would be greatest among adolescents at highest GABAR2 risk (GxI), consistent with the GABRA2 sensitivity hypothesis.

In testing these hypotheses the current research builds on prior work in several ways. First, because of the extensive research that links GABRA2 variation to alcohol use phenotypes, both correlational and experimental, alcohol use was controlled in all analyses. Doing this allows results to address the impact of modeled influences on delinquency net of alcohol use, rather than delinquency that might come with alcohol use. Second, following tests of the primary hypotheses, sensitivity analyses were conducted to help rule out alternative explanations for the findings, including controls for potential population stratification. Third, a formal test of the form of the GxI interaction was conducted to distinguish between diathesis stress and differential susceptibility. Last, the possibility of developmentally contingent associations is addressed by using TVEM to model associations across adolescence.

Methods

Procedure

Data for this study comes from the PROSPER project, a study of a university-community partnership model for delivering evidence-based preventative interventions (Spoth et al. 2017). The PROSPER project includes 28 rural communities that were randomized into 14 control and 14 intervention units. All 6th grade students in each school district were invited to participate; 90% participated at wave 1. Survey data were completed in-school during fall of 6th grade, again in the spring, and annually thereafter through 12th grade (8 waves total). A family-focused and school-based sequence of evidence-based preventive interventions was implemented in PROSPER intervention communities. Community-university teams selected from a menu listing family-focused and school-based interventions. All intervention school districts chose the family-focused Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10-14. For the -school-based program, six teams chose the All Stars curriculum (McNeal et al. 2004) and four each chose Life Skills Training (Botvin and Kantor 2000) and Project Alert (Ellickson et al. 2003). All three in-school programs target social norms surrounding substance misuse, peer affiliations, decision making, and personal goal setting (see Spoth et al. 2004). Implementation fidelity was high across all participants (Spoth et al. 2007).

Buccal DNA data were collected on a subset of PROSPER youth, which progressed in two stages. First, DNA was collected at wave 5 from adolescents who were part of a randomly selected subsample that also completed in-home interviews (N = 537). Second, during a follow-up young-adult assessment, DNA was collected on an additional N = 1495 participants (N = 2032 total). The current study is based on N = 1927 participants with reliable GABRA2 genotype data and phenotype data on delinquency. Among the current analytical sample, N = 1159 participants were female (60.1%) and N = 768 were male (39.9%). Sample participants primarily self-identified as White (N = 1731, 89.8%), Latino/Hispanic (N = 88, 4.6%), Black/African American (N = 36, 1.9%), and Asian (N = 25, 1.3%); they included smaller groups of other ethnicities (N = 47, 2.4%). The mean age of participants was 11.77 years (SD = .36) at wave 1, 12.24 (SD = .35) at wave 2, and increased by approximately 1 year at each wave through wave 8 (M = 18.15, SD = .35). On average, 6.69 (SD = 1.56) waves of data were available for each participant and 83.6% (12,882/15,416) of the data were present among all person-waves (1927*8 = 15,416). Missing data due to attrition was highest at wave 8 (34.1%) and was not associated with intervention participation, GABRA2, participant sex, or non-European ethnicity. Comparisons using wave 1 demographics showed participants with missing data at wave 8 were less likely to come from a dual parent home (r = −.16, p < .05) and more likely to have received free/reduced school lunch (r = .19, p < .05).

Measures

Descriptive information for all measures are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| M (SD) | Variable | Distribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave (grade) |

Delinquency | Alcohol use | Intervention status |

Control: 46.6% Intervention: 53.4% |

| 1 (6th) | 0.31 (0.83) | .08(.30) | GABRA2 (rs279845) | A/A: 21.1% A/T: 48.2% T/T: 30.7% |

| 2 (6th) | 0.35 (0.96) | 0.10 (0.33) | Parent marital status | Single parent: 20.0% Dual parent: 80.0% |

| 3 (7th) | 0.48 (1.19) | 0.18 (0.45) | Free/Reduced lunch | No: 27.1% Yes: 72.9% |

| 4 (8th) | 0.70 (1.42) | 0.31 (.62) | Sex | Male: 39.9% Female: 60.1% |

| 5 (9th) | 0.87 (1.60) | 0.47(0.75) | PC1 | −0.022 (0.005) |

| 6 (10th) | 0.96 (1.63) | 0.56 (0.82) | ||

| 7 (11th) | 1.07 (1.71) | 0.65 (0.87) | ||

| 8 (12th) | 1.07 (1.72) | 0.77 (0.90) | ||

Note: Values based on N = 1927 analytic sample. Descriptive information for delinquency are prior to recoding the data for logistic and count models

PC1 Principal Coordinate 1 (mean and standard deviation reported for PC1)

Adolescent delinquency

Adolescent delinquency was operationalized as non-violent conduct problem behaviors, given differences in etiology, development, and heritability relative to other aspects of externalizing. Eight self-report items were used to measure annual adolescent delinquent behavior. Example items include, “During the past 12 months, how many times have you…(1/2) Taken something worth less than/more than $25 that didn’t belong to you, (3) Skipped school or class without an excuse, and (4) Broken into or tried to break into a building just for fun or to look around.” Items that inquired about substance misuse were not included in this measure. Notably, in a prior study using the full PROSPER sample, Spoth and colleagues (2015) included items in their conduct problems measure that included physical aggression and property damage, in addition to the 8 items included in the current delinquency measure. These 4 items were omitted from the current measure to help distinguish between non-violent delinquency and aggression-related behavior problems.

Items used in the current delinquency measure were scored on a 1 = never to 5 = five or more times scale and were dichotomized into 0 = not in the past year, 1 = at least once in the past year. The dichotomized items were then summed within each wave. Possible values at a given wave ranged from 0 to 8 and average delinquency increased between wave 1 (M = .31, SD = .83) and wave 8 (M = 1.07, SD = 1.72). A measure similar to the one currently used has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in prior research (e.g., Simons et al. 2001). In the current sample, alpha reliabilities were above .80 for all waves except wave 1 (α = .68).

Intervention status

Within the current analytic sample (N = 1927), N = 898 participants were assigned to the control condition and N = 1029 were assigned to the intervention. Intervention Status was coded 0 = Control, 1 = Intervention.

GABRA2

The SNP rs279845 (A/T) was used to index GABRA2 variation. This SNP tags a GABRA2 linkage disequilibrium (LD) block and haplotype that has been extensively studied in connection with alcohol misuse (Dick et al. 2006; Edenberg et al. 2004) and delinquency phenotypes (Latendresse et al 2017; Trucco et al. 2017) and includes GABRA2 SNPs implicated in differential sensitivity (Trucco et al. 2016). Empirical findings related to rs279845 have been somewhat inconsistent, however, and some studies have found the A allele to confer risk and others the T allele. This issue was addressed by Lind et al. (2008) who suggested these inconsistent findings may be the result of interpreting complimentary genotypes derived from different DNA strands and, in general, the more common allele is associated with risk/sensitivity (Lind et al. 2008). In the current study, rs279845 was coded as 0 = A/A, 1 = A/T, 2 = T/T, given the T allele is the major allele in these data and part of the high-risk haplotype for alcohol abuse (Edenberg et al. 2004). rs279845 was genotyped using the OpenArray system from Life Technologies Inc. (now part of Thermo Fisher, Inc.), which utilizes TaqMan genotyping assays applied to an array. There were 91 missing cases on rs279845 due to genotyping failures. Genotype frequencies were in Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (Rodriguez et al. 2009): A/A = 407, A/T = 928, T/T = 592. Genotype frequencies did not differ across intervention conditions (r = .019, ns) or self-reported European vs. non-European ethnicity (r = −.028, ns). Genotype differences did modestly differ across gender (r = .071, p < .05).

Covariates

Covariates were used in this study to better establish phenotypic specificity and control for possible sources of confounding. To assess the unique associations between GABRA2, the intervention, and GxI on delinquency, 8 waves of alcohol misuse data were included as a covariate in all TVEMs. Alcohol misuse was assessed from two items that measured past month drinking frequency and past month intoxication frequency. Both measures were dichotomized from a 5-point scale due to skew and the two items were summed to create a measure of past month alcohol misuse that ranged from 0 to 2 (see Russell et al. 2018 for additional details). In the current study, mean alcohol misuse was .080 (SD = .30) at wave 1 and increased across the 8 waves of data (M = .773, SD = .90 at wave 8). Additional covariates from the baseline assessment also were used in TVEMs. The first was parent marital status (0 = Single Parent ((n = 377, 20.0%), 1 = Dual Parent (n = 1504, 80.0%)). The second was free/reduced school lunch receipt ((0 = No (n = 1367, 72.9%) and 1 = Yes (n = 507, 27.1%)). The third was adolescent sex ((0 = Male (n = 768, 39.9%) 1 = Female (n = 1159, 60.1%). A fourth covariate was included to address potential population stratification confounds using principal coordinates analysis on a set of ancestrally informative markers (Halder et al. 2008) using PLINK 1.9 (Purcell and Chang 2015). The first principal coordinate (termed PC1) captured variability in European vs. non-European genomic ancestry and was included in all models that contained rs279845 (see Cleveland et al. 2018 for additional details on the PC analysis).

Analysis Plan

Time-varying effects modeling (TVEM) estimates developmental change in an outcome without the need to fit a specific shape function (unlike multilevel or latent growth models). In addition, TVEM permits bivariate associations to vary over time by extending OLS regression to accommodate time. In the current study, participant age is used to measure time, which permits time effects to be evaluated as a continuous function of developmental time rather than discrete time intervals, such as data collection wave. Equation 1 shows the form of a time-varying effect model with one time-varying predictor:

| (1) |

where is the outcome for participant at participant age , is the mean of at a given age (assuming ), the slope coefficient reflects the association between and at a given age and is permitted to vary across ages, and are normally distributed residuals (see Tan et al. 2012).

The delinquency variables used in this study were coded to facilitate a two-step analysis procedure that longitudinally distinguishes between 1) no delinquency versus at least one delinquent behavior in the prior year and 2) less versus more delinquent behaviors in the prior year. First, the delinquency variable described above was dichotomized across waves as 0 = No delinquent behavior and 1 = at least 1 delinquent behavior in the past year. Frequencies for adolescents who committed at least one delinquent behavior in the past year increased from 18.2% at wave 1 to 45.6% at wave 8. This binary variable at each wave permits logistic analysis of the zero-inflated portion of the data by modeling the probability of engaging in any delinquent behavior during adolescence versus none. In the second step, the count part of the data were analyzed. Adolescents who abstained from delinquency at all available waves of data (N = 592) were dropped and a Poisson model was applied to the data from non-abstainers. Mean delinquency in the past year across waves increased from M = .45 (SD = .97) at wave 1 to M = 1.53 (SD = 1.88) at wave 8. In the TVEM results presented below, odds ratios (OR) are reported for logistic models and incident rate ratios (IRR) for Poisson models. In both cases, statistical significance is inferred when the upper or lower 95% confidence interval does not contain 1.00. All models included alcohol misuse as a time-varying covariate of delinquency.

Results

Logistic Time-Varying Effects Models

Unconditional model

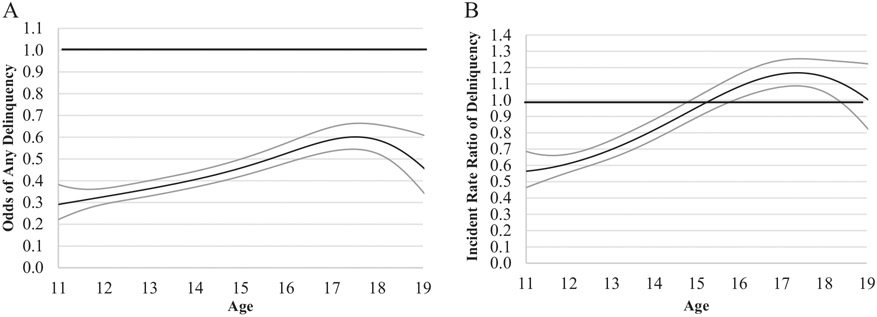

As can be seen in Fig. 1, when controlling for alcohol misuse, the odds of adolescents’ engaging in at least one type of delinquent behavior vs. no delinquent behavior increased over time until approximately age 17 and declined. Importantly, the odds of delinquent behavior were significantly lower than the odds of no delinquent behavior across adolescence. This finding indicates that although the odds of delinquency increase during adolescence, adolescents are, on the whole, persistently less likely to engage in delinquent behavior relative to no delinquent behavior at a given age during this time period.

Fig. 1.

Panel a odds ratio and upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of delinquent behavior vs. no delinquent behavior during adolescence. Panel b incident rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals for more vs. less delinquency. Where confidence intervals do not include 1.0 indicates statistical significance (p < .05)

Intervention status and GABRA2

Figures 2a-c depict the TVEM results for Intervention Status (2A) and GABRA2 (2B) when added as time-varying main effects of delinquent behavior, and the interaction between these variables (2C). Age periods when effects were significant (i.e., 95% confidence intervals fully above or below an odds ratio of 1.00) are highlighted in grey. As can be seen in Fig. 2a, Intervention Status was significantly related to lower odds of delinquency between ages 13.5 and 15.5 when alcohol misuse was controlled. Based on the plotted data, significant ORs for Intervention Status ranged from approximately .80 to .85 (p < .05) during this age period. Unlike Intervention Status, GABRA2 showed no significant main effect on delinquent behavior during adolescence (Fig. 2b). The interaction between Intervention Status and GABRA2 was significant, however, between ages 12 to 16 (Fig. 2c; ORs range = .72 to .80, p < .05).

Fig. 2.

Time-varying effects of Intervention Status, rs279845, and Intervention Status*rs279845 for delinquency vs. no delinquency (left column, a-d) and more vs. less delinquency (right column, e-h). Figures d and h display simple effects of the interactions in c and g. Shaded portions indicate where lines significantly deviate from 1.0 (p < .05). OR odds ratio, IRR incident rate ratio

To better understand this interaction, simple effects tests were conducted by re-centering rs279845 to reflect conditional Intervention Status associations at A/A, A/T, and T/T genotypes. As shown in Fig. 2d, the impact of the intervention at different ages differed by rs279845 genotype. Among rs279845 A/A adolescents, no significant association was found for the intervention on delinquency during early- to mid-adolescence. For A/T adolescents, the intervention was associated with lower odds of delinquency, primarily between ages 14 and 15. The largest and most enduring effect of the intervention was seen among adolescents with the rs279845 T/T genotype. Among these adolescents, the intervention was related to lower odds of delinquency (ORs range .60 to .78) between ages 12 and 16.5.

Poisson Time-Varying Effect Models

Unconditional model

Poisson models were used to evaluate time varying effects on the count part of the data (N = 1335). Results in Fig. 1b show the rate of delinquent behaviors (controlling for alcohol misuse) tended to be lower during early adolescence and increased into mid-adolescence before declining again to non-significance past age 18. This pattern of results indicates that adolescents who did not abstain from delinquency during adolescence engaged in significantly fewer delinquent behaviors during early adolescence relative to the overall adolescent mean. In addition, delinquency was greater starting at age 16, compared to the overall adolescent average.

Intervention status and GABRA2

Figure 2e-h display Intervention Status and GABRA2 effects, and their interaction. Similar to the results found in the logistic models, Intervention Status was significantly related to less delinquency between ages 13 and 16 when alcohol misuse was controlled (IRRs range = .82 to .88, p < .05; Fig. 2e). No association was found for GABRA2 (Fig. 2f), while the interaction between Intervention Status and GABRA2 was significant, but at a more restricted age period relative to the logistic model (age 15 to 16; IRRs range = .81 to .87, p < .05; Fig. 2g). Simple effects tests (Fig. 2h) showed the intervention was related to less delinquency among adolescents with the rs279845 A/T genotype between ages 14 and 15.5 (IRRs range = .89 to .91). The intervention was most effective among adolescents with the T/T genotype and, for them, between ages 12.5 to 16.5 years (IRRs range = .76 to .82, p < .05).

Sensitivity Analyses

To test if these results can be attributed to potential confounds, additional TVEMs were conducted. First, to help control for potential population stratification confounds, the PC1 covariate, which quantifies variability in European vs. non-European genomic ancestry, and its interaction with GABRA2 were included in both the logistic and Poisson models described above. Results of these models showed a similar pattern for the GABRA2-by-Intervention Status interaction terms. In addition, similar results were detected when self-reported non-Europeans were dropped from the analysis. Next, the three other covariates were added to the model (sex, wave 1 free/reduced school lunch receipt, and wave 1 parent marital status) in addition to PC1. Results showed a similar pattern for the Intervention Status and GABRA2 main effects as well as the GABRA2-by-Intervention Status interaction terms (see Appendix, Fig. 3). These findings suggest that the above results, which also control for alcohol misuse, are additionally robust to European vs. non-European population stratification confounds, adolescent sex, parent marital status, and free/reduced school lunch receipt. Last, the interaction form was formally tested to determine if the interaction between GABRA2 and Intervention Status reflected an ordinal (consistent with diathesis stress) or a disordinal interaction (consistent with differential susceptibility). SAS (2011) was used to estimate a non-linear regression that includes the interaction cross-over point as a model parameter with 95% confidence intervals (see Widaman et al. 2012). The cross-over point reflects the coordinate where the simple-slope regression lines intersect and can be used to infer the probable form of the interaction in the population in conjunction with its 95% CI. For simplicity, the continuous delinquency measure at wave 5 was used, given that approximates participant age when the interaction was significant in the TVEM models (M = 15.20; see Fig. 2g). Because the pattern of results suggests the effect of the intervention differed across genotypes, the cross-over point is interpreted in terms of the intervention metric (0 to1). Results showed the cross-over point was estimated at .57 with a 95% CI of .21 to 93. Based on this cross sectional analysis, the form of the interaction in the population likely resembles differential susceptibility.

Fig. 3.

Time-varying effects of Intervention Status*rs279845 for delinquency vs. no delinquency a and more vs. less delinquency b while controlling for covariates: alcohol misuse, PC1, sex, wave 1 free/reduced school lunch receipt, and wave 1 parent marital status. Shaded portions indicate where lines significantly deviate from 1.0 (p < .05). OR odds ratio, IRR incident rate ratio

Discussion

Based on the observation that phenotypic correlations with GABRA2 are expected to change over time – from primarily externalizing behavior problems in adolescence to alcohol misuse problems in adulthood – time-varying effects modeling (TVEM) was used to examine the time-varying association between PROSPER preventative interventions, GABRA2 (indexed by rs279845), and their interaction on adolescent delinquency. It was hypothesized that intervention effects would be strongest during early adolescence, when delinquency typically begins to increase. Consistent with prior research that suggests GABRA2 conveys differential susceptibility to environments during adolescence, it was hypothesized that intervention effects would be most pronounced among adolescents with putative GABRA2 risk genotypes. To test these hypotheses, 8 waves of data were used that spanned ages 11 to 19 years on the PROSPER genetic subsample (gPROSPER). A two-step analytic approach was used to distinguish between adolescents that did and did not commit any type of delinquent behavior at a given wave and those that committed more versus fewer types of delinquent behaviors. The former required a logistic TVEM while the latter necessitated a Poisson model that excluded adolescents who abstained from delinquency. Given correlational and experimental research linking GABRA2 to adolescent alcohol use, all TVEMs included alcohol misuse as control variable.

Before discussing the intervention and GxI findings, a key finding from the unconditional TVEMs should be highlighted: across early- to mid-adolescence the odds of adolescents reporting at least one type of delinquent behavior were relatively low in these data. This finding should be emphasized as it challenges the notion that delinquency is normative during adolescence. The idea that delinquency is normative derives from the observation that delinquency is more common during adolescence (Moffitt et al. 2002) and by longitudinal evidence that shows delinquency markedly increases during this developmental period (Bongers et al. 2004). Although it may be the case that over the entire course of adolescence it is somewhat typical for adolescents to do some type of delinquent behavior, when viewed on a smaller time scale, such as a year, which was used in this study, adolescents would not be accurately characterized as a delinquent population. Based on the current findings, for example, 17 year-olds as a group are more likely to not perform a delinquent type of behavior even though they may have already done so sometime in the prior 6 or 7 years. Even among adolescents who did not abstain from delinquency, the range of delinquent behaviors expressed was relatively low, especially before age 16. From a practical perspective, these data suggest that although performing a delinquent type of behavior at some point during adolescence is normative, regularly taking part in delinquency should not be considered normal.

Another key finding from this study is that the PROSPER preventive intervention delivery system was effective at reducing adolescent delinquency during early adolescence (as noted above, a prior analysis of the full PROSPER in-school sample found significant effects on a broader range of conduct problems during the high school period – Spoth et al. 2015). In both the logistic and Poisson models, the intervention was related to lower delinquency, most strongly prior to age 16. This pattern of results held when controlling for potential confounds including sex, wave 1 free/reduced school lunch receipt, wave 1 parent marital status, ethnicity, and adolescent alcohol misuse. The most important of these controls is alcohol use given ample research that empirically links the two behaviors. This study builds on that work and suggests that these interventions, and potentially others like it, may have independent effects on both alcohol misuse and adolescent delinquency, particularly during early adolescence. A possible implication of this finding is that targeting factors related to the shared etiology of substance use and delinquency during early adolescence may have independent effects on both problem behaviors.

It is important to note, however, that the two sets of findings described above indicate that the intervention was most effective at reducing delinquency during the age period when delinquency was relatively low (i.e., prior to age 16), which may call into question the significance of reducing delinquency at this age. When considered in the context of the dual taxonomy model (Moffitt et al. 2002), the implications of this finding becomes more clear. For example, it is possible that a portion of the intervention adolescents could be classified as life-course persistent offenders, who may have otherwise been offending during this age period if not for the intervention. These adolescents may have had their pattern of delinquent behavior “interrupted”, either temporarily or, perhaps for some, permanently. The implications of temporary suspension of delinquency behaviors within this population for later delinquency and adult criminality has not been explored, though permanent cessation of these behaviors would be of considerable significance. Similarly, it is likely that some of the intervention adolescents who would have otherwise been offending during this age period could be classified as adolescent-limited offenders. Among this population of adolescents, it is likely that delinquency initiation is being delayed or that in some cases adolescents completely abstain from delinquency after intervention participation. Early onset delinquency (i.e., prior to age 14; Forsyth et al. 2018) is a defining characteristic of lifetime patterns of offending. Delaying delinquency onset, while not wholly preventing delinquent behaviors, may reduce the overall frequency and severity of offending over time. Nonparametric, longitudinal statistical approaches such as latent class growth models are needed to properly address these questions and should be the subject of future research.

Turning to the genetic findings, results showed that the effect of the intervention was stronger and most pronounced from age 12 to 16 among adolescents homozygous for the rs279845 T-allele, consistent with the GABRA2 sensitivity hypothesis. When the form of the interaction was formally tested in a cross-sectional analysis, the results indicated the interaction was consistent with differential susceptibly. Belsky et al. (2007) describe criteria for distinguishing differential susceptibility from other interaction forms, which includes evidence for a cross-over interaction, independence between the susceptibility factor (GABRA2) and the outcome (delinquency), and no correlation between the predictor (Intervention Status) and susceptibility factor. Consistent with these criteria, the reparametrized regression suggests the interaction is a cross-over, there were no main effects of GABRA2 on delinquency anytime during adolescence, and there was no correlation between randomized intervention assignment and GABRA2. In addition, lack of association between Intervention Status and delinquency among adolescents with the GABRA2 A/A genotype is consistent with the more “fixed” component of differential susceptibility theory. Considered together, there is strong evidence to suggest that GABRA2, as indexed by rs279845, conveys differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Nonetheless, it should be noted that although participation in the intervention may be consistent with the positive side of environmental sensitivity, participating in the control condition should not be equated with environmental negativity. Although the current data are strongly in favor of a DST interpretation, conclusive evidence requires that the environmental variable encompass the full range of positive and negative.

Adding a Developmental Perspective to GxE

The need to evaluate GxE in a developmental context (GxExD; Bjorklund, Ellis, & Rosenberg, 2007) has been emphasized in psychological research for some time (Dahl and Conway 2009). The current research contributes to an emerging body of empirical work that incorporates development into GxE research. Considering how genetic associations vary over developmental time will be enlightening for understanding how and when GxE manifest. Given the GxI association with delinquency was age-limited in the current study, falling to non-significance past age 16, cross-sectional analysis of these data may have failed to detect a significant GxI if analyses were conducted only on this later developmental period. Such a null finding could be interpreted as a replication failure. Consistent with this line of thinking, incorporating development into GxE hypotheses could help clarify some replication issues. Developmental considerations may be particularly important for clarifying non-replication across GxE studies given that their relatively small samples may also have restricted age ranges. Historically speaking, addressing replication issues in GxE research has focused on producing sets of direct replications by homogenizing analytic models and variables. Even direct replications that use identical measures and models may fail to reproduce findings if the samples used have meaningful heterogeneity, such as different age distributions or focal developmental periods. Although similar studies have addressed developmental issues by controlling for age (Culverhouse et al. 2018), treating age as a covariate misses potentially important developmental changes in gene-phenotype associations (Dick 2013) that may contribute to non-replication. Although not addressing development specifically, recent GWA studies have demonstrated that gene-environment interactions derived from between-sample heterogeneity can explain a large portion of SNP-based heritability for some phenotypes (Tropf et al. 2017). Furthermore, between-sample heterogeneity can undermine gene identification efforts that focus on universal main effects via attenuated statistical power, even in highly powered GWAS (de Vlaming et al. 2017). In total, greater focus on developmental issues can lead to more precise findings in GxE research as well as large-scale genomic research.

Adding a developmental perspective should also direct GxE research toward environmental factors that are particularly important during developmentally sensitive periods. The developmental taxonomy model of antisocial behavior hypothesizes that adolescent-limited delinquents are likely mimicking life-course persistent antisocial adolescents in an effort to obtain peer status associated with delinquent behaviors (Moffitt et al. 2002). Based on this model, genetic risk for delinquency could only manifest if there is exposure to delinquent peers. A primary goal of the PROSPER-delivered interventions centers on better navigating peer relationships, which could limit adolescent exposure to delinquent peers through self-selection out of these groups during a developmental period when sensitivity to peer pressure is highest (Steinberg and Monahan 2007). It may be the case, then, that reducing exposure to delinquent peers may be the mechanism underlying the intervention’s effectiveness at reducing delinquency. Greater vs. less exposure to delinquent peers may similarly contribute to the stronger intervention effects observed for GABRA2 risk allele carriers. Neurobiological research on GABRA2 suggests that risk variants are associated with reduced neural activation, which can lead to stimulation-seeking behaviors (Trucco et al. 2018). Developmental outcomes related to GABRA2 may depend on environmental context, such as prosocial or delinquent peer exposure, in a manner consistent with differential susceptibility and that may change across developmental periods. Additional research is needed that combines interventions, genetics, development, and neuroscience to elucidate mechanisms.

Strengths and Limitations

The current research has several strengths. First, TVEM is ideal for testing developmental hypotheses such as how delinquency unfolds over time and how associations, such as interventions, genes, and GxI, change over development and can identify critical periods of effect. Second, this study builds on a strong foundation of prior research on the interrelations between GABRA2, alcohol use, and externalizing behavior problems (e.g., Brody et al. 2013; Russell et al. 2018; Trucco et al. 2016, 2017) and expands on this work, in part, by controlling for alcohol misuse, which helps disambiguate this literature. Last, this was done while distinguishing between different types adolescent delinquency phenotypes: 1) no delinquency versus at least one delinquent act in the prior year and 2) less versus more delinquent behaviors in the prior year. The fact that the findings were similar between the logistic and Poisson models provides additional evidence that these findings are not an aberration of one or another statistical model.

Despite these strengths, the limitations of this study need also be acknowledged. Adolescent participants in this sample came from rural areas, were almost entirely Caucasian, and the majority were female. Although sex and ethnicity (via population stratification, PC1) covariates were included, different findings may emerge in samples that are more urban and/or have a larger portion of non-Caucasians, which may be especially relevant for conclusions about delinquency normativeness. Additional longitudinal research is needed to determine if the present results generalize to other populations. Additional research will also be needed to further expand this research and test for replication.

Conclusion

Genomic research and GxE in particular can make significant advances by better incorporating a development perspective, which can elucidate when during the life course genetic associations and interactions manifest (Dick and EDGE Laboratory et al. 2017). In this study, evidence for a developmentally sensitive interaction is presented between GABRA2 variation linked to putative differential susceptibility (Trucco et al. 2016, 2017) and interventions that reduce substance misuse and delinquency (Spoth et al. 2015), which manifested primarily in early adolescence. Further, a statistical test of the form of the interaction strongly suggests that rs279845 in GABRA2 conveys differential susceptibility to environments, consistent with prior GABRA2 work. These findings indicated a time-limited period of sensitivity whereby the intervention was most effective at reducing early adolescent delinquency and was most impactful for adolescents with GABRA2 (rs279845) genotypes. An implication of these findings is that failures to replicate in genomic research may be partially accounted for by improperly addressing age-dependent genetic associations. In addition, this study highlights that delinquency normativeness during adolescence must be evaluated with respect to time (Bongers et al. 2004). Although it may be common for an adolescent to engage in one or a few types of delinquent behaviors over the course of adolescence, the present results underscore that delinquency is not characteristic of adolescents’ typical behavior (Moffitt et al. 2002). Last, this research makes an additional significant contribution to understating the etiology of delinquent behavior by distinguishing it from comorbid behaviors vis-à-vis defining delinquency in terms of non-violent offences, non-substance use behaviors, and controlling for alcohol misuse in all relevant analyses. Taken together, this research makes a strong case that genetic, environmental, and GxE associations should be evaluated in a developmental context.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Deborah Grove and Ms. Ashley Price of the Penn State Genomics Core Facility for DNA purification and genotyping. For participant recruitment we recognize the efforts of Shirley Huck, Cathy Owen, Debra Bahr, and Anthony Connor of the Iowa State University Survey and Behavioral Research Services; Rob Schofield and Dean Stankowski of the Penn State University Survey Research Center; and Lee Carpenter, Kerry Hair, and Amanda Griffin of Penn State.

Funding

Work on this article was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (grants DA030389 and DA013709). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Biographies

Gabriel L. Schlomer is an assistant professor at the University at Albany, SUNY Division of Educational Psychology and Methodology. He received his Ph.D. in Family Studies and Human Development from the University of Arizona. His major research interests include gene-environment interplay, aggression, parent-child conflict, and adolescent development.

H. Harrington Cleveland is an associate professor at The Pennsylvania State University Department of Human Development and Family Studies. He received his Ph.D. in Family Studies and Human Development from the University of Arizona. His major research interests are gene-environment interplay, substance use, and recovery.

Arielle R. Deutsch is an assistant professor at the University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics. Dr. Deutsch examines how complex systems foster positive or negative outcomes related to the development of alcohol use and sexual health over age. Her lab works to better understand specific contexts contributing to personal and population-level differences, to benefit strategies for implementation of health-improving interventions.

David J. Vandenbergh is an associate professor at the Pennsylvania State University in the Department of Biobehavioral Health and Penn State Institute of the Neurosciences. He received his Ph.D. in Biochemistry from The Pennsylvania State University. His areas of research interest are in understanding the basis of individual differences in addictive behaviors, which includes both genes and the environment. His areas of expertise include molecular biology, molecular and behavioral neuroscience, and genetics.

Mark E. Feinberg is a Research Professor at The Pennsylvania State University in the Prevention Research Center. He received his Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology from George Washington University. His major research interests include family processes and preventive interventions.

Mark T. Greenberg is the Bennett Chair of Prevention Research at The Pennsylvania State University Prevention Research Center and in Human Development and Family Studies. He received his Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from the University of Virginia. His major research interests include prevention, substance use, and mindfulness.

Richard L. Spoth is the F. Wendell Miller Senior Prevention Scientist and the Director of the Partnerships in Prevention Science Institute at Iowa State University. As the Institute director, Dr. Spoth provides oversight for an interrelated series of studies addressing motivational factors influencing prevention program participation, program efficacy, culturally-competent programming, and dissemination of evidence-based programs.

Cleve Redmond is the Associate Director of the Partnerships in Prevention Science Institute at Iowa State University. His major research interests are prevention, substance use, and adolescence.

Appendix

Footnotes

Data Sharing and Declaration This manuscript’s data is not publicly available.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Albert D, Belsky D, Crowley DM, Latendresse SJ, Aliev F, Riley B, Dick DM, & Dodge K (2015). Can genetics predict response to complex behavioral interventions? Evidence from a genetic analysis of the Fast Track randomized control trial. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 34, 497–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & van IJzendoorn MH (2015). The hidden efficacy of interventions: Gene x environment experiments from a differential susceptibility perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 11.1–11.29. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & van IJzendoorn MH (2007). For better and for worse. Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, & Pluess M (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 885–908. 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, & van IJzendoorn MH (2015). What works for whom? Genetic moderation of intervention efficacy. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 1–6. 10.1017/S0954579414001254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund DF, Ellis BJ, & Rosenberg JS (2007). Evolved probabilistic cognitive mechanisms: An evolutionary approach to gene × environment × development interactions. In Kail RV (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior: Vol. 35. Advances in child development and behavior (pp. 1–36). San Diego, CA, US: Elsevier Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, & Verhulst FC (2004). Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 75, 1523–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, & Griffin KW (2014). Life skills training: preventing substance misuse by enhancing individual and social competence. New Directions for Youth Development, 141, 57–65. 10.1002/yd.20086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, & Kantor LW (2000). Preventing alcohol and tobacco use through life skills training: theory, methods, and emperical findings. Alcohol Research & Health, 24, 250–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, & Nichols TD (2006). Preventing youth violence and delinquency through a universal school-based prevention approach. Prevention Science, 7, 403–408. 10.1007/s11121-006-0057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, & Ellis BJ (2005). Bioliogical sensitivity to context I: an evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology, 17, 271–301. 10.1017/s0945479405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, & Beach SRH (2013). Differential susceptibility to prevention: GABAergic, dopaminergic, and multilocus effects. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 863–871. 10.1111/jcpp.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Beach SRH, Hill KG, Howe GW, Prado G, & Fullerton SM (2013). Using genetically informed, randomized prevention trials to test etiological hypotheses about child and adolescent drug use and psychopathology. American Journal of Public Health, 103(Suppl), S19–S24. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Beach SRH, Philibert RA, Chen Y, & Murry VM (2009). Prevention effects moderate the association of 5-HTTLPR and youth risk behavior initiation: Gene x environment hypotheses tested via a randomized prevention design. Child Development, 80, 645–661. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA (2012). How do we optimally conceptualize the heterogeniety within antisocial behavior? An argument for aggressive versus non-aggressive behavioral dimensions. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 263–279. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, & Neiderhiser JM (2009). Aggressive versus non-aggressive antisocial behavior: distinctive etiolgical moderation by age. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1164–1176. 10.1037/a0016130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Schlomer GL, Vandenbergh DJ, Wolf PSA, Feinberg ME, Greenberg MT, Spoth RL, & Redmond C (2018). Associations between alcohol dehydrogenase genes and alcohol use across early- and mid-adolescence: moderation by preventative intervention. Development and Psychopathology, 30, 297–313. 10.1017/S0954579417000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Schlomer GL, Vandenbergh DJ, & Wiebe RP (2016). Gene x intervention designs: a promising step toward understanding etiology and building better preventative interventions. Journal of Criminology and Public Policy, 15, 711–720. [Google Scholar]

- Culverhouse RC, Saccone NL, Horton AC, Ma Y, Anstey KJ, Banaschewski T, & Bierut LJ (2018). Collaborative metaanalysis finds no evidence of a strong interaction between stress and 5-HTTLPR genotype contributing to the development of depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 23, 133–142. 10.1038/mp.2017.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE, & Conway AM (2009). Self-regulation and the developoment of behavioral and emotional problems: toward an integrative conceptual and translational research agenda. In Olsen SL & Sameroff AJ (Eds.), Biopsychosocial regulatory processes in the development of childhood behavior problems. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Vlaming R, Okbay A, Reitveld CA, Johannesson M, Magnusson PKE, Uitterlinden AG, & Koellinger PD (2017). Meta-GWAS accuracy and power (MetaGAP) calculator shows that hiding heritibility is paritally due to imperfect genetic correlations across studies. PLoS Genetics, 13, 1–23. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM (2013). Developmental considerations in gene identificiation efforts. In MacKillop J & Munafò MR (Eds.), Genetic influences on addiction: an intermediate phenotype approach. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Agrawal A, Keller MC, Adkins A, Aliev F, Monroe S, Hewitt JK, Kendler KS, & Sher KJ (2015). Candidate gene-environment interaction research: reflections and recommendations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 37–59. 10.1177/1745691614556682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Bierut L, Hinrichs A, Fox L, Bucholz KK, Kramer J, & Foroud T (2006). The role of GABRA2 in risk for conduct disorder and alcohol and drug dependence across developmental stages. Behavior Genetics, 36, 577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM & EDGE Laboratory (2017). Post-GWAS in psychiatric genetics: a developmental perspective on the “other” next steps. Genes, Brain, & Behavior. 10.1111/gbb.12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Latendresse SJ, Lansford JE, Budde JP, Goate A, Dodge KA, & Bates JE (2009). Role of GABRA2 in trajectories of externalizing behavior across development and evidence of moderation by parental monitoring. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 649–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edenberg HJ, Dick DM, Xuei X, Tian H, Almasy L, Bauer LO, & Kwon J (2004). Variations in GABRA2, encoding the α2 subunit of the GABAA receptor, are associated with alcohol dependence and with brain oscillations. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 74, 705–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF, Ghosh-Dastidar B, & Longshore DL (2003). New inroads in preventing adolescent drug use: results from a large-scale trial of project ALERT in middle schools. American Journal of Public Health, 93(11), 1830–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & van IJzendoorn MH (2011). Differential susceptibility to the environment: an evolutionary-neurodevelopmental theory. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 7–28. 10.107/s09545794100000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CJ, Dick SJ, Chen J, Biggar RW, Forsyth YA, & Burstein K (2018). Social psychological risk factors, delinquency and age of onset. Criminal Justice Studies, 31, 178–191. 10.1080/1478601X.2018.1435618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn AL, Lochman JE, Dishion T, Powell NP, Boxmeyer C, & Qu L (2018). Oxytocin receptor gene variant interacts with intervention delivery format in predicting intervention outcomes for youth with conduct problems. Prevention Science, 19, 38–48. 10.1007/s11121-017-0777-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder I, Shriver M, Thomas M, Fernandez JR, & Frudakis T (2008). A panel of ancestry informative markers for estimating individual biogeographical ancestry and admixture from four contents: utility and applications. Human Mutation, 29, 648–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale DR, Fitzgerald-Yau N, & Viner R (2014). A systematic review of effetive interventions for reducing multiple health risk behaviors in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health, 104, e19–e41. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens A, van den Noortgate, Goossens L, Colpin H, Verschueren K, Claes S, & van Leeuwen K (2017). Externalizing problem behavior in adolescence: parenting interacting with DAT1 and DRD4 genes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 27, 278–297. 10.1111/jora.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse SJ, Henry DB, Aggen SH, Byck GR, Ashbeck AW, Bolland JM, & Dick DM (2017). Dimensionality and genetic correlates of problem behavior in low-income African American adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46, 824–839. 10.1080/15374416.2015.1070353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind PA, MacGregor S, Agrawal A, Montgomery GW, Heath AC, Martin NG, & Whitfield JB (2008). The role of GABRA2 in alcohol dependence, smoking, and illicit drug use in an Australian population sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 1721–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal RB, Hansen WB, Harrington NG, & Giles SM (2004). How All Stars works: an examination of program effects on mediating variables. Health Education & Behavior, 31, 165–178. 10.1177/1090198103259852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, & Milne BJ (2002). Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 179–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musci R & Schlomer GL (2018). Incorporating genetics in prevention science: considering methodology and implications. Prevention Science, 19, 1–5. 10.1007/s11121-017-0836-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349, aac4716 10.1126/science.aac4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SM & Chang CC (2015). PLINK 1.9. https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, & Day INM (2009). Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing of biological ascertainment for Mendelian randomization studies. American Journal of Epidemiolgy, 169, 505–514. 10.1093/aje/kwn359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RJ, & Dick DM (2010). Commentary on Agrawal et al. (2010): social environments modulate alcohol use. Addiction, 105, 1854–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell MA, Schlomer GL, Cleveland HH, Feinberg M, Greenberg M, Spoth R, & Vandenbergh DJ (2018). PROSPER intervention effects on adolescents’ alcohol misuse vary by GABRA2 genotype and age. Prevention Science, 19, 27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. 2011. SAS® 9.3 Statements: Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Cleveland HH, Vandenbergh DJ, Feinberg ME, Neiderhiser JM, Greenberg MT, & Redmond C (2015). Developmental differences in early adolescent aggression: a gene × environment × intervention analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 581–597. 10.1007/s10964-014-0198-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Cleveland HH, Feinberg ME, Wolf PSA, Greenberg MT, Spoth RL, Redmond C, Tricou EP, & Vandenbergh DJ (2017). Extending previous cGxI findings on 5-HTTLPR’s moderation of intervention effects on adolescent substance misuse initiation. Child Development, 88, 2001–2012. 10.1111/cdev.12666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W (2006). Structure, pharmacology, and function of GABAA receptor subtypes. Advances in Pharmacology, 54, 251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Chao W, Conger RD, & Elder GH (2001). Quality of parenting as mediator of the effect of childhood defiance on adolescent friendship choices and delinquency. A growth curve analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Lei M, Beach SRH, Brody GH, Gibbons FX, & Philibert RA (2013). Genetic moderation of the impact of parenting on hostility toward romantic partners. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 325–341. 10.1111/jomf.12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Greenberg M, Bierman K, & Redmond C (2004). PROSPER community-university partnership model for public education systems: capacity-building for evidence-based, competence-building prevention. Prevention Science, 5, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Clair S, Shin C, Greenberg M, & Feinberg M (2011). Preventing substance misuse through community–university partnerships: randomized controlled trial outcomes 4½ years past baseline. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40, 440–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Greenberg M, Clair S, & Feinberg M (2007). Substance-use outcomes at 18 months past baseline: the PROSPER community-university partnership trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32, 395–402. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Greenberg M, Feinberg M, & Schainker L (2013). PROSPER community–university partnership delivery system effects on substance misuse through 6 1/2years past baseline from a cluster randomized controlled intervention trial. Preventive Medicine, 56, 190–196. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Greenberg MT, Feinberg ME, & Trudeau L (2017). PROSPER delivery of universal preventtive interventions with young adolescence: long-term effects on emerging adult substance misuse and assocaited risk behviors. Psychological Medicine. 10.1017/S0033291717000691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Trudeau LS, Redmond C, Shin C, Greenberg MT, Feinberg ME, & Hyun G (2015). PROSPER partnership delivery system: effects on adolescent conduct problem behavior outcomes through 6.5 years past baseline. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Monahan KC (2007). Age differences in resistence to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1531–1543. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Shiyko MP, Li R, Li Y, & Dierker L (2012). A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psychological Methods, 17, 61–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropf FC, Lee SH, Verweij RM, Stulp G, van der Most PJ, de Vlaming R, & Mills MC (2017). Hidden heritability due to heterogeneity across seven populations. Nature Human Behavior, 1, 757–765. 10.1038/s41562-017-0195-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Cope LM, Burmeister M, Zucker RA, & Heitzeg MM (2018). Pathways to youth behavior: the role of genetic, neural, & behavioral markers. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28, 26–39. 10.1111/jora.12341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Schlomer GL, & Hicks BM (2018). A developmental perspective on the genetic basis of alcohol use disorder. In Fitzgerald HE & Puttler LI (Eds.), Alcohol Use Disorders: A Developmental Science Approach to Etiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Villafuerete S, Heitzeg MM, Burmeister M, & Zucker RA (2016). Susceptibility effects of GABA receptor subunit alpha-2 (GABRA2) variants and parental monitoring on externalizing behavior trajectories: risk and protection conveyed by the minor allele. Development and Psychopathology, 28, 15–26. 10.1017/S0954579415000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Villafuerete S, Heitzeg MM, Burmeister M, & Zucker RA (2017). Beyond risk: prospective effects of GABA receptor subunit alpha-2 (GABRA2) x positive peer involvement on adolescent behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 711–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Villafuerete S, Heitzeg MM, Burmeister M, & Zucker RA (2014). Rule breaking mediates the developmental association between GABRA2 and adolescent substance use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 1372–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, Helm JL, Castro-Schilo L, Pluess M, & Belsky J (2012). Distinguishing ordinal and disordinal interactions. Psychological Methods, 17, 615–622. 10.1037/a0030003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]