Abstract

The incorporation of fluorinated groups into peptides significantly affects their biophysical properties. We report herein the synthesis of Fmoc-protected trifluoromethylthiolated tyrosine (CF3S-Tyr) and tryptophan (CF3S-Trp) analogues on a gram scale (77–93% yield) and demonstrate their use as highly hydrophobic fluorinated building blocks for peptide chemistry. The developed methodology was successfully applied to the late-stage regioselective trifluoromethylthiolation of Trp residues in short peptides (66–80% yield) and the synthesis of various CF3S-analogues of biologically active monoamines. To prove the concept, Fmoc-(CF3S)Tyr and -Trp were incorporated into the endomorphin-1 chain (EM-1) and into model tripeptides by solid-phase peptide synthesis. A remarkable enhancement of the local hydrophobicity of the trifluoromethylthiolated peptides was quantified by the chromatographic hydrophobicity index determination method, demonstrating the high potential of CF3S-containing amino acids for the rational design of bioactive peptides.

Introduction

The introduction of fluorine atoms into biomolecules has become a well-established strategy in drug development, as they can be used to favorably improve or modulate their physicochemical and biological properties.1 This approach is now widely exploited in the pharmaceutical industry, with 20–25% of marketed drugs containing at least one fluorine atom.2 Concurrently, peptides have emerged as a unique class of therapeutic agents in recent years. Over the past decade, their development has steadily increased, and therapeutic peptides now account for a significant portion of the pharmaceutical market.3 Moreover, tailor-made amino acids are becoming privileged scaffolds even in small-molecule drugs (which account for over 30% of pharmaceuticals).4 These paradigm shifts in medicinal chemistry call for further efforts to advance the synthesis of diverse fluorinated amino acids (F-AAs) for expanding the peptide design toolbox.5

In particular, the incorporation of F-AAs into peptides is a powerful tool for modulating various parameters, such as local hydrophobicity,6 pKa values of proximal functionalities,1b membrane permeability,7 metabolic stability,8 and inducing conformational constraints and self-assembly properties.9 Furthermore, fluorine atoms are used as highly sensitive probes for 19F NMR spectroscopy in biological media.9b,10 The most commonly investigated F-AAs contain either a fluorine atom or the CF3 group.11 However, other fluorinated groups, especially motifs bearing chalcogen atoms, remain underexplored in the context of amino acid chemistry.12 Among them, the trifluoromethylthio group (CF3S) is of particular interest as it has one of the highest lipophilicity parameters (Hansch-Leo parameter; π = 1.44),13 a strong electron-withdrawing effect (Hammett constant σm = 0.40, σp = 0.50),14 and a favorable pharmacological profile.15 Therefore, the synthesis of trifluoromethylsulfanylated amino acids (CF3S-AAs) and their incorporation into peptides appears to be a promising strategy to improve their physicochemical properties. In particular, the local hydrophobicity and membrane permeability could be significantly increased, improving the drug profile of the peptides.15,16

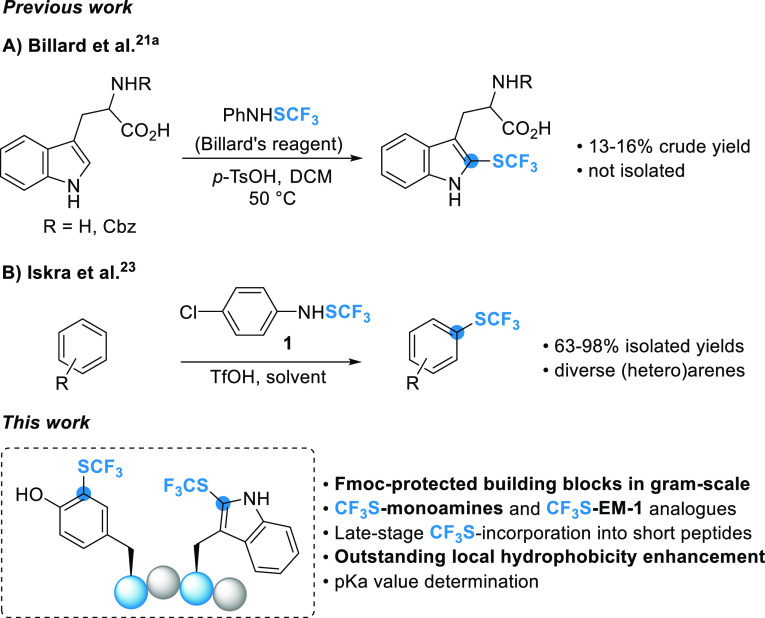

Most of the CF3S-AAs reported so far involve the aliphatic AAs, in particular, the trifluoromethylcysteine (TfmCys)16 and trifluoromethionine (TFM) analogues.17 They proved to be useful as sensitive 19F NMR reporters to probe protein–protein interactions (PPIs),10a as well as for their ability to enhance the local hydrophobicity of model peptides.6b A CF3S-cysteine (CF3S-Cys) analogue was also prepared by direct trifluoromethylthiolation of the corresponding thiol.18 Although there are numerous developed methods15a,16,19 and a plethora of shelf-stable and efficient reagents20 for aromatic trifluoromethylthiolation, the synthesis of aromatic CF3S-containing amino acids (CF3S-AAs) is still in its infancy and has been very scarcely reported to date. A few years ago, Billard and co-workers demonstrated the reactivity of various substituted indoles toward electrophilic trifluoromethylthiolation using their first- and second-generation trifluoromethanesulfenamide reagents.21 While the reaction was effective in introducing the CF3S group at the C2-position of unprotected indole propionic acid and tryptamine, very limited conversion (ca. 15%) was observed with Cbz-protected and unprotected Trp residues, and the desired products were not isolated (Scheme 1A).21a Nevertheless, the reaction conditions proved to be sensitive to the nature of the aromatic ring and are mainly limited to electron-rich aromatic compounds. Very recently, the synthesis of p-SCF3 phenylalanine (Phe) through a photoredox-mediated Ni-catalyzed trifluoromethylthiolation pathway was reported.22 To the best of our knowledge, CF3S incorporation into tyrosine derivatives has not been reported so far.

Scheme 1. Previous Reports on Direct Aromatic Trifluoromethylthiolation of Trp Derivatives or (Hetero)arenes Using the Trifluoromethanesulfenamide Reagents and Our Work Reported Herein.

As the demand for original fluorinated compounds continues to increase, the development of robust methods that allow efficient access to aromatic CF3S-AAs on a gram scale is of great importance. We have previously demonstrated that the p-chloro analogue 1 of the first-generation Billard’s21 reagent is more stable and promotes efficient electrophilic Friedel-Crafts trifluoromethylthiolation of diverse (hetero)arenes (Scheme 1B).23 Herein, we have investigated the Friedel-Crafts trifluoromethylthiolation with reagent 1 for the preparation of a series of aromatic CF3S-AAs (Scheme 1). We first report the synthesis of trifluoromethylthiolated tryptophan (CF3S-Trp) and tyrosine (CF3S-Tyr) amino acids, as well as their related monoamine analogues, such as trace amines and catecholamines. As an extension, the feasibility of the late-stage functionalization (LSF) was investigated on a series of Trp- and/or Tyr-containing short peptides. In addition, solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) synthesis of fluorinated analogues of the opioid agonist endomorphin-1 (EM-1) was performed using the ready-to-use Fmoc-protected CF3S-Trp and CF3S-Tyr building blocks. Finally, we report a significant enhancement of the local hydrophobicity and acidity originating from the CF3S group.

Results and Discussion

The electrophilic trifluoromethylthiolation reaction was first studied on tryptophan derivatives 2a–c (Table 1).

Table 1. Trifluoromethylthiolation of Tryptophan Derivatives 2a–c.

| entry | substrate | acid | conditions | 3/4 ratioa | yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2a | TsOH | A, 24 h | only 3a | 29 |

| 2c | 2a | TfOH | A, 24 h | 14:1 | 71 |

| 3 | 2a | TfOH | A, 24 h | 2:1 | 92 |

| 4 | 2a | TfOH | B, 6 h | only 4a | 90 |

| 5 | 2a | BF3·OEt2 | A, 24 h | 2.1:1 | 44 |

| 6 | 2a | BF3·OEt2 | B, 24 h | 1:2.2 | 58 |

| 7 | 2a | BF3·OEt2 | B, 48 h | 1:2.7 | 73 |

| 8d | 2a | BF3·OEt2 | B, 48 h | only 4a | 78 |

| 9 | 2b | BF3·OEt2 | B, 24 h | only 4b | 84 |

| 10e | 2b | BF3·OEt2 | B, 24 h | only 4b | 93 |

| 11 | 2c | TfOH | A, 30 min | only 4c | 96 |

PG-Trp-OR 2a–c (0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv), ArNHSCF31 (1.2 equiv), acid (2.5 equiv), conditions A (DCM; 1 mL, 0.1 M; rt) or conditions B (DCE; 1 mL, 0.1 M; 50 °C), 0.5–48 h. 3vs4 ratios determined by 19F NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

Isolated yield after purification of 3 and 4 or the inseparable mixture thereof.

TfOH (1.0 equiv).

BF3·OEt2 (2 × 2.5 equiv, second addition after 24 h).

Reaction performed on a gram scale (4.0 mmol).

The Fmoc-protecting group was selected to provide direct access to readily available building blocks for SPPS. In addition, the Fmoc group is known to tolerate the general acidic conditions used in our previous report.23 Trifluoromethylthiolation was first attempted on Fmoc-Trp-OEt 2a by applying the conditions of Billard et al.(21a) with TsOH (2.5 equiv) as an activator in DCM at rt (conditions A) (Table 1, entry 1). Instead of the expected product 4a, the formation of CF3S-hexahydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole 3a was observed in a low yield (29%) as a separable ca. 1:1 mixture of endo-cis and exo-cis diastereomers (see the Supporting Information for structural elucidation).24 The formation of the intermediate compound 3a is consistent with the previously reported cascade trifluoromethylthiolation-cyclization of N-protected tryptamines.25 Similar to Qing et al.,25a we observed in the AA-series that 3a undergoes ring opening after a prolonged time in acidic media, yielding the expected CF3S-Trp 4a. To increase the activation of the electrophile and the rate of the ring-opening process, we decided to replace TsOH with a stronger acid, namely, triflic acid (TfOH). The use of only 1.0 equiv of TfOH resulted in an inseparable 14:1 mixture of 3a and 4a in a 71% yield (Table 1, entry 2). Addition of TfOH in excess (2.5 equiv) increased both the selectivity for product 4a (3a/4a = ca. 2:1) and the isolated yield of 3a and 4a (92%) (Table 1, entry 3). Increasing the reaction temperature to 50 °C in DCE (conditions B) allowed the exclusive formation of 4a in a 90% isolated yield in a shorter reaction time (Table 1, entry 4). The reaction also proved effective under Lewis acid activation. An initial experiment with BF3·OEt2 under conditions A gave a mixture of 3a and 4a in a ratio of 2.1:1 (Table 1, entry 5). Application of conditions B resulted in an opposite 1:2.2 ratio of 3a/4a (Table 1, entry 6). Increasing the reaction time to 48 h improved the yield but had a limited effect on the ring-opening step (Table 1, entry 7). Finally, a second addition of 2.5 equiv of BF3·OEt2 after 24 h proved effective for complete conversion to 4a (Table 1, entry 8). It is noteworthy that trifluoromethylthiolation under Lewis acid activation gave a cleaner conversion compared to TfOH activation. To gain direct access to ready-to-use building blocks for SPPS, we decided to investigate the trifluoromethylthiolation of Fmoc-Trp-OH 2b. Compared to the ester series (Table 1, entry 7), the reaction on Fmoc-protected acid 2b using 2.5 equiv of BF3·OEt2 under conditions B resulted in a complete conversion to the expected CF3S-Trp 4b after 24 h (Table 1, entry 9). With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, the trifluoromethylthiolation of 2b was carried out on a gram scale, yielding approximately 2 g of the desired product 4b (93% yield, Table 1, entry 10). The enantiopurity of 4b was analyzed by chiral HPLC, which showed no epimerization at the Cα position (see the Supporting Information, Chapter 5). Next, we investigated the effect of the N-protection on the reaction outcome. Trifluoromethylthiolation starting from N-unprotected ethyl ester 2c under TfOH activation proceeded much faster (30 min) compared to 2a (Table 1, entry 3), and the corresponding CF3S-Trp 4c was isolated in a 96% yield (Table 1, entry 11). This result highlights the key role of the nature of the amino group in the ring-opening step.

We then decided to extend the scope of the reaction to biologically important tryptamine-based trace amines (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of CF3S-Tryptamine Derivatives 4d–i (Isolated Yields).

2d–i (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), ArNHSCF31 (1.2 equiv), acid (2.5 equiv; in parentheses), conditions A (DCM; 1 mL, 0.1 M; rt), 16 h. ArNHSCF31 (1.05 equiv); ratio determined by 19F NMR of the crude product. bArNHSCF31 (1.05 equiv), BF3·OEt2 (5.0 equiv), 24 h. cconditions B (DCE; 1 mL, 0.1 M; 50 °C).

Several CF3S-tryptamine derivatives have already been described in the literature using the trifluoromethanesulfenamide reagent in the presence of TsOH.25a N-substituted tryptamines favored the formation of the CF3S-pyrroloindoline intermediates,25a while in the case of the unprotected tryptamine 2f, only the corresponding CF3S-tryptamine 4f has been isolated in very low yield.21a Herein, the use of reagent 1 in the presence of TfOH allowed us to selectively obtain Fmoc-protected and N-methyl tryptamine analogues 4d and 4e (90 and 77% isolated yields, respectively), and to significantly improve the isolated yield (92%) of the unprotected CF3S-tryptamine 4f (Scheme 2). CF3S introduction was then attempted on serotonin and melatonin, two important biologically relevant representatives of the C5-functionalized tryptamine derivatives. TfOH activation of Fmoc- protected serotonin 2g resulted in a ca. 3:1 mixture of mono-SCF3 (at the C2-indole position) and bis-SCF3 (at the C2- and C4-indole positions) products. We assumed that the formation of the bis-SCF3 compound arises due to the presence of the hydroxyl group at the C5-position, which causes a considerable increase in the electron density of the indole. Therefore, we decided to decrease the activation of the indole by protecting the free hydroxyl with a benzyl group (see Table S1 for optimization data). In addition, the BF3·OEt2 activation was preferred to avoid the possible deprotection of the benzyl group by TfOH. Under these conditions, only the mono-SCF3 serotonin derivative 4h was obtained in high yield (Scheme 2). When applied to melatonin 2i, which has a methoxy group at the C5-indole position, these conditions gave the expected mono-SCF3 melatonin 4i in a 66% yield (Scheme 2).

We further explored the scope and limitations of our method with less electron-rich aromatic tyrosine (Tyr) derivatives (Table 2).

Table 2. Trifluoromethylthiolation of Tyrosine Derivatives 5a–c.

| entry | substrate | acid | conversion (%)a | yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5a | BF3·OEt2 | 7 (25)c | n.d. |

| 2 | 5a | TfOH | 93 | n.d. |

| 3d | 5a | TfOH | >99 | 6a (79) |

| 4d,e | 5a | TfOH | >99 | 6a (77) |

| 5f | 5b | TfOH | >99 | 6b (93) |

| 6 | 5c | TfOH | <1 | n.d. |

PG-Tyr-OR 5a–c (0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv), ArNHSCF31 (1.2 equiv), acid (2.5 equiv), conditions A (DCM; 1 mL, 0.1 M; rt). Conversion to 6a determined by 1H NMR analysis (DMSO-d6) of the crude reaction mixture.

n.d.: not determined.

Conditions B (DCE; 1 mL, 0.1 M; 50 °C), 24 h.

1.5 equiv of ArNHSCF31.

Reaction performed on a gram scale (4.0 mmol).

ArNHSCF31 (2.5 equiv), TfOH (2 × 2.5 equiv, second addition after 18 h).

To access readily available building blocks for SPPS, Fmoc-Tyr-OH 5a was first subjected to the previously optimized conditions for Trp. The trifluoromethylthiolation of 5a using BF3·OEt2 at rt (conditions A) and at 50 °C (conditions B) proceeded with a very low conversion (Table 2, entry 1). These results were attributed to the lower reactivity of the phenolic moiety compared to the indole. Replacing BF3·OEt2 with TfOH significantly improved the reaction conversion (Table 2, entry 2). Moreover, increasing the amount of reagent 1 to 1.5 equiv resulted in complete conversion, and Fmoc-protected CF3S-Tyr 6a was isolated in a 79% yield (Table 2, entry 3). A gram-scale trifluoromethylthiolation of 5a yielded ca. 1.6 g of the enantiomerically pure Fmoc-protected building block 6a in 77% isolated yield (Table 2, entry 4). It is worthwhile to note that the phenol group of this amino acid should be orthogonally protected by a t-butyl group for incorporation into longer peptide sequences. In the case of the Fmoc-Tyr-OMe substrate 5b, harsher conditions (2.5 equiv of 1, 2 × 2.5 equiv of TfOH) were required to achieve quantitative CF3S-incorporation and the ester analogue 6b was isolated in an excellent yield of 93% (Table 2, entry 5). In contrast to the observation in the Trp series, the trifluoromethylthiolation of 5c without Fmoc protection of the N-terminus did not proceed (Table 2, entry 6).

Encouraged by the novel reactivity of tyrosine-based substrates, we investigated the CF3S-functionalization of tyramine, dopamine, and DOPA derivatives 5d–i (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of CF3S-Tyramine, -Dopamine, and -DOPA Derivatives 6d–i.

Substrate 5d–i (0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv), ArNHSCF31 (0.25 mmol, 2.5 equiv), TfOH (2 × 2.5 equiv, second addition after 18 h), conditions A (DCM, 0.1 M, rt), 24 h; isolated yields in parentheses. 0.20 mmol scale (1.0 equiv). bArNHSCF31 (1.1 equiv), TfOH (2.5 equiv), overnight. cArNHSCF31 (1.2 equiv), BF3·OEt2 (5.0 equiv), conditions B (DCE; 1 mL, 0.1 M; 50 °C), 24 h.

As with the Tyr series (see Table 2, entry 5), harsher conditions had to be applied to obtain Fmoc-protected and unprotected CF3S-tyramines 6d and 6e in good yields (Scheme 3). In the case of the dopamine and DOPA analogues, standard conditions (1.2 equiv of 1, 2.5 equiv of TfOH) are sufficient to achieve quantitative CF3S incorporation in the electron-rich catechol motif. However, a change in regioselectivity was observed because of the para-directing effect of the additional hydroxyl group (Scheme 3). This allowed straightforward synthesis of Fmoc-protected and unprotected CF3S-dopamines 6f and 6g as single regioisomers in 70 and 68% yields, respectively (Scheme 3). When applied to Fmoc-protected DOPA 5h, the reaction gave the corresponding 2–SCF3 derivative 6h. Purification of 6h by flash chromatography showed that the product was not stable on silica after a prolonged time. Nevertheless, 6h could be isolated in satisfactory purity only by acidic workup. On the other hand, quantitative conversion of Fmoc-DOPA-OBn 5i could be achieved under BF3·OEt2 activation (5.0 equiv, conditions B) to afford the corresponding 6i in a 77% yield (Scheme 3). The scope of the method was then tentatively extended to phenylalanine substrates (Phe), but no reaction occurred. The reactivity of the phenyl ring of Phe is low, and trifluoromethylthiolation occurs on the aniline ring of reagent 1. Such limitations were also demonstrated in our previous report on the trifluoromethylthiolation of arenes.23

LSF is a powerful diversification tool for the synthesis of peptides featuring unnatural AAs with modified properties or biological activity. Because of its high reactivity, the Trp residue is often targeted for such modifications.26 We therefore investigated the feasibility of the method for LSF on a series of Trp- and/or Tyr-containing short peptides (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Late-Stage Trifluoromethylthiolation of Trp Residue-Containing Peptides 7a–g.

Peptide 7a–g (0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv), ArNHSCF31 (1.2 equiv). acid (2.5 equiv), conditions A (DCM; 1 mL, 0.1 M; rt) or conditions B (DCE; 1 mL, 0.1 M; 50 °C), overnight. BF3·OEt2 (2 × 2.5 equiv). b48 h. cArNHSCF31 (1.05 equiv). dRatios estimated by 19F NMR analysis. eArNHSCF31 (2.2 equiv), BF3·OEt2 (2 × 5.0 equiv), 48 h. fTFA·EM-1 (10 mg scale, 0.014 mmol, 1.0 equiv), BF3·OEt2 (20 equiv), DCM (0.05 M), rt, 24 h; Conversion determined by UPLC-MS analysis.

Late-stage trifluoromethylthiolation was first investigated on a series of peptides with a Trp residue at the N- or C-terminal position (7a–b and 7c–d) and in the middle position of the peptide chain (7e). LSF of Fmoc-protected peptides was carried out using BF3·OEt2 activation under the optimized conditions found for the Fmoc-Trp ester 2a (see Table 1, entry 8). CF3S-peptide 8a with the Fmoc-Trp residue at the N-terminal position was obtained in a 74% yield after 48 h (Scheme 4). LSF of the peptide 7b, with the free N-terminal amino group, was first performed under TfOH activation, which was the condition successfully used for the unprotected Trp ester 2c (see Table 1, Entry 11). However, the reaction resulted in a complex reaction mixture. Upon BF3·OEt2 activation at room temperature, a clean conversion was observed, and peptide 8b was obtained in an 80% yield. Trifluoromethylthiolation of peptide 7c with the Trp residue at the C-terminal position gave the corresponding dipeptide 8c in a 74% yield after 16 h. It appears that the reaction proceeds much faster when the Trp residue is at the C-terminal position. LSF of Fmoc-protected peptides also worked efficiently under TfOH activation. Peptides 8d and 8e, having the Trp residue at the C-terminus and in the middle position of the peptide chain, were obtained in good yields (Scheme 4). Because of the difference in kinetics observed with peptides 8a and 8c, we decided to investigate the regioselectivity of the trifluoromethylthiolation on the Trp–Trp dipeptide 7f. CF3S incorporation under TfOH activation gave a mixture of mono- and bis-SCF3 dipeptide 8f in a ratio of ca. 2:1 (Scheme 4). Therefore, we have chosen the reaction conditions to selectively obtain the bis-SCF3 dipeptide 8f. Under TfOH activation, the reaction gave a complex mixture, whereas, under BF3·OEt2 activation, the dipeptide 8f was isolated in a 71% yield (Scheme 4). The chemoselectivity aspect of the late-stage SCF3 incorporation, based on the difference in reactivity between Trp and Tyr residues, has also been investigated. Complete chemoselectivity in favor of the Trp residue was observed for the model dipeptide 7g. The reaction resulted in a quantitative conversion when 1.05 equiv of 1 was used and peptide 8g was obtained in a 78% yield (Scheme 4). A model Ala-Tyr dipeptide 7h was also tested for selective LSF of the Tyr residue. Unfortunately, the required harsher conditions (as in Table 2, entry 5) were not tolerated by the peptide substrate, resulting in a complex reaction mixture. To highlight the generalization of LS trifluoromethylthiolation to longer peptides of interest, we investigated the reaction on the analgesic peptide endomorphin-1 (EM-1). This substrate was selected as a relevant biologically active peptide target because it contains both Tyr and Trp residues. As expected, by applying the LSF conditions using a large excess of BF3·OEt2 (20 equiv), only the formation of (CF3S)Trp-EM-1 was observed in 69% conversion, as determined by UPLC-MS and NMR analysis (Scheme 4).

As a complementary strategy to LSF, we decided to investigate the synthesis of the (CF3S)Trp-EM-1 analogue by SPPS. The (CF3S)Trp-EM-1 was obtained in a 26% yield using standard protocols and coupling reagents (HATU/DIPEA) (Table 3).

Table 3. SPPS of EM-1 Analogues.

| peptide | yield (%) | trans vs cisa | tR (min)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| EM-1 | 24 | 66:34 | 8.1 |

| (CF3S)Trp-EM-1 | 26 | 71:29 | 10.9 |

| (CF3S)Tyr-EM-1 | 19 | 71:29 | 11.6 |

Conformer ratio of the peptidyl-prolyl amide bond determined by 1H and/or 19F NMR spectroscopy in MeOD-d3 (see the Supporting Information, Chapter 4.2.).

RP-HPLC analysis (20% → 60% MeCN + 0.1% TFA in H2O + 0.1% TFA).

Compared to endomorphin-1 (EM-1), the two fluorinated analogues were obtained in comparable yields and have similar cis/trans ratios of the peptidyl-prolyl amide bond. These results indicate that Fmoc-(CF3S)Trp-OH 4b and Fmoc-(CF3S)Tyr-OH 6a are suitable building blocks for SPPS and that their incorporation into EM-1 does not significantly affect the peptide conformation (Table 3). Interestingly, the retention times (tR) determined by reverse-phase HPLC were significantly longer for both CF3S-containing peptides compared to the parent EM-1 (ca. 3 min). This result supports the expected enhancement of local hydrophobicity. To achieve an accurate determination of the local hydrophobicity enhancement imparted by the CF3S group in a peptide context, we decided to measure the chromatographic hydrophobicity indexes of a series of four H2N-Ala-AA-Leu-OH tripeptides containing the respective Tyr, Trp, and (CF3S)Tyr or the (CF3S)Trp residue at the AA position (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biophysical property evaluation. (A) HI for non-fluorinated tripeptides 9–10 and the CF3S-tripeptides 11–12; (B) phenolic moiety pKa values of tyramine 5e and CF3S-tyramine 6e triflate salts in H2O/D2O = 90:10 by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

The hydrophobicity index (HI) shift ΔHI (HI(CF3S)AA – HIAA) is an assessment of the contribution of the CF3S substituent to the increase in local hydrophobicity. This method, developed by Valkó et al.,27 has already been successfully applied to measure the increased local hydrophobicity of peptides containing fluorinated AAs.6b,28 This short peptide sequence was chosen to prevent the formation of secondary structures that could affect hydrophobicity (see the Supporting Information, Chapter 6, for details). As shown in Figure 1, CF3S-containing peptides 11 and 12 have significantly higher HI compared to their non-fluorinated counterparts 9 and 10. These results corroborate the significant increase in RP-HPLC retention times measured with fluorinated EM-1 analogues. As observed in the non-fluorinated series (peptides 9 and 10), the (CF3S)Trp-containing peptide 12 exhibits a higher HI than the (CF3S)Tyr peptide 11. It is noteworthy that the replacement of the Tyr residue with its CF3S-Tyr analogue provides a higher local enhancement of the hydrophobicity (ΔHI = HI(CF3S)Tyr – HITyrca. 12 units) compared to the Trp series (ΔHI = HI(CF3S)Trp – HITrpca. 8 units). These results showed that (CF3S)Tyr and (CF3S)Trp are the most hydrophobic AAs determined so far by this method.6b

Finally, we assessed the influence of the CF3S group on the acidity of the vicinal phenol function in a simplified tyramine model carrying an ortho CF3S. This functionality is highly important for peptide/protein active site interactions. The pKa values of the tyramine 5e and the CF3S-tyramine 6e triflate salts were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy in H2O/D2O 90:10 (see the Supporting Information, Chapter 7, for more details).29 It is noteworthy that in the case of CF3S-tyramine 6e, the pKa value could also be determined by 19F NMR spectroscopy. As expected, the CF3S has a major impact on the pKa value with a 100-fold increase of the acidity of the vicinal hydroxyl group (pKa,(CF3S)Tyr = 8.1, pKa,Tyr = 9.9, Figure 1). The values of the pKa of CF3S- and CF3-phenols are comparable (8.2530 and 8.4231 for 2-CF3 phenols in H2O), which is consistent with their similar electron-withdrawing nature (Hammet substituent constant: CF3: σm = 0.43, σp = 0.54; CF3S: σm = 0.40, σp = 0.50).14

Conclusions

In this work, we have developed an efficient method for the aromatic trifluoromethylthiolation of tryptophan and tyrosine residues. Reactions were carried out using the electrophilic trifluoromethanesulfenamide reagent 1 in the presence of TfOH or BF3·OEt2 as activating acids. Several trifluoromethylthiolated tryptophan analogues (CF3S-Trp) and their biologically active monoamine derivatives, protected or unprotected, were prepared in high yields following a thorough methodological study. We also demonstrated the scope of our method by preparing the Fmoc-(CF3S)Trp-OH 4b and Fmoc-(CF3S)Tyr-OH 6a building blocks that are ready-to-use for SPPS on a gram scale. The late-stage CF3S-functionalization of short peptides showed total regioselectivity in favor of the Trp residue over other aromatic side chains and was successfully applied to the opioid agonist endomorphin-1 (EM-1). The synthesis of two trifluoromethylthiolated analogues of EM-1 was achieved by SPPS using standard protocols and Fmoc-protected building blocks 4b and 6a. Finally, we investigated the effect of the incorporation of the CF3S group into aromatic Trp and Tyr residues on the physicochemical properties of the peptide framework. We demonstrated that the CF3S-containing peptides exhibited a significant enhancement of the local hydrophobicity compared with their non-fluorinated counterparts. In this regard, the CF3S-Trp is more hydrophobic than the CF3S-Tyr. Moreover, the incorporation of a CF3S group adjacent to the phenol ring of tyramine significantly increases its acidity. Because of the key role played by Trp and Tyr residues in protein–protein interactions and the great biological importance of Trp- and Tyr-derived monoamines, the reported CF3S-containing analogues represent a new class of compounds endowed with unique properties.32 Their ability to dramatically increase local hydrophobicity and modulate the pKa of adjacent functional groups makes them very attractive for medicinal chemistry applications. The ease of implementation of the reported trifluoromethylthiolation should inspire further developments in the design of bioactive peptides.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) (P1-0134 Research Core Funding Grant and Young Researcher Grant to J.G.). We thank the Eutopia and CY Initiative of Excellence (grant Investissements d’Avenir, ANR-16-IDEX-0008). Additionally, J.G. thanks the Milan Lenarčič Scholarship (University of Ljubljana) for financially supporting his research visit.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.3c01373.

Experimental procedures, characterization data, copies of NMR spectra for all new compounds, HPLC traces of endomorphin-1 analogues, HPLC enantiopurity analysis of compounds 4b and 6a, HI determinations, and pKa determinations of compounds 5e and 6e (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Grygorenko O. O.; Melnykov K. P.; Holovach S.; Demchuk O. Fluorinated Cycloalkyl Building Blocks for Drug Discovery. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200365 10.1002/cmdc.202200365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gillis E. P.; Eastman K. J.; Hill M. D.; Donnelly D. J.; Meanwell N. A. Applications of Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8315–8359. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Meanwell N. A. Fluorine and Fluorinated Motifs in the Design and Application of Bioisosteres for Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5822–5880. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Johnson B. M.; Shu Y.-Z.; Zhuo X.; Meanwell N. A. Metabolic and Pharmaceutical Aspects of Fluorinated Compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 6315–6386. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Nair A. S.; Singh A. K.; Kumar A.; Kumar S.; Sukumaran S.; Koyiparambath V. P.; Pappachen L. K.; Rangarajan T. M.; Kim H.; Mathew B. FDA-Approved Trifluoromethyl Group-Containing Drugs: A Review of 20 Years. Processes 2022, 10, 2054. 10.3390/pr10102054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Inoue M.; Sumii Y.; Shibata N. Contribution of Organofluorine Compounds to Pharmaceuticals. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10633–10640. 10.1021/acsomega.0c00830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Han J.; Remete A. M.; Dobson L. S.; Kiss L.; Izawa K.; Moriwaki H.; Soloshonok V. A.; O’Hagan D. Next Generation Organofluorine Containing Blockbuster Drugs. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 239, 109639. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c He J.; Li Z.; Dhawan G.; Zhang W.; Sorochinsky A. E.; Butler G.; Soloshonok V. A.; Han J. Fluorine-Containing Drugs Approved by the FDA in 2021. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107578. 10.1016/j.cclet.2022.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Wang N.; Mei H.; Dhawan G.; Zhang W.; Han J.; Soloshonok V. A. New Approved Drugs Appearing in the Pharmaceutical Market in 2022 Featuring Fragments of Tailor-Made Amino Acids and Fluorine. Molecules 2023, 28, 3651. 10.3390/molecules28093651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang L.; Wang N.; Zhang W.; Cheng X.; Yan Z.; Shao G.; Wang X.; Wang R.; Fu C. Therapeutic Peptides: Current Applications and Future Directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 48. 10.1038/s41392-022-00904-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Muttenthaler M.; King G. F.; Adams D. J.; Alewood P. F. Trends in peptide drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 309–325. 10.1038/s41573-020-00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cabri W.; Cantelmi P.; Corbisiero D.; Fantoni T.; Ferrazzano L.; Martelli G.; Mattellone A.; Tolomelli A. Therapeutic Peptides Targeting PPI in Clinical Development: Overview, Mechanism of Action and Perspectives. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 697586. 10.3389/fmolb.2021.697586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lau J. L.; Dunn M. K. Therapeutic Peptides: Historical Perspectives, Current Development Trends, and Future Directions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 2700–2707. 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Henninot A.; Collins J. C.; Nuss J. M. The Current State of Peptide Drug Discovery: Back to the Future?. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 1382–1414. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Liu A.; Han J.; Nakano A.; Konno H.; Moriwaki H.; Abe H.; Izawa K.; Soloshonok V. A. New Pharmaceuticals Approved by FDA in 2020: Small-Molecule Drugs Derived from Amino Acids and Related Compounds. Chirality 2022, 34, 86–103. 10.1002/chir.23376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Han J.; Konno H.; Sato T.; Soloshonok V. A.; Izawa K. Tailor-Made Amino Acids in the Design of Small-Molecule Blockbuster Drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 220, 113448. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang Q.; Han J.; Sorochinsky A.; Landa A.; Butler G.; Soloshonok V. A. The Latest FDA-Approved Pharmaceuticals Containing Fragments of Tailor-Made Amino Acids and Fluorine. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 999. 10.3390/ph15080999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mei H.; Han J.; White S.; Graham D. J.; Izawa K.; Sato T.; Fustero S.; Meanwell N. A.; Soloshonok V. A. Tailor-Made Amino Acids and Fluorinated Motifs as Prominent Traits in Modern Pharmaceuticals. Chem.—Eur. J. 2020, 26, 11349–11390. 10.1002/chem.202000617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mei H.; Han J.; Klika K. D.; Izawa K.; Sato T.; Meanwell N. A.; Soloshonok V. A. Applications of Fluorine-Containing Amino Acids for Drug Design. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 186, 111826. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hohmann T.; Chowdhary S.; Ataka K.; Er J.; Dreyhsig G. H.; Heberle J.; Koksch B. Introducing Aliphatic Fluoropeptides: Perspectives on Folding Properties, Membrane Partition and Proteolytic Stability. Chem.—Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202203860 10.1002/chem.202203860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gadais C.; Devillers E.; Gasparik V.; Chelain E.; Pytkowicz J.; Brigaud T. Probing the Outstanding Local Hydrophobicity Increases in Peptide Sequences Induced by Incorporation of Trifluoromethylated Amino Acids. ChemBioChem 2018, 19, 1026–1030. 10.1002/cbic.201800088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo A. D.; Hoang H. N.; Lim J.; Mak J. Y. W.; Fairlie D. P. Tuning Electrostatic and Hydrophobic Surfaces of Aromatic Rings to Enhance Membrane Association and Cell Uptake of Peptides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202203995 10.1002/anie.202203995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Huhmann S.; Koksch B. Fine-Tuning the Proteolytic Stability of Peptides with Fluorinated Amino Acids. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2018, 2018, 3667–3679. 10.1002/ejoc.201800803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Devillers E.; Chelain E.; Dalvit C.; Brigaud T.; Pytkowicz J. (R)-α-Trifluoromethylalanine as a 19F NMR Probe for the Monitoring of Protease Digestion of Peptides. ChemBioChem 2022, 23, e202100470 10.1002/cbic.202100470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chowdhary S.; Schmidt R. F.; Sahoo A. K.; tom Dieck T.; Hohmann T.; Schade B.; Brademann-Jock K.; Thünemann A. F.; Netz R. R.; Gradzielski M.; Koksch B. Rational Design of Amphiphilic Fluorinated Peptides: Evaluation of Self-Assembly Properties and Hydrogel Formation. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 10176–10189. 10.1039/d2nr01648f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sloand J. N.; Miller M. A.; Medina S. H. Fluorinated Peptide Biomaterials. Pept. Sci. 2021, 113, e24184 10.1002/pep2.24184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tang Y.; Ghirlanda G.; Vaidehi N.; Kua J.; Mainz D. T.; Goddard W. A.; DeGrado W. F.; Tirrell D. A. Stabilization of Coiled-Coil Peptide Domains by Introduction of Trifluoroleucine. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 2790–2796. 10.1021/bi0022588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Tang Y.; Tirrell D. A. Biosynthesis of a Highly Stable Coiled-Coil Protein Containing Hexafluoroleucine in an Engineered Bacterial Host. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 11089–11090. 10.1021/ja016652k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wang P.; Fichera A.; Kumar K.; Tirrell D. A. Alternative Translations of a Single RNA Message: An Identity Switch of (2S,3R)-4,4,4-Trifluorovaline between Valine and Isoleucine Codons. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 3664–3666. 10.1002/anie.200454036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Bilgiçer B.; Fichera A.; Kumar K. A Coiled Coil with a Fluorous Core. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 4393–4399. 10.1021/ja002961j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Bilgiçer B.; Xing X.; Kumar K. Programmed Self-Sorting of Coiled Coils with Leucine and Hexafluoroleucine Cores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 11815–11816. 10.1021/ja016767o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Yoder N. C.; Kumar K. Fluorinated Amino Acids in Protein Design and Engineering. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002, 31, 335–341. 10.1039/b201097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Marsh E. N. G. Fluorinated Proteins: From Design and Synthesis to Structure and Stability. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2878–2886. 10.1021/ar500125m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Buer B. C.; Meagher J. L.; Stuckey J. A.; Marsh E. N. G. Structural Basis for the Enhanced Stability of Highly Fluorinated Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 4810–4815. 10.1073/pnas.1120112109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Marsh E. N. G.; Suzuki Y. Using 19F NMR to Probe Biological Interactions of Proteins and Peptides. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 1242–1250. 10.1021/cb500111u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gimenez D.; Phelan A.; Murphy C. D.; Cobb S. L. 19F NMR as a Tool in Chemical Biology. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 293–318. 10.3762/bjoc.17.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gronenborn A. M. Small, but powerful and attractive: 19F in biomolecular NMR. Structure 2022, 30, 6–14. 10.1016/j.str.2021.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Grage S. L.; Kara S.; Bordessa A.; Doan V.; Rizzolo F.; Putzu M.; Kubař T.; Papini A. M.; Chaume G.; Brigaud T.; Afonin S.; Ulrich A. S. Orthogonal 19F-Labeling for Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy Reveals the Conformation and Orientation of Short Peptaibols in Membranes. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24, 4328–4335. 10.1002/chem.201704307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhou M.; Feng Z.; Zhang X. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Fluorinated Amino Acids and Peptides. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 1434–1448. 10.1039/d2cc06787k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Moschner J.; Stulberg V.; Fernandes R.; Huhmann S.; Leppkes J.; Koksch B. Approaches to Obtaining Fluorinated α-Amino Acids. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10718–10801. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhang X.-X.; Gao Y.; Hu X.-S.; Ji C.-B.; Liu Y.-L.; Yu J.-S. Recent Advances in Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of Fluorinated α- and β-Amino Acids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 4763–4793. 10.1002/adsc.202000966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Brittain W. D. G.; Lloyd C. M.; Cobb S. L. Synthesis of Complex Unnatural Fluorine-Containing Amino Acids. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 239, 109630. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toulgoat F.; Liger F.; Billard T.. Chemistry of OCF3, SCF3, and SeCF3 Functional groups. In Organofluorine Chemistry: Synthesis, Modeling, and Applications; Szabó K., Selander N., Eds.; Wiley VCH, 2021; pp 49–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C.; Leo A.; Unger S. H.; Kim K. H.; Nikaitani D.; Lien E. J. Aromatic Substituent Constants for Structure-Activity Correlations. J. Med. Chem. 1973, 16, 1207–1216. 10.1021/jm00269a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C.; Leo A.; Taft R. W. A Survey of Hammett Substituent Constants and Resonance and Field Parameters. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 165–195. 10.1021/cr00002a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Xu X.-H.; Matsuzaki K.; Shibata N. Synthetic Methods for Compounds Having CF3–S Units on Carbon by Trifluoromethylation, Trifluoromethylthiolation, Triflylation, and Related Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 731–764. 10.1021/cr500193b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ghiazza C.; Billard T.; Dickson C.; Tlili A.; Gampe C. M. Chalcogen OCF3 Isosteres Modulate Drug Properties without Introducing Inherent Liabilities. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 1586–1589. 10.1002/cmdc.201900452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ge H.; Liu H.; Shen Q.. Introduction of Trifluoromethylthio Group into Organic Molecules. In Organofluorine Chemistry: Synthesis, Modeling, and Applications; Szabó K., Selander N., Eds.; Wiley VCH, 2021; pp 99–127. [Google Scholar]; b Toulgoat F.; Billard T.. Toward CF3S Group: From Trifluoromethylation of Sulfides to Direct Trifluoromethylthiolation. In Modern Synthesis Processes and Reactivity of Fluorinated Compounds; Groult H., Leroux F. R., Tressaud A., Eds.; Elsevier, 2017; pp 141–179. [Google Scholar]

- a Langlois B.; Montègre D.; Roidot N. Synthesis of S-trifluoromethyl-containing α-amino acids from sodiumtrifluoromethanesulfinate and dithio-amino acids. J. Fluorine Chem. 1994, 68, 63–66. 10.1016/0022-1139(93)02982-k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Gadais C.; Saraiva-Rosa N.; Chelain E.; Pytkowicz J.; Brigaud T. Tailored Approaches towards the Synthesis of L-S-(Trifluoromethyl)cysteine- and L-Trifluoromethionine-Containing Peptides. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2017, 2017, 246–251. 10.1002/ejoc.201601318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Capone S.; Kieltsch I.; Flögel O.; Lelais G.; Togni A.; Seebach D. ElectrophilicS-Trifluoromethylation of Cysteine Side Chains inα- andβ-Peptides: Isolation of Trifluoro-methylatedSandostatin(Octreotide) Derivatives. Helv. Chim. Acta 2008, 91, 2035–2056. 10.1002/hlca.200890217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Kieltsch I.; Eisenberger P.; Togni A. Mild Electrophilic Trifluoromethylation of Carbon- and Sulfur-Centered Nucleophiles by a Hypervalent Iodine(III)–CF3 Reagent. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 754–757. 10.1002/anie.200603497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zeng J.-L.; Chachignon H.; Ma J.-A.; Cahard D. Nucleophilic Trifluoromethylthiolation of Cyclic Sulfamidates: Access to Chiral β- and γ-SCF3 Amines and α-Amino Esters. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 1974–1977. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jereb M.; Dolenc D. Electrophilic Trifluoromethylthiolation of Thiols with Trifluoromethanesulfenamide. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 58292–58306. 10.1039/c5ra07316b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toulgoat F.; Alazet S.; Billard T. Direct Trifluoromethylthiolation Reactions: The “Renaissance” of an Old Concept. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2014, 2014, 2415–2428. 10.1002/ejoc.201301857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Xu C.; Wang S.; Shen Q. Recent Progress on Trifluoromethylthiolation of (Hetero)Aryl C–H Bonds with Electrophilic Trifluoromethylthiolating Reagents. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 6889–6899. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c01006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Shen Q. A. A Toolbox of Reagents for Trifluoromethylthiolation: From Serendipitous Findings to Rational Design. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 3359–3371. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c02777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liu H.; Ge H.; Shen Q.. Reagents for Direct Trifluoromethylthiolation. In Emerging Fluorinated Motifs: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications; Ma J.-A., Cahard D., Eds.; Wiley VCH, 2020; pp 309–341. [Google Scholar]

- a Ferry A.; Billard T.; Bacqué E.; Langlois B. R. Electrophilic Trifluoromethanesulfanylation of Indole Derivatives. J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 134, 160–163. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2011.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Glenadel Q.; Alazet S.; Billard T. First and Second Generation of Trifluoromethanesulfenamide Reagent: A Trifluoromethylthiolating Comparison. J. Fluorine Chem. 2015, 179, 89–95. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2015.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gravatt C. S.; Johannes J. W.; King E. R.; Ghosh A. Photoredox-Mediated, Nickel-Catalyzed Trifluoromethylthiolation of Aryl and Heteroaryl Iodides. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 8921–8927. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvat M.; Jereb M.; Iskra J. Diversification of Trifluoromethylthiolation of Aromatic Molecules with Derivatives of Trifluoromethanesulfenamide. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2018, 2018, 3837–3843. 10.1002/ejoc.201800551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crich D.; Banerjee A. Chemistry of the Hexahydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indoles: Configuration, Conformation, Reactivity, and Applications in Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 38, 151–161. 10.1002/chin.200722254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and references therein

- a Yang Y.; Jiang X.; Qing F.-L. Sequential Electrophilic Trifluoromethanesulfanylation–Cyclization of Tryptamine Derivatives: Synthesis of C(3)-Trifluoromethanesulfanylated Hexahydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indoles. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 7538–7547. 10.1021/jo3013385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Guo R.; Cai B.; Jin M. Y.; Mu H.; Wang J. Sulfide-Catalyzed Trifluoromethylthiolation-Cyclization of Tryptamine Derivatives. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2019, 8, 687–690. 10.1002/ajoc.201900068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Gruß H.; Sewald N. Late-Stage Diversification of Tryptophan-Derived Biomolecules. Chem.—Eur. J. 2020, 26, 5328–5340. 10.1002/chem.201903756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and references therein; b Kaplaneris N.; Puet A.; Kallert F.; Pöhlmann J.; Ackermann L. Late-stage C–H Functionalization of Tryptophan-Containing Peptides with Thianthrenium Salts: Conjugation and Ligation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216661 10.1002/anie.202216661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and references therein; c Hu J.-J.; He P.-Y.; Li Y.-M. Chemical Modifications of Tryptophan Residues in Peptides and Proteins. J. Pept. Sci. 2021, 27, e3286 10.1002/psc.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Valkó K.; Slégel P. New chromatographic hydrophobicity index (ϕ0) based on the slope and the intercept of the log k’ versus organic phase concentration plot. J. Chromatogr. A 1993, 631, 49–61. 10.1016/0021-9673(93)80506-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Valkó K.; Bevan C.; Reynolds D. Chromatographic Hydrophobicity Index by Fast-Gradient RP-HPLC: A High-Throughput Alternative to log P/log D. Anal. Chem. 1997, 69, 2022–2029. 10.1021/ac961242d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c For a recent application seeAng E.; Neustaeter H.; Spicer V.; Perreault H.; Krokhin O. Retention Time Prediction for Glycopeptides in Reversed-Phase Chromatography for Glycoproteomic Applications. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 13360–13366. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M.; Gadais C.; García-Pindado J.; Teixidó M.; Lensen N.; Chaume G.; Brigaud T. Trifluoromethylated proline analogues as efficient tools to enhance the hydrophobicity and to promote passive diffusion transport of the L-prolyl-L-leucyl glycinamide (PLG) tripeptide. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 14597–14602. 10.1039/c8ra02511h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezençon J.; Wittwer M. B.; Cutting B.; Smieško M.; Wagner B.; Kansy M.; Ernst B. pKa determination by 1H NMR spectroscopy – An old methodology revisited. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 93, 147–155. 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler P.; Wirz J. Struktur und photochemische Reaktivität: Photohydrolyse von Trifluormethylsubstituierten Phenolen und Naphtholen. Helv. Chim. Acta 1972, 55, 2693–2712. 10.1002/hlca.19720550802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kütt A.; Movchun V.; Rodima T.; Dansauer T.; Rusanov E. B.; Leito I.; Kaljurand I.; Koppel J.; Pihl V.; Koppel I.; Ovsjannikov G.; Toom L.; Mishima M.; Medebielle M.; Lork E.; Röschenthaler G.-V.; Koppel I. A.; Kolomeitsev A. A. Pentakis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl, a Sterically Crowded and Electron-withdrawing Group: Synthesis and Acidity of Pentakis(trifluoromethyl)benzene, -toluene, -phenol, and -aniline. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2607–2620. 10.1021/jo702513w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bogan A. A.; Thorn K. S. Anatomy of hot spots in protein interfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 280, 1–9. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Moreira I. S.; Fernandes P. A.; Ramos M. J. Hot spots – A review of the protein–protein interface determinant amino-acid residues. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2007, 68, 803–812. 10.1002/prot.21396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Bullock B. N.; Jochim A. L.; Arora P. S. Assessing Helical Protein Interfaces for Inhibitor Design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14220–14223. 10.1021/ja206074j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Santiveri C. M.; Jiménez M. A. Tryptophan residues: Scarce in proteins but strong stabilizers of β-hairpin peptides. Biopolymers 2010, 94, 779–790. 10.1002/bip.21436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.