Abstract

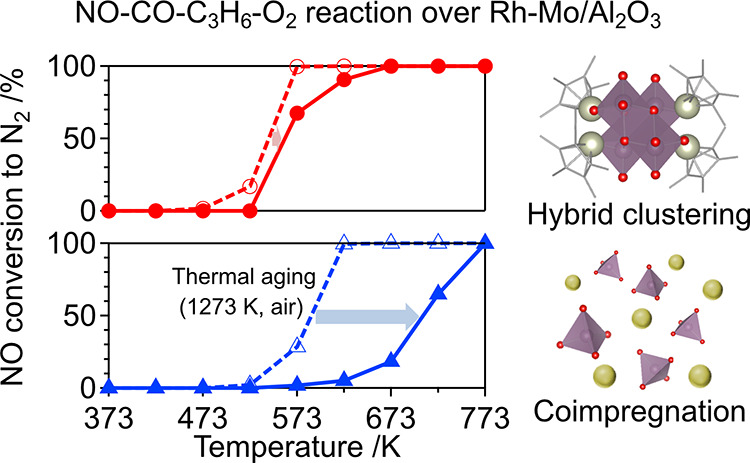

We developed a method for preparing catalysts by using hybrid clustering to form a high density of metal/oxide interfacial active sites. A Rh–Mo hybrid clustering catalyst was prepared by using a hybrid cluster, [(RhCp*)4Mo4O16] (Cp* = η5-C5Me5), as the precursor. The activities of the Rh–Mo catalysts toward the NO–CO–C3H6–O2 reaction depended on the mixing method (hybrid clustering > coimpregnation ≈ pristine Rh). The hybrid clustering catalyst also exhibited high durability against thermal aging at 1273 K in air. The activity and durability were attributed to the formation of a high-density of Rh/MoOx interfacial sites. The NO reduction mechanism on the hybrid clustering catalyst was different from that on typical Rh catalysts, where the key step is the N–O cleavage of adsorbed NO. The reducibility of the Rh/MoOx interfacial sites contributed to the partial oxidation of C3H6 to form acetate species, which reacted with NO+O2 to form N2 via the adsorbed NCO species. The formation of reduced Rh on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 was not as essential as that on typical Rh catalysts; this explained the improvement in durability.

Keywords: hybrid clustering, organometallic polyoxometalate, automotive catalysts, nanoparticles, interface, rhodium

1. Introduction

Three-way catalysts (TWCs), which remove major pollutants, such as carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons (HC), and nitrogen oxides (NOx), from exhaust emissions play an important role in automotive pollution control.1−4 Among the platinum group metal (PGM) elements frequently used as a key component of TWCs, Rh has been regarded as an essential element because of its efficiency in reducing NOx to N2. Because PGMs are scarce and expensive, a catalyst design for maximizing their use is required.

The development of support materials has improved the activity and durability of TWCs. TWCs are usually prepared by the impregnation method. In this method, PGM precursors are deposited on a support and calcined to form PGM nanoparticles. Metal oxides are used as supports because of their high thermal stability. Since the PGM nanoparticles are responsible for the reaction, metal dispersion is a critical factor for determining the performance. The metal/support interface plays an important role in inhibiting aggregation by stabilizing the metal species.5−8 Although the activity of TWCs is derived from PGMs, the development of PGM precursors has received limited attention.9,10 Precursors are typically monomeric compounds, such as chlorides and nitrate salts. This is because the type of precursor has little effect on the activity under harsh reaction conditions.11

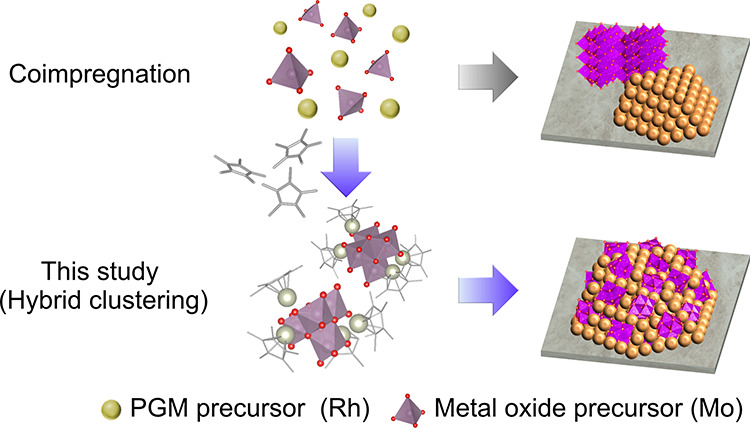

We had previously reported a catalyst preparation method; namely hybrid clustering, for the efficient formation of metal/oxide interfacial active sites.12 Hybrid clusters or organometallic polyoxometalates, formulated as [(M1L)xMy2On], are composed of metal ions (M1), metal oxide clusters (My2On), and organic ligands (L).13 Because the surface oxygen atoms of the metal oxide clusters are coordinated to the metal ions, the hybrid clusters can be considered as the minimal building blocks with a metal/oxide interface. Therefore, we predicted that catalysts prepared from hybrid clusters would comprise a high density of metal/oxide interfaces, contributing to the formation of unique catalytic active sites (Figure 1). Although hybrid clusters have potential for such applications, there have been few reports on their use in heterogeneous catalysts.14,15

Figure 1.

High-density formation of metal/oxide interfacial site through hybrid clustering.

In this study, we prepared Rh–M catalysts (M = V and Mo) by using hybrid clustering. The hybrid clustering catalysts displayed higher activities for TWC reactions than the Rh-based coimpregnated catalysts or pristine Rh catalysts. In addition, the durability of the Rh–Mo-based hybrid clustering catalyst against thermal aging was considerably improved.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Catalyst Preparation and Characterization

The hybrid clustering catalysts, Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 and Rh4V6/Al2O3, were prepared by using [(RhCp*)4Mo4O16] and [(RhCp*)4V6O19] (Cp* = η5-C5Me5), respectively, as the catalyst precursors. These precursors were synthesized as per procedures used in previous studies16,17 and characterized by Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) and 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectroscopy (Figures S1 and S2). After the precursor clusters were adsorbed onto γ-Al2O3 via impregnation with methanol, the catalysts were prepared by performing calcination under air flow at 773 K. Coimpregnated Rh–Mo and Rh–V catalysts, Rh–Mo/Al2O3 and Rh–V/Al2O3, and a pristine Rh catalyst, Rh/Al2O3, were prepared as references from RhCl3, (NH4)6[Mo7O24]·4H2O, and NH4VO3 under identical calcination conditions.

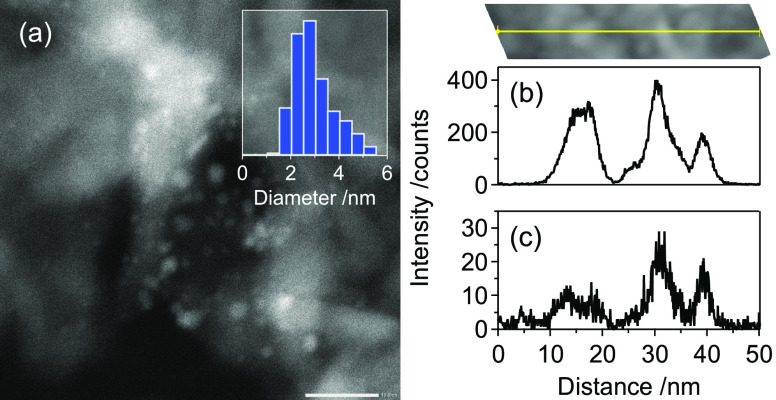

Based on high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) analysis, the average diameter of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 was estimated to be 3.0 ± 0.9 nm (Figure 2a). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis revealed that the distributions of Rh and Mo overlapped well, suggesting that the nanoparticles were composed of both Rh and Mo (Figure 2b,c).

Figure 2.

(a) HAADF-STEM image of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 (scale bar = 10 nm). EDS line scan analysis of (b) Rh (Rh Lα) and (c) Mo (Mo Kα). A yellow line on the upper-right panel indicates the scanning positions.

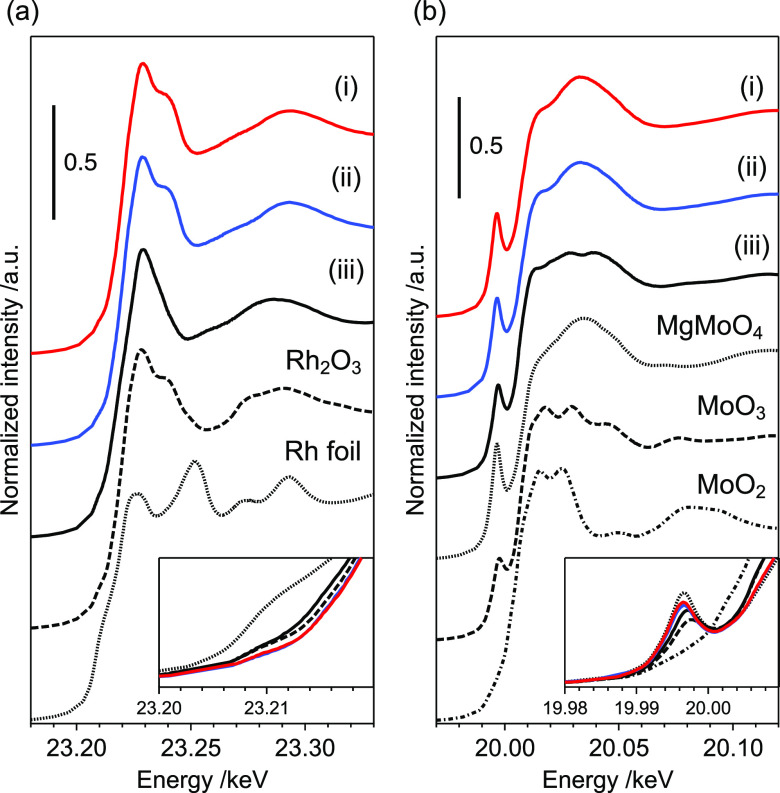

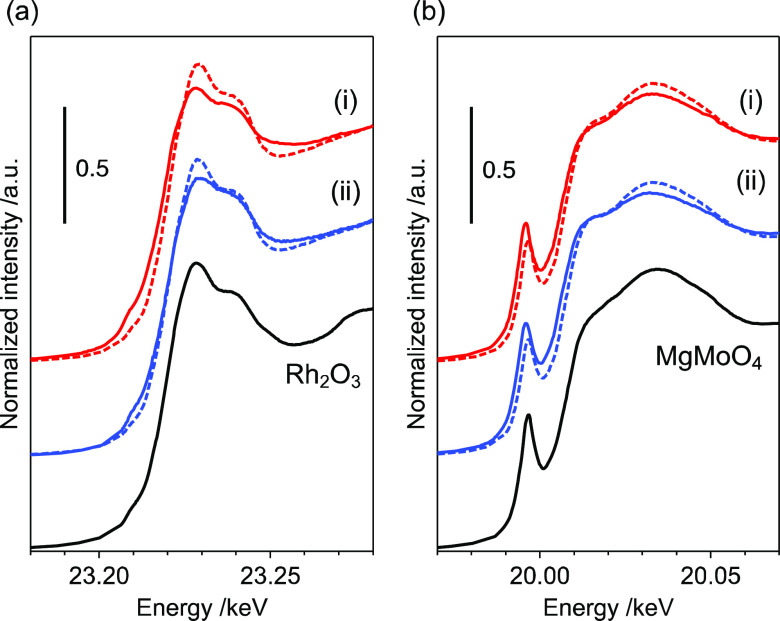

X-ray absorption near-edge structure analysis (XANES) was used to evaluate the electronic structures of Rh and Mo. The Rh K-edge XANES spectra revealed that the Rh species in both Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 and Rh–Mo/Al2O3 were Rh3+ (Figure 3a). The Fourier transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) spectra of the catalysts showed no peaks derived from the second coordination sphere, implying that the local structures of Rh were disordered (Figure S3). Because the pre-edge peaks in the Mo K-edge spectra were assigned to weak quadrupole-allowed (1s → 4d) and strong dipole-allowed (1s → 5p) transitions, the local structural disorder of the Mo oxide species reflects the intensity. The perfect octahedral symmetry only permits the quadrupole transition, while the structural disorder to distorted octahedral, square pyramidal, and tetrahedral symmetries promotes dipole-allowed transitions.18,19 The Mo K-edge spectrum of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 matched well that of Rh–Mo/Al2O3, implying that the local structure of Mo was independent of the preparation method. The pre-edge peak intensity of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 was larger than that of the precursor [(RhCp*)4Mo4O16], suggesting that structural distortion of the octahedral MoO6 unit occurred during catalyst preparation (Figure 3b). These findings imply that the electronic and local structures of Rh and Mo are independent of the catalyst preparation technique used.

Figure 3.

(a) Rh K- and (b) Mo K-edge XANES spectra of (i) Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, (ii) Rh–Mo/Al2O3, and (iii) [(RhCp*)4Mo4O16]. The spectra of (i) and (ii) closely overlap in the insets.

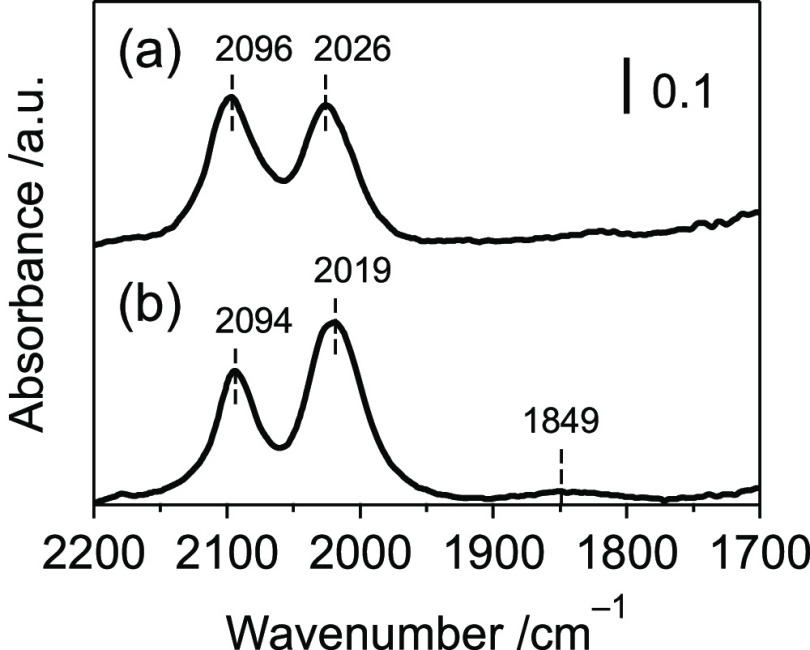

In contrast, the local structure of Rh evaluated by diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform (DRIFT) spectroscopy of adsorbed CO species depends on the catalyst preparation method (Figure 4). The doublet peaks observed for Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 corresponded to symmetric (2096 cm–1) and asymmetric (2026 cm–1) stretches of the geminal dicarbonyl species Rh(CO)2.20,21 This was also observed for Rh–Mo/Al2O3 (2094 and 2019 cm–1). No peak assigned to linear Rh–CO (2070 cm–1) was observed, whereas a small peak assigned to bridged Rh2(CO) (1849 cm–1) was observed only for Rh–Mo/Al2O3. The ratio of the integrated absorbance of symmetric and asymmetric stretches for Rh(CO)2 (Aas/As) is related to the angle between the two CO groups.8,22 For supported Rh-based catalysts, an atomically dispersed Rh species shows an angle of ∼90°, while a Rh nanoparticle shows an angle of ∼120°. The angles were estimated to be 89 and 112° for Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 and Rh–Mo/Al2O3, respectively (Figure S4, Table S1). This implies that Rh atoms in Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 were highly dispersed in Rh–Mo mixed nanoparticles, whereas the coimpregnation method afforded a typical Rh nanoparticle catalyst.

Figure 4.

DRIFT spectra of adsorbed CO species on (a) Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 and (b) Rh–Mo/Al2O3.

2.2. Activity for NO–CO–C3H6–O2 Reactions

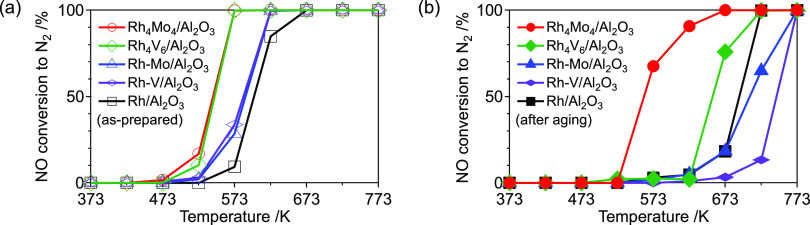

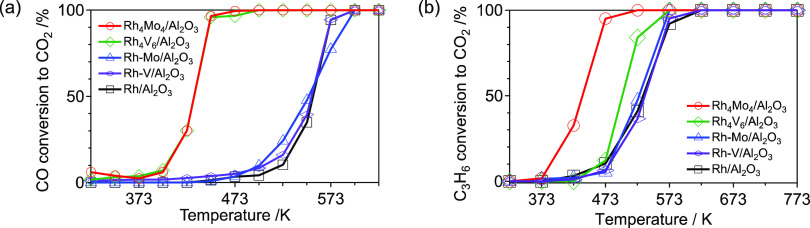

The activities of the catalysts were evaluated using NO–CO–C3H6–O2 reactions. When the reaction was catalyzed by Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, the reduction of NO to N2 started at 527 K, and a complete reduction of NO to N2 was observed at 573 K (T50 ∼ 543 K) (Figure 5a). This contrasts with Rh–Mo/Al2O3 and Rh/Al2O3, where the reaction started at 573 K (T50 ∼ 588 and 600 K, respectively). In these catalysts, the conversion of CO proceeded prior to that of NO and C3H6 (Figure S5). In addition, the conversion of NO to N2 in NO–C3H6–O2 over Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 showed a similar trend to that of NO–CO–C3H6–O2 (Figure S6). These findings imply that under the conditions of NO–CO–C3H6–O2, C3H6 is responsible for NO reduction. The durability of the catalysts is discussed based on their activity after thermal aging at 1273 K for 5 h in air. Activity was assessed without regeneration (reduction). Although significant activity loss was observed for Rh–Mo/Al2O3 and Rh/Al2O3 (T50 ∼ 707 and 693 K, respectively), only a slight decrease in the activity was observed for Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 (T50 ∼ 560 K) (Figure 5b). In the case of the Rh–V-based catalysts, Rh4V6/Al2O3 showed higher activity than Rh–V/Al2O3 (Figure 5a). In contrast, a significant activity loss after thermal aging was observed for both Rh4V6/Al2O3 and Rh–V/Al2O3 (Figure 5b). This indicates that the introduction of either Mo or V by hybrid clustering contributes to the improvement of activity, whereas the effect on durability is limited to Mo. This implies the importance of combining Rh and Mo as well as the catalyst preparation method.

Figure 5.

NO conversion to N2 in NO–CO–C3H6–O2 over the (a) as-prepared catalysts and (b) catalysts after thermal aging (1273 K, 5 h, air). Reaction condition: catalyst (200 mg) and total flow rate (100 mL min–1). Gas composition: NO (1000 ppm), CO (1000 ppm), C3H6 (250 ppm), and O2 (1125 ppm) balanced with He.

2.3. Origin of High Activity and Durability

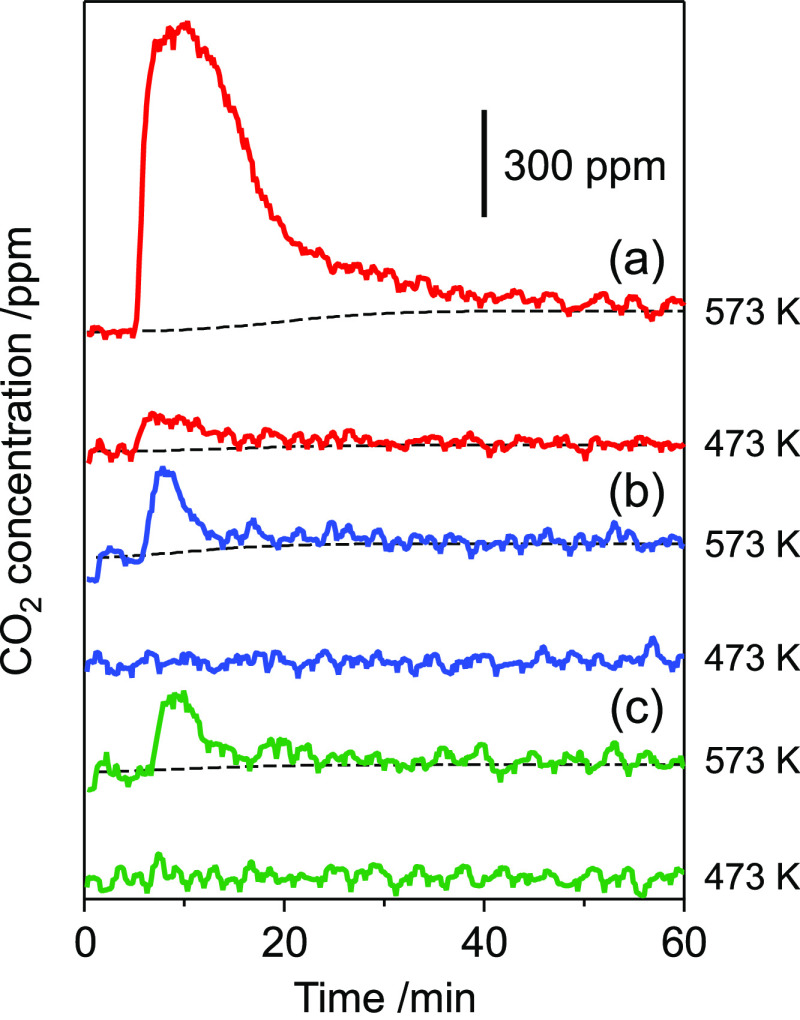

The electronic structures of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 and Rh–Mo/Al2O3 after the reaction were studied by using Rh K- and Mo K-edge XANES analyses. After the NO–CO–C3H6–O2 reaction at 773 K for 1 h, the catalyst was cooled to room temperature under He flow, exposed to air, and pelletized for XAS analysis. A red shift of both Rh K- and Mo K-edge spectra was observed for both catalysts, implying that the reduction of both Rh3+ and Mo6+ slightly progressed during the reaction, regardless of the catalyst preparation method (Figure 6). The interaction of the catalysts with CO was examined by transient response using mass spectrometry (MS). The switch from He to CO/He (1000 ppm) flow resulted in the immediate formation of CO2 but the concentration decreased over time (Figure 7). This behavior implies that CO2 was formed by the reaction of CO with the oxygen atom in the catalyst and not by the disproportionation of CO (2 CO → CO2 + C). Therefore, the amount of CO2 is a measure of the reducibility of the active phase or ease of oxygen vacancy formation. The formation of CO2 was observed at 573 K for Rh–Mo/Al2O3 and Rh/Al2O3. No significant difference was found in the amount of CO2 estimated from the peak area (Table S2), implying that the oxygen atom used for CO2 formation was derived from Rh species, and the introduction of Mo by coimpregnation did not affect the reducibility. In contrast, the formation of CO2 was observed at a lower temperature (473 K) for Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, and the amount of CO2 formed at 573 K was much larger than that of the reference catalysts. This suggests that the oxygen atoms used for CO2 formation were derived from Rh/MoOx interfacial sites. The relative ratio of CO2 to Rh in the catalyst (nCO2/nRh) was estimated to be 2.54 at 573 K (Table S2). This value is close to 3, which represents the number of oxygen atoms connected to Rh in the precursor [(RhCp*)4Mo4O16], indicating that the Rh/MoOx interface is derived from the precursor hybrid cluster.

Figure 6.

(a) Rh K- and (b) Mo K-edge XANES spectra of (i) Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 and (ii) Rh–Mo/Al2O3 before (dotted line) and after (solid line) the NO–CO–C3H6–O2 reaction at 773 K.

Figure 7.

Transient MS responses after the switch He→CO/He (1000 ppm). Catalyst: (a) Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, (b) Rh–Mo/Al2O3, and (c) Rh/Al2O3.

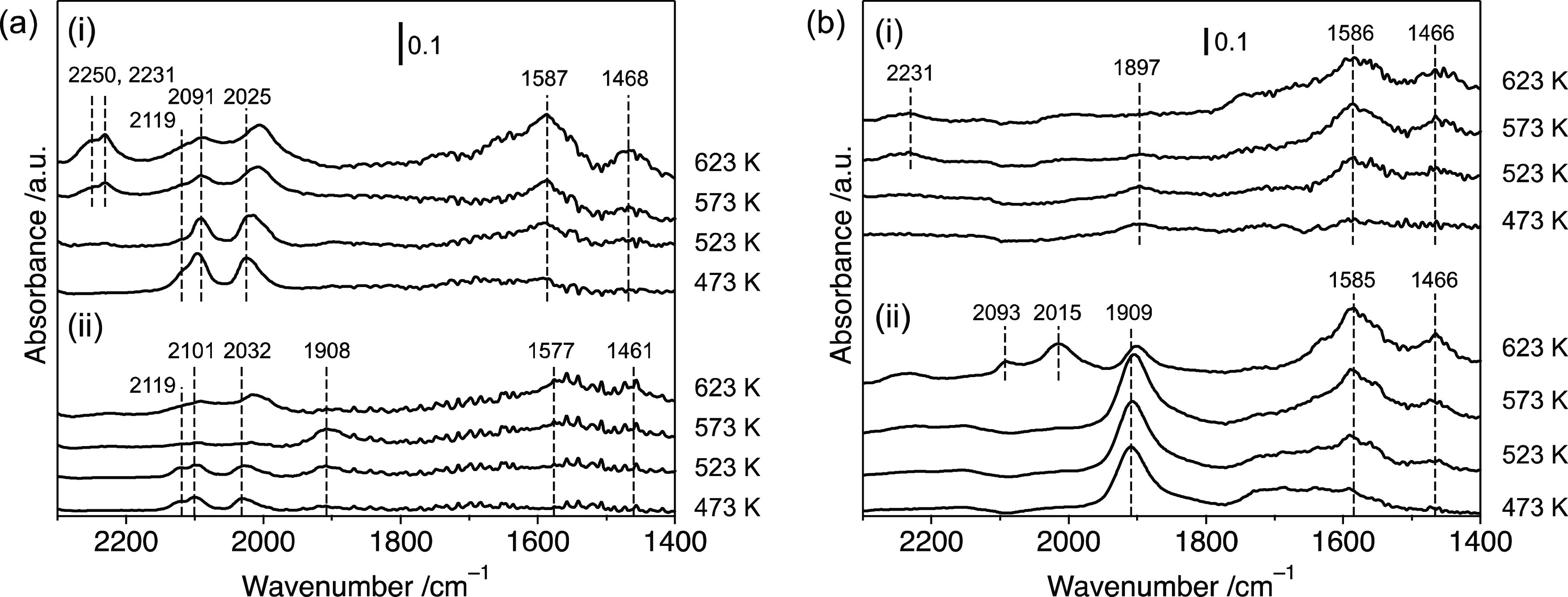

The adsorbed species on the catalyst in a flow of NO–CO–C3H6–O2 or NO–C3H6–O2 were studied by performing DRIFT analysis. The absorption bands were assigned according to the literature.23−27 In a flow of NO–CO–C3H6–O2, the bands observed for Rh–Mo/Al2O3 at 473 K were assigned to geminal Rh+(CO)2 (2101 and 2032 cm–1) and linear Rh2+–CO (2119 cm–1). As the temperature increased, bands assigned to bidentate acetate (νas(OCO) 1577 cm–1, νs(OCO) 1461 cm–1) and mononitrosyl Rh–NO+ (1908 cm–1) were observed (Figure 8a). In the case of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, the bands assigned to geminal Rh+(CO)2 (2091 and 2025 cm–1), linear Rh2+-CO (2119 cm–1), and bidentate acetate (νas(OCO) 1587 cm–1 and νs(OCO) 1468 cm–1) were also observed. No absorption bands assigned to adsorbed NO species were observed. Instead, a prominent peak assigned to isocyanate species bound to the Al site Al–NCO (2231 with a shoulder at 2250 cm–1) appeared at 573 K. In the flow of NO–C3H6–O2, an intense peak assigned to Rh–NO+ was also observed for Rh–Mo/Al2O3, whereas the intensity of the peak was negligibly small for Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 (Figure 8b). This trend was also confirmed by the DRIFT spectra of adsorbed species in a flow of NO (Figure S7). No peaks assigned to oxygenated NO species such as −NO3 were observed, except for a broad band of Rh–Mo/Al2O3 at 473 K (1730–1550 cm–1), which can be attributed to either oxygenated NO or partially oxidized C3H6 species. Al–NCO was also observed on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, with a much lower intensity than that in the flow of NO–CO–C3H6–O2. According to the mechanism of the NO–CO reaction over PGM catalysts,2,28,29 NO reduction occurs because of the N–O cleavage of adsorbed NO, leaving atomic nitrogen and oxygen on the surface. The formation of N2 occurs via the coupling of two nitrogen atoms. CO contributed to the removal of atomic oxygen from the surface. Because these reactions take place on reduced metal sites, the reducibility of the metal site is an essential factor for the NO–CO reaction. The N–O cleavage is regarded as the rate-determining step in Rh catalysts, and Rh–NO species are typically observed. Therefore, the absence of −NO species on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 implies a significant difference in the reaction mechanism or rate-determining step. The absence of −NO species and the presence of −NCO species on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 imply two possibilities for the origin of the improved activity. One possibility is that N–O cleavage on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 in the presence of CO is much faster than that of typical Rh catalysts. Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 showed improved reducibility compared to typical Rh catalysts (Figure 7), which is beneficial for N–O cleavage of adsorbed NO. In addition, the intensity of the peak assigned to Al–NCO after exposure to NO–CO–C3H6–O2 was much higher than that of NO–C3H6–O2, implying that the Al–NCO species were mainly derived from CO. Adsorbed −NCO can be formed by the reaction of adsorbed CO with atomic nitrogen formed by N–O cleavage of adsorbed NO.30 This consideration supports the possibility that adsorbed NO was quickly consumed by N–O cleavage on the Rh/MoOx interfacial site in the presence of CO.

Figure 8.

DRIFT spectra of adsorbed species in a flow of (a) NO–CO–C3H6–O2 and (b) NO–C3H6–O2 on (i) Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 and (ii) Rh–Mo/Al2O3. Gas composition: (a) NO (1000 ppm), CO (1000 ppm), C3H6 (250 ppm), and O2 (1125 ppm); (b) NO (1000 ppm), C3H6 (250 ppm), and O2 (625 ppm) balanced with He.

The second possibility is that the NO–C3H6–O2 reaction proceeded via a mechanism similar to that of the base metal oxide catalysts, which is different from that of the PGM catalysts. The absence of adsorbed NO leads to a mechanism where NO adsorption is not required. In contrast to PGM catalysts, where the reaction proceeds through N–O cleavage of adsorbed NO, the reaction mechanism proposed for base metal oxide catalysts involves the nitrate species NOx formed from NO and O2.31−35 The partially oxidized species of C3H6, such as aldehydes and acetates, were formed on the surface, which contributed to the formation of the reduced form of nitrogen, such as −NCO. The formation of N2 occurs by the reaction between oxidized (e.g., NO(g), −NOx) and reduced (e.g.,–NCO) nitrogen compounds. The absence of adsorbed NOx implied that the reduced nitrogen species on the surface reacted with gaseous or weakly adsorbed NOx species. The partial oxidation of C3H6 proceeds via abstraction of α-hydrogen followed by the insertion of oxygen to an allylic C–H bond.36 As reported for Bi–Mo-based oxides, practical catalysts for the partial oxidation of C3H6 to acrolein, the lattice oxygen atoms are involved in the reaction in the oxygen insertion process37,38 and the active sites are most probably Bi–O–Mo-containing phases.39,40 Therefore, we conclude that the oxygen atoms in Rh/MoOx interfacial sites on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 would contribute to the partial oxidation of C3H6 to provide the reduced nitrogen species efficiently. The presence of Al–NCO in the NO–C3H6–O2 flow supports the hypothesis that the reaction proceeds via the −NCO intermediate. Because C3H6 is responsible for NO reduction in the NO–CO–C3H6–O2 reaction (Figure S6), we expect that the reducibility of the Rh/MoOx interfacial site plays an essential role in the partial oxidation of C3H6 rather than the formation of oxygen vacancies being beneficial for N–O cleavage.

The origin of the durability of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 can also be attributed to the difference in the reaction mechanism. The thermal stabilities of PGM catalysts have been improved by metal–support interactions.6−8 The presence of strong M1–O–M2 interfacial bonding, where M1 and M2 represent the PGM and cationic elements in the support, respectively, prevents the active phase from being sintered. However, this also negatively impacts the activity. Although the metallic phase was more active than the oxidized phase, these interactions stabilized the oxidized phase rather than the metallic phase. In addition, the deactivation of Rh catalysts on γ-Al2O3 has been explained by the encapsulation of Rh and the formation of inactive rhodium–aluminate RhAlOx induced by the strong interactions between Rh and γ-Al2O3.41−43 Therefore, the active phases should be stabilized without losing the reducibility.7,8 In contrast, according to the NO reduction mechanism on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, the presence of reduced Rh is less important than that of typical PGM catalysts. We conclude that the durability of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 originates from the formation of thermally stable interfacial Rh/MoOx sites, where the presence of reduced Rh is not required for the reaction to progress.

To elucidate the different effects of Mo from V, the activities of the CO–O2 and C3H6–O2 reactions were also studied. Both Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 and Rh4V6/Al2O3 showed higher activities in the CO–O2 reaction than the reference catalysts, regardless of the type of secondary metal (Figure 9a). The formation of single-atomic or highly dispersed metal sites has been reported to be beneficial for CO oxidation.44,45 According to DRIFT measurements of adsorbed CO on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, Rh is highly dispersed in Rh–Mo mixed nanoparticles (Figure 4a). Therefore, we concluded that a high-density of Rh/MOx interface was formed regardless of the type of secondary metal (M = Mo, V), and the isolated Rh species at the interface were responsible for the reaction.

Figure 9.

(a) CO conversion to CO2 in the CO–O2 reaction and (b) C3H6 conversion to CO2 in the C3H6–O2 reaction over as-prepared catalysts. Reaction condition: catalyst ((a) 100 mg and (b) 200 mg) and total flow rate (100 mL min–1). Gas composition: (a) CO (1000 ppm) and O2 (500 ppm); (b) C3H6 (250 ppm) and O2 (1125 ppm) balanced with He.

Although Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 also showed high activity in the C3H6–O2 reaction, slight improvement in activity was observed for Rh4V6/Al2O3 (Figure 9b). As mentioned earlier, the initial step of C3H6 is the abstraction of α-hydrogen and the insertion of oxygen into an allylic C–H bond.36 The oxygen atoms in the Rh/MoOx interfacial site on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 participate in the oxygen insertion process. The high activity of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 in the C3H6–O2 reaction supports this mechanism. Therefore, the low activity of Rh4V6/Al2O3 suggests that the oxygen atoms at the Rh/VOx interfacial site do not contribute to the oxygen insertion process. This may also affect durability. In contrast to Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, the activity of Rh4V6/Al2O3 decreased substantially after thermal aging (Figure 5b). This may be due to the absence of surface oxygen atoms, which contribute to the partial oxidation of C3H6 in the case of Rh4V6/Al2O3.

The introduction of Mo to TWC catalysts has received attention because partially reduced Mo oxide species chemisorb NO to form geminal-dinitrosyl Mo(NO)2, which contributes to the formation of N2.2,46 The formation of the interfacial site of PMG with Mo is accomplished using a large excess of Mo, covering the entire surface of the support. However, this approach was impractical because of the high vapor pressure of MoO3, which volatilizes at above 873–1073 K under oxidizing conditions.46 To avoid volatilization, composite sites must be prepared at a relatively low loading (<10 wt %).2,47 According to ICP-MS analysis, the relative ratio of the loading amount (Mo/Rh) was retained after aging, suggesting that the volatilization of Mo was negligible (Table S3). A slight increase in both the Rh and Mo contents was observed for both Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 and Rh–Mo/Al2O3 after aging. This is due to the loss of crystalline water in the support. We therefore expect that catalyst preparation by hybrid clustering can be a practical method for forming interfacial sites in situations where the use of a large excess of precursors is unfavorable.

3. Conclusions

To form a high density of metal/oxide interfacial active sites, we prepared catalysts by employing hybrid clustering. A Rh–Mo hybrid cluster [(RhCp*)4Mo4O16] was applied as the catalyst precursor to prepare the hybrid clustering catalyst, Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, affording composite nanoparticles of Rh and Mo. According to the adsorption behavior of CO, the local structure of Rh was different from that of the coimpregnated Rh–Mo catalyst. Rh–Mo catalysts were used for the NO–CO–C3H6–O2 reaction, wherein their activities depended on the mixing method (hybrid clustering > coimpregnation ≈ pristine Rh). The hybrid clustering catalyst exhibited high durability against thermal aging at 1273 K in air. This is in sharp contrast to the coimpregnated catalyst, whose activity significantly decreased after thermal aging. The activity and durability of Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 were attributed to the formation of a high density of Rh/MoOx interfacial sites. The formation of CO2 under CO/He flow indicated the ease of oxygen vacancy formation. The absence of adsorbed NO on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 in the NO–CO–C3H6–O2 flow implied that the NO reduction mechanism on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 was different from that of typical PGM catalysts, where the key step is the N–O cleavage of adsorbed NO. The reducibility of the Rh/MoOx interfacial sites contributed to the partial oxidation of C3H6 to form acetate species, which reacted with NO+O2 to form N2 via adsorbed NCO. The formation of reduced Rh on Rh4Mo4/Al2O3 was not as essential as that on typical PGM catalysts; this explains the improvement in durability.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Catalyst Preparation

The hybrid clusters [(RhCp*)4Mo4O16] and [(RhCp*)4V6O19] were synthesized as per a procedure mentioned in the literature16,17 and characterized by employing FT-IR and 1H and 13C{1H} NMR. The hybrid clustering catalyst Rh4Mo4/Al2O3, was prepared as follows. [(RhCp*)4Mo4O16] (19.3 mg, 12.1 μmol) was dissolved in methanol (20 mL), and the solution was added dropwise to a methanolic dispersion of the γ-Al2O3 support (490 mg in 40 mL). The mixture was stirred for 2 h and then dried slowly at 373 K. The solid was then dried overnight at 353 K. The catalyst was obtained by performing calcination under air flow at 773 K for 1 h. Rh4V6/Al2O3 was prepared using [(RhCp*)4V6O19] as the precursor. Rh–Mo/Al2O3, Rh–V/Al2O3, and Rh/Al2O3 were prepared using the following precursors: RhCl3, (NH4)6[Mo7O24]·4H2O, and NH4VO3. Water was used as the solvent, instead of methanol. The calculated loading amounts of Rh, Mo, and V were 1.0, 0.93, and 0.74 wt %, respectively (Mo/Rh = 1, V/Rh = 1.5).

4.2. Characterization

NMR analysis was conducted using JEOL JNM-ECS400 (400 MHz (1H), 100 MHz (13C)). CDCl3 was used as the solvent and the chemical shifts were calibrated using tetramethyl silane (1H) or CDCl3 (13C, δ 77.0 ppm). FT-IR analysis was conducted using a JASCO FT/IR-4200 in transmission mode. The sample was mixed well with KBr and pressed to form a pellet, which was then used for analysis. HAADF-STEM and EDS analyses were conducted using a JEOL JEM-2800 equipped with a silicon drift detector. The sample was prepared by dropping a methanolic dispersion of the catalyst onto a copper grid with a support membrane and evaporating the solvent. The Mo K-edge and Rh K-edge XAS measurements were conducted using the BL01B1 beamline at SPring-8 of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute. The incident X-ray beam was monochromatized by using a Si(311) double-crystal monochromator. The measurements were conducted in fluorescence mode using a 19-element Ge solid-state detector at room temperature. The reference samples were ground well with boron nitride and pressed to form pellets. The XAS data were analyzed by utilizing the Rigaku REX2000 program. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis was performed by using an Agilent 7700x instrument. In an autoclave, the catalyst (ca. 50 mg) was digested with 6 mL of aq. H2SO4 (50% v/v) at 453 K for 18 h. The samples were then diluted with 1 M aq. HNO3, and 115In solution was added as an internal standard. Diffused reflectance infrared Fourier transform (DRIFT) spectra were recorded on a JASCO FT/IR-4200 spectrometer equipped with a mercury–cadmium–tellurium (MCT) detector cooled with liquid N2. The DRIFT spectra of the adsorbed CO were measured as follows: The catalysts (ca. 30 mg) were pretreated with He (50 mL min–1) at 773 K for 30 min and cooled to room temperature under He flow. DRIFT spectra were collected after the catalysts were exposed to 20% CO/He gas (50 mL min–1) for 10 min and purged with He for 10 min. In situ DRIFT spectra were obtained using the same procedure, except that the reaction gas (total flow rate, 100 mL min–1: NO, 1000 ppm; CO, 1000 ppm; C3H6, 250 ppm; O2, 1125 ppm; He balance) was used.

4.3. Catalytic Test

The catalytic tests were performed in a fixed-bed flow reactor at atmospheric pressure. In a tubular reactor (i.d. 8 mm), 200 mg of the catalyst was placed and pretreated with He (50 mL min–1) at 773 K for 1 h and cooled to room temperature under He flow. A total flow rate of 100 mL min–1 of reaction gas was introduced (gas hourly space velocity, GHSV ∼ 15,000 h–1) with a composition of NO (1000 ppm), CO (1000 ppm), C3H6 (250 ppm), and O2 (1125 ppm) balanced with He (stoichiometric condition, λ = 1). The reactor was heated from 373 to 773 K in a stepwise manner (50 K intervals). The temperature was maintained for 30 min before the analysis. The effluent gas was analyzed by using two gas chromatographs (Shimadzu GC-8A, Porapak Q and MS-5A columns) equipped with thermal conductivity detectors and a NOx analyzer (Anatec Yanaco ECL-88A Lite).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Takashi Sano (National Museum of Nature and Science, Japan) for assistance with the ICP-MS analysis. This research was financially supported by the Elements Strategy Initiative for Catalysts & Batteries (ESICB) and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (21K14463) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). HAADF-STEM analysis was conducted at the Advanced Characterization Nanotechnology Platform of the University of Tokyo, supported by the Nanotechnology Platform of MEXT. The synchrotron radiation experiment was performed with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) (2021A1283).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmaterialsau.3c00001.

Synthesis of hybrid clusters; results of characterization; and catalytic tests (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Taylor K. C. Nitric Oxide Catalysis in Automotive Exhaust Systems. Catal. Rev. 1993, 35, 457–481. 10.1080/01614949308013915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelef M.; Graham G. W. Why Rhodium in Automotive Three–Way Catalysts?. Catal. Rev. 1994, 36, 433–457. 10.1080/01614949408009468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrauto R. J.; Heck R. M. Catalytic Converters: State of the Art and Perspectives. Catal. Today 1999, 51, 351–360. 10.1016/S0920-5861(99)00024-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrauto R. J.; Deeba M.; Alerasool S. Gasoline Automobile Catalysis and Its Historical Journey to Cleaner Air. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 603–613. 10.1038/s41929-019-0312-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihata Y.; Mizuki J.; Akao T.; Tanaka H.; Uenishi M.; Kimura M.; Okamoto T.; Hamada N. Self–Regeneration of a Pd–Perovskite Catalyst for Automotive Emissions Control. Nature 2002, 418, 164–167. 10.1038/nature00893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y.; Hirabayashi T.; Dohmae K.; Takagi N.; Minami T.; Shinjoh H.; Matsumoto S. Sintering Inhibition Mechanism of Platinum Supported on Ceria–Based Oxide and Pt–Oxide–Support Interaction. J. Catal. 2006, 242, 103–109. 10.1016/j.jcat.2006.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Machida M. Rh Nanoparticle Anchoring on Metal Phosphates: Fundamental Aspects and Practical Impacts on Catalysis. Chem. Rec. 2016, 16, 2219–2231. 10.1002/tcr.201600037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H.; Kwon O.; Kim B.–S.; Bae J.; Shin S.; Kim H.–E.; Kim J.; Lee H. Highly Durable Metal Ensemble Catalysts with Full Dispersion for Automotive Applications beyond Single–Atom Catalysts. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 368–375. 10.1038/s41929-020-0427-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Force C.; Belzunegui J. P.; Sanz J.; Martínez–Arias A.; Soria J. Influence of Precursor Salt on Metal Particle Formation in Rh/CeO2 Catalysts. J. Catal. 2001, 197, 192–199. 10.1006/jcat.2000.3067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.; Yang X.; Yang L.; Zhou R. Three–Way Catalytic Performance of Pd/Ce0.67Zr0.33O2–Al2O3 Catalysts: Role of the Different Pd Precursors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 327, 335–343. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.11.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baylet A.; Royer S.; Marécot P.; Tatibouët J. M.; Duprez D. Effect of Pd Precursor Salt on the Activity and Stability of Pd–Doped Hexaaluminate Catalysts for the CH4 Catalytic Combustion. Appl. Catal., B 2008, 81, 88–96. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S.; Shishido T. High–Density Formation of Metal/Oxide Interfacial Catalytic Active Sites through Hybrid Clustering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 22332–22340. 10.1021/acsami.1c02240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putaj P.; Lefebvre F. Polyoxometalates Containing Late Transition and Noble Metal Atoms. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 1642–1685. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K.; Yamaguchi M.; Shido T.; Ohtani H.; Isobe K.; Ichikawa M. Molecular Modelling of Supported Metal Catalysts: SiO2 −Grafted [{(η3–C4H7)2Rh}2V4O12] and [{Rh(C2Me5)}4V6O19] Are Catalytically Active in the Selective Oxidation of Propene to Acetone. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1995, 1301–1303. 10.1039/C39950001301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa M.; Pan W.; Imada Y.; Yamaguchi M.; Isobe K.; Shido T. Surface–Grafted Metal Oxide Clusters and Metal Carbonyl Clusters in Zeolite Micropores; XAFS/FTIR/TPD Characterization and Catalytic Behavior. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 1996, 107, 23–38. 10.1016/1381-1169(95)00226-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y.; Toriumi K.; Isobe K. Novel Triple Cubane–Type Organometallic Oxide Clusters: [MCp*MoO4]4•nH2O (M = Rh and Ir; Cp* = C5Me5; n = 2 for Rh and 0 for Ir). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 3666–3668. 10.1021/ja00219a056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y.; Ozawa Y.; Isobe K. Site–Selective Oxygen Exchange and Substitution of Organometallic Groups in an Amphiphilic Quadruple–Cubane–Type Cluster. Synthesis and Molecular Structure of [(MCp*)4V6O19] (M = Rh, Ir). Inorg. Chem. 1991, 30, 1025–1033. 10.1021/ic00005a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T. Assignment of Pre–Edge Peaks in K-Edge x–Ray Absorption Spectra of 3d Transition Metal Compounds: Electric Dipole or Quadrupole?. X-Ray Spectrom. 2008, 37, 572–584. 10.1002/xrs.1103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shishido T.; Asakura H.; Yamazoe S.; Teramura K.; Tanaka T. Structural Analysis of Group V, VI, VII Metal Compounds by XAFS and DFT Calculation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2009, 190, 012073. 10.1088/1742-6596/190/1/012073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yates J. T.; Duncan T. M.; Worley S. D.; Vaughan R. W. Infrared Spectra of Chemisorbed CO on Rh. J. Chem. Phys. 1979, 70, 1219–1224. 10.1063/1.437603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh R. R.; Yates J. T. Site Distribution Studies of Rh Supported on Al2O3 – An Infrared Study of Chemisorbed CO. J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 74, 4150–4155. 10.1063/1.441544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R.; Li T.; Matsumura D.; Miao S.; Ren Y.; Cui Y.–T.; Tan Y.; Qiao B.; Li L.; Wang A.; Wang X.; Zhang T. Hydroformylation of Olefins by a Rhodium Single–Atom Catalyst with Activity Comparable to RhCl(PPh3)3. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 16054–16058. 10.1002/ange.201607885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondarides D. I.; Chafik T.; Verykios X. E. Catalytic Reduction of NO by CO over Rhodium Catalysts: 2. Effect of Oxygen on the Nature, Population, and Reactivity of Surface Species Formed under Reaction Conditions. J. Catal. 2000, 191, 147–164. 10.1006/jcat.1999.2785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halkides T. I.; Kondarides D. I.; Verykios X. E. Mechanistic Study of the Reduction of NO by C3H6 in the Presence of Oxygen over Rh/TiO2 Catalysts. Catal. Today 2002, 73, 213–221. 10.1016/S0920-5861(02)00003-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Moreno J. L.; Delahay G.; Figueras F.; Coq B. DRIFTS Study of the Nature and Reactivity of the Surface Compounds Formed by Co–Adsorption of NO, O2 and Propene on Sulfated Titania–Supported Rhodium Catalysts. J. Catal. 2005, 236, 292–303. 10.1016/j.jcat.2005.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haneda M.; Shinoda K.; Nagane A.; Houshito O.; Takagi H.; Nakahara Y.; Hiroe K.; Fujitani T.; Hamada H. Catalytic Performance of Rhodium Supported on Ceria–Zirconia Mixed Oxides for Reduction of NO by Propene. J. Catal. 2008, 259, 223–231. 10.1016/j.jcat.2008.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S.; Miura H.; Shishido T. Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO with CO and C3H6 over Rh/NbOPO4. Catal. Today 2019, 332, 267–271. 10.1016/j.cattod.2018.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Permana H.; Simon Ng. K. Y.; Peden C. H. F.; Schmieg S. J.; Lambert D. K.; Belton D. N. Adsorbed Species and Reaction Rates for NO–CO over Rh(111). J. Catal. 1996, 164, 194–206. 10.1006/jcat.1996.0375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chafik T.; Kondarides D. I.; Verykios X. E. Catalytic Reduction of NO by CO over Rhodium Catalysts: 1. Adsorption and Displacement Characteristics Investigated by In Situ FTIR and Transient–MS Techniques. J. Catal. 2000, 190, 446–459. 10.1006/jcat.1999.2763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker W. C.; Bell A. T. Infrared Observations of RhNCO and SiNCO Species Formed during the Reduction of NO by CO over Silica–Supported Rhodium. J. Catal. 1984, 85, 389–397. 10.1016/0021-9517(84)90228-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier F. C.; Breen J. P.; Zuzaniuk V.; Olsson M.; Ross J. R. H. Mechanistic Aspects of the Selective Reduction of NO by Propene over Alumina and Silver–Alumina Catalysts. J. Catal. 1999, 187, 493–505. 10.1006/jcat.1999.2622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K. I.; Kawabata H.; Maeshima H.; Satsuma A.; Hattori T. Intermediates in the Selective Reduction of NO by Propene over Cu–Al2O3 Catalysts: Transient in–Situ FTIR Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 2885–2893. 10.1021/jp9930705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haneda M.; Bion N.; Daturi M.; Saussey J.; Lavalley J. C.; Duprez D.; Hamada H. In Situ Fourier Transform Infrared Study of the Selective Reduction of NO with Propene over Ga2O3–Al2O3. J. Catal. 2002, 206, 114–124. 10.1006/jcat.2001.3478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burch R.; Breen J. P.; Meunier F. C. A Review of the Selective Reduction of NOx with Hydrocarbons under Lean–Burn Conditions with Non–Zeolitic Oxide and Platinum Group Metal Catalysts. Appl. Catal., B 2002, 39, 283–303. 10.1016/S0926-3373(02)00118-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K.; Ohyama J.; Satsuma A. Investigation of Reaction Mechanism of NO–C3H6–CO–O2 Reaction over NiFe2O4 Catalyst. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 3135–3143. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasselli R. K.; Burrington J. D.. Selective Oxidation and Ammoxidation of Propylene by Heterogeneous Catalysis. Adv. Cataly. 1981, 30, 133–163. [Google Scholar]

- Moro–Oka Y.; Ueda W.. Multicomponent Bismuth Molybdate Catalyst: A Highly Functionalized Catalyst System for the Selective Oxidation of Olefin. Adv. Cataly. 1994, 40, 233–273. [Google Scholar]

- Keulks G. W. The Mechanism of Oxygen Atom Incorporation into the Products of Propylene Oxidation over Bismuth Molybdate. J. Catal. 1970, 19, 232–235. 10.1016/0021-9517(70)90287-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burrington J. D.; Kartisek C. T.; Grasselli R. K. Surface Intermediates in Selective Propylene Oxidation and Ammoxidation over Heterogeneous Molybdate and Antimonate Catalysts. J. Catal. 1984, 87, 363–380. 10.1016/0021-9517(84)90197-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bettahar M. M.; Costentin G.; Savary L.; Lavalley J. C. On the Partial Oxidation of Propane and Propylene on Mixed Metal Oxide Catalysts. Appl. Catal., A 1996, 145, 1–48. 10.1016/0926-860X(96)00138-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C.; McCabe R. W. Effects of High–Temperature Oxidation and Reduction on the Structure and Activity of Rh/Al2O3 and Rh/SiO2 Catalysts. J. Catal. 1989, 119, 47–64. 10.1016/0021-9517(89)90133-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B.; Ran R.; Cao Y.; Wu X.; Weng D.; Fan J.; Wu X. Insight into the Effects of Different Ageing Protocols on Rh/Al2O3 Catalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 308, 230–236. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.04.140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. H.; Wu J.; Getsoian A. B.; Cavataio G.; Jinschek J. R. Direct Observation of Rhodium Aluminate (RhAlOx) and Its Role in Deactivation and Regeneration of Rh/Al2O3 under Three–Way Catalyst Conditions. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 2123–2132. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.1c03513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H.; Lee G.; Kim B. S.; Bae J.; Han J. W.; Lee H. Fully Dispersed Rh Ensemble Catalyst to Enhance Low–Temperature Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9558–9565. 10.1021/jacs.8b04613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniya A.; Higashi S. Towards Dense Single–Atom Catalysts for Future Automotive Applications. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 590–602. 10.1038/s41929-019-0282-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halasz I.; Brenner A.; Shelef M.; Simon Ng K. Y. Preparation and Characterization of PdO–MoO3/γ–Al2O3 Catalysts. Appl. Catal., A 1992, 82, 51–63. 10.1016/0926-860X(92)80005-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer J. T. Use of Noble Metals in Automobile Exhaust Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. A 1986, 90, 4747–4752. 10.1021/j100411a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.