Abstract

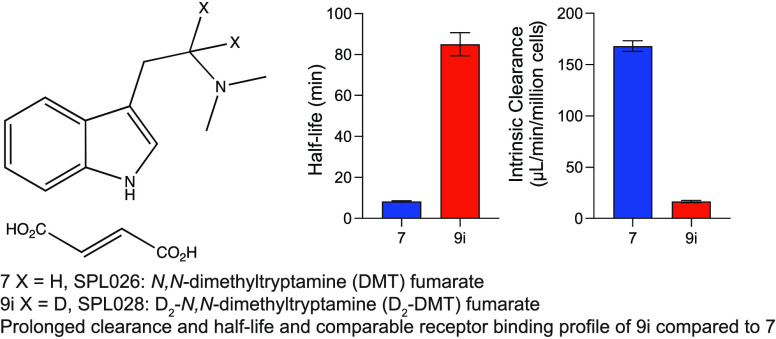

The psychedelic N,N- dimethyltryptamine (DMT) is in clinical development for the treatment of major depressive disorder. However, when administered via intravenous infusion, its effects are short-lived due to rapid clearance. Here we describe the synthesis of deuterated analogues of DMT with the aim of prolonging the half-life and decreasing the clearance rate while maintaining similar pharmacological effects. The molecule with the greatest degree of deuteration at the α-carbon (N,N-D2-dimethyltryptamine, D2-DMT) demonstrated the longest half-life and intrinsic clearance in hepatocyte mitochondrial fractions when compared with DMT. The in vitro receptor binding profile of D2-DMT was comparable to that of DMT, with the highest affinity at the 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2C receptors. D2-DMT was therefore the preferred candidate to consider for further evaluation.

Keywords: Psychedelic; N,N-Dimethyltryptamine; Deuterium kinetic isotope effect; Mental health; Depression

Psychedelic compounds present a novel approach to the treatment of many mental health disorders with a number of clinical studies demonstrating potential efficacy of psychedelic assisted therapy in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and treatment-resistant depression.1−3

N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) 1 is an endogenous indole alkaloid compound that is currently in clinical development to investigate its efficacy in the treatment of MDD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04673383; NCT05553691). 1 is capable of producing profound psychedelic effects4 owing to its modulation of multiple neurotransmitter receptors5,6 and consequential modification of signal diversity and functional connectivity.7 The primary psychological and potentially therapeutic effects of 1 are associated with its activity at serotonin receptors;8−10 in particular, 5-HT2A8,11–13 5-HT1A,11−13 and 5-HT2C receptor agonism.12,14−16 Modified signaling via the metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR2)17 and sigma-1 receptors18 have also been suggested to contribute to the complex receptor pharmacology of 1. These pharmacological effects can induce a unique and profound subjective experience which when complemented by psychological therapy, can facilitate emotional processing, the disruption of rigid thought patterns and the promotion of new ways of thinking.19,20

1 is not orally active as it is rapidly metabolized, chiefly by monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A).21 Moreover, after intravenous (IV) administration of 1 in healthy subjects and patients with MDD, psychological effects are apparent almost immediately, subside within a matter of minutes (∼20–30 min), and are dose-dependent.3,16 It has been hypothesized that a more complete psychedelic experience could be achieved if peak plasma and, therefore, brain concentrations of 1 are maintained over a longer period.22 Prolonging the acute pharmacological effects and/or the duration of the psychedelic experience is anticipated to increase cognitive flexibility,7 offering enhanced potential for therapeutic benefits. In addition, it is hypothesized that extending the duration of the patient’s psychedelic journey could be beneficial for more severe depression and, potentially, for treating other psychiatric indications. Studies exploring the pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD) and efficacy of extended DMT injection regimens are ongoing.

Chemical modification of drug molecules by deuteration represents an alternative approach to extending their PK profile.23 Deuterium (D) is a hydrogen isotope that contains one additional neutron to the most common isotope of hydrogen, protium (from here on referred to as hydrogen [H]).24 Deuterium is the simplest bioisostere for hydrogen with a slightly smaller molar volume, lower lipophilicity (Δlog Poct = −0.006), and a shorter C–D bond than the C–H bond.25 In organic compounds, the physical properties remain primarily unchanged when hydrogen is replaced by deuterium, thus retaining the same pharmacological profile of the parent molecule.26,27 Substitution of hydrogen with deuterium increases the bond strength. The rates of cleavage of C–H, N–H, and O–H bonds are 7.0, 8.5, and 10.6 times faster than the rates of cleavage for deuterated analogues.28 Deuterium replacement of hydrogen in an oxidatively labile carbon–hydrogen bond, when the cleavage of this bond is involved in the rate-determining step, can afford a kinetic isotope effect (KIE) by virtue of the difference in bond strength.29−31 If a KIE is realized in the modified compound, then the altered metabolic fate will change and potentially improve the efficacy, safety, and/or tolerability of the active substance.32−36

The KIE bestows a significant difference on the in vivo PK profile and behavioral effects of α,α,β,β-tetradeuterated DMT (D4-DMT) as compared with 1, thought to be mediated by an inhibition of MAO-mediated metabolism and transport dynamics.37−39 D4-DMT was found to have a shorter time to onset and potentiation of behavior-disrupting effects when compared to equivalent doses of 1 however, no kinetic data were reported to quantify the deuterium KIE.39

In vitro studies of trace amines and their deuterated analogues including the αα-d2 and ββ-d2 positions of 1 found that deuteration of the α-carbon reduced deamination, indicating the α-position as a rate-limiting step of enzymatic deamination, whereas deuteration of the β-carbon was shown to cause a slight enhancement in deamination.40 These observations suggest that modification of 1 with appropriate deuterium substitution of the α-hydrogen atoms of the indole-ethylamine group would have a direct effect on the enzymatic cleavage involved in the formation of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) 4.

The synthesis of N,N-D2-dimethyltryptamine (D2-DMT) 8i, chemical name (IUPAC) [2-(1H-indol-3-yl)(1,1-D2) ethyl]dimethylamine, has been reported in the literature; however, no biological or metabolic data have been published.41

We expect to find improved metabolic stability and altered in vivo exposure of the N,N-D2-dimethyltryptamine analogue blends (8i–8vi) and in N,N-D8-dimethyltryptamine (D8-DMT, 13). It is unlikely that deuterium substitution would have a direct effect on the rate of N-oxide formation; however, it may be possible that secondary isotope effects are present depending on the mechanism of the N-oxide formation, and so a deuterium KIE may still be possible.

The purpose of the studies presented here was to characterize the synthesis and in vitro activity of a series of novel deuterated DMT compounds designed to retain the primary receptor pharmacology of DMT while extending the PK and thus pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of DMT. The ultimate aim of the modifications is to increase the duration of psychedelic experience elicited by these compounds and explore their therapeutic efficacy for the treatment of mental health disorders. These compounds have previously been discussed43 and are disclosed in patents WO 2020/245133 and WO 2022/117359.

Design and Synthesis of the DMT Derivatives

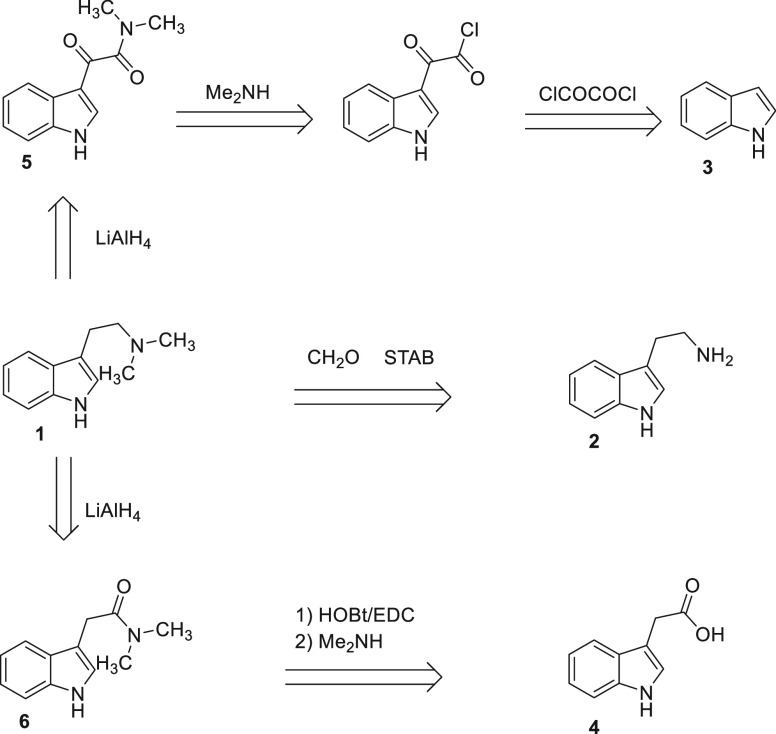

1H NMR and HPLC data for the novel compounds can be found in the Supporting Information. The first described synthesis of 1 converted tryptamine 2 via alkylation with methyl iodide.42 The synthetic approaches to deliver 1 have been reviewed,44 while the synthesis and characterization of 1 hemifumarate for human clinical trials have been reported.45 Three potential routes were considered, as illustrated in the retrosynthesis shown in Scheme 1. To support planned activities and preclinical and clinical development, a scaled-up preparation of 1 was required. The preferred synthetic route details (Scheme 2) and characterization are provided in the Experimental Section in the Supporting Information.

Scheme 1. Retrosynthetic Design for DMT.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Deuterium and Non-deuterium Containing N,N-Dimethyltryptamine Compounds.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) DCM/HOBt/EDC (ii) 2 M Me2NH in THF, 90%. (b) LiAlH4, THF, 92%. (c) EtOH, fumaric acid, 78%. (d) LiAlH4/LiAlD4 THF. (e) EtOH, fumaric acid, 52–68%. (f) (i) DCM/HOBt/EDC (ii) Me2NH.HCl, DIPEA, THF, 58%. (g) LiAlH4, THF, 97%. (h) EtOH, fumaric acid, 87%. (i) LiAlD4, THF, 97%. (j) EtOH, fumaric acid, 81%.

A one-step conversion of tryptamine 2 using formaldehyde and sodium triacetoxyborohydride (STAB) chemistry was discarded due to the genotoxicity risk of the reagents. An initial comparison of routes (5 g) starting with indole 3 or 4 indicated little difference between the routes in terms of output yield and purity compared to previously reported yields.45 However, the route starting with 4 was favored as it starts from the inexpensive and readily available starting material auxin, has a shorter overall route (isolation of intermediate not required), uses low toxicity reagents (1-ethyl-3-carbodiimide (EDC) and 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) versus oxalyl chloride), and required less LiAlH4 in the second step (0.9 equiv versus 2.0 equiv) when compared to the double reduction of β-keto-amide 5.

After a slurry purification step with hot tert-butyl methyl ether (TBME) to remove impurities from the coupling procedure, the conversion of 4 (267 g) to the N,N-d 6 using EDC and dimethylamine (Scheme 2) afforded a high yield (90%), with a solid product of high purity (98.5% by HPLC). It should be noted that a semibatch addition of EDC hydrochloride and dimethylamine was used to help to control the reaction, with relatively small exotherms of 5–10 °C observed thus avoiding the need for excessive cooling in both cases: EDC.HCl (337.5 g, 1.760 mol) was charged portion-wise over 5 min at 16–22 °C, and stirred for 2 h at ambient temperature before 2 M dimethylamine in THF (1100 mL, 2.200 mol) was charged dropwise over 20 min at 20–30 °C. For the second step, initial processing on multiple (10 g) reactions indicated a minimum of 0.9 equiv of LiAlH4 was required to achieve reaction completion and that warming the reaction to 60 °C also aided reaction completion without the need for extended stir-out times. Trial reactions found a reverse quench of the complete reaction mixture into 25% Rochelle’s solution (aqueous) that allowed for good control of exotherms and off-gassing as well as no significant impurity formation. The optimized workup procedure avoids the use of dichloromethane extraction, which can lead to the formation of small quantities of undesired byproduct N-chloromethyl-N,N-dimethyltryptamine chloride.46 The optimized reduction of intermediate 6 (282.5 g) with LiAlH4 (0.9 equiv) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) afforded 1 in 92% yield with 95% purity by HPLC. A mini-salt screen using solutions of 1 (0.25–2 M in ethanol) of five different acids (maleic, fumaric, hydrochloric, tartaric and citric) in four solvents (isopropanol [IPA], THF, isopropyl acetate and acetonitrile) indicated the fumarate salt to be the best candidate with successful salt formations in all four solvents. Further investigation showed that IPA and ethanol were the most suitable candidates for single-solvent salt formations. The results from these indicated that an ethanol-based salt formation in 10–15 volumes of solvent would allow for a good recovery of ∼80% as well as significant purging of impurities (input purity, ∼95%; output purity, 99.9%). Solubility of the fumarate salt of 1 in ethanol at temperatures above 65 °C also allowed for a suitable polish filtration window required for Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) processing (ICH Q7 – Good Manufacturing Practice for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients). With an input of 248.2 g of free base 1, and applying the optimized conditions, we afforded fumarate salt 7 (1:1 ratio) in 78% yield with 99.9% purity by HPLC as a crystalline solid (XRPD: Pattern A).

To generate a series of differentially deuterated DMT compounds, a modification of the amide 6 reduction chemistry was developed (Table 1). As sourcing LiAlD4 as a solution in THF proved troublesome, the reaction conditions were modified to use solid LiAlH4/LiAlD4 mixtures. This proved successful, although it required an excess of LiAlH4/LiAlD4 using 1.8 equiv instead of the 0.9 equiv used in the optimized synthesis of nondeuterated 1 described above. The previously reported synthesis of D2-DMT 8 also reduced amide 6 but required 2eq of LiAlD4.41 By varying ratios of solid LiAlH4 and LiAlD4 as set out in Table 1, the six preparations afforded deuterated products of 8i–vi as mixtures. D2-DMT compounds 8i–vi (C12H14D2N2) with varying levels of deuteration at the α-carbon to the nitrogen of the tertiary amine, as measured by MS. All final products 9i-vi were obtained as fumarate salts (C16H18D2N2O4) in >99% purity as measured by HPLC in overall yields ranging from 52% to 68%.

Table 1. Levels of Deuteration in Compound 1 Afforded by Varying the Ratio of LiAlH4/LiAlD4 in the Reduction of Amide 6a.

| Deuteration

% Mwt freebase |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D0 | D1 | D2 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | |||||

| LiAlH4:LiAlD4 ratio | output stage 3 (yield) | purity by HPLC (%) | 188 | 189 | 190 | 192 | 193 | 194 | 195 | 196 | Mwt | |

| SPL028i (9i) | 0:1 | 5.3 g (65%) | 99.3 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 96.6 | 306.32 | |||||

| SPL028ii (9ii) | 1:1 | 5.7 g (63%) | 99.9 | 30.0 | 48.3 | 21.7 | 305.28 | |||||

| SPL028iii (9iii) | 1:2 | 4.2 g (52%) | 99.9 | 16.5 | 46.8 | 36.8 | 305.74 | |||||

| SPL028iv (9iv) | 1:3 | 5.6 g (68%) | 99.8 | 9.3 | 41.5 | 49.2 | 305.75 | |||||

| SPL028v (9v) | 2:1 | 4.2 g (52%) | 99.8 | 47.5 | 41.3 | 11.2 | 304.98 | |||||

| SPL028vi (9vi) | 3:1 | 5.0 g (62%) | 99.4 | 57.4 | 35.3 | 7.4 | 305.03 | |||||

| SPL028vii (12) | 1:0 | 5.0 g (49%) | 99.9 | <0.01 | 1.2 | 98.8 | 310.38 | |||||

| SPL028viii (14) | 0:1 | 4.6 g (46%) | 99.9 | 0.1 | 3.2 | 96.7 | 312.39 | |||||

Percentage ratios of deuteration measured by LCMS. All purity by NMR was >95%. Mwt, Molecular weight.

The impact of additional deuteration in structure 1 on metabolic stability was explored by extending the described synthetic strategy to afford previously unreported preparative methodology for D6-DMT 11 (C12H10D6N2) and D8-DMT 13 (C12H8D8N2). The conversion of acid 4 to amide 10 was achieved using the HOBt/EDC coupling methodology developed previously except for the addition of 3 equiv of N,N-diisopropylthylamine (DIPEA) as the D6-dimethylamine hydrochloride salt. The reaction proceeded with a clean conversion to the desired product, but the reaction stalled with 28% of the starting material 4 remaining. Further additions of DIPEA did not affect the reaction profile. Following reaction workup and chromatography, 10 was afforded in 58% yield. Amide 10 was smoothly reduced to D6-DMT compound 11 in 97% yield prior to conversion to fumarate salt 12 (C16H14D6N2O4) in 87% yield. MS analysis found the following deuterium content: D0 = not detected; D1 = 0.01%; D5 = 1.2%; D6 = 98.8%. Similarly, amide 10 was smoothly reduced to D8-DMT compound 13 in 97% yield prior to conversion to fumarate salt 14 (C16H12D8N2O4) in 81% yield. MS analysis found the following deuterium content: D0, not detected; D6 = 0.1%; D7 = 3.2%; D8 = 96.7%.

Hepatocyte and Mitochondrial Fraction Clearance of Deuterated Compounds

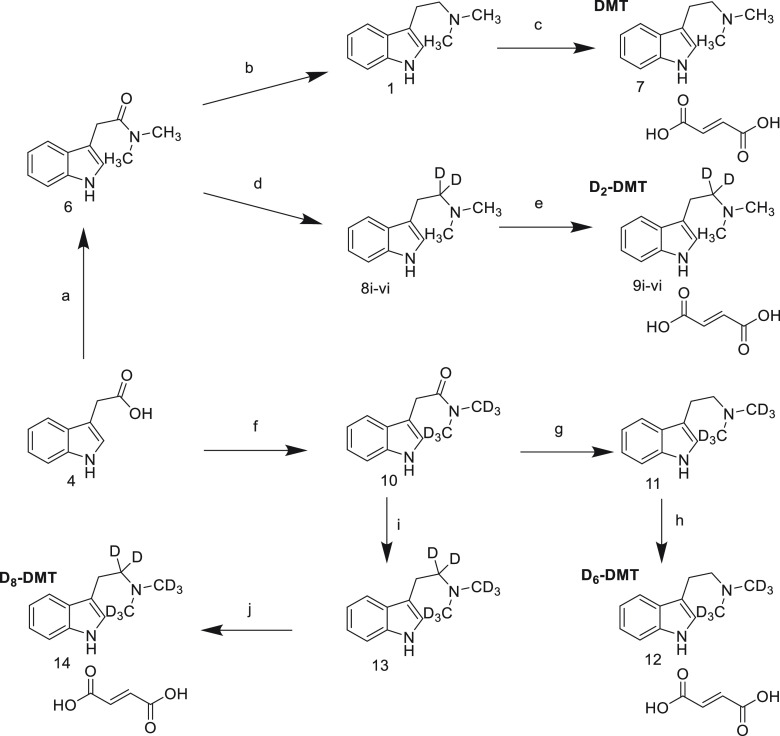

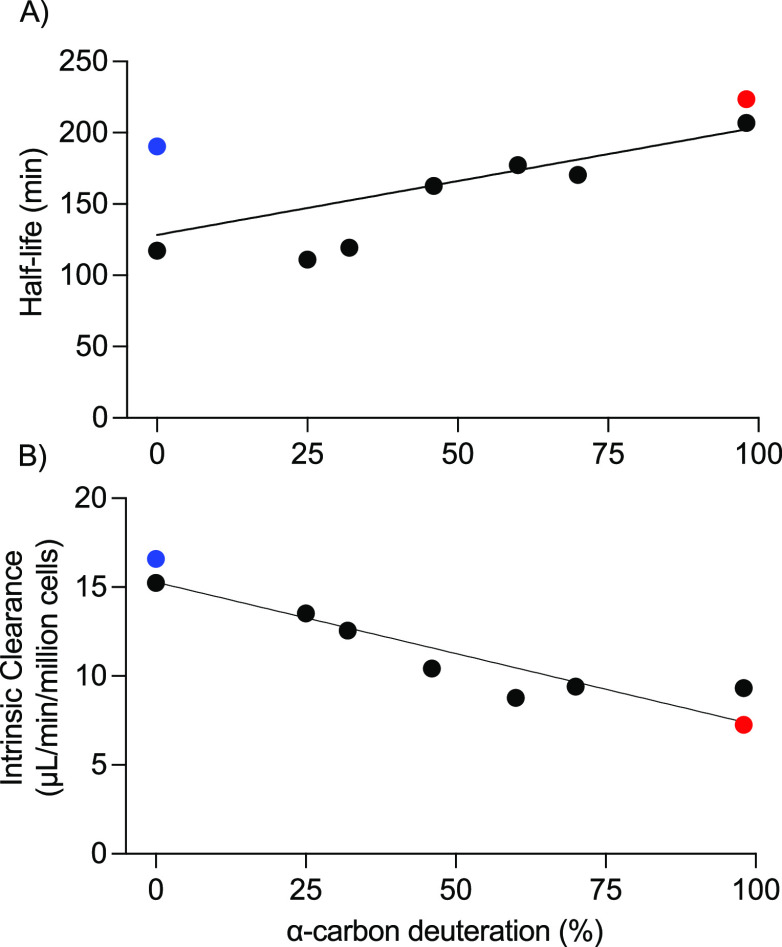

The in vitro whole cell hepatocyte and mitochondrial fraction metabolic stability of each deuterated DMT analogue (9i–9vi, 12, 14) and DMT (7) investigates the extent of KIE caused by deuteration at the α-carbon and N-methyl substituents and is summarized below. Sumatriptan, benzylamine, serotonin, diltiazem and diclofenac were included in each test batch as controls and demonstrated suitable clearance compared to historical data. There was an increase in in vitro stability for each DMT analogue with deuterium substitution at the α-carbon position in the human hepatocyte fraction when compared to DMT. A simple linear regression showed that the degree of deuteration at the α-carbon was found to significantly predict an increase in half-life (R2 adjusted; F = 6.9; 1,7; p = 0.03) and a decrease in clearance (F = 51.04; 1,7; p = 0.0002) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of DMT α-carbon deuteration on the in vitro (A) half-life and (B) intrinsic clearance in human hepatocytes. DMT (7) is shown in blue, and 96.6% D2-DMT (9i) is shown in red. N,N-D6-dimethyltryptamine, D6-DMT (12) (i.e., no α-carbon deuteration), is the first black point, and N,N-D8-dimethyltryptamine, D8-DMT (14), is the last black point. The black points between these extremes are the other N,N-D2-dimethyltryptamine analogue blends (9ii–9vi).

9i (96.6% D2-DMT, formulated as a fumarate salt) demonstrated the greatest effect on half-life (223.4 min) and clearance (7.3 μL/min/million cells) compared with parent 7 (DMT fumarate) (half-life, 190.4 min and clearance, 16.6 μL/min/million cells). Compound 14 exhibited a similar effect on half-life (206.9 min) and clearance (9.3 μL/min/million cells) on the in vitro stability of D2-DMT in human hepatocytes. The D6-DMT analogue 12 demonstrated a somewhat reduced half-life (117.2 min) but similar intrinsic clearance to the parent 7 (15.2 μL/min/million cells), indicating that deuteration of the α-carbon has a greater effect on metabolic stability compared to N-methyl substituents alone. Therefore, compound 9i was selected to undergo further in vitro characterization.

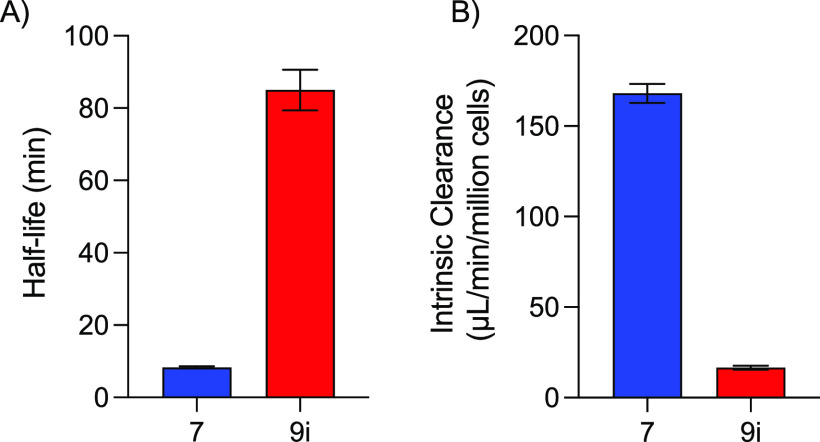

Human liver mitochondrial fractions contain a high proportion of MAO enzymes as well as aldehyde dehydrogenases and other xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes47 and thereby provide a useful tool to measure the clearance of MAO substrates such as DMT.21 Separate independent two sample t tests were performed to compare the mean clearance rate and mean half-life of 9i and 7. There was a significant difference in clearance rate between 9i (mean = 16.5, standard deviation [SD] = 2.2) and 7 (mean = 168.0, SD = 10.5); t(6) = 28.2, p < 0.001 (Figure 2); and a significant difference in half-life between 9i (mean = 85.1, SD = 11.3) and 7 (mean = 8.3, SD = 0.5); t(6) = 13.6, p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

(A) Half-life and (B) intrinsic clearance of 9i and 7 in human liver mitochondrial fractions.

Physicochemical Properties

The physicochemical properties of a drug following deuterium substitution are largely unchanged and so binding to biological targets are unaltered.25,26 However, the extent of the KIE in physiological systems can impact the clearance and distribution of a deuterated compound.

The distribution coefficient log D7.4 determines the distribution ratio between the lipid and aqueous phases in a solution of pH 7.4, i.e., the pH of blood. The log D7.4 values of 9i and 7 were conducted in order to determine the lipophilicity of 9i relative to 7. Mean log D7.4 (n = 2) value was 0.11 for 9i and 0.15 for 7, demonstrating that lipophilicity is low for both DMT and D2-DMT. Mean log D7.4 values for ketoconazole (3.56), propranolol (1.26), and verapamil (2.67) positive controls were within normal control range. These results indicate that 9i, similar to 7, will have poor membrane permeability and low nonspecific binding which was further supported by plasma protein binding data.

9i is largely unbound to proteins in human plasma (mean ratio free concentration:total concentration [fu] = 0.70) [mean recovery = 98%] and has similar plasma protein binding to 7 (human fu = 0.68 (mean recovery = 98%). The mean fu (mean recovery) of sumatriptan, warfarin and verapamil (control drugs) were 0.68 (96%), 0.05 (98%) and <0.010 (105%) respectively. These data indicate that 70% of 9i remains unbound and is available in the plasma for diffusion and metabolism.

The mean blood/plasma ratio of 9i is 1.34 in human blood (n = 2) revealing a lower distribution of 9i to erythrocyte blood fraction relative to plasma when compared to 7 (1.53 n = 2). Chloroquine (4.93), diclofenac (0.63), and verapamil (0.78) (control drugs) blood/plasma ratio data passed acceptance criteria.

Receptor Binding Profile of 9i

As expected, the in vitro receptor binding profile for 9i was comparable to that of 7. Assay results are presented as the percent inhibition of radioligand specific binding or enzyme activity. Both compounds demonstrated >50% inhibition of specific binding or activity at a concentration of 10 μM (6 μM free base) at 16 receptors and MAO-A enzyme (Table 2; full in vitro characterization is presented in Table S1).

Table 2. Mean Percent Inhibition in Enzyme and Agonist/Antagonist Radioligand Assay Using 10 μMa9i and 7.

| receptor | ligand | 9i percent inhibition | 7 percent inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 1.50 nM [3H] 8-OH-DPAT | 97.6 | 96.0 |

| 5-HT2B | 1.20 nM [3H] lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) | 96.5 | 95.5 |

| 5-HT7 | 5.50 nM [3H] lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) | 95.5 | 90.4 |

| 5-HT2A | 0.5 nM [3H] ketanserin | 93.9 | 89.9 |

| 5-HT2C | 1.0 nM [3H] mesulergine | 93.3 | 93.7 |

| H1 | 1.20 nM [3H] pyrilamine | 91.4 | 88.8 |

| α1B | 0.2 nM [3H] prazosin | 87.2 | 85.8 |

| 5-HT6 | 1.50 nM [3H] lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) | 86.2 | 86.1 |

| α1A | 0.6 nM [3H] prazosin | 85.1 | 85.1 |

| MAO-A | 84.3 | 85.3 | |

| α2B | 2.50 nM [3H] rauwolscine | 79.8 | 81.1 |

| 5-HT1B | 1.0 nM [3H] GR125743 | 75.5 | 73.1 |

| 5-HT5A | 1.70 nM [3H] lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) | 70.2 | 72.7 |

| α2A | 1.50 nM [3H] rauwolscine | 69.1 | 67.1 |

| nAChα3β4 | 0.05 nM [125I] epibatidine | 63.5 | 64.6 |

| α1D | 0.6 nM [3H] prazosin | 63.2 | 54.1 |

| α2C | 0.5 nM [3H] rauwolscine | 57.6 | 58.4 |

Concentration given as fumarate salt form.

As expected from the published literature, inhibition > 90% with 9i was observed at the 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2C receptors.8−10 Additionally, a high percentage of inhibition was observed at the 5-HT1B, 5-HT2B, 5-HT5A, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 receptors, which have previously been proposed as targets for 7.12 This is of interest as preclinical and clinical studies suggest an agonist role for some of these receptors in the therapeutic effects of a number of antidepressants.48 Notably, >50% inhibition with 9i was observed at all α-adrenergic receptors and also at H1 receptors and nAChα3β4 receptors. It has been suggested that interactions at multiple types of receptors may underpin the psychedelic effects of 7,49 but which receptors are critical for mediating the psychedelic experience remains unclear.

Notably, at σ1 receptors, inhibition with 9i at 10 μM (freebase) was 45%. However, as literature emphasizes, the effect of sigma binding of 7 may also be important to the therapeutic potential of DMT,18 and to this end, the binding of 9i to sigma receptors was tested at a range of concentrations. In line with previously published data on DMT, neither 7 nor 9i showed significant inhibition of [3H] pentazocine (15.0 nM) binding at sigma receptors at ≤10 μM. The concentrations used to report sigma-1 binding affinity in previously published data likely fall outside of biologically relevant concentrations.15 Inhibition of appropriate ligands of >50% was not observed for any of the ion channels tested or enzymes other than MAO-A.

Receptor binding affinities with 9i were highest for 5-HT7, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT1A (Table 3), and profiles for 9i and 7 support published data for DMT. Keiser et al. reported strongest binding affinities for DMT at 5-HT1D (Ki = 0.039 μM), 5-HT2A (Ki = 0.128 μM), 5-HT1B (Ki = 0.129 μM), 5-HT1A (Ki = 0.183 μM), 5-HT2B (Ki = 0.039 μM), 5-HT7 (Ki = 0.204 μM).129i and 7 were shown to have a greater percent inhibition of specific binding for 5-HT7 and 5-HT2A and a lower binding affinity for 5-HT1B compared to published data for DMT. 5-HT1D receptor binding was not assessed in the present study due to a lack of assay availability.

Table 3. Receptor Binding Affinities and Enzyme Inhibition for 9i and 7.

|

9i |

7 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| receptor/enzyme | ligand | IC50 (μM) | Ki (μM) | nH | IC50 (μM) | Ki (μM) | nH |

| 5-HT1A | 1.50 nM [3H] 8-OH-DPAT | 0.19 | 0.11 | 1.26 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.97 |

| 5-HT1B | 1.0 nM [3H] GR125743 | 1.99 | 1.52 | 0.74 | 2.42 | 1.84 | 0.76 |

| 5-HT2A | 0.5 nM [3H] ketanserin | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.78 |

| 5-HT2B | 2.0 nM [3H] mesulergine | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 1.08 |

| 5-HT2C | 1.0 nM [3H] mesulergine | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.94 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 1.38 |

| 5-HT5A | 1.70 nM [3H] lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) | 3.32 | 1.71 | 1.01 | 3.32 | 1.71 | 0.91 |

| 5-HT6 | 1.50 nM [3H] lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) | 1.08 | 0.50 | 0.77 | 1.21 | 0.56 | 0.84 |

| 5-HT7 | 5.50 nM [3H] lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.67 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.91 |

| α1A | 0.6 nM [3H] prazosin | 0.99 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.28 | 0.75 |

| α1B | 0.2 nM [3H] prazosin | 0.93 | 0.37 | 0.94 | 0.67 | 0.26 | 0.94 |

| α1D | 0.6 nM [3H] prazosin | 3.26 | 1.60 | 0.73 | 3.07 | 1.51 | 0.85 |

| α2A | 1.50 nM [3H] rauwolscine | 3.03 | 1.52 | 1.00 | 2.22 | 1.11 | 0.76 |

| α2B | 2.50 nM [3H] rauwolscine | 1.67 | 0.76 | 0.97 | 1.58 | 0.72 | 1.09 |

| α2C | 0.5 nM [3H] rauwolscine | 6.10 | 2.71 | 1.03 | 9.47 | 4.21 | 0.56 |

| H1 | 1.20 nM [3H] pyrilamine | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 1.09 |

| I2, central | 2.0 nM [3H] idazoxan | 2.60 | 1.73 | 0.99 | 1.93 | 1.29 | 0.87 |

| nAChα3β4 | 0.05 nM [125I] epibatidine | 4.40 | 3.18 | 0.90 | 4.20 | 3.03 | 0.79 |

| MAO-A | 1.50 | 1.18 | |||||

It is well-established that DMT can induce profound psychedelic effects and, based on this, has the potential to improve well-being in healthy subjects and therapeutic efficacy in patients.3,16,50 However, the acute psychedelic effects of DMT are short-lasting due to its rapid metabolism and high clearance rate. In the study presented here, DMT has been modified using deuteration with the aim of modifying the PK profile of the resulting DMT analogues. The D2-DMT compound 9i was selected as the optimal analogue, this compound showed improved in vitro metabolic stability attributed to inhibited oxidative deamination. Such modifications to the metabolic profile are anticipated to persist in vivo (Good et al., manuscript in preparation), resulting in prolonged drug exposure and pharmacodynamic effects. There were no marked changes in physicochemical properties to suggest an impact on drug promiscuity, exemplified by the minimal influence on in vitro binding affinities observed when comparing 9i and parent compound 7 (highest for all 5-HT receptors and α receptors tested; confirming previous published studies). Blood/plasma ratio for 9i was slightly lower than that for 7, although both compounds demonstrated drug distribution into the blood cells. This property should be considered when interpreting pharmacokinetic data.

Further assessments will determine whether the similarities in pharmacological profiles of 9i and 7 are reflected in preclinical in vivo studies (Good et al., in preparation) and, ultimately, in the safety, tolerability, and efficacy when administered to healthy subjects and patients in future clinical trials. The safety, tolerability, PK, and psychedelic effects of 7 (as SPL026) have been evaluated in psychedelic-naïve healthy subjects and in patients with major depressive disorder (where therapeutic efficacy was the primary end point) in a Phase I/IIa clinical trial (NCT04673383). A Phase I clinical study comparing the safety, tolerability, PK, and PD of 9i (as SPL028) administered by the IV vs intramuscular route is planned.

Acknowledgments

These studies were funded by Small Pharma. Editorial assistance in preparation of the manuscript was provided by Michelle Preston of Livewire Editorial Communications and was funded by Small Pharma.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin converting enzyme

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMT

N-dimethyltryptamine

- COC

cyclo-oxygenase

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylthylamine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-carbodiimide

- GMP

good manufacturing practice

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

- IPA

isopropanol

- IV

intravenous

- KIE

kinetic isotope effect

- LC/MS

liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

- MAO

monoamine oxidase

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PD

pharmacodynamics

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- RED

Rapid Equilibrium Dialysis

- STAB

sodium triacetoxyborohydride

- TBME

tert-butyl methyl ether

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00143.

Molecular formula strings (CSV)

Chemistry, experimental information; in vitro studies, experimental information; 1H NMR data for test compounds 7, 9i–9vi, 12, and 14; HPLC data for test compounds 7, 9i–9vi, 12, and 14; mean in vitro percent inhibition with 10 μM 9i; in vitro receptor, transporter, and ion channel binding assays; in vitro enzyme inhibition assays (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all the authors.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): M.L., P.R., M.G., Z.J., T.B., E.J. and C.R. are all currently paid employees of Small Pharma and have owned stock in the company, R.C. is a paid independent consultant engaged by Small Pharma.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gukasyan N.; Davis A. K.; Barrett F. S.; Cosimano M. P.; Sepeda N. D.; Johnson M. W.; Griffiths R. R. Efficacy and safety of psilocybin-assisted treatment for major depressive disorder: Prospective 12-month follow-up. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 36, 151–158. 10.1177/02698811211073759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. K.; Barrett F. S.; May D. G.; Cosimano M. P.; Sepeda N. D.; Johnson M. W.; Finan P. H.; Griffiths R. R. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. Psychiatry. 2021, 78, 481–489. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza D. C.; Syed S. A.; Flynn L. T.; Safi-Aghdam H.; Cozzi N. V.; Ranganathan M. Exploratory study of the dose-related safety, tolerability, and efficacy of dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in healthy volunteers and major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022, 47, 1854–1862. 10.1038/s41386-022-01344-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonaro T. M.; Gatch M. B. Neuropharmacology of N-N-dimethyltryptamine. Brain. Res. Bull. 2016, 126, 74–88. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker S. A. N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), an endogenous hallucinogen: past, present, and future research to determine its role and function. Front. Neurol. 2018, 12, 536. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J. F.; Romero S.; Mananas M. A.; Riba J. Serotonergic psychedelics temporarily modify information transfer in humans. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 18, pyv039. 10.1093/ijnp/pyv039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann C.; Roseman L.; Schartner M.; Milliere R.; Williams L. T. J.; Erritzoe D.; Muthukumaraswamy S.; Ashton M.; Bendrioua A.; Kaur O.; Turton S.; Nour M. N.; Day C. M.; Leech R.; Nutt D. J.; Carhart-Harris R. L. Neural correlates of the DMT experience assessed with multivariate EEG. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16324. 10.1038/s41598-019-51974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. L.; Canton H.; Barrett R. J.; Sanders-Bush E. Agonist properties of N,N-dimethyltryptamine at serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1998, 61, 323–330. 10.1016/S0091-3057(98)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols D. E. Psychedelics. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 264–355. 10.1124/pr.115.011478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshleman A. J.; Forster M. J.; Wolfrum K. M.; Johnson R. A.; Janowsky A.; Gatch M. B. Behavioral and neurochemical pharmacology of six psychoactive substituted phenethylamines: mouse locomotion, rat drug discrimination and in vitro receptor and transporter binding and function. Psychopharmacology. 2014, 231, 875–888. 10.1007/s00213-013-3303-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glennon R. A.; Titeler M.; McKenney J. D. Evidence for 5-HT2 involvement in the mechanism of action of hallucinogenic agents. Life. Sci. 1984, 35, 2505–2511. 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser M. J.; Setola V.; Irwin J. J.; Laggner C.; Abbas A. I.; Hufeisen S. J.; Jensen N. H.; Kuijer M. B.; Matos R. C.; Tran T. B.; Whaley R.; Glennon R. A.; Hert J.; Thomas K. L. H.; Edwards D. D.; Shoichet B. K.; Roth B. L. Predicting new molecular targets for known drugs. Nature. 2009, 462, 175–182. 10.1038/nature08506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle M.; Maqueda A. E.; Rabella M.; Rodriguez-Pujadas A.; Antonijoan R. M.; Romero S.; Alonso J. F.; Mañanas M. À.; Barker S.; Friedlander P.; Feilding A.; Riba J. Inhibition of alpha oscillations through serotonin-2A receptor activation underlies the visual effects of ayahuasca in humans. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 1161–1175. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce P. A.; Peroutka S. J. Hallucinogenic drug interactions with neurotransmitter receptor binding sites in human cortex. Psychopharmacology. 1989, 97, 118–122. 10.1007/BF00443425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray T. S. Psychedelics and the human receptorome. PLoS. One. 2010, 5, e9019 10.1371/journal.pone.0009019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassman R. Human psychopharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine. Behav. Brain. Res. 1995, 73, 121–125. 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonaro T. M.; Eshleman A. J.; Forster M. J.; Cheng K.; Rice K. C.; Gatch M. B. The role of 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and mGlu receptors in the behavioral effects of tryptamine hallucinogens N,N-dimethyltryptamine and N,N-diisopropyltryptamine. Psychopharmacology. 2015, 232, 275–284. 10.1007/s00213-014-3658-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanilla D.; Johanessen M.; Hajipour A. R.; Cozzi N. V.; Jackson M. B.; Ruoho A. E. The hallucinogen N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) is and endogenous sigma-1 receptor modulator. Science. 2009, 323, 934–937. 10.1126/science.1166127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens L. J.; Wall M. B.; Roseman L.; Demetriou L.; Nutt D. J.; Carhart-Harris R. L. Therapeutic mechanisms of psilocybin: Changes in amygdala and prefrontal functional connectivity during emotional processing after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2020, 34, 167–180. 10.1177/0269881119895520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M.; Evens R.; Mertens L. J.; Koslowski M.; Betzler F.; Gründer G.; Jungaberle H. Learning to Let Go: A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of How Psychedelic Therapy Promotes Acceptance. Front Psychiatry. 2020, 11, 5. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riba J.; McIlhenny E. H.; Bouso J. C.; Barker S. A. Metabolism and urinary disposition of N,N-dimethyltryptamine after oral and smoked administration: a comparative study. Drug. Test. Anal. 2015, 7, 401–406. 10.1002/dta.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallimore A. R.; Strassman R. J. A model for the application of target-controlled intravenous infusion for a prolonged immersive DMT psychedelic experience. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 211. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russak E. M.; Bednarczyk E. M. Impact of deuterium substitution on the pharmacokinetics of pharmaceuticals. Ann. Pharmacother. 2019, 53, 211–216. 10.1177/1060028018797110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.Deuterium. In: Deuterium: Discovery and Applications in Organic Chemistry; Yang J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2016; Ch. 2, pp 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pirali T.; Serafini M.; Cargnin S.; Genazzani A. A. Applications of deuterium in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5276–5307. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanwell N. A. Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 2529–2591. 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade D. Deuterium isotope effects on noncovalent interactions between molecules. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1999, 117, 191–217. 10.1016/S0009-2797(98)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberg K. B. The deuterium isotope effect. Chem. Rev. 1955, 55, 713–743. 10.1021/cr50004a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Urey H. C.; Price D. Observations on the Synthesis of Tetra-Deutero Methane. J. Chem. Phys. 1934, 2, 300. 10.1063/1.1749475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ling K. H.; Hanzlik R. P. Deuterium isotope effects on toluene metabolism. Product release as a rate-limiting step in cytochrome P-450 catalysis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989, 160, 844–849. 10.1016/0006-291X(89)92511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westheimer F. H. The magnitude of the primary kinetic isotope effect for compounds of hydrogen and deuterium. Chem. Rev. 1961, 61, 265–273. 10.1021/cr60211a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gant T. G. Using deuterium in drug discovery: leaving the label in the drug. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3595–3611. 10.1021/jm4007998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S.; Gupta M. Deuteration as a tool for optimization of metabolic stability and toxicity of drugs. Glob. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2017, 1, 555566. 10.19080/GJPPS.2017.01.555566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. F.; Harbeson S. L.; Brummel C. L.; Tung R.; Silverman R.; Doller D. Chapter 14 - A decade of deuteration in medicinal chemistry. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2017, 50, 519–542. 10.1016/bs.armc.2017.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cargnin S.; Serafini M.; Pirali T. A primer of deuterium in drug design. Future. Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 2039–2042. 10.4155/fmc-2019-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopf S.; Bourriquen F.; Li W.; Neumann H.; Junge K.; Beller M. Recent developments for the deuterium and tritium labeling of organic molecules. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 6634–6718. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker S. A.; Beaton J. M.; Christian S. T.; Monti J. A.; Morris P. E. Comparison of the brain levels of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and alpha, alpha, beta, beta-tetradeutero-N-N-dimethyltryptamine following intraperitoneal injection. The in vivo kinetic isotope effect. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1982, 31, 2513–2516. 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker S. A.; Beaton J. M.; Christian S. T.; Monti J. A.; Morris P. E. In vivo metabolism of α,α,β,β-tetradeutero-N,N-dimethyltryptamine in rodent brain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984, 33, 1395–400. 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton J. M.; Barker S. A.; Liu W. F. A comparison of the behavioral effects of proteo-and deutero-N, N-dimethyltryptamine. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1982, 16, 811–814. 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P. H.; Barclay S.; Davis B.; Boulton A. A. Deuterium isotope effects on the enzymatic oxidative deamination of trace amines. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1981, 30, 3089–3094. 10.1016/0006-2952(81)90497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris P. E.; Chiao C. Indolealkylamine metabolism: synthesis of deuterated indolealkylamines as metabolic probes. J. Labelled. Compd. Radiopharm. 1993, 33, 455–65. 10.1002/jlcr.2580330603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manske R. H. F. Synthesis of the methyltryptamines and some derivatives. Can. J. Res. 1931, 5, 592–600. 10.1139/cjr31-097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kargbo R. B. Application of Deuterated N,N-Dimethyltryptamine in the Potential Treatment of Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13 (9), 1402–1404. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron L. P.; Olson D. E. Dark classics in chemical neuroscience: N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT). ACS. Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 2344–2357. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi N. V.; Daley P. F. Synthesis and characterization of high-purity N,N-dimethyltryptamine hemifumarate for human clinical trials. Drug. Test. Anal. 2020, 12, 1483–1493. 10.1002/dta.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap L. E.; Olson D. E. Reaction of N,N-Dimethyltryptamine with Dichloromethane Under Common Experimental Conditions. ACS. Omega. 2018, 3, 4968–4973. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuo Y.; Nagamori S.; Hasegawa A.; Hayashi K.; Isozumi N.; Nakamichi N.; Kanai Y.; Kato Y. Utilization of liver microsomes to estimate hepatic intrinsic clearance of monoamine oxidase substrate drugs in humans. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 1233–1243. 10.1007/s11095-017-2140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifirski G.; Krol M.; Turlo J. 5-HT receptors and the development of new antidepressants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9015. 10.3390/ijms22169015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballentine G.; Friedman S. F.; Bzdok D. Trips and neurotransmitters: discovering principled patterns across 6850 hallucinogenic experiences. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl6989 10.1126/sciadv.abl6989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søgaard Juul T.; Ebbesen Jensen M.; Fink-Jensen A. The use of classic psychedelics among adults: a Danish online survey. Nord. J. Psychiatry. 2023, 77, 367. 10.1080/08039488.2022.2125069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.