Abstract

Studies have found that exclusive breastfeeding can not only promote the growth and development of infants, but also increase the emotional communication between mothers and infants, and reduce the incidence of maternal breast diseases. To analysis the current situation and influencing factors of breastfeeding twins. A total of 420 twin mothers delivered in our hospital from January 2019 to December 2022 were selected to investigate the situation of breastfeeding within 6 months after delivery. An electronic questionnaire was conducted, and clinical information were collected. Univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis were applied to analyze the factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding. The rate of exclusive breastfeeding was 21.90%; in the exclusive breastfeeding group, the age <35 years old, bachelor degree or above, rural areas, no nipple depression or flat, no breast distension, no postpartum depression, adequate breast milk, participation in health education during pregnancy, husband support for breastfeeding, no infant feeding difficulties, infant diarrhea, lactose intolerance and return to milk were 96.74%, 53.26%, 65.22%, 80.43%, 76.09%, 80.43%, 73.91%, 63.04%, 69.57%, 71.74%, 65.22%, 70.65%, and 66.30%, respectively. It was significantly higher than that in the non-exclusive breastfeeding group (P < .05). The score of Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) was (8.08 ± 1.03) in the exclusive breastfeeding group, which was significantly lower than that in the non-exclusive breastfeeding group (P < .001), while the score of Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) was (67.32 ± 9.92), which was significantly higher than that in the non-exclusive breastfeeding one(P < .001). Logistic regression analysis showed that age, education level, nipple depression or flat, breast tenderness, postpartum depression, breast milk volume, health education training during pregnancy, husband support for breastfeeding, PSSS score, infant diarrhea, lactose intolerance, and delectation were the influencing factors of exclusive breastfeeding (P < .001). Our findings suggest that various factors were associated with a low rate of exclusive breastfeeding in twin births, such as age, educational level, and social support. Corresponding measures should be formulated for intervention to promote exclusive breastfeeding.

Keywords: breast-feeding, current situation investigation, influence factor, twins

1. Introduction

Breast milk has always been the most suitable food for infants, which can provide the best nutrition for newborn infants within 6 months. The World Health Organization advocates exclusive breastfeeding for infants under 6 months for its high nutritional contents and immune active substances.[1,2] Recent studies have found that the rapid development of industrialization and changes in modern attitudes have led to a decrease in maternal physical function and significant mood swings after childbirth, thus leading to a decrease in breast milk production, which has an impact on breastfeeding.[3] A study reported that the rate of exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months of age was significantly lower than that of first-born mothers, suggesting that the rate and duration of exclusive breastfeeding in China was still not optimistic.[4,5]

With the advancements in reproductive technology and the increasing prevalence of multiple pregnancies in recent years, the birth of twins has become increasingly common worldwide.[6] The arrival of twins brings double the joy to every family, but it also presents double the challenges. Particularly in the crucial and natural aspect of breastfeeding, mothers of twins often face more pressure and difficulties.[7] Previous studies have indicated that the breastfeeding rates for twin infants are relatively lower, and the duration of breastfeeding is shorter.[8] The reasons behind this are multifaceted, encompassing physiological, psychological, and social factors.[7,9] For instance, some twin mothers may choose to supplement with formula feeding due to fears of insufficient breast milk production, or they may experience feelings of frustration and loneliness due to inadequate family and social support. Although there have been a lot of studies focusing on the influencing factors of breastfeeding, the studies on the current situation of twin breastfeeding in clinic are still few, especially the analysis of the influencing factors of twin breastfeeding. In this study, the questionnaire was used to collect and sort out the relevant data of twin maternal families in the region, and analyze the influencing factors of exclusive breastfeeding with the aim of providing a basis for clinical implementation of interventions to improve the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in twin births.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. General information

This was an observational questionnaire-based study. This study collected data from January 2019 to December 2022 for the analysis of twin mothers delivered in Chongqing Health Center for Women and Children/Women and Children Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. A total of 420 twin mothers aged 22 to 37 years, 55 of them were ≥35 years old and 365 were <35 years old. Natural childbirth 23, cesarean section 397; 360 primiparas and 60 midwives. Inclusion criteria: twins survived with both birth weights >2500 g; full-term pregnancy; neonatal mother-infant room; can cooperate to complete the relevant questionnaire survey; and informed consent of twin mothers. Exclusion criteria: High-risk infants transferred to neonatal treatment or mothers transferred to intensive care unit due to high-risk diseases leading to mother-to-child separation; maternal or family members are not willing to accept telephone interviews or answer questions are not clear; infants born with congenital defects, genetic metabolic diseases and other diseases; twin mothers have feeding taboos; and patients with mental illness history. This study was supported by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Health Center for Women and Children.

2.2. Survey methods

The questionnaire was designed by the method of evidence-based medicine, and the content of the questionnaire was formally determined after thematic discussion and revision, including age, parity, mode of delivery, BMI during pregnancy, educational level, location, monthly income per capita of the family, nipple status, breast distension, postpartum depression, breast milk volume, health education, husband support for breastfeeding, Infant feeding difficulties, and presence of sickness and hospitalization of mother and baby separation. The surveyors were trained and qualified to implement the questionnaire and ensure the confidentiality of maternal and family related information. The definition of exclusive breastfeeding is that no food other than breast milk is added to the infant, except for medication and vitamins needed for treatment.

The investigators’ on-site investigation process provided explanation and helped to the puerpera. Under the supervision of the investigator, the questionnaire was filled out and recycled. After checking the questionnaire, both of them entered the computer system. During the input process, suspicious data were found to check the original questionnaire. The analysis of text data was carried out by both of them at the same time. The stage of occurrence was determined by group discussion. The final results are fed back to the respondents for further verification, and they can be interviewed again if necessary.

2.3. Investigation tools

The simplified Chinese version of Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS)[10] was used to assess the depression of mothers, which has 10 items and a total score of 30, with ≥10 being postnatal depression. The higher the score indicates the more serious the depression. The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS)[11] was used to evaluate the social support of mothers, which has 3 dimensions and a total score of 84. The higher the score indicates the higher the degree of social support.

2.4. Statistical analysis

SPSS 22.0 software was used for statistical analysis. Measurement data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared by t test. Count data were expressed as n (%) and compared by χ2 test. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify factors that influence breastfeeding. Power and sample size estimations was performed using the GraphPad StatMate software. The number of enrolled patients was estimated based on literature and preliminary data, and assuming a power of 0.8 to detect a difference of at least 20% with a significance of 0.05. P < .05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Exclusive breastfeeding

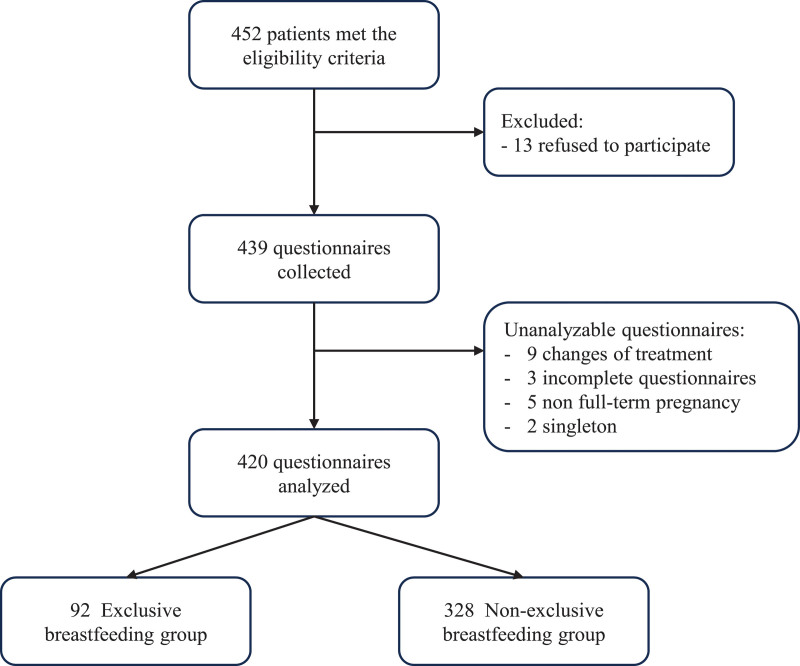

Of the 420 mothers, there were 840 infants, among which 184 were exclusively breastfed and 656 were non-exclusively breastfed. The rate of exclusive breastfeeding was 21.90%. Figure 1 shows the study flow chart.

Figure 1.

Study flow-chart.

3.2. Comparison of clinical data between exclusive breastfeeding group and non-exclusive breastfeeding group

The age (P = .002), education level (P = .003), place of residence (P < .001), sunken or flat nipples (P < .001), breast tenderness (P = .001), postpartum depression (P < .001), breast milk volume (P < .001), participate in health education and other training during pregnancy (P < .001), husband supports breastfeeding (P < .001), infant feeding difficulties (P < .001), infantile diarrhea (P < .001), lactose intolerance (P < .001), and delectation (P < .001) were found significant difference between the 2 groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical data between the 2 groups.

| Variables | Exclusive breastfeeding group (n = 92) | Non-exclusive breastfeeding group (n = 328) | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 10.012 | .002 | ||

| ≥35 yr old | 3 (3.26) | 52 (15.85) | ||

| <35 yr old | 89 (96.74) | 276 (84.15) | ||

| Parity | 0.084 | .773 | ||

| Primipara | 78 (84.78) | 282 (85.98) | ||

| Parturient women | 14 (15.22) | 46 (14.02) | ||

| Mode of delivery | 1.035 | .309 | ||

| Spontaneous childbirth | 7 (7.61) | 16 (4.88) | ||

| Cesarean section | 85 (92.39) | 312 (95.12) | ||

| BMI during pregnancy | 0.153 | .696 | ||

| Normal | 66 (71.74) | 242 (73.78) | ||

| Abnormal | 26 (28.26) | 86 (26.22) | ||

| Mode of conception | 4.248 | .12 | ||

| Nature conceived | 15 (16.30) | 53 (16.16) | ||

| Vitro fertilization/embryo transfer | 31 (33.70) | 77 (23.48) | ||

| Ovulation induction and pregnancy | 46 (50.00) | 198 (60.37) | ||

| Education level | 8.962 | .003 | ||

| Junior college or below | 43 (46.74) | 178 (54.27) | ||

| Bachelor, master or above | 49 (53.26) | 150 (45.73) | ||

| Place of residence | 25.518 | <.001 | ||

| Urban | 32 (34.78) | 210 (64.02) | ||

| Rural | 60 (65.22) | 118 (35.98) | ||

| Monthly per capita household income (yuan) | 0.356 | .551 | ||

| ≥5000 yuan | 68 (73.91) | 232 (70.73) | ||

| <5000 yuan | 24 (26.09) | 96 (29.27) | ||

| Sunken or flat nipples | 14.1 | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 18 (19.57) | 134 (40.85) | ||

| No | 74 (80.43) | 194 (59.15) | ||

| Breast tenderness | 12.011 | .001 | ||

| Yes | 22 (23.91) | 144 (43.9) | ||

| No | 70 (76.09) | 184 (56.1) | ||

| Postpartum depression | 23.207 | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 18 (19.57) | 156 (47.56) | ||

| No | 74 (80.43) | 172 (52.44) | ||

| Breast milk volume | 26.946 | <.001 | ||

| Deficiency | 24 (26.09) | 186 (56.71) | ||

| Adequate | 68 (73.91) | 142 (43.29) | ||

| Participate in health education and other training during pregnancy | 24.902 | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 58 (63.04) | 112 (34.15) | ||

| No | 34 (36.96) | 216 (65.85) | ||

| Husband supports breastfeeding | 23.769 | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 64 (69.57) | 134 (40.85) | ||

| No | 28 (30.43) | 194 (59.15) | ||

| Infant feeding difficulties | 33.397 | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 26 (28.26) | 204 (62.2) | ||

| No | 66 (71.74) | 124 (37.8) | ||

| Infantile diarrhea | 22.134 | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 32 (34.78) | 44 (13.41) | ||

| No | 60 (65.22) | 284 (86.59) | ||

| Lactose intolerance | 23.896 | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 27 (29.35) | 31 (9.45) | ||

| No | 65 (70.65) | 297 (90.55) | ||

| Delectation | 45.568 | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 31 (33.70) | 23 (7.01) | ||

| No | 61 (66.30) | 305 (92.99) | ||

3.3. Comparison of EPDS and PSSS scores between exclusive breastfeeding group and non-exclusive breastfeeding group

The score of EPDS was significantly lower in the exclusive breastfeeding group than that in the non-exclusive breastfeeding group (P < .001), while the score of PSSS was significantly higher than in the exclusive breastfeeding group than that in the non-exclusive breastfeeding group (P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of EPDS and PSSs scores between the groups.

| Group | Cases | EPDS (points) | PSSS (points) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive breastfeeding group | 92 | 8.08 ± 1.03 | 67.32 ± 9.92 |

| Non-exclusive breastfeeding group | 328 | 8.89 ± 1.10 | 60.20 ± 9.54 |

| t | −5.129 | 6.271 | |

| P | <.001 | <.001 |

EPDS = Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale, PSSS = Perceived Social Support Scale.

3.4. Multivariate logistics analysis of the factors influencing breastfeeding

Age (<35 years of age assignment 0, ≥35 years of age assignment 1), educational level (assignment 1 above undergraduate level, assignment 0 below undergraduate level), place of residence (urban assignment 0, rural assignment 1), sunken or flat nipples (yes assignment 1, no assignment 0), breast tenderness (yes assignment 1, no assignment 0), postpartum depression (yes assignment 1, no assignment 0), breast milk volume (adequate assignment 1, deficiency assignment 0), health education during pregnancy (yes assignment 1, no assignment 0), husband support for breastfeeding (yes assignment 1, no assignment 0), infant feeding difficulties (yes assignment 1, no assignment 0), PSSS score (score ≥60 points assignment 1, <60 points assignment 0) infant diarrhea (yes assigned 1, no assigned 0), lactose intolerance (yes assigned 1, no assigned 0), delectation (yes assigned 1, no assigned 0) were used as independent variables. Logistic regression analysis showed that age, education level, sunken or flat nipples, breast tenderness, postpartum depression, breast milk volume, health education during pregnancy, husband support for breastfeeding, PSSS score, infant diarrhea, lactose intolerance, and delectation were the influencing factors of exclusive breastfeeding (P < .05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistics analysis of the factors influencing breastfeeding.

| Factor | β | SE | Walds | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.655 | 0.192 | 11.638 | <.001 | 0.519 (0.357–0.757) |

| Education level | 0.586 | 0.194 | 9.124 | <.001 | 1.797 (1.228–2.628) |

| Place of residence | 0.212 | 0.182 | 1.357 | .221 | 1.236 (0.865–1.766) |

| Sunken or flat nipples | −1.073 | 0.218 | 24.226 | <.001 | 0.342 (0.223–0.524) |

| Breast tenderness | −0.928 | 0.332 | 7.813 | <.001 | 0.395 (0.206–0.758) |

| Postpartum depression | −1.872 | 0.554 | 11.418 | <.001 | 0.154 (0.052–0.456) |

| Breast milk volume | 2.012 | 0.671 | 8.991 | <.001 | 7.478 (2.007–27.859) |

| Participate in health education and other training during pregnancy | 0.772 | 0.206 | 14.044 | <.001 | 2.164 (1.445–3.241) |

| Husband supports breastfeeding | 0.943 | 0.288 | 10.721 | <.001 | 2.568 (1.460–4.514) |

| Infant feeding difficulties | −0.224 | 0.182 | 1.515 | .206 | 0.799 (0.559–1.142) |

| PSSS | 1.433 | 0.412 | 12.098 | <.001 | 4.191 (1.869–9.398) |

| Infantile diarrhea | 0.665 | 0.211 | 9.933 | <.001 | 1.944 (1.286–2.940) |

| Lactose intolerance | 0.781 | 0.215 | 13.195 | <.001 | 2.186 (1.433–3.328) |

| Delectation | 0.572 | 0.182 | 9.878 | <.001 | 1.772 (1.240–2.531) |

PSSS = Perceived Social Support Scale.

4. Discussion

Breastfeeding can reduce the risks of sudden infant death syndrome and infectious diseases, so many countries and related organizations worldwide advocate and encourage breastfeeding.[12] As the most ideal food for infants, breast milk is of great significance for the growth of infants, which can both strengthen the immune function of infants and be helpful for the recovery of mothers’ uterus and the reduction of breast cancer incidence.[13] In recent years, the exclusive breastfeeding rate has increased worldwide, but it is still low due to the many factors that affect it.[14,15]

In this study, the status of twin breastfeeding was analyzed to investigate the influencing factors of exclusive breastfeeding in twin infants, and the exclusive breastfeeding rate of twins was found to be 21.90%. The proportion of non-exclusive breastfeeding increases with increasing age, older mothers with more stressful work will have weaker confidence in breastfeeding, so more mothers choose artificial feeding.[16,17] The influence of education level and region on breastfeeding can be influenced by the fact that women with high education level are more interested in acquiring knowledge about parenting and can use multiple ways to obtain relevant knowledge, therefore are more active in participating in relevant parenting training, while women located in rural areas are more willing to breastfeed due to the influence of traditional beliefs.[18] Breastfeeding without nipple depression or flattening is more common. Women with abnormal nipple status refuse to breastfeed due to factors such as physical changes and fear of affecting beauty, which will prevent effective sucking of infants. The nipple depression or chapped can cause breast pain and psychological fluctuations on mothers in the process of breastfeeding, which can lead to abandonment of breastfeeding. Several studies also suggested that women with abnormal nipple status should be strengthened to increase the training of relevant knowledge and improve the level of breastfeeding.[19–22]

Women with insufficient breast milk may be more eager to give artificial feeding due to their fear of physical condition and infant condition, but this emotion will have a negative impact on maternal lactation.[23] Changes in mental behavior can have a negative effect to weaken breastfeeding self-efficacy beliefs, reducing the enthusiasm of breastfeeding.[24] Studies have confirmed that maintaining a good mentality during breastfeeding can increase confidence in breastfeeding, suggesting that attention should be paid to postpartum depression during hospitalization, while a comfortable and relaxed feeding atmosphere should be provided to help mothers change their roles and encourage them to breastfeed.[25,26] Studies have shown that the higher of the mother mastery of feeding would improve maternal feeding self-efficacy.[27,28] Therefore, medical institutions should strengthen the transmission of breastfeeding health knowledge, further refine breastfeeding guidance, and play the professional advantages of hospitals and community medical institutions.[27,28] With the development of society, most mothers returned to work 6 months after delivery. After returning to work, the care of the child requires family support, and mothers with insufficient family support feel the pressure of work and life, which will have an impact on lactation, and reduce the confidence of breastfeeding.[29,30] Therefore, during discharge education, maternal and family members, especially husbands, should actively carry out publicity and education to understand the significance of social support for breastfeeding confidence, so that families can give maternal more attention, support and understanding.[31,32]

This study also found that the EPDS score of exclusive breastfeeding group was significantly lower than that of non-exclusive breastfeeding group, while the PSSS score was significantly higher than that of non-exclusive breastfeeding group. Further logistic regression analysis showed that age, educational level, nipple depression or flatness, breast tenderness, postpartum depression, breast milk volume, health education during pregnancy, husband supports for breastfeeding, and PSSS score were the influencing factors of exclusive breastfeeding. The existing studies mostly focus on the negative impact of negative emotions on breastfeeding, while the analysis of positive emotions on maternal self-efficacy has not been reported, so further research and analysis are needed.[33,34] Studies have found that the level of social support has an impact on breastfeeding, and women with high levels of social support feel more social attention and have more access to help, thus increasing confidence in breastfeeding and being more persistent in the process of breastfeeding, consistent with the results of this study.[35–37]

Previous studies have mainly focused on the current situation of singleton breastfeeding, and there is no analysis of the status of twin breastfeeding. This study analyzed this and investigated all aspects of factors influencing twin-birth breastfeeding, enriching the research in this field and providing a certain basis for establishing an improved breastfeeding rate. However, this study still has some limitations: First, the major limitation is the cross-sectional design does not allow making causal inferences. Second, all outcomes were self-reported by study participants. Third, the small number of patients included in this study, the single-center study, and the limited range of patient options may have biased the results. In the future, it is necessary to carry out more relevant studies among different races and countries to expand the scope of sampling, and further carry out intervention studies to verify the importance of exclusive breastfeeding.

In conclusion, in our modest attempt to illuminate the significance of twin breastfeeding, we suggest that age, education level, nipple depression or flat, breast tenderness, postpartum depression, breast milk volume, health education training during pregnancy, husband support for breastfeeding, PSSS score, infant diarrhea, lactose intolerance, and delectation were associated with a low rate of exclusive breastfeeding in twin births. Therefore, the corresponding measures are required to promote exclusive breastfeeding.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Shoucui Wang, Chaoli Peng, Daping Wang.

Data curation: Shoucui Wang.

Formal analysis: Shoucui Wang, Xue Xiang, Xujin Guo.

Funding acquisition: Shoucui Wang, Mei Li, Xue Xiang.

Investigation: Shoucui Wang, Mei Li, Xue Xiang, Ya Chen.

Methodology: Shoucui Wang, Mei Li, Xue Xiang, Xujin Guo, Ya Chen.

Project administration: Mei Li, Xue Xiang, Xujin Guo, Chaoli Peng, Daping Wang, Ya Chen.

Resources: Mei Li, Xujin Guo, Ya Chen.

Software: Mei Li, Daping Wang, Ya Chen.

Supervision: Mei Li.

Visualization: Chaoli Peng.

Abbreviations:

- EPDS

- Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale

- PSSS

- perceived social support scale

This study was supported by study on the construction of Jaundice (Item Number: 2021MSXM040).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

How to cite this article: Wang S, Li M, Xiang X, Guo X, Peng C, Wang D, Chen Y. Analysis on the current situation of twin breastfeeding and its influencing factors. Medicine 2023;102:38(e35161).

Contributor Information

Shoucui Wang, Email: 4895605@qq.com.

Mei Li, Email: 34334567@qq.com.

Xue Xiang, Email: 12343544@qq.com.

Xujin Guo, Email: 67578595784@qq.com.

Chaoli Peng, Email: 75875839@qq.com.

Daping Wang, Email: 4895605@qq.com.

References

- [1].Usheva N, Lateva M, Galcheva S, et al. Breastfeeding and overweight in European preschoolers: the ToyBox study. Nutrients. 2021;13:2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tang Q-S. International clinical practice guideline of Chinese medicine anxiety. World J Tradit Chin Med. 2021;7:280. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hirani SAA. Breastfeeding in public: challenges and evidence-based breastfeeding-friendly initiatives to overcome the barriers. Clin Lact. 2021;12:137–44. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bhatt H. Should COVID-19 mother breastfeed her newborn child? A literature review on the safety of breastfeeding for pregnant women with COVID-19. Curr Nutr Rep. 2021;10:71–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Turner S, McGann B, Brockway MM. A review of the disruption of breastfeeding supports in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in five Western countries and applications for clinical practice. Int Breastfeed J. 2022;17:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Szylberg L, Bodnar M, Lebioda A, et al. Differences in the Expression of TLR-2, NOD2, and NF-κB in placenta between twins. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2018;66:463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tahiru R, Agbozo F, Garti H, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers with twins in the tamale metropolis. Int J Pediatr. 2020;2020:5605437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ooki S. Breast-feeding rates and related maternal and infants’ obstetric factors in Japanese twins. Environ Health Prev Med. 2008;13:187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cascone D, Tomassoni D, Napolitano F, et al. Evaluation of knowledge, attitudes, and practices about exclusive breastfeeding among women in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Huang L, Jiang Q, Ren W. Coping style, social support, and psychosomatic symptoms in patients with cancer. Chin Mental Health J. 1996;10:160–6. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Terao R, Nii M, Asai H, et al. Breastfeeding in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia during tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2021;27:756–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Silva JS, Flor-De-Lima F, Soares H. Breastfeeding: prevalence and determining factors at maternity discharge and during the second month of life. Acta Portuguesa de Nutrição. 2021;24:58–62. [Google Scholar]

- [14].DiTomasso D, Wambach KA, Roberts MB, et al. Maternal worry about infant weight and its influence on artificial milk supplementation and breastfeeding cessation. J Hum Lact. 2022;38:177–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Giusti A, Zambri F, Marchetti F, et al. COVID-19 and pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding: the interim guidance of the Italian National Institute of Health. Epidemiol Prev. 2021;45:14–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Joyce CM, Hou SS-Y, Ta BT, et al. The association between a novel baby-friendly hospital program and equitable support for breastfeeding in Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gwartney T, Duffy A. Maintaining safe breastfeeding practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: an overview of the evidence to inform clinical guidelines. Neonatal Netw. 2021;40:140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Awomolo AM, Louis-Jacques A, Crowe S. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis diagnosed during pregnancy associated with successful breastfeeding experience. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2021;14:e241232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Perez MR, de Castro LSA, Chang Y-S, et al. Breastfeeding practices and problems among obese women compared with nonobese women in a brazilian hospital. Women’s Health Rep. 2021;2:219–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Garofoli F, Civardi E, Zanette S, et al. Literature review and an Italian hospital experience about post-natal CMV infection acquired by breast-feeding in very low and/or extremely low birth weight infants. Nutrients. 2021;13:660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dagla M, Mrvoljak-Theodoropoulou I, Karagianni D, et al. Women’s mental health as a factor associated with exclusive breastfeeding and breastfeeding duration: data from a longitudinal study in Greece. Children. 2021;8:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Webber E, Wodwaski N, Courtney R. Using simulation to teach breastfeeding management skills and improve breastfeeding self-efficacy. J Perinat Educ. 2021;30:19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hancock D. The role of breastfeeding in strengthening the immune system. J Health Visit. 2021;9:162–3. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rativa-Alberto D, Camacho-Cruz J, Moreno J, et al. Experience of Home-Based Breastfeeding Support Programs in Two Centers in Colombia. American Academy of Pediatrics, Itasca, IL, USA. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shlomai NO, Kasirer Y, Strauss T, et al. Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections in breastfeeding mothers. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2020010918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Scharff DP, Elliott M, Rechtenwald A, et al. Evidence of effectiveness of a home visitation program on infant weight gain and breastfeeding. Matern Child Health J. 2021;25:676–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Penniston T, Reynolds K, Pierce S, et al. Challenges, supports, and postpartum mental health symptoms among non-breastfeeding mothers. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2021;24:303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Litwan K, Tran V, Nyhan K, et al. How do breastfeeding workplace interventions work? a realist review. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pádua AR, Melo EM, Alvarelhão JJ. An intervention program based on regular home visits for improving maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy: a pilot study in Portugal. Matern Child Health J. 2022;26:575–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ludvigsson J, Faresjö A, Faresjö T. Breastfeeding and cortisol in hair in children. Int Breastfeed J. 2021;16:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zuluaga MI, Otero-Romero S, Rovira A, et al. Menarche, pregnancies, and breastfeeding do not modify long-term prognosis in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2019;92:e1507–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Linares AM, Bailey DF, Ashford K. Enabling nurse students to achieve their breastfeeding goals. Clin Lact. 2020;11:65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Razdan R, Callaham S, Saggio R, et al. Maxillary frenulum in newborns: association with breastfeeding. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162:954–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ventura AK, Lore B, Mireles O. Associations between variations in breast anatomy and early breastfeeding challenges. J Hum Lact. 2021;37:403–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Babic A, Sasamoto N, Rosner BA, et al. Association between breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e200421–21-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Vilar-Compte M, Pérez-Escamilla R, Ruano A. Interventions and policy approaches to promote equity in breastfeeding. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Daou D, Tamim H, Nabulsi M. Assessing the impact of professional lactation support frequency, duration and delivery form on exclusive breastfeeding in Lebanese mothers. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0238735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]