Abstract

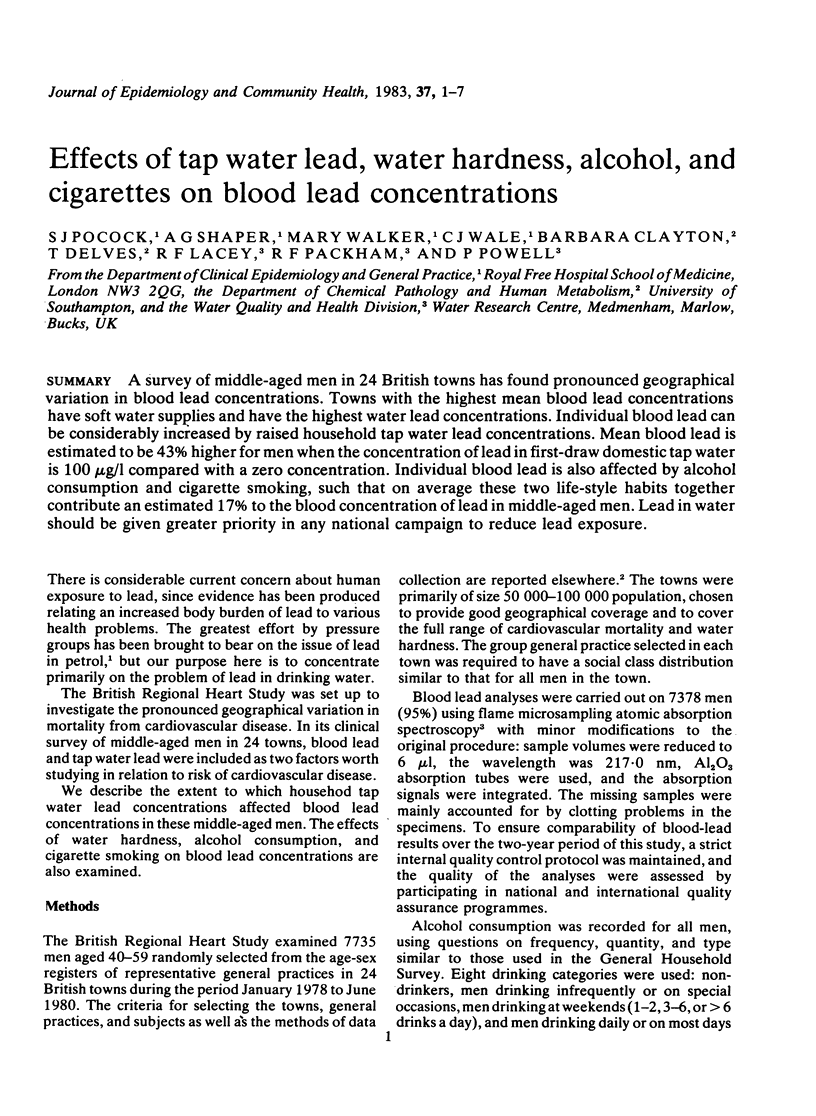

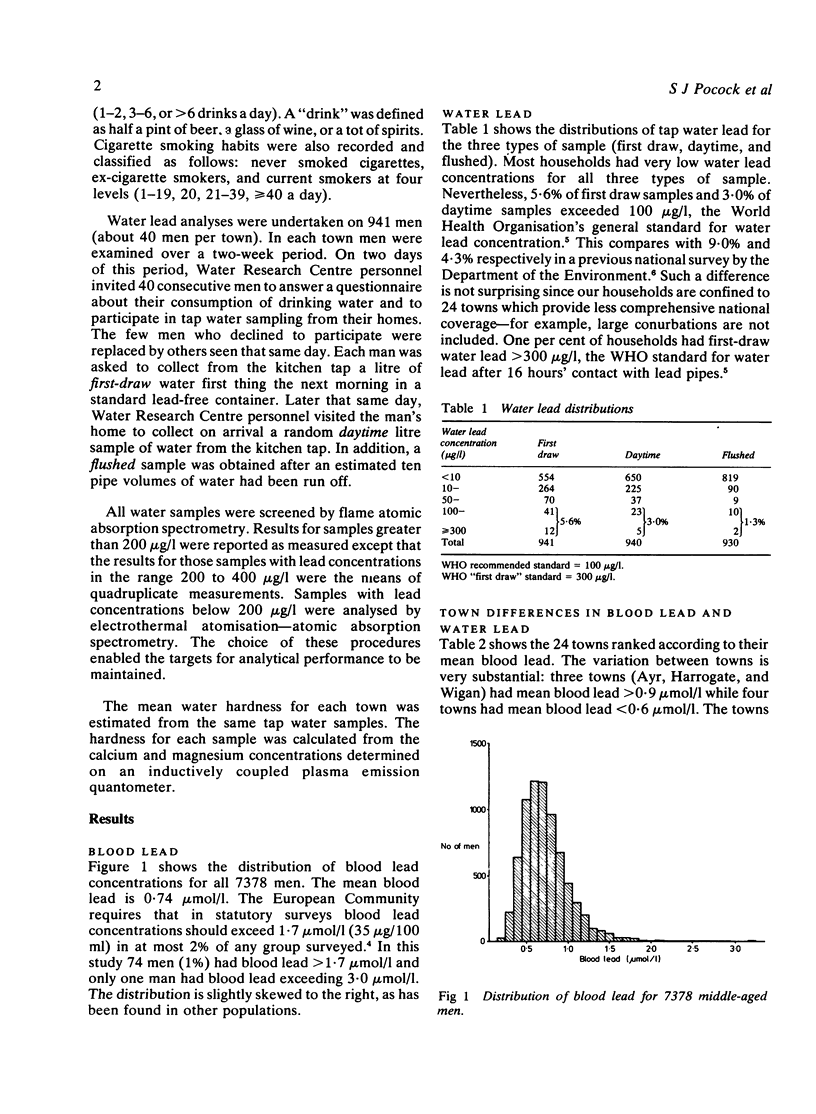

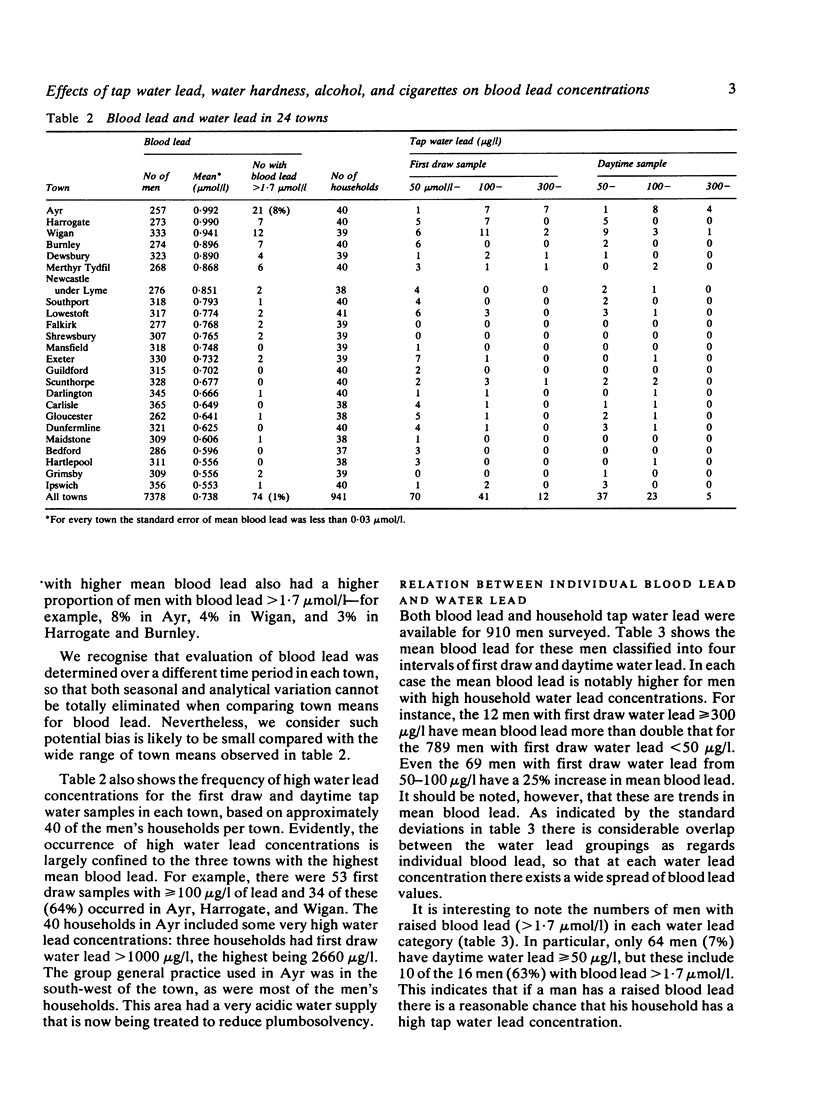

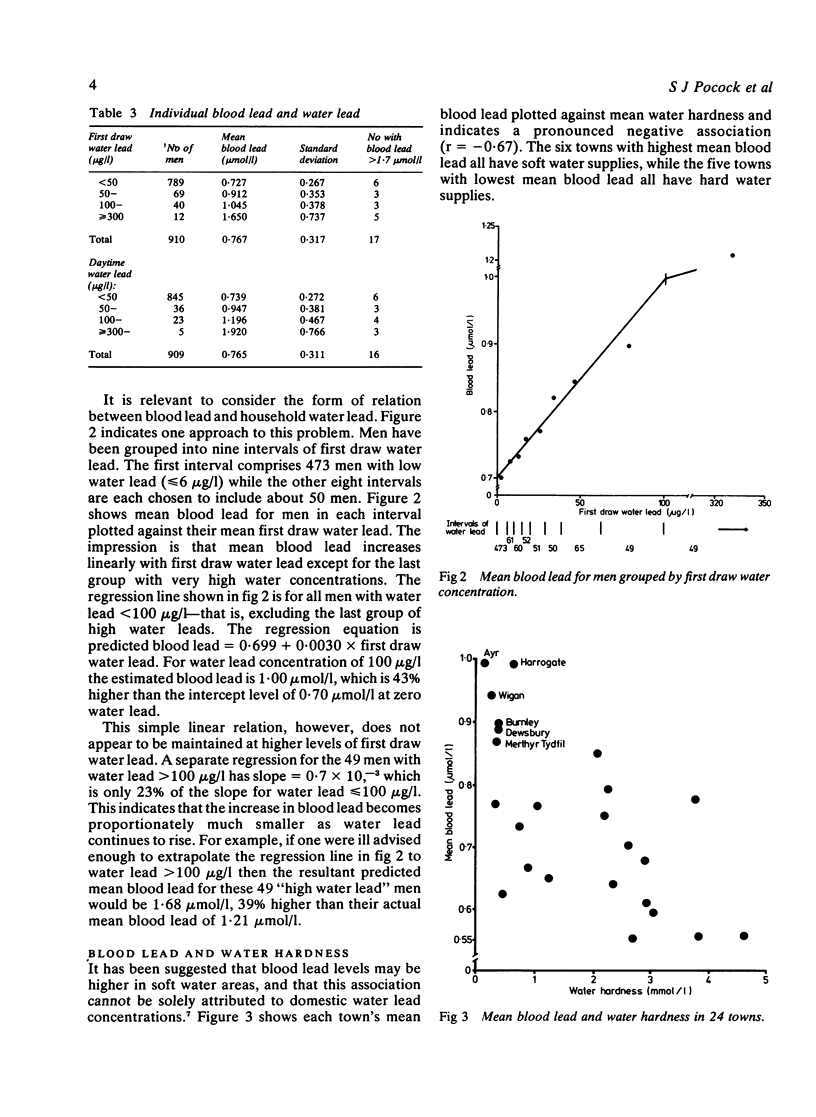

A survey of middle-aged men in 24 British towns has found pronounced geographical variation in blood lead concentrations. Towns with the highest mean blood lead concentrations have soft water supplies and have the highest water lead concentrations. Individual blood lead can be considerably increased by raised household tap water lead concentrations. Mean blood lead is estimated to be 43% higher for men when the concentration of lead in first-draw domestic tap water is 100 micrograms/l compared with a zero concentration. Individual blood lead is also affected by alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking, such that on average these two life-style habits together contribute an estimated 17% to the blood concentration of lead in middle-aged men. Lead in water should be given greater priority in any national campaign to reduce lead exposure.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Delves H. T. A micro-sampling method for the rapid determination of lead in blood by atomic-absorption spectrophotometry. Analyst. 1970 May;95(130):431–438. doi: 10.1039/an9709500431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P., Olsen N. B., Hollnagel H. Influence of smoking and alcohol consumption on blood lead levels. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1981;48(4):391–397. doi: 10.1007/BF00378687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard M. J., Chamberlain A. C. Effect of minerals and food on uptake of lead from the gastrointestinal tract in humans. Hum Toxicol. 1982 Oct;1(4):411–415. doi: 10.1177/096032718200100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. R., Goldberg A., Meredith P. A., Lees R., Low R. A., Pocock S. J. The contribution of drinking water lead to maternal blood lead concentrations. Clin Chim Acta. 1979 Jul 2;95(1):129–133. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(79)90345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. R., Meredith P. A., Campbell B. C., Goldberg A., Pocock S. J. [Contribution of lead in drinking water to blood-lead]. Lancet. 1977 Sep 24;2(8039):661–662. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92528-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock S. J. Factors influencing household water lead: a British national survey. Arch Environ Health. 1980 Jan-Feb;35(1):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Pocock S. J., Walker M., Cohen N. M., Wale C. J., Thomson A. G. British Regional Heart Study: cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged men in 24 towns. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Jul 18;283(6285):179–186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6285.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Pocock S. J., Walker M., Wale C. J., Clayton B., Delves H. T., Hinks L. Effects of alcohol and smoking on blood lead in middle-aged British men. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982 Jan 30;284(6312):299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6312.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H. F., Elwood P. C., Toothill C., Morton M. Blood and water lead in a hard water area. Lancet. 1981 May 9;1(8228):1047–1048. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H. F., Elwood P. C., Welsby E., St Leger A. S. Relationship of blood lead in women and children to domestic water lead. Nature. 1979 Dec 13;282(5740):712–713. doi: 10.1038/282712a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]