Abstract

Purpose:

Exercise and physical activity are recommended to reduce pain and improve joint function in patients with knee OA. However, exercise has dose effects, with excessive exercise accelerating OA development and sedentary behaviors also promoting OA development. Prior work evaluating exercise in preclinical models has typically used prescribed exercise regimens; however, in-cage voluntary wheel running creates opportunities to evaluate how OA progression affects self-selected physical activity levels. This study aims to evaluate how voluntary wheel running following a surgically induced meniscal injury affects gait characteristics and joint remodeling in C57Bl/6 mice. We hypothesize injured mice will reduce physical activity levels as OA develops following meniscal injury and will engage in wheel running to a lesser extent than the uninjured animals.

Methods:

Seventy-two C57Bl/6 mice were divided into experimental groups based on sex, lifestyle (physically active versus sedentary), and surgery (meniscal injury or sham control). Voluntary wheel running data was continuously collected throughout the study and gait data was collected at 3, 7, 11, and 15 weeks after surgery. At endpoint, joints were processed for histology to assess cartilage damage.

Results:

Following meniscal injury, physically active mice showed more severe joint damage relative to sedentary mice. Nevertheless, injured mice engaged in voluntary wheel running at the same rates and distances as mice with sham surgery. Additionally, physically active mice and sedentary mice both developed a limp as meniscal injury progressed, yet exercise did not further exacerbate gait changes in the physically active mice, despite worsened joint damage.

Conclusions:

Taken together, these data indicate a discordance between structural joint damage and joint function. While wheel running following meniscal injury did worsen OA-related joint damage, physical activity did not necessarily inhibit or worsen OA-related joint dysfunction or pain in mice.

Keywords: VOLUNTARY WHEEL RUNNING, OSTEOARTHRITIS, GAIT ANALYSIS, PRECLINICAL MODELS, MENISCAL INJURY

INTRODUCTION

Exercise and physical activity reduce pain and improve joint function in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) (1,2). In fact, guidelines from the OA Research Society International (OARSI) recommend exercise and strength training as non-surgical and non-pharmacological interventions to manage OA-related pain and disability (3). In addition to relieving pain, moderate physical activity can prolong joint function and may slow the progression of joint damage in older adults at risk of developing OA (4,5). Despite this consensus, patients report joint pain as a barrier to engaging in exercise, especially when there is persistent pain (6,7).

Exercise has clear dose effects, where excessive exercise can cause joint damage and accelerate OA development. In rats, high intensity running induces cartilage degeneration, mimicking OA histopathology (8–10). However, a sedentary lifestyle also promotes OA development, with knee immobilization and physical inactivity also leading to cartilage degeneration in rats and guinea pigs (10,11). Following a ‘goldilocks’ principle, moderate exercise and activity can reduce cartilage damage and improve joint function. For example, moderate physical activity in mice protects from joint degeneration and synoviocyte dysfunction, delaying OA onset (12,13). Moderate-intensity running in rats also increases cartilage thickness and chondrocyte number, whereas no running and high-intensity running decrease cartilage thickness and chondrocyte number (14). Finally, moderate treadmill running does not accelerate cartilage degradation in rats with previous OA-related damage (15,16), and in some cases, moderate exercise or cyclical joint loading even attenuates cartilage degradation in rodents (17–19). Combined, these data demonstrate the potential and utility of preclinical models to investigate connections between exercise dose and joint health.

Prior studies evaluating exercise dose typically use prescribed exercise regimens, where animals involuntarily engage in either forced treadmill running or joint loading routines. However, the method of administering exercise and physical activity influences biomechanical and locomotor changes. For example, velocity strongly influences ground reaction forces and gait biomechanics, yet running speed is fixed during treadmill running. In contrast, in-cage running wheels allow for self-selected velocity and voluntary wheel running. Mice, in particular, are highly active animals that will self-administer exercise if provided with an in-cage running wheel. These behaviors create opportunities to investigate whether OA progression becomes a barrier to physical activity, as well as whether self-selected physical activity levels affect OA-related joint remodeling. It is unknown whether a mouse’s self-selected exercise or physical activity level is effective at controlling exercise dose to stay within the beneficial region. Moreover, there are various preclinical OA models that reflect clinical OA phenotypes (post-traumatic, obesity, aging); we selected a surgically-induced meniscal injury to model post-traumatic OA. We hypothesize injured mice will reduce physical activity levels as OA develops following meniscal injury and will engage in wheel running to a lesser extent than the uninjured animals. In doing so, our study addresses gaps in the literature by 1) evaluating whether self-selected physical activity levels are reduced in injured mice as OA progresses and by 2) evaluating whether self-selected physically activity affects OA-related structural damage and joint function in mice.

METHODS

Animals and study design

Seventy-two C57Bl/6 mice (n=36 male, n=36 female, Charles River Laboratories) at 12 weeks old were individually housed with access to food and water ad libitum in an atmosphere-controlled room with a 12 hr light/dark cycle. Mice were divided into an active lifestyle group (in-cage running wheel) and a sedentary lifestyle group (no wheel). Pre-surgery running wheel data were collected for three weeks prior to surgery. Then, mice in each group received either destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) surgery to induce OA or a sham control. Mice were 18 weeks old at the time of surgery. Male and female animals were randomly distributed between lifestyle and surgical groups (n=10/sex/surgery for active mice, n=8/sex/surgery for sedentary mice). Gait data and open-field activity data were collected prior to surgery and at 3, 7, 11, and 15 weeks after surgery. Histological evidence of joint damage was evaluated at 16 weeks after surgery. An a priori sensitivity analysis with 72 total animals, 8 groups, α=0.05, and power=0.8 determined an effect size (f) of 0.19 would be detectable for 5 repeated measures (G-Power). Over the course of the study, one animal died of natural causes and one animal was euthanized due to respiratory issues detected by the University of Florida veterinary care staff; these two animals were eliminated from the study. The experimental design and final group numbers are shown in Supplemental Figure 1 (see Supplemental Digital Content, Experimental design to evaluate physical activity levels and OA progression in C57Bl/6 mice following meniscal injury). All methods described were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and are in accordance with the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care recommendations on animal research.

Voluntary wheel running

Active mice were individually housed in a cage containing an upright solid surface running wheel (4.5 in diameter, Kaytee Silent Spinner Exercise Wheel) with a magnetic reed switch to continuously detect the number of wheel revolutions. Throughout the study, an Arduino device recorded the number of detected wheel revolutions every 10 sec. The running wheel data collected were used to calculate daily running distance, time, and speed. Cages were checked three times per week to ensure reed switches were detecting wheel revolutions, and data were collected from Arduino devices once per week. In the case that reed switches malfunctioned, missing data were excluded from statistical analysis (case entered as N/A). All cages underwent routine cage changes every two weeks based on standard husbandry care.

Animal surgeries

Anesthesia was induced in a 4% isoflurane sleep box, then animals were transferred to a 1%–2% isoflurane mask to maintain anesthesia. Next, the right limb was aseptically prepared with three repeated washes of povidone-iodine and 70% alcohol, ending with a fourth povidone-iodine application. Mice were then transferred to a sterile field. For all surgeries, a skin incision was made from the distal patella to the proximal tibial plateau. The patellar tendon was retracted, and the medial meniscotibial ligament (MMTL) was exposed by deflecting the fat pad. At this point, the surgeon was notified whether the procedure was a sham or DMM surgery to ensure the surgical approach did not vary between groups. For sham animals, the patellar tendon was replaced, and the skin was closed with polydioxanone absorbable suture (PDS, 6.0). For DMM animals, the MMTL was transected and the incision was closed in the same manner as sham animals. All animals received buprenorphine prior to surgery and every 12 hrs out to 48 hrs after surgery (0.1 mg/kg, subcutaneous).

Gait analysis

Rodent gait analysis was conducted using the GAITOR Suite, as previously described (20,21). Briefly, mice freely explore the 40-in-long x 3.75-in-wide open arena at self-selected walking speeds, with videos recorded when the mice walk in front of a high-speed camera (500 frames/s, Phantom Miro Lab 320) at a consistent velocity (less than 10% velocity change during each gait trial). The transparent arena floor is instrumented with force plates (Type 9317B Kistler) and has a mirror below at a 45° angle, allowing simultaneous capture of the side and underneath views of the animal. At each timepoint, the animal order for gait testing was random and a minimum of 10 complete force plate contacts per hind paw were collected for each animal. Calculated gait variables include spatiotemporal parameters (velocity, stance time, stride length, step width, temporal and spatial symmetry, and stance time imbalance) and dynamic parameters (peak vertical force). To ensure repeatable walking patterns, only trials with at least two full gait cycles and velocities between 15 and 75 cm/s were included, resulting in 3,522 spatiotemporal trials and 2,871 dynamic trials. Please see prior methodological reviews for additional details regarding rodent gait characterization (22,23).

Open-field activity

Spontaneous activity and mechanical stimulus avoidance were measured using a custom-built open field monitoring system – with each arena measuring 45 cm x 45 cm x 10 cm. To evaluate mechanical stimulus avoidance, each quadrant of the arena floor was lined with a different grit of sandpaper (60 = coarse), 80 = medium, 150 = fine, or 400 = extra fine) – leaving only a bare section of acrylic in the center. Sandpaper floors were used in the open-field arena to assess whether surgery or exercise would affect the animal’s preference for a coarse or fine texture. Animals were video recorded for 45 minutes while freely exploring an open field arena. Custom MATLAB scripts were used to track the centroid of each animal and evaluate total travel distance and amount of time spent in each region of interest. Four of the regions of interest were in the corners of the arena – one for each grit of sandpaper. The middle region of interest corresponds with the bare acrylic. The final region of interest is the buffer zone between the other 5 regions. This buffer zone was used to capture the amount of time spent between corners.

Histology

At 16 weeks post-surgery, animals were euthanized via CO2 inhalation, with decapitation performed as a secondary method. Following dissection, knees were prepared for histology and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hrs, decalcified in 10% formic acid for 4 days, dehydrated in ethanol, and vacuum infiltrated with paraffin wax. Knees were then sectioned in the frontal plane at 7 μm and stained with safranin-O/fast green. Sections were blindly graded by segmenting joint features to create binarized masks; then using the masks, quantitative histological features were calculated based on the OARSI histopathology recommendations for the mouse (24) (Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Digital Content, Method of joint segmentation to create binarized masks for quantitative grading of histological images). Additionally, the tibial and femoral cartilage were scored according to the OARSI guidelines (25).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.4). Voluntary wheel running was analyzed using a linear mixed effects model where sex, surgery, and timepoint were treated as fixed effects, and animal was treated as a random effect. Gait data were analyzed with a similar linear mixed effects model approach, with sex, surgery, timepoint, and lifestyle (active versus sedentary) as fixed effects, and animal as a random effect. Velocity was included as a fixed effect for velocity-dependent gait parameters (stance time, stride length, and vertical loading). For gait parameters that vary between limbs (stance time and vertical loading), surgery and limb were combined to create a “surgery-limb” factor. Total distance travelled, time spent in each region of the activity monitor, and time spent in corners were analyzed using liner mixed effects models (separate models for males and females) that treated surgery-lifestyle and timepoint as fixed effects and animal as a random effect. For all linear mixed effects models, the significance of fixed effects was analyzed using type III analysis of variance via Satterthwaite’s method (p<0.05 considered significant). When indicated by the analysis of variance, specific differences between fixed effects were assessed via Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons of least squared means. Quantitative histology data were analyzed via 3-way, full-factorial ANOVAs, treating surgery-limb, lifestyle, and sex as factors. Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests were performed when indicated. The nonparametric OARSI scores were analyzed with pairwise comparisons using the Mann-Whitney U test and a Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Voluntary wheel running

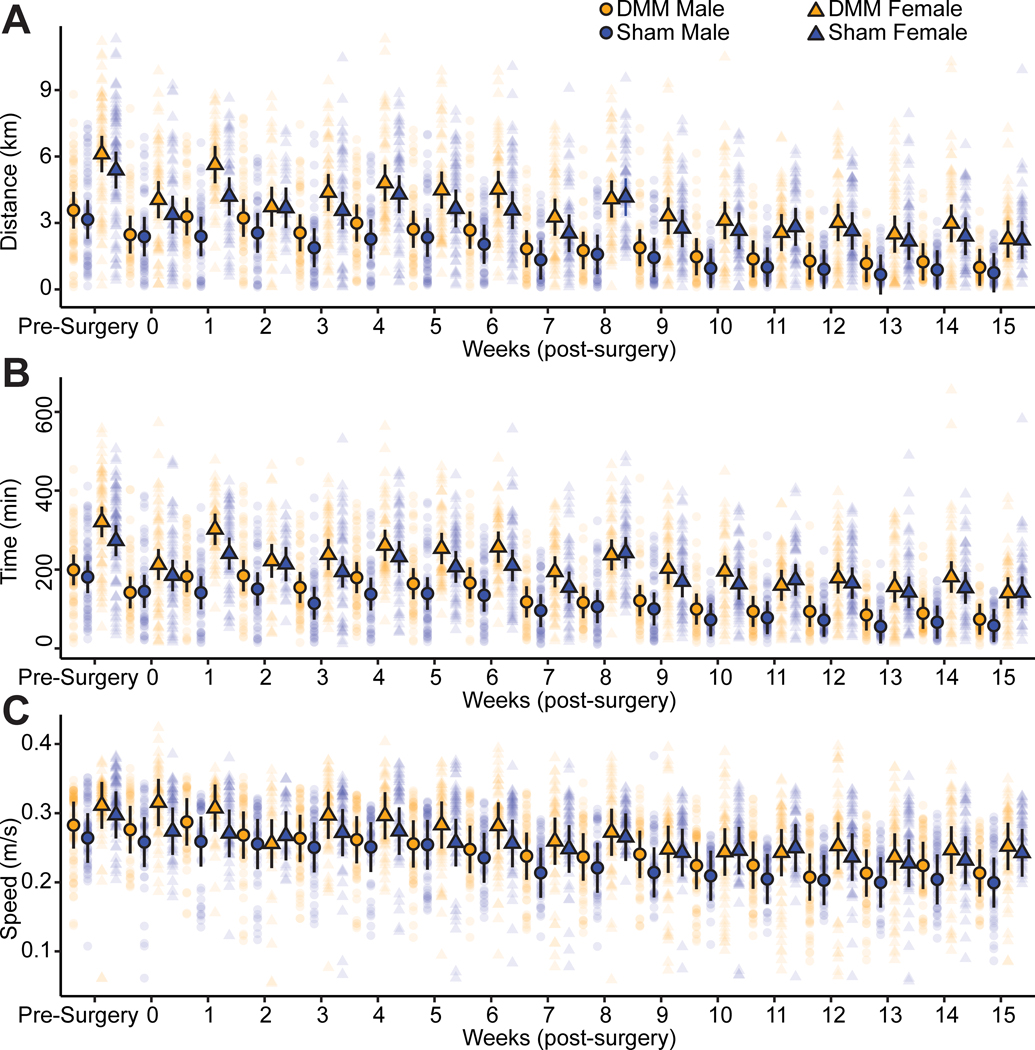

Surprisingly, there were no significant differences between DMM- and sham-operated mice for voluntary wheel running distance, time, or speed (Fig. 1). Female mice ran farther and longer than male mice (p=0.0002 for distance, p<0.0001 for time), and daily running distance and time decreased throughout the study for all animals (p<0.0001). Overall, all mice ran the same daily speeds, and running speed decreased for both sexes throughout the study (p<0.0001). The associated statistical analyses with main effects and interactions for voluntary running data are provided in Supplemental Table 1 (see Supplemental Digital Content).

Figure 1 -.

Self-selected wheel running levels in injured and uninjured C57Bl/6 mice. Individual data points represent daily running distance, time, and speed for each animal. Points outlined in black represent mean values for each group and bars represent 95% confidence intervals. There were no significant differences in running distance (A), time (B), or speed (C) between DMM-operated and sham control mice. Overall, female mice ran farther and longer than male mice, and daily running distances, times, and speeds decreased over the course of the study for all mice.

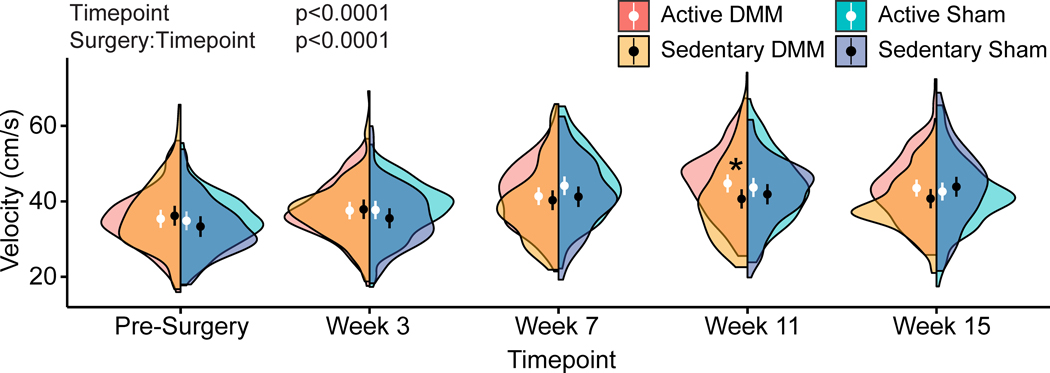

Walking velocity

Following 11 weeks of meniscal injury progression, active DMM mice walked with higher velocities within the GAITOR arena when compared to sedentary DMM mice (p=0.022), indicating physical activity improved walking speeds (Fig. 2). While significant velocity differences between active and sedentary DMM mice were only observed at this timepoint, inspection of the distribution of the data via half violin plots suggests active DMM animals also walk faster than sedentary DMM animals at weeks 7 and 15, though the size of this effect was not greater than the observed variance. Walking velocities generally increased from pre-surgery to week 15 (p<0.0001); however, in previous gait studies, we have consistently observed that rodents increase their walking velocities over time (26,27).

Figure 2 -.

Walking velocities in active and sedentary C57Bl/6 mice following meniscal injury. Velocities for all animals are shown as half violin plots, where circles represent mean velocity and bars represent 95% confidence intervals. At week 11, active DMM mice walked with increased velocities compared to sedentary DMM mice. Moreover, inspection of the distribution of symmetries, via the violin plot, suggests a tendency for increased velocities in active DMM mice compared to sedentary DMM mice at week 7 and week 15.

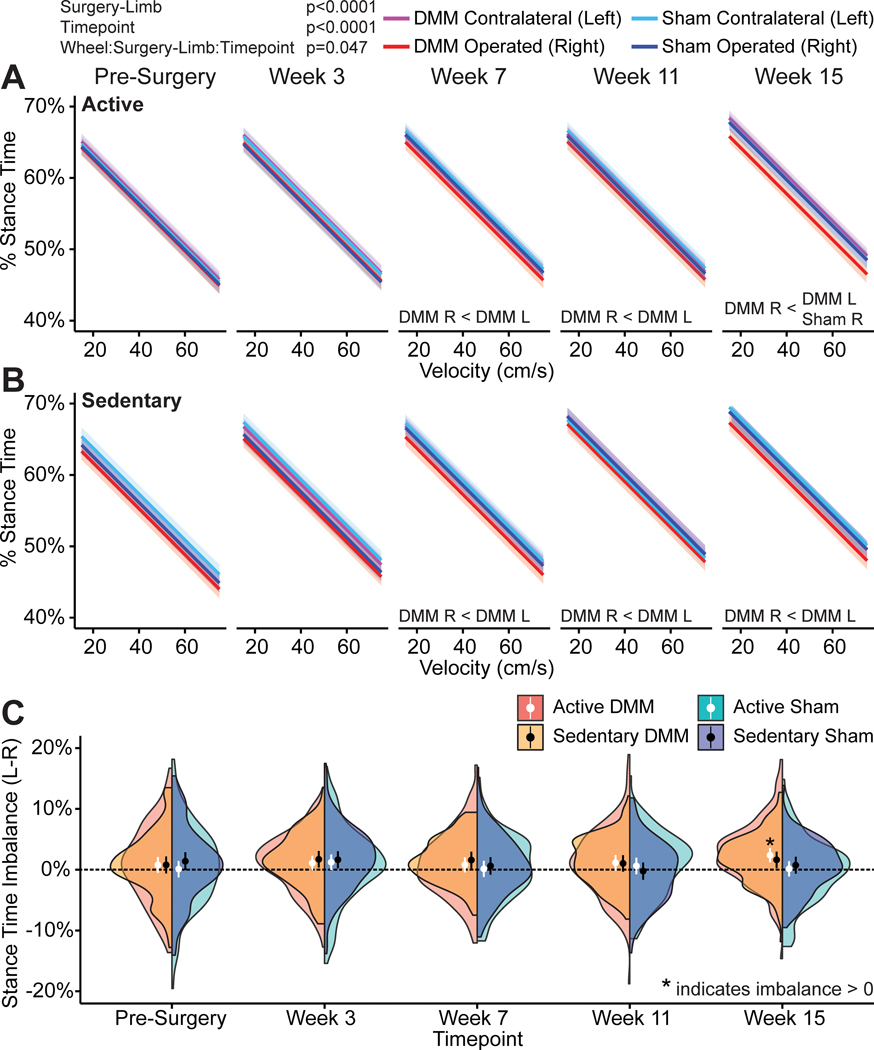

Temporal gait characteristics

As meniscal injury progressed, animals developed temporally asymmetric and imbalanced gaits. Normally, rodents walk with balanced and symmetric gaits, where they spend equal time on both right and left hind limbs and the foot-strike sequence is equally spaced in time. However, at weeks 7, 11, and 15 following meniscal injury, both active and sedentary DMM-operated animals spent less time on the injured limb and more time on the contralateral limb while walking (p=0.047, lifestyle:surgery-limb:timepoint interaction, shown as a velocity-percent stance time relationship in Fig. 3A and Fig. 3B for active and sedentary mice, respectively). These stance time differences between the operated and contralateral limbs were also visualized as imbalanced stance time, where imbalances greater or less than 0 indicate an imbalanced gait. At week 15, stance time imbalance was significantly greater than 0 for the active DMM animals (p=0.00014 with Bonferroni corrected t-test for 20 comparisons, Fig. 3C). While not statistically significant, the distribution of the half violin plot again indicates stance time imbalance also trending towards greater than 0 for the sedentary DMM animals (Fig. 3C), but this effect size is not greater than the observed variance. Moreover, percent stance time on the DMM-operated limb was lower than percent stance time on the sham-operated limb for active mice at week 15 (p=0.0092, Fig. 3A). While not statistically significant, percent stance time on the DMM-operated limb also tended to be lower than percent stance time on the sham-operated limb for sedentary mice at week 15 (p=0.065, Fig. 3B).

Figure 3 -.

Percentage stance times and stance time imbalances in C57Bl/6 mice following meniscal injury. Percentage stance time describes the time the foot is in contact with the ground (stance time) during a complete gait cycle (stance time + swing time); this term is also known as limb duty factor. Here, percentage stance time is plotted against velocity with 95% confidence bands on the mean predicted slope; for clarity, individual data points are not shown. At weeks 7, 11, and 15 following meniscal injury, active and sedentary DMM-operated animals developed imbalanced gaits and spent more time on the uninjured limb and less time on the injured limb while walking (A, B). Additionally, active DMM mice spent less time on the injured limb compared to the operated limb in sham animals and sedentary DMM mice tended to spend less time (p=0.065) on the injured limb compared to the operated limb in sedentary sham animals. Stance time imbalance is also shown over time for both DMM and sham operated animals as half violin plots, where circles represent mean velocity and bars represent 95% confidence intervals (C). Here, stance time imbalance is greater than 0 for the active DMM animals at week 15, and the distribution of the half violin plot for sedentary DMM animals at week 15 indicates stance time imbalance is tending towards greater than 0.

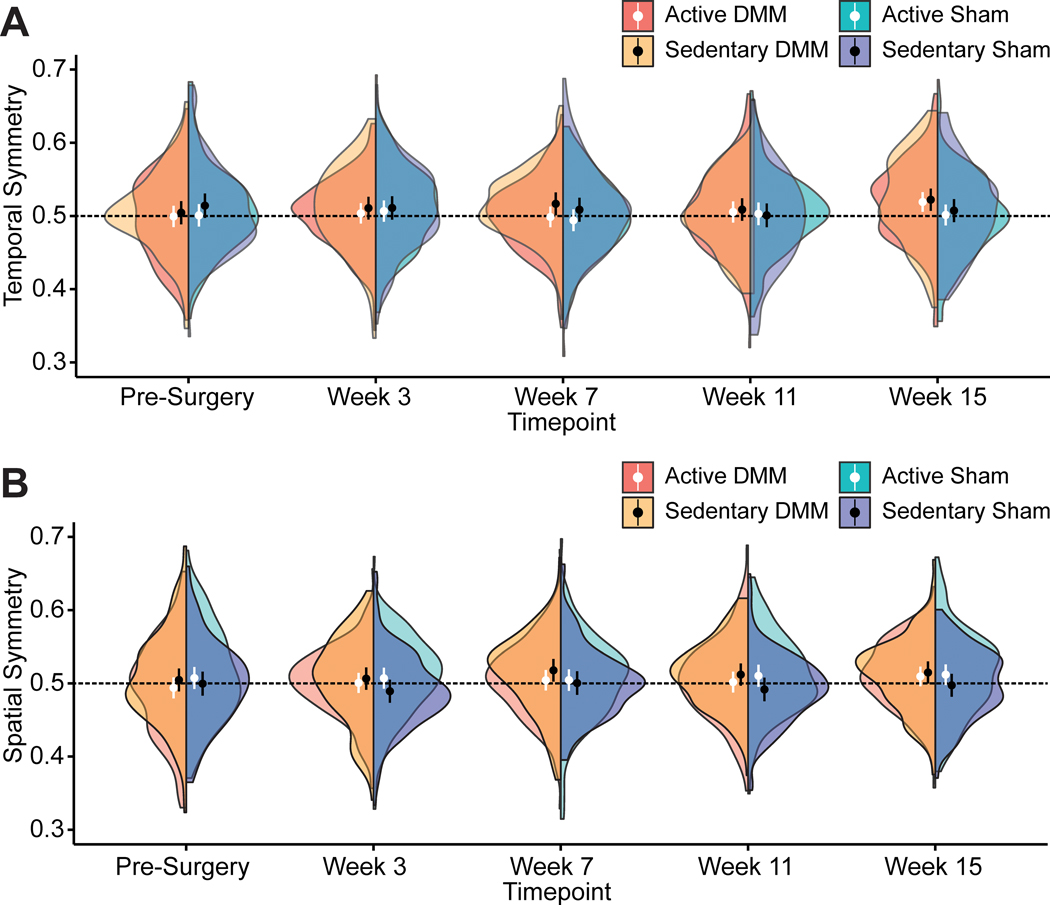

In addition to imbalanced stance times, animals appeared to develop temporally asymmetric gaits (Fig. 4A). Temporal symmetry describes the synchronicity of the foot-strike sequence in time. Normally, foot strikes are evenly spaced in time, with a right foot-strike occurring halfway between two left foot-strikes (hence, 0.5 is the mathematical definition of a temporally symmetric gait sequence). In our experiment, temporal symmetry was trending towards greater than 0.5 in both active and sedentary DMM animals at week 15, as indicated by the distributions of the half violin plots. This tendency for temporal asymmetry indicates the right foot strike occurred later than expected for both active and sedentary DMM animals, indicating both groups of DMM animals shifted more quickly from the injured to uninjured foot when compared to the shift from uninjured to injured foot.

Figure 4 -.

Gait symmetries in C57Bl/6 mice following meniscal injury. Temporal (A) and spatial (B) symmetry results over time for both DMM and sham animals are shown as half violin plots, where circles represent mean symmetry and bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The black lines at 0.5 indicate the mathematical definition of a symmetric gait pattern. Across all timepoints, there were no instances of statistically significant differences in temporal or spatial symmetry from 0.5 for either the DMM or sham groups. Nonetheless, inspection of the distribution of symmetries, via the violin plot, does suggest a tendency for temporal symmetries greater than 0.5 at week 15 after DMM surgery. Additionally, the distribution of spatial symmetries suggests a tendency for spatial symmetries greater than 0.05 at weeks 7, 11, and 15 after DMM surgery.

Stance times also decreased over time (p<0.0001, timepoint main effect) and overall males had greater stance times than females (p=0.00072, sex main effect). Moreover, the only significant difference in stance time between active and sedentary animals was at week 11, where percent stance times were lower in active DMM mice compared to sedentary DMM mice (p=0.012).

Spatial gait characteristics

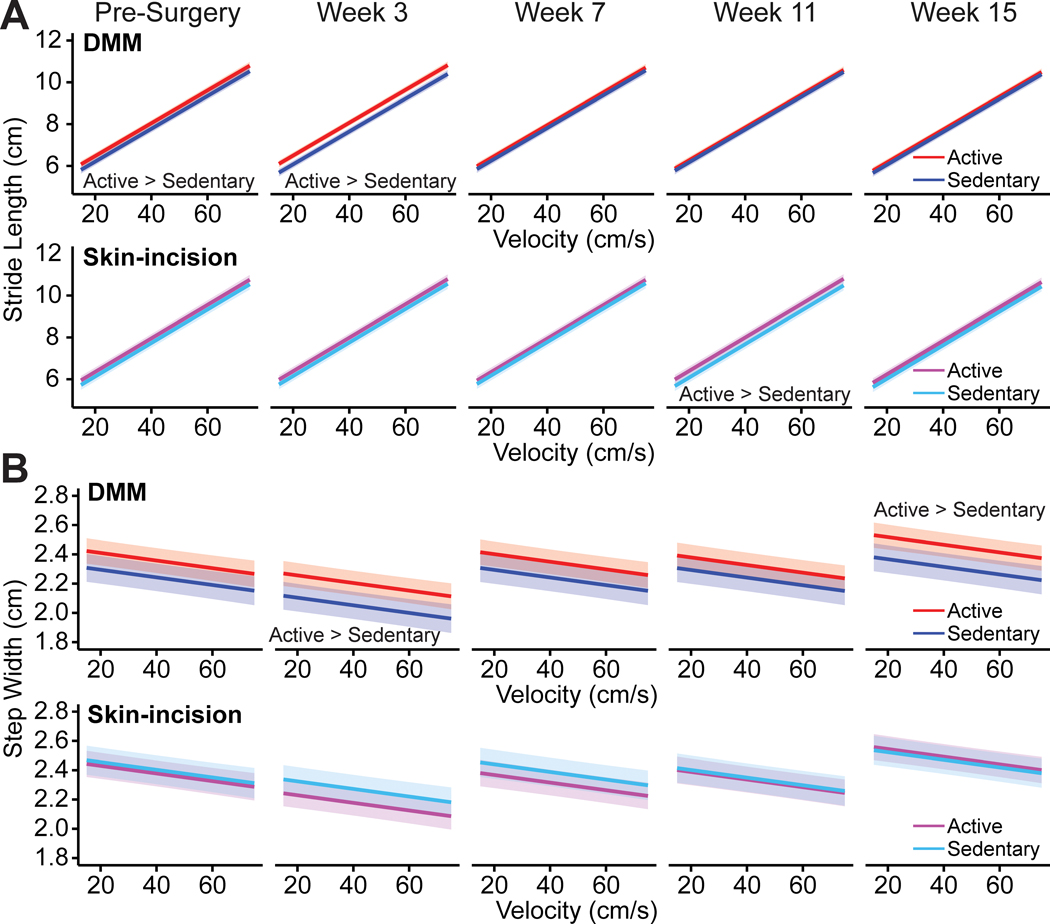

Active DMM animals had longer strides than sedentary DMM animals prior to surgery; however, at later timepoints, there were no differences (Fig. 5A). The active DMM animals were exposed to the running wheels for three weeks prior to pre-surgery gait testing, so this observation of increased stride length in the active animals was not surprising. Active animals walked with longer strides than sedentary animals (p=0.017, lifestyle main effect) and stride length generally decreased over time (p<0.0001, timepoint main effect). There were a few instances of stride length differences between active and sedentary animals for the DMM and sham groups over time (p<0.0001, surgery:lifestyle:timepoint interaction, Fig. 5A, B). Active DMM animals initially had longer strides than sedentary DMM animals; however, at later timepoints, there were no differences (Fig. 5A). Active sham animals had longer strides than sedentary sham animals at week 11, but not at any other timepoint (Fig. 5B). Overall, after controlling for velocity effects, there were no stride length differences between DMM and sham animals or between male and female animals.

Figure 5 -.

Stride lengths and step widths in C57Bl/6 mice following meniscal injury. Stride length is plotted against velocity for DMM (A) and sham surgery (B) animals. Bands represent 95% confidence intervals on the mean predicted slope; for clarity, individual data points are not shown. For stride length, the surgery:lifestyle:timepoint interaction is significant, with longer strides in active DMM animals compared to sedentary DMM animals at baseline and week 3, and longer strides in active sham surgery animals compared to sedentary sham surgery animals at week 11. Step width is plotted against velocity for DMM (C) and sham surgery (D) animals. Bands represent 95% confidence intervals; for clarity, individual data points are not shown. For step width, the surgery:lifestyle:timepoint interaction is significant, with wider steps in active DMM animals compared to sedentary DMM animals at weeks 3 and 15. There were no step width differences between active and sedentary sham surgery animals.

Males walked with wider steps than females (p=0.013, sex main effect). Step widths also varied across time (p<0.0001, timepoint main effect), with animals walking with narrower steps immediately following meniscal injury at week 3 and progressing to wider steps at week 15. There were a few instances of step width differences between active and sedentary DMM animals across time; however, there were no step width differences between active and sedentary sham animals (p<0.0001, surgery:lifestyle:timepoint interaction, Fig. 5C, D). Here, active DMM animals had wider steps than sedentary DMM animals at weeks 3 and 15 (Fig. 5C).

Spatial symmetry describes the positioning of footsteps, where normally the right foot placement is approximately halfway between two left footsteps in space (0.5 is the mathematical definition of spatially symmetric). Here, there were no instances of spatial symmetries being different from 0.5 for either the DMM or sham groups across all timepoints (Fig. 4B). However, inspection of the distribution of the data via half violin plots again suggests spatial symmetry values are trending towards greater than 0.5 at weeks 7, 11, and 15 in DMM animals. This increase in spatial symmetry values above 0.5 indicates steps in the DMM animals are becoming spatially asymmetric with a longer step length from the uninjured to the injured limb compared to the step length from the injured to the uninjured limb.

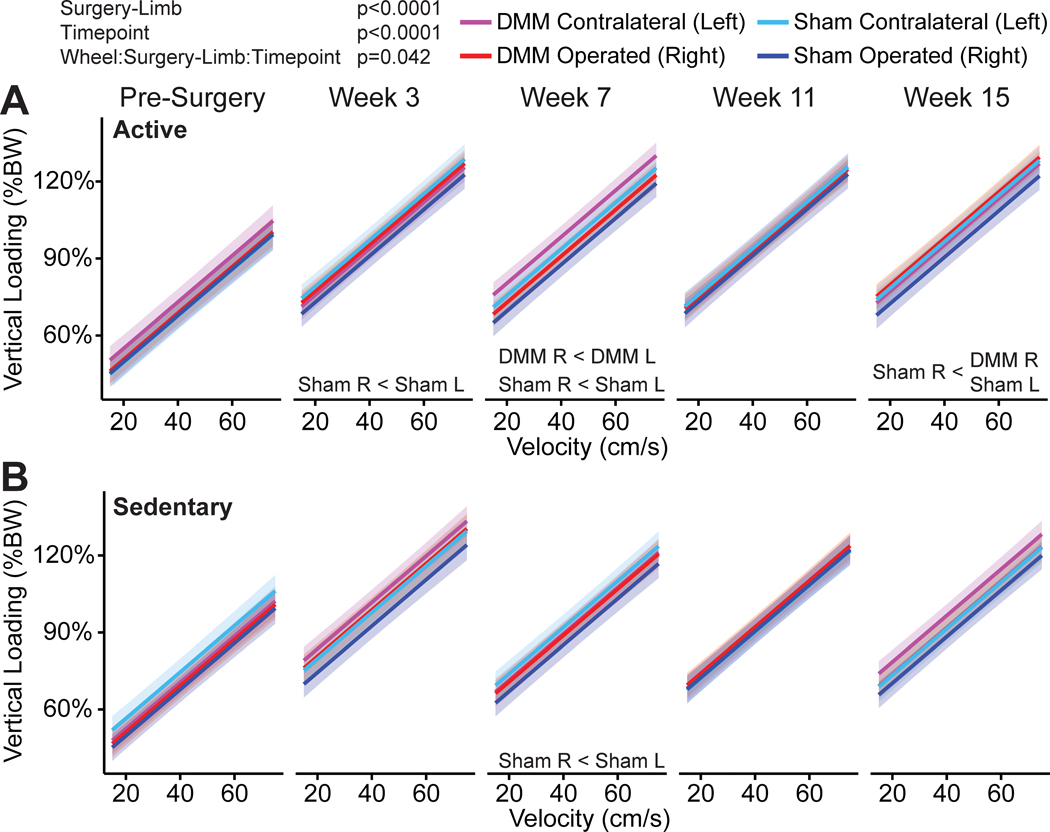

Limb loading characteristics

Vertical loading data is shown in Figure 6. For vertical loading, there was a significant interaction effect of lifestyle:surgery-limb:time (p=0.042). Vertical loading was lower in the injured limb compared the contralateral limb for active DMM animals at week 7; however, vertical loading was also lower in the operated limb compared to the contralateral limb for the active sham animals at weeks 3, 7, and 15. There were no differences in vertical loading between the injured and contralateral limbs for sedentary DMM animals; however, vertical loading was lower in the operated limb compared to the contralateral limb for the sedentary sham animals at week 7. Based on the least squares means comparisons from the linear mixed effects model, there was an estimated 1.7% difference in vertical loading between the operated and contralateral limb for DMM animals and an estimated 4.2% difference in vertical loading between the operated and contralateral limb for sham animals. Additionally, there were no significant interactions between surgery-limb:timepoint, sex:surgery-limb, or wheel:surgery-limb.

Figure 6 -.

Vertical loading in C57Bl/6 mice following meniscal injury. Vertical loading is plotted against velocity for the surgery-limb main effect and bands represent 95% confidence intervals on the mean predicted slope. For clarity, individual data points are not shown. Vertical was lower in the operated limb compared to the contralateral limb for active DMM animals at week 7 and for active sham surgery animals at weeks 3, 7, and 15. Vertical loading was lower in the operated limb compared to the contralateral limb for sedentary sham surgery animals at week 7. (%BW=percent body weight)

Open-field activity

Supplemental Figure 3 (see Supplemental Digital Content) shows the open field activity results. No surgery or lifestyle effects were observed for total distance travelled for male mice (S3A) or female mice (S3B). Time spent in the corners is a measure of anxiety-like behavior, and surgery affected the time spent in the corners, with active sham males spending less time in the corners than active DMM males at weeks 3 and 7 and sedentary sham males spending less time in the corners than sedentary DMM males at weeks 3, 7, and 15. No group differences were observed for time spent in corners for female mice (S3D). To assess the effects of surgery and lifestyle on the animal’s preference for floor texture, the amount of time spent on each sandpaper texture was assessed. Wheel running affected the time spent on the coarse textured floor for male animals, with sedentary DMM animals spending less time in this region compared to active DMM animals at weeks 7, 11, and 15 (S3E). No group differences were observed for the female mice in the coarse textured region of interest (S3F) and no group differences for male or female mice in medium, fine, and extra fine textures.

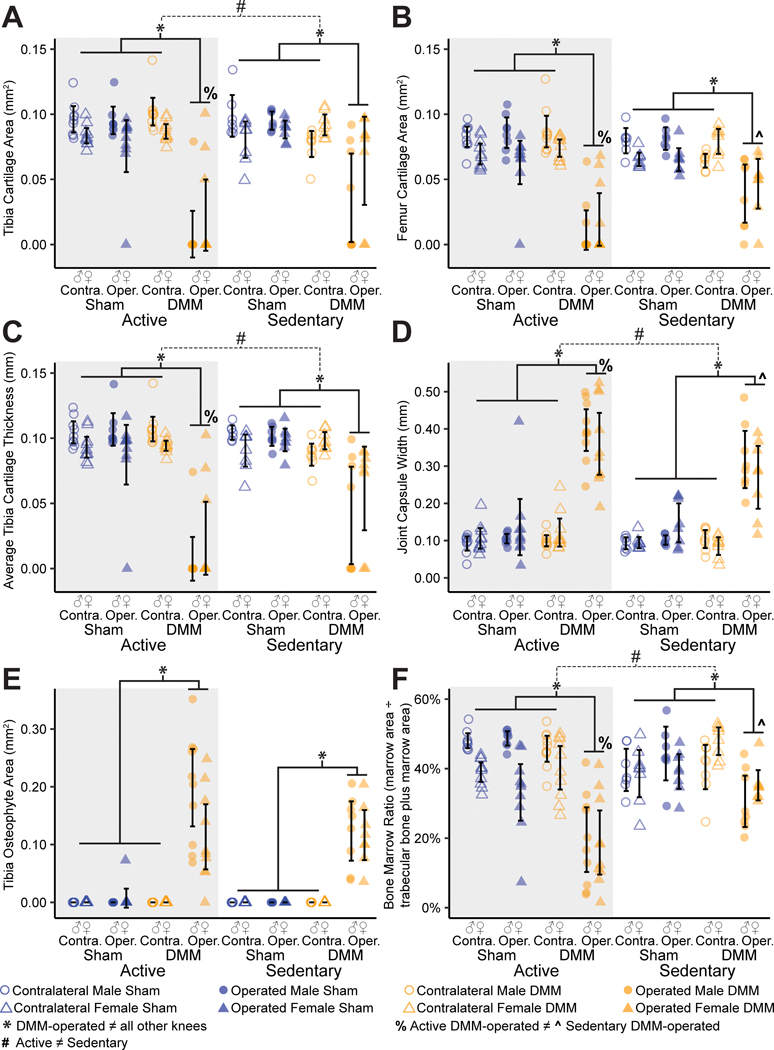

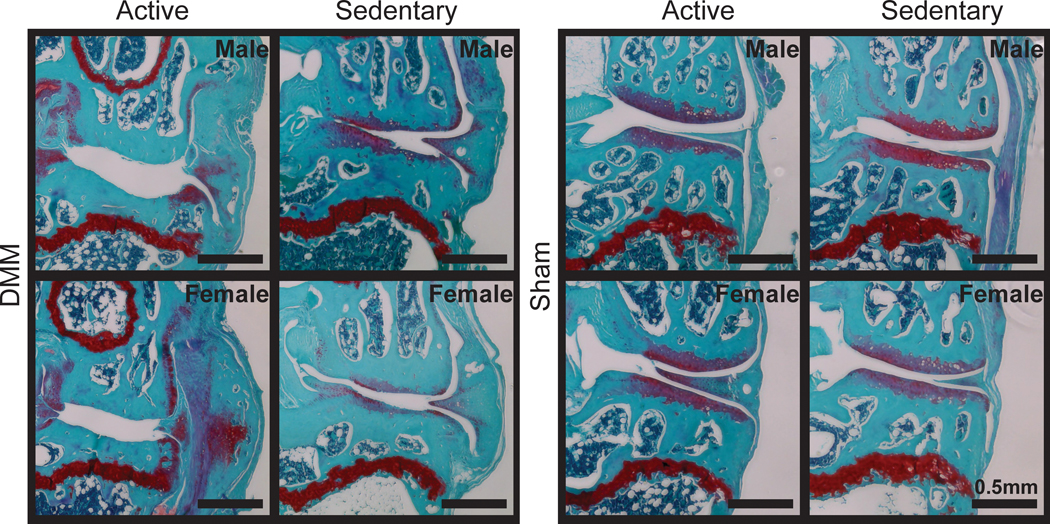

Histology

Histology confirmed joint damage in the medial compartment of all DMM-operated knees, with visual evidence of cartilage loss, joint capsule thickening, and osteophyte formation (Fig. 7). Moreover, joint damage following injury was more severe in animals with access to a running wheel relative to sedentary animals. Instead of exercise attenuating OA progression, voluntary running exacerbated cartilage degradation and loss. Visually, active animals had almost no tibial cartilage remaining after 16 weeks of meniscal injury. Quantitative histological grading supported these observations, indicating more severe joint damage in active DMM-operated knees compared to sedentary DMM-operated knees (Fig. 8). Here, tibial and femoral cartilage loss were greatest in DMM-operated right knees, indicated by reduced cartilage areas (p<0.0001 for tibial and femoral cartilage, Fig. 6 A, B). Moreover, active DMM-operated knees had greater tibial and femoral cartilage loss compared to sedentary DMM-operated knees (p=0.0002 for tibial cartilage, p<0.0001 for femoral cartilage). Additionally, tibial cartilage was thinner in DMM-operated knees compared to all other knees (p<0.0001) and thinner in DMM-operated active knees compared to DMM-operated sedentary knees (p=0.00013, Fig. 8C). Finally, total affected cartilage width (including proteoglycan loss) and cartilage matrix loss width (cartilage loss, not including proteoglycan loss) were greater in DMM-operated active knees when compared to DMM-operated sedentary knees.

Figure 7 -.

Representative histological images of active and sedentary C57Bl/6 mice. Images are in the frontal plane of the medial compartment for the operated (right) knees. All DMM knees show evidence of cartilage damage, joint capsule thickening, and osteophyte formation. Compared to sedentary DMM knees, active DMM knees show severe tibial and femoral cartilage loss. Moreover, active DMM knees appear to have a dense bone plate with smaller and fewer bone marrow spaces compared to sedentary DMM knees.

Figure 8 -.

Quantitative histological grading following meniscal injury in active and sedentary mice. DMM-operated knees have greater tibial (A) and femoral (B) cartilage loss compared to all other knees, with increased cartilage loss in active versus sedentary DMM-operated knees. DMM-operated knees have thinner tibial cartilage compared to all other knees, with thinner tibial cartilage in active versus sedentary DMM-operated knees (C). DMM-operated knees have thicker synovial capsule compared to all other knees, with thicker synovial capsule in active versus sedentary DMM-operated knees (D). DMM-operated knees show osteophyte formation along the medial margins of the tibial plateau (E). DMM-operated knees have lower bone marrow ratios (bone marrow area divided by total trabecular bone plus marrow area) compared to all other knees, with lower subchondral bone marrow ratios in active versus sedentary DMM-operated knees.

Non-cartilage measures also indicated more severe joint damage in active DMM-operated knees. The synovial capsule was thicker in DMM-operated knees compared to all other knees (p<0.0001) and thicker in active DMM-operated knees compared to sedentary DMM-operated knees (p<0.0032, Fig. 8D). Osteophytes were observed along the medial margins of the tibial plateau in all DMM-operated knees (Fig. 8E). Finally, the bone marrow ratio (bone marrow area divided by calcified bone plus marrow area) was lowest in DMM-operated knees compared to all other knees (p<0.0001) and lower in DMM-operated active knees compared to DMM-operated sedentary knees (p<0.0001, Fig. 8F). Here, a lower bone marrow ratio indicates smaller and fewer marrow spaces in the subchondral bone region. Visually, this appeared as dense, calcified bone in the subchondral bone region of active DMM-operated knees. The associated statistical analyses with main effects and interactions for quantitative histological data are provided in Supplemental Table 3 (see Supplemental Digital Content).

OARSI scores indicated greater tibial and femoral cartilage damage in DMM-operated knees (Supplemental Figure 4, Supplemental Digital Content, ). However, OARSI scores did not detect worsened cartilage damage in the DMM-operated active knees compared to the DMM-operated sedentary knees.

DISCUSSION

After 16 weeks of meniscal injury progression, injured mice showed severe histological evidence of OA; as such, it was surprising to see injured mice engage in voluntary wheel running at the same rates and distances as uninjured mice. Moreover, both physically active and sedentary animals developed a limping gait pattern after meniscal injury; however, physical activity did not exacerbate gait changes despite the increased joint damage. Together, these findings indicate a discordance between structural joint damage and joint function, as worsened joint damage related to wheel running after joint injury does not inhibit physical activity levels or substantially impair gait in mice.

Despite receiving a meniscal injury, DMM-operated mice had comparable physical activity levels to sham control mice, even as OA progressed. Females ran farther and longer than males; this was expected based on previous reports (28). Additionally, daily running distances were consistent with previous findings, as females averaged between 3–6 km and males averaged between 1–3 km per night (12,28–30). Furthermore, progressive decreases in wheel running over time were consistent with prior reports (12,30–32). However, as OA progressed, we expected injured animals to decrease wheel running compared to uninjured animals, especially given the severe histological evidence of OA at the end of the study. This was not observed, as injured animals continued to run just as far as uninjured animals throughout the entire study.

Mouse gait patterns are normally symmetric; however, damage in the knee can result in compensatory gait patterns. Here, DMM-operated mice developed antalgic gait patterns. Colloquially, an antalgic gait is a limp, where the animal typically avoids bearing weight on the injured limb. In general, antalgic gaits are represented by temporal asymmetries and imbalanced stance times. In our findings, DMM animals began to use antalgic patterns at week 7, with the severity of the limp increasing by week 15. This is evidenced by reduced stance times on the injured limb compared to the contralateral limb and by temporal asymmetry. Moreover, active DMM animals had stance time imbalances significantly greater than 0 at week 15 compared to sedentary DMM animals with stance time imbalances trending towards greater than 0 at week 15 (Fig. 3C). This finding of greater stance time imbalance in the active DMM animals compared to sedentary DMM animals could indicate reduced limb function as a result of wheel running; however, gait parameters should not be interpreted in isolation when evaluating improved or worsened gait patterns. Quadrupeds also naturally transition to asymmetric half-bounds at higher velocities, thus, in this study, it is not clear if the asymmetry is related to impairment or approaching a transitional gait, given the higher velocities achieved at later time points. Although a limping gait pattern was observed across all DMM animals, physical activity may have marginally improved gait. Here, active DMM animals began walking faster than sedentary DMM animals at week 11, with a tendency for active DMM animals to also walk faster than sedentary DMM animals at weeks 7 and 15, indicating physical activity could improve walking velocity. Additionally, at certain timepoints active animals had longer strides and wider steps compared to sedentary animals. One measure of gait stability in quadrupeds is the support polygon (33). Here, the location of the limbs in ground contact creates a ‘support polygon’, where a greater polygon area indicates a more stable base of support. In the active animals, longer strides and wider steps would increase the support area, potentially indicating physical activity helps stabilize the animal while walking. Following DMM surgery, vertical loading decreased in the operated limb compared to the contralateral limb for active animals. This finding was expected, as previous studies show rodents with meniscal injury alter their gait patterns to support less weight on the injured limb while walking (27,34–36). However, active and sedentary sham animals also decreased vertical loading on the operated limb compared to the contralateral limb. To assess the robustness of this finding, we further evaluated a narrower velocity range to examine whether our results were affected by higher velocities (where mice potentially transition to bounding gaits) or affected by lower velocities (where there is potentially a lack of a repeatable gait cycle). Hence, for this sub-analysis, we selected a velocity range of 30–50 cm/s (compared to 15–75 cm/s) and repeated the vertical loading data analysis, yet we observed the same significant surgery-limb main effect and the same estimated effect sizes for both DMM and sham animals. Thus, our vertical loading findings appear to be stable and robust across a range of velocities.

It is unclear why sham animals would have imbalanced vertical loading and reduce weight-bearing on the operated limb. Spatiotemporal findings do not indicate imbalanced or asymmetric gaits in sham animals. The sham procedure could possibly alter the limb, as the patella and patellar tendon are retracted during surgery and the fat pad is bluntly dissected to expose the medial meniscotibial ligament. In both sham and DMM animals, the patella and patellar tendon are put back in place before closing the incision with suture. There is a possibility this procedure could cause fibrosis of the infrapatellar fat pad, which could cause reduced weight bearing on the operated limb of both groups. Unfortunately, we are unable to assess this histologically, as we used frontal sections that make it difficult to identify this region. Thus, while the sham procedure does not appear to cause cartilage or bone damage (Figs. 7 and 8), it is possible the procedure could affect surrounding joint structures (e.g., patella, patellar tendon, or muscle) and alter vertical loading patterns.

Furthermore, meniscal injury and access to a voluntary wheel alter open field behavior in male mice but not females. As seen with the voluntary running wheel data, no group differences in total distance travelled were observed despite meniscal injury. Meniscal injury did affect the amount of time animals spent in the corners, which is associated with increased anxiety. This increased anxiety behavior between injury groups was observed for both the active and sedentary animals at weeks 3 and 7 post-surgery, but only in the sedentary animals at week 15. This suggests that exercise through voluntary wheel running decreased the anxiety effect related to meniscal injury in later stages of disease progression, aligning with prior reports on the benefits of exercise on anxiety. In addition, exercise affected the time spent in the coarse sandpaper region for male mice with meniscal injury at weeks 7, 11, and 15 post-surgery, suggesting sedentary mice in these groups avoided the roughest part of the arena floor more than their active counterparts. Although it is hard to prove the reason for this avoidance, one potential explanation is increased mechanical sensitivity in the sedentary mice.

Though previous studies show moderate exercise and joint loading can slow OA progression, our findings show self-selected wheel running accelerates structural damage. In the healthy joint, the menisci are two wedge-shaped semilunar discs of tissues that help distribute loads across the tibiofemoral joint by converting vertical compressive loads into circumferential tensile forces. Physical activity could exacerbate joint damage and structural adaptations by increasing the frequency of abnormal load distribution in the joint with a destabilized meniscus. In the active DMM animals, increased joint loading due to wheel running could worsen cartilage damage; thus, bony remodeling could occur to stabilize the joint and preserve running ability. However, recent evidence suggests abnormal mechanical loading could initiate subchondral bone remodeling; as such, bony changes could also accelerate cartilage damage and OA pathology in physically active animals (37). Since we are limited with histological data from only the week 16 timepoint, it is unknown whether cartilage or bony changes occurred first in active DMM animals; nevertheless, our findings show physical activity exacerbated structural OA progression following meniscal injury but did not cause additional physical impairment.

Though we hypothesized injured mice would reduce physical activity levels, they continued running to the same extent as uninjured animals. Forced treadmill running at “excessive” or “high-intensity” levels can lead to severe OA-like pathology. However, in our study animals self-select their physical activity levels, making it more challenging to classify running levels as “excessive” versus “moderate” or “light”. Excessive exercise is context-dependent, as here, DMM and sham animals engaged in the same levels of physical activity. In uninjured animals with overall healthy joints, there was little evidence of damage in either the operated or contralateral limb; whereas in DMM animals, exacerbated damage occurred in the injured, but not contralateral knee. Therefore, our findings indicate “excessive” exercise depends on the joint, as this exercise was excessive for the DMM joint but not for the sham-operated joint. As such, our findings support correcting mechanics (e.g., strategies to repair the meniscus) to prevent or delay joint damage following injury, especially in the context of higher physical activity levels.

Exercise-induced analgesia may also explain why active mice engage in voluntary wheel running despite OA development (38,39). Animal models suggest there are central mechanisms, such as the endogenous opioid system, underlying exercise-induced analgesia. Mechanistic studies show naloxone, an opioid receptor antagonist, blocks analgesic effects of exercise in a chemically-induced rat OA model (40) and other chronic pain models (41,42). A recent study in a chemically-induced rat OA model suggests high intensity exercise relieves ongoing OA pain, yet maintains movement-evoked nociception (43). Combined, these findings indicate high rates of running could block ongoing pain, while preserving the nociceptive signaling that protects the joint from overuse injuries. As such, the lack of differences in physical activity levels between injured and uninjured animals may be driven by the potential pain-relieving effects of the natural high activity levels in mice. This could be evaluated in the future by inhibiting these pathways.

Importantly, the method of physical activity in animal models affects exercise-induced analgesia. Most preclinical studies utilize forced exercise regimens, where animals involuntarily engage in treadmill running. While forced treadmill running allows control over the amount of physical activity, it produces a stress component (44). Stress itself produces analgesic effects by activating the central mechanisms discussed above (45); therefore, in-cage voluntary wheel running isolates exercise effects from other stimuli. Voluntary wheel running allows animals to engage in physical activity in a non-stressed, home-cage environment. Animals provided with a running wheel do run farther than the typical distances used for treadmill regimens. These greater distances may explain why we see more severe joint damage in active, injured mice, as they have an increased volume of physical activity compared to involuntary training regimens. Nevertheless, despite the increased joint damage, animals voluntarily engage in running, suggesting possible analgesic effects of exercise, even with severe joint damage. In addition to analgesic effects, exercise has known benefits related to joint structures and OA pathology. Exercise facilitates local joint-level tissue-to-tissue crosstalk, joint clearance, and bone health(46). OA models have also shown impaired muscle function (47); however, exercise training can prevent muscle atrophy (48). Moreover, a recent correlation network analysis shows an association between systemic metabolic factors and knee OA, suggesting physical activity can alter links between the joint and the rest of the body (49). In this way, exercise facilitates overall health, and understanding how exercise regulates both joint and overall health is critical to limiting comorbidities associated with knee OA and chronic joint pain. Thus, while our study shows that the running wheel accelerates joint damage in DMM mice, our results should not be interpreted as exercise is harmful for the OA-affected subject.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, worsened joint structure did not appear to inhibit running ability or correspond with worsened gait compensations. As previously discussed, injured animals ran the same distances, times, and speeds as uninjured animals despite severe joint damage, and all animals developed an antalgic gait following meniscal injury. Our results support the known discordance between structural and symptomatic OA, as active, injured animals had no change in physical activity levels despite more severe joint damage. Prior clinical reports show structural and symptomatic OA are not linearly related, as structural damage is a poor predictor of OA pain (50). Thus, even though OA-related structural changes are worse in active animals, our results do not demonstrate physical activity reduces joint function or gait in injured mice. Overall, these results indicate that self-selected physical activity in mice can worsen structural OA progression but may not necessarily inhibit or worsen OA-related joint dysfunction or pain.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 - Experimental design to evaluate physical activity levels and OA progression in C57Bl/6 mice following meniscal injury

Figure S2 - Method of joint segmentation to create binarized masks for quantitative grading of histological images

Figure S3 - Data visualization of open field activity

Figure S4 - OARSI scores following meniscal injury in active and sedentary mice, showing DMM-operated knees have greater tibial (A) and femoral (B) cartilage loss compared to all other knees

Table S1 - Statistical analysis with main effects and interactions for voluntary wheel running data

Table S2 - Summary of number of total gait trials included in the analysis for each group at each timepoint

Table S3 - Statistical analysis for quantitative histological data following meniscal injury in physically active and sedentary male and female C57BL/6 mice

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank OrthoBME lab members for their assistance with biweekly animal cage changes. This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institute of Health under grant R01AR071431. This work was also supported by student fellowships from the Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering (KMC, JLG), the J. Crayton Pruitt Family Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Florida (KMC, JLG), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institute of Health under grants T34GM137869 and T34GM145447 (YCP), and the National Science Foundation under grant DGE-1842473 (JLG).

Conflict of Interest and Funding Source:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institute of Health under grant R01AR071431. This work was also supported by student fellowships from the Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering (KMC, JLG), the J. Crayton Pruitt Family Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Florida (KMC, JLG), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institute of Health under grants T34GM137869 and T34GM145447 (YCP), and the National Science Foundation under grant DGE-1842473 (JLG). The authors have no conflicts to disclose. The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose. The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Juhl C, Christensen R, Roos EM, Zhang W, Lund H. Impact of exercise type and dose on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(3):622–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van Der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(24):1554–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(3):363–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chmelo E, Nicklas B, Davis C, Legault C, Miller GD, Messier S. Physical activity and physical function in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(6):777–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batsis JA, Germain CM, Vásquez E, Zbehlik AJ, Bartels SJ. Physical activity predicts higher physical function in older adults: the Osteoarthritis Initiative. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13(1):6–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petursdottir U, Arnadottir SA, Halldorsdottir S. Facilitators and barriers to exercising among people with osteoarthritis: a phenomenological study. Phys Ther. 2010;90(7):1014–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone RC, Baker J. Painful choices: a qualitative exploration of facilitators and barriers to active lifestyles among adults with osteoarthritis. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36(9):1091–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckett J, Jin W, Schultz M, et al. Excessive running induces cartilage degeneration in knee joints and alters gait of rats. J Orthop Res. 2012;30(10):1604–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franciozi CES, Tarini VAF, Reginato RD, et al. Gradual strenuous running regimen predisposes to osteoarthritis due to cartilage cell death and altered levels of glycosaminoglycans. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(7):965–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ni GX, Zhou YZ, Chen W, et al. Different responses of articular cartilage to strenuous running and joint immobilization. Connect Tissue Res. 2016;57(2):143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace IJ, Bendele AM, Riew G, et al. Physical inactivity and knee osteoarthritis in guinea pigs. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(11):1721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubbard-Turner T, Guderian S, Turner MJ. Lifelong physical activity and knee osteoarthritis development in mice. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(1):33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castrogiovanni P, Di Rosa M, Ravalli S, et al. Moderate physical activity as a prevention method for knee osteoarthritis and the role of synoviocytes as biological key. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ni GX, Liu SY, Lei L, Li Z, Zhou YZ, Zhan LQ. Intensity-dependent effect of treadmill running on knee articular cartilage in a rat model. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:172392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boudenot A, Presle N, Uzbekov R, Toumi H, Pallu S, Lespessailles E. Effect of interval-training exercise on subchondral bone in a chemically-induced osteoarthritis model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(8):1176–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai LC, Cooper ES, Hetzendorfer KM, Warren GL, Chang YH, Willett NJ. Effects of treadmill running and limb immobilization on knee cartilage degeneration and locomotor joint kinematics in rats following knee meniscal transection. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(12):1851–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galois L, Etienne S, Grossin L, et al. Dose–response relationship for exercise on severity of experimental osteoarthritis in rats: a pilot study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(10):779–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iijima H, Aoyama T, Ito A, et al. Effects of short-term gentle treadmill walking on subchondral bone in a rat model of instability-induced osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(9):1563–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holyoak DT, Chlebek C, Kim MJ, Wright TM, Otero M, van der Meulen MCH. Low-level cyclic tibial compression attenuates early osteoarthritis progression after joint injury in mice. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(10):1526–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kloefkorn HE, Pettengill TR, Turner SMF, et al. Automated gait analysis through hues and areas (AGATHA): a method to characterize the spatiotemporal pattern of rat gait. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45(3):711–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs BY, Lakes EH, Reiter AJ, et al. The open source GAITOR suite for rodent gait analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs BY, Kloefkorn HE, Allen KD. Gait analysis methods for rodent models of osteoarthritis. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18(10):456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakes EH, Allen KD. Gait analysis methods for rodent models of arthritic disorders: reviews and recommendations. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(11):1837–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glasson SS, Chambers MG, van den Berg WB, Little CB. The OARSI histopathology initiative - recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the mouse. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18 Suppl 3:S17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pritzker KPH, Gay S, Jimenez SA, et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(1):13–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kloefkorn HE, Jacobs BY, Loye AM, Allen KD. Spatiotemporal gait compensations following medial collateral ligament and medial meniscus injury in the rat: correlating gait patterns to joint damage. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan KM, Yeater TD, Allen KD. Age alters gait compensations following meniscal injury in male rats. J Orthop Res. 2022;40(12):2780–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rai MF, Hashimoto S, Johnson EE, et al. Heritability of articular cartilage regeneration and its association with ear wound healing in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(7):2300–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Närhi T, Siitonen U, Lehto LJ, et al. Minor influence of lifelong voluntary exercise on composition, structure, and incidence of osteoarthritis in tibial articular cartilage of mice compared with major effects caused by growth, maturation, and aging. Connect Tissue Res. 2011;52(5):380–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White Z, Terrill J, White RB, et al. Voluntary resistance wheel exercise from mid-life prevents sarcopenia and increases markers of mitochondrial function and autophagy in muscles of old male and female C57BL/6J mice. Skelet Muscle. 2016;6(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lapveteläinen T, Hyttinen M, Lindblom J, et al. More knee joint osteoarthritis (OA) in mice after inactivation of one allele of type II procollagen gene but less OA after lifelong voluntary wheel running exercise. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(2):152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Call JA, McKeehen JN, Novotny SA, Lowe DA. Progressive resistance voluntary wheel running in the mdx mouse. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42(6):871–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cartmill M, Lemelin P, Schmitt D. Support polygons and symmetrical gaits in mammals. Zool J Linn Soc. 2002;136(3):401–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen KD, Mata BA, Gabr MA, et al. Kinematic and dynamic gait compensations resulting from knee instability in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(2):R78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobs BY, Dunnigan K, Pires-Fernandes M, Allen KD. Unique spatiotemporal and dynamic gait compensations in the rat monoiodoacetate injection and medial meniscus transection models of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(5):750–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakes EH, Allen KD. Quadrupedal rodent gait compensations in a low dose monoiodoacetate model of osteoarthritis. Gait Posture. 2018;63:73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donell S. Subchondral bone remodelling in osteoarthritis. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4(6):221–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lima L V, Abner TSS, Sluka KA. Does exercise increase or decrease pain? Central mechanisms underlying these two phenomena. J Physiol. 2017;595(13):4141–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lesnak JB, Sluka KA. Mechanism of exercise-induced analgesia: what we can learn from physically active animals. Pain Rep. 2020;5(5):E850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen J, Imbert I, Havelin J, et al. Effects of treadmill exercise on advanced osteoarthritis pain in rats. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(7):1407–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoeger Bement MK, Sluka KA. Low-intensity exercise reverses chronic muscle pain in the rat in a naloxone-dependent manner. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(9):1736–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brito RG, Rasmussen LA, Sluka KA. Regular physical activity prevents development of chronic muscle pain through modulation of supraspinal opioid and serotonergic mechanisms. Pain Rep. 2017;2(5):e618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Townsend K, Imbert I, Eaton V, Stevenson GW, King T. Voluntary exercise blocks ongoing pain and diminishes bone remodeling while sparing protective mechanical pain in a rat model of advanced osteoarthritis pain. Pain. 2022;163(3):E476–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Contarteze RVL, Manchado FDB, Gobatto CA, De Mello MAR. Stress biomarkers in rats submitted to swimming and treadmill running exercises. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2008;151(3):415–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yesilyurt O, Seyrek M, Tasdemir S, et al. The critical role of spinal 5-HT7 receptors in opioid and non-opioid type stress-induced analgesia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;762:402–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hahn AK, Batushansky A, Rawle RA, Prado Lopes EB, June RK, Griffin TM. Effects of long-term exercise and a high-fat diet on synovial fluid metabolomics and joint structural phenotypes in mice: an integrated network analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021;29(11):1549–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Poel C, Levinger P, Tonkin BA, Levinger I, Walsh NC. Impaired muscle function in a mouse surgical model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(6):1047–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Assis L, Almeida T, Milares LP, et al. Musculoskeletal atrophy in an experimental model of knee osteoarthritis: the effects of exercise training and low-level laser therapy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;94(8):609–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griffin TM, Batushansky A, Hudson J, Lopes EBP. Correlation network analysis shows divergent effects of a long-term, high-fat diet and exercise on early stage osteoarthritis phenotypes in mice. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9(2):119–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Finan PH, Buenaver LF, Bounds SC, et al. Discordance between pain and radiographic severity in knee osteoarthritis: findings from quantitative sensory testing of central sensitization. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(2):363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 - Experimental design to evaluate physical activity levels and OA progression in C57Bl/6 mice following meniscal injury

Figure S2 - Method of joint segmentation to create binarized masks for quantitative grading of histological images

Figure S3 - Data visualization of open field activity

Figure S4 - OARSI scores following meniscal injury in active and sedentary mice, showing DMM-operated knees have greater tibial (A) and femoral (B) cartilage loss compared to all other knees

Table S1 - Statistical analysis with main effects and interactions for voluntary wheel running data

Table S2 - Summary of number of total gait trials included in the analysis for each group at each timepoint

Table S3 - Statistical analysis for quantitative histological data following meniscal injury in physically active and sedentary male and female C57BL/6 mice