Abstract

The study of the interplay between social factors, environmental hazards and health has garnered much attention in recent years. The term “exposome” was coined to describe the total impact of environmental exposures on an individual’s health and wellbeing, serving as a complementary concept to the genome. Studies have shown a strong correlation between the exposome and cardiovascular health, with various components of the exposome having been implicated in the development and progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD). These components include the natural and built environment, air pollution, diet, physical activity, and psychosocial stress, among others. This review provides an overview of the relationship between the exposome and cardiovascular health, highlighting the epidemiological and mechanistic evidence of environmental exposures on CVD. The interplay between various environmental components is discussed, and potential avenues for mitigation are identified.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Environment, Exposome, Pollution

Introduction

The long-established correlation between the environment and human health has garnered increasing attention in recent years. To complement the “genome”1 in the “nature vs nurture” approach to disease, the concept of the ‘exposome’ has emerged. The exposome refers to the comprehensive lifetime exposures of individuals and populations to their surrounding environment. It represents the methodological and technological pursuit of characterizing environmental exposures across the lifespan, with the aim of gaining unique mechanistic insights into the effects of these exposures on human health.2

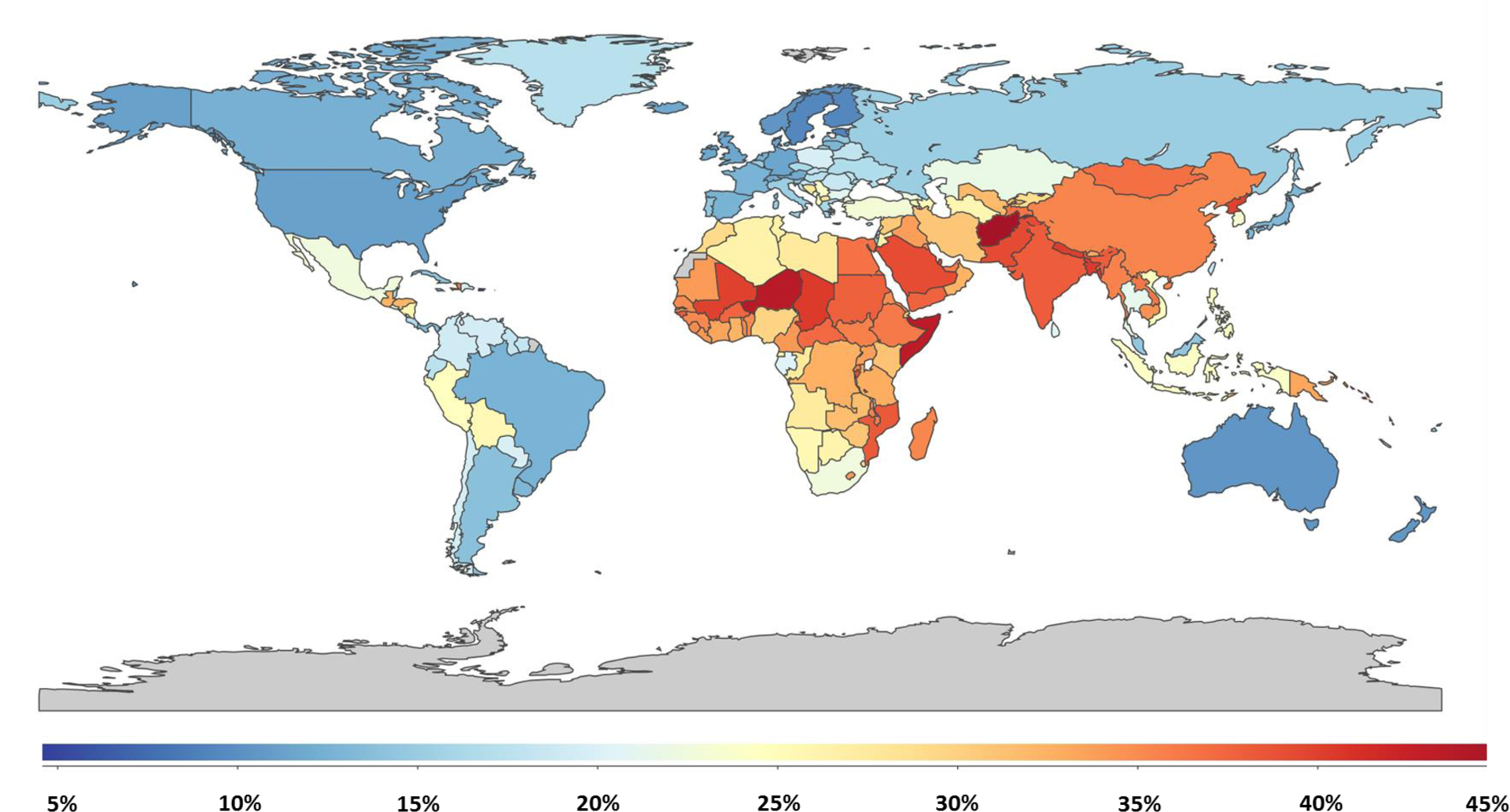

Variations in components of the exposome and cardiovascular health are closely interlinked as evidences by robust literature associating components of the exposome with cardiovascular health outcomes.3 Such components include surrounding natural and built environmental factors among others. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates that adverse environmental exposures are responsible for a significant portion of the global CVD burden, accounting for over 40% of the CVD burden in some countries in South Asia and Africa (Figure 1). Recognizing various components of the exposome allows for the identification of distinct downstream pathways and gaining unique mechanistic insights for environmental exposures. This understanding helps comprehend how exposures to the environment in daily life, work, and commute may influence the development and progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD).3 Moreover, understanding the interaction between the environment and cardiovascular health has the potential to pave the way for large-scale preventative interventions.

Figure 1:

Global Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Attributable to Environmental/Occupational Exposures, Illuminating the Environmental Exposome Impact - Based on the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Estimates and The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

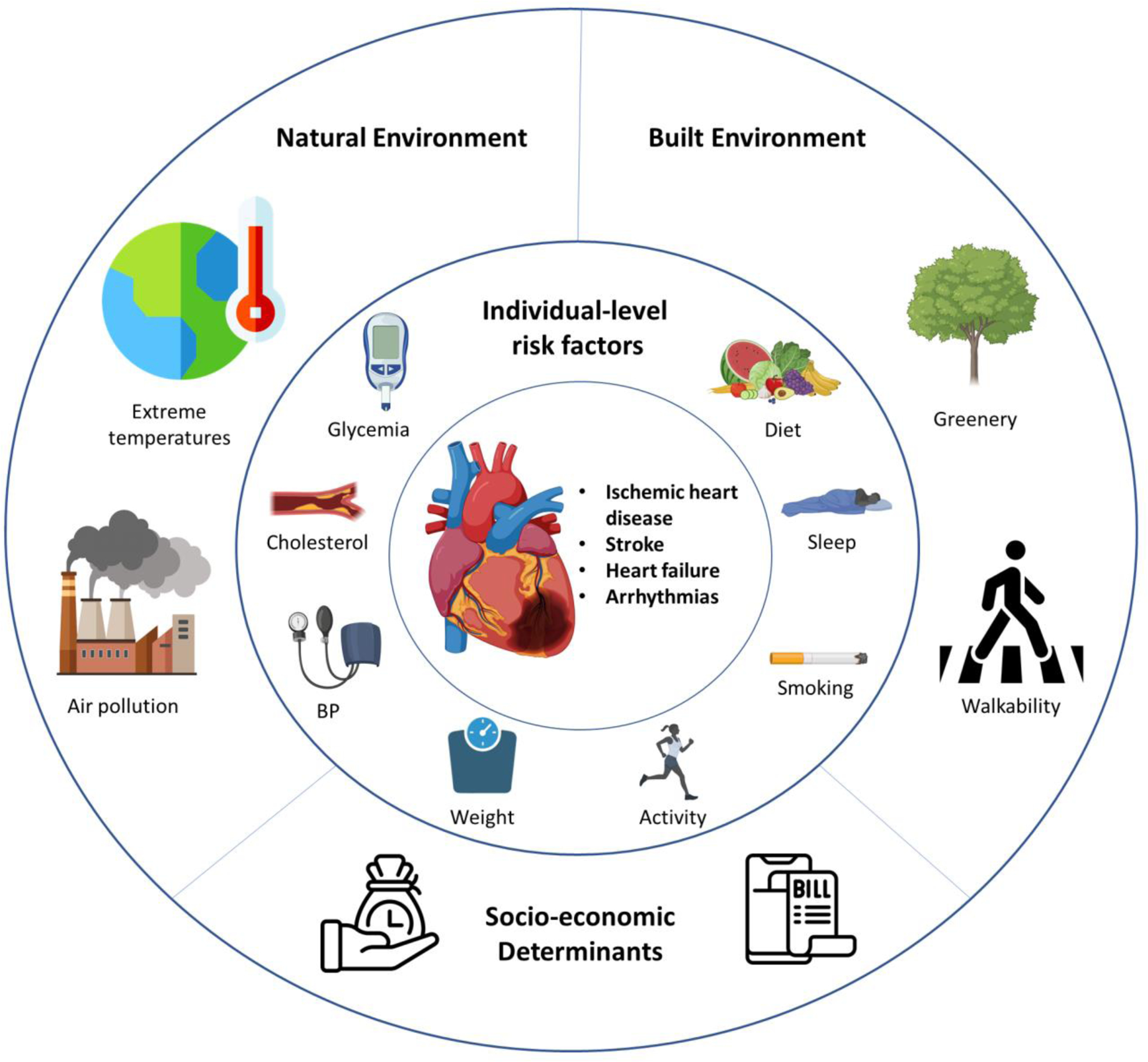

In this review, we aim to provide an overview of the significant components of the exposome in relation to cardiovascular health (Figure 2). To provide an understanding of the topic, we will first cover some technologies used to measure environmental exposures across an individual’s lifetime. We then present both epidemiological and mechanistic perspectives on the impact of environmental exposures on CVD, highlighting the complex interplay between environmental factors and the pathways by which they affect cardiovascular health. Additionally, we address current gaps in the literature and outline potential avenues for future research.

Figure 2:

Features of the “exposome” associated with cardiovascular health. Created with BioRender.com.

The “Pollute” Concept:

The Lancet Commission on pollution and health estimated that pollution was responsible for 9 million premature deaths in 2015.4 A subsequent analysis using the latest data from the 2019 GBD study reaffirms that pollution remains a significant contributor, with an annual death toll of approximately 9 million, representing one in six deaths worldwide.5 Notably, a substantial proportion of non-communicable disease deaths (19.6%) and cardiovascular disease deaths (27.5%) can be attributed to the detrimental effects of an unhealthy environment and pollution.5

Understanding the concept of “pollute” is crucial in the context of the exposome, which aims to capture all environmental exposures individuals encounter throughout their lives. Environmental pollutants, originating from various sources such as air, water, food, and consumer products, are ubiquitous.6 These pollutants can have cumulative and synergistic effects on health, underscoring the vital role of exposome assessment in understanding the underlying mechanisms of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease.7 By incorporating the “pollute” concept within the exposome framework, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of exposure to environmental pollutants, enabling a thorough analysis of the complex interplay between environmental factors and cardiovascular health outcomes.

Quantifying and Characterizing the Exposome:

The comprehensive characterization of the exposome and its impact on health, particularly cardiovascular health, necessitates a multidisciplinary approach. Various techniques have been employed to capture the multifaceted nature of environmental exposures, taking advantage of advancing technologies.

Remote sensing methods, for instance, have proven valuable in quantifying exposures to air pollution, greenery, and temperature. An enhanced approach to estimating ground-level PM2.5 utilizes data from multiple sources, including satellite imagery and chemical transport models. These estimates are further refined through calibration with ground-based observations, providing a more precise depiction of PM2.5 levels.8 Additionally, biomarker-based signatures offer an avenue for measuring exposure-related effects, such as the distinct metabolomic signature associated with PM2.5, which can be analyzed in blood samples.9

The evaluation of greenness, an important aspect of the exposome, is accomplished through the assessment of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI).10 Operating on a scale from −1 to 1, the NDVI provides an estimate of the presence of green vegetation, where values above 0 signify increasing levels of greenness, and values below 0 indicate water. Similarly, other factors related to the built environment have been characterized and quantified. For example, the walkability of a neighborhood, a factor linked to heart disease, can be inferred by considering the density of street intersections and transit stops.11 Emerging approaches utilizing computer vision techniques enable the quantification of additional built environmental factors that may impact health outcomes.12

Psychosocial stressors, recognized as crucial components of the exposome, have been assessed through aggregated metrics like the social vulnerability index. This index incorporates census data encompassing socioeconomic and demographic information providing a comprehensive evaluation of vulnerability within communities.13

Despite significant research efforts examining individual exposures and their association with health outcomes, there remains a need for studies that integrate and quantify multiple exposures simultaneously. The advancement of computational approaches offers promise in enhancing our understanding of the complex interplay between the social, natural, and built environment. For instance, the analysis of online social media interactions can quantify social capital, a factor with potential implications for health metrics.14 Additionally, GPS-enabled smartphones can provide personalized exposure assessments based on geospatial data models.

However, the analysis of these vast datasets generated by such approaches presents challenges for standard statistical methods. Fortunately, the evolving field of exposomics is embracing novel machine learning techniques that facilitate the exploration of how different factors interact to shape geography-specific socio-environmental phenotypes, ultimately influencing health outcomes.

A recent study exemplifies the potential of machine learning in identifying community-level phenotypes associated with premature cardiovascular mortality.15 By analyzing a diverse range of socioeconomic, behavioral, and environmental risk factors, this approach disentangles the roots of geographical disparities in disease burden. These findings have profound implications for public health interventions, emphasizing the importance of personalized strategies tailored to the unique needs of high-risk communities. Similarly, there remains ample opportunity for further studies targeting multiple exposures, expanding our understanding of the exposome and its impact on health.

Air pollution and CVD

PM2.5 and CVD:

Epidemiology:

The GBD study highlights air pollution as the top environmental contributor to health in general, and cardiovascular health in particular.5 In fact, air pollution contributes to 6–9 million deaths yearly- predominantly related to cardiovascular disease.7 A substantial body of evidence implicated particulates suspended in air, smaller than 2.5 μm, in diameter (Particulate matter <2.5, or PM2.5), as a substantial contributor to air pollution’s adverse health outcomes. There is a strong association between PM2.5 and cardiovascular outcomes and risk factors. This association is seen across a wide range of exposures with no clear threshold minimum where the association attenuates.16 In fact, the dose-response between PM2.5 and PM2.5-attributable mortality is nearly linear across a wide range of exposures and regions.16–18

Chronic exposures have shown stronger associations with adverse outcomes than their short-term exposure counterparts, elucidating cumulative disease burden with time.19 PM2.5 impacts are pronounced in regions with elevated exposures, such as the Eastern Mediterranean and Southeast Asia.20 However, this association is consistent even in regions with lower exposure levels in Canada and the US; In fact, 1 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentration in Canada was associated with a 25% increased 10-year hazard ratio for cardiovascular mortality.21 A large cohort study from the United States elucidated similar trends with a 8.7% increased MACE risk for every 1 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentrations.22

While long-term exposures are associated with the largest burden, short-term PM2.5 exposures are associated with considerable CVD morbidity and mortality. In fact, a recent meta-analysis of 28 studies found a significant association between short-term PM2.5 exposures (defined as 24-hr average concentration) and cardiovascular mortality.23 Also, a meta-analysis of 34 studies depicted a 2.5% increased risk of myocardial infarction with each 10 μg/m3 increment in short-term exposure to PM2.5.24

An important driver of PM2.5 attributable cardiovascular mortality is the PM2.5 attributable cerebrovascular impact. A meta-analysis of 68 studies encompassing more than 23 million people showed significant association between short term exposure to PM2.5 with incidence and death from stroke.25 Similarly, a meta-analysis of 42 studies showed than a 10 μg/m3 increase in long-term exposure to PM2.5 was associated with a 13% increase in incident stroke and 24% increase in cerebrovascular mortality.26

PM2.5 is also associated with multiple cardio-metabolic risk factors. A recent meta-analysis found that 10 μg/m3 elevations in long-term PM2.5 exposures are associated with 0.63- and 0.31-mm Hg increments in systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels.27 Additionally, PM2.5 has been consistently associated with diabetes and metabolic syndrome through mediation of insulin resistance and oxidative stress.28 Studies have also shown that chronic exposures can lead to dyslipidemia with pronounced effects on LDL cholesterol levels, increasing cardiovascular risk.29, 30

Mechanistic insights:

Mechanistic studies have unraveled how air pollution leads to cardiovascular disease, with significant improvement of the mechanisms in our understanding in the past 2–3 decades. The current working conceptual model linking PM2.5 exposure with CVD includes primary “initiating” pathways, secondary “transmission” pathways, and finally end-organ effector mechanisms.31

Given that air pollution is inhaled, initiating pathways originate in the lungs. The major primary initiating pathways include pollutant-mediated oxidative stress, receptor/ion channel activation, and pulmonary inflammation31–34. These pathways converge into transmission-mediation pathways which include signal transduction through biological intermediates (eg. cytokines, immune cells, vasoconstrictors), autonomic imbalance, and the translocation of pollutant constituents to the circulation and or transmission through neurological pathways.31

Ultimately, these pathways lead to multiple sequelae. The main end-organ effector mechanisms include tissue and multi-organ inflammation, thrombosis, plaque instability, endothelial damage, vascular dysfunction, and epigenomic changes.31 PM2.5 can either initiate these mechanisms or can exacerbate underlying These sequelae play a crucial role in eliciting cardiovascular events, particularly with cumulative long-lasting exposure.

Ozone and CVD:

Ozone poses an independent risk with both short-term and long-term exposure. Short-term increases in ozone have shown a threshold effect (as opposed to PM2.5 which does not) contributing to elevated daily mortality rates. Short-term minor fluctuations in ozone concentrations are associated with a relative risk of 1.005 (95% CI: 1.0041 to 1.0061) in daily mortality rates.35 Long-term exposure to ozone has also been linked to increased all-cause mortality, with a 10 ppb increase in ozone concentration associated with a 1.1% relative increase (95% CI: 1.0% to 1.2%).36 High ozone concentrations, particularly in conjunction with other pollutants, can amplify its effects, affecting the chemical half-life of substances such as antioxidants and surfactants.35 While the direct impact of ozone on human health is still being studied, evidence suggests it can impair endothelial function and potentially disrupt the blood-brain barrier or influence neuronal function in humans and mice.37

Land and Water Pollution in the Exposome:

Toxic Metal Pollutants:

Metals such as lead, mercury, arsenic, and cadmium, which are ubiquitous in land and water environment have been widely associated with numerous health risks spanning neuropsychiatric, oncological, and cardiometabolic disease. Recent evidence point to toxic metal exposures as crucial antecedents to cardiovascular disease.7

Lead:

Lead is estimated to be associated with almost 1 million deaths globally, with a vast proportion due to cardiovascular disease.5 The use of lead has decreased in high income countries, however, has remained particularly high in low and middle income countries due high demand for lead based batteries and continued use of lead paint.

Lead is a known risk factor for blood pressure which is reversible upon chelation of lead. A population based study in the US found that even lower levels of blood lead (less than 3 μg per deciliter) may be associated with cardiovascular mortality.38

Mercury:

Coal combustion and artisanal gold mining are primary sources of mercury pollution. During combustion, mercury vaporizes and enters the atmosphere, eventually precipitating into aquatic environments where it transforms into methylmercury.7 Methylmercury exposure, mainly through consumption of contaminated fish39, is associated with a dose-dependent increase in the risks of death from cardiovascular disease and nonfatal myocardial infarction.40 Methylmercury affects cardiovascular health through mechanisms that are yet to be fully understood.

Arsenic:

The primary cause of human exposure to arsenic is the contamination of drinking water by naturally occurring arsenic, impacting approximately 100 million individuals globally.41 Areas with concentrated exposure include Bangladesh, Thailand, Taiwan, and northern Chile. Within the United States, regions such as northern New England and the Southwest have been identified as having elevated levels of arsenic in groundwater.7

Proposed mechanisms through which Arsenic impacts cardiovascular health include oxidative damage and inflammatory pathways accelerating atherogenesis.42

Cadmium:

The primary sources of cadmium exposure include tobacco smoke, workplace exposure, and the consumption of certain foods such as green, leafy vegetables (such as spinach and lettuce), cereals, and tubers that are grown in soils contaminated with cadmium.7 Recent studies demonstrate that there is a proportional increase in the risk of various cardiovascular disease outcomes, excluding stroke, with higher exposure levels of cadmium, even at extremely low levels of exposure (urinary cadmium level below 0.5 μg per gram of creatinine).43

Cadmium may contribute to atherosclerosis through multiple mechanisms, such as increased reactive oxygen species formation, interference with anti-oxidative stress responses, elevated blood pressure, kidney damage, cadmium-related estrogenic activity, and epigenetic changes, although their relevance to cadmium-induced atherogenesis remains uncertain.43

Chemical pollution:

The exponential increase in the production of manufactured chemicals over the past 50 years has led to widespread environmental dissemination and significant human exposure. Among these chemicals, two important classes are plastic-associated chemicals, including bisphenol A (BPA), and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). BPAs are commonly found in personal care products, food preservatives, pharmaceuticals, and paper products, while PFAS are chemical pollutants used in water repellants and fire-fighting foams. The epidemiological association between BPA exposure and cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as obesity and diabetes, highlights the harmful impact of these chemical pollutants on cardiovascular health. A meta-analysis showed that BPA exposure is associated with a 1.45-fold increased risk of type 2 diabetes (95% CI, 1.13 to 1.87).44 Similarly, PFAS have strong links to type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Extreme temperatures:

Epidemiology:

Both increases and decreases in ambient temperatures beyond the optimal temperature thresholds contribute to global cardiovascular disease burden. This led to an introduction of non-optimal temperature as an important risk factor in the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study.5 A recent global analysis elucidated that more than 1 million deaths every year are mediated by non-optimal temperatures.45 The greatest non-optimal temperature attributable mortality burden is associated with low rather than high ambient temperatures.45, 46

A meta-analysis of 18 studies found that a 1-degree Celsius increase or decrease of ambient temperatures above or below the optimal temperature threshold was associated with 3.44% and 1.66% increase in cardiovascular mortality, respectively.47 The higher burden associated with low temperatures, despite the fact that higher temperatures pose a greater increased risk per 1 degree Celsius, is likely a complex issue influenced by multiple factors. However, one contributing factor is the higher frequency of days with temperatures below the theoretical minimum-risk exposure level or the temperature associated with the lowest mortality rates, as compared to days above it.45

A recent study examined the impact of extreme heat days on cardiovascular mortality rates in 3,108 counties across the United States from 2008 to 2017.48 The findings revealed a significant association between extreme heat and excess cardiovascular mortality. Interestingly, even after incorporating air quality measures into the analysis, the estimate of this association remained largely unchanged, highlighting the independent association between temperature and cardiovascular mortality. Moreover, a meta-analysis found that heatwaves demonstrated a 21% increase in risk for cardiovascular death.49

Cold spells or a significant temperature drop- usually for more than 2 consecutive days have been also associated with an overall increase in cardiovascular events. A meta-analysis of 8 studies depicted an 11% increase in cardiovascular mortality associated with cold spells.50

Non-optimal temperatures are also associated with adverse cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes including but not limited to ischemic heart disease, heart failure admissions, arrhythmias, and strokes.46 Most recently, a multinational study found that both hot days (above 97.5th percentile) and cold days (below 2.5th percentile) were associated with excess cardiovascular mortality, especially from heart failure.51 These estimates were robust to confounders including air pollutants and humidity.

It is crucial to acknowledge the concurrent changes in other environmental exposures that often accompany extreme temperatures, potentially leading to synergistic effects on cardiovascular health. Notably, air pollution stands out as a significant factor that has been extensively studied in relation to temperature-related health impacts. A recent meta-analysis of 22 studies highlighted that particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of less than 10 μm (PM10) and ozone act as effect modifiers, influencing the association between temperature and all-cause mortality. The analysis revealed that the excess risk of temperature on all-cause mortality nearly doubles in the presence of high PM10 levels compared to low levels.52 These findings emphasize the importance of considering multiple exposures when quantifying the health impacts, underscoring the critical role played by the combined effect of extreme temperatures and air pollution in understanding the overall risks to cardiovascular health.

Mechanistic insights:

There are some proposed mechanisms through which non-optimal temperature is associated with cardiovascular events. These mechanisms may be more pronounced in vulnerable populations lacking means for indoor temperature control. The possible mechanisms associated with a rising core body temperature include volume depletion due to perspiration, sympathetic activation, and associated tachycardia.46 Moreover, volume depletion can lead to hemo-concentration which is in turn associated with increased risk for thrombosis and myocardial insults.53 Rising body temperature can also lead to sympathetic activation and associated tachycardia with an average increase of 8.5 bpm for every 1 °C increment in core body temperature.54 In more vulnerable patients, especially those with established cardiovascular disease, sympathetic activation may lead to demand ischemia while volume depletion may lead to shock.55 Other consequences associated with high temperature exposures include cellular endothelial dysfunction, protein denaturation, electrolyte imbalances and associated arrhythmias, and systemic inflammatory responses.56–58

On the other hand, a decreasing core body temperature is associated with increased blood viscosity and hypercoagulability due to fluid shift into third spacing and clotting factor abnormalities.59 Cold temperatures also lead to sympathetic activation, vasoconstriction, and increased muscle tone to generate and conserve body heat which premeditate myocardial demand ischemia.60, 61 Low temperatures can precipitate plaque instability and rupture due to cholesterol crystallization, especially in vulnerable patients.62 Finally, colder temperatures can cause bradycardia due to decreased conduction increasing risk for arrhythmias and asystole.58

Non-optimal temperature-associated cardiovascular outcomes are not exclusively caused by disturbances in body temperature (i.e., hypo- and hyperthermia). Extreme temperatures can, independent of hypo/hyperthermia, induce inflammation, hypercoagulability, and conduction abnormalities.46 For example, heat exposure can elicit the release of endotoxins from the intestines and interleukins IL-1 and IL-6 from the muscles into the circulation, triggering a pro-inflammatory response.46 This systemic inflammation can cause endothelial dysfunction and plaque instability, making individuals more vulnerable to cardiovascular disease and events. Moreover, extreme temperatures often co-occur with other environmental risks (e.g. air pollution) that may be independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes.63 On the other hand, cold temperatures may lead to decreased physical activities, such as walking, which contribute to cardiovascular risk.

Built environment:

The built environment is the human-designed space in which individuals reside and conduct their daily activities.64 The built environment is increasingly recognized as an important driver for health, particularly cardio-metabolic health.64 There are multiple built environmental constituents impacting cardiovascular health including walkability, access to greenspace, and community design.

Walkability:

Walkability may improve cardiovascular health by encouraging leisure time and non- leisure time activities. Whether walking to a neighborhood market or to the park, a walkable neighborhood encourages people to remain physically active.11 In a recent national level study from the US investigating the association between walkability and cardio-metabolic risk, living in a more walkable neighborhood was inversely and favorably associated with neighborhood prevalence of coronary artery disease and associated risk factors including hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, and diabetes.11 Similarly, a study from Ontario, Canada, found that walkability was significantly and inversely associated with 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in more than 44,000 individuals.65 Another study from Canada found that walkability and park access are associated with significantly lower odds of self-reported hypertension.66

Greenspace:

Another important factor in the built environment is access and availability of greenspace. Greenspace is any space covered with trees, grass, shrubs or any vegetation.67 These spaces can protect against cardiovascular disease by means of fostering physical activity, social engagement, elevating stress, and protection against exposure to noise and air pollution.67 Recent research using the TwinsUK cohort discovered differences in gut microbiome composition related to greenspace exposure, suggesting that microbiota could act as a mediator between greenspace and health.68 Additionally, among numerous components of the exposome, green space exposure has been shown to be most significantly associated with higher birth weight. This is supported by a study of nearly 32,000 women, which found that access to green space during pregnancy was associated with increased birth weight and was protective against term low birth weight.

Furthermore, several studies have investigated the connection between greenspace exposure and cardiovascular disease, as well as its related risk factors.69 A meta-analysis of 23 studies found that increased residential greenery (based on satellite derived indices) was associated with significantly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure.70 A study from Finland showed in 36 women that even short visits to urban green environments are associated with cardiovascular benefits including lower blood pressures and heart rates, and higher indices of heart rate variability.71 In a Canadian prospective cohort study of more than 1.2 million individuals followed from 2001 to 2011 found that increased amount of residential greenness was associated with a significant decrease in cardiovascular mortality (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.89–0.93)10. Indeed, increasing access to green space and implementing strategic urban greening can provide multiple benefits, including enhanced microclimates, improved physical and mental health, and reduced all-cause mortality.6

Food environment:

Food security:

Food insecurity or limited access to food in general but healthy food in particular has been a big driver of cardiovascular disease.72 In fact, a recent United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) report estimates that more than 10% of American adults live in households with food insecurity.73 Food insecurity has been associated with multiple cardiometabolic outcomes including metabolic syndrome74 and cardiovascular disease75. A recent analysis of 27,188 US adults (≥40 years of age) in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1999 to 2014 found that adults with very low food security are more likely to die from cardiovascular causes (HR 1.53 [95% CI, 1.04–2.26]) even after multivariable adjustments.75 Similarly, another study from the US showed that 13% of adults living with Diabetes were food insecure, and food insecurity was associated with ASCVD independent of socioeconomic and traditional risk factors.76

The mechanisms through which food insecurity permeates adverse cardiovascular outcomes are unclear but there are some speculated mechanisms. First, individuals who are food insecure are more likely to replace healthy diets with less expensive caloric dense foods precipitating insulin resistance and adipose tissue deposition.72 Moreover, less food security could mean less diverse diets and poorer food quality, leading to less consumption of fruits, vegetables, and important nutrients, increasing cardiometabolic risk.77 Finally, as seen in Quebec, Canada, food insecurity can be very stressful emotionally and physiologically which can impact cardiovascular health and outcomes.78

Ultra-processed foods:

An important part of the food environment is the consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPF). UPF are industrial formulations, usually low cost and energy dense, usually made from food extracts and or synthesized in laboratories from various sources.79 Over the years, there has been an exponential consumption of UPFs in both middle-income and high-income countries.80 Recent epidemiological studies have highlighted a strong link between the consumption of UPF and cardiovascular health. Research found an inverse graded association between percentage of caloric intake from UPF and the American Heart Association’s “Life’s Simple 7” cardiovascular health score in adults and adolescents throughout the United Staes.81

Several mechanisms have been proposed linking the consumption of UPF with cardiovascular disease. First, UPF are usually high in sugar, sodium, and trans/saturated fats.79 High sugar intake is associated with multiple cardiometabolic risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, and ultimately metabolic syndrome.82 Meanwhile, consumption of high sodium foods is associated with higher blood pressure83. While consumption of foods high in trans and saturated fats is associated with dysplidemia and increased CVD risk.84 Moreover, UPF are enriched with high-intensity flavoring making these foods tastier, so people might eat more of these foods despite physiological satiation.85 This leads to overeating and intake of hyperglycemic loads precipitating cardiometabolic syndrome.

Social determinants of health and the environment:

Social environment and social determinants of health (SDOH) are critical part of the exposome. In fact, these determinants play a huge role in shaping and developing surrounding environment, as well as dictating the vulnerability to environmental exposures.

Crucial cardiovascular risk factors linked with SDOH include access to medical care, community stressors, social cohesion, and housing.86 Many of these factors may modify the interactions between environmental stressors and cardiometabolic risk.87, 88

Interaction between social vulnerability and environmental impact on CV disease

Social vulnerability refers to a conglomerate of socio-economic factors evaluating the degree to which communities are resilient to disease and disasters. These determinants transcending a wide array of domains such as income, education, healthcare access, and other social factors which can explain at times more than 50% of the geographic variation in cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality.89

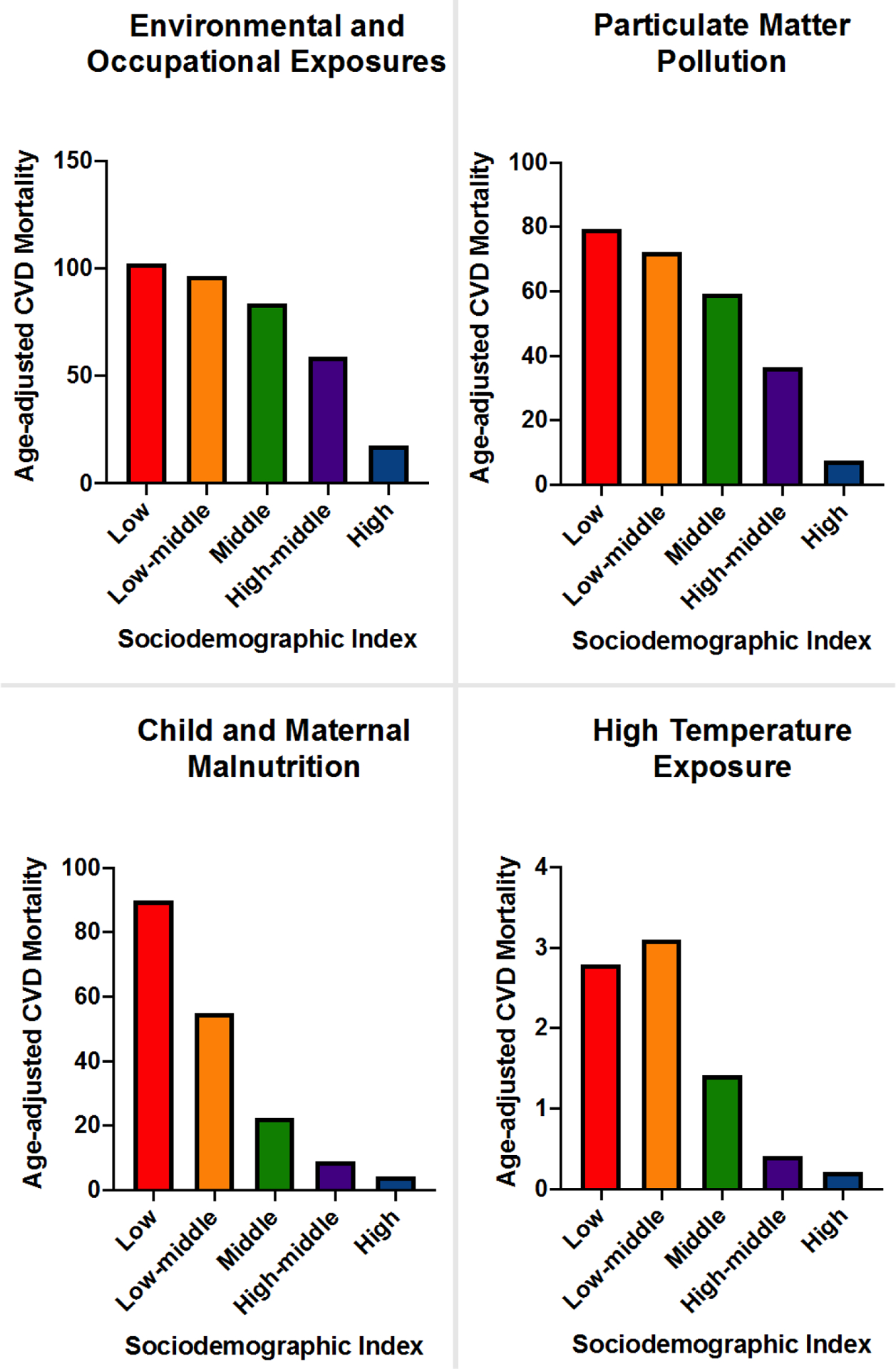

Not only are these factors directly implicated in CV health and risk factors, but they can also modify the associations between environmental exposures and cardiometabolic risk factors. For instance, there is a gradual decrease in the environmental-related cardiovascular mortality rate as the sociodemographic index (which reflects a nation’s level of development) improves for various socio-environmental factors (Figure 3). In US population level studies, social deprivation was found to modify and accentuate the association between ambient air pollution and cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease mortality. In fact, the association between PM2.5 and cardiometabolic mortality was highest in the most socially deprived counties.87, 88

Figure 3:

Impact of country sociodemographic index on exposome attributable age-adjusted cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality - Based on the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Estimates and The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

Environmental Justice

Environmental injustice refers to the constellation of exposures which disproportionately impact disadvantaged individuals and communities. Whether intentional or not, these adverse exposures which are rooted in environmental policies and decisions have positioned “marginalized” groups at increased risk.90

Pollution disproportionately afflicts the vulnerable and poor. Globally, the biggest polluters (highincome countries) are not the ones experiencing the health impacts of adverse environmental exposures. In fact, 92% of pollution-attributable deaths occur in low-income and middle-income countries.4 Further, at every income level, diseases caused by pollution preferentially impacts minorities and marginalized communities.4

Canada has its share of environmental racism which that is still impacting the health of racialized and Indigenous communities. Examples include dumping 10,000 kg of mercury into the Wabigoon River in Grassy Narrows First Nation in Ontario, dumping toxic wastes in the Africville community in Halifax, NS, and others.91 In the United States, historical neighborhood “redlining”, a discriminatory practice, largely based on race, lead to decades of environmental racism afflicting millions of people across the nation. Individuals residing in “redlined” areas had higher exposures to air pollutants, noise, light pollution, and various hazardous emissions over the past decades.92 These has hazardous exposures have in turn contributed to a myriad of cardiometabolic risk factors and outcomes including coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes.93

Racial and socio-economic disparities in air pollution-attributable mortality are well documented.94 Despite absolute disparities in exposures to PM2.5 declining between 1981 and 2016, relative disparities have persisted.95 A recent report depicts that on average Black, Asian, and Hispanic or Latinx populations have higher exposures to PM2.5 than their white counterparts.96 Similarly, a study comparing weighted exposures of 11 environmental indices with cardiovascular impacts, found that white populations had consistently more favorable exposure profiles than non-white populations.97 These findings suggest that more targeted approaches may be necessary to provide different racial, ethnic, and socio-economic profiles similar protections from adverse environmental exposures.

Age and the Exposome:

Age and timing of exposure are critical factors that can influence an individual’s susceptibility to environmental pollutants and their associated health effects.98 Early-life exposures are particularly important, as prenatal and postnatal development results in heightened sensitivity to environmental factors. For example, prenatal exposure to environmental pollutants has been linked to adverse birth outcomes, such as low birth weight and preterm birth99, while early-life exposure to air pollution has been associated with persistent cardiac dysfunction at adulthood.100

On the other hand, elderly individuals may experience physiological changes that can increase their vulnerability to environmental exposures. Reduced renal function and slower metabolism in older adults can lead to the accumulation of environmental toxins and slower elimination rates, thereby enhancing their susceptibility to environmental exposures. Additionally, older adults may have pre-existing comorbidities, making them particularly susceptible to the harmful effects of pollutants.98 For example, our study shows that older men who have undergone percutaneous coronary interventions are particularly vulnerable to the effects of PM2.5 in terms of life year lost and MACE events.22

Climate Change and the exposome:

Climate change refers to the long-term shift in global weather patterns and climatic conditions. These changes are primarily driven by human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels which release greenhouse gases which lead to heat entrapment in the lower atmosphere, causing global warming.46 Climate change is closely related to a wide array of environmental exposures, which in turn have tremendous impact on cardiovascular health.46

One impact of climate change is the substantial swinging of extreme ambient temperatures.46 Abrupt temperature changes are well associated with cardiovascular events.55 Heatwaves and cold spells are not new phenomena, but their frequencies and intensities are expected to increase with climate change. Moreover, climate change and air pollution not only share common roots, such as anthropogenic causes, but also share an intimate bidirectional relationship. Climate change and global warming will lead to more emission of air pollutants such as particulate matter and ground-level ozone. Moreover, global warming is expected to increase the risk of wildfires, which inevitably lead to the release of PM and carbon monoxide.101

A 2018 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) found that the global average temperature has increased by about 1 degree Celsius since the pre-industrial era and is likely to increase by another 1.5 degrees by 2030 if emissions continue at their current rate. The report also concluded that limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius could significantly reduce the negative impacts of climate change on the environment and society.102

Mitigating susceptibility and vulnerability related cardiovascular disease burden

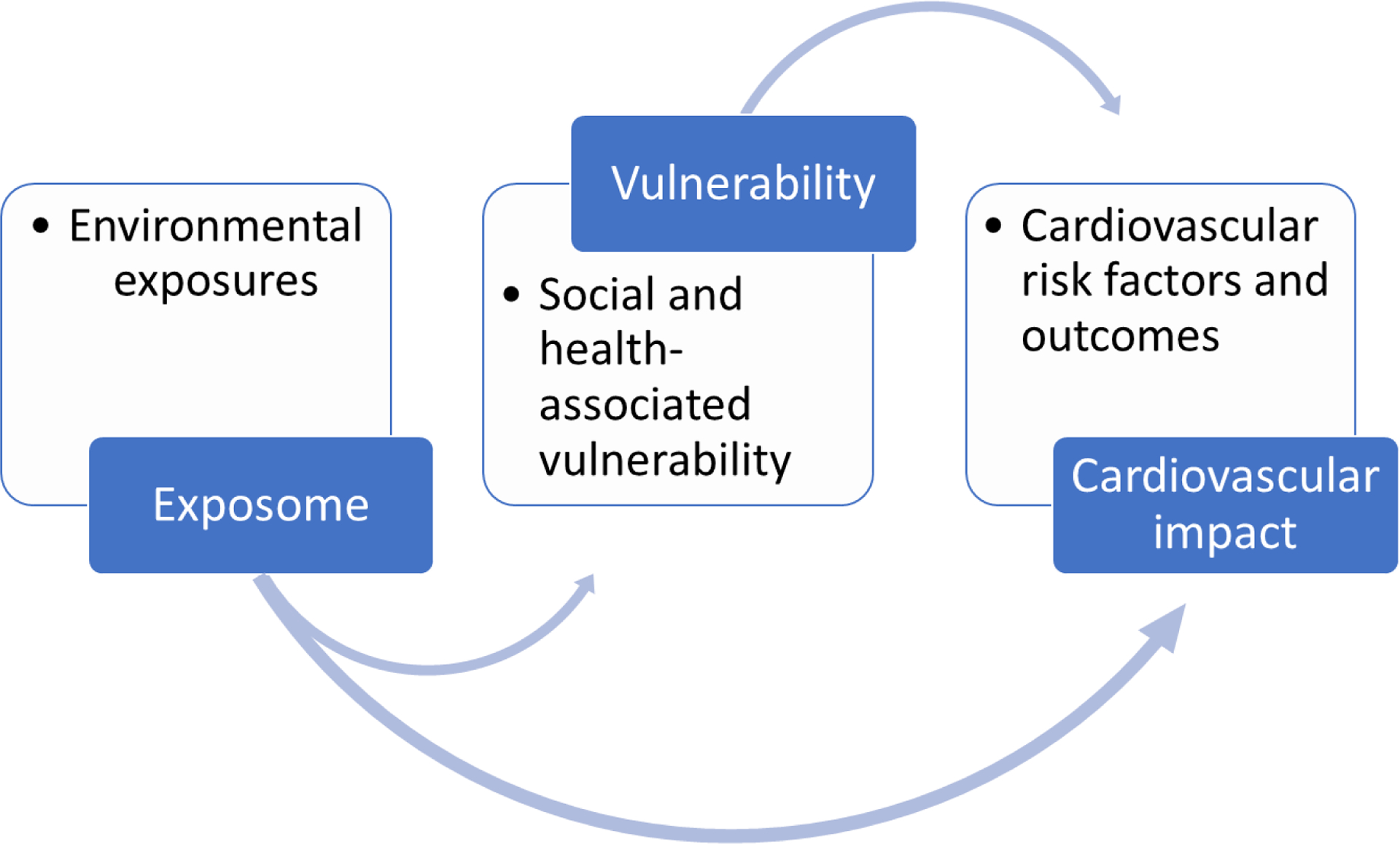

The exposome contributes to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease both directly and indirectly, which is exacerbated by social and health vulnerabilities and susceptibilities (Figure 4). To effectively address this issue, a collaborative approach involving interdisciplinary teamwork between public health professionals, lawmakers, and national leaders is crucial to mitigate the effects of environmental exposures.

Figure 4:

Impact of “exposome” on cardiovascular health is mediated by social and health vulnerability

Societal and governmental reforms:

Exposomics presents a unique challenge because although presenting as individual-level health problems, mainly as chronic non-communicable diseases, the roots of these problems are larger systemic processes. Thus, a multi-level and multi-stakeholder approach would yield better protection than individual-level strategies. Societal and governmental actions are imperative to decrease adverse exposure levels. One example of that is the clean air act in the United States which led to massive improvements of air quality across the nation. In fact, the substantial improvement in air quality across the US was independently associated with increased life expectancy.103 Moreover, every dollar spent in the USA from 1970s had an estimated return of 30$ in benefits (4–80$ range), which shows that controlling air pollution exposure not only alleviates adverse health outcomes but may also have economic benefit.104 Long-term exposure to polluted air in China adversely affects cognitive abilities, particularly among less educated men, with significant improvements observed by reducing particulate matter concentrations, underscoring the health and economic consequences.105

The Paris Agreement, involving 190 countries, exemplifies the effectiveness of a multinational approach in addressing climate change. National mandates and agreements may have significant short-term effects in reducing emissions, which can result in substantial protection against cardiovascular events.106 The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a decrease in global air pollution due to a decrease in both road traffic and air travel. Although it is difficult to use this experience as a long-term public health strategy, it has shown that significant actions can be taken to address the negative health effects of air pollution.

Moreover, built environmental factors should be targeted with urban planning policies. Multi-sectorial approaches are needed bringing together urban planners, healthcare professionals, environmentalists, and policy makers to tackle pervasive problems of the built environment.107 In a study from Barcelona, authors found that proper urban planning including promotion of more active transport and provision of greenspace would result in significant reductions of burden of disease and substantial healthcare savings.108 This is through mitigation of adverse environmental exposures (e.g. noise, air pollution, and extreme temperatures) and promoting healthier, more active lifestyles. An example would be implementing healthier urban planning practices such as providing more diverse land use, better street connectivity, safer neighborhoods, and providing pedestrians with more walkable and cyclable amenities, which could counteract the current epidemic of physical inactivity, a great mediator for cardiovascular disease.109 Providing greener neighborhoods not only encourages active transport but also mitigates the impacts of air pollution, heat, and noise exposures.110

Individual and local mitigation measures:

Governmental and societal reforms are the only assured mechanisms to mitigate and address environmental concerns. However, these reforms come with a multitude of barriers, especially in geo-politically fragile areas where decision making is focused on short-term solutions. Thus, personalized mitigation measures may be imperative in the meantime to protect against cardiovascular impacts of environmental exposures. For example, the use of face masks and home filters have been proven to be effective in ameliorating air pollution effects on blood pressure, with significant decreases in systolic blood pressures.31 An example of local and regional mitigation action plans include the heat-health action plans (HHAPs), a framework developed by the WHO in response to the 2003 summer heatwaves, which include guidance for local authorities in response to excessive heat conditions. This includes timely alert systems, elevation of indoor heat exposures, and emergency medical responses.111

Exposome utility in clinical practice:

The utility of the exposome in clinical practice is vast, offering opportunities to enhance patient care. By comprehensively assessing an individual’s lifetime environmental exposures, clinicians can accurately evaluate disease risk and implement targeted prevention strategies, enabling personalized medicine and improved treatment outcomes. Incorporating environmental exposure data into diagnostic algorithms aids in early detection and diagnosis, facilitating timely interventions. Exposome information empowers clinicians to educate patients about the impact of environmental exposures on health, guiding informed decision-making. Environmental medicine principles expand the scope of clinical practice by addressing exposure-related health concerns in communities and workplaces. Through research, the exposome generates valuable datasets for epidemiological studies, biomarker identification, and exploring gene-environment interactions, furthering evidence-based medicine. Additionally, integrating exposomic factors into risk assessment through place-based calculators allows for accurate cardiovascular risk estimation, considering the influence of the individual’s place of residence. These trends in exposomics present exciting opportunities to understand and mitigate the impact of environmental factors on health outcomes.

Gaps in knowledge and future directions:

Several knowledge gaps exist when linking the exposome to cardiovascular health. One significant gap pertains to the long-term health effects of many environmental exposures, as limited research has been conducted on the combined cardiovascular effects of multiple exposures. The complex interactions between exposome components and cardiovascular health necessitate the use of more robust analytical approaches. Another gap concerns the interplay between the exposome and genomics, with insufficient research on how environmental exposure impacts specific genetic populations. This information is vital for identifying at-risk populations and tailoring interventions.

Moreover, there is limited understanding of the effectiveness of interventions targeting the adverse impacts of environmental exposures on cardiovascular health, particularly in resource-limited regions. While progress has been made in understanding the epidemiology of environmental exposures, further research is needed to assess region- and population-specific interventions and improve our understanding of the exposome’s effects on cardiovascular health.

Funding:

This work was partly funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Award # P50MD017351.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none of the authors have conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Wild CP. Complementing the genome with an “exposome”: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2005;14:1847–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermeulen R, Schymanski EL, Barabási A-L, Miller GW. The exposome and health: Where chemistry meets biology. Science. 2020;367:392–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juarez PD, Hood DB, Song M-A, Ramesh A. Use of an Exposome Approach to Understand the Effects of Exposures From the Natural, Built, and Social Environments on Cardio-Vascular Disease Onset, Progression, and Outcomes. Front Public Health. 2020;8:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landrigan PJ, Fuller R, Acosta NJR, et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. The Lancet. 2018;391:462–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2020;396:1223–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Münzel T, Sørensen M, Lelieveld J, et al. Heart healthy cities: genetics loads the gun but the environment pulls the trigger. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:2422–2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajagopalan S, Landrigan PJ. Pollution and the Heart. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1881–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Donkelaar A, Martin RV, Brauer M, et al. Global Estimates of Fine Particulate Matter using a Combined Geophysical-Statistical Method with Information from Satellites, Models, and Monitors. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:3762–3772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nassan FL, Kelly RS, Kosheleva A, et al. Metabolomic signatures of the long-term exposure to air pollution and temperature. Environ Health. 2021;20:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crouse DL, Pinault L, Balram A, et al. Urban greenness and mortality in Canada’s largest cities: a national cohort study. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1:e289–e297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makhlouf MHE, Motairek I, Chen Z, et al. Neighborhood Walkability and Cardiovascular Risk in the United States. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022:101533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keralis JM, Javanmardi M, Khanna S, et al. Health and the built environment in United States cities: measuring associations using Google Street View-derived indicators of the built environment. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bevan G, Pandey A, Griggs S, et al. Neighborhood-level Social Vulnerability and Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Coronary Heart Disease. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022:101182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chetty R, Jackson MO, Kuchler T, et al. Social capital I: measurement and associations with economic mobility. Nature. 2022;608:108–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong W, Motairek I, Nasir K, et al. Risk factors and geographic disparities in premature cardiovascular mortality in US counties: a machine learning approach. Sci Rep. 2023;13:2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnett R, Chen H, Szyszkowicz M, et al. Global estimates of mortality associated with long-term exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:9592–9597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu F, Xu D, Cheng Y, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the adverse health effects of ambient PM2.5 and PM10 pollution in the Chinese population. Environ Res. 2015;136:196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:2331–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beverland IJ, Cohen GR, Heal MR, et al. A comparison of short-term and long-term air pollution exposure associations with mortality in two cohorts in Scotland. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1280–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motairek I, Ajluni S, Khraishah H, et al. Burden of Cardiovascular Disease Attributable to Particulate Matter Pollution in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Analysis of the 1990–2019 Global Burden of Disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022:zwac256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinault LL, Weichenthal S, Crouse DL, et al. Associations between fine particulate matter and mortality in the 2001 Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohort. Environ Res. 2017;159:406–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motairek I, Deo SV, Elgudin Y, et al. Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Long-Term Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Adv. 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orellano P, Reynoso J, Quaranta N, Bardach A, Ciapponi A. Short-term exposure to particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone (O3) and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2020;142:105876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mustafic H, Jabre P, Caussin C, et al. Main air pollutants and myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;307:713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niu Z, Liu F, Yu H, Wu S, Xiang H. Association between exposure to ambient air pollution and hospital admission, incidence, and mortality of stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of more than 23 million participants. Environ Health Prev Med. 2021;26:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexeeff SE, Liao NS, Liu X, Van Den Eeden SK, Sidney S. Long‐Term PM2.5 Exposure and Risks of Ischemic Heart Disease and Stroke Events: Review and Meta‐Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e016890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niu Z, Duan Z, Yu H, et al. Association between long-term exposure to ambient particulate matter and blood pressure, hypertension: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Health Res. 2022;0:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eze IC, Hemkens LG, Bucher HC, et al. Association between Ambient Air Pollution and Diabetes Mellitus in Europe and North America: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGuinn LA, Schneider A, McGarrah RW, et al. Association of long-term PM2.5 exposure with traditional and novel lipid measures related to cardiovascular disease risk. Environ Int. 2019;122:193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Yao Y, Xie W, et al. Association of long-term exposure to PM2.5 with blood lipids in the Chinese population: Findings from a longitudinal quasi-experiment. Environ Int. 2021;151:106454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD, Biswal S, Rajagopalan S. Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease: lessons learned from air pollution. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:656–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daiber A, Oelze M, Steven S, Kröller-Schön S, Münzel T. Taking up the cudgels for the traditional reactive oxygen and nitrogen species detection assays and their use in the cardiovascular system. Redox Biol. 2017;12:35–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li N, Xia T, Nel AE. The role of oxidative stress in ambient particulate matter-induced lung diseases and its implications in the toxicity of engineered nanoparticles. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1689–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao X, Zhong J, Brook RD, Rajagopalan S. Effect of Particulate Matter Air Pollution on Cardiovascular Oxidative Stress Pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;28:797–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Q, Dai L, Wang Y, et al. Association of Short-term Exposure to Air Pollution With Mortality in Older Adults. JAMA. 2017;318:2446–2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Q, Wang Y, Zanobetti A, et al. Air Pollution and Mortality in the Medicare Population. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2513–2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajagopalan S, Al -Kindi Sadeer G., Brook RD. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2054–2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanphear BP, Rauch S, Auinger P, Allen RW, Hornung RW. Low-level lead exposure and mortality in US adults: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e177–e184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anon. Global Mercury Assessment 2018 | UNEP - UN Environment Programme Accessed May 10, 2023. https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/global-mercury-assessment-2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu XF, Lowe M, Chan HM. Mercury exposure, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2021;193:110538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moon K, Guallar E, Navas-Acien A. Arsenic exposure and cardiovascular disease: an updated systematic review. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14:542–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamas GA, Navas-Acien A, Mark DB, Lee KL. Heavy Metals, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Unexpected Benefits of Edetate Disodium Chelation Therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2411–2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tellez-Plaza M, Jones MR, Dominguez-Lucas A, Guallar E, Navas-Acien A. Cadmium Exposure and Clinical Cardiovascular Disease: a Systematic Review. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15: 10.1007/s11883-013-0356-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song Y, Chou EL, Baecker A, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals, risk of type 2 diabetes, and diabetes-related metabolic traits: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes. 2016;8:516–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Kindi S, Motairek I, Khraishah H, Rajagopalan S. Cardiovascular Disease Burden Attributable to Non-Optimal Temperature: Analysis of the 1990–2019 Global Burden of Disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023:zwad130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khraishah H, Alahmad B, Ostergard RL, et al. Climate change and cardiovascular disease: implications for global health. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19:798–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bunker A, Wildenhain J, Vandenbergh A, et al. Effects of Air Temperature on Climate-Sensitive Mortality and Morbidity Outcomes in the Elderly; a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Epidemiological Evidence. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:258–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khatana SAM, Werner RM, Groeneveld PW. Association of Extreme Heat and Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States: A County-Level Longitudinal Analysis From 2008 to 2017. Circulation. 2022;146:249–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu Z, FitzGerald G, Guo Y, Jalaludin B, Tong S. Impact of heatwave on mortality under different heatwave definitions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2016;89–90:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryti NRI, Guo Y, Jaakkola JJK. Global Association of Cold Spells and Adverse Health Effects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alahmad B, Khraishah H, Royé D, et al. Associations Between Extreme Temperatures and Cardiovascular Cause-Specific Mortality: Results From 27 Countries. Circulation. 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu X, Han W, Wang Y, et al. Does air pollution modify temperature-related mortality? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2022;210:112898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stewart S, Keates AK, Redfern A, McMurray JJV. Seasonal variations in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:654–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karjalainen J, Viitasalo M. Fever and Cardiac Rhythm. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:1169–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peters A, Schneider A. Cardiovascular risks of climate change. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaudio FG, Grissom CK. Cooling Methods in Heat Stroke. J Emerg Med. 2016;50:607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Epstein Y, Yanovich R. Heatstroke. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2449–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lim Y-H, Park M-S, Kim Y, Kim H, Hong Y-C. Effects of cold and hot temperature on dehydration: a mechanism of cardiovascular burden. Int J Biometeorol. 2015;59:1035–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rohrer MJ, Natale AM. Effect of hypothermia on the coagulation cascade. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:1402–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hata T, Ogihara T, Maruyama A, et al. The seasonal variation of blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1982;4:341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kunes J, Tremblay J, Bellavance F, Hamet P. Influence of environmental temperature on the blood pressure of hypertensive patients in Montréal. Am J Hypertens. 1991;4:422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katayama Y, Tanaka A, Taruya A, et al. Increased plaque rupture forms peak incidence of acute myocardial infarction in winter. Int J Cardiol. 2020;320:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kinney PL, Pinkerton KE. Heatwaves and Air Pollution: a Deadly Combination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206:1060–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chandrabose M, Rachele JN, Gunn L, et al. Built environment and cardio-metabolic health: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Obes Rev. 2019;20:41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Howell NA, Tu JV, Moineddin R, Chu A, Booth GL. Association Between Neighborhood Walkability and Predicted 10‐Year Cardiovascular Disease Risk: The CANHEART (Cardiovascular Health in Ambulatory Care Research Team) Cohort. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adhikari B, Delgado-Ron JA, Van den Bosch M, et al. Community design and hypertension: Walkability and park access relationships with cardiovascular health. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2021;237:113820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Markevych I, Schoierer J, Hartig T, et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ Res. 2017;158:301–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bowyer RCE, Twohig-Bennett C, Coombes E, et al. Microbiota composition is moderately associated with greenspace composition in a UK cohort of twins. Sci Total Environ. 2022;813:152321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bikomeye JC, Beyer AM, Kwarteng JL, Beyer KMM. Greenspace, Inflammation, Cardiovascular Health, and Cancer: A Review and Conceptual Framework for Greenspace in Cardio-Oncology Research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao Y, Bao W-W, Yang B-Y, et al. Association between greenspace and blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2022;817:152513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lanki T, Siponen T, Ojala A, et al. Acute effects of visits to urban green environments on cardiovascular physiology in women: A field experiment. Environ Res. 2017;159:176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Chronic Disease among LowIncome NHANES Participants. J Nutr. 2010;140:304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coleman-Jensen A Household Food Security in the United States in 2018. 2018. Published online2018.

- 74.Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food Insecurity Research in the United States: Where We Have Been and Where We Need to Go. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2018;40:119–135. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sun Y, Liu B, Rong S, et al. Food Insecurity Is Associated With Cardiovascular and All‐Cause Mortality Among Adults in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dong T, Harris K, Freedman D, et al. Food insecurity and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults with diabetes. Nutrition. 2023;106:111865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2014;349:g4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamelin A-M, Beaudry M, Habicht J-P. Characterization of household food insecurity in Québec: food and feelings. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2002;54:119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac J-C, Levy RB, Louzada MLC, Jaime PC. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Monteiro CA, Moubarac J-C, Cannon G, Ng SW, Popkin B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes Rev Off J Int Assoc Study Obes. 2013;14 Suppl 2:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang Z, Jackson SL, Martinez E, Gillespie C, Yang Q. Association between ultraprocessed food intake and cardiovascular health in US adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the NHANES 2011–2016. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113:428–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mendoza JA, Drewnowski A, Christakis DA. Dietary Energy Density Is Associated With Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome in U.S. Adults. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:974–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Svetkey LP, Simons-Morton DG, Proschan MA, et al. Effect of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet and reduced sodium intake on blood pressure control. J Clin Hypertens Greenwich Conn. 2004;6:373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang Z, Gillespie C, Yang Q. Plasma trans-fatty acid concentrations continue to be associated with metabolic syndrome among US adults after reductions in trans-fatty acid intake. Nutr Res N Y N. 2017;43:51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ludwig DS. Technology, diet, and the burden of chronic disease. JAMA. 2011;305:1352–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jilani MH, Javed Z, Yahya T, et al. Social Determinants of Health and Cardiovascular Disease: Current State and Future Directions Towards Healthcare Equity. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021;23:55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bevan GH, Freedman DA, Lee EK, Rajagopalan S, Al-Kindi SG. Association between ambient air pollution and county-level cardiovascular mortality in the United States by social deprivation index. Am Heart J. 2021;235:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Motairek I, Sharara J, Makhlouf MHE, et al. Association Between Particulate Matter Pollution and CKD Mortality by Social Deprivation. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2022:S02726386(22)01015–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129:19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Solorzano A Review of Confronting Environmental Racism: Voices from the Grassroots. Hum Ecol Rev. 1993;1:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Venkataraman M, Grzybowski S, Sanderson D, Fischer J, Cherian A. Environmental racism in Canada. Can Fam Physician. 2022;68:567–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Motairek I, Chen Z, Makhlouf MHE, Rajagopalan S, Al-Kindi S. Historical neighbourhood redlining and contemporary environmental racism. Local Environ. 2022;0:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Motairek I, Lee EK, Janus S, et al. Historical Neighborhood Redlining and Contemporary Cardiometabolic Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80:171–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Di Q, Wang Y, Zanobetti A, et al. Air Pollution and Mortality in the Medicare Population. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2513–2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Colmer J, Hardman I, Shimshack J, Voorheis J. Disparities in PM2.5 air pollution in the United States. Science. 2020;369:575–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jbaily A, Zhou X, Liu J, et al. Air pollution exposure disparities across US population and income groups. Nature. 2022;601:228–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Motairek I, Rajagopalan S, Al-Kindi S. The “Heart” of Environmental Justice. Am J Cardiol. 2022. Published onlineDecember 14, 2022. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bevan GH, Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD, Münzel T, Rajagopalan S. Ambient Air Pollution and Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bell ML, Ebisu K, Belanger K. Ambient Air Pollution and Low Birth Weight in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1118–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gorr MW, Velten M, Nelin TD, Youtz DJ, Sun Q, Wold LE. Early life exposure to air pollution induces adult cardiac dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H1353–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rossiello MR, Szema A. Health Effects of Climate Change-induced Wildfires and Heatwaves. Cureus. 2019;11:e4771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Anon. Global Warming of 1.5 °C — Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pope CA, Ezzati M, Dockery DW. Fine-Particulate Air Pollution and Life Expectancy in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:376–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Landrigan PJ, Fuller R, Acosta NJR, et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. The Lancet. 2018;391:462–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang X, Chen X, Zhang X. The impact of exposure to air pollution on cognitive performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:9193–9197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lelieveld J, Klingmüller K, Pozzer A, Burnett RT, Haines A, Ramanathan V. Effects of fossil fuel and total anthropogenic emission removal on public health and climate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:7192–7197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Influence of urban and transport planning and the city environment on cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mueller N, Rojas-Rueda D, Basagaña X, et al. Health impacts related to urban and transport planning: A burden of disease assessment. Environ Int. 2017;107:243–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Scheepers CE, Wendel-Vos GCW, den Broeder JM, van Kempen EEMM, van Wesemael PJV, Schuit AJ. Shifting from car to active transport: A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. Transp Res Part Policy Pract. 2014;70:264–280. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Khreis H, van Nunen E, Mueller N, Zandieh R, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Commentary: How to Create Healthy Environments in Cities. Epidemiology. 2017;28:60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Martinez GS, Linares C, Ayuso A, Kendrovski V, Boeckmann M, Diaz J. Heat-health action plans in Europe: Challenges ahead and how to tackle them. Environ Res. 2019;176:108548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]