Abstract

Background:

Information on frequency and timing of mental disorder onsets across the lifespan is of fundamental importance for public health planning. Broad-based cross-national estimates of this sort from coordinated general population surveys were last updated 15 years ago.

Methods:

Data were analyzed for 156,331 adults (18 years and older) in the World Mental Health surveys, a coordinated series of cross-sectional face-to-face community epidemiological surveys in 29 countries administered between 2001 and 2022. A fully structured lay-administered psychiatric diagnostic interview was used to assess age-of-onset, lifetime prevalence, and morbid risk of 13 mental disorders through age 75 across surveys by sex. Ethnicity was not assessed.

Outcomes:

Lifetime prevalence (percent [95% CI]) of any mental disorder was 28·6% (27·9-29·2%) males and 29·8% (29·2-30·3%) females. Morbid risk by age 75 was substantially higher – 46·4% (44·9-47·8%) for males and 53·1% (51·9-54·3%) for females. Conditional probabilities of first onset peaked at age 15, with median age-of-onset of 19 for males and 20 for females. The two most prevalent disorders were alcohol abuse and major depression for males and major depression and specific phobia disorder for females.

Interpretation:

By age 75, approximately half the population can expect to develop one or more of the mental disorders considered here. These disorders typically first emerge in childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood. Given these findings, services need to have the capacity to detect and treat common mental disorders promptly and to optimize services that suit patients in these critical parts of the life course.

INTRODUCTION

Age-of-onset (AOO), lifetime prevalence (ie, the proportion of survey respondents with a history of disorder at the time of assessment), and lifetime morbid risk (ie, the projected lifetime prevalence in the sample as of a fixed age) are essential features of epidemiology. In recent decades, psychiatric epidemiology has demonstrated that many mental disorders have an onset in the first and second decades of life.1,2 This is in contrast to most other non-communicable disorders, (eg, respiratory and cardiovascular disorders, cancer), which typically have onsets in late adulthood. Understanding these AOO patterns is important for several reasons. First, we need to ensure that the correct mix of services is available to provide prompt treatments to the right groups (eg, early intervention for teenagers with mental disorders). Second, we need to focus research efforts on understanding risk factors for different types of mental disorders during critical parts of the lifespan. Third, register-based family pedigree studies,3 and genome-wide association studies based on case-control or case-cohort studies4 increasingly use AOO distributions to weight non-cases at the time of sample ascertainment according to their estimated future morbid risk of the disorder of interest, making it important to have accurate information about AOO distributions, although other factors are also important in controlling for bias in these types of studies. Fourth, disease-specific AOO distributions are important inputs for models used to estimate the non-fatal burden of disease.5

The most comprehensive data on AOO, lifetime prevalence, and morbid risk of common mental disorders to date were reported 15 years ago by the WMH Survey collaborators based on data obtained in coordinated community epidemiologic surveys from 17 countries.1 Key features (eg, median and other quantiles) were reported, providing compelling evidence that many mental disorders first emerge between childhood and early adulthood. More recently, Solmi and colleagues presented a systematic review and meta-analysis of published literature on AOO (n = 192 studies).2 The authors noted that included studies were heterogeneous, making it difficult to pool data, but tables nonetheless displayed key properties of AOO distributions (eg, peak AOO, proportion with onset by age 25) by disorder type and sex.

Most commonly, epidemiologic studies show sex-specific incidence rates by age; that is, rate of first onset at specific ages defined as a ratio of the number of disorder onsets divided by the number of people who never had the disorder up to that age and lived through that age. Figures based on these estimates allow calculation of cumulative lifetime risk by sex. Whereas incidence rates can either increase or decrease with increasing age, cumulative risk curves are always non- decreasing. Univariate statistics can be derived from these cumulative risk curves (eg, median, 25th and 75th percentiles of the AOO distributions) to estimate lifetime morbid risk (ie, the projected proportion of the population who will have a lifetime disorder as of a given age). However, morbid risk does not tell us how many people experienced the disorder as of their current age, which is known as lifetime prevalence. By comparing the ratio of morbid risk as of some age (in our case, age 75) to lifetime prevalence (henceforth MR/LP ratio), we can appreciate how age-related incidence interacts with background population age structure. Disorders with peak incidence in early life will have a lower MR/LP ratio than disorders with peak hazard rates later in life.

Existing data on AOO and morbid risk are prone to under-reporting,6 as survey data rely on memory. Recall bias may result in a systematic bias against recalling events in the distant past or telescoping the recalled AOO. While the structured interview used in WMH is designed to reduce recall bias,7 accuracy can also be improved by focusing on respondents who reported more recent onsets (eg, in the last 10 years).8 This method is used here to update WMH AOO and morbid risk estimates. In the years since the 2007 publication of the WMH AOO study, WMH surveys have been completed with 74,989 respondents, including some in 13 additional countries. We combine these new data with data from the earlier WMH surveys to provide updated and improved estimates of AOO distributions, lifetime prevalence, and morbid risk and to provide look-up tables for use in a range of epidemiologic and genetic studies.

METHODS

Samples

Data were obtained from 32 WMH surveys carried out in 29 countries (12 low- and middle-income countries; 17 high-income countries). All surveys were based on rigorous multi-stage geographically clustered area probability household sampling designs. An overview of samples can be found in Table 1. A detailed description of sample designs is presented in an earlier report.9 The weighted average response rate across surveys was 63·6%. A discussion of possible reasons for variation in WMH response rates is presented elsewhere.10

Table 1.

WMH sample characteristics by World Bank income categoriesa

| Sample size | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country by income category |

Surveyb | Sample characteristicsc | Field dates |

Age range |

Part I | Part II | Part II and age ≤ 44d |

Response ratee |

| I. Low and middle income countries | ||||||||

| Brazil - São Paulo | São Paulo Megacity | São Paulo metropolitan area. | 2005-8 | 18-93 | 5,037 | 2,942 | NA | 81·3 |

| Bulgaria | NSHS | Nationally representative. | 2002-6 | 18-98 | 5,318 | 2,233 | 741 | 72·0 |

| Bulgaria 2 | NSHS- 2 | Nationally representative. | 2016-17 | 18-91 | 1,508 | 578 | NA | 61·0 |

| Colombiag | NSMH | All urban areas of the country (approximately 73% of the total national population). | 2003 | 18-65 | 4,426 | 2,381 | 1,731 | 87·7 |

| Colombia – Medellin | MMHHS | Medellin metropolitan area | 2011-12 | 19-65 | 3,261 | 1,673 | NA | 97·2 |

| Iraq | IMHS | Nationally representative. | 2006-7 | 18-96 | 4,332 | 4,332 | NA | 95·2 |

| Lebanong | LEBANON | Nationally representative. | 2002-3 | 18-94 | 2,857 | 1,031 | 595 | 70·0 |

| Mexicog | M-NCS | All urban areas of the country (approximately 75% of the total national population). 21 of the 36 states in the country, representing | 2001-2 | 18-65 | 5,782 | 2,362 | 1,736 | 76·6 |

| Nigeriag | NSMHW | 57% of the national population. The surveys were conducted in Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa and Efik languages. | 2002-4 | 18-100 | 6,752 | 2,143 | 1,203 | 79·3 |

| Peru | EMSMP | Five urban areas of the country (approximately 38% of the total national population). | 2004-5 | 18-65 | 3,930 | 1,801 | 1,287 | 90·2 |

| PRCf-Shenzhenh | Shenzhen | Shenzhen metropolitan area. Included temporary residents as well as household residents. | 2005-7 | 18-88 | 7,132 | 2,475 | NA | 80·0 |

| Romania | RMHS | Nationally representative. | 2005-6 | 18-96 | 2,357 | 2,357 | NA | 70·9 |

| South Africag,h | SASH | Nationally representative. | 2002-4 | 18-92 | 4,315 | 4,315 | NA | 87·1 |

| Ukraineg | CMDPSD | Nationally representative. | 2002 | 18-91 | 4,725 | 1,720 | 541 | 78·3 |

| TOTAL | (61,732) | (32,343) | (7,834) | 80·4 | ||||

| II. High-income countries | ||||||||

| Argentina | AMHES | Eight largest urban areas of the country (approximately 50% of the total national population). | 2015 | 18-98 | 3,927 | 2,116 | NA | 77·3 |

| Australiah | NSMHWB | Nationally representative. | 2007 | 18-85 | 8,463 | 8,463 | NA | 60·0 |

| Belgiumg | ESEMeD | Nationally representative. The sample was selected from a national register of Belgium residents. | 2001-2 | 18-95 | 2,419 | 1,043 | 486 | 50·6 |

| Franceg | ESEMeD | Nationally representative. The sample was selected from a national list of households with listed telephone numbers. | 2001-2 | 18-97 | 2,894 | 1,436 | 727 | 45·9 |

| Germanyg | ESEMeD | Nationally representative. | 2002-3 | 19-95 | 3,555 | 1,323 | 621 | 57·8 |

| Israelg | NHS | Nationally representative. | 2003-4 | 21-98 | 4,859 | 4,859 | NA | 72·6 |

| Italyg | ESEMeD | Nationally representative. The sample was selected from municipality resident registries. | 2001-2 | 18-100 | 4,712 | 1,779 | 853 | 71·3 |

| Japang | WMHJ 2002-2006 | Eleven metropolitan areas. | 2002-6 | 20-98 | 4,129 | 1,682 | NA | 55·1 |

| Netherlandsg | ESEMeD | Nationally representative. The sample was selected from municipal postal registries. | 2002-3 | 18-95 | 2,372 | 1,094 | 516 | 56·4 |

| New Zealandg,h | NZMHS | Nationally representative. | 2004-5 | 18-98 | 12,790 | 7,312 | NA | 73·3 |

| N. Ireland | NISHS | Nationally representative. | 2005-8 | 18-97 | 4,340 | 1,986 | NA | 68·4 |

| Poland | EZOP | Nationally representative | 2010-11 | 18-65 | 10,081 | 4,000 | 2,276 | 50·4 |

| Portugal | NMHS | Nationally representative. | 2008-9 | 18-81 | 3,849 | 2,060 | 1,070 | 57·3 |

| Qatar | WMHQ | Nationally representative. The sample was selected from a national list of cellular telephone numbers and restricted to Qatari nationals and Arab expatriates. | 2019-22 | 18-90 | 5,195 | 2,583 | NA | 19·2i |

| Saudi Arabiah | SNMHS | Nationally representative | 2013-2016 | 18-65 | 3,638 | 1,793 | NA | 61·0 |

| Spaing | ESEMeD | Nationally representative. | 2001-2 | 18-98 | 5,473 | 2,121 | 960 | 78·6 |

| Spain-Murcia | PEGASUS-Murcia | Murcia region. Regionally representative. | 2010-12 | 18-96 | 2,621 | 1,459 | NA | 67·4 |

| United Statesg | NCS-R | Nationally representative. | 2001-3 | 18-99 | 9,282 | 5,692 | 3,197 | 70·9 |

| TOTAL | (94,599) | (52,801) | (10,706) | 56·0 | ||||

| III. TOTAL | (156,331) | (85,144) | (18,540) | 63·6 | ||||

Abbreviations: NA, Not Applicable.

The World Bank (2012) Data. Accessed May 12, 2012 at: http://data.worldbank.org/country. Some of the WMH countries have moved into new income categories since the surveys were conducted. The income groupings above reflect the status of each country at the time of data collection. The current income category of each country is available at the preceding URL.

NSHS (Bulgaria National Survey of Health and Stress); NSMH (The Colombian National Study of Mental Health); MMHHS (Medellín Mental Health Household Study); IMHS (Iraq Mental Health Survey); LEBANON (Lebanese Evaluation of the Burden of Ailments and Needs of the Nation); M-NCS (The Mexico National Comorbidity Survey); NSMHW (The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing); EMSMP (La Encuesta Mundial de Salud Mental en el Peru); RMHS (Romania Mental Health Survey); SASH (South Africa Health Survey); CMDPSD (Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption); AMHES (Argentina Mental Health Epidemiologic Survey); NSMHWB (National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing); ESEMeD (The European Study Of The Epidemiology Of Mental Disorders); WMHJ2002-2006 (World Mental Health Japan Survey); NZMHS (New Zealand Mental Health Survey); NISHS (Northern Ireland Study of Health and Stress); EZOP (Epidemiology of Mental Disorders and Access to Care Survey); NMHS (Portugal National Mental Health Survey); WMHQ (World Mental Health Qatar Study);SNMHS (Saudi National Mental Health Survey); PEGASUS-Murcia (Psychiatric Enquiry to General Population in Southeast Spain-Murcia); NCS-R (The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication).

Most WMH surveys are based on stratified multistage clustered area probability samples of household in the countries under study. Areas equivalent to counties or municipalities in the US were selected in the first stage followed by one or more subsequent stages of geographic sampling (e.g., towns within counties, blocks within towns, households within blocks) to arrive at a nationally representative sample of households. In each household, an attempt was made to obtain a listing of all adult household members. And then one or, in the case of a few surveys, two people were selected from this listing at random to be interviewed. No substitution of households was made when the originally sampled household could not be reached or listed. No substitution was allowed when the originally sampled household resident could not be interviewed. These household samples were selected from Census area data in all countries other than France (where telephone directories were used to select households) and the Netherlands (where postal registries were used to select households). Several WMH surveys (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain-Murcia) used municipal, country resident or universal health-care registries to select respondents without listing households. The Japanese sample is the only totally un-clustered sample, with households randomly selected in each of the 11 metropolitan areas and one random respondent selected in each sample household. 21 of the 32 surveys are based on nationally representative household samples, whereas the others are based on regional samples.

Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria 2, Colombia-Medellin, Iraq, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, PRC - Shenzhen, Qatar, Romania, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Spain-Murcia did not have an age restricted Part 2 sample. All other surveys, with the exception of Nigeria and Ukraine (which were age restricted to ≥ 39) were age restricted to ≤ 44.

The response rate is calculated as the ratio of the number of households in which an interview was completed to the number of households originally sampled, excluding from the denominator households known not to be eligible either because of being vacant at the time of initial contact or because the residents were unable to speak the designated languages of the survey. The weighted average response rate is 63·6%.

People’s Republic of China

This was one of the surveys included in the 2007 WMH report.1 All other surveys were carried out subsequent to that report.

For the purposes of cross-national comparisons we limit the sample to those 18+.

The survey began as a face-to-face household survey and had to switch to be phone-based due to the COVID-19 pandemic occurring shortly after the study started.

Interviews were in two parts. Part I was administered to one, or in a few surveys two, randomly selected adults in each sampled household. Part I contained assessments of core mental disorders (depression, mania, panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, substance use disorder). A Part I weight adjusted for differential probabilities of selection within households (based on number of eligible adults in the household) and between households (based on discrepancies between Census estimates of number of households in a sample segment and the number of households found when the interviewers visited the segments). Part II, which included questions about other mental disorders and correlates, was then administered to 100% of Part I respondents who met lifetime criteria for any Part I disorder in addition to a probability subsample of other Part I respondents. A Part II weight equal to the inverse of the probability of selection into Part II was used to restore the representativeness of the Part II sample, resulting in prevalence estimates of Part I disorders in the doubly weighted Part II sample having the same expected values weighted prevalence estimates in the Part I sample. A third weight was then applied to the doubly weighted Part II sample to calibrate discrepancies between sample and population distributions on the cross-classification of Census socio-demographic and geographic variables.

Choice of primary measures

The WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)11 was used to assess DSM-IV disorders in the WMH surveys (other than DSM-5 disorders in the most recent survey, which was carried out in Qatar). The CIDI is a fully structured diagnostic interview administered by trained lay interviewers who read questions word for word and record answers in prespecified categories. Consistent interviewer training and quality control monitoring procedures were used across surveys.12 Based on DSM-IV/DSM-5 criteria, thirteen specific diagnoses were identified: panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol abuse disorder, alcohol dependence disorder, drug abuse disorder, drug dependence disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder. In addition, diagnoses were pooled for any anxiety disorder, any mood disorder, any substance use disorder, any externalizing disorder. and any disorder. Clinical reappraisal studies indicated that lifetime diagnoses based on the CIDI have good concordance with diagnoses based on masked semi-structured (ie, allowing open-ended clinical probing) clinical research diagnostic interviews.13

Respondents who met lifetime criteria for a given disorder were asked about their AOO using a question series designed to review core symptoms and encourage accurate dating. For example, the question about onset of a major depressive episode was administered after the completion of a question series that focused on symptoms of the respondents’ worst lifetime establishing that lifetime criteria were met. The next question after completing that question series was: “Think of the very first time in your life when you had an episode lasting two weeks or longer when most of the day nearly every day you felt (sad/or/discouraged/or/uninterested) and also had some of the other problems we just reviewed. Can you remember your exact age (Emphasis in original)?” Respondents who could not remember their exact ages were then probed for the earliest age they could clearly remember having the syndrome with the goal of obtaining upper bound AOO estimates. It is noteworthy, though, that symptom-level assessments were only obtained for worst lifetime episodes, not for first onsets, introducing the possibility that AOO estimates were for subthreshold episodes. A more detailed description of the CIDI is presented elsewhere.11

Statistical analyses

Results were pooled across surveys with sums of weights equal to numbers of respondents rather than equal to country populations. Lifetime prevalence was estimated in the final doubly weighted and calibrated Part II sample as the proportion of respondents who ever had a given disorder as of interview. For each disorder, conditional probability of first onset at each year of life t (ie, incidence by year of life) was then estimated in the subsample of respondents who were at least t years of age and reported not having had the disorder as of age t-1. In calculating these conditional probabilities, we used information only from respondents in the age range t to t + 10 to minimize recall bias. We then calculated cumulative lifetime disorder risk up to age 75 (ie, morbid risk) from these incidence data using the standard exponential formula.14 Smoothing was used with a five-year bandwidth to reduce instability in estimates. Standard errors of both incidence rates and cumulative incidence curves were calculated using the jackknife repeated replications (JRR) simulation method taking into consideration both the weighting and geographic clustering of the WMH data.15 In using JRR, surveys were treated as sets of independent strata and strata within surveys were defined as primary sampling units (equivalent to counties or municipalities in the USA). The sampling error calculation units (subsamples within strata) used to generate the JRR estimates were second-stage sampling units equivalent to neighborhoods.

It is noteworthy that the approach used here to estimate conditional probability of first disorder onset within specific years of life took into consideration right censoring (ie, the fact that not all respondents reached the age of t as of the time of survey) by excluding (censoring) respondents who are not yet t years of age from the denominator. The restriction of estimates to respondents no older than t + 10 years of age also reduced the effects of bias due to premature mortality. However, premature mortality bias could still occur if mortality depended on history of mental disorders and systematic nonresponse based on factors related to the age-specific disorder risks. This possibility of residual bias is inevitable in community surveys, although it can be addressed in population registry data.16 The direction of this potential bias cannot be assessed rigorously in the absence of information about disorder risk and censoring. However, given that people with mental disorders have reduced life spans17 and that people with known histories of psychiatric hospitalization have been found to have comparatively low response rates in epidemiologic surveys,18 it is reasonable to assume that bias is in the direction of under-estimating risk.

We compared lifetime prevalence estimates by sex with Wald chi-square tests and two-sided p values. We show these estimates along with 95% confidence intervals. As the WMH data are both geographically clustered and weighted, the design-based Taylor series linearization method implemented in version 9.4 of SAS software19 was used to estimate standard errors. An interactive data-visualization website is available here [https://csievert.shinyapps.io/mental-aoo/]. The age- and sex- specific data underlying the figures are available in the Supplementary Data and can be downloaded from the data visualization website.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from respondents before beginning the interview. Procedures for obtaining informed consent and data protection (ethical approvals) were somewhat different across countries but were always obtained from the institutional review boards of the collaborating organizations in each country before beginning the survey. Data use agreements allowed only de-identified data to be deposited in the centralized WMH server and required all analyses to be carried out on that server only by trained and approved WMH analysts.

Role of the funding source

None of the funders had any role in the design, analysis, interpretation of results, or preparation of this paper. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or governments.

RESULTS

Lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder was 28·6% (95% CI = 27·9-29·2%) for males and 29·8% (95% CI = 29·2-30·3%) for females (see Table 2). Lifetime prevalence of any anxiety disorder was 11·3% (95% CI = 10·9-11·7%) for males and 18·8% (95% CI = 18·3-19·2%) for females and of any mood disorder 9·5% (95% CI = 9·2-9·7%) for males and 15·4% (95% CI =15·1-15·7%) for females. The three specific mental disorders with highest lifetime prevalence for males were alcohol abuse disorder (13·7%, 95% CI = 13·3-14·1%), major depressive disorder (7·5%, 95% CI = 7·2-7·7%) and specific phobia (5·0%, 95% CI =4·8-5·3%) and for females were major depressive disorder (13·6%, 95% CI = 13·3-13·9%), specific phobia (10·0%, 95% CI = 9·7-10·2%) and post-traumatic stress disorder (5·4%, 95% CI =5·2-5·7%).

Table 2.

Count and lifetime prevalence of disorders, by sex

| Male | Female | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lifetime cases at time of interview |

Number of people in the sample in which the disorder was assessed |

Lifetime prevalence | Number of lifetime cases at time of interview |

Number of people in the sample in which the disorder was assessed |

Lifetime prevalence | Test statistics | |||

| Type of mental disorder | N1 | N2 | % | (95% CI) | N1 | N2 | % | (95% CI) | χ2 (p-value) |

| I. Anxiety disorders | |||||||||

| Panic disorder and/or agoraphobia | 1309 | 67808 | 1·9 | (1·8-2·1) | 3303 | 83328 | 3·7 | (3·6-3·9) | 289·6 (<0·0001) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1955 | 71023 | 2·7 | (2·6-2·9) | 4500 | 85308 | 5·0 | (4·8-5·1) | 396·8 (<0·0001) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1456 | 35446 | 2·7 | (2·5-2·9) | 3721 | 47223 | 5·4 | (5·2-5·7) | 279·8 (<0·0001) |

| Social phobia | 2254 | 65428 | 3·5 | (3·3-3·7) | 3770 | 80849 | 4·6 | (4·4-4·8) | 69·5 (<0·0001) |

| Specific phobia | 2825 | 56355 | 5·0 | (4·8-5·3) | 6954 | 68781 | 10·0 | (9·7-10·2) | 744·6 (<0·0001) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 6559 | 39060 | 11·3 | (10·9-11·7) | 13830 | 50741 | 18·8 | (18·3-19·2) | 669·8 (<0·0001) |

| II. Mood disorders | |||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 5324 | 71023 | 7·5 | (7·2-7·7) | 12144 | 85308 | 13·6 | (13·3-13·9) | 1160·5 (<0·0001) |

| Bipolar disorder | 1398 | 57559 | 2·5 | (2·4-2·7) | 1593 | 68307 | 2·3 | (2·1-2·4) | 7·2 (0·0074) |

| Any mood disorder | 6674 | 71023 | 9·5 | (9·2-9·7) | 13675 | 85308 | 15·4 | (15·1-15·7) | 880·6 (<0·0001) |

| III. Substance use disorders | |||||||||

| Alcohol abuse disorder | 7629 | 52757 | 13·7 | (13·3-14·1) | 2602 | 67650 | 3·3 | (3·1-3·4) | 2226·0 (<0·0001) |

| Alcohol dependence | 2056 | 52757 | 3·5 | (3·3-3·7) | 840 | 67650 | 0·9 | (0·9-1·0) | 516·5 (<0·0001) |

| Drug abuse disorder | 2083 | 46180 | 4·1 | (3·9-4·3) | 1204 | 59642 | 1·7 | (1·6-1·8) | 337·4 (<0·0001) |

| Drug dependence | 711 | 46180 | 1·4 | (1·3-1·6) | 490 | 59642 | 0·6 | (0·6-0·7) | 89·9 (<0·0001) |

| Any substance use disorder | 7926 | 46939 | 15·6 | (15·2-16·1) | 3181 | 60943 | 4·5 | (4·2-4·7) | 1960·2 (<0·0001) |

| IV. Externalizing disorders | |||||||||

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 571 | 19402 | 2·4 | (2·1-2·7) | 575 | 25116 | 1·5 | (1·3-1·7) | 26·1 (<0·0001) |

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 1326 | 40529 | 3·5 | (3·2-3·7) | 1267 | 49561 | 2·5 | (2·4-2·7) | 39·4 (<0·0001) |

| Any externalizing disorder | 1524 | 30526 | 4·3 | (3·9-4·6) | 1563 | 39231 | 3·1 | (2·9-3·3) | 43·0 (<0·0001) |

| V. Any mental disorder | 14662 | 36700 | 28·6 | (27·9-29·2) | 21485 | 48444 | 29·8 | (29·2-30·3) | 9·2 (0·0024) |

Abbreviations: N1, observed (i.e., unweighted) number of respondents classified as meeting criteria for the disorder; N2, observed (i.e., unweighted) number of respondents in the sample; %, the ratio of N1 to N2 in the weighted, not unweighted, data; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval of %; χ2, Wald test for significance of difference between male and female values of %; P, P value of χ2 test.

As expected, projected lifetime morbid risk by age 75 for each mental disorder was considerably higher than observed lifetime prevalence at interview. Lifetime morbid risk of any disorder as of age 75 was 46·4% (95% CI = 44·9-47·8%) for males and 53·1% (95% CI = 51·9-54·3%) for females. The three disorders with highest lifetime morbid risk for men were alcohol abuse disorder (21·6%, 95% CI = 20·6-22·7%), major depressive disorder (20·1%, 95% CI = 19·2-20·9%), and drug abuse disorder (7·9%, 95% CI = 7·2-8·7%) (Table 3) and for females were major depressive disorder (34·0%, 95% CI = 33·2-34·9%), post-traumatic stress disorder (12·6%, 95% CI = 11·7-13·5%) and generalized anxiety disorder 12·5%, 95% CI = 11·8-13·2%).

Table 3.

Morbid risk (per 100 participants) at 75 and ratio of morbid risk/lifetime prevalence by sex

| Morbid risk (per 100 participants at age 75) | Ratio of morbid risk to lifetime prevalence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||||

| Lifetime disorder | MR | (95% CI) | MR | (95% CI) | MR/LP | (95% CI) | MR/LP | (95% CI) |

| I. Anxiety disorders | ||||||||

| Panic disorder and/or agoraphobia | 3·6 | (3·2-3·9) | 7·3 | (6·8-7·8) | 1·8 | (1·7-2·0) | 2·0 | (1·9-2·0) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 6·5 | (5·9-7·0) | 12·5 | (11·8-13·2) | 2·4 | (2·2-2·5) | 2·5 | (2·4-2·6) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 5·7 | (5·1-6·3) | 12·6 | (11·7-13·5) | 2·1 | (1·9-2·2) | 2·3 | (2·2-2·4) |

| Social phobia | 4·2 | (3·8-4·6) | 6·0 | (5·5-6·4) | 1·2 | (1·1-1·3) | 1·3 | (1·2-1·4) |

| Specific phobia | 5·9 | (5·3-6·5) | 11·6 | (10·9-12·2) | 1·2 | (1·1-1·2) | 1·2 | (1·1-1·2) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 18·3 | (17·3-19·4) | 31·0 | (29·9-32·2) | 1·6 | (1·6-1·7) | 1·7 | (1·6-1·7) |

| II. Mood disorders | ||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 20·1 | (19·2-20·9) | 34·0 | (33·2-34·9) | 2·7 | (2·6-2·8) | 2·5 | (2·4-2·5) |

| Bipolar disorder | 6·3 | (5·7-6·8) | 6·2 | (5·7-6·7) | 2·5 | (2·3-2·6) | 2·8 | (2·6-2·9) |

| Any mood disorder | 24·5 | (23·5-25·4) | 37·9 | (37·0-38·8) | 2·6 | (2·5-2·7) | 2·5 | (2·4-2·5) |

| III. Substance use disorder | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse disorder | 21·6 | (20·6-22·7) | 7·2 | (6·7-7·7) | 1·6 | (1·5-1·6) | 2·2 | (2·1-2·3) |

| Alcohol dependence | 6·1 | (5·6-6·7) | 2·3 | (2·0-2·7) | 1·8 | (1·7-1·9) | 2·4 | (2·2-2·7) |

| Drug abuse disorder | 7·9 | (7·2-8·7) | 4·2 | (3·8-4·7) | 1·9 | (1·8-2·1) | 2·5 | (2·3-2·7) |

| Drug dependence | 3·0 | (2·4-3·5) | 1·6 | (1·4-1·9) | 2·1 | (1·8-2·3) | 2·5 | (2·3-2·8) |

| Any substance use disorder | 24·4 | (23·3-25·6) | 9·9 | (9·2-10·5) | 1·6 | (1·5-1·6) | 2·2 | (2·1-2·3) |

| IV. Externalizing disorders | ||||||||

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 3·0 | (2·4-3·6) | 1·8 | (1·4-2·2) | 1·3 | (1·1-1·4) | 1·2 | (1·1-1·4) |

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 5·9 | (5·2-6·5) | 5·2 | (4·7-5·8) | 1·7 | (1·6-1·8) | 2·1 | (1·9-2·2) |

| Any externalizing disorder | 6·8 | (6·0-7·5) | 5·6 | (5·0-6·2) | 1·6 | (1·5-1·7) | 1·8 | (1·7-1·9) |

| V. Any mental disorder | 46·4 | (44·9-47·8) | 53·1 | (51·9-54·3) | 1·6 | (1·6-1·7) | 1·8 | (1·8-1·8) |

Abbreviations: MR, morbid risk per 100 participants; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval of MR; MR/LP, ratio of MR to lifetime prevalence as of age 75.

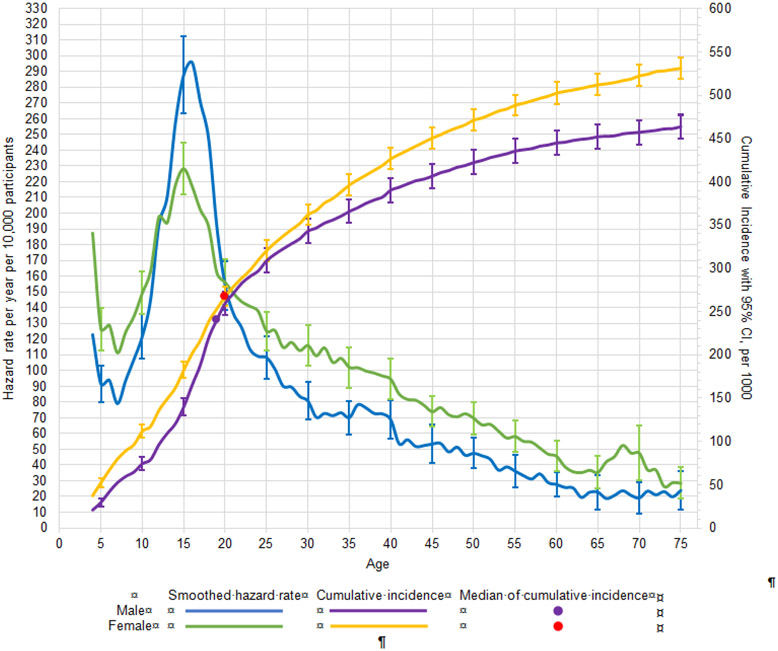

The minimum, maximum, median, and interquartile range (25 th and 75th percentiles of the AOO distribution) of cumulative lifetime risk as of age 75 are reported in Supplementary Table 1. Figure 1 shows smoothed (five-year bandwidth) incidence of first onset (number of cases per 10,000 people) of any disorder separately for males and females. Peak incidence was approximately at age 15, where males had higher incidence than females. However, across the rest of the lifespan, incidence was for the most part slightly higher among females than males. Cumulative risk curves (per 1,000 people) were higher across the lifespan for females than males. For any disorder, median AOO of first disorder was 19 for males and 20 females.

Figure 1. Smoothed hazard rate per year of age and cumulative incidence, with 95% confidence intervals by age and sex for any mental disordera.

a Left y-axis curves, with blue for males and green for females, are hazard rate (incidence rate) curves. These are calculated per year of age per 10,000 people, defined as a ratio of the number of disorder onsets at a given age among people who never had the disorder at any time up to that age and who lived through that age. For a given age t we used information only from respondents in the age range t to t + 10 to minimize the effects of recall bias. Right y-axis curves, with purple for males and yellow for females, are cumulative incidence (or morbid risk) curves. These are calculated based on the age-specific incidence rates at each year of life using the standard exponential formula.14

The MR/LP ratio also reflects the relatively high proportion of mental disorders that first occur in childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood (Table 3). Disorders with earlier onsets have MR/LP ratios closer to one, while disorders with a wider AOO distribution have MR/LP ratios greater than one. For males, the lowest MR/LP ratios were for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia (1·2-1·3), while the highest was for major depressive disorder (2·7). For females, the lowest MR/LP ratios were for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia (1·2-1·3), while the highest was for bipolar disorder (2·8).

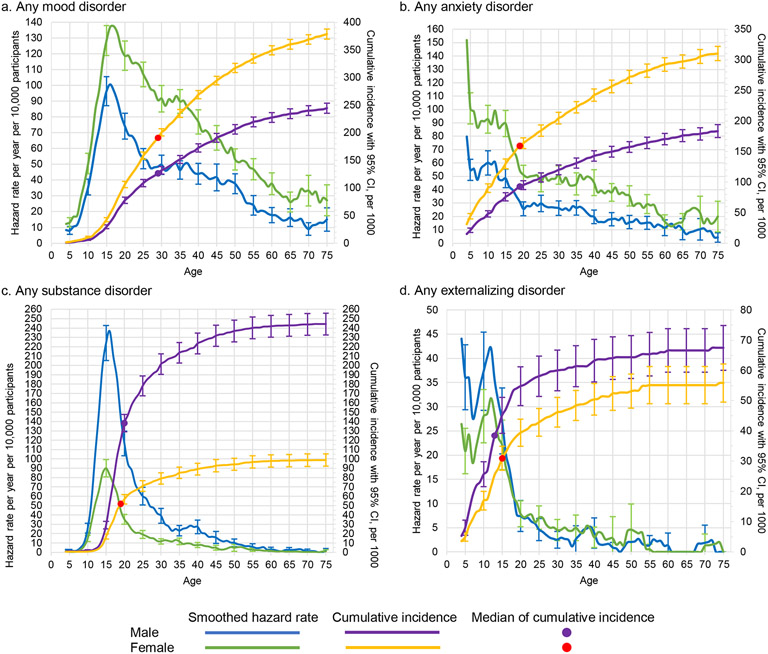

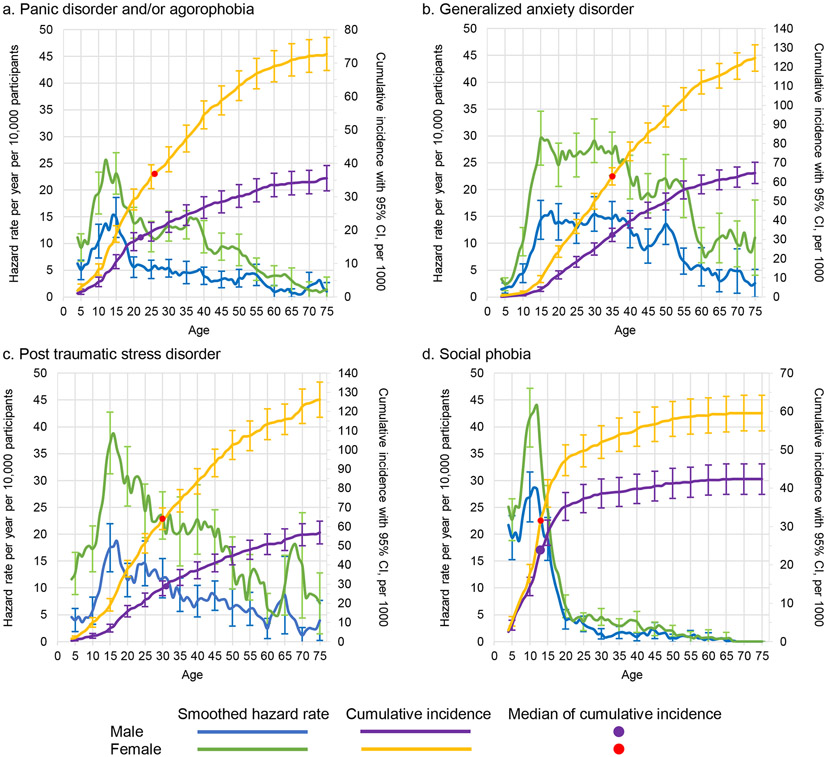

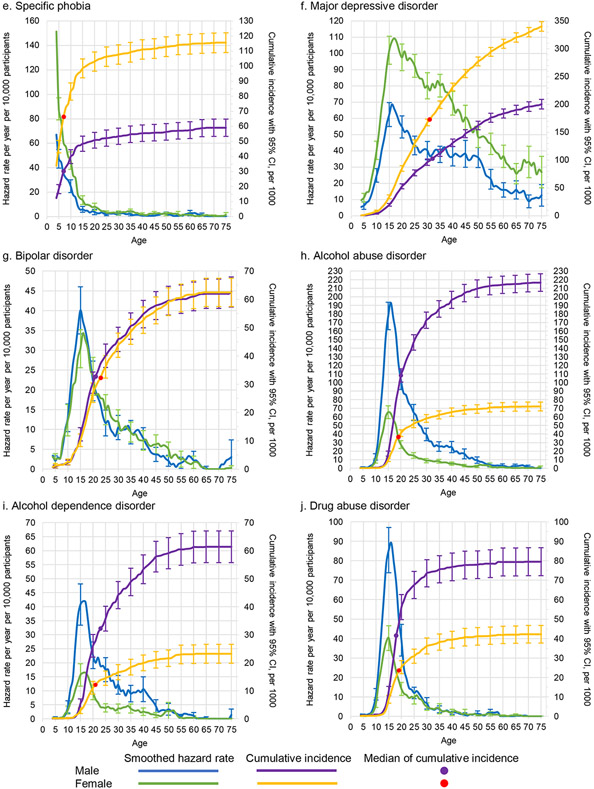

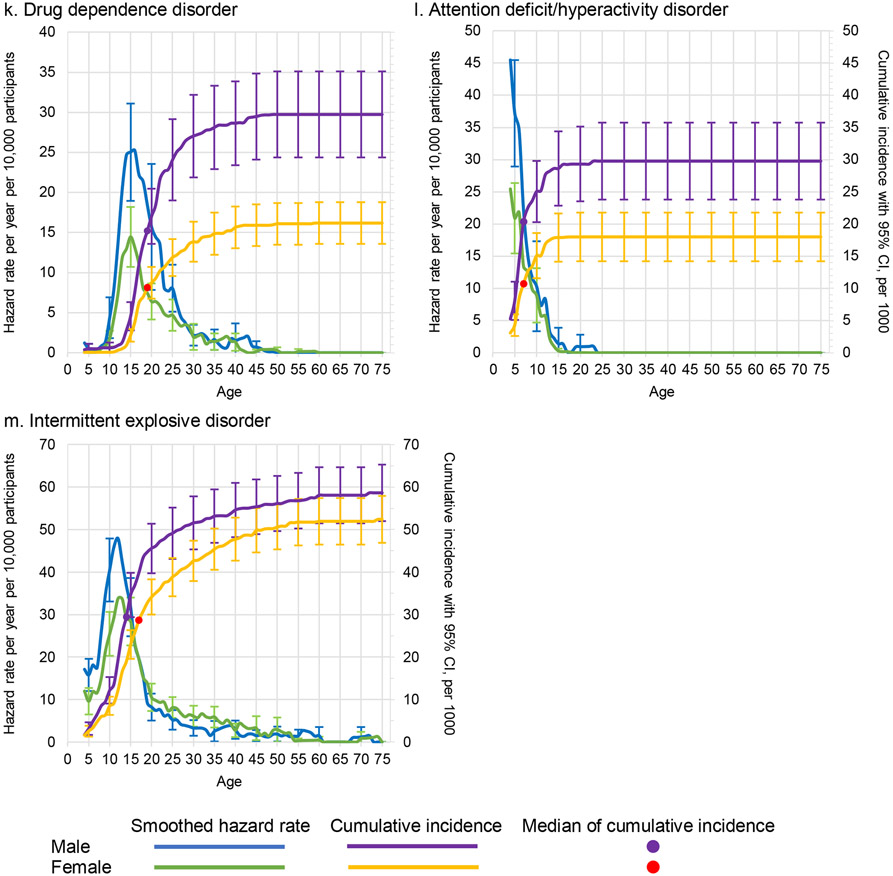

The distributions show distinct features when disaggregated by broad general categories (Figure 2) or specific disorder types (Figure 3). For example, any externalizing disorder shows an early peak incidence in the first decade of life, while incidence of substance use disorders peaks around age 15. Both types of disorder are more common among males than females. The two most common groups of disorders (mood and anxiety disorders) are more common among females than males across the lifespan, but the peak incidence of any anxiety disorder is at age 5 compared to age 15 for any mood disorder. Table 2 shows the Wald chi-square test comparing the lifetime prevalence for each specific disorder and broad general category. As expected, men and women differ significantly for each disorder, with mood and anxiety disorders significantly more common among females and substance and externalizing disorders more common among males.

Figure 2: Smoothed hazard rates and cumulative incidence, with 95% confidence intervals by age and sex for any mood disorder, any anxiety disorder, any substance use disorder, and any externalizing disordera.

a Left y-axis curves, with blue for males and green for females, are hazard rate (incidence rate) curves. These are calculated per year of age per 10,000 people, defined as a ratio of the number of disorder onsets at a given age among people who never had the disorder at any time up to that age and who lived through that age. For a given age t we used information only from respondents in the age range t to t + 10 to minimize the effects of recall bias. Right y-axis curves, with purple for males and yellow for females, are cumulative incidence (or morbid risk) curves. These are calculated based on the age-specific incidence rates at each year of life using the standard exponential formula.14

Figure 3. Smoothed Hazard Rate and cumulative incidence, with 95% confidence intervals by age and sex for thirteen specific disordersa.

a Left y-axis curves, with blue for males and green for females, are hazard rate (incidence rate) curves. These are calculated per year of age per 10,000 people, defined as a ratio of the number of disorder onsets at a given age among people who never had the disorder at any time up to that age and who lived through that age. For a given age t we used information only from respondents in the age range t to t + 10 to minimize the effects of recall bias. Right y-axis curves, with purple for males and yellow for females, are cumulative incidence (or morbid risk) curves. These are calculated based on the age-specific incidence rates at each year of life using the standard exponential formula.14

As noted at the onset, the WMH surveys were carried out over a wide range of years. To see if results differed depending on time of survey, we replicated all analyses for broad classes of disorders and any disorder separately for the 81,342 respondents in the 2007 paper and the 74,989 additional respondents in more recent surveys. Results reported in Supplementary Table 2 shows broad consistency in relative prevalence across disorders and in comparing males versus females. Supplementary Table 3 shows broad consistency in MR/LP ratios between the earlier and more recent surveys. Supplementary Figures 1-2 show broad consistency in AOO distributions between the earlier and more recent surveys.

DISCUSSION

Based on surveys with 156,331 respondents from 29 countries, we reported estimates of AOO distributions, lifetime prevalence, and morbid risk for 13 mental disorders. We estimated that by age 75, about one in two individuals will develop at least one of the mental disorders considered here. We found the same female excess of anxiety and mood disorders and male excess of substance use and externalizing disorders as in other epidemiological surveys. Importantly, though, our findings, based as they are on more accurate estimates of AOO distributions than previous studies, confirm that many mental disorders have their first onsets during childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood and that some disorders have notably earlier ages of onset than others. The current report extended the WMH findings reported in 2007 to close to twice as large a sample and included surveys from 29 countries compared to 17 in the earlier report.

Given that most major studies of AOO distributions in recent years have been based on register-based studies of treated mental disorders,20 it is noteworthy that both commonalities and differences can be seen between those studies and the population-based results reported here. First, as expected, the lifetime morbid risk of any treated mental disorders based on registers is lower than the estimates found in population-based surveys. This is because epidemiological studies show that many people with mental disorders never receive treatment.21 Second, because of the well-documented delays in seeking treatment after the first onset of mental disorders,22 the AOO distributions for register-based studies tend to be right-shifted (ie, delayed) compared to population-based studies. This bias is sex-dependent, as females are more likely than males to seek treatment and to do so more quickly.23

A key finding is the substantial proportion of mental disorders that have early first onsets. Strikingly, we found that half of those who develop a mental disorder before age 75 have their first onset by ages 19-20 (males and females). In addition to the traditional childhood onset disorders (eg, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, social and specific phobia), common mental disorder such as major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and drug use disorders were found often to have their first onsets in childhood through early adulthood. This observation lends weight to the need to invest in mental health services that have a particular focus on young people.24 While the median AOO for many disorders in males and females were comparable, our findings confirm significant sex differences in lifetime prevalence for each of the mental disorders examined, with anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder more common among females compared to impulse control and substance use disorders more common among males. These differences are consistent with previous studies.25

Limitations

While the current study has several major strengths (eg, cross-national, harmonized protocols, use of bounded recall and restricted recall period to reduce recall bias), it also has important limitations. First, surveys were carried out over a range of more than two decades, although there was good consistency of results. Second, all data were based on retrospective reports. Recall bias increases with length of recall, and can lead to under-identification of more temporally distant events,7 as illustrated in birth cohort studies.6 We based our estimates on onsets within ten years of interview to minimize this bias. Third, our definition of disorder onset was based on single questions rather than detailed diagnostic assessments for first recalled occurrence, leading to possible downwardly biased AOO estimates. Fourth, the surveys could have been biased due to differential response. Fifth, although the sample was large enough to generate relatively precise pooled disorder-specific estimates, it was not large enough to investigate between-country differences. Sixth, not all mental disorders were included in the CIDI. Seventh, we did not consider comorbidity. There is a growing appreciation that comorbidity is common within different types of mental disorders—individuals with one type of mental disorder are at increased risk of subsequently developing other types of mental disorders26-28 – and that burden of illness in strongly influenced by comorbidity. While the current study provided lifetime estimates for any mental disorder and for specific types of disorder, we did not consider patterns of comorbidity and how that change over the life course.27 We hope to explore this issue in future studies.

In summary, our study reconfirmed the fact that mental disorders are common across the lifespan. We provided updated estimates of AOO distributions, lifetime prevalence, and morbid risk for a range of mental disorders using improved methods to reduce the effects of recall bias. These estimates will be of value to service planners as well as researchers interested in the burden of disease5,29 and genetic epidemiology.3,4

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Age-of-onset (AOO), lifetime prevalence, and lifetime morbid risk of mental disorders are key estimates required for service planning on frequency of disorders when in the life course disorders first emerge. Previous studies of these estimates often relied on suboptimal samples (eg, case-only samples, treated patients via registers). Few studies presented both AOO and lifetime prevalence for diverse mental disorders based on population-based data from multiple countries. We searched PubMed with the search terms: (["age of onset"[TIAB] OR "lifetime prevalence"[TIAB] OR "morbid risk"[TIAB] OR "cumulative incidence" [TIAB]) AND (mental[TIAB] OR psychiatri*[TIAB]) for articles in any language published between January 1, 1966 and June 30, 2022. We identified 4050 articles (including 93 systematic reviews). Most studies focused on one type of mental disorder in one country. A systematic review of AOO summarized data from 192 studies but did not examine lifetime prevalence. With respect to cross-national studies, one 2007 study reported country-specific AOO, lifetime prevalence, and morbid risk for 17 countries, but cross-national and sex-specific estimates were not presented.

Added value of this study

We present data from 32 coordinated community epidemiological surveys in 29 countries (12 low- and middle-income countries; 17 high-income countries) including 156,331 adult (ages 18+) survey respondents on thirteen types of DSM-IV/DSM-5 mental disorders. These included 16 of the 17 surveys in the 2007 report noted above (the exceptions being a survey no longer available from mainland China) with a combined sample of 81,342 respondents plus 74,989 respondents from 16 more recent surveys from some of the same and 13 additional countries. We present sex-specific cross-national estimates of AOO distributions, including median AOO, lifetime prevalence, and morbid risk up through age 75 for 13 types of mental disorders. Lifetime prevalence for any mental disorder was 28·6% for males and 29·8% for females. Morbid risk by age 75 was 46·4% for males and 53·1% for females. Conditional probabilities of first onset peaked at age 15, with median age-of-onset of 19 for males and 20 for females. The results are displayed graphically in an interactive data visualization website.

Implications of all the available evidence

Mental disorders are common: by age 75. Many disorders have first onsets in childhood through young adulthood. Given these findings, health planners need to ensure sufficient services to reach out and treat mental disorders among young people.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding

Financial and technical support for core activities of the World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative over the years of its existence came from the World Health Organization, the United States National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R01 MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the United States Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis.

The 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The Argentina survey – Estudio Argentino de Epidemiología en Salud Mental (EASM) – was supported by a grant from the Argentinian Ministry of Health (Ministerio de Salud de la Nación) – (Grant Number 2002-17270/13-5). The São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey is supported by the State of São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) Thematic Project Grant 03/00204-3. The Bulgarian Epidemiological Study of common mental disorders EPIBUL is supported by the Ministry of Health and the National Center for Public Health Protection. EPIBUL 2, conducted in 2016-17, is supported by the Ministry of Health and European Economic Area Grants. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection. The Mental Health Study Medellín – Colombia was carried out and supported jointly by the Center for Excellence on Research in Mental Health (CES University) and the Secretary of Health of Medellín. The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123, and EAHC 20081308), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Generalitat de Catalunya (2017 SGR 452; 2014 SGR 748), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CIBER CB06/02/0046, RETICS RD06/0011 REM-TAP), and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. Implementation of the Iraq Mental Health Survey (IMHS) and data entry were carried out by the staff of the Iraqi MOH and MOP with direct support from the Iraqi IMHS team with funding from both the Japanese and European Funds through United Nations Development Group Iraq Trust Fund (UNDG ITF). The Israel National Health Survey is funded by the Ministry of Health with support from the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research and the National Insurance Institute of Israel. The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013, H25-SEISHIN-IPPAN-006) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Lebanese Evaluation of the Burden of Ailments and Needs of the Nation (L.E.B.A.N.O.N.) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), National Institute of Health / Fogarty International Center (R03 TW006481-01), anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from, Algorithm, AstraZeneca, Benta, Bella Pharma, Eli Lilly, Glaxo Smith Kline, Lundbeck, Novartis, OmniPharma, Pfizer, Phenicia, Servier, UPO. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544- H), with supplemental support from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) is supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council, and the Health Research Council. The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) is supported by the WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria), and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. The Northern Ireland Study of Mental Health was funded by the Health & Social Care Research & Development Division of the Public Health Agency. The Peruvian World Mental Health Study was funded by the National Institute of Health of the Ministry of Health of Peru. The Polish project Epidemiology of Mental Health and Access to Care – EZOP Project (PL 0256) was carried out by the Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology in Warsaw in consortium with Department of Psychiatry - Medical University in Wroclaw and National Institute of Public Health-National Institute of Hygiene in Warsaw and in partnership with Psykiatrist Institut Vinderen – Universitet, Oslo. The project was funded by the European Economic Area Financial Mechanism and the Norwegian Financial Mechanism. EZOP project was co-financed by the Polish Ministry of Health. The Portuguese Mental Health Study was carried out by the Department of Mental Health, Faculty of Medical Sciences, NOVA University of Lisbon, with collaboration of the Portuguese Catholic University, and was funded by Champalimaud Foundation, Gulbenkian Foundation, Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and Ministry of Health. The World Mental Health Qatar Study was conducted by the Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI) at Qatar University (QU) and Hamad Medical Corporation. This study was funded by Hamad Medical Corporation through Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, UK. The Romania WMH study projects "Policies in Mental Health Area" and "National Study regarding Mental Health and Services Use" were carried out by National School of Public Health & Health Services Management (former National Institute for Research & Development in Health), with technical support of Metro Media Transilvania, the National Institute of Statistics-National Centre for Training in Statistics, SC Cheyenne Services SRL, Statistics Netherlands and were funded by Ministry of Public Health (former Ministry of Health) with supplemental support of Eli Lilly Romania SRL. The Saudi National Mental Health Survey (SNMHS) is conducted by the King Salman Center for Disability Research. It is funded by Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC), King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia), and King Saud University. Funding in-kind was provided by King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, and the Ministry of Economy and Planning, General Authority for Statistics. The South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH) is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. The Shenzhen Mental Health Survey is supported by the Shenzhen Bureau of Health and the Shenzhen Bureau of Science, Technology, and Information. The Psychiatric Enquiry to General Population in Southeast Spain – Murcia (PEGASUS-Murcia) Project has been financed by the Regional Health Authorities of Murcia (Servicio Murciano de Salud and Consejería de Sanidad y Política Social) and Fundación para la Formación e Investigacion Sanitarias (FFIS) of Murcia. The Ukraine Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption (CMDPSD) study is funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH61905). The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust.

Dr. Laura Helena Andrade is supported by the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq Grant # 307933/2019-9).

Dr. Dan Stein is supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa (MRC).

A complete list of all within-country and cross-national WMH publications can be found at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/.

Appendix

WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators: Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, Ali Al-Hamzawi, Jordi Alonso, Yasmin A Altwaijri, Laura Helena Andrade, Lukoye Atwoli, Corina Benjet, Evelyn J Bromet, Ronny Bruffaerts, Brendan Bunting, José Miguel Caldas-de-Almeida, Graça Cardoso, Stephanie Chardoul, Alfredo H Cía, Louisa Degenhardt, Giovanni De Girolamo, Oye Gureje, Josep Maria Haro, Meredith G Harris, Hristo Hinkov, Chi-Yi Hu, Peter De Jonge, Aimee N Karam, Elie G Karam, Georges Karam, Alan E Kazdin, Norito Kawakami, Ronald C Kessler, Andrzej Kiejna, Viviane Kovess-Masfety, John J McGrath, Maria Elena Medina-Mora, Jacek Moskalewicz, Fernando Navarro-Mateu, Daisuke Nishi, Marina Piazza, José Posada-Villa, Kate M Scott, Juan Carlos Stagnaro, Dan J Stein, Margreet Ten Have, Yolanda Torres, Maria Carmen Viana, Daniel V Vigo, Cristian Vladescu, David R Williams, Peter Woodruff, Bogdan Wojtyniak, Miguel Xavier, Alan M Zaslavsky

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

LD reports untied educational grants from Indivior and Seqirus for the study of new opioid medications in Australia.

OVD reports funding from KOWA Research Institute and has participated in the PROMINENT trial in an advisory capacity.

SMK and PWW report grant funding from Hamad Medical Corporation (Qatar) through Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation trust (UK) and from Qatar University. PWW received support from the Qatar National Research Fund and an honorarium from Gresham College, UK.

In the past 3 years, RCK was a consultant for Cambridge Health Alliance, Canandaigua VA Medical Center, Holmusk, Partners Healthcare, Inc., RallyPoint Networks, Inc., and Sage Therapeutics. He has stock options in Cerebral Inc., Mirah, PYM, Roga Sciences and Verisense Health.

DN reports honoraria from AIG General Insurance Company, Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd., and other support from Startia, Inc., En-power, Inc., and MD.net.

DJS reports royalties from American Psychiatric Press, Cambridge University Press and Elsevier/Academic Press. He has received honoraria from Discovery Vitality, Johnson & Johnson, Kanna, L’Oreal, Lundbeck, Orion, Sanofi, Servier, Takeda, and Vistagen. He is a past president of the African College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

All other authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

John J. McGrath, Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research, Brisbane, Australia Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia National Centre for Register-based Research, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

Ali Al-Hamzawi, College of Medicine, University of Al-Qadisiya, Diwaniya Governorate, Iraq.

Jordi Alonso, Health Services Research Unit, IMIM-Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute, Barcelona, Spain, Department of Medicine and Life Sciences, Pompeu Fabra University (UPF), Barcelona, Spain CIBER en Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain.

Yasmin Altwaijri, Epidemiology Section, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Laura H. Andrade, Section of Psychiatric Epidemiology - LIM 23, Institute of Psychiatry, University of São Paulo Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil.

Evelyn J. Bromet, Department of Psychiatry, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Stony Brook, New York, USA.

Ronny Bruffaerts, Universitair Psychiatrisch Centrum - Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (UPC-KUL), Campus Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium.

José Miguel Caldas de Almeida, Lisbon Institute of Global Mental Health and Chronic Diseases Research Center (CEDOC), NOVA Medical School ∣ Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal.

Stephanie Chardoul, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Wai Tat Chiu, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Louisa Degenhardt, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Olga V. Demler, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. USA, Department of Computer Science, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

Finola Ferry, School of Psychology, Ulster University, Belfast, United Kingdom.

Oye Gureje, Department of Psychiatry, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Josep Maria Haro, Research, Teaching and Innovation Unit, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain, Centre for Biomedical Research on Mental Health (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain Departament de Medicine, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Elie G. Karam, Department of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, St George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon, Faculty of Medicine, University of Balamand, Beirut, Lebanon, Institute for Development, Research, Advocacy and Applied Care (IDRAAC), Beirut, Lebanon.

Georges Karam, Department of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, St George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon, Faculty of Medicine, University of Balamand, Beirut, Lebanon, Institute for Development, Research, Advocacy and Applied Care (IDRAAC), Beirut, Lebanon.

Salma M. Khaled, Social and Economic Survey Research Institute, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

Viviane Kovess-Masfety, Institut de Psychologie, Université Paris Cité, Paris, France.

Marta Magno, Unit of Epidemiological and Evaluation Psychiatry, IRCCS Istituto Centro San Giovanni di Dio Fatebenefratelli, Brescia, Italy.

Maria Elena Medina-Mora, National Institute of Psychiatry Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, Mexico City, Mexico.

Jacek Moskalewicz, Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, Warsaw, Poland.

Fernando Navarro-Mateu, Unidad de Docencia, Investigación y Formación en Salud Mental (UDIF-SM), Gerencia Salud Mental, Servicio Murciano de Salud, Murcia, Spain, Murcia Biomedical Research Institute (IMIB-Arrixaca), Murcia, Spain, CIBER Epidemiology and Public Health-Murcia (CIBERESP-Murcia), Murcia, Spain.

Daisuke Nishi, Department of Mental Health, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan.

Oleguer Plana-Ripoll, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University and Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus N 8200, Denmark, National Centre for Register-based Research, Aarhus University, Aarhus V 8000, Denmark.

José Posada-Villa, Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca University, Faculty of Social Sciences, Bogota, Colombia.

Charlene Rapsey, Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand.

Nancy A. Sampson, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Juan Carlos Stagnaro, Departamento de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Dan J. Stein, Department of Psychiatry & Mental Health and South African Medical Council Research Unit on Risk and Resilience in Mental Disorders, University of Cape Town and Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, Republic of South Africa.

Margreet ten Have, Trimbos-Instituut, Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction, Utrecht, Netherlands.

Yolanda Torres, Center for Excellence on Research in Mental Health, CES University, Medellin, Colombia.

Cristian Vladescu, National Institute for Health Services Management, Bucharest, Romania.

Peter W. Woodruff, Department Neuroscience, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK.

Zahari Zarkov, Department of Mental Health, National Center of Public Health and Analyses, Sofia, Bulgaria.

Ronald C. Kessler, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Data sharing statement

Access to the cross-national World Mental Health (WMH) data is governed by the organizations funding and responsible for survey data collection in each country. These organizations made data available to the WMH survey consortium through restricted data sharing agreements that do not allow data to be released to third parties. The exception is that the U.S. data are available for secondary analysis via the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/00527.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey initiative. World Psychiatry 2007; 6: 168–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry 2022; 27: 281–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Family genetic risk scores and the genetic architecture of major affective and psychotic disorders in a Swedish national sample. JAMA Psychiatry 2021; 78: 735–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedersen EM, Agerbo E, Plana-Ripoll O, et al. Accounting for age of onset and family history improves power in genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet 2022; 109: 417–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray CJL, Lopez AD, editors. The global burden of disease: A comprehensive assessment of morality and disability from diseases, injuries, risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Published by the Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank, Distributed by Harvard Unviersity Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, et al. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol Med 2010; 40: 899–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knäuper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving accuracy of major depression age-of-onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1999; 8: 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton WW, Kessler RC, Mortensen PB, Rebok GW, Roth K. The population dynamics of mental disorders. In: Eaton WW, Fallin MD, eds. Public Mental Health. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2019: 124–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Pennell BE, Zaslavsky AM. Methods of the World Mental Health surveys. In: Bromet EJ, Karam EG, Koenen KC, Stein DJ, eds. Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Global Perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2018: 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Pennell B, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. Methods of the World Mental Health surveys. In: Scott KM, de Jonge P, Stein DJ, Kessler RC, eds. Mental Disorders Around the World: Facts and Figures from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2018: 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB, eds. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011: 58–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pennell BE, Mneimneh ZN, Bowers A, et al. Implementation of the World Mental Health surveys. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB, eds. The WHO World Mental Health Survey: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008: 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, et al. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2006; 15: 167–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liptser RS, Shiryaev AN. Statistics of Random Processes II: Applications. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. (Stochastic Modelling and Applied Probability, vol 6). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. 1st ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conner SC, Beiser A, Benjamin EJ, LaValley MP, Larson MG, Trinquart L. A comparison of statistical methods to predict the residual lifetime risk. Eur J Epidemiol 2022; 37: 173–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 334–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haapea M, Miettunen J, Laara E, et al. Non-participation in a field survey with respect to psychiatric disorders. Scand J Public Health 2008; 36: 728–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS Institute Inc. SAS® 9.4 Global Statements: Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plana-Ripoll O, Momen NC, McGrath JJ, et al. Temporal changes in sex- and age-specific incidence profiles of mental disorders: A nationwide study from 1970 to 2016. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2022; 145: 604–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang PS, Sergio A-G, AlHamzawi AO, et al. Treated and untreated prevalence of mental disorders: Results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. In: Thornicroft G, Szmukler G, Mueser KT, Drake RE, eds. Oxford Textbook of Community Mental Health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2011: 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, et al. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health survey initiative. World Psychiatry 2007; 6: 177–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Brown RL, Broman CL. Sex differences in psychiatric help-seeking: Evidence from four large-scale surveys. J Health Soc Behav 1981; 22: 49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGorry PD, Purcell R, Hickie IB, Jorm AF. Investing in youth mental health is a best buy. Med J Aust 2007; 187: S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riecher-Rossler A. Sex and gender differences in mental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2017; 4: 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGrath JJ, Lim CCW, Plana-Ripoll O, et al. Comorbidity within mental disorders: A comprehensive analysis based on 145,990 survey respondents from 27 countries. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2020; 29: e153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plana-Ripoll O, Musliner KL, Dalsgaard S, et al. Nature and prevalence of combinations of mental disorders and their association with excess mortality in a population-based cohort study. World Psychiatry 2020; 19: 339–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Holtz Y, et al. Exploring comorbidity within mental disorders among a Danish national population. JAMA Psychiatry 2019; 76: 259–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weye N, Santomauro DF, Agerbo E, et al. Register-based metrics of years lived with disability associated with mental and substance use disorders: A register-based cohort study in Denmark. Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8: 310–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Access to the cross-national World Mental Health (WMH) data is governed by the organizations funding and responsible for survey data collection in each country. These organizations made data available to the WMH survey consortium through restricted data sharing agreements that do not allow data to be released to third parties. The exception is that the U.S. data are available for secondary analysis via the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/00527.