Abstract

Objective(s):

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted older people, people with underlying health conditions, racial and ethnic minorities, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and people living with HIV (PWH). We sought to describe vaccine hesitancy and associated factors, reasons for vaccine hesitancy, and vaccine uptake over time in PWH in Washington, DC.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional survey between October 2020 and December 2021 among PWH enrolled in a prospective longitudinal cohort in DC. Survey data were linked to electronic health record data and descriptively analyzed. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with vaccine hesitancy. The most common reasons for vaccine hesitancy and uptake were assessed.

Results:

Among 1,029 participants (66% men, 74% Black, median age 54), 13% were vaccine hesitant and 9% refused. Females were 2.6 to 3.5 times, non-Hispanic Blacks were 2.2 times, Hispanics, and those of other race/ethnicities were 3.5 to 8.8 times and younger PWH were significantly more likely to express hesitancy or refusal than males, non-Hispanic Whites and older PWH, respectively. The most reported reasons for vaccine hesitancy were side effect concerns (76%), plans to use other precautions/masks (73%), and speed of vaccine development (70%). Vaccine hesitancy and refusal declined over time (33% in October 2020 vs. 4% in December 2021, p<0.0001).

Conclusions:

This study is one of the largest analyses of vaccine hesitancy among PWH in a US urban area highly impacted by HIV and COVID-19. Multi-level culturally appropriate approaches are needed to effectively address COVID-19 vaccine concerns raised among PWH.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in over 100 million infections, and over 1 million deaths in the United States (US) with ongoing transmission and deaths as of March 2023. 1 The pandemic has disproportionately impacted people with underlying health conditions, 2–4 racial and ethnic minority people5–7 and the socioeconomically disadvantaged. 7–9 The increased risk for COVID-19 and severe outcomes among PWH compared to the general population has been mixed to date. 10–13Nevertheless, compared to people not living with HIV, PWH in the US tend to be older, 14 racial and ethnic minority people, 14 and more vulnerable to COVID-19 due to disparities in socioeconomic status, myriad other social determinants of health and structural racism, among other factors. 15

COVID-19 vaccines were developed at record pace and were initially distributed in a tiered manner. Per the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), PWH were included in Phase 1c of vaccination rollout for the primary vaccination series given their immunosuppression, 16 yet data on the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines among PWH was not studied specifically, which may have affected vaccine uptake among PWH. Nonetheless, the CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services and the Infectious Diseases Society of America all recommended vaccination and subsequently boosters for PWH.17–19

Given the disparities in infection rates, historical and ongoing mistrust of the medical community among communities of color, 20–22 and the lack of reported clinical trial data specifically for PWH, 23–25 there has been ambivalence regarding vaccination among PWH and particularly among PWH racial and ethnic minority people. Prior research has shown that vaccine hesitancy among PWH is relatively common and often associated with racial and ethnic minority people, gender, age, stigma, structural racism. 20,26–30 A national survey among 1,030 PWH found that more than 90% had some degree of vaccine hesitancy. 26 Vaccine hesitancy has also been associated with medical or government mistrust.20,26 Bogart et al found high rates of medical mistrust among Black PWH with 97% of participants endorsing at least one mistrust belief. 20 Medical mistrust, or “lack of trust or suspicion of medical organizations” has been found to play a significant role in healthcare seeking behaviors among racial and ethnic people both with and without HIV. 31,32 Medical mistrust among people of color has been linked to government actions such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, as well as conspiracy theories and misinformation targeting minority people. 31,33,34 The combination of medical and government mistrust can limit racial and ethnic peoples’ willingness to participate in medical care and may therefore impact vaccine uptake. 34,35

Greater vaccine hesitancy has also been observed among PWH who have concerns about the rapidity of vaccine development, side effects, and the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine. 20,28,29 Despite these findings, much of the published literature has focused on likelihood or intent to vaccinate, has included limited numbers of minority PWH and has collected data over short periods of time (e.g., one to four months) often prior to actual COVID-19 vaccine availability.

In Washington, DC approximately 12,400 people are living with HIV, of whom an estimated 72% and 8% are Black and Hispanic people, respectively.36 Like the HIV epidemic, a disproportionately higher rate of COVID-19 cases has been reported among DC’s Black and Hispanic residents.37 Vaccination rollout in DC began in mid-December 2020, 38 and became more widely available as of mid-April 2021, when all residents ages 16 and older were eligible for vaccination.39 As of December 2022, an estimated 60% of DC residents had completed their primary vaccine series, with coverage among Black people at 49% and Hispanic people at 70%.37 Given the availability of COVID-19 vaccines and boosters yet continued lags in uptake, this analysis sought to describe vaccine hesitancy and associated factors, barriers to vaccination, and trends in vaccine uptake among a cohort of predominantly Black PWH enrolled in a longitudinal HIV study in Washington, DC.

Methods

We conducted a COVID-19 cross-sectional survey among participants enrolled in the DC Cohort, a prospective longitudinal cohort of PWH receiving outpatient care at 14 clinical sites in DC.40 Eligible participants included those actively enrolled in the study who were 18 or older, able to provide consent and complete the survey in English or Spanish. Potential participants were contacted by a study team member who briefly explained the study objectives. If participants agreed, they were sent a REDCap survey link through which they provided electronic informed consent and completed the survey.41 Participants were remunerated with a $25 gift card for survey completion.

All survey data were linked to the DC Cohort study database to gather additional data including age, date of HIV diagnosis, mode of HIV transmission, and most recent CD4 count and HIV RNA results since January 2020. Participants included in this analysis completed the survey between October 30, 2020, and December 31, 2021. All study procedures were approved by the site’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) or the GWU IRB, which serves as the IRB of record for most sites.

The survey was designed to include survey questions that had been used in previous COVID-19 surveys as well as to reflect the emerging national and local response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey included questions including, but not limited to, demographics; pre-existing medical conditions (i.e., those known at the time to result in more severe disease); the impact of COVID on income, housing, mental and substance use; impacts on access to medical care, including HIV care; prior vaccination history (e.g., influenza); and COVID-related experiences regarding symptoms, testing, close contacts and stigma; COVID vaccination (primary series vaccination), intent to vaccinate and barriers to vaccination. 42–46 The primary outcome, participants’ vaccine hesitancy, was defined based on their answer to the question ‘Would you get a vaccine for COVID-19 if it was available today?’. 42 Responses were classified into three groups: 1) “vaccine hesitant”: responded ‘don’t know’ to the question; 2) “vaccine refusal”: responded “no” to the question; and 3) “not vaccine hesitant”: responded ‘yes’ to the question ‘Have you received a COVID-19 vaccine?’ or ‘yes’ to the question ‘Would you get a vaccine for COVID-19 if it was available today?’. Participants who responded ‘yes’ to the question ‘Have you received a COVID-19 vaccine?’ were not asked whether they would get a vaccine if available. The question ‘Would you get a vaccine for COVID-19 if it was available today?’ was asked of participants both before and after vaccines were widely available. Potential barriers to vaccination were asked of participants who were not vaccinated and responded ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’ to getting a vaccine if it were available. Response options for the barrier question were added in January 2021 and further expanded in March 2021 based on an updated review of the data on vaccine hesitancy.45,46 Reasons for hesitancy included topics such as individual beliefs regarding COVID-19 (e.g., ‘don’t think I need it’), protective behaviors (e.g., ‘plan to use masks’, government mistrust (e.g., ‘don’t trust the government’), and uncertainties around the vaccines (vaccine could give me COVID, concerns about side effects).

Given the long follow up period for data collection (e.g., 15-months), the emerging knowledgebase regarding COVID-19, the evolving public health response, and the vaccination and booster rollout (i.e., primary series, followed by multiple boosters), we stratified our data collection period to reflect key time points with respect to vaccine availability. Timing of vaccine availability was stratified into three time periods based on national and local vaccine rollout and guidance: pre-early vaccine period (October 2020-March 2021); the general vaccination period (April-October 2021); and the booster period (November-December 2021).38,39,47 The pre-early vaccination period included the initial EUA approval of the Pfizer, Moderna and J&J vaccines, and the period when essential workers, those 65 years of age and older, those with chronic medical conditions, including HIV, and healthcare workers were authorized for vaccination in Washington, DC. The general vaccination period included when vaccines were made available to the general public in DC, and when boosters were approved for immunocompromised persons by the US Food and Drug Administration, and the CDC. The booster period included the period when boosters were authorized for all adults.

We examined differences between those who were hesitant and those who were not or had been vaccinated with respect to demographics, COVID-19 exposures, employment, housing status, co-morbidities, timing of vaccine availability, and other factors using Chi-square tests for categorical and Wilcoxon Rank Sum for continuous variables. We employed multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with vaccine hesitancy and refusal. Factors associated with hesitancy were assessed in unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models after controlling for the DC Cohort clinical site type (i.e., hospital vs. community clinic), date of survey completion (i.e., pre/early vs. general vaccination/booster periods), and a priori variables of age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and employment. We also conducted additional stratified multivariable analyses to determine if factors associated differed with each time period (i.e., the pre-early vaccination period and the combined general and booster periods) (See Supplemental Tables). Finally, we described the most reported reasons for vaccine hesitancy and vaccine uptake among a subset of participants enrolled after the vaccine became available locally. All analysis was conducted in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Between October 30, 2020, and December 31, 2021, 2,539 DC Cohort participants were approached of which 1,029 completed the COVID-19 survey and provided data on vaccine hesitancy (41% response rate). The median age was 54 years, 66% were male, 74% were non-Hispanic Black people, and 77% were DC residents (Table 1). A majority (61%) of participants had completed some college, 55% were employed full or part-time, and 31% were considered essential workers, defined as working in construction, food service, delivery service, grocery stores, healthcare, hospitality, manufacturing, or transportation. Clinically, the median duration of HIV diagnosis was 16 years, 92% had an HIV RNA <200 copies/ml, and 96% had a CD4 cell count >=200 cells/μL. The majority (79%) of participants self-reported at least one underlying medical condition that would put them at greater risk for severe COVID-19 infection with hypertension (44%), smoking (37%) and overweight/obesity (21%) being the most reported.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of DC Cohort COVID-19 Survey Participants by Vaccine Hesitancy Status (N=1,029)

| Hesitant1 (n=131) | Refused3 (n=97) |

Vaccinated/Not Hesitant2 (n=801) |

Total4 | P-value5,6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | N (%) | ||

| Characteristic | 131 (12.7) | 97 (9.4) | 801 (77.8) | 1,029 | |

| Sociodemographics | |||||

| Age (median, IQR) | 50 (38,58) | 47 (37,57) | 55 (45,62) | 54 (43,61) | <.0001 6 |

| Gender Identity | <.0001 6 | ||||

| Male | 64 (49.6) | 41 (42.3) | 569 (71.1) | 674 (65.8) | |

| Female | 58 (45.0) | 54 (55.7) | 218 (27.3) | 330 (32.2) | |

| Transgender/Gender Nonbinary | 7 (5.4) | 2 (2.1) | 11 (1.4) | 20 (2.0) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | <.0001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 110 (84.0) | 86 (88.7) | 566 (70.7) | 762 (74.1) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 6 (4.6) | 1 (1.0) | 128 (16.0) | 135 (13.1) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (3.1) | 2 (2.1) | 48 (6.0) | 54 (5.3) | |

| Other7 | 8 (6.1) | 4 (4.1) | 40 (5.0) | 52 (5.1) | |

| Declined to answer | 3 (2.3) | 4 (4.1) | 19 (2.4) | 26 (2.5) | |

| Education | 0.0021 | ||||

| Less than high school education | 14 (10.9) | 10 (10.6) | 72 (9.1) | 96 (9.5) | |

| HS graduate | 50 (38.8) | 38 (40.4) | 209 (26.4) | 297 (29.3) | |

| At least some college | 65 (50.4) | 46 (48.9) | 510 (64.5) | 621 (61.2) | |

| Work status (as of 1/1/20) | 0.0076 | ||||

| Employed full- or part-time as essential employee | 33 (25.2) | 40 (41.24) | 245 (30.6) | 318 (30.9) | |

| Employed full- or part-time as non-essential employee | 32 (24.4) | 16 (16.49) | 197 (25.0) | 245 (23.8) | |

| Unemployed | 31 (23.7) | 20 (20.6) | 114 (14.2) | 165 (16.0) | |

| Other8 | 35 (26.7) | 21 (21.7) | 245 (30.6) | 301 (29.3) | |

| Essential worker9 (n=330) | 0.0460 | ||||

| Yes | 33 (55.9) | 40 (75.5) | 245 (58.3) | 214 (40.2) | |

| No | 26 (44.1) | 13 (24.5) | 175 (41.7) | 318 (59.8) | |

| Household composition | 0.4074 | ||||

| Lives alone | 54 (41.5) | 35 (36.5) | 347 (43.5) | 436 (42.6) | |

| Lives with others | 76 (58.5) | 61(63.5) | 451 (56.5) | 588 (57.4) | |

| Housing status | <.0001 6 | ||||

| Rent | 81 (61.8) | 69 (71.1) | 453 (56.6) | 603 (58.6) | |

| Own | 20 (15.3) | 8 (8.3 | 216 (27.0) | 244 (23.7) | |

| Homeless | 2 (1.5) | 3 (3.1) | 5 (0.6) | 10 (1.0) | |

| Other10 | 28 (21.4) | 17 (17.5) | 127 (15.9) | 172 (16.7) | |

| Location of residence | 0.0516 | ||||

| DC | 106 (82.8) | 78 (82.1) | 592 (75.0) | 776 (76.7) | |

| MD | 20 (15.6) | 16 (16.8) | 151 (19.1) | 187 (18.5) | |

| VA | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.1) | 46 (5.8) | 49 (4.8) | |

| Type of care site | |||||

| Community-based clinic | 87 (66.4) | 66 (69.5) | 506 (64.2) | 659 (65.0) | 0.5586 |

| Hospital-based clinic | 44 (33.6) | 29 (30.5) | 282 (35.8) | 355 (35.0) | |

| HIV and Other Medical Conditions | |||||

| Median duration of HIV diagnosis (yrs)(median, IQR) | 14 (9,22) | 15 (9,21.5) | 17 (11,24) | 16 (11,24) | 0.0042 6 |

| Viral suppression11 (n=808) | 96 (90.6) | 61 (89.7) | 589 (92.9) | 746 (92.3) | 0.4918 |

| CD4 ≥200 cells/μL as of 1/1/20 (n=968) | 103 (95.4) | 69 (98.6) | 617 (95.5) | 789 (95.8) | 0.4726 |

| HIV Mode of Transmission (n=976) | 0.0002 | ||||

| Men who have sex with men (MSM) | 44 (33.6) | 25 (27.2) | 347 (46.1) | 416 (42.6) | |

| Hetero | 45 (34.4) | 42 (45.7) | 188 (25.0) | 275 (28.2) | |

| Injection Drug Use (IDU) | 5 (3.8) | 3 (3.3) | 34 (4.5) | 42 (4.3) | |

| Perinatal | 4 (3.1) | 3 (3.3) | 8 (1.1) | 15 (1.5) | |

| Other12 | 33 (25.2) | 19 (20.7) | 176 (23.4) | 228 (23.4) | |

| Self-reported underlying medical conditions 13 | |||||

| HTN | 51 (38.9) | 31 (32.0) | 366 (45.7) | 448 (43.5) | 0.0189 |

| Current smoker (includes cigarettes, vaping, marijuana) | 59 (45.0) | 46 (47.4) | 293 (36.6) | 398 (36.7) | 0.0326 |

| Overweight or obesity (BMI ≥30) | 26 (19.9) | 16 (16.5) | 172 (21.5) | 214 (20.8) | 0.5006 |

| Asthma (any) | 22 (16.8) | 26 (26.8) | 135 (16.9) | 183 (17.8) | 0.0508 |

| Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 | 16 (12.2) | 8 (8.3) | 107 (13.4) | 131 (12.7) | 0.3552 |

| Cancer | 13 (9.9) | 5 (5.2) | 78 (9.7) | 96 (9.3) | 0.3310 |

| Chronic Lung disease (includes COPD, emphysema, chronic bronchitis) | 7 (5.3) | 11 (11.3) | 54 (6.7) | 72 (7.0) | 0.1788 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (7.6) | 4 (4.1) | 66 (8.2) | 80 (7.8) | 0.3591 |

| CV disease (includes angina or coronary heart disease or history of MI) | 3 (2.3) | 1 (1.0) | 49 (6.1) | 52 (5.2) | 0.0288 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (e.g., stroke) | 10 (7.6) | 6 (6.2) | 28 (3.5) | 44 (4.3) | 0.0589 |

| Number of self-reported underlying medical conditions | 0.5259 | ||||

| 0 | 23 (18.1) | 22 (24.4) | 161 (20.8) | 206 (20.8) | |

| ≥1 | 104 (81.9) | 68 (75.6) | 615 (79.3) | 787 (79.3) | |

| Received influenza vaccine in past 12 months | <.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 92 (72.4) | 44 (47.3) | 596 (75.7) | 732 (72.7) | |

| No | 35 (27.6) | 49 (52.7) | 191 (24.3) | 275 (27.3) | |

| COVID-19 Related Experiences | |||||

| Had self-reported symptoms of COVID-19 | 0.7242 | ||||

| Yes | 19 (14.5) | 17 (17.5) | 116 (14.5) | 152 (14.8) | |

| No | 112 (85.5) | 80 (82.5) | 685 (85.5) | 877 (85.2) | |

| Tested for COVID-19 | 0.2511 | ||||

| Yes | 31 (75.6) | 23 (60.5) | 390 (72.4) | 444 (71.8) | |

| No | 10 (24.4) | 15 (39.5) | 149 (27.6) | 174 (28.2) | |

| Household member had symptoms of COVID-19 | 0.5048 | ||||

| Yes | 14(10.8) | 10 (10.4) | 65 (8.2) | 89 (8.7) | |

| No | 116 (89.2) | 86 (89.6) | 733 (91.9) | 935 (91.3) | |

| Knows someone who died of COVID-19 | 0.6312 | ||||

| Yes | 60 (48.8) | 41 (46.1) | 392 (51.0) | 493 (50.3) | |

| No | 63 (51.2) | 48 (53.9) | 376 (49.0) | 487 (47.0) | |

| COVID time-period of survey completion | <.0001 | ||||

| Pre/Early Vaccination | 102 (77.9) | 69 (71.1) | 290 (36.3) | 461 (44.8) | |

| General Vaccination | 25 (19.1) | 25 (25.8) | 387 (48.4) | 437 (42.5) | |

| Booster | 4 (3.1) | 3 (3.1) | 123 (15.4) | 130 (12.7) |

Hesitant=Answered don’t know to would get vaccine if available today

Vaccinated/Not hesitant=Yes to vaccinated and yes to would get vaccine if available today

Refused= Answered no to would get vaccine if available today

Totals may not sum to N due to missing data

Significant p-values ≤.05 bolded

Chi-square or Wilcoxon test

Other includes American Indian/Alaska native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Bi/multiracial

Other includes student, homemaker, retired, disabled

Essential worker includes construction, food service, delivery service, grocery store, healthcare, hospitality, manufacturing, transportation

Other includes lives with parent/friends, lives in rooming/halfway/group home, lives in residential drug facility, lives in assisted living, other

Viral suppression defined as HIV RNA < 200 copies/ml at last measure but after 1/1/2020

Other includes Hemophilia, blood transfusion, other, unknown

Includes conditions related to vaccine eligibility and those associated with higher risk for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection; participants could report more than one condition.

Comparison of Vaccine Hesitant, Refusals, and Not Hesitant Participants

Of the 1,029 participants, 131 (13%) reported vaccine hesitancy; 97 (9%) reported vaccine refusal and 801 (78%) reported either not being hesitant or that they had already been vaccinated. Vaccine hesitancy/refusal differed significantly across the three groups by age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, work status, essential worker, housing status, duration of HIV diagnosis, and mode of HIV transmission (p-values all <0.05). Hesitancy/refusal also differed by self-reported hypertension, smoking status, cardiovascular disease and having received an influenza vaccine in the prior 12 months (p-values all <0.05). Hesitancy/refusal also differed significantly by the time of vaccine availability and decreased significantly over the 14-month survey period (33% in October 2020 to 4% in December 2021 (p<0.0001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proportional Distribution of Vaccinated, Not Hesitant, Hesitant, and Vaccine Refusers among DC Cohort COVID-19 Survey Participants, October 2020-December 2021.

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of PWH survey participants over time who reported being vaccinated or were not hesitant to get a COVID-19 vaccine, reported being hesitant or refused to get vaccinated.

In adjusted analyses (Table 2), when comparing participants who were hesitant to those who were not or were vaccinated, participants who were older (adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR): 0.89; 95%CI: 0.81–0.98) and who were surveyed in the general vaccination/booster period (aOR: 0.14; 95%CI: 0.09, 0.23) were less likely to be hesitant compared to younger and early/pre-vaccine participants. Females were 2.6 times more likely to express vaccine hesitancy compared to males (aOR: 2.60 95%CI: 1.66–4.06) and non-Hispanic Black participants were 2.2 times (95%CI: 0.88–5.30) more likely to express hesitancy compared to non-Hispanic White participants.

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Vaccine Hesitancy among Persons with HIV in the DC Cohort

| Hesitant (n=131) vs. Not hesitant/vaccinated (n=801) (ref) | Refused (n=97) vs. Not hesitant/vaccinated (n=801)(ref) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor* | OR (95% CI) | *ORa (95%CI)a | OR (95% CI) | cORa (95%CI) a |

| Age (per 5 years) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.93) | 0.89 (0.81, 0.98) | 0.81 (0.75, 0.89) | 0.84 (0.75, 0.93) |

| Gender Female (vs Males) | 2.37 (1.61, 3.49) | 2.60 (1.66, 4.06) | 3.44 (2.23, 5.31) | 3.54 (2.15, 5.85) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black (vs Non-Hispanic Whites) | 4.15 (1.78, 9.64) | 2.16 (0.88, 5.30) | 19.44 (2.68, 140.80) | 8.82 (1.18, 65.89) |

| Hispanic and Other1 (vs Non-Hispanic Whites) | 2.99 (1.21, 7.98) | 1.67 (0.58, 4.83) | 11.96 (1.51, 94.85) | 4.89 (0.58, 41.19) |

| Education HS and above (vs <HS) | 0.82 (0.45, 1.51) | 0.96 (0.48, 1.91) | 0.84 (0.42, 1.69) | 1.52 (0.75, 3.04) |

| Employment | ||||

| Essential employed (vs. non-essential employed) | 0.83 (0.49, 1.40) | 0.71 (0.39, 1.27) | 2.01 (1.09, 3.70) | 1.52 (0.75, 3.04) |

| Unemployed (vs. non-essential employed) | 1.67 (0.97, 2.89) | 1.44 (0.77, 2.71) | 2.16 (1.08, 4.34) | 1.75 (0.79, 3.88) |

| Other (vs. non-essential employed) | 0.88 (0.53, 1.47) | 0.75 (0.40, 1.42) | 1.06 (0.54, 2.08) | 0.90 (0.40, 2.02) |

| Time period General vaccination/booster (vs early/pre-vaccination) | 0.16 (0.10–0.25) | 0.14 (0.09, 0.23) | 0.27 (0.17, 0.44) | 0.20 (0.12, 0.33) |

| Lives alone No (vs Yes) | 0.92 (0.63, 1.35) | 1.34 (0.84, 2.11) | 0.75 (0.48, 1.16) | 1.44 (0.84, 2.46) |

| Site (community vs. hospital-based clinic) | 1.10 (0.75, 1.63) | 1.08 (0.69, 1.69) | 1.27 (0.80, 2.01) | 1.20 (0.71, 2.04) |

| ≥1 high-risk medical condition No (vs Yes) | 0.95 (0.32, 2.77) | 0.63 (0.35, 1.11) | 2.53 (1.06, 6.07) | 0.91 (0.49, 1.67) |

| Housing Status Other2 (vs Own) | 2.05 (1.24, 3.38) | 1.18 (0.65, 2.13) | 4.11 (1.96, 8.61) | 2.51 (1.07, 5.85) |

| Length of HIV diagnosis (per 5 years) | 0.86 (0.77, 0.96) | 0.93 (0.81, 1.07) | 0.86 (0.76, 0.98) | 0.93 (0.79, 1.09) |

| HIV Mode of Transmission | ||||

| Heterosexual (HET) (vs MSM) | 1.89 (1.20, 2.97) | 0.92 (0.46, 1.85) | 3.10 (1.83, 5.25) | 1.33 (0.59, 3.00) |

| Other3 (vs MSM) | 1.52 (0.96, 2.40) | 0.92 (0.50–1.68) | 1.59 (0.89, 2.84) | 0.96 (0.46, 2.06) |

| Viral Suppression (HIV RNA<200 copies/ml) No (vs Yes) | 1.36 (0.67, 2.80) | 0.96 (0.42, 2.21) | 1.50 (0.65, 3.48) | 0.77 (0.28, 2.12) |

| CD4≥200 cells/μL No (vs Yes) | 1.03 (0.39, 2.73) | 0.62 (0.21, 1.84) | 0.31 (0.04, 2.30) | 0.17 (0.02, 1.36) |

| Received influenza vaccine in past 12 months No (vs Yes) | 1.19 (0.78, 1.81) | 0.91 (0.55, 1.49) | 3.48 (2.42, 5.39) | 2.90 (1.73, 4.84) |

| Had self-reported symptoms of COVID-19 No (vs Yes) | 0.99 (0.59, 1.69) | 0.87 (0.49, 1.54) | 0.80 (0.46, 1.39) | 0.70 (0.38, 1.31) |

| Household member had symptoms of COVID-19 No (vs Yes) | 0.74 (0.40, 1.35) | 0.70 (0.35, 1.41) | 0.76 (0.38, 1.54) | 0.94 (0.40, 2.19) |

| Knows someone who died of COVID-19 No (vs Yes) | 0.91 (0.62, 1.34) | 1.14 (0.74, 1.77) | 0.82 (0.53, 1.27) | 0.89 (0.53, 1.47) |

First model adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment and vaccination time-period. All subsequent variables adjusted for each predictor variable and the aforementioned variables

Other includes Hispanic and non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Bi/multiracial

Other includes renting, homeless (living in a shelter or on the streets), lives with parent/friends, lives in rooming/halfway/group home, lives in residential drug facility, lives in assisted living, other

Other includes injection drug use, perinatal, Hemophilia, blood transfusion, other, unknown.

When comparing those who refused vaccination to those who were not hesitant or had been vaccinated, younger people, females, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics and people of other races were all significantly more likely to refuse vaccination in adjusted analyses. Those participants who had not received an influenza vaccine in the past 12 months were 2.9 times (aOR: 2.90; 95%CI: 1.73–4.84) more likely to refuse vaccination compared to those who had received influenza vaccinations. Participants who lived with others or were in transitional housing were 2.5 times more likely to refuse vaccination (95%CI: 1.07–5.85) compared to those that owned their own homes and participants who were vaccinated in the general vaccine/booster period were less likely to refuse (aOR 0.20; 95%CI:0.12–0.33) compared to those in the pre/early vaccine period.

In the stratified adjusted multivariable analysis by time period, we found that in the pre-vaccination period, females were significantly more likely to be vaccine hesitant/refuse vaccination compared to males. In both the pre-vaccine and general/booster vaccination time periods, those who did not get an influenza vaccination were more likely to refuse COVID-19 vaccination. In the general/booster vaccine time period, increasing age was significantly, inversely associated with vaccine refusal and having a household family member with COVID symptoms was associated with significantly decreased likelihood of being vaccine hesitant or refusing vaccination. (See Supplemental Tables).

Reasons for Vaccine Hesitancy

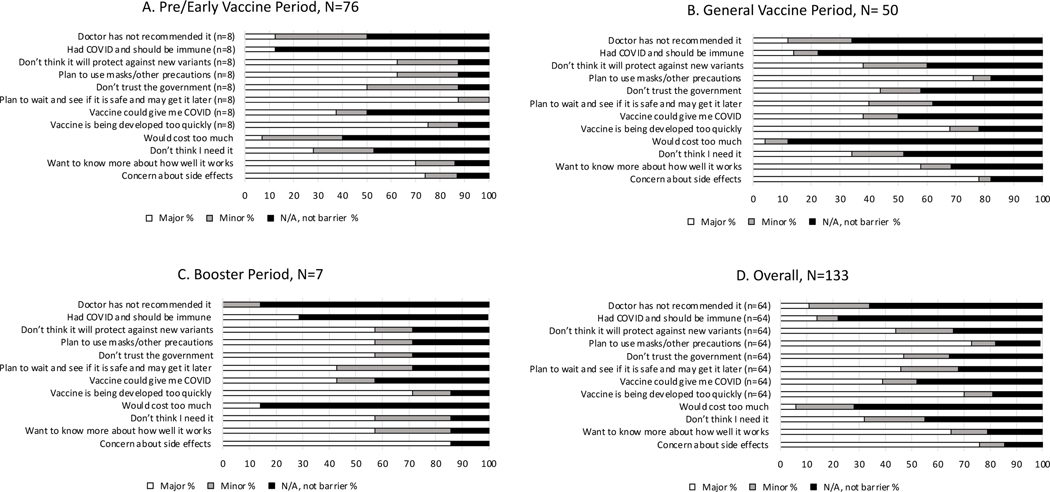

Among participants who were asked about reasons for being hesitant and provided at least one reason, the most reported major concerns were side effects (101/133; 76%), plans to use other precautions/masks (47/64; 73%), concerns about vaccines being developed too quickly (45/64; 70%), and wanting to know more about how well the vaccines work (86/133; 65%) (Figure 2D). These were the most reported major barriers to vaccination across all three time periods (Figure 2A–2C).

Figure 2. Reported Barriers to Vaccine Hesitancy or Refusal among DC Cohort COVID-19 Survey Participants by Vaccination Period1,2.

Notes: 1. Pre/Early Vaccine Period: 10/1/20–3/31/21; General Vaccine Period: 4/1/21–10/31/21; Booster Period: 11/1/21–12/31/21.

2. Responses limited to participants who responded on or after 1/11/2021 when barrier questions were added, had no missing date for survey response, and who responded hesitant or would refuse vaccine. N/A includes those with missing responses.

Vaccine Uptake

In March 2021, after the US Food and Drug Administration Emergency Use Authorization approvals of the Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, and Johnson & Johnson/Janssen COVID-19 vaccines, a question was added to determine if participants had been vaccinated. Overall self-reported vaccination coverage was 47% with an increase in vaccine uptake over the observation period (March 2021, 24% vaccinated vs. 93% in December 2021, p<0.0001) (Figure 1). Most participants reported being vaccinated at a hospital (19%; 95/498), mass vaccination site (16%; 81/498) or community health center (16%; 78/498). Eight percent (40/498) reported being vaccinated by their HIV care provider and 10% (50/498) by their primary care provider. Participants who reported receiving a vaccine were male (70%), non-Hispanic Black people (69%), had received some college education (68%) and were essential workers (58%) (data not shown).

Discussion

This analysis reports on one of the largest cross-sectional COVID-19 surveys administered to PWH both during the emergence and rollout of COVID-19 vaccines,20,26,30 and provides insights into trends in vaccine hesitancy and uptake in an urban, predominantly Black, cohort of PWH. Common reasons for vaccine hesitancy or refusal were similar to those described by the general public including the pace of vaccine development, safety and side effects, and doubts regarding their effectiveness.45,48 However, the proportion of participants who expressed vaccine hesitancy after vaccines became widely available diminished greatly, consistent with local and national data indicating a decline in hesitancy and an increase in vaccine uptake. 37,45,49–51 The increase in uptake may be explained by increased efforts to improve knowledge regarding mRNA technologies, published evidence regarding the efficacy of vaccines, and expanded community-based efforts to provide information and access to vaccines among certain populations.

DC Cohort participants included in this analysis reflect the demographics of the overall Cohort with most PWH being Black people and male, with high rates of viral suppression.52,53 Importantly, while most participants had relatively stable HIV disease, the vast majority (96%) had at least one reported co-morbid condition that would have put them at higher risk for COVID-19 complications and 40% were essential workers, reinforcing the importance of vaccination in this highly vulnerable population.

Despite being a priority population for vaccination, almost one in four PWH participants expressed either vaccine hesitancy or refusal, with hesitant and refusing PWH more likely among women, non-Hispanic Black people and younger PWH. Previous analyses have also found higher rates of hesitancy among women often related to infertility and safety concerns.30,46,54–59 Providing information to women about vaccine safety with respect to reproductive health will be critical to addressing mis- and disinformation60 and can be provided by obstetricians/gynecologists and midwives as well as through social organizations such as sororities.

Other studies have also found higher rates of vaccine hesitancy among Black compared to White participants.57,58,61–63 Our finding that younger PWH were more likely to be vaccine hesitant is also consistent with previous research and current trends in vaccination. 50,64–66 Major reasons for vaccine hesitancy among this cohort included side effects, reliance on other preventive behaviors, concerns about the perceived rapidity of vaccine development and early safety profiles, and government mistrust. These are concerns commonly reported in the literature54,67–69 among both HIV-uninfected persons and PWH.20,30 Of note, we did not collect data on PWH’s political affiliations or beliefs, nor did we ask about issues accessing vaccines, both factors which have been associated with lower vaccine uptake.45,70–73

Potential strategies to overcome hesitancy among PWH might include targeted public health messages that incorporate community engagement57, that acknowledge historical and ongoing medical mistrust, elicit PWH’s concerns, dispel commonly perceived myths, provide reassurance and factual information regarding the vaccine development process, and are transparent regarding what is known about the currently approved vaccines and the changing nature of the pandemic. Potential trusted sources of information could include HIV care providers, HIV peer navigators, faith leaders, barbers and hairdressers, and friends and family members who have been vaccinated. 63,74 These combined efforts may help to counter mis- and dis-information that has spread among vulnerable groups such as PWH of color.

Establishing medical trust in vaccines in the PWH community is of paramount importance. Medical mistrust can widen already existing health disparities and has been shown to impact HIV outcomes such as viral suppression.31,75 In order to engender trust among PWH with respect to vaccination, we should consider understanding the root cause of their concerns, establishing trusting relationships by working in collaboration with communities of PWH, and establishing community-academic partnerships.34 Allaying vaccination concerns will be essential as we continue to see the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants, the use of periodic boosters, and as we determine the role of vaccination in the prevention of severe outcomes such as post-acute sequelae of COVID (PASC). Additionally, understanding and addressing the factors that make PWH hesitant to get vaccinated for COVID-19 can also help lay the groundwork for vaccine uptake in other disease areas such as we observed with mpox and during the winter 2022 “tripledemic” of influenza, COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus. Furthermore, mRNA vaccines may be the foundation for future HIV therapeutic vaccines, hence the importance of ensuring that PWH are knowledgeable and comfortable with these types of technologies.

While these data provide important information regarding perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines, there are some limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional analysis of 1,029 PWH among over 11,000 DC Cohort participants enrolled; nevertheless, the survey participants were similar to the overall DC Cohort population and DC population of PWH with respect to race/ethnicity, gender and age.36,52,53 While our survey results are reflective of PWH in DC, they may not represent PWH in the US or be applicable to younger persons or those recently diagnosed with HIV. Second, when the survey was launched, vaccines were not yet approved, thus vaccine uptake questions were added later during the survey. Similarly, given the 15-month period of data collection and cross-sectional nature of the survey, when boosters were recommended, we were not able to capture hesitancy related specifically to boosters. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the survey did not allow us to assess changes in vaccine uptake or hesitancy over time, particularly as evidence about and access to vaccines and boosters evolved. There may be individuals who were initially hesitant or refused when they completed the survey but who subsequently got vaccinated. Moreover, we were not able to further elucidate what people who reported that they “did not know if they would get vaccinated” meant by that response. Additional qualitative data collection may help to further understand PWHs’ reasons for being unsure of their plans to vaccinate or their reasons for refusing vaccination. Use of validated medical mistrust scales and questions regarding structural barriers to vaccination, may also have helped us understand the drivers behind vaccine hesitancy. Strengths of our analysis include one of the largest sample sizes of PWH, data inclusive of a large percentage of minority PWH, the ability to measure vaccine hesitancy and uptake in both the pre-vaccine and emerging vaccine eras (early, general and booster periods), and longitudinal data to assess changes in vaccine uptake and hesitancy over time.

Evolving COVID-19 vaccine guidelines coupled with the pace of vaccine development and distribution has been remarkable and yet the rapidity with which these vaccines were developed has given some PWH reason to pause. Concerns raised among PWH regarding COVID-19 vaccines need to be addressed with effective strategies for vaccine communication and delivery. Addressing vaccine hesitancy and establishing trust is of utmost importance to protect PWH given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and as we face emerging public health threats and outbreaks that put PWH at high risk for severe outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Data in this manuscript were collected by the DC Cohort Study Group with investigators and research staff located at: Children’s National Medical Center Pediatric Clinic (Natella Rakhmanina); The Senior Deputy Director of the DC Department of Health HAHSTA (Clover Barnes, Michael Kharfen); Family and Medical Counseling Service (Michael Serlin, Angela Wood); Georgetown University (Princy Kumar); The George Washington University Biostatistics Center (Vinay Bhandaru, Tsedenia Bezabeh, Nisha Grover-Fairchild, Lisa Mele, Susan Reamer, Alla Sapozhnikova, Greg Strylewicz, Marinella Temprosa, and Kevin Xiao); The George Washington University Department of Epidemiology (Shannon Barth, Morgan Byrne, Amanda Castel, Alan Greenberg, Maria Jaurretche, Paige Kulie, Anne Monroe, James Peterson, Bianca Stewart, and Brittany Wilbourn) and Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics (Yan Ma); The George Washington University Medical Faculty Associates (Hana Akselrod, Jose Lucar); Howard University Adult Infectious Disease Clinic (Jhansi L. Gajjala) and Pediatric Clinic (Sohail Rana); Kaiser Permanente Mid-Atlantic States (Michael Horberg); La Clinica Del Pueblo (Ricardo Fernandez); MetroHealth (Annick Hebou; Duane Taylor); National Institutes of Health (Henry Masur); Washington Health Institute (Jose Bordon); Unity Health Care (Gebeyehu Teferi); Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Debra Benator, Rachel Denyer); Washington Hospital Center (Maria Elena Ruiz, Glenn Wortmann); and Whitman-Walker Institute (Stephen Abbott).The DC Cohort is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 1R24AI152598-01; the COVID-19 survey was funded through a supplement.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding:

The study was funded through a supplement from the NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for R24AI152598. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University. The Center for Systems Science and Engineering. COVID-19 Dashboard; 2021. Available from: https://www.coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region - Case Series. N Engl J Med. May 21 2020;382(21):2012–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Response Team. Severe Outcomes Among Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - United States, February 12-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Mar 27 2020;69(12):343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: People with Certain Medical Conditions. 2021; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. [PubMed]

- 5.Gold JAW, Rossen LM, Ahmad FB, et al. Race, Ethnicity, and Age Trends in Persons Who Died from COVID-19 - United States, May-August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Oct 23 2020;69(42):1517–1521. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhala N, Curry G, Martineau AR, Agyemang C, Bhopal R. Sharpening the global focus on ethnicity and race in the time of COVID-19. Lancet. May 30 2020;395(10238):1673–1676. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31102-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abedi V, Olulana O, Avula V, et al. Racial, Economic, and Health Inequality and COVID-19 Infection in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. Jun 2021;8(3):732–742. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00833-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel JA, Nielsen FBH, Badiani AA, et al. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Public Health. Jun 2020;183:110–111. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawkins RB, Charles EJ, Mehaffey JH. Socio-economic status and COVID-19-related cases and fatalities. Public Health. Dec 2020;189:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigel K, Swartz T, Golden E, et al. Coronavirus 2019 and People Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: Outcomes for Hospitalized Patients in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. Dec 31 2020;71(11):2933–2938. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vizcarra P, Pérez-Elías MJ, Quereda C, et al. Description of COVID-19 in HIV-infected individuals: a single-centre, prospective cohort. Lancet HIV. Aug 2020;7(8):e554–e564. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(20)30164-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gervasoni C, Meraviglia P, Riva A, et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus With COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. Nov 19 2020;71(16):2276–2278. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okoh A, Bishburg E, Grinberg S, Nagarakanti S. COVID-19 Pneumonia in Patients With HIV: A Case Series. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2018. Vol. 31. 2020. HIV Surveillance Report. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social Determinants of Health Among Adults with Diagnosed HIV Infection, 2018.HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2020; 25(3). 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-supplemental-report-2020-vol25-no3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: How CDC Is Making COVID-19 Vaccine Recommendations. 2021; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations-process.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fvaccines%2Frecommendations.html.

- 17.US Department of Health and Human Services. Interim Guidance for COVID-19 and Persons with HIV. Available from: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/8/covid-19-and-persons-with-hiv--interim-guidance-/554/interim-guidance-for-covid-19-and-persons-with-hiv.

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and COVID-19 Basics. Accessed December 14, 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/covid-19.html.

- 19.Infectious Disease Society of America. COVID-19 Considerations for People with HIV. Available from: https://www.idsociety.org/globalassets/idsa/public-health/covid-19/covid-19-special-considerations.pdf.

- 20.Bogart LM, Ojikutu BO, Tyagi K, et al. COVID-19 Related Medical Mistrust, Health Impacts, and Potential Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black Americans Living With HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Feb 1 2021;86(2):200–207. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinn SC, Andrasik MP. Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy in BIPOC Communities - Toward Trustworthiness, Partnership, and Reciprocity. N Engl J Med. Jul 8 2021;385(2):97–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2103104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khubchandani J, Macias Y. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in Hispanics and African-Americans: A review and recommendations for practice. Brain Behav Immun Health. Aug 2021;15:100277. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. Dec 31 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. Feb 4 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. Jun 10 2021;384(23):2187–2201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrestha R, Meyer JP, Shenoi S, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Associated Factors among People with HIV in the United States: Findings from a National Survey. Vaccines (Basel). Mar 10 2022;10(3)doi: 10.3390/vaccines10030424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall A, Joseph O, Devlin S, et al. “That same stigma...that same hatred and negativity:” a qualitative study to understand stigma and medical mistrust experienced by people living with HIV diagnosed with COVID-19. BMC Infect Dis. Oct 14 2021;21(1):1066. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06693-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swendeman D, Norwood P, Saleska J, et al. Vaccine Attitudes and COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions and Prevention Behaviors among Young People At-Risk for and Living with HIV in Los Angeles and New Orleans. Vaccines (Basel). Mar 9 2022;10(3)doi: 10.3390/vaccines10030413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones DL, Salazar AS, Rodriguez VJ, et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: Vaccine Hesitancy Among Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Groups With HIV in Miami, Florida. Open Forum Infect Dis. Jun 2021;8(6):ofab154. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vallée A, Fourn E, Majerholc C, Touche P, Zucman D. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among French People Living with HIV. Vaccines (Basel). Mar 24 2021;9(4)doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Green HD Jr., et al. Medical mistrust among social network members may contribute to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence in African Americans living with HIV. Soc Sci Med. Sep 2016;164:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaston GB, Alleyne-Green B. The impact of African Americans’ beliefs about HIV medical care on treatment adherence: a systematic review and recommendations for interventions. AIDS Behav. Jan 2013;17(1):31–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0323-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. Jul-Aug 2003;118(4):358–65. doi: 10.1093/phr/118.4.358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaiswal J, Halkitis PN. Towards a More Inclusive and Dynamic Understanding of Medical Mistrust Informed by Science. Behav Med. Apr-Jun 2019;45(2):79–85. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1619511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powell W, Richmond J, Mohottige D, Yen I, Joslyn A, Corbie-Smith G. Medical Mistrust, Racism, and Delays in Preventive Health Screening Among African-American Men. Behav Med. Conway LG III, Woodard SR, & Zubrod A . Social Psychological Measurements of COVID-19: Coronavirus Perceived Threat, Government Response, Impacts,and Experiences Questionnaires. April 7, 2020;doi:. Apr-Jun 2019;45(2):102–117. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.District of Columbia Department of Health HIV/AIDS Hepatitis STDs, and TB Administration (HAHSTA). Annual Epidemiology & Surveillance Report: Data Through December 2020. 2021. Available from: https://dchealth.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/publication/attachments/2020-HAHSTA-Annual-Surveillance-Report.pdf.

- 37.DC Health. COVID-19 Surveillance. Available from: https://coronavirus.dc.gov/data.

- 38.Hartner Z Five members of DC Fire and EMS, including department’s chief, to receive city’s first doses of coronavirus vaccine. WTOP. December 13, 2020. Available from: https://wtop.com/dc/2020/12/five-members-of-dc-fire-and-ems-including-departments-chief-to-receive-citys-first-doses-of-coronavirus-vaccine/. [Google Scholar]

- 39.DC Health. With All DC Residents 16+ Becoming Eligible for the COVID-19 Vaccine on April 19, Mayor Bowser Asks All DC Residents to Pre-Register for an Appointment. Wednesday, April 7, 2021. DC Health; April 7, 2021. Available from: https://coronavirus.dc.gov/release/all-dc-residents-16-becoming-eligible-covid-19-vaccine-april-19-mayor-bowser-asks-all-dc [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg AE, Hays H, Castel AD, et al. Development of a large urban longitudinal HIV clinical cohort using a web-based platform to merge electronically and manually abstracted data from disparate medical record systems: technical challenges and innovative solutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. May 2016;23(3):635–43. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. Jul 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson MM, Kulkarni SG, Rane M, et al. Cohort profile: a national, community-based prospective cohort study of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic outcomes in the USA-the CHASING COVID Cohort study. BMJ Open. Sep 21 2021;11(9):e048778. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conway LG III, Woodard SR, & Zubrod A . Social Psychological Measurements of COVID-19: Coronavirus Perceived Threat, Government Response, Impacts,and Experiences Questionnaires. April 7, 2020;doi:. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: the Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care. Jan 2009;21(1):87–93. doi: 10.1080/09540120802032627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pew Research Center. U.S. Public Now Divided Over Whether to Get COVID-19 Vaccine. 2020. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/17/u-s-public-now-divided-over-whether-to-get-covid-19-vaccine/. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaiser Family Foundation. COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: January 2021. 2021. Available from: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Topline-KFF-COVID-19-Vaccine-Monitor-January-2021.pdf.

- 47.DC Health. COVID-19 Situational Update January 11, 2021. Available from: https://coronavirus.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/coronavirus/page_content/attachments/Updated-Situational-Update-Presentation-1-11-21.pdf.

- 48.Kaiser Family Foundation. COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2020. 2020. Available from: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Topline-KFF-COVID-19-Vaccine-Monitor-December-2020.pdf.

- 49.Kaiser Family Foundation KF. COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: May 2021. 2021. Available from: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Topline-KFF-COVID-19-Vaccine-Monitor-May-2021.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker: COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Padamsee TJ, Bond RM, Dixon GN, et al. Changes in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black and White Individuals in the US. JAMA Netw Open. Jan 4 2022;5(1):e2144470. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castel AD, Terzian A, Opoku J, et al. Defining Care Patterns and Outcomes Among Persons Living with HIV in Washington, DC: Linkage of Clinical Cohort and Surveillance Data. JMIR Public Health Surveill. Mar 16 2018;4(1):e23. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.9221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Opoku J, Doshi RK, Castel AD, et al. Comparison of Clinical Outcomes of Persons Living With HIV by Enrollment Status in Washington, DC: Evaluation of a Large Longitudinal HIV Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. Apr 15 2020;6(2):e16061. doi: 10.2196/16061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Latkin CA, Dayton L, Yi G, Colon B, Kong X. Mask usage, social distancing, racial, and gender correlates of COVID-19 vaccine intentions among adults in the US. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin C, Tu P, Beitsch LM. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines (Basel). Dec 30 2020;9(1)doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roozenbeek J, Schneider CR, Dryhurst S, et al. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. R Soc Open Sci. Oct 2020;7(10):201199. doi: 10.1098/rsos.201199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, Omer SB. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. Sep 2020;26:100495. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paul E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg Health Eur. Feb 2021;1:100012. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diesel J, Sterrett N, Dasgupta S, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Among Adults - United States, December 14, 2020-May 22, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jun 25 2021;70(25):922–927. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologisits. Medical Experts Continue to Assert that COVID Vaccines Do Not Impact Fertility. 2021. https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2021/02/medical-experts-assert-covid-vaccines-do-not-impact-fertility.

- 61.Willis DE, Andersen JA, Bryant-Moore K, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Race/ethnicity, trust, and fear. Clin Transl Sci. Nov 2021;14(6):2200–2207. doi: 10.1111/cts.13077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gramlich J, Funk G. Black Americans face higher COVID-19 risks, are more hesitant to trust medical scientists, get vaccinated. . 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/04/black-americans-face-higher-covid-19-risks-are-more-hesitant-to-trust-medical-scientists-get-vaccinated/.

- 63.Karpman M KG, Zuckerman S, Gonzalez D, Courtot B. Confronting COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Nonelderly Adults: Findings from the December 2020 Well-Being and Basic Needs Survey. 2020. Available from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103713/confronting-covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-among-nonelderly-adults_0_0.pdf

- 64.Troiano G, Nardi A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health. May 2021;194:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robertson E, Reeve KS, Niedzwiedz CL, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav Immun. May 2021;94:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soares P, Rocha JV, Moniz M, et al. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines (Basel). Mar 22 2021;9(3)doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baumgaertner B, Ridenhour BJ, Justwan F, Carlisle JE, Miller CR. Risk of disease and willingness to vaccinate in the United States: A population-based survey. PLoS Med. Oct 2020;17(10):e1003354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gerussi V, Peghin M, Palese A, et al. Vaccine Hesitancy among Italian Patients Recovered from COVID-19 Infection towards Influenza and Sars-Cov-2 Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel). Feb 18 2021;9(2)doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.2 Kaiser Family Foundation. COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: April 2021. Available from: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Topline-KFF-COVID-19-Vaccine-Monitor-April-2021.pdf.

- 70.Fridman A, Gershon R, Gneezy A. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: A longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0250123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williams N, Tutrow H, Pina P, Belli HM, Ogedegbe G, Schoenthaler A. Assessment of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to COVID-19 Vaccination Sites in Brooklyn, New York. JAMA Netw Open. Jun 1 2021;4(6):e2113937. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Y, Fisk RJ. Barriers to vaccination for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) control: experience from the United States. Glob Health J. Mar 2021;5(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2021.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Earnshaw VA, Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Brousseau NM, Hill EC, Fox AB. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl Behav Med. Oct 8 2020;10(4):850–856. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Black Coalition Against COVID. Available from: https://blackcoalitionagainstcovid.org/#.

- 75.Benkert R, Cuevas A, Thompson HS, Dove-Meadows E, Knuckles D. Ubiquitous Yet Unclear: A Systematic Review of Medical Mistrust. Behav Med. Apr-Jun 2019;45(2):86–101. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1588220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.