Abstract

Introduction

Quality improvement interventions are a promising strategy for reducing hospital services use among nursing home residents. However, evidence for their effectiveness is limited. It is unclear which characteristics of the quality improvement intervention and activities planned to facilitate implementation may promote fidelity to organisational and system changes. This systematic review and meta-analysis will assess the effectiveness of quality improvement interventions and implementation strategies aimed at reducing hospital services use among nursing home residents.

Methods and analysis

The MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase and Web of Science databases will be comprehensively searched in September 2023. The eligible studies should focus on the implementation of a quality improvement intervention defined as the systematic, continuous approach that designs, tests and implements changes using real-time measurement to reduce hospitalisations or emergency department visits among long-stay nursing home residents. Quality improvement details and implementation strategies will be deductively categorised into effective practice and organisation of care taxonomy domains for delivery arrangements and implementation strategies. Quality and bias assessments will be completed using the Quality Improvement Minimum Quality Criteria Set and the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools.

The results will be pooled in a meta-analysis, by combining the natural logarithms of the rate ratios across the studies or by calculating the rate ratio using the generic inverse-variance method. Heterogeneity will be assessed using the I2 or H2 statistics if the number of included studies will be less than 10. Raw data will be requested from the authors, as required.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required. The results will be published in a peer-review journal and presented at (inter)national conferences.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42022364195.

Keywords: Aging, Hospitalization, Change management, Nursing Care, Systematic Review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The protocol complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Protocol guideline.

A comprehensive search strategy has been developed to include all eligible studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

The study screening, selection, data extraction and assessment of the risk of bias will be completed by two independent reviewers.

The study will assess both the risk of bias and quality of quality improvement interventions.

The search strategy will not include grey literature.

Introduction

By 2050, the global population aged 80 years or over is estimated to triple1 and the demand for nursing home (NH) services is expected to increase. NH residents have complex health needs and challenging medical situations2 3 that lead to frequent hospital service use.4–6 These are costly and entail the risk of iatrogenic harms, including delirium, infections and loss of functional dependency.7 Although a significant proportion of access to hospital services are helpful and necessary, international research suggests that up to 55% of hospitalisations in NHs can be avoided with appropriate care.8 In fact, many conditions that result in admission or emergency department visit could be averted through proper prevention (eg, exacerbation of chronic diseases or functional decline) or effective on-site management at an early stage (eg, infection or dehydration).9 10 Improving the NH staff’ skills in early recognition and management of acute change of conditions, and the use of standardised communication tools could prevent avoidable access to hospital services.11 Similarly, promoting palliative care and advanced care planning enables healthcare professionals to be aligned with residents’ preferences and values, ensuring the provision of respectful and patient-centred care.12

Quality improvement (QI) interventions may be a promising strategy for improving care for NH residents and preventing hospital service use.13 14 QI intervention is defined as a systematic and continuous approach that designs, tests and implements changes using real-time measurements to improve the safety, effectiveness and experience of care.15 QI interventions are planned as a cyclical process, starting with problem analysis to design a tailored intervention before implementation.16 Changes are constantly measured during and after implementation to understand the impact and adopt the required adjustments.16 The iterative cycle, also known as the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) method is the model used by several QI interventions, such as Total Quality Management (TQM), Lean and Six Sigma.17 QIs are usually designed as multicomponent interventions to tackle an improvement problem, involving all the organisation providers, including front-line staff and using recognised methods to identify all potential causes of the problem and assess the impact of the intervention against the expected results through reliable process and outcome measures.16 QI interventions rely on several implementation strategies to improve adaptation and stakeholder engagement, which may vary widely across projects and include audits, feedback, staff education, tools and site champions.13 18 However, the effects of different implementation strategies on the success of QI interventions remain unclear.

To better describe the heterogeneity of the healthcare interventions, including QI research, the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) group developed a taxonomy for quality interventions based on pragmatic descriptions of components rather than theoretical constructs.19 The EPOC taxonomy, which can be used as a framework for exploring interventions, includes four domains of intervention delivery arrangements, financial arrangements, governance arrangements and implementation strategies each of which is divided into categories and subcategories.20

Previous experiences in hospital acute care settings found QI interventions beneficial in enhancing process care outcomes, such as organisational culture or teamwork, and improving patient care, by reducing the nosocomial infection rate, preventing falls or improving surgical outcomes.21–24 Although previous studies have obtained encouraging results related to QI interventions, evidence of its effectiveness in NH remain limited.25 26 In particular, the INTERACT II intervention significantly reduced hospital admissions through a multicomponent QI intervention aimed at training NH staff to identify and proactively manage major geriatric syndromes, encouraging advanced care planning and promoting palliative care-oriented care.27

Given the high rate of hospital service use among NH residents, it is important to understand whether QI interventions can prevent avoidable transfers. Compared with the hospital setting, the long-term care context poses several challenges that could impede the smooth implementation of a QI initiative.25 28 29 The long-term care context has multiple unique barriers at the organisational level: inner/internal barriers (eg, organisational culture, leadership or learning climate), outer/external barriers (eg, organisational funding, law and regulation) and barriers at the staff level (eg, knowledge, skills and motivation).30

The NH environment can be particularly challenging because of workforce shortages and high turnover rates.31 32 Introducing a practice change that requires staff engagement in an under-resourced organisation may result in poor adherence to the intervention or an unsuccessful programme because of lack of time.33 Additionally, a high staff turnover may lead to a continuous need to support training and education in evidence-based practices and QI methods.29

Another important factor that may influence an organisation’s readiness to change is the involvement of leadership in QI interventions.34 The extent to which management sustains and reinforces cultural change, establishes a positive relationship with front-line staff, and invests resources in the adoption of a new model of care, are crucial features for achieving a high standard of care.29 35 However, NH management is often characterised by a vertical hierarchal structure that can hinder an open flow of communication and prevent all stakeholders from collaborating fruitfully.36

To date, no secondary studies have investigated the effectiveness of QI interventions to prevent hospital services use among NH residents by exploring the factors that contribute to their success, such as delivery arrangements and implementation strategies. Therefore, this systematic review aims to estimate the effectiveness of QI interventions and their implementation strategies in reducing hospital service use among NH residents. In addition, given that the quality of QI interventions is often debated in the literature,37 the secondary aim is to assess the quality and rigour of QI interventions by evaluating whether the solutions tested consider the fundamental domains of a QI interventions, such as organisational readiness, implementation phase, sustainability or adherence.38 Moreover, we will describe delivery arrangements and implementation strategies of QI interventions.

Research questions

How effective are the QI interventions and implementation strategies aimed at preventing hospital service use among NH residents?

What is the quality and rigour of the QI interventions provided in NHs?

Methods and analysis

The protocol complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Protocol 2015 statement for reporting39 (online supplemental material 1). It has been registered in PROSPERO.

bmjopen-2023-074684supp001.pdf (62.5KB, pdf)

Review conceptual model

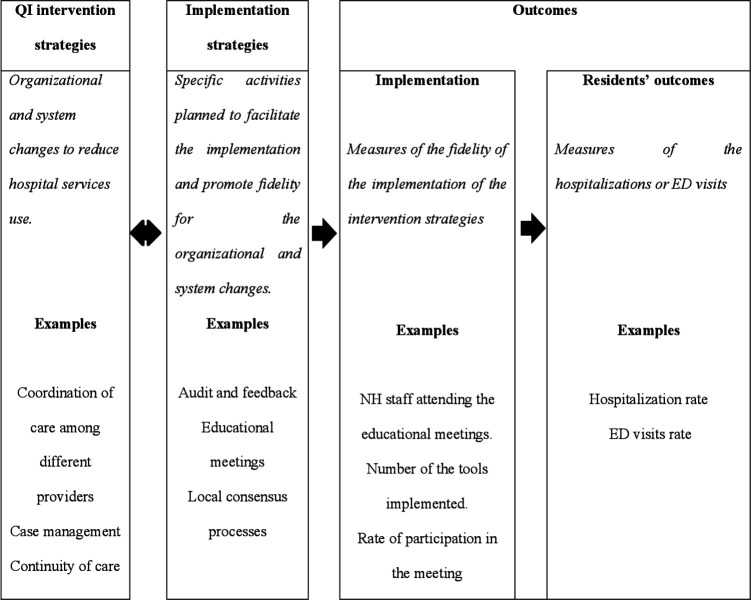

The review will be developed following the implementation research conceptual model proposed by Proctor and collaborators.40 According to the model (figure 1), QI intervention strategies and implementation processes are separated but linked domains. In this review, QI strategies are defined as organisational and system changes to reduce hospital services use. The implementation process involves activities that transfer QI intervention strategies into clinical practice. Both domains impact different but inter-related types of outcomes: implementation and resident outcomes. Implementation outcomes are used to assess the fidelity of implementation strategies. This review aims to assess the effectiveness of QI intervention strategies on hospital service use, assuming that this effect is mediated by implementation strategies and outcomes.

Figure 1.

Adaptation of the implementation research conceptual model. According to the model proposed by Proctor et al,40 QI intervention strategies and implementation processes are separated but linked domains. Both domains impact different but inter-related types of outcomes, implementation and residents’ outcomes. ED, emergency department; NH, nursing home; QI, quality improvement.

Search strategy

Three steps will be used: (1) a preliminary search of PubMed will be conducted to identify keywords; (2) peer-reviewed publications will be sought in the MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase and Web of Science databases; grey literature will be excluded; and (3) the reference lists of all eligible studies will be manually searched for additional papers.

The search strategy has been developed in collaboration with an expert librarian, by combining terms according to the PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes). All terms were searched as controlled vocabulary and text words with title and abstract field limiters, and combined with Boolean Operators (AND, OR). The research has been set from 2000, as no QI has been undertaken before this date,30 until 31 December 2022, and will be re-run on 1 September 2023. No language limitations have been applied. The full search strategy is available in the online supplemental material 2.

bmjopen-2023-074684supp002.pdf (144.7KB, pdf)

Based on a recent international survey,41 an extensive list of terms referring to ‘nursing homes’ has been included.

For the intervention concept, search terms which focus on ‘Quality improvement’ or ‘Organizational innovation’ or ‘Quality Assurance, Health Care’ or ‘Management Quality Circles’, or on a formal model of QI intervention have been used (PDSA; Six Sigma including DMAIC (define, measure; analyze, improve, control) or DMADV (define, measure, analyze, design, verify); TQM, Continuous Quality Improvement, Focus Analyse Develop Execute).42 Moreover, terms concerning implementation strategies have been used, including ‘Implementation Science’, ‘Program Implementation’ or ‘Diffusion of Innovation’. Indeed, when complex interventions are introduced in a real-world context with the goal of changing healthcare professionals’ behaviours, the implementation phase needs to be developed and planned along with the intervention itself.43

For the outcomes, search terms focusing on ‘Hospital admissions’ or ‘Emergency Service, Hospital’ have been used.

Eligibility criteria

The review’s eligibility criteria will be identified based on the following elements of the PICO framework:

Types of participants/setting: Long-stay NH residents, defined as persons who have been institutionalised for at least 30 days. Residents requiring short-term NH or rehabilitation services will be excluded. Studies that recruited mixed populations (short-term and long-term residents) that did not present stratified results, as well as those undertaken in multiple settings (ie, NHs, acute care hospitals, home health agencies) and no opportunity to detect the impact of the QI in NH will be excluded. NHs are defined as facilities that provide nursing care for people with functional or cognitive disabilities and assist them with activities of daily living, with the aim of providing a safe and supportive environment.44 Studies conducted in facilities providing accommodations, without on-site nurses will be excluded.

Intervention(s): This review will include studies focusing on the implementation of QI interventions aimed at reducing hospital services use among NH residents. The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges definition of QI will be used.15 Collaborative QI interventions will also be included because of the importance of the model in healthcare setting.45

Empirical studies will be included if they (1) report measurable continuous local iterative testing of solutions, (2) use real data to guide the change, (3) obtain practical contextual knowledge and (4) encompass at least one implementation strategy developed by the EPOC taxonomy of interventions targeting healthcare workers (eg, distribution of educational materials, educational meetings, clinical practice guidelines, overcoming challenges to improving quality, local opinion leaders).20 These studies may or may not use a formal model (PDSA, Six Sigma, TQM, etc) or a framework for improvement.

Alternatives to QI strategies, such as research (studies that aim to produce generalisable knowledge, testing a hypothesis, through a rigorous method), service evaluation (aims to assess current patient care) or clinical transformation (radical or deep transformation activity without the iterative test of change will be excluded).46

Types of comparison(s): Studies must have a control group that does not receive any QI interventions or a historical cohort to compare the changes before and after the intervention.

Types of outcomes: Primary outcome of the review will focus on hospitalisations, defined as the acute admissions occurring for any conditions, while the secondary outcomes will include hospitalisations at the end of life (last 60 days of life), potentially avoidable hospitalisations (as defined by the authors, using all the existing metrics8), emergency department (ED) visits (the following terms will be considered interchangeably ‘ED transfers’ or ‘ED attendances’ or ‘ED presentations’ or ‘Unplanned transfers’) and readmissions.

Both subjective (eg, self-reported by NH staff) or objective measure (eg, hospital database) of hospital service use will be collected.

Type of study designs: Randomised controlled trials, non-randomised controlled trials, uncontrolled before-and-after trials or interrupted time series designed with at least three data points before and three after the intervention.

Selecting studies

Two reviewers (IB and SG) independently performed the screening process to determine eligibility. Zotero will be used as the reference manager software. First, the title and abstract will be evaluated; then, the full text of potentially eligible studies will be examined for compliance with the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements will be resolved by a third author (ADM).

Risk-of-bias assessment

Two independent reviewers will assess the risk of bias of the studies included in the review using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools, based on the study design.47 These tools provide a set of questions that reviewers can answer with yes (ie, criterion met), no (ie, a criterion not met), unclear or not applicable. No study will be excluded by the methodological quality assessment.

Appraisal of the quality of QI interventions

The quality of the QI interventions will be appraised for each included study using the QI Minimum Quality Criteria Set (QI-MQCS) to inform the transferability of the best evidence into clinical practice.38 The QI-MQCS addresses the following core QI domains: organisational motivation, intervention rationale, intervention description, organisational characteristics, implementation, study design, comparator, data source, timing, adherence/fidelity, health outcomes, organisational readiness, penetration/reach, sustainability, spread and limitations.

Data extraction

Two members (IB and SG) of the research team will independently extract the following study characteristics:

Study details: Study design, date of publication, participants (NH organisational characteristics, ownership, size, etc) and study setting.

QI intervention details: Characteristics and implementation strategies, data on the formal model used (if any) and information to appraise the quality of QI interventions (description of organisational problems, reasons or motivations for the intervention, intervention description, basic characteristics of the organisation, etc) were extracted.

Hospital service use: Data on hospitalisations, potentially avoidable hospitalisations, end-of-life hospitalisations, ED visits and readmissions.

Data synthesis

Data from the included studies will be combined into a meta-analysis based on the outcomes. The results will be pooled by combining the natural logarithms of the rate ratio across studies, or by calculating the rate ratio using the generic inverse-variance method. We will use a permutation random-effect model to estimate meta-analysis effect. Heterogeneity will be assessed using the I2 statistics and we will consider a high level of heterogeneity an I2>75%. Considering that the I2 statistics is biassed in small meta-analysis, we will test heterogeneity with the H2 if it will be included in less than 10 studies. We choose an acceptable level of H2 under 1.88 with a confidence of 95%.48

Publication bias will be visually evaluated using funnel plot if more than 10 studies will be included. We will request raw data from the authors when the reported outcomes in the included studies are not homogeneous. All analyses will be performed using the Stata/SE V.17.

A narrative synthesis will also be arranged. The characteristics of the included studies will be synthetised and compared in a table. The characteristics of the QI and implementation strategies will be deductively categorised into the EPOC taxonomy’s domains on delivery arrangements and implementation strategies, using all subcategories.20 The domains of governance and financial arrangements will be excluded because they are beyond the scope of this review.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in this research’s design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required for this study as it is a review based on published studies. The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis will support clinical and organisational decision-making by determining which QI interventions effectively prevent the use of hospital services and identifying which implementation strategies are most successful in fostering adherence to organisational and system changes within NH settings. The results of this study will be presented at a scientific conference and submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Maoret Roberta of the Biblioteca Virtuale per la Salute – Piemonte for her support in the development of the search strategy.

Footnotes

SC and ADM contributed equally.

Contributors: IB, ADM, SCam, SG, EB and SCar jointly contributed to the study aims, research design and methodology. IB, SG, SCar and EB produced the first draft of the article outline with the guidance of SCam, and ADM. IB and EB designed the search strategy. All authors (IB, ADM, SCam, SG, SCar and EB) contributed substantially to the manuscript and critically revised the content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research programme ‘Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023–2027’, AGING Project – Department of Translational Medicine, Università del Piemonte Orientale.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Ageing, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_1 [Accessed 26 Dec 2022].

- 2.Sverdrup K, Bergh S, Selbæk G, et al. Trajectories of physical performance in nursing home residents with dementia. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;32:2603–10. 10.1007/s40520-020-01499-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S, Middleton A, Ottenbacher KJ, et al. Trajectories over the first year of long-term care nursing home residence. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19:333–41. 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirsebom M, Hedström M, Wadensten B, et al. The frequency of and reasons for acute hospital transfers of older nursing home residents. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2014;58:115–20. 10.1016/j.archger.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simo N, Cesari M, Tchiero H, et al. Frailty index, hospital admission and number of days spent in hospital in nursing home residents: results from the incur study. J Nutr Health Aging 2021;25:155–9. 10.1007/s12603-020-1561-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann F, Allers K. Age and sex differences in Hospitalisation of nursing home residents: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011912. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dwyer R, Gabbe B, Stoelwinder JU, et al. A systematic review of outcomes following emergency transfer to hospital for residents of aged care facilities. Age Ageing 2014;43:759–66. 10.1093/ageing/afu117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemoyne SE, Herbots HH, De Blick D, et al. Appropriateness of transferring nursing home residents to emergency departments: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:17. 10.1186/s12877-019-1028-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially Avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and costs: [see editorial comments by DRS. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:627–35. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frick J, Möckel M, Muller R, et al. Suitability of current definitions of ambulatory care sensitive conditions for research in emergency Department patients: a secondary health data analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016109. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trahan LM, Spiers JA, Cummings GG. Decisions to transfer nursing home residents to emergency departments: A Scoping review of contributing factors and staff perspectives. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:994–1005. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pimsen A, Kao C-Y, Hsu S-T, et al. The effect of advance care planning intervention on hospitalization among nursing home residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2022;23:1448–60. 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toles M, Colón-Emeric C, Moreton E, et al. Quality improvement studies in nursing homes: a Scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:803. 10.1186/s12913-021-06803-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mileski M, Topinka JB, Lee K, et al. An investigation of quality improvement initiatives in decreasing the rate of Avoidable 30-day, skilled nursing facility-to-hospital Readmissions: a systematic review. Clin Interv Aging 2017;12:213–22. 10.2147/CIA.S123362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Academy of Medical Royal Collages . Quality Improvement-training for better outcomes, 2016. Available: https://www.aomrc.org.uk/reports-guidance/quality-improvement-training-better-outcomes [Accessed 2 Apr 2022].

- 16.The Health Foundation . Quality improvement made simple, 2021. Available: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/quality-improvement-made-simple [Accessed 12 Apr 2022].

- 17.Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, et al. Systematic review of the application Of321 the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in Healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:290–8. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woo K, Milworm G, Dowding D. Characteristics of quality improvement champions in nursing homes: A systematic review with implications for evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2017:440–6. 10.1111/wvn.12262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimshaw J, McAuley LM, Bero LA, et al. Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies and programmes. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:298–303. 10.1136/qhc.12.4.298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) . EPOC Taxonomy-topics list delivery arrangements. Available: epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy [Accessed 2 Mar 2022].

- 21.Nicolay CR, Purkayastha S, Greenhalgh A, et al. Systematic review of the application of quality improvement Methodologies from the manufacturing industry to surgical Healthcare. Br J Surg 2012;99:324–35. 10.1002/bjs.7803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buljac-Samardzic M, Doekhie KD, van Wijngaarden JDH. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: a systematic review of the past decade. Hum Resour Health 2020;18:2. 10.1186/s12960-019-0411-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tricco AC, Thomas SM, Veroniki AA, et al. Quality improvement strategies to prevent falls in older adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2019;48:337–46. 10.1093/ageing/afy219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCleskey SG, Shek L, Grein J, et al. Economic evaluation of quality improvement interventions to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections in the hospital setting: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2022;31:308–21. 10.1136/bmjqs-2021-013839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy C, Au D, Ozkaynak M. Innovation and quality improvement: safe or sabotage in nursing homes? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22:1670–1. 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexander JA, Hearld LR. What can we learn from quality improvement research? A critical review of research methods. Med Care Res Rev 2009;66:235–71. 10.1177/1077558708330424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, et al. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:745–53. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouslander JG, Reyes B, Yang Z, et al. Nursing home performance in a trial to reduce hospitalizations: implications for future trials. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69:2316–26. 10.1111/jgs.17231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rantz MJ, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Flesner M, et al. “Challenges of using quality improvement methods in nursing homes that "need improvement"” J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:732–8. 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC, et al. The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: a systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q 2010;88:500–59. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00611.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mills WL, Pimentel CB, Snow AL, et al. Nursing home staff perceptions of barriers and Facilitators to implementing a quality improvement intervention. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20:810–5. 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer JA, Parker VA, Mor V, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to implementing a pragmatic trial to improve advance care planning in the nursing home setting. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:527. 10.1186/s12913-019-4309-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gagnon MM, Hadjistavropoulos T, Williams J. Development and mixed-methods evaluation of a pain assessment Video training program for long-term care staff. Pain Res Manag 2013;18:307–12. 10.1155/2013/659320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scoville R, Little K, Rakover J, et al. Sustaining improvement. IHI White Paper. Cambridge 2016. Available: https://www.ihi.org [accessed 15 Feb 2022].

- 35.Hickman SE, Miech EJ, Stump TE, et al. Identifying the implementation conditions associated with positive outcomes in a successful nursing facility demonstration project. Gerontologist 2020;60:1566–74. 10.1093/geront/gnaa041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wicke D, Coppin R, Payne S. Teamworking in nursing homes. J Adv Nurs 2004;45:197–204. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02881.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan E, Laupacis A, Pronovost PJ, et al. How to use an article about quality improvement. JAMA 2010;304:2279–87. 10.1001/jama.2010.1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hempel S, Shekelle PG, Liu JL, et al. Development of the quality improvement minimum quality criteria set (QI-MQCS): a tool for critical appraisal of quality improvement intervention publications. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:796–804. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement, 2015. Available: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero [Accessed 4 Mar 2022]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, et al. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health 2009;36:24–34. 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burton JK, Quinn TJ, Gordon AL, et al. Identifying published studies of care home research: an international survey of researchers. Jour Nursing Home Res 2017. 10.14283/jnhrs.2017.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McPheeters ML, Sunil Kripalani M, Peterson NB, et al. Quality Improvement Interventions To Address Health Disparities, 2012. Available: www.ahrq.gov cite [Accessed 12 Feb 2022]. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of medical research Council guidance. BMJ 2021;374:2061. 10.1136/bmj.n2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanford AM, Orrell M, Tolson D, et al. “An international definition for "nursing home"” J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:181–4. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, et al. Are quality improvement Collaboratives effective? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27:226–40. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Backhouse A, Ogunlayi F. Quality improvement into practice. BMJ 2020;368:m865. 10.1136/bmj.m865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tufanaru CM. Chapter 3: systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. 10.46658/JBIRM-190-01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dwivedi SN. Which is the preferred measure of heterogeneity meta-analysis and why? A Revisit. BBOAJ 2017;1:555555. 10.19080/BBOAJ.2017.01.555555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-074684supp001.pdf (62.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-074684supp002.pdf (144.7KB, pdf)