Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS:

Practice guidelines promote a routine noninvasive, non-endoscopic initial approach to investigating dyspepsia without alarm features in young patients, yet many patients undergo prompt upper endoscopy. We aimed to assess tradeoffs among costs, patient satisfaction, and clinical outcomes to inform discrepancy between guidelines and practice.

METHODS:

We constructed a decision-analytic model and performed cost-effectiveness/cost-satisfaction analysis over a 1-year time horizon on patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia without alarm features referred to gastroenterology. A RAND/UCLA expert panel informed model design. Four competing diagnostic/management strategies were evaluated: prompt endoscopy, testing for Helicobacter pylori and eradicating if present (test-and-treat), testing for H pylori and performing endoscopy if present (test-and-scope), and empiric acid suppression. Outcomes were derived from systematic reviews of clinical trials. Costs were informed by prospective observational cohort studies and national commercial/federal cost databases. Health gains were represented using quality-adjusted life years.

RESULTS:

From the patient perspective, costs and outcomes were similar for all strategies (maximum out-of-pocket difference of $30 and <0.01 quality-adjusted life years gained/year regardless of strategy). Prompt endoscopy maximized cost-satisfaction and health system reimbursement. Test-and-scope maximized cost-effectiveness from insurer and patient perspectives. Results remained robust on multiple one-way sensitivity analyses on model inputs and across most willingness-to-pay thresholds.

CONCLUSIONS:

Noninvasive management strategies appear to result in inferior cost-effectiveness and patient satisfaction outcomes compared with strategies promoting up-front endoscopy. Therefore, additional studies are needed to evaluate the drivers of patient satisfaction to facilitate inclusion in value-based healthcare transformation efforts.

Keywords: Costs and Cost Analysis, Comparative Effectiveness Research, Insurance, Endoscopy

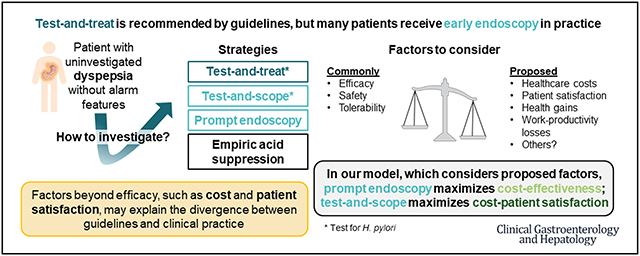

Graphical Abstract

Dyspepsia is a common gastrointestinal complaint that is broadly defined by the presence of epigastric pain or burning, early satiety, and/or post-prandial fullness. Dyspepsia affects approximately 20% of adults, encompasses one-fifth of all gastroenterology consultations,1,2 and leads to one-half of all upper gastrointestinal endoscopies performed each year in the United States.3 Medical and prescription drug costs for dyspepsia represent $18 billion annually in the United States alone.4 These large numbers suggest that the choice of routine dyspepsia management strategy has a major downstream impact on U.S. healthcare.

Clinical practice guidelines, including the joint American College of Gastroenterology and the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology guideline, the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline, and the American Gastroenterological Association position statement, uniformly advocate in favor of an initial noninvasive test-and-treat strategy and against routine upper endoscopy to investigate dyspepsia for patients younger than age 50–60 years presenting without alarm features such as bleeding, weight loss, and vomiting.5–7 With a test-and-treat strategy, a noninvasive test for Helicobacter pylori is administered, and if positive, treatment to eradicate H pylori is provided. If negative or if dyspeptic symptoms persist after successful H pylori eradication, patients should receive empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy. Providers are only recommended to consider endoscopy if these efforts fail.

However, these guidelines have seen variable uptake in practice, and dyspepsia remains a common reason for upper endoscopy regardless of alarm features.2–4,8–10 Prior studies estimated that only 50% of physician visits adhered to these guidelines, and that as few as 25% of upper endoscopies performed for dyspepsia were “appropriate” as defined by guidelines. These findings beg 3 basic questions that stakeholders should consider:

In performing routine endoscopy for dyspepsia, are the majority of gastroenterologists and their patients actually choosing “inappropriate” care?

Are there important factors that might explain the divergence between guidelines and practice that should be considered in guideline development?

Which single stakeholder ultimately gets to define the “correct” management strategy and what is considered “appropriate” or “inappropriate”?

To inform key stakeholders, including patients, gastroenterology providers, insurers, and policymakers, as well as future guideline development strategies, we aimed to explore the persistent divergence between guidelines and practice using cost-effectiveness methods. We focused on identifying critical factors that drive preferences toward particular dyspepsia management strategies among key stakeholder perspectives. Because cost-effectiveness models consider a broad set of inputs for a decision (in this case, selecting up-front management for dyspepsia), a result that differs from that of clinical outcomes–focused studies may indicate factors beyond efficacy and safety are drivers of treatment selection.

Methods

Our study adhered to the CHEERS checklist and guidelines for the conduct of cost-effectiveness analyses established by the Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine.11

Model Development

To systematically inform model design and appropriately recognize the inherent diversity of opinions among experts, we convened a panel of 9 gastroenterologists (each with >10 peer-reviewed publications related to disorders of brain-gut interaction or cost-effectiveness in gastroenterology and with demonstrated leadership in clinical care for dyspepsia) in August 2021. Following the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method,12 panelists were sent background information including practice guidelines and systematic reviews relevant to dyspepsia management. We then performed a 3-round survey in which panelists iteratively rated the appropriateness of potential model assumptions from 1 to 9 (1–3, inappropriate; 4–6, uncertain/unsure; 7–9, appropriate) (Supplementary Table 1). Assumptions that were rated as inappropriate by at least 1 panelist or uncertain/unsure by at least 2 panelists were discussed on a 90-minute videoconference call and revised before the final survey, which was consistent with standard RAND/UCLA scoring instructions.

Model Design

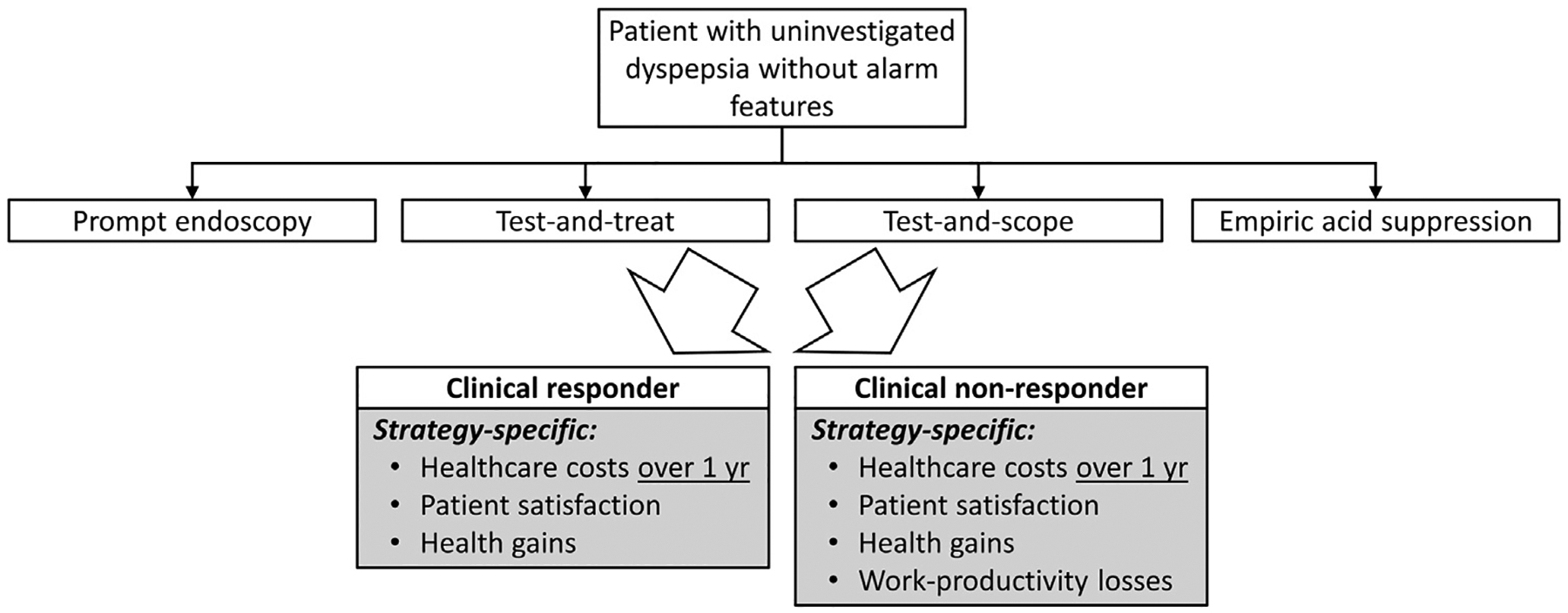

We constructed a decision analytic model using TreeAge Pro 2022 R1.2 (TreeAge, Williamstown, MA) simulating a base case scenario of a healthy, commercially insured patient aged 18–50 years with uninvestigated dyspepsia without alarm features referred to gastroenterology for evaluation and management (Figure 1). Our base case recognizes that Medicare generally covers individuals older than age 65, and that no guideline advocates routine endoscopy for individuals younger than 50 years of age. We compared 4 standardized diagnostic and initial management strategies that were included in a recent systematic review of randomized clinical trials for being potentially applicable to this paradigm: (1) prompt endoscopy; (2) test-and-treat (test for H pylori and prescribe eradication treatment to those who test positive); (3) test-and-scope (test for H pylori and perform endoscopy in those who test positive); and (4) empiric acid suppression (8-week proton pump inhibitor trial).13

Figure 1.

Model design.

We designed our model to follow recent evidence-based syntheses that broadly recognize variation in clinical outcomes, satisfaction, and costs among dyspepsia management strategies as largely depending on the choice and timing of endoscopy weighed against the expected prevalence and severity of typical conditions that explain or overlap with dyspepsia. These conditions include erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, functional dyspepsia, gastroparesis, and others. There is also significant regional and patient-level variation in H pylori status and antibiotic resistance. Rather than modeling each factor individually and recognizing limitations in generalizable evidence, our approach accounts for population-level outcomes and costs for uninvestigated dyspepsia associated with our primary objectives. Further variation on patient subpopulations cared for in quaternary care centers was outside the scope of this study.

Model Inputs

Model inputs including distributions and sources are reported in Table 1. Our primary clinical outcome was global symptom relief (ie, the probability that patients managed with this strategy achieve meaningful improvement in symptoms at final point of follow-up), matching the primary clinical outcome of a recent well-conducted systematic review of randomized clinical trials including more than 6000 participants in 15 randomized controlled trials.13 Binary outcomes strengthen the homogeneity of individual trials included in network meta-analyses and informing our model. Outcomes were translated into health utilities for the purposes of cost-effectiveness analysis based on a large observational burden-of-illness study mapping clinical response onto health utilities.14 Health utilities in cost-effectiveness studies range from 0 (death) to 1 (full health). Over 1 year, a health utility of 1 generates a full year of complete health (quality-adjusted life year [QALY]). Health gains are typically small outside of intensive care or end-of-life settings, recognizing that incremental health gains are significant over time. With a reported impact of 0.09 QALY experienced by patients with dyspepsia, patients would gain an entire year of full health (1.0 QALY) over 11 years of sustained symptom relief.

Table 1.

Model Inputs

| Description | Base-case value | 5th percentile | 95th percentile | Distribution | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | |||||

| Nonresponse with empiric acid suppression | 77.9% | 76.0% | 79.7% | Beta: N = 1329 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Nonresponse with prompt endoscopy | 73.7% | 72.0% | 75.3% | Beta: N = 1942 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Nonresponse with symptom-based management | 80.2% | 77.1% | 83.1% | Beta: N = 469 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Nonresponse with test-and-scope | 70.2% | 66.8% | 73.6% | Beta: N = 484 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Nonresponse with test-and-treat | 76.2% | 74.6% | 77.8% | Beta: N = 1938 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Dissatisfaction with empiric acid suppression | 47.7% | 44.3% | 51.1% | Beta: N = 591 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Dissatisfaction with prompt endoscopy | 31.9% | 28.1% | 35.8% | Beta: N = 395 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Dissatisfaction with test-and-scope | 58.3% | 52.5% | 64.0% | Beta: N = 199 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Dissatisfaction with test-and-treat | 47.3% | 43.4% | 51.3% | Beta: N = 431 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Likelihood of undergoing upper endoscopy with empiric acid suppression | 38.8% | 36.6% | 41.1% | Beta: N = 1238 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Likelihood of undergoing upper endoscopy with prompt endoscopy | 95.3% | 94.5% | 96.1% | Beta: N = 1856 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Likelihood of undergoing upper endoscopy with symptom-based management | 32.5% | 28.6% | 36.5% | Beta: N = 379 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Likelihood of undergoing upper endoscopy with test-and-scope | 45.5% | 41.7% | 49.2% | Beta: N = 484 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Likelihood of undergoing upper endoscopy with test-and-treat | 24.0% | 22.3% | 25.7% | Beta: N = 1738 | Eusebi, et al (2019)13 |

| Quality-adjusted life years | |||||

| Health utility associated with symptomatic dyspepsia | 0.91 | 5th percentile: 0.89 Minimum: 0.79 (severe dyspepsia) |

95th percentile: 0.93 Maximum: 0.96 (mild dyspepsia) |

Beta | Groeneveld, et al (2001)14 |

| Health utility without symptomatic dyspepsia | 1.0 | ||||

| Costs | |||||

| Multiplier for commercial insurer costs compared with U.S. Medicare costs (below) | 1.99 | Minimum: 1.41 | Maximum: 2.59 | Kaiser Family Foundation15 | |

| Annual healthcare cost among patients with symptomatic dyspepsia modified by commercial multiplier | $17,392.64 | 5th percentile: $9428 Minimum: $0 |

95th percentile: $27,756 Maximum: $17,392.64 |

Gamma | Brook, et al (2010)16 |

| Annual healthcare cost among patients without symptomatic dyspepsia modified by commercial multiplier | $7983.16 | Brook, et al (2010)16 | |||

| Cost of endoscopy (CPT 4329 + APC 5301 with conscious sedation CPT 99152) modified by commercial multiplier | $962.43 | HOPPS January 2021 Addendum B17 | |||

| Annual patient-borne over-the-counter healthcare expenses related to symptomatic dyspepsia | $461.38 | Lacy, et al (2013)4 | |||

| Annual work absenteeism related to symptomatic dyspepsia | 10.76 days | 0 days Minimum: 0 days |

26 days Maximum: 30 days |

Gamma | Brook, et al (2010)16 |

| Annual work absenteeism without symptomatic dyspepsia | 9.18 days | Brook, et al (2010)16 | |||

| Mean annual wage | $70,348.80 | Minimum: $0 | Maximum: $100,000 | US Bureau of Labor Statistics18 | |

| Half-day cost of childcare to attend clinic (accounting for 25% of households having children) | $14.50 | Minimum: $0 | Maximum: $14.50 | US Census Bureau19 Cost of Care Survey20 | |

| Annual work absenteeism related to dyspepsia for transportation and childcare related to medical care | 3.93 days | Minimum: 0 days | Maximum: 30 days | Brook, et al (2010)16 | |

| Transportation to/from medical visits | $10 | Minimum: $0 | Maximum: $10 | Muennig (2008)21 | |

NOTE. Distributions were modeled in probabilistic sensitivity, and point estimates were used for other variables. Minimum and maximum ranges were used in multiple one-way sensitivity analyses. Clinical outcomes were derived from network meta-analysis and systematic reviews of randomized clinical trials evaluating discrete management strategies for uninvestigated dyspepsia compared with symptom-based management. All costs were inflated to 2021 US dollars ($).

APC, Ambulatory Payment Classification; CPT, Computerized Procedural Terminology; HOPPS, Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System.

Patient satisfaction was similarly defined and derived from the related primary outcome of “whether patients reported satisfaction with care” in the recent network meta-analysis.13

To accommodate variation in outcomes and satisfaction with local implementation of various dyspepsia management strategies, we applied data from the same network meta-analysis that anchored each standardized dyspepsia management strategy against non-standardized “usual care” in gastroenterology care settings for similar patient populations.13 Because many patients eventually undergo endoscopy regardless of up-front strategy, even in clinical trials, we were able to incorporate this probability and associated cost into our primary analysis.13

Healthcare costs included all costs to manage dyspepsia and any identified organic pathology. Patient out-of-pocket expenses were derived from observational studies. Work-productivity losses (ie, lost wages) were incurred among patients with persistent dyspeptic symptoms and referenced against average commercial healthcare costs and wages among dyspeptic and non-dyspeptic patients in the United States according to appropriate prospective observational data16 and data from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Healthcare costs in patients not achieving symptom improvement were modeled as equivalent to observational costs of dyspepsia. Of note, because these data are observational, they include costs associated with current utilization patters of dyspepsia, on average, across the U.S. population. This includes treatment methods not assessed here as well as cost of rare outcomes such as endoscopic complications; therefore, these rare outcomes are not specifically modelled. Healthcare costs were scaled to 2021 using the health component of the Personal Consumption Expenditure Price Index, consistent with best practice recommendations.11,22

Analysis

We performed cost-effectiveness and cost-satisfaction analysis on our decision-analytic model from insurer, health system/provider, and patient perspectives. A 1-year time horizon was used, which is consistent with the usual time frame for commercial insurance premium determinations and with the time horizon for the underlying network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials on which model inputs were derived. No discount rate was applied because of the short time horizon. To assess the reasonable and expected ranges of “what-if” scenarios at a population level and the related robustness of our resultant findings, we conducted standard and extensive sensitivity analyses on individual costs and outcomes informed by their distributions in underlying clinical trials and observational studies.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses using Monte Carlo simulation of 10,000 individual patients were further used to assess model robustness. Acceptability curves were constructed to evaluate the likelihood of each intervention being the most cost-effective and most cost-satisfactory at contemporary willingness-to-pay thresholds ranged from 0 to $150,000 to achieve a complete healthy year of life (cost-effectiveness analysis) or complete care satisfaction (cost-satisfaction analysis).11 One-way sensitivities assessing the influence of the range of model inputs on study outcomes are included in the Supplementary Material.

Results

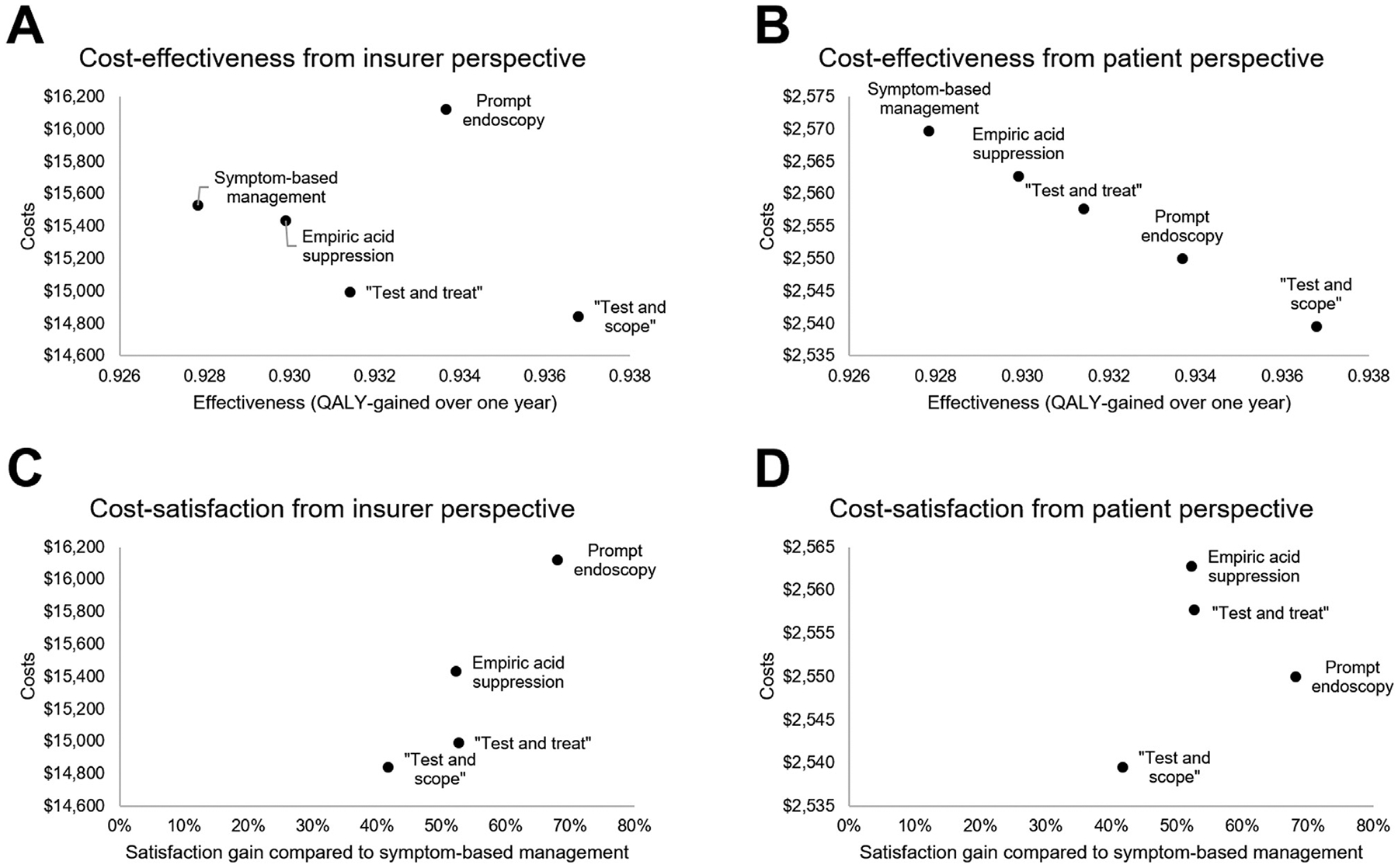

In our base case scenario of a healthy, commercially insured individual younger than 50 years of age with uninvestigated dyspepsia without alarm features referred to gastroenterology, all management strategies were similarly effective (maximum difference of 3 healthy days gained per year between any 2 strategies). From a patient perspective, costs were similar regardless of strategy, with a maximum difference between any 2 strategies of $30.20 accounting for healthcare-related out-of-pocket costs and lost wages due to dyspepsia over a 1-year period. From an insurer or health system/practice perspective, healthcare costs (ie, reimbursement) were highest with prompt endoscopy and lowest with a test-and-scope strategy, with a difference of $1280 per patient between these strategies. Prompt endoscopy maximized patient satisfaction (+ 68.1% vs usual care), whereas patient satisfaction was lowest with test-and-scope. Full costs, effectiveness, and patient satisfaction outcomes with each strategy are reported in Tables 2 and 3. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios are not reported because of strong dominance (ie, ranked preference) among strategies in our model.

Table 2.

Cost-Effectiveness of Standardized Management Strategies by Gastroenterologists for Uninvestigated Dyspepsia From Insurer and Patient Perspectives

| Management strategy | Cost ($) | Effectiveness (quality-adjusted life years gained/year) | Incremental cost | Incremental effectiveness | Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient perspective | |||||

| Symptom-based management | 2570 | 0.928 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Test-and-scope | 2540 | 0.937 | ($30) | +0.009 | Dominates all strategies |

| Prompt endoscopy | 2550 | 0.934 | ($20) | +0.006 | Dominates test-and-treat, empiric acid suppression, and symptom-based management |

| Test-and-treat | 2558 | 0.931 | ($12) | +0.003 | Dominates empiric acid suppression and symptom-based management |

| Empiric acid suppression | 2563 | 0.930 | ($7) | +0.002 | Dominates symptom-based management |

| Insurer perspective | |||||

| Symptom-based management | 15,527 | 0.93 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Test-and-scope | 14,842 | 0.937 | ($685) | +0.009 | Dominates all strategies |

| Prompt endoscopy | 16,121 | 0.934 | $594 | +0.006 | Dominates test-and-treat, empiric acid suppression, and symptom-based management |

| Test-and-treat | 14,992 | 0.931 | ($535) | +0.003 | Dominates empiric acid suppression and symptom-based management |

| Empiric acid suppression | 15,432 | 0.930 | ($95) | +0.002 | Dominates symptom-based management |

Table 3.

Cost Satisfaction of Standardized Management Strategies by Gastroenterologists for Uninvestigated Dyspepsia From Insurer and Patient Perspectives

| Management strategy | Annual cost ($) | Incremental cost | Incremental patient satisfaction gain referenced against symptom-based management | Incremental cost-satisfaction ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient perspective | ||||

| Symptom-based management | 2570 | Reference | Reference | |

| Test-and-scope | 2540 | ($30) | +41.70% | Reference |

| Prompt endoscopy | 2550 | ($20) | +68.10% | $0.38 per patient per 1% satisfaction gain |

| Test-and-treat | 2558 | ($12) | +52.70% | $1.64 |

| Empiric acid suppression | 2563 | ($7) | +52.30% | $2.17 |

| Insurer perspective | ||||

| Symptom-based management | 15,527 | Reference | Reference | |

| Test-and-scope | 14,842 | ($685) | +41.70% | Reference |

| Test-and-treat | 14,992 | ($535) | +52.70% | $13.64 per patient per 1% satisfaction gain |

| Prompt endoscopy | 16,121 | $594 | +68.10% | $48.45 |

| Empiric acid suppression | 15,432 | ($95) | +52.30% | $55.66 |

From both insurer and patient perspectives, test-and-scope was the most cost-effective strategy and by maximizing effectiveness and minimizing costs therefore “dominated” competing strategies (Figure 2A and B). From an insurer perspective, an additional $55.79/patient expenditure would be needed to improve satisfaction by 1% in choosing empiric acid suppression rather than test-and-scope. The added costs would be $13.71/patient for every 1% satisfaction gain with test-and-treat and $48.44/patient for a 1% satisfaction gain with prompt endoscopy instead of test-and-scope (Figure 2C). Maximizing satisfaction in the insurance perspective by choosing prompt endoscopy over test-and-scope would cost 9% more per patient ($1280/patient). From a patient perspective, the costs to improve patient satisfaction over test-and-scope would be $2.19/patient for a 1% satisfaction gain with empiric acid suppression and $1.65/patient with test-and-treat. Prompt endoscopy would incur a $0.40/1% satisfaction gain expenditure from a patient perspective compared with test-and-scope (Figure 2D). Maximizing patient satisfaction in the patient perspective by choosing prompt endoscopy over test-and-scope would cost an additional 0.4% ($10/patient).

Figure 2.

Cost-effectiveness and cost-satisfaction of discrete management strategies for patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia without alarm features in gastroenterology care. Treat-and-scope was the preferred cost-effective strategy from (A) insurer and (B) patient perspectives. Prompt endoscopy was the preferred strategy to maximize cost-satisfaction strategy from (C) insurer and (D) patient perspectives. QALY, quality-adjusted life year.

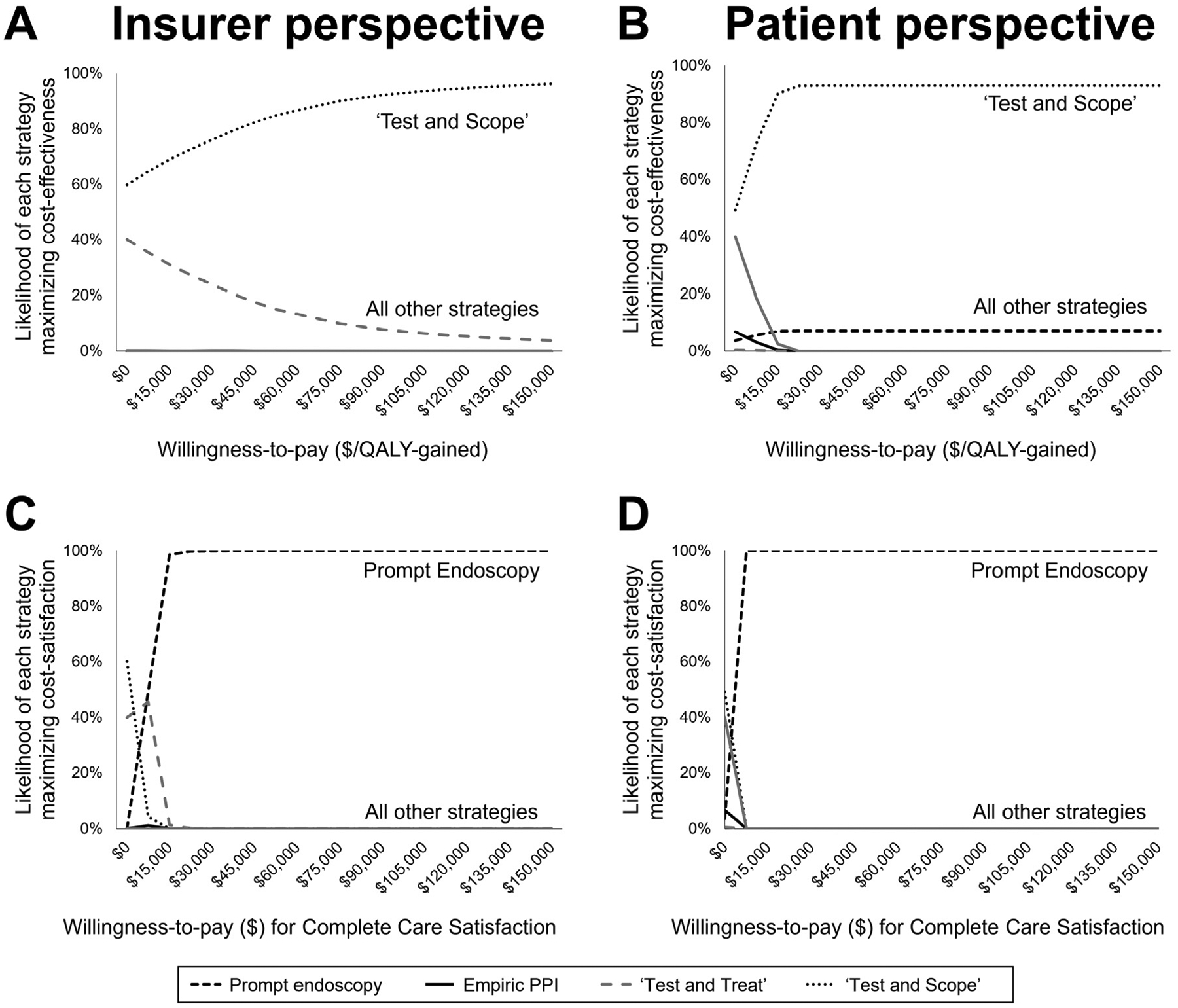

Sensitivity Analyses

In probabilistic sensitivity analysis, test-and-scope was the most cost-effective strategy regardless of willingness-to-pay (Figure 3A and B). Prompt endoscopy was the most cost-satisfactory strategy (minimizing costs and maximizing satisfaction) (Figure 3C and D). These findings aligned between the insurer and patient perspectives. Ranked preferences remained stable in one-way sensitivity analyses for each model input across each pair of competing strategies (Supplementary Figures 1–25) and when stratifying by age (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 3.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses demonstrate treat-and-scope as the preferred cost-effective strategy from (A) insurer and (B) patient perspectives. Prompt endoscopy was the preferred strategy to maximize cost-satisfaction from (C) insurer and (D) patient perspectives. QALY, quality-adjusted life year.

Discussion

This study considers patient satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and costs from key stakeholder perspectives to inform appropriate management of uninvestigated dyspepsia.23,24 Our study design facilitated the exploration of whether these factors may drive the significant divergence between guidelines that advocate noninvasive management strategies for dyspepsia, compared with preferences toward endoscopy in the realities of clinical care. By considering patient satisfaction and out-of-pocket expenses, our study found that management strategies promoting early endoscopy were consistently superior to noninvasive strategies. Prompt endoscopy maximized cost-satisfaction (ie, minimizes costs and maximizes satisfaction). Test-and-scope maximized cost-effectiveness. Findings were consistent across insurer and patient perspectives and in extensive sensitivity analyses.

It is intuitive that patients might find endoscopic rule-out of organic pathology more satisfactory, especially because endoscopy is a safe procedure with which adverse outcomes are rare.25 This fact may relate patients’ fears of potentially severe and life-threatening diagnoses (eg, cancer),26,27 recognizing that 1 in 4 patients with gastric cancer who present with dyspepsia do not feature alarm symptoms.28,29 Although gastric cancer is found in <1% of dyspeptic patients without alarm features, this still represents thousands of patients each year.30 In certain subpopulations, the risk is even higher.31,32 In addition to the benefits of identifying organic pathology early, improved patient satisfaction itself may be associated with improved health outcomes, because it may promote a positive patient-physician relationship, a factor associated with increased treatment response.33,34 Although prior studies have suggested against positive impact of endoscopy on quality of life, updated evaluation in a modern U.S. dyspeptic population is not available.35,36

Costs with endoscopy-based strategies might be mitigated by some combination of decreases in downstream testing and office visits, earlier identification of organic pathology, and earlier consideration for tailoring therapy to endoscopic findings compared with empiric approaches.37 Indeed, published cost studies deemed routine endoscopy-based approaches to incur $80,000 in healthcare expenditures per QALY-gained,38 a threshold for which contemporary health economics studies would now consider cost-effective. For other procedural indications beyond dyspepsia, contemporary movements are toward increasing use of endoscopy, such as recent efforts to develop endoscopy-based gastric cancer screening programs or to follow gastric intestinal meta-plasia in asymptomatic populations where precise definitions for at-risk individuals remain controversial.31,32 Future efforts to conserve costs and limit endoscopies could focus on the value of subsequent endoscopies, rather than the index, among dyspeptic patients with stable symptoms.

That our results correlate with the lived experience of many gastroenterologists does not prove that the factors we have identified explain all variance from guidelines, but it suggests these factors deserve further examination. Uninvestigated dyspepsia is a prime example of the reality that guidelines often diverge with clinical practice.2–4,8–10 Guidelines are developed using standardized GRADE methodology to objectively formulate clinical care recommendations based on strength of the evidence.5,6,39 Traditionally, the evidence base to justify clinical care recommendations relies on objective clinical outcomes of efficacy, safety, and tolerability. However, contemporary guidelines increasingly recognize the importance of value-based preferences that extend beyond evidence-based recommendations and have inherent ties to social determinants of health. These preferences might be driven by costs, or patient satisfaction–ranked preferences depend entirely on the answer to a question: “value to whom?”.40 Recognizing nuances in individual patient interactions, we advocate against the use of guidelines by insurers or health systems to limit potential clinical care pathways without multi-stakeholder input, because this may interfere with physician autonomy and the patient-provider relationship.

Our findings should be interpreted within the context of several limitations that are found in any cost-effectiveness or cost-satisfaction study. First, our study design was intended to identify the preferred initial management strategy for the majority of patients, supported by the robustness of findings in the comprehensive sensitivity analyses across the full range of reasonable model inputs based on available evidence. Thus, in keeping with published guidelines and systematic reviews, it is not intended to inform subsequent management decisions among increasingly smaller patient subpopulations beyond the initial routine strategy. In addition, care decisions for individual patients should consider the full context of individual patient-level factors outside the scope of this study, such as any potential disparity in care related to social determinants of health and race/ethnicity. Our study is also not designed to provide actual cost and outcomes estimates for individual patients or covered populations. Furthermore, data were not available to model the impact of the individual patient-physician relationship on patient satisfaction or treatment outcome. This may represent an area for further research. Second, clinical outcomes data were derived from indirect comparisons among competing management strategies for uninvestigated dyspepsia. We therefore adopted the accepted standard for cost-effectiveness studies of anchoring our data on a recent network meta-analysis, in this case including more than 6000 participants in 15 randomized controlled trials referenced against symptom-based management as a control arm.13,41 Future studies using newer, standardized metrics of clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and quality of life may allow for more detailed evaluation of the drivers of patient preference. Finally, it was not possible to compare strategies on age strata, because data were not available and patients were not randomized on these strata in underlying trials. Yet, because our findings were driven by treatment satisfaction and resultant downstream healthcare utilization and recognizing similar clinical effectiveness regardless of strategy, it is plausible that preference toward endoscopy might hold across the lifespan.

In conclusion, strategies that promote more routine endoscopy to manage uninvestigated dyspepsia appear preferential to empiric acid suppression or test-and-treat strategies from both cost-effectiveness and cost-patient satisfaction perspectives and from both patient and insurer perspectives. Future studies are needed to prospectively identify drivers of strategy selection and patient satisfaction. Value-based transformation efforts should consider “value” from all key stakeholder perspectives and seek to define not only the development of practice guidelines but also their appropriate utilization to promote best practice care.

Supplementary Material

What You Need to Know.

Background

Uninvestigated dyspepsia is an extremely common complaint and reason for referral to gastroenterologists. Management of patients <50–60 years old often diverges from the test-and-treat (test for H pylori and eradicate if present) strategy advocated for in guidelines. The drivers of the discrepancy are not understood.

Findings

Prompt endoscopy maximizes cost-satisfaction from patient and insurer perspectives compared with alternate strategies including empiric acid suppression, test-and-treat, and test-and-scope (test for H pylori and perform endoscopy if present). Test-and-scope maximizes cost-effectiveness. Patient satisfaction appears to drive the discrepancy between guidelines and practice.

Implications for patient care

Value-based transformation efforts should consider stakeholder preferences including patient satisfaction and costs alongside clinical outcomes to inform the optimal management strategy for uninvestigated dyspepsia.

Funding

Dr Chang is supported by a grant from AnX Robotica. Dr Chey has research grants from Commonwealth Diagnostics International, QOL Medical, Salix, and stock options from GI on Demand, Isothrive, and Modify Health. Dr Moshiree is supported by grant support from Bausch Pharmaceuticals and Progenity. Dr Staller is supported by NIDDK K23 DK120945. Dr E. Shah was supported by the AGA Research Foundation’s 2019 American Gastroenterological Association-Shire Research Scholar Award in Functional GI and Motility Disorders.

Conflicts of interest

These authors disclose the following: Dr Ahuja consulted for GI Supply, Takeda, Medtronic, and GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare and has received research support from Vanda Pharmaceuticals and Nestle. Dr Brenner consulted, advised, or spoke for AbbVie, Arena, Alnylam, AlphaSigma, Ardelyx Ironwood, Laborie, Mahana, Salix, Takeda, and Board of Directors of the IFFGD. Dr Chan consulted/advised for Ironwood, Takeda, and Phathom. Dr Chey consulted for AbbVie, Allakos, Alnylam, Arena, Biomerica, Comvita, Everlywell, Gemelli, Ironwood, Isothrive, QOL Medical, Nestle, Phathom, Progenity, Quest, Redhill, Salix, Urovant, and Vibrant. Dr Lembo has consulted for Allakos, Ironwood, Takeda, Bayer, Vibrant, Aeon, Mylan, Shire, Bellatrix, Arena, and OrphoMed. Dr Moshiree has advised Progenity, Intrinsic Sciences, Iron-wood, Allergan, Takeda, Nestle, and Bausch Pharmaceuticals. Dr S. Shah has consulted for Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr Staller has consulted for Anji, Arena, Gelesis, GI Supply, Sanofi, and Shire/Takeda and has received research support from Ironwood and Urovant. Dr E. Shah consulted for GI Supply, Ardelyx, Bausch Health, Takeda, and Mahana. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology at www.cghjournal.org, and at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.003.

References

- 1.Ford AC, Marwaha A, Sood R, et al. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Gut 2015;64:1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiegel BMR, Farid M, van Oijen MGH, et al. Adherence to best practice guidelines in dyspepsia: a survey comparing dyspepsia experts, community gastroenterologists and primary-care providers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:871–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta K, Groudan K, Jobbins K, et al. Single-center review of appropriateness and utilization of upper endoscopy in dyspepsia in the United States. Gastroenterology Res 2021; 14:81–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacy BE, Weiser KT, Kennedy AT, et al. Functional dyspepsia: the economic impact to patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 38:170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, et al. ACG and CAG clinical guideline: management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112:988–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Shaukat A, Wang A, et al. The role of endoscopy in dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82:227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talley NJ, American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association medical position. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1753–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiorenza JP, Tinianow AM, Chan WW. The initial management and endoscopic outcomes of dyspepsia in a low-risk patient population. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:2942–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dugan K, Ablah E, Okut H, et al. Guideline adherence in dyspepsia investigation and treatment. Kans J Med 2020; 13:306–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halasz JB, Burak KW, Dowling SK, et al. Do low-risk patients with dyspepsia need a gastroscopy? use of gastroscopy for otherwise healthy patients with dyspepsia. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2021;5:32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA 2016;316:1093–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD. The Rand/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eusebi LH, Black CJ, Howden CW, et al. Effectiveness of management strategies for uninvestigated dyspepsia: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2019;367:l6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groeneveld PW, Lieu TA, Fendrick MA, et al. Quality of life measurement clarifies the cost-effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori eradication in peptic ulcer disease and uninvestigated dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:338–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez E, Neuman T, Jacobson G, et al. How much more than Medicare do private insurers pay? a review of the literature. Medicare: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020:1–63. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brook RA, Kleinman NL, Choung RS, et al. Functional dyspepsia impacts absenteeism and direct and indirect costs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers US. for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Outpatient PPS. CMS.gov. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalOutpatientPPS. Published 2021. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- 18.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment, hours, and earnings from the current employment statistics survey (national). Databases, tables & calculators by subject. Available at: https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CES0500000003. Published 2021. Accessed June 1, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lofquist D, Lugaila T, O’Connell M, et al. Households and families: 2010. Vol 2010 Census, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Care.com editorial staff. This is how much child care costs in 2021. Care.com. Available at: https://www.care.com/c/stories/2423/how-much-does-child-care-cost/togetthehourlyrate. Published 2021. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- 21.Muennig P, Bounthavong M. Cost-effectiveness analyses in health: a practical approach. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn A, Grosse SD, Zuvekas SH. Adjusting health expenditures for inflation: a review of measures for health services research in the United States. Health Serv Res 2018;53:175–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaney BC, Wilson S, Roalfe A, et al. Cost effectiveness of initial endoscopy for dyspepsia in patients over age 50 years: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Lancet 2000;356:1965–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spiegel BMR, Vakil NB, Ofman JJ. Dyspepsia management in primary care: a decision analysis of competing strategies. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1270–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, et al. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;76:707–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drossman DA, Brandt LJ, Sears C, et al. A preliminary study of patients’ concerns related to GI endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brandt LJ. Patients’ attitudes and apprehensions about endoscopy: how to calm troubled waters. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:0–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fransen GAJ, Janssen MJR, Muris JWM, et al. Meta-analysis: the diagnostic value of alarm symptoms for upper gastrointestinal malignancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:1045–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vakil N, Moayyedi P, Fennerty MB, et al. Limited value of alarm features in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal malignancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2006; 131:390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theunissen F, Lantinga MA, ter Borg PCJ, et al. The yield of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients below 60 years and without alarm symptoms presenting with dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol 2021;56:740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saumoy M, Schneider Y, Shen N, et al. Cost effectiveness of gastric cancer screening according to race and ethnicity. Gastroenterology 2018;155:648–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah SC, Canakis A, Peek RM, et al. Endoscopy for gastric cancer screening is cost effective for Asian Americans in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:3026–3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 2008;336:999–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelley JM, Lembo AJ, Ablon JS, et al. Patient and practitioner influences on the placebo effect in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med 2009;71:789–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegel BMR, Gralnek IM, Bolus R, et al. Is a negative colonoscopy associated with reassurance or improved health-related quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome? Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62:892–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Kerkhoven LAS, van Rossum LGM, van Oijen MGH, et al. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy does not reassure patients with functional dyspepsia. Endoscopy 2006;38:879–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, et al. High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vakil N, Talley N, Van Zanten SV, et al. Cost of detecting malignant lesions by endoscopy in 2741 primary care dyspeptic patients without alarm symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:756–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah ED, Siegel CA. Systems-based strategies to consider treatment costs in clinical practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Value in Health 2013;16:e1–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.