Abstract

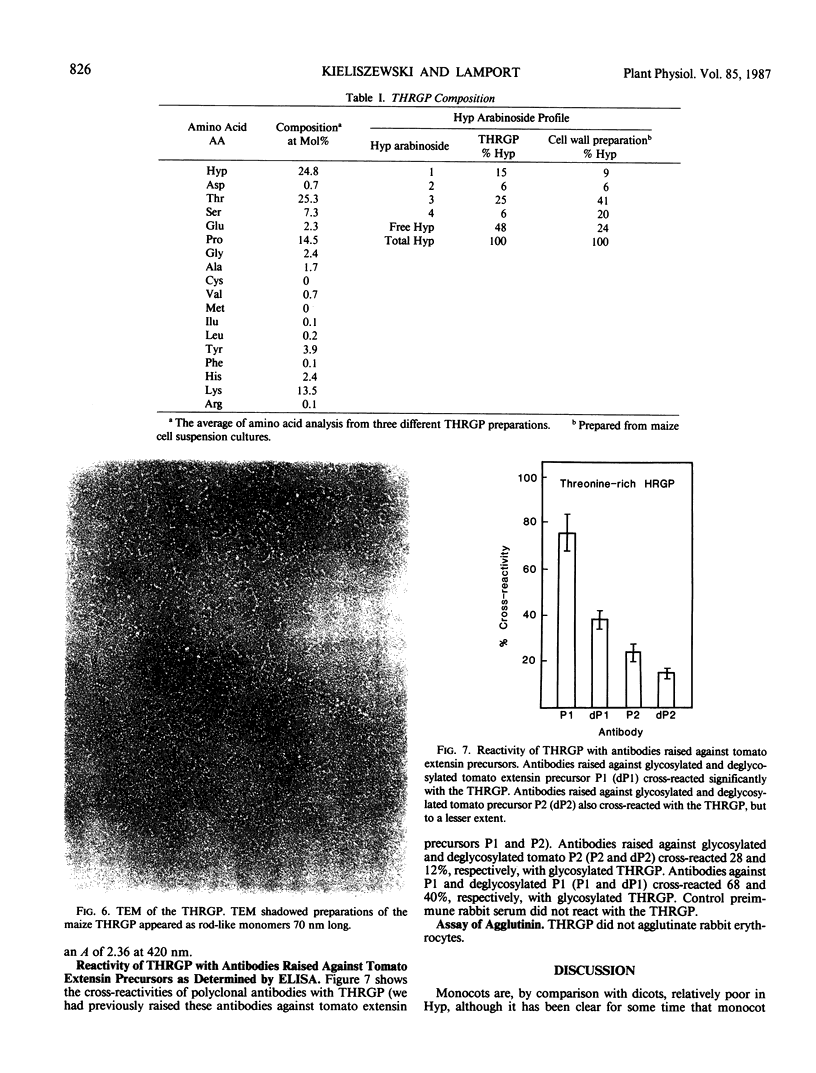

Graminaceous monocots generally contain low levels of hydroxyproline-rich Glycoproteins (HRGPs). As HRGPs are often at the cell surface, we used the intact cell elution technique (100 millimolar AlCl3) to isolate soluble surface proteins from Zea mays cell suspension cultures. Further fractionation of the trichloroacetic acid-soluble eluate on the cation exchangers phospho-cellulose and BioRex-70 gave several retarded, hence presumably basic fractions, which also contained hydroxyproline (Hyp). One of these fractions yielded a pure HRGP after a final purification step involving Superose-6 gel filtration. As this HRGP was unusually rich in threonine, (25 mole%) we designated it as a threonine-hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein (THRGP); it contained about 27% carbohydrate occurring exclusively as arabinosylated Hyp, predominantly as the monosaccharide (15%), and trisaccharide (25%) with 48% Hyp nonglycosylated—a characteristically graminaceous monocot profile. Amino acid analysis confirmed the basic character, and gave a low alanine content. Reaction with Yariv artificial antigen was negative. These characteristics show that the THRGP is not an arabinogalactan protein. On the other hand, antibodies raised against tomato extensin P1 cross-reacted significantly with the THRGP; this cross-reactivity and the above analytical data provide the best evidence to date for the presence of extensin in a graminaceous monocot.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen A. K., Neuberger A. The purification and properties of the lectin from potato tubers, a hydroxyproline-containing glycoprotein. Biochem J. 1973 Oct;135(2):307–314. doi: 10.1042/bj1350307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boundy J. A., Wall J. S., Turner J. E., Woychik J. H., Dimler R. J. A mucopolysaccharide containing hydroxyproline from corn pericarp. Isolation and composition. J Biol Chem. 1967 May 25;242(10):2410–2415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels M. J. Synthesis and secretion of hydroxyproline containing macromolecules in carrots. I. Kinetic analysis. Plant Physiol. 1969 Aug;44(8):1187–1193. doi: 10.1104/pp.44.8.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland R., Karlsnes A. M. A possible role of hydroxyproline-containing proteins in the cessation of cell elongation. Plant Physiol. 1967 May;42(5):669–671. doi: 10.1104/pp.42.5.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engvall E., Perlmann P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Elisa. 3. Quantitation of specific antibodies by enzyme-labeled anti-immunoglobulin in antigen-coated tubes. J Immunol. 1972 Jul;109(1):129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K., Favre M. Maturation of the head of bacteriophage T4. I. DNA packaging events. J Mol Biol. 1973 Nov 15;80(4):575–599. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamport D. T., Miller D. H. Hydroxyproline arabinosides in the plant kingdom. Plant Physiol. 1971 Oct;48(4):454–456. doi: 10.1104/pp.48.4.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach J. E., Cantrell M. A., Sequeira L. Hydroxyproline-rich bacterial agglutinin from potato : extraction, purification, and characterization. Plant Physiol. 1982 Nov;70(5):1353–1358. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.5.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon J. E., Helgeson J. P. Interaction of a hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein from tobacco callus with potential pathogens. Plant Physiol. 1982 Aug;70(2):401–405. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts K., Grief C., Hills G. J., Shaw P. J. Cell wall glycoproteins: structure and function. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1985;2:105–127. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1985.supplement_2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter A. M., Bell J. N., Cramer C. L., Bailey J. A., Varner J. E., Lamb C. J. Accumulation of hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein mRNAs in response to fungal elicitor and infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Oct;82(19):6551–6555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.19.6551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom J. P., Staehelin L. A. Cross-linking patterns in salt-extractable extensin from carrot cell walls. Plant Physiol. 1986 May;81(1):234–241. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler J. M., Branton D. Rotary shadowing of extended molecules dried from glycerol. J Ultrastruct Res. 1980 May;71(2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(80)90098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray W., Boulikas T., Wray V. P., Hancock R. Silver staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1981 Nov 15;118(1):197–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Holst G. J., Varner J. E. Reinforced Polyproline II Conformation in a Hydroxyproline-Rich Cell Wall Glycoprotein from Carrot Root. Plant Physiol. 1984 Feb;74(2):247–251. doi: 10.1104/pp.74.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]