Abstract

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are among the most promising therapeutic platforms in many life-threatening diseases. Owing to the significant advances in siRNA design, many challenges in the stability, specificity and delivery of siRNA have been addressed. However, safety concerns and dose-limiting toxicities still stand among the reasons for the failure of clinical trials of potent siRNA therapies, calling for a need of more comprehensive understanding of their potential mechanisms of toxicity. This review delves into the intrinsic and delivery related toxicity mechanisms of siRNA drugs and takes a holistic look at the safety failure of the clinical trials to identify the underlying causes of toxicity. In the end, the current challenges, and potential solutions for the safety assessment and high throughput screening of investigational siRNA and delivery systems as well as considerations for design strategies of safer siRNA therapeutics are outlined.

Keywords: RNAi, siRNA, Gene silencing, LNP, GalNAc, Safety, Clinical trial, toxicity assessment

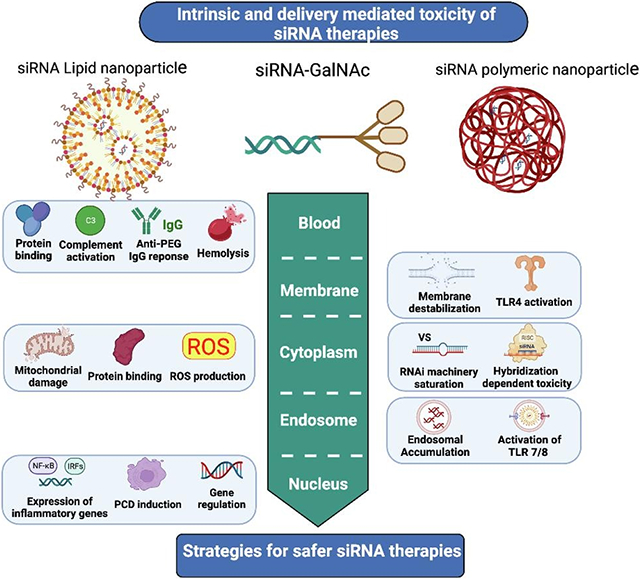

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Since the discovery of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in C. elegans in 1998 [1], siRNAs have become a powerful tool to manipulate gene expression in a sequence-specific manner. Later development of this Nobel Prize winning discovery offered a unique therapeutic platform for targeting disease-associated genes for the treatment of various rare life-threatening diseases as well as some common diseases [2-6]. After two decades of growth and development supported by the significant technological breakthroughs on chemical modifications and delivery platforms [7], the discovery and development of siRNA drugs have run into a fast pace with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of ONPATTRO® (patisiran), the first RNA therapy for the treatment of patients with transthyretin (TTR)-mediated amyloidosis in 2018 [8], also making it the first-ever lipid nanoparticle (LNP) to receive an FDA approval [9]. This breakthrough was followed by another FDA-approved siRNA therapy GIVLAARI® (givosiran, ALN-AS1) in 2019 [10], an N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) siRNA conjugate for the treatment of acute hepatic porphyria (AHP) in adults [11]. Three more siRNA drugs, lumasiran [12], vutrisiran , and inclisiran [13] have been added to the list of the FDA-approved siRNA drugs in recent years and many other siRNA therapies are also currently under clinical investigation [14].

Despite the significant advances in developing siRNA therapies, safety liabilities are among the reasons causing setbacks in the clinical translation of this category of drugs. For instance, CALAA-01, ARC-520, TKM-ApoB, TKM-080301, and revusiran are all among the siRNA candidates that failed in clinical trials due to safety issues despite harboring desired gene silencing potency (see section 4). The root of this problem goes back to the lack of in depth understanding of the potential mechanisms of toxicity of siRNA and the role of delivery mode on the safety profile of investigational siRNAs. Besides, non-predictive preclinical studies and lack of knowledge about the effect of disease complications on biodistribution and toxicity of siRNA drugs are causing the failure of some siRNA drugs at late stages of investigation. Unfortunately, even after years, the underlying cause of the safety failure of some RNA candidates in clinical trials remains unresolved [15, 16]. In this sense, for designing safer siRNA drugs and expediting the clinical translation of potent siRNA candidates, a better understanding of the toxicity mechanisms and potential pitfalls of toxicological assessments of siRNA drugs is crucial.

In this review, a comprehensive discussion of the toxicity mechanisms associated with siRNA and its delivery systems and the approaches to address them is first provided. Then the clinical trials that failed due to the toxicity issues are further delved into in an attempt to determine the underlying causes of the failure. Moreover, potential solutions to address the current obstacles in the toxicity assessment of siRNA and its delivery systems is presented. In the end, based on the knowledge gained from successful siRNA therapies, strategies for designing safer siRNA therapeutics and future perspectives in this era are outlined.

2. Intrinsic toxicity of siRNA molecule

siRNA drugs are among the most promising RNA therapeutics, which can effectively trigger gene silencing by degradation of their sequence-matched target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) [17]. Upon entering the cells, the double-stranded (ds) siRNA, consisting of a guide strand and a passenger strand, is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Consequently, the passenger strand is degraded and argonaute 2 (Ago2) is activated, causing the enzymatic cleavage of the mRNA with a complementary sequence to the guide strand [18].

However, unmodified siRNA molecule harbors intrinsic immunogenicity and toxicity which can cause limitations to its clinical translation. In this section the immune stimulation and different mechanisms of toxicity associated with siRNA molecule are discussed and potential design strategies to avoid them are presented.

2.1. Immunogenicity

As part of the antiviral defense mechanism, our innate immune system recognizes exogenous RNAs via specific receptors that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) [19]. For siRNA therapeutics, however, this mechanism is responsible for their immunogenicity and causes major safety concerns to their clinical application [20].

Different pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are involved in recognizing RNA molecules and can cause potent immune responses in the form of secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and type I interferon (IFN). The excessive cytokine release and subsequent inflammatory syndromes can lead to organ damage and even death in severe cases [21]. PRRs are categorized into two groups: (1) the cytoplasmic PRRs, consisting of RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and ds RNA-activated protein kinase R (PKR), and (2) the endosomal PRRs containing toll-like receptor (TLR) 3, TLR 7, and TLR 8 [22, 23].

Different factors such as siRNA structure, sequence, length, and delivery mode play critical roles in the immunogenicity of siRNA and its recognition by PRRs. For instance, while TLR 3 is activated by ds siRNAs [24], TLR 7/8 are susceptible to both single-stranded (ss) and ds siRNAs [25], and even to a higher degree to the ss siRNAs [26]. Also, TLR 7/8 recognize siRNAs in a sequence-dependent manner [25]. For example, the U-rich sequence was shown to induce proinflammatory cytokine secretion by activating the TLR 7/8 in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [27]. It is also established that GU-rich motifs activate TLR 7/8 in dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages, and lead to the activation of NF-κB and subsequent secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL) -6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [28]. The length of siRNA is another important factor since even in the presence of the immunostimulatory motifs, a minimum length of 19 bases is required for induction of an immune response [29, 30]. According to a recent study, siRNA duplexes 23 nucleotides long can induce IFN responses and cell death in culture [31].

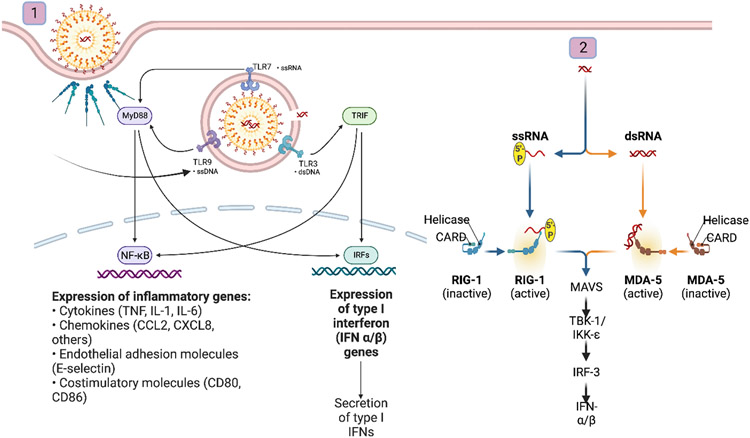

The observed differences in immunogenicity of naked siRNA and siRNA-loaded carriers highlight the role of siRNA delivery mode in activation of immune system [29]. As depicted in figure 1, nanocarriers may trigger immunogenicity caused by siRNA molecules by exposing them to endosomal TLRs through endosomal uptake pathways[25, 32]. Complement activation is another mechanism by which oligonucleotides (ONTs) can activate the innate immune system. There has been reports of complement activation by high phosphorothioate (PS) content antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), due to their interactions with proteins in the alternative pathway of complement [33]. Nevertheless, complement activation observed by siRNA therapies is not always attributed to siRNA itself, but due to their delivery systems as cationic lipid NPs can trigger classical pathways of the complement system [34].

Figure 1.

Effect of siRNA delivery vehicles on triggering the immunostimulation of loaded siRNA. (1) Nanocarriers expose siRNA to TLR3, 7/8 upon their endosomal uptake and activate NF-kB and IRFs pathways involved in the inflammatory response. (2) Upon endosomal escape, released siRNA can stimulate cytoplasmic PRRs and activates RIG-1/MDA-5 pathways involved in type I IFN secretion. Created with BioRender.com

A series of chemical modifications were introduced to reduce the immunogenicity of ONTs [35]. For instance, it is established that the substitution of 2'-OH uridine or guanosine nucleosides with 2'-Omethyl (2’-OMe), 2′-Fluoro (2′-F), or 2'-H significantly reduces RNA immunogenicity [26, 36]. Altogether, modified siRNA structures are showing good tolerability in clinic with some infusion-related interactions in the site of injection [37].

2.2. Hybridization-dependent toxicity

Hybridization-dependent side effects occur downstream to RISC loading and result from the hybridization of siRNAs with either unintended or intended transcripts, referred to as off-target and on-target side effects, respectively.

2.2.1. Off-target toxicity

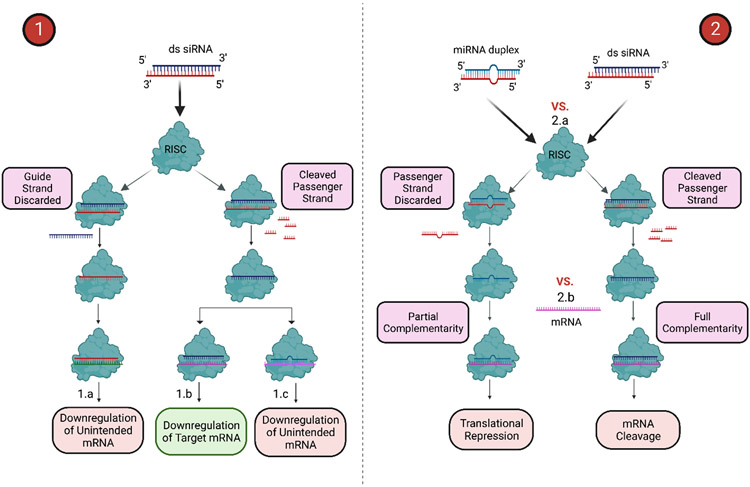

Most ONT-based therapies, including siRNAs, can exert hybridization-dependent off-target effects by inadvertent silencing of mRNAs with partial complementarity to the antisense strand, which are illustrated in figure 2. The first report of the off-target gene regulation by a siRNA revealed the cross-reactions of the siRNA with targets of partial similarity [38]. Early studies showed that as much as 3-4 base mismatches and the GU wobble mismatches in the siRNA could downregulate unintended mRNAs via RNA degradation and repression of translation [39]. Further studies demonstrated that the off-target transcript silencing by siRNAs is caused mainly by the complementarity of 5’ end of the siRNA consisting of 7 nucleotides (seed region) with the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of the transcripts [40, 41], a phenomenon referred to as the microRNA (miRNA)-like off-target effect [42]. Later it was found that the thermodynamic stability and Watson-Crick pairing of the seed duplex formed between the seed and target are essential to the sequence-induced off-target toxicities [43]. The base pairing in the seed region was also reported to be a primary factor for siRNA off-target effects; however, the non-seed regions and target sequences were also shown to play a role; as it was observed that the melting temperature in a subsection of the non-seed region, and the GC content of the target sequence, could affect the degree of siRNA off-target effects [44].

Figure 2.

(1) siRNA-induced hybridization-dependent toxicities and (2) Perturbation of RNAi machinery. (1.a) Off-target side effects caused by RISC loading of passenger strand leading to the downregulation of unintended mRNA. (1.b) Downregulation of intended mRNA by guide strand, which is the desired outcome only if happening in desired cells, otherwise will be the source of on-target toxicities. (1.c) Downregulation of partial complementary mRNA due to miRNA-like off-target effects. (2) Competition of exogenous siRNA and endogenous miRNA on (2.a) RISC loading and (2.b) mRNA sites, leading to the saturation of miRNA processing pathways due to siRNA coarse dosing and subsequent global effects on RNAi machinery. Created with BioRender.com

While siRNA design algorithms exploit the seed region sequences with minimal complementarity to 3'-UTRs to minimize the miRNA-like off-target effects [45], partial similarity with some 3'-UTRs is still inevitable [46]. Nonetheless, some chemical modifications have proven to mitigate these off-target effects. For instance, the 2'-OMe substitution of guide strand at position 2 [47] and a modification at unlocked nucleobase analogs (UNAs) in passenger and guide strands [48], or into position 7 of the siRNA [49], as well as incorporation of locked nucleic acid (LNA) [50, 51] have shown to be highly efficient in reducing the siRNA off-target effects. Also, altering the seed region sequence, or introducing a destabilizing glycol nucleic acid (GNA) nucleotide into it had been shown to alleviate the hepatotoxicity caused by GalNAc conjugated siRNAs in rats [52].

The other mechanism of off-target effects originates from the assembly of the passenger strand to the RISC complex, causing the sense strand-mediated off-target gene silencing (illustrated in figure 2). Some chemical modifications including 5'-biotinylation of sense strand [53, 54], 5-nitroindole modification at position 15 of the sense strand [55], as well as designing small internally segmented interfering RNAs [56], creating Dicer substrate siRNAs [57], and asymmetric shorter-duplex siRNAs [58] have been successfully exploited to reduce the passenger strand RISC assembly.

2.2.2. On-target toxicity

Hybridization-dependent side effects of siRNAs are not always caused by the off-target silencing of partial complementary sequences but can also occur due to knocking down the target mRNAs. In this case, toxic effects result either from the exaggerated pharmacological effects in the target cells or from the on-target effects on unwanted cells. The first category of on-target toxicity may be observed in preclinical toxicological studies of supratherapeutic doses of siRNAs. For instance, fitusiran, a GalNAc conjugated siRNA targeting antithrombin to promote hemostasis in hemophilia, was reported to induce thrombosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation in non-diseased animals at exaggerated doses [59]. Similarly, the mRNA loaded LNP encoding the protein for human erythropoietin (hEPO) induced hematopoiesis in rat liver, spleen, and bone marrow at exaggerated doses [60]. However, it should be noted that only predictable "mechanism-related" toxicities at supratherapeutic exposures can be attributed to on-target effects. In fact, off-target effects are even more sensitive to siRNA concentrations than on-target effects [43] and can be the underlying cause of the toxicity at high doses. For instance, the observed hepatotoxicity in rodents at exaggerated doses of siRNA-GalNAc conjugates originated from off-target toxicities [52].

The other category of on-target toxicities is the knockdown of the target RNA in the undesired cells. A relevant example is anticancer therapeutic MRX34, a liposomal mimic of miR-34a, which has been shown to accumulate not only in cancerous cells but also in immune cells, in which miR-34a plays a critical role [61]. Following the uptake of this drug by immune cells, a significant shift in chemokine secretion by macrophages and T cells resulted in reduced immunity in favor of tumor growth [62]. Another relevant example is the potential uptake of anticancer agent AEG35156, an XIAP targeting ASO, by glial cells or neurons and the subsequent downregulation of XIAP in these cells, causing peripheral chemotherapy-induced neuropathy in patients [63].

2.3. Saturation of RNA interference (RNAi) machinery

siRNA therapeutics can also affect the expression of undesired genes in a sequence-non-specific manner. This effect is exerted via the saturation of siRNA machinery and the subsequent effects on endogenous miRNA processing. The first report of such an effect was the liver toxicity and death in mice caused by overexpression of short hairpin RNA (shRNAs) in hepatocytes [64]. It was revealed that the overdosing of shRNA had saturated the exportin 5, an enzyme also necessary to export pre-miRNAs from nucleus to cytoplasm, leading to the global downregulation of miRNAs in hepatocytes. However, in the case of siRNA and miRNA therapeutics that enter the RNAi pathway in later steps than shRNA, the saturation occurs in factors downstream to exportin 5 in the miRNA processing. For instance, the exogenous siRNAs and miRNAs can compete with endogenous miRNAs for RISC, other downstream factors, or even binding sites on the mRNAs and affect the global gene regulation (illustrated in figure 2) [65]. In this case, the upregulation of undesired genes can occur concurrently with the knockdown of the target transcripts [66]. Also, in a mathematical modeling, it was explained that the changes in the miRNA concentrations could explain the observed unusual positive effects of miRNAs on their targets. It was revealed that the positive net effects of the miRNAs on transcripts that were supposed to be downregulated resulted from the competition of miRNAs in a multi-miRNA multi-target environment [67].

These studies underscore the importance of dose adjustment in siRNA therapies to prevent the saturation of cellular RNAi machinery and the subsequent global effects on miRNA processing caused by siRNA coarse dosing.

3. Delivery-mediated toxicity of siRNA therapies

Despite its great potential, the research path in developing siRNA therapeutics has been replete with huge setbacks due to the issues in siRNA stability, specificity, uptake, toxicity, and delivery [68-70]. During the past years, extensive efforts aiming to improve potency and safety of siRNA therapeutics have led to significant advances via siRNA chemical modifications, conjugation, and exploitation of delivery vehicles [71]. Delivery strategies of siRNA, which are essential for improving its cellular uptake, are either particulate based or chemically conjugated moieties. However, these systems can induce unwanted immune stimulation and toxicological events. Considering the transient nature of the RNAi activity and the frequent treatment regimen for chronic diseases, the risk of cumulative toxicity induced by delivery vehicles becomes more accentuated [72]. This section will be covering the toxicity issues associated with polymer and lipid-based NPs and GalNAc-siRNA as the most important delivery strategies used for siRNA so far.

3.1. polymer-based carriers

Polyethylenimine (PEI), poly(l-lysine) (PLL), chitosan, and poly (beta-amino ester)s (PBAEs) are all among cationic polymers frequently used in the delivery of RNAs [73]. Besides, polycationic dendrimers, cyclodextrin, and modified poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs are other widely used RNA delivery vehicles [74-77].

3.1.1. Immunogenicity

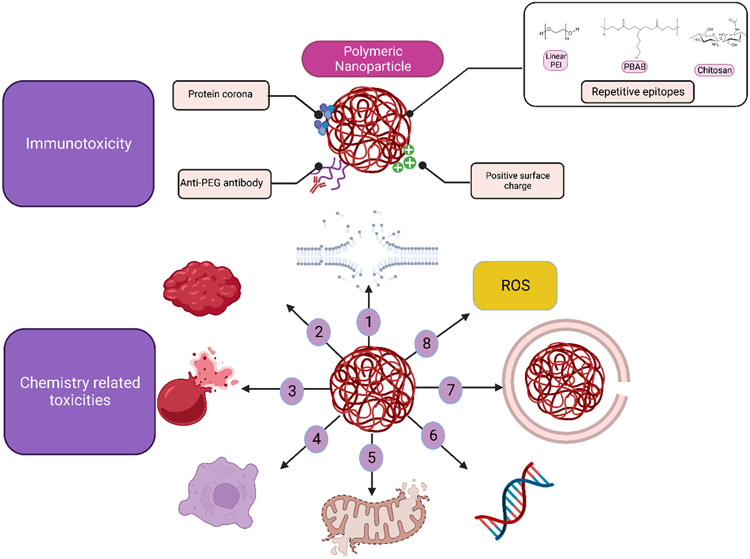

Immune response to polymeric NPs happens because of the recognition of molecular patterns on the surface of NPs by immune system. These molecular patterns either originating from the NP structure or its protein corona, are detected by PRRs of the immune system. For instance, the repetitive epitopes on the surface of the polymeric NPs tend to trigger complement activation and amine-rich coatings such as PEI, are often associated with enhanced phagocytosis due to the higher interaction with opsonin [78]. Figure 3 illustrates the mechanisms of immunogenicity induced by polymeric NPs.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of immune activation and toxicity induced by polymeric siRNA delivery vehicles. (1) Activation of innate and adaptive immune system by polymeric nanocarriers: Molecular and charge patterns as part of polymer structure or due to the protein corona can cause complement activation and anti-PEG antibodies can be produced against PEGylated carriers . (2) Potential toxicity mechanisms of polymeric siRNA delivery vehicles: Cell membrane destabilization(1), erythrocyte aggregation (2) and hemolysis (3), necrotic cell death(4), mitochondrial depolarization (5), gene regulation (6), lysosomal disruption (7), and ROS generation (8). Polyethylene glycol (PEG), poly(ethylenimine) (PEI), and poly(beta-amino-ester) (PBAE).Created with BioRender.com

Many physicochemical factors, which can affect the formation of protein corona on the surface of NPs such as size, shape, state of aggregation and surface chemistry can determine the degree of immunogenicity of the particle. For instance, size of the PLGA NPs was shown to play a role in induction of proinflammatory response, with larger PLGAs being able to activate the NF-κB pathways [79]. Furthermore, positively or negatively charged NPs surface is more prone to interact with proteins and induce complement activation compared to neutral surfaces [78]. Besides, positively charged particles can trigger inflammatory response by induction of oxidative stress as has been reported that airway exposure to PEI NPs could generate immune responses via oxidative stress-induced T helper (Th) 2 cytokines secretion [80]. The molecular weight (MW) of polymers is also a factor in determining the interaction with immune system as there has been report of complement activation-related pseudo allergy (CARPA) upon intravenous administration of high molecular weight PEI (25 KDa) in a swine model [81]. One of the strategies used for reduction of opsonization and immune activation by NPs is PEGylation, which can help in minimizing interactions with proteins by surface neutralization and steric hinderance. For instance, the severe inflammatory responses caused by PEI-based NPs used for pulmonary delivery of siRNAs in mice were shown to be alleviated by hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG) modifications [82]. However, PEGylation can induce immune responses in some cases such as reports of accelerated blood clearance (ABC) with PEGylated NPs due to the unexpected immunologic response to the PEG moiety [83]. This phenomenon not only affects the half-life and efficacy of these therapeutics but can also be responsible for hypersensitivity and immune activation in hosts. In this sense, the immunogenicity induced by cationic polymeric NPs, as siRNA delivery systems, is an important factor, which should be thoroughly investigated in the preclinical toxicity assessments.

3.1.2. Chemical toxicity

Polycationic polymeric NPs have been widely used for delivering nucleic acids. One of the important properties of these carriers is the N:P ratio which is related to the ratio of cationic nitrogen atoms in these carriers to the anionic phosphate atoms in the nucleic acid [84]. Carriers with N:P ratio of higher than 1, have a net positive charge, which enables them to bind to the negatively charged serum and intracellular proteins, a mechanism related to their toxicological effects [85]. Polycationic polymers can interact with phospholipids in the cellular membrane, resulting in membrane destabilization both in blood cells and intracellular organelles such as mitochondria [85]. For instance, the major reason of acute toxicity of PEI-PEG siRNA NPs was attributed to the induction of erythrocyte aggregation, an effect which was dependent on N:P ratio, particle size, and degree and pattern of PEGylation [86].

Membrane disruption is a major toxicity concern for polycationic particles since it can cause necrotic cell death. The mechanism of membrane destabilization by cationic nanoparticles is still under debate. One of the theories proposed by Vaidyanathan et al., is that the portion of the polycations not actively attached to the siRNA, can act as surfactants and make pores in the cellular membrane by intercalation into the lipid membranes, which can act both as cellular uptake and endosomal escape strategy [87]. The other proposed mechanism is the polycations causing the hydrolysis of phospholipids by acting as proton transfer catalysts, thus inducing the formation of inverted hexagonal phases in the membrane [88]. The latter hypothesis has been reported to be the major mechanism of membrane disruption by Monnery et al., based on the observations of PEI-induced acid catalyzed hydrolysis of lipidic phosphoester bonds in 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) liposomes in vitro [89].

There are multiple reports indicating that the toxicity of polycations is positively correlated with their MW [89, 90]. Besides, the charge density and structural properties such as linear or branched play major roles in the toxicity of polycations [90]. PEGylation of cationic polymers as well as structural modifications such as introduction of negatively charged groups to polymeric structure, have shown to be effective in lowering the toxicity of these carriers [86, 91, 92]. While measuring the toxicity of polycations, Monnery et al., outlined an important consideration which was measuring the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) along with the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay [89]. MTT assay on its own can be a misleading measurement since at earlier timepoints, the repair response of cell to membrane destabilization can lead to increased mitochondrial activity of cells, which can be mistakenly interpreted as a non-toxic measurement.

While the initial effects of cellular membrane disruption cause necrotic cell death, Moghimi et al., showed that the second phase of toxicity by linear or branched PEI happens after the pore formation in the outer mitochondrial membrane, causing the release of proapoptotic cytochrome c, leading to mitochondrial depolarization and eventual apoptotic cellular death. Mitochondrial depolarization can also lead to generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [93].

The other concern with NPs is the lysosomal dysfunction, which might be caused because of NPs uptake, sequestration, and degradation by endocytic pathways. Lysosomal dysfunction can happen via two different mechanisms. The first mechanism is the lysosomal rupture by proton sponge effect observed in cationic polymers which is essential to the endosomal escape of the NPs and their gene silencing efficiency. Polyamidoamine (PAMMAM) dendrimers, PEI, cationic polystyrene NPs are known to result in excessive proton pump activity and osmotic swelling [94, 95]. The other mechanism of lysosomal dysfunction is via accumulation of unmetabolized NPs in the lysosome leading to perturbation of intracellular trafficking and signaling.

Furthermore, there are reports of the ability of NPs to affect gene expression in cells. An in vitro study showed that cationic polypropylenimin (PPI) dendrimers could affect the expression of endogenous genes involved in apoptosis and cytokine signaling [96]. In another study, PEI and to a lesser degree, PEG-PEI were shown to activate apoptotic and inflammatory genes in a cell line- and concentration-dependent manner [97]. In the same study, the increase in target gene expression was not due to the siRNA silencing activity but, in fact, in response to the triggered signal by PEG-PEI. In this sense, understanding the genomic signature of siRNA delivery vehicles is essential both in aiding the correct interpretation of therapeutic results and in engineering platforms with minimal toxicogenomic effects [97]. Figure 3 illustrates the chemistry-related toxicities of polymeric NPs.

3.2. Lipid-based carriers

The other class of RNA delivery vehicles is lipid and lipid-based NPs consisting of liposomes and LNPs. FDA-approved products, patisiran (LNP-siRNA) and anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (LNP-mRNA) belong to this revolutionary class of nanomaterials [98]. Despite their phenomenal efficacy in delivering RNA payloads, this category of nanomaterials is also prone to exert immunogenicity and toxicity, which will be the focus of this section.

3.2.1. Immunogenicity

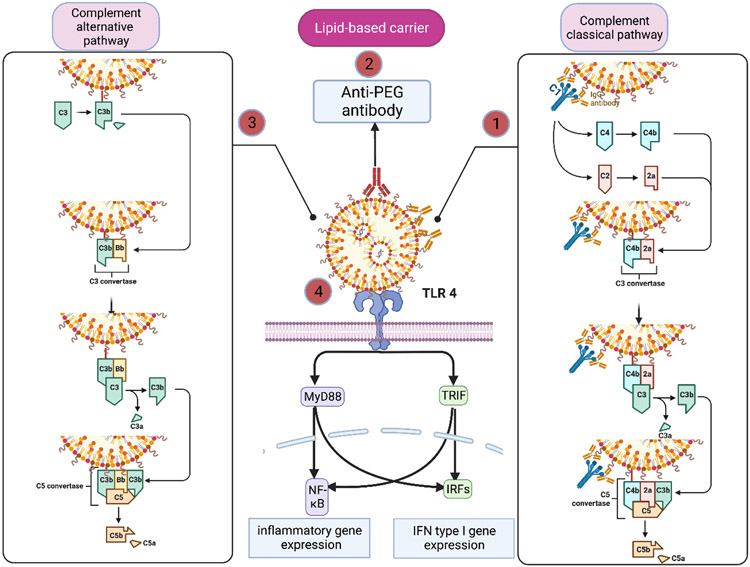

TLR-ligands on the surface of lipid-based NPs such as LNPs and liposomes can stimulate B cells leading to production of antibodies. For instance, there has been reports of Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM production against phosphate and sulphate esters, cholesterol components, or other epitopes such as apolipoprotein H present on the surface of lipid-based nanomaterials [99-101] . Upon the interactions of antibodies with lipid-based NPs or adsorption of C-Reactive Protein on their surface, these materials can activate the classical complement pathway [102]. There is also evidence of complement activation via lectin mediated pathway by liposomes containing phosphatidylinositol or mannose [103, 104]. Furthermore, cationic liposomes or the Fab portion of Antibody-bound liposomes can interact with proteins of the alternative complement pathway [104]. In monkeys, parenteral administration of cationic LNPs was associated with complement activation [60]. The mechanisms of immune activation by lipid-based carriers are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Pathways of immune activation by lipid-based siRNA delivery systems. (1) Antibodies produced against components of lipid-based NPs can activate the classical pathway of complement. (2) Also, antibodies can be produced against the PEG moiety in lipid-based NPs which can cause complement activation or in severe cases can lead to CARPA. (3)Cationic lipid-based NPs or the Fab portion of Ab-bound NPs can interact with proteins of the alternative complement pathway. (4) Lipid-based carriers can directly activate TLR4 and trigger the type I IFN response and secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α. Created with BioRender.com

Lipid-based NPs can also induce a proinflammatory response by immune system. The systemic administration of positively charged LNPs induces type I IFN responses and upregulates Th1 cytokines such as IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α via TLR 4 activation in immune cells [105]. Besides, liposomal siRNA delivery vehicle, LNP201, consisting of cationic lipid CLinDMA, was shown to induce pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 in vivo [106]. In other study, it was reported that the empty LNPs induced maturation of monocyte derived dendritic cells (MDDCs), upregulated CD40 and eventually caused production of type I IFN response [107]. Also, it is known that lipoplexes can induce an antiviral response by inducing type III IFN secretion. In an interesting report, this response was exploited to limit off-target accumulation of subsequently administered NPs for cancer treatment [108]. The authors postulate that IFN-λ produced after injection of lipoplexes will be able to tighten healthy epithelium and thus prevent deposition of NPs administered afterwards. However, the tumor microenvironment won’t go through the tightening event due to the immunocompromised microenvironment, which will lead to the accumulation of NPs in the tumor issue [108]. This strategy can be used for enhanced accumulation of siRNA delivery systems for cancer treatment.

Multiple attempts were made to alleviate the immunotoxicity of lipid-based NPs including premedication or co-administration of dexamethasone [106], or its prodrugs with the possibility of concurrent loading into LNPs [109], and use of Janus kinase (Jak) inhibitors [110]. One of the widely used strategies to reduce the immunotoxicity of lipid-based NPs is PEGylation. As mentioned before, there is evidence regarding immune activation caused by repeated administration of PEGylated nanocarriers [85, 111]. It was reported that after systemic administration of PEGylated liposomes in pigs, there was an elevation of anti-PEG IgM in the blood that, upon binding to the PEGylated liposomes, was able to activate complement and cause severe hypersensitive reactions and CARPA [112]. Evidence shows that incorporating cleavable PEG-Lipids could circumvent the immune response to PEGylated liposomes [113, 114].

3.2.2. Chemical toxicity

Cationic lipid-based NPs are known to induce cytotoxicity due to their positive surface charge [85] [115]. Cationic lipids can act as surfactants and cause poration and destabilization of cellular membrane [116] . Soenen et al., reported that cationic lipid transfer from liposomes to the cell membrane is potentially the main mechanism of cell membrane destabilizations as high curvature of nano-sized liposomes promotes release of cationic lipids and their transfer to cell membrane [115]. The other mechanism of membrane damage is attributed to the protein kinase C (PKC) inhibition observed with some cationic cholesterol derivatives [117]. Besides, the rupture of lysosomal membrane due to the proton sponge effect is another toxicity mechanism by cationic lipids [118].

The other major toxicity mechanism of cationic lipid NPs is production of ROS, which can form in the presence of cationic materials. Contrary to negatively charged and neutral liposomes, positively charged liposomes can cause oxidative stress-induced pulmonary toxicity, highlighting the role of positive charge in generating ROS [116]. Intracellular ROS at high levels can react with a wide range of cellular macromolecules, including DNA, proteins, and membrane lipids, which could ultimately activate a number of molecular signaling pathways [119].

A study by Wei et al.,[120] have reported another mechanism of toxicity induced by cationic liposomes. The authors have shown that the cationic liposomes can impair Na+ /K+ -ATPase and cause the exposure of mitochondrial DNA which can subsequently initiate inflammatory responses and lead to the necrotic cell death. Another mechanism of cytotoxicity of siRNA delivery vehicles involves altering cellular gene expression [121, 122]. Microarray studies show that the cationic lipids lipofectin and oligofectamine altered the expression of 27 genes involved in different cellular pathways such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death (PCD), thus leading the human epithelial cells toward early apoptosis [123].

Since positive surface charge plays a critical role in cationic lipids toxicity, ionizable cationic lipids with neutral surface charge in circulation and positive charge in acidic endolysosomal compartments, are among the most well-tolerated carriers for RNA payloads [124]. However, these systems are not completely toxicity-free. In addition to the abovementioned, the specific toxicity of nanocarriers should be noted as many inert materials can become significantly more reactive when downsized to the nanoscale, most likely due to the dramatic increase in their total surface area. This increase in surface area, causes more extensive interactions between these materials and biological systems, resulting in organ, tissue, and cell damage and the manifestation of nanotoxicity [125].

In an attempt to elucidate the mechanism of hepatotoxicity of ionizable LNPs (iLNPs), it was shown that accumulation of LNPs in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) caused the proinflammatory cascade response, leading to the observed hepatotoxicity [126]. This study also highlighted that effective hepatocyte targeting by GalNAc conjugates could prevent the accumulation of LNPs in other liver cells, thus avoiding hepatotoxicity. In this sense, investigating the intrahepatic distribution of LNPs becomes essential from the perspective of efficacy and safety. A review of the intrahepatic distribution of LNPs as a function of their lipid composition and dosing can be found elsewhere [127]. In order to decrease the accumulation of LNPs in tissues to enhance their safety profile, a practical approach is to design biodegradable LNPs with rapid hepatic clearance which is commonly achieved via introducing ester bonds to the lipid structure [128]. Nevertheless, Da Silva et al., proposed an ester-independent design rule which can improve the tolerability of ionizable lipids [129]. The authors have reported that substituting the racemic ionizable lipids with steropure ionizable lipids can enhance both the efficacy and safety of RNA loaded LNPs. This strategy is particularly valuable since including ester bond might decrease the activity of several potent but relatively toxic lipids causing the reduction of the diversity of future lipids.

3.3. GalNAc conjugates

Significant advances in the chemical modifications of siRNA structure have greatly reduced the immunogenicity of siRNA and have significantly stabilized siRNA against degradation by RNase. siRNA conjugates are developed to enable the targeting and cellular uptake of chemically modified siRNA. Although there are various efforts for extrahepatic delivery of siRNA [130], GalNAc conjugates used for targeting hepatocytes are by far the most successful platforms with four FDA approved products. Tris-GalNAc conjugates target asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) on hepatocytes which enable their rapid endocytosis [131].

One of the fundamental differences between particulate siRNA and siRNA conjugates is that in the former siRNA is encapsulated inside a particle while in the later siRNA molecule is directly exposed to the physiologic environment. In this sense, it is paramount to minimize the interactions of siRNA with serum proteins in siRNA conjugates to avoid potential toxicities associated with siRNA structure. In the case of siRNA conjugates, number of PS in the backbone of siRNA is a double edged sword; on one hand, PS content enhances half-life of siRNA by binding to plasma proteins and thus increasing its renal elimination time and ultimately increasing its intracellular accumulation [132, 133]. On the other hand, PS content enables binding of siRNA to proteins in the alternative complement pathway and can induce activation of innate immune system. Besides, PS content in ONTs, is associated with thrombocytopenia which can happen as a result of binding of ONTs to platelet proteins such as receptor glycoprotein VI (GPVI) and platelet factor 4 (PF4) [134]. Furthermore, nonspecific binding of high PS content ONT to cellular proteins my also negatively affect the protein structure, function, and localization [135-138].

Apart from the siRNA, potential of the toxicity of GalNAc moiety should not be overlooked. For instance, there is a hypothesis that the neuropathy induced by revusiran, might have been caused by GalNAc induced demyelination since there has been report of Guillain–Barre syndrome in some patients treated by exogenous gangliosides [139].

One of the other important considerations in GalNAc-siRNAs is the possibility of saturation of ASGPR in high doses which can affect the biodistribution of these compounds. For instance, a single dose of 10 mg/kg of a novel GalNAc -siRNA showed 2-fold greater accumulation in kidney than liver, while even higher doses of 30 mg/kg fractioned in multiple doses didn’t show higher kidney accumulation [140]. In this sense, dose adjustments to avoid accumulation of GalNAc conjugates in kidney is an important factor.

GalNAc-conjugated siRNAs are also known to have a long-term silencing ability in humans which is due to the accumulation of degradation-resistant siRNA in the acidic intracellular compartments, serving as a depot for these molecules [130]. Although the superior durability and hence fewer dosing frequency is a desirable characteristic, the cytotoxic effects of siRNAs on dysregulation of endogenous endocytic processes via its effects on endocytic vesicles and proteins should not be overlooked [52]. Therefore, careful examination of the long-term toxicities of GalNAc-conjugated siRNAs is highly warranted.

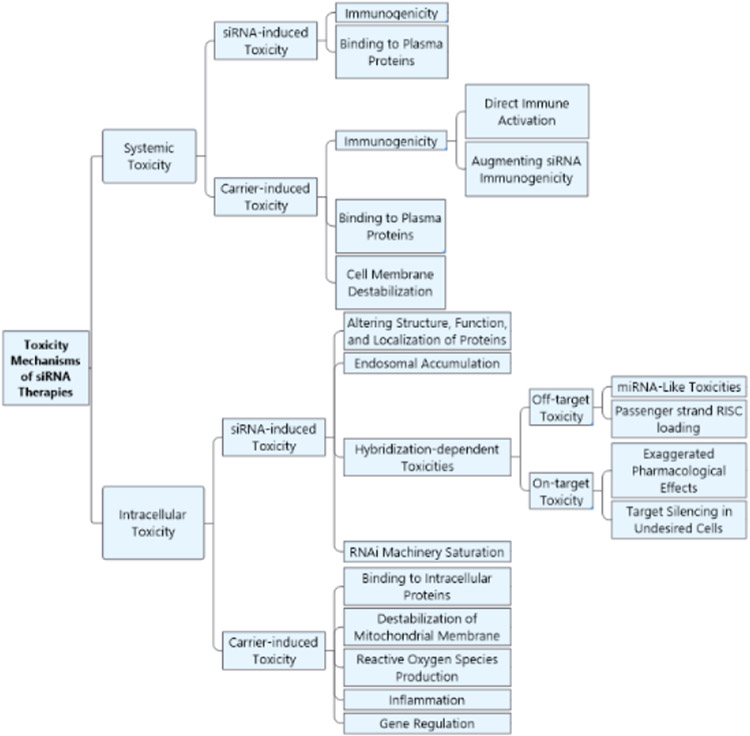

The mechanistic toxicity of siRNA and siRNA delivery systems are summarized in figure 5.

Figure 5.

Summary of toxicity mechanisms of siRNA therapies.

4. Case studies: Toxicity issues in clinical trials of siRNA therapeutics

In this section, we analyze clinical studies of different siRNA therapies that encountered toxicity issues or were terminated because of safety concerns to identify the cause of their toxicity.

4.1. CALAA-01

CALAA-01 is a targeted nanocomplex containing an anti-R2 siRNA to treat solid tumors developed by Calando Pharmaceuticals. It consists of a non-chemically modified siRNA, a cyclodextrin-based cationic polymer, a stabilizing agent (AD-PEG), and a tumor-targeting agent containing the human transferrin protein. The phase 1 clinical study of CALAA-01 (NCT00689065) consisted of 2 cycles: phase 1a with IV administration of a 30 mg/m2 dose of the siRNA, and a phase 1b study after a one-year gap, with a modified dose schedule (starting from 18 mg/m2). In phase 1a, CALAA-01 caused dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) in 2 patients, who were immediately discontinued from the study. Phase 1b, started with a lower dose to potentially reduce the innate immune response, but unexpectedly caused DLTs in two patients leading to the termination of the study [141]. Preclinical toxicity studies of CALAA-01 did not fully correlate with clinical studies, as liver and kidney toxicities were observed in animals but not in humans. However, the hematology data in animals and humans were in good agreement with clinically insignificant dose-dependent platelet count decrease and decline in red blood cells (RBCs), except for the coagulation values, which were reduced in monkeys but not in the rat model and humans. The preclinical studies with delivery vehicles alone showed that in all the mentioned toxicities, including hypersensitivity (the main adverse effect in humans), the culprit was probably the delivery vehicle rather than siRNA. This conclusion is consistent with toxicity reports with other cationic polymers, which were discussed in section 3.1. Furthermore, the 18 mg/m2 dose was well tolerated in phase 1a, but not in phase 1b. This was probably due to the stability of the delivery vehicle and the possibility that nanoparticles could agglomerate during the 1-year gap between phase 1a and 1b.

4.2. ARC-520

ARC-520 is cholesterol targeted siRNAs with a polymer-based excipient (ARC-EX1), developed by Arrowhead pharmaceuticals, targeting hepatitis B viral covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) in patients with chronic hepatitis B. ARC-520 consists of two siRNAs conjugated with cholesterol for enhanced delivery to hepatocytes, and ARC-EX1 delivery system enabling the endosomal escape [142]. The ARC-EX1 is a dynamic poly conjugate (DPC) technology, in which a membrane-active polymer is reversibly masked with the shielding agent PEG and a liver targeting agent such as N-acetylglutamate (NAG). The pH or protease-induced cleavable bonds are broken in the endo-lysosomes, thus activating the polymer's amine groups, leading to the efficient endosomal escape of the siRNAs [143, 144]. A phase 1 clinical study showed the tolerability and safety of ARC-520 administration in healthy individuals [145]. However, the phase 2 clinical study was terminated early due to the report of death in non-human primates (NHPs) in a nonclinical long-term safety study with the high dose of another RNAi therapeutics with the same excipient of ARC-EX1 [142]. The observed safety concerns attributed to the EX1 delivery agent, which made Arrowhead to stop all studies based on the DPC technology and to shift to the TRiM™ platform, a targeting conjugated siRNA technology [71]. This case is another example underscoring the safety concerns with cationic polymers, as fully discussed in section 3.1.

4.3. TKM-ApoB

TKM-ApoB or Pro-040201 is a liposomal siRNA targeting apolipoprotein B, designed to reduce the cholesterol uptake of hepatocytes in hypercholesterolemia patients. The TKM-ApoB is a stable nucleic acid lipid particle (SNALP) produced by self-assembly of ionizable cationic DLinDMA ( 1,2-dilinoleyloxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-aminopropane) and helper lipid molecules forming a lipid bilayer structure with surface PEG modification, a technology developed by Tekmira Pharmaceuticals [146]. It was the first effective RNAi therapeutic investigated in NHPs, with no observed immune reactions [147]. However, the phase 1 clinical study (NCT00927459) of IV administration of TKM–ApoB in a total of 17 patients was terminated due to the potential for immune stimulation with further dose escalation due to the occurrence of flu-like symptoms in one of the two patients who received the highest dose [148]. As the inclusion of 2'-OMe uridine or guanosine modifications completely abrogated the immunogenicity of the siRNA in preclinical studies, the role of the SNALP in causing the observed toxicities is more likely [36]. However, the possibility of siRNA's immunogenicity cannot be completely excluded.

4.4. TKM-080301

TKM-080301 is another LNP formulation containing anti-polo-like kinase 1 (PLK 1) siRNA for the treatment of solid cancers, developed by Tekmira Pharmaceuticals. TKM-080301 is also based on DLinDMA technology used in the TKM-ApoB, but with a replacement of C14 PEG-lipid with its C18 analog for enhanced blood circulation time [149, 150]. The preclinical studies showed no immunogenicity and only limited toxicity was observed in the liver and spleen [151]. In the phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT02191878), DLTs, specifically a grade 3 CRS, were observed with a dose of 0.9 mg/kg [152], and the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was determined to be 0.75 mg/kg. However, MTD was further reduced to 0.6 mg/ml after two patients developed grade 4 thrombocytopenia. The 0.6 mg/ml dose was generally well-tolerated but exhibited a limited antitumor effect.

It is unknown whether the siRNA, delivery vehicle, or the combinatory effect of the two was responsible for the observed DLTs in TKM-ApoB and TKM-080301. Nevertheless, the solution to evade the mentioned DLTs was met by developing two orders of magnitude more potent ionizable lipids like DLin-MC3-DMA ((6Z,9Z,28Z,31Z)-heptatriaconta-6,9,28,31-tetraen-19-yl-4-(dimethylamino) butanoate), produced by Alnylam and used in ONPATTRO®, which enabled reaching the therapeutic outcome at significantly lower doses [153]. Additionally, ONPATTRO® features shorter PEG-lipids with C14 acyl chains (versus TKM-080301's longer C18 PEG-lipids), which enable the detachment of these PEG-lipids in plasma's lipid sink, thereby enhancing targeting and intracellular delivery [153, 154].

4.5. Revusiran

Revusiran is a GalNAc conjugated siRNA developed by Alnylam, based on standard template chemistry (STC), directed against TTR and indicated for use in patients with TTR-mediated familial amyloidotic cardiomyopathy (FAC). The phase 1 (NCT01814839) study of revusiran was generally well-tolerated by healthy individuals, with no evidence of systemic immune activation or any other safety concerns [155]. The phase 3 ENDEAVOUR study (NCT02319005) was concurrently running with a phase 2 open-label extension (OLE) (NCT01981837) to assess the benefit/risk profile of revusiran based on the concerns related to causing or worsening peripheral neuropathy. This study was discontinued due to the unbalanced death between the treatment and placebo group [156]. It was observed that eighteen (12.9%) patients on revusiran and 2 (3.0%) on placebo died primarily due to heart failure during the treatment period. Revusiran was not the causative factor in the death of the drug treatment group upon further investigations. However, revusiran's potential role could not be completely ruled out.

Drug-induced demyelinating neuropathies are either immune mediated or caused by direct toxicity. In the case of revusiran, the possibility of immune mediated neuropathy was excluded since neither significant lymphocytic infiltration was identified nor an antigen response was observed. There are some possible mechanisms of direct toxicity of revusiran on Schwann cell such as lowering wild-type transthyretin which is also expressed in these cells, and possibility of off-target effects or saturation of RNAi machinery, or potential role of GalNAc moiety on neuronal demyelination [139].

4.6. Other RNA based therapies: MRX34, RG-101

Two other cases of failed clinical trials of a miRNA mimic and an anti-miR ASO due to toxicity issues are also interesting and relevant to what have been discussed so far.

MRX34 is a liposomal miR-34a mimic used to treat solid tumors developed by Mirna therapeutics. Despite no evidence of immunogenicity in preclinical studies in mice and NHPs, a phase 1 clinical trial of MRX34 (NCT01829971) was terminated due to serious adverse events (including one case of cytokine release syndrome (CRS)) in 5 patients, resulting in the death of 4 individuals [16]. The exact mechanism of toxicity remains unclear. However, because the liposomal carrier was also used in another investigational RNAi therapy, the role of the carrier in the observed toxicities is probably unlikely [157]. Due to the presence of GU-rich immunostimulatory motifs in miR34, the immunogenicity may be caused by miRNA TLR activation, possibly triggered by the combinatory effect of the carrier [14]. In addition, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), a known target of mir-34a, or on-target effects in immune cells might have also played a role in the observed immunotoxicity [16].

RG-101 is a GalNac-conjugated anti-miR-122 ASO used to treat patients with chronic HCV infection, developed by Regulus Therapeutics. In a phase 1a clinical study, the one-time subcutaneous (Sub-Q) injection of RG-101 with oral administration of viral protein inhibitor GSK2878175 was shown to be a curative regimen for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients [158]. However, an unexpected side effect was observed in phase 1b of the clinical study when two patients developed jaundice due to elevated bilirubin levels, leading to the study's termination [15].

RG-101 is believed to cause the observed toxicity in HCV patients by inhibiting conjugated bilirubin transport and exhibiting preferential uptake by hepatocytes [159]. Still, the exact mechanism of impaired bilirubin transport by RG-101 remains unknown, especially when compared with the safety profile of another anti-miR 122 therapeutic, miravirsen [160]. Nevertheless, since the hepatocyte-specific loss of miR-122 and liver-specific deletion of Dicer did not affect bilirubin metabolisms in previous studies [161, 162], the possibility of undesired on-target effects or global impact on miRNA processing was ruled out [14].

A summary of the RNA therapeutics that failed in clinical trials due to safety concerns can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Failed clinical trials of RNA therapies due to safety issues.

| Drug candidate |

Payload | Delivery platform |

Indication | Safety issue | Major events | Status | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CALAA-01 [141] |

Anti-R2 siRNA | Tumor-targeted nanocomplex | Solid tumors | Phase 1a: DLTs in 2 patients Phase 1b: DLTs in other patients |

Grade3,4: Lymphopenia, Hypersensitivity, ischemic colitis, hyponatremia | Phase 1 terminated (NCT00689065) |

Calando Pharmaceuticals |

| ARC-520 [142] |

Anti HBV cccDNA siRNA | Cholesterol-targeted siRNA conjugate+ARC-EX1 | HBV | Phase 2: Death of NHPs with high doses of another investigational RNAi therapeutic with ARC-EX1 excipient | Early termination of study | Phase 2 terminated | Arrowhead pharmaceuticals |

| TKM-ApoB [148] |

Anti APoB siRNA | SNALP | Hypercholesterolemia | Phase 1: potential of immune stimulation with dose escalation | Immune-mediated adverse events | Phase 1 terminated (NCT00927459) |

Tekmira Pharmaceuticals |

| TKM-080301 [152] |

anti-PLK1 siRNA | SNALP | Solid tumors | Phase 1/2: - Dose 0.9 mg/kg: DLTs including grade 3 CRS - Dose 0.75 mg/kg: 2 patients grade 4 thrombocytopenia - Dose 0.6 mg/kg: well-tolerated but limited efficacy |

Thrombocytopenia, peritoneal hemorrhage, sepsis, hepatic failure | Phase 1/2 completed (NCT02191878) |

Tekmira Pharmaceuticals |

| Revusiran [156] |

Anti-TTR siRNA | GalNac-conjugate | hATTR cardiomyopathy | Phase 3: unbalanced death between the treatment and placebo group | Cardiac failure, Hepatic and renal events, Peripheral neuropathy |

Phase 3 terminated (NCT02319005) |

Alnylam |

| MRX34 [16] |

Anti-miR-34 | Liposome | Solid tumors | Phase 1: SAEs in 5 patients, causing death of 4 | Immune-mediated adverse events in lung and colon, multi-organ failure, generalized seizure, CRS | Phase 1 terminated (NCT01829971) |

Mirna therapeutics |

| RG-101 [15] |

Anti – miR122 | GalNac-conjugate | HCV | Phase 1b: 2 patients developed jaundice | High levels of bilirubin in the blood | Phase 1 terminated | Regulus Therapeutics |

5. Addressing toxicity issues in siRNA therapeutics

5.1. Improving toxicity assessment of siRNA therapies

One of the challenges in assessing the toxicity of siRNA therapies is lack of specifically designed official safety and regulatory guidance for this class of therapies. Based on their chemical synthesis, siRNA therapies mainly follow the small molecule guidance ICH M3(R2), for nonclinical safety studies. However, there has been debate about the relevance of these regulations for this class of drugs due to their unique pharmacokinetic (PK) profile and mechanism of action. For instance, the role of in vitro assessments of siRNA plasma protein binding and drug-drug interactions in understanding the PK/pharmacodynamic (PD), safety and translation of siRNA therapies have been discussed and summarized into decision trees as a guidance for industry by siRNA working group [163] .

Another relevant document that has been released by FDA is a guidance for sponsor-investigators on nonclinical testing of individualized ASO drug products for severely debilitating or life-threatening diseases (FDA-2021-D-0320). In this document, the following assessments are warranted: in silico/and or in vitro assessments of possible hybridization dependent off-target effects, evaluating effects in the core safety pharmacology battery cardiovascular, central nervous, and respiratory systems for systemically administered investigational ASO, and a single 3-month good laboratory practice-compliant general toxicity study that can support FIH dosing which can be conducted in a justified rodent or non-rodent species. While in vitro human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) testing, safety pharmacology for non-significant systemic exposure, and genotoxicity are usually not warranted. While siRNA and ASO share some similarities, they have different physicochemical properties, mechanisms of action and ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion) profile, which underscore a need to specifically design regulatory and safety guidance for this class of therapies.

A survey was conducted in 2018 by the ONT working group of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) to outline the challenges in nonclinical safety assessment and regulatory expectations of ONT from industry [164]. The results of this questionnaire highlighted some important discrepancies in toxicity assessment strategies of ONT. For instance, number and choice of species was varied between different safety packages: Mostly companies used two species aligned with ICH M3(R2) requirements, a rodent and a non-rodent. However, some used only one species but have provided justification for that. The choice of species between rat and mouse was also different among investigators. The choice of species was mostly dependent on the type of ONTs with ss ONTs being evaluated in mouse while ds ONTs were tested in rats. The rationales of choosing the mouse over rat for ss ONT was not well elaborated but probably it was due to the oversensitivity of rats to ss PS-ONTs in developing age-related chronic progressive nephropathy.

Moreover, the choice of non-rodent species, between NHPs and other species such as swine, rabbit, dogs was varied among companies. The predictability of the non-rodent models should be well explored since even with NHPs being the most relevant species, translational gaps resulting from differences between NHPs and humans can cause non-predictive results. For instance, there are potential variations in PK profiles of therapeutics [165] and different degrees of susceptibility to NPs compared to humans [141]. Furthermore, NHPs have been shown to be more susceptible to complement activation and effects on platelets by PS ASOs [166], and there are reports of the non-predictive immunogenicity by NHPs in response to biopharmaceuticals [167]. These translational gaps are among the primary reasons for failed clinical trials, underscoring the importance of developing more predictive preclinical studies.

The other source of inconsistencies in designing safety packages between different companies was the high-dose selection approach, scaling dose to human, and the strategies related to dealing with hybridization dependent off target effects, and management of impurities [164]. The mentioned variations in designing safety packages for ONTs, calls for a need for harmonization efforts, which can be obtained by active collaborations between sponsors and regulatory agencies.

A document released by FDA in 2022 is the clinical pharmacology considerations for the development of ONT therapeutics (FDA-2022-D-0235) which is summarized in table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of FDA draft on clinical pharmacology considerations for the development of oligonucleotide therapeutics

| Safety assessment | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Characterizing QTc Interval Prolongation and Proarrhythmic Potential | -Applicable to all ONTs - The timing and extent of the clinical QT assessment depends on benefit/risk profile of the ONT |

| Performing Immunogenicity Risk Assessments | - Multi-tiered immunogenicity assay for ONT and delivery platform such as targeting ligand and/or the PEGylated carriers -Evaluation of effect of Anti-drug antibodies on PK/PD, and immunogenicity of the therapeutic - Assessment of potential interference of ONT with Anti-drug antibody testing - Preserving samples in early development (e.g., Phase 1/ First-in-human studies) for later testing - Assessing nucleotide sequence-specific antibodies and/or bioactivity in certain cases -Evaluation of the effect of disease state and concomitant medications on the immune response |

| Characterizing the Impact of Organ Impairment on Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Safety | -Identify the role of the liver and kidney in the disposition and elimination of the ONT therapeutic - Enrollment of subjects with a full range of hepatic and/or renal function in the late-phase trials -Effect of organ impairment on liver/kidney targeting and disposition of drug |

| Assessing Drug Interactions | -ONTs are usually not substrate of cytochrome P450 enzymes and transporters - Evaluate the direct modulation of CYP enzymes or transporters via off-target hybridization with CYP enzyme or transporter mRNA transcripts -Evaluate the indirect modulation of CYP enzymes or transporters by interfering with the synthesis or degradation of heme or by modulating cytokines |

This document refers to a major consideration in assessing the safety profile of siRNA therapies which is the effect of disease state on the toxicity and immunogenicity of this class of therapies. These considerations are particularly important for preventing failure in clinical trials beyond phase one with diseased patients as the study population. For instance, in assessing the immunogenicity of investigational siRNA, the status of immune system of patients such as autoimmune or inflammatory conditions and the effect of concomitant medications such as immunosuppressants should not be neglected. Another consideration is the impact of organ impairment on the targeting ability of the siRNA therapies. For instance, in case of liver or kidney damage, when these organs are the target of the investigational siRNA, there is a possibility of changes in expression and turnover of receptors of the targeting moieties in these organs, which might affect the disposition of the drug. Furthermore, in case of targeting hepatocytes by siRNA-LNPs, the effect of pathological state of liver on the intrahepatic biodistribution of LNPs and liver susceptibility to toxicity of investigational siRNA should not be neglected.

5.2. High throughput toxicity screening of NPs

To improve the safety profile of nanoparticulate siRNA delivery vehicles, high throughput screening (HTS) of toxicological properties of these systems is highly warranted. HTS provides efficient toxicity screening of large numbers of NPs, thus enabling the identification of potentially hazardous NPs timely and preventing the failure of siRNA therapies due to safety concerns at later stages. Due to the laborious, expensive, and low throughput nature of in vivo studies, in vitro assessments are mostly used for HTS. Use of robotics have also proven beneficial in enhancing the volume and speed of in vitro assessments. Despite the benefits of in vitro HTS, the major downside to these studies is often poor correlation of in vitro and in vivo results [116], thus causing the faulty prediction of in vivo performance and toxicity by in vitro assessments. In this sense, the key to developing more accurate HTS is either improving the predictability of in vitro evaluations or enabling the in vivo assessments of large numbers of particles.

Organ on chip technology enables more comprehensive in vitro simulation of the complex in vivo microenvironments by providing the 3D cell culture and fluid flow thus mimicking the continuous nutrition exchange, gas perfusion and physiological shear stress [168]. In this sense, organ on chip technology can be used as a robust and high throughput platform for evaluating the toxicity of drugs including NPs. As liver and kidney are major organs of toxicity, liver on chip and kidney on chip can be useful to investigate the hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity of drugs. For instance, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of different hepatotoxic drugs obtained from a 3D microfluidic primary hepatocyte model showed great correlation with the reported in vivo median lethal dose (LD 50) values [169]. In another investigation, the combination of liver chip and intestine chip was implemented to investigate the NP toxicity in digestive system by detecting aspartate aminotransferase (AST), an indicator of sublethal cellular injury to the liver [170]. Some companies have also started to use liver on chip platforms for assessing the hepatotoxicity of investigational drugs. Assessment of nephrotoxicity induced by drugs has also been done by measuring γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) on the outflow of kidney on chip [171]. All these endeavors highlight the promise of using organ on chips for high throughput toxicity assessment of siRNA therapies and their delivery systems.

Besides, some efforts have been made in enhancing the testability of large number of particles in vivo. One of the toxicity mechanisms of siRNA-NPs is the unwanted accumulation in off-target organs. In a novel approach many different types of LNPs have been made by simple microfluidic mixing with each LNP carrying a specific nucleic acid barcode [172]. This pool of barcoded LNPs then will be injected to animal and the biodistribution of these LNPs can be tracked by deep sequencing of the barcodes. The results of this study showed that the LNPs, which were screened for liver targeting, later showed gene silencing when encapsulated with siRNA. This novel approach shows great potential in HTS of RNA delivery platforms.

In the mentioned HTS approaches the common factor is application of artificial intelligence (AI) in handling the massive data generated. For instance, deep learning has been used to contribute to the organ on chip technology at different stages of image processing such as image synthesis, segmentation, reconstruction, classification, and detection [173]. Furthermore, incorporation of deep sequencing significantly increases the number of barcoded particles that can be investigated simultaneously and improves the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the measurements. In addition to the handling of the massive data generated by HTS, AI comes into picture as a platform to build in silico models to predict toxicity of NPs, which can serve as in silico toxicity screening tools. Recent endeavors in machine learning and in silico toxicity assessment models such as Tox21 project, have aimed for predicting the toxicity of multiple drugs based on their structure. Different models of quantitative structure-activity/toxicity relationships (QSAR/ QSTR) of NPs have also been used for rationalizing the design of safer NPs which showed an accuracy of higher than 97% in both training and validation sets [174]. To build more predicative toxicity databases of siRNA therapies and their delivery systems, it is mandatory that industry-driven collaborative efforts been made to enable availability of confident data.

5.3. Design strategies to overcome toxicities: Lessons learned from the successful siRNA therapies

Despite the outstanding achievements in developing effective siRNA therapies, toxicity is still a significant obstacle to the successful clinical translation of siRNAs. Analyzing failed clinical trials and successful therapies that reached the clinic can indicate approaches to safer siRNA design. Safety concerns related to siRNA therapies and possible approaches to address them are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Safety concerns with RNA therapies and possible approaches to address them

| Safety concern category |

Safety concern | Possible approaches to address the concern |

|---|---|---|

| Challenges in toxicological assessments | Lack of consensus in design of toxicity study packages |

|

| Lack of correlation between pre-clinical and clinical toxicological studies |

|

|

| Toxicity observed in diseased people |

|

|

| Failure of siRNA therapies due to safety concerns at late stages | Implementing HTS of siRNA therapies using:

|

|

| siRNA intrinsic toxicity | Immunogenicity of siRNA |

|

| Hybridization-dependent off-target toxicities |

|

|

| Hybridization-dependent on-target toxicities |

|

|

| Saturation of RNAi machinery |

|

|

| Delivery-mediated toxicity | Immunogenicity of the carrier |

|

| Chemistry-related toxicities of carrier |

|

In light of the safety concerns with the administration of positively charged polymers and lipids, as fully discussed in this review, and the clinical trials failure of CALAA-01 and ARC-520 due to vehicle-induced toxicity issues, research has focused on developing non-permanently cationic platforms such as ionizable lipid-based NPs, biodegradable polymers (LODER™), exosomes, or ligand-conjugated siRNAs [131, 175-178].

iLNPs are one of the most successful platforms for hepatic delivery of siRNA. Superiority of iLNPs over cationic LNPs is attributed to their improved safety profile owing to the lack of a positive surface charge in the blood and their ability to target hepatocytes through Apolipoprotein E (APOE)-mediated receptors, which is absent in cationic lipids [179]. Although not as effective as exogenous targeting, this ability increases iLNPs efficacy and safety through reduction of hepatotoxicity caused by undesired accumulation in other liver cells. As part of the ONPATTRO® design, detachable shorter chain PEG-lipids were used, further enhancing the endogenous targeting of the system [153]. Dissociable PEGs can also improve the overall safety profile of LNPs by diminishing the immunotoxicity associated with PEG molecules. Furthermore, ionizable lipids such as DLinDMA (used in TKM-ApoB and TKM-080301) with significant DLTs have evolved to more potent lipids such as DLin-MC3-DMA (used in ONPATTRO®), which have dramatically improved their safety profiles by reducing the dosing [153]. The dynamic research area in iLNPs is still moving toward more tolerable formulations such as biodegradable L319 (di((Z)-non-2-en-1-yl) 9-((4-(dimethylamino) butanoyl) oxy) heptadecanedioate), derived from DLin-MC3-DMA by adding a biocleavable ester linkage within hydrophobic alkyl chains [180]. Furthermore, ester-independent strategies such as replacing racemic ionizable lipids with steropure ionizable lipids can hold promise in designing safer LNPs [129].

Significant advances in chemical modification of siRNA structure also played a significant role in paving the way for successful clinical translation of siRNA therapies. The structure of the siRNA molecule has changed significantly from the unmodified immunostimulatory siRNA that was used in bevasiranib to the FDA-approved partially modified ONPATTRO® to even more heavily modified structures with enhanced safety and efficacy. Alnylam introduced the STC design (used in Revusiran) with PS, 2'-F, and 2'-OMe modifications, but due to safety concerns with heavy 2'-F substitutions, shifted to the next-generation siRNA designs such as enhanced stabilization chemistry (ESC) and advanced ESC, each time increasing PS content to improve stability and potency, while decreasing 2'-F modifications to avoid toxicities [71, 181]. Moreover, the significant increase in siRNA potency and durability resulted in a dominant decrease in dosing and dosing frequency, thereby evading the DLTs associated with siRNA molecules [181]. Furthermore, ESC+ design, compared to advanced ESC, takes advantage of seed modifications to reduce siRNA-induced off-target effects [182].

Remarkable improvements in stability, potency, and safety due to siRNA’s chemical modifications, along with the efficient targeting of siRNA using conjugation technologies such as GalNAc, suggest that the need for nanoparticulate siRNA vehicles, especially for hepatic delivery, is declining. According to the commercial trend transitioning from NPs to siRNA conjugates, Arbutus has switched from liposomes to GalNAc conjugates and Arrowhead has moved from DPC delivery vehicles to TRiM™ platforms [71].

Even though iLNPs and GalNAc conjugates are both promising platforms, GalNAc has several advantages over iLNPs other than easier sub-Q administration. The GalNAc conjugates have minimal side effects due to their more efficient and safer targeting of hepatocytes as well as their remarkable potency and durability [130, 183]. Furthermore, the hurdle of conjugated siRNA’s immunogenicity was minimized with precise modifications, with no failed clinical trial due to immunotoxicity. Moreover, adding another component to siRNA, such as NPs with their cytotoxic and immunogenic properties, the potential for synergistic immunostimulatory effects, or even independent gene expression signatures, significantly raises safety concerns in NP-based siRNA therapies.

6. Future perspectives

The field of siRNA therapeutics is rapidly growing with five FDA approved products and many other siRNA candidates under investigation. In this climate, it is paramount to gain a deeper understanding of the intrinsic and delivery related toxicities of siRNA as the underlying cause of toxicity remains still unresolved in many of the previously failed clinical trials. Developing more predictive preclinical toxicity assessments and harmonizing the design of toxicity study packages by regulatory guidelines specifically designed for siRNA are among the key steps to address toxicity issues with this class of therapies. Implementing HTS for faster toxicity assessment such as in silico prediction tools, barcoding of NPs, and using organ on chip models can be beneficial in enabling more efficient and comprehensive toxicity assessments to enable designing safer siRNA therapies.

Acknowledgement

This study was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R35GM140862 to X.B.Z.].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Fire A, et al. , Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature, 1998. 391(6669): p. 806–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Setten RL, Rossi JJ, and Han SP, The current state and future directions of RNAi-based therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2019. 18(6): p. 421–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang F, Zuroske T, and Watts JK, RNA therapeutics on the rise. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2020. 19(7): p. 441–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caplen NJ, RNAi as a gene therapy approach. Expert Opin Biol Ther, 2003. 3(4): p. 575–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YK, RNA Therapy: Current Status and Future Potential. Chonnam Med J, 2020. 56(2): p. 87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian Z, et al. , Insight Into the Prospects for RNAi Therapy of Cancer. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2021. 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang MM, et al. , The growth of siRNA-based therapeutics: Updated clinical studies. Biochem Pharmacol, 2021. 189: p. 114432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoy SM, Patisiran: First Global Approval. Drugs, 2018. 78(15): p. 1625–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams D, et al. , Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med, 2018. 379(1): p. 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott LJ, Givosiran: First Approval. Drugs, 2020. 80(3): p. 335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balwani M, et al. , Phase 3 Trial of RNAi Therapeutic Givosiran for Acute Intermittent Porphyria. N Engl J Med, 2020. 382(24): p. 2289–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott LJ and Keam SJ, Lumasiran: First Approval. Drugs, 2021. 81(2): p. 277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamb YN, Inclisiran: First Approval. Drugs, 2021. 81(3): p. 389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winkle M, et al. , Noncoding RNA therapeutics — challenges and potential solutions. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2021. 20(8): p. 629–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Ree MH, et al. , Safety, tolerability, and antiviral effect of RG-101 in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a phase 1B, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2017. 389(10070): p. 709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong DS, et al. , Phase 1 study of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, in patients with advanced solid tumours. British journal of cancer, 2020. 122(11): p. 1630–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Fougerolles A, et al. , Interfering with disease: a progress report on siRNA-based therapeutics. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2007. 6(6): p. 443–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramaswamy G and Slack FJ, siRNA: A Guide for RNA Silencing. Chemistry & Biology, 2002. 9(10): p. 1053–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen S and Thomsen AR, Sensing of RNA viruses: a review of innate immune receptors involved in recognizing RNA virus invasion. Journal of virology, 2012. 86(6): p. 2900–2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng Z and Lu M, RNA Interference-Induced Innate Immunity, Off-Target Effect, or Immune Adjuvant? Frontiers in immunology, 2017. 8: p. 331–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DW, et al. , Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood, 2014. 124(2): p. 188–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar H, Kawai T, and Akira S, Pathogen recognition by the innate immune system. Int Rev Immunol, 2011. 30(1): p. 16–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munir M and Berg M, The multiple faces of proteinkinase R in antiviral defense. Virulence, 2013. 4(1): p. 85–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexopoulou L, et al. , Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature, 2001. 413(6857): p. 732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sioud M, Induction of inflammatory cytokines and interferon responses by double-stranded and single-stranded siRNAs is sequence-dependent and requires endosomal localization. J Mol Biol, 2005. 348(5): p. 1079–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sioud M, Single-stranded small interfering RNA are more immunostimulatory than their double-stranded counterparts: a central role for 2'-hydroxyl uridines in immune responses. Eur J Immunol, 2006. 36(5): p. 1222–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodchild A, et al. , Sequence determinants of innate immune activation by short interfering RNAs. BMC Immunol, 2009. 10: p. 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heil F, et al. , Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science, 2004. 303(5663): p. 1526–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hornung V, et al. , Sequence-specific potent induction of IFN-alpha by short interfering RNA in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Nat Med, 2005. 11(3): p. 263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Judge AD, et al. , Sequence-dependent stimulation of the mammalian innate immune response by synthetic siRNA. Nat Biotechnol, 2005. 23(4): p. 457–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reynolds A, et al. , Induction of the interferon response by siRNA is cell type- and duplex length-dependent. Rna, 2006. 12(6): p. 988–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robbins M, Judge A, and MacLachlan I, siRNA and innate immunity. Oligonucleotides, 2009. 19(2): p. 89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin AA, A review of the issues in the pharmacokinetics and toxicology of phosphorothioate antisense oligonucleotides. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1999. 1489(1): p. 69–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henry SP, et al. , Considerations for the Characterization and Interpretation of Results Related to Alternative Complement Activation in Monkeys Associated with Oligonucleotide-Based Therapeutics. Nucleic Acid Ther, 2016. 26(4): p. 210–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valenzuela RAP, et al. , Base modification strategies to modulate immune stimulation by an siRNA. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology, 2015. 16(2): p. 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Judge AD, et al. , Design of noninflammatory synthetic siRNA mediating potent gene silencing in vivo. Mol Ther, 2006. 13(3): p. 494–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Meer L, et al. , Injection site reactions after subcutaneous oligonucleotide therapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2016. 82(2): p. 340–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]