Abstract

Objectives

Pre-existing rilpivirine resistance-associated mutations (RVP-RAMs) have been found to predict HIV-1 virological failure in those switching to long-acting injectable cabotegravir/rilpivirine. We here evaluated the prevalence of archived RPV-RAMs in a cohort of people living with HIV (PWH).

Methods

We analysed near full-length HIV-1 pol sequences from proviral DNA for the presence of RPV-RAMs, which were defined according to the 2022 IAS–USA drug resistance mutation list and Stanford HIV drug resistance database.

Results

RPV-RAMs were identified in 757/5805 sequences, giving a prevalence of 13.0% (95% CI 12%–13.9%). Amongst the ART-naive group, 137/1281 (10.7%, 95% CI 9.1%–12.5%) had at least one RPV-RAM. Of the 4524 PWH with viral suppression on ART (VL <400 copies/mL), 620 (13.7%, 95% CI 12.7%–14.7%) had at least one RPV-RAM. E138A was the most prevalent RPV-RAM in the ART-naive group (7.9%) and the ART-suppressed group (9.3%). The rest of the mutations observed (L100I, K101E, E138G, E138K, E138Q, Y181C, H221Y, M230L, A98G, V179D, G190A, G190E and M230I) were below a prevalence of 1%.

Conclusions

RPV-RAMs were present in 10.7% of ART-naive and 13.7% of ART-suppressed PWH in Botswana. The most common RPV-RAM in both groups was E138A. Since individuals with the E138A mutation may be more likely to fail cabotegravir/rilpivirine, monitoring RPV-RAMs will be crucial for effective cabotegravir/rilpivirine implementation in this setting.

Introduction

By the end of 2021, 38.4 million people globally were estimated to be living with HIV (PWH) and 650 000 people had died from HIV-related illnesses.1 In 2021, Botswana was amongst the first countries globally to surpass the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets; 95% of PWH were aware of their HIV status, 98% of PWH were on ART, and 98% of PWH on ART were virologically suppressed.1,2 Newer long-acting (LA) ART regimens are expected to contribute to the eradication of HIV as a public health threat, especially for low and middle-income countries (LMICs).

LA injectable antiretrovirals are currently considered a good choice for persons with adherence issues and for maintaining viral suppression,3 and for individuals who would prefer an alternative to daily oral therapy.4,5 LA cabotegravir, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI), and rilpivirine, an NNRTI, have been approved by the US FDA for use by PWH ≥18 years old who are virally suppressed (HIV RNA level <50 copies/mL).4–7 The LA cabotegravir plus rilpivirine is more effective and less expensive than oral ART when considering the impact of treatment adherence on subsequent viral transmission.8

Virological failure in cabotegravir/rilpivirine-treated individuals is predicted by the presence of baseline archived rilpivirine resistance-associated mutations (RPV-RAMs) in individuals with viral suppression.9,10 The presence of RPV-RAMs can cause rilpivirine to fail, which would subject participants to cabotegravir monotherapy.11,12 At the time of virological failure, three participants in the ATLAS Study who received LA cabotegravir/rilpivirine to maintain viral suppression had RPV-RAMs detected in their RNA samples, which largely matched the RPV-RAMs present in HIV-1 DNA at baseline.5

Most countries, including Botswana, are planning to adopt LA cabotegravir/rilpivirine injectable in their HIV treatment programmes for virologically suppressed PWH to maintain viral suppression and for use as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), therefore there is a need to examine baseline rilpivirine mutations prior to the introduction of LA cabotegravir/rilpivirine. Even though HIV drug resistance genotyping using plasma HIV RNA is still the gold standard, HIV proviral drug resistance genotyping provides valuable information in treatment-experienced individuals with suppressed plasma HIV RNA.13 Some studies have shown that plasma HIV RNA and proviral DNA exhibit a high-level genotype concordance.13,14 In this study, we investigated RPV-RAMs in ART-naive and ART-experienced PWH with suppressed HIV-1 viral load (VL). The results from this study will guide the use of cabotegravir/rilpivirine in countries with predominant HIV-1C epidemics, including Botswana.

Materials and methods

Selection of study participants

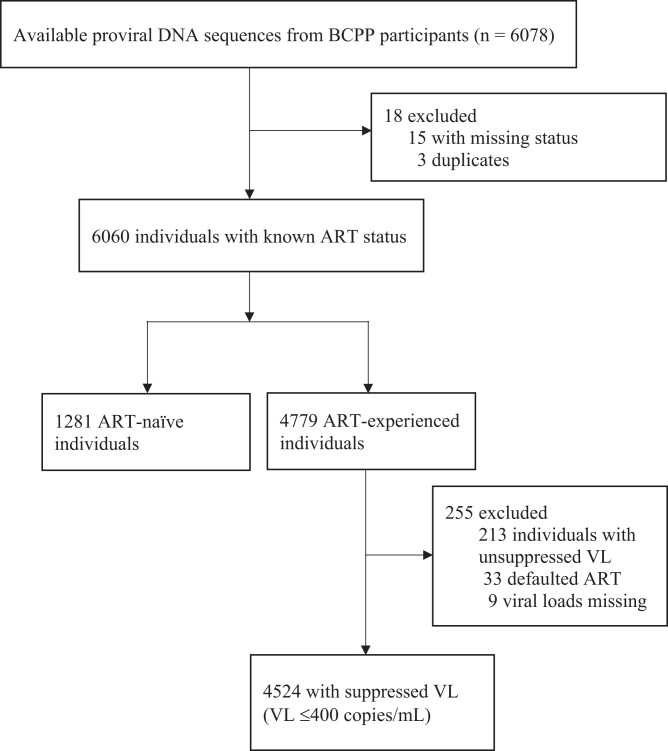

Study participants were recruited from a large community HIV incidence trial described elsewhere that enrolled participants aged 16 to 64 years, followed for 30 months from 2013 to 2018.15 In this analysis, we included a total of 5805 (95.5%) proviral sequences from Botswana Combination Prevention Project (BCPP) participants, of which 1281 proviral DNA sequences were obtained from the treatment-naive individuals, and 4524 were from ART-experienced participants with HIV-1 VL ≤400 copies/mL (Figure 1). We did not include sequences for individuals experiencing virological failure since LA cabotegravir/rilpivirine is currently recommended only for virologically suppressed adults (HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL), and is not currently recommended for people with virological failure.16 To control for the impact of archived HIV proviral DNA mutations, an ART-naive group was used. Hence the main objective of this study was to identify HIV drug resistance mutations using proviral DNA sequences from HIV-infected ART-naive and ART-suppressed individuals in Botswana.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participants used to determine the prevalence of RPV-RAMs.

Near full-length HIV genotyping

HIV-1 proviral DNA sequences were generated using next-generation sequencing (NGS) as previously described elsewhere.15 Briefly, a long-range HIV genotyping protocol was used to generate viral sequences and the first-round amplicon was subjected to the Illumina sequencing system. The NGS was performed at the Biopolymers Facility at Harvard Medical School (https://genome.med.harvard.edu/) or by the PANGEA HIV consortium at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/) utilizing Illumina MiSeq and HiSeq platforms. A single consensus sequence represented the population of viral quasispecies per each participant.17 Minor viral variants were not analysed.

HIV-1 subtyping

The HIV-1 genotypic subtypes were determined using REGA version 318 and COMET19 online subtyping tools.17 More than 99.9% of the screened samples had HIV-1C sequences,17 and only HIV-1C sequences were used in this analysis.

Drug resistance mutations and interpretation

RPV-RAMs were described according to the 2022 updated IAS-USA drug-resistance mutation list20 and the Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database (http://hivdb.stanford.edu). The level of rilpivirine resistance was predicted according to the Stanford HIV DRM penalty scores and resistance interpretation.21 All sequences with low-level, intermediate- level and high-level resistance according to Stanford and IAS algorithms were considered to have RPV-RAMs. The prevalence of RPV-RAMs was estimated in ART-naive individuals and in virally suppressed (HIV-1 RNA ≤400 copies/mL) individuals on ART. RPV-RAMs and their modes of action are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

RPV-RAMs and their MOAs

| MOA of rilpivirine | Drug resistance mutations | Mutation location | Associated-drug resistance mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binds to a hydrophobic pocket close to the active site of RT, causing conformational changes that inhibit the transcription of viral RNA to DNA.22 | E138A, G, K, Q | P51 subunit | Alters the rilpivirine dissociation and association equilibrium. | 23 |

| G190A, E | P66 subunit | Introduces a bulky side chain, which sterically interferes with binding. | 24 | |

| L100I | P66 subunit | Changes the shape of the pocket (the amino acid is β- branched instead of γ-branched). | 25 | |

| K101E, P | P66 subunit | Alters the chemical environment around the NNBP and its entryway. | 26 | |

| Y181C, I, L | P66 subunit | Causes loss of the aromatic ring interactions with NNRTIs. | 25 | |

| V179D | P66 subunit | Alters the chemical environment around the NNBP and its entryway. | 27 | |

| F227C/L | P66 subunit | Causes loss of the aromatic ring interactions with NNRTIs. | 25 | |

| Y188L | P66 subunit | Causes loss of the aromatic ring stacking interactions. | 27 | |

| M230IL | P66 subunit | Affects the mobility of the primer grip important for binding of NNRTIs. | 28 |

NNBP, non-nucleoside binding pocket.

Identification of hypermutated sequences

The Los Alamos Hypermut 2.0 program for hypermutations (https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HYPERMUT/hypermut.html) was used to assess for hypermutations, and identified mutations that could be a result of hypermutations were excluded.29

Statistical analyses

Characteristics of the participants were described using proportions with 95% CI and medians with IQR or percentages. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables among ART status groups. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA software version 15.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical considerations

The BCPP study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at the US CDC and the Botswana Health Research and Development Committee IRB and is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01965470). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s guiding principles. All BCPP participants provided written informed consent for the use of their samples in future studies.

Results

Study participants

This analysis included a dataset of 5805 sequences, of which 1281 (22%) were obtained from treatment-naive PWH, and the other 4524 (78%) were from ART-suppressed PWH (Figure 1). Among the ART-naive PWH, 856 (66.8%) were female, with a median age of 33 years (IQR: 27–42). Among the ART-suppressed PWH, 3267 (72.2%) were female, with a median age of 40 years (IQR 34–48) and 1257 (27.8%) were male, with the median age of 44 years (IQR 38–52) (Table 2). The most common ART regimens used were efavirenz + emtricitabine + tenofovir (EFV/FTC/TDF) (n = 1792; 39.6%), lamivudine + nevirapine + zidovudine (3TC/NVP/ZDV) (n = 719; 15.9%) and lamivudine + efavirenz + zidovudine (3TC/EFV/ZDV) (n = 621; 13.7%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants included (n = 5805)

| Characteristics | All participants (N = 5805) |

ART suppressed (N = 4524) |

ART naive (N = 1281) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 4123 (71) | 3267 (72) | 856 (67) |

| Male | 1682 (29) | 1257 (28) | 425 (33) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 40 (33–48) | 41 (35–49) | 34 (27–42) |

| Year of sampling, n (%) | |||

| 2013–15 | 3291 (57) | 2472 (55) | 819 (64) |

| 2016–18 | 2514 (43) | 2052 (45) | 462 (36) |

| Known ART regimens (n = 4090) | |||

| Non-NNRTI | 541 (13) | 541 (13) | NA |

| EFV | 2435 (60) | 2435 (60) | |

| NVP | 1114 (27) | 1114 (27) |

EFV, efavirenz-based therapy; NVP, nevirapine-containing regimen; non-NNRTI, other ART except NNRTIs.

Overall prevalence of RPV-RAMs

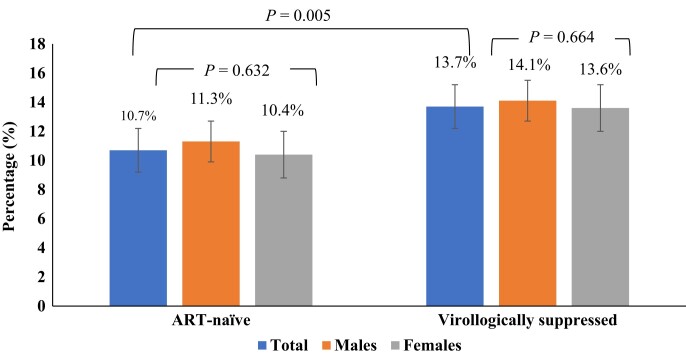

Before the exclusion of hypermutants, the total prevalence of RPV-RAMs was 21.0% (1218/5805). Prior to the exclusion of hypermutants, 21.3% (962/4524) of ART-suppressed individuals had RPV-RAMs, while 20.0% (256/1281) of ART-naive individuals had RPV-RAMs. After exclusion of hypermutants, RPV-RAMs were identified in 757/5805 sequences, giving a prevalence of 13.0% (95% CI 12%–13.9%). The overall prevalence of RPV-RAMs after exclusion of hypermutants (13%; 757/5805) was statistically different from before hypermutants were excluded (21%; 1218/5805) (P = <0.01). From now on we refer to RPV-RAMs after exclusion of hypermutants. There were no statistically significant differences in the overall frequency of RPV-RAMs in females [532/4123; 12.9% (95% CI: 11.9–13.9)] and males [225/1682; 13.4% (95% CI: 11.7–15.0)] PWH (P = 0.637). There was a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of RPV-RAMs in ART-naive individuals [137/1281; 10.7% (95% CI: 9.1–12.5)] compared with ART-suppressed individuals [620/4524; 13.7% (95% CI: 12.7–14.7)] (P = 0.005) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentages of individuals with RPV-RAMs by treatment category. Bars represent the 95% CI. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

RPV-RAMs in ART-naive participants

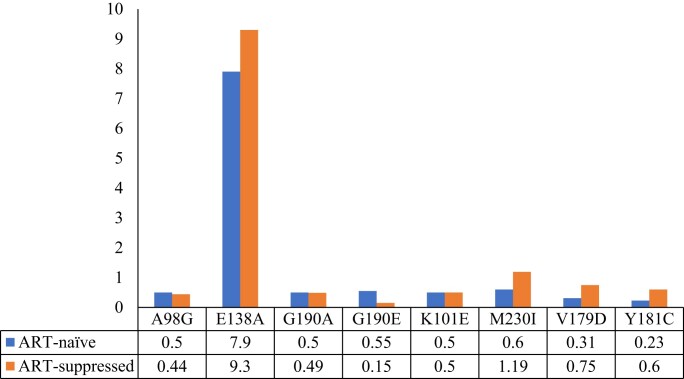

The prevalence of RPV-RAMs among ART-naive males and females was 11.3% (48/425) and 10.4% (89/856), respectively; P < 0.632. The most prevalent RPV-RAMs among the ART-naive individuals were E138A (n = 101; 7.9%) followed by M230I and G190E (n = 7; 0.55%) and lastly K101E, A98G and G190A, occurring at equal prevalence (n = 6; 0.5%) (Figure 3). Mutations E138G, E138K, V179D, Y181C, L100I, E138Q and H221Y were detected in fewer than 0.5% of the sequences (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). The most frequent rilpivirine combinations in ART-naive individuals were E138A + V179E and E138K + K101E, both at 0.31% (n = 4), and E138A + V179D (n = 3; 0.23%).

Figure 3.

Distribution of mutations associated with RPV-RAMs among ART-naive and ART-suppressed individuals. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

One hundred and six (8.3%) ART-naive participants demonstrated low-level resistance to rilpivirine, 1.2% (n = 15) of participants demonstrated intermediate resistance and 1.2% (n = 16) of participants demonstrated high-level resistance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of the rilpivirine drug resistance profiles

| Resistance levels | Total (N = 5805) |

ART-naive (N = 1281) |

Virologically suppressed (N = 4524) | P values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Overall resistance | 757 | 13.0 | 137 | 10.7 | 620 | 13.7 | 0.05 |

| High-level resistance | 61 | 1.1 | 16 | 1.2 | 45 | 1.0 | 0.42 |

| Intermediate resistance | 140 | 2.4 | 15 | 1.2 | 125 | 2.8 | <0.01 |

| Low-level resistance | 530 | 9.1 | 106 | 8.3 | 424 | 9.4 | 0.23 |

| Potential low-level resistance | 26 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0.57 | N/A |

P values obtained by comparing the proportions of mutations among ART-naive and virologically suppressed individuals.

NA, not applicable.

RPV-RAMs in ART-suppressed participants

Of the 620 ART-suppressed individuals with RPV-RAMs, 14.1% (177/1257) were male and 13.6% (443/3267) were female; P = 0.664. Among ART-suppressed individuals, the most prevalent RPV-RAMs were E138A (n = 419; 9.3%), K101E (n = 23; 0.51%), Y181C (n = 27; 0.60%), M230I (n = 54; 1.19%), V179D (n = 34; 0.75%) and G190A (n = 22; 0.49%) (Figure 3). The rest of the mutations detected had a prevalence of less than 0.5% (L100I, K101P, E138G, E138K, E138Q, Y181I, Y188L, H221Y, M230L, A98G, V106A, G190E and G190S (Table S1). The most frequent rilpivirine combinations among ART-suppressed individuals were E138A + M230I (n = 9; 0.20%), E138A + V179D (n = 17; 0.38%), E138A + K101E (n = 7; 0.15%), E138A + V179E (n = 2; 0.04%), E138K + K101E (n = 3; 0.07%) and K103N + L100I (n = 2; 0.04%).

Among ART-suppressed individuals, 0.57% (n = 26) of sequences with resistance to rilpivirine were classified as being potential low-level resistance; 9.4% (n = 424) were classified as having low-level resistance; 2.8% (n = 125) were classified as having intermediate resistance and 1.0% (n = 45) as with high resistance (Table 3).

Discussion

This study presents the first data on the prevalence of RPV-RAMs among ART-naive and virologically suppressed PWH on ART in Botswana. RPV-RAMs were present in proviral samples from 10.7% ART-naive and 13.7% ART-suppressed PWH in Botswana, with E138A being the most common RPV-RAM in both groups. Archived E138A and other RPV-RAMs may contribute to virological failure in ART-suppressed individuals switching to LA cabotegravir/rilpivirine injectables, which is a priority for the Botswana ART Programme in the near future.

Overall, the 13.0% of sequences with RPV-RAMs in our study was similar to the 12.5% of RPV-RAMs reported by Theys et al.30 among 4631 HIV-1 ART-naive individuals in Belgium, the 14.5% reported by Cecchini et al.31 among 112 HIV-infected pregnant women, and the 12.3% reported in South Africa among treatment-naive and experienced individuals.32 This prevalence is lower than other studies that reported a prevalence of 32% RAMs detected in 41 individuals who previously had virological failure and were later suppressed,33 and 46% in 140 individuals with confirmed virological failure.34 The observed differences between our study and studies by Gallien et al. and Kingoo et al. could be explained by the fact that, in contrast to them, we used ART-suppressed and ART-naive individuals whereas they used ART-experienced individuals with confirmed virological failure. Our findings are also comparable to those of a study from Argentina that showed a 14.3% overall prevalence of rilpivirine resistance (18.3% for ART-experienced individuals and 9.6% for ART-naive individuals.31

Drug resistance mutations have been found to be common in individuals experiencing virological failure in other settings, and their accumulation threatens the effectiveness of future treatment.35,36 The RPV-RAMs in our cohort can be explained by the previous use of efavirenz and nevirapine in this population, as these first-generation NNRTIs have cross-resistance with rilpivirine.37–41 In ART-naive individuals, RPV-RAMs might have been selected by NNRTI use and then transmitted to these individuals. NNRTI drug resistance levels need to be monitored as they may jeopardize the efficacy of future injectable agents due to the possibility of continued transmission of HIV-1 variants with NNRTI resistance.

E138A was the most common rilpivirine mutation both in ART-naive (7.9%) and ART-suppressed (9.3%) individuals, and typically decreases rilpivirine susceptibility by approximately 2-fold.42 E138A is a documented cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) escape mutation associated with human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-B*18 and was found to significantly increase rilpivirine resistance.43,44 The escape from CTL immune responses could be part of the reason for the increase in the prevalence of E138A in some populations. In our study, the prevalence of E138A in ART-naive individuals is close to the mutation’s global prevalence of HIV-1C (6.1%).45 This study demonstrates that E138A was responsible for more than half of the prevalence of RPV-RAMs. A high prevalence of E138A was also previously noted in PWH failing ART earlier on in Botswana,46 which is consistent with our current findings. Published literature also indicates that the E138A mutation contributes to the high prevalence of RAMs in other settings.47 In a study by Swindells et al.,5 in 2020, E138A was detected in three participants at the time of virological failure. Archived E138A was also present in five of the eight participants with confirmed virological failure in every 8 weeks dosing group.48 These findings show that the presence of archived E138A at baseline is one of the predictors of cabotegravir/rilpivirine failure. The prevalence of the E138A mutation should be interpreted with caution as more data on the effect of the E138A mutation alone on rilpivirine susceptibility are still being investigated and more cabotegravir/rilpivirine clinical trials need to be conducted in settings with high E138A mutation prevalence to determine the impact of the mutation on clinical outcomes.

We observed a low prevalence of other RPV-RAMs detected in our cohort in ART-naive and ART-suppressed individuals, ranging from 0.02% to 1.19% (L100I, K101E, K101P, E138G, E138K, E138Q, Y181C, Y181I, Y188L, H221Y, M230I, M230L, A98G, V106A, V179D, G190A, G190E and G190S). In our cohort, the RPV-RAMs K101P, Y181I, Y188L, M230L, V106A and G190S were absent in ART-naive groups. The prevalence of K101E, E138K and A98G was similar in the ART-naive and ART-suppressed individuals at 0.5%, 0.4% and 0.5%, respectively. Even though having rilpivirine proviral genotypic RAMs was one of the factors associated with virological failure in the ATLAS, FLAIR and ATLAS-2M studies,9 a very small population of ART-suppressed individuals with these mutations would likely experience virological failure if they were switched to LA cabotegravir/rilpivirine.

High-level resistance (Stanford penalty score of 60) was reported in 0.8% of ART-naive individuals compared with 0.6% of ART-suppressed participants. Four ART-naive individuals showed a combination of mutations scored as high-level resistance, E138K + K101E (n = 4; 0.31%, 95% CI 0.09–0.80). Available evidence suggests that E138K in combination with K101E may reduce rilpivirine susceptibility about 3-fold.49 In the ART-suppressed group, 10 participants showed a combination of mutations scored as high-level resistance: E138A + K101E (n = 7; 0.15%, 95% CI 0.06–0.32), E138K + K101E (n = 3; 0.007%, 95% CI 0.014–0.20) and K103N + L100I (n = 2; 0.04%, 95% CI 0.0042–0.124). L100I in combination with K103N causes 10-fold reduced susceptibility to rilpivirine.50

Limitations of the study

Samples used in this study were from 2013–18 before the widespread use of dolutegravir-based ART in Botswana; thus, findings might not be representative of the current prevalence of RPV-RAMs in Botswana. However, since ART rollout during this period in Botswana was quite high,51 it is unlikely that there is much difference in the archived HIV-1 mutations in the samples from the study period and now. Our analysis only focused on RPV-RAMs and did not include cabotegravir RAMs (CAB-RAMs), as very few participants in the BCPP had ever been exposed to an INSTI-containing regimen and it is unlikely that there were any major CAB-RAMs in the study population. The lack of analysis for HIV minority variants could be a limitation of our study as we could have underreported the prevalence of the RPV-RAMs. Lastly, in the BCPP study, ART exposure was only confirmed verbally by participants, which may have resulted in an overestimation of ART-naive individuals (who had not declared their ART history).52

Conclusions

Our study provides the first data for archived RPV-RAMs in ART-naive and ART-suppressed individuals in Botswana. We identified a moderate prevalence of RPV-RAMs that was similar to other regions and other HIV subtypes: 10.7% in ART-naive and 13.7% in ART-suppressed PWH in Botswana. Most RPV-RAMs were the result of an E138A mutation. Since individuals with the E138A mutation may be more likely to fail cabotegravir/rilpivirine, monitoring of this mutation will be crucial for effective cabotegravir/rilpivirine implementation in this setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study participants who took part in the BCPP study. We thank the BCPP study team for their contribution to this study. We gratefully acknowledge the Ministry of Health and Wellness, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, CDC Botswana and US CDC for their excellent support and contributions to the study. We appreciate the contributions of the PANGEA-HIV Consortium Steering Committee (Helen Ayles, Lucie Abeler-Dörner, David Bonsall, Rory Bowden, Max Essex, Sarah Fidler, Christophe Fraser, Kate Grabowski, Tanya Golubchik, Ravindra Gupta, Richard Hayes, Joshua Herbeck, Joseph Kagaayi, Pontiano Kaleebu, Jairam Lingappa, Vladimir Novitsky, Sikhulile Moyo, Deenan Pillay, Thomas Quinn, Andrew Rambaut, Oliver Rat- mann, Janet Seeley, Deogratius Ssemwanga, Frank Tanser and Maria Wawer) for generation of HIV sequences used for this paper.

Contributor Information

Dorcas Maruapula, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana.

Natasha O Moraka, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical Laboratory Sciences, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana.

Ontlametse T Bareng, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical Laboratory Sciences, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana.

Patrick T Mokgethi, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Faculty of Science, Biological Sciences, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana.

Wonderful T Choga, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical Laboratory Sciences, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana.

Kaelo K Seatla, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana.

Nametso Kelentse, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana.

Catherine K Koofhethille, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Boitumelo J L Zuze, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana.

Tendani Gaolathe, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana.

Molly Pretorius-Holme, Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Joseph Makhema, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Vlad Novitsky, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana.

Roger Shapiro, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Sikhulile Moyo, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Shahin Lockman, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Division of Infectious Disease, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Simani Gaseitsiwe, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Funding

S.M., S.G., W.T.C. and N.O.M. are partly supported through the Sub-Saharan African Network for TB/HIV Research Excellence (SANTHE 2.0) from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (INV- 033558). The BCPP Impact Evaluation was supported by the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, cooperative agreements U01 GH000447 and U2G GH001911). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. D.M. was supported by the Fogarty International Center (grant no. 5D43TW009610). S.M. was supported by the Fogarty International Center (grant IK43TW012350-01). S.G. and W.T.C. were partially supported by H3ABioNet. H3ABioNet is supported by the National Institutes of Health Common Fund (U41HG006941). H3ABioNet is an initiative of the Human Health and Heredity in Africa Consortium (H3Africa) programme of the African Academy of Science (AAS). S.M., N.K. and O.T.B. were supported by the Trials of Excellence in Southern Africa (TESA III), which is part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union (grant CSA2020NoE-3104 TESAIII CSA2020NoE). K.K.S. is supported by an Africa Research Excellence Fund Research Development Fellowship (reference AREF-312-SEAT-F-C0927). PANGEA-HIV is funded primarily by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMFG). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of PEPFAR, CDC, AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust or the UK government. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and decision to publish, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Transparency declarations

All authors declare no financial or any other conflicts of interest associated with the study. The funders played no role in the conduct of the study and the writing of the current manuscript. No professional medical writer or similar service was engaged for the manuscript.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the paper and the Supplementary data, Figures and Tables. HIV-1 sequences are available on request through the PANGEA consortium (www.pangea-hiv.org). BCPP data are available at https://data.cdc.gov/Global-Health/Botswana-Combination-Prevention-Project-BCPP-Publi/qcw5-4m9q.

Supplementary data

Tables S1 is available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. UNAIDS. 2022 Global AIDS Update: In Danger. 2022.https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2022-global-aids-update-summary_en.pdf.

- 2. Mine M. Botswana Achieved the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 95-95-95 targets: results from the fifth Botswana HIV/AIDS Impact Survey (BAIS V). 24th International AIDS Conference, Montreal, Canada, 2021. Abstract PELBC01.

- 3. Bares SH, Scarsi KK. A new paradigm for antiretroviral delivery: long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine for the treatment and prevention of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2022; 17: 22. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Orkin C, Arasteh K, Górgolas Hernández-Mora Met al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine after oral induction for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1124–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1909512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Swindells S, Andrade-Villanueva J-F, Richmond GJet al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance of HIV-1 suppression. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1112–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa1904398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. ViiV Healthcare . Cabenuva® Prescribing Information. 2021. https://viivhealthcare.com/content/dam/cf-viiv/viivhealthcare/en_US/pdf/viiv-cabenuva-e2m-fda-approval-dosing-infographic-31-mar-2022.pdf.

- 7. US FDA . Vocabria for the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection.https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv/fda-approves-cabenuva-and-vocabria-treatment-hiv-1-infection.

- 8. Parker B. Cabotegravir + rilpivirine for HIV-1 treatment: improved adherence, better outcomes, lower cost. PharmacoEconomics Outcomes News 2021; 872: 7–20. 10.1007/s40274-021-7480-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cutrell AG, Schapiro JM, Perno CFet al. Exploring predictors of HIV-1 virologic failure to long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine: a multivariable analysis. AIDS 2021; 35: 1333. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Overton ET, Richmond G, Rizzardini Get al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine dosed every 2 months in adults with human immunodeficiency virus 1 type 1 (HIV-1) infection: 152-week results from ATLAS-2M, a randomized, open-label, phase 3b, noninferiority study. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76: 1646–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32666-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kityo C, Cortes CP, Phanuphak Net al. Barriers to uptake of long-acting antiretroviral products for treatment and prevention of HIV in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75: S549–S56. 10.1093/cid/ciac752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. da Silva J, Siedner M, McCluskey Set al. Drug resistance and use of long-acting ART. Lancet HIV 2022; 9: e374–e5. 10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00059-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Derache A, Shin H-S, Balamane Met al. HIV drug resistance mutations in proviral DNA from a community treatment program. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0117430. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Banks L, Gholamin S, White Eet al. Comparing peripheral blood mononuclear cell DNA and circulating plasma viral RNA pol genotypes of subtype C HIV-1. J AIDS Clin Res 2012; 3: 141. 10.4172/2155-6113.1000141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Makhema J, Wirth KE, Pretorius Holme Met al. Universal testing, expanded treatment, and incidence of HIV infection in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 230–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1812281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. ViiV Healthcare . Cabotegravir Extended-release Injectable Suspension; Rilpivirine Extended-release Injectable Suspension (Cabenuva) Prescribing Information. 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/212888s005s006lbl.pdf.

- 17. Moyo S, Gaseitsiwe S, Zahralban-Steele Met al. Low rates of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor drug resistance in Botswana. AIDS 2019; 33: 1073. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pineda-Peña A-C, Faria NR, Imbrechts Set al. Automated subtyping of HIV-1 genetic sequences for clinical and surveillance purposes: performance evaluation of the new REGA version 3 and seven other tools. Infect Genet Evol 2013; 19: 337–48. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Struck D, Lawyer G, Ternes A-Met al. COMET: adaptive context-based modeling for ultrafast HIV-1 subtype identification. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42: e144. 10.1093/nar/gku739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wensing AM, Calvez V, Ceccherini-Silberstein Fet al. 2022 update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top Antivir Med 2022; 30: 559–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Paredes R, Tzou PL, Van Zyl Get al. Collaborative update of a rule-based expert system for HIV-1 genotypic resistance test interpretation. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0181357. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lansdon EB, Brendza KM, Hung Met al. Crystal structures of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with etravirine (TMC125) and rilpivirine (TMC278): implications for drug design. J Med Chem 2010; 53: 4295–9. 10.1021/jm1002233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Singh K, Marchand B, Rai DKet al. Biochemical mechanism of HIV-1 resistance to rilpivirine. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 38110–23. 10.1074/jbc.M112.398180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang W, Gamarnik A, Limoli Ket al. Amino acid substitutions at position 190 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase increase susceptibility to delavirdine and impair virus replication. J Virol 2003; 77: 1512–23. 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1512-1523.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ren J, Nichols CE, Chamberlain PPet al. Crystal structures of HIV-1 reverse transcriptases mutated at codons 100, 106 and 108 and mechanisms of resistance to non-nucleoside inhibitors. J Mol Biol 2004; 336: 569–78. 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ren J, Nichols CE, Chamberlain PPet al. Relationship of potency and resilience to drug resistant mutations for GW420867X revealed by crystal structures of inhibitor complexes for wild-type, Leu100Ile, Lys101Glu, and Tyr188Cys mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptases. J Med Chem 2007; 50: 2301–9. 10.1021/jm061117m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Das K, Arnold E. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and antiviral drug resistance. Part 2. Curr Opin Virol 2013; 3: 119–28. 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wöhrl BM, Krebs R, Thrall SHet al. Kinetic analysis of four HIV-1 reverse transcriptase enzymes mutated in the primer grip region of p66: implications for DNA synthesis and dimerization. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 17581–7. 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rose PP, Korber BT. Detecting hypermutations in viral sequences with an emphasis on G → A hypermutation. Bioinformatics 2000; 16: 400–1. 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.4.400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Theys K, Van Laethem K, Gomes Pet al. Sub-epidemics explain localized high prevalence of reduced susceptibility to rilpivirine in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected patients: subtype and geographic compartmentalization of baseline resistance mutations. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016; 32: 427–33. 10.1089/aid.2015.0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cecchini DM, Zapiola I, Rodriguez CGet al. Rilpivirine resistance associated mutations in HIV-1 infected pregnant women. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2015; 33: 498–9. 10.1016/j.eimc.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steegen K, Chandiwana N, Sokhela Set al. Impact of rilpivirine cross-resistance on long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine in low and middle-income countries. AIDS 2023; 37: 1009–11. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000003505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gallien S, Charreau I, Nere MLet al. Archived HIV-1 DNA resistance mutations to rilpivirine and etravirine in successfully treated HIV-1-infected individuals pre-exposed to efavirenz or nevirapine. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70: 562–5. 10.1093/jac/dku395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. James MK, Anne WT, Viviene Met al. Rilpivirine and etravirine resistance among HIV-1 infected patients failing first generation non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) in Busia, Western Kenya. Int J Biotechnol Mol Biol Res 2021; 11: 10–8. 10.5897/IJBMBR2021.0318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salou M, Dagnra AY, Butel Cet al. High rates of virological failure and drug resistance in perinatally HIV-1-infected children and adolescents receiving lifelong antiretroviral therapy in routine clinics in Togo. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19: 20683. 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Muri L, Gamell A, Ntamatungiro AJet al. Development of HIV drug resistance and therapeutic failure in children and adolescents in rural Tanzania: an emerging public health concern. AIDS 2017; 31: 61. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Neogi U, Anita S, Shamsundar Ret al. Selection of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-associated mutations in HIV-1 subtype C: evidence of etravirine cross-resistance. AIDS 2011; 25: 1123.–6. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328346269f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. James C, Preininger L, Sweet M. Rilpivirine: a second-generation nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2012; 69: 857–61. 10.2146/ajhp110395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Imaz A, Podzamczer D. The role of rilpivirine in clinical practice: strengths and weaknesses of the new nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor for HIV therapy. AIDS Rev 2012; 14: 268–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Porter DP, Kulkarni R, Fralich Tet al. Characterization of HIV-1 drug resistance development through week 48 in antiretroviral naive subjects on rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF or efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF in the STaR study (GS-US-264-0110). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 65: 318–26. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Antinori A, Zaccarelli M, Cingolani Aet al. Cross-resistance among nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors limits recycling efavirenz after nevirapine failure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2002; 18: 835–8. 10.1089/08892220260190308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rizzardini G, Overton ET, Orkin Cet al. Long-acting injectable cabotegravir + rilpivirine for HIV maintenance therapy: week 48 pooled analysis of phase 3 ATLAS and FLAIR trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020; 85: 498. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nguyen H, Thorball CW, Fellay Jet al. Systematic screening of viral and human genetic variation identifies antiretroviral resistance and immune escape link. Elife 2021; 10: e67388. 10.7554/eLife.67388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gatanaga H, Murakoshi H, Hachiya Aet al. Naturally selected rilpivirine-resistant HIV-1 variants by host cellular immunity. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57: 1051–5. 10.1093/cid/cit430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Calvez V, Marcelin A-G, Vingerhoets Jet al. Systematic review to determine the prevalence of transmitted drug resistance mutations to rilpivirine in HIV-infected treatment-naive persons. Antivir Ther 2016; 21: 405–12. 10.3851/IMP3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Diphoko T, Gaseitsiwe S, Kasvosve Iet al. Prevalence of rilpivirine and etravirine resistance mutations in HIV-1 subtype C-infected patients failing nevirapine or efavirenz-based combination antiretroviral therapy in Botswana. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2018; 34: 667–71. 10.1089/aid.2017.0135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sluis-Cremer N, Jordan MR, Huber Ket al. E138a in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase is more common in subtype C than B: implications for rilpivirine use in resource-limited settings. Antivir Res 2014; 107: 31–4. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Overton ET, Richmond G, Rizzardini Get al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine dosed every 2 months in adults with HIV-1 infection (ATLAS-2M), 48-week results: a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3b, non-inferiority study. Lancet 2020; 396: 1994–2005. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32666-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tambuyzer L, Nijs S, Daems Bet al. Effect of mutations at position E138 in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase on phenotypic susceptibility and virologic response to etravirine. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 58: 18–22. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182237f74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Melikian GL, Rhee S-Y, Varghese Vet al. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) cross-resistance: implications for preclinical evaluation of novel NNRTIs and clinical genotypic resistance testing. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69: 12–20. 10.1093/jac/dkt316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gaolathe T, Wirth KE, Holme MPet al. Botswana's progress toward achieving the 2020 UNAIDS 90-90-90 antiretroviral therapy and virological suppression goals: a population-based survey. Lancet HIV 2016; 3: e221–e30. 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)00037-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Moyo S, Gaseitsiwe S, Powis KMet al. Undisclosed antiretroviral drug use in Botswana—implication for national estimates. AIDS 2018; 32: 1543. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and the Supplementary data, Figures and Tables. HIV-1 sequences are available on request through the PANGEA consortium (www.pangea-hiv.org). BCPP data are available at https://data.cdc.gov/Global-Health/Botswana-Combination-Prevention-Project-BCPP-Publi/qcw5-4m9q.