HIGHLIGHTS

-

•

Poor mental health is on the rise in the U.S.

-

•

Mental health is the presence of well-being and control of distressing symptoms.

-

•

Bolstering well-being is primary and secondary prevention for poor mental health.

-

•

There are validated exercises that can help patients to cultivate mental well-being.

-

•

There is good evidence to support a public health approach to mental health care.

Keywords: Mental health, primary prevention, secondary prevention, mental well-being, value-based care, positive psychology

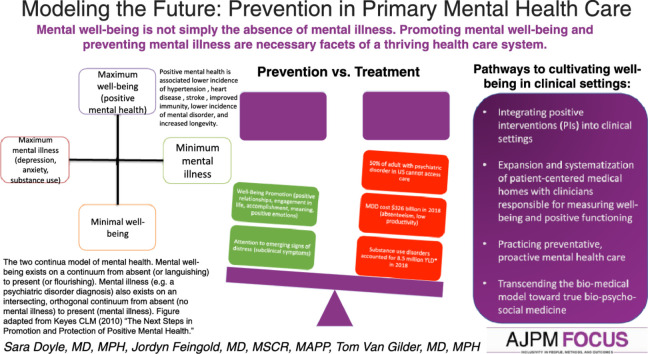

Graphical Abstract

Abstract

Introduction

Adults in the U.S. have had poor and worsening mental health for years. Poor mental health exacts a high human and economic cost.

Methods

Using PubMed, we conducted a focused narrative literature review on mental well-being and its role in mental and physical health care.

Results

Mental well-being is essential for mental and physical health. High mental well-being is associated with a lower incidence of psychiatric disorder diagnosis and better function for those who do carry a formal diagnosis. High mental well-being also improves health outcomes for several physical diseases. Cultivating mental well-being is both a primary and secondary prevention strategy for mental and physical illness. There is a growing number of low-cost and accessible interventions to promote mental well-being, rooted in the research of positive psychology. These interventions improve mental well-being in multiple populations from different cultural backgrounds. There have been some efforts to incorporate these interventions to improve mental well-being in the clinical setting.

Conclusions

Our mental healthcare system would substantially improve its ability to protect against mental illness and promote positive function if mental well-being was routinely measured in the clinical setting, and interventions to improve mental well-being were routinely incorporated into standard primary and specialty care.

INTRODUCTION

Although the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic brought unprecedented national attention to social isolation, mental health, suicide, and psychological well-being, the mental health of adults in the U.S. remains poor and is worsening. Over the last decade, the incidence of mood disorders, substance use disorders, and suicide have all increased, as have subclinical symptoms of psychological distress.1 Researchers cite many cultural and societal factors such as financial stress, political division, and high social media use as contributors to this trend.1,2

Mental illness exacts a high cost on human life and human potential. In 2016 alone, substance use disorders and mental illness together accounted for nearly 8.5 million years lived with disability.3 Furthermore, the dollar cost of mental illness is immense. In 2018 alone, the cost of major depressive disorder in the U.S. was $326 billion. This cost estimate includes direct medical expenses and indirect expenses from work absenteeism and presenteeism.4 However, these ICD-10–based cost analyses do not include the rising proportion of adults with symptoms of poor mental health that are subthreshold of a formal diagnosis. These lower grades and persistent symptoms likely take a significant economic toll.

Our current mental healthcare system cannot meet the growing demand for care. Among persons who survived attempted suicide in the past year—an event that carries up to a 3% mortality rate in the year after—nearly half reported an inability to access mental health services.5 Along similar lines, about 50% of adults with a psychiatric disorder in the U.S. receive inadequate care or are unable to access treatment altogether.6 Currently, primary care physicians provide a substantial portion of mental health care but are unsupported in both time and resources.2

Health and healthcare policy leaders recognize these gaps, and there have been some efforts to expand and improve access to mental health care under our current model. One is training more mental healthcare professionals, including psychiatrists.7 Regarding policy, the 2008 Wellstone Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act was a significant first step to improving insurance coverage for mental and behavioral health services. However, the implementation of this law has been suboptimal because of poor enforcement.8 A promising step toward improving access is telehealth expansion.9 Interestingly, 96% of psychologists surveyed by the American Psychological Association report that telehealth is equally effective and support its continuation even as pandemic restrictions ease.10

Improving access is necessary and important work that must continue. Similar to other medical conditions with high prevalence and high morbidity, treatment alone is insufficient to improve and protect our nation's mental health. Interventions to improve access to mental health care once symptoms have reached the level of a diagnosis are downstream interventions; this limited focus misses vital opportunities to prevent severe mental illness and further stresses the limited resources of our current healthcare system. We acknowledge practical barriers to enacting prevention models.11 The system change required to enact effective preventive policies and care for any health condition is significant and beyond the scope of this review. In this paper, we will summarize the evidence that supports a public health approach to mental health and its care, review evidence-based tools to do this in clinical practice with positive interventions (PIs), discuss examples of current work in this area, and conclude with recommendations for moving more work from theory to practice.

METHODS

This is a narrative review, inspired by the authors’ collective interest in mental health care and multidisciplinary content area expertise in preventive medicine, neurology, psychiatry, positive psychology, public health, and internal medicine. In addition, the 2 continua model of mental health12,13 (Figure 1) and its applicability to a public health approach (i.e., care alongside health promotion and illness prevention) informed the framing of this review. The literature review was conducted using PubMed database with the following MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms: anxiety, depression, suicide, epidemiology, cost of illness, economics, health policy, mental health, psychological well-being, positive psychology, preventive medicine, primary prevention, health promotion, social support, cognitive behavioral therapy, risk factors, hospitalization, health status, poverty, physical health, and incidence. These search terms were also supplemented with keywords: preventive mental health care, public health, biopsychosocial, psychoneuroimmunology, salutogenesis, positive psychology interventions, and flourishing. Research was supplemented with a review of publications on professional organization websites because this informs current work and policy (e.g., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, American Psychological Association, UC-Berkeley Greater Good Science Center). We summarized the results and reported them in a public health framework. First, we describe the problem, present a universal case definition, and outline the evidence for effective health promotion and disease prevention. Given these results, we conclude that a public health/preventive approach to mental health care is possible and discuss current work in this area and further areas of expansion.

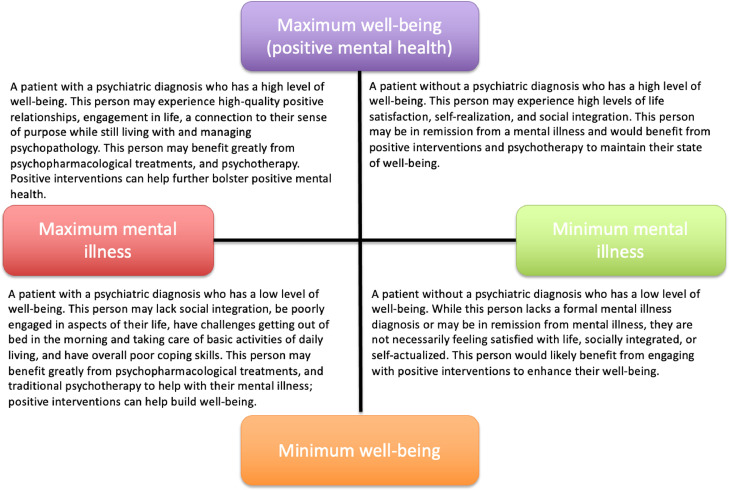

Figure 1.

The 2 continua model of mental health. Mental well-being exists on a continuum from absent (or languishing) to present (or flourishing). Mental illness (e.g., a psychiatric disorder diagnosis) also exists on an intersecting, orthogonal continuum from absent (no mental illness) to present (mental illness). The figure was adapted from Keyes 2010.13 This figure has been updated to capture the spectra of function within each quadrant and to include the flourishing and languishing terminology. This can be found in Keyes 2013 Promoting and Protecting Positive Mental Health: Early and Often Throughout the Lifespan. We maintain this figure for simplicity and to keep the clinical descriptions.

RESULTS

Mental Well-Being Is Not the Absence of Mental Illness

The first step to a public health approach is to define mental health. Mental health requires mental well-being. Mental well-being is not the absence of mental illness; it is the summative degree of emotional, psychological, and social well-being.12,14 Research from multiple disciplines supports this concept. For preventive medicine and a public health approach, the independence of mental well-being reframes mental health care and is an untapped opportunity for health promotion for the whole population.

The idea that mental well-being is independently important arose consistently over the course of the 20th century. Thought leaders and scientists from multiple disciplines put forth frameworks of health and health care that explicitly recognized the presence, influence, and necessity of the positive or resilient qualities of human beings for complete human health. In other words, health is not the absence of dysfunction. From a medical perspective, George Engel's biopsychosocial model reframed the biomedical model, elevating the importance of the patient's internal and external environment on their health. The model emphasizes the physician's duty to consider these contexts when treating the patient.15 In the 1970s, the field of psychoneuroimmunology grew as researchers studied how stress pathway activation in the central nervous system affects both immune and endocrine systems, mediating various states of health and disease. These studies grew out of clinical observations that psychological ill-health had a deleterious effect on outcomes in patients with cancer, and a better psychosocial milieu conferred a survival benefit.16 In other words, mental well-being is necessary for full health. Concurrently, Israeli-American medical sociologist Aaron Antonovsky introduced his framework of salutogenesis, which asserts that health is achieved not by eliminating disease but by cultivating a person's internal and external psychosocial resources to understand, manage, and find meaning in one's life, leading to resilience and better health.17 In psychology, an early pioneer of independently promoting mental well-being and positive function—as opposed to just eliminating mental illness symptoms—was psychologist Marie Jahoda. She published Positive Mental Health in 1958 outlining 6 internal processes that lead to better mental health. These include self-compassion, personal growth, the integration of psychological function, autonomy, an accurate perception of reality, and environmental mastery.18 Decades later, stemming from years of research on positive traits, positive psychology coalesced as a discipline and empirical science focused on the part of the human experience that is “metaphorically north of neutral…. [and] what is good about life is as genuine as what is bad and therefore deserves equal attention from psychologists…. [L]ife entails more than avoiding or undoing the hassles.” These studies provide the foundation for positive interventions (discussed later), which operationalize mental health promotion.18

Of course, the sole focus on mental well-being is incomplete—achieving mental health requires the presence of mental well-being and management of mental illness symptoms, if present. Developed by CL Keyes, the 2 continua model contends that mental well-being and mental illness are related but distinct phenomena existing on independent axes (Figure 1).12 The model is helpful to visually conceptualize a holistic approach to mental health care. Importantly, the 2 continua model of mental health has been replicated in several different populations.13

Mental Well-Being Is Independent and Independently Important for Physical and Mental Health

A holistic definition is important, but to support a public health approach to mental health care, the second important finding from our literature review is that mental well-being is independently important for mental and physical health. Mental well-being improves function for individuals regardless of the presence or absence of a psychiatric disorder. After all, function—the ability to work and carry out activities of daily living—matters to mitigate the economic and human cost of poor mental health. Adults who are languishing (i.e., have low mental well-being but do not meet clinical criteria for a psychiatric disorder) can function as poorly as adults with a formal diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder.12 Cultivating mental well-being can alleviate symptoms of mental illness and strengthen recovery for individuals with a range of mental illnesses from depression to eating disorders to schizophrenia.12,19,20

Promoting mental well-being also has physical health benefits, pointing to the increasingly antiquated notion of separating mind and body in our current healthcare system. Many longitudinal observational and experimental studies observe that mental well-being is linked to better health outcomes such as lower incidence of hypertension,21 heart disease,22 stroke23; improved immunity24; and increased longevity.13,14,25,26 Psychoneuroendocrinology and positive neuroscience research complement these observations to provide the biological and neuroanatomical basis for these findings.27,28 With this evidence that mental well-being alleviates symptoms and improves function for both physical and psychiatric disorders, it follows that promoting and cultivating mental well-being is an effective and underutilized strategy for secondary prevention.

Finally and most important from a public health and preventive medicine standpoint, a growing body of evidence shows that high levels of mental well-being can prevent some psychiatric disorders altogether.14,19,29,30 In a 3-year study of adults, those who were flourishing—that is, adults with high levels of mental well-being—had 30% lower odds of incident mood disorder over the course of the 3-year study period.29 Other studies have observed similar results.19 Thus, cultivating mental well-being offers an avenue for primary prevention of mental illness and effective secondary prevention to improve function in the event of a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder. Promoting mental well-being is preventive medicine.

Cultivating Mental Well-Being in the Clinical Setting

Finally, our literature review revealed a substantial evidence base for how clinicians can educate and help patients to cultivate mental well-being regularly as a preventive health practice. This can be done with PIs. PIs are intentional practices or exercises to cultivate mental well-being and its associated states—hope, optimism, purpose, positive relationships, and self-efficacy—both internally and interpersonally (Table 1).12,14,25 These interventions grew out of positive psychology research.14 Validated scales to measure efficacy are widely available.2 Once taught, these self-directed exercises can be incorporated into one's daily life analogous to consistent physical exercise.

Table 1.

Short List of Validated Interventions to Cultivate Mental Well-Being Targets

| Intervention | Mental well-being target(s) |

|---|---|

| Exercise example | |

| Gratefulness practice | Positive emotion |

| Gratitude journal | Positive relationships |

| Three good things exercise | Accomplishment |

| Letter of gratitude | Meaning |

| Active constructive responding | Positive emotion |

| Active listening to recreate positive emotions | Positive relationships |

| Active listening to recreate positive experience | |

| Acts of kindness | Positive emotion |

| Giving to others in a sustainable way | Positive relationships |

| Engagement | |

| Identifying and using character strengths | Positive emotions |

| Identify character strengths in self | Accomplishment |

| Identify character strengths in others | Meaning |

| Positive relationships | |

| SMART goal setting | Accomplishment |

| Identifying goal and action plan | Engagement |

| Meaning | |

| Positive relationships | |

| Values-based practices | Meaning |

| Identify core values | Engagement |

| Accomplishment | |

| Savoring practices | Positive emotions |

| Mindfulness practice | Engagement |

| Meaning |

Note: The 2 continua model broadly defines well-being as emotional, psychological, and social well-being; In PI research, investigators concretely define components of these pillars as positive emotions, positive relationships, engagement in life, accomplishment, meaning.12,14,25

PI, positive intervention; SMART, specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

There is growing evidence that PIs improve mental well-being and function in clinical populations, nonclinical populations, and non-Western cultures. Most studies of PIs are in adults and in a nonclinical population. In the U.S., many studies show the impacts of positive emotions and positive states on mood, cognition, and life satisfaction.14,25,31 Among adults in Brazil, the practice of a gratitude exercise for 2 weeks increased life satisfaction and happiness scores and decreased depression symptoms for the intervention group compared with that in the control group.32 For children living in a migratory slum in India, participation in a 6-month positive psychology curriculum that taught various positive interventions led to increased happiness, empathy, curiosity, a sense of meaning in life, and a positive life orientation.33 Current research is now focused on the assessment and applicability of PIs across cultures, acknowledging that individual and interpersonal values can be culturally dependent.34 In clinical populations, there is emerging evidence that PIs reduce symptoms and improve well-being or both. For patients with severe depression, a trial compared positive interventions with cognitive behavioral therapy—the gold standard of care—and there was a similar reduction in depressive symptoms and improvement in positive functioning for both groups.19 For patients with schizophrenia, PIs may bolster feelings of well-being.35 There have been a few pilot trials of PIs for treatment of substance use disorders, but this remains a gap in research. It bears noting that central tenets of recovery movements overlap with tenets of positive psychology and positive interventions such as gratitude, finding purpose in life, and service to others.

Finally, acceptability and sustainability are 2 key points to consider for any new intervention. Patients already intuit the mental health–protecting and –promoting effect of mental well-being. This is poignantly illustrated by the well-established protective factors against death by suicide: social connectedness, a religious or spiritual orientation, possessing coping and problem-solving skills, and a sense of life purpose. When asked about fundamental characteristics of remission, patients with major depression cite the presence of optimism and a sense of well-being.19 Similarly, patients with eating disorders identify positive relationships, self-acceptance, and mental resilience as fundamental aspects of their recovery.36 In a group of patients with depression, those who used positive interventions reported that the PIs are more accessible and transportable and less stigmatizing than more traditional psychotherapy.37 PIs can, of course, complement psychotherapy. Positive interventions are also likely to be reinforcing and self-sustaining. The established and validated broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions posits that individuals who are taught to self-generate authentic, contextually appropriate positive emotions are more likely to experience positive emotions, better physical health, and broad coping skills in the future.31 Positive begets positive.

DISCUSSION

Current Work

We contend that attention to and cultivation of mental well-being has the potential to improve population health. Yet, it remains an underutilized strategy of the U.S. healthcare and public health system. However, there are movements in this direction. Some clinics in the U.S. explicitly incorporate mental well-being promotion into their practice. More often, this occurs in clinics attending to specific diseases that are generally accepted to have a stress-related component such as inflammatory bowel disease or migraine headache. Keefer et al.38 tested a holistic care program, rooted in positive health psychology, for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. The holistic care program involved meetings with a social worker and engagement in positive interventions. Patients who participated in the program had higher resilience scores, lower healthcare utilization, and lower use of corticosteroids and opioids after 12 months than control patients who received usual care. Lifestyle medicine clinics and some modes of behavioral health counseling (e.g., motivational interviewing) often employ tenets of positive psychology and positive interventions as well. The rise of patient-centered medical homes reflects evidence that health outcomes improve with integration of services that promote well-being, whether that is behavioral health or ensuring housing and food security.

Beyond the Clinic: Scaling the System to Value Mental Well-Being

We applaud this work to integrate well-being into the American healthcare system. We call for its expansion and systematization. Presently, our healthcare system struggles to incorporate mental well-being into care. Fundamentally, this is a values issue. By this, we mean value as both a core belief and a financial priority. If a budget is a moral document, these are no different. Our healthcare system does not value well-being nor does it value prevention or proactive care.

One way to give value to well-being is to measure it. The current basis of our mental healthcare system is The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. The DSM is an inventory of diagnoses defined by clusters of symptoms of poor function (e.g., emotions, behaviors, and experiences). Intuitively, this is an incomplete concept of human health and functioning. We want to emphasize in this paper that we are talking about the healthcare system and not individual providers. We know that providers understand the multidimensionality of the human experience and that restoring someone to health is more than eliminating their disease. However, there is no corresponding systematic way to track and chronicle positive function or well-being. Our healthcare system maintains a disease-centered focus because the only standard measurement tool is a catalog of disease and dysfunction. Measuring positive function and well-being systemically is possible. In fact, some governments track national well-being as a measure of the nation's overall health and as an economic indicator.39 Within health care, there are many validated scales or varying lengths and scopes. Selection of a scale for systematic measurement (and reimbursement) would require expert consensus, but policy and practice will follow what we measure, and measuring well-being is possible.40

Another way to give value to well-being is to value prevention. As discussed earlier, cultivating mental well-being is a preventive approach to mental health care. High mental well-being can be both primary prevention against a psychiatric disorder and secondary prevention to improve function with a diagnosis. However, in the U.S. healthcare system, prevention is a paradox; prevention is touted in rhetoric but not prioritized in practice. When done well, prevention has invisible and undramatic results with often very delayed financial gratification for the payer. It is difficult to make prevention a priority in our current system.11 Improving and standardizing measurements of well-being is a part of this greater conversation about financially incentivizing prevention within our healthcare system.

We must also consider whether our current healthcare system can reach a wider audience, with or without enhanced payment models, increased access, or a broader workforce. Employers play a role in funding health care through health insurance offerings but also in workplace well-being, wellness, and even direct clinical offerings. Incentivizing employers to offer both mental illness coverage and mental well-being programs might also have a place in scaling population mental well-being and fitness.

Limitations

This was not a scoping or systematic review of the literature. While the relevance of each study selected for this review was assessed by consensus of this author team based on collective clinical, epidemiological and clinical research experience, this is not without bias or omission. Additionally, the notion of prevention in mental health care is a relatively new concept which is inherently limited by physiologic understanding of mental illness itself. As such, the quality of studies reviewed may be poor, as they are often limited to small, non-representative samples or observational designs.

CONCLUSIONS

U.S. adults are languishing, and this has profound consequences. To improve mental health in this country, we must systematically expand how our healthcare system defines mental health, remove the siloes of its management, and integrate mental health care into a wider array of clinical settings. This can be achieved with a public health approach, but as with all preventive efforts, this is fundamentally a values issue—we must value well-being in our measurement systems so that it can be tracked and incentivized. Some countries already track national well-being and happiness as they do other economic indicators. The private sector has recognized this gap in health care and invested billions in the last year.41 Where is medicine? We must have the humility to recognize the gaps in the current system and professional integrity to collaborate with psychology, neuroscience, and public health to expand the focus of mental health and its care to interventions that take a broader public health approach to cultivate mental well-being and improve function.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

TJVG is employed as Chief Health Officer for BetterUp, Inc. SJD and JHF serve as consultants to BetterUp, Inc.

Declaration of interest: none.

CRediT AUTHOR STATEMENT

Sara J. Doyle: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Jordyn H. Feingold: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Thomas J. Van Gilder: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodwin RD, Weinberger AH, Kim JH, Wu M, Galea S. Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: rapid increases among young adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;130:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncan AR, Daugherty G, Carmichael G. An emerging preventive mental health care strategy: the neurobiological and functional basis of positive psychological traits. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.728797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators. Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, et al. The state of U.S. health, 1990–2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among U.S. states. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1444–1472. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018) Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(6):653–665. doi: 10.1007/s40273-021-01019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bommersbach TJ, Rosenheck RA, Rhee TG. National trends of mental health care among U.S. adults who attempted suicide in the past 12 months. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(3):219–231. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prevalence data 2022. Mental Health America. https://mhanational.org/issues/2022/mental-health-america-prevalence-data. Updated October 19, 2021. Accessed July 24, 2022.

- 7.Weiner S. Addressing the escalating psychiatrist shortage. AAMC. 2018 https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/addressing-escalating-psychiatrist-shortage February 12, [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rochefort DA. The Affordable Care Act and the faltering revolution in behavioral health care. Int J Health Serv. 2018;48(2):223–246. doi: 10.1177/0020731417753674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarado HA. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2021. Telemedicine services in substance use and mental health treatment facilities.https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/telemedicine-services Published December 29, 2021, Accessed July 24, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clay R. Telehealth proves its worth. Am Psychol Assoc Trends Rep. 2022;1:85. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/01/special-telehealth-worth [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fineberg HV. The paradox of disease prevention: celebrated in principle, resisted in practice. JAMA. 2013;310(1):85–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westerhof GJ, Keyes CL. Mental illness and mental health: the two continua model across the lifespan. J Adult Dev. 2010;17(2):110–119. doi: 10.1007/s10804-009-9082-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keyes CL. The next steps in the promotion and protection of positive mental health. Can J Nurs Res. 2010;42(3):17–28. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-21950-003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seligman MEP. Positive health. Appl Psychol. 2008;57(s1):3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00351.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borrell-Carrió F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):576–582. doi: 10.1370/afm.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tausk F, Elenkov I, Moynihan J. Psychoneuroimmunology. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(1):22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindström B, Eriksson M. Salutogenesis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(6):440–442. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.034777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson C. Psychology. Oxford University Press; Oxford, United Kingdom: 2006. A Primer in Positive.https://global.oup.com/ushe/product/a-primer-in-positive-psychology-9780195188332?cc=us&lang=en& [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaves C, Lopez-Gomez I, Hervas G, Vazquez C. A comparative study on the efficacy of a positive psychology intervention and a cognitive behavioral therapy for clinical depression. Cognit Ther Res. 2017;41(3):417–433. doi: 10.1007/s10608-016-9778-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Vos JA, LaMarre A, Radstaak M, Bijkerk CA, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ. Identifying fundamental criteria for eating disorder recovery: a systematic review and qualitative meta-analysis. J Eat Disord. 2017;5:34. doi: 10.1186/s40337-017-0164-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubzansky LD, Boehm JK, Allen AR, et al. Optimism and risk of incident hypertension: a target for primordial prevention. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e157. doi: 10.1017/S2045796020000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boehm JK, Peterson C, Kivimaki M, Kubzansky L. A prospective study of positive psychological well-being and coronary heart disease. Health Psychol. 2011;30(3):259–267. doi: 10.1037/a0023124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim ES, Park N, Peterson C. Dispositional optimism protects older adults from stroke: the health and retirement study. Stroke. 2011;42(10):2855–2859. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segerstrom SC, Sephton SE. Optimistic expectancies and cell-mediated immunity: the role of positive affect. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(3):448–455. doi: 10.1177/0956797610362061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park N, Peterson C, Szvarca D, Vander Molen RJ, Kim ES, Collon K. Positive psychology and physical health: Research and applications. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2014;10(3):200–206. doi: 10.1177/1559827614550277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Millstein RA, von Hippel C, et al. Psychological well-being as part of the public health debate? Insight into dimensions, interventions, and policy. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1712. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-8029-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.González-Díaz SN, Arias-Cruz A, Elizondo-Villarreal B, Monge-Ortega OP. Psychoneuroimmunoendocrinology: clinical implications. World Allergy Organ J. 2017;10(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40413-017-0151-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.S Allen, Positive neuroscience, 2019, John Templetion Foundation; West Conshohocken, PA https://www.templeton.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/White_Paper_Positive_Neuroscience_FINAL.pdf. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed June 12, 2022.

- 29.Schotanus-Dijkstra M, Ten Have M, Lamers SMA, de Graaf R, Bohlmeijer ET. The longitudinal relationship between flourishing mental health and incident mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(3):563–568. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, Boardman S. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675–683. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14nr09599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredrickson BL, Branigan C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn Emot. 2005;19(3):313–332. doi: 10.1080/02699930441000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunha LF, Pellanda LC, Reppold CT. Positive psychology and gratitude interventions: a randomized clinical trial. Front Psychol. 2019;10:584. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundar S, Qureshi A, Galiatsatos P. A positive psychology intervention in a Hindu community: the pilot study of the hero lab curriculum. J Relig Health. 2016;55(6):2189–2198. doi: 10.1007/s10943-016-0289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flores LY, Lee HS. In: Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures. 2nd ed. Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ, editors. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2019. Assessment of positive psychology constructs across cultures; pp. 45–58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pina I, Braga CM, de Oliveira TFR, de Santana CN, Marques RC, Machado L. Positive psychology interventions to improve well-being and symptoms in people on the schizophrenia spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Psychiatry. 2021;43(4):430–437. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohlmeijer E, Westerhof G. The model for sustainable mental health: future directions for integrating positive psychology into mental health care. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.747999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez-Gomez I, Chaves C, Hervas G, Vazquez C. Comparing the acceptability of a positive psychology intervention versus a cognitive behavioural therapy for clinical depression. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2017;24(5):1029–1039. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keefer L, Gorbenko K, Siganporia T, et al. Resilience-based integrated IBD care is associated with reductions in health care use and opioids. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1831–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Measuring the well-being of nations. Positive Psychology Center. https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/learn-more/measuring-well-being-nations. Updated December 2019. Accessed October 11, 2022.

- 40.VanderWeele TJ, Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Allin P, et al. Current recommendations on the selection of measures for well-being. Prev Med. 2020;133 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubin L. Thomas Insel on science, ZIP code, and future-proofing psychotherapy. Psychotherapy.net.https://www.psychotherapy.net/interview/thomas-insel-science-zip-code-future-proofing-psychotherapy. Published April 28, 2022. Accessed July 24, 2022.