Abstract

Background/purpose

Growing prescription of anticholinergic medications has a critical effect on oral health. A link between anticholinergic medication-induced xerostomia (subjective feeling of oral dryness) and a high Decayed, Missing, and Filled teeth (DMFT) index has been reported in the older population. The purpose of this retrospective study is to determine anticholinergic exposure and prevalence of the most frequently used anticholinergic medications in adults 18–44 years of age, as well as to explore xerostomia and its association with caries status.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective study of adults between the age of 18 and 44 years who received a dental examination between January 2019 and April 2010, at Eastman Institute for Oral Health (EIOH), Rochester, NY. We reviewed the electronic dental charts and medical records of 236 adults with xerostomia.

Results

71% of young adults with xerostomia were prescribed at least five or more medications (polypharmacy), and 85% took at least one anticholinergic drug. The average anticholinergic drug scale (ADS) was 2.93. We found systemic conditions such as cardiac, neurological, and sleep apnea affecting the DMFT index by predicting the caries status (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Anticholinergic exposure and medication-induced xerostomia in younger adults are associated with dental caries and require complex interdisciplinary therapy.

Introduction

Saliva is essential to maintain general well-being. It preserves oropharyngeal health and ensures a good oral health-related quality of life.1 Patients with reduced salivary function present with a range of oral consequences characteristic of xerostomia, the feeling of oral dryness. Xerostomia causes difficulty in mastication, swallowing, and speaking and presents as burning mouth, halitosis, altered taste, dry buccal mucosa, dry lips, candidiasis, and an increment in dental caries.2,3 The symptoms can be caused by dry mouth, characterized by decreased secretion of salivary glands; however, the feeling of oral dryness might present despite adequate salivary gland function. Xerostomia can derive from salivary and systemic conditions, including radiotherapy, salivary gland disorders, viral infections, dehydration, and anxiety, which can cause reversible or temporary changes in salivary function.4 Most frequently, the prescription of certain medications is linked to xerostomia.5

The growing utilization of prescription drugs represents a major issue in the United States,6 as adults use an average of one or more prescription drugs. Prescription drug use increases with age, but recent data indicate an increase in the overall use of prescription drugs and polypharmacy in the younger adult population.7 Accordingly, 27.0% of adolescents aged 12–19 and 46.7% of adults aged 20–59 used prescription drugs in 30 days. The most prescribed medications are central nervous system stimulants for adolescents and antidepressants for young adults (11.4%); both groups of drugs have anticholinergic potentials.8

A large group of medications has anticholinergic potential, which can directly affect saliva production by inhibiting acetylcholine binding to muscarinic receptors in the salivary glands or indirectly by inhibiting acetylcholine in the central nervous system. Salivary glands are exceptionally susceptible to anticholinergics, and oral dryness is the most often reported anticholinergic side effect. The use of multiple drugs may result in pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic drug interactions that intensify anticholinergic side effects.9 Anticholinergic side effects are usually assessed by the anticholinergic burden caused by medications.10 The anticholinergic burden, measured by scales such as the Anticholinergic Drug Scale (ADS), refers to the cumulative effect of taking medications capable of causing an adverse anticholinergic impact.11

Anticholinergic burden at younger ages is seldom reported in the literature. While medication-induced oral dryness has been widely studied in geriatric patients, little is known about the effects of xerostomia on oral health and caries status in younger ages.12 This retrospective study aimed to determine whether xerostomia is associated with medication usage and anticholinergic burden in adults 18–44 years old. We sought to fill a gap in the available clinical evidence as no articles have evaluated the frequency and severity of anticholinergic drug usage in relation to the caries status in non-geriatric patients who suffer from xerostomia.

Materials and methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Subjects Review Board (RSRB) – University of Rochester (RSRB No. 00003301, approved on February 19, 2019). The study involved no more than minimal risk and did not adversely affect participants' rights and welfare; thus, a waiver of informed consent was approved.

Study design

An epidemiological retrospective study was performed on adults between 18 and 44 years, who received a dental examination between January 2019 and April 2010, at Eastman Institute for Oral Health (EIOH). Patients who answered “Yes” to the “Do you have dry mouth?” question in the medical history form at their dental visit were included in the study.

Participants

A convenience sample included two hundred and thirty-six young adults with xerostomia. Inclusion criteria were: patients with xerostomia, 18–44 years; both genders; participants who had a dental examination at the General Dentistry Department at the EIOH; validated information on dosing and route of administration available through electronic health records. Exclusion criteria were: Sj gren's syndrome or other known diseases affecting the salivary glands; past or current head and neck radiation therapy of radioiodine treatment; and current therapy with a cholinergic agonist.

Study variables

We calculated the anticholinergic potency of medications by the anticholinergic drug scale (ADS). Medications were rated as level 0 = no known anticholinergic properties; level 1 = potentially anticholinergic; level 2 = anticholinergic adverse events sometimes noted, usually at excessive doses; and level 3 = markedly anticholinergic. The ADS total score was estimated by the sum of all ratings of the drugs received by the patients.13

We collected the Decayed, Missing, and Filled teeth (DMFT) in the permanent dentition (28 teeth, excluding third molars), which is recommended by WHO as a reliable assessment tool for caries status. In addition, other oral health data were collected as the total number of teeth, use of dentures, smoking, and dry mouth treatment. Covariates included medical conditions and diseases, allergies, sleep apnea, type and total number of different medications, total number of anticholinergic medications, demographic information such as age and race, and ADS.

Statistical analysis

Analyses of descriptive statistics were performed to calculate demographic data using SPSS software. Inferential analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with predicting DMFT based on the medical conditions, smoking (Y/N), gender, age, total number of medications, total number of anticholinergic medications, and ADS. Multiple linear regression was used to test if DMFT could be predicted with medications and anticholinergic burden status. An α level of <0.05 was used to declare significance.

Results

The mean age was 34.25 years (±6.99). The demographics, smoking, and edentulism status of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. Women accounted for two third of the xerostomia cohort, and patients' diversity reflected our clinics' demography with over 20% of Black origin. Partial edentulism and the utilization of removable dentures were correlated with an increased number of anticholinergics taken (P = 0.018 and P = 0.022, respectively). Edentulism also showed an age-related increasing pattern (P = 0.011). The comorbid characteristics were summarized in Table 2, including the most frequently occurring medical diseases, such as psychiatric, musculoskeletal, and gastrointestinal diseases. We found that 91.5% of the patients took at least one medication, and 85.5% of the patients took at least one anticholinergic drug. The specific type of medical conditions, such as allergies, diabetes, dermatological disorders, endocrine diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, sleep apnea, and vascular problems, were significantly correlated with increasing age (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, smoking status, and dental variables among xerostomia patients, ages 18–44 (n = 236).

| Number of patients | Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 167 | 70.8 |

| Male | 68 | 28.8 | |

| Non-binary | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Age (years) | 18–30 | 70 | 29.7 |

| 31–44 | 166 | 70.3 | |

| Race | Black | 51 | 21.6 |

| White | 163 | 69.1 | |

| Other | 22 | 9.3 | |

| Smoking status | Yes | 135 | 57.2 |

| No | 93 | 39.4 | |

| Not responded | 8 | 3.4 | |

| Edentulism: | |||

| Complete | Yes | 19 | 8.1 |

| No | 217 | 91.9 | |

| Partial | Yes | 116 | 49.2 |

| No | 120 | 50.8 | |

| Xerostomia treatment | Yes | 6 | 2.5 |

| No | 230 | 97.5 | |

Table 2.

Medical conditions and diseases of 236 adult xerostomia patients between 18 and 44 years.

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 21 (8.9) | 215 (91.1) |

| Cardiac disease | 11 (4.7) | 225 (95.3) |

| Cancer | 4 (1.7) | 232 (98.3) |

| Developmental disorder (childhood-onset condition) | 5 (2.1) | 231 (97.9) |

| Diabetes | 40 (16.9) | 196 (83.1) |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 56 (23.7) | 180 (76.3) |

| Endocrine disease | 48 (20.3) | 188 (79.7) |

| Infectious disease | 24 (10.2) | 212 (89.8) |

| Musculoskeletal disease | 72 (30.5) | 164 (69.5) |

| Neurological disease | 56 (23.7) | 180 (76.3) |

| Psychiatric disease | 138 (58.5) | 98 (41.5) |

| Respiratory disease | 47 (19.9) | 189 (80.1) |

| Urinary disease | 12 (5.1) | 224 (94.9) |

| Sleep apnea | 27 (11.5) | 209 (88.5) |

| Vascular disease | 41 (17.4) | 195 (82.6) |

n, number of patients; %, absolute frequencies.

Significantly higher ADS scores were found in patients with anemia (P = 0.023), developmental diseases (P = 0.024), gastrointestinal diseases (P < 0.001), musculoskeletal disorders (P < 0.001), neurological diseases (P < 0.001), psychiatric diseases (P < 0.001), and dermatological diseases (P = 0.035). Most frequently used medications with potent anticholinergic activity, including antihistamines, antipsychotics, drugs used in obstructive airway diseases, and urinary spasmolytics, were correlated with higher ADS scores (P < 0.05).

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistical data on caries status and medication use. Polypharmacy was a common condition in 71.6% of the patients. The frequency of anticholinergic polypharmacy (using at least five anticholinergic drugs) was 45.7% among younger adults with xerostomia. The total number of medications and the number of anticholinergic medications were significantly higher in patients with allergy (P < 0.001), anemia (P = 0.004), gastrointestinal diseases (P < 0.001), musculoskeletal diseases (P < 0.001), dermatological disorders (P = 0.002), neurological diseases (P < 0.001), and psychiatric diseases (P < 0.001). Significantly more anticholinergic medications were correlated with known xerostomia risk factors, including diabetes (P = 0.006), smoking (P = 0.044), and sleep apnea (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Descriptive analysis of caries status and medication utilization in the study cohort (n = 236).

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | 2.25 | 3.61 | 0 | 21 |

| M | 4.18 | 7.01 | 0 | 28 |

| F | 5.29 | 5.05 | 0 | 20 |

| DMFT (D + M + F) | 11.67 | 8.77 | 0 | 28 |

| Total number of teeth | 24.66 | 7.85 | 0 | 28 |

| Total number of medications | 9.40 | 6.34 | 0 | 38 |

| Total number of anticholinergic medications | 4.27 | 3.16 | 0 | 18 |

| ADS | 2.94 | 2.75 | 0 | 13 |

D, Decayed; M, Missing; F, Filled; DMFT, Decayed, Missing, Filled teeth index; ADS, Anticholinergic Drug Scale.

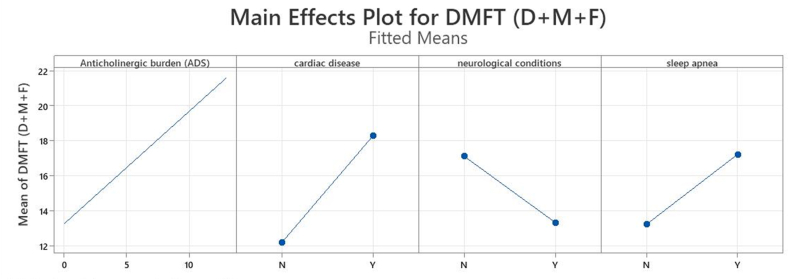

Multiple linear regression was used to predict DMFT based on the anticholinergic burden (ADS), cardiac conditions, neurological conditions, and sleep apnea (Fig. 1); the overall regression was statistically significant (R2 = 10.89%, F (4) = 6.51, P < 0.001). We found that anticholinergic burden (estimated in ADS), cardiac conditions, neurological conditions, and sleep apnea were significant predictors of DMFT scores (Table 4). Age, gender, race, smoking, other medical conditions (allergy, anemia, cancer, developmental disorders, diabetes, ophthalmologic, gastrointestinal, endocrine, infectious, musculoskeletal, psychiatric/behavioral conditions, respiratory conditions, urinary condition, skin conditions), total number of medications, and total number of anticholinergic medications did not explain a statistically significant amount of variance in the DMFT.

Figure 1.

Effect plot of variables influencing the DMFT. Abbreviations: DMFT; Decayed, Missing, and Filled teeth index, D; Decayed, M; Missing, F; Filled teeth, ADS; Anticholinergic Drug Scale, Y; yes, N; no.

Table 4.

Correlation and significance of variables predicting the caries status in medication-induced xerostomia (n = 236).

| Source | df | seq.ss | contribution | adj.ss | adj.ms | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 4 | 1754.0 | 10.89% | 1754.0 | 438.51 | 6.51 | 0.000 |

| Anticholinergic burden (ADS) | 1 | 616.9 | 3.83% | 615.4 | 615.37 | 9.13 | 0.003 |

| Cardiac disease | 1 | 289.9 | 1.80% | 381.6 | 381.56 | 5.66 | 0.018 |

| Neurological conditions | 1 | 491.0 | 3.05% | 550.2 | 550.22 | 8.16 | 0.005 |

| Sleep apnea | 1 | 356.2 | 2.21% | 356.2 | 356.18 | 5.28 | 0.022 |

| Error | 213 | 14356.4 | 89.11% | 14356.4 | 67.40 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 42 | 2580.8 | 16.02% | 2580.8 | 61.45 | 0.89 | 0.660 |

| Pure Error | 171 | 11775.6 | 73.09% | 11775.6 | 68.86 | ||

| Total | 217 | 16110.4 | 100.00% |

df, degrees of freedom; seq.ss, sums of squares; adj.s, adjusted sums of squares; adj.ms, adjusted mean squared errors; ADS, Anticholinergic Drug Scale.

Discussion

Our study highlights significant variables influencing the DMFT score of adult patients with xerostomia: anticholinergic burden (ADS), neurological disorder, cardiac conditions, and sleep apnea. We described a similarly increased caries experience in the middle-aged population in our complimentary study14 with xerostomia being the common factor. We found a higher number of missing teeth and DMFT scores in younger adults with xerostomia compared to non-affected individuals.15 We confirmed a previously published observation that anticholinergic burden correlates to higher DMFT scores. Our results are comparable with those reported by Tiisanoja et al.11 in a cross-sectional study conducted in northern Finland. They concluded that anticholinergic burden is associated with poor oral hygiene status in middle-aged adults. They speculated that changes in cognitive functions in geriatric patients contribute to decreased oral health quality, which could affect caries status.10 Our sample, however, consisted of a much younger adult cohort with frequently occurring neurological, psychiatric, and behavioral conditions, which could negatively impact oral health. Limitations in maintaining good oral hygiene in mental disorders and psychiatric diseases such as depression and anxiety were associated with higher DMFT scores.16

The effect of xerostomia on missing teeth in the younger population has not been thoroughly studied. Edentulism most frequently results from dental caries and periodontal disease. In our study, we refer to partial edentulism as the indicator of missing teeth. A previous study measuring the factors associated with missing teeth reported that tooth decay was the leading cause of tooth loss in the younger population.17 A number of these patients stated xerostomia as one of their oral symptoms. However, Sawair et al. showed that as xerostomia symptoms increased, the number of missing teeth increased.18 Data from Kongstad et al. similarly support our findings by stating that patients with dry mouths had a significantly higher mean DMFT score.19 Other papers on the aged population examined this relationship, concluding that patients with less than 20 teeth experienced xerostomia.20 Available literature explained the increased caries rate and posterior tooth loss by the reduced saliva flow.18

Older adults are more likely to experience adverse effects of anticholinergic drugs due to age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. However, children and younger adults can also experience adverse effects of anticholinergic medications, as studied by Lipovec et al.21 in a rare example of data available on anticholinergic effects on younger ages. They conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study using the Slovenian population-based data in three age groups (children (≤18 years), adults (19–64 years), and older adults (≥65 years). They found that the frequency of anticholinergic exposure was highest among older adults (43.2%), followed by middle-aged and younger adults (25.8%). The two most frequently prescribed medication groups with the highest anticholinergic burden were antipsychotics and medications for urinary diseases (42.8% and 40.2% of the study population, respectively). Data from our patient cohort confirmed this finding, as the highest anticholinergic exposure rates were recorded with neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Anticholinergic drugs are often used to treat cardiac diseases due to their action in increasing the heart rate and adjusting the heart rhythm to treat heart failure.22 Patients in our study were often taking medications for cardiac and vascular diseases associated with high DMFT. Earlier studies found a correlation between sleep apnea, a xerostomia risk factor, and our findings confirmed those results. Apessos et al.23 published that poor sleep quality is a common symptom (P < 0.001) in subjects with morning hyposalivation, as well as in subjects with self-reported symptoms of xerostomia in young men between 18 and 30 years old.

Only six of our patients received treatment for xerostomia, although preventive protocols are inevitable in treating dry mouth syndrome and alleviating patient symptoms. Symptomatic approaches include hydration, avoiding crunchy hard foods, and using sugar-free chewing gums.24,25 Xerostomia can be controlled or treated through several methods, including salivary substitutes, salivary stimulants, and reviewing and modifying any xerostomia-causing medications.14 Frequent dental care visits are advised due to the patient's high risk of developing dental caries. Early identification and treatment of xerostomia may prevent devastating dental conditions and help to improve the patient's life.26 Although the evidence available is limited to reducing the anticholinergic burden of patients with severe oral health side effects, a treatment alternative includes decreasing the dosage or potentially replacing the medications with less xerogenic drugs. Studies have shown that xerostomia became more manageable through medication dose reduction and replacement.27,28

Limitations of the study may affect generalizing the results. Due to the retrospective design, our variables did not include hyposalivation, as the original data did not include saliva flow rate measurements to assess hyposalivation clinically. Self-reported xerostomia represents subjective bias, which reduces validity. The study was completed in only one dental setting, at the Eastman Institute for Oral Health General Dentistry Clinic, without a control group. The selection of ADS was based on previous dental investigations, but it should be added that considerable variation exists among anticholinergic risk scales in grading and specific drug inclusions. Our study, however, can serve as a stepping stone for future studies with a control group to identify patients at higher risk of oral complications.

In conclusion, we found a significant correlation between DMFT and ADS, cardiac diseases, neurological conditions, and sleep apnea. Identifying xerostomia predictors may guide clinicians to make an informed decision to prevent and treat complications associated with AC medication-induced xerostomia. The evidence gathered in this paper can be valuable for establishing prevention strategies and treatment plan changes and assisting the provider in the clinical decision process. It may benefit dental and medical clinicians in the multidisciplinary team caring for non-geriatric adult patients with a high anticholinergic burden.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23DE031021. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Turner M.D. Hyposalivation and xerostomia: etiology, complications, and medical management. Dent Clin. 2016;60:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locker D. Dental status, xerostomia and the oral health-related quality of life of an elderly institutionalized population. Spec Care Dent. 2003;23:86–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2003.tb01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millsop J.W., Wang E.A., Fazel N. Etiology, evaluation, and management of xerostomia. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenspan D. Xerostomia: diagnosis and management. Oncology. 1996;10:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson W.M., Lawrence H.P., Broadbent J.M., Poulton R. The impact of xerostomia on oral-health-related quality of life among younger adults. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2006;4:86. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schumock G.T., Li E.C., Suda K.J., et al. National trends in prescription drug expenditures and projections for 2014. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71:482–499. doi: 10.2146/ajhp130767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kantor E.D., Rehm C.D., Haas J.S., Chan A.T., Giovannucci E.L. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1818–1831. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin C.B., Hales C.M., Gu Q., Ogden C.L. NCHS Data Brief; 2019. Prescription Drug Use in the united states, 2015-2016; pp. 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfistermeister B., Tumena T., Gassmann K.G., Maas R., Fromm M.F. Anticholinergic burden and cognitive function in a large German cohort of hospitalized geriatric patients. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiisanoja A., Syrjala A.M., Anttonen V., Ylostalo P. Anticholinergic burden, oral hygiene practices, and oral hygiene status-cross-sectional findings from the northern Finland birth cohort 1966. Clin Oral Invest. 2021;25:1829–1837. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03485-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiisanoja A., Syrjala A.H., Kullaa A., Ylostalo P. Anticholinergic burden and dry mouth in middle-aged people. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2020;5:62–70. doi: 10.1177/2380084419844511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassolato S.F., Turnbull R.S. Xerostomia: clinical aspects and treatment. Gerodontology. 2003;20:64–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carnahan R.M., Lund B.C., Perry P.J., Pollock B.G., Culp K.R. The anticholinergic drug scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:1481–1486. doi: 10.1177/0091270006292126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arany S., Kopycka-Kedzierawski D.T., Caprio T.V., Watson G.E. Anticholinergic medication: related dry mouth and effects on the salivary glands. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2021;132:662–670. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2021.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanner T., Kamppi A., Pakkila J., et al. Prevalence and polarization of dental caries among young, healthy adults: cross-sectional epidemiological study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:1436–1442. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2013.767932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopes A.G., Ju X., Jamieson L., Mialhe F.L. Oral health-related quality of life among brazilian adults with mental disorders. Eur J Oral Sci. 2021;129 doi: 10.1111/eos.12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casarin M., Nolasco W.D.S., Colussi P.R.G., et al. Prevalence of tooth loss and associated factors in institutionalized adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2021;26:2635–2642. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232021267.07162021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawair F.A., Ryalat S., Shayyab M., Saku T. The unstimulated salivary flow rate in a jordanian healthy adult population. J Clin Med Res. 2009;1:219–225. doi: 10.4021/jocmr2009.10.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kongstad J., Ekstrand K., Qvist V., et al. Findings from the oral health study of the Danish health examination survey 2007-2008. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:1560–1569. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2013.776701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh C.K., Johnson D.A., Dodds M.W., Sakai S., Rugh J.D., Hatch J.P. Association of salivary flow rates with maximal bite force. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1560–1565. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790080601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cebron Lipovec N., Jazbar J., Kos M. Anticholinergic burden in children, adults and older adults in Slovenia: a nationwide database study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:9337. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65989-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landi F., Dell'Aquila G., Collamati A., et al. Anticholinergic drug use and negative outcomes among the frail elderly population living in a nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:825–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apessos I., Andreadis D., Steiropoulos P., Tortopidis D., Angelis L. Investigation of the relationship between sleep disorders and xerostomia. Clin Oral Invest. 2020;24:1709–1716. doi: 10.1007/s00784-019-03029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villa A., Connell C.L., Abati S. Diagnosis and management of xerostomia and hyposalivation. Therapeut Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:45–51. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S76282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Visvanathan V., Nix P. Managing the patient presenting with xerostomia: a review. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:404–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbe A.G. Medication-induced xerostomia and hyposalivation in the elderly: culprits, complications, and management. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:877–885. doi: 10.1007/s40266-018-0588-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trindade E., Menon D., Topfer L.A., Coloma C. Adverse effects associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J) 1998;159:1245–1252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azodo C.C., Ezeja E.B., Omoaregba J.O., James B.O. Oral health of psychiatric patients: the nurse's perspective. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10:245–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2011.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]