Abstract

Alternative splicing generates functional diversity in isoforms, impacting immune response to infection. Here, we evaluate the causal role of alternative splicing in COVID-19 severity and susceptibility by applying two-sample Mendelian randomization to cis-splicing quantitative trait loci and the results from COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. We identify that alternative splicing in lung, rather than total expression of OAS1, ATP11A, DPP9 and NPNT, is associated with COVID-19 severity. MUC1 and PMF1 splicing is associated with COVID-19 susceptibility. Colocalization analyses support a shared genetic mechanism between COVID-19 severity with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis at the ATP11A and DPP9 loci, and with chronic obstructive lung diseases at the NPNT locus. Last, we show that ATP11A, DPP9, NPNT, and MUC1 are highly expressed in lung alveolar epithelial cells, both in COVID-19 uninfected and infected samples. These findings clarify the importance of alternative splicing in lung for COVID-19 and respiratory diseases, providing isoform-based targets for drug discovery.

Subject terms: Viral infection, RNA splicing, Functional genomics

Alternative splicing of transcripts can influence human traits, such as immune response to infection. Here, the authors use mendelian randomization to reveal a role of alternative splicing in lung on COVID-19 severity and susceptibility, offering potential drug discovery avenues.

Introduction

Despite the successful development of vaccines1,2 and treatments3,4, hospital admission for severe COVID-19 and long-term sequela of COVID-19 remain common5,6. COVID-19 is now a leading cause of death, accounting for more than 6 million deaths worldwide7. Thus, there is an ongoing need to identify mechanistic targets for therapeutic development to reduce the risk of severe COVID-19.

Using human genetics methods, several host factors have been identified to influence COVID-19 severity, including OAS1, type I interferon and chemokine genes8–13. Human genetics can provide new biological insights into disease pathogenesis, and therapeutic targets with evidence from human genetics enjoy an increased probability of drug development success14,15. While prior studies have evaluated causal roles of both RNA expression and circulating proteins in COVID-19 outcomes8,11,12, the causal role of alternative splicing has not been fully investigated.

Alternative splicing is an essential mechanism for generating functional diversity in the isoforms, through which multiple mRNA isoforms are produced from a single gene, often in tissue-specific patterns16. Alternative splicing has been implicated in immune response to infections in humans16, and this might be the case for SARS-CoV-2 infection. The genetic determinants of alternative splicing may be identified using splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTL) studies17, where such studies indicate that splicing is under strong genetic control in humans and often has direct effects on protein isoforms. We have recently identified that a Neanderthal-introgressed isoform of OAS1, which is strongly regulated by an sQTL, protects against COVID-19 severity8,18. Given this evidence, we aimed to determine if alternative splicing could partially explain the variability in COVID-19 outcomes in humans at other genes.

In this study, we undertook two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) and colocalization analyses to determine whether RNA splicing influences COVID-19 outcomes19. We first identified cis-sQTLs in lungs and whole blood, two relevant tissues that influence acute SARS-CoV-2 infection20, from the GTEx Consortium v.817. We then used MR to assess whether these RNA splicing events influence on COVID-19 outcomes using the GWASs from the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative release 710. Next, all findings were assessed for colocalization to determine whether RNA splicing events and COVID-19 outcomes shared a common etiological genetic signal and that the MR results were not biased by linkage disequilibrium (LD). We also compared the effects of alternative RNA splicing to total RNA expression, and evaluated the expression of identified genes in the lung transcriptome. Finally, we evaluated whether such alternative splicing is a shared pathophysiological mechanism with other respiratory diseases.

Results

MR using cis-sQTLs, and colocalization analyses

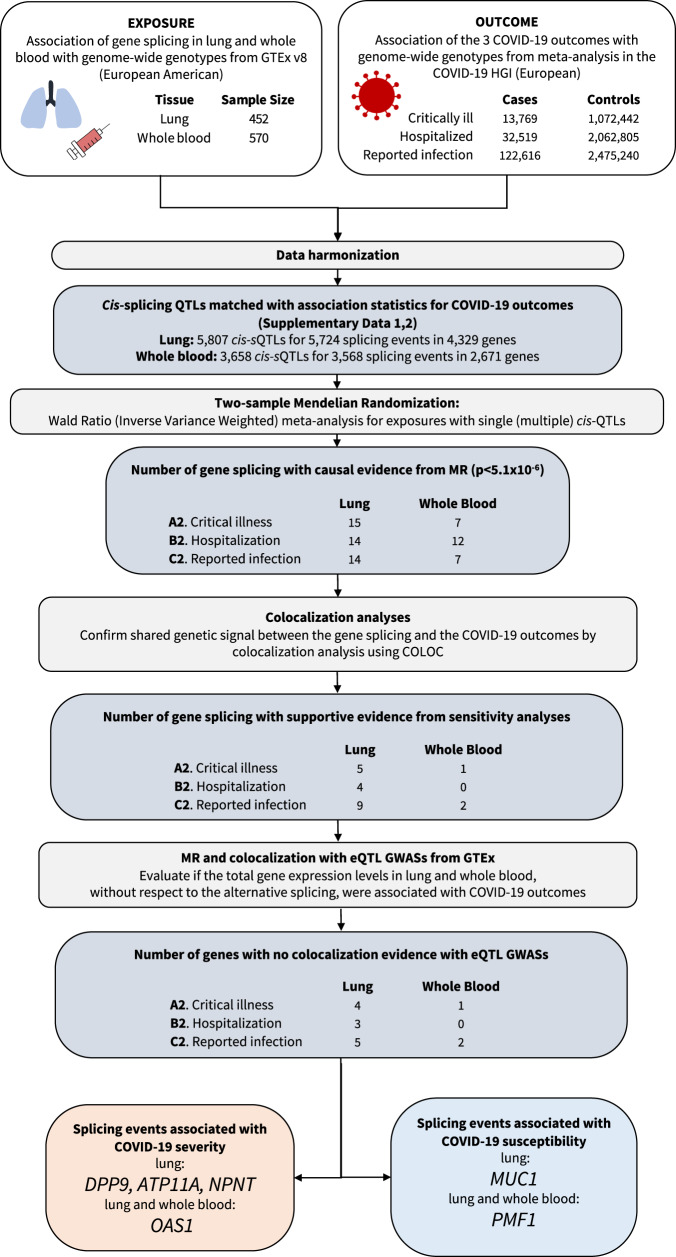

The study design is illustrated in Fig. 1. We obtained sQTLs, which were quantified as normalized intron excision ratios, i.e., the proportion of reads supporting each alternatively excised intron, using LeafCutter21 (with a multiple-testing correction threshold of a false discovery rate of 5% per tissue) in GTEx v.817. We chose to examine only cis-sQTLs, which are more likely to act on local coding genes instead of through horizontally pleiotropic mechanisms, where such genes would have an effect on disease (here, COVID-19 outcomes) independently of the exposure (here, alternative splicing). We focused on two COVID-19-relevant tissues; lungs (N = 452 of European American ancestry) and whole blood (N = 570 of European American ancestry)17. We chose these tissues since pulmonary symptoms are the major determinant of hospital admission and blood immune cells in blood play a major role in host response to SARS-CoV-220.

Fig. 1. Flow Diagram of Study Design.

MR Mendelian randomization.

A total of 5724 transcriptional splicing events for 4329 genes in lung and 3568 transcriptional splicing events for 2671 genes in whole blood contained conditionally independent cis-sQTLs that were also present the GWAS meta-analyses of European ancestry in COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative10 release 7 (https://www.covid19hg.org/results/r7/), which included results from the GenOMICC11 study, but not the 23andMe study. We then undertook two-sample MR analyses using 5807 cis-sQTLs in lungs and 3658 cis-sQTLs in whole blood as genetic instruments for transcriptional splicing against three COVID-19 outcomes: (1) critical illness (defined as individuals experiencing death, mechanical ventilation, non-invasive ventilation, high-flow oxygen, or use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) owing to symptoms associated with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (13,769 cases and 1,072,442 controls); (2) hospitalization owing to symptoms associated with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (32,519 cases and 2,062,805 controls); and (3) reported SARS-CoV-2 infection defined as laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, electronic health record, clinically confirmed COVID-19, or self-reported COVID-19, with or without symptoms of severity (122,616 cases and 2,475,240 controls). Our MR analyses used data from individuals of European ancestry to reduce the risk of bias from population stratification. We could not perform sex-stratified analyses due to the lack of the availability of the sex-stratified GWAS summary statistics.

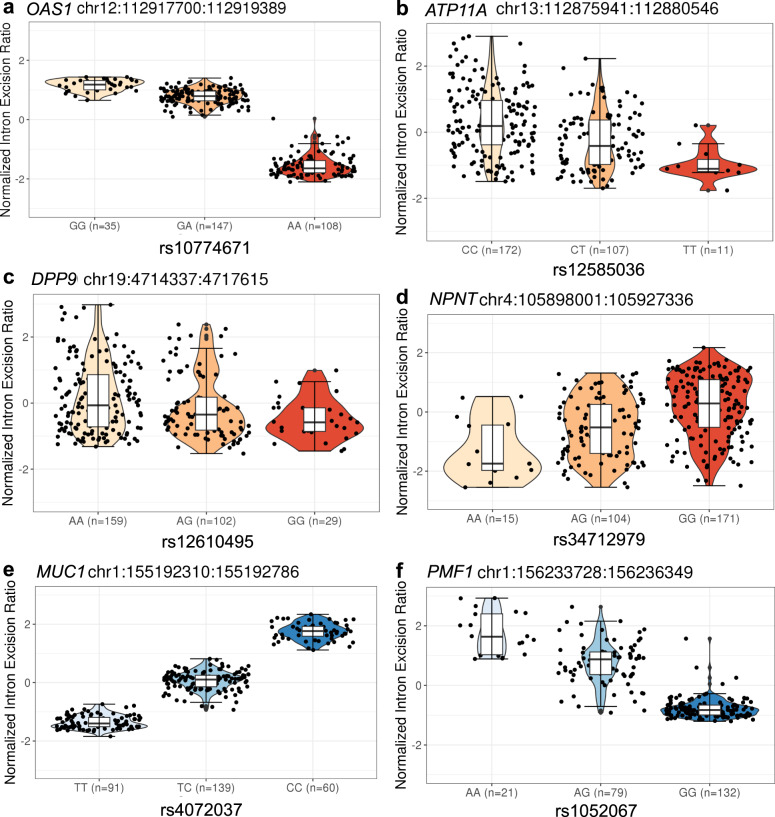

MR analyses identified 43 transcriptional splicing events in lung and 26 transcriptional splicing events in whole blood which influenced COVID-19 outcomes (p < 1.8 × 10−6, a Bonferroni-corrected p-value threshold which accounted for the number of tests performed [N = 27,230] with Type I error rate of 0.05, Methods, Supplementary Data 1, 2). We first replicated the association of COVID-19 outcomes with OAS1 splicing, using an updated version of COVID-19 HGI release 7, which provides a 10-fold increase in case sample size. The OAS1 sQTL, rs10774671:A > G, which increases the excision of the intron junction at chr12:112,917,700-112,919,389 [GRCh38] by 1.7 SD per one copy in lung (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 1A) and by 1.8 SD per one copy in whole blood, respectively, was associated with protection against all three adverse COVID-19 outcomes. The higher excision of the intron junction at chr12:112,917,700-112,919,389 corresponds to an increased level of the p46 isoform22, a prenylated form of OAS1 with higher anti-viral activity than the p42 isoform8,18,23 (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 1,2). While rs10774671 is in LD with two coding variants, rs2660 (r2 = 0.97) and rs1859330 (r2 = 0.87), it is more likely that rs10774671 is the causal variant for the splicing effect, given that rs10774671 is a well-known splice-acceptor variant which has been functionally validated22.

Fig. 2. The violin plots of normalized intron excision ratio stratified by sQTL genotypes.

a OAS1, b ATP11A, c DPP9 and d NPNT show the sQTL genotypes in dark orange that are associated with COVID-19 severity. e MUC1 and f PMF1 show the sQTL genotypes in dark blue that are associated with SARS-CoV-2 reported infection. Normalized intron excision ratios were obtained from GTEx sQTL phenotype matrices (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/datasets). The genotypes were obtained from whole exome sequence data. Lower edge of the whisker: the lowest value within 1.5 * IQR of the hinge, lower hinge: 25% quantile, horizontal line contained within the box: median value, upper hinge: 75% quantile, the upper edge of the whisker: the highest value that is within 1.5 * IQR of the hinge.

Fig. 3. MR estimates of the effect of RNA splicing at ATP11A, DPP9, NPNT, OAS1, MUC1, and PMF1 in lung with COVID-19 outcomes.

Forest plot showing odds ratio and 95% confidence interval from two sample Mendelian Randomization analyses (two-sided). All significant results listed in Fig. 3. were estimated by Wald ratio. P values are unadjusted. Unit of exposure: standard deviation of intron excision ratios as quantified by LeafCutter. Centre: Odds ratio, error bar: 95% confidence interval (CI).

We additionally identified that ATP11A sQTL, rs12585036:T > C, which increases the excision of the intron junction at chr13:112,875,941-112,880,546 by 0.56 SD in lung (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1B), was associated with protection against all three adverse COVID-19 outcomes with odds ratio [OR] per normalized intron excision ratio (the proportion of reads supporting each alternatively excised intron identified by LeafCutter21) of 0.78 (95%CI: 0.73–0.83, p = 2.3 × 10−16) for critical illness, OR of 0.84 (95%CI: 0.81–0.88, p = 9.4 × 10−17) for hospitalization, and OR of 0.96 (0.94–0.98, p = 9.3 × 10−6) for reported infection (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 1). ATP11A has a single protein-coding transcript (ENST00000415301) that excises the targeted intron (chr13:112,875,941-112,880,546, Supplementary Fig. 1B).

We also found novel associations of DPP9 sQTL, rs12610495:G > A, which increases the excision of the intron junction at chr19:4,714,337-4,717,615 by 0.26 SD in lung (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 1C), with protection against all three adverse COVID-19 outcomes (OR: 0.39, 0.35–0.44, p = 3.1 × 10−51 for critical illness, OR: 0.56, 0.52–0.61, p = 4.2 × 10−41 for hospitalization, and OR: 0.82, 0.79–0.86, p = 1.8 × 10−22 for reported infection, Fig. 3). DPP9 has a single protein-coding transcript (ENST00000599248) that excises the targeted intron (chr19:4,714,337-4,717,615, Supplementary Fig. 1C).

NPNT sQTL, rs34712979:A > G, which increases the excision of the intron junction at chr4:105,898,001-105,927,336 by 0.64 SD in lung (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 1D), was associated with increased risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes (critical illness and hospitalization) but with weak evidence of increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR: 1.19, 1.13–1.25, p = 1.2 × 10−10 for critical illness, OR: 1.11, 1.07–1.15, p = 2.2 × 10−8 for hospitalization, and OR: 1.02, 1.00–1.03, p = 4.9 × 10−2 for reported infection, Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 1). The NPNT sQTL, rs34712979-A allele, creates a NAGNAG splice acceptor site, which results in additional in-frame AGT codon, coding for serine, at the 5’ splice site of exon 224. The rs34712979-A allele also serves as a protein-QTL that associates with decreased circulating levels of plasma NPNT25–27, which could reflect the aptamer binding effect impacted by the alternative splicing.

Alternative splicing in the two genes in the gene cluster located in chr1 q21.3-q22, namely MUC1, and THBS3 in lung were also associated with reported SARS-CoV-2 infection, but not with COVID-19 severity phenotypes (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 1). Given that the MUC1 and THBS3 sQTL variants are in high LD with each other (rs4072037:C > T and rs2066981:A > G; r2 = 0.98 in European population of 1000 G), it was challenging to distinguish which of the two genes were more likely to be causal. Nevertheless, the MUC1 sQTL variant, rs4072037:C > T, is a recognized splice variant which influences the 3’ splice site selection of exon 2, which leads to transcripts that have an alternative 27 bp intron retention event at the start of exon 228. We demonstrated the rs4072037:T > C, which increases the excision of the intron junction at chr1:155,192,310–155,192,786 by 1.53 SD in lung (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 1E), was associated with increased risk of reported SARS-CoV-2 infection. Given the evidence of the splicing event of MUC128, it is perhaps more likely that MUC1 splicing influences SARS-CoV-2 infection.

PMF1 sQTL, rs1052067:G > A, which increases the excision of the intron junction at chr1:156,233,728–156,236,349 by 1.4 SD in lung (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 1F) and by 1.5 SD in whole blood, was associated with reduced risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR: 0.98, 0.98–0.99, p = 8.1 × 10−7, both in lung, Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 1, and whole blood, Supplementary Data 2). rs1052067:G > A is a missense variant which replaces methionine with isoleucine at amino acid position 137 of the MANE transcript, ENST00000368277. This variant creates another transcript, ENST00000368279, with an alternative 61 bp intron retention event at the start of exon 4 (Supplementary Fig. 1F).

All above associations of alternative splicing, except for MUC1 and PMF1, were more pronounced as the severity of the COVID-19 outcome increased (Fig. 3). We also applied MR for another hospitalization phenotype compared within COVID-19 cases (“hospitalization vs non-hospitalization amongst individuals with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection”, which corresponds to B1 phenotype in COVID-19 HGI10). Here we used the data from all ancestries, as we did not have access to ancestry specific GWAS summaries for this phenotype. We confirmed the alternative splicing associations with ATP11A and DPP9 (ATP11A: OR 0.88, 0.81–0.94, p = 4.6 × 10−4, and DPP9: OR 0.78, 0.66–0.93, p = 4.9 × 10−3) but not with NPNT, and OAS1 (Supplementary Data 3).

Colocalization analyses

To test whether confounding due to linkage disequilibrium may have influenced the MR estimates, we tested the probability that RNA splicing and the COVID-19 outcomes shared a single causal signal using colocalization analyses, as implemented in coloc29.

Amongst the MR-prioritized alternative splicing (Supplementary Data 1, 2), we selected the transcriptional splicing with high (>0.8) posterior probability29 that the COVID-19 outcome shares a single causal signal with the alternative splicing event (referred to as hypothesis 4 in coloc29, Supplementary Fig. 2). These colocalization analyses supported transcriptional splicing’s role in nine genes (ABO, ATP11A, DPP9, GBAP1, MUC1, NPNT, OAS1, PMF1, and THBS3) in lung and two genes (OAS1 and PMF1) in whole blood that influenced at least one COVID-19 outcome (Supplementary Data 4, 5).

The posterior probability that alternative splicing of ATP11A in lung and COVID-19 outcomes shared a single causal signal in the 1 Mb locus around the cis-sQTL was 1.00 for critical illness, 1.00 for hospitalization due to COVID-19, and 0.98 for reported infection (Supplementary Fig. 2A, Supplementary Data 4). Alternative splicing of DPP9 also had high posterior probabilities of a shared single causal signal for critical illness (0.96), hospitalization (0.96), and reported infection (0.95) (Supplementary Fig. 2B, Supplementary Data 4). Alternative splicing of NPNT had a high posterior probability for critical illness (1.00), and hospitalization (1.00), but had a low posterior probability for reported infection (0.02) (Supplementary Fig. 2C, Supplementary Data 4). Lastly, alternative splicing of MUC1 and PMF1 had high posterior probabilities for reported infection (1.00 and 0.95, respectively, Supplementary Fig. 2D, E, Supplementary Data 4).

MR and colocalization with eQTL GWASs from GTEx

We next sought to determine if the genes identified through cis-sQTL studies also influenced COVID-19 outcomes through total gene expression, irrespective of splicing. To do so we used eQTL studies identified through Open Targets Genetics30,31 (https://genetics.opentargets.org/, Supplementary Data 6). We performed MR and colocalization analyses using cis-expression quantitative trait loci (cis-eQTLs) in lung and whole blood from GTEx. In lung, the total expression of ABO and GBAP1 had MR evidence with high colocalization (a posterior probability >0.8) for COVID-19 outcomes (all three COVID-19 outcomes with ABO and reported infection with GBAP1, Supplementary Data 7). In whole blood, the eQTLs of ABO had high colocalization with critical illness and hospitalization (Supplementary Data 8). For those genes, we could not clarify whether the associations with COVID-19 outcomes were driven by either total gene expression or the spliced isoform expression, or both.

Influence of prioritized sQTLs on other diseases

We next searched for the effects of the sQTLs, which influence COVID-19 outcomes, on other diseases. To do so, we used the Open Targets Genetics30,31 to identify diseases and disease-associated traits with its GWAS lead variants in LD (r2 > 0.80) with COVID-19 associated sQTLs (Table 1). We found that the DPP9 sQTL (rs12610495:G > A) was associated with decreased risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)32 where the same allele confers the protection against COVID-19 severity. Interestingly, we found the opposite direction of effects between IPF and COVID-19 in the sQTL for ATP11A, where the rs12585036-C allele was associated with increasing risk of IPF and decreased risk for COVID-19 severity. The NPNT sQTL had similar trend for the rs34712979-A allele, which was protective for COVID-19 severity, but was associated with increased risk of COPD24 (i.e. lower FEV1/FVC ratio, a spirometry measurement used to diagnose COPD)33,34 and with increased risk of asthma35. The OAS1 sQTL (rs10774671:A > G, protective allele for COVID-19 severity) was associated with a decreased risk of systemic lupus erythematosus (in the East Asian population)36 and with an increased risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia37. The MUC1 sQTL (rs4072037:T > C, risk allele for SARS-CoV-2 infection) was associated with decreased risk of gastric cancer38, gout39, and inflammatory bowel disease40. The PMF1 sQTL (rs1052067:G > A, protective allele for SARS-CoV-2 infection) was associated with increased risk of testicular germ cell tumor41, decreased risk intracerebral haemorrhage and ischemic stroke42 and decreased levels of serum creatinine43.

Table 1.

Colocalization analyses of COVID-19 outcomes and other diseases at the identified sQTL loci

| sQTL locus (rsID) | chr | pos (b38) | EA | NEA | Intron junction | COVID-19 outcome | PP* between sQTL and COVID-19 | Other outcome | PP* between COVID-19 and other outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP11A (rs12585036) | 13 | 112881427 | C | T | chr13:112,875,941-112,880,546 ↑ (lung, WBC) | critical illness ↓ | 1.00 | idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis ↑ [PMID: 31710517] | 1.00 |

| DPP9 (rs12610495) | 19 | 4717660 | A | G | chr19:4,714,337-4,717,615 ↑ (lung) | critical illness ↓ | 0.96 | idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis ↓ [PMID: 31710517] | 1.00 |

| NPNT (rs34712979) | 4 | 105897896 | G | A | chr4:105,898,001-105,927,336 ↑ (lung) | critical illness ↑ | 1.00 | FEV1/FVC ratio↑ [PMID: 30804560] | 1.00 |

| COPD↓ [PMID: 30804561] | - | ||||||||

| Asthma↓ [PMID: 31959851] | - | ||||||||

| OAS1 (rs10774671) | 12 | 112919388 | G | A | chr12:112,917,700-112,919,389 ↑ (lung) | critical illness ↓ | 0.99 | systemic lupus erythematosus ↓ [PMID: 33272962] | - |

| chronic lymphocytic leukemia↑ [PMID: 28165464] | - | ||||||||

| MUC1 (rs4072037) | 1 | 155192276 | C | T | chr1:155,192,310:155,192,786 ↑ (lung) | reported infection ↑ | 0.97 | inflammatory bowel disease ↓ [PMID: 28067908] | 1.00 |

| gastric cancer ↓ [PMID: 26098866] | - | ||||||||

| gout ↑ [PMID: 33959723] | - | ||||||||

| Urate level ↑ [PMID:33462484] | 1.00 | ||||||||

| PMF1 (rs1052067) | 1 | 156236330 | A | G | chr1:156,233,728:156,236,349↑ (lung, whole blood) | reported infection ↓ | 0.95 | Testicular germ cell tumor ↑ [PMID: 28604728] | - |

| Serum creatinine levels ↓ [PMID: 34594039] | - | ||||||||

| Intracerebral hemorrhage ↓ [PMID: 24656865] | - | ||||||||

| Ischemic stroke ↓ [PMID: 29531354] | 0.30 |

aPP: a posterior probability that there is an association for two outcomes in GWASs, which is driven by the same causal variant. PP was only estimated when there is an available GWAS summary statistics of European ancestry. All significant results listed in Table 1 were estimated by Wald ratio.

EA effect allele, NEA non-effect allele.

We performed colocalization analyses in each sQTL locus between COVID-19 outcomes and the other associated diseases/phenotypes if the effects were supported in the European ancestry population and there was GWAS summary data available. IPF32 and critical illness due to COVID-19 were highly colocalized at the ATP11A and DPP9 sQTL loci with a posterior probability of 1.00. The FEV1/FVC ratio33 also colocalized with critical illness due to COVID-19 with a posterior probability of 1.00 at the NPNT locus. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)40 and urate level (which is a cause of gout) also colocalized with reported SARS-CoV-2 infections at the MUC1 locus (both posterior probabilities are 1.00). We found no GWAS summary statistics available for the other diseases (Table 1). These lines of evidence suggest that IPF and COVID-19 severity, COPD/asthma and COVID-19 severity, and IBD/gout and COVID-19 susceptibility may share causal genetic determinants at these loci, respectively. The full results and the data used are summarized in Table 1.

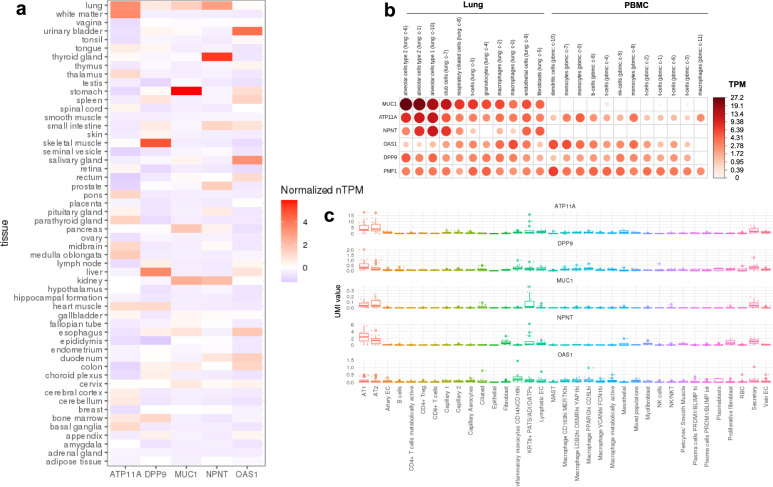

The tissue and cell-type specific expression of the associated genes

To assess the relevant tissues and cell-types for the genes whose transcriptional splicing was identified by MR, we evaluated the transcriptional expression in lung and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) of healthy controls, as well as in lung of COVID-19 patients. In the consensus transcript expression levels from Human Protein Atlas (HPA)44 and GTEx, the expression of ATP11A, and NPNT were highly enriched in normal lung tissue (Fig. 4a). At a single-cell resolution, in normal lung, MUC1, ATP11A and NPNT were specifically enriched in alveolar type 1 and 2 epithelial cells (Fig. 4b), which are known to play important roles in regeneration of alveolar epithelium following lung injury45. In 23 lung COVID-19 autopsy donor tissue samples from GSE17166820, the expression of ATP11A, DPP9, MUC1, and NPNT were also enriched in alveolar type 1 and 2 epithelial cells (Fig. 4c). Taken together, these expression evidence suggests that the transcriptional splicing—COVID-19 outcome relationships for ATP11A, DPP9, MUC1, and NPNT were likely to be relevant in lung tissue and these signals may be especially important in alveolar epithelial cells.

Fig. 4. Gene expression in lung and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

a The consensus transcript expression levels summarized per gene in 54 tissues in Human Protein Atlas (HPA), which was calculated as the maximum transcripts per million value (TPM) value for each gene in all sub-tissues categories of each tissue, based on transcriptomics data from HPA and GTEx. The consensus transcript expression level for PMF1 was not available in HPA. b RNA single cell type tissue cluster data (transcript expression levels summarized per gene and cluster) of lung (GSE130148) and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) (GSE112845) were visualized using log10(protein-transcripts per million [pTPM]) values. Each c-X annotation is taken from the clustering results performed in HPA. c Single-cell RNA expression profile of 23 lung COVID-19 autopsy donor tissue samples from GSE17166820. The RNA expression of PMF1 was not detected in this dataset. The mean value of RNA expression of the cells annotated in the same subcategory was represented as a dot per each sample. The cell type annotation was manually performed in the original publication. AT1 alveolar type 1 epithelial cells, AT2 alveolar type 2 epithelial cells, EC endothelial cells, KRT8+ PATS/ADI/DATPs KRT8+ pre-alveolar type 1 transitional cell state, MAST mast cells, XXhi XX (gene expression) high cells, RBC red blood cells. Lower edge of the whisker: the lowest value within 1.5 * IQR of the hinge, lower hinge: 25% quantile, horizontal line contained within the box: median value, upper hinge: 75% quantile, the upper edge of the whisker: the highest value that is within 1.5 * IQR of the hinge.

Discussion

Despite current vaccines and therapeutic options, hospitalization for COVID-19 remains high in many countries. Thus, there remains a need for additional therapies, which in turn, requires target identification and validation46. In this large-scale two-sample MR study of alternative splicing assessed for their effect upon three COVID-19 outcomes in up to 122,616 COVID-19 cases and 2,475,240 population controls, we provide evidence that alternative splicing of OAS1, ATP11A, DPP9 and NPNT in lung influences COVID-19 severity, and alternative splicing of MUC1 and PMF1 in lung influences COVID-19 susceptibility. Moreover, these genetic mechanisms are likely shared with other diseases, such as ATP11A and DPP9 with IPF.

There are multiple sources of biological evidence which might support the relevance of ATP11A in COVID-19. ATP11A is a member of the P4-ATPase family, which codes for a phospholipid flippase at the plasma membrane and translocates phosphatidylserine from the outer to the inner leaflet of plasma membranes. Cells that undergo apoptosis, necroptosis or pyroptosis expose phosphatidylserine on their surface through P4-ATPase, of which ATP11A is cleaved by a caspase during apoptosis47. While less functionally defined, given the high expression of ATP11A in the alveolar type 2 epithelial cells, the ATP11A sQTL (rs12585036) may impact the cell death of alveolar type 2 epithelial cells, the resident stem cell population in lung48, and may impair regeneration of alveolar epithelium following lung injury. However, these hypotheses require further study.

Our MR analysis showed that the increased excision of intron junction chr19:4,814,337–4,717,615 in the DPP9 gene, which is preferentially spliced in ENST00000599248, was associated with reduced risk of COVID-19 severity. Although it is not fully understood how the DPP9 sQTL (rs12610495) regulates alternative splicing of DPP9, the rs12610495-G allele creates a GGGG motif (from GGAG sequence), which may have an effect on alternative splicing of some genes49. DPP9 interacts with NLRP1 and represses inflammasome activation50 and pyroptosis, which are now recognized as important mechanisms interrupting the viral replication cycle and preventing viral amplification of SARS-CoV-251. Moreover, targeting inflammasome-mediated hyperinflammation in COVID-19 patients may also prevent chronic phase of COVID-19 pathophysiology in vivo51.

Our MR analyses found that MUC1 splicing was associated with susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 infection. MUC1 is a mucin, which is also called KL−6 in humans, and the serum level of KL-6 is used as a biomarker for some interstitial lung diseases52. rs4072037-T allele was associated with decreased levels of the intron junction of chr1:155,192,310–155,192,786, which corresponds to transcripts with an alternative 27 bp intron retention event at the start of exon 228. MUC1 exon 2 harbors a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) that contains 20 to 125 repeats of a 60 bp coding sequence that determines the length of a heavily glycosylated extracellular domain53. Although rs4072037 may or may not control the alternative splicing of VNTR region38, in addition to the alternative 27 bp intron retention28, the VNTR length of MUC1 is associated with several renal phenotypes in a recent study in UK Biobank54. The MUC1 sQTL was also associated with IBD with high colocalization evidence. IBD is a disease with disrupted intestinal epithelial barrier and is suggested to be associated with gut dysbiosis55. Taken together, it is plausible that alternative splicing of MUC1 in lung alveolar cells has an impact on SARS-CoV-2 infection.

This study has limitations. First, the excised intron junction was quantified in an annotation-free manner using LeafCutter21, without respect to the level of transcripts nor isoforms. It is thus important for future work to map those disease-relevant alternative splicing events to the corresponding isoform or protein product, by means of emerging technologies such as long-read sequencing56 and high-throughput protein quantification57. We anticipate our findings, and others, will motivate the ongoing effort to do so. Second, we used MR to test the effect of alternative splicing measured in a non-infected state since the effect of the cis-sQTLs upon alternative splicing was estimated in individuals who had not been exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Given the dynamic gene regulation of splicing during infection58, alternative splicing could be changed once a person experiences SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thus, the MR results presented in this paper should be interpreted as an estimation of the effect of alternative splicing during uninfected state. Future studies may help to clarify if the same cis-sQTLs regulate alternative splicing during infection. Third, it was not our goal to identify all alternative splicing that affects COVID-19 outcomes, but rather to provide strong evidence for a small set of genes with strong MR and colocalization evidence. Thus, we acknowledge a high false-negative rate of our study design. Fourth, as we used the data from individuals of European descent, we could not confirm that our findings could be transferrable to individuals of other populations. Fifth, while our findings demonstrate the effects of alternative splicing in lung and whole blood since these are relevant to COVID-19 severity, we recognize that these splicing events may not be unique to these tissues and thus the estimated effects of splicing may represent the action of these same alternative transcripts in other tissues. Lastly, a recent paper59 reported that the shared genetic signal between IPF and COVID-19 outcomes at the DPP9 and ATP11A loci are likely driven by the difference of total expression in whole blood, which was supported by colocalization using eQTLGen60 dataset. However, eQTLGen consists of multi-ancestry cohorts and could be affected by the bias due to LD. Moreover, we demonstrated that both DPP9 and ATP11A expression were enriched in alveolar cells in lung, compared to whole blood. These findings support the hypothesis that alternative splicing of DPP9 and ATP11A in lung is important both for IPF and COVID-19 severity.

Our results provide rationale to explore the targeting of alternative splicing in lung as a treatment for respiratory diseases61,62 by means of therapeutic modalities such as splice-switching oligonucleotides (SSOs). SSOs are a type of antisense oligonucleotides which are generally 15–30 nucleotides in length and are designed as complementary to specific regions of mRNA with increased stability against endogenous nucleases due to chemical modifications63. SSOs can prevent splicing promoting factors from binding to the target pre-mRNA, which can modulate alternative splicing64. Some SSOs have been already approved by FDA, such as eteplirsen for Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, which induces the skipping of exon 51 of the DMD gene, and nusinersen for spinal muscle atrophy, which induces the expression of exon 7 of the SMN2 gene63. Although delivery to target tissues after systemic administration has been a key challenge in the development of SSO drugs63,65, lung might be advantageous tissue to target since it is possible to deliver drugs directly to lung through inhalation.

In conclusion, we have used genetic determinants of alternative splicing and COVID-19 outcomes obtained from large-scale studies and found compelling evidence that splicing events in OAS1, ATP11A, DPP9, NPNT, MUC1, and PMF1 have causal effects on COVID-19 severity and susceptibility. Interestingly, the available evidence suggests shared genetic mechanisms for COVID-19 severity with IPF at the ATP11A and DPP9 loci, and with chronic obstructive lung diseases at the NPNT locus. Taken together, our study highlights the importance of alternative splicing both in COVID-19 and other diseases, which could be further investigated for drug discovery programs.

Methods

Splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTL) GWASs

We obtained all conditionally independent sQTLs in lung and whole blood that act in cis (in a +/−1 Mb window around the transcription start site of each gene) with normalized intron excision ratios from LeafCutter21 (5% FDR per tissue) in GTEx v817. Conditionally independent sQTLs were mapped using stepwise regression in GTEx consortium17. Intron excision ratios are the proportion of reads supporting each alternatively excised intron identified by LeafCutter21. We selected lung and whole blood since they are the two major tissues relevant to the pathophysiology of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection20. We obtained the effect estimate of each conditionally independent cis-sQTL from the data mapped in European-American subjects (N = 452 for lung and N = 570 for whole blood) in GTEx v.817. If the cis-sQTL was missing in the summary data mapped in European-ancestry subjects, we removed those cis-sQTLs in the analyses.

For the key sQTLs, we created violin plots to visualize the normalized intron excision ratios stratified by sQTL genotypes. Normalized intron excision ratio was obtained from GTEx publicly available sQTL phenotype matrices (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/datasets). The individual-level genotypes were obtained from imputed genotype data in GTEx for which we achieved access through dbGaP. The samples with available data of both normalized intron excision ratio and sQTL genotypes were used to create violin plots (N = 232 ~ 290). We also drew sashimi plots, diagrams which combine the information of read coverage along a gene with curves connecting splice sites supported by RNA-seq data. We obtained individual RNA-seq mapped bam files for 514 lung samples in GTEx v.8 through dbGaP. We used ggsashimi (https://github.com/guigolab/ggsashimi) R package v1.1.5 to visualize splice junction usage per sQTL genotype. The mean number of reads supporting the splicing events per each genotype group are shown in the sashimi plots, which were adjusted for the average expression (counts per million: CPM) of the region including the cluster to which the index intronic junction belongs and the exons at both ends. CPM was calculated by (the mapped read counts of the region / the total read counts) × 10−6 (Supplementary Data 9).

COVID-19 GWASs

To assess the association of cis-sQTLs with COVID-19 outcomes, we used COVID-19 GWAS meta-analyses results of European-ancestry subjects from the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative (HGI) release 710 (https://www.covid19hg.org/results/r7/). The outcomes tested were critical illness, hospitalization, and reported SARS-CoV-2 infection (named A2, B2, and C2, respectively by the COVID-19 HGI).

Critically ill COVID-19 cases were defined as those individuals who were hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and who required respiratory support (invasive ventilation, continuous positive airway pressure, Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure, or continuous external negative pressure, high-flow nasal or face-mask oxygen) or who died due to the disease. Simple supplementary oxygen (e.g. 2 l/min via nasal cannula) did not qualify for case status. Hospitalized COVID-19 cases were defined as individuals hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (using the same microbiology methods as for the critically ill phenotype), where hospitalization was due to COVID-19 related symptoms. Reported SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined as laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection or electronic health record, ICD coding or clinically confirmed COVID-19, or self-reported COVID-19 (for example, by questionnaire), with or without symptoms of any severity. Controls were defined in the same way across all three outcomes above as everybody that is not a case—for example, population controls.

In a sensitivity analysis, we also used another hospitalization phenotype (named B1 in the COVID-19 HGI), where cases were hospitalized COVID-19 cases and controls were defined as non-hospitalized individuals with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Two-sample Mendelian randomization

We used two-sample mendelian randomization (MR) analyses using “TwoSampleMR v0.5.6” R package66 to screen and test the potential role of alternative splicing in lung and whole blood to influence COVID-19 outcomes. In two-sample MR, the effect of genetic variants on the exposure and outcome are taken from separate GWASs. Two-sample MR often improves statistical power compared to single-sample MR, where sample sizes are smaller. MR is less affected by confounding and reverse causality than observational epidemiology studies since genotypes are essentially randomly assigned at conception and not influenced by the disease outcome. The MR framework is based on three main assumptions: First, the genetic variants are robustly associated with the exposure (i.e. a lack of weak instrument bias). We validated that all cis-sQTLs had a F-statistic >10, corresponding to T-statistics >3.16, which indicate a low risk of weak instrument bias in MR analyses67. Second, the genetic variants are not associated with any confounding factors for the relationship between the exposure and the outcome. Third, the genetic variants have no effect on the outcome that is independent of the exposure (i.e. a lack of horizontal pleiotropy), which is the most challenging assumption to assess. Nevertheless, in order to reduce the risk of horizontal pleiotropy, we selected cis-sQTLs as instrumental variables, as cis-genetic variants that reside close to the genes are more likely to have an effect on the outcomes by directly influencing the alternative splicing, thus reducing potential horizontal pleiotropy. Palindromic cis-sQTLs with minor allele frequencies (MAF) > 0.42 were removed prior to MR to prevent allele-mismatches. We also removed genetic variants within MHC region to reduce the risk of bias from LD. For alternative splicing with a single (sentinel) cis-sQTL, we used Wald ratio to estimate the effect of each splicing event on each of the three COVID-19 outcomes. For any alternative splicing event with multiple conditionally independent cis-sQTLs, an inverse variance weighted (IVW) method was used to meta-analyze their combined effects. After harmonizing the cis-sQTLs with COVID-19 GWASs, a total of 5724 splicing events in 4329 genes (5807 matched cis-sQTLs) in lung and a total of 3658 splicing events in 2671 genes (3658 matched cis-sQTLs) in whole blood were used for the MR analyses across the three COVID-19 outcomes. We applied the Bonferroni corrected p-value (5.1 × 10−6) to adjust for the number of tests performed (N = 27,230, 5546 tests between alternative splicing in lung and critical illness, 5570 tests between alternative splicing in lung and hospitalization, 5686 tests between alternative splicing in lung and reported SARS-CoV-2 infection, 3453 tests between alternative splicing in whole blood and critical illness, 3451 tests between alternative splicing in whole blood and hospitalization, 3524 tests between alternative splicing in lung and reported SARS-CoV-2 infection).

Colocalization analyses

Next, we evaluated whether the splicing events and COVID-19 outcomes shared a common etiological genetic signal and that the MR results were not biased by linkage disequilibrium (LD) using colocalization analyses. Specifically, for each of these MR significant splicing events, a stringent Bayesian analysis was implemented in “coloc v5.1.0.1” R package with default settings to analyze all variants in 1MB genomic locus centered on the cis-sQTL. Colocalizations with posterior probability for high colocalization (PP > 0.8), that is, that there is an association for both splicing events and COVID-19 outcomes, and they are driven by the same causal variant were considered to colocalize, which means that the exposure and the outcome shared a single causal variant.

Mendelian randomization and colocalization with eQTL GWASs from GTEx

To understand if the total gene expression levels in lung and whole blood were associated with COVID-19 outcomes, without respect to the splicing or isoforms, we similarly performed MR and colocalization analyses using expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) in lung and whole blood from GTEx v.817 (lung: N = 452 of European ancestry, and whole blood: N = 570 of European ancestry) by restricting the regions within 1 Mb of each QTL. The genetic instruments were conditionally independent eQTLs for the prioritized sQTL genes in lung and/or whole blood, all of which had strong support for colocalization between sQTLs and COVID-19 outcomes.

Influence of identified sQTLs on other diseases

We assessed the effects of the sQTLs which influence COVID-19 outcomes on other diseases. Pleiotropic search was performed using Open Targets Genetics30,31 (https://genetics.opentargets.org) and identified any GWAS lead variants that are in LD (r2 > 0.80) with those sQTLs. Colocalization analyses were performed using “coloc v5.1.0.1” R package when there were available GWAS summary statistics of European ancestry.

The tissue and cell-type specific expression of the associated genes

To assess the relevant tissues and cell-types for the genes whose transcriptional splicing were identified by MR, we evaluated the transcriptional expression in lung and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) of healthy controls, as well as in lung of COVID-19 patients. We first downloaded consensus transcript expression levels summarized per gene in 54 tissues in Human Protein Atlas (HPA)44, which was calculated as the maximum transcripts per million value (TPM) value for each gene in all sub-tissues categories of each tissue, based on transcriptomics data from HPA and GTEx. We also downloaded the single-cell type transcriptomic analyses, where we used all cell types in lung (originally GSE13014868) and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) (originally GSE11284569). We visualized RNA single cell type tissue cluster data (transcript expression levels summarized per gene and cluster), using log10(protein-transcripts per million [pTPM]) values with “corrplot v0.92” R package. Lastly, we obtained single-cell RNA expression profile of 23 lung COVID-19 autopsy donor tissue samples from GSE17166820. We calculated “pseudo-bulk” RNA expression per each cell type by taking the mean value of RNA expression of the cells annotated in the same subcategory.

Inclusion and ethics statement

All collaborators of this study have fulfilled the criteria for authorship required by Nature Portfolio journals have been included as authors, as their participation was essential for the design and implementation of the study. This research was not severely restricted or prohibited in the setting of the researchers. GTEx protected access data was applied through dbGaP upon ethical approval from Jewish General Hospital (ethics number 2024-3794). This research does not result in stigmatization, incrimination, discrimination or personal risk to participants.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Luis Barreiro for his expertise and assistance in writing the manuscript. The Richards research group is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR: 365825; 409511, 100558, 169303), the McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity (MI4), the Lady Davis Institute of the Jewish General Hospital, the Jewish General Hospital Foundation, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, the NIH Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Genome Québec, the Public Health Agency of Canada, McGill University, Cancer Research UK [grant umber C18281/A29019] and the Fonds de Recherche Québec Santé (FRQS). J.B.R. is supported by a FRQS Mérite Clinical Research Scholarship. Support from Calcul Québec and Compute Canada is acknowledged. TwinsUK is funded by the Welcome Trust, Medical Research Council, European Union, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded BioResource, Clinical Research Facility and Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London. These funding agencies had no role in the design, implementation or interpretation of this study. T.N. is supported by a research fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists (22KJ1190, 22J30004) and this work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research(B) (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number: 23H02917). J.W. is supported by the CIHR (476575). B.G.G. is supported by Wellcome Trust grant 221680/Z/20/Z.

Author contributions

Conception and design: T.N. and J.B.R. Formal analysis: T.N. and J.W. Data curation: T.N., J.W., and Y.F. Interpretation of data: T.N., J.W., Y.F., R.J.A., B.G.G., and J.B.R. Funding acquisition: T.N., J.B.R. Investigation: T.N., J.W., and Y.F. Methodology: T.N., Y.F., and J.B.R. Project administration: T.N., D.A., J.B.R. Resources: T.N., J.B.R. Supervision: T.N., Y.F., and J.B.R. Validation: T.N., J.W., Y.F., and J.B.R. Visualization: T.N. and J.W. Writing—original draft: T.N. Writing—review and editing: T.N., J.W., Y.F., R.J.A., B.G.G., D.A., S.Z., and J.B.R. All authors were involved in further drafts of the manuscript and revised it critically for content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. The corresponding authors attest that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks James Peters and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Summary statistics for eQTLs and sQTLs from GTEx v817 are available in the GTEx website (gtexportal.org/home/datasets). The GTEx protected access data are available under restricted access, access can be obtained through dbGaP (application ID: 32756). Summary statistics for the COVID-19 outcomes release 7 are available in the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative website70 (https://www.covid19hg.org/results/r7/). The consensus transcript expression levels and RNA single cell type tissue cluster data are available at the Human Protein Atlas website (www.proteinatlas.org/about/download). RNA single cell type tissue cluster data for lung and PBMC was originally obtained from GSE13014868 and GSE11284569, respectively. The processed single-cell RNA expression profile of 23 lung COVID-19 autopsy donor tissue sample are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession code GSE17166820.

Code availability

All code for data management and analysis is archived online at github.com/richardslab/COVID19-sQTLMR for review and reuse71. We used ggsashimi (https://github.com/guigolab/ggsashimi) R package v1.1.5 to visualize splice junction usage per sQTL genotype. We used TwoSampleMR v0.5.6 R package66 to run two-sample mendelian randomization (MR) analyses. Colocalization analyses were performed using coloc v5.1.0.1 R package. We visualized RNA single cell type tissue cluster data using corrplot v0.92 R package.

Competing interests

T.N. has received speaking fee from Boehringer Ingelheim for the talks unrelated to this research. J.B.R.’s institution has received investigator-initiated grant funding from Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline and Biogen for projects unrelated to this research. J.B.R. is the CEO of 5 Prime Sciences (www.5primesciences.com), which provides research services for biotech, pharma and venture capital companies for projects unrelated to this research. Y.F. is an employee of 5 Prime Sciences. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Tomoko Nakanishi, Julian Willett.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Tomoko Nakanishi, J. Brent Richards.

Contributor Information

Tomoko Nakanishi, Email: tomoko.nakanishi@mail.mcgill.ca.

J. Brent Richards, Email: brent.richards@mcgill.ca.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-41912-4.

References

- 1.Haas EJ, et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397:1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polack FP, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 — Preliminary Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 693–704 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Hammond J, et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386:1397–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang L, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:747–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Lancet. Understanding long COVID: a modern medical challenge. Lancet398, 725 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int.

- 8.Zhou, S. et al. A Neanderthal OAS1 isoform protects individuals of European ancestry against COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. Nat. Med. 27, 659–667 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.The Severe Covid-19 GWAS Group. Genomewide Association Study of Severe Covid-19 with Respiratory Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1522–1534 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. Mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature600, 472–477 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Pairo-Castineira, E. et al. Genetic mechanisms of critical illness in Covid-19. Nature 591, 92–98 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Kousathanas, A. et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals host factors underlying critical Covid-19. Nature607, 97–103 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Nakanishi, T. et al. Age-dependent impact of the major common genetic risk factor for COVID-19 on severity and mortality. J. Clin. Invest. 131, e152386 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Nelson MR, et al. The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:856–860. doi: 10.1038/ng.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook D, et al. Lessons learned from the fate of AstraZeneca’s drug pipeline: a five-dimensional framework. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:419–431. doi: 10.1038/nrd4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kornblihtt AR, et al. Alternative splicing: a pivotal step between eukaryotic transcription and translation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:153–165. doi: 10.1038/nrm3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.THE GTEX CONSORTIUM. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science369, 1318–1330 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Huffman, J. E. et al. Multi-ancestry fine mapping implicates OAS1 splicing in risk of severe COVID-19. Nat. Genet. 54, 125–127 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, a global initiative to elucidate the role of host genetic factors in susceptibility and severity of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 28, 715–718 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Delorey TM, et al. COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Nature. 2021;595:107–113. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, Y. I. et al. Annotation-free quantification of RNA splicing using LeafCutter. Nat. Genet. 50, 151–158 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bonnevie-Nielsen V, et al. Variation in antiviral 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (2′5′AS) enzyme activity is controlled by a single-nucleotide polymorphism at a splice-acceptor site in the OAS1 gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;76:623–633. doi: 10.1086/429391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wickenhagen, A. et al. A prenylated dsRNA sensor protects against severe COVID-19. Science374, eabj3624 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Saferali, A. et al. Characterization of a COPD-associated NPNT functional splicing genetic variant in human lung tissue via long-read sequencing. Preprint at MedRxiv10.1101/2020.10.20.20203927 (2020).

- 25.Ferkingstad, E. et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat. Genet. 53, 1712–1721 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Pietzner, M. et al. Mapping the proteo-genomic convergence of human diseases. Science374, 1541 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Yoshiji, S. et al. Proteome-wide Mendelian randomization implicates nephronectin as an actionable mediator of the effect of obesity on COVID-19 severity. Nat. Metab. 5, 248–264 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Ng W, Loh AXW, Teixeira AS, Pereira SP, Swallow DM. Genetic regulation of MUC1 alternative splicing in human tissues. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;99:978–985. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hormozdiari F, et al. Colocalization of GWAS and eQTL signals detects target genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;99:1245–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mountjoy, E. et al. Open targets genetics: An open approach to systematically prioritize causal variants and genes at all published human GWAS trait-associated loci. Nat. Genet. 53, 1527–1533 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Ghoussaini M, et al. Open targets genetics: systematic identification of trait-associated genes using large-scale genetics and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D1311–D1320. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen RJ, et al. Genome-wide association study of susceptibility to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020;201:564–574. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201905-1017OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shrine N, et al. New genetic signals for lung function highlight pathways and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associations across multiple ancestries. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:481–493. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakornsakolpat P, et al. Genetic landscape of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease identifies heterogeneous cell-type and phenotype associations. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:494–505. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olafsdottir TA, et al. Eighty-eight variants highlight the role of T cell regulation and airway remodeling in asthma pathogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:393. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14144-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yin X, et al. Meta-analysis of 208370 East Asians identifies 113 susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021;80:632–640. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Law PJ, et al. Genome-wide association analysis implicates dysregulation of immunity genes in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14175. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helgason H, et al. Loss-of-function variants in ATM confer risk of gastric cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:906–910. doi: 10.1038/ng.3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandoval-Plata G, Morgan K, Abhishek A. Variants in urate transporters, ADH1B, GCKR and MEPE genes associate with transition from asymptomatic hyperuricaemia to gout: results of the first gout versus asymptomatic hyperuricaemia GWAS in Caucasians using data from the UK Biobank. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021;80:1220–1226. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Lange, K. M. et al. Genome-wide association study implicates immune activation of multiple integrin genes in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Genet. 49, 256–261 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Litchfield K, et al. Identification of 19 new risk loci and potential regulatory mechanisms influencing susceptibility to testicular germ cell tumor. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1133–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng.3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malik R, et al. Multiancestry genome-wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:524–537. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0058-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakaue S, et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 2021;53:1415–1424. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00931-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karlsson M, et al. A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:eabh2169. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abh2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castranova V, Rabovsky J, Tucker JH, Miles PR. The alveolar type II epithelial cell: a multifunctional pneumocyte. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1988;93:472–483. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(88)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katzourakis A. COVID-19: endemic doesn’t mean harmless. Nature. 2022;601:485. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Segawa K, et al. A sublethal ATP11A mutation associated with neurological deterioration causes aberrant phosphatidylcholine flipping in plasma membranes. J. Clin. Invest. 2021;131:148005. doi: 10.1172/JCI148005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barkauskas CE, et al. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:3025–3036. doi: 10.1172/JCI68782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Královic̆ová J, Vor̆echovský I. Position-dependent repression and promotion of DQB1 intron 3 splicing by GGGG motifs. J. Immunol. 2006;176:2381–2388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hollingsworth LR, et al. DPP9 sequesters the C terminus of NLRP1 to repress inflammasome activation. Nature. 2021;592:778–783. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03350-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sefik E, et al. Inflammasome activation in infected macrophages drives COVID-19 pathology. Nature. 2022;606:585–593. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04802-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ishikawa N, Hattori N, Yokoyama A, Kohno N. Utility of KL-6/MUC1 in the clinical management of interstitial lung diseases. Respir. Investig. 2012;50:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fowler JC, Teixeira AS, Vinall LE, Swallow DM. Hypervariability of the membrane-associated mucin and cancer marker MUC1. Hum. Genet. 2003;113:473–479. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mukamel RE, et al. Protein-coding repeat polymorphisms strongly shape diverse human phenotypes. Science. 2021;373:1499–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.abg8289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee M, Chang EB. Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and the microbiome—searching the crime scene for clues. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:524–537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Logsdon GA, Vollger MR, Eichler EE. Long-read human genome sequencing and its applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020;21:597–614. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-0236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kraemer, S. et al. From SOMAmer-based biomarker discovery to diagnostic and clinical applications: a SOMAmer-based, streamlined multiplex proteomic assay. PLoS ONE6, e26332 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Rotival M, Quach H, Quintana-Murci L. Defining the genetic and evolutionary architecture of alternative splicing in response to infection. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1671. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09689-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allen RJ, et al. Genetic overlap between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2022;60:2103132. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03132-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Võsa U, et al. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2021;53:1300–1310. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00913-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schneider-Poetsch T, Chhipi-Shrestha JK, Yoshida M. Splicing modulators: on the way from nature to clinic. J. Antibiot. 2021;74:603–616. doi: 10.1038/s41429-021-00450-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Le K, Prabhakar BS, Hong W, Li L. Alternative splicing as a biomarker and potential target for drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015;36:1212–1218. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levin AA. Treating disease at the RNA level with oligonucleotides. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:57–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1705346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kole R, Krainer AR, Altman S. RNA therapeutics: beyond RNA interference and antisense oligonucleotides. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012;11:125–140. doi: 10.1038/nrd3625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davis ME, et al. Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature. 2010;464:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hemani G, et al. The MR-base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife. 2018;7:e34408. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burgess S, Thompson SG, CRP CHD Genetics Collaboration. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011;40:755–764. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vieira Braga FA, et al. A cellular census of human lungs identifies novel cell states in health and in asthma. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1153–1163. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0468-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen J, et al. PBMC fixation and processing for chromium single-cell RNA sequencing. J. Transl. Med. 2018;16:198. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1578-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. A second update on mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature.621, E7–E26 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Nakanishi, T. & Willett, J. Alternative splicing in lung influences COVID-19 severity and respiratory diseases. richardslab/COVID19-sQTLMRhttps://zenodo.org/badge/latestdoi/539917089 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Summary statistics for eQTLs and sQTLs from GTEx v817 are available in the GTEx website (gtexportal.org/home/datasets). The GTEx protected access data are available under restricted access, access can be obtained through dbGaP (application ID: 32756). Summary statistics for the COVID-19 outcomes release 7 are available in the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative website70 (https://www.covid19hg.org/results/r7/). The consensus transcript expression levels and RNA single cell type tissue cluster data are available at the Human Protein Atlas website (www.proteinatlas.org/about/download). RNA single cell type tissue cluster data for lung and PBMC was originally obtained from GSE13014868 and GSE11284569, respectively. The processed single-cell RNA expression profile of 23 lung COVID-19 autopsy donor tissue sample are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession code GSE17166820.

All code for data management and analysis is archived online at github.com/richardslab/COVID19-sQTLMR for review and reuse71. We used ggsashimi (https://github.com/guigolab/ggsashimi) R package v1.1.5 to visualize splice junction usage per sQTL genotype. We used TwoSampleMR v0.5.6 R package66 to run two-sample mendelian randomization (MR) analyses. Colocalization analyses were performed using coloc v5.1.0.1 R package. We visualized RNA single cell type tissue cluster data using corrplot v0.92 R package.