Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin condition and prior genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 71 associated loci. In the current study we conducted the largest AD GWAS to date (discovery N = 1,086,394, replication N = 3,604,027), combining previously reported cohorts with additional available data. We identified 81 loci (29 novel) in the European-only analysis (which all replicated in a separate European analysis) and 10 additional loci in the multi-ancestry analysis (3 novel). Eight variants from the multi-ancestry analysis replicated in at least one of the populations tested (European, Latino or African), while two may be specific to individuals of Japanese ancestry. AD loci showed enrichment for DNAse I hypersensitivity and eQTL associations in blood. At each locus we prioritised candidate genes by integrating multi-omic data. The implicated genes are predominantly in immune pathways of relevance to atopic inflammation and some offer drug repurposing opportunities.

Subject terms: Genome-wide association studies, Skin diseases

The genetic basis of atopic dermatitis is not fully understood. Here, the authors find 91 genetic loci associated with atopic dermatitis in a GWAS of >1million individuals, which highlight the importance of systemic immune regulation.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD, or eczema) is a common allergic disease, characterised by (often relapsing) skin inflammation affecting up to 20% of children and 10% of adults1. Several genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been performed in recent years, identifying genetic risk loci for AD.

Our most recent GWAS meta-analysis within the EAGLE (EArly Genetics and Lifecourse Epidemiology) consortium, published in 2015 uncovered 31 AD risk loci2. Since then, additional GWAS have been published which have confirmed known risk loci3,4 and discovered novel loci5. Five novel loci were identified in a European meta-analysis6, and variants in 3 genes were implicated in a rare variant study in addition to 5 novel loci7. Four novel loci were reported in a Japanese population (and another 4 identified in a trans-ethnic meta-analysis in the same study)8, giving a total of 71 previously reported AD loci2–14 (defined as 1 Mb regions) of which 57 have been reported in European ancestry individuals, 18 have been reported in individuals of non-European ancestry and 29 in individuals across multiple ancestry groups (Supplementary Data 1).

The availability of several new large population-based studies has provided an opportunity to perform an updated GWAS of AD, aiming to incorporate data from all cohorts that have contributed to previously published AD GWAS, as well as data from additional cohorts, to present the most comprehensive GWAS of AD to date, including comparison of effects between European, East Asian, Latino and African ancestral groups. In this work we identify novel loci and use multi-omic data to further characterise these associations, prioritising candidate causal genes at individual loci and investigating the genetic architecture of AD in relation to tissues of importance and shared genetic risk with other traits.

Results

European GWAS

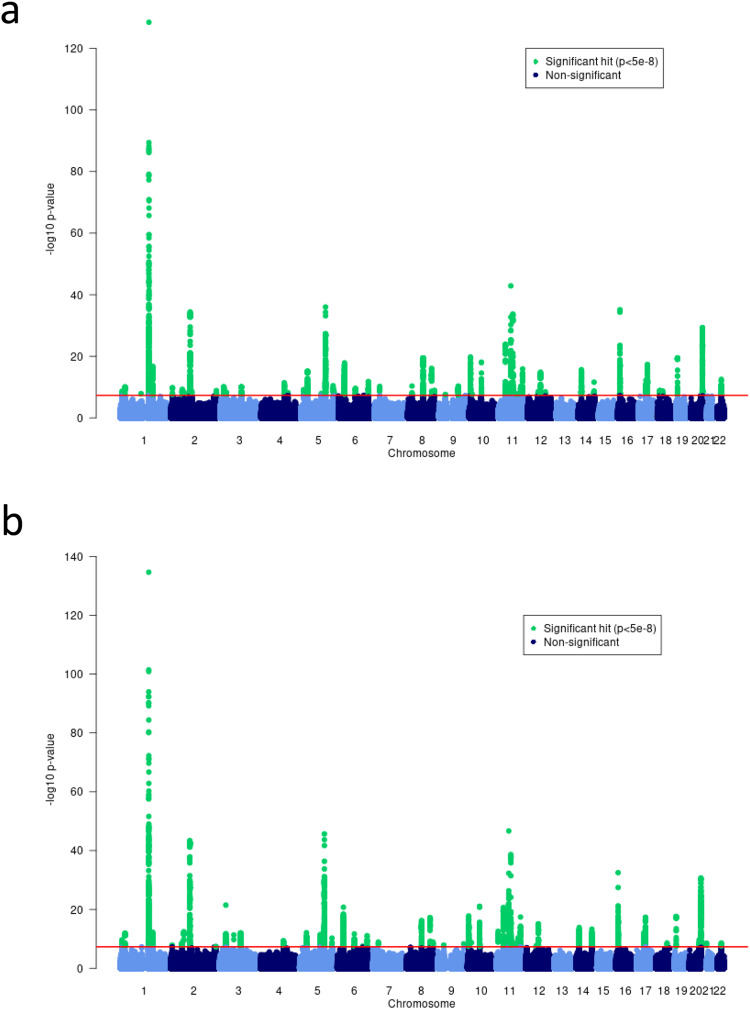

The discovery European meta-analysis (N = 864,982; 60,653 AD cases and 804,329 controls from 40 cohorts, summarised in Supplementary Data 2) identified 81 genome-wide significant independent associated loci (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). 52 were at previously reported loci (Table 1) and 29 (Table 2) were novel (according to criteria detailed in the methods). All 81 were associated in the European 23andMe replication analysis (Bonferroni corrected P < 0.05/81 = 6 × 10−4), N = 2,904,664, Table 1). There was little evidence of genomic inflation in the individual studies (lambda <1.05) and overall (1.06). Conditional analysis determined 44 additional secondary independent associations (P < 1 × 10−5) across 21 loci (Supplementary Data 3).

Fig. 1. Manhattan plots of atopic dermatitis GWAS.

(a) the European-only fixed effects meta-analysis (n = 864,982 individuals) and (b) the multi-ancestry MR-MEGA meta-analysis (n = 1,086,394 individuals). −log10(P-values) are displayed for all variants in the meta-analysis. Variants that meet the genome-wide significance threshold (5 × 10−8, red line) are shown in green.

Table 1.

Genome-wide significant loci in European-only analysis that have been previously reported

| European discovery | Multi-ancestry discovery | 23andMe European replication (N = 2,904,664) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant | Chr:position | Alleles (EAF) | OR (CI) | P | N (studies) | P | N (studies) | OR (CI) | P | Gene | Pathway/Function |

| rs7542147 | 1:25294618 | C/T (0.49) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | 8.52E−11 | 860840 (38) | 2.4E−09 | 870216 (42) | 1.05 (1.04–1.05) | 4.6E−56 | RUNX3 | Versatile transcription factor, incl. T cell differentiation |

| rs12123821 | 1:152179152 | T/C (0.05) | 1.40 (1.35–1.45) | 4.05E−90 | 850727 (29) | 2.3E−98 | 857207 (31) | 1.27 (1.25–1.29) | 1.4E−228 | FLG | Skin barrier protein |

| rs61816766a | 1:152319572 | C/T (0.03) | 1.66 (1.58–1.74) | 6.44E−89 | 627936 (20) | 1.1E−102 | 634416 (22) | 1.41 (1.39–1.43) | 1.4E−228 | FLG | Skin barrier protein |

| rs72702900 | 1:152771963 | A/T (0.04) | 1.28 (1.24–1.33) | 2.98E−46 | 851612 (29) | 3.0E−49 | 853748 (30) | 1.23 (1.22–1.25) | 4.2E−163 | FLG | Skin barrier protein |

| rs61815704 | 1:152893891 | G/C (0.02) | 1.78 (1.67–1.89) | 3.21E−71 | 530473 (19) | 9.2E−72 | 536953 (21) | 1.36 (1.34–1.39) | 5.5E−212 | S100A9b | TLR4 signalling |

| rs12133641 | 1:154428283 | G/A (0.39) | 1.07 (1.05–1.08) | 1.72E−21 | 857974 (37) | 1.8E−22 | 1079390 (42) | 1.04 (1.04–1.05) | 3.0E−45 | IL6R | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs859723 | 1:172744543 | A/G (0.36) | 0.94 (0.93–0.96) | 3.74E−14 | 522713 (37) | 2.4E−14 | 744125 (42) | 0.96 (0.96–0.97) | 2.2E−39 | TNFSF4b | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs11811788 | 1:173150727 | G/C (0.24) | 1.07 (1.05–1.08) | 1.85E−17 | 859747 (38) | 3.1E−16 | 1081160 (43) | 1.04 (1.04–1.05) | 1.6E−39 | TNFSF4 | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs891058 | 2:8442547 | A/G (0.29) | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) | 1.76E−10 | 862482 (38) | 2.2E−11 | 1083890 (43) | 0.97 (0.97–0.98) | 3.0E−18 | ID2 | Transcriptional regulator of many cellular processes |

| rs112111458 | 2:71100105 | G/A (0.12) | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) | 5.50E−09 | 858567 (37) | 1.4E−11 | 1079980 (42) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | 1.3E−21 | CD207 | Dendritic cell function |

| rs2272128 | 2:103039929 | A/G (0.77) | 0.91 (0.90–0.92) | 8.14E−35 | 862259 (39) | 3.8E−48 | 1083670 (44) | 0.93 (0.93–0.94) | 2.2E−100 | IL18RAP | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs4131280 | 3:18414570 | A/G (0.57) | 0.96 (0.95–0.98) | 1.2E−08 | 864982 (40) | 5.8E−08 | 1086390 (45) | 0.97 (0.97–0.98) | 2.2E−19 | SATB1 | Regulates chromatin structure and gene expression |

| rs13097010 | 3:18673161 | G/A (0.34) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 9.0E−11 | 864982 (40) | 1.5E−08 | 1086390 (45) | 1.02 (1.01–1.02) | 1.4E−07 | SATB1 | Regulates chromatin structure and gene expression |

| rs35570272 | 3:33047662 | T/G (0.40) | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | 5.7E−09 | 864982 (40) | 2.3E−20 | 1086390 (45) | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | 1.6E−26a | GLB1 | Sphingolipid metabolism |

| rs6808249 | 3:112648985 | T/C (0.54) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | 9.05E−11 | 859747 (38) | 3.8E−12 | 1081160 (43) | 0.97 (0.96–0.97) | 4.7E−29 | CD200R1 | Adaptive immune system |

| rs45599938 | 4:123386720 | A/G (0.35) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 4.61E−12 | 859747 (38) | 3.7E−10 | 1081160 (43) | 1.05 (1.05–1.06) | 1.3E−62 | KIAA1109 | Endosomal transport |

| rs10214273 | 5:35883986 | G/T (0.27) | 0.94 (0.93–0.96) | 5.97E−16 | 863209 (39) | 1.8E−14 | 1084620 (44) | 0.93 (0.93–0.94) | 2.9E−99 | IL7R | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs17132590 | 5:110331899 | C/T (0.10) | 1.07 (1.05–1.10) | 1.16E−08 | 525225 (38) | 1.7E−08 | 746637 (43) | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | 1.0E−07 | CAMK4 | Immune response, inflammation & memory consolidation |

| rs4706020 | 5:130674076 | A/G (0.34) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 1.12E−11 | 518425 (35) | 2.7E−11 | 527801 (39) | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | 6.4E−09 | CDC42SE2 | F-actin accumulation at immunological synapse of T cells |

| rs4705908 | 5:131347520 | A/G (0.37) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 6.80E−13 | 520344 (36) | 1.6E−11 | 529720 (40) | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | 8.0E−15 | SLC22A5 | Organic cation transport |

| rs20541 | 5:131995964 | G/A (0.78) | 0.91 (0.89–0.92) | 1.00E−36 | 859747 (38) | 8.4E−51 | 1076820 (42) | 0.92 (0.91–0.92) | 1.2E−129 | SLC22A5 | Organic cation transport |

| rs114503346 | 5:172192350 | T/C (0.04) | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | 3.62E−11 | 855569 (33) | 1.3E−10 | 862049 (35) | 0.94 (0.93–0.95) | 3.2E−17 | ERGIC1 | Transport between endoplasmic reticulum and golgi |

| rs41293876 | 6:31466536 | C/G (0.14) | 0.90 (0.88–0.93) | 7.02E−16 | 645820 (36) | 6.5E−18 | 865966 (40) | 0.95 (0.95–0.96) | 4.3E−32 | TNF | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs12153855 | 6:32074804 | C/T (0.10) | 0.92 (0.90–0.94) | 1.96E−11 | 812536 (37) | 2.8E−10 | 821912 (41) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | 2.3E−18 | ATF6B | Endoplasmic reticulum stress response |

| rs28383330 | 6:32600340 | G/A (0.13) | 0.88 (0.85–0.90) | 1.42E−18 | 625716 (28) | 1.8E−17 | 632956 (31) | 0.94 (0.93–0.95) | 2.4E−51 | AGER | Immunoglobulin surface receptor |

| rs9275218 | 6:32658933 | G/C (0.34) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 5.36E−10 | 505320 (34) | 1.0E−09 | 512560 (37) | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | 1.0E−04 | HLA-DRA | Immune response antigen presentation |

| rs629326 | 6:159496713 | T/G (0.61) | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) | 1.7E−12 | 859747 (38) | 4.5E−12 | 1081160 (43) | 0.95 (0.95–0.96) | 5.4E−61a | TAGAPb | T cell activation |

| rs952558 | 8:81288734 | T/A (0.62) | 0.94 (0.93–0.95) | 3.60E−20 | 862259 (39) | 1.3E−19 | 1083670 (44) | 0.97 (0.96–0.97) | 2.2E−31 | ZBTB10 | Transcriptional regulation |

| rs6996614 | 8:126609868 | A/C (0.53) | 1.07 (1.05–1.08) | 8.48E−17 | 693031 (37) | 1.0E−17 | 914443 (42) | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | 1.5E−19 | TRIB1 | Protein kinase regulation |

| rs12251307 | 10:6123495 | T/C (0.12) | 1.10 (1.08–1.12) | 1.98E−20 | 864982 (40) | 8.4E−19 | 1086390 (45) | 1.10 (1.09–1.11) | 4.7E−107 | IL2RA | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs10796303 | 10:6627700 | C/T (0.66) | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) | 8.69E−10 | 856884 (38) | 8.5E−10 | 1078300 (43) | 0.97 (0.96–0.97) | 5.6E−25 | PRKCQ | T cell activation |

| rs10822037 | 10:64376558 | C/T (0.61) | 1.06 (1.05–1.08) | 8.53E−19 | 864982 (40) | 1.3E−24 | 1086390 (45) | 1.05 (1.04–1.05) | 4.0E−55 | ADO | Taurine biosynthesis |

| rs10836538 | 11:36365253 | T/G (0.34) | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) | 9.18E−11 | 863063 (39) | 1.1E−13 | 1084480 (44) | 0.95 (0.95–0.96) | 6.2E−55 | PRR5L | Protein phosphorylation |

| rs28520436 | 11:36428447 | T/C (0.03) | 1.20 (1.16–1.24) | 1.22E−24 | 855865 (29) | 4.1E−25 | 1074380 (32) | 1.18 (1.16–1.20) | 5.3E−81 | PRR5L | Protein phosphorylation |

| rs10791824 | 11:65559266 | G/A (0.58) | 1.10 (1.08–1.11) | 1.34E−43 | 864982 (40) | 1.2E−51 | 1086390 (45) | 1.07 (1.06–1.07) | 1.2E−105 | MAP3K11 | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs7936323 | 11:76293758 | A/G (0.46) | 1.08 (1.07–1.10) | 2.07E−34 | 864982 (40) | 1.8E−39 | 1086390 (45) | 1.07 (1.07–1.08) | 1.9E−133 | LRRC32 | TGF beta regulation incl. on T cells |

| rs11236813 | 11:76343427 | C/G (0.10) | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | 1.94E−12 | 864646 (39) | 4.8E−12 | 1086060 (44) | 0.95 (0.94–0.96) | 2.6E−26 | LRRC32 | TGF beta regulation incl. on T cells |

| rs10790275 | 11:118745884 | C/G (0.80) | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) | 5.46E−11 | 859747 (38) | 4.8E−09 | 1081160 (43) | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | 1.0E−10 | DDX6b | mRNA degradation |

| rs7127307 | 11:128187383 | C/T (0.49) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 1.29E−16 | 859747 (38) | 1.0E−17 | 1081160 (43) | 0.96 (0.95–0.96) | 6.1E−52 | FLI1 | NF-kappaB signalling |

| rs705699 | 12:56384804 | A/G (0.40) | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | 3.31E−09 | 864982 (40) | 6.7E−08 | 1086390 (45) | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | 8.7E−27 | RPS26 | Peptide chain elongation |

| rs2227491 | 12:68646521 | C/T (0.61) | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | 1.46E−15 | 864982 (40) | 1.9E−15 | 1086390 (45) | 1.05 (1.05–1.06) | 1.2E−71 | IL22 | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs2415269 | 14:35638937 | A/G (0.26) | 0.94 (0.93–0.96) | 2.26E−16 | 862613 (39) | 9.3E−15 | 1084020 (44) | 0.96 (0.96–0.97) | 3.8E−32 | SRP54 | Peptide chain elongation |

| rs4906263 | 14:103249127 | C/G (0.65) | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) | 2.65E−12 | 693031 (37) | 1.5E−10 | 702407 (41) | 1.04 (1.03–1.04) | 2.9E−36 | TRAF3 | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs2041733 | 16:11229589 | C/T (0.54) | 0.92 (0.91–0.93) | 7.85E−36 | 864982 (40) | 5.8E−40 | 1086390 (45) | 0.94 (0.94–0.95) | 4.2E−95 | RMI2 | DNA repair |

| rs1358175 | 17:38757789 | T/C (0.63) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 1.99E−11 | 864982 (40) | 1.4E−14 | 1086390 (45) | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | 1.2E−26 | CCR7 | B and T lymphocyte activation |

| rs17881320 | 17:40485239 | T/G (0.08) | 1.09 (1.07–1.12) | 5.34E−13 | 862032 (38) | 2.0E−11 | 870142 (41) | 1.07 (1.06–1.08) | 9.8E−39 | STAT3b | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

| rs4247364 | 17:43336687 | C/G (0.70) | 0.96 (0.95–0.98) | 4.54E−08 | 862470 (39) | 1.3E−07 | 1083880 (44) | 0.97 (0.97–0.98) | 1.7E−17 | DCAKDb | Coenzyme A biosynthetic process |

| rs56308324 | 17:45819206 | T/A (0.13) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 4.89E−10 | 860694 (38) | 1.1E−08 | 1082110 (43) | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | 2.6E−11 | TBX21b | Th1 differentiation |

| rs28406364 | 17:47454507 | T/C (0.38) | 1.06 (1.05–1.07) | 5.01E−18 | 864982 (40) | 2.3E−18 | 1086390 (45) | 1.04 (1.03–1.04) | 1.5E−34 | GNGT2 | G protein signalling |

| rs2967677 | 19:8789721 | T/C (0.15) | 1.08 (1.07–1.10) | 3.35E−20 | 861624 (38) | 5.8E−23 | 1083040 (43) | 1.06 (1.05–1.07) | 7.5E−49 | CERS4 | Sphingolipid metabolism |

| rs6062486 | 20:62302539 | A/G (0.69) | 1.09 (1.07–1.10) | 5.03E−30 | 782263 (37) | 4.4E−32 | 1003680 (42) | 1.07 (1.07–1.08) | 4.5E−109 | RTEL1 | DNA repair |

| rs4821569 | 22:37316873 | G/A (0.53) | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | 3.14E−13 | 863063 (39) | 1.6E−11 | 1084480 (44) | 1.04 (1.04–1.05) | 5.4E−50 | CSF2RB | Cytokine signalling in immune system |

The lead SNP at each independent locus is displayed, along with the results from the European-only discovery, multi-ancestry discovery and European replication. The top ranked gene from our gene prioritisation is listed, along with a description of the pathway/function of the gene. The evidence implicating each gene is presented in Supplementary Data 11.

Alleles are listed as effect allele/other allele, the effect allele frequency (EAF) in Europeans (average EAF, weighted by the sample size of each cohort).

Association statistics, Odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) and (unadjusted, two-sided) P-values are displayed for the fixed effects European-only meta-analysis and the replication analysis. P-values (unadjusted, two-sided) only are available from the MR-MEGA meta-regression multi-ancestry analysis.

Genome build = GRCh37/hg19.

aImputation batch effect observed in 23andMe data.

bOne of two or three tied genes at these loci are shown.

Table 2.

Novel genome-wide significant loci in European-only analysis

| European Discovery | Multi-ancestry discovery | 23andMe European replication (N = 2,904,664) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant | Chr:position | Alleles (EAF) | OR (CI) | P | N (studies) | P | N (studies) | OR (CI) | P | Gene | Pathway |

| rs301804b | 1:8476441 | G/C (0.30) | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | 2.3E−09 | 698266 (39) | 8.5E−09 | 707642 (43) | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | 5.5E−16 | RERE | Apoptosis |

| rs61776548 | 1:12091024 | A/G (0.47) | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | 4.2E−08 | 787144 (39) | 1.4E−07 | 1008560 (44) | 1.02 (1.01–1.02) | 5.6E−09 | TNFRSF1B | Cytokine signalling in immune response |

| rs12565349 | 1:110371629 | G/C (0.15) | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | 1.3E−08 | 862259 (39) | 1.9E−07 | 1083670 (44) | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | 5.8E−15 | CSF1 | Cytokine signalling in immune response |

| rs187080438 | 1:150374354 | T/C (0.03) | 1.17 (1.11–1.23) | 3.7E−10 | 758729 (20) | 2.2E−12 | 765209 (22) | 1.14 (1.12–1.16) | 2.0E−41 | CTSS | Antigen presentation in immune response |

| rs146527530b | 1:151059196 | G/T (0.02) | 1.27 (1.20–1.35) | 5.5E−15 | 744128 (13) | 7.4E−19 | 744128 (13) | 1.25 (1.22–1.28) | 1.5E−88 | CTSS | Antigen presentation in immune response |

| rs115161931b | 1:151063299 | T/C (0.04) | 1.18 (1.13–1.23) | 1.0E−13 | 472565 (26) | 3.2E−12 | 479045 (28) | 1.09 (1.08–1.11) | 2.0E−32 | CTSS | Antigen presentation in immune response |

| rs71625130b | 1:151625094 | A/G (0.04) | 1.23 (1.18–1.28) | 2.4E−27 | 770827 (25) | 7.2E−30 | 772963 (26) | 1.17 (1.16–1.19) | 1.7E−89 | RORCc | Cytokine signalling in immune response |

| rs149199808b | 1:151626396 | T/C (0.03) | 1.32 (1.26-1.38) | 4.4E−30 | 756174 (19) | 8.7E−34 | 762654 (21) | 1.24 (1.22–1.26) | 3.1E−134 | RORC | Cytokine signalling in immune response |

| rs821429b | 1:153275443 | A/G (0.96) | 0.86 (0.84–0.89) | 5.9E−18 | 852224 (30) | 8.2E−16 | 858704 (32) | 0.91 (0.89–0.92) | 2.7E−38 | S100A7 | Differentiation regulation incl. in the innate immune system |

| rs12138773 | 1:153843489 | A/C (0.03) | 1.11 (1.07–1.16) | 2.3E−08 | 851937 (28) | 1.3E−09 | 858417 (30) | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) | 3.5E−16 | S100A12c | Regulation of inflammatory processes and immune response |

| rs67766926a,b | 2:61163581 | G/C (0.23) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 5.7E−10 | 863063 (39) | 2.9E−11 | 1084480 (44) | 1.05 (1.04–1.05) | 1.2E−41 | AHSA2P | Protein folding |

| rs112385344 | 2:112275538 | T/C (0.12) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 2.8E−09 | 852837 (34) | 3.9E−08 | 862213 (38) | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | 1.5E−18 | MERTKc | Inhibits TLR-mediated innate immune response |

| rs62193132 | 2:242788256 | T/C (0.46) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | 1.5E−09 | 832761 (26) | 7.1E−08 | 1052040 (30) | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | 1.5E−19 | NEU4 | Sphingolipid metabolism |

| rs10833b | 4:142654547 | C/T (0.65) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | 7.3E−09 | 859747 (38) | 6.0E−08 | 1081160 (43) | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | 3.4E−15 | IL15 | Cytokine signalling in immune response |

| rs148161264b | 5:14604521 | G/C (0.04) | 1.10 (1.07–1.14) | 7.4E−10 | 850619 (29) | 2.0E−08 | 857099 (31) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 1.6E−08 | OTULINL | Endoplasmic reticulum component |

| rs7701967 | 5:130059750 | A/G (0.31) | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) | 3.4E−09 | 520344 (36) | 3.6E−09 | 529720 (40) | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 1.1E−06 | LYRM7 | Mitochondrial respiratory chain complex assembly |

| rs4532376b | 5:176774403 | A/G (0.30) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | 3.5E−09 | 859747 (38) | 2.3E−09 | 1081160 (43) | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | 1.4E−18 | RGS14 | G-alpha signalling |

| rs72925996b | 6:90930513 | C/T (0.33) | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) | 3.2E−10 | 862259 (39) | 5.4E−09 | 1083670 (44) | 0.96 (0.95–0.96) | 2.2E−44 | BACH2 | NF-kappaB proinflammatory signalling |

| rs989437 | 7:28830498 | G/A (0.61) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | 6.1E−11 | 864982 (40) | 1.0E−09 | 1086390 (45) | 0.97 (0.96–0.97) | 6.9E−31 | CREB5c | AMPK & ATK signalling |

| rs34215892 | 8:21767240 | A/G (0.03) | 0.87 (0.83–0.90) | 4.7E−11 | 436369 (24) | 2.0E−09 | 442849 (26) | 0.89 (0.88–0.91) | 1.0E−36 | DOK2 | Immune response IL-23 signalling |

| rs118162691 | 8:21767809 | A/C (0.05) | 0.92 (0.89–0.94) | 7.8E−09 | 856229 (30) | 1.8E−07 | 862709 (32) | 0.90 (0.88–0.91) | 1.1E−44 | DOK2 | Immune response IL-23 signalling |

| rs7843258 | 8:141601542 | C/T (0.82) | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | 1.5E−09 | 859747 (38) | 3.6E−10 | 1081160 (43) | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | 7.0E−25 | AGO2 | siRNA-mediated gene silencing |

| rs7857407 | 9:33430707 | A/T (0.40) | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | 2.5E−08 | 864982 (40) | 9.0E−09 | 1086390 (45) | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | 5.1E−18 | AQP3 | Aquaporin-mediated transport |

| rs10988863 | 9:102331281 | C/A (0.21) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 5.1E−11 | 862259 (39) | 3.0E−09 | 1083670 (44) | 0.97 (0.97–0.98) | 1.3E−13 | NR4A3 | Transcriptional activator |

| rs17368814 | 11:102748695 | G/A (0.13) | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | 1.4E−08 | 858117 (37) | 6.8E−07 | 1078260 (41) | 0.95 (0.95–0.96) | 1.2E−27 | MMP12 | Extracellular matrix organisation |

| rs11216206 | 11:116843425 | G/C (0.07) | 1.10 (1.07–1.14) | 5.5E−10 | 557183 (35) | 2.9E−10 | 778595 (40) | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | 8.5E−15 | SIK3 | LKB1 signalling |

| rs5005507b | 12:94611908 | C/G (0.74) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 3.6E−09 | 859747 (38) | 9.6E−08 | 1081160 (43) | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | 2.7E−18 | PLXNC1 | Semaphorin interactions incl. in immune response |

| rs7147439 | 14:105523663 | A/G (0.73) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | 4.7E−08 | 781909 (37) | 6.6E−07 | 1003320 (42) | 0.97 (0.96–0.97) | 4.8E−24 | GPR132 | GPCR signalling |

| rs2542147 | 18:12775851 | T/G (0.84) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 1.5E−09 | 862470 (39) | 7.5E−08 | 1083880 (44) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | 2.6E−26 | PTPN2 | Cytokine signalling in immune response |

The lead SNP at each independent locus is displayed, along with the results from the European-only discovery, multi-ancestry discovery and European replication. The top-ranked gene from our gene prioritisation is listed, along with a description of the pathway/function of the gene. The evidence implicating each gene is presented in Supplementary Data 11.

Alleles are listed as Effect allele/other allele, the effect allele frequency (EAF) in Europeans (average EAF, weighted by the sample size of each cohort).

Genome build = GRCh37/hg19.

ars4643526 at the same locus was previously identified in the discovery analysis of Paternoster et al. 2. However, this association did not replicate in that study.

bWhilst not identified in any GWAS AD papers, these loci have previously shown evidence for association with AD in supplementary material of methodological papers92,93.

cOne of two or three tied genes at these loci are shown.

The SNP-based heritability (h2SNP) for AD was estimated to be 5.6% in the European discovery meta-analysis (LDSC intercept=1.042 (SE = 0.011)). This is low in comparison to heritability estimates for twin studies (~80%)15,16, but comparable with previous h2SNP estimates for AD in Europeans (5.4%)6.

Multi-ancestry GWAS

In a multi-ancestry analysis including individuals of European, Japanese, Latino and African ancestry (Supplementary Data 2, N = 1,086,394; 65,107 AD cases and 1,021,287 controls), a total of 89 loci were identified as associated with AD (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1). 75 of these were not independent of lead variants identified in the European-only analysis (r2 > 0.01 in the relevant ancestry) and a further 9 showed some evidence for association (Bonferroni corrected P < 0.05/89 = 5.6 × 10−4) in the European analysis, but 5 were not associated (P > 0.1) in Europeans (Table 3, Supplementary Data 4).

Table 3.

Additional loci associated with the multi-ancestry analysis

| Multi-ancestry discovery | European discovery | RIKEN - Biobank Japan | 23andMe Latino | 23andMe African | 23andMe European | Known | Novel | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 992,907 | N = 864,982 | N = 118,287 | N = 525,348 | N = 174,015 | N = 2,904,664 | Associations | Associations | |||

| Variant | Chr:position | Alleles (EAF) | P | P | P | P | P | P | ||

| rs114059822a | 1:19804918 | T/G (0.03) | 8.59E−09 | 0.25 | – | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.87 | NA | NA |

| rs9247 | 2:234113301 | T/C (0.21) | 1.92E−09 | 7.32E−08 | 7.71E−05 | 1.49E−13 | 7.23E−03 | 2.93E−51 | allb | |

| rs9864845 | 3:112383847 | A/G (0.37) | 2.17E−12 | 0.22 | 3.92E−13 | 0.75 | 0.23 | 0.12 | Japanese (Tanaka et al.8) | |

| rs34599047 | 6:106629690 | C/T (0.18) | 3.32E−08 | 1.29E−07 | 0.03 | 7.18E−04 | 0.02 | 3.23E−22 | allb | |

| rs7773987 | 6:135707486 | T/C (0.60) | 1.22E−08 | 9.57E−08 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 1.95E−03 | 5.93E−13 | European, African | |

| rs118029610a | 9:1894613 | T/C (0.03) | 1.89E−08 | 2.97E−04 | – | 0.5 | 0.31 | 0.78 | NA | NA |

| rs117137535 | 9:140500443 | A/G (0.03) | 1.99E−08 | 5.50E−08 | – | 3.99E−07 | 0.33 | 9.25E−19 | European (Grosche et al.7) | Latino |

| rs4312054 | 11:7977161 | G/T (0.43) | 3.21E−12 | 0.86 | 3.46E−15 | 0.4 | 0.33 | 0.52 | Japanese (Tanaka et al.8) | |

| rs150113720a | 11:83439186 | G/C (0.02) | 5.52E−10 | 0.40 | – | 0.1 | 0.22 | 0.14 | NA | NA |

| rs115148078a | 11:101361300 | T/C (0.02) | 5.91E−09 | 0.37 | – | 3.69E−03 | 0.91 | 0.89 | NA | NA |

| rs4262739 | 11:128421175 | A/G (0.50) | 2.20E−08 | 6.03E−07 | 2.28E−03 | 1.89E−06 | 0.09 | 1.45E−36 | European & Japanese (Tanaka et al.8) | Latino |

| rs1059513 | 12:57489709 | C/T (0.08) | 5.15E−09 | 1.57E−07 | 0.33 | 3.06E−04 | 0.17 | 6.95E−16 | European (Tanaka et al.8) | Latino |

| rs4574025 | 18:60009814 | T/C (0.55) | 7.00E−10 | 1.48E−06 | 2.67E−05 | 2.59E−04 | 1.24E-05 | 2.96E−05 | European & Japanese (Tanaka et al.8) | Latino, African |

| rs6023002 | 20:52797237 | C/G (0.52) | 4.05E−10 | 2.26E−06 | 2.82E−07 | 5.96E−03 | 0.07 | 3.22E−28 | European & Japanese (Tanaka et al.8) | Latino |

For loci that were associated in the multi-ancestry discovery analysis, but not the European discovery analysis, we show the (unadjusted two-sided) P-values for association across 4 diverse ancestral groups, European, Japanese, Latino and African. Full association statistics (including OR and 95% CI) for each variant can be viewed in Supplementary Data 4 (and results across all cohorts individually are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2).

Alleles are reported as effect allele/other allele.

Genome build = GRCh37/hg19.

NA indicates finding not replicated and likely to be false-positive in discovery.

Bold is used in the novel column to denote the 3 associations that are entirely novel (i.e. locus has not been associated in any ancestry previously).

– Variant was not available in dataset.

aGenome-wide significant loci without replication that are assumed to be false positives in the discovery data.

bWhilst not identified in any GWAS AD papers, these loci have previously shown evidence for association with AD in the supplementary material of methodological papers92 or GWAS of combined allergic disease phenotype5.

Of the 14 loci that reached genome-wide significance in the multi-ancestry discovery analysis only (Table 3), 8 replicated in at least one of the replication samples (of European, Latino and/or African ancestry; Bonferroni corrected P < 0.05/14 = 3.6 × 10−3). Two index SNPs which did not replicate in any of the samples (rs9864845 (near CCDC80), rs4312054 (near NLRP10)) appear to have been driven by association in the Japanese RIKEN study only (Supplementary Data 4, Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). Whilst the allele frequencies of these index SNPs are similar between Europeans and Japanese (37% vs 42% for rs9864845, 41% vs 46% for rs4312054, Supplementary Data 5), in a multi-ancestry fixed effect meta-analysis at both these loci there were neighbouring (previously reported)8 SNPs with stronger evidence of association (rs72943976, P = 2 × 10−9 and rs59039403 P = 2 × 10−35, Supplementary Fig. 3), that did show large allele frequencies for Japanese (~34% and 13%, respectively) but <1% in Europeans. A further 4 loci did not replicate, and on closer examination (Supplementary Fig. 2, and MAF in cases <1%), their association in the discovery analysis appeared to be driven by a false positive outlying result in a single European cohort.

Seven of the loci in Table 3 have been previously reported as associated with AD. Two (rs117137535 (near ARRDC1)7 and rs1059513 (near STAT6)8) were previously only associated with Europeans (and these were variants that were just below the genome-wide significance threshold in our European only analysis). Three (rs4262739 (near ETS1), rs4574025 (within TNFRSF11A) and rs6023002 (near CYP24 A1)) were previously associated in Japanese and Europeans8, while 2 were previously associated only in Japanese8,10, using the same Japanese data (RIKEN) that we include here. Therefore, in our multi-ancestry analysis (and replication) we identify 3 loci that have not previously been reported in a GWAS of AD of any ancestry (rs9247 (near INPP5D), rs34599047 (near ATG5) and rs7773987 (near AHI1)), all of which are associated in two or more populations in our data (Table 3).

In addition, for 5 loci which had previously been associated with individuals of European and/or Japanese ancestry, we now show evidence that these are also associated with individuals of Latino ancestry and one is also associated in individuals of African ancestry (Table 3).

Comparison of associations between ancestries

Effect sizes of the index SNPs were remarkably similar between individuals of European and Latino ancestry (Supplementary Fig. 4A). There were only two variants with any evidence for a difference (where Latino P > 5 × 10−4 and the 95% confidence intervals didn’t overlap), but the plot shows that these were only marginally different and likely to be due to chance. Effect size comparison of the index SNPs between individuals of European and African ancestry showed greater differences (Supplementary Fig. 4B). 17 SNPs showed some evidence for being European-specific in that comparison. The confidence intervals in the Japanese data were much wider but there was weak evidence for one SNP being European-specific and stronger evidence for two SNPs being Japanese-specific (Supplementary Fig. 4C). These were rs4312054 (JAP CI: 0.75-0.84, EUR CI: 0.99-1.01) and rs9864845 (JAP CI: 1.16-1.30, EUR CI: 0.99-1.06), mentioned earlier as the SNPs that appeared to be driven only by Japanese individuals in the multi-ancestry meta-analysis (Supplementary Data 4).

Established associations

A review of previous work in this field (Supplementary Data 1) shows that a total of 202 unique variants (across a much smaller number of loci) have been reported to be associated with AD. We found evidence for all but 7 variants of these being nominally associated in the current GWAS (81% in the European and 96% in the multi-ancestry analysis). Variants we did not find to be associated were either rare variants (MAF < 0.01), or insertion/deletion mutations, which were not included in our analysis.

Genetic correlation between AD and other traits

LD score regression analyses showed high genetic correlation, as expected, between AD and related allergic traits, e.g. asthma (rg=0.53, P = 2 × 10−32), hay fever (rg=0.51, P = 7 × 10−17) and eosinophil count (rg = 0.27, P = 1 × 10−7) (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 6). In addition, depression and anxiety showed notable genetic correlation with AD (rg = 0.17, P = 2 × 10−7), a relationship which has been reported previously, but causality has not been established17. Furthermore, gastritis also showed substantial genetic correlation (rg = 0.31, P = 1 × 10−5), which may be due to the AD genetic signal including variants with pervasive inflammatory function or the observed correlation could indicate a shared risk locus for inflammation or microbiome alteration in the upper gastrointestinal tract, or it may reflect the use of systemic corticosteroid treatment for atopic disease which in some cases causes gastritis as a side effect.

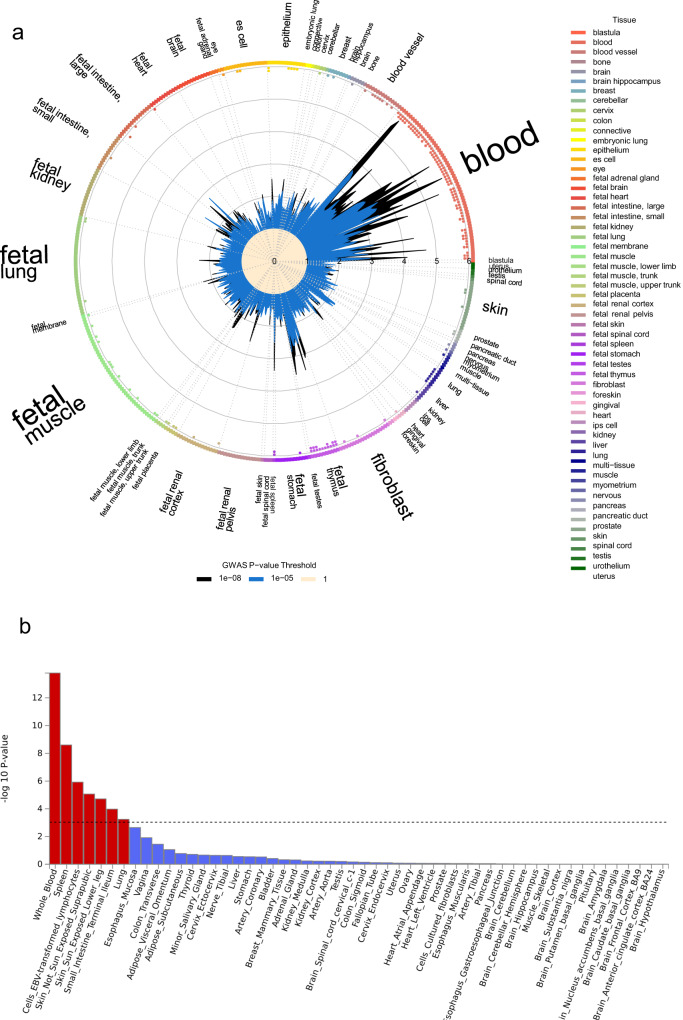

Tissue, cell and gene-set enrichment

The tissue enrichment analyses using distinct molecular evidence (representing open chromatin and gene expression) both found blood to be the tissue showing strongest enrichment of GWAS loci (Fig. 2). The Garfield test for enrichment of genome-wide loci (with P < 1 × 10−8) in DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHS broad peaks) found evidence of enrichment (P < 0.00012) in 41 blood tissue analyses, a greater signal than another tissue or cell type (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 7). The strongest enrichment (OR > 5.5 and P < 1 × 10−10) was seen for T-cell, B-cell and natural killer lymphocytes (CD3+, CD4+, CD56+ and CD19+). As expected for AD, Th2 showed stronger enrichment (OR = 4.3, P = 1 × 10−8) than Th1 (OR = 2.3, P = 2 × 10−4). The strongest enrichment in tissue samples representing skin was seen for foreskin keratinocytes (OR = 2.0, P = 0.008), but this did not meet a Bonferroni-corrected P-value threshold (0.05/425 = 1 × 10−4).

Fig. 2. Cell type tissue enrichment analysis.

a GARFIELD enrichment analysis of open chromatin data. Plot shows enrichment for AD associated variants in DNase I Hypersensitive sites (broad peaks) from ENCODE and Roadmap Epigenomics datasets across cell types. Cell types are sorted and labelled by tissue type. ORs for enrichment are shown for variants at GWAS thresholds of P < 1 × 10−8 (black) and P < 1 × 10−5 (blue) after multiple-testing correction for the number of effective annotations. Outer dots represent enrichment thresholds of P < 1 × 10−5 (one dot) and P < 1 × 10−6 (two dots). Font size of tissue labels corresponds to the number of cell types from that tissue tested. b MAGMA enrichment analysis of gene expression data. Plot shows P-value for MAGMA enrichment for AD associated variants with gene expression from 54 GTEx ver.8 tissue types. The enrichment –log10(P-value) for each tissue type is plotted on the y-axis. The Bonferroni corrected threshold P = 0.0009 is shown as a dotted line and the 7 tissue types that meet this threshold are highlighted as red bars.

The most enriched tissue type in MAGMA gene expression enrichment analysis was whole blood (P = 2 × 10−14). Others that met our Bonferroni-corrected P-value (P < 0.0009) were spleen, EBV-transformed lymphocytes, sun-exposed and unexposed skin, small intestine and lung (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Data 8).

DEPICT cell-type enrichment analysis identified a similar set of enriched cell-types: blood, leucocytes, lymphocytes and natural killer cells, but with the addition that the strongest enrichment was seen for synovial fluid (P = 2 × 10−7), which may be due to its immune cell component.

The DEPICT pathway analysis found 420 GO terms with enrichment (FDR < 5%) amongst the genes from our GWAS loci (Supplementary Data 9). The pathway with the strongest evidence of enrichment was ‘hemopoietic or lymphoid organ development’ (P = 1 × 10−16). All terms with FDR < 5% are represented in Supplementary Fig. 6, where the terms are grouped according to similarity and the parent terms labelled illustrating the strong theme of immune system development and signalling.

Gene prioritisation and biological interpretation in silico

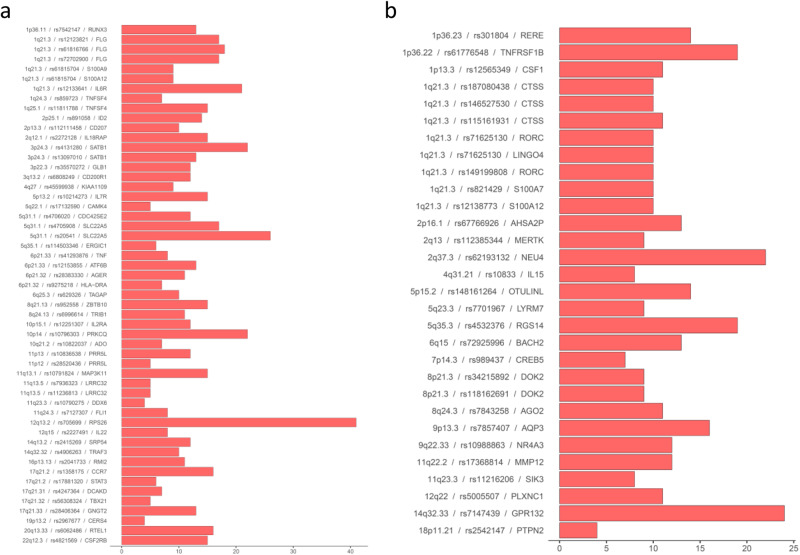

The top genes prioritised using our composite score from publicly available data for each of the established European AD loci are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3a (and the evidence that makes up the prioritisation scores is shown in Supplementary Fig. 7). The top three prioritised genes at each independent locus are shown in Supplementary Data 10 and a summary of all evidence for all genes reviewed in silico is presented in Supplementary Data 11.

Fig. 3. Prioritised genes at GWAS loci.

Prioritised genes at known (a) and novel (b) loci. For each independent GWAS locus the top prioritised gene (or genes if they were tied) from our bioinformatic analysis is presented along with a bar representing the total evidence score for that gene. A more detailed breakdown of the constituent parts of this evidence score is presented in Supplementary Fig. 5 and the total evidence scores for the top 3 genes at each locus are presented in Supplementary Data 10. NB. There are some cases of two independent GWAS signals implicating the same gene.

In most cases the top prioritised gene had been implicated (in previous GWAS) or is only superseded marginally by an alternative candidate. One interesting exception is on chromosome 11, where MAP3K11 (with a role in cytokine signalling – regulating the JNK signalling pathway) is markedly prioritised over the previously implicated OVOL118 (involved in hair formation and spermatogenesis), although the prioritisation of MAP3K11 is predominantly driven by TWAS evidence in multiple cell types rather than colocalisation or other evidence.

There are three instances where multiple associations in the region implicate additional novel genes. Two are genes involved in TLR4 signalling: S100A9 (prioritised in addition to the established FLG and IL6R on chromosome 1) and AGER (prioritised in addition to HLA-DRA on chromosome 6). The third has a likely role in T-cell activation: CDC42SE2 (prioritised in addition to SLC22A5 on chromosome 5).

The top prioritised gene at each of the novel European loci are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3b. Many are in pathways already identified by previous findings (e.g. cytokine signalling—specially IL-23, antigen presentation and NF-kappaB proinflammatory response). At one locus, the index SNP, rs34215892 is a missense (Pro274Leu) mutation within the DOK2 gene, although this mutation is categorised as tolerated or benign by SIFT and PolyPhen. The genes with the highest prioritisation score amongst the novel loci were GPR132 (total evidence Score=24), NEU4 (score=22), TNFRSF1B (score = 19) and RGS14 (score=19) and each show biological plausibility as candidates for AD pathogenesis.

GPR132 is a proton-sensing transmembrane receptor, involved in modulating several downstream biological processes, including immune regulation and inflammatory response, as reported previously in an investigation of this protein’s role in inflammatory bowel disease19. The index SNP at this locus, rs7147439 (which was associated with Europeans, Latinos, Africans, but not Japanese), is an intronic variant within the GPR132 gene. The AD GWAS association at this locus colocalises with the eQTL association for GPR132 in several immune cell types (macrophages20, neutrophils21, several T-cell datasets22) as well as in colon, lung and small intestine in GTEx23. GPR132 has also been shown to be upregulated in lesional and nonlesional skin in AD patients, compared to skin from control individuals24,25. OpenTargets and POSTGAP both prioritise GPR132 for this locus.

The SNP rs62193132 (which showed consistent effects in European, Latino and Japanese individuals, but little evidence for association in African individuals, Supplementary Fig. 2), is in an intergenic region between NEU4 (~26 kb) and PDCD1 (~4 kb away) on chromosome 2. NEU4 was the highest scoring in our gene prioritisation pipeline (score=22). However, PDCD1 also scores highly (score = 18, Supplementary Data 10). NEU4 is an enzyme that removes sialic acid residues from glycoproteins and glycolipids, whereas PDCD1 is involved in the regulation of T cell function. The AD GWAS association at this locus colocalises with the eQTL for NEU4 in several monocyte and macrophage datasets22,26–28 as well as in the ileum, colon and skin23,29. The eQTL for PDCD1 also colocalises in monocytes and macrophages27,28 as well as T-cells22, skin and whole blood23. In addition to the eQTL evidence, PCDC1 is upregulated in lesional and non-lesional skin in AD patients compared to skin from control individuals24,25. OpenTargets and PoPs prioritise NEU4, whilst POSTGAP prioritises PDCD1 at this locus.

TNFRSF1B is part of the TNF receptor, with an established role in cytokine signalling. rs61776548 (which showed consistent associations across all major ancestries tested) is 136 kb upstream of TNFRSF1B, actually within an intron of MIIP. MIIP encodes Migration and Invasion-Inhibitory Protein, which may function as a tumour suppressor. However, TNFRSF1B is a stronger candidate gene since the AD GWAS association at this locus colocalises with the eQTL for TNFRSF1B T cells22,30, macrophages20, fibrobasts31 and platelets29. Furthermore, TNFRSF1B gene expression and the corresponding protein are upregulated in lesional and nonlesional skin compared to controls24,25,32 and the PoPs method prioritised this gene at this locus.

RGS14 is a multifunctional cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling protein which regulates G-protein signalling, but whose role in the immune system is yet to be established. rs4532376 is 10.5 kb upstream of RGS14 and within an intron of LMAN2. The AD GWAS association at this locus colocalises with the eQTL for RGS14 in macrophages20, CD8 T-cells22, blood33 and colon23. RGS14 has also been shown to be upregulated in lesional skin of AD cases compared to skin from control individuals25 and DEPICT prioritises this gene. However, at this locus LMAN2 is also a reasonably promising candidate (score=15) based on colocalisation and differential expression evidence (Supplementary Data 11). OpenTargets and POSTGAP prioritise this alternative gene at this locus and it is possible that genetic variants at this locus influence AD risk through both genetic mechanisms.

We did not include the 3 novel variants from the multi-ancestry analysis in the comprehensive gene prioritisation pipeline because the available resources used predominantly represent European samples only. We did however investigate these variants using Open Targets Genetics, to identify any evidence implicating specific genes at these loci. rs9247 is a missense variant in INPP5D, encoding SHIP1, a protein that functions as a negative regulator of myeloid cell proliferation and survival. The INPP5D gene has been implicated in hay fever and/or eczema5 and other epithelial barrier disorders including inflammatory bowel disease. rs7773987 is intronic for AHI1 (Abelson helper integration site 1) which is involved with brain development but expressed in a range of tissues throughout the body; single cell analysis in skin shows expression in multiple cell types including specialised immune cells and keratinocytes, but the highest abundance is in endothelial cells (data available from v21.1 proteinatlas.org). The closest genes to rs34599047 are ATG5 (involved in autophagic vesicle formation) and PRDM1 (which encodes a master regulator of B cells).

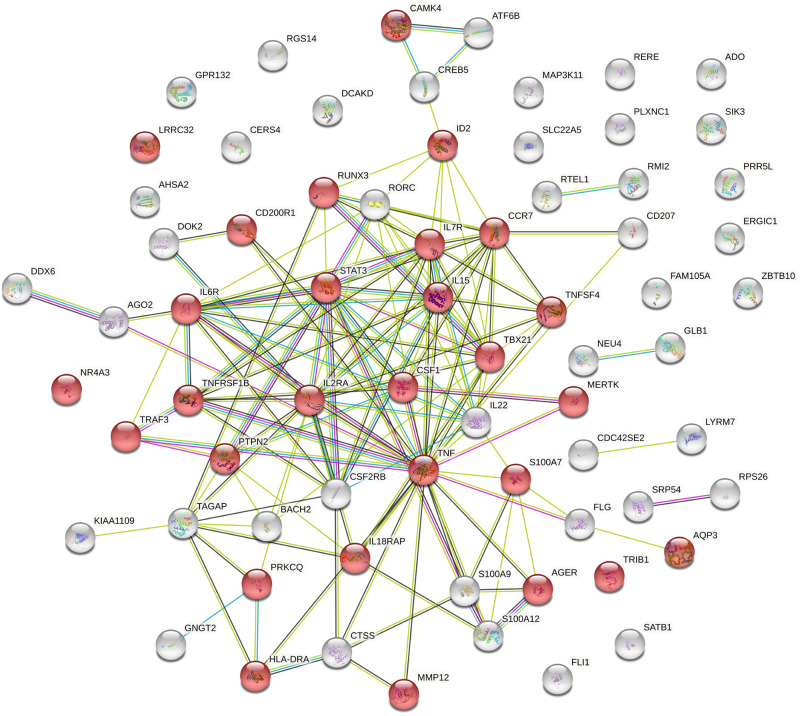

Network analysis

STRING network analysis of the 70 human proteins encoded by genes listed in Tables 1 and 2 showed a protein-protein interaction (PPI) enrichment p-value < 1 × 10−16. The five most highly significant (FDR P = 1 × 10−9) Gene Ontology (GO) terms for biological process relate to immune system activation and regulation (Supplementary Data 12). The network described by the highly enriched term ‘Regulation of immune system process’ (GO:0002682) is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Predicted interaction network of proteins encoded by the top prioritised genes from known and novel European GWAS loci.

Protein-protein interaction analysis carried out in STRING v11.5; nodes coloured red represent the GO term ‘Regulation of immune system process’ (GO:0002682) for which 28/1514 proteins are included (FDR P = 1 × 10−9). Full results for all identified pathways are available in Supplementary Data 12.

Extending the network to include the less well characterised genes/proteins from the multi-ancestry analysis further strengthened this predicted network: The PPI enrichment was again P < 1 × 10−16 and ‘Regulation of immune system process’ was the most enriched term (FDR P = 5 × 10−13).

Discussion

We present the results of a comprehensive genome-wide association meta-analysis of AD in which we have identified a total of 91 associated loci. This includes 81 loci identified amongst individuals of European ancestry replicated in a further sample of 2.9 million European individuals (as well as many showing replication in data for other ancestries). Of the additional 10 loci identified in a multi-ancestry analysis, 8 replicated in at least one of the populations tested (European, Latino and African ancestry) and a further 2 may be specific to individuals of East Asian ancestry (but require replication).

The majority of the loci associated with AD are shared between the ancestry groups represented in our data, though there were some notable exceptions. We report two previously identified loci with associations that appear to be specific to the Japanese cohort (although driven by just one cohort and still require independent replication). Whilst these have been previously reported8, this used the same data as examined here. However, rs59039403 within NLRP10 is a likely deleterious missense mutation at reasonable frequency in Japanese (13%) that is present at a far lower frequency (<1%) in Europeans. Equally, previous further investigation of the association near CCDC80 found a putative functional variant (rs12637953) that affects the expression of an enhancer (associated with CCDC80 promoter) in epidermis and Langerhans cells8, increasing the evidence that these Japanese-specific loci are real. Furthermore, we have identified several loci with association in Europeans (many of which also showed association in individuals of Japanese or Latino ancestry) but which showed no evidence of association in individuals of African ancestry. It is tempting to speculate, using our knowledge of the differing AD phenotypes between European, Asian and African people34,35 that the differing genetic associations at some loci may contribute to these clinical observations. rs7773987 within an intron of AHI1 may, for example, indicate a mechanism contributing to neuronal sensitisation leading to the marked lichenification and nodular prurigo-type lesions36 that characterise AD in some people of African and European ethnicities37. Large-scale population cohorts (as used here) have been useful for identifying associated variants. However, we do note that the variants identified should be further examined with respect to specific aspects of AD (age of onset, severity and longitudinal classes38) in future analysis.

The dominance of blood as the tissue showing most enrichment of our GWAS signals in regions of DNAse hypersensitivity and of eQTLs suggests the importance of systemic inflammation in AD and this is in keeping with knowledge of the multisystem comorbidities associated with AD39. The dominance of blood also supports the utility of this easily accessible tissue when characterising genetic risk mechanisms, and for the measurement of biomarkers for many of the implicated loci. However, skin tissue also showed enrichment and there are likely to be some genes for which the effect is only seen in skin. For example, we know that two genes previously implicated in AD, FLG and CD2072,18 are predominantly expressed in the skin and in our gene prioritisation investigations there was no evidence from blood linking FLG to the rs61816766 association and only one analysis of monocytes separated from peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples28 which implicated CD207 for the rs112111458 association, amongst an abundance of evidence from skin for both genes playing a role in AD (Supplementary Data 11). So, whilst the enrichment analysis suggests blood as a useful tissue for genome scale studies of AD and a reasonable tissue to include for further investigation at specific loci, it does not preclude skin as the more relevant tissue for a subset of important genes.

At many of the loci identified in this GWAS, our gene prioritisation analysis, as well as the DEPICT pathway analysis, implicated genes from pathways that are already known to have a role in AD pathology. The overwhelming majority of these are in pathways related to immune system function; STRING network analysis highlighted the importance of immune system regulation, in keeping with an increasing awareness of the importance of balance in opposing immune mechanisms that can cause paradoxical atopic or psoriatic skin inflammation40. Whilst our in silico analyses cannot definitively identify specific causal genes (rather, we present a prioritised list of all genes at each locus along with the corresponding evidence for individual evaluation), it is of note that for many of the previously known loci (Table 1) our approach identifies genes which have been validated in experimental settings, e.g. FLG41, TNF42 and IL2243. The individual components of the gene prioritisation analysis have their limitations, particularly the high probability that findings, whilst demonstrating correlation, do not necessarily provide evidence for a causal relationship. This has been particularly highlighted with respect to colocalisation of GWAS and eQTL associations, where high co-regulation can implicate many potentially causal genes44. Another limitation is that only cell types (and conditions) that have been studied and made available are included in the in silico analysis, and gaps in the data may prove crucial. However, we believe this broad-reaching review of complementary datasets and methods is a useful initial approach to summarise the available evidence, prioritise genes for follow-up and provide information to inform functional experiments. The best evidence is likely to be produced from triangulation of multiple experiments and/or datasets and we have presented our workflow and findings in a way to allow readers to make their own assessments. Another important limitation of our gene prioritisation, is that we only undertook the comprehensive approach for loci associated in European individuals, given that the majority of datasets used come from (and may only be relevant for) European individuals. Expansion of resources that allow for similarly comprehensive follow-up of GWAS loci in individuals of non-European ancestry are urgently needed45. However, we do report some evidence that implicates certain genes at loci from our multi-ancestry analysis, whilst noting that these require further investigation in appropriate samples from representative populations.

Amongst the genes prioritised at the novel loci identified in this study, four are targets of existing drugs (and have the required direction of action consistent with the AD risk allele’s direction of effect on the gene expression) as reported by Open Targets46: CSF1 is targeted by a macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 inhibiting antibody (in phase II trials as cancer therapy but also for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and cutaneous lupus); CTSS is targeted by a small molecule cathepsin S inhibitor (in phase I-II trials for coeliac disease and Sjogren syndrome); IL15, targeted by an anti-IL-15 antibody (in phase II trials for autoimmune conditions including vitiligo and psoriasis); and MMP12, targeted by small molecule matrix metalloprotease inhibitors (in phase III studies for breast and lung cancer, plus phase II for cystic fibrosis and COPD)47. These may offer valuable drug repurposing opportunities.

We have presented the largest GWAS of AD to date, identifying 91 robustly associated loci, 22 with some evidence of population-specific effects. This represents a significant increase in knowledge of AD genetics compared to previous efforts, taking the number of GWAS hits identified in a single study from 31 to 91 and making available the well-powered summary statistics to enable many future important studies (e.g. Mendelian Randomization to investigate causal relationships). To aid translation we have undertaken comprehensive post-GWAS analyses to prioritise potentially causal genes at each locus, implicating many immune system genes and pathways and identifying potential novel drug targets.

Methods

Appropriate ethical approval was obtained for all cohorts by their ethics committees as detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Phenotype definition

Cases were defined as those who have “ever had atopic dermatitis”, according to the best definition for the cohort, where doctor-diagnosed cases were preferred. Controls were defined as those who had never had AD. Further details on the phenotype definitions for the included studies can be found in Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Data 2.

GWAS analysis and quality control of summary data

We performed genome-wide association analysis (GWAS) for AD case-control status across 40 cohorts including 60,653 AD cases and 804,329 controls of European ancestry. We also included cohorts with individuals of mixed ancestry (Generation R), as well as Japanese (Biobank Japan), African American (SAGE II and SAPPHIRE) and Latino (GALA II) studies, giving a total of 65,107 AD cases and 1,021,287 controls.

Genetic data was imputed separately for each cohort with the majority of European cohorts using the haplotype reference consortium (HRC version r1.1) reference panel48 (imputed with either the Michigan or Sanger server). 8 European and 2 non-European cohorts instead used the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 1 reference panel for imputation. GWAS was performed separately for each cohort while adjusting for sex and ancestry principal components derived from a genotype matrix (as appropriate in each cohort). Genetic variants were restricted to a MAF > 1% and an imputation quality score > 0.5 unless otherwise specified in the Supplementary Methods. In order to robustly incorporate cohorts with small sample sizes, we applied additional filtering based on the expected minor allele count (EMAC) as previously demonstrated49. EMAC combines information on sample size, MAF and imputation quality (2*N*MAF*imputation quality score) and a threshold of >50 EMAC was used to include variants for all cohorts. QQ-plots and Manhattan plots for each cohort were generated and visually inspected as part of the quality control process.

Meta-analysis

For the discovery phase, meta-analysis of the European cohorts was performed with GWAMA47 for 12,147,822 variants assuming fixed effects, while the multi-ancestry analysis of all cohorts was conducted in MR-MEGA50 (which models the heterogeneity in allelic effects that is correlated with ancestry). The latter included only 8,684,278 variants as MR-MEGA excludes variants where the number of contributing cohorts is less than 6. P < 5 × 10−8 was used to define genome-wide significance. Clumping was performed (in PLINK 1.9051) to identify independent loci. We formed clumps of all SNPs which were ±500kb of each index SNP with a linkage disequilibrium r2 > 0.001. Only the index SNP within each clump is reported. For multi-ancestry index variants within 500 kb of index SNPs identified in the European-only analysis, we considered these to be independent if the lead multi-ancestry SNP was not in LD (r2 < 0.01) with the lead neighbouring European variant. Multi-ancestry fixed effect meta-analysis was also performed for comparison with the MR-MEGA results.

Known/Novel assignment

Novel associations are defined as a SNP that had not been reported in a previous GWAS (Supplementary Data 1), or was not correlated (r2 < 0.1 in the relevant ancestry) with a known SNP from this list. In addition, following the assignment of genes to loci (see gene prioritisation) any locus annotated with a gene that has been previously reported were also moved to the ‘known’ list. Therefore, some loci which are reported in Open Targets52,53 (but not reported in a published AD GWAS study) have been classed as novel. These loci are marked as such in Table 2.

Conditional analysis

Conditional analysis was performed to identify any independent secondary associations in the European meta-analysis. Genome-wide complex trait analysis-conditional and joint analysis (GCTA-COJO54) was used to test for independent associations 250 kb either side of the index SNPs using UK Biobank HRC imputed data as the reference. COJO-slct was used to determine which SNPs in the region were conditionally independent (using default P < 1 × 10−5) and therefore represent independent secondary associations. COJO-cond was then used to condition on the top hit in each region to determine the conditional effect estimates.

Replication

The genome-wide index SNPs identified from the European and mixed-ancestry discovery meta-analyses were taken forward for replication in 23andMe, Inc. Individuals of European (N = 2,904,664), Latino (N = 525,348) and African ancestry (N = 174,015) were analysed separately. Full details are available in the Supplementary Methods.

LD score regression

Linkage disequilibrium score (LDSC) regression software (version 1.0.1)55 was used to estimate the SNP-based heritability (h2SNP) for AD. This was performed with the summary statistics of the European discovery meta-analysis. The h2SNP was estimated on liability scale with a population prevalence of 0.15 and a sample prevalence of 0.070.

Genetic correlation with other traits was assessed using all the traits available on CTG-VL56 (accessed on 5th November 2021). We considered phenotypes with p-values below the Bonferroni-corrected alpha threshold (i.e., 0.05/1376 = 4 × 10−5) to be genetically correlated with AD (a conservative threshold given the likely correlation between many traits tested).

Bioinformatic analysis

For the following analyses we defined the regions within which the true causal SNP resides to be determined by boundaries containing furthest distanced SNPs with r2 >= 0.2 within ±500kb of the index SNP18. We refer to such regions as locus intervals and we used them as input for the analyses described below.

Enrichment analysis

Enrichment of tissues and cell types and gene sets for AD GWAS loci was investigated using DEPICT57 and GARFIELD (GWAS analysis of regulatory or functional information enrichment with LD correction)58 ran with default settings, as well as MAGMA v.1.0659 (using GTEx ver. 823 on the FUMA60 platform). In addition, we used MendelVar61 run with default settings to check for enrichment of any ontology terms assigned to Mendelian disease genes within the locus interval regions.

By default, MAGMA only assigns variants within genes. DEPICT maps all genes within a given LD (r2 > 0.5) boundary of the index variant. DEPICT gene set enrichment results for GO terms only were grouped (using the Biological Processes ontology) and displayed using the rrvgo package. The default scatter function was adapted to only plot parent terms62.

Prioritisation of candidate genes

To prioritise candidate genes at each of the loci identified in the European GWAS, we investigated all genes within ±500 kb of each index SNP (selected to capture an estimated 98% of causal genes)63. The approach used has been previously described by Sobczyk et al.18. For each gene we collated evidence from a range of approaches (as described below) to link SNP to gene, resulting in 14 annotation categories (represented as columns in Supplementary Fig. 7). We summarised these annotations for each gene into a score in order to prioritise genes at each locus. We present the top prioritised gene in the main tables, but strength of evidence varies and so we encourage readers to use our full evaluation (of all the evidence presented in Supplementary Data 11 for all genes at each locus) for loci of interest.

We tested for colocalisation with molecular QTLs, where full summary statistics were available, using coloc64 method (with betas as input). We used the eQTL Catalogue65 and Open GWAS66 to download a range of eQTL datasets from all skin, whole blood and immune cell types as well as additional tissue types which showed enrichment for our GWAS loci, such as spleen and oesophagus mucosa18. A complete list of eQTL datasets20–23,26–31,33,67–71 is displayed in Supplementary Data 13. pQTL summary statistics for plasma proteins72 were downloaded from Open GWAS. An annotation was included in our gene prioritisation pipeline if there was a posterior probability >95% that the associations from the AD GWAS and the relevant QTL analysis shared the same causal variant.

Additional colocalisation methods were also applied. TWAS (Transcriptome-Wide association Study)-based S-MultiXcan73 and SMR (Summary-based Mendelian Randomization)74 were run on datasets available via the CTG-VL platform (including GTEx tissue types and 2 whole blood pQTL72,75 datasets available for the SMR pipeline). For S-MultiXcan and SMR, we report only results with p-values below the alpha threshold established with Bonferroni correction, as well as no evidence of heterogeneity (HEIDI P-value > 0.05) in SMR analysis.

Genes were also annotated if they were included in any of the globally enriched ontology/pathway terms from the MendelVar analysis described above or if they were identified in direct look-ups of keywords: “skin”, “kera”, “derma” in their OMIM76 descriptions, or Human Phenotype Ontology77/Disease Ontology78 terms.

We also used machine learning candidate gene prioritisation pipelines – DEPICT57, PoPs79, POSTGAP80 and Open Targets Genetics53 Variant 2 Gene mapping tool as well as gene-based MAGMA59 test. We added annotations to genes reported in the top 3 (by each of the pipelines).

We mined the literature for a list of differential expression studies and found 9 RNA-Seq/microarray plus 4 proteomic analyses involving comparisons of AD lesional25,32,81–84 or AD nonlesional24,25,32,82,85–87 skin vs healthy controls. Studies with comparisons of AD lesional acute vs chronic88, blood proteome in AD vs healthy control32 and FLG knockdown vs control in living skin-equivalent89 were also included. We annotated each gene (including direction of effect, i.e. upregulated/downregulated) with FDR < 0.05 in any dataset.

Lastly, we annotated genes where the index SNP resided within the coding region according to VEP (Variant Effect Predictor)90 analysis.

For each candidate gene, we established a pragmatic approach to combine all available evidence in order to prioritise which the most plausible candidate gene(s). This prioritisation was carried out as follows:

The number of annotations (each representing one piece of evidence) were summed across all methods and datasets, to derive a ‘total evidence score’, i.e., if coloc evidence was observed for 5 datasets for a particular gene, this would add 5 to the score for that gene.

Additionally, to assess if evidence was coming from multiple datasets using the same method, or evidence was coming from diverse approaches, we counted ‘evidence types’, summing up the methods (as opposed to datasets) with an annotation for each gene tested (up to a maximum of 14), i.e., in the same example of coloc evidence observed in 5 datasets, this would add 1 to this measure for this gene. Evidence types are represented by the columns in Supplementary Fig. 7.

In order to prioritise genes with the most evidence, whilst ensuring there was some evidence of triangulation across methods, at each locus we prioritised the gene with the highest ‘total evidence score’ with a minimum ‘evidence type’ of 3. ‘Evidence type’ was also used to break ties.

Network analysis

Network analysis of the prioritised genes was carried out using standard settings (minimum interaction score 0.4) in STRING v11.591.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

For this work, A.B.-A., S.J.B. and L.P. were funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (JU) under grant agreement No. 821511 (BIOMAP). The J.U. receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA. This publication reflects only the author’s view and the J.U. is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. A.B.A., M.K.S., J.L.M., and L.P. and work in a research unit funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00011/1 and MC_UU_00011/4). LP received funding from the British Skin Foundation (8010 Innovative Project) and the Academy of Medical Sciences Springboard Award, which is supported by the Wellcome Trust, The Government Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the Global Challenges Research Fund and the British Heart Foundation [SBF003\1094]. S.J.B. holds a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship in Clinical Science [220875/Z/20/Z]. S.H. is supported by a Vera Davie Study and Research Sabbatical Bursary, NRF Thuthuka Grant (117721), NRF Competitive Support for Unrated Researcher (138072), MRC South Africa under a Self-initiated grant. M.S. has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 949906). Thanks to Sergi Sayols (developer of rrvgo), who provided additional code to alter the scatter plot produced by rrvgo to only display parent terms, and to Gibran Hemani (University of Bristol) who provided valuable guidance on the comparison of effects between ancestries. This publication is the work of the authors and LP will serve as guarantor for the contents of this paper. This work was carried out using the computational facilities of the Advanced Computing Research Centre, University of Bristol—http://www.bristol.ac.uk/acrc/. Individual cohort acknowledgements are in the Supplementary Methods.

Author contributions

Designed and co ordinated the study: M.St., L.P. Performed the meta analysis: A.B.-A., A. Ki. Performed the bioinformatic analysis: M.K.So. Performed the STRING analysis: S.J. Br. Performed statistical analysis within cohorts: A.B.-A., A. Ki, R. Mi, K.R., R. Mä, M.N., N.T., B.M.B., L.F.T., P.S.N., C.F., A.E.O., E.H.L., J.V.T.L., J.B.J., I.M., A.A.-S., A.J., H. Ba., E.R., A. Ku., C.M.G., C.H., C.Q., P.T., E.A., J.F., C.A.W., E.T., B.W., S.K., D.M.K., L.K., J.D., H.Z., C.A., V.U., R.K., A. Sz., A.C.S.N.J., A.G., M.I., M. M.-Nu., T.S.A., M.B., C.G., M.P.Y., D.P.S., N.G., Y.A.L., A.D.I., L.K.W., C.M., S.J. Br. Data acquisition/supported analysis/interpretation of data: A.B.-A., A. Ki, A.R., P.S.N., A.J., C.j.X., S.E.H., J.F., E.T., S.K., H.Z., S.H., T. Ho., E.J., H.C., N.R., P.N., O.A.A., S.J., C.A., T.G., V.U., P.K.E.M., E.G.B., J.P.T., T. Ha., L.L.K., T.M.D., A.Ar., G.H., S.L., M.M. Nö., N.H., M.I., T.S.Ah., J.S., B.C., A.M.M.S., A.E., S.Ar., T.E., L.A.M., A.M., C.T., K.A., M.L., K.H., B.J., D.P.S., Y.A.L., N.P.H., S.W., A.D.I., D.J., T.N., L.D., J.M.V., G.H.K., K.M.G., B.F., C.E.P., P.D.S., P.G.Ho., H. Bi., K.B., J.C., A. Si., T.S., S.J. Br., M.St., L.P. Wrote the paper: A.B.-A., A. Ki, M.K.So., S.J. Br., M.S., L.P. Approved final version of paper: A.B.-A., A. Ki, M.K.So., S.S.S., R. Mi, K.R., A.R., R. Mä, M.N., N.T., B.M.B., L.F.T., P.S.N., C.F., A.E.O., E.H.L., J.V.T.L., J.B.J., I.M., A.A.-S., A.J., K.A.F., H. Ba., E.R., A.C.A., A. Ku., P.M.S., X.C., C.M.G., C.H., C.j.X., C.Q., S.E.H., P.T., E.A., J.F., C.A.W., E.T., B.W., S.K., D.M.K., L.K., J.D., H.Z., S.H., T. Ho., E.J., H.C., N.R., P.N., O.A.A., S.J., C.A., T.G., V.U., R.K., P.K.E.M., A. Sz., E.G.B., J.P.T., T. Ha., L.L.K., T.M.D., A.C.S.N.J., A.G., A.Ar., G.H., S.L., M.M. Nö., N.H., M.I., A.V., M.F., V.B., P.Hy., N.B., D.I.B., J.J.H., M.M.-Nu., T.S.Ah., J.S., B.C., A.M.M.S., A.E., M.B., B.R., S.Ar., C.G., T.E., L.A.M., A.M., C.T., K.A., M.L., K.H., B.J., M.P.Y., D.P.S., N.G., A.L., Y.A.L., N.P.H., S.W., M.R.J., E.M., H.H., A.D.I., D.J., T.N., L.D., J.M.V., G.H.K., K.M.G., S.J. Ba., B.F., C.E.P., P.D.S., P.G.Ho., L.K.W., H. Bi., K.B., J.C., A. Si., C.M., T.S., S.Bu., S.T.W., J.W.H., J.L.M., S.J. Br., M.St., L.P.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Summary statistics of the GWAS meta-analyses generated in this study have been deposited in the GWAS Catalog under study accession IDs GCST90244787 and GCST90244788. The variant-level data for the 23andMe replication dataset are fully disclosed in the main tables and supplementary tables. Individual-level data are protected and are not available due to data privacy laws, and in accordance with the IRB-approved protocol under which the study was conducted.

Code availability

Code for the bioinformatic analysis is available here: https://github.com/marynias/eczema_gwas_fu/tree/bc4/new_gwas.

Competing interests

K.M.G. has received reimbursement for speaking at conferences sponsored by companies selling nutritional products, and is part of an academic consortium that has received research funding from Abbott Nutrition, Nestec, BenevolentAI Bio Ltd. and Danone. C.G., S.S.S., and 23andMe Research Team are employed by and hold stock or stock options in 23andMe, Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ashley Budu-Aggrey, Anna Kilanowski.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Marie Standl, Lavinia Paternoster.

Deceased: Hans Bisgaard.

Lists of authors and their affiliations appear at the end of the paper

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-41180-2.

References

- 1.Weidinger S, et al. Atopic dermatitis. The Lancet. 2016;387:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00149-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paternoster L, et al. Multi-ancestry genome-wide association study of 21,000 cases and 95,000 controls identifies new risk loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1449–1456. doi: 10.1038/ng.3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paternoster L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies three new risk loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:187–192. doi: 10.1038/ng.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weidinger S, et al. A genome-wide association study of atopic dermatitis identifies loci with overlapping effects on asthma and psoriasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:4841–4856. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson Å, Rask-Andersen M, Karlsson T, Ek WE. Genome-wide association analysis of 350 000 Caucasians from the UK Biobank identifies novel loci for asthma, hay fever and eczema. Assoc. Stud. Article. 2019;28:4022–4041. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sliz E, et al. Uniting biobank resources reveals novel genetic pathways modulating susceptibility for atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022;149:1105–1112.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grosche S, et al. Rare variant analysis in eczema identifies exonic variants in DUSP1, NOTCH4 and SLC9A4. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26783-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka N, et al. Eight novel susceptibility loci and putative causal variants in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021;148:1293–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaarschmidt H, et al. A genome-wide association study reveals 2 new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136:802–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirota T, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Japanese population. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/ng.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim KW, et al. Genome-wide association study of recalcitrant atopic dermatitis in Korean children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136:678–684.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun L-D, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Chinese Han population. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:690–694. doi: 10.1038/ng.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esparza-Gordillo J, et al. A functional IL-6 receptor (IL6R) variant is a risk factor for persistent atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;132:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellinghaus D, et al. High-density genotyping study identifies four new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:808–812. doi: 10.1038/ng.2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen FS, Holm NV, Henningsen K. Atopic dermatitis. A genetic-epidemiologic study in a population-based twin sample. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1986;15:487–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schultz Larsen F. Atopic dermatitis: a genetic-epidemiologic study in a population-based twin sample. J Am Acad. Dermatol. 1993;28:719–723. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70099-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Budu-Aggrey A, et al. Investigating the causal relationship between allergic disease and mental health. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2021;51:1449–1458. doi: 10.1111/cea.14010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobczyk MK, et al. Triangulating molecular evidence to prioritize candidate causal genes at established atopic dermatitis loci. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2021;141:2620–2629. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2021.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng Z, et al. Roles of G protein-coupled receptors in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020;26:1242–1261. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i12.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alasoo K, et al. Shared genetic effects on chromatin and gene expression indicate a role for enhancer priming in immune response. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:424. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L, et al. Genetic drivers of epigenetic and transcriptional variation in human immune cells. Cell. 2016;167:1398–1414.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmiedel BJ, et al. Impact of genetic polymorphisms on human immune cell gene expression. Cell. 2018;175:1701–1715.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science. 2020;369:1318–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winge MCG, et al. Filaggrin genotype determines functional and molecular alterations in skin of patients with atopic dermatitis and ichthyosis vulgaris. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He H, et al. Tape strips detect distinct immune and barrier profiles in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021;147:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fairfax BP, et al. Innate immune activity conditions the effect of regulatory variants upon monocyte gene expression. Science. 2014;343:1246949. doi: 10.1126/science.1246949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nédélec Y, et al. Genetic ancestry and natural selection drive population differences in immune responses to pathogens. Cell. 2016;167:657–669.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quach H, et al. Genetic adaptation and neandertal admixture shaped the immune system of human populations. Cell. 2016;167:643–656.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Momozawa Y, et al. IBD risk loci are enriched in multigenic regulatory modules encompassing putative causative genes. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2427. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04365-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasela S, et al. Pathogenic implications for autoimmune mechanisms derived by comparative eQTL analysis of CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutierrez-Arcelus M, et al. Passive and active DNA methylation and the interplay with genetic variation in gene regulation. Elife. 2013;2:e00523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavel AB, et al. The proteomic skin profile of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis patients shows an inflammatory signature. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020;82:690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buil A, et al. Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions detected by transcriptome sequence analysis in twins. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:88–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nomura T, Wu J, Kabashima K, Guttman-Yassky E. Endophenotypic variations of atopic dermatitis by age, race, and ethnicity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020;8:1840–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yew YW, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the regional and age-related differences in atopic dermatitis clinical characteristics. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019;80:390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ständer HF, Elmariah S, Zeidler C, Spellman M, Ständer S. Diagnostic and treatment algorithm for chronic nodular prurigo. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020;82:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2021;14:S20–S22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paternoster L, et al. Identification of atopic dermatitis subgroups in children from 2 longitudinal birth cohorts. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018;141:964–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396:345–360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Janabi A, Foulkes AC, Griffiths CEM, Warren RB. Paradoxical eczema in patients with psoriasis receiving biologics: a case series. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022;47:1174–1178. doi: 10.1111/ced.15130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McAleer MA, Irvine AD. The multifunctional role of filaggrin in allergic skin disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;131:280–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Danso MO, et al. TNF-α and Th2 cytokines induce atopic dermatitis-like features on epidermal differentiation proteins and stratum corneum lipids in human skin equivalents. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2014;134:1941–1950. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutowska-Owsiak D, Schaupp AL, Salimi M, Taylor S, Ogg GS. Interleukin-22 downregulates filaggrin expression and affects expression of profilaggrin processing enzymes. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011;165:492–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]