Abstract

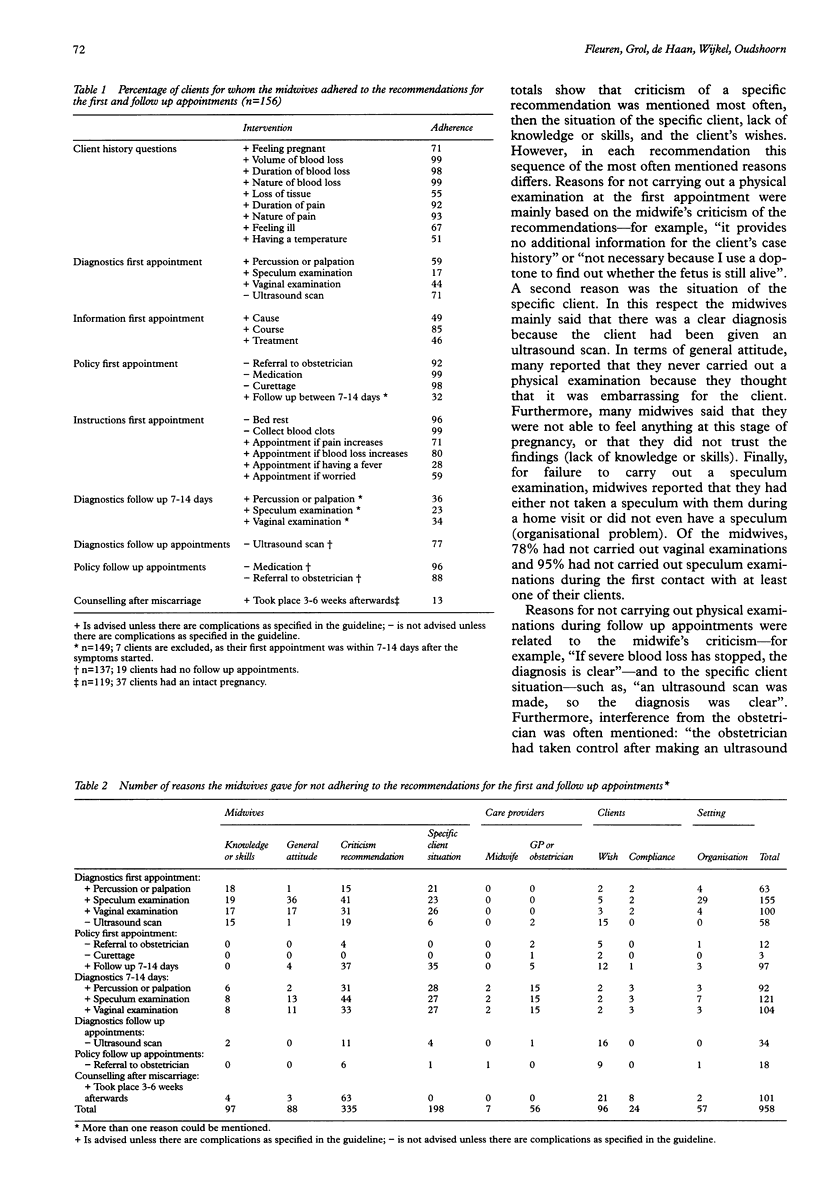

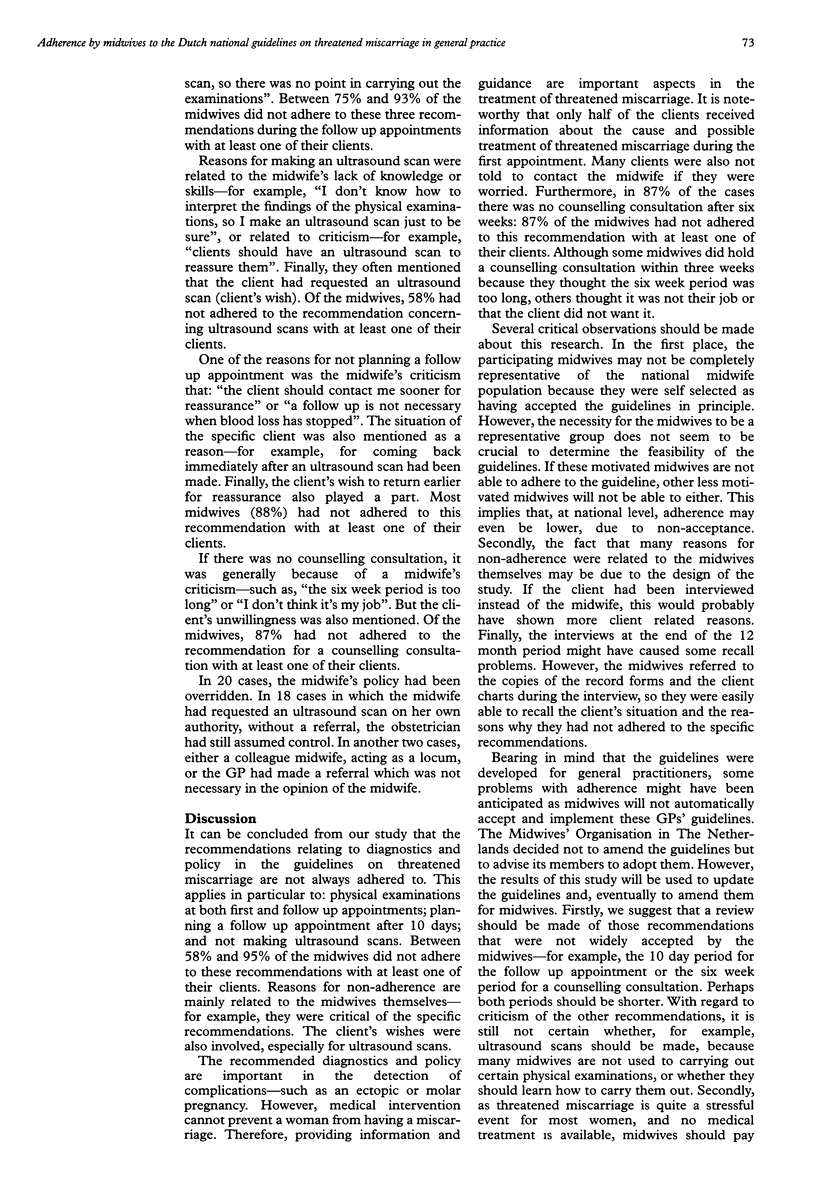

OBJECTIVE: To determine the feasibility for midwives to adhere to Dutch national guidelines on threatened miscarriage in general practice. DESIGN: Prospective recording of appointments by midwives who agreed to adhere to the guidelines on threatened miscarriage. Interviews with the midwives after they had recorded appointments for one year. SETTING: Midwifery practices in The Netherlands. SUBJECTS: 56 midwives who agreed to adhere to the guidelines; 43 midwives actually made records from 156 clients during a period of 12 months. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Adherence to each recommendation and reasons for non-adherence. RESULTS: The recommendation that a physical examination should take place on the first and also on the follow up appointment was not always adhered to. Reasons for non-adherence were the midwives' criticism of this recommendation, their lack of knowledge or skills, and the specific client situation. Adherence to a follow up appointment after 10 days, a counselling consultation after six weeks, and not performing an ultrasound scan was low. Reasons for non-adherence were mainly based on the midwives' criticism of these recommendations and reluctance on the part of the client. Furthermore, many midwives did not give information and instructions to the client. It is noteworthy that in 13% of the cases the midwife's policy was overridden by the obstetrician taking control of the situation after the midwife had requested an ultrasound scan. CONCLUSIONS: Those recommendations in the guidelines on threatened miscarriage that are most often not adhered to should be reviewed. To reduce conflicts about ultrasound scans and referrals, agreement on the policy on threatened miscarriage should be mutually established between midwives and obstetricians.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chamberlain G. ABC of antenatal care, Vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy--I. BMJ. 1991 May 11;302(6785):1141–1143. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6785.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy M., Shannon W. Clinical guidelines: their implementation in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1995 Jul;45(396):371–375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleuren M., Grol R., de Haan M., Wijkel D. Care for the imminent miscarriage by midwives and GPs. Fam Pract. 1994 Sep;11(3):275–281. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman T., Gath D. The psychiatric consequences of spontaneous abortion. Br J Psychiatry. 1989 Dec;155:810–813. doi: 10.1192/bjp.155.6.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman T. Women's experiences of general practitioner management of miscarriage. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989 Nov;39(328):456–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J., Freemantle N., Wallace S., Russell I., Hurwitz B., Watt I., Long A., Sheldon T. Developing and implementing clinical practice guidelines. Qual Health Care. 1995 Mar;4(1):55–64. doi: 10.1136/qshc.4.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R. Development of guidelines for general practice care. Br J Gen Pract. 1993 Apr;43(369):146–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R. Implementing guidelines in general practice care. Qual Health Care. 1992 Sep;1(3):184–191. doi: 10.1136/qshc.1.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanouse D. E., Kallich J. D., Kahan J. P. Dissemination of effectiveness and outcomes research. Health Policy. 1995 Dec;34(3):167–192. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(95)00760-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr K. N. Guidelines for clinical practice: applications for primary care. Int J Qual Health Care. 1994 Mar;6(1):17–25. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/6.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. F., Williamson E., Glue J., Gordon Y. B., Grudzinskas J. G., Sykes A. Fetal loss after implantation. A prospective study. Lancet. 1980 Sep 13;2(8194):554–556. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91991-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer R., Kline J., O'Connor P., Shrout P., Johnson J., Skodol A., Wicks J., Susser M. Determinants of depressive symptoms in the early weeks after miscarriage. Am J Public Health. 1992 Oct;82(10):1332–1339. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.10.1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S., Hahlin M. Expectant management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet. 1995 Jan 14;345(8942):84–86. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox A. J., Weinberg C. R., O'Connor J. F., Baird D. D., Schlatterer J. P., Canfield R. E., Armstrong E. G., Nisula B. C. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1988 Jul 28;319(4):189–194. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807283190401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf S. H. Practice guidelines: what the family physician should know. Am Fam Physician. 1995 May 1;51(6):1455–1463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]