Abstract

Over the last decade, the United States has seen increasing antidemocratic rhetoric by political leaders. Yet, prior work suggests that such norm-violating rhetoric does not undermine support for democracy as a system of government. We argue that, while that may be true, such rhetoric does vitiate support for specific democratic principles. We test this theory by extending prior work to assess the effects of Trump’s norm-violating rhetoric on general support for democracy as well as for the principles of participatory inclusiveness, contestation, the rule of law, and political equality. We find that Trump’s rhetoric does not alter attitudes toward democracy as a preferred system but does reduce support for inclusiveness and equality among his supporters. Our findings suggest that elite rhetoric can undermine basic principles of American democracy.

Keywords: democratic norms, elite rhetoric, equality, participation, Trump

More voters cast ballots in the 2020 presidential election than ever before. Yet, within 6 mo of the election, 47 states had introduced bills to limit voting access (1), with Republicans increasingly supporting such limits (2). These trends follow numerous norm-violating statements by US political leaders, particularly Donald Trump. But does this rhetoric undermine support for democracy (i.e., institutions that facilitate “responsiveness of the government to the preferences of its citizens, considered political equals”; ref. 3)? Even if democratic erosion largely derives from elite actions (4), garnering tacit public approval for backsliding can provide crucial leeway (5). Despite a burgeoning literature on public attitudes about democratic norms (6, 7), the “causal effect of [elite] rhetoric on public attitudes toward democracy is [generally] not known” (8).

One exception is Clayton et al., who tested the effect of exposure to a selection of Trump’s tweets that departed from past practices by US presidents regarding elections (e.g., the 2020 election is rigged) or politics more generally (e.g., the media are dishonest). The authors found that exposure to election norm–violating rhetoric, relative to non-norm-violating placebos, reduced confidence and trust in elections and increased a belief that elections are rigged among those who approved of Trump (see also ref. 9). But they did not find an effect on support for democracy, as measured by items that assessed preferences for democracy versus autocracy.

We replicate and extend Clayton et al.’s work by incorporating measures that gauge whether citizens hold attitudes consistent with specific democratic principles (10). We follow Dahl’s seminal work (3) by assessing support for inclusiveness (“the larger the proportion of citizens who enjoy the right [to vote], the more inclusive the regime”) and contestation (“the extent of permissible opposition”; ref. 11). To this, we add an implied third dimension that the rule of law applies to everyone (3). We also include a fourth dimension that the government treats every member of society as political equals. While not part of his core definition, Dahl made clear that unequal political rights undermine democracy (12).

Results

Respondents were assigned to one of four experimental conditions: a) election norm violation, b) general norm violation, c) election placebo, or d) nonelection placebo. The first two conditions were as described earlier, the election placebo included Trump tweets that endorsed a candidate or encouraged voters to support them, and the nonelection placebo included Trump tweets that mentioned nonelection, relatively civil, descriptions of national events, such as responding to a hurricane. Respondents then answered the democracy–autocracy measure used by Clayton et al. and four distinct scales for inclusiveness, contestation, rule of law, and political equality (3-items each). Confirmatory factor analysis verified the hypothesized factor structure of the new scales (i.e., four distinct dimensions) using item-level indicators to model latent factors for each democratic principle. The measurement model provided good fit to the data: χ2(48) = 181.93, P = 0.02; RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = 0.94; SRMR = 05.

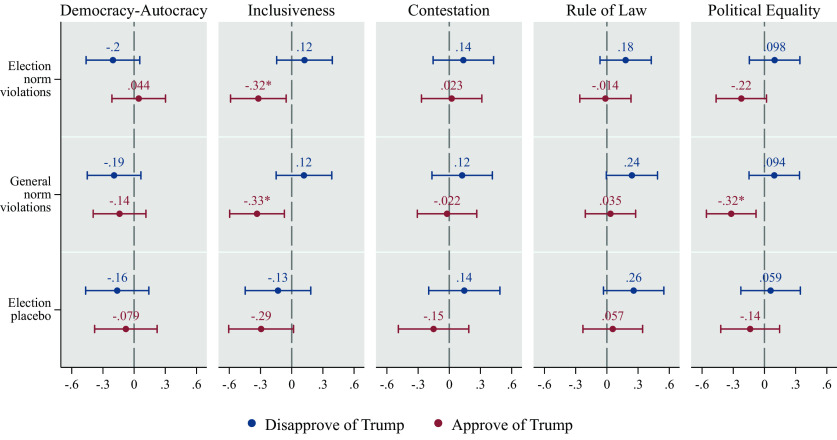

Using the nonelection placebo as the baseline, we found no significant effects for any experimental condition on support for democracy versus autocracy, inclusiveness, contestation, rule of law, or political equality (SI Appendix). However, we expected to only find effects among Trump supporters, given that they trust the source of the tweets. In Fig. 1, we present results separating Trump approvers vs. disapprovers (see SI Appendix for full regressions). Consistent with Clayton et al., we found no evidence that exposure to norm violations significantly affected democracy–autocracy preferences, regardless of Trump approval. However, as predicted, exposure to Trump’s norm-violating tweets decreased support for inclusiveness among Trump approvers: Election norm violations decreased support for inclusiveness by 0.32 SDs (P < 0.05), and general norm violations decreased support for inclusiveness by 0.33 SDs (P < 0.05). Neither type of norm violation had a statistically significant effect on support for contestation or the rule of law. But, among Trump approvers, general norm violations decreased support for political equality by 0.32 SDs (P < 0.05), and election norm violations fell just short of a statistically significant negative effect (P = 0.07).

Fig. 1.

The figure reports marginal effects of Trump tweets on support for democracy vs. autocracy, inclusiveness, contestation, the rule of law, and political equality, moderated by Trump approval. Capped bars represent 95% CIs. *P < 0.05 (two-tailed test). The excluded condition is the nonelection placebo. See SI Appendix for full regression results.

These findings are sensible insofar as the norm-violating content consistently involved claims of mistreatment—that Trump and Republicans face an invalid system with rigged elections or unfair treatment by other actors (such as the media). Limiting inclusiveness may directly address those grievances, as does undermining political equality. The more notable impact of general norm violations on reduced support for political equality likely reflects the rhetoric’s tendency to delegitimize other actors. Contestation and rule of law have less direct connection to constraining the political efficacy and equal status of opponents. Further, speech rights that constitute contestation have evolved to become a pillar of conservative ideology (13). In the SI Appendix, we report results from another experiment that fully replicate our findings among Trump approvers and provide evidence concerning the mechanism.

Lastly, for Trump disapprovers, tweets that violated election norms, that violated general norms, and even the election placebo all (nearly significantly) increased support for the rule of law. In exploratory analyses, we found that these effects primarily stem from a single item “The president should not be above the law.” Thus, exposure to Trump’s norm-violating tweets (or even tweets simply mentioning elections) may encourage those who disapprove of him to support greater restrictions on presidential power. Overall, Trump’s norm-violating rhetoric polarized democratic attitudes, with his approvers becoming less supportive of inclusiveness and political equality and his disapprovers potentially becoming more supportive of the rule of law.

Discussion

Various international indicators have downgraded the status of American democracy, with one report pointing to toxic polarization, captured partially by antagonistic cross-partisan rhetoric, as a key driver of this democratic backsliding (14). Yet, there is scant direct evidence of rhetoric affecting citizens’ opinions about democratic principles (beyond election confidence and legitimacy a la Clayton et al.). Even if erosion generally occurs via elite actions, such actions can include swaying citizens to accept backsliding as “normal” and not hold leaders accountable for it. Helmke et al. (15) show that Republicans uniquely benefit from limiting inclusive participation. We add to this by revealing how Donald Trump’s norm-violating rhetoric contributes to his supporters’ acceptance of such measures. More research is needed to establish how norm-violating rhetoric shapes views on specific policies and practices, as well as whether such rhetoric would have the same effects if it were not attributed to Trump. But the current results make clear that norm-violating rhetoric poses a threat to support for democratic tenets.

Methods

Data were collected via Forthright Access on a representative sample with the caveat (for our moderation) that half the sample were Republicans who approved of Trump and half were Democrats who disapproved of him (N = 804) (SI Appendix). Bots were screened out, as were low-effort respondents via two attention checks and participants who sped too quickly through the survey. Data were collected between June 22 and July 7, 2022. The study was approved by the Notre Dame IRB. All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study. Preregistration is available at https://aspredicted.org/rv8gn.pdf.

The design mirrored that of Clayton et al., although it did not look at repeated exposure. Each respondent received 20 of Trump’s actual tweets (as identified by Clayton et al.). Ten were unrelated to elections or norm violations; the other 10 depended on the condition (e.g., involved election norm violations in that condition; see SI Appendix). Participants then indicated their support for democracy vs. autocracy (e.g., “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress and elections”) on a four-point scale, and support for inclusiveness (e.g., “Voting should be easy”), contestation (e.g., “No idea is dangerous enough to justify censorship”), the rule of law (e.g., “The president should not be above the law”), and political equality (e.g., “Laws need to protect minority groups when society makes them vulnerable”) on seven-point scales. See SI Appendix for sample demographics, experimental stimuli, question wording, and deviations from preregistration.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

M.E.K.H. designed research; M.E.K.H. performed research; M.E.K.H. analyzed data; J.N.D. provided additional guidance re framing and approach; and M.E.K.H. and J.N.D. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Data files (16) and scripts necessary to replicate the results in this article have been made available at https://osf.io/ajwy3/.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Brennan Center, Voting laws roundup. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-laws-roundup-march-2021 (2021).

- 2.Pew Research Center, Republicans and democrats move further apart in views of voting access. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/04/22/republicans-and-democrats-move-further-apart-in-views-of-voting-access/ (2021).

- 3.Dahl R., Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 1971). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartels L., Democracy Erodes from the Top (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grillo E., Pratto C., Reference points and democratic backsliding. Amer. J. Pol. Sci. 67, 71–88 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingzette J., et al. , How affective polarization undermines support for democratic norms. Public Opin. Q. 85, 663–677 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasek M. H., Ankori-Karlinsky L. O., Levy-Vene A., Moore-Berg A. S. L., Misperceptions about out-partisans’ democratic values may erode democracy. Sci. Rep. 12, 16284 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clayton K., et al. , Elite rhetoric can undermine democratic norms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2024125118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arceneaux K., Truex R., Donald Trump and the lie. Perspect. Polit. 21, 863–879 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattes R., Thompson W., “Support for democracy” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia in Politics (Oxford University Press, New York, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coppedge M., Alvarez A., Maldonado C., Two persistent dimensions of democracy. J. Polit. 70, 335–350 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl R., Pluralist Democracy in the United States: Conflict and Consent (Rand McNally, Chicago, IL, 1967). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chong D., Citron J., Levy M., The realignment of political tolerance in the United States. Perspect. Polit. 1–22 (2022), 10.1017/S1537592722002079. [DOI]

- 14.Boese V. A., Lundstedt M., Morrison K., Sato Y., Lindberg S. I., State of the world 2021. Democratiz. 29, 983–1013 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmke G., Kroeger M., Paine J., Democracy by deterrence. Amer. J. Polit. Sci. 66, 434–450 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall M. E. K., Druckman J. N., Replication Data for Norm-Violating Rhetoric Undermines Support for Participatory Inclusiveness Among Trump Supporters. Open Science Foundation. Accessed 29 August 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

Data files (16) and scripts necessary to replicate the results in this article have been made available at https://osf.io/ajwy3/.