Abstract

Antitumor immunity is driven by CD8 T cells, yet we lack signatures for the exceptional effectors in tumors, amongst the vast majority of CD8 T cells undergoing exhaustion. By leveraging the measurement of a canonical T cell activation protein (CD69) together with its RNA (Cd69), we found a larger classifier for TCR stimulation-driven effector states in vitro and in vivo. This revealed exceptional ‘star’ effectors—highly functional cells distinguished amidst progenitor and terminally exhausted cells. Although rare in growing mouse and human tumors, they are prominent in mice during T cell-mediated tumor clearance, where they engage with tumor antigen and are superior in tumor cell killing. Employing multimodal CITE-Seq allowed de novo identification of similar rare effectors amidst T cell populations in human cancer. The identification of rare and exceptional immune states provides rational avenues for enhancement of antitumor immunity.

One sentence summary:

Parsing T cell activation states using a novel reporter mouse reveals the functional identity of potent anti-tumor CD8 T cells

Within broadly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments (TME), pockets of rare reactive immunity have been discovered, such as those containing conventional type 1 dendritic cells (cDC1s) that support T cells through antigen presentation (1). T cells, which integrate their encounters with antigens over their lifetime (2–4), require potent antigen stimulation for anti-tumor function. Yet chronic stimulation by persistent antigen in the TME also drives precursor TCF7hi CD8 T cells to dysfunctional or exhausted states (5) and cells with phenotypes defined as resident memory (TRM) also show strong evidence of exhaustion(6). Although this path to T cell exhaustion is increasingly well understood including developmental stages (7, 8), molecular markers (9–11), transcriptional, epigenetic (10–13) and microenvironmental drivers (14, 15), an intermediate and reactive T cell effector population that emerges from these precursors is not well-defined.

A novel genetic tool to report T cell stimulation history in vivo:

While the cell surface expression of a protein like CD69 is often linked to successful T cell stimulation and T cell retention (16), our analysis of a series of datasets showed that a history of repeated stimulation is associated with decreasing transcription of the Cd69 gene. For example, Cd69 mRNA itself is higher in naïve vs. effector and progenitor vs. terminally exhausted CD8 T cells (Fig. S1A–C), and in conventional T cells in tumor-adjacent normal areas versus those within paired human colorectal cancers (CRC) (Fig. S1D). Further mining of related data reveals that the transcription factors regulating Cd69 transcription were also differentially and systematically lower in exhausted vs. naïve CD8 T cells (Fig. S1E). In contrast, CD69 protein expression, driven by TCR stimulation or other stimuli such as interferons (17), is often uncoupled from transcriptional activity at this locus by strong 3’ UTR-mediated post-transcriptional regulation (18). We thus reasoned that tracking Cd69 RNA alongside its protein may together provide a useful means to differentiate the historical and current effector state of T cells.

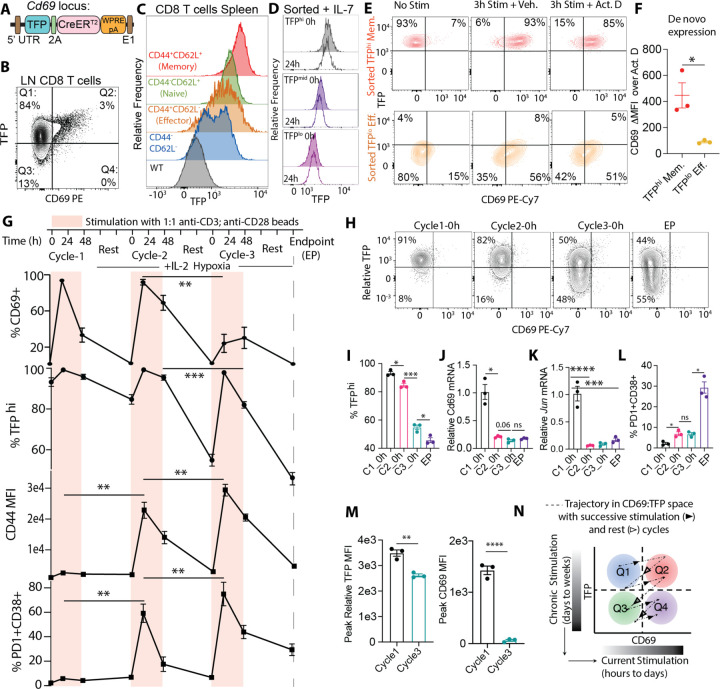

To make this tractable, we generated mice in which DNA encoding the teal fluorescent protein (TFP) was inserted at the 5’ end of the Cd69 locus to record its transcriptional activity (hereby referred to as the Cd69-TFP reporter) (Fig. 1A). In concert with antibody staining for surface CD69 protein, we thus had a non-invasive way to study, sort and challenge cells with different combinations of RNA and protein expression. In unchallenged Cd69-TFP mice, the majority (~80% “Q1”, Fig. 1B) of CD8 T cells in lymph nodes were TFPhi without expressing surface CD69. Another small population of cells expressed CD69 protein on their cell surface alongside TFP (~5%, “Q2”) and a moderate population (~15% “Q3”) was low for both TFP and CD69 (Fig. 1B). We validated that TFP accurately reflected Cd69 RNA expression at steady state (Fig. S2A–B) and found that the reporter faithfully tracked with well-established CD69 protein upregulation during the early and intermediate stages of thymic positive selection (19) as well as during the first 6–18h of stimulation of isolated peripheral T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 beads (Fig. S3A, B).

Fig.1: Cd69-TFP reporter reads out history of T cell stimulation.

(A) Design of the TFP-2A-CreERT2-WPRE-pA reporter knocked into the 5’ UTR of the Cd69 locus; (B) TFP vs. CD69 in homeostatic lymph node (LN) CD8 T cells with percentage of cells in each quadrant; (C) representative histograms of TFP expression in splenic CD8 T cells of different phenotypes (as indicated in the figure panel) from an unchallenged Cd69-TFP reporter mouse; (D) characteristic histograms of TFP expression from flow cytometry data from sorted TFPhi (top 20%), TFPmid (middle 30%) and TFPlo (bottom 20%) of splenic and lymph node-derived CD8 T cells at 0h and 24h post sort, resting in IL-7; (E) flow cytometry plots of TFP vs. CD69 in sorted TFPlo Effector and TFPhi Memory homeostatic CD8 T cells without stimulation (No Stim), 3h αCD3+αCD28 stimulation + DMSO (3h Stim + Vehicle) or 5μg/mL Actinomycin D (3h Stim + Act.D) and (F) relative change in CD69 MFI between the Vehicle and Act D treated conditions (de novo expression) in the two sorted groups, from data in S4B; (G) %CD69+, %TFPhi, CD44 MFI, %PD1+CD38+ of freshly isolated CD8 T cells through successive cycles of 48h stimulation and 72h resting in hypoxia + IL-2; (H) representative flow cytometry plots showing TFP vs. CD69, (I) %TFPhi, (J) Cd69 mRNA and (K) Jun mRNA by qPCR, (L) %PD1+CD38+ at the beginning of cycles 1, 2, 3 and endpoint (EP); (M) Peak Relative TFP and CD69 MFI between Cycle 1 and Cycle 3; (N) schematic showing the trajectory of CD8 T cells within the TFP:CD69 states (quadrants) with successive stimulation and rest, providing a reading of historic of stimulation. (Plots show mean +/− SEM; TFP negative gates derived from corresponding WT controls; statistical testing by ANOVA and post-hoc Holm-Šídák test; n=3 biological replicates representative of at least 2 independent experiments).

When viewed across differentiation states, we found that TFP expression varied with extent and quality of historical stimulation; CD44hiCD62Llo Effector CD8 T cells expressed levels lower than CD44loCD62Lhi Naïve cells as we had observed in historical datasets and CD44loCD62Lhi central memory T cells (Memory) demonstrated higher levels than either. (Fig. 1C). These differences in TFP expression were stable when cells were purified and rested in IL-7 overnight (Fig. 1D). Predictably, following short (3h) stimulation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads, TFPhi Memory and TFPlo Effectors (Fig. S4A) both rapidly upregulated surface CD69, even when new transcription was blocked by Actinomycin D, but maintained their pre-existing TFP status (Fig. 1E). However, de novo surface CD69 expression was markedly lower in TFPlo cells upon stimulation as compared to TFPhi (Fig. 1E–F, Fig. S4B), consistent with dependency of protein expression on the level of transcript. Together this indicated faithful reporter activity and also that a combination of Cd69 RNA reporting (TFP) and CD69 protein exposed a difference (i.e. Q2 vs. Q4) between recently activated cells with different histories of antigen experience.

To directly study how Cd69-driven TFP levels were related to activation history, we set up repetitive “chronic” stimulation cultures using purified CD8 T cells from Cd69-TFP mice. Cells were subjected to 3 cycles of 48h stimulation with 1:1 anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads, followed by 72h rest under either hypoxia (1.5% O2 to mimic the TME) or normoxia, in the presence of low concentrations of IL-2 after the first cycle (Fig. 1G, Fig. S5A). CD69 protein expression rose after each stimulation, although significantly less so by the 3rd stimulation, while expression of the activation marker CD44 became more pronounced (Fig 1G, Fig. S5A). Cd69-driven TFP levels also rose following each stimulation, but progressively rested each time to lower levels, an effect that culminated in about a 50% and 30% reduction under hypoxia and normoxia after 3 cycles, respectively (Fig 1G–H, Fig. S5A, B). We validated that both native Cd69 mRNA (Fig. 1J, Fig. S5C) as well as the upstream transcription factor Jun (Fig. 1K), decreased over the cycles, albeit with faster initial decay than TFP, perhaps reflecting a longer half-life of the fluorescent protein as compared to the transcript that it reports. Repeated stimulation concurrently upregulated exhaustion markers such as PD1, CD38 and Tim-3(20) (Fig. 1L, Fig. S5D, E). Provision of IL-2 in absence of additional anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation (Fig. S5F) demonstrated that differentiation (Fig. S5G), decline in TFP expression (Fig S5H), and acquisition of exhaustion markers (Fig. S5I) were not simply a function of time. While declining levels of resting mRNA did not prevent re-expression of TFP and CD69 upon stimulation, it significantly lowered the magnitude of the peaks from Cycle 1 to Cycle 3 (Fig. 1M, Fig. S5J), consistent with previous data (Fig. S4B). Thus in the Protein:RNA (CD69:TFP) space, trajectories of cell state are not retraced during subsequent activation events—rather, TFP levels decrease with repeated stimulation (Fig. 1N).“Q2” cells in this reporter system emerge as ones that are recently activated, yet have not been subject to chronic and exhaustive stimulation.

Delineation of chronic vs. potent activation states in tumors:

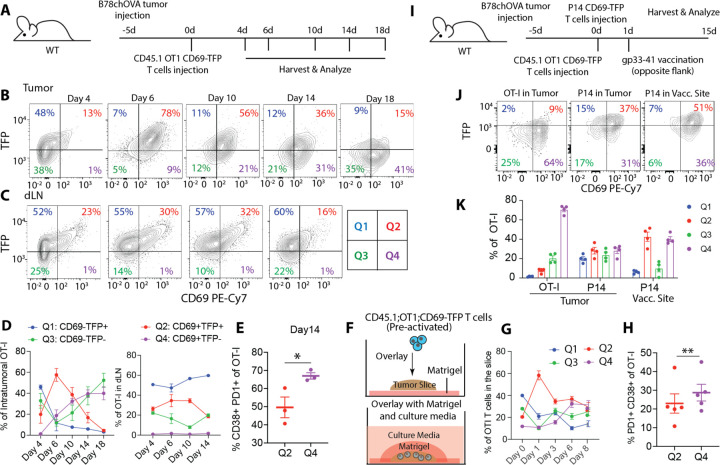

To translate these observations into the context of tumors, we adoptively transferred Cd69-TFP reporter positive ovalbumin-reactive CD8 T cells from CD45.1; OT-I; mice into WT mice bearing B78chOVA (OVA and mCherry expressed in B78 (14)) tumors (Fig. 2A). Recovered cells were largely in Q1 and Q3 on when they can be first detected at day 4, and by day 6, we found them predominantly in the “Q2” (~60%) TFPhiCD69+ state. By day 14, however, they were primarily TFPloCD69− (Q3) and TFPloCD69+ (Q4) (Fig. 2B, D). In contrast, the distribution of adopted cells was more consistent in the draining lymph node (dLN) across time: approximately 60% in Q1 and 15–30% in Q2. (Fig. 2C, D). Similar trends were observed in a spontaneous breast carcinoma tumor model (PyMTchOVA)(21) (Fig. S6A, B).

Fig. 2: Delineation of potent versus dysfunctional CD8 T cell activation states in tumors.

(A) Experimental schematic to track antigen-specific T cells in B78chOVA tumors over time; Flow cytometry plots showing TFP vs. CD69 of adoptively transferred OT-I T cells from (B) B78chOVA tumors and (C) corresponding tumor-draining lymph nodes (dLN) over time with the (D) CD69:TFP quadrant (Q1-Q4) distribution for the same; (E) %CD38+PD1+ terminally exhausted cells among activated d14 intratumoral OT-Is belonging to TFPhi Q2 and TFPlo Q4; (F) Schematic representation of long-term tumor slice culture setup; pre-activated: 48h stimulation with αCD3+αCD28 followed by 48h rest in IL-2; (G) CD69:TFP quadrant distribution and (H) %PD1+CD38+ of slice-infiltrating OT-I T cells at d8; (I) Experimental schematic of tumor injection and contralateral vaccination with orthogonal antigen specificities; (J) Flow cytometry plots showing TFP vs. CD69 profiles of OT-I, P14 T cells in the OVA+ tumor and P14 T cells at the gp33–41 vaccination (vacc.) site; (K) CD69:TFP quadrant distribution of the same. (Representative data from 2–3 independent experiments, 3–4 mice or 5–6 slices/timepoint/experiment, pre-slice-overlay samples in duplicate, plots show mean +/− SEM, *p <0.05, **p<0.01 by paired t-tests in E and H).

Even at day 14, Q2 cells expressed less terminal exhaustion markers as compared to those in the TFPlo Q4 in both B78chOVA (Fig. 2E) and PyMTchOVA tumors (Fig. S6C) and Q4 cells largely became prevalent in tumors approximately 10 days post-adoption (Fig. 2B–D, Fig. S6A, B). The decline in the Q2 proportion of OT-Is from d6 to d18 was also accompanied by a decrease in progenitor (Ly108) and increase in terminal exhaustion markers (Fig. S6D).

Because ongoing recruitment of T cells from the dLN is difficult to control and may obscure interpretation of these adoptive transfer experiments, we complemented these results by developing a variant of a long-term tumor slice overlay protocol(22) where all T cells encounter the tumor microenvironment at once and no new emigrants arrive (Fig. 2F). The progression of phenotypes through CD69:TFP quadrants (Fig. 2G, Fig. S7A) and the increasing over-representation of cells with an exhausted phenotype in Q4 (Fig. S7B–D) recapitulated what we had seen in vivo, suggesting that this is not a result of variations in the lymph-node emigrating pool. Slices also allowed easy analysis of robust proliferation in the slice-infiltrating OT-I T cells over time using violet proliferation dye (VPD) (Fig. S7E) which accompanied the general decrease in TFP expression with each division (Fig. S7F) and was exemplified at day 3 (Fig. S7G). VPD dilution showed that Q4 cells had typically undergone more division (Fig. S7H) as they acquired higher levels of exhaustion (Fig. 2H) as compared to Q2 cells, further differentiating these states. This progression is consistent with previous studies of the relationship between chronic tumor residence, proliferation(23, 24) and exhaustion, while also again differentiating the population in Q2.

Finally, to determine how this progression is related to antigen detection and the microenvironment in which that antigen is detected, we isolated CD8 T cells with a non-tumoral specificity (LCMV-specific P14; Cd69TFP) and compared their state both within a tumor (that does not express their antigen) and within a vaccination site, to that of the OT-Is (Fig 2I). P14; Cd69TFP cells co-injected with CD45.1; OT-I; Cd69TFP T cells into B78chOVA tumor-bearing mice, that also received a priming gp33–41 peptide vaccination distal to the tumor (Fig. 2I), were found to express higher TFP levels in the tumor than OT-Is (Fig. 2J, K). In contrast to the Q4-rich OT-I T cells in the tumor, P14 T cells at the contralateral vaccination site remained substantially TFPhi with a 4x increase in the frequency of cells Q2 (Fig. 2J, K). Hence, exposure to the TME alone did not lead to loss of a Q2 state, and presentation of antigen at a vaccine site stimulated cells in such a way as to maintain that Q2 state.

Marking the highest-quality intratumoral effectors:

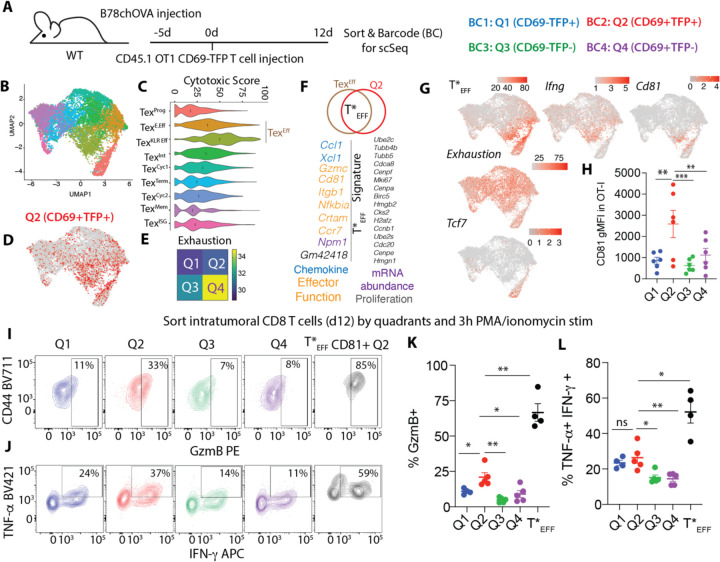

We next sought to both understand whether Q2 cells were typically better effectors and use transcriptomic analysis to find signatures that tracked best with Q2 cells. We thus isolated OTI; Cd69 TFP T cells from d12 B78chOVA tumors, sorted and barcoded each population separately for CD69:TFP quadrant and performed single cell RNA Sequencing (scSeq) (Fig. 3A). Analysis of this data via Louvain clustering and UMAP projection allowed us to immediately map Q2 in the context of previously defined post-exhaustion T cell states (TEX) (8), and other previously named intratumoral states that were based on RNA alone (Fig. 3B, Fig. S8A). Our data recapitulated those computationally derived predicted differentiation trajectories (Fig. S8B, C; See Methods) and the expected progression towards terminal exhaustion through the quadrants Q1-Q4 (Fig. S9)). Unbiased computational RNA-based clustering alone, however, did not capture a single subset with a superior cytotoxic score (Prf1, Klrd1, Gzmc, Tnfrsf9, Ifng), which was variably distributed across multiple subsets, although these are indeed more frequent within with exceptional levels in populations that have previously been named TexE.Eff, Texint and especially TexKLREff (Fig 3C).

Fig. 3: Single-cell mapping of activation states reveals functionally endowed intratumoral effectors.

(A) Experimental schematic for single cell transcriptomic profiling of intratumoral OT-I T cells sorted by CD69:TFP quadrants; (B) UMAP representation of the scSeq data color-coded by computationally-derived clusters; (C) Cytotoxic scoring of the T cell subsets (black lines =median); (D) overlay of Q2 (CD69+TFP+) in the UMAP space; (E) Heatmap exhaustion score of combined TEXEff subsets by quadrants; (F) Differentially upregulated genes in in Q2 vs. Q4 within the TEXEff cells to define T*EFF signature (color-coded text indicates predicted function of similarly colored genes); (G) Overlay of T*EFF signature score, Ifng, Cd81, Exhaustion Score, and Tcf7 in the UMAP space; (H) CD81 expression in d14 intratumoral OT-I T cells grouped by quadrants; Intracellular expression of (I) GzmB, (J) TNF-α and IFN-γ in intratumoral OT-I T cells sorted by quadrants and restimulated, with a sub-gating of CD81+ cells from Q2, with (K and L) corresponding quantification. pooled data from 2 independent experiments with 2–3 biological replicates (sorted cells from 2–3 tumors each)/experiment (K, L). Plots show mean +/− SEM; null hypothesis testing by paired RM ANOVA with post-hoc paired t-tests.

When we overlayed barcodes representing Q2 sorted cells onto this UMAP, we found that these spanned several clusters, and as expected with dominance in those TexEff (TexE.Eff, TexKLREff) populations as well as a subregion of the TexProg (Fig. 3D, Fig. S10A, B). Further and consistent with our previous observations, parsing these effectors by Cd69:TFP quadrant demonstrated the Q2 subset to be low and Q4 to be highest in a signature (Pdcd1, Cd38, Cd39, Entpd1, Tox) of exhaustion (Fig. 3E). Using this, we sought to use Q2 as an anchor, to characterize the transcriptional signature of the strongest effectors with robust cytotoxicity and limited exhaustion. We did so first by illuminating the intersection of TexEff and Q2, identifying a population that perhaps due to its sparsity and subtlety, doesn’t otherwise appear as a distinct computational cluster. Performing DGE analysis of Q2 vs. Q4 within that TEXEff, we found a signature comprising among others the granzyme Gzmc, a tetraspannin previously implicated in lymphocyte activation (25, 26) Cd81 and a collection of other genes that are consistent with a unique propensity to interact with other cells such as Xcl1 (putatively would attract cDC1) and Ccr7. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a population that may have unique stimulatory signals, we also found enrichment election of a subset of proliferation-associated genes.(Fig. 3F).

The resulting signature, which we term ‘star’ effectors or T*EFF for simplicity, highlights a portion of TexProg as well as a subset of cells buried within TexE.Eff and TexKLR Eff on a uMAP projection. (Fig 3G). These overlap only partially with cells that express the highest levels of Tcf7 and are nearly exclusive from those that are highest in markers of exhaustion (Fig. 3G, Fig. S11A). The distribution of this signature also tracks with genes associated with cytotoxicity (e.g. Ifng, which notably is not part of the signature), and significantly with Cd81, which in contrast is a component of the signature(Fig. 3G). Cd81 is a surface protein, making it useful for sorting but turns out to vary in its fidelity for reporting star effector phenotypes across various TME. For example, in the B78chOVA tumors, Q2 was reliably associated with ~3x increases in the mean level of CD81 surface protein expression (Fig. 3H), where in other models such as PyMTchOVA showed that this marker can also be found in cells that have not upregulated CD69 protein (i.e. Q1, Fig. S11C). Such variability limits absolute use of CD81 as a definitive marker across every tumor and site, and the use of this single marker in the PyMT model may be further limited since CD81+ T*EFFs were even rarer within these tumors (Fig. S11B, D).

Nonetheless, in the B78 tumor model, armed with a refined definition of T*EFF that could be non-invasively assessed through the combination of the Q2 reporter marking together with CD81 antibody staining, we sought to assess how effector function parsed with this population. For this we sorted OT-I T cells by the CD69:TFP quadrants with CD81 stain from tumors at d12 and assayed for cytokine and granzyme expression following restimulation with PMA/Ionomycin for 3h (Fig. 3I–L). Amongst the four quadrants, Q2 cells displayed the maximum functional capacity, both in terms of GzmB expression (Fig. 3I, K) and bifunctionality, as measured by TNF-α : IFN-γ double positivity (Fig. 3J, L). Strikingly, when we selected for CD81+ cells from within the Q2 compartment, i.e., a tighter gate for T*EFF (Fig. S11E), this further enriched for effector function, these cells having 2–10x higher expression of both %GzmB+ and % TNF-α+-IFN-γ+ compared to other populations (Fig. 3I–L). This data supports that sorting for the T*EFF signature enriches for high-quality effectors.

Prominence of functional effector pool during anti-tumor response:

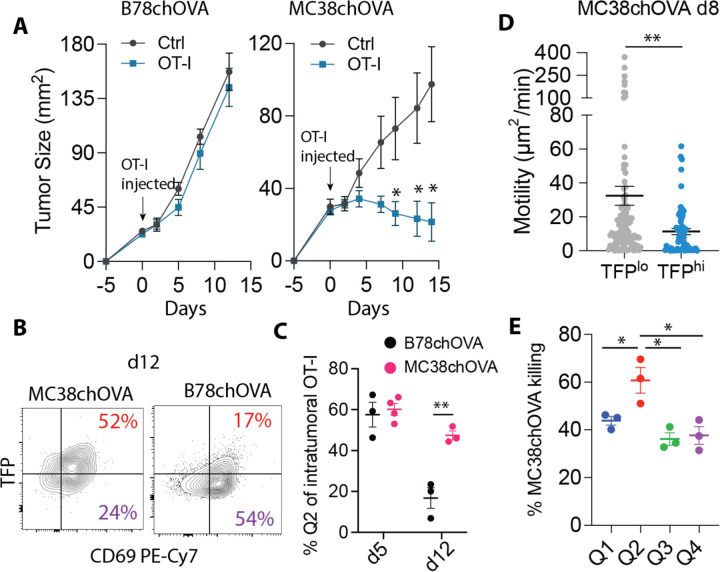

MC38chOVA tumors are actively controlled in response to the injection of antigen-specific OT-I T cells (Fig. 4A, Fig. S12A), whereas B78ChOVA are not. We found that Cd69-TFP;OT-I T cells in regressing MC38chOVA tumors, retain their predominantly Q2 (CD69+TFP+) phenotype even at d12 post adoptive transfer, in contrast to those in the growing B78chOVA tumors(Fig. 4B–C, Fig. S12B), while the TFPhi proportions in the corresponding dLNs was similar in both (MC38chOVA :Fig. S12C, B78chOVA : Fig. 2C, D). By two-photon microscopy TFPhi cells could be identified by post-imaging analysis of the appropriate channel intensity over non-TFP controls (Fig. S12D). Such analysis showed enhanced cell arrest of the TFPhi within MC38chOVA tumor slices harboring adopted OT-Is, with lower overall motility (Fig. 4D), speed (Fig. S12E), and persistence of motion (Fig. S12F). In both mouse (24) and human(22) tumors, these traits are associated with lower T cell exhaustion. Q2 OT-I cells sorted from MC38chOVA tumors also showed the highest killing capacity when exposed to MC38chOVA cells in vitro (Fig. 4E). In MC38 as in the B78 model, CD81 was enriched specifically in Q2 cells among intratumoral OT-Is (Fig. S12G). Using that surface marking, we found that CD81 was markedly more abundant in the ongoing antigen-specific anti-tumor response in MC38 tumors (Fig. S12H), as opposed to non-responsive B78chOVA and PyMTchOVA tumors (Fig. S11B, D). Moreover, Q2 and especially CD81+ T*EFFs also enriched for a recently-defined, non-canonical and durable CD39+Ly108+ effector population modestly in B78chOVA and robustly in MC38chOVA tumors. (27) (Fig. S12I).

Fig. 4: Prominence of potent CD8 effectors in favorable anti-tumor response.

(A) Contrasting growth curves of B78chOVA and MC38chOVA with and without OT-I transfer 5 days post tumor injection, as indicated by the color-coded arrows (n=5–6/group); (B) Typical flow cytometry plot of TFP vs. CD69 of intratumoral OT-Is d12 post adoptive transfer with (C) quantification of the percentage of Q2 cells at d5 and d12 in the two tumor models; (D) Motility of TFPhi vs. TFPlo intratumoral OT-Is d8 post adoptive transfer within live MC38chOVA tumor slices; (E) in vitro killing of MC38chOVA cells by OT-I T cells sorted by CD69:TFP quadrants from d8 MC38chOVA tumors; Bar plots show mean +/− SEM; n > 100 cells per group pooled from at least 2 slices each from different tumors (D); null hypothesis testing by unpaired t test (C), Mann-Whitney U test (D), ANOVA with post-hoc Holm-Šídák test (E).

De novo identification of star effectors by CITE-Seq in human patients:

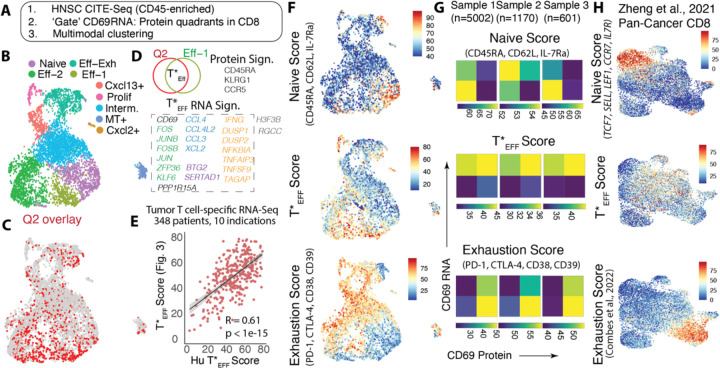

We next sought to independently identify similar CD8 activation states in human tumors (Fig. S13A), now using multimodal CITE-Seq on Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSC) tumor biopsies post CD45-enrichment (Fig. 5A). We focused first on pooled samples with a large number (~5000) of CD8 T cells, where simultaneous readouts of CD69 mRNA and surface protein allowed CD8 T cells to be gated into 4 quadrants (akin to reporter mice), with notable dominance in Q4 and Q2 (Fig. S13A, B). Again, presumably due to their rarity and the unbiased nature of combined protein-RNA driven weighted nearest neighbor determination, we did not isolate all Q2 cells into a single cluster. In contrast and akin to mouse studies, Q2 highlighted a subset of cells predominantly concentrated within an effector (Eff-1) subset with some also in the Eff-2, Eff-Exh and naive clusters (Fig. 5B, C, Fig. S13C, D).

Fig. 5: De novo identification of potent effectors in human cancer by CITE-Seq.

(A) Schematic description of human HNSC tumor CITE-Seq analysis; (B) UMAP showing weighted nearest neighbor (WNN) determined clusters by multimodal RNA and Protein analysis; (C) overlay of Q2 cells (determined by gating on CD69 Protein and RNA – Fig.S13B) on the UMAP; (D) Differentially upregulated genes and proteins in the T*EFF (Q2 ᑎ Eff-1) cells vs. all others CD8 T cells, genes color-coded by functional category, box indicates genes used for the T*EFF gene signature; (E) Correlation between this human T*EFF gene signature and that from human orthologs of the gene signature in Fig. 3F (F) Naïve, T*EFF and Exhaustion scores overlayed on the WNN UMAP, and (G) Heatmap representation of median levels of the same scores in CD8 T cells from 3 different patient samples split into CD69 protein: CD69 mRNA quadrants; (n: # of CD8 T cells in each sample); (H) Naïve, T*EFF and Exhaustion scores overlaid onto the UMAP of combined CD8 T cells from a previously published pan-cancer atlas (30).

DGE analysis of this small subset of Q2 cells within the Eff-1 cluster (<5% of the total CD8s) revealed a signature comprising of genes associated with activation-related transcription (CD69, and also upstream JUN, FOS, ZFP36, KLF6) where the former were notably those we initially associated as being downregulated following repeated stimulation. The human-derived signature also included chemokines (CCL3, CCL4, both high in the TexKLR.Eff in mice, Fig. S8A, CCL4L2, XCL2, closely related to XCL1 found in the mouse signature), as well as effector function (IFNG, DUSP1,2, NFKBIA, TNFSF9, etc.), mRNA abundance (SERTAD1, BTG2) and proliferation (Fig. 5D). In addition to these genes, the analysis also defined surface protein markers differentially upregulated in these T*EFFs including CCR5 and KLRG1 (Fig. 5D, Fig. S13E). Interestingly, the downregulated protein set not only included exhaustion markers CD38, CD39, 2B4, but also CD103 and CD69. Indeed, TRMs as defined simply by CD69+CD103+ exist both in Q2 and Q4 and their relation to exhaustion markers may be context-dependent(6) (Fig. S13E). Consistent with evolutionary divergence of immune systems(28), we found that RNA signatures were not identical and yet across 10 indications of human cancer (29), T cell-specific expression of the human T*EFF RNA gene signature correlated highly with that of the expression of human homologs of the RNA signature derived from our mouse tumor scSeq in Fig. 3 (Fig. 5E). Further, when this T*EFF RNA gene signature was overlaid back onto the UMAP, it again highlighted a region intermediate to and distinct from cells having highest expression of naïve and exhaustion markers (Fig. 5F). When applied to other HNSC samples (sample 2 and 3), this RNA T*EFF signature continued to be highest in cells defined by Q2 and distinct from naïve (variably highest in Q1 and Q3) and exhaustion (predictably highest in Q4) markers alike (Fig. 5G). Analysis of CD8 T cells in a second and independent pan-cancer T cell atlas(30) again revealed localization of T*EFF RNA-signaturehi cells in the intervening phenotypic space between naïve and exhausted cells (Fig. 5H, Fig. S14A). Notably, in this second and larger dataset, the authors had suggested multiple T cell subsets associated with enhanced function such as KLR-expressing NK-like CD8 T cells, ZNF683+CXCR6+ TRM (31) and IL7R+ memory T cells (32) and these were enriched for T*EFF RNA-signature, while exhausted and naïve subsets were not (Fig. S14B). Such pan-cancer delineation of potent effectors would likely be refined with generation of more datasets with dual protein and RNA expression to define these populations in distinct settings.

In summary, we have defined a multimodal approach to find potently activated CD8 T cells, hidden within the largely exhausted pool in tumors. The systematic use of Cd69 transcription, along with its surface protein expression may be imminently applicable in other important contexts including vaccination, resident memory formation and autoimmunity, to directly identify and study potent activation states of lymphocytes in situ.

Here we applied this strategy to isolate and validate that this subpopulation of effector CD8 T cells was functionally superior and otherwise not well illuminated by unbiased RNA-based cell clustering within the well-defined exhaustion paradigm. As future studies seek to better understand and manipulate the T*EFF cells, it is interesting to speculate that chemokines like XCL1/XCL2 would allow T*EFFs to attract the superior antigen presenting XCR1+ DCs to interact and drive a reactive archetype. These cells may indeed be generated by potent stimulation driven by cDC1s (33). While exploration of favorable cDC1 niches and networks continue to drive the field, the identification of functional T*EFFs now opens up the possibility to focus on directly detecting, studying and ultimately enhancing potent effectors in tumors, as an optimizing strategy to drive better patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Dr. Emily Flynn, UCSF for guidance with the CITE-Seq analysis. We thank Dr. Kelly Kersten, UCSF, Dr. Mike Kuhns, University of Arizona and Dr. Miguel Reina-Campos, University of California San Diego, for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Reina-Campos for sharing data from Zheng et.al in an analysis-ready format. We thank members of the Krummel lab for their inputs to the manuscript.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health Grants: NIH R01CA197363 and NIH R37AI052116

AR was supported by a Cancer Research Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship (CRI2940)

KHH was supported by an American Cancer Society and Jean Perkins Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship

GH was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (NSF2034836)

IZL was supported by Emerson Collective Health Research Scholars Program

Footnotes

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no competing interests

Data materials availability:

Relevant data will be made publicly available before publication in its final form. Meanwhile, data will be available upon reasonable request, please contact the authors directly.

References and Notes:

- 1.Broz M. L. et al. , Dissecting the Tumor Myeloid Compartment Reveals Rare Activating Antigen-Presenting Cells Critical for T Cell Immunity. Cancer Cell 26, 938 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masopust D., Ha S. J., Vezys V., Ahmed R., Stimulation history dictates memory CD8 T cell phenotype: implications for prime-boost vaccination. J Immunol 177, 831–839 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Au-Yeung B. B. et al. , A sharp T-cell antigen receptor signaling threshold for T-cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, E3679–3688 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandl J. N., Monteiro J. P., Vrisekoop N., Germain R. N., T cell-positive selection uses self-ligand binding strength to optimize repertoire recognition of foreign antigens. Immunity 38, 263–274 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schietinger A. et al. , Tumor-Specific T Cell Dysfunction Is a Dynamic Antigen-Driven Differentiation Program Initiated Early during Tumorigenesis. Immunity 45, 389–401 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.JJ M. et al. , Heterogenous Populations of Tissue-Resident CD8+ T Cells Are Generated in Response to Infection and Malignancy. Immunity 52, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltra J. C. et al. , Developmental Relationships of Four Exhausted CD8+ T Cell Subsets Reveals Underlying Transcriptional and Epigenetic Landscape Control Mechanisms. Immunity 52, 825–841.e828 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniel B. et al. , Divergent clonal differentiation trajectories of T cell exhaustion. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Wherry E. J. et al. , Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity 27, 670–684 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan O. et al. , TOX transcriptionally and epigenetically programs CD8 + T cell exhaustion. Nature 571, 211–218 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philip M. et al. , Chromatin states define tumour-specific T cell dysfunction and reprogramming. Nature 545, 452–456 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Z. et al. , TCF-1-Centered Transcriptional Network Drives an Effector versus Exhausted CD8 T Cell-Fate Decision. Immunity 51, 840–855.e845 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott A. C. et al. , TOX is a critical regulator of tumour-specific T cell differentiation. Nature 571, 270–274 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kersten K. et al. , Spatiotemporal co-dependency between macrophages and exhausted CD8+ T cells in cancer. Cancer Cell 40, 624–638.e629 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horton B. L. et al. , Lack of CD8 + T cell effector differentiation during priming mediates checkpoint blockade resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Immunol 6, eabi8800 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DA W. et al. , The Functional Requirement for CD69 in Establishment of Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells Varies with Tissue Location. Journal of immunology 203, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashouri J. F., Weiss A., Endogenous Nur77 Is a Specific Indicator of Antigen Receptor Signaling in Human T and B Cells. J Immunol 198, 657–668 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santis A. G., López-Cabrera M., Sánchez-Madrid F., Proudfoot N., Expression of the early lymphocyte activation antigen CD69, a C-type lectin, is regulated by mRNA degradation associated with AU-rich sequence motifs. Eur J Immunol 25, 2142–2146 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCaughtry T. M., Wilken M. S., Hogquist K. A., Thymic emigration revisited. J Exp Med 204, 2513–2520 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scharping N. E. et al. , Mitochondrial stress induced by continuous stimulation under hypoxia rapidly drives T cell exhaustion. Nature Immunology 22, 205–215 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelhardt J. J. et al. , Marginating dendritic cells of the tumor microenvironment cross-present tumor antigens and stably engage tumor-specific T cells. Cancer Cell 21, 402–417 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.You R. et al. , Active surveillance characterizes human intratumoral T cell exhaustion. J Clin Invest 131, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H. et al. , Dysfunctional CD8 T Cells Form a Proliferative, Dynamically Regulated Compartment within Human Melanoma. Cell 176, 775–789 e718 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boldajipour B., Nelson A., Krummel M. F., Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are dynamically desensitized to antigen but are maintained by homeostatic cytokine. JCI insight 1, e89289 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sagi Y., Landrigan A., Levy R., Levy S., Complementary costimulation of human T-cell subpopulations by cluster of differentiation 28 (CD28) and CD81. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 1613–1618 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Susa K. J., Seegar T. C., Blacklow S. C., Kruse A. C., A dynamic interaction between CD19 and the tetraspanin CD81 controls B cell co-receptor trafficking. Elife 9, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beltra J.-C. et al. , Enhanced STAT5a activation rewires exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic stimulation to acquire a hybrid durable effector like state. (2022).

- 28.Shay T. et al. , Conservation and divergence in the transcriptional programs of the human and mouse immune systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 2946–2951 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Combes A. J. et al. , Discovering dominant tumor immune archetypes in a pan-cancer census. Cell 185, 184–203.e119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng L. et al. , Pan-cancer single-cell landscape of tumor-infiltrating T cells. Science 374, abe6474 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Pilato M. et al. , CXCR6 positions cytotoxic T cells to receive critical survival signals in the tumor microenvironment. Cell 184, 4512–4530 e4522 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Micevic G. et al. , IL-7R licenses a population of epigenetically poised memory CD8(+) T cells with superior antitumor efficacy that are critical for melanoma memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 120, e2304319120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CS J. et al. , An intra-tumoral niche maintains and differentiates stem-like CD8 T cells. Nature 576, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barry K. C. et al. , A natural killer-dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy-responsive tumor microenvironments. Nat Med 24, 1178–1191 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruhland M. K. et al. , Visualizing Synaptic Transfer of Tumor Antigens among Dendritic Cells. Cancer Cell 37, 786–799.e785 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan Y. S., Lei Y. L., Isolation of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes by Ficoll-Paque Density Gradient Centrifugation. Methods Mol Biol 1960, 93–99 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGinnis C. S. et al. , MULTI-seq: sample multiplexing for single-cell RNA sequencing using lipid-tagged indices. Nat Methods 16, 619–626 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira G. et al. , Phenotype, specificity and avidity of antitumour CD8+ T cells in melanoma. Nature 596, 119–125 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carmona S. J., Siddiqui I., Bilous M., Held W., Gfeller D., Deciphering the transcriptomic landscape of tumor-infiltrating CD8 lymphocytes in B16 melanoma tumors with single-cell RNA-Seq. Oncoimmunology 9, 1737369 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim E. et al. , Inositol polyphosphate multikinase is a coactivator for serum response factor-dependent induction of immediate early genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 19938–19943 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Litvinchuk A. et al. , Complement C3aR Inactivation Attenuates Tau Pathology and Reverses an Immune Network Deregulated in Tauopathy Models and Alzheimer's Disease. Neuron 100, 1337–1353.e1335 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephens A. S., Stephens S. R., Morrison N. A., Internal control genes for quantitative RT-PCR expression analysis in mouse osteoblasts, osteoclasts and macrophages. BMC Res Notes 4, 410 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dobin A. et al. , STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li B., Dewey C. N., RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 323 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Othmer H. G., Dunbar S. R., Alt W., Models of dispersal in biological systems. J Math Biol 26, 263–298 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dickinson R. B., Tranquillo R. T., Optimal estimation of cell movement indices from the statistical analysis of cell tracking data. AIChE Journal Volume 39, Issue 12. AIChE Journal. 1993. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.