Abstract

Background

Trabeculectomy is performed as a treatment for many types of glaucoma in an attempt to lower the intraocular pressure. The surgery involves creating a channel through the sclera, through which intraocular fluid can leave the eye. If scar tissue blocks the exit of the surgically created channel, intraocular pressure rises and the operation fails. Antimetabolites such as 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) are used to inhibit wound healing to prevent the conjunctiva scarring down on to the sclera. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2000, and previously updated in 2009.

Objectives

To assess the effects of both intraoperative application and postoperative injections of 5‐FU in eyes of people undergoing surgery for glaucoma at one year.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Trials Register) (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 6), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to July 2013), EMBASE (January 1980 to July 2013), the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (www.controlled‐trials.com), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 25 July 2013. We also searched the reference lists of relevant articles and the Science Citation Index and contacted investigators and experts for details of additional relevant trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomised trials of intraoperative application and postoperative 5‐FU injections compared with placebo or no treatment in trabeculectomy for glaucoma.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration. We contacted trial investigators for missing information. Data were summarised using risk ratio (RR), Peto odds ratio and mean difference, as appropriate.

The participants were divided into three separate subgroup populations (high risk of failure, combined surgery and primary trabeculectomy) and the interventions were divided into three subgroups of 5‐FU injections (intraoperative, regular dose postoperative and low dose postoperative). The low dose was defined as a total dose less than 19 mg.

Main results

Twelve trials, which randomised 1319 participants, were included in the review. As far as can be determined from the trial reports, the methodological quality of the trials was not high, including a high risk of detection bias in many. Of note, only one study reported low‐dose postoperative 5‐FU and this paper was at high risk of reporting bias.

Not all studies reported population characteristics, of those that did mean age ranged from 61 to 75 years. 83% of participants were white and 40% were male. All studies were a minimum of one year long.

A significant reduction in surgical failure in the first year after trabeculectomy was detected in eyes at high risk of failure and those undergoing surgery for the first time receiving regular‐dose 5‐FU postoperative injections (RR 0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.29 to 0.68 and 0.21, 0.06 to 0.68, respectively). No surgical failures were detected in studies assessing combined surgery. No difference was detected in the low‐dose postoperative 5‐FU injection group in patients undergoing primary trabeculectomy (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.24). Peroperative 5‐FU in patients undergoing primary trabeculectomy significantly reduced risk of failure (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.88). This translates to a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome of 4.1 for the high risk of failure patients, and 5.0 for primary trabeculectomy patients receiving postoperative 5‐FU.

Intraocular pressure was also reduced in the primary trabeculectomy group receiving intraoperative 5‐FU (mean difference (MD) ‐1.04, 95% CI ‐1.65 to ‐0.43) and regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU (MD ‐4.67, 95% CI ‐6.60 to ‐2.73). No significant change occurred in the primary trabeculectomy group receiving low‐dose postoperative 5‐FU (MD ‐0.50, 95% CI ‐2.96 to 1.96). Intraocular pressure was particularly reduced in the high risk of failure population receiving regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU (MD ‐16.30, 95% CI ‐18.63 to ‐13.97). No difference was detected in the combined surgery population receiving regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU (MD ‐1.02, 95% CI ‐2.40 to 0.37).

Whilst no evidence was found of an increased risk of serious sight‐threatening complications, other complications are more common after 5‐FU injections. None of the trials reported on the participants' perspective of care.

The quality of evidence varied between subgroups and outcomes, most notably the evidence for combined surgery and low‐dose postoperative 5‐FU was found to be very low using GRADE. The combined surgery postoperative 5‐FU subgroup because no surgical failures have been reported and the sample size is small (n = 118), and the low‐dose postoperative 5‐FU group because of the small sample size (n = 76) and high risk of bias of the only contributing study.

Authors' conclusions

Postoperative injections of 5‐FU are now rarely used as part of routine packages of postoperative care but are increasingly used on an ad hoc basis. This presumably reflects an aspect of the treatment that is unacceptable to both patients and doctors. None of the trials reported on the participants' perspective of care, which constitutes a serious omission for an invasive treatment such as this.

The small but statistically significant reduction in surgical failures and intraocular pressure at one year in the primary trabeculectomy group and high‐risk group must be weighed against the increased risk of complications and patient preference.

Plain language summary

5‐Fluorouracil compared with placebo or no intervention during or after surgery for glaucoma

Background Glaucoma involves a loss of vision that may be associated with raised pressure inside the eye. When glaucoma is diagnosed, it is common to try to reduce that pressure with medical, laser or surgical procedures (trabeculectomy). Surgery does not immediately restore vision, and may involve extra vision loss in the short term. Drugs can be used to modify wound healing to improve the likelihood of the success of surgery.

Study characteristics This is a summary of a Cochrane review that looked at the effect of using one of these drugs, 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU). We gathered evidence from 12 trials involving 1319 participants. The evidence is current to July 2013.

5‐FU injections after glaucoma surgery For patients who have never had eye surgery before, 5‐FU injections after surgery can slightly reduce the pressure in the eye after one year and also the risk of having more surgery in the first year.

For patients having both cataract surgery and glaucoma surgery at the same time, no difference has been detected between injections and no injections.

Some people are at higher risk of having problems following trabeculectomy, for instance people that have had previous surgery on the eye. For this group, the 5‐FU injections can reduce the pressure in the eye a little and also reduce the risk of having more surgery in the first year.

Low‐dose 5‐FU injections after glaucoma surgery Only one study has investigated the effect of using lower than normal doses in the injections. No benefit was found when compared to a control group who had no injections.

5‐FU during surgery If 5‐Fluorouracil was applied to the eye during the surgery, there was less chance of having to have more surgery within the year and the pressure in the eye was also reduced slightly at one year.

Side effects and complications of 5‐FU during or after surgery Complications such as damage to cells at the front of the eye or a leak from the wound seem more common when 5‐FU is used.

Quality of evidence The methodological quality of the trials was not high in general. In many of the studies that contributed to the evidence about 5‐FU after glaucoma surgery the researchers were aware of whether the participant had received the dummy injection or the 5‐FU injection. This may have introduced bias into the results. Importantly the only study contributing information about low dose 5‐FU was of low methodological quality so our conclusions on low dose 5‐FU must be cautious.

The studies that contributed evidence about 5‐FU during surgery was largely very good, the studies were designed and reported to a standard we would expect of modern trials.

Conclusions We concluded that the main benefit is for people at high risk of problems. There may be a smaller benefit for people at low risk of problems if 5‐FU is given either as injections after surgery or during the operation. However, 5‐FU was found to increase the risk of serious complications and so may not be worthwhile for the small benefit gained.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus control for glaucoma surgery.

| Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control for glaucoma surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with glaucoma surgery Settings: ophthalmic surgery Intervention: regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | |||||

| Failure at 12 months | 286 per 1000 | 111 per 1000 (74 to 166) | RR 0.39 (0.26 to 0.58) | 469 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Mean intraocular pressure at 12 months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Due to heterogeneity among studies, results were not pooled. |

| Complications ‐ wound leak Follow‐up: 12 months | 143 per 1000 | 197 per 1000 (133 to 291) | RR 1.38 (0.93 to 2.04) | 469 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Complications ‐ hypotonous maculopathy | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Only reported in 1 study (Goldenfeld 1994). |

| Complications ‐ shallow anterior chamber Follow‐up: 12 months | 30 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (23 to 135) | RR 1.84 (0.76 to 4.46) | 469 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Complications ‐ epithelial toxicity Follow‐up: 12 months | 433 per 1000 | 675 per 1000 (589 to 771) | RR 1.56 (1.36 to 1.78) | 469 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). 5‐RU: fluorouracil; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The quality is reduced by the high or unclear risk of bias in a large number of the trials.

Summary of findings 2. Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus control for glaucoma surgery ‐ high risk of failure subgroup.

| Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control for glaucoma surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with glaucoma surgery Settings: ophthalmic surgery Intervention: regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | |||||

| Failure at 12 months ‐ high risk of failure | 433 per 1000 | 191 per 1000 (126 to 295) | RR 0.44 (0.29 to 0.68) | 239 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Mean intraocular pressure at 12 months ‐ high risk of failure | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months ‐ high risk of failure in the control groups was 30.7 mm Hg | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months ‐ high risk of failure in the intervention groups was 16.3 lower (18.63 to 13.97 lower) | ‐ | 26 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Complications ‐ wound leak ‐ high risk of failure Follow‐up: 12 months | 192 per 1000 | 314 per 1000 (199 to 494) | RR 1.64 (1.04 to 2.58) | 239 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Complications ‐ hypotonous maculopathy ‐ high risk of failure ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported in either 5‐FU or control group. |

| Complications ‐ shallow anterior chamber ‐ high risk of failure Follow‐up: 12 months | 42 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (37 to 274) | RR 2.41 (0.88 to 6.58) | 239 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Complications ‐ epithelial toxicity ‐ high risk of failure Follow‐up: 12 months | 750 per 1000 | 938 per 1000 (840 to 1000) | RR 1.25 (1.12 to 1.38) | 239 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). 5‐FU: 5‐Fluorouracil; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Due to some risk of bias in contributing studies, it was considered the quality of evidence for this outcome was moderate. The risk of bias was high in Ruderman 1987 due to the absence of masking and insufficient information to determine otherwise. Additionally, the FFSSG 1989 trial was terminated early. 2 The only contributing study, Ruderman 1987, has a high risk of performance and detection bias and an unclear risk of all other sources of bias. However, the effect size is large and highly clinically significant.

Summary of findings 3. Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus control for glaucoma surgery ‐ combined surgery subgroup.

| Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control for glaucoma surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with glaucoma surgery Settings: ophthalmic surgery Intervention: regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | |||||

| Failure at 12 months ‐ combined surgery | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 118 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | No surgical failures reported in either 5‐FU or control group. |

| Mean intraocular pressure at 12 months ‐ combined surgery | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months ‐ combined surgery in the control groups was 16.19 mm Hg | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months ‐ combined surgery in the intervention groups was 1.02 lower (2.4 lower to 0.37 higher) | ‐ | 118 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ‐ |

| Complications ‐ wound leak ‐ combined surgery Follow‐up: 12 months | 143 per 1000 | 129 per 1000 (51 to 319) | RR 0.9 (0.36 to 2.23) | 118 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ‐ |

| Complications ‐ hypotonous maculopathy ‐ combined surgery ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Outcome not reported. |

| Complications ‐ shallow anterior chamber ‐ combined surgery Follow‐up: 12 months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 118 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Shallow anterior chamber was not reported to occur in either 5‐FU or control group. |

| Complications ‐ epithelial toxicity ‐ combined surgery Follow‐up: 12 months | 125 per 1000 | 380 per 1000 (195 to 740) | RR 3.04 (1.56 to 5.92) | 118 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). 5‐FU: 5‐Fluorouracil; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The quality of this evidence is reduced by the risk of performance and detection bias in both O'Grady 1993 and Wong 1994. 2 As no events were recorded, no effect can be estimated.

Summary of findings 4. Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus control for glaucoma surgery ‐ primary trabeculectomy subgroup.

| Regular dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control for glaucoma surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with glaucoma surgery Settings: ophthalmic surgery Intervention: regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | |||||

| Failure at 12 months ‐ primary trabeculectomy | 255 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (15 to 173) | RR 0.21 (0.06 to 0.68) | 112 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ‐ |

| Mean intraocular pressure at 12 months ‐ primary trabeculectomy | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months ‐ primary trabeculectomy in the control groups was 17.25 mm Hg | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months ‐ primary trabeculectomy in the intervention groups was 4.67 lower (6.6 to 2.74 lower) | ‐ | 112 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ‐ |

| Complications ‐ wound leak ‐ primary trabeculectomy Follow‐up: 12 months | 36 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (1 to 179) | RR 0.47 (0.04 to 4.91) | 112 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ‐ |

| Complications ‐ hypotonous maculopathy ‐ primary trabeculectomy Follow‐up: 12 months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 62 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | Only one study recorded one event in the 5‐FU group |

| Complications ‐ shallow anterior chamber ‐ primary trabeculectomy Follow‐up: 12 months | 36 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (1 to 179) | RR 0.47 (0.04 to 4.91) | 112 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ‐ |

| Complications ‐ epithelial toxicity ‐ primary trabeculectomy Follow‐up: 12 months | 55 per 1000 | 319 per 1000 (111 to 918) | RR 5.85 (2.04 to 16.83) | 112 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). 5‐FU: 5‐Fluorouracil; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The quality of this evidence is reduced by high risk of bias in included studies. There is a risk of performance bias and detection bias in both Goldenfeld 1994 and Ophir 1992. Additionally, in Ophir 1992, the risk of selection bias was unclear and there was a known source of possible attrition bias. 2 The quality of evidence is reduced due to high risk of performance and detection bias in Goldenfeld 1994.

Summary of findings 5. Low‐dose postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus control for glaucoma surgery.

| Low‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control for glaucoma surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with glaucoma surgery Settings: Intervention: low‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Low‐dose postoperative 5‐FU versus control | |||||

| Failure at 12 months | 737 per 1000 | 685 per 1000 (516 to 914) | RR 0.93 (0.7 to 1.24) | 76 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Mean intraocular pressure at 12 months | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months in the control groups was 15.8 mm Hg | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months in the intervention groups was 0.5 lower (2.96 lower to 1.96 higher) | 76 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | ||

| Complications ‐ wound leak Follow‐up: 12 months | 26 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (0 to 209) | RR 0.33 (0.01 to 7.93) | 76 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Complications ‐ hypotonous maculopathy ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Outcome not reported |

| Complications ‐ shallow anterior chamber ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Outcome not reported |

| Complications ‐ epithelial toxicity ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Outcome not reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). 5‐FU: 5‐Fluorouracil; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Due to the high risk of bias in Chaudhry 2000 and broad confidence intervals that incorporate the possibility of benefit and detriment due to 5‐FU treatment the quality of evidence for this outcome was considered very low.

Summary of findings 6. Intraoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus placebo or control for glaucoma surgery.

| Intraoperative 5‐FU versus placebo or control for glaucoma surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with glaucoma surgery Settings: Intervention: intraoperative 5‐FU versus placebo or control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Peroperative 5‐FU versus placebo or control | |||||

| Failure at 12 months Need for repeat surgery or uncontrolled IOP (usually more than 22 mm Hg) despite additional topical or systemic medications | 267 per 1000 | 182 per 1000 (136 to 246) | RR 0.68 (0.51 to 0.92) | 711 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ‐ |

| Mean intraocular pressure at 12 months | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months in the control groups was 14.89 mm Hg | The mean intraocular pressure at 12 months in the intervention groups was 1.04 lower (1.65 to 0.43 lower) | ‐ | 711 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ‐ |

| Complications ‐ wound leak Follow‐up: 12 months | 156 per 1000 | 212 per 1000 (156 to 287) | RR 1.36 (1 to 1.84) | 711 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ‐ |

| Complications ‐ hypotonous maculopathy Follow‐up: 12 months | 11 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (5 to 58) | RR 1.47 (0.42 to 5.12) | 711 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | ‐ |

| Complications ‐ shallow anterior chamber Follow‐up: 12 months | 61 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 (75 to 197) | RR 1.99 (1.22 to 3.22) | 711 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ‐ |

| Complications ‐ epithelial toxicity Follow‐up: 12 months | 103 per 1000 | 127 per 1000 (88 to 182) | RR 1.23 (0.85 to 1.77) | 711 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). 5‐FU: 5‐Fluorouracil; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The broad confidence interval spans both a clinically advantageous and disadvantageous outcome. Consequently, the quality of evidence is reduced.

Background

Description of the condition

Lowering intraocular pressure (IOP) was established as a treatment for glaucoma more than 100 years ago. The lack of evidence that lowering IOP is effective in preventing continued loss of visual function in glaucoma documented by the first systematic review on eye health (Rossetti 1993), led to several definitive studies ‐ the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (Kass 2002), the European Glaucoma Prevention Study (Miglior 2005), and the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group (Heijl 2002). These, and subsequent systematic reviews (Maier 2005; Vass 2007), provide evidence that lowering IOP can prevent ocular hypertension and reduce the risk of progression of glaucoma. A review by Burr et al. comparing medical with surgical treatment was inconclusive but the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines published in 2009 recommend initial treatment with topical medications (Burr 2012; NICE 2009). However, if more than two medications are insufficient to control the pressure and prevent progression, then trabeculectomy augmented by antimetabolites is recommended though the augmentation itself is not specified (NICE 2009).

Trabeculectomy offers no immediate improvement in vision and indeed is often associated with the loss of some detailed vision in the short term. This usually recovers, although in some people there may be a small but permanent reduction in the visual potential of the operated eye. Glaucoma surgery of this type can be conducted under local or general anaesthesia as a day case procedure, but practice varies widely according to local resources and access to follow‐up care.

The operation involves separating the conjunctiva from the sclera by making an incision at the junction of the cornea and the sclera (on the part of the eye normally hidden under the upper eyelid), to form a conjunctival flap that is folded back to expose the underlying sclera. A half‐thickness incision is made into the sclera (usually 4 x 4 mm) at the corneo‐scleral junction. The half‐thickness scleral flap is raised towards the limbus and a small section of the sclera under the flap is removed (sclerostomy) allowing aqueous to leave the anterior chamber of the eye. The scleral flap is repositioned and loosely sutured. The flap guards the sclerostomy, preventing excessive egress of aqueous, which could result in hypotony (a very soft eye). Finally, the conjunctiva is replaced. Aqueous passes through the sclera and collects under the conjunctiva as a bleb. Fluid in the bleb is absorbed by capillaries and lymphatics within the conjunctiva, or evaporates across the conjunctiva. Final IOP is determined by many factors including the size of the bleb, the thickness of the conjunctiva and how adherent the conjunctiva around the bleb is to the sclera. If the conjunctiva overlying the operation site scars down onto the scleral flap then no aqueous can leave the eye, resulting in the return of raised IOP.

Optimum success rates for trabeculectomy are achieved when the eye has not been exposed to previous interventions, either surgical or medical (Lavin 1990). Risk factors for failure of trabeculectomy to control IOP include previous exposure to topical medication (especially sympathomimetic agents such as adrenaline), previous surgical manipulation of the conjunctiva or other injury. Age is inversely related to risk, and being of black African ethnic origin is thought by some surgeons to be a risk factor (Broadway 1994). Other risk factors for failure of first‐time trabeculectomy include diabetic status, a diagnosis of pigmentary glaucoma, grade of surgeon, position of traction suture, technique of local anaesthetic and IOP at listing (Edmunds 2004).

Description of the intervention

5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) is an antimetabolite that can be applied during or after surgery to prevent the conjunctiva scarring down onto the sclera. Peroperative (intraoperative) 5‐FU is usually administered to the sclera before or after the half‐thickness scleral flap incision is made often using sponges soaked in the 5‐FU solution applied for between two and five minutes. There is some variation in the technique used to deliver 5‐FU. Postoperative 5‐FU is administered as subconjunctival injections, the dose and regimen varies widely.

The patient's experience of glaucoma surgery is not thought to be influenced by the intraoperative use of antimetabolites, although this has not been formally assessed. The addition of a regimen of postoperative injections will significantly affect the patient's experience in terms of numbers of visits and sustained discomfort or pain from the injections.

How the intervention might work

The investigation of the use of agents to modify the wound‐healing process began in the early 1980s with work on 5‐FU and Mitomycin C beginning almost simultaneously in different parts of the world. 5‐FU is a pyrimidine analogue antimetabolite that blocks deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis through the inhibition of thymidylate synthesis. In vitro experiments on these agents are summarised by Blumenkranz 1984. The first successful animal model demonstrating the effectiveness of 5‐FU in bleb formation in the owl monkey was also reported in 1984 (Gressel 1984). The same group published the findings of a pilot study in humans of the use of 5‐FU in glaucoma filtering surgery (Heuer 1984). Shortly thereafter, the Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study Group (FFSSG) was established and the first large‐scale randomised controlled trial initiated (FFSSG 1992). Subsequent laboratory research indicated that a single intraoperative application of 5‐FU might be sufficient to control postoperative proliferation of scar tissue at the drainage site (Khaw 1992).

Why it is important to do this review

There have been no systematic reviews undertaken to summarise the totality of the evidence of the effectiveness of 5‐FU. Skuta and Parrish reviewed the role of agents in the modification of wound healing in 1987 in which numerous reports, almost all uncontrolled case series, of outcomes of different drainage techniques in different populations were summarised (Skuta 1987). Parrish's editorial in 1992 called for more randomised controlled trials on the use of antimetabolites in filtering surgery in order to answer important questions on who should and should not receive these agents (Parrish 1992). In reviewing combined glaucoma and cataract surgery in a perspectives article, Shields suggested that antimetabolites might be useful in improving the success of this procedure but again called for more evidence of effectiveness (Shields 1993). A more recent editorial raised valid concerns that the widespread use of antimetabolites in glaucoma surgery had the potential to do as much harm as good and urged caution (Higginbotham 1996). However, Chen's survey in the US and Japan revealed wide variation in practice reflecting the underlying uncertainty over the indications for their usage (Chen 1997).

Since this review was originally published, a number of randomised controlled trials have been conducted to examine the effectiveness of this method of application. Consequently the scope of this review was expanded to include intraoperative application of 5‐FU as a subgroup in the 2013 update. Clinicians now prefer the intraoperative application of agents for the modification of wound healing and routine postoperative injections of 5‐FU are now rarely used. They are, however, used by some people on an ad hoc basis if there are signs of imminent failure of the drainage procedure.

Postoperative injections of 5‐FU were the first of a planned series of reviews on the use of antimetabolites in glaucoma surgery. We have now divided the reviews according to the intervention tested as follows.

Postoperative 5‐FU injections versus control; intraoperative 5‐FU versus control; indirect comparison of postoperative and intraoperative 5‐FU in the absence of any head‐to‐head comparisons.

Intraoperative Mitomycin C versus control (Wilkins 2005).

Intraoperative Mitomycin C versus postoperative or intraoperative 5‐FU.

This review assessed the effects of postoperative 5‐FU injections compared with control and intraoperative 5‐FU versus control. Peroperative 5‐FU was planned as a separate review initially but, in 2012, we decided that it should be included in the postoperative review to create an overall review of 5‐FU use with trabeculectomy.

Objectives

To assess the effects of both postoperative 5‐FU injections and the intraoperative application of 5‐FU on the success rate of trabeculectomy and to examine the balance of risk and benefit at one year of follow‐up.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomised controlled trials. We excluded studies with follow‐up less than 12 months.

Types of participants

We included people with glaucoma and placed no further limitations on participant eligibility.

We considered three separate subgroup populations:

high risk of failure ‐ people who have had previous glaucoma drainage surgery or surgery involving anything more than trivial conjunctival incision including cataract surgery, glaucoma secondary to intraocular inflammation, congenital glaucoma and neovascular glaucoma;

combined surgery ‐ people undergoing trabeculectomy with extracapsular cataract extraction and intraocular lens implant;

primary trabeculectomy ‐ people who have received no previous surgical intervention as defined above. This group may include people who have had previous laser procedures.

Types of interventions

We included trials in which injections of 5‐FU were administered at any dose and compared with placebo injections or no injections. We divided the intervention into three subgroups.

Postoperative regular‐dose 5‐FU ‐ greater than 19 mg administered by injection in total in the five weeks following the operation.

Postoperative low‐dose 5‐FU ‐ less than 19 mg administered by injection in total in the five weeks following the operation.

Peroperative regular‐dose 5‐FU (hereafter referred to as intraoperative 5‐FU) ‐ greater than 19 mg administered by injection during the operation.

Postoperative low‐dose 5‐FU is considered separately because these are doses lower than are commonly used in clinical practice and the only study using these doses specified a 'low dose' postoperative series (Chaudhry 2000).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were the proportion of failed trabeculectomies at 12 months after surgery, and the mean IOP at 12 months. Failure was defined as the need for repeat surgery or uncontrolled IOP (usually more than 22 mm Hg) despite additional topical or systemic medications.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were adverse event rates in either group with reference to:

wound leaks ‐ the presence of a positive Seidel test (visible aqueous flow with the tear film stained with fluorescein);

hypotony ‐ the IOP is below 5 mm Hg or associated with complications such as macular oedema and sight loss or choroidal detachments;

late endophthalmitis ‐ an infection of the globe contents that even with prompt aggressive treatment often results in substantial loss of visual function. 'Late' here implies infection arising from organisms gaining access to the globe through thin‐walled drainage blebs or frank breaks in the conjunctival epithelium after the immediate postoperative period when infectious agents may have entered the eye during the surgical procedure;

expulsive haemorrhage ‐ choroidal haemorrhage, usually during the early postoperative period while the eye is still soft, leading to a marked rise in IOP;

shallow anterior chamber ‐ prolonged shallowing of the anterior chamber giving rise to concern over possible contact of the lens with the cornea and occurring as a result of excessive drainage or choroidal effusions or both leading to anterior displacement of the ciliary body, iris and lens;

corneal and conjunctival epithelial erosions ‐ punctate or confluent epithelial staining with fluorescein due to damage to the ocular epithelial surface;

other complications reported in individual trials.

Other definitions for general eye‐related terms can be found in the glossary contained within the Eyes and Vision Group module of The Cochrane Library.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2013, Issue 6, part of The Cochrane Library. www.thecochranelibrary.com (accessed 25 July 2013), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to July 2013), EMBASE (January 1980 to July 2013), the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (www.controlled‐trials.com), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 25 July 2013.

See: Appendices for details of search strategies for CENTRAL (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Appendix 3), mRCT (Appendix 4), ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 5) and the ICTRP (Appendix 6).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of identified trials to find additional trials. We used the Science Citation Index to find studies that had cited the identified trials. We contacted the investigators of the identified trials and practitioners who are active in the field to identify additional published and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts resulting from the searches. We obtained the full copies of any report referring to possibly or definitely relevant trials. We assessed all full copies according to the definitions in the 'Criteria for considering studies for this review'. We assessed only trials meeting these criteria for methodological quality.

Data extraction and management

We independently extracted data using a form developed by the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (available from the editorial base). We resolved any discrepancies by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In the 2013 update, we included 'Risk of bias' tables and figures and 'Summary of findings' tables. We assessed risk of bias for each trial according to Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Risk of bias did not determine inclusion in the synthesis.

We assessed sequence generation, allocation concealment, masking, loss to follow‐up and selective outcome reporting bias for each trial as being at high, unclear or low risk of bias. We contacted study authors for clarification when the risk of bias was unclear in the trial report.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was not limited provided that each eye was randomised separately. Injected 5‐FU and peroperative 5‐FU is not thought to act systemically. The unit of analysis for each study is documented in the Characteristics of included studies section.

Dealing with missing data

Where information regarding results or methodology was missing or unclear, we contacted the original authors. If they did not respond the authors evaluated what data could be included on a case by case basis. The inclusion and exclusion of studies is detailed in the Results of the search section.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic as described in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011), where a rough threshold of I2 > 50% represents substantial heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis was not conducted to explore heterogeneity as none were prespecified and would be of limited value.

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plots were not created to assess reporting bias because there were too few studies in each subgroup (fewer than 10) (Higgins 2011). We considered possible sources of reporting bias including funding, publication of articles and affiliation of study authors with manufacturers. Where sources of bias were identified, we reported this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Data synthesis

We summarised data for the probability of failure and common side effects using risk ratios (RR). We summarised data for mean IOP using the mean difference (MD). We used the Peto odds ratio to summarise data for rarer events such as complications. We provide 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all results.

We conducted separate analyses for regular‐dose and low‐dose 5‐FU trials as defined above and calculated summary estimates for each of the three subgroup populations.

We used the random‐effect model unless there were too few studies to estimate an effect in which case a fixed‐effect model was used.

In the absence of any head‐to‐head comparison of postoperative and intraoperative 5‐FU a post‐hoc indirect comparison between subgroups was conducted according to Borenstein 2008 using the I2 statistic to determine if any difference was due to subgroup differences or sampling error.

Sensitivity analysis

In 2013, we updated the sensitivity analyses following new recommendations in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011) and consequently deviated from the protocol. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to analyse the effect of including studies with any aspect of high or unknown risk of bias using the new 'Risk of bias' assessment method described above.

Summary of findings

The findings of the review were summarised using the recommendations in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011). Each 'Summary of findings' table is limited to one population group and reports the primary outcomes and key secondary outcomes. For each outcome, we reported the quality of the evidence, determined using GRADE. This classifies the evidence as 'high', 'moderate', 'low' or 'very low', an explanation of the broad significance of each grade is found at the bottom of each 'Summary of finding' table (Table 1). This grade of evidence is reduced if there are limitations to the design or implementation of studies, heterogeneity, imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals (CIs)) or a high probability of publication bias. If the evidence is graded less than 'high', an explanation is provided in the comments or footnotes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The original electronic searches revealed more than 70 studies. Two trials were excluded because reported follow‐up was less than 12 months (Hennis 1991; Lamba 1996). A further three trials were found not to meet the inclusion criteria when the full report was assessed, and were, therefore, excluded (Hefetz 1994; Lee 1996; Oh 1994). Seven randomised controlled trials met the review inclusion criteria. Scanning the reference lists of the reports revealed one further study (Loftfield 1991), which was published only as an abstract. As attempts to contact the authors were fruitless and no further information could be obtained about the study, Loftfield 1991 was excluded from the review's analysis. However, we have reported the complications described by Loftfield 1991 below because of the paucity of other research at low‐doses of 5‐FU and to highlight the risk of complications at lower doses. One further trial was identified in the update search in 2001 (Chaudhry 2000). Contact with the authors of identified trials and with researchers who are active in the field did not identify any further relevant studies.

Communication with practitioners in 2005 revealed an abstract in the proceedings of the American Academy of Ophthalmology (Baez 1993). The abstract reported a trial in which 72 patients undergoing combined cataract and trabeculectomy were randomised to receive postoperative 5‐FU or nothing. The abstract reported no difference in outcome with increased adverse events in the intervention arm. We have been unable to find a subsequent published report of this trial and our attempts to contact the authors have been unsuccessful and it has, therefore, been excluded. Buzarovska 2005 was also identified in 2005 but it did not randomise patients and so was excluded. Gandolfi 1997 was excluded because it matched participants undergoing combined cataract and trabeculectomy before randomisation.

An updated search was done in October 2008, which yielded a further 90 reports of studies. The Trials Search Co‐ordinator scanned the search results and removed any references that were not relevant to the scope of the review. The search did not identify any references that met the inclusion criteria for the review.

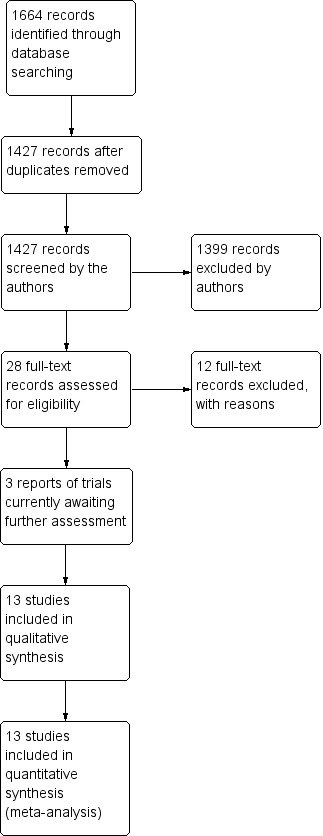

With the revision of the review in 2013, we included trials that used 5‐FU both intraoperatively and postoperatively. We redesigned and re‐ran the searches to reflect the change in the scope of the review and have included a PRISMA flow diagram showing the amended status of the review (Figure 1). There are currently 12 included studies in the review and 13 excluded studies. There are three studies awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for details). During this update, we also obtained a full copy of Donoso 1998, which had previously been unavailable. The report of the trial has been translated and included in the review.

1.

Update results combining searches for intraoperative and postoperative use of 5‐Fluorouracil.

Included studies

The following is a summary of the main features of the eight included studies for postoperative 5‐FU and the five trials for intraoperative 5‐FU. Further details can be found in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. Altogether, the 12 trials randomised 1023 eyes of 1319 participants. One peroperative study (Leyland 2001) included both eyes of four participants, each eye was randomised separately, two participants received 5‐FU and placebo, one received 5FU only, and one received placebo only.

POSTOPERATIVE 5‐FLUOROURACIL

Types of participants

The seven postoperative trials randomised 549 participants. Trials reported participants from three subgroups: those at high risk of failure (FFSSG 1989; Ruderman 1987), those undergoing combined cataract and trabeculectomy (O'Grady 1993; Wong 1994), and those undergoing trabeculectomy for the first time after failure to control IOP with medical intervention (Chaudhry 2000; Goldenfeld 1994; Ophir 1992). Six of the studies were conducted in the USA and one in Israel.

Types of intervention

5‐FU was administered in 5 mg injections in 0.1 or 0.5 mL saline solution. The schedule for injections varied across the trials with a mean total of five injections administered postoperatively. The schedule of injections for respective studies is presented in Table 7. Chaudhry 2000 reported the use of lower doses of 5‐FU with three 5 mg postoperative injections or fewer. Data for trials are presented separately according to whether regular dose or low dose 5‐FU was used. All studies compared 5=FU with no intervention. None used placebos.

1. Details of 5‐Fluorouracil intervention.

| Study ID | Total dose of 5‐FU administered | Dose per injection | Time period 5‐FU administered over | Dose classification |

| Chaudhry 2000 | 15 mg | 5 mg | 11 days | Low |

| Donoso 1998 | 50 mg/mL | Peroperative application | 5 minutes | Regular |

| FFSSG 1989 | 105 mg | 5 mg | 14 days | Regular |

| Goldenfeld 1994 | 25 mg | 5 mg | 14 days | Regular |

| Khaw 2002 | 50 mg/mL | Peroperative application | 5 minutes | Regular |

| Leyland 2001 | 25 mg/mL | Peroperative application | 5 minutes | Regular |

| O'Grady 1993 | 25 mg | 5 mg | 7 days | Regular |

| Ophir 1992 | 20‐30 mg | 5 mg | 10 days | Regular |

| Ruderman 1987 | 35 mg | 5 mg | 7 days | Regular |

| Wong 1994 | 25 mg | 5 mg | 16 days | Regular |

| Wong 2009 | 50 mg/mL | Peroperative application | 5 minutes | Regular |

| Yorston 2001 | 25 mg/mL | Peroperative application | 5 minutes | Regular |

5‐FU: 5‐Fluorouracil

Types of outcome measure

All of the trials reported success rates at between 12 and 25 months' follow‐up. The exact definitions of success varied across trials but control of IOP at or below 21 mm Hg with or without medications is an inclusive definition. All but one trial (FFSSG 1989), reported mean and standard deviation IOP pressure at 12 months. Complications reported in the trials included corneal epithelial toxicity, wound leaks, choroidal effusions, supra choroidal haemorrhage, hypotony and hyphaema. None of the trial reports has provided any outcomes from the participants' perspective.

INTRAOPERATIVE 5‐FLUOROURACIL

Types of participants

Five trials randomised 770 patients (Donoso 1998; Khaw 2002 (the Moorflo trial); Leyland 2001; Wong 2009; Yorston 2001). These trials were all related to each other through a collaborative network. They were all conducted on patients undergoing primary trabeculectomy for either chronic open‐angle glaucoma or chronic‐angle closure glaucoma. Two trials were conducted in the UK, one in Chile, one in Tanzania and one in Singapore.

Types of intervention

Yorston 2001 and Leyland 2001 published small studies on using 5‐FU intraoperatively during trabeculectomy at a dose of 25 mg per mL for five minutes after exposure of the sclera. Both of these were placebo controlled with the surgeons unaware whether the moistened sponge applied to the sclera contained 5‐FU or normal saline. Khaw 2002 published a report of the largest trial as an Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) abstract in 2002 but there is, as yet, no peer‐reviewed published report of this trial in the literature. Unpublished data from this trial have been obtained however. The Singapore 5‐FU trial first reported its results in an ARVO abstract in 2005 and the results were published in 2009 (Wong 2009). Both of these latter studies and Donoso 1998 used a higher dose of 50 mg 5‐FU for five minutes and were also double blinded placebo controlled.

Types of outcome measure

Various outcome measures were reported but through contact with the authors, it has been possible to retrieve outcomes included in this review.

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies for further details.

Risk of bias in included studies

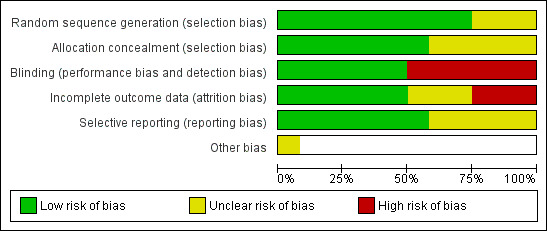

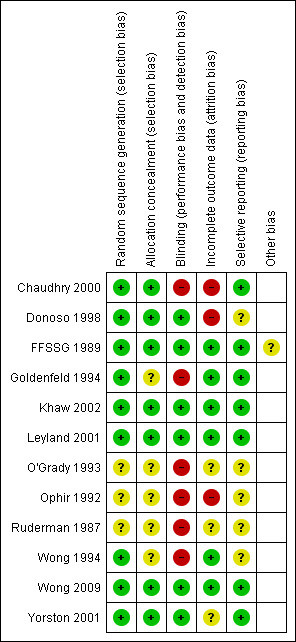

The risk of bias assessment is summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3 and the details of each decision are described in the Characteristics of included studies section.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We have attempted to contact trialists to obtain further information where there was insufficient information to determine the risk of bias. To date, we have received a response from Chaudhry 2000 and FFSSG 1989, and this information has been integrated into the risk of bias assessment. We have been unsuccessful in contacting Donoso 1998; O'Grady 1993; Ophir 1992; Ruderman 1987; and Wong 1994.

Allocation

The allocation concealment was thought to be adequate only in Chaudhry 2000; Donoso 1998; FFSSG 1989; Khaw 2002; Leyland 2001; Wong 2009; and Yorston 2001. Allocation concealment was unclear in the remaining five. In the absence of information about the randomisation process, O'Grady 1993; Ophir 1992; and Ruderman 1987 have been categorised as unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Masking was often inconsistent, in Chaudhry 2000, surgeons were masked to the treatment allocation during the operation to reduce performance bias; however, there was no masking of assessors when the outcomes were recorded introducing possible detection bias. There was no record of masking in Goldenfeld 1994; O'Grady 1993; Ophir 1992; Ruderman 1987; or Wong 1994. This omission is interpreted by the authors to indicate that it probably did not occur and consequently it is thought that both performance and detection bias could have occurred.

It was thought that there was a low risk of performance or detection bias in studies that took precautions by masking the surgeons and outcome assessors. Some particularly well‐designed studies also masked patients (Khaw 2002; Leyland 2001). Others only masked assessors and did not mask patients (Donoso 1998; FFSSG 1989; Yorston 2001), these studies were still classed as 'low‐risk' because the objective outcomes make it difficult for a patient to introduce bias.

No study described whether researchers were masked during analysis.

Incomplete outcome data

It is known that patients with unfavourable results were excluded from Chaudhry 2000 and Ophir 1992. The risk of attrition bias could not be determined in O'Grady 1993 or Ruderman 1987. A substantial number were lost to follow‐up in Donoso 1998 and Yorston 2001, and, although this seemed to be distributed equally between the control and intervention group, there is a possible risk of attrition bias. The reason for these losses is unclear, although, in both cases, it is thought to reflect the research environment in these countries (Chile and Tanzania).

Selective reporting

Insufficient information was provided to judge whether prespecified outcomes had been reported in Donoso 1998; O'Grady 1993; Ophir 1992; Ruderman 1987; and Wong 1994, therefore we judged these to be at an unclear risk of bias. However, the reported outcomes appeared appropriate and in keeping with the intervention and aims of the studies. The risk was low in all other studies.

Other potential sources of bias

The FFSSG study was terminated early by an independent ethics committee. This may have introduced bias in either direction but most likely an overestimate of effect (according to Briel 2012).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus control

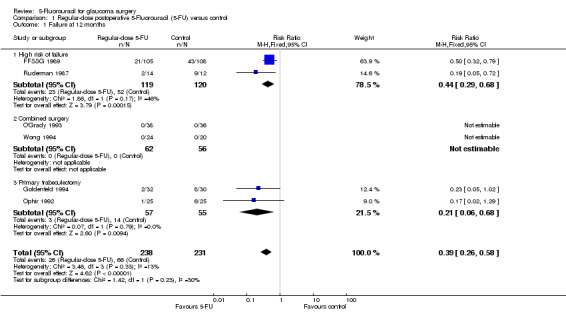

Failure at 12 months (Analysis 1.1)

High risk of failure

Two trials randomised 239 participants (FFSSG 1989; Ruderman 1987). The results show an apparent benefit of 5‐FU injections (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.68) or a point estimate of a 56% reduction in the risk of failure. A larger effect was observed in the Ruderman study despite a smaller overall dose being given. The CIs for this study are much wider as a result of the small sample size (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) versus control, Outcome 1 Failure at 12 months.

Combined surgery

Two trials randomised 118 participants (O'Grady 1993; Wong 1994). No failure at 12 months was reported in either the control or treatment arm by O'Grady 1993 or Wong 1994.

Primary trabeculectomy

Two trials randomised 112 participants (Goldenfeld 1994; Ophir 1992). The point estimate of RR for failure in the 5‐FU group was 0.21 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.68), a 79% reduction in risk of failure and statistically significant. The individual studies found no statistically significant effect, but when the results are pooled, a significant effect was observed (Analysis 1.1).

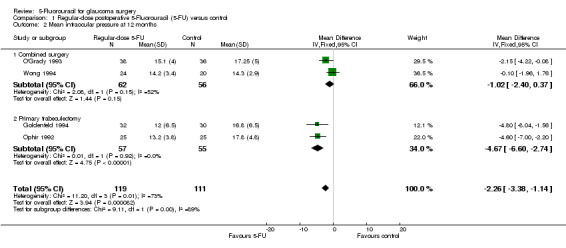

Mean intraocular pressure at 12 months (Analysis 1.2)

High risk of failure

Only one study reported the mean and standard deviation of IOP and so meta‐analysis could not be performed. Ruderman 1987 found a 16.30 mm Hg difference between treatment and control arms (95% CI 13.97 to 18.63).

Combined surgery

The pooled estimate of effect for the two trials was a reduction of 1.02 mm Hg in the 5‐FU group (95% CI 0.37 to 2.40), but the CI crosses the line of no effect.

Primary trabeculectomy

Mean IOP reduction in the two trials is similar. The pooled estimate of effect is a reduction of 4.67 mm Hg in the 5‐FU group (95% CI 2.74 to 6.60) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) versus control, Outcome 2 Mean intraocular pressure at 12 months.

Wound leak

The risk of wound leak was increased for the high risk of failure 5‐FU group (RR (random‐effects) 1.64, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.58). The CI crosses the line of no effect for the combined surgery and primary trabeculectomy groups (Table 8).

2. Risk of complications.

| Intervention | Complication (risk ratio (95% confidence interval)) | ||||

| Wound leak | Hypotonous maculopathy | Expulsive haemorrhage | Shallow anterior chamber | Epithelial toxicity | |

| Postoperative 5‐FU, regular dose vs control | |||||

| High risk of failure intraoperative 5‐FU | 1.64 (1.04, 2.58) | 0.85 (0.28, 2.55) | 2.41 (0.88, 6.58) | 1.25 (1.12, 1.38) | |

| Combined surgery | 0.90 (0.36, 2.23) | 3.04 (1.56, 5.92) | |||

| Primary trabeculectomy | 0.47 (0.04, 4.91) | 0.47 (0.04, 4.91) | 5.85 (2.04, 16.83) | ||

| Peroperative 5‐FU, regular dose vs control | |||||

| Primary trabeculectomy | 1.36 (1.00, 184) | 1.47 (0.42, 5.12) | 1.99 (1.22, 3.22) | 1.23 (0.85, 1.77) | |

Hypotonous maculopathy

Hypotonous maculopathy was reported as a complication in one participant in one trial in the higher dose primary trabeculectomy group (Goldenfeld 1994). The estimated risk is raised for the 5‐FU treated participants at approximately a three‐fold increase (RR 2.82, 95% CI 0.12 to 66.62). However, these events are rare and the CIs around this estimate are wide (Table 8).

Late endophthalmitis

Late endophthalmitis was not reported in any of the trials within 12 months' follow‐up; therefore, the risk cannot be estimated.

Expulsive haemorrhage

Expulsive haemorrhage was reported only in trials on participants in the high risk of failure group. Similar numbers were seen in both treatment groups in both studies. This is probably an underlying risk of the surgical procedure on eyes that were already damaged from previous surgery or inflammation or may reflect the higher baseline IOP in this group (Table 8).

Shallow anterior chamber

Shallow anterior chamber was inconsistently reported in the trials as a complication. The definition varied from study to study. No consistently increased risk was observed for people receiving 5‐FU (Table 8).

Epithelial toxicity

Epithelial toxicity was observed in all studies and the risk was always greater in the 5‐FU group and the RR was statistically significant in several studies. The size of the effect varied considerably, which may reflect differences in the site and method of injection and the overall dose given. None of the trials reported a lasting ocular surface disturbance so that the use of the antimetabolite does not appear to be a serious complication. However, the discomfort caused by this adverse effect is likely to have had a major impact on the participants' experience of treatment. As already stated, participants' experience of treatments were not reported in any of the studies (Table 8).

Numbers needed to treat to obtain an additional beneficial outcome

There was a statistically significant reduction in the risk of failure for the high‐risk group of 24% (95% CI 13% to 35%) and 20% (95% CI 7% to 33%) for the primary trabeculectomy group. This translates to a NNTB of 4.1 for the high risk of failure patients, and 5.0 for primary trabeculectomy patients. There were no events in the combined surgery group.

Lower‐dose postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus control

Chaudhry 2000 only included participants undergoing primary trabeculectomy.

Main outcome measures

Chaudhry 2000 found no evidence of a difference in failure rates or a difference in the mean number of postoperative pressure controlling medications used in either group (Table 9). Mean reduction in IOP was very similar in both groups (11.5 ± 9.1 mm Hg 5‐FU, 10.2 ± 8.7 mm Hg control) and this was not statistically significant.

3. Results of Chaudhry 2000.

| Outcome | Low dose 5‐FU (n=38) | Control (n=38) | Risk ratio (95% CI) |

| Events | Events | ||

| Failure at 12 months | 26 | 28 | 0.93 (0.70, 1.24) |

| Wound leak | 0 | 1 | 0.33 (0.01, 7.93) |

| Cataract | 6 | 1 | 6.00 (0.76, 47.49) |

| Choroidal drainage | 3 | 2 | 1.50 (0.27, 8.48) |

| Bleb encapsulation | 7 | 6 | 1.17 (0.43, 3.15) |

Wound leak

One instance of wound leak occurred in the control group, this difference was not statistically significant, (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.93).

Additional complications

The other secondary outcomes of hypotonous maculopathy, late endophthalmitis, expulsive haemorrhage and epithelial toxicity were not reported. Chaudhry 2000 did, however, report cataract, choroidal drainage (presumably for persistent choroidal detachment) and bleb encapsulation (Table 9). None reached statistical significance although the point estimate for cataract was large (RR 6.00, 95% CI 0.76 to 47.49; risk difference 13%, 95% CI 0% to 26%; number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) 8).

Although only published as an abstract and not included in this review's analysis it is noteworthy that Loftfield 1991 reported a substantial but not statistically significant increase in risk of hypotonous maculopathy in the 5‐FU group (RR 7.88, 95% CI 0.45 to 137.8; risk difference 17%, 95% CI 0.0% to 34%; NNTH 6). Loftfield 1991 also reported a substantial increased RR of epithelial toxicity of 18.38 (95% CI 1.14 to 295.00; risk difference 43%, 95% CI 23% to 64%; NNTH 2).

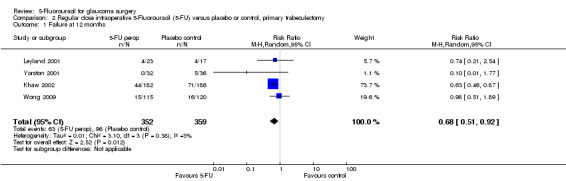

Intraoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus control

Main outcome measures (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2)

The point estimate risk reduction of failure at one year was quite substantial at 0.67 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.88) (Analysis 2.1), and this effect is mainly due to the Khaw 2002 results. The difference in effect estimates of the different trials did not reflect the lower dose of 5‐FU used in Leyland 2001 and Yorston 2001.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Regular dose intraoperative 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) versus placebo or control, primary trabeculectomy, Outcome 1 Failure at 12 months.

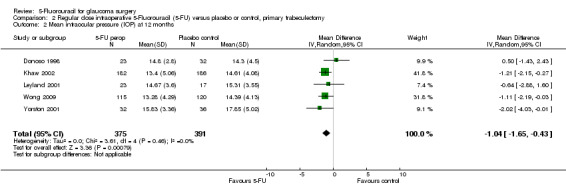

For the mean differences in IOP at one year, there was a small overall reduction in IOP of 1.04 mm Hg (95% CI 0.43 to 1.65), which is probably not clinically significant but is nevertheless statistically different. There was no heterogeneity (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Regular dose intraoperative 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) versus placebo or control, primary trabeculectomy, Outcome 2 Mean intraocular pressure (IOP) at 12 months.

Wound leak

5‐FU caused a 50% increase in the RR of wound leak, which is just significant with the summary estimate with no statistical heterogeneity or apparent dose‐related response (Table 8).

Hypotonous maculopathy

Only Khaw 2002 reported hypotonous maculopathy, which was slightly more common in the 5‐FU arm.

Late endophthalmitis and expulsive haemorrhage

The secondary outcomes of late endophthalmitis and expulsive haemorrhage were not reported by any study of intraoperative 5‐FU and, therefore, risk cannot be estimated.

Shallow anterior chamber

5‐FU significantly increased the risk of anterior chamber shallowing (Table 8). However there was heterogeneity observed with the Singapore trial observing an opposite risk (Wong 2009).

Epithelial toxicity

Only reported in the Leyland 2001 and Wong 2009 trials and in only the latter was it commonly reported being slightly more frequent in the 5‐FU arm (Table 8).

Number needed to treat for an additional beneficial effect

There was a statistically significant reduction in the risk of failure in the intraoperative 5‐FU subgroup of 9% (95% CI 15% to 3%), which translates into an NNTB of 11.

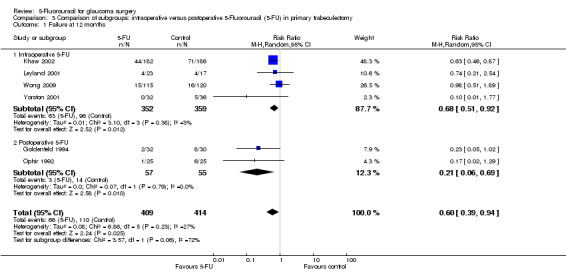

Intraoperative 5‐Fluorouracil versus postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil

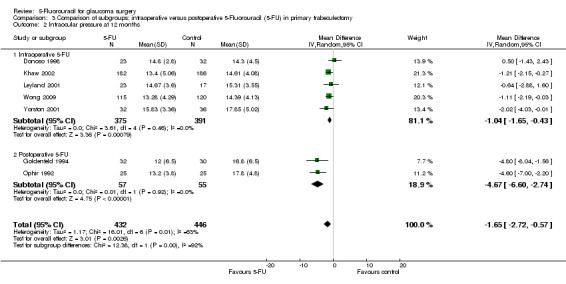

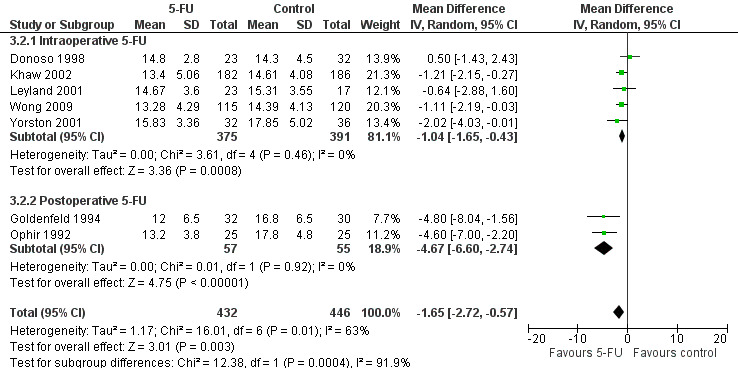

In the absence of any head‐to‐head trials a post‐hoc indirect comparison was conducted (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Figure 4). Postoperative 5‐FU reduces IOP more than intraoperative 5‐FU when used in an equivalent population, in this case primary trabeculectomy, mean difference ‐4.67 (95% CI ‐6.60 to ‐2.74) and ‐1.04 (95% CI ‐1.65 to ‐0.43) respectively (I2 = 63%). The confidence intervals do not overlap and so it is statistically significant. The large I2 statistic confirms that this is likely to be due genuine subgroup differences rather than sampling error (Borenstein 2008). Postoperative and intraoperative 5‐FU have a similar reduction on risk of failure however, risk ratio 0.21 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.68) and 0.67 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.88) respectively (I2 = 27%). This should be interpreted cautiously as it was a post‐hoc calculation.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparison of subgroups: intraoperative versus postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) in primary trabeculectomy, Outcome 1 Failure at 12 months.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparison of subgroups: intraoperative versus postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) in primary trabeculectomy, Outcome 2 Intraocular pressure at 12 months.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Comparison of subgroups: intraoperative versus postoperative 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐FU) in primary trabeculectomy, outcome: 6.2 Intraocular pressure at 12 months.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the effect of excluding studies where the risk of bias was unclear or high. It was found that results remain similar when high or unclear risk of bias studies were excluded, neither the degree of risk nor the significance was altered. However, in the majority of subgroups there were no studies with a low risk of bias and therefore the high or unclear risk of bias studies determine our findings. This is the case for the regular‐dose combined surgery subgroup, regular‐dose primary trabeculectomy subgroup and low‐dose primary trabeculectomy subgroup.

Missing outcome data

Losses to follow‐up were minimal in most trials with the exception of Yorston 2001, where 8 of 36 placebo and 10 of 32 intervention participants were lost at follow‐up and also Donoso 1998, where 13 patients were lost at follow‐up. Missing outcome data were unlikely, therefore, to have implications for outcomes relating to postoperative 5‐FU. However, losses may have slightly altered the estimation of surgical failure rates and IOP in the intraoperative group and could have had a substantial impact on the estimation of complication rates.

Ophir 1992 excluded the results of four participants from analysis because they were classified as surgical failures. The report does not make it clear whether these participants were in the intervention or control group. If all four failures had occurred in the intervention group this would increase the CIs to include 1. It may have also affected the estimations of risk of complications. Our conclusions regarding the primary trabeculectomy group receiving regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU are therefore diminished.

The data for IOP, the only continuous outcome, did not appear skewed upon visual inspection.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The mean risk of failure was reduced by application of 5‐FU in all methods of administration and all subgroups except the combined surgery subgroup. However, reduction in risk is small and of questionable clinical significance in the regular‐dose postoperative injection primary trabeculectomy group and the intraoperative group. Furthermore, in the low‐dose group the CIs were so wide as to make this reduction non‐significant.

People with pre‐existing risk factors for surgical complications had the greatest reduction in IOP following surgery, although only one study contributed to these data. Regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU reduced IOP more than control in high‐risk patients, the mean difference was ‐16.30 (CI ‐18.63 to ‐13.97) while in the primary trabeculectomy group the difference was smaller ‐4.67 (CI ‐6.60 to ‐2.74).

There is no apparent effect of 5‐FU at regular dosages in people undergoing combined cataract extraction and trabeculectomy. The most likely reason for this is that the underlying risk of failure is lower in this group. Much larger samples would be required to show an effect if present and is, therefore, not excluded by these results. Because the levels of IOP were generally lower preoperatively, it is possible that the effect of 5‐FU has been missed because of an excessively high IOP cut‐off for failure definition. This is illustrated in Gandolfi 1997, where according to the global criteria of success (IOP less than 22 mm Hg), there was no difference between groups, but when a lower cut‐off in IOP is applied (15 mm Hg) a difference between the groups appears. However, O'Grady 1993 stratified participants into those whose pressures were over 21 mm Hg preoperatively and those whose pressures were less than 22 mm Hg (n = 30 and 44, respectively). Although the mean IOP was slightly higher in the previously hypertensive group, there was still no difference between intervention and control groups in either stratum.

It is perhaps not surprising that the effectiveness of 5‐FU injections is at the expense of an increased risk of complications, particularly for corneal epithelial damage, wound leak and shallow anterior chamber. However, permanent sight‐threatening complications, such as expulsive haemorrhage (which occurred more often in the 'high risk of failure' eyes recruited to FFSSG 1989 than in the other studies) or endophthalmitis (reported in a patient in the control arm at two years follow up in Donoso 1998) do not appear to occur more frequently in 5‐FU‐treated eyes. Hypotonous maculopathy is a serious but not necessarily sight‐threatening complication once it has resolved. Only two trials reported this complication ‐ Goldenfeld 1994, in the regular dose primary trabeculectomy group with one event in the 5‐FU group; and Loftfield 1991, in the lower‐dose primary group. However, the Loftfield 1991 criteria and definitions are not described in the abstract report. Chaudhry 2000 described new complications including cataract that occur with greater frequency following 5‐FU injections. Subsequent surgery to deal with the cataract may jeopardise the success of the filtering procedure.

There were variations in dose, frequency and site of 5‐FU injections between the trials included in this review that may have an impact on the comparisons. By separating the studies into regular‐ and low‐dose interventions, a possible dose‐response effect is detectable, although the CIs were mutually inclusive. This dose response was not assessed statistically as only one study contributed to the low‐dose data. From the data available, a mean of three injections or fewer did not appear to impact on failure rates while a mean of five injections was successful in participants with an elevated risk of failure and those undergoing primary surgery. However, at higher doses there was no consistent pattern. The FFSSG 1989 study used the highest total dose of 5‐FU (105 mg) but did not see lower failure rates than other studies using doses between 25 mg and 30 mg (Analysis 1.1).The intraoperative dose did not seem to affect the outcomes, although this was not formally analysed.

Peroperative application of 5‐FU to the sclerectomy site showed a lower effects on the relative risk of failure after primary trabeculectomy when compared with regular‐dose postoperative 5‐FU injections in the same population. The difference between regular dose intraoperative and postoperative 5‐FU was not statistically significant however (Analysis 3.1). Similarly, the mean reduction in IOP was less at 1.0 mm Hg compared with 4.6 mm Hg in primary trabeculectomy having the full postoperative dose, which was statistically significant (Analysis 3.2).

People undergoing an initial drainage procedure have a much lower risk of failure when compared with the high‐risk group and complications, though rare, can be unpleasant and serious. Use of 5‐FU injections, therefore, needs to be carefully considered in the primary trabeculectomy group and an individual's risk of failure needs careful assessment before a decision is made to use them. The patient and surgeon alike need to have made a balanced assessment of risk and benefit.

It is the largest Moorflo trial (Khaw 2002) that demonstrates a large and statistically risk reduction in terms of failure, however the lack of significance of all the other intraoperative trials reduces to overall estimate of effect to be almost compatible with none when pooled (lower confidence interval of ‐0.03). This trial remains unpublished though it is likely to be published soon. A possible explanation for differences in these studies that is hard to quantify is the effect of postoperative needling, which was allowed though to differing protocols in the Moorflo and Singapore studies. However, masking will have prevented any bias in the likelihood of receiving needling in the treatment and placebo arms.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

A notable omission from all the trials was any attempt to report the participants' perception of their treatment. Such an invasive and potentially unpleasant treatment would need a powerful additional therapeutic benefit to balance the repeated trauma of postoperative subconjunctival injections and the inconvenience and expense of frequent returns to the hospital or a prolonged inpatient stay. The additional discomfort caused by ocular surface damage is another important consideration.

A problem with randomised controlled trials is that they are rarely large enough to examine the occurrence of rare but important adverse events. Case reports exist highlighting complications following trabeculectomy using postoperative 5‐FU injections. They include hypotony (Kee 1994; Stamper 1992), and ocular surface problems (Knapp 1987; Lee 1987; Peterson 1990; Stank 1990). One retrospective review highlighted a late onset bleb‐related endophthalmitis rate of 3% over two years in trabeculectomies performed superiorly (Wolner 1991). A discussion of expulsive haemorrhage in the FFSSG participants found a strong association between haemorrhage and the difference between preoperative and postoperative IOP (FFSSG 1992). No association was shown with the use of 5‐FU.

This systematic review fails to inform adequately about the occurrence of important but rare complications of this adjuvant to surgery, which may be for a number of reasons including:

variable definitions of complications ‐ definitions can be very subjective and are often not described even where criteria could be helpful, for example, maximum IOP criterion when defining hypotony. Only one paper gives a definition of hypotony (Wong 1994);

variable operative technique ‐ a surgeon who prefers to tightly close his/her scleral flap is less likely to have a shallow postoperative anterior chamber, even if this is thought to increase the chances of having too high a postoperative IOP;

low event rate for some of the complications ‐ the most extreme example of this was for endophthalmitis where no cases were detected in any study in the follow‐up period of this analysis.

Quality of the evidence